Abstract

Objective:

This meta-analysis aimed to investigate the risks and physiological development differences during puberty in overweight and obese boys.

Methods:

Following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines and AMSTAR criteria, we systematically searched PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science, with a cutoff date of July 2025. After applying strict inclusion and exclusion criteria and performing quality assessments, statistical analysis was conducted using STATA 17.0 and Review Manager (version 5.4).

Results:

A total of 12 prospective cohort studies meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the analysis. The meta-analysis indicated that overweight boys had a significantly higher risk of early testicular enlargement compared to normal-weight boys (overweight RR 1.38, obese RR 1.43). Regional differences were observed, with significant variations in the association between overweight status and early testicular enlargement risk in the U.S. and Asia-Pacific regions. Overweight and obese boys older than 6 years had a stronger association with early testicular enlargement. Furthermore, overweight boys experienced an earlier onset of early testicular enlargement compared to normal-weight boys (MD -0.23, p=0.002), while no significant difference was observed in obese boys (MD -0.23, p=0.10). In terms of pubic hair development, overweight (RR 1.24, p<0.00001) and obese boys (RR 1.42, p<0.00001) were at a higher risk for early development, and overweight boys developed pubic hair earlier (MD -0.38, p=0.0008). No significant difference was found in peak height velocity between obese and normal-weight boys (MD -0.32, p=0.09).

Conclusion:

Overweight and obesity have notable effects on male puberty development, particularly with respect to early testicular enlargement and pubic hair development.

Systematic Review Registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier, CRD420251172699.

1 Introduction

Puberty is a crucial transitional period in children’s growth, marking the shift from childhood to adulthood, characterized by rapid physical growth and significant development of secondary sexual characteristics (1, 2). In boys, key milestones of puberty include testicular development, the appearance of pubic hair, peak height velocity, voice changes, and the first ejaculation, all commonly used to assess the progress of puberty. The development of puberty is precisely regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, which involves various sex hormones and metabolic factors (1, 3). Puberty in boys typically begins around age 9 and continues until around age 14. Early or delayed puberty development is closely associated with poor health and psychological distress (4). While the timing of puberty is influenced to some extent by genetic factors, nutrition and environmental factors also play significant roles (5).

Childhood overweight and obesity are global public health concerns, prevalent in both developing and developed countries. In China, it has been reported that up to 19.2% of children aged 7–18 are overweight or obese (6). The obesity rate among children aged 6 to 11 rose from 7% in 1980 to nearly 18% in 2012, while the proportion of obese individuals aged 12–19 increased from 5% to nearly 21% (7). Studies have consistently shown a clear association between childhood overweight and obesity and the early onset of puberty in girls. A growing number of longitudinal studies confirm that overweight or obese girls enter puberty earlier than their normal-weight counterparts, a trend observed globally. Obesity may influence puberty development through mechanisms such as activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, alterations in sex hormone levels, and metabolic disruptions (8). However, the relationship between childhood obesity and puberty development in boys remains inconsistent. Some studies suggest that obese boys experience earlier puberty onset than normal-weight boys, while others indicate a delay in puberty development in obese boys, even compared to normal-weight boys. Some research suggests that obesity may disrupt puberty development in boys by altering metabolic and endocrine factors, leading to changes in sex hormone secretion and delayed physiological development (9).

Existing studies on childhood obesity and puberty development in boys are primarily cross-sectional, which allows for the identification of correlations between obesity and puberty development but does not clarify causal relationships or explain underlying mechanisms and long-term effects. Additionally, the milestones used to assess puberty development vary across studies. For instance, some studies focus solely on testicular development and height growth, while neglecting other key factors that may influence puberty, such as voice changes and the occurrence of nocturnal emissions. This contributes to inconsistencies in results across different studies (10). Puberty is a multi-stage process that involves not only physical changes but also psychological, social, and physiological factors. Although some reviews and meta-analyses have discussed the impact of childhood obesity on puberty development, most of them focus exclusively on girls’ puberty development, either overlooking studies on boys or limiting the discussion to a single marker of precocity (11–13). Therefore, it is crucial to explore the comprehensive impact of childhood obesity on puberty development in boys. To gain a deeper understanding of how obesity affects puberty in boys, this study aims to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis specifically examining the relationship between childhood obesity and puberty development in boys. Our findings may provide valuable insights into the risks of precocious puberty in overweight or obese boys.

2 Materials and methods

This evidence-based analysis follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines and adheres to the Systematic Review Methodology Quality Assessment (AMSTAR) standards to ensure methodological rigor and high-quality analysis (14, 15). Overweight and obesity are defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria: overweight is a body mass index (BMI) between the 85th and 95th percentiles for children of the same age and sex, while obesity is defined as a BMI exceeding the 95th percentile. Tanner staging is an internationally recognized system for assessing the progress of puberty. Tanner Stage 2 marks the onset of puberty, characterized by an increase in testicular volume to 4 milliliters or greater and the appearance and spread of pubic hair. During puberty, boys also experience rapid height growth, the first ejaculation, and voice changes. These indicators are the focus of this review. Our systematic review has been prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD420251172699).

2.1 Literature search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive literature search in PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science, focusing on studies published from the earliest available records up to July 2025. These studies compared the growth and development of obese boys with that of non-obese boys. The following English keywords were used for the search: “boys,” “men,” combined with terms related to obesity, such as “overweight,” “obesity,” “obese,” “abdominal obesity,” and “central obesity,” as well as puberty-related terms, such as “puberty,” “precocious,” “gonadal development,” “pubic hair development,” and “peak height velocity.” For example, the specific search strategy in PubMed was: ((“Male” [Mesh] OR “boy” [Title/Abstract] OR “man” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“Overweight” [Mesh] OR “Obesity” [Mesh] OR “overweight” [Title/Abstract] OR “obese” [Title/Abstract] OR “obesity” [Title/Abstract] OR “abdominal obesity” [Title/Abstract] OR “central obesity” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“puberty” [Title/Abstract] OR “precocious” [Title/Abstract] OR “gonadarche” [Title/Abstract] OR “pubarche” [Title/Abstract] OR “Adolescent Peak Height Velocity” [Title/Abstract])). Additionally, we reviewed articles on childhood obesity and puberty development, including their reference lists, to ensure no relevant studies were overlooked.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria for literature

This study aims to compare puberty development in obese boys versus non-obese boys. Eligible studies will be included if they meet the following inclusion criteria:

Inclusion Criteria:

-

(1)Population: Studies involving children categorized as overweight/obese based on body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, or BMI trajectory (using data from at least two time points).

-

(2)Intervention: Studies that assess the impact of childhood overweight/obesity on puberty development, specifically the association with at least one puberty milestone in boys, including the onset of testicular development, appearance of pubic hair, and peak height velocity.

-

(3)Comparison: Studies comparing obese boys with non-obese boys.

-

(4)Outcome: The study must report at least one puberty development indicator for boys.

-

(5)Study Design: Cohort studies, case-control studies, or randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Exclusion criteria:

-

(1)Studies where weight categories (normal weight, overweight, obese) are not clearly defined.

-

(2)Studies that do not include any puberty development indicators for boys.

-

(3)Studies that do not specifically report results for boys.

-

(4)Studies focusing on individuals with conditions that may affect sexual development, such as congenital gonadal developmental disorders, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, etc.

2.3 Assessment of the quality and evidence level of included studies

All studies included in this analysis are cohort studies. For the literature quality assessment, we used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) to evaluate the methodological quality of the studies (16). The scoring criteria of this scale include eight evaluation indicators: representativeness of the exposed cohort, selection of the unexposed cohort, exposure assessment, exclusion of individuals with relevant outcomes at the start of the study, comparability, outcome assessment, follow-up time, and adequacy of cohort follow-up. Each study is rated on a scale of 0 to 9, with the following quality classifications: low quality (0–3 points), moderate quality (4–6 points), and high quality (7–9 points). We assessed the risk of bias for each study based on these criteria. Additionally, we used the GRADE Pro 3.2 software to assess the quality of evidence for the meta-analysis results, evaluating each study based on research design type, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, and imprecision. The evidence quality is classified into three levels: high, moderate, and low. To ensure the objectivity and reliability of the assessment, two researchers independently performed the scoring.

2.4 Data extraction

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data on the relationship between childhood overweight/obesity and puberty development indicators in boys. Meta-analysis was performed to estimate the combined effect when two or more studies reported similar effect measurements for the same outcome. The primary outcomes included early testicular enlargement (testicular volume reaching Tanner Stage 2, ≥4 ml) and the age at early testicular enlargement. Secondary outcomes included the impact of waist circumference and body fat percentage on early testicular enlargement, the age of pubic hair development, and the age of peak height velocity (APHV).

Two researchers independently extracted the data based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, resolving any discrepancies through discussion with other researchers. The data extracted included: 1.Basic characteristics of the included studies: first author, publication date, study type, region, sample size, age, and follow-up frequency. 2.Outcome indicators: early testicular enlargement, the age of early testicular enlargement, waist circumference, body fat percentage, the appearance of pubic hair, and peak height velocity.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used as effect sizes to assess outcomes, with RR representing the effect measure in the analysis. Hazard ratios (HR) and odds ratios (OR) were treated as RR in the analysis. To avoid potential bias, the exact statistical methods for converting HR and OR to RR are as follows: for low event rates, log(HR) ≈ log(RR), and log(OR) ≈ log(RR). Some studies provided only the mean age and standard deviation for each puberty milestone under different weight statuses. In such cases, we calculated the mean difference and standard deviation between the two groups before performing the meta-analysis. The chi-square test was used to assess heterogeneity among the included studies. A P-value < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical heterogeneity, and the I² statistic was used to measure the degree of heterogeneity. I² values of < 25%, 25-50%, and > 50% were considered to represent low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively (17). If no significant heterogeneity was found, the fixed-effect model (Mantel-Haenszel) was used for data pooling; if significant heterogeneity was present, the random-effects model was applied, and subgroup analyses were performed to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was also conducted to assess the influence of individual studies on the results. To evaluate potential publication bias, funnel plots and Egger’s test were used, with a P-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Due to the limited number of studies on other outcomes, publication bias, sensitivity analysis, and subgroup analysis were only tested for the meta-analysis on early testicular enlargement.

All analyses, except for Egger’s test and sensitivity analysis, were conducted using Review Manager (version 5.4). Egger’s test and sensitivity analysis were performed using STATA (version 17.0, Computer Resource Center, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Literature search strategy and baseline characteristics

A search of selected public databases yielded 3,081 studies, which were screened, excluded, and quality-assessed based on the established inclusion and exclusion criteria. Ultimately, 12 cohort studies were included in this meta-analysis (10, 18–28). All included studies were prospective cohort studies conducted in English. The specific search process is shown in Figure 1, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the included studies. According to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) scores, 11 of the studies were rated as high quality, and 1 study was rated as moderate quality.

Table 1

| Author | Country | Sample Size | Age | Follow-up Frequency | Outcome Variables | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deardorff 2022 | USA | NW:64; OW:23; OB:49 | 5.0 | 7 assessments: 9–14 years | Testicular enlargement and pubic hair | High |

| Aghaee 2022 | USA | NW:46627; OW:9815; OB:9624 | 5.0–6.0 | ≥6 years, electronic medical records (2010–2021) | Testicular enlargement and pubic hair | High |

| Li 2022 | China | 645 | 9.1 (±0.6) | Every 6 months from 2017 to 2020 | Testicular enlargement | High |

| Fang 2022 | China | NW:317; OW/OB:62 | 9.03 (±0.98) | Annually | Testicular enlargement | High |

| Chen 2021 | USA | NW:422; OW:115; OB:126 | 2.0–7.0 | Pediatric follow-up until age 21 | Peak height velocity age | High |

| Pereira 2021 | Chile | NW:948; OW/OB:207 | 4.0 | Every 6 months starting at age 7 | Testicular enlargement | High |

| Brix 2020 | Denmark | NW:4588; OW:494; OB:407 | 7.1 (7.0–7.2) | Every 6 months starting at age 11.5 until age 18 or full maturity | Testicular volume reaching Tanner Stage 2, pubic hair development | High |

| Busch 2020 | Denmark | NW:536; OW:124; OB:218 | 4.2–17.0 | Assessments at enrollment and 1 year after enrollment | Testicular volume reaching Tanner Stage 2 and pubic hair development | moderate |

| Chen 2019 | China | 3109 | 10.0–12.0 | assessments from age 11, 12 to 18 | Testicular enlargement | High |

| Li 2018 | China | 537; OW:79; OB:68 | 8.59 (±1.20) | 7 follow-ups (every 6 months) | Testicular enlargement | High |

| Leonibus 2013 | Italy | NW: 27 OB: 44 | 9.07 (±0.52) |

Every 6 months until adult height is reached | Testicular volume reaching Tanner Stage 2 and peak height velocity | High |

| Lee 2025 | USA | 221764 | 8.43±0.69 | 7 assessments in national health insurance data (2008-2020) | Testicular enlargement and pubic hair | High |

Characteristics of Studies Included in the Systematic Review.

Note: Testicular enlargement is defined as the testicular volume reaching Tanner Stage 2; pubic hair is defined as the appearance of pubic hair. Abbreviations: AO, abdominal obesity; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; NW, normal weight; OB, obesity; OW, overweight (excluding obesity).

Bold values indicate the first author and year of publication.

Figure 1

Literature search flowchart.

3.2 Early testicular enlargement

3.2.1 Risk of early testicular enlargement

The meta-analysis on the risk of early testicular enlargement included 6 studies and found that overweight and obese boys had a higher risk of early testicular enlargement compared to normal-weight boys. For overweight boys, the risk ratio (RR) was 1.38 (95% CI, 1.15–1.65; I² = 72%, p = 0.0006), and for obese boys, the RR was 1.43 (95% CI, 1.18–1.73; I² = 74%, p = 0.0002) (Figure 2). Egger’s test and funnel plots indicated no publication bias (overweight: p = 0.186; obese: p = 0.143) (Figure 3). Subgroup analysis, as shown in Table 2, revealed regional differences in the association between overweight and early testicular enlargement. In the U.S., the RR (95% CI) for overweight boys was 1.11 (1.03–1.20), while in the Asia-Pacific region, the RR (95% CI) for overweight was 1.40 (1.22–1.60) (I² for subgroup difference = 88.4%; p for subgroup difference = 0.003). For obesity, no regional differences in effect estimates were observed (I² for subgroup difference = 71.4%; p for subgroup difference = 0.06). Additionally, we performed a subgroup analysis based on the baseline age at which the children’s weight was measured (≤6 years vs. >6 years). Among children with weight measurements taken after the age of 6, the association between overweight/obesity and early testicular enlargement was stronger. For instance, in children aged 6 years or younger, the RR (95% CI) for overweight was 1.15 (1.11–1.19), whereas for those older than 6 years, the RR (95% CI) for overweight was 1.53 (1.23–1.91) (I² for subgroup difference = 84.3%; p for subgroup difference = 0.01). Similar subgroup differences were observed for obese boys. Further subgroup analysis based on the sample size of the included studies showed significant differences between groups for overweight boys in terms of early testicular enlargement (I² for subgroup difference = 83.2%; p for subgroup difference = 0.01). Additionally, two studies combined overweight and obese boys into one group. Compared to normal-weight boys, the results showed that overweight or obese boys had a higher risk of early testicular enlargement (combined RR = 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00–1.08; I² = 0%, p = 0.05) (Figure 4A).

Table 2

| Early Testicular Enlargement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity | Overweight | |||||

| Study Quantity | RR[95%CI] | P | Study Quantity | RR[95%CI] | P | |

| Region | 0.06 | 0.003* | ||||

| Asia | 4 | 1.47 [1.23, 1.76] | <0.0001 | 4 | 1.40 [1.22, 1.60] | <0.00001 |

| USA | 3 | 1.19 [1.04, 1.36] | 0.009 | 2 | 1.11 [1.03, 1.20] | 0.005 |

| Age of Weight Measurement | <0.0001* | 0.01* | ||||

| ≤6 years | 3 | 1.22 [1.18, 1.26] | <0.00001 | 2 | 1.15 [1.11, 1.19] | <0.00001 |

| >6 years | 4 | 1.62 [1.43, 1.83] | <0.00001 | 3 | 1.53 [1.23, 1.91] | 0.0001 |

| Sample Size | 0.68 | 0.01 | ||||

| Sample Size ≤5000 | 4 | 1.50 11.15,1.96] | 0.003 | 3 | 1.68 [1.34, 2.12] | <0.00001 |

| Sample Size >5000 | 2 | 1.39 [1.06, 1.81] | 0.02 | 2 | 1.21 [1.06, 1.38] | 0.006 |

Subgroup Analysis of Early Testicular Enlargement.

Bold values indicate the subgroup categories and the p values from the statistical analyses.

Figure 2

Meta-analysis forest plot of early testicular enlargement in obese (A) or overweight (B) boys during puberty.

Figure 3

![Side-by-side funnel plots labeled A and B. Both plots show circles representing data points along a vertical axis labeled “SE(log[RR])” with horizontal values labeled “RR” ranging from 0.01 to 100. Both plots have a vertical dashed blue line at RR equal to one. Plot A shows data primarily clustered around the center, with one outlier on the right. Plot B has data more evenly distributed around the line, with no significant outliers.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1711557/xml-images/fendo-16-1711557-g003.webp)

Meta-analysis funnel plot of early testicular enlargement in obese (A) or overweight (B) boys during puberty.

Figure 4

Meta-analysis forest plot of factors associated with early testicular enlargement in boys during puberty ((A) combined overweight and obesity, (B) age of testicular enlargement in obese boys, (C) age of testicular enlargement in overweight boys, (D) waist circumference and body fat percentage).

3.2.2 Age of early testicular enlargement

The meta-analysis results indicated that overweight boys experienced earlier testicular enlargement compared to normal-weight boys. However, no significant difference was observed in the obese group (overweight: MD = -0.23, 95% CI: -0.37 to -0.08, p = 0.002; obesity: MD = -0.23, 95% CI: -0.37 to 0.08, p = 0.10) (Figures 4B, C).

3.2.3 Impact of waist circumference and body fat percentage on early testicular enlargement in boys

Two studies on abdominal obesity and the risk of testicular enlargement were included, and the results showed that boys with abdominal obesity had an increased risk of early testicular enlargement (RR = 1.67; 95% CI: 1.17–2.38; I² = 0%, p = 0.004) (Figure 4D).

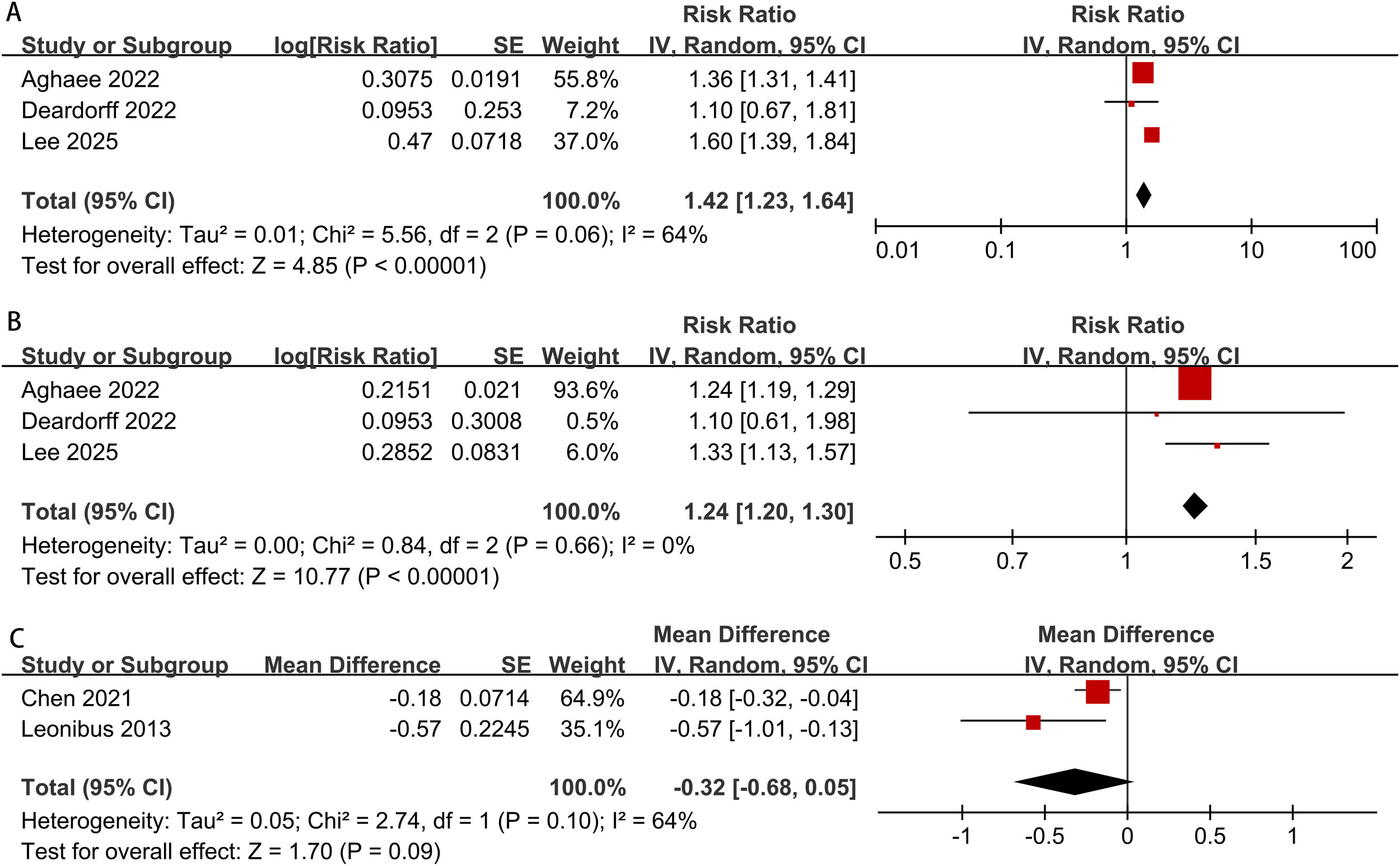

3.3 Pubic hair development

The meta-analysis results showed that overweight or obese boys had a higher risk of early pubic hair development compared to normal-weight boys (overweight: RR = 1.24; 95% CI: 1.20–1.30; I² = 0%, p < 0.00001; obesity: RR = 1.42; 95% CI: 1.23–1.64; I² = 0%, p < 0.00001) (Figures 5A, B).

Figure 5

Meta-analysis forest plot of obesity and overweight in boys during puberty ((A) obesity and pubic hair development, (B) overweight and pubic hair development, (C) obesity and peak height velocity).

3.4 Peak height velocity

The meta-analysis results revealed no significant statistical difference in peak height velocity between obese boys and normal-weight boys (MD = -0.32, 95% CI: -0.68 to 0.05, I² = 64%, p = 0.09) (Figure 5C).

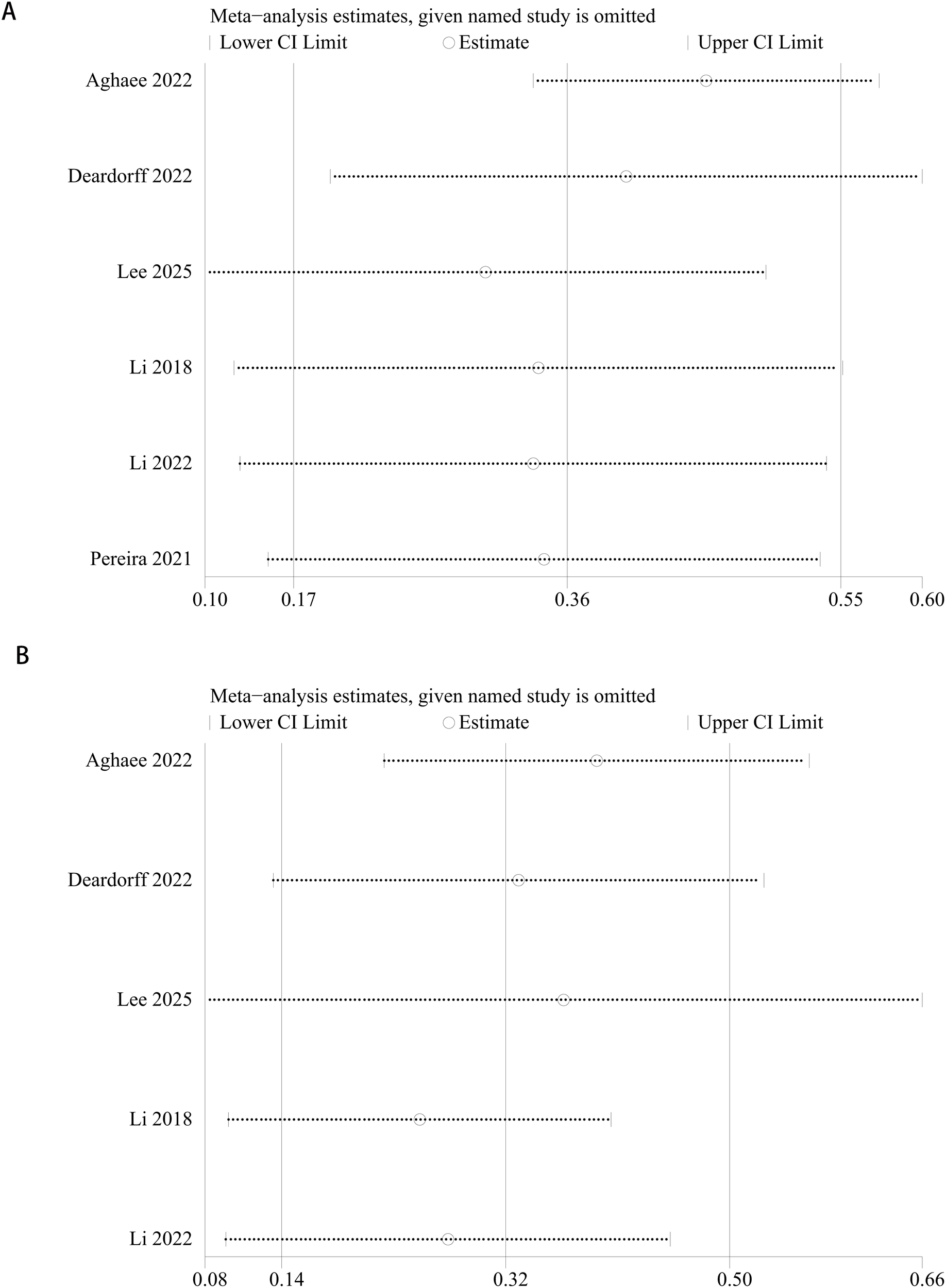

3.5 Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed on the risk of early testicular enlargement in overweight and obese boys by assessing the impact of excluding each study on the overall RR value. The results showed that excluding any individual study did not significantly change the RR value (p > 0.05), suggesting that our findings are robust and reliable. For details, see Figure 6.

Figure 6

Sensitivity analysis of the meta-analysis on early testicular enlargement in obese (A) or overweight (B) boys during puberty.

3.6 Grade system

The GRADE system assessment indicated that the evidence quality for the risk of early testicular enlargement was high. However, the evidence quality for the age of testicular enlargement, pubic hair development, impact of waist circumference and body fat percentage on early testicular and peak height velocity was moderate, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

| Outcome | Number of Studies Included | Evidence Quality Assessment | Evidence Level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias Risk | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other Factors | |||

| Risk of Early Testicular Enlargement | 6 | N | N | N | N | N | High |

| Age of Testicular Enlargement | 3 | S | N | N | N | N | moderate |

| Impact of Waist Circumference and Body Fat Percentage on Early Testicular Enlargement in Boys | 2 | S | N | N | N | N | moderate |

| Pubic Hair Development | 3 | S | N | N | N | N | moderate |

| Age of Peak Height Velocity | 2 | S | N | N | N | N | moderate |

Evidence Quality Assessment Results using the GRADEpro System.

4 Discussion

This study systematically reviewed and summarized 12 cohort studies to assess the impact of overweight and obesity on male puberty development, focusing on key puberty events such as testicular enlargement, pubic hair development, and peak height velocity. We found that overweight and obese boys had a significantly higher risk of early testicular enlargement compared to normal-weight boys (overweight: RR 1.38; 95% CI, 1.15–1.65; I² = 72%, p = 0.0006; obesity: RR 1.43; 95% CI, 1.18–1.73; I² = 74%, p = 0.0002). This conclusion was confirmed through multiple subgroup analyses, particularly for children over the age of 6, where the association between overweight and early testicular enlargement was more pronounced (RR [95% CI] = 1.53 [1.23–1.91]). Additionally, overweight boys showed earlier pubic hair development compared to normal-weight boys.

The outcome measures used to assess male puberty development were not consistent across studies, with most evaluating development based on the age of testicular enlargement. In addition to testicular enlargement, other indicators such as the age of testicular enlargement, pubic hair appearance, peak height velocity, first ejaculation, and voice changes were also considered (29). However, due to the limited number of studies addressing these outcomes, meta-analysis could not be performed for all factors. The study by Li et al. found that a higher prepubertal body mass index in boys was significantly associated with the timing of first ejaculation (HR: 1.054, 95% CI: 1.004–1.106) and testicular development (HR: 1.098, 95% CI: 1.063–1.135) (25). Another cohort study found that, among 5,489 Danish boys, the first ejaculation occurred 0.13 years earlier in overweight boys and 0.23 years earlier in obese boys compared to normal-weight boys. Furthermore, a cohort study involving 1,434 Chinese boys found that overweight/obese boys had a higher risk of early voice changes compared to normal-weight boys (OR: 1.05; 95% CI: 1.02–1.08; P < 0.05) (10).

Research on the impact of obesity and overweight on girls’ puberty development is relatively consistent, with a general consensus that obesity leads to early puberty in girls. Numerous studies have shown that overweight or obese girls experience menarche and breast development earlier than their normal-weight counterparts, and this association has been validated across multiple races and regions (30). For instance, a study conducted in the U.S. and Europe found that for every one standard deviation increase in girls’ BMI, the age of menarche would advance by approximately 4.5 months (23). Other research has suggested that higher body fat levels in girls during early puberty, along with changes in hormones such as leptin and insulin, may play a key role in driving early sexual maturation (31).

However, research on the impact of obesity on male puberty development is more limited and somewhat controversial. Some studies suggest that obesity does not significantly affect male puberty development. For example, a previous study by Li et al. found that obesity did not significantly advance the age of testicular enlargement or the onset of first ejaculation in boys (13). Additionally, research by Thomas Reinehr and colleagues did not confirm that obese boys enter puberty earlier than normal-weight boys. The researchers proposed that the onset of puberty in boys is influenced by a broader range of endocrine factors, not just weight (32, 33). Despite these findings, an increasing number of studies suggest that obesity also affects male puberty development, leading to early sexual maturation. A large cohort study found that obese boys experience earlier testicular enlargement and first ejaculation compared to normal-weight boys (27). Another study indicated that overweight and obese boys reach earlier puberty milestones, such as testicular development and body hair growth, with obese boys being at a higher risk for early puberty (RR = 1.90; 95% CI [1.30–2.78]) (19). These studies suggest that obesity leads to hormonal changes, particularly an imbalance between androgens and estrogens, which may be a key factor driving early sexual maturation in boys.

Puberty is a critical developmental phase for boys, bringing about significant physical, hormonal, and psychological changes (34, 35). During this period, the body undergoes rapid growth and maturation, including the enlargement of reproductive organs, the development of secondary sexual characteristics such as pubic hair, and an increase in muscle mass. Hormonal changes, particularly the secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), testosterone, and growth hormone, play a central role in driving these changes (36, 37). Research has shown that obesity disrupts the hormonal signals regulating puberty, thereby influencing male development and accelerating the onset of puberty. In addition to hormonal imbalances, obesity leads to insulin resistance and associated metabolic disturbances, which further affect the timing of puberty and the development of secondary sexual characteristics (38).

The interaction between obesity and puberty is crucial for understanding male development, as both factors seem to amplify each other’s effects. Puberty, by increasing hormonal activity, may exacerbate the metabolic disruptions caused by obesity, creating a feedback loop that accelerates physical and hormonal changes. This cyclical interaction underscores the complexity of the relationship between obesity and puberty in boys (39). Existing studies have proposed several potential mechanisms for the relationship between obesity/overweight and early puberty development in boys. One key mechanism is that obesity may accelerate the onset of puberty by increasing the activity of aromatase, which promotes the conversion of androgens to estrogens. Aromatase expression is higher in fat tissue, and the elevated estrogen levels in obese children may lead to early activation of the gonadal axis, thereby prompting early puberty onset. Related studies have shown that obese children are exposed to higher levels of estrogen in their tissues, which may be a key factor in the early onset of puberty in these children (40). Additionally, obesity may promote early puberty by influencing the secretion and sensitivity of hormones in the body. In particular, leptin levels are typically higher in obese children compared to normal-weight children. Leptin is an important endocrine signaling molecule that regulates energy balance and influences reproductive system development. As body weight increases, leptin levels gradually rise, which may be a critical factor in the early onset of puberty in obese children (41). Leptin acts on the hypothalamus to stimulate the secretion of kisspeptin, which in turn activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, promoting the secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and ultimately triggering the synthesis and secretion of sex hormones, thus driving the progression of puberty.

Moreover, obese children often experience insulin resistance, leading to elevated insulin levels, which may further disrupt hormone balance. Studies have shown that the interaction between insulin and sex hormones significantly impacts the onset of puberty. Elevated insulin levels may promote early sexual maturation by affecting the synthesis of estrogens and androgens or by directly acting on the gonads (42). While existing research has proposed biological mechanisms for the association between obesity/overweight and early puberty in boys, many unknowns remain. Future studies should explore these mechanisms through larger sample sizes and more rigorous experimental designs and investigate whether these mechanisms differ from those in girls.

This study has several limitations. First, all the included studies were observational, meaning causality cannot be determined, and the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Second, differences in sample sizes and regions may introduce heterogeneity in the results, as most studies focused on specific regions, which could limit the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, due to the limited number of studies included, the statistical power of the funnel plot and Egger test for assessing publication bias may be insufficient, and the results of the subgroup analysis and certain outcomes are only suggestive. Lastly, the definition and assessment methods for the onset of puberty varied across studies. Indicators such as first ejaculation, voice changes, and puberty development in boys with different BMI trajectories lacked sufficient data for meta-analysis. Future research should employ more precise measurement tools and standardized methods to validate these findings. The strength of this study lies in its systematic review and meta-analysis methodology, which synthesizes data from several high-quality cohort studies and provides robust evidence for the relationship between obesity/overweight and early puberty development in boys. Unlike previous studies, this study specifically focuses on the male population, addressing a significant research gap. Additionally, the use of strict inclusion criteria and various analytical methods enhances the reliability and generalizability of the results. By analyzing multiple key puberty milestones, we were able to offer a comprehensive assessment of the impact of obesity on puberty.

5 Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis shows a significant association between overweight/obesity and early puberty development in boys, particularly with regard to testicular enlargement, pubic hair development, and the impact of waist circumference and body fat percentage on early testicular enlargement. Compared to normal-weight boys, overweight and obese boys have a significantly higher risk of early testicular enlargement. Subgroup analysis suggests that this association is more pronounced in children older than 6 years. Although no significant difference in peak height velocity was observed between obese and normal-weight boys, overweight and obesity still significantly affect male puberty development. Given the limited number of studies included in this meta-analysis, future research should validate these findings through large-scale cohort studies with more rigorous methodologies.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

WF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abreu AP Kaiser UB . Pubertal development and regulation. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2016) 4:254–64. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00418-0

2

Dunkel L Quinton R . Transition in endocrinology: induction of puberty. Eur J Endocrinol. (2014) 170:R229–39. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0894

3

Terasawa E Fernandez DL . Neurobiological mechanisms of the onset of puberty in primates. Endocr Rev. (2001) 22:111–51. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.1.0418

4

Elks CE Ong KK Scott RA van der Schouw YT Brand JS Wark PA et al . Age at menarche and type 2 diabetes risk: the EPIC-InterAct study. Diabetes Care. (2013) 36:3526–34. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0446

5

Soliman A De Sanctis V Elalaily R . Nutrition and pubertal development. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. (2014) 18:S39–47. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.145073

6

Sun H Ma Y Han D Pan CW Xu Y . Prevalence and trends in obesity among China’s children and adolescents, 1985-2010. PloS One. (2014) 9:e105469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105469

7

Ogden CL Carroll MD Kit BK Flegal KM . Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. Jama. (2014) 311:806–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732

8

Tzounakou AM Stathori G Paltoglou G Valsamakis G Mastorakos G Vlahos NF et al . Childhood obesity, hypothalamic inflammation, and the onset of puberty: A narrative review. Nutrients. (2024) 16. doi: 10.3390/nu16111720

9

Burt Solorzano CM McCartney CR . Obesity and the pubertal transition in girls and boys. Reproduction. (2010) 140:399–410. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0119

10

Chen YC Fan HY Yang C Hsieh RH Pan WH Lee YL . Assessing causality between childhood adiposity and early puberty: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization and longitudinal study. Metabolism. (2019) 100:153961. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.153961

11

Bauman D . Impact of obesity on female puberty and pubertal disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. (2023) 91:102400. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2023.102400

12

Jiang M Gao Y Wang K Huang L . Lipid profile in girls with precocious puberty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Endocr Disord. (2023) 23:225. doi: 10.1186/s12902-023-01470-8

13

Li W Liu Q Deng X Chen Y Liu S Story M . Association between obesity and puberty timing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14101266

14

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

15

Shea BJ Reeves BC Wells G Thuku M Hamel C Moran J et al . AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. Bmj. (2017) 358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008

16

Stang A . Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. (2010) 25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z

17

Higgins JP Thompson SG Deeks JJ Altman DG . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical Res ed). (2003) 327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

18

Deardorff J Reeves JW Hyland C Tilles S Rauch S Kogut K et al . Childhood overweight and obesity and pubertal onset among mexican-american boys and girls in the CHAMACOS longitudinal study. Am J Epidemiol. (2022) 191:7–16. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwab100

19

Li Y Ma T Ma Y Gao D Chen L Chen M et al . Adiposity status, trajectories, and earlier puberty onset: results from a longitudinal cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2022) 107:2462–72. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac395

20

Fang J Yuan J Zhang D Liu W Su P Wan Y et al . Casual associations and shape between prepuberty body mass index and early onset of puberty: A mendelian randomization and dose-response relationship analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2022) 13:853494. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.853494

21

Chen LK Wang G Bennett WL Ji Y Pearson C Radovick S et al . Trajectory of body mass index from ages 2 to 7 years and age at peak height velocity in boys and girls. J Pediatr. (2021) 230:221–9.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.047

22

Pereira A Busch AS Solares F Baier I Corvalan C Mericq V . Total and central adiposity are associated with age at gonadarche and incidence of precocious gonadarche in boys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2021) 106:1352–61. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab064

23

Brix N Ernst A Lauridsen LLB Parner ET Arah OA Olsen J et al . Childhood overweight and obesity and timing of puberty in boys and girls: cohort and sibling-matched analyses. Int J Epidemiol. (2020) 49:834–44. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa056

24

Busch AS Højgaard B Hagen CP Teilmann G . Obesity is associated with earlier pubertal onset in boys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2020) 105:e1667–e1672. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgz222

25

Li W Liu Q Deng X Chen Y Yang B Huang X et al . Association of prepubertal obesity with pubertal development in Chinese girls and boys: A longitudinal study. Am J Hum Biol. (2018) 30:e23195. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.23195

26

De Leonibus C Marcovecchio ML Chiavaroli V de Giorgis T Chiarelli F Mohn A . Timing of puberty and physical growth in obese children: a longitudinal study in boys and girls. Pediatr Obes. (2014) 9:292–9. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00176.x

27

Aghaee S Deardorff J Quesenberry CP Greenspan LC Kushi LH Kubo A . Associations between childhood obesity and pubertal timing stratified by sex and race/ethnicity. Am J Epidemiol. (2022) 191:2026–36. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwac148

28

Lee M Kim J Kim H Shin J Suh J . Early life factors of precocious puberty based on Korean nationwide data. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:16165. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-98529-4

29

Tinggaard J Mieritz MG Sørensen K Mouritsen A Hagen CP Aksglaede L et al . The physiology and timing of male puberty. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. (2012) 19:197–203. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283535614

30

Kim MR Jung MK Yoo EG . Slower progression of central puberty in overweight girls presenting with precocious breast development. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. (2023) 28:178–83. doi: 10.6065/apem.2244062.031

31

Stathori G Tzounakou AM Mastorakos G Vlahos NF Charmandari E Valsamakis G . Alterations in appetite-regulating hormones in girls with central early or precocious puberty. Nutrients. (2023) 15. doi: 10.3390/nu15194306

32

Reinehr T Roth CL . Is there a causal relationship between obesity and puberty? Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2019) 3:44–54. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30306-7

33

Surboyo MDC Baroutian S Puspitasari W Zubaidah U Cecilia Pamela H Mansur D et al . Health benefits of liquid smoke from various biomass sources: a systematic review. Bio Integration. (2024) 5:1–19. doi: 10.15212/bioi-2024-0083

34

Vijayakumar N Op de Macks Z Shirtcliff EA Pfeifer JH . Puberty and the human brain: Insights into adolescent development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2018) 92:417–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.06.004

35

Aguirre RS Eugster EA . Central precocious puberty: From genetics to treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2018) 32:343–54. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2018.05.008

36

Alenazi MS Alqahtani AM Ahmad MM Almalki EM AlMutair A Almalki M . Puberty induction in adolescent males: current practice. Cureus. (2022) 14:e23864. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23864

37

Abacı A Besci Ö . A current perspective on delayed puberty and its management. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. (2024) 16:379–400. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2024.2024-2-7

38

Huang A Roth CL . The link between obesity and puberty: what is new? Curr Opin Pediatr. (2021) 33:449–57.

39

Veldhuis JD Iranmanesh A . Physiological regulation of the human growth hormone (GH)-insulin-like growth factor type I (IGF-I) axis: predominant impact of age, obesity, gonadal function, and sleep. Sleep. (1996) 19:S221–4. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.suppl_10.s221

40

Mesa Valencia DC Mericq V Corvalán C Pereira A . Obesity and related metabolic biomarkers and its association with serum levels of estrogen in pre-pubertal Chilean girls. Endocr Res. (2020) 45:102–10. doi: 10.1080/07435800.2019.1681448

41

Shalitin S Phillip M . Role of obesity and leptin in the pubertal process and pubertal growth–a review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. (2003) 27:869–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802328

42

Luo Y Luo D Li M Tang B . Insulin resistance in pediatric obesity: from mechanisms to treatment strategies. Pediatr Diabetes. (2024) 2024:2298306. doi: 10.1155/2024/2298306

Summary

Keywords

boys, childhood obesity, puberty development, testicular enlargement, pubic hair development, peak height velocity

Citation

Feng W and Ren C (2025) The relationship between childhood obesity and male puberty development: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 16:1711557. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2025.1711557

Received

23 September 2025

Accepted

31 October 2025

Published

27 November 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Sally Radovick, The State University of New Jersey, United States

Reviewed by

Farzad Pourghazi, Mayo Clinic, United States

Richard Ivell, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom

Yong Zhang, Chongqing Medical University, China

Sanja Panic Zaric, The Institute for Health Protection of Mother and Child Serbia, Serbia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Feng and Ren.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenhua Feng, drfengwenhua@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.