- 1Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, Jilin, China

- 2Affiliated Hospital of Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Heart Disease Center, Changchun, Jilin, China

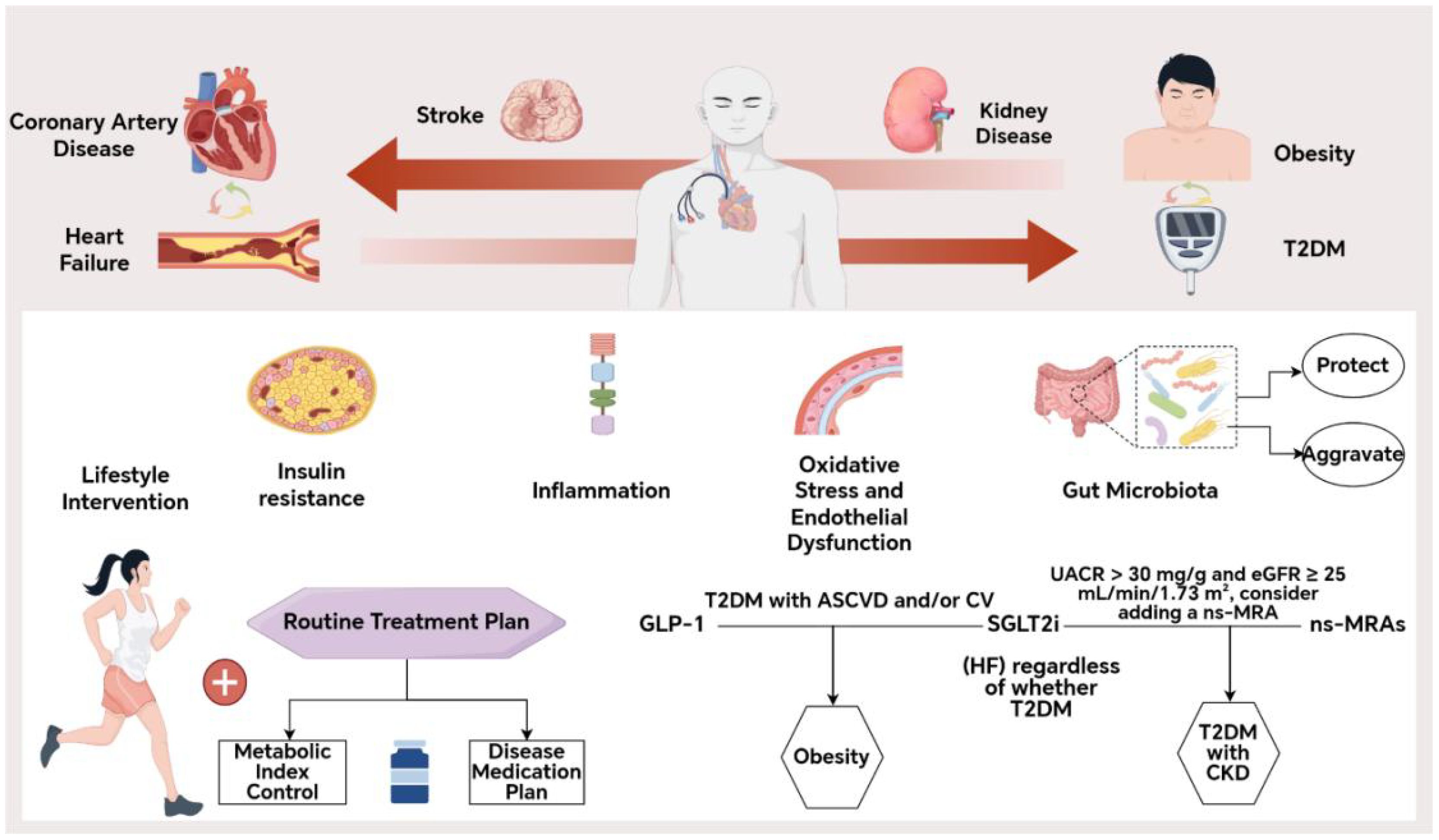

Cardiometabolic multimorbidity (CMM), defined as the simultaneous presence of two or more cardiovascular and metabolic diseases in an individual, including but not limited to type 2 diabetes(T2D), chronic kidney disease(CKD), heart failure(HF), stroke, and obesity, constitutes an expanding global burden that challenges the prevailing single-disease paradigm of contemporary therapeutic interventions. Yet routine care is often guided by single-disease guidelines, yielding treatment plans that are siloed, polypharmacy-heavy, and potentially conflicting. Emerging evidence from large-scale outcome trials (2020–2025) and translational studies demonstrates that pharmacologic agents originally developed for glucose control exert multi-organ protective effects through distinct mechanistic pathways and these agents consistently reduced cardiovascular and renal events beyond glycemic control, with additive benefits when appropriately combined. This review indicates that sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists should be prioritized based on phenotypic characteristics, while Non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist should be considered for use in chronic kidney disease phenotypes. Moreover, the implementation of threshold monitoring protocols is imperative in order to mitigate the risk of hypoglycemia, hypotension, and hyperkalemia. This mechanism-based optimization of therapeutic strategies provides significant guidance for the management of cardiometabolic syndrome and shows promise in improving clinical outcomes for patients suffering from comorbid cardiometabolic diseases. It is recommended that future research concentrate on patient populations with overlapping phenotypes, with a view to refining the decision criteria for treatment de-escalation or discontinuation.

Highlights

● Mechanism-guided care aligns pathophysiology with phenotype-prioritized pharmacotherapy in CMM.

● SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and finerenone deliver multi-organ protection beyond glycemia.

● Combination and sequencing strategies reduce cardiovascular–renal events while curbing polypharmacy.

● Practical de-escalation and safety thresholds (hypoglycemia, hypotension, hyperkalemia) improve net benefit.

● A phenotype-based decision table supports precision prescribing across ASCVD, HF, CKD and obesity.

Introduction

The escalating burden of multimorbidity

The global prevalence of cardiometabolic multimorbidity (CMM)—with diabetes at its core—continues to rise and has become a major public-health challenge (1). Projections from the Global Burden of Cardiovascular Disease, 2020–2025, indicate that metabolic risk factors will remain the principal drivers of cardiovascular mortality (2). In a long-term cohort including 1.2 million participants, cardiometabolic multimorbidity was associated with a substantial reduction in life expectancy (3). This clustering of conditions not only markedly increases all-cause mortality, the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events, and hospitalizations, but also imposes a considerable economic burden on health systems. Although a number of clinical practice guidelines for individual cardiovascular or metabolic conditions have been developed both nationally and internationally, most are formulated from a single-disease perspective and lack comprehensive recommendations for multimorbidity management. In clinical practice, physicians often rely on multiple independent guidelines to develop treatment plans for patients with CMM, which may result in polypharmacy, increased risk of drug–drug interactions, decreased patient adherence, and cumulative adverse drug events. Furthermore, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases are pathophysiologically interconnected. Numerous studies have demonstrated that metabolic abnormalities—such as insulin resistance—can significantly influence the onset and progression of cardiovascular diseases (4, 5). However, current clinical strategies rarely adopt an integrated mechanistic approach to managing multimorbidity, making it difficult to simultaneously maximize therapeutic benefit and minimize pharmacologic risk.

Against this backdrop, the present review systematically summarizes recent advances (2020–2025) in the understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms underlying CMM. Special emphasis is placed on the clinical evidence and application of various therapeutic agents, including sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA), in the management of CMM. This review also seeks comprehensive clinical strategies for the optimization of multimorbidity care. To provide certain guiding significance for the precision medicine of comorbid populations.

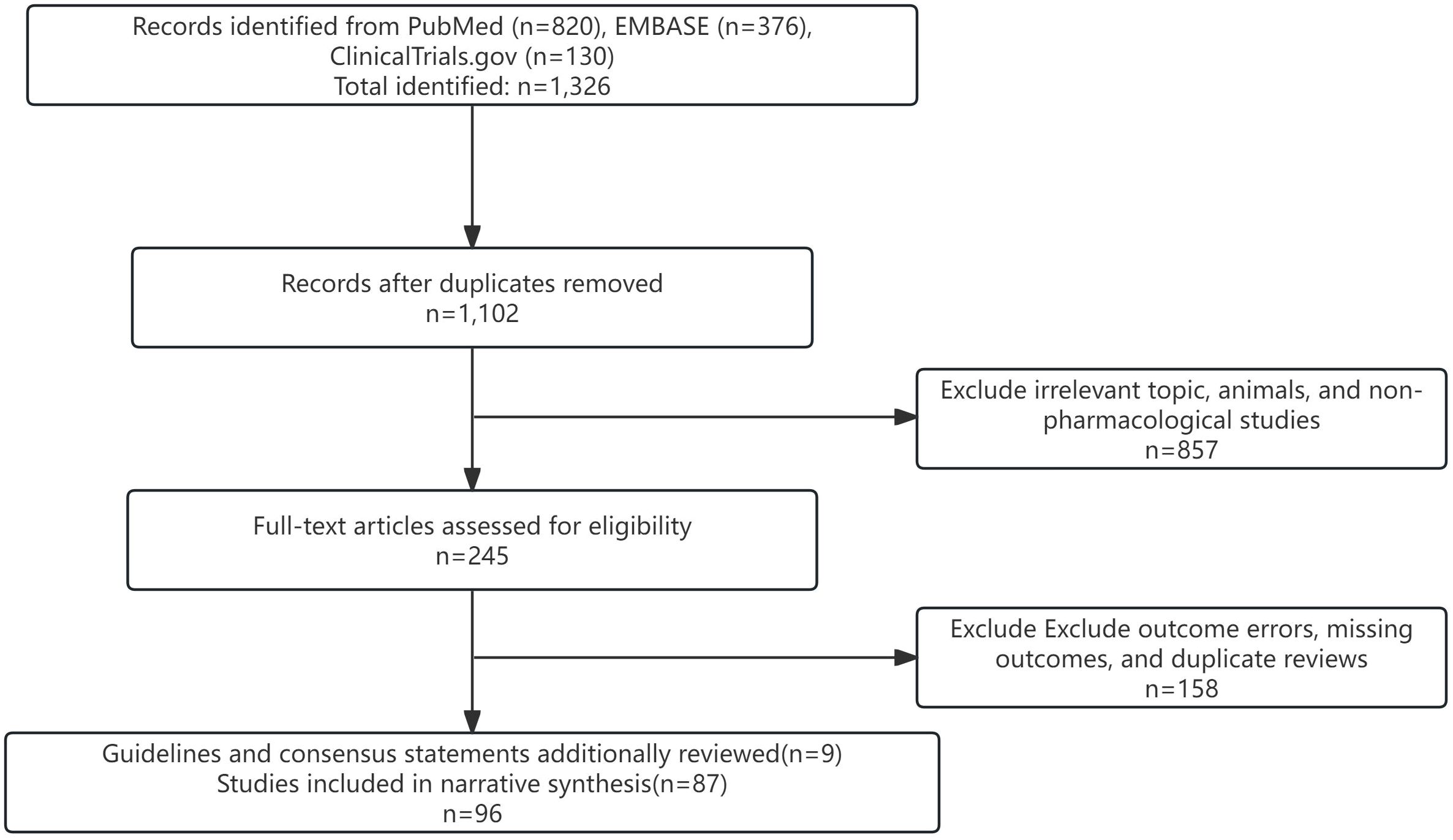

Methods

To capture high-quality evidence as comprehensively as possible, the authors conducted a structured search of PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, and Embase for studies published between January 2020 and July 2025. The strategy centered on the core topic and combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) with free-text terms, for example:”(‘cardiometabolic multimorbidity’ OR ‘heart failure’ OR ‘coronary artery disease’) AND (‘type 2 diabetes’ OR ‘obesity’ OR ‘dyslipidemia’) AND (‘pathophysiology’ OR ‘mechanism’ OR ‘drug therapy’ OR ‘polypharmacy’ OR ‘deprescribing’).” (Figure 1). Complete search syntax are provided in Supplementary Material S1 for transparency.

Inclusion criteria were published randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, systematic reviews, translational studies, and large observational cohorts; populations with coexisting cardiovascular and metabolic diseases; and a focus on mechanistic insights, pharmacologic interventions, and clinical outcomes. Exclusion criteria were animal studies, case reports, records without an accessible abstract and full text and studies lacking substantive mechanistic or therapeutic findings.

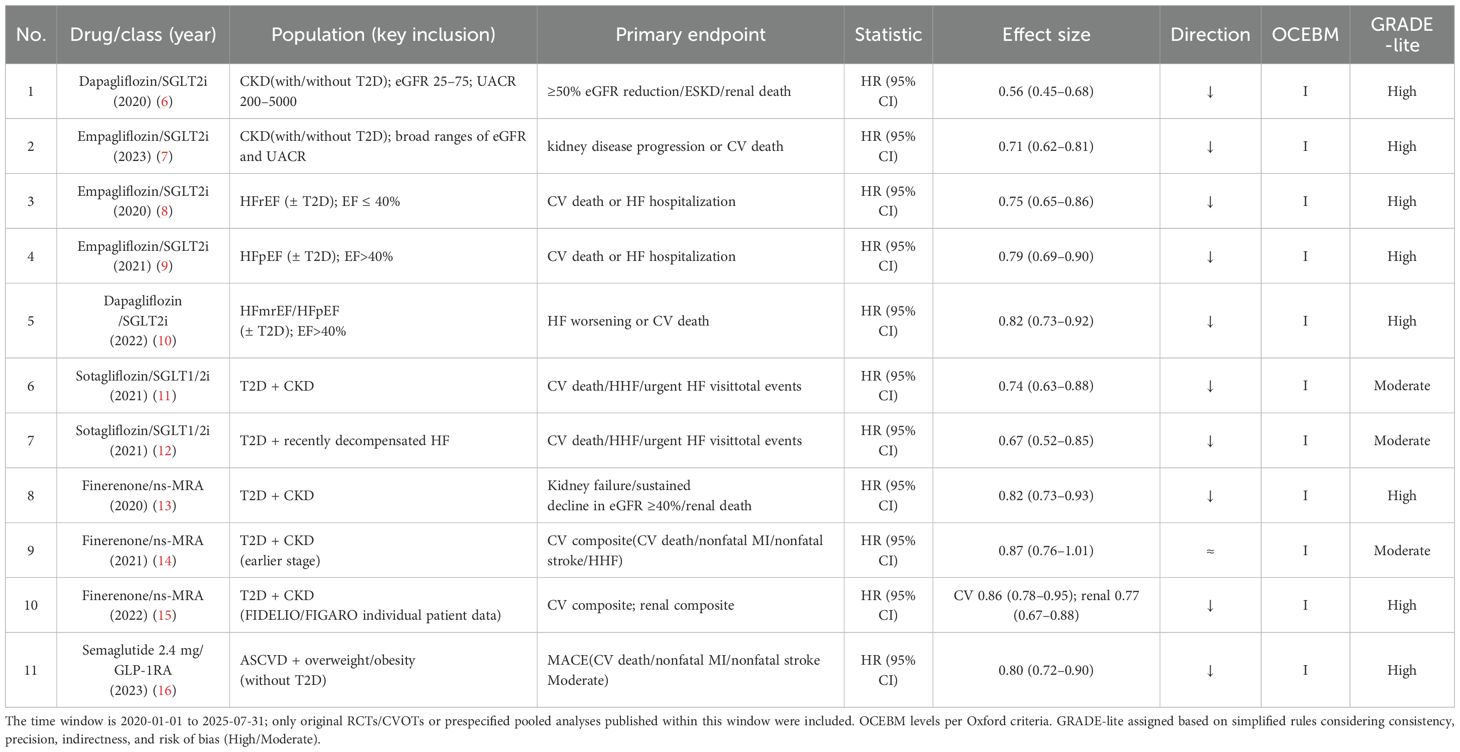

This paper is a narrative review. However, to ensure the quality of evidence in the included studies, three authors independently screened titles and abstracts and critically assessed methodological quality, sample size, consistency of results, and clinical relevance. Disagreements were resolved by the corresponding author. Although a formal PRISMA workflow was not undertaken, the Appendix details the full search strings, deduplication log, and selection notes. Priority was given to pivotal, large RCTs; influential experimental and translational work; high-impact systematic reviews and meta-analyses; and the most recent clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements from relevant professional societies. Evidence levels were assigned using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM) framework (Levels I–V). Certainty ratings were presented in parallel using a simplified GRADE approach (“GRADE-lite”: high/moderate/low), with up-/downgrading based on consistency, precision, indirectness, and risk of bias (Table 1).

Mechanistic insights

The central pathophysiologic role of insulin resistance

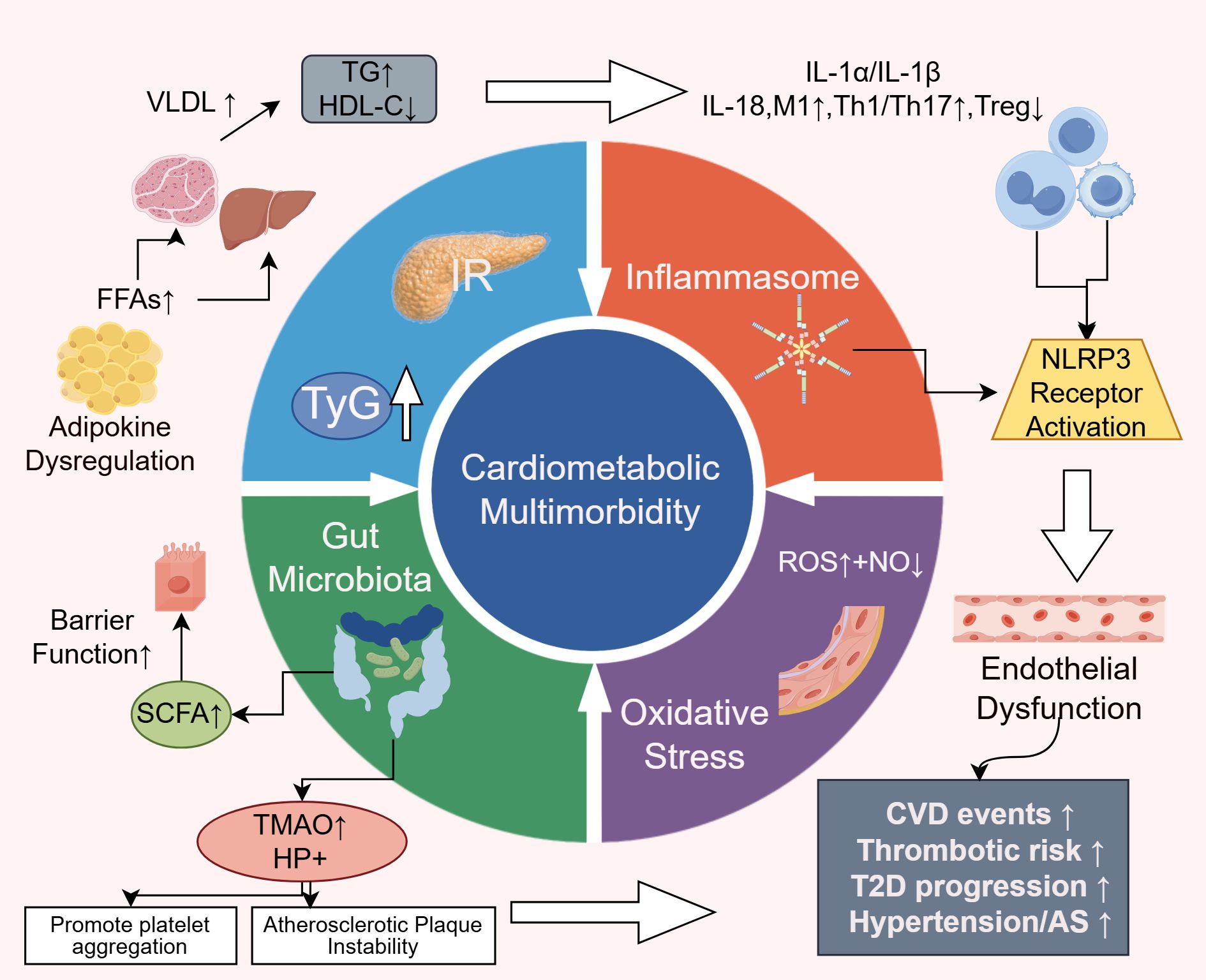

Insulin resistance (IR) has long been recognized as a key pathophysiological mechanism underlying both cardiovascular and metabolic diseases (17). The triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index, a reliable surrogate marker for IR, has been shown to be associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (18, 19). Recent studies have not only reinforced this association but also elucidated its downstream effects in greater detail.

Dysregulated lipid-derived metabolic mediators—such as adipokines, excess lipids, and toxic lipid metabolites—released from adipose tissue contribute significantly to the development of IR (20). These adipose-derived factors can impair cardiomyocyte signaling, induce structural remodeling of the heart, and increase the incidence of CVD. They are also closely linked to the pathogenesis of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (21).Excess circulating free fatty acids (FFAs) infiltrate the liver and skeletal muscle, enhancing gluconeogenesis and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) synthesis, thereby promoting hepatic and muscular insulin resistance (22). Hepatic IR leads to increased endogenous glucose production and elevated fasting plasmaglucose, which subsequently raises serum triglyceride (TG) levels and lowers high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), heightening thrombogenic risk (23).

In the insulin-resistant state, elevated insulin and aldosterone levels reduce nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, leading to endothelial dysfunction and pathological arterial stiffening. This process also activates MAPK/ERK-mediated reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, further increasing cardiovascular risk (17, 24). Additionally, recent evidence indicates that lipid accumulation in pancreaticβ-cells under IR conditions accelerates β-cell apoptosis and senescence, perpetuating a vicious cycle of metabolic deterioration (25, 26).IR is the pathological hub of CMM and links lipotoxicity, endothelial dysfunction and β-cell failure. Therefore, a drug combination that improves insulin resistance and reduces fat/weight serves as the starting point for downstream, multi-organ benefits.

Activation of the inflammasome pathway

Inflammation plays a central role in the cardiometabolic disease continuum (27). Over the past five years, research has expanded beyond traditional inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), moving toward cellular and molecular mechanisms. The activation of the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome has emerged as a pivotal molecular platform linking metabolic stressors—such as cholesterol crystals, hyperglycemia, and FFAs—to the release of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-18. These cytokines not only impair glucose metabolism and exacerbate IR (28, 29), but also activate vascular endothelial cells, promote monocyte adhesion, and damage cardiomyocytes, thereby accelerating the progression and instability of atherosclerotic plaques (30).

Immunological studies have further demonstrated that metabolic dysregulation leads to immune cell phenotype shifts and tissue infiltration. Specifically, M1-type macrophage polarization, expansion of pro-inflammatory T-cell subsets (Th1, Th17), and reduction in regulatory T cells (Tregs) have been observed in adipose tissue, liver, vasculature, and myocardium (31). These alterations contribute to local and systemic inflammatory microenvironments, providing strong evidence for the interplay between immunity and metabolic disease progression (32–34). The inhibition of the NLRP3-mediated inflammatory pathway provides a mechanistic basis for the combined use of SGLT2i and ns-MRA in reducing residual inflammation-fibrosis risk.

Oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction

Oxidative stress constitutes a shared pathological axis linking inflammation and insulin resistance, further perpetuating their vicious interplay. Under hyperglycemic and hyperlipidemic conditions, mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) increases significantly. At elevated levels, ROS disrupt cellular redox homeostasis and overwhelm endogenous antioxidant defenses (35). Excess ROS directly oxidize DNA, proteins, and lipids, and also activate multiple stress-sensitive kinases and transcription factors such as NF-κB, aggravating both inflammation and IR (36, 37).

Superoxide anions (a form of ROS) rapidly react with endothelial-derived nitric oxide (NO), reducing NO bioavailability and generating highly reactive peroxynitrite radicals (38). This reaction is a hallmark of endothelial dysfunction and is considered a critical initiating event in atherosclerosis and hypertension (39, 40).

Gut microbiota

In recent years, growing clinical interest has focused on the role of gut microbiota dysbiosis in cardiometabolic diseases. Although causality remains to be fully established, its relevance to the pathogenesis of cardiometabolic multimorbidity is increasingly recognized. The gut microbiota is now regarded as a “quasi-endocrine organ” due to its systemic metabolic influence (41, 42).

Emerging studies have introduced the dietary index of gut microbiota (DI-GM), suggesting that a higher DI-GM score is associated with reduced CMM risk—mediated in part by attenuation of systemic inflammation (43). Fermentation of dietary fiber by beneficial gut bacteria produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which improve gut barrier integrity and exert systemic effects including anti-inflammatory action, regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism, blood pressure control, and endothelial protection. SCFAs may also have potential roles in mitigating comorbid conditions such as insomnia (44–46).

Conversely, elevated levels of microbiota-derived trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) and Helicobacter pylori infection have been linked to increased atherosclerotic burden and cardiovascular risk (47, 48). Although the exact mechanism of H. pylori-induced endothelial injury remains unclear, TMAO has been shown to promote platelet aggregation, foam cell formation, and atherosclerotic plaque instability, making it an independent risk factor for CMM (49, 50).The combination of dietary strategies that enhance SCFA production and reduce TMAO load with therapeutic drugs has the potential to positively impact clinical outcomes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pathophysiological mechanisms of CMM. IR, Insulin Resistance; TyG: Triglyceride-glucose index; FFAs, Free Fatty Acids; NO, Nitric Oxide; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species; SCFAs, Short-chain Fatty; TMAO, Acids microbiota-derived trimethylamine N-oxide.

Mechanism-oriented drug intervention programs

Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors

SGLT2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), such as empagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and canagliflozin, have demonstrated benefits beyond glycemic control, showing pleiotropic effects across multiple organs and systems (51, 52). By inhibiting renal proximal tubule reabsorption of sodium and glucose, these agents induce osmotic diuresis and natriuresis, thereby reducing blood pressure and cardiac preload (53). They also enhance glycemic control and promote weight loss via increased urinary glucose excretion (54).

On the level of energy metabolism, SGLT2i promote substrate shift towards fatty acid and ketone utilization, improving myocardial and renal energy efficiency (55). Additionally, they exhibit anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic properties, partly through attenuation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation via Ca2+ modulation, thereby directly protecting cardiac and renal tissues (56, 57).

Multiple large-scale clinical trials have shown that SGLT2i significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular death, heart failure hospitalization, and renal events in patients with T2DM complicated by atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or heart failure (58). Notably, these benefits extend to non-diabetic populations, such as patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), in whom substantial clinical improvements have also been observed (59).

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

GLP-1 receptor agonists, including liraglutide, semaglutide, and dulaglutide, exert multifaceted effects by activating GLP-1 receptors in various tissues beyond the pancreas (9, 60). Their mechanisms of action and clinical benefits include the following:

In glucose and weight control, GLP-1 RA lower blood glucose levels and induce significant, sustained weight loss by centrally suppressing appetite and delaying gastric emptying (61–63). In atherosclerosis prevention, these agents exert direct effects on vascular endothelial cells and immune cells, reducing inflammatory processes within atherosclerotic plaques, improving endothelial function, and lowering LDL-C and blood pressure levels (64, 65).

Cardiovascular outcome trials (CVOTs) have consistently demonstrated that GLP-1 RA reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), particularly nonfatal myocardial infarction and stroke (66, 67). However, their efficacy in reducing cardiovascular and renal outcomes among non-diabetic populations remains to be established. Currently, GLP-1 RA are especially recommended for patients with T2DM and established ASCVD or high ASCVD risk, as well as those requiring intensive weight management.

Nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists

Finerenone, a next-generation nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (ns-MRA), inherits the anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic properties of traditional MRAs and offers additional therapeutic benefits. Preclinical and clinical data demonstrate its capacity to reduce fibrosis, lower pulmonary artery pressure, improve diabetic retinopathy, enhance endothelial function, and attenuate oxidative stress, thereby providing comprehensive cardiorenal protection (68, 69).

Finerenone exerts targeted anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects by selectively blocking mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) overactivation in cardiac, vascular, and renal tissues. This results in marked reductions in biomarkers such as NT-proBNP and UACR, which are closely associated with heart and kidney injury (70, 71). Although mild hyperkalemia may occur during early treatment, it does not negate the overall cardiorenal benefits of the drug. Furthermore, finerenone improves endothelial function, reduces vascular oxidative stress, and restores NO bioavailability, reinforcing its organ-protective profile (72).

Two large-scale trials involving 13,026 patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and T2DM confirmed that finerenone, compared to placebo, significantly reduces the risk of CKD progression and cardiovascular events while slowing the decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (13, 15).

Other pleiotropic agents

Statins remain the cornerstone of ASCVD prevention and treatment. Beyond their potent lipid-lowering effects, they also exhibit anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, plaque-stabilizing, and vasodilatory properties (73). However, recent studies have indicated that prolonged or high-dose statin use may be associated with an elevated risk of muscle-related adverse effects, hyperglycemia, hemorrhagic stroke, liver disease, and cognitive decline (74, 75). A meta-analysis by Soleimani et al. indicated that moderate-dose statins combined with ezetimibe provide greater LDL-C reduction and fewer adverse events than high-dose statins alone (76), highlighting the need for dose optimization in clinical practice to mitigate adverse effects. Additionally, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and sacubitril/valsartan not only reduce blood pressure but also confer renoprotective, anti-inflammatory, and endothelial function-improving benefits (77, 78), making them vital components of cardiovascular therapy.

Optimizing clinical pharmacotherapy: summary and recommendations

Foundational treatment for patients with cardiometabolic multimorbidity

All patients should initiate and maintain lifestyle interventions, including heart-healthy dietary patterns, regular physical activity, smoking cessation, and alcohol moderation, as the foundation of any pharmacological treatment.

For patients with ASCVD, the initiation of statin therapy at an appropriate dose should be promptly initiated based on baseline LDL-C levels. In instances where LDL-C targets are not met or cases of statin intolerance arise, combination therapy involving ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor should be contemplated.

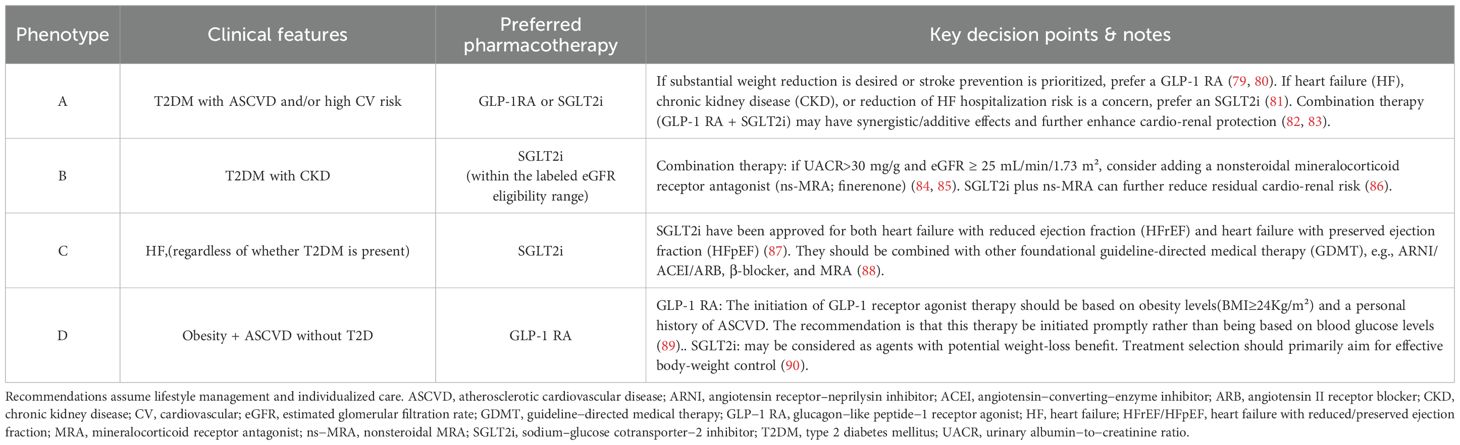

For patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) should include the “four pillars” of pharmacologic management: β-blockers, ACEIs/ARBs/ARNIs, MRAs, and SGLT2i (Table 2).

Prioritized drug selection based on comorbidity phenotypes

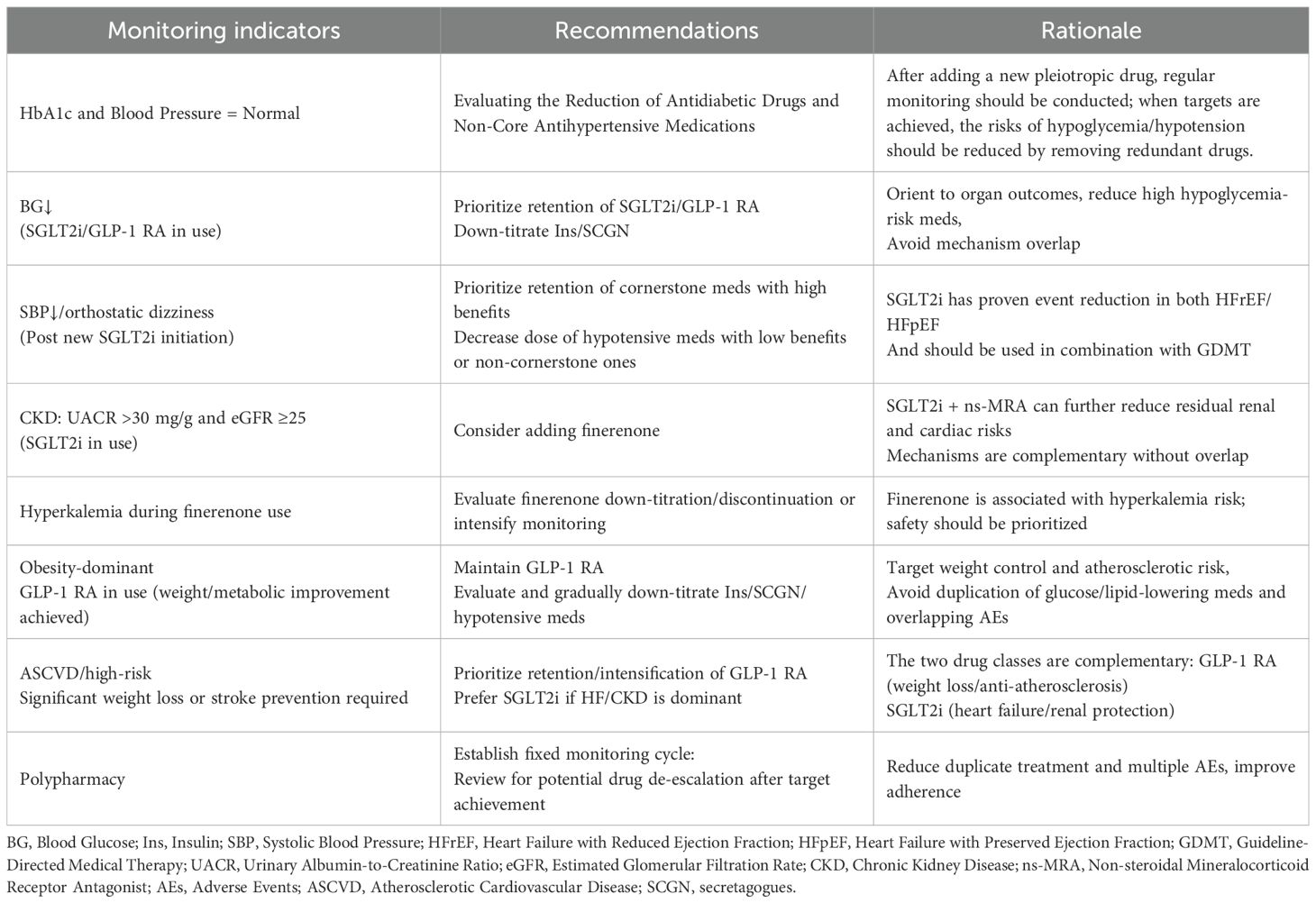

Avoiding redundant therapy and ensuring regular medication review

Following the initiation of newer therapies with established multi-organ benefits, such as SGLT2i and GLP-1RA, regular reassessment of the pre-existing treatment regimen is essential. When glycemic and blood pressure control is achieved, clinicians should consider de-escalation strategies, including dose reduction or discontinuation of other antihyperglycemic agents (e.g., insulin) and antihypertensives, to mitigate the risks of hypoglycemia and hypotension.

Establishing a structured medication review schedule is a critical step in optimizing pharmacotherapy. It allows for timely evaluation of drug necessity, minimizes polypharmacy, reduces patient burden, and helps achieve individualized therapeutic goals more safely and efficiently (Table 3).

Phenotype-based priority treatment across different ages and genders

The management of cardiac metabolic comorbidities must move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach toward precision-based, phenotype-driven treatment strategies that are tailored to specific patient characteristics. Firstly, for elderly patients deemed to be frail, the management plans must be meticulously devised, in view of the complexities arising from polypharmacy and multiple coexisting conditions. This is particularly evident in patients aged ≥75 years with ≥4 chronic diseases, where treatment regimens require a delicate balance between efficacy and safety. It is recommended that streamlined management pathways be established for these patients, centered on the following: 1) Safe medication use: It is imperative to closely monitor and enhance surveillance for the emergence of acute kidney injury, hypovolemia, and hyperkalemia when administering SGLT2 inhibitors in conjunction with NSAIDs or ACEI/ARBs (91). 2) The step-down therapy approach is employed here. It is imperative to establish explicit criteria for the reduction or discontinuation of insulin or sulfonylureas, with the objective of averting hypoglycemic incidents and mitigating the risk of falls and other deleterious outcomes associated with polypharmacy (92).

The existence of gender-based differences in treatment response represents a critical aspect of precision medicine that cannot be overlooked. A mounting body of evidence suggests the presence of gender heterogeneity in the efficacy and tolerability of pharmaceuticals. For instance, subgroup analyses from trials such as DAPA-HF suggest that female patients may experience a greater decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) following SGLT2 inhibitor use compared to males (93). Meanwhile, studies have documented a higher prevalence of gastrointestinal intolerance to GLP-1 receptor agonists in female patients compared to male patients (94). Consequently, when recommending medications based on phenotype, it is imperative to consider gender factors comprehensively. For instance, a more gradual dose titration strategy should be adopted when initiating treatment for female patients, accompanied by enhanced monitoring of renal function and electrolyte levels to optimize treatment adherence and long-term prognosis.

Equity in mechanism-guided care

In consideration of the national circumstances of differing countries, the “phenotype-first” treatment model that is proposed encounters considerable challenges in resource-constrained settings. In a multitude of low- and middle-income countries, the implementation of novel pharmaceuticals such as SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and finerenone may encounter significant challenges due to their substantial financial burden and restricted accessibility (95). This phenomenon, termed the “treatment gap,” has been identified as a contributing factor to global health inequities. In light of this challenge, clinicians and healthcare system decision-makers must not relinquish mechanism-driven treatment principles but rather employ a creative approach in their application to available therapeutic options. The core strategy involves repurposing affordable, widely accessible medications and combining them with enhanced lifestyle interventions. The aim is to mimic or partially replicate the multi-pathway protective effects of novel drugs.

Structured lifestyle interventions constitute the basis of all treatment strategies, a fact that is especially evident in settings with limited resources. Enhanced lifestyle modifications, encompassing a heart-healthy diet, regular physical activity, and smoking cessation, constitute a potent “multi-targeted therapy” capable of simultaneously improving insulin resistance, lowering blood pressure, reducing weight, regulating lipids, and alleviating inflammation (96).When medications are available, priority should be given to novel agents with established organ-protective evidence, such as SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and finerenone, to ensure precise targeting of distinct phenotypes. In settings where resources are limited, it is imperative to adhere strictly to maximum tolerated doses of ACEI and ARB in order to reduce proteinuria and slow the progression of renal disease (97, 98). In order to manage cardiovascular risk, it is imperative to combine these with evidence-based statins in order to rigorously control lipids (99).

In instances where finerenone is not available, traditional MRAs remain a vital option based on the same core mechanism. Notwithstanding the necessity for close monitoring of serum potassium and renal function, the addition of spironolactone constitutes a physiologically sound, pragmatic strategy for T2D patients with albuminuria and high cardiovascular risk, following a thorough risk-benefit assessment. It is imperative that the global medical community collaborate to ensure the continuous reduction of barriers to accessing novel therapies. The objective of this initiative is to integrate mechanism-driven advanced treatment concepts with universally accessible healthcare equity, thereby ensuring that patients with CMM—regardless of their geographical location—receive optimal pathophysiology-based care.

Conclusion

Mechanistic and clinical advances over the past five years have fundamentally transformed the therapeutic paradigm for CMM. Clinical strategies have evolved from a traditional “one-disease, one-drug” approach to an integrated and mechanism-guided model of care. This review underscores the importance of timely and prioritized use of pharmacologic agents with proven multi-organ protective effects—such as SGLT2i, GLP-1RA, and nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. These therapies not only target multiple risk factors concurrently but also improve long-term clinical outcomes. Importantly, such integrated approaches facilitate regimen simplification, reduce medication burden and adverse drug events, and emphasize the necessity of precision prescribing. For clinicians, this highlights the critical importance of coordinated and rational pharmacotherapy, ultimately delivering the greatest clinical benefit to patients living with CMM.

Author contributions

HD: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. LC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. TT: Writing – original draft, Data curation. RS: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. KY: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology. CW: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. ZL: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. QJ: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Investigation. JW: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. TH: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. HC: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. XS: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. YD: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by National Key Science and Technology major Project for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer, Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases, Respiratory Diseases, and Metabolic Diseases Number: 2023ZD0505702.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2025.1724965/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

CMM, Cardiometabolic multimorbidity; SGLT2i, Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; GLP-1RA, Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; IR, Insulin Resistance; TyG, Triglyceride-glucose index; FFAs, Free Fatty Acids; T2DM, Type 2 diabetes mellitus; NO, Nitric Oxide; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species; SCFAs, Short-chain Fatty Acids; CVOTs, Cardiovascular Outcome Trials; NT-proBNP, N-Terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide; UACR, Urine Albumin to Creatinine Ratio; eGFR, estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate; GDMT, Guideline-directed Medical Therapy.

References

1. Tai XY, Veldsman M, Lyall DM, Littlejohns TJ, Langa KM, Husain M, et al. Cardiometabolic multimorbidity, genetic risk, and dementia: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. (2022) 3:e428–36. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00117-9

2. Chong B, Jayabaskaran J, Jauhari SM, Chan SP, Goh R, Kueh MTW, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: projections from 2025 to 2050. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2025) 32:1001–15. doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwae281

3. Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Association of cardiometabolic multimorbidity with mortality. JAMA. (2015) 314:52–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7008

4. Alizargar J, Bai CH, Hsieh NC, and Wu SV. Use of the triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) in cardiovascular disease patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2020) 19:8. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0982-2

5. Liu C, Liang D, Xiao K, and Xie L. Association between the triglyceride-glucose index and all-cause and CVD mortality in the young population with diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2024) 23:171. doi: 10.1186/s12933-024-02269-0

6. Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, Chertow GM, Greene T, Hou FF, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:1436–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024816

7. The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group, Herrington WG, Staplin N, et al. Empagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. (2023) 388:117–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204233

8. Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Pocock SJ, Carson P, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. New Engl J Med. (2020) 383:1413–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022190

9. Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Bocchi E, Böhm M, et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. New Engl J Med. (2021) 385:1451–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107038

10. Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Claggett B, de Boer RA, DeMets D, Hernandez AF, et al. Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. (2022) 387:1089–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206286

11. Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Pitt B, Cannon CP, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, et al. Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. New Engl J Med. (2021) 384:129–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2030186

12. Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Steg G, Cannon CP, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, et al. Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and recent worsening heart failure. New Engl J Med. (2021) 384:117–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2030183

13. Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Pitt B, Ruilope LM, Rossing P, et al. Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes. New Engl J Med. (2020) 383:2219–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2025845

14. Pitt B, Filippatos G, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Bakris GL, Rossing P, et al. Cardiovascular events with finerenone in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. New Engl J Med. (2021) 385:2252–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110956

15. Agarwal R, Filippatos G, Pitt B, Anker SD, Rossing P, Joseph A, et al. Cardiovascular and kidney outcomes with finerenone in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: the FIDELITY pooled analysis. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43:474–84. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab777

16. Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, Deanfield J, Emerson SS, Esbjerg S, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in obesity without diabetes. New Engl J Med. (2023) 389:2221–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2307563

17. Hill MA, Yang Y, Zhang L, Sun Z, Jia G, Parrish AR, et al. Insulin resistance, cardiovascular stiffening and cardiovascular disease. Metabolism. (2021) 119:154766. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154766

18. Li M, Chi X, Wang Y, Setrerrahmane S, Xie W, and Xu H. Trends in insulin resistance: insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther. (2022) 7:216. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01073-0

19. Sun Y, Ji H, Sun W, An X, and Lian F. Triglyceride glucose (TyG) index: A promising biomarker for diagnosis and treatment of different diseases. Eur J Intern Med. (2025) 131:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2024.08.026

20. Kojta I, Chacińska M, and Błachnio-Zabielska A. Obesity, bioactive lipids, and adipose tissue inflammation in insulin resistance. Nutrients. (2020) 12:1305. doi: 10.3390/nu12051305

21. Al-Mansoori L, Al-Jaber H, Prince MS, and Elrayess MA. Role of inflammatory cytokines, growth factors and adipokines in adipogenesis and insulin resistance. Inflammation. (2022) 45:31–44. doi: 10.1007/s10753-021-01559-z

22. He S, Ryu J, Liu J, Luo H, Lv Y, Langlais PR, et al. LRG1 is an adipokine that mediates obesity-induced hepatosteatosis and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. (2021) 131:e148545. doi: 10.1172/JCI148545

23. Li B, Hou C, Li L, Li M, and Gao S. The associations of adipokines with hypertension in youth with cardiometabolic risk and the mediation role of insulin resistance: The BCAMS study. Hypertension Res. (2023) 46:1673–83. doi: 10.1038/s41440-023-01243-9

24. Muniyappa R, Chen H, Montagnani M, Sherman A, and Quon MJ. Endothelial dysfunction due to selective insulin resistance in vascular endothelium: insights from mechanistic modeling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2020) 319:E629–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00247.2020

25. Murakami T, Inagaki N, and Kondoh H. Cellular senescence in diabetes mellitus: distinct senotherapeutic strategies for adipose tissue and pancreatic β Cells. Front Endocrinol. (2022) 13:869414. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.869414

26. Biondi G, Marrano N, Dipaola L, Borrelli A, Rella M, D'Oria R, et al. The p66Shc protein mediates insulin resistance and secretory dysfunction in pancreatic β-cells under lipotoxic conditions. Diabetes. (2022) 71:1763–71. doi: 10.2337/db21-1066

27. Haye A, Ansari MA, Rahman SO, Shamsi Y, Ahmed D, and Sharma M. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase on cardio-metabolic abnormalities in the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy: A molecular landscape. Eur J Pharmacol. (2020) 888:173376. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173376

28. Cliff CL, Squires PE, and Hills CE. Tonabersat suppresses priming/activation of the NOD-like receptor protein-3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and decreases renal tubular epithelial-to-macrophage crosstalk in a model of diabetic kidney disease. Cell Commun Signal. (2024) 22:351. doi: 10.1186/s12964-024-01728-1

29. Fusco R, Siracusa R, Genovese T, Cuzzocrea S, and Di Paola R. Focus on the role of NLRP3 inflammasome in diseases. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:4223. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124223

30. Herwig M, Sieme M, Kovács A, Khan M, Mügge A, Schmidt WE, et al. Diabetes mellitus aggravates myocardial inflammation and oxidative stress in aortic stenosis: a mechanistic link to HFpEF features. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2025) 24:203. doi: 10.1186/s12933-025-02748-y

31. Kiran S, Kumar V, Kumar S, Price RL, and Singh UP. Adipocyte, immune cells, and miRNA crosstalk: A novel regulator of metabolic dysfunction and obesity. Cells. (2021) 10:1004. doi: 10.3390/cells10051004

32. Kawai T, Autieri MV, and Scalia R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. (2021) 320:C375–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00379.2020

33. Wu X, Ying H, Vincent EE, Borges MC, Gaunt TR, Ning G, et al. Transcriptome-wide Mendelian randomization during CD4 T cell activation reveals immune-related drug targets for cardiometabolic diseases. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:9302. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-53621-7

34. Shao Y, Saredy J, Yang WY, Sun Y, Lu Y, Saaoud F, et al. Vascular endothelial cells and innate immunity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2020) 40:e138–52. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314330

35. Akhigbe R and Ajayi A. The impact of reactive oxygen species in the development of cardiometabolic disorders: a review. Lipids Health Dis. (2021) 20:23. doi: 10.1186/s12944-021-01435-7

36. Xu S, Lu F, Gao J, and Yuan Y. Inflammation-mediated metabolic regulation in adipose tissue. Obes Rev. (2024) 25:e13724. doi: 10.1111/obr.13724

37. de Deus IJ, Martins-Silva AF, Fagundes MMA, Paula-Gomes S, Silva FGDE, da Cruz LL, et al. Role of NLRP3 inflammasome and oxidative stress in hepatic insulin resistance and the ameliorative effect of phytochemical intervention. Front Pharmacol. (2023) 14:1188829. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1188829

38. Mroueh A, Algara-Suarez P, Fakih W, Gong DS, Matsushita K, Park SH, et al. SGLT2 expression in human vasculature and heart correlates with low-grade inflammation and causes eNOS-NO/ROS imbalance. Cardiovasc Res. (2025) 121:643–57. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvae257

39. Zhou Q, Zhang Y, Shi W, Lu L, Wei J, Wang J, et al. Angiotensin II induces vascular endothelial dysfunction by promoting lipid peroxidation-mediated ferroptosis via CD36. Biomolecules. (2024) 14:1456. doi: 10.3390/biom14111456

40. Hernandez-Navarro I, Botana L, Diez-Mata J, Tesoro L, Jimenez-Guirado B, Gonzalez-Cucharero C, et al. Replicative endothelial cell senescence may lead to endothelial dysfunction by increasing the BH2/BH4 ratio induced by oxidative stress, reducing BH4 availability, and decreasing the expression of eNOS. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:9890. doi: 10.3390/ijms25189890

41. Sarkar S, Prasanna VS, Das P, Suzuki H, Fujihara K, Kodama S, et al. The onset and the development of cardiometabolic aging: an insight into the underlying mechanisms. Front Pharmacol. (2024)15:1447890. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1447890

42. Epelde F. The role of the gut microbiota in heart failure: pathophysiological insights and future perspectives. Med (Kaunas). (2025) 61:720. doi: 10.3390/medicina61040720

43. Long D, Mao C, An H, Zhu Y, and Xu Y. Association between dietary index for gut microbiota and cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome: a population-based study. Front Nutr. (2025) 12:1594481. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1594481

44. Mukhopadhya I and Louis P. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and their role in human health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2025) 23:635–51. doi: 10.1038/s41579-025-01183-w

45. Aldubayan MA, Mao X, Laursen MF, Pigsborg K, Christensen LH, Roager HM, et al. Supplementation with inulin-type fructans affects gut microbiota and attenuates some of the cardiometabolic benefits of a plant-based diet in individuals with overweight or obesity. Front Nutr. (2023) 10:1108088. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1108088

46. Ostrowska J, Samborowska E, Jaworski M, Toczyłowska K, and Szostak-Węgierek D. The potential role of SCFAs in modulating cardiometabolic risk by interacting with adiposity parameters and diet. Nutrients. (2024) 16:266. doi: 10.3390/nu16020266

47. Jaworska K, Kopacz W, Koper M, and Ufnal M. Microbiome-derived trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) as a multifaceted biomarker in cardiovascular disease: challenges and opportunities. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:12511. doi: 10.3390/ijms252312511

48. Francisco AJ. Helicobacter pylori infection induces intestinal dysbiosis that could be related to the onset of atherosclerosis. BioMed Res Int. (2022) 2022:9943158. doi: 10.1155/2022/9943158

49. Thomas MS and Fernandez ML. Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), diet and cardiovascular disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep. (2021) 23:12. doi: 10.1007/s11883-021-00910-x

50. Spence JD. Cardiovascular effects of TMAO and other toxic metabolites of the intestinal microbiome. J Intern Med. (2023) 293:2–3. doi: 10.1111/joim.13571

51. Seidu S, Alabraba V, Davies S, Newland-Jones P, Fernando K, Bain SC, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors - the new standard of care for cardiovascular, renal and metabolic protection in type 2 diabetes: A narrative review. Diabetes tTher: Res Treat Educ Diabetes Related Disord. (2024) 15:1099–124. doi: 10.1007/s13300-024-01550-5

52. Siddiqi TJ, Cherney D, Siddiqui HF, Jafar TH, Januzzi JL, Khan MS, et al. Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors on kidney outcomes across baseline cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic conditions: A systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Soc Nephrol: JASN. (2025) 36:242–55. doi: 10.1681/ASN.0000000000000491

53. Rossing P, Filippatos G, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Pitt B, Ruilope LM, et al. Finerenone in predominantly advanced CKD and type 2 diabetes with or without sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor therapy. Kidney Int Rep. (2021) 7:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.10.008

54. Scheen AJ. Use of SGLT2 inhibitors after bariatric/metabolic surgery: Risk/benefit balance. Diabetes Metab. (2023) 49:101453. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2023.101453

55. Veelen A, Andriessen C, Op den Kamp Y, Erazo-Tapia E, de Ligt M, Mevenkamp J, et al. Effects of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin on substrate metabolism in prediabetic insulin resistant individuals: A randomized, double-blind crossover trial. Metabol: Clin Exp. (2023) 140:155396. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2022.155396

56. Lopaschuk GD and Verma S. Mechanisms of cardiovascular benefits of sodium glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors: A state-of-the-art review. JACC Basic to Trans Sci. (2020) 5:632–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.02.004

57. Byrne NJ, Matsumura N, Maayah ZH, Ferdaoussi M, Takahara S, Darwesh AM, et al. Empagliflozin blunts worsening cardiac dysfunction associated with reduced NLRP3 (Nucleotide-binding domain-like receptor protein 3) inflammasome activation in heart failure. Circulation Heart Failure. (2020) 13:e006277. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006277

58. Zannad F, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of the EMPEROR-Reduced and DAPA-HF trials. Lancet (London England). (2020) 396:819–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31824-9

59. Zafeiropoulos S, Farmakis IT, Milioglou I, Doundoulakis I, Gorodeski EZ, Konstantinides SV, et al. Pharmacological treatments in heart failure with mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction: systematic review and network meta-analysis. JACC Heart Failure. (2024) 12:616–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2023.07.014

60. Zheng Z, Zong Y, Ma Y, Tian Y, Pang Y, Zhang C, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther. (2024) 9:234. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01931-z

61. Drucker DJ. GLP-1 physiology informs the pharmacotherapy of obesity. Mol Metab. (2022) 57:101351. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2021.101351

62. Jalleh RJ, Rayner CK, Hausken T, Jones KL, Camilleri M, and Horowitz M. Gastrointestinal effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists: mechanisms, management, and future directions. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2024) 9:957–64. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(24)00188-2

63. Clark L. GLP-1 receptor agonists: A review of glycemic benefits and beyond. JAAPA. (2024) 37:1–4. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0001007388.97793.41

64. Yang L, Chen L, Li D, Xu H, Chen J, Min X, et al. Effect of GLP-1/GLP-1R on the polarization of macrophages in the occurrence and development of atherosclerosis. Mediators Inflammation. (2021) 2021:5568159. doi: 10.1155/2021/5568159

65. Gomes DA, Presume J, de Araújo Gonçalves P, Almeida MS, Mendes M, and Ferreira J. Association between the magnitude of glycemic control and body weight loss with GLP-1 receptor agonists and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized diabetes cardiovascular outcomes trials. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. (2025) 39:337–45. doi: 10.1007/s10557-024-07547-3

66. Helmstädter J, Keppeler K, Küster L, Münzel T, Daiber A, and Steven S. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and their cardiovascular benefits-The role of the GLP-1 receptor. Br J Pharmacol. (2022) 179:659–76. doi: 10.1111/bph.15462

67. McGuire DK, Busui RP, Deanfield J, Inzucchi SE, Mann JFE, Marx N, et al. Effects of oral semaglutide on cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and/or chronic kidney disease: Design and baseline characteristics of SOUL, a randomized trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. (2023) 25:1932–41. doi: 10.1111/dom.15058

68. Zhai S, Ma B, Chen W, and Zhao Q. A comprehensive review of finerenone-a third-generation non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2024) 11:1476029. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1476029

69. Jerome JR, Deliyanti D, Suphapimol V, Kolkhof P, and Wilkinson-Berka JL. Finerenone, a non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, reduces vascular injury and increases regulatory T-cells: studies in rodents with diabetic and neovascular retinopathy. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:2334. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032334

70. Yao L, Liang X, Liu Y, Li B, Hong M, Wang X, et al. Non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction via PI3K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathway in diabetic tubulopathy. Redox Biol. (2023) 68:102946. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2023.102946

71. Agarwal R, Joseph A, Anker SD, Filippatos G, Rossing P, Ruilope LM, et al. Hyperkalemia risk with finerenone: results from the FIDELIO-DKD trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2022) 33:225–37. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2021070942

72. Rossing P, Anker SD, Filippatos G, Pitt B, Ruilope LM, Birkenfeld AL, et al. FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD investigators. Finerenone in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes by sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor treatment: the FIDELITY analysis. Diabetes Care. (2022) 45:2991–8. doi: 10.2337/dc22-0294

73. German CA and Liao JK. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of statin pleiotropic effects. Arch Toxicol. (2023) 97:1529–45. doi: 10.1007/s00204-023-03492-6

74. Sung EM and Saver JL. Statin overuse in cerebral ischemia without indications: systematic review and annual US burden of adverse events. Stroke. (2024) 55:2022–33. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.123.044071

75. Vell MS, Loomba R, Krishnan A, Wangensteen KJ, Trebicka J, Creasy KT, et al. Association of statin use with risk of liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver-related mortality. JAMA Netw Open. (2023) 6:e2320222. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.20222

76. Soleimani H, Mousavi A, Shojaei S, Tavakoli K, Salabat D, Farahani Rad F, et al. Safety and effectiveness of high-intensity statins versus low/moderate-intensity statins plus ezetimibe in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease for reaching LDL-C goals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol. (2024) 47:e24334. doi: 10.1002/clc.24334

77. Ma Z, Fu Z, Li N, Huang S, and Chi L. Comparative effects of sacubitril/valsartan and ACEI/ARB on endothelial function and arterial stiffness in patients with heart failure: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2024) 14:e088744. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2024-088744

78. Li J, Liu Q, Lian X, Yang S, Lian R, Li W, et al. Kidney outcomes following angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor vs angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker therapy for thrombotic microangiopathy. JAMA Netw Open. (2024) 7:e2432862. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.32862

79. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, Davies M, Van Gaal LF, Lingvay I, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:989–1002. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

80. Giugliano D, Scappaticcio L, Longo M, Caruso P, Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and cardiorenal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: an updated meta-analysis of eight CVOTs. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2021) 20:189. doi: 10.1186/s12933-021-01366-8

81. Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, et al. Effect of empagliflozin on the clinical stability of patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction: the EMPEROR-reduced trial. Circulation. (2021) 143:326–36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.051783

82. Simms-Williams N, Treves N, Yin H, Lu S, Yu O, Pradhan R, et al. Effect of combination treatment with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors on incidence of cardiovascular and serious renal events: population based cohort study. BMJ. (2024) 385:e078242. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-078242

83. Neuen BL, Fletcher RA, Heath L, Perkovic A, Vaduganathan M, Badve SV, et al. Cardiovascular, kidney, and safety outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists alone and in combination with SGLT2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. (2024) 150:1781–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.124.071689

84. de Boer IH, Khunti K, Sadusky T, Tuttle KR, Neumiller JJ, Rhee CM, et al. Diabetes management in chronic kidney disease: A consensus report by the american diabetes association (ADA) and kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO). Diabetes Care. (2022) 45:3075–90. doi: 10.2337/dci22-0027

85. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. (2024) 105:S117–314. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.018

86. Mårup FH, Thomsen MB, and Birn H. Additive effects of dapagliflozin and finerenone on albuminuria in non-diabetic CKD: an open-label randomized clinical trial. Clin Kidney J. (2023) 17:sfad249. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfad249

87. Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2022) 145:e895–e1032. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063

88. Authors/Task Force Members, McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. (2024) 26:5–17. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.3024

89. Huang YN, Liao WL, Huang JY, Lin YJ, Yang SF, Huang CC, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in individuals with obesity and without type 2 diabetes: A global retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Obes Metab. (2024) 26:5222–32. doi: 10.1111/dom.15869

90. Tsapas A, Karagiannis T, Kakotrichi P, Avgerinos I, Mantsiou C, Tousinas G, et al. Comparative efficacy of glucose-lowering medications on body weight and blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. (2021) 23:2116–24. doi: 10.1111/dom.14451

91. Qiu M, Ding LL, Zhang M, and Zhou HR. Safety of four SGLT2 inhibitors in three chronic diseases: A meta-analysis of large randomized trials of SGLT2 inhibitors. Diabetes Vasc Dis Res. (2021) 18:14791641211011016. doi: 10.1177/14791641211011016

92. Umegaki H. Management of older adults with diabetes mellitus: Perspective from geriatric medicine. J Diabetes Investig. (2024) 15:1347–54. doi: 10.1111/jdi.14283

93. Butt JH, McMurray JJV, Claggett BL, Jhund PS, Neuen BL, McCausland FR, et al. Therapeutic effects of heart failure medical therapies on standardized kidney outcomes: comprehensive individual participant-level analysis of 6 randomized clinical trials. Circulation. (2024) 150:1858–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.124.071110

94. Masulli M, Tack J, Esposito G, and Sarnelli G. GLP-1 and GIP agonists in diabetes and obesity and the rise of dyspepsia. Intern Emerg Med. doi: 10.1007/s11739-025-04117-9

95. Global Health & Population Project on Access to Care for Cardiometabolic Diseases (HPACC). Expanding access to newer medicines for people with type 2 diabetes in low-income and middle-income countries: a cost-effectiveness and price target analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2021) 9:825–36. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00240-0

96. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 5. Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. (2022) 45:S60–82. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S005

97. Safaie N, Idari G, Ghasemi D, Hajiabbasi M, Alivirdiloo V, Masoumi S, et al. AMPK activation; a potential strategy to mitigate TKI-induced cardiovascular toxicity. Arch Physiol Biochem. (2025) 131:329–41. doi: 10.1080/13813455.2024.2426494

98. Safaie N, Masoumi S, Alizadeh S, Mirzajanzadeh P, Nejabati HR, Hajiabbasi M, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors and AMPK: The road to cellular housekeeping? Cell Biochem Funct. (2024) 42:e3922. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3922

Keywords: type 2 diabetes, cardiometabolic multimorbidity, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, mechanisms, treatment optimization

Citation: Dong H, Chang L, Tian T, Shi R, Yu K, Wang C, Liu Z, Jin Q, Wang J, He T, Chen H, Shao X and Deng Y (2025) Mechanism-guided pharmacotherapy for cardiometabolic multimorbidity: from pathophysiology to phenotype-prioritized treatment. Front. Endocrinol. 16:1724965. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2025.1724965

Received: 14 October 2025; Accepted: 13 November 2025; Revised: 09 November 2025;

Published: 01 December 2025.

Edited by:

Wanlu Ma, Endocrinology Department of China Japan Friendship Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Bangjiang Fang, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, ChinaZiba Majidi, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Copyright © 2025 Dong, Chang, Tian, Shi, Yu, Wang, Liu, Jin, Wang, He, Chen, Shao and Deng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yue Deng, ZHl1ZTcxMzhAc2luYS5jb20=

Hezeng Dong

Hezeng Dong Liping Chang2

Liping Chang2 Tenghui Tian

Tenghui Tian Cheng Wang

Cheng Wang Jing Wang

Jing Wang