Abstract

This study focuses on the Neanderthal subsistence strategies at Cueva del Ángel, a site in southern Spain with a stratigraphic sequence from the Late Middle Pleistocene. Using zooarchaeological and taphonomic methodologies, we conducted a diachronic analysis of over 3,500 faunal remains to explore the exploitation patterns of medium- and large-sized ungulates. Results reveal a systematic and intensive exploitation of large mammals, particularly horses, red deer, and large bovids, with an emphasis on high-energy resources, such as meat and marrow. The anatomical representation and fragmentation patterns suggest selective hunting strategies and an intensive use of animal resources. Complementary resources, such as small game, were also exploited, potentially reflecting adaptive responses to increase predictability and minimize risks. The results align with other Eurasian sites from this period, emphasizing the persistence of large-game hunting as a core subsistence strategy, supplemented by diversified resources to mitigate risk. These findings underscore a consistent and flexible approach to resource management over time, highlighting the adaptability of Neanderthal subsistence strategies in Mediterranean ecosystems.

1 Introduction

In Western Eurasia, archaeological sites with substantial stratigraphic depth during the Middle Pleistocene are scarce, especially in the first half. However, the number of such sites increases in the second half around MIS 12-11, providing wider perspectives and revealing a distinct change in subsistence strategies (Chazan, 2009; Villa and Lenoir, 2009). These changes are likely related to climate and paleoenvironment (Blain et al., 2021), the emergence of fire technology (Rolland, 2000; Gowlett, 2006; Karkanas et al., 2007; Roebroeks and Villa, 2011; Shimelmitz et al., 2014; Rosell and Blasco, 2019), the appearance of post-Acheulean technocomplexes (Moncel et al., 2015, 2021; Kuhn et al., 2021), a transition from the exploitation of megafauna to large-medium-sized animals (Gaudzinski-Windheuser and Niven, 2009; Gaudzinski-Windheuser and Kindler, 2012a,b; Lee-Thorp et al., 2015; White et al., 2016; Kuhn and Stiner, 2019) and to broad-spectrum diets (Stiner, 2004b; Blasco, 2008; Blasco and Peris, 2009; Nabais and Zilhão, 2019; Nabais et al., 2023a).

Our current understanding of Neanderthal hunting and exploitation strategies is that they were based on the exploitation of large ungulates through selective and/or opportunistic behavior, depending on the context and species (Rendu, 2022). In the Mediterranean region, this was complemented by a more diverse diet that included rabbits, tortoises, birds, and shellfish for various purposes—dietary, aesthetic, and symbolic—that reflect flexible behavior in different environments and regions (Zilhão et al., 2020; Blasco et al., 2022; Moigne et al., 2023). One of the key aspects that has been proposed is the 'mono-specific' exploitation of large-medium-sized adult animals, particularly during the temperate isotopic stages MIS 9 and 7 (Gaudzinski, 2006; Gaudzinski-Windheuser and Kindler, 2012a), supported by the high energy returns they provided, which in turn required a high degree of flexibility in the tactics employed (Gaudzinski-Windheuser and Niven, 2009). In addition to this selective behavior, zooarchaeological and taphonomic analyses point toward intensive and systematic exploitation strategies (Yravedra-Sainz de los Terreros et al., 2016; Vettese et al., 2017; Marín et al., 2020; Linares-Matás and Yravedra, 2024). In this regard, significant advancements have been made in recent decades regarding the understanding of exploitation strategies for Faunal resources during the Middle Paleolithic. Some studies illustrate the massive communal hunting of bison (Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2016), the exploitation of large bovids (Jaubert et al., 1990; van Kolfschoten et al., 2015, 2018; Rivière et al., 2023) and horses (Diedrich, 2010; Hutson et al., 2020; Pope et al., 2020; Uzunidis, 2020), as well as the predominance of deer or reindeer (Daujeard et al., 2019; Valensi et al., 2022; Rendu et al., 2023; Ruebens et al., 2023; Silvestrini et al., 2024) and the exploitation of medium-sized ungulates (Yravedra and Cobo-Sánchez, 2015). The abundance of these taxa in their various combinations, both in open-air sites and caves, underscores their significance in diet and derived products, while also acknowledging the complementary and diverse introduction of small animals (Hardy and Moncel, 2011; Blasco et al., 2016; Negro et al., 2016; Lebreton et al., 2017; Morin et al., 2019; Nabais and Zilhão, 2019; Crater Gershtein et al., 2022; Nabais et al., 2023b,a). However, diachronic analyses of complete sequences (Stiner et al., 2011; Niven, 2013; García-Medrano et al., 2017; Starkovich, 2017; Roditi and Starkovich, 2022; Berlioz et al., 2023) which would allow us to better understand the evolution of these strategies, remain scarce.

The Cueva del Ángel site in southern Spain features a robust and rich stratigraphic sequence from the Late Middle Pleistocene, offering opportunities for diachronic analyses of the subsistence strategies and lifestyles of its inhabitants. Previous studies highlight the site's long and intensive occupation as a habitat (Botella Ortega et al., 2006; Barroso Ruíz et al., 2011), evidence of fire use (Monge et al., 2016, 2020), the presence of bone retouchers (Moigne et al., 2016) and the extensive and sustained exploitation of animal resources (Solano García, 2024). The emergence of broad-spectrum diets during the Middle Pleistocene somewhat overshadowed the dominance of large mammals as the primary sources of food and resource exploitation. We now know that hunting strategies were well established (Gaudzinski-Windheuser et al., 2018) and that a significant portion of the diet was based on meat resources (Jaouen et al., 2019; Wißing et al., 2019), though the supplementary importance of other sources should not be overlooked (Hardy et al., 2022). Cueva del Ángel is no exception to the trends and innovations that began in MIS 11, which enrich and complicate our understanding of human behavior. In this context, it is necessary to explore the role that ungulates played over time and to search for possible long-term patterns that could help us infer continuities or discontinuities in subsistence strategies. This study aims to explore these patterns through the zooarchaeological analysis of ungulate species, their anatomical representation, and the degree of exploitation they underwent, within a broad temporal framework of analysis.

2 The site of Cueva del Ángel

The Cueva del Ángel is located at 605 m above sea level on the southern slope of a paleogeographical highland (Sierra de Aras; Figure 1B), flanked by two small fluvial valleys to the north and south, which flow into the Genil River. This range forms part of the western foothills of the Subbética mountain range in the province of Córdoba, 5 km south of the town of Lucena (Figure 1A). The karst complex, developed along a fault in Lower and Middle Jurassic limestones and dolomites, consists of three well-defined areas: (1) an open-air exterior platform where Middle Pleistocene deposits are found, which connects to (2) the inner entrance of the cave, leading to (3) a large, lower sinkhole. Currently, the Paleolithic site is located in the open-air section (area 1) due to the collapse of the cave's walls and roof at an unknown point in the past (Figure 1C). The site covers an area of ~100 m2, with at least 5 m of sedimentary fill in the excavated area (Barroso Ruíz et al., 2011).

Figure 1

(A) Location map of the site. (B) Aerial view of the Sierra de Aras from the west, showing the location of the site. (C) Aerial view of the site. (D) Planimetry of the site area with indication of the selected grids and the corresponding stratigraphic profile (Photographs by D. Botella).

The site underwent two initial excavation campaigns in 1995 and 1996 to assess its potential, followed by numerous additional campaigns within broader multidisciplinary research projects between 2002 and 2018. During the early archaeological cleaning efforts, a trench and a 2-m diameter mining shaft (Figure 1D) were discovered, likely dating to the late 18th century (Botella Ortega et al., 2006). The existence of the shaft allowed for the rapid recovery of a stratigraphic sequence from the site's archaeological fill. The initial goal was to remove large limestone and breccia blocks from the shaft while simultaneously excavating its southern profile (trench K) to obtain the most complete stratigraphy possible. In subsequent campaigns, the possible base of the fill was reached, and the excavation area was expanded to adjacent grids (J7 and trench 8; Figure 2A).

Figure 2

(A) Sketch of the section of the site showing the excavated archaeological fills. (B) Stratigraphic profile J/K (Adapted drawing by T. Saos and S. Khatib). (C) Detail image of the stratigraphic profile during excavation.

2.1 Stratigraphy and geochronology

Between the mining trench and the excavation of the shaft (cross-section J/K), 17 stratigraphic units (I–XVII) have been documented with a thickness of more than 4 m, varying in thickness, color, and texture (Figure 2B). The average thickness is 18 cm (σ = 9.3) and ranges between 2 and 50 cm, with the lower levels having the greatest thickness. They exhibit frequent erosive contacts and a sub-horizontal or northeastward dipping arrangement (levels VII–XV), with a bulging morphology that suggests post-depositional collapse processes. The colors (Figure 2C) range from various shades of brown, gray, pink, and reddish hues, with a dominant texture of silts and sands and a notable granular structure. The consistency is highly heterogeneous, varying from soft to hard depending on the extent of secondary calcite precipitation affecting each level. Porosity is generally absent or minimal (when present, it is always vacuolar in type), and the contacts between the layers are mostly sharp (Barroso Ruíz et al., 2011). So far, no hiatus has been detected in the stratigraphy.

Based on sedimentological, geomorphological, and geochemical analyses (Barroso Ruíz et al., 2011), it has been determined that this area (profile J/K) of the site was heavily exposed to anthropogenic fire activity. The stratigraphic units have been grouped into three major structural complexes (Monge et al., 2014): I (I–VII), II (VIII–XII), and III (XIII–XVII), with evidence suggesting a possible increase in thermo-alteration intensity from complex III to I, as indicated by the increase in organic carbon from complex III to I (Barroso Ruíz et al., 2011). In contrast, moving southward from this area, in trench 8, evidence of fire activity appears to be significantly lower (Monge et al., 2020). These data support the hypothesis of the existence of a recurrently used fireplace at the same location for thousands of years (Barroso Ruíz et al., 2011; Solano García, 2024). The presence of lithic industry remains and burned bone in all levels (Barroso Ruíz et al., 2011), along with low carnivore activity (Solano García, 2024) and the absence of guano (Monge et al., 2016), indicates a recurrent use of the site by human groups.

The chronology of the site was initially estimated to be over 130,000 years based on 230Th/234U dating of a sample from the upper part of the archaeological fill (Botella Ortega et al., 2006). The analysis of lithic industry and faunal spectrum suggested a broad chronological range from MIS 11 to MIS 5 (Barroso Ruíz et al., 2011; Moigne et al., 2016). Shortly afterward, a new series of ESR/U-series dates were published (Falguères et al., 2019) which, despite some limitations inherent to the method, identified ages ranging from MIS 9 to MIS 7, suggesting continuous human occupation between 320–180 ka. Recently, the discovery of a human tooth was reported (Bermúdez et al., 2023) which was dated using amino acid racemization and yielded a date of 104,300 years. However, the tooth came from a loose block from surface cleaning, possibly originating from previously eroded upper layers. Nevertheless, this date allows us to estimate an upper limit for the original fill, providing a timeframe from MIS-9/10 to MIS-5d, though the chronology of the lower part of the stratigraphic sequence remains uncertain (Figure 2B).

3 Materials and methods

Tackling large stratigraphic sequences in cave settings presents a challenge, primarily due to the presence of palimpsests (Bailey, 2007; Bailey and Galanidou, 2009) and the sheer volume of information. However, the goal of this study is not to dissect the palimpsests for high-resolution detail, but rather to obtain a diachronic overview of the long-term exploitation of ungulates. Despite this, the volume of data from the zooarchaeological and taphonomic analyses is substantial due to the number of stratigraphic units and species involved. Therefore, an exhaustive synthesis has been carried out by level and taxon to characterize and group the main ungulate species based on their skeletal recurrence and carcass treatment. This approach allows for the exploration of potential patterns of selection, standardization, or systematization in the exploitation processes.

3.1 Sample and materials background

In this study, remains from grids J7, K6, K7, and K8, which make up the J/K stratigraphic profile (Figure 1D), were used. We analyzed 3,700 remains, of which 2,000 are indeterminate fragments smaller than 2 cm that cannot even be classified as long bone or non-long bone (Pickering et al., 2003). These small fragments fall outside the scope of the zooarchaeological analysis of this study but were used to assess the overall fragmentation of the assemblage (Solano García, 2024). Stratigraphic units IV–XVII were selected from the entire sequence, while levels I to III were not considered due to the low number of remains, as these levels could not have been systematically excavated in this area. The analysis focuses on the exploitation of ungulates throughout the stratigraphic sequence. The presence of carnivores is attested by a low proportion of remains from Ursus arctos, Lynx pardinus, Canis lupus, and Felis silvestris across the entire sequence (Barroso Ruíz et al., 2011; Solano García, 2024) (Supplementary Table S1), which will be referred to as a general carnivore group (Table 1). Small fauna, such as birds, lagomorphs, tortoises, amphibians, rodents, etc. (Barroso Ruíz et al., 2011), were also excluded from the analysis, as they fall outside the objectives of this study (see Solano García, 2024 for more details). The sample used consists of 3,514 remains, including 1,394 identified herbivore remains (NISP), 145 carnivore remains, 1,569 remains classified by size category, and 406 indeterminate remains.

Table 1

| Level | Taxa | NISP (Und.) | %NISP | NISP LB | MNE | %MNE | MNE LB | MAU | %ΣMAU | %SI | MNI (I/J/A/S) | C/H*100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | 27 (15) | 13 (5) | 26 | 11 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.50 | 7 | 4.76 | |||

| BB | 5 | 18.52 | 3 | 5 | 19.23 | 3 | 0.04 | 19.98 | 4.24 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Cervus | 8 | 29.63 | 2 | 8 | 30.77 | 2 | 0.07 | 31.96 | 3.39 | 1/0/1/0 | ||

| Dama | 2 | 7.41 | 2 | 7.69 | 0.02 | 7.99 | 1.69 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Sus | 2 | 7.41 | 2 | 7.69 | 0.01 | 3.83 | 0.81 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Equus | 9 | 33.33 | 8 | 8 | 30.77 | 6 | 0.07 | 32.89 | 6.98 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Stephanorhinus | 1 | 3.70 | 1 | 3.85 | 0.01 | 3.34 | 0.71 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Large herbivore | 5 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 10 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 2 | |||||||||||

| V | 4 (166) | 3 (63) | 4 | 3 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 4 | 3.49 | |||

| BB | 1 | 25.00 | 1 | 25.00 | 0.01 | 25.81 | 0.85 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Cervus | 1 | 25.00 | 1 | 1 | 25.00 | 1 | 0.01 | 25.81 | 0.85 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Sus | 1 | 25.00 | 1 | 1 | 25.00 | 1 | 0.01 | 24.76 | 0.81 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Equus | 1 | 25.00 | 1 | 1 | 25.00 | 1 | 0.01 | 23.61 | 0.78 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Large herbivore | 20 | 12 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 62 | 40 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 84 | 11 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 3 | |||||||||||

| VI | 22 (16) | 11 (14) | 21 | 11 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 8 | 17.14 | |||

| BB | 8 | 36.36 | 3 | 7 | 33.33 | 3 | 0.06 | 34.95 | 2.97 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Cervus | 2 | 9.09 | 2 | 2 | 9.52 | 2 | 0.02 | 9.99 | 0.85 | 1/0/1/0 | ||

| Dama | 1 | 4.55 | 1 | 1 | 4.76 | 1 | 0.01 | 4.99 | 0.85 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Sus | 1 | 4.55 | 1 | 4.76 | 0.01 | 4.79 | 0.81 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Equus | 9 | 40.91 | 4 | 9 | 42.86 | 4 | 0.07 | 41.10 | 3.49 | 1/0/1/0 | ||

| Stephanorhinus | 1 | 4.55 | 1 | 1 | 4.76 | 1 | 0.01 | 4.18 | 0.71 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Large herbivore | 10 | 8 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 6 | |||||||||||

| VII | 89 (64) | 32 (34) | 57 | 13 | 0.07 | 0.44 | 0.88 | 8 | 2.08 | |||

| BB | 27 | 30.34 | 5 | 10 | 17.54 | 3 | 0.08 | 19.10 | 4.24 | 0/0/2/0 | ||

| Cervus | 25 | 28.09 | 9 | 21 | 36.84 | 3 | 0.18 | 40.11 | 17.80 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Sus | 1 | 1.12 | 1 | 1.75 | 0.01 | 1.83 | 0.81 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Equus | 28 | 31.46 | 14 | 19 | 33.33 | 5 | 0.13 | 29.70 | 6.59 | 1/0/1/0 | ||

| Stephanorhinus | 6 | 6.74 | 4 | 5 | 8.77 | 2 | 0.04 | 7.99 | 3.55 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Palaeoloxodon | 2 | 2.25 | 1 | 1.75 | 0.01 | 1.27 | 0.56 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Large herbivore | 29 | 16 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 26 | 15 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 9 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 3 | |||||||||||

| VIII | 51 (29) | 20 (21) | 36 | 17 | 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 10 | 1.30 | |||

| BB | 16 | 31.37 | 1 | 7 | 19.44 | 1 | 0.05 | 19.22 | 5.08 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Cervus | 9 | 17.65 | 4 | 7 | 19.44 | 3 | 0.06 | 22.42 | 5.93 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Dama | 1 | 1.96 | 1 | 1 | 2.78 | 1 | 0.01 | 3.20 | 0.85 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Sus | 1 | 1.96 | 1 | 2.78 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Equus | 21 | 41.18 | 12 | 17 | 47.22 | 10 | 0.13 | 49.80 | 3.29 | 1/0/2/1 | ||

| Stephanorhinus | 3 | 5.88 | 2 | 3 | 8.33 | 2 | 0.01 | 5.36 | 0.71 | 1/0/1/0 | ||

| Large herbivore | 22 | 17 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 3 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 1 | |||||||||||

| IX | 275 (373) | 133 (238) | 135 | 48 | 0.18 | 0.88 | 1.64 | 11 | 2.41 | |||

| BB | 67 | 24.36 | 27 | 31 | 22.96 | 10 | 0.19 | 21.25 | 6.21 | 0/1/2/0 | ||

| Cervus | 50 | 18.18 | 32 | 22 | 16.30 | 8 | 0.18 | 20.29 | 17.80 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Dama | 9 | 3.27 | 5 | 6 | 4.44 | 2 | 0.05 | 5.80 | 5.08 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Sus | 9 | 3.27 | 8 | 5.93 | 0.03 | 3.71 | 3.25 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Equus | 128 | 46.55 | 65 | 59 | 43.70 | 24 | 0.38 | 43.30 | 9.50 | 1/1/2/0 | ||

| Stephanorhinus | 12 | 4.36 | 4 | 9 | 6.67 | 4 | 0.05 | 5.66 | 4.96 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Large herbivore | 204 | 144 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 101 | 62 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 68 | 32 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 14 | |||||||||||

| X | 185 (205) | 81 (120) | 107 | 39 | 0.14 | 0.71 | 0.83 | 20 | 2.58 | |||

| BB | 26 | 14.05 | 14 | 21 | 19.63 | 9 | 0.14 | 20.10 | 4.80 | 1/1/3/0 | ||

| Cervus | 36 | 19.46 | 16 | 23 | 21.50 | 11 | 0.19 | 27.20 | 6.21 | 1/1/2/1 | ||

| Dama | 6 | 3.24 | 3 | 6 | 5.61 | 3 | 0.04 | 5.91 | 4.24 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Sus | 14 | 7.57 | 8 | 7.48 | 0.06 | 7.94 | 1.90 | 1/0/2/0 | ||||

| Equus | 102 | 55.14 | 48 | 48 | 44.86 | 16 | 0.27 | 37.86 | 5.43 | 1/1/2/1 | ||

| Stephanorhinus | 1 | 0.54 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.71 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Large herbivore | 108 | 76 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 56 | 29 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 41 | 15 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 9 | |||||||||||

| XI | 166 (231) | 88 (130) | 98 | 38 | 0.13 | 0.62 | 1.09 | 12 | 7.24 | |||

| BB | 24 | 14.46 | 10 | 16 | 16.33 | 5 | 0.10 | 16.54 | 3.39 | 0/1/2/0 | ||

| Cervus | 39 | 23.49 | 27 | 17 | 17.35 | 8 | 0.12 | 19.29 | 11.86 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Dama | 9 | 5.42 | 5 | 6 | 6.12 | 4 | 0.05 | 8.27 | 5.08 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Sus | 13 | 7.83 | 7 | 11 | 11.22 | 5 | 0.07 | 11.90 | 3.66 | 1/0/1/0 | ||

| Equus | 74 | 44.58 | 39 | 44 | 44.90 | 16 | 0.26 | 42.86 | 6.59 | 1/1/2/0 | ||

| Stephanorhinus | 7 | 4.22 | 4 | 4.08 | 0.01 | 1.15 | 0.71 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Large herbivore | 130 | 74 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 77 | 49 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 24 | 7 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 27 | |||||||||||

| XII | 76 (127) | 31 (61) | 53 | 18 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.64 | 9 | 5.52 | |||

| BB | 8 | 10.53 | 2 | 7 | 13.21 | 1 | 0.03 | 10.40 | 3.39 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Cervus | 19 | 25.00 | 11 | 12 | 22.64 | 6 | 0.10 | 31.19 | 5.08 | 1/0/1/0 | ||

| Dama | 1 | 1.32 | 1 | 1.89 | 0.01 | 2.60 | 0.85 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Sus | 8 | 10.53 | 6 | 11.32 | 0.02 | 4.99 | 1.63 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Equus | 33 | 43.42 | 16 | 21 | 39.62 | 9 | 0.13 | 40.41 | 6.59 | 1/0/1/0 | ||

| Stephanorhinus | 6 | 7.89 | 2 | 5 | 9.43 | 2 | 0.03 | 8.70 | 2.84 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Palaeoloxodon | 1 | 1.32 | 1 | 1.89 | 0.01 | 1.72 | 0.56 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Large herbivore | 53 | 28 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 52 | 27 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 22 | 6 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 10 | |||||||||||

| XIII | 114 (277) | 53 (162) | 78 | 28 | 0.10 | 0.52 | 0.95 | 11 | 11.34 | |||

| BB | 35 | 30.70 | 13 | 25 | 32.05 | 7 | 0.16 | 31.21 | 5.37 | 1/0/2/0 | ||

| Cervus | 23 | 20.18 | 12 | 15 | 19.23 | 6 | 0.11 | 21.35 | 5.51 | 1/0/1/0 | ||

| Dama | 9 | 7.89 | 5 | 8 | 10.26 | 3 | 0.06 | 11.50 | 5.93 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Sus | 5 | 4.39 | 1 | 4 | 5.13 | 1 | 0.02 | 3.15 | 1.63 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Equus | 39 | 34.21 | 21 | 23 | 29.49 | 10 | 0.16 | 30.05 | 5.17 | 1/0/2/0 | ||

| Stephanorhinus | 3 | 2.63 | 1 | 3 | 3.85 | 1 | 0.01 | 2.75 | 1.42 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Large herbivore | 128 | 78 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 102 | 69 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 47 | 15 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 39 | |||||||||||

| XIV | 46 (100) | 29 (72) | 37 | 18 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.84 | 7 | 2.99 | |||

| BB | 13 | 28.26 | 7 | 10 | 27.03 | 5 | 0.06 | 24.54 | 2.97 | 0/0/2/0 | ||

| Cervus | 7 | 15.22 | 5 | 7 | 18.92 | 4 | 0.06 | 24.54 | 5.93 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Sus | 4 | 8.70 | 4 | 10.81 | 0.01 | 3.36 | 0.81 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Equus | 20 | 43.48 | 14 | 14 | 37.84 | 8 | 0.10 | 41.69 | 5.04 | 0/0/2/0 | ||

| Stephanorhinus | 2 | 4.35 | 3 | 2 | 5.41 | 1 | 0.01 | 5.87 | 1.42 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Large herbivore | 33 | 23 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 55 | 45 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 12 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 4 | |||||||||||

| XV | 241 (279) | 108 (178) | 157 | 48 | 0.21 | 0.78 | 1.50 | 14 | 4.80 | |||

| BB | 47 | 19.50 | 25 | 26 | 16.56 | 9 | 0.17 | 21.60 | 8.47 | 0/0/2/0 | ||

| Cervus | 36 | 14.94 | 20 | 23 | 14.65 | 10 | 0.19 | 23.76 | 9.32 | 1/0/1/0 | ||

| Dama | 6 | 2.49 | 3 | 6 | 3.82 | 3 | 0.04 | 5.40 | 4.24 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Sus | 6 | 2.49 | 6 | 3.82 | 0.03 | 4.14 | 1.08 | 1/1/1/0 | ||||

| Equus | 142 | 58.92 | 58 | 92 | 58.60 | 24 | 0.33 | 41.49 | 6.51 | 1/1/3/0 | ||

| Stephanorhinus | 4 | 1.66 | 2 | 4 | 2.55 | 2 | 0.03 | 3.61 | 2.84 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Large herbivore | 133 | 104 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 84 | 52 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 62 | 22 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 22 | |||||||||||

| XVI | 77 (72) | 37 (56) | 56 | 24 | 0.07 | 0.32 | 0.83 | 9 | 1.64 | |||

| BB | 1 | 1.30 | 1 | 1 | 1.79 | 1 | 0.01 | 2.64 | 0.85 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Cervus | 15 | 19.48 | 11 | 11 | 19.64 | 7 | 0.08 | 23.79 | 3.81 | 0/0/2/0 | ||

| Dama | 6 | 7.79 | 2 | 5 | 8.93 | 1 | 0.04 | 13.22 | 4.24 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Sus | 1 | 1.30 | 1 | 1.79 | 0.01 | 2.54 | 0.81 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Equus | 53 | 68.83 | 22 | 37 | 66.07 | 14 | 0.18 | 55.61 | 5.94 | 1/0/2/0 | ||

| Stephanorhinus | 1 | 1.30 | 1 | 1 | 1.79 | 1 | 0.01 | 2.21 | 0.71 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Large herbivore | 34 | 30 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 11 | 6 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 27 | 20 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 2 | |||||||||||

| XVII | 22 (21) | 13 (11) | 18 | 10 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 7 | 7.69 | |||

| Capra | 1 | 4.76 | 1 | 5.56 | 0.01 | 6.47 | 0.85 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Cervus | 13 | 61.90 | 10 | 10 | 55.56 | 7 | 0.08 | 64.72 | 8.47 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Dama | 2 | 9.52 | 2 | 11.11 | 0.01 | 6.47 | 0.85 | 0/0/1/0 | ||||

| Sus | 3 | 14.29 | 1 | 3 | 16.67 | 1 | 0.01 | 6.21 | 0.41 | 1/0/1/0 | ||

| Equus | 2 | 9.52 | 1 | 2 | 11.11 | 1 | 0.02 | 11.84 | 1.55 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Palaeoloxodon | 1 | 4.76 | 1 | 1 | 5.56 | 1 | 0.01 | 4.29 | 0.56 | 0/0/1/0 | ||

| Large herbivore | 13 | 9 | ||||||||||

| Small herbívore | 4 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Undet. | 4 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Carnivore | 3 | |||||||||||

| Total | 8 ungulates | 1,394 (1,975) | 652 (1,165) | 883 | 326 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 137 | 4.89 | |||

| 4 carnivores* | 100 (45) |

Composition of the faunal assemblage of J/K stratigraphic profile and index.

NISP, number of identified specimens; MNI, minimum number of individuals; MNE, minimum number of elements; LB, long bones; MAU, minimal animal unit; %ΣMAU, percentage of MAU sum; %SI, percentage of survivorship index; C/H, carnivore/herbivore; I, infant; J, juvenile; A, adult; S, senile.

Carnivores: view Supplementary Table S1.

The preservation state of the fossil remains is generally good, as they exhibit a high degree of mineralization. Between 65 and 80% of the remains, depending on the level, show no cortical modifications, and when they do, they appear as small dissolution pits. There are no evident signs of weathering (Behrensmeyer, 1978) throughout the sequence, although longitudinal and transverse fissures (25%) filled with precipitated calcite are common, sometimes contributing to the compaction of the fossil due to the weight of the sediments. Most of the fissures appear to be a direct result of fire action (Cain, 2005; Stiner, 2005; Théry-Parisot et al., 2010) and their subsequent development through fossil-diagenetic karstification processes. The most frequent alterations are calcite concretions and the presence of manganese oxide distributed as small dendritic patterns on the cortical surface. In contrast, biochemical modifications are scarcely described. Moisture and carbonated waters have been the main agents of alteration, aside from the anthropogenic effects of fire (Solano García, 2024).

The accumulation is anthropogenic in origin, as evidenced by the large volume of lithic tools, retouchers (Moigne et al., 2016), and anthropogenic activities related to butchery and food cooking (Barroso Ruíz et al., 2011). Carnivore remains are scarce throughout the assemblage (3.9%), and their impact is minimal (0.8%), except in unit XIII (1%), where there is a slight increase but with low activity (0.5%). Additionally, the skeletal representation and the dominant adult mortality profile (Stiner, 1994; Steele, 2004), along with the abundance of cut marks, intentional fracturing, and extensive use of fire, also suggest an anthropogenic accumulation. Access to carcasses was likely primary for large ungulates (Bos, Bison, Equus, and Cervus) and secondary for larger animals like elephants or rhinoceroses and probably Sus (Solano García, 2024).

It is important to note that the excavation area of each grid, except for J7, does not reach a full square meter in surface area. The excavation of this zone corresponds to the edge of the mining shaft dug along the K band (Figure 1D). Consequently, depending on the width of the sides and the depth, the excavated surface area will vary. On the other hand, grid J7, which covers the entire surface, began to be excavated in 1995 from level V at level XIII. Therefore, the material density is biased and uneven across different levels and may influence the frequencies of the number of identified remains. Nevertheless, the sample presented allows for the first diachronic zooarchaeological approach to nearly the entire stratigraphic sequence that we have so far.

3.2 Faunal analysis procedures

Taxonomic and anatomical identifications were carried out using the osteological collection of the Center for Prehistoric Research of Tautavel (CERPT) and specialized reference literature (Heintz, 1970; Pales et al., 1971; Schmid, 1972; Hillson, 2005; Barone, 2010). At the taxonomic level, some remains could be identified as Bos primigenius and Bos bison (Brugal, 1984; Gee, 1993), but for the purposes of this study, they have been unified under Bos/Bison (BB). When taxonomic identification was not possible, size-based criteria (adapted from Bunn, 1981; Bunn et al., 1986)Bunn, 1981; Bunn et al., 1986): were used to categorize animal mass: (1) small, 5–100 kg (e.g., Capra, Dama, Canis, Lynx); (2) medium, 100–250 kg (e.g., Sus scrofa, Cervus elaphus, Equus hydruntinus); (3) medium-large, 250–500 kg (e.g., Equus ferus, Ursidae); (4) large, 500–800 kg (e.g., Bos primigenius, Bison priscus); (5) very large, >800 kg (e.g., Stephanorhinus, Palaeoloxodon). To simplify the analysis, unidentified herbivore remains were grouped into two sets: large herbivores (LH: categories 3, 4, 5), mainly composed of categories 3 and 4; and small herbivores (SH: categories 1, 2). Anatomically unidentified remains were classified into one of the following categories: long bone, flat bone, and articular bone (Saladié et al., 2011).

The determination of age at death, when possible, is based on the fusion of epiphyses and dental eruption/replacement patterns and wear (Mariezkurrena, 1983; Wegrzyn and Serwatka, 1984; Stiner, 1990, 1998; Forsten and Moigne, 1998; Guadelli, 1998; Hillson, 2005; Barone, 2010) and has been classified into infant, juvenile, adult, and senile categories.

Abundance measures for all ungulates were recorded following the number of identified specimens (NISP), the minimum number of elements (MNE), the minimum number of individuals (MNI), and the minimum animal unit (MAU). The skeletal survival index per individual (SI) was calculated using the following formula: MAU × 100/MNI (Binford, 1981; Grayson, 1984; Klein and Cruz Uribe, 1984; Lyman, 1994a, 2008). To synthesize the information for each ungulate by stratigraphic units, the MAU for each taxon was calculated based on the total MNE (excluding teeth) and the complete skeleton, along with its corresponding SI. The %ΣMAU represents the proportion of MAU for each taxon within each stratigraphic unit as a summary value, and not Binford (1981) index, which has been replaced by the SI equivalent. However, it has been verified that the results are equivalent. The carnivore/herbivore percentage ratio (Klein and Cruz Uribe, 1984) has also been included. Additionally, the total MAU for each stratigraphic unit was calculated by summing all the complete skeletons present for each taxon.

For the analysis of the anatomical representation of the stratigraphic sequence, given the large number of skeletal elements and with the aim of identifying general exploitation patterns and synthesizing the results, the elements have been grouped into six main categories: skull, axial, long bones, girdles (scapula + coxal), articular bones, and phalanges. However, individual elements will also be used for analysis, and they will be referenced when necessary.

To analyze the fragmentation of the ungulate assemblage by stratigraphic unit, the MNE/NISP ratio was used, applied also to long bones. The intensity of fragmentation was calculated by counting incomplete elements (fragments/NISP × 100) and comparing it with the overall set of fragmented and complete remains. The degree of fragmentation was also measured based on the integrity of the remains and the circumference size of long bones (Villa and Mahieu, 1991). These data were complemented by a descriptive statistical analysis of the length of the remains and a count of all small indeterminate splinters not assigned to size categories.

Additionally, to verify the intensity of fracturing, all fragmented and complete long bones were counted by stratigraphic unit, taking into account the diaphysis and epiphysis ratios (Todd and Rapson, 1988; Lyman, 1994b, 2008). The count of fractured phalanges was also used as an indicator of intensified marrow exploitation (Starkovich, 2017) along with the count of mandibles. The longitudinal opening of these types of elements is a clear distinctive sign of marrow extraction.

Anthropogenic activity has been synthesized based on the count of cut marks (Binford, 1981; Blumenschine et al., 1996; Domínguez-Rodrigo et al., 2009), percussion marks (Blumenschine and Selvaggio, 1988; Blumenschine et al., 1996; Pickering and Egeland, 2006; De Juana and Domínguez-Rodrigo, 2011), fresh bone fractures (Villa and Mahieu, 1991) and burned bones (Shipman et al., 1984; Stiner et al., 1995). Additionally, the number of carnivore tooth marks (Bunn, 1981; Fisher, 1995; Blumenschine et al., 1996) has been counted as contrasting information, highlighting carnivores as modifying agents in the assemblage.

The observation of surface bone modifications was carried out using a 10× handheld magnifying lens and a Dinolite device. The graphical analysis of the anatomical representation of each taxon by stratigraphic unit was performed using ArcGIS® software by Esri (ESRI Inc, 2023), where the MAU normalized by NISP was utilized (Orton, 2010). All statistical analysis and graphical output were conducted using the R programming language (R Core Team, 2024).

4 Results

4.1. Taxonomic and anatomical distribution

This study analyzed 1,394 remains (39.67%) identified as belonging to ungulates. As complementary information, we also present the count of unidentified material (56.2%), classified into the categories of Large Herbivores and Small Herbivores (44.65%), as well as the number of carnivore remains (4.13%) and indeterminate remains (11.55%) for each stratigraphic unit (3,514 NR; Table 1).

The number of remains is quite disproportionate throughout the entire sequence, as is the NISP (CV = 124.2 and 86.2, respectively), with a marked bias in the upper layers (IV–VI) and layer XVII, while a higher number is observed in the central layers. This bias is attributed to the smaller volume excavated in these levels, although level V may also show a potential research bias with a lower identification rate of around 0.2%, compared to the 3.1% average for the total NR. Despite the marked discrepancies in NISP throughout the sequence, we have confirmed that the use of MAU and SI as analytical variables does not affect the results and is correlatable with the material density per unit of analysis.

A total of nine ungulate taxa have been identified throughout the sequence: Bos primigenius, Bison priscus, Cervus elaphus, Dama dama, Sus scrofa, Equus ferus, Stephanorhinus hemitoechus, Palaeoloxodon antiquus, and Capra sp. (Barroso Ruíz et al., 2011). The first six taxa, counting B. priscus and B. primigenius as a single group (BB), are present in almost the entire sequence, with the exception of Dama, which is absent in levels V, VII, and XIV; Stephanorhinus in levels V and XVII; and BB in level XVII. On the other hand, Palaeoloxodon is only found in levels VII, XII, and XVII, and Capra in level XVII. The absence of Dama and Stephanorhinus in level V may be due to the possible excavation or research biases mentioned earlier.

Carnivores are present in all levels of the analyzed sequence (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1), although there is considerable variability in the number of remains, ranging from just one in level VIII to 39 remains in level XIII. Unit VI has the highest carnivore-herbivore ratio (17.14%), followed by unit XIII (11.34%), within an overall carnivore-herbivore ratio of 4.89%. Among the carnivores, lynx remains are the most abundant (46.1%), followed by bear (39.2%), wolf (11.8%), and wildcat (2.9%). Bears have the widest distribution across the entire J/K stratigraphic sequence, except in levels V to VIII, followed by lynx, present in eight levels, wolves in six, and wildcats in three. However, according to Barroso Ruíz et al. (2011), brown bears are the most represented in NR across the entire site.

The predominant taxon among herbivores throughout the stratigraphic sequence (Figure 3), based on representation indices (NISP, = 47.2, σ = 46.8; MNE, = 28.1, σ = 25.5; MAU, = 0.16, σ = 0.11), is the horse, followed by BB (NISP, = 19.8, σ = 19.5; MNE, = 12.85, σ = 9.95; MAU, = 0.08, σ = 0.06) and red deer, with very similar values (NISP, = 20.2, σ = 15.2; MNE, = 12.8, σ = 7.55; MAU, = 0.10, σ = 0.06), although the red deer's MAU is slightly higher or comparable. The rest of the taxa, with lower representativity in terms of the number of remains and elements, are represented by wild boar, fallow deer, rhinoceros, elephant, and ibex. The number of individuals also confirms this taxonomic hierarchy, with horse (39), BB (26), red deer (24), wild boar (20), but more rhinoceros individuals (13) than fallow deer (11), and lastly, elephant (3) and ibex (1).

Figure 3

Box plots of the primary taxonomic representation across the entire stratigraphic assemblage for the four main indices.

The total MNI (Minimum Number of Individuals) is 137 for the ungulate species (Table 1). The vast majority correspond to adult individuals (74.45%), compared to 16.8% juveniles, 6.6% subadults, and 2.2% elderly. The central levels, between VIII and XV, have the highest proportion of individuals, with a peak in level X, which contains 20 individuals, including two of the three elderly ones. Levels IX and XV have the highest proportion of elements relative to those expected (MNE/MNI; 12.3 and 11.2, respectively), followed by VII (8.2), XI, and XIII (7.1). The taxon with the greatest anatomical representation in this case is Equus (10.1), followed by Cervus (7.5) and BB (6.4), on one hand, and Dama (4), Stephanorhinus (3), and Sus (2.9), on the other. The species with the largest number of juveniles are Equus and Cervus (25% and 25.6%, respectively), followed by wild boar (20%), BB, and rhinoceros (7.7%). Subadults are present in BB (11.5%), Equus (10.3%), Sus (5%), and Cervus (4.2%), while elderly individuals are found in Equus (5.1%) and Cervus (4.2%). The remainder belong to adults, with proportions above 60%. In the case of fallow deer, all individuals are adults.

It is clear that the means of the main ungulate taxa show variability (Figure 3). After comparing the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances (S-W and Levene tests) for the indices of the six main ungulates (NISP: D = 0.26, df = 80, p < 0.001; MNE: D = 0.24, df = 80, p < 0.001; MAU: D = 0.207, df = 80, p < 0.001), a K–W test, effect size (η2; Wolverton et al., 2016), and post-hoc tests were conducted. The results indicate statistically significant differences between the means of the six taxa (NISP: H = 29.35, df = 5, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.338; MNE: H = 31.29, df = 5, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.365; MAU: H = 38.48, df = 5, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.465; SI: H = 35.795, df = 5, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.428). These results suggest the differences are reliable. Post-hoc comparisons (Wilcox & Conover-Iman test using Holm's method) identified a greater similarity between BB, Cervus, and Equus (Group 1) (NISP: H = 2.97, df = 2, p = 0.226, η2 = 0.0129; MNE: H = 3.68, df = 2, p = 0.159, η2 = 0.0223; MAU: H = 3.81, df = 2, p = 0.149, η2 = 0.0242) and between Dama, Sus, and Rhino (Group 2) (NISP: H = 0.34, df = 2, p = 0.843, η2 = −0.0221; MNE: H = 0.62, df = 2, p = 0.734, η2 = −0.0184; MAU: H = 2.87, df = 2, p = 0.238, η2 = 0.0116). In summary, we can assume two main distinct groups based on their representativity in the stratigraphic sequence, with the first group showing significantly higher representativity compared to the second (Figure 4).

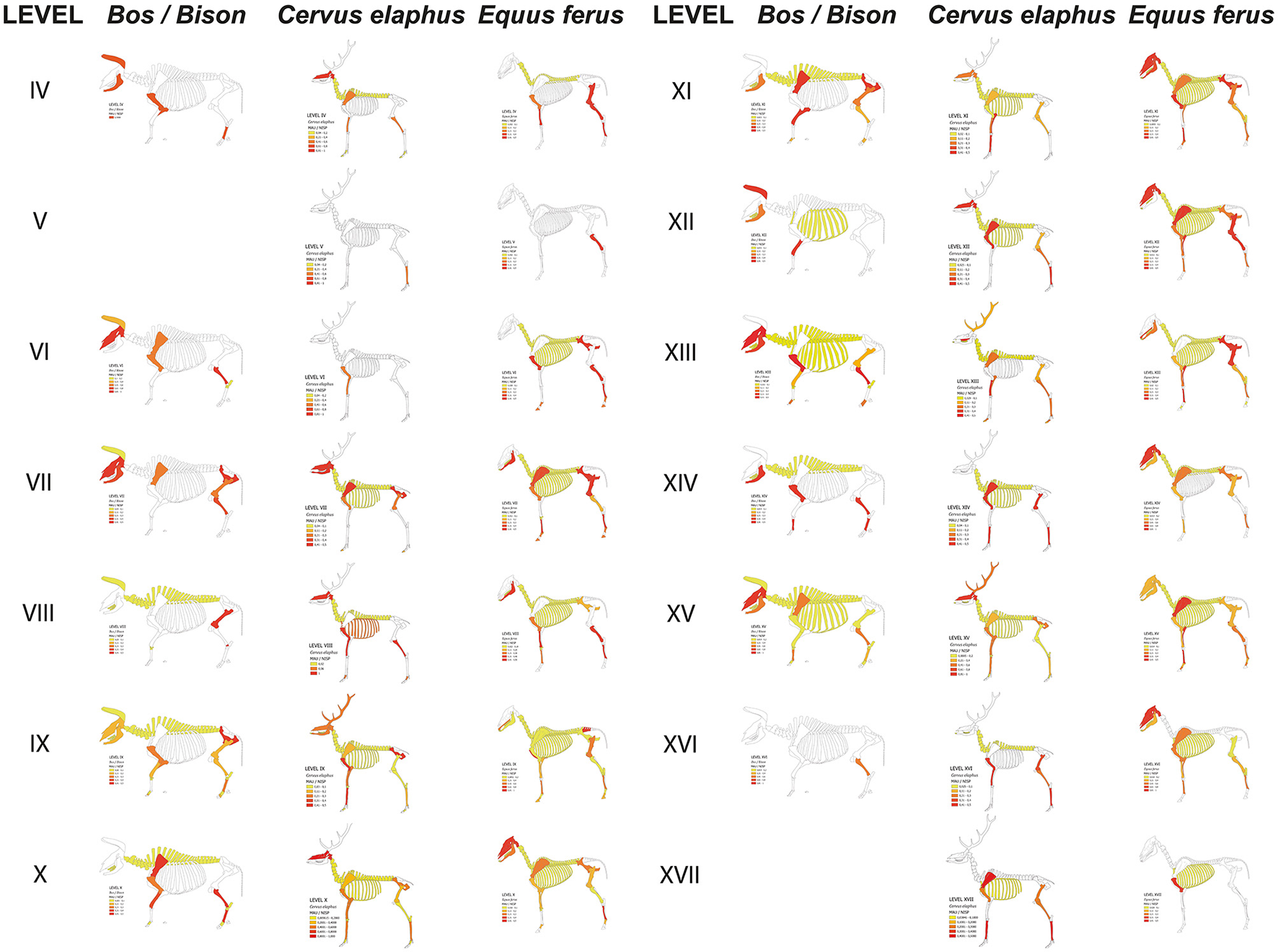

Figure 4

Anatomical distribution of the three main taxa (group 1) across the stratigraphic sequence (all taxa in Supplementary Figure S1). The representativity of each element (ribs and vertebrae have been generalized) is measured using the MAU and NISP to normalize the color gradient (Vector templates from https://www.archeozoo.org/).

The results indicate that Group 1 forms the core trio of species with the highest taxonomic and anatomical representation within the assemblage and throughout the entire stratigraphic sequence. This does not imply that there are no differences between stratigraphic levels, as it is clear that in some levels the representation of these taxa is higher than others, but they always maintain a similar presence per level, comparable to the rest of the layers. Group 2 behaves similarly according to the data, but with a much lower representation. When we applied the same test for the survival index (%SI), which takes into account the MNI, it confirmed the similarity within the first group (%SI: H = 4.73, df = 2, p = 0.94, η2 = 0.0364), and within the second group (%SI: H = 8.06, df = 2, p = 0.0177, η2 = 0.0808). However, there is greater similarity between Rhino and Sus. This is because the skeletal survival of Dama is more similar to that of BB.

The overall skeletal representation based on MNE is dominated by long bones (37.51%), cranial remains including isolated teeth and antlers (31.81%), and axial skeleton elements (12.2%), followed by articular bones, girdles, and phalanges. However, the MAU (Figure 5) indicates a slightly different distribution, where long bones still dominate (57.57%) along with cranial remains (24.70%), but these are followed by girdles (9.66%), articular bones (3.14%), phalanges (2.84%), and axial elements (2.10%). This same distribution is reflected in the skeletal survival index, although the representation of phalanges (2.8%) is slightly higher than that of articular bones (2.4%).

Figure 5

Box plots of the anatomical representation of the main taxa (left) and skeletal element categories (right) according to the MAU and %SI.

When comparing the MAU by taxa (Figure 5), the same general distribution is observed, with long bones predominating, followed by cranial elements, phalanges, or articular and axial bones, except for Sus scrofa. The wild boar shows a different pattern, where cranial elements dominate (75%) compared to long bones (20.3%), followed by articular bones (2.5%), phalanges (1.9%), and axial elements (0.2%).

According to the MAU by anatomical elements (Figure 4, Supplementary Figure S1), metapodials are the most represented (16.7%), followed by tibiae (10.40%), humeri (8.73%), femora (8.36%), radii (7.61%), and ulnae (5.57%). However, if we break down all the elements, tibiae (10.28%) are the best represented, followed by cranial elements (9.92%), mandibles (9.00%), metatarsals (8.88%), humeri (8.63%), femora (8.26%), radii (7.53%), scapulae (5.51%), ulnae (5.51%), metacarpals (4.34%), and coxae (4.04%). The remaining elements are below 2%.

At the stratigraphic level, most layers contain skewed (non-symmetrical) data. Only levels X, XI, and XV show data symmetry. However, when we analyse the MAU (Figure 5) as a contrast index, we confirm that there is no statistically significant difference between them, based on the K–W test (H = 14.904, df = 13, p = 0.3134, η2 = 0.00362) and the two-sided Jonckheere-Terpstra test (JT = 65,792, p = 0.8461). In contrast, the %SI (Figure 5) shows significant differences (H = 29.878, df = 13, p = 0.005, η2 = 0.0321), although the effect size is very close. This is because the differences are solely related to layer X. Thus, the JT test, which is more robust and takes into account the order of the stratigraphic sequence, indicates similarity (JT = 68,622, p = 0.24). This result supports the feasibility of conducting analyses to identify differences and similarities between species groups and anatomical categories for the entire assemblage. In fact, the correspondence analysis between anatomical categories throughout the sequence shows how most levels cluster around the long bones and near the origin of the coordinates, indicating little variation (Figure 6B).

Figure 6

Graphical output of the correspondence analysis between the main taxa (A) and levels (B) by anatomical element categories based on the MAU. The ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals for taxa and levels (blue) and elements (red).

The species with the highest number of elements are Equus, Cervus, BB, Sus, and Dama. However, as we have seen, Sus presents a different skeletal configuration (Supplementary Figure S1). When comparing the total anatomical representation of the four taxa based on the MAU, there are also significant differences (H = 229.56, df = 5, p < 2.2e-16, η2 = 0.488), although post-hoc tests indicate a potential similarity between BB, Cervus, and Equus, and Dama with Cervus. However, when pairwise tests are conducted, no correspondence is found. This is due to a certain variability in combinations of categories by elements. When analyzing these skeletal categories for the four mentioned taxa, there is statistically significant similarity between skulls, long bones, and girdles (H = 2.6531, df = 2, p = 0.2654, η2 = 0.00197), with the distribution of skulls and girdles being much more similar between BB, Cervus, and Equus (H = 2.0769, df = 2, p = 0.354, η2 = 0.000254). These results indicate a similar configuration among the species in Group 1, with a predominance of long bones, followed by skulls and girdles and mandibles in similar proportions (Figure 6A). As we have seen, Dama presents a distribution approaching that of Group 1, but its lower representation, for now, does not allow it to be fully included in that group and instead places it in Group 2, as noted earlier. Group 2 shows statistical similarity between articular bones and phalanges (H = 0.15342, df = 1, p = 0.6953, -η2 = 0.0470), long bones and girdles (H = 0.32613, df = 1, p = 0.5679, η2 = −0.0157), and skulls and girdles (H = 1.3651, df = 1, p = 0.2427, η2 = 0.00936).

The survival index for the entire assemblage (Table 1) shows that the red deer has the highest skeletal survival (34%), followed by the horse (24.3%) and BB (17.5%). In Group 2, with lower indices, the best represented is the fallow deer (11.2%), followed by the rhinoceros (7%) and the wild boar (6.1%). At the skeletal level (Figure 5), long bones are the best represented (58.1%) for all taxa except for the wild boar, where cranial remains predominate. Cranial remains are the second most represented (25.5%) for the other taxa, followed by girdles (9.2%), phalanges (2.8%), and articular bones (2.4%). Among the long bones, metapodials have the highest survival (15.5%), followed by tibiae and humeri (10.5%). These are followed by femora (8.3%), radii (7.4%), and ulnae (5.4%). Scapulae (5.9%) are better represented than pelves (3.3%), and phalanges (2.8%) are better represented than articular bones (2.4%), although the difference is minimal. As can be seen, the survival of the girdles is consistent with that of humeri and femora, considering their anatomical connection. Additionally, it indicates a higher representativity of anterior stylopodia and posterior zeugopodia, although the MAU is similar for the stylopodia, and the tibia stands out more than the radius among the zeugopodia.

Lastly, we conducted an analysis of the distribution of forelimbs and hindlimbs based on the MNE. At first glance, the frequency of elements is markedly uneven between Groups 1 and 2 (Figure 7A). As a preliminary approach, we calculated the Log (Forelimb/Hindlimb) ratio for all species with at least two elements within the same level. The overall average for the entire dataset is = −0.16, σ = 0.54, min = −1.39, max = 0.85, indicating a near balance between forelimbs and hindlimbs, though with a slight tendency toward the hindlimb. Some taxa, such as Cervus, lean toward the forelimb (Figures 7B, C), while others, like Equus and Sus, show a preference for the hindlimb.

Figure 7

Exploración estadística de la relacion forelimb hindlimb. (A) Distribución de la frecuencia absoluta de elementos de forelimb y hindlimb para cada especie por nivel estratigráfico. (B) Boxplot de la ratio log(forelimb/hindlimb) por especie. (C) Gráfico de densidad de la log ratio forelimb/hindlimb por especies del grupo 1. (D) Gráfico de densidad de la log ratio forelimb/hindlimb por especies del grupo 2.

This distribution is particularly apparent in the density plots (Figures 7C, D), where a clear balance can be observed in taxa such as BB and Stephanorhinus, though with a predominance toward the hindlimb, especially in the case of Equus. Stratigraphically, although there is variability and extreme values in some species like BB in Levels IV or VII, the differences are not statistically significant, even though Equus and Cervus exhibit the highest variability throughout the sequence. Taxa in Group 2 are dominated by the hindlimb at all levels, except for Dama, which shows a predominance of the forelimb in Level XV.

Since Group 2 exceeds 50% missing values, we do not consider it suitable for further analyses, as these cannot be interpreted as absences (value 0) given the current sample size and excavated area. Likewise, data imputation in this case would not provide reliable results, so we focused on Group 1 for a more detailed exploration. Missing values (BB: 15%; Cervus and Equus: 3.8%) were imputed using the “mice” algorithm (m = 5, method = “pmm”, maxit = 50) (van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011), which is robust and flexible for such distributions (BB: W = 0.94, p = 0.45; Cervus: W = 0.94, p = 0.46; Equus: W = 0.95, p = 0.545). Levene's test [Pr(>F) = 0.19, p = 0.83] indicates homogeneity of variances among species. The analysis (H = 2.29, df = 2, p = 0.32) suggests no statistically significant differences between the ratios of the three species. However, the correlations between species are low, indicating little direct relationship in terms of the forelimb-hindlimb ratio. This could suggest that their representation across stratigraphic levels is independent or influenced by different factors.

The analysis of ratios across stratigraphic levels (H = 10.82, df = 12, p = 0.54) also indicates no statistically significant differences between levels. The distributions are evenly spread and independent of stratigraphic level. However, while the variability is not statistically significant, it may still provide some stratigraphic insights.

The principal component analysis between species (Figure 8A) reveals a distinct behavior of Equus compared to BB and Cervus. Component 1 explains forelimb representation. As a result, Equus contributes very little to this component, appearing mainly in Levels VII, VIII, and XII. The distribution of BB and Cervus is the most similar throughout the sequence, showing a tendency toward the forelimb but with opposing differences in certain levels, such as XI and XVI. In this context, BB exhibits the greatest balance in forelimb-hindlimb proportions throughout the sequence, while Cervus shows a stronger tendency toward the forelimb (Figure 7C). Component 2, which explains hindlimb representation, is strongly dominated by Equus, contributing hindlimb elements across all levels except the three mentioned earlier. Except for Level VIII, entirely dominated by forelimb elements, the remaining levels tend, to varying degrees, toward the hindlimb.

Figure 8

(A) Análisis de componentes principales de la log ratio forelimb/hindlimb por niveles y especies. (B) Análisis de correspondencias de la log ratio forelimb/hindlimb por niveles y especies.

To better understand the association between species elements and stratigraphic levels, we performed a correspondence analysis (Figure 8B). Most levels cluster near the origin, suggesting a balance between forelimb and hindlimb, though with a tendency toward the hindlimb. Some levels are outliers, such as Level VIII, composed solely of forelimb elements dominated by Equus, and its opposite, Level XVII (imputed data), composed entirely of hindlimb elements dominated by BB.

There does not appear to be a clear pattern in the representation of forelimbs and hindlimbs throughout the sequence. What we can deduce is that Equus is the dominant species, with a strong representation of hindlimbs, while Cervus shows a slight tendency toward forelimbs, often contrasting with Equus at various levels. Considering that BB tends toward anatomical balance, while Equus and Cervus show opposing tendencies, the overall dataset generally reflects a balanced representation between forelimbs and hindlimbs, as indicated by the global mean and statistical tests performed.

4.2 Integrity and fragmentation of the assemblage

A total of 98.6% of the remains included in this study are fragmented, and 97.3% retain less than half of their original size (Table 2). Moreover, the vast majority (91.9%) retain between 0 and 25% of their size. Their distribution across the sequence is very homogeneous ( = 90.3, σ = 6.4, CV = 7.1), with hardly any differences in terms of integrity between stratigraphic levels. However, when analyzing the length of ungulate remains, we do find significant variability (min = 2 mm, max = 283 mm, = 49.9, σ = 30.2, CV = 60.6). The overall average for all levels is between 4.5 and 6 cm, except for layer V, which has an average length of 23 mm. These results already point to a high degree of fragmentation. In fact, the circumference of long bones is <180° in 94% of the cases ( = 93.2, σ = 8.1, CV = 8.7), and in 60% for those <90° ( = 55.2, σ = 13.6, CV = 8.7). The ratio of fractured remains is 19.9 for each complete element in the entire assemblage. An increase in this ratio is observed from the lower levels to the upper ones, but with some variability in the central levels.

Table 2

| Level | Total NR | MNE/NISP | % IFOin | Integrity | Long bone circumference | Bone length | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fragments | Complete | F/C | S/E | BB | CE | DD | SS | EF | SH | BB | CE | DD | SS | EF | SH | 0–25% | <90° | 90°-180° | 0–180° | Min (mm) | Max (mm) | Mean (mm) | SD | Median | CV | |

| IV | 46 | 2 | 23 | 3.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 86.96 | 57.14 | 42.86 | 100 | 8 | 180 | 49.47 | 33.20 | 39 | 67.10 |

| V | 173 | 26.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97.65 | 33.33 | 66.67 | 100 | 6 | 90 | 23.18 | 16.88 | 18 | 72.84 | ||||||

| VI | 43 | 1 | 43 | 2.3 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 87.5 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 81.25 | 37.50 | 62.50 | 100 | 16 | 130 | 53.13 | 23.56 | 50 | 44.34 |

| VII | 159 | 10 | 15.9 | 7.6 | 0.40 | 0.78 | 1.00 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 100 | 81.48 | 100 | 84.375 | 100 | 86.25 | 68.97 | 31.03 | 100 | 4 | 190 | 59.31 | 35.04 | 52 | 59.08 | ||

| VIII | 80 | 3 | 26.7 | 2.5 | 0.44 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 86.36 | 100 | 96.55 | 69.23 | 19.23 | 88.46 | 4 | 124 | 53.40 | 25.46 | 46.00 | 47.67 |

| IX | 659 | 21 | 31.4 | 6.4 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.42 | 0.75 | 92.42 | 96.30 | 88.89 | 77.78 | 94.89 | 91.67 | 94.72 | 58.54 | 37.56 | 96.10 | 4 | 190 | 53.84 | 27.94 | 49.00 | 51.89 |

| X | 387 | 23 | 16.8 | 6.6 | 0.72 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 0.57 | 0.47 | 1.00 | 82.76 | 94.59 | 83.33 | 92.86 | 87.88 | 90.15 | 57.47 | 34.48 | 91.95 | 2 | 276 | 52.80 | 32.23 | 48.00 | 61.05 | |

| XI | 415 | 26 | 16.0 | 4.8 | 0.64 | 0.37 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 88 | 97.67 | 100 | 85.71 | 85.71 | 100 | 89.32 | 42.11 | 45.61 | 87.72 | 3 | 258 | 47.84 | 28.58 | 42.00 | 59.74 |

| XII | 214 | 10 | 21.4 | 11.1 | 0.78 | 0.60 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.83 | 88.89 | 100 | 100 | 62.5 | 91.43 | 100 | 90 | 61.29 | 29.03 | 90.32 | 6 | 150 | 44.60 | 24.27 | 40.00 | 54.41 |

| XIII | 429 | 17 | 25.2 | 2.3 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.58 | 0.75 | 77.78 | 100 | 90 | 80 | 97.5 | 100 | 93.6 | 60.87 | 28.99 | 89.86 | 5 | 153 | 44.88 | 26.20 | 36.00 | 58.38 |

| XIV | 153 | 3 | 51 | 8.5 | 0.77 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 92.31 | 100 | 75 | 100 | 100 | 94.31 | 68.35 | 27.85 | 96.20 | 5 | 150 | 48.65 | 28.15 | 41.00 | 57.88 | ||

| XV | 536 | 41 | 13.1 | 5.1 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 92.31 | 95.24 | 83.33 | 100 | 80.56 | 100 | 90.81 | 61.26 | 32.98 | 94.24 | 2 | 283 | 51.96 | 36.13 | 44.00 | 69.55 |

| XVI | 144 | 14 | 10.3 | 4.3 | 1.00 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 1.00 | 0.65 | 1.00 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97.22 | 66.67 | 33.33 | 100 | 5 | 142 | 49.60 | 27.33 | 40 | 55.09 |

| XVII | 46 | 4 | 11.5 | 2.3 | 0.69 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 100 | 100 | 66.67 | 100 | 75 | 30 | 40 | 70 | 10 | 105 | 45.43 | 20.39 | 45 | 44.87 | ||||

| Total | mean | 3,484 | 175 | 19.9 | 5.6 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 92.46 | 97.52 | 95.05 | 85.04 | 93.48 | 99.24 | 90.27 | 55.19 | 38.01 | 93.20 | 2 | 283 | 49.89 | 30.22 | 44 | 60.58 |

Quantification of bone fragmentation for the entire analyzed ungulate assemblage based on various indices.

NR, number of remains; F/C, fragmented/complete; S/E, shafts/epiphyses; % IFOin, intensity of fragmentation.

The highest degree of fragmentation is observed in Group 1, with MNE/NISP averages (Table 3) around 0.7, in the following order: Equus, BB, and Cervus. In contrast, Group 2 has values above 0.9: Rhino, Dama, and Sus. Among skeletal categories, cranial elements and long bones are the most fragmented (0.76), followed by girdles (0.79), axial elements (0.8), and phalanges (0.9). Horns and antlers (0.49), along with femora (0.59), exhibit the highest degree of fragmentation, followed by tibiae (0.7) and radii (0.72). Next are skull remains, humeri, scapulae, ribs, and vertebrae (0.74–0.82). A third group consists of pelvises, teeth, metapodials, ulnae, and phalanges (0.83–0.90), and finally, articular bones, which are mostly complete (0.97). If we compare the index solely for long bones, again the horse, BB, and red deer show values between 0.7 and 0.76, followed by the fallow deer (0.86), with wild boar and rhinoceros above 0.96. However, when we analyse the intensity of fragmentation using the %IFOin (Table 2), which considers whole elements, we observe that red deer and fallow deer have the highest values, followed by the horse, BB, and rhinoceros. The wild boar shows the lowest fragmentation intensity, as its anatomical configuration, dominated by teeth and largely complete articular bones, reduces the proportion of fractured elements.

Table 3

| Elements | Shafts | Epiphysis | Completes | Full shafts | Full epiphysis | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humerus | 75 | 25 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| Radio-ulna | 64 | 46 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 110 |

| Metacarpal | 9 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 27 |

| Femur | 93 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 122 |

| Tibia | 104 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 137 |

| Metatarsal | 43 | 27 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 72 |

| Metapodial | 57 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 79 |

| Long bones | 855 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 889 |

| Total | 1,300 | 234 | 2 | 2 | 26 | 1,536 |

| Elements | Fractured | F. lengthwise | % FI | Complete | C/F | Total |

| Phalanx I | 33 | 3 | 9.09 | 4 | 0.12 | 40 |

| Phalanx II | 13 | 1 | 7.69 | 3 | 0.23 | 17 |

| Phalanx III | 11 | 1 | 9.09 | 6 | 0.55 | 18 |

| Phalanx ind. | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | ||

| Total phalanx | 61 | 5 | 8.20 | 13 | 0.21 | 79 |

| Mandibles | 57 | 37 | 64.91 | 0 | 94 |

Quantification of the fragmentation of long bones, phalanges, and mandibles of ungulates.

%FI, percentage of longitudinal fractures; C/F, ratio of complete elements.

Long bones are the most represented in the assemblage (n = 1,817). Of these, 35.88% have been identified (NISP = 652), with an MNE of 328. Within this group, we found only two complete elements (metatarsals), two complete shafts (humerus and metatarsal), and 26 complete epiphyses (1.6%). The remainder consists of diaphyses (83.1%) and fragmented epiphyses (14.9%). The overall ratio between shafts and epiphyses is 5.56. Among the identified elements, tibiae and femora are the best represented, followed by radii-ulnae and humeri. Metapodials, as a group, are well represented, with metatarsals being the most abundant. More than half of the long bone remains (56.8%) could not be identified. At the stratigraphic level, there is considerable variability in the number of long bone remains, but there is a strong positive correlation (ρ = 0.774, p = 0.001; τ = 0.641, p = 0.001) between the number of shafts and epiphyses throughout the sequence.

Fragmentation was also analyzed for phalanges and mandibles (Table 3). A total of 79 ungulate phalanges were recorded, with first phalanges being the most abundant (50.6%). Of these, 77% are fractured, and 6.3% are longitudinally fractured, primarily first phalanges. Although the index of longitudinally fractured phalanges suggests similarities between first and third phalanges, complete phalanges account for 16.4%, with third phalanges being the most common. The taxa with the highest incidence of longitudinally fractured phalanges are the red deer, BB, and the horse. As for mandibles, the NR is slightly higher than that of phalanges. All mandibles are fractured, and of these, 39.4% are longitudinally fractured, significantly raising the longitudinal fracture index (64.9%). Like the phalanges, the taxa from Group 1 show the highest proportion of this fracture type. At the stratigraphic level, they exhibit the same variability as the other indices.

Regarding skeletal preservation, there is a marked bias against the axial skeleton, basipodia, and acropodia. To a lesser extent, but still with significant bias, the girdles and even the metapodia are affected. In contrast, the regions with the highest survival are the stylopodia, zeugopodia, and cranial skeleton. Long bones are the elements that have been best preserved, particularly the diaphyses. The relationship between diaphyses and epiphyses shows a considerable difference, with a significant bias against epiphyses, especially the distal ones. Differential preservation is evident, but it is not related to bone density and therefore not to post-depositional processes. However, there are other significant taphonomic factors, such as fire, that have undoubtedly contributed to the differential preservation of the assemblage (Solano García, 2024).

4.3 Anthropogenic and carnivore modifications

The anatomical regions with the highest frequency of cut marks in the assemblage are the axial skeleton and the stylopodia, followed by the zeugopodia and girdles. Cut marks on metapodia and acropodia are present but less frequent, and are almost absent on basipodia. The distribution of cut marks and their various attributes on the represented elements are very similar across all stratigraphic units. Virtually the entire butchery processing sequence is present in all stratigraphic units, except for periosteum scraping, which shows greater variability.

Intentional fracturing evidence is present across all units and species, but occurs most frequently in Group 1. Throughout the sequence, the predominant fracture profiles are longitudinal, with a prevalence of pointed and oblique types. These are followed by spiral and pointed spiral fractures. The predominant fracture angle at all levels is right, except in level IX, where acute angles prevail. Acute angles are the second most common in all units, while mixed angles are less frequent (Solano García, 2024).

The proportion of burnt remains throughout the J/K profile is remarkably high (82.51; Table 4). The analysis of their distribution along the sequence reveals a clear difference between Complex III ( = 82.3%, σ = 10.3%) and Complexes II ( = 96%, σ = 3.3%) and I ( = 96.1%, σ = 3%), which share the same proportion. Therefore, from Level XIII onwards, an increase in thermally altered elements is observed, persisting up to the top of the sequence.

Table 4

| Level | Cutmarks | % | Percussion | % | Green fractures | % | Burnt | % | C. toothmarks | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | 3 | 6.5 | 1 | 2.2 | 5 | 10.9 | 42 | 95.5 | 1 | 2.2 |

| V* | 2 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | 170 | 99.4 | ||

| VI | 2 | 4.5 | 4 | 9.1 | 40 | 97.6 | 1 | 2.3 | ||

| VII | 25 | 15.3 | 5 | 3.1 | 25 | 15.3 | 154 | 91.7 | 3 | 1.8 |

| VIII | 8 | 10.1 | 8 | 10.1 | 75 | 93.8 | 1 | 1.3 | ||

| IX | 75 | 11.7 | 11 | 1.7 | 152 | 23.7 | 625 | 92.0 | 5 | 0.8 |

| X | 31 | 8.1 | 7 | 1.8 | 55 | 14.4 | 368 | 98.4 | 5 | 1.3 |

| XI | 13 | 3.2 | 8 | 2.0 | 31 | 7.6 | 400 | 98.8 | 2 | 0.5 |

| XII | 19 | 9.2 | 2 | 1.0 | 18 | 8.7 | 196 | 97.5 | 4 | 1.9 |

| XIII | 24 | 5.6 | 3 | 0.7 | 45 | 10.6 | 358 | 94.2 | 2 | 0.5 |

| XIV | 4 | 2.7 | 2 | 1.4 | 12 | 8.1 | 119 | 81.5 | ||

| XV | 46 | 8.9 | 13 | 2.5 | 54 | 10.5 | 332 | 70.3 | 3 | 0.6 |

| XVI | 8 | 6.1 | 1 | 0.8 | 23 | 17.4 | 99 | 74.4 | 2 | 1.5 |

| XVII | 7 | 15.2 | 41 | 91.1 | ||||||

| Total | 260 | 7.6 | 54 | 1.6 | 440 | 12.9 | 3,019 | 82.5 | 29 | 0.8 |

| Cutmarks | % | Green fractures | % | Percussion | % | Toothmarks | % | Total | ||

| Taxa | ||||||||||

| BB | 20 | 15.2 | 43 | 19.8 | 3 | 12.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 66 | |

| Cervus | 27 | 20.5 | 40 | 18.4 | 6 | 24.0 | 5 | 50.0 | 78 | |

| Dama | 3 | 2.3 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 6 | |

| Equus | 76 | 57.6 | 128 | 59.0 | 15 | 60.0 | 3 | 30.0 | 222 | |

| Stephanorhinus | 4 | 3.0 | 4 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 8 | |

| Sus | 2 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | |

| Total | 132 | 217 | 25 | 10 | 384 | |||||

| Element | ||||||||||

| Axial | 24 | 18.2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 26 | |

| Flat bone | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Girdles | 14 | 10.6 | 4 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 20 | 20 | |

| Long bone | 79 | 59.8 | 196 | 90.3 | 23 | 92 | 5 | 50 | 303 | |

| Mandible | 9 | 6.8 | 4 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | |

| Phalanx | 3 | 2.3 | 8 | 3.7 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 10 | 14 | |

| Short bones | 2 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| Skull | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 3 | |

| Total | 132 | 217 | 25 | 10 | 384 | |||||

Cross tables of surface bone modifications by stratigraphic levels, taxa, and anatomical categories.

Percentages for the stratigraphic levels were calculated using the total NR without teeth from the layer.

In this analysis, all bone remains showing cut marks, green fractures, percussion marks, and evidence of burning were recorded (Table 4). Additionally, remains with carnivore tooth marks were included as complementary information. From this count, we observe that 7.62% of the remains bear cut marks, 12.9% show green fractures, 1.58% display percussion marks, and 82.5% of the remains exhibit evidence of fire. Carnivore tooth marks were recorded at a relatively low rate (0.79%) across the entire J/K assemblage. At the stratigraphic level, as in previous analyses, there is variability in the number of remains with anthropogenic modifications per level, due to the density of remains per excavated surface. However, there is a strong correlation between the various types of modification and the total number of remains without teeth for each stratigraphic level (cutmarks: ρ = 0.877, p < 0.01; percussion: ρ = 0.822, p = 0.002; burnt: ρ = 0.972, p < 0.01; fractures: rs = 0.832, p < 0.01), except for the few carnivore tooth marks (rs = 0.557, p < 0.06). Therefore, the results are consistent and proportional throughout the stratigraphic sequence. In other words, where there is a higher number of remains, it is reasonable to expect a higher number of anthropogenic modifications. Thus, given that the highest number of elements is found in the central levels, it is also here where the greatest number of modifications is located.

Nearly 90% of the remains are burnt, with greater representation in levels XVII–X and level IX. There is no preferential burning pattern by taxon, as around 90% of their remains also show signs of burning. However, this is not the case for the rest of the surface modifications. As expected, the taxa from Group 1 show the highest incidence of anthropogenic modifications. When we analyse the relationship between the six main taxa and cut marks, percussion marks, fractures, and carnivore tooth marks, there is a statistically significant association (X2 = 25.124, df = 15, p = 0.04831), given the strong association within Group 1 (Figure 9A). In fact, Cervus and Equus show a strong association with cut marks and fractures, while BB is more associated with fracturing (19.8%). The red deer has a stronger relationship with percussion (24%), cut marks (20.5%), and fracturing (18.4%). The horse shows an almost equal association (~60%) with percussion, fracturing, and cut marks. Interestingly, fallow deer shows a low incidence of inflicted modifications, distancing it from the main group, while the rhinoceros shows some association primarily with fractures. In the case of the wild boar, with only two recorded cut marks and one percussion mark, it stands out as an atypical species within the assemblage. Carnivore activity is mostly associated with Cervus (50%) and Equus (30%).

Figure 9

Graphical output of the correspondence analysis based on surface bone modifications between the main taxa (A) and elements categories (B). The ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals for taxa (blue) and modifications (red).

Anatomical categories show a strong association with surface modifications (X2 = 92.0623, df = 21, p = 7.0971e-11). Long bones are highly associated with percussion activities (92%), fracturing (90.3%), and cut marks (59.8%), while axial elements (18.2%), girdles (10.6%), and mandibles (6.8%) are primarily associated with cut marks (Figure 9B). Phalanges show a stronger correlation with percussion (8%) and fractures (3.7%) than with other modifications. Finally, cranial elements are distanced from the main group, with a low connection to cut marks (0.8%) and fractures (0.5%). Carnivore tooth marks are predominantly associated with long bones (50%) and girdles (20%) from red deer and horse.

In summary, the presence of the three main species throughout the sequence reflects the exploitation of meat, marrow, and fat, as indicated by the fracturing and its correlation with utility indices, and the systematic distribution of predominant cut marks on ribs and long bone diaphyses (Solano García, 2024).

5 Discussion

The sample from the J/K profile that we analyzed shows a significant bias, as previously mentioned, in terms of the number of remains in units IV, V, VI, and XVII, due to the smaller volume of excavated surface. Nevertheless, the results appear to be consistent with the analyses conducted. This allows us to make the first diachronic approximation regarding ungulate exploitation at Cueva del Ángel. Initially, we operate under the premise that we are dealing with a residential site (Binford, 1980, 1983; Kuhn and Stiner, 2019) where various activities were carried out, including flint knapping, bone retouchers, intensive use of fire, and different butchering activities, with a very low frequency of carnivore activity (Barroso Ruíz et al., 2011; Solano García, 2024).

The origin of the accumulation is clearly anthropogenic (Solano García, 2024), considering the high proportion of burnt remains (between 80 and 90%), the intensity of fragmentation (Tables 2, 3), where 98.6% of the remains are fragmented with average lengths around 5 cm, and the surface modifications (Table 4). However, carnivores are present throughout the sequence, and along with bite marks, they may suggest various interaction scenarios (Brain, 1981; Stiner, 2002, 2004a, 2012; Blasco and Rosell, 2009; Rosell and Blasco, 2009; Rosell et al., 2010; Yravedra, 2010; Enloe, 2012; Dusseldorp, 2013; Saladié et al., 2014; Camarós et al., 2016, 2017; Sauqué and Sanchis, 2017; Arilla et al., 2020). Nonetheless, the low overall herbivore-carnivore ratio (4.89) and the low occurrence of bite marks (0.79%) (Klein and Cruz Uribe, 1984), together with the absence of digested remains or coprolites, suggest that carnivores played a very secondary and opportunistic role as accumulators or modifiers (Blumenschine, 1995; Capaldo, 1998; Marean et al., 2000; Pickering, 2002). However, without completely ruling out carnivore activity, recent research over the last decade suggests that in the Middle Paleolithic, carnivores may have played a different role as a resource source and were possibly exploited (Tagliacozzo et al., 2013; Gabucio et al., 2014; Gómez-Olivencia et al., 2018; Val et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2021; Mata-González et al., 2023; Russo et al., 2023; Verheijen et al., 2023). In Cueva del Ángel, bears, wolves, and lynxes are recurrently present throughout the sequence, like ungulates, but with relatively few remains so far. In fact, most of the carnivore remains are burned. However, in Level XIII, followed by Level XI, there is a slight increase in carnivore remains, although with very low activity in both levels (<0.5%). The highest carnivore activity, albeit always at low rates, seems to occur from Level VII onwards. For now, until the detailed taphonomic histories of all levels are known, a very oportunistic and sporadic role has been proposed for carnivores as potential scavengers-prowlers exploiting the waste from human activities in Units XVII, XVI, XIII, IX, and VII (Solano García, 2024) or perhaps an incipient synanthropic behavior (Baumann, 2023) and/or consequences arising from the use of fire.

The use of fire is well-documented throughout the site's stratigraphic sequence. Although hearth structures have not yet been delineated, preliminary sedimentological and micromorphological studies indicate their presence (Monge et al., 2020). Its use appears to be a consistent feature throughout all occupations of the Cueva del Ángel. The fact that around 90% of the recovered bone remains exhibit thermal alterations, as well as a third of the lithic industry, highlights the importance of fire as a central element in the lives of these human groups at the site. This high concentration of burned remains is uncommon in Middle Pleistocene sites (Roebroeks and Villa, 2011). In other sites with burned bone remains of similar chronologies, such as Orgnac-3, Terra Amata, Lazaret, and Payre (Moigne and Barsky, 1999; Moncel and Patou-Mathis, 2005; Valensi et al., 2005), the proportion does not exceed half of the sample. Even in records with hearths and controlled use of fire, like Hayonim Cave or Kebara (Speth and Tchernov, 2001; Stiner et al., 2001), the frequency of burned remains is low. Few sites, such as Qesem Cave (Blasco et al., 2014; Barkai et al., 2017) or Bolomor XI, IV (Blasco et al., 2013), have more than 50% of burned remains. Generally, sites with a high frequency of burned remains are found in the Upper Pleistocene, for example: Pech de l'Azé IV (~57%) (Dibble et al., 2009); La Quina 8–6 (~95%) (Debénath et al., 1998); Krems-Wachtberg (90–98%) (Fladerer et al., 2012); and levels 15–30 of Esquilleu (88–99%) (Yravedra and Uzquiano, 2013). In Cueva del Ángel, the identified colors, compared with experimental studies (Lebon et al., 2008), suggest medium exposures between 200 and 400°C, although some remains show evidence of having reached temperatures of 700°C. These temperatures are typical for roasting meat (Shipman et al., 1984; Buikstra and Swegle, 1989); however, we cannot rule out other culinary or mechanical activities related to fat and bone respectively. Additionally, the presence of hundreds of small burned fragments (<2 cm) may suggest other uses of bone, such as fuel (Costamagno et al., 2009, 2010), or their disposal during cleaning activities (For in-depth discussion see, Solano García, 2024).

This study focuses on the six recurring ungulate taxa found in the fossil assemblage: Bos/Bison, Cervus, Dama, Equus, Sus, and Rhino. Although the elephant is present in three levels (VII, XII, XVII) and the ibex only in one (XVII), their representation so far is minimal, with only one remain per level. Among these taxa, the dominant species based on MNI are the horse (28.5%), BB, and red deer (19 and 17.5%, respectively). If the BB group were separated, the red deer would be the second most represented species. In fact, the taxa with the highest anatomical representation are the horse and red deer, followed by BB, fallow deer, rhinoceros, and wild boar. However, across the entire assemblage, there are more wild boar individuals (14.6%) than rhinoceros (9.5%) and fallow deer (8%). Regarding age at death, around 75% are adults, indicating an adult-dominant mortality profile (Stiner, 1990), consistent with hunting activities (Gaudzinski and Roebroeks, 2000) and the procurement of larger amounts of resources.

From the statistical analysis of the various indices, we have been able to differentiate two groups with similar patterns throughout the entire sequence. Group 1 (Equus, Cervus, BB) is the best anatomically represented and has the highest survival index. Its anatomical configuration, fragmentation, and surface modifications are very similar, thus reflecting the same exploitation processes. The higher proportion of long bones, followed by cranial and girdle remains, indicates a selection and preference for the parts richest in meat and bone marrow. This is further supported by the location of the anthropogenic modifications, although BB and Rhino seem to show a pattern more oriented toward fracturing and marrow extraction, consistent with the utility indices calculated by Solano García (2024). Group 2 (Dama, Sus, Rhino) also shows a similar distribution among its members, although Dama closely approaches the configuration of Group 1, as its skeletal survival is more similar to that of BB, while Sus shows a very different anatomical representation compared to the others. On the other hand, the data on Rhino indicate activities related to butchering and marrow extraction. Overall, the species in Group 2, though less abundant, are always present throughout the sequence. Therefore, they likely represent a supplementary exploitation group, where Rhino and fallow deer could provide additional protein and fat to the diet. However, the anatomical representation of wild boar presents an outlier in the exploitation pattern for diet, possibly indicating the use of wild boar for other resources.