Abstract

The phenomenon of pucaras has been studied from different perspectives in the South-Central Andes. These settlements, developed during the Late Intermediate Period, have mainly been explained as a consequence of the disintegration of Tiwanaku, linked to factors such as conflict and widespread warfare, as well as to climate change, particularly the control of water sources during periods of drought, often overlooking the social dynamics, tensions, and agreements of local communities. In the precordillera of the Atacama Desert, around AD 1200, a high-altitude architectural system emerged, aligning with this “pucara horizon” and associated with extensive agricultural and hydraulic infrastructure. These transformations created novel landscapes for habitation and cultivation in the steep Andean ravines, enabling new forms of social life and productive practices. Moving beyond classical perspectives, this study seeks to offer new insights into the Late Intermediate Period through the case of northern Chile, focusing on two pucaras and their associated productive spaces in the Mocha locality of the Tarapacá precordillera. Based on various lines of evidence, such as ceramic, zooarchaeological, archaeobotanical, stable isotope and stone tool analyses, along with spatial analysis of settlements and agricultural infrastructure, we describe the forms, strategies, and dynamics involved in the creation of this shared social and productive Andean landscape. Without disregarding the influence of climate change and conflict, both pucaras can be understood as dual social strategies for constructing the community's landscape and territory, evoking its internal cycles over time as well as its responses to external entities and the Inca expansion.

1 Introduction

The Late Intermediate Period or LIP (AD 900–1450) is a specific moment within the Late Prehistory of the South-Central Andes during which new forms of social organization emerged, transforming the patterns of preceding periods (Covey, 2008; Tarragó, 2001; Nielsen, 2001, 2002, 2007; Arkush, 2008; Arkush and Stanish, 2005; Arkush et al., 2024; Housse, 2024; Ruiz and Albeck, 1997). Traditionally, its emergence has been interpreted as a direct consequence of the disintegration of Tiwanaku, whose networks of political, economic, and ideological integration collapsed, reconfiguring the Andean sociopolitical landscape (Arkush et al., 2024).

The defining characteristics of the LIP have been outlined across various Andean regions. Among these, a particular development is the emergence of a previously unseen settlement pattern characterized by the pucaras, typically described as fortified sites situated on hillsides, at the heads of valleys, or in inaccessible areas, often near water sources (Ruiz and Albeck, 1997; Tarragó, 2001; Nielsen, 2002; Housse and Mouquet, 2023). Pucaras exhibit architectural patterns that include walled enclosures, public spaces, and spatial features associated with both defensive needs and the territorial control of strategic resources. Alongside the appearance of these settlements, there is evidence of intensified agricultural practices through the construction of large scale agro-hydraulic infrastructure, such as irrigation canals and terraces system, to sustain cultivation in steep environments. This infrastructure was not merely complementary but rather a fundamental component of these new social formations (Tarragó, 2001). Its importance is further supported by ethnographic accounts, which describe pucaras not only as defensive or residential spaces, but also as ritual and sacred landscapes (Ruiz and Albeck, 1997; Tarragó, 2001, 2011; Housse and Mouquet, 2023), upon which the success of agricultural production depended (Martínez, 1989). Certain explanations also refer to the logic of using all the available cultivable land and avoiding the risk of floods (Martínez, 1989; Rivolta et al., 2021; Urrutia, 2022; Housse, 2024).

Considering this framework, this study aims to propose new perspectives on the role of pucaras through the case of northern Chile, analyzing two pucaras and their associated social and productive spaces in the Mocha locality of the Tarapacá region. Drawing on multiple lines of evidence, including ceramic, zooarchaeological, archaeobotanical, and lithic analyses, isotope data, and spatial analyses of built landscapes and agro-hydraulic infrastructure, we examine the social strategies and dynamics that shaped these Andean socioproductive landscapes. In doing so, we critically compare our findings with traditional models of the LIP transformations in the Andes. We assess how this case fits or challenges established models, and how it can broaden archaeological understandings of the LIP social processes by offering a material and situated perspective from the margins of areas traditionally explored, such as the Atacama Desert in the South-Central Andes.

2 The archaeology of the Late Intermediate Period in the South-Central Andes

The developments of the LIP patterns around AD 900 have been interpreted as the crystallization of new social, economic, and territorial strategies, in which the control of productive spaces and resources played a central role (Arkush et al., 2024). To explain the emergence of these social formations, Andean archaeology has predominantly relied on two main, and often complementary, interpretive lines. The first emphasizes the role of conflict and warfare as drivers of social change (Nielsen, 2002, 2007; Arkush and Stanish, 2005; Arkush, 2010; Arkush and Tung, 2013; Arkush et al., 2024). According to this view, the collapse of Tiwanaku caused generalized instability, prompting the emergence of fortified settlements as adaptive responses to insecurity and war.

The second interpretation centers on environmental factors, particularly the impact of an arid phase and climatic fluctuations during the Medieval Climate Anomaly (ca. AD 950–1250), characterized by drought across Andean regions (Nielsen, 2001, 2002; Arnold et al., 2021; Arkush et al., 2024). The water scarcity would have reduced the availability of productive land, generating competition over access to water sources (Nielsen, 2002). Although the extent to which climate impacted the transformations of the LIP still requires more precise evaluation, Arkush et al. (2024) argue that climate volatility (Kennett and Marwan, 2015), probably led to disruptions such as social instability and migrations, reshaping settlement patterns, territorial organization, and subsistence strategies. Consequently, these works have portrayed the LIP in the South-Central Andes as a turbulent period favored by climatic changes, migration and violent conflict, warfare, disorder or mayhem (Langlie and Arkush, 2015; Arkush et al., 2024; Nielsen, 2007).

Authors such as Nielsen (2007) have proposed that the LIP was marked by a persistent “state of insecurity” that prompted communities to organize around defense and warfare, resulting in what Arkush (2017) has termed “defensive coalescence.” Revisiting the concept of coalescence proposed by Kowalewski (2013), Arkush (2017) defines it as a phenomenon characterized by the formation of big settlements in crisis periods, following the collapse of a previous social form. She reinterprets it as an analytical tool for examining processes of community formation, understanding such settlements not as consolidated communities, but as “social experiments sometimes conducted under severe external pressure” (Arkush, 2017; p. 2).

While these approaches have been central to understanding warfare from anthropological perspectives (Arkush and Stanish, 2005), relying exclusively on explanations grounded in warfare and resource competition limits our understanding of the Andean processes of social change (Pacheco et al., 2016), and encourages viewing these transformations as inherently turbulent (Arkush et al., 2024) or as mayhem (Langlie and Arkush, 2015). We argue that such perspectives reproduce an interpretative pattern in which warfare is idealized as the universal driver of social and political transformations (Carneiro, 1992; Arkush and Stanish, 2005).

While not dismissing the role of conflict, violence, competition, or climatic change, we propose broadening the analysis. We consider that such transformations may have been experienced and negotiated through quotidian and internal dynamics, not exclusively as the outcome of armed conflict, insecurity, or prolonged hostilities, but rather within the cycles and relational modes proper to Andean societies. Although we recognize the contributions of these interpretations, we argue that they tend to privilege external factors, armed conflict or environmental stress (“external pressures”), as primary drivers of change, relegating the internal dynamics of Andean communities (Platt, 1988; Albarracín-Jordán, 1996). This emphasis limits our capacity to understand the forms of agency, creativity, innovation, and transformation generated from within by the social groups involved. It is, hence, essential to contrast these approaches with empirical cases that problematize these assumptions and expand the interpretive possibilities of Andean pasts.

We re-evaluate these processes from a perspective that places greater emphasis on local trajectories and on the collective negotiations, tensions, and the order and chaos in the Andes (Arnold and Yapita, 2000). Such an approach can shed light on processes characteristic of the LIP, like the developments of pucaras and the land use through agricultural practices in new settings, including steep terrains that people chose to inhabit around AD 1200 in various subregions of the South-Central Andes.

3 Late Intermediate Period in Tarapacá: Pica-Tarapacá Cultural Complex

In the South-Central Andes, archaeological evidence has led researchers to interpret socio-cultural LIP transformations through a different perspective. This suggests a model that, while acknowledging the impact of climate and conflict, highlights internal tensions and long-term local processes as key drivers of change. This is the case of the Tarapacá region, where classical models for the LIP do not fit well, and the transformations seem to reflect rather internal social and political dynamics (Uribe, 2006).

The Tarapacá region, located in northern Chile in the hyper-arid core of the Atacama Desert (Figure 1), represents a particular case within broader periodization's proposed for the South-Central Andes, and especially with respect to northern Chile. Archaeological research in Tarapacá has demonstrated that the new social formations emerging around AD 900 did not arise from the decline of Tiwanaku influence, a process that seems to have taken place in neighboring areas such as Arica and San Pedro de Atacama (Uribe, 2006).

Figure 1

Regional setting during the Late Intermediate Period in the precordillera of Tarapacá, showing the main archaeological sites mentioned in the text.

While the presence of Tiwanaku influence in Tarapacá was originally proposed (Núñez, 1976, 1984; Núñez and Dillehay, 1995), this hypothesis was based on minimal and scarcely contextualized evidence, which failed to consider the social background of an extensive Formative Period (900 BC – AD 900), that developed in the Pampa del Tamarugal, at the foot of the Tarapacá highlands (Uribe et al., 2020a).

The Formative Period seems to have had a distinctively local emphasis, shaped by internal transformations rooted in the ancestral trajectories of the populations inhabiting the region (Uribe et al., 2020a). For this reason, there is consensus that the Middle Horizon is absent in Tarapacá (Uribe, 2006; Muñoz et al., 2016; Agüero and Uribe, 2018). Tarapacá is positioned as a singular case where social development transitioned directly from a long local Formative period into the LIP. Then, social change is not explained by the collapse of an external system, but rather by a social configuration resulting from processes of inequality and intense interactions between human groups and a changing landscape that included the Pampa del Tamarugal and its surroundings (Uribe, 2006; Uribe et al., 2020a).

These interactions were structured around extensive agricultural practices that began in the pampa ca. 400 to 260 BC (Vidal-Elgueta et al., 2024), associated with Early Formative villages, later condensed in one of them, Caserones, which constituted a direct precedent for the articulation between domestic and agricultural spaces that later shifted toward the highlands (Uribe, 2006). After nearly two millennia of Formative developments in the pampa, the societies of Tarapacá underwent transformations comparable to those associated with the LIP more broadly (Schiappacasse et al., 1989; Covey, 2008). All these practices contributed to the integration of the territory under shared cosmologies, though socially segmented groups, fully established in the inlands by around AD 1200 (Uribe, 2006). The defining feature of this period has been identified as the construction of hilltop settlements, known as pucaras, associated with extensive agricultural terrace systems distributed across the upper reaches of valleys from southern Peru to northern Chile (Schiappacasse et al., 1989; Moragas, 1991; Uribe et al., 2007; Housse, 2024).

Traditionally, these changes were interpreted as the result of the expansion of señoríos aymaras following the collapse of Tiwanaku (Núñez, 1984; Núñez and Dillehay, 1995; Schiappacasse et al., 1989). This expansion aimed to control as many ecological zones as possible through caravan trade and the establishment of colonies (Núñez, 1984; Núñez and Dillehay, 1995), in line with the Andean “vertical control” model (Murra, 1972). This constituted the economic and social foundation of what was defined, based on ethnohistoric accounts, as the Pica-Tarapacá Cultural Complex (Núñez, 1984), a single and harmonious social system that established enclaves in the altiplano, precordillera, and coast to access key resources, articulated by caravan traffic (Núñez and Dillehay, 1995).

However, recent studies have led to a less idealized understanding of these processes. Without denying the existence of contacts and interactions with other regions, contemporary approaches recognize the agency of local populations in generating their own sociohistorical trajectories and interaction networks (Uribe, 2006). Rather than attributing observed changes to a colonization process by señoríos, current interpretations emphasize the dynamics of segmentary societies that originated from a persistent Formative base (Albarracín-Jordán, 1996; Uribe, 2006). In this view, the Pica-Tarapacá Complex is redefined as an expression of heterogeneity and social segmentation, where groups with different productive and social organizational logics coexisted in a region integrated by autonomous yet interconnected relationships across ecological zones and regions (Uribe, 2006). Recent isotopic studies have further supported these propositions, indicating that mobility patterns during the LIP were not limited to caravans crossing the desert for exchange or to the imposition of colonies. Instead, mobility appears to have been diverse, occurring at various moments throughout an individual's life and likely shaped by kinship ties or political alliances (Santana-Sagredo et al., 2019).

The discussion of the LIP processes in Tarapacá has been framed in a two-phase periodization (Uribe et al., 2007). Firstly, the Tarapacá Phase (AD 900–1250) is associated with the terminal occupation of the Late Formative village of Caserones situated in the pampa (lowlands). This site likely served as the base for the initial LIP trajectories, generated through an intensification of village-urban life and extensive agriculture. However, the tensions inherent to communal life appear to have produced increasing inequalities and internal fragmentation within this highly centralized Formative society (Uribe, 2006, 2008). As a result, Caserones was gradually abandoned around AD 1000, marking the beginning of the Tarapacá Phase and giving rise to a diversification of settlements between the coast, pampa and the precordillera. These included the Pica 8 cemetery in the Pica Oasis (between pampa and precordillera), consistently dated between cal AD 993 and 1414 (Santana-Sagredo et al., 2017), as well as sites in the precordillera such as Camiña 1 (cal AD 1020–1210), Jamajuga (cal AD 1160–1310), and Nama (cal AD 1160–1290), among others (Uribe et al., 2007). These precordillera sites reveal an early LIP configuration characterized by the appearance of conglomerated settlements and agro-hydraulic infrastructure. By AD 1250, during the Camiña Phase, populations consolidated their settlements in the upper sections of the ravines, while simultaneously intensifying interactions with neighboring regions such as the Altiplano, Arica, and Atacama (Uribe et al., 2017; Mendez-Quiros et al., 2023). This shift marked the consolidation of pucaras and agricultural terraces throughout the precordillera of Tarapacá (Moragas, 1991; Uribe, 2006; Muñoz et al., 2016).

These social formations constituted the local bases upon which the Inca exercised its influence around AD 1450, probably relocating populations and productive practices into administrative centers such as Tarapacá Viejo, located in the lower part of the Tarapacá ravine (Urbina et al., 2019). This site became the principal administrative center of the Tawantinsuyu in Tarapacá and was connected to one of the main branches of the Qhapaq Ñan that crossed the pampa (Uribe et al., 2012; Zori and Urbina, 2014; Urbina et al., 2019), although the processes of Inca expansion in the region remain subjects of debate.

Building on that insight, pucaras, together with its social and productive landscape, have been placed as a hallmark for understanding the social, economic, and political life of the LIP and late prehistory in northern Chile. Nevertheless, research on them has remained scarce (Moragas, 1991; Uribe et al., 2007, 2017; Adán et al., 2007; Urrutia and Uribe, 2020). What is clear is that, beyond their potential defensive or strategic functions, pucaras should be understood as long-term and persistent material expressions of local communities in response to both external and internal dynamics related to settlement, production, conflict, territorialization, and social reproduction.

We propose that studying these sites offers a valuable perspective for tracing the specific trajectories of particular social groups as they experienced broader processes of transformation. The material and archaeological analysis of two pucaras from the Mocha locality (Tarapacá ravine) constitutes an opportunity for rethinking the social dynamics of the LIP from a situated perspective, acknowledging the historicity and agency of the Andean communities who inhabited the Tarapacá precordillera in the Atacama Desert.

4 Locality and case study

The study area is located in the Tarapacá Region, northern Chile, situated south of Peru and west of Bolivia. Today, it is characterized by the scarcity of water sources, which depend on precipitation in the Andean highlands eastwards (Houston, 2006). The specific geomorphological setting of our study is the precordillera (above 2,000 masl), a zone marked by rugged mountain slopes and deep, steep ravines that descend westward from the highlands. These ravines discharge into the Pampa del Tamarugal through water flows that are seasonally activated by summer rainfall in the highlands and precordillera (Sepúlveda et al., 2014). Our research focuses on the Tarapacá ravine, a corridor that connects the highlands and the pampa, enabling broad-scale interactions across ecological zones.

We conducted archaeological investigations at the Pariqollo and Kuico pucaras, two settlements situated in the middle basin of the Tarapacá ravine within the precordillera, in the locality of Mocha (Figure 2). They share similarities with other pucaras documented in the precordillera, such as Camiña, Nama, Chusmiza, Carora, and Jamajuga (Uribe et al., 2007, 2017; Adán et al., 2007; Urbina et al., 2018), as well as in the Altiplano, such as Pukar Qollu and El Tojo (Sanhueza, 1981; Niemeyer, 1962). Pariqollo was previously studied by Moragas (1991), who conducted surface characterizations and limited excavations, whereas Kuico has not been archaeologically investigated.

Figure 2

Locality of Mocha, precordillera of Tarapacá, showing the two pucaras (Pariqollo and Kuico) studied, situated in the Tarapacá Ravine along the main rivers. Areas in green indicate agro-hydraulic and artificial conditioning for agriculture.

Pariqollo, also known as Mocha-1 (Moragas, 1991), is located west of the village of Mocha, on a distinctively red-colored hill flanked by two secondary ravines, at an elevation of approximately 2,170 masl. In contrast, the pucara of Kuico lies on the southern side of the ravine, across from Pariqollo, and is located at a higher elevation of around 2,350 masl. At the same time, we analyzed eight human individuals for stable isotope analysis from the Mocha-2 cemetery, located next to Pariqollo (Standen and Sanhueza, 1984; Moragas, 1991).

Moragas (1991) discusses the evidence of the cemetery of this pucara, Mocha-2, where 21 individuals were buried (Standen and Sanhueza, 1984). Bioanthropological analyses were conducted, including the study of skeletal pathologies, dental observations, and intentional cranial modifications. The results related to traumatic pathologies are open to debate, as only one individual shows signs of violence, suggesting that physical violence was not a common feature in this population. Additionally, dental anthropological analysis suggested that the diet consisted of processed and cooked foods (Standen and Sanhueza, 1984). We will further explore these conclusions through isotopic analysis of some of the individuals buried at Mocha-2.

Early studies of Mocha-1 (currently known as Pariqollo) and its cemetery (Mocha-2), already pointed to the role of local populations as active agents in these social transformations (Moragas, 1991). A radiocarbon date from hearth remains, found in association with local ceramics and maize cobs, indicates an occupation around AD 1230 (Moragas, 1991). The abundant presence of local ceramics and the scarce but recurring presence of non-local wares, as well as remains of fish and marine shells, permitted to suggest the role of local populations in these social processes. Then, portraying them as groups interacting not only with nearby valleys and oases, but also with more distant places such as the coast and the highlands (Moragas, 1991). The present research deepens previous conclusions through new excavations at Pariqollo and initiates archaeological work at Kuico.

5 Materials and methods

A methodological strategy was implemented combining high-resolution aerial and photogrammetric recording with controlled stratigraphic excavations in both Pariqollo and Kuico pucaras, complemented with analyses of the recovered archaeological materials. Below, we describe the technical procedures used during fieldwork and laboratory analysis.

Surface recording of the settlements was carried out through photogrammetric surveys using a DJI Mavic 3 drone. Based on the aerial images obtained, orthomosaics and digital elevation models (DEM) were generated using Agisoft Metashape software, allowing for precise documentation of the terrain and spatial distribution of the settlements. These procedures facilitated the identification of architectural units, artificial terraces, topographic features, and activity areas. These elements were quantified and measured. On this basis, a surface survey was conducted to document and identify areas with greater archaeological and stratigraphic potential, prioritizing those associated with architectural structures and evidence of sediment accumulation.

Based on this evaluation, excavation areas were selected. A total of 17 excavation units of 1 m2 were excavated across various sectors of the two settlements. Specifically, eight excavation units were conducted at Pariqollo and nine units at Kuico. The primary goals of the excavations were to document both cultural and natural stratigraphy, characterizing each stratigraphic unit based on attributes such as compaction, texture, color, and composition, as well as the presence of cultural materials (artifacts and ecofacts), and their contextual relationships. The excavations were carried out with systematic recording of levels, profiles, and planimetric data.

Organic samples were selected for radiocarbon dating including maize cob, squash skin, charcoal and an unidentified terrestrial plant. Samples were pretreated (following the ABA protocol) and graphitized at the Geochronology Laboratory of the University of Magallanes. Graphite samples were dated at the KCCAMS Facility of University of California Irvine. Radiocarbon dates were calibrated using the SHCal20 curve (Hogg et al., 2020) in the OxCal Program version 4.4 (Bronk Ramsey, 2009). Previously published radiocarbon dates (Moragas, 1991; Santana-Sagredo et al., 2021) were also re-calibrated using the SHCal20 curve (Hogg et al., 2020).

The ceramic analysis included typological, morphological, and functional characterization, aimed at understanding the production, use, distribution and circulation of these materials. Special attention was paid to the associations between ceramic types, consumption and behavioral patterns, and the functions of the excavated structures. The lithic analysis focused on raw material identification, technological and morphological characterization, and reconstruction of chaînes opératoires.

Study and identification of zooarchaeological material focused on taxonomic and skeletal parts identification, to represent human choices related to animals (Gifford-Gonzalez, 2018). Taxonomic identification was performed using a reference sample including Lama guanicoe and Lagidium viscacia in addition to the osteological manuals of Sierpe (2015) for Camelidae, and Reise (1973) for rodents. The incidence of taphonomic traces followed Behrensmeyer (1978), Haynes (1983), Binford (1981) and Mengoni (1999); and Camelidae age ranges were evaluated following Kaufmann (2009) and Kaufmann et al. (2017). Results were counted using the number of identified specimens or NISP and MNI or minimum number of individuals represented, considering each excavation as the unit of accounting.

Due to the high degree of alteration and the poor preservation of archaeobotanical remains, a general macroscopic taxonomic analysis was undertaken, focusing on the most morphologically diagnostic elements to establish their identification. However, the advanced state of degradation meant that most specimens could not be assigned to a specific taxonomic category.

Stable isotope analyses of carbon and nitrogen were carried out on bone collagen from eight individuals originally buried in Mocha-2 cemetery. Samples were taken at the Centro Experimental Canchones of the Universidad Arturo Prat. Sex and age estimation of the human individuals followed standards based on morphological attributes from skull and pelvis (Buikstra and Ubelaker, 1994; White and Folkens, 2005). Post-mortem broken bone samples were taken to avoid major destruction on the skeleton remains, weighing around 1 gram. Bone collagen extraction was carried out at the UASIF (University of Antofagasta Isotope Facility), following a modified protocol of Longin (1971). Stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes were measured using an Elementar vario PYRO cube elemental analyser (EA) coupled to an Elementar Isoprime precisION isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS). International standards USGS-40 and USGS-41 were used for calibration, and analytical errors for δ13C and δ15N were of ±0.05% and ±0.1%, respectively.

6 Results

6.1 Spatial analysis

The pucara of Pariqollo is located on the north side of the Tarapacá Ravine at an intermediate elevation (2,170 masl), covering approximately 5.2 ha, with around 260 artificial terraces and structures distributed along the slopes of the hill and secondary ravines (Figure 3). The average surface area of these elements is 10.8 ± 8.6 m2, indicating considerable diversity in their sizes and reflecting a wide variety of morphologies, ranging from elongated and quadrangular to circular and irregular layouts. In general, they range from 1 to 46 m2, with a single element of nearly 100 m2 associated with a later Republican-period mining platform. The summed built surface amounts to approximately 2,830 m2.

Figure 3

General layout of activity areas in Pariqollo.

Visible surface architecture is limited to highly altered wall foundations, likely due to the removal of stone masonry or the use of perishable materials. These features consist of artificial terraces intended for domestic and productive activities, conditioned with simple retaining walls for containment and leveling, while also serving to separate spaces. Larger enclosures are found at the summit, mostly open spaces created by clearing, although still bounded by wall foundations. Many of these terraces were formed by cutting into the slope and constructing retaining walls, suggesting conditioning for a prolonged period of habitation. Smaller but elongated artificial terraces were also identified mainly in the slopes of secondary ravines, probably corresponding to agricultural terraces, while at the foot of the hill, larger and isolated enclosures were recorded, likely functioning as corrals. The pucara and its surroundings are crossed by numerous circulation paths and trails.

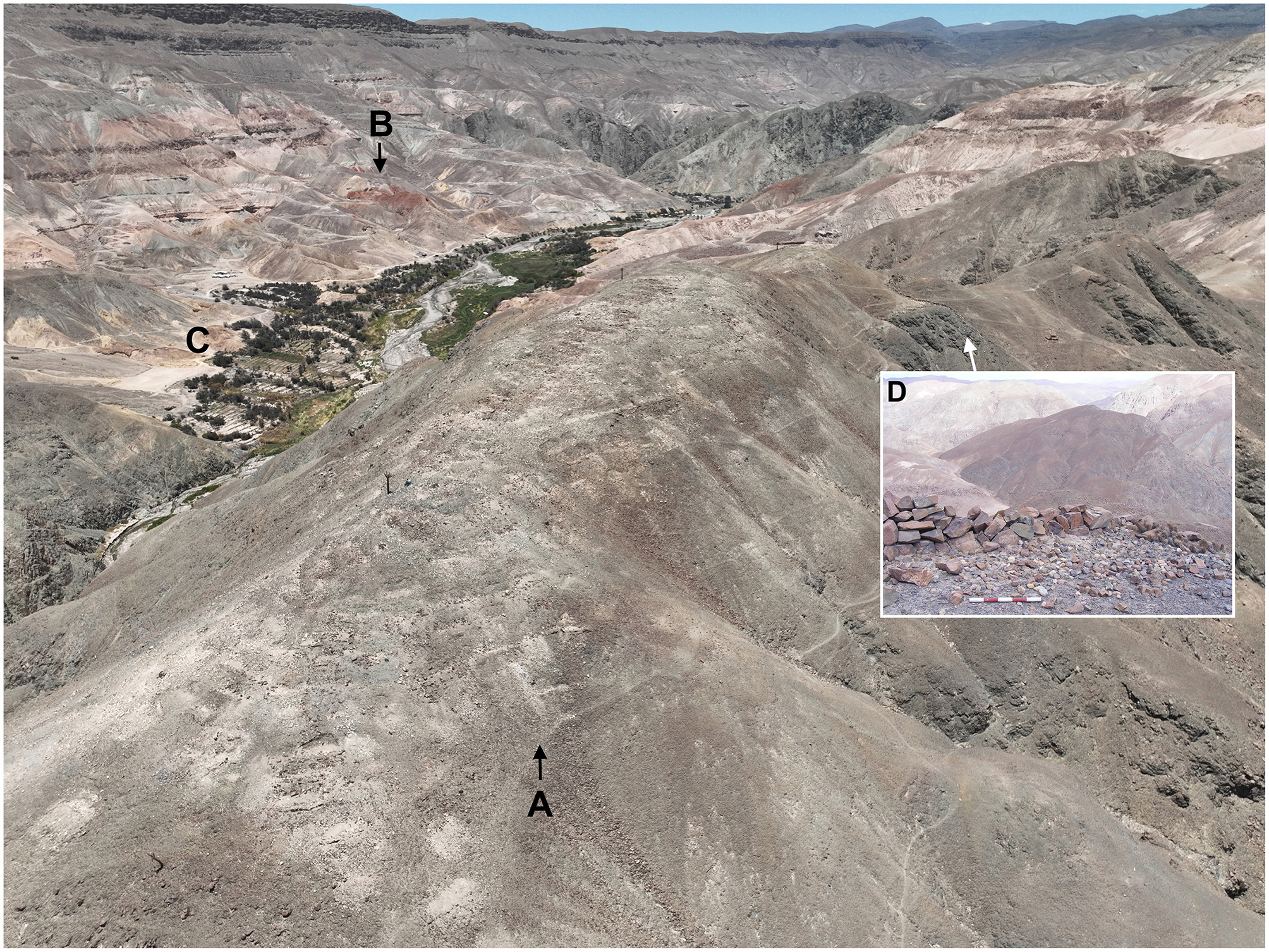

The pucara of Kuico is located on the southern side of the Tarapacá Ravine, but at a higher elevation, facing Pariqollo. It is considerably larger, encompassing two main sectors. One situated on the summit of the principal hill and another descending toward the ravine. The site covers approximately 16 ha and contains around 790 artificial terraces distributed along the slopes, ranging from 1 to 34 m2 (Figure 4). The mean surface area of these structures is 4 ± 3.8 m2, suggesting a lower variability in size compared to Pariqollo, although the diversity in morphologies is similar. Certain areas display more standardized layouts, particularly in the central zone of the upper sector, where clusters of quadrangular and rectangular structures are associated with larger open spaces measuring around 20 to 30 m2. By contrast, the peripheral zones are dominated by smaller, elongated terraces that adapt to the irregular topography of the slopes. Overall, the total conditioned and/or built surface area amounts to approximately 3,800 m2. Distinct from Pariqollo, Kuico also incorporates discontinuous stone walls along its eastern side, extending to the northeast and regulating circulation by marking the entrance, where an accumulation of rounded stones was identified.

Figure 4

Kuico general layout. (A) Activity areas at Kuico. (B) Upper sector. (C) Lower sector. (D) Discontinuous stone walls at the access.

6.2 Stratigraphic and chronology analysis

The stratigraphy documented in both pucaras reveals differences in the intensity and nature of their deposits. At Pariqollo, the sequence is denser and more prolonged, comprising multiple layers with recurrent occupations, combustion features, and a greater diversity of materials. In contrast, Kuico exhibits a more ephemeral occupation, characterized by simpler and shallower stratigraphies composed of one or two levels overlain by aeolian post-occupational fills resting above the bedrock.

The eight excavated units at Pariqollo were located on artificial terraces of varying sizes, ranging from larger open areas at the center of the settlement to smaller structures situated along the slopes of the pucara. Between four and six stratigraphic layers were recorded in these units, with excavation depths ranging from 11 to 74 cm. The uppermost strata associate with post-occupational aeolian deposits. Beneath these, intermediate levels reveal occupational surfaces containing primary domestic refuse, frequently affected by cleaning activities. These surfaces often exhibit combustion features, likely in situ hearths or cleaned-out fire pits, as well as fill and leveling layers used to create artificial terraces.

Evidence of different activities was found on these prepared surfaces, which represent palimpsests of domestic refuse, combustion events, and camelid and rodent coprolites, repeatedly disturbed by trampling and intensive use. Small fragments of crushed copper mineral were recovered from several units, and a shell bead was found in one of them. Overall, the lowermost layer in every unit represents the bedrock. Calibrated radiocarbon dates from Pariqollo range between cal AD 1290 and 1405, indicating a LIP occupation (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Calibrated radiocarbon dates for Pariqollo, Mocha 2, and Kuico. *Mocha 1 was the name originally given to Pariqollo by Moragas (1991). Calibration was carried out using the SHCal20 curve (Hogg et al., 2020) in the OxCal Program version 4.4 (Bronk Ramsey, 2009).

At Kuico, the eight excavation units reached shallower depths, ranging from 6 to 54 cm. The upper strata are dominated by aeolian deposits associated with abandonment and post-occupational fills, often extending down to 30–40 cm. These layers generally form heterogeneous matrices, containing sparse primary refuse. Crushed copper mineral is present but less frequent than at Pariqollo, as are camelid coprolites. Occupational floors and refuse deposits are scarce, suggesting a more limited or short-term use of space compared to Pariqollo. Nevertheless, occasional signs of domestic use are present, such as ceramic fragments, faunal remains, and localized traces of combustion. The excavated areas mainly represent larger open spaces and medium-sized structures, with simple surface conditioning and traces of simple walls, probably serving public, domestic, and productive functions.

During the excavation of a unit at Kuico, on an artificial peripheral terrace associated with a domestic occupation, a secondary burial was identified containing the remains of at least three individuals. Preliminary results show that the burial contained one non-adult and two adults of different sexes. The male exhibited multiple osteoarticular lesions, affecting the hip, clavicle, and tibia, consistent with sustained biomechanical stress. This secondary burial was associated with a small stone shovel, a handstone, camelid remains, and red mineral pigment.

A ninth unit excavated at Kuico, an enclosed circular storage pit (troja), reached a depth of 145 cm. It contained over a meter of post-occupational aeolian fills with no cultural materials. The only occupational layer was identified at approximately 120 cm, where a deposit of local LIP ceramic fragments, primarily large storage jars, was recorded directly above the bedrock. Excavation revealed that the troja had been dug into the hill's geological base, with simple stone walls constructed on its upper section to align the feature with the surrounding surface.

Radiocarbon dates from Kuico range between cal AD 1420 and 1485, pointing to a slightly later and probably shorter occupation during the LIP and Late Period (Figure 5; Table 1).

Table 1

| Site | Sample | Lab code | 14C | Error | Calibrated date AD (95% probability) | Median AD | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pariqollo (Mocha 1) | Charcoal | Beta* - | 720 | 50 | 1230–1400 | 1,325 | Moragas, 1991 * Lab number was not published |

| Pariqollo | Maize cob | UCIAMS 284809 | 685 | 15 | 1290–1395 | 1,350 | This work |

| Pariqollo | Vegetal | UCIAMS 284810 | 640 | 15 | 1315–1405 | 1,340 | This work |

| Mocha 2 | Squash | OxA 39454 | 626 | 17 | 1320–1410 | 1,345 | Santana-Sagredo et al., 2021 |

| Kuico | Squash | UCIAMS 284804 | 510 | 15 | 1420–1455 | 1,440 | This work |

| Kuico | Charcoal | UCIAMS 284805 | 475 | 20 | 1425–1485 | 1,450 | This work |

Calibrated radiocarbon dates for the sites Pariqollo, Mocha-2, and Kuico.

Calibration was carried out using the SHCal20 curve (Hogg et al., 2020) in the OxCal Program version 4.4 (Bronk Ramsey, 2009). *Denotes that the lab code was not published in Moragas (1991).

6.3 Artifactual and ecofactual analyses

6.3.1 Pottery

A total of eight ceramic components were identified in the assemblages of both pucaras, including defined types and a residual category representing eroded materials (ERO) (Figure 6). For the LIP in Tarapacá, previous studies have described the local Pica-Tarapacá Complex ceramic types (Uribe et al., 2007). These are compressed in the Pica-Charcollo (PCH) vessels, used mainly for storage of water and preparation of fermented chicha, as well as Pica Gris Alisado (PGA) that functioned as cooking pots. The production of these ceramic types can be traced back to the last moments of the Late Formative Period, around AD 700 (Uribe et al., 2007; Uribe and Vidal, 2015).

Figure 6

Ceramic component frequencies at the pucaras of Pariqollo and Kuico.

In addition to these local wares, non-local LIP expressions were identified, particularly from the altiplano (ALT), typically represented by plates and serving bowls (pucos) made with volcanic red pastes and decorated with black paint. Other foreign styles are present, mainly from the Arica and Atacama traditions. The Arica component (ARI) includes both undecorated vessels, and decorated vessels, mostly jars and pots, that were possibly produced by specialist potters, such as Pocoma and Gentilar types (Uribe, 1999). More distant traditions from the Atacama region are represented, especially service bowls of the Aiquina and Dupont types (ATA).

The Late Period ceramic component identified in the excavations is represented mainly by Local Inca Altiplano pottery (IKL), characterized by Inca-style vessel forms such as aribaloid jars but produced with local raw materials under imperial influence (Uribe et al., 2007). Imperial or Cusco Inca ceramics (INK) were also recovered, although in low frequency. Less common finds include fragments from the Late Formative Period from the pampa (QTC) and from historical times (ETN).

Excavations at Pariqollo yielded 886 ceramic fragments. Of these, 67.7% are associated with the LIP, with 56.2% belonging to the local Tarapacá component (PCH-PGA types). One PGA fragment was modified into a possible spindle whorl. The most common forms are restricted vessels such as cooking pots (PGA, 30.6%) and storage jars (PCH, 25.6%), which were found in all excavated units and throughout the occupational sequence. These are followed by Altiplano-style plates and bowls (ALT, 4.8%), bowls from the Atacama region (AIQ-DUP, 4.4%), and some fragments from the Arica style (0.4%). The Late Period component accounts for 8.4% of the total (IKL, 8.2%; INK, 0.2%). Isolated amounts of pottery from the Late Formative (0.2%) and Colonial periods (0.4%) were also recorded. Eroded material represents 23.3% of the assemblage.

At Kuico, 487 ceramic fragments were recovered from artificial terraces and 223 from a storage pit (troja). A 99.8% of the material was concentrated directly above the sterile or basal occupation layer and 80% relates to LIP types, with approximately three-quarters of these attributed to local Tarapacá styles and the remainder exclusively to the Altiplano component. The most common type is PCH (48.3%), followed by PGA (24.2%), showing a contrast with Pariqollo which yielded mainly PGA cooking pots. Both types are present across all structures excavated and throughout the stratigraphic sequence, and share the same technological features observed at Pariqollo. These are followed by Late Period types (12.7%), represented by Local Inca ceramics.

The ceramic assemblages at Pariqollo and Kuico show differences that suggests distinct patterns of use and occupation. At Pariqollo, the ceramic set is diverse in both form and function. In contrast, at Kuico, the morphological and functional analysis reveals two well-defined groups of vessels (Figure 7). On the one hand, there are large, restricted containers, mainly liquid storage jars with rim diameters between 31 and 34 cm, associated with local PCH-PGA types. The only outlier is a fragment of an aribaloid vessel of the IKL type. On the other hand, open vessels such as service plates and bowls (pucos), with diameters ranging from 11 to 18 cm, are linked to the Altiplano component.

Figure 7

Ceramic vessel forms and rim diameters from Pariqollo and Kuico. *Represents an outlier, identified as a fragment of an aribaloid jar.

At Pariqollo, around 10.7% of the fragments exhibit use-wear traces, mainly soot, while 8.0% correspond to diagnostic vessel parts. A high proportion of eroded fragments (23.3%) coincides with the very low refitting rate of the assemblage (around 2%), with sherds widely dispersed and heavily altered. Conversely, Kuico shows higher refitting rates (near 20%), suggesting deposits with greater contextual integrity and less post-depositional disturbance. Eroded fragments account for only 7.3% of the total, and use-wear such as soot is very scarce.

6.3.2 Stone tools

The Pariqollo assemblage comprises 68 lithic artifacts: 65 flaked stone pieces, one core, and two ground stone implements. Compared to Kuico, it displays greater raw material diversity, primarily silex-chalcedony and basalt, mostly of good to very good quality. Approximately 60% of the pieces are complete. Evidence of thermal alteration was identified, most likely related to intentional heat treatment to improve knapping quality. In terms of technological categories, flakes and flake fragments predominate, followed by angular debris and retouched tools. The retouched tools include flakes in basalt, obsidian, and silex-chalcedony, as well as a fractured scraper and a used flake. The ground stone implements consist of a discoidal piece of indeterminate function (sedimentary rock) and a handstone (igneous rock). The single core is a small silex-chalcedony piece with a multifacial debitage method. Of particular relevance is the assemblage of grinding implements distributed throughout the site, such as handstones and grind slabs, observed on several enclosures.

The Kuico assemblage comprises 25 lithic artifacts: 23 flaked stone pieces and two ground stone implements. The raw materials are of good knapping quality, mainly white quartz and basalt. Fragmentation is relatively high (52%), with mostly proximal and distal fragments of flakes or flake tools. Technologically, the assemblage is dominated by flakes (complete and fragmented), with a few retouched tools (including a scraper/spade and a notched piece) and angular debris. Ground stone artifacts include a handstone and a polisher/rubber, both in andesite. Retouched tools are scarce and exhibit marginal use-wear, suggesting functions such as scraping, cutting, digging (spade), and grinding.

Although the frequency of stone tools recovered from the excavations is very low and the assemblages are highly fragmented at both sites, these materials are consistent with other artifacts and activities documented. Functional inferences point to scraping, cutting, and grinding activities, as well as the activation and maintenance of the tools. Nevertheless, it is important to note the broad presence of grinding implements distributed across many enclosures at Pariqollo, while at Kuico the presence of spades suggests possible digging activities.

6.3.3 Zooarchaeology and archaeobotany

In Pariqollo, archaeofaunal remains present a poor conservation, probably related to a domestic context and older occupations. A total of 625 fragments were recovered, of which a 54.4% are unidentifiable. Among the identifiable fragments, at least four taxa were recognized: Camelidae, Rodentia, including L. viscacia (MNI = 2) and other minor rodents such as Auliscomys sp., together with a hemimandible of Liolaemidae sp., as well as fragments of an undetermined medium-sized mammal and diaphyses possibly belonging to birds (Table 2). Camelidae represents an MNI of seven individuals, three of which have diagnostic age features, with one subadult individual under 2 years of age, and two adults, one over 2.5 years of age and the other up to 4 years of age.

Table 2

| Site | Identifiable fragments | Unidentifiable fragments | Total | % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camelidae | Rodentia | Medium sized mammal | Bird/Mammal? | Reptilia | ||||

| Pariqollo | 238 | 19 | 18 | 9 | 1 | 340 | 625 | 48.52 |

| Kuico | 92 | – | – | 2 | – | 569 | 663 | 51.48 |

| Total | 330 | 19 | 18 | 11 | 1 | 909 | 1,288 | 100.00 |

| % | 25.62 | 1.48 | 1.40 | 0.85 | 0.08 | 70.57 | 100.00 | |

Distribution of archaeofaunal remains from Pariqollo and Kuico (NISP).

In Kuico, poor conservation stands out, originating mainly from superficial deposition and consequent greater exposure, causing a lower rate of identifiability. A total of 663 archaeofaunal remains were recovered, of which 85.8% were unidentifiable. Among the identifiable fragments, two taxa were recognized, Camelidae and a few small mammals or birds (Table 2). The Camelidae remains correspond to an MNI of seven individuals, with diagnostic age elements indicating the presence of one individual less than 1 year old, along with another juvenile up to 1 years old.

Vegetal remains recovered from the excavations are scarce at Pariqollo, while at Kuico only small, carbonized wood fragments and charcoal flecks were found. The only squash fragment identified in Kuico was selected for radiocarbon dating. This scarcity may reflect both poor preservation conditions, given the heavily altered state of the materials, and/or a limited use of plant resources. Overall, the sample is generally poorly identifiable through macroscopic analysis.

At Pariqollo, our preliminary results indicate the presence of cultivated products, including scarce, heavily fragmented, and altered maize cobs, as well as maize stems and leaves, recorded in very low quantities in at least three excavation units. Additional cultivated remains comprise fragments of rind and seeds of Cucurbita sp. Among wild plant resources, cactus spines, possibly Browningia candelaria, a species present in the hills surrounding the pucaras, are consistently but sparsely represented. Some spines display polish, suggesting use as artifacts, while cactus wood was also employed as a tinderbox. Horsetail (Equisetum sp.) stems were also documented. All these wild species are locally available and identifiable in the immediate ravine environment. In addition, numerous endocarps of algarrobo (Neltuma sp.), a fruit originating from the pampa forest, were identified among gathered products.

The remaining plant material consists of unidentifiable fragments due to their small size and high degree of fragmentation. These include a considerable quantity of sticks from woody or herbaceous plants, as well as abundant wood debitage, probably from algarrobo. Notably, a possible spindle whorl made from a shaped and retouched wooden fragment was recovered.

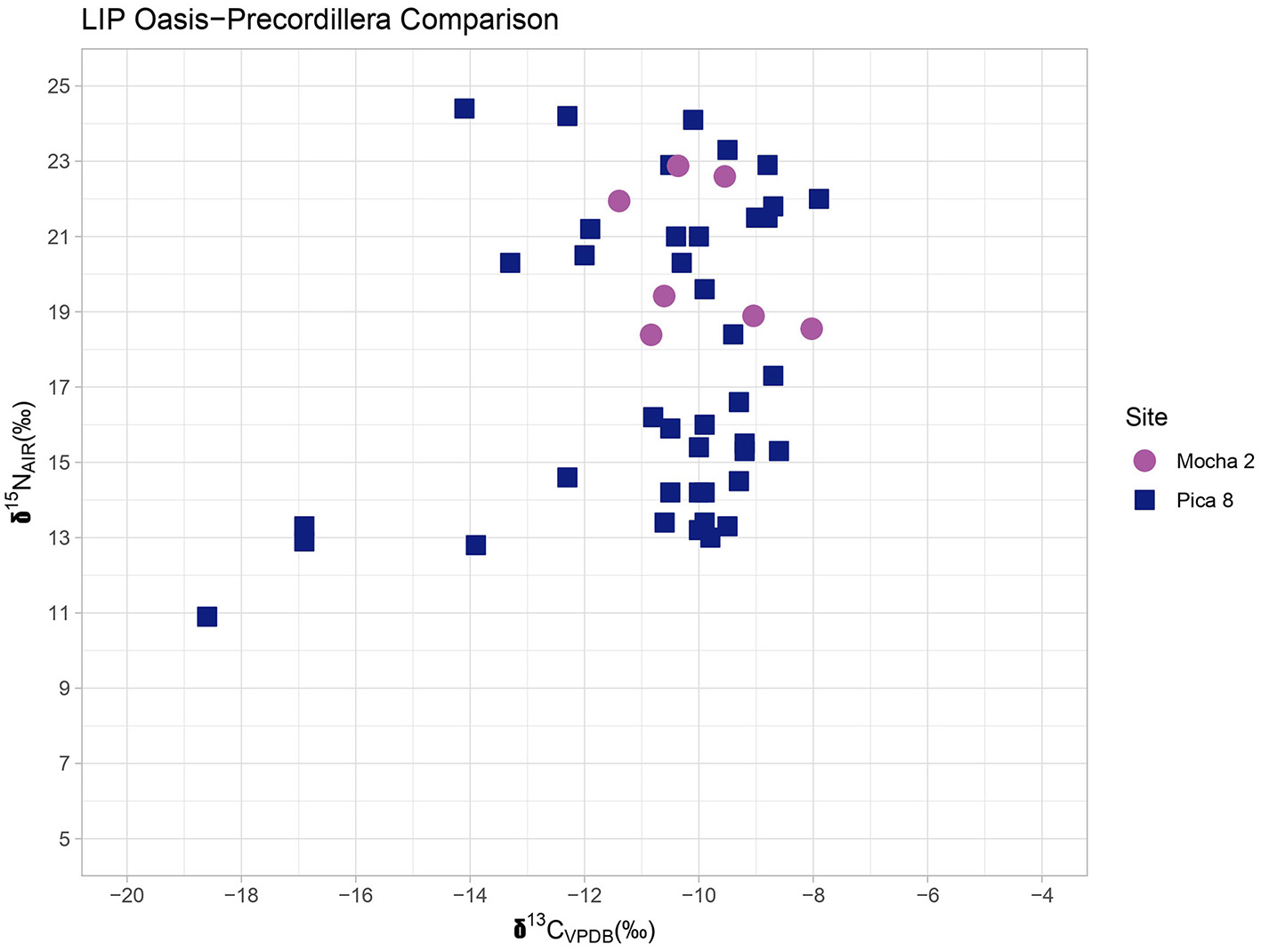

6.3.4 Isotope analysis

At the cemetery of Pariqollo (Mocha-2), sex and age estimations show five adult male individuals and four indeterminate adults. Stable isotope results show good collagen preservation for seven out of the eight individuals analyzed here, with C/N values falling between 2.9 and 3.6 (DeNiro, 1985; Ambrose, 1990). The means observed for δ13C and δ15N, considering the total of individuals from Mocha-2, are −10.0 ± 1.2% and 20.4 ± 2.0%, respectively. Male individuals (n = 4) show an average of −9.6. ± 1.3% for δ13C and 19.7 ± 2.1% for δ15N (Figure 8; Table 3).

Figure 8

Bivariate plot comparing δ13C and δ15N values from bone collagen by sex from individuals buried at Mocha-2 cemetery.

Table 3

| Site | Burial | Sample | Sex | Age | Sample weight (g) | δ13C VPDB (%) | δ15N AIR (%) | %C | %N | C/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mocha 2 | No information | Mandible fragment | Unknown | Adult | 1.19 | −9.5 | 22.6 | 47.49 | 17.82 | 3.1 |

| Mocha 2 | Burial 4 | Mandible fragment | Unknown | Adult | 1.05 | −11.4 | 21.9 | 46.83 | 17.23 | 3.1 |

| Mocha 2 | Burial 5 | Unidentified bone fragment | Male | Adult | 1.19 | −10.4 | 22.9 | 47.40 | 17.30 | 3.2 |

| Mocha 2 | Burial 13 | Unidentified bone fragment | Male | Adult | 0.28 | −18.6 | 21.3 | 46.57 | 8.30 | 6.5 |

| Mocha 2 | Burial 1 | Rib fragment | Male | Adult | 1.10 | −8.0 | 18.5 | 48.51 | 18.17 | 3.1 |

| Mocha 2 | Burial 2 | Rib fragment | Unknown | Adult | 1.10 | −10.6 | 19.4 | 47.94 | 18.16 | 3.0 |

| Mocha 2 | Burial 8 | Rib fragment | Male | Adult | 0.55 | −10.8 | 18.4 | 43.91 | 15.08 | 3.3 |

| Mocha 2 | Burial 10 | Rib fragment | Male | Adult | 1.17 | −9.0 | 18.9 | 48.30 | 18.27 | 3.0 |

δ13C and δ15N values from bone collagen by sex from individuals buried at Mocha-2 cemetery.

7 Discussions

7.1 The creation of private and public landscapes in the precordillera

According to ethnographic records, both pucaras are situated in the reaches of secondary ravines, called pallqa in aymara language, that entails a sacred position in terms of liminality, connecting different dimensions and worlds through ritual procedures (Urrutia, 2022). These pucaras were built atop hilltops overlooking the Tarapacá ravine, maintaining a direct visual connection with the valley and the agro-hydraulic infrastructure constructed on both sides of the quebrada, while the two sites are intervisible (Figures 9, 10).

Figure 9

Location of Pariqollo (A), facing Kuico (B), in relation to the agro-hydraulic infrastructure areas on the floor of the Tarapacá ravine.

Figure 10

Aerial view of Kuico and its disposition of the upper part (A), facing the red-colored hill where Pariqollo is situated (B). Between them runs the Tarapacá river and the many agro-hydraulic infrastructure (C). Stone wall and rounded stones arranged at the access to Kuico (D) (Photo by María José Herrera-Soto).

The radiocarbon dates obtained for the pucaras of Pariqollo and Kuico are consistent with the dates assigned to the Camiña phase (AD 1250–1450) within the Pica-Tarapacá Cultural Complex of the LIP (Uribe et al., 2007). Specifically, Pariqollo shows a slightly earlier occupation than Kuico, around ca. AD 1290, aligning with other regional evidence that places the consolidation of pucaras around AD 1250 (Uribe, 2006; Uribe et al., 2007). These dates are consistent with previous radiocarbon dates from Pariqollo (Moragas, 1991) and its cemetery Mocha-2 (Santana-Sagredo et al., 2021). Kuico developed around cal AD 1440, representing a late stage of the LIP and thereafter encountering the expansion of the Tawantinsuyu. However, these dates may reflect later phases of activity at the site, as the ceramic assemblage is predominantly composed of LIP types. Additional dating is therefore required to clarify its earliest occupation.

The excavations at both pucaras reveal certain similarities, but also differences in the establishment, intensity, and nature of their occupations. At Pariqollo, the evidence points to a denser, more intensive, and prolonged occupation, as indicated by stratigraphic depth and the recurrent presence of occupation floors, combustion features, and concentrations of primary refuse, interspersed with repeated episodes of cleaning and trampling, resulting in true palimpsests (Bailey, 2007). These occupational deposits are characterized by abundant pottery, ash, organic remains, and scarce lithic materials, all of which suggest repeated domestic activities, alongside specialized tasks such as the processing of plants, copper minerals and pigments sourced directly from a vein near the site, as reflected in the presence of stone tools for grinding grains and crushing mineral.

The high proportion of altered materials may indicate intensive and prolonged occupation, with repeated trampling over debris, supporting the interpretation of long-term, continuous, and everyday use of the settlement. This pattern likely reflects refuse from in situ breakage, small secondary refuse deposits, combined with maintenance practices within domestic, productive and public spaces. The identification of fill and leveling layers indicates that spaces were regularly prepared and maintained to enable the use of artificial terraces that supported continued occupation.

Consistent with the radiocarbon dates, the ceramic assemblage confirmed an occupation by local groups during the LIP, as indicated by the high frequency of Tarapacá-style fragments (Moragas, 1991), a pattern also observed in other pucaras in Tarapacá (Uribe et al., 2007). The ceramic assemblage from Pariqollo reflects a predominantly domestic occupation, associated with food preparation and consumption, as well as other diversified daily household activities. The significant presence of pots with a high proportion of soot suggests cooking activities, while restricted jars indicate the storage and handling of liquids and the preparation of beverages. The presence of plates and bowls further supports this domestic characterization, indicating serving and dining functions. Nevertheless, the scarce but recurrent presence of ceramics from nearby areas such as the Altiplano, Arica, and Atacama, may point to the circulation and exchange of goods, some of which could have served as status markers for certain inhabitants of Pariqollo (Uribe, 2006). This evidence suggests that people moved within the immediate surroundings while also participating in broader interaction networks.

In Pariqollo, productive and dietary practices were organized around the use of the immediate environment, combining multiple economic strategies, some generalized, and others specialized, that resulted in a varied diet with a strong local emphasis. Although preservation is poor, this interpretation is supported by the archaeobotanical record, which includes scarce maize remains, likely cultivated in the numerous agricultural terraces present in the ravine. Isotopic evidence from the Mocha cemetery (Mocha-2) further supports this, indicating the consumption of terrestrial protein (probably camelids), and C4 plants, most likely maize fertilized with seabird guano (Santana-Sagredo et al., 2021). The dietary composition observed here resembles patterns documented at lower-elevation sites, such as the Pica-8 cemetery in the Pica Oasis (Santana-Sagredo et al., 2015, 2019) (Figure 11). This similarity is striking given Mocha's high-altitude location and considerable distance from the coast, over 90 km inland, representing the farthest documented use of seabird guano in pre-Hispanic contexts.

Figure 11

Bivariate plot comparing δ13C and δ15N values from bone collagen between Mocha and Pica 8 (lowlands) (Santana-Sagredo et al., 2015, 2019).

In addition to maize, isotopic evidence indicates a diet that included C3 plants, further supported by the recovery during excavation of squashes likely cultivated locally, along with algarrobo seeds (Neltuma spp.) from the pampa. The constant presence of Equisetum sp. and herbaceous sticks reflect the broad use of plant resources directly available in the ravine. Overall, the people of Pariqollo maintained a local yet diverse diet and made extensive use of local resources, in line with other contemporary pucaras from the region (García and Uribe, 2012). This complemented generalized agriculture, evidenced by an extensive agro-hydraulical infrastructure reaching up to 39 ha adjacent to the pucaras and on surrounding hillsides.

The diversified economic and subsistence strategies employed by the inhabitants of Pariqollo are also supported by the taxonomic variety of the zooarchaeological record. This assemblage shows a strong local component from the immediate surroundings, including rodents such as viscachas (L. viscacia), as well as reptiles and birds. This likely complemented the consumption of locally raised domestic animals, as suggested by the predominance of camelid remains representing different age groups, as well as guinea pigs. Camelid meat was likely a staple component of the local diet. The stable isotope results of δ15N values indicate a reliance on terrestrial protein consumption, consistent with camelids being fed on crops fertilized using seabird guano (Santana-Sagredo et al., 2021). Taken together with the presence of architectural features that likely functioned as corrals and the presence of camelid coprolite in many of the excavated enclosures indicate that camelids, probably llamas, were raised and bred in the same locality, reflecting small-scale camelids management. In contrast to the findings reported by Moragas (1991), no evidence of fish was identified.

Archaeological evidence suggests that Pariqollo was established to sustain a social life closely connected to the broad productive use of the ravine and surrounding hills, while also functioning as a domestic settlement intended for permanent habitation. Its layout appears to have supported a wide range of activities, with evidence of continued occupation and areas dedicated to generalized and specialized tasks, as suggested by the presence of stone tools that point to scraping, cutting, and grinding activities. The main habitational and productive sectors of the settlement also featured terraces and corrals both on the hillsides and on the valley floor, while the occurrence of camelid coprolites suggests that animals may also have been kept on the hilltop.

In the context of regional evidence for the LIP, it represents a classic settlement of the Camiña phase in Tarapacá (Uribe et al., 2007), consistent with a location well suited to agriculture, herding, gathering, mining, and the movement of goods between the coast and the Altiplano (Uribe, 2006; Adán et al., 2007; Núñez and Santana-Sagredo, 2021). Pariqollo likely functioned as a central settlement or taypi (Bouysse-Cassagne and Harris, 1988), concentrating the daily habitational, productive, domestic, social, and ritual activities of the Mocha locality, while also serving as a local hub integrated into regional and extraregional networks. The presence of algarrobo seeds reflects movements to the pampa, whereas seabird guano and shell beads indicate contacts with the coast. Similarly, the occurrence of foreign ceramics points to connections with neighboring areas, particularly the Altiplano. In addition, the presence of open, cleared, and broad spaces may suggest the performance of public activities. Nevertheless, one of the most relevant public and ceremonial places was the Mocha-2 cemetery located at the very foot of the settlement.

Kuico follows the same logic as Pariqollo, being situated atop a prominent hill. However, its scale and layout differ considerably, beginning with its emplacement at the confluence of two rivers, or tinkuy (Rodríguez, 2023). A large hilltop area was adapted using simpler architectural methods, likely involving the conditioning of the bedrock, as suggested by the recovered lithic tools, and the construction of simple stone walls over the basal layer, enabling the initial establishment of an extensive network of enclosures. These spaces appear to have accommodated domestic activities but may also have served for keeping animals and storage purposes, as evidenced by camelid coprolites in structures and the presence of storage pits.

Central, more open, and standardized areas of approximately 20 to 37 m2 are prominent in the upper sector, in contrast to peripheral spaces averaging 4 to 5 m2. The consistent delimitation of these larger areas by walls suggests that they were designed to structure public activities, including exchanges, negotiations, or ritual events. Another distinctive feature of Kuico is the presence of discontinuous stone walls surrounding the settlement on its eastern side. This wall marks entrances and access through a sharp and complex geomorphology, probably guiding movement according to social and ritual protocols, while also serving as a prominent visual marker visible from multiple points. It thus appears to have functioned not strictly as a defensive structure, as has been proposed for other pucaras (Housse and Mouquet, 2023).

Although its large spatial extent, Kuico is defined by more ephemeral occupations. The excavated units display simpler and shallower stratigraphies. Primary refuse deposits are present but exhibit low artifact density and limited stratigraphic differentiation. They are often intermixed with fill layers and collapse material resulting from periods of disuse. Nevertheless, occasional signs of domestic use are evident. The relatively high refitting rate of the ceramic assemblage suggests deposits with greater contextual integrity and less disturbance, possibly related to less intense occupation or planned use and abandonment.

Preliminary bioanthropological results from the secondary burial indicate no signs of sustained physical violence but suggest that the individuals engaged in physically demanding activities, likely related to productive practices characteristic of life in the deep ravines and hilltop settlements, such as agriculture, camelid herding, and mining. These productive practices are likely represented in the burial context by the presence of a small stone shovel, a handstone, camelid remains, and red mineral pigment, which may reflect the performance of such tasks. The presence of these secondary burials suggests the incorporation of the dead into symbolic practices related to the social cycles and the symbolic reproduction of these spaces, likely through the representation of family, as the individuals refer to an adult man, a woman, and a subadult. This could potentially reflect Andean ordering principles, such as chacha-warmi (Mamani, 1999).

Overall, the occupations at Kuico suggest a low-density, planned, short and temporal use of the site. The presence of trojas (storage facilities) at Kuico, suggests a complementary function beyond strictly residential activities, perhaps related to the management and storage of surplus, seasonal gathering, or provisioning during periods of heightened population aggregation. The excavation of one troja revealed a structure excavated into the bedrock highlighting a strategy of infrastructure investment that supported intermittent, but logistically important occupation of the site. Taken together, these patterns suggest that while Pariqollo was a locus of sustained and intensive habitation, Kuico may have fulfilled a more periodic and public function within the local settlement system.

This is also supported by the ceramic assemblage, which shows a marked reduction in typological, morphological, and functional diversity. At Kuico two main groups were identified. The first consists primarily of large local PCH vessels for storing and containing liquids, and the second comprising plates and bowls from the Altiplano. The jars show little variation in size, suggesting homogeneous production by local communities within a common logic of containment and storage at the pucara. The service vessels are more varied in size, probably reflecting different communities, yet their similar forms, surface treatments, and technological features point to a shared Altiplano origin. These patterns suggest that the settlement's function was likely oriented toward specific occasions of congregation, ritual activity, and/or negotiation and exchange.

This interpretation is reinforced by the less diverse assemblage of animal remains, likely reflecting the customs and norms of such rituals, which in Andean contexts must follow prescribed procedures to ensure a successful or auspicious outcome (Gavilán and Carrasco, 2009). The presence of juvenile camelids at Kuico indicate periodic communal feasts. Ethnographic records support this interpretation, as the consumption of camelid meat in ritual contexts is typically associated with young individuals up to 3 years old (Urrutia and González, in press).

Together, these likely points to the two principal activities carried out at the pucara, drinking and eating, probably in the context of ritual or congregational gatherings. Considering this evidence, Kuico appears to represent a distinct type of social and public space. Local populations may have rationalized the increase in interregional contacts by creating spaces for encounter, exchange, and coexistence within contexts of population growth (Mendez-Quiros et al., 2023). The emphasis of the settlement seems to have been on accommodating large groups during specific events, functioning as a powerful and symbolic setting likely for negotiation, alliance-building, the management of tensions and conflicts, and the reaffirmation of social ties through festive gatherings and other Andean dynamics (Platt, 1980).

The strong predominance of local ceramics supports the idea of active participation by local groups, while the presence of highland vessels may indicate the intentional incorporation of foreign elements into these contexts, possibly as markers of social status (Uribe, 2006). Nevertheless, the relevant presence of Altiplano pottery could also reflect the direct involvement of highland groups in these dynamics. In this case, it may point to an intensification of Altiplano presence in the lowlands, as well as the participation of Tarapacá groups in highland settings, a social pattern not previously well documented for the late part of the Camiña Phase (Uribe, 2006). This social project, however, appears to have been interrupted by the Inca presence (Zori et al., 2017), as indicated by the apparition of Inca pottery in the upper strata of both settlements, which in the case of Kuico coincides with cal AD 1440 to 1450.

7.2 Social processes of the LIP through the pucaras of Mocha

Models that have attempted to explain the social processes of the LIP through the collapse of Tiwanaku, abrupt climatic, or warfare do not satisfactorily fit our case study (Arkush et al., 2024; Langlie and Arkush, 2015; Nielsen, 2007). Drawing on our results, we propose an interpretation of the LIP in Tarapacá centered on long-term local processes. The archaeological evidence from Mocha suggests that the emergence of pucaras and their productive spaces, often regarded as material hallmarks of the LIP, was not the result of a traumatic rupture, but rather the outcome of multiple, interrelated factors, including environmental conditions and regional-scale cultural processes, all mediated by sociopolitical and local decisions embedded in Andean dynamics.

More than two decades of systematic research have demonstrated that there is no substantial evidence for a Middle Horizon, instead revealing a long and complex Formative period (Agüero and Uribe, 2018; Uribe et al., 2020a). This pattern is supported by numerous radiocarbon dates from both coastal and inland contexts, which place Formative occupations up to at least AD 900–1000 and demonstrate a consistent continuity into the early stages of the LIP, referred to as the Tarapacá Phase (AD 900–1250). This continuity is evident in sites located in the same pampa, such as Pica 8 cemetery, as well as in settlements in the precordillera, such as Camiña 1, Nama, Chusmiza, and Jamajuga, which configured early conglomerated settlements associated with agro-hydraulic infrastructure around AD 1000. These occupations continued into later times during the Camiña Phase (AD 1250–1450), as observed in several sites across the region (Uribe, 2006; Uribe et al., 2007; Alvarado et al., 2021).

Although both Pariqollo and Kuico date to late moments of the LIP, our results suggest that their development stems from these long-term processes with deep local roots and cultural continuity from the pampa to the precordillera. In terms of material culture, Tarapacá-style ceramics predominate, displaying technological and stylistic features directly inherited from the Formative village of Caserones, where nearly 48% of the surface assemblage represents PCH-PGA LIP types. The remaining consists mainly of Formative pottery (Uribe and Vidal, 2012), which we have also identified at a basal stratigraphic unit in Pariqollo. No stylistic rupture or emergence of new ceramic traditions is observed. Instead, there is clear technological and stylistic continuity between the pampa and the highlands pucaras (Uribe et al., 2007), including those of Mocha, where these same ceramic types prevail. This supports the idea of local long-term cultural processes, sustained by the continuity of the PCH-PGA ceramic tradition developed at Caserones, which was produced and used across the main sites of the Tarapacá Phase (AD 900–1250) and continued into the Camiña Phase (AD 1250–1450) (Uribe et al., 2007; Santana-Sagredo et al., 2017). This evidence further reinforces the notion of social continuity rather than ruptures or population replacement by external groups or processes of colonization.

Abrupt climatic change does not appear to have been the primary driver behind the development of new settlements in the precordillera. Our radiocarbon dates indicate that both pucaras were already in use while the pampa was still being extensively and intensively cultivated, and that other social formations continued to develop from the early moments of the LIP (Uribe et al., 2007; Santana-Sagredo et al., 2017).

Archaeological research in the pampa, particularly at the mouth of the Tarapacá ravine, has focused on the extensive Iluga Túmulos monumental complex, established during the Formative period, which includes more than 100 artificial tumuli, thousands of hectares of raised agricultural fields, and the village of Caserones and its cemetery (Uribe et al., 2020b; García-Barriga et al., 2023). Although a decline in regional water availability is documented around AD 900 (Maldonado and Uribe, 2015), consistent with broader extra-regional climatic trends (Arnold et al., 2021; Arkush et al., 2024), archaeological evidence shows that both the tumuli and the agricultural fields on the pampa continued to be intensively used throughout the LIP, despite their location in the hyper-arid core of the Atacama Desert during a particularly dry climatic phase (Maldonado and Uribe, 2015).

During the Late Formative, Caserones contained a dense village life, characterized by increasing social complexity, inequality and competition but condensed only in this central settlement. This generated internal tensions that led to social fragmentation and segmentation, causing the progressive abandonment of Caserones around AD 1000, but also produced the replication of this socio-productive model in new contexts, with dates as early as cal AD 1020–1210, marking the initial phase of the LIP in settlements that continued into the later stages and the Late period (Uribe, 2006, 2008; Uribe et al., 2007). Alongside increasingly arid conditions (Maldonado and Uribe, 2015), these transformations prompted a reconfiguration of productive land use in the pampa and likely impulsed the reproduction and proliferation of settlements at higher altitudes, such as the steep valleys and hilltops of the local ravines in the highlands (Uribe et al., 2007).

Thus, the abandonment of the village of Caserones and the repositioning of settlements in hilltops cannot be attributed solely to climatic factors, as local communities continued managing water resources efficiently for agriculture in the pampa (García-Barriga et al., 2023; Vidal-Elgueta et al., 2024). However, they no longer maintained a centralized village life, instead relocating it to new spaces and sociopolitical formations in a segmented manner, such as the pucaras and productive areas in the upper valleys of the Tarapacá ravine, including Pariqollo and Kuico.

In many ways, the architectural, social and productive organization of the Mocha pucaras, particularly Pariqollo, reflects the social base that was no longer sustainable at only one village in the pampa. This is evident in the village-like architectural layout, which includes habitational, storage, and domestic spaces, an associated cemetery, and numerous productive areas connected to the main settlement, as seen during early LIP moments in sites such as Camiña and Jamajuga (Uribe et al., 2007). This pattern was consolidated during the Camiña Phase, with marked development between AD 1250 and 1450, just before the expansion of the Inca Empire, which would interrupt local autonomous processes.

From this perspective, the social changes of the LIP in Tarapacá cannot be explained solely as a consequence of Tiwanaku's collapse, abrupt climatic shifts and generalized warfare, but rather as internal transformations grounded in an ancestral social base that responded not only to extra-regional environmental and social dynamics, but above all, to local and internal tensions and decisions.

Building on this, neither a “state of insecurity” nor warfare appears to have driven the construction of pucaras (Arkush, 2017; Nielsen, 2007). Likewise, our results do not support the interpretation that the cases under study represent a line of defensive pucaras built by valley populations under pressure from highland groups, which later lost their defensive function and were transformed into more productive or interethnic enclaves (Nielsen, 2005).

Our results suggest that their placement and location appear to have been shaped by a multiplicity of factors that imparted distinctive characteristics to each pucara. In the Tarapacá region, deep ravines are periodically affected by catastrophic, rainfall-induced debris flows, as well as abundant water discharge during wet seasons causing floods (Sepúlveda et al., 2014). The decision to establish settlements in hilltop settings may thus have been a strategy to mitigate these environmental dynamics while maximizing the amount of arable land available for cultivation, as has been proposed for other pucaras in different parts of the South-Central Andes (Rivolta et al., 2021; Housse, 2024). As is still observed today, agricultural production takes place both on the valley floor and on multiple artificial terraces built along the hillslopes descending toward the main river flow, suggesting that settlement placement was tied to a productive order.

But, at the same time, Andean ritual and symbolic aspects were equally significant, as both pucaras were established in sacred locations (Urrutia, 2022). In the case of Pariqollo, the choice of location appears to have been influenced by its position on a hill distinguished from the surrounding landscape by its vivid red coloration, a feature likely imbued with symbolic significance. Additionally, certain architectural elements often interpreted as “defensive features,” such as the walls at Kuico, appear to have served different purposes. Recent perspectives on pucaras, such as those proposed by Housse and Mouquet (2023), argue for the symbolic and ritual nature of walled hilltop settlements.

In our case, rather than functioning strictly as a defensive feature fortification, the walls seem to have acted as spatial boundaries, separating but also bringing together distinct areas within the site and the landscape. Kuico is situated in a tinkuy, a symbolic place formed at the confluence of two rivers or paths (Rodríguez, 2023). Its layout suggests an emphasis on regulating circulation and access, potentially delineating zones with different functions or meanings. The presence of designated entrances further supports the notion of a controlled or symbolic threshold, likely associated with protocols, norms, and costumes rather than strict military defense. Although not mutually exclusive, these architectural arrangements do not appear to have been produced by a defensive or coalescent impetus (Arkush, 2017), but rather as part of the configuration of a socially charged place.

On the same note, warfare is not supported by our bioanthropological and material analyses. The lithic evidence does not support a warfare-related function but rather points to the production and maintenance of tools. Additionally, the results from the secondary inhumation at Kuico reflect a lifestyle associated with daily productive activities, likely agriculture, camelid husbandry, and mining, as the bodies were accompanied by camelid bones, a miniature stone shovel, and red mineral pigment probably sourced from Pariqollo. Other lines of evidence, such as bioanthropological research and studies of material culture related to conflict and warfare in northern Chile, have challenged the hypothesis of generalized, widespread, or endemic violence during the LIP (Pacheco et al., 2016).

These conclusions are based on the analysis of violence-related injuries (VRI), as well as the study of artifacts such as helmets and breastplates, and rock art motifs associated with warfare. Rather than indicating widespread conflict, these elements are interpreted as symbolic displays of power within specific sociopolitical contexts. Furthermore, the low prevalence of injuries among individuals buried in LIP cemeteries of Tarapacá suggests that such evidence was more likely the result of domestic violence or ritualized combat rather than organized or intergroup warfare (Pacheco and Retamal, 2017; Pacheco et al., 2016). These forms of violence were probably inherited from Late Formative dynamics, in which physical aggression may have functioned as a mechanism of internal regulation during periods of social effervescence (Uribe, 2008; Herrera-Soto et al., 2024).

Although multiple scenarios are possible, this may represent a case in which contacts, interaction, competition and exchange between different groups in the Mocha locality intensified. This is evidenced by the clear presence of a highland ceramic component, within a broader context of increased extra-regional interactions and population growth (Mendez-Quiros et al., 2023), which probably led to intensification of intra and inter-community tensions. As previously proposed (Uribe, 2006), the local population of Tarapacá appears to have established increasingly sustained contacts with the highlands, and vice versa, that in the case of Mocha converged in productive, symbolic and powerful places (Jennings and Swenson, 2018).

This convergence may have been formalized and organized through the creation of specific spaces intended for exchange, but also coexistence, social interaction, and negotiation, as seen at Kuico. Such processes would not necessarily imply a harmonious relationship (Núñez, 1984), as they may have been marked by tensions and could have resulted in conflicts framed within Andean traditions, such as tinkus, ritualized fights and festivities associated with religious celebrations and the agricultural calendar (Platt, 1980), although explicit forms of violence may have also occurred.