- 1Language and the Anthropocene Research Group, Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, Jena, Germany

- 2Department of Asian and North African Studies, Ca' Foscari University of Venice, Venice, Italy

Claims that Japanese society has lived in “harmony” with Nature and can therefore provide lessons for global sustainability have a long history. While such “eco-nativist” ideas have been the subject of an extensive critical literature, here we consider three topics that have so far escaped in-depth attention. First, we trace how environmental archaeology became integrated into this approach from the 1980s, examining how palynologist Yoshinori Yasuda combined traditional environmental archaeology with the comparative civilisation theory begun by ethnologist Tadao Umesao in the 1950s. Second, we ask whether Japanese eco-nativism can be said to represent an Indigenous approach to environmentalism and sustainability. This section also explores how Yasuda's concept of a “Pan-Pacific Civilisation” attempted to link Japan with other Indigenous or non-Western ecologies. Third, we analyse the uneven representation of the Japanese past in eco-nativist writings. Noting that most attention has been paid to the hunter-gatherer Jōmon, early agricultural Yayoi and early modern Tokugawa periods, we argue that the near total absence of discussion of the Kofun era of early state formation reflects a reluctance to consider issues of social inequality within the utopian eco-nativist approach. We conclude that this selective use of the past is inconsistent with an Indigenous or native environmentalism.

1 Introduction

A large literature, primarily in Japanese but with occasional refractions in other languages, extolls the idea that the people of Japan have long lived in harmony with Nature and that they can therefore provide lessons for future sustainability. English publications by influential writers in this genre include Umehara (1989, 1999); Yasuda (1990, 2006, 2009, 2013a); Kawakatsu (2006) and Ochiai (2007). The genealogy of these ideas is complex and draws on native religious and other traditions, Orientalist views of Eastern civilisations, and a type of Self- or Neo-Orientalism wherein Japanese writers use Western frameworks about Asia but invert them into new interpretations (cf. Kalland and Asquith, 1997; Morris-Suzuki, 1998; Thomas, 2001; Stock, 2023; Droz et al., 2025). In Japan itself, the discourse can be traced back to the nativist Kokugaku (“national learning”) movement of the late 18th century (Hudson et al., 2025). Moto'ori Norinaga (1730–1801), the most influential Kokugaku scholar, posited that Japan had formed a harmonious, natural community without social conflict until outside cultural influences such as Buddhism and Confucianism damaged the pristine harmony of the body politic (Harootunian, 1988; Nishimura, 1991; Burns, 2003). From this basis, new ideas about the relationship between the nation and the natural environment developed over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries to form a broad genre of writings linking the natural environment with Japanese ethnic nationalism.

There is an extensive critical literature on this genre (e.g., Buruma, 1987; Reader, 1990; Morris-Suzuki, 1998; Prohl, 2000; Habu and Fawcett, 2008; Reitan, 2017; Rots, 2017; Lindström, 2019; Hudson, 2021; Hudson et al., 2022, 2025). That literature frequently uses the label “eco-nationalist” for these writings but the terminology can differ depending on the analytical focus. Here we employ the label “eco-nativist” because our interest is not on nationalism per se but rather on the role of the writings as Indigenous or native critique. Our terminology builds on Harootunian's (1988) classification of the Kokugaku movement as “nativist”, as well as Kuwayama's (2004) concept of “native anthropology” discussed below.1 We recognise that the term “eco-nativism” might be regarded as controversial within the context that “native discourse tends to be seen as “propaganda” promoting a particular political position. This perception keeps natives outside the respectable academic community” (Kuwayama, 2004, p. 13). However, “eco-nativism” is used here to attempt a more “neutral” framing to explore how archaeology has been inserted into the discourse since the 1980s. We do not a priori exclude the possibility that Japanese eco-nativist writings might contribute insights to sustainability science and we acknowledge the role of critical responses to Western colonialism in the formation of the genre (Hudson, 2018). We also note the potential of ethno-nationalism to foster pro-environmental behaviour under some circumstances (Conversi, 2020).

The present paper examines three topics that have so far escaped detailed attention in the literature on Japanese eco-nativism. The first is the role of environmental archaeology. Since the 1980s, results from environmental archaeology have helped Japanese eco-nativist discourse position itself as a source of non-Western knowledge on sustainability. Our analysis focuses on the work of palynologist Yoshinori Yasuda (b. 1946) who played a key role in developing this approach. Although some historiographic details in this section may seem arcane to readers outside Japanese Studies, Yasuda's work is of broader interest as a concrete—and perhaps unique—example of the use of environmental archaeology to construct a native environmentalism. Second, we discuss to what extent Japanese eco-nativism can be considered to represent an “Indigenous” approach to environmentalism and sustainability. This analysis is tied to debates over “native anthropology” and the marginalised position of Japan in certain areas of global knowledge production, particularly within the humanities (Kuwayama, 2004). Finally, we explore the uneven representation of Japanese history in eco-nativist writings. The genre has given most attention to the hunter-gatherer Jōmon (ca. 14,500–1000 BC), the early agricultural Yayoi (1000 BC–AD 250) and the early modern Tokugawa (1603–1868) periods. We analyse the near total absence of the Kofun era (AD 250–700) of early state formation, examining how narratives of social inequality have been avoided by the eco-nativist genre.

In terms of methodology, the present paper considers its subject from two main perspectives: historiography and archaeology. Our objective is not just to critique the (sometimes outlandish) claims found in the eco-nativist writings we discuss, but rather to place them within a broader history of ideas regarding Japanese identity. For this reason, the paper includes several detailed analyses of historiographic context. Second, we base our empirical critiques of eco-nativist ideas on archaeological evidence, especially in Section 4 dealing with the Kofun period.

2 Environmental archaeology and eco-nativism in Japan

Environmental archaeology began in Japan with the very first excavations in that country, conducted by American zoologist Edward Morse at the Ōmori shell mound in Tokyo in 1877. The publication of Morse's results in what is said to be the first academic monograph published by a Japanese university (Morse, 1879; Oguma, 2002, p. 3) soon led to a debate over mollusc assemblages and changing shorelines in the pages of Nature (Darwin and Morse, 1880; Dickins, 1880). However, the scientific archaeology begun by Morse proved short-lived and the field moved in a different direction under the influence of native scholars such as Shōgōro Tsuboi (1863–1913) who were explicitly critical of Morse (Oguma, 2002, p. 13). Over the 20th century, Japanese archaeology developed into a vibrant field, but questions relating to the natural environment were often sidelined, especially under the influence of Marxist historiography in the early post-war decades (Maruyama, 1974; Hudson, 2018). Nevertheless, a significant body of innovative research introduced a range of environmental approaches, including zooarchaeology (Kishinouye, 1909-11; Naora, 1965; Akazawa, 1972), archaeobotany (Kotani, 1972; Nishida, 1973) and shell growth analysis (Koike, 1973, 1979). Tsukada (1986) provides a detailed bibliography of pollen analyses conducted in Japan up to that date.

Against this background, in 1980 a geographer trained in palynology named Yoshinori Yasuda published a book called Kankyō kōkogaku kotohajime. Although the English title An Introduction to Environmental Archaeology is included at the beginning of the work, the Japanese title has the meaning of “The Beginning of Environmental Archaeology”. The pollen sequence data used in this book were taken from the author's doctoral dissertation, published in English in 1978.2 Appearing only 2 years apart, these works are completely different in style and interpretation. Yasuda (1978) is a scientific monograph without any explicit hint of nationalism. Based on pollen sequences, Yasuda explores the vegetation history of the Japanese archipelago and is not afraid to discuss periods of forest destruction in Japan, a phenomenon which he dates from the Kofun period onwards. He concluded that “the Laurilignosa [broadleaf evergreen] forest around Osaka bay was destructed [sic] by Kofun man and subsequently a secondary forest of Pinus densiflora expanded rapidly” (Yasuda, 1978, p. 243). This forest destruction was caused primarily,(Yasuda 1978, p. 258) argued, by the production of the Haji and Sue ceramic wares of the period, as well as by the construction of the kofun mounded tombs from which the period takes its name. Yasuda (1980) is a very different work. The book includes text and interpretations that can be placed squarely within the Nihonjinron genre of cultural nationalist writings about Japan (cf. Dale, 1986; Sugimoto, 1999). A key theme of the book is the idea of Japan as a “forest nation” (mori no kuni). As discussed in Hudson et al. (2025), this theme is introduced via colonial tropes regarding Korea (which was occupied by Japan from 1910 to 1945). Unlike his later works, however, the book follows Yasuda (1978) in emphasising deforestation in the early historic era. Chapter 5 of Yasuda (1980) is titled “The culture of the era of forest destruction: the Kofun and historical periods”.

Yasuda's appropriation of the term “environmental archaeology” is confusing and requires careful explanation (see also Supplementary material). On the one hand, Yasuda frequently describes himself as the “creator” of a new field. (Yasuda 1999, p. 34), for instance, makes the following claim: “In 1980, the present author was the only researcher in environmental archaeology and it was not even considered as important within Japanese archaeology. Over the last 20 years, however, environmental archaeology has rapidly developed as part of the field of archaeology.” The original Japanese of the first sentence might be considered somewhat open-ended but it certainly implies that in 1980 Yasuda was the only scholar anywhere in the world concerned with environmental archaeology. That conceit is flatly contradicted by Yasuda's earlier publications, notably (Yasuda 1978, p. 121–132) which provided a detailed overview of environmental archaeology in Japan to that point. Elsewhere, however, Yasuda explains his “environmental archaeology” in a quite different framing as a type of comparative civilisation theory. A key influence in this respect was ethnologist Tadao Umeao (1920–2010) (Yasuda, 1980, p. 9, 2013, p. 123–125). In 1957, Umesao published an essay titled “Introduction to an ecological view of civilisation”. The impact of this essay on Yasuda and on post-war Japanese letters in general is discussed in our Supplementary material. The field that Yasuda describes as kankyō kōkogaku might thus be defined as the use of (selected) information from environmental archaeology—particularly relating to deforestation and climate change—in order to support theories of the comparative evolution of civilisations.

3 Japanese eco-nativism as indigenous critique

The incorporation of environmental archaeology into Japanese eco-nativist discourse from the 1980s can be seen as an attempt to develop a native environmentalism in opposition to the West and north China. The resulting body of writings presents Japan as a source of traditional or native knowledge with respect to sustainability and ecological living. This knowledge is not explicitly described as “Indigenous”. In Japanese the standard term for Indigenous people is senjūmin 先住民, meaning the people who previously lived in the territory. In Japan, this word is primarily used for the Ainu people of Hokkaido, an island colonised by Japan in the late 19th century (Hudson et al., 2013). Earlier episodes of colonisation are harder to insert into an Indigenous framework. Even though research in anthropology, archaeology, historical linguistics and related fields has clearly shown that there was large-scale immigration into Japan in the Bronze Age Yayoi period and that the ethnic Japanese date from that time (Hanihara, 1991; Hudson, 1999, 2022; Robbeets et al., 2021), there is a long tradition of regarding the Japanese people as a homogenous ethnic group. This problem is not, of course, unique to Japan; Native American objections to the “Out of Asia” Bering Straits migration hypothesis is a comparable example. As noted by (Kuper 2003, p. 392), “If [Cree] ancestors were themselves immigrants [from Asia], then perhaps the Cree might not after all be so very different from the Mayflower's passengers or even the huddled masses that streamed across the Atlantic in the 1890s.” The Japanese nativist response to this problem has been to emphasise the “structural” or cultural elements of the Japanese people. Umehara (1990) defined Japanese culture as the synthesis deriving from the “harmonious opposition of two focal points, the forest culture that is Jōmon and the paddy field culture that is Yayoi.” While there were two contributing elements—one of which derived from relatively recent immigration—it was the harmonious integration of the two that led to the formation of the Japanese.

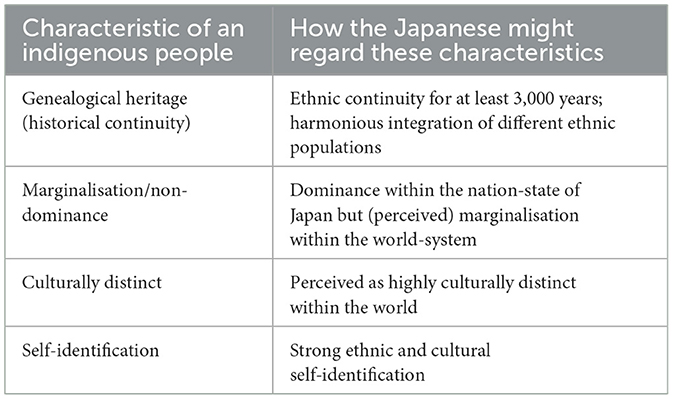

Table 1 lists some commonly-used definitions or characteristics of Indigenous people extracted from Sylvain (2002) and Watkins (2005). As mentioned, writers such as Umehara have been able to make the problem of immigration “disappear” by emphasising the “integration” of different population groups (Hudson, 2022; Hudson et al., 2020). It should be emphasised, however, that this reflects the position of the majority rather than the minority society. In classifying the Ainu as the “proto-Japanese”, Umehara (1984) coerces the Ainu into a Japanese rather than an Indigenous identity. In their re-evaluation of the Jōmon as “primitive Japan”, Umehara and fellow eco-nativists also generate a shared space of Japaneseness through the co-existence or “layering” of different time periods (cf. Fabian, 1983; Harootunian, 2000; Hudson, 2021, p. 39–47).

Japan is certainly not marginal to the global economy, but might be considered to hold such a position in terms of the global economy of knowledge, especially within the humanities. (Kuwayama 2004, p. ix) insists that “Japan is placed on the periphery of the academic world system.” Noting the importance of including people excluded from or marginalised in historical discourse, (Denham 2024, p. 4) reminds us that “There are disproportionate geographical and socio-economic biases within global archaeology” and states that “There are longer histories and greater investments in archaeological practise in some regions such as Australia, China, Europe, North America and Southwest Asia.” However, Japan does not make Denham's list despite the long and highly intensive history of archaeological research in that country. Issues of marginalisation, cultural distinctiveness and self-identification are often discussed in the eco-nativist literature in terms of Japan's “pride” or “confidence” within the world system (Umehara, 1989; Supplementary material). Yasuda (1989) also contrasts “passive” and “active” scholarship in Japan: while early research had been passive because of “The sense of fear and shame that we [Japanese] were coerced to appear on [the world] stage” in the late 19th century, a need for more “active” research had become pressing. Exactly what is meant by “active” is not really explained but seems to be associated with the following claims: “Ever since the Jōmon period, Japan has maintained a belief that places importance on coexistence with nature. We have kept cultural and social traditions that excel in letting nature live and thus letting ourselves live in it. Do we not have the obligation to present a grand model that would reflect the comparative studies of various aspects of Japanese culture and society from the viewpoint of world history?” (Yasuda, 1989).

If the words “Indigenous” and “native” are largely synonymous, Kuwayama notes that Third World scholars generally prefer the former due to the colonialist baggage of the latter. (Kuwayama 2004, p. 3) himself, however, opts for “native” for three reasons: first, the word testifies to the colonial roots of anthropology; second, “it draws attention to the ‘intrusion' into the academic space of former colonial powers by their subjects”; and third, it signals a radical change taking place in the structure of anthropological knowledge. Although Japan was a major colonising and imperialist power during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, (Kuwayama 2004, p. 3) proposes that “the Japanese can be natives, despite their own colonial past, for they have been, and continue to be, studied and described by Western anthropologists.” (Kuwayama 2004, p. 13) nevertheless accepts that “native discourse has often supported cultural nationalism” and that “native discourse tends to generate reverse Orientalism or so-called ‘Occidentalism' because it is constructed in opposition to the prevailing discourse in the West.”

There is a large literature discussing the sustainable practises of Indigenous peoples, especially when compared to colonial and capitalist patterns of resource use (Berkes, 2008). While it is important to remember that people in the past would not have understood “sustainability” in the same way as today (Harkin and Lewis, 2007), Indigenous voices and those from the Global South remain of great importance in current debates (Echoes et al., 2024). Notwithstanding the important issues raised by Kuwayama, however, the position of Japan in such debates is complex. Japan was never colonised, except by the post-war American Occupation (1945–1952, 1972 in the Ryukyu Islands). By contrast, from the late 19th century Japan seized its own large empire in East Asia and the Pacific, generating significant environmental impacts on its colonial possessions (Morris-Suzuki, 2013; Higuchi, 2015; Hung, 2015). Given this colonialist history and the fact that Japan is today one of the most affluent countries in the world, is it possible for Japan to present itself as a “native” green society?

Traditional ecological knowledge can be conceptualised as consisting of four interrelated levels: local knowledge of land, plants and animals, land and resource management systems, social institutions, and world view (Berkes, 2008, p. 16–18). Within this scheme, Japanese eco-nativism is heavily “top-down”; it rarely considers local practises but makes the assumption that all Japanese share the same world view about Nature. Umehara (1990), for example, insists that “Japan has been successful because it is made up of 120 million people who have virtually the same blood in their veins, speak the same language, and think in the same way.” Furthermore, the genre has little to say about social institutions, something which influences its treatment of Japanese history (see Section 4). Yasuda provides an extreme example when he writes about wheat and livestock farming: “As a method of land usage [this] might strike us [Japanese] as comparable to using a well as a toilet.” This is because “Mountains are not toilets. They are holy places. They should have forests. … Most of you here [participants of a 2005 lecture at Nagoya University] see mountains and feel something divine, but people from Europe regard mountains as no more than places for playing sport” (Yasuda, 2010, p. 38, 42). These comments make no attempt to consider the complex histories of mountain land-use in both Japan and Europe (cf. Armiero, 2011; Oka, 2008; Viazzo, 1989).

Japanese eco-nativism can be understood as a type of mimicry of the subaltern (cf. Bhabha, 1984). The genre adopted the European preoccupation with mastery over Nature as a mark of civilisation and inverted it. The only truly sustainable civilisations were now those that lived in harmony with Nature—and Japan was the premier example. If, since the 1970s, mainstream environmentalism has reproached humans for their destruction of Nature, the Japanese could be absolved of blame. Of course, Japan's rapid adoption of industrial modernity led to its own environmental crises, but that inconvenient history was either glossed over or explained by Western corruption of the Japanese body-politic.

There is an important sense in which all societies retain elements of traditional ecological knowledge. Writing about wild plant use in contemporary Croatia, for instance, Runjić et al. (2024, p. 10) lament how uses of some plants “that were probably widely known by most inhabitants of many villages are now remembered by a single person in one.” Such knowledge is threatened by a range of similar social changes, although minority Indigenous people and other groups affected by settler colonialism face unique challenges. Japanese eco-nativism insists that Japanese “civilisation” can claim such a unique environmental status in world history that it offers a single path to ecological salvation for the rest of the world (Yasuda, 1999). To a certain extent, this might be understood as a reaction to Western colonial pressure (Hudson, 2018). Nevertheless, the exceptional claims made by Japanese eco-nativism require both further empirical testing (e.g., Hudson et al., 2022) and a deeper engagement with issues of global environmental justice.

3.1 “Pan-Pacific civilisation”

The position of Japan in debates over Indigenous or native ecologies is further complicated by Yasuda's attempt to insert Japan into a broader “Pan-Pacific civilisation”. This framing includes Japan, Mainland and Island Southeast Asia, coastal Northeast Asia, the eastern half of Australia and most of the Americas. The tropical forests of West Africa are also included in some versions (Yasuda, 2007, p. 493). This unlikely classification has been explained as a division between “plant civilisations” and “animal civilisations” (Yasuda, 2007) as well as between civilisations that drink milk and those that don't (Yasuda, 2015).3 In Yasuda's presentation it is unclear why Northeast Asia and the Americas are “plant civilisations” when the hunting of both marine and terrestrial mammals was of great importance across those areas. An extension of the “Great East Asian Fertile Triangle” discussed in Section 4.1, Yasuda's “Pan-Pacific civilisation” is an attempt to generate an Indigenous genealogy for Japanese environmentalism. This attempt is entirely unconvincing because of the way it ignores the complex histories, both colonial and precolonial, of the regions he considers.

4 The Kofun period and the uneven representation of the past in Japanese eco-nativism

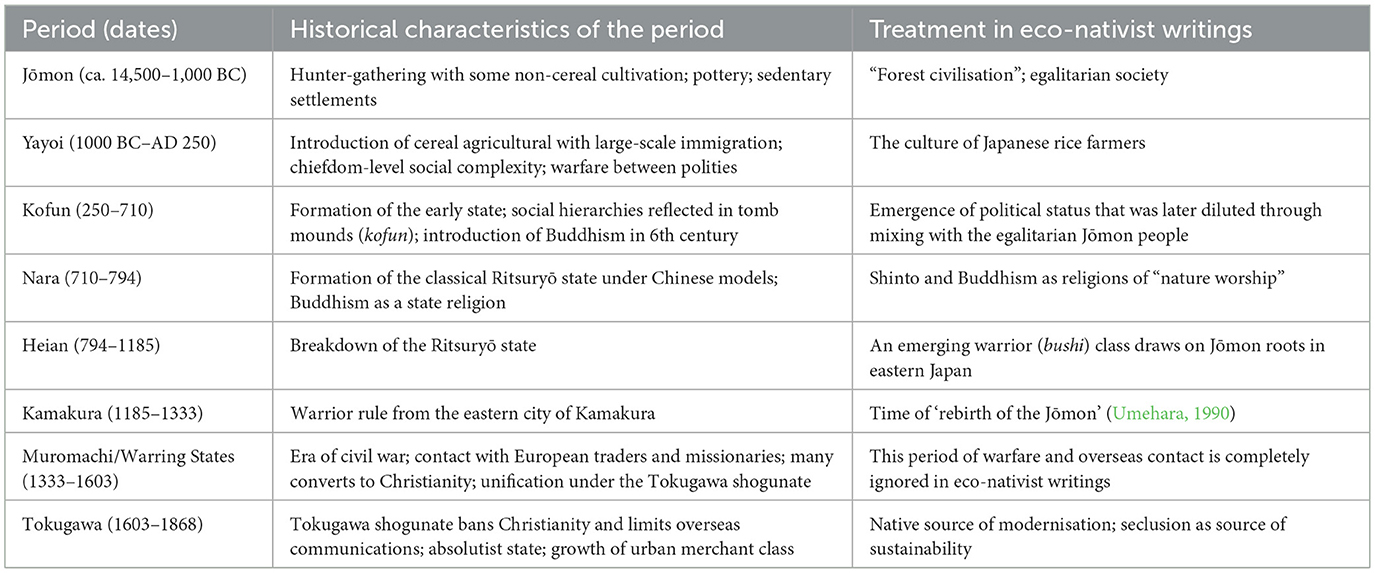

In the last section of this essay we explore the selective representation of the past in Japanese eco-nativist writings. As noted already, historical and ethnic continuity is a key element in the construction of Indigenous identities. However, the Japanese eco-nativist genre privileges perceived structural and cultural attributes over actual biological or historical (dis)continuities. The genre has given most attention to the hunter-gatherer Jōmon, the early agricultural Yayoi and the early modern Tokugawa periods; other stages of Japan's past receive little or no consideration (Table 2).

Especially noticeable for its absence is the Kofun period. For most archaeologists and ancient historians, the rise of the state and associated social inequalities has been one of the key problems of Japanese history (Barnes, 2007; Sasaki, 2017; Tsude, 1992). At the beginning of Japanese archaeology, the Kofun or “Tomb Age” was regarded as the most important stage in the national storey; the Jōmon was associated with a primitive “Stone Age”. The Yayoi initially formed an intermediate stage between these two periods rather than as a separate period in its own right. It was only from around the 1970s that Jōmon and Yayoi began to become “household names” in Japanese history (Habu and Fawcett, 1999; Yamada, 2015; Yoshida and Ertl, 2016). This shift is also visible in the way Japanese archaeology has been introduced overseas. It is interesting, for example, that in Italy the Yayoi was practically forgotten in the 1958 exhibition Tesori dell'Arte Giapponese (“Treasures of Japanese Art”) held in Rome, but received greater attention in the 1995 exhibition Il Giappone prima dell'Ocidente (“Japan Before the West”) (Sun and Zancan, 2024). While the Kofun period continues to receive extensive attention from archaeologists, both Japanese and non-Japanese, the period remains largely ignored in the eco-nativist genre.

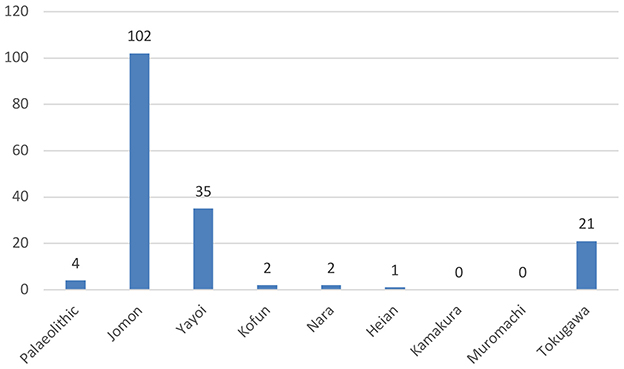

It is difficult to quantify the treatment of the Kofun period in Japanese eco-nativism. Since the 1980s, that genre has produced a vast output of publications, almost exclusively in the form of books aimed at the general reader. Those publications use minimal or no footnotes and rarely contain indexes. Our conclusions about the selective representation of the different periods summarised in Table 2 are based on extensive reading of the genre for this paper and previous publications. Figure 1 provides a graphic display of this selective representation. Though based only on a small sample of twelve publications (Umehara, 1989, 1990, 1999; Yasuda, 1999, 2001a,b,c, 2007, 2008a,b, 2009; Kawakatsu, 2006), all of those publications attempt to provide overviews of the authors' thinking on key issues and were thus assessed as representative of the genre.

Figure 1. Representation of periods of Japanese history in eco-nativist writings. Data combines text searches of PDFs (Kawakatsu, 2006; Yasuda, 2007, 2008a,b, 2009) with hand tallies from short texts (Umehara, 1989, 1990, 1999; Yasuda, 1999, 2001a,b,c).

The absence of the Kofun in eco-nativist discourse is striking because archaeology functions as a “symbolic communication medium” in support of narratives of the modern nation, in particular in attempts to de-paradoxise the artificiality of the nation-state (Mizoguchi, 2006, p. 55, 57). If the Japanese “emperor and the imperial family [serve] as the ‘symbol of the integration of the nation' and, more importantly, the symbol and embodiment of the continuous existence of the Japanese ethnie” (Mizoguchi, 2006, p. 58–59), then we would expect the Kofun period—when the political system underlying the emperor system began to be established—to form an important element in the debates. Although Japanese eco-nativist writers generally support the emperor system (e.g, Umehara, 1990), the Kofun and Nara periods of early state formation receive little attention in their writings.

Ian Glover noted how nationalist archaeologies developed in many countries “where native peoples appear to be denied the right to their cultural identity”. In such cases “Nationalist archaeology tends to emphasize the more recent past, and to draw attention to visible, monumental architecture and centralized political structures. Earlier prehistory, or the archaeology of small-scale preliterate communities, tends to be ignored by nationalist archaeology” (Glover, 2003, p. 17). Japan initially followed this same trajectory and archaeologists focused primarily on the Kofun and early historic Nara eras. However, controls over academic research under fascist rule soon began to influence debate. Koji Mizoguchi has discussed the Kofun period as a “dangerous” domain of discourse in Japanese archaeology, especially during the period before 1945. By this he means that, in contrast to the “safe” domain of the Stone Age/Jōmon, which was the time of the aboriginal inhabitants of the land, the Yayoi and Kofun eras saw the beginnings of rice-cultivation and, most importantly, the imperial family. The latter periods were therefore “dangerous” in the sense that their study could potentially cast “doubt on the authenticity of the narrative of the national body” (Mizoguchi, 2006, p. 65). Japanese eco-nativism has followed this binary discourse, placing emphasis on the “safe” domain of the Jōmon while circumventing the Kofun. Nevertheless, a major difference is the way the genre has shifted aspects of the Yayoi into the safe domain.

We suggest three specific reasons why the Kofun has largely been avoided by eco-nativist writers. The first derives from Umehara's (1990) definition of Japanese culture as the synthesis of the “harmonious opposition of two focal points, the forest culture that is Jōmon and the paddy field culture that is Yayoi.” In the Kofun period, Umehara argues, the “Yayoi people conquered the Jōmon people and formed a unified state in Japan”, but “From the middle of the Heian [794-1185] era warriors (bushi) started to come to the fore. These warriors were originally engaged in hunter-gathering and were almost certainly descendants of the Jōmon.” This latter claim reproduces now outdated ideas about the origins of the bushi originating with Hara (1906) and combines them with Umehara's focus on the Jōmon as one basis of Japanese culture.

In regarding the Kofun as the time when the Yayoi people established a unified state, Umehara eschews discussion of the origins of social inequality in favour of a narrative of ethnic integration and “harmony” (J. wa). This narrative privileges folk tradition over history (cf. Harootunian, 1988). In certain respects, the Kofun can be considered as the “same” as the Yayoi: in other words, both Yayoi and Kofun were a time of political change and shifting social relations in contrast to the more static/timeless Jōmon (Mizoguchi, 2002, p. 31–38; Hudson, 2018, p. 163; Hudson et al., 2025, Table 1). Instead of this political/historical dynamism, however, both Umehara and Yasuda emphasise the folk or “timeless” aspects of the Yayoi and its rice-farming lifestyle. Umehara (1990) insists that Japan has always been a highly egalitarian society due to its Jōmon roots. The “evidence” presented for this claim is so superficial as to be almost farcical.4 Yet the underlying assumption is that social equality—based on what Haga (2021) called “honest poverty”—provides a way to avoid over-exploitation of the natural environment. (Umehara 1987, 1990) argued that both the Jōmon and Tokugawa periods were based on equality, a striking proposal when archaeologists were increasingly engaged with issues of Jōmon social complexity (cf. Habu, 2004) and a claim clearly contradicted by the highly hierarchical society of the Tokugawa. Umehara (1990) nevertheless insists that “The shallow roots of the Edo [Tokugawa period] status system meant that it was easily destroyed under the influence of Western democratic philosophy in the Meiji period.” For Umehara it is the integration of Jōmon and Yayoi elements that re-centres Japanese culture towards egalitarianism. Nevertheless, a moralistic side to these writings attempts to camouflage the wealth and consumption of the elites. Sociologist Chie (Nakane 1990, p. 231) argued that “the Tokugawa social system encouraged those on the bottom to strive to better themselves and thereby raised the general sophistication of the masses.” The essential contradiction is displayed by Haga (2021) who, while praising “honest poverty”, revels in the extravagance and hedonism of 18th-century Edo with its brothels and courtesans financed by the wealth of a growing merchant class. If Tokugawa Japan can be described as sustainable because it limited consumption (Vries and Vries, 2020, p. 178), it was primarily the lower classes who bore the brunt of the social limits.

A third explanation for the lack of interest in the Kofun in Japanese eco-nativism relates to isolation. The valorisation of the Jōmon and Tokugawa periods as lodestars of past sustainability brings to the forefront questions of isolation and system limits. Despite extensive evidence for contact between Japan and the mainland during the Jōmon (e.g., Kikuchi, 1986; Bausch, 2017), the idea that the Jōmon world was isolated derives from the view that the period “seemed rather unchanging, perhaps even stagnant” until as late as the 1st millennium BC (Kobayashi, 2004, p. 1). A common image of the Jōmon in Japanese archaeology has been of a static and “timeless” society (Mizoguchi, 2006, p. 139), hence a “traditional” and “authentic” expression of Japanese identity.

The word “seclusion” is perhaps more appropriate for the Tokugawa. Seclusion was one key to the political success of the Tokugawa regime, which rarely tired of emphasising supposed threats from the outside. Limits on overseas contacts may have helped protect Japan from bubonic plague and from the full impacts of the violent transition between the Ming and Qing dynasties in China (Parker, 2013, p. 484–506). The putative link between Tokugawa seclusion and sustainability is summarised by (Richards 2003, p. 149), who claims Tokugawa controls on foreign relations “forced the Japanese to consider their lands and natural resources as finite and limited”, encouraging or necessitating a “minimalist, conservationist use of materials and the land.” The extent to which Tokugawa restrictions on overseas travel resulted in a new view of national resources as “finite and limited” is moot because Tokugawa Japan was in fact expanding its mercantile exploitation of resources beyond the “home islands” into Hokkaido, Sakhalin, the Kurils and the Ryukyus (Howell, 1995; Morris-Suzuki, 2013; Totman, 1993). Historians of Japan sometimes point to supposed social benefits of isolation, arguing that Tokugawa seclusion initially brought stability to a previously volatile country (Cullen, 2003). By the early 18th century, however, Japan was in a slow-burning crisis (Lieberman, 2009, p. 457–493), necessitating “maximising the existing resource base” (Totman, 1993, p. 260). Seclusion, in other words, led to new limits on economic growth. While Ochiai (2007) emphasises how Tokugawa Japan can be modelled as a “closed” ecological system reliant only on solar energy, over-exploitation of woodlands led to growing reliance on coal mined in northern Kyushu from the late 17th century. Despite complaints about pollution caused by burning coal, its use expanded over the 18th and 19th centuries (Totman, 1993, p. 271–272).

4.1 Kofun culture and the “Great East Asian Fertile Triangle”

One exception to the rule that Japanese eco-nativism has avoided discussion of the Kofun period relates to Yasuda's (2008a) theory of a “Great East Asian Fertile Triangle”. While Yasuda and Umehara's Jōmon “forest civilisation” might plausibly be linked with the original inhabitants of the Japanese archipelago, it is clear that rice cultivation arrived much later and ultimately from China. The “Great East Asian Fertile Triangle” purports to track the spread of wet-rice cultivating and fishing cultures from the Yangtze to Southeast Asia and then north to Japan. Yasuda argues that climate change, especially that associated with the so-called 4.2 k Event, led to the southward expansion of wheat and millet cultivating pastoral people, pushing rice farmers further into Southeast Asia as well as to Japan in the Yayoi period (see also Yasuda, 2008a,b). This narrative allows Yasuda to portray the Japanese and other rice-farming/fishing peoples in southern East Asia as victims of oppression:

The 4,000-year-long history of East Asia is mainly that of the domination and oppression of the peripheral ethnic minority tribes by the wheat/barley/millet-cultivating pastoral people, the ancestors of the Han [north Chinese] people … The rice-cultivating piscatory people in the peripheral regions including Japan have repeatedly been oppressed and have suffered at the hands of the Han people during their runaway appetite stages. …

But now, the rice-cultivating piscatory people have nowhere left to flee. If another similar mass migration event of the wheat/barley/millet-cultivating people were to occur in the twenty-first century, the rice-cultivating piscatory people will have no choice but to perish. …

(…)

In this age of the expansion-and-conflict-appetite stage of the wheat/barley/millet-cultivating pastoral civilisation, the existence of a different type of civilisation is gradually revealing itself. It is the civilisation of the rice-cultivating piscatory civilisation that has been nurtured in the … Great East Asian Fertile Triangle … and that has led a sustainable lifestyle for more than 10,000 years in the region by maintaining the biodiversity of the environment and without turning the land into a desert (Yasuda, 2013b, p. 462–464).

These quite remarkable claims attempt a fundamental redefinition of what might be considered as “colonial” and “Indigenous/native”. Instead of the traditional emphasis on Euro-American colonialism after 1500—and thus, by extension, Japan's own modern empire—we are presented with a much deeper narrative of oppression stretching back 4000 years or more, and based on subsistence economy and the appropriation of land use. However, Yasuda's time depth of “more than 10,000 years” for a “rice-cultivating piscatory civilisation” is not supported by the archaeological record which traces a gradual adoption of rice cultivation in China and the earliest carp aquaculture at around 8000 BP (Fuller, 2011; Nakajima et al., 2019).

Yasuda's “Great East Asian Fertile Triangle” attempts to re-evaluate the role of China in the historical evolution of Japan. Anti-Chinese sentiment formed an important element of the nativist Kokugaku movement from the late 18th century (Harootunian, 1988). While archaeology in post-colonial Vietnam developed in strong opposition to Chinese rule during the Han dynasty (Glover, 1999, 2003, p. 19–21), early post-war Japanese historians such as Toma (1951) explored how ancient Japan had managed to establish a state on the periphery of the Chinese empire. In Toma's writings it was clear that this problématique reflected contemporary concerns over how Japan should respond to American imperialism (Mizoguchi, 2006, p. 72). Yasuda re-imagined this debate by dividing China into two: the wheat/millet cultivating zone of the north and the rice farming zone of the south.

Within this framework, the Kofun period is mentioned by Yasuda in two different and essentially contradictory ways. In addition to subsistence—the rice farming and fishing of the southern zone—Yasuda proposes a range of mythological and symbolic features linking the cultures of the “Great East Asian Fertile Triangle”. Worship of the sun, mountains, pillars, jades, birds and snakes are suggested as the primary such ideological features. Recalling the hyper-diffusionist Kulturkreise theories of early 20th century ethnology, Yasuda's claims are unconvincing and cannot distract us here.5 Nevertheless, it seems appropriate to briefly discuss Yasuda's proposal that sun and serpent iconography is also found in Kofun tombs in Japan. (Yasuda 2013a, p. 443) shows purported examples of “sun” and “serpent” motifs from three decorated Kofun tombs in Kyushu. These motifs have a long and complex history of interpretation. The circular motifs have commonly been associated with bronze mirrors (Hamada, 1917), although the sun is another interpretation (Hamada, 1919), as is a purely decorative function (Kusaka, 1978). The symbolism may have changed over time and a contextual analysis of each tomb is needed to evaluate various interpretations. The serial triangles that Yasuda links with a serpent based on an ethnographic parallel with Taiwan is another very complex motif, but we are aware of only one previous identification with an animal (Saitō, 1989). Today, the most widely-accepted theories propose that triangles had an apotropaic function of containing the soul, or were mere decorations (Kawano, 2023). There is a possibility that the triangle could be associated with so-called “snake arrowheads”, both because of the shape and because they are often found in large numbers as Kofun grave goods. However, we do not support this interpretation for four reasons: (1) Lack of cultural and associative context: Yasuda discusses the triangles without reference to other categories of Kofun material culture; (2) Iconographic arrangement: Yasuda speaks of “triangles” but the decorated tombs he mentions have at least three distinct iconographies of the triangle. Moreover, there are different visual strategies in which the triangle is clearly reproduced in different ways; (3) Presence alongside other iconographies: the triangle is by far the most frequent iconography and is mainly reproduced in “full surface” display mode, meaning it was effectively the background; (4) Animal iconography: Although highly stylised, animals are represented both in Kofun-period decorated tombs and in the Yayoi period. It is therefore unclear why only the serpent should have been represented with a symbol (triangle). Moreover, there is a serpent depiction in the Takehara tomb, namely the turtle surrounded by a serpent at the entrance (Kusaka, 1978; Mori, 1985). In summary, triangles and circles are among the most widespread shapes in prehistoric and protohistoric societies precisely because of their simplicity. In the case of Kofun Japan, there seems to be no contextual evidence that would allow us to link these motifs with a “Great East Asian Fertile Triangle”.

4.2 Climate change and the “Kofun Cold Stage”

The second context in which the Kofun period is mentioned in Yasuda (2013a) relates to his claim that climatic deterioration after AD 240 led to the transition from Yayoi to Kofun. The existence of a “Kofun Cold Stage” dating from AD 240–732 was proposed by Sakaguchi (1983) and in broad terms can be linked with the so-called Late Antique Little Ice Age (cf. Büntgen et al., 2016; Zonneveld et al., 2024). In Yasuda's (2013a, p. 455) interpretation, the climatic “turbulence triggered another wave of mass migrations from China to Southeast Asia and to the Japanese archipelago via the Korean peninsula.” While historical, archaeological and DNA evidence support continued immigration into Japan during the Kofun era (Hirano, 1977; Cooke et al., 2021), the links were primarily with Korea and Northeast Asia rather than the area of Yasuda's so-called “Great East Asian Fertile Triangle”. Texts such as the Nihon shoki (720) mention the arrival of immigrants from the Korean states of Paekche and Silla but there is little or no historical evidence for immigration from southern China to Japan at this time.

5 Conclusions

There is no single native or Indigenous ecology, but a feature commonly discussed under that rubric is a grounding in place and its problems—a land ethnic that connects people to where they live (Schweninger, 2008). What we have here termed Japanese eco-nativism presents an escapist, utopian vision that displays little concern with the actual lived experience of most contemporary Japanese.6 The oppositional desire of the genre encourages a nostalgia for an imagined, romanticised past. The land or place of Japan appears as an idealised fūdo (“cultural landscape”) that, following Watsuji's (1961) original conception, is linked to imagined climatic/cultural zones termed “civilisations”. Despite the salvationist claims reflected in titles such as “Environmental archaeology can save the earth and humanity” (Yasuda, 1999), concrete policy is rarely considered in the genre, although the writings have had some influence on government documents and school textbooks (Hudson et al., 2022, 2025). The assumption, often implicit, is that Japan forms a “natural community” in harmony with Nature and that the world's problems could be solved if only everyone else would somehow become more Japanese. In this way Japanese eco-nativism suggests beguilingly simple answers to highly complex and, in many cases, so-called “wicked” problems (cf. Dome and Yamazaki, 2022; Schofield, 2024). The genre does not consider social differences within a Japanese society that is increasingly beset by a range of social crises (cf. Allison, 2013). The assumption that all Japanese form one big “natural community” means there is no explicit acknowledgement of the relationship between archaeological and other knowledge/stakeholder communities (cf. Smith and Waterton, 2009). We have argued here that this problem is reflected in the way Japanese eco-nativism has almost entirely avoided discussion of the Kofun era of early state formation, showing the difficulty of incorporating narratives of social inequality into the utopian eco-nativist genre. We conclude that this selective use of the Japanese past is ultimately inconsistent with an Indigenous or native environmentalism.

Is it possible to identify any broader implications from the present study with respect to the theme of “Indigenous Perspectives on Environmental Archaeology”? Notwithstanding the eco-nativist claims discussed above, there is no question that all past societies engaged in strategies to maintain sustainability—even if the longer-term goals were understood at different scales (cf. Harkin and Lewis, 2007). Those strategies often became truncated by modernity and especially by the Great Acceleration of the post-Second War World War era (McNeill and Engelke, 2014). Nevertheless—and in contrast to eco-nativist claims of exceptionalism—shared histories of past sustainability hold great promise for generating what Kehnel (2024, p. 4) calls a “collective imagination” in the face of climate and other ecological threats. This does not mean that mediaeval let alone Neolithic environmental strategies can be directly applied to the contemporary world. Rather, it provides a way for human societies to imagine a shared past and thus the possibility of a shared future.

In making these comments we do not mean to imply that Indigeneity is unimportant. The divide between coloniser and colonised continues to shape the modern world. As we have seen, this divide impacts the ways in which environmental issues are approched in Japan (see also Hudson, 2018). Yet the experience of modernity in Japan also draws our attention to another series of contrasts and contradictions in which Japan is both modern and traditional, rural and urban, rooted in native place and yet socially fluid. The co-existence of different layers of historical experience has been a key theme of Japanese letters for over a century (Harootunian, 2000; Hudson, 2021). In our evaluation, therefore, an important question for future work is how histories of sustainability and environmentalism in the Japanese Islands can be inserted into a past that is both native and non-native.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MH: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization. CZ: Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was conducted with the support of the Language and the Anthropocene Research Group at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology.

Acknowledgments

We thank the two reviewers for their helpful comments.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fearc.2025.1697454/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Although we coined the term “eco-nativist” without conscious reference to earlier literature, we later discovered that the word has been used by other scholars such as (Pešić and Vukelić 2025).

2. ^This was initially published in 1978 as a long article in Science Reports of the Tohoku University, 7th series (Geography), 28(2), 117–281 but was reprinted the same year as a separate monograph. The monograph retains the pagination of the original article.

3. ^Previous work on the geographical distribution of milking is not cited by Yasuda. In his classic study, Simoons (1970) had noted that research on the distribution of milking can be traced back to at least the 1890s.

4. ^Umehara (1990) cites the work of Tsuneo Iida (e.g., 1992) on egalitarianism in modern Japanese companies, but also writes “That Japan is an egalitarian society can be determined from the faces of her prime ministers. … it is rumoured that if you have an aristocratic face and are too intellectual you will never become prime minister!”

5. ^Yasuda's concept of a “Great East Asian Fertile Triangle” bears strong similarities with the “ethnic culture complexes” proposed by ethnologist Masao Oka (1898–1982) in his University of Vienna doctoral dissertation in 1934 (see Obayashi, 1991, p. 3–5). Yasuda's emphasis on sun worship also recalls Grafton Elliot Smith's (1915) writings on the diffusion of heliolithic culture (cf. McNiven and Russell, 2005, p. 165–173).

6. ^One reviewer of this paper pointed out that this has never been an interest of the eco-nativist/eco-nationalist genre. It would be more precise, however, to say that the genre has frequently presented itself as somehow representative of the struggles of an ordinary Japan to find its place in the world. Like the ecología real (“real ecology”) of the far-right Vox party in Spain (Ungureanu and Popartan, 2024), Japanese eco-nativism makes skillful use of open signifiers connected to traditional, rural life. For further discussion of this comparison with Vox, see Hudson et al. (2025).

References

Akazawa, T. (1972). Report of the Investigation of the Kamitakatsu Shell-Midden Site. Tokyo: Bulletin of the Tokyo University Museum, 4.

Armiero, M. (2011). A Rugged Nation: Mountains and the Making of Modern Italy. Cambridge: White Horse Press.

Barnes, G. L. (2007). State Formation in Japan: Emergence of a 4th-Century Ruling Elite. Abingdon: Routledge.

Bausch, I. (2017). “Prehistoric networks across the Korea strait (5000-1000 BCE): “Early globalization” during the Jomon period in northwest Kyushu?,” in The Routledge Handbook of Archaeology and Globalization, ed T. Hodos (London: Routledge), 413–437.

Bhabha, H. (1984). Of mimicry and man: the ambivalence of colonial discourse. October 28, 125–133. doi: 10.2307/778467

Büntgen, U., Myglan, V. S., Ljungqvist, F. C., et al. (2016). Cooling and societal change during the Late Antique Little Ice age from 536 to around 660 AD. Nat. Geosci. 9, 231–236. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2652

Burns, S.L. (2003). Before the Nation: Kokugaku and the Imagining of Community in Early Modern Japan. Durham NC: Duke University Press.

Buruma, I. (1987). The right argument: preserving the past to reclaim Japanese ‘supremacy'. Far Eastern Econ. Rev. 19, 82–85.

Conversi, D. (2020). The ultimate challenge: nationalism and climate change. National. Pap. 48, 625–636. doi: 10.1017/nps.2020.18

Cooke, N. P., Mattiangeli, V., and Cassidy, L. M. (2021). Ancient genomics reveals tripartite origins of Japanese populations. Sci. Adv. 7:eabh2419. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abh2419

Cullen, L. M. (2003). A History of Japan, 1582–1941: Internal and External Worlds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Denham, T. (2024). Grand challenge: environmental archaeology as intersectional, translational and inclusive practice. Front. Environ. Archaeol. 3, 1365794.

Dome, T., and Yamazaki, G. (eds.), (2022). Yakkai na mondai wa minna de toku. Kyoto: Sekai Shisosha.

Droz, L., Fricke, M. F., Heroor, N., et al. (2025). Environmental philosophy in Asia: between eco-orientalism and ecological nationalisms. Environ. Values 34, 84–108. doi: 10.1177/09632719241276999

Echoes Zuccarelli Freire, V., Ziegler, M. J., Caetano-Andrade, V., and Iminjili, V. (2024). Addressing the Anthropocene from the global south: integrating paleoecology, archaeology and traditional knowledge for COP engagement. Front. Earth. Sci. 12:e1470577. doi: 10.3389/feart.2024.1470577

Elliot Smith, G. (1915). The Migrations of Early Culture: A Study of the Significance of the Geographical Distribution of the Practice of Mummification as Evidence of the Migrations of Peoples and the Spread of Certain Customs and Beliefs. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Fabian, J. (1983). Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Fuller, D. Q. (2011). Pathways to Asian civilizations: tracing the origins and spread of rice and rice cultures. Rice 4, 78–92. doi: 10.1007/s12284-011-9078-7

Glover, I. C. (1999). Letting the past serve the present—some contemporary uees of archaeology in Viet Nam. Antiquity 73, 594–602. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00065169

Glover, I. C. (2003). National and political uses of archaeology in South-east Asia. Indones. Malay World 31, 16–30. doi: 10.1080/13639810304439

Habu, J., and Fawcett, C. (1999). Jomon archaeology and the representation of Japanese origins. Antiquity 73, 587–593. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00065157

Habu, J., and Fawcett, C. (2008). “Science or narratives? Multiple interpretations of the Sannai Maruyama site, Japan,” in Evaluating Multiple Narratives: Beyond Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist Archaeologies, eds J. Habu, C. Fawcett, and J. M. Matsunaga (Cham: Springer), 91–117.

Haga, T. (2021). Pax Tokugawana: The Cultural Flowering of Japan, 1603-1853. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

Hamada, K. (1917). Higo ni okeru soshoku aru kofun oyobi yokoana. Kyoto Teikoku Daigaku Bunka Daigaku Kokugaku Kenkyu Hokoku

Hamada, K. (1919). Kyushu ni okeru soshoku kofun. Kyoto Teikoku Daigaku Bunka Daigaku Kokugaku Kenkyu Hokoku (Res. Rep. Archaeol., Univ. Arts & Sci., Imperial Univ. Kyoto) 3, 1–55.

Hanihara, K. (1991). Dual structure model for the population history of the Japanese. Jpn. Rev. 2, 1–33.

Harkin, M. E., and Lewis, D. R. (2007). “Introduction,” in Native Americans and the Environment: Perspectives on the Ecological Indian, eds M. E. Harkin, and D. R. Lewis (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press), xix–xxxiv.

Harootunian, H. (1988). Things Seen and Unseen: Discourse and Ideology in Tokugawa Nativism. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Harootunian, H. (2000). Overcome by Modernity: History, Culture, and Community in Interwar Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Higuchi, T. (2015). “Japan as an organic empire: commercial fertilizers, nitrogen supply, and Japan's core-peripheral relationship”, in Environment and society in the Japanese Islands: from prehistory to the present, eds. B. L. Batten and P. C. Brown (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press), 139–157.

Hirano, K. (1977). The Yamato state and Korea in the fourth and fifth centuries. Acta Asiatica 31, 51–82.

Howell, D. L. (1995). Capitalism from Within: Economy, Society and the State in a Japanese Fishery. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hudson, M. (1999). Ruins of Identity: Ethnogenesis in the Japanese Islands. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Hudson, M. (2018). “Global environmental justice and the natural environment in Japanese archaeology,” in Multidisciplinary Studies of the Environment and Civilization: Japanese Perspectives, eds Y. Yasuda, and M. Hudson (Abingdon: Routledge), 159–181.

Hudson, M. (2021). Conjuring up Prehistory: Landscape and the Archaic in Japanese Nationalism. Oxford: Archaeo Press.

Hudson, M. (2022). Re-thinking Jomon and Ainu in Japanese history. Jpn. Focus 20:e5725. doi: 10.1017/S1557466022019143

Hudson, M., lewallen, A-E., and Watson, M., (eds.) (2013). Beyond Ainu Studies: Changing Academic and Public Perspectives. Honolulu: Hawai‘i University Press.

Hudson, M., Nakagome, S., and Whitman, J. B. (2020). The evolving Japanese: the dual structure hypothesis at 30. Evol. Hum. Sci. 2:e6. doi: 10.1017/ehs.2020.6

Hudson, M., Uchiyama, J., Lindström, K., Kawashima, T., and Reader, I. (2022). Global processes of anthropogenesis characterise the early Anthropocene in the Japanese Islands. Hum. Soc. Sci. Comm. 9:e84. doi: 10.1057/s41599-022-01094-8

Hudson, M., Uchiyama, J., Lindström, K., and Šukelj, K. (2025). A deep genealogy of Japanese green nationalism from the long nineteenth century to the present. Front. Hum. Dyn. 7:1638653. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2025.1638653

Hung, K.-C. (2015). “When the green archipelago encountered Formosa: the making of modern forestry in Taiwan under Japan's colonial rule (1895–1945)”, in Environment and society in the Japanese Islands: from prehistory to the present, eds. B.L. Batten and P.C. Brown (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press), 174–193.

Iida, T. (1992). On the egalitarian aspects of the Japanese economy and society. Japan Rev. 3, 141–148.

Kalland, A., and Asquith, P. J. (1997). “Japanese perceptions of nature: ideals and illusions,” in Japanese Images of Nature: Cultural Perspectives, eds P. J. Asquith, and A. Kalland (London: Curzon), 1–35.

Kawakatsu, H. (2006). “Toward a civilization based on beauty, from civilizations based on truth and goodness,” in Cultural Diversity and Transversal Values: East-West Dialogue on Spiritual and Secular Dynamics, ed UNESCO (Paris: UNESCO), 84–89.

Kikuchi, T. (1986). “Continental culture and Hokkaido,” in Windows on the Japanese Past: Studies in Archaeology and Prehistory, eds. R. J. Pearson, G. L. Barnes, and K. L. Hutterer (Ann Arbor, IL: Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan), 149–162.

Kishinouye, K. (1909-11). Prehistoric fishing in Japan. J. College Agricult. Imperial Univ. Tokyo 2.

Kobayashi, T. (2004). Jomon Reflections: Forager Life and Culture in the Prehistoric Japanese Archipelago. Oxford: Oxbow.

Koike, H. (1973). Daily growth lines of the clam Meretrix lusoria. J. Anthropol. Soc. Nippon. 81, 122–138.

Koike, H. (1979). Seasonal dating and valve-pairing technique in shell midden analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 6, 63–74. doi: 10.1016/0305-4403(79)90033-5

Kotani, Y. (1972). Economic Bases During the Later Jomon Periods in Kyushu, Japan: A Reconsideration (Ph.D. dissertation), Madison: University of Wisconsin.

Kuwayama, T. (2004). Native Anthropology: The Japanese Challenge to Western Academic Hegemony. Melbourne, VIC: Trans Pacific Press.

Lieberman, V. (2009). Strange Parallels. Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830, Volume 2: Mainland Mirrors: Europe, Japan, China, China, South Asia and the Islands. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Lindström, K. (2019). Classic and cute: framing biodiversity in Japan through rural landscapes and mascot characters. Pop. Comm. 17, 233–251. doi: 10.1080/15405702.2019.1567735

Maruyama, M. (1974). Studies in the Intellectual History of Tokugawa Japan. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

McNeill, J. R., and Engelke, P. (2014). The Great Acceleration: An Environmental History of the Anthropocene since 1945. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

McNiven, I. J., and Russell, L. (2005). Appropriated Pasts: Indigenous Peoples and the Colonial Culture of Archaeology. Lanham: Altamira Press.

Mizoguchi, K. (2002). An Archaeological History of Japan, 30,000 BC to AD 700. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Mizoguchi, K. (2006). Archaeology, Society and Identity in Modern Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Morris-Suzuki, T. (2013). The nature of empire: forest ecology, colonialism and survival politics in Japan's imperial order. Japan. Stud. 33, 225–242. doi: 10.1080/10371397.2013.845084

Morse, E. S. (1879). The Shell Mound of Oomori. Memoirs of the Science Department, University of Tokyo, 1.

Nakajima, T., Hudson, M., Uchiyama, J., Makibayashi, K., and Zhang, J. (2019). Common carp aquaculture in Neolithic China dates back 8,000 years. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1415–1418. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0974-3

Nakane, C. (1990). “Tokugawa society”, in Tokugawa Japan: the social and economic antecedents of modern Japan, eds. C. Nakane and S. Ōishi (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press) p. 213–240.

Nishida, M. (1973). On the charcoal analysis. J. Anthropol. Soc. Nippon 81, 277–285 (in Japanese with English summary). doi: 10.1537/ase1911.81.277

Nishimura, S. (1991). The way of the gods: Motoori Norinaga's Naobi no mitama. Monum. Nippon. 46, 21–41. doi: 10.2307/2385145

Obayashi, T. (1991). The ethnological study of Japan's ethnic culture: a historical survey. Acta Asiatica 61, 1–23.

Ochiai, E. (2007). Japan in the Edo period: global implications of a model of sustainability. Japan Focus 5:e2346. doi: 10.1017/S155746600702030X

Oka, K. (2008). Miezaru mori no kurashi: Kitakami sanchi, mura no minzoku seitaishi. Tokyo: Taiga Shuppan.

Parker, G. (2013). Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Pešić, J., and Vukelić, J. (2025). “Transnationalization vs. eco-nationalism: discursive framing of environmental struggles in Serbia,” in Contentious Politics in the Transnational Arena: Political Contention in Europe and its Wider Neighbourhood, eds. C. Milan, and A. Buzogány (Palgrave), 101–122.

Prohl, I. (2000). Die “Spirituellen Intellektuellen“ und das New Age in Japan. Hamburg: Gesellschaft für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens.

Reader, I. (1990). The animism renaissance reconsidered: an urgent response to Dr Yasuda. Nichibunken Newslett. 6, 14–16.

Reitan, R. (2017). Ecology and Japanese history: reactionary environmentalism's troubled relationship with the past. Japan Focus 15:e5007. doi: 10.1017/S1557466017013298

Richards, J. F. (2003). The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Robbeets, M., Bouckaert, R., and Conte, M. (2021) Triangulation supports agricultural spread of the Transeurasian languages. Nature 599, 616–621.

Rots, A. P. (2017). Shinto, Nature and Ideology in Contemporary Japan: Making Sacred Forests. London: Bloomsbury.

Runjić, T. N., Jug-Dujaković, M., Runjić, M., and Łuczaj, Ł. (2024). Wild edible plants used in Dalmatian Zagora (Croatia). Plants 13:e1079. doi: 10.3390/plants13081079

Sakaguchi, Y. (1983). Warm and cold stages in the past 7600 years in Japan and their global correlation: especially on climatic impacts to the global sea level changes and the ancient Japanese history. Bull. Dept. Geog. Univ. Tokyo 15, 1–31.

Sasaki, K. (2017). “The Kofun era and early state formation,” in Routledge Handbook of Premodern Japanese History, ed K.F. Friday (London: Routledge), 68–81.

Schofield, J. (2024). Wicked Problems for Archaeologists: Heritage as Transformative Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schweninger, L. (2008). Listening to the Land: Native American Literary Responses to the Landscape. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Simoons, F. J. (1970). The traditional limits of milking and milk use in southern Asia. Anthropos 65, 547–593.

Stock, P. (2023). The idea of Asia in British geographical thought, 1652-1832. Trans. R. Hist. Soc. 1, 121–144. doi: 10.1017/S0080440123000026

Sugimoto, Y. (1999). Making sense of Nihonjinron. Thesis Eleven 57, 81–96. doi: 10.1177/0725513699057000007

Sun, W., and Zancan, C. (2024). Showcasing Japan: a journey of Japanese identity through archaeology and ancient art exhibitions in Italy. Ann. Ca' Foscari. Serie Orient. 60, 333–366. doi: 10.30687/AnnOr/2385-3042/2024/01/014

Sylvain, R. (2002). Land, water and truth: San identity and global Indigenism. Am. Anthropol. 104, 1074–1085.

Thomas, J. A. (2001). Reconfiguring Modernity: Concepts of Nature in Japanese Political Ideology. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Toma, S. (1951). “Eiyu jidai,” in Rekishigaku no seika to kadai, Vol. 2, ed Rekishigaku Kenkyukai (Tokyo: Iwanami), 16–20.

Tsukada, M. (1986). “Vegetation in prehistoric Japan: the last 20,000 years,” in Windows on the Japanese Past: Studies in Archaeology and Prehistory, eds R. J. Pearson, G. L. Barnes, and K. L. Hutterer (Ann Arbor, IL: Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan), 11–56.

Umehara, T. (1984). “Nihon bunka no teiryu: Ainu to Nihon,” in Nihonjin wa doko kara kita ka, ed K. Hanihara (Tokyo: Shogakukan), 159–176.

Umehara, T. (1989). “Japan's pride,” in Japan and Europe: Changing Contexts and Perspectives. In What Ways Can Japan's and Europe's New Cultures Make a Contribution to the Shaping of a Notion of World Culture?, ed C. A. Marbaix (Brussels: Seiko Epson Corporation), 101–113.

Umehara, T. (1990). “Nihon to wa nan na no ka: Nihon kenkyu no kokusaika to Nihon bunka no honshitsu,” in Nihon to wa nan na no ka: kokusaika no tadanaka de, ed T. Umehara (Tokyo: NHK Books), 6–20. Translated by M. Hudson (2007) as ‘What is Japan? The internationalization of Japanese studies and the essence of Japanese culture', Rekishi Jinrui (Tsukuba) 35, 174-184.

Umehara, T. (1999). The civilization of the forest. NPQ Special Issue. 16, 40–48. doi: 10.1111/0893-7850.00224

Ungureanu, C., and Popartan, L. A. (2024). The green, green grass of the nation: a new far-right ecology in Spain. Polit. Geog. 108:e102953. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2023.102953

Viazzo, P. P. (1989). Upland Communities: Environment, Population and Social Structure in the Alps since the Sixteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vries, P., and Vries, A. (2020). Atlas of Material Life: Northwestern Europe and East Asia, 15th to 19th century. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

Watkins, J. (2005). Through wary eyes: indigenous perspectives on archaeology. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 34, 429–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120540

Watsuji, T. (1961). A Climate: A Philosophical Study. Translated by G. Bownas. Tokyo: Printing Bureau, Japanese Government.

Yasuda, Y. (1978). Prehistoric Environment in Japan: Palynological Approach. Sendai: Institute of Geography, Faculty of Science, Tohoku University.

Yasuda, Y. (1999). “Kankyo kokogaku ga chikyu to jinrui o suku,” in Hajimete deau Nihon kokogaku, ed Y. Yasuda (Tokyo: Yuhikaku), 3–42.

Yasuda, Y. (2001a). “Comparative study of the myths and history of a cedar forest each in East and West Asia,” in Forest and Civilisations, ed Y. Yasuda (New Dehli: Roli Books/Lustre Press), 13–40.

Yasuda, Y. (2001b). “Eyes of the forest gods,” in Forest and Civilisations, ed Y. Yasuda (New Dehli: Roli Books/Lustre Press), 105–120.

Yasuda, Y. (2001c). “Forest and civilisations,” in Forest and Civilisations, ed Y. Yasuda (New Dehli: Roli Books/Lustre Press), 171–192.

Yasuda, Y. (2006). “Sustainability as viewed from an ethos of rice cultivation and fishing,” in Cultural Diversity and Transversal Values: East-West Dialogue on Spiritual and Secular Dynamics, ed UNESCO (Paris: UNESCO), 106–110.

Yasuda, Y. (2008b). Climate change and the origin and development of rice cultivation in the Yangtze River Basin, China. Ambio 37, 502–506. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-37.sp14.502

Yasuda, Y. (2009). Proposed solution rooted in Japanese civilization for global environmental problems. Kikan Seisaku/Keiei Kenkyu (Quart. J. Public Policy and Management) 4, 50–59 (in Japanese with English summary). Available online at: https://www.murc.jp/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/qj0904_04.pdf

Yasuda, Y. (2010). “Sustainability from the perspective of environmental archaeology,” in Balancing Nature and Civilization: Alternative Sustainability Perspectives from Philosophy to Practice, eds Y. Hayashi, M. Morisugi, and S. Iwamatsu (Cham: Springer), 33–50.

Yasuda, Y. (2013a). “Epilogue: the decline of civilization,” in Water Civilization: From Yangtze to Khmer Civilizations, ed. Y. Yasuda (Tokyo: Springer), 459–464.

Yasuda, Y. (2015). Miruku o nomanai bunmei: kan-taiheiyo to inasaku-gyoromin no sekai. Tokyo: Yosensha.

Yoshida, Y., and Ertl, J. (2016). Archaeological practice and social movements: ethnography of Jomon archaeology and the public. J. Int. Center Cult. Resource Stud. 2, 47–71.

Keywords: eco-nationalism, comparative civilisation theory, history of archaeology, social inequality, Kofun period

Citation: Hudson M and Zancan C (2025) Environmental archaeology and eco-nativist discourse in modern Japan. Front. Environ. Archaeol. 4:1697454. doi: 10.3389/fearc.2025.1697454

Received: 02 September 2025; Accepted: 21 October 2025;

Published: 18 November 2025.

Edited by:

Tim Denham, Australian National University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Anke Hein, University of Oxford, United KingdomGergely Mohácsi, Osaka University, Japan

Copyright © 2025 Hudson and Zancan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mark Hudson, aHVkc29uQGdlYS5tcGcuZGU=

Mark Hudson

Mark Hudson Claudia Zancan

Claudia Zancan