Abstract

Recent advances in biomolecular archaeology have enabled the detection of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and odor-active metabolites in archaeological materials, revealing the scents and olfactory environments of the ancient world. These developments offer new opportunities to reconstruct the sensory worlds of the past through their molecular signatures, from perfumery, ritual and medicinal practices to aspects of daily life. Yet their integration into museums and public cultural heritage initiatives remains limited. This paper explores how biomolecular data on past scents can be transformed into multisensory museum experiences, focusing on the Scent of the Afterlife, an olfactory reproduction based on the biomolecular analysis of a 3,500 year old Egyptian mummification balm. Developed collaboratively by archaeologists, chemists, curators, a perfumer, and an olfactory heritage consultant, the project translated chemical evidence into a historically informed scent. Two museological applications are presented: a scented card for mobile diffusion and a fixed scent station integrated into the exhibition Ancient Egypt-Obsessed with Life at the Moesgaard Museum in Aarhus, Denmark. We argue that olfactory reproductions bridge scientific research and cultural heritage, offering tools for education and public outreach. By situating biomolecular data within sensory and curatorial frameworks, this study outlines a pathway toward a multisensory archaeology.

1 Introduction

Over the past decades, biomolecular archaeology has transformed our ability to investigate the past. Analyses of ancient DNA, proteins, and lipids have revealed hidden dimensions of ancient diets, diseases, mobility, and material practices (Cappellini et al., 2018; Spyrou et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2020; Wilkin et al., 2021; Evershed et al., 2022; Gretzinger et al., 2025). Attention has recently turned to another category of molecular evidence: metabolites and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that can capture the fragrant past (Bembibre and Strlič, 2017; Huber et al., 2022; Brøns, 2025; Paolin et al., 2025). Until recently, archaeological science paid little attention to these small, volatile and often odor-active molecules, largely because their ephemeral nature led to the assumption that they mostly would not survive in archaeological contexts. However, more recently archaeological science has adopted highly sensitive analytical methods, such as VOCs analysis, metabolomics, and gas chromatography–olfactometry (GC-O), demonstrating that even these elusive compounds of ancient materials can be detected and characterized (Badillo-Sanchez et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023; Squires et al., 2024; Hausleiter and Huber, 2025; Orsingher et al., 2025; Paolin et al., 2025). These methods enable the detailed identification of aromatic substances—such as incense, perfumes, resins, and medicinal preparations—and open new avenues for the understanding of rituals, perfume making, healing, sanitation, and cosmetic practices of past societies.

While these breakthroughs deepen opportunities for archaeological interpretation, for instance, by tracing long-distance trade of aromatics (Rageot et al., 2023; Huber et al., 2025a), reconstructing ritual and medicinal practices (Ren et al., 2022; Huber et al., 2025b), or even recovering complex embalming and perfume “recipes” (Evershed and Clark, 2020; Fulcher et al., 2021; Mahan et al., 2025; Orsingher et al., 2025)—they also raise important questions: How can biomolecular data of past scents be transformed into sensory experiences that meaningfully engage the public? What can these biomolecules convey beyond their analytical detection and interpretation, and how might their translation into tangible sensory experiences reshape cultural heritage practice? How can olfactory and other sensory strategies, informed by biomolecular research, be leveraged to increase the educational possibilities of heritage collections and exhibitions?

Recent advances in biomolecular archaeology not only deepen archaeological interpretation but also open new opportunities for the study of olfactory heritage, a relatively young field that highlights the relationship between our sense of smell and cultural heritage (Howes, 2006; Bembibre and Strlič, 2017; Huber et al., 2022; Bembibre et al., 2024). One dimension of this multidisciplinary field is the conservation, interpretation, and presentation of scents in the context of cultural heritage. A practice known as olfactory museology, which investigates how museums employ scent as a medium of storytelling (Howes, 2014; Leemans et al., 2022; Ehrich, 2024). Growing attention to olfactory heritage reveals how smell profoundly shapes visitor engagement, challenging the ocular centric traditions of museological practice (Classen, 2007; Verbeek et al., 2022). Scholarship demonstrates that incorporating scent into exhibitions enhances comprehension, broadens accessibility, strengthens emotional and social connections, and encourages longer, more reflective encounters with artworks (Aggleton and Waskett, 1999; Bembibre and Strlič, 2017; Eardley et al., 2018; Verbeek et al., 2022)1. Inaccessible from visual or textual interpretation alone, olfactory interpretation evokes atmospheres, moods, and lived experiences, enriching exhibitions, improving accessibility, and fostering inclusive participation (Levent and Pascual-Leone, 2014; Verbeek, 2016; Ehrich, 2024). Yet the integration of biomolecular data into the practice of olfactory museology remains in its infancy, and many challenges—methodological, ethical, and practical–remain unresolved.

This article explores the integration of biomolecular research into museum practice from the perspective of olfactory museological design. It examines how molecular data can be transformed into “olfactory reproductions” (defined below) and presented within the context of a museum. Drawing from a case study, we trace the process from laboratory analysis to olfactory interpretation and show two distinct modes of bringing a recreated scent to the public: “scented cards” and “fixed scent stations.” Through this, we present both their set-up and effects on audience engagement, demonstrating how immersive, multisensory experiences can reconnect visitors with the material dimensions of our ancient past. Our interdisciplinary team, comprising archaeologists, museum curators, archaeo-chemists, a perfumer, and an olfactory heritage consultant, explores how biomolecular research of ancient scents can extend beyond archaeological interpretation to inform and enrich public-facing cultural heritage initiatives. Focusing on a case study carried out by our group in 2023 called the Scent of the Afterlife, we illustrate how cross-disciplinary collaborations translate ancient biomolecules into olfactory interpretation for the museum context, and reflect on issues of authenticity, ethics, and the presentation of the scent to the public.

2 From “scent archives” to “olfactory reproductions” and interpretations

At the heart of this convergence lies what we term “scent archives”: the material traces or residues of aromatic substances preserved in archaeological artifacts and contexts, whether absorbed into vessels, deposited on tools, or embedded within organic remains (Huber et al., 2022). These traces, although often invisible to the eye, preserve molecular information that biomolecular analysis can unlock, revealing aromatic substances once used in ritual, medicinal, or everyday contexts. When working with heritage collections and designing olfactory storytelling experiences, museum practitioners and olfactory museologists often look to objects as inspiration for sensory interpretation. Therefore, their perspective of “scent archives” differs from that of archaeological scientists: rather than a material-centered approach, they tend to adopt an object-centered one, positioning collections and narratives as the primary anchors of olfactory meaning and interpretation (e.g., Object-Based Learning initiatives). At the same time, the material emphasis of archaeological scent archives presents valuable opportunities for olfactory museology, making compelling cases for olfactory museological practice and opening new possibilities for public engagement.

The scent archive that inspired the creation of the Scent of the Afterlife is a set of four ancient Egyptian canopic jars belonging to Lady Senetnay2, of which two are now housed at the Museum August Kestner in Hannover, Germany (Dziobek et al., 2009; Loeben, 2009). Canopic jars were essential elements of the mummification ritual: the jars held the embalmed internal organs of the deceased (lungs, stomach, intestines, and liver), which were removed from the body and believed to be required in the afterlife (Ikram, 1998; Germer, 2005). Like the body itself, these organs were preserved with complex balms often enriched with fragrant and resinous substances. We conducted biomolecular analyses of residues that remained inside two of Senetnay's canopic jars, enabling us to reconstruct aspects of the embalming recipe and to identify several aromatic ingredients used in its preparation (see Huber et al., 2023).

Rather than presenting these results solely as a scientific publication, our team translated the data into a scent reproduction of the ancient Egyptian mummification process based on the biomolecular results. Such an “Olfactory Reproduction” is a historically informed scent creation that evokes, preserves, or interprets smells of the past. This may involve recreating extinct aromas, offering imaginative impressions without surviving sources, representing a historical figure's olfactory biography, or translating historical concepts for contemporary audiences (Bembibre, 2021; Ehrich, 2024). Scholarship on how to develop these scents remains limited, posing methodological challenges: for example, considerations for authenticity, creative liberty of the perfumer, as well as how these factors are interpreted and communicated to the public (Marx et al., 2022; Chazot et al., 2023). Creators of olfactory reproductions must recognize that given the evolving nature of fragrant materials and the inherent creative agency of the perfumer, authenticity should be understood as a spectrum rather than an absolute. In our opinion, although trying to be as close to the original scent as possible, these scents are never completely authentic, but rather interpretations informed by historical or biomolecular data, intended as educational tools for public engagement. This is significant, as recreating and presenting past scents creates new opportunities for meaning-making within museum collections and for critically engaging with the past (Kiechle, 2016; Dupré, 2017).

Additionally, because creating an olfactory reproduction is a unique and interdisciplinary process, thorough documentation is essential (Ehrich et al., 2023)3. Detailed records ensure that both the (historical) data and the scent designer's intent are captured. Drawing on approaches developed in projects such as Odeuropa, we prepared a detailed briefing for our perfumer outlining the project's title, timeline archaeological context, historical background, data from the biomolecular analysis, interpretation of the findings (e.g., list of ingredients), intended type of olfactory museological design, and the number of scents to be produced (Ehrich et al., 2023). Using our briefing (see Supplementary material), the perfumer was able to produce our olfactory reproduction.

The Scent of the Afterlife was created in accordance with IFRA guidelines that ensures public safety and regulatory compliance. The scent creation process followed four main stages: (1) the selection and adaptation of raw materials; (2) the formulation of several compositions; (3) iterative evaluation through interdisciplinary dialogue among the perfumer, archaeo-chemist, archaeologist, and olfactory heritage consultant to assess authenticity and interpretive accuracy; and (4) the completion of the final formula and finalizing the scent distribution method.

Over several months, multiple formulations—each comprising approximately 20 ingredients—were tested and refined. Since the materials identified in the chemical analysis of the original balm dated to antiquity, modern olfactory equivalents had to be identified that were both safe for public use and faithful to the biomolecular results. This introduced new challenges for the perfumer who embraced a degree of uncertainty while balancing scientific precision and creative interpretation. This scent development process raises the importance of recognizing that today's raw materials differ from those of the past and that interdisciplinary cooperation is required to capture the ancient past as accurately as possible. The resulting fragrance is a complex creation that evokes the ritual, trade, and symbolic dimensions of Egyptian mummification.

3 Case study: presentation of the Scent of the Afterlife

Despite increased research within the field of olfactory museology, museum practitioners still have a limited understanding for how to accurately design, structure and contextualize smells in the museum environment. This is partly due to the overall lack of knowledge for our sense of smell, but also because the presentation of smells in the context of cultural heritage varies with the type of event, exhibition, or experience that is being executed (Ehrich and Leemans 2024)4. Here, we will present two ways that the Scent of the Afterlife was presented to the public, summarizing form, function, and application in the museum. In this paper, we draw on the concept of “smell distribution techniques” from Odeuropa's Olfactory Storytelling Toolkit (Ehrich et al., 2023, p. 155–159). For the Scent of the Afterlife, we utilized two different distribution techniques falling under two types of scent diffusion: “Mobile Diffusion” and “Fixed Scent Station.”

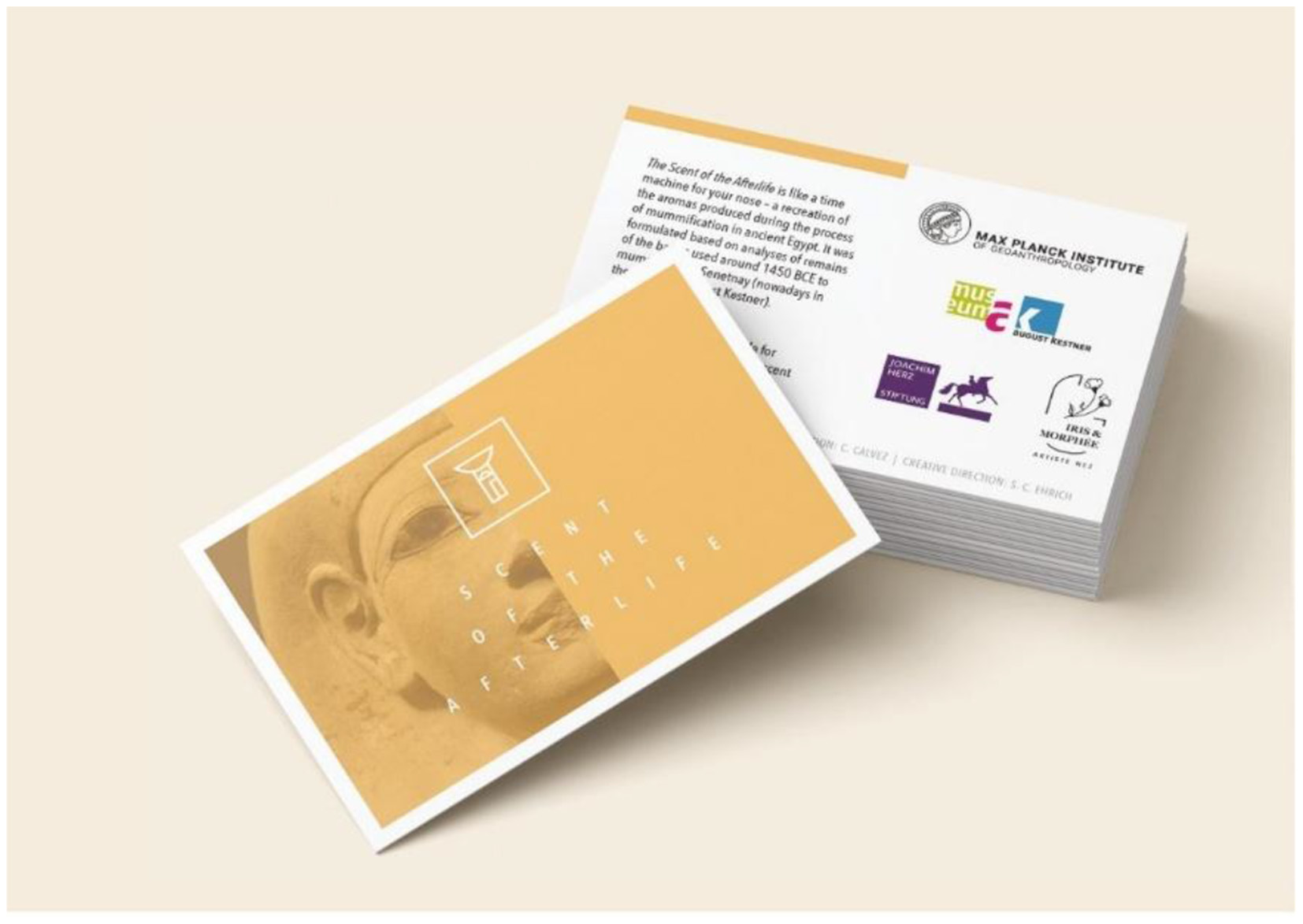

3.1 Mobile diffusion: scented card

Mobile diffusion is defined as a technique in which participants are provided with an individual item to hold, examine, and sniff at their own pace. These techniques are typically prepared in advance by applying aromatic substances to paper or other diffusive objects (e.g., handheld dry diffuser, hand fan, etc.) (Ehrich et al., 2023, p. 146). The Scent of the Afterlife card featured an olfactory reproduction, which was scent-printed onto cards (Figure 1). For context, the back of the scented card had a QR code that led to an explanation of the reproduction and the process behind its creation.5 These cards were distributed in a variety of settings, including formal exhibitions, educational workshops, science events, university classes, and public lectures.

Figure 1

The Scent of the Afterlife scented card. The essence of the reproduced scent is inserted into the paper via scent-printing. Artwork by Michelle O' Reilly.

A notable application took place at the Museum August Kestner in Hannover, where Senetnay's two original canopic jars are on permanent display. With explanation, the scented card is presented alongside the original vessels and integrated into guided tours (Huber and Loeben, 2023 p. 9). It enables visitors to connect the visual presence of the artifacts with their reconstructed aroma, creating a multisensory encounter that highlights the sensory richness of Egyptian embalming rituals and fosters embodied understanding of their cultural significance (Figure 2). Beyond this permanent installation, the card format has proven versatile: it was distributed to researchers, students, museum professionals and artists, serving both as a multisensory extension of the research and as a tangible tool for education and science communication. Visitors were able to take the scent home, extending the experience beyond the museum visit and encouraging reflection and discussion in new settings. While dissemination of scented cards offers many advantages, it runs the risk that visitors will discard them in unsuitable areas of the exhibition space.

Figure 2

Visitors sniffing the Scent of the Afterlife card during a guided tour at the Museum August Kestner, Hannover, Germany. Photograph by: Ulrike Dubiel, Museum August Kestner.

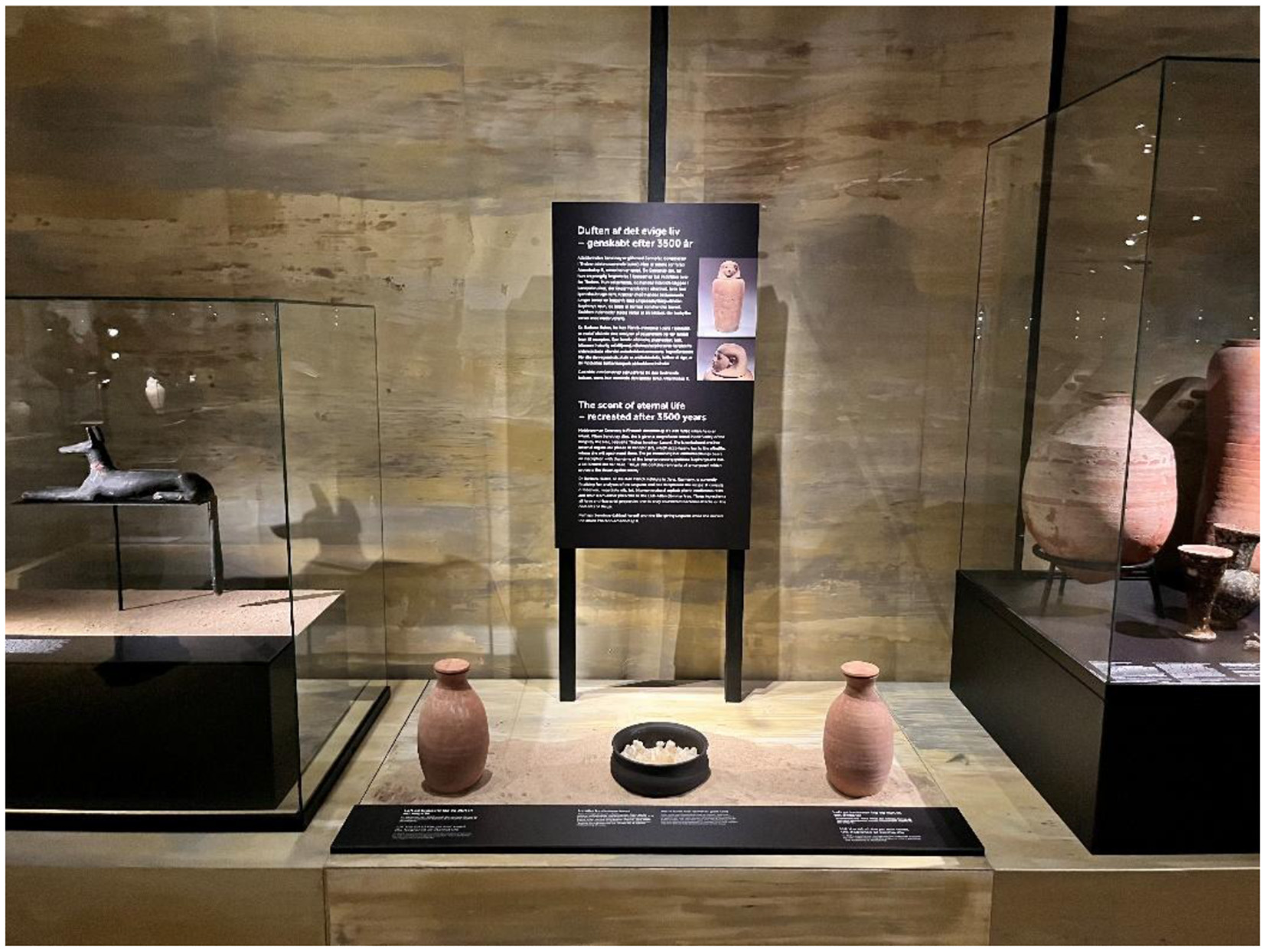

3.2 Fixed scent station

The second approach adopted for the Scent of the Afterlife was the installation of a “Fixed Scent Station,” which are structures built for heritage institutions that diffuse scent safely, often through dry diffusion to avoid harming collections. They can be adapted for different audiences and settings, with adjustable heights and options such as foot pumps to improve accessibility and hygiene (Ehrich et al., 2023).6 Unlike mobile diffusion, fixed scent stations are integrated and installed within the scenography of the exhibition. However, they also introduce practical challenges. Scented materials must be properly contained, dosed and stabilized to avoid impeding the gallery space or causing visitor discomfort. Curator and perfumer should collaborate to ensure that the olfactory experience remains effective, consistent and safe throughout the course of the exhibition period.

The 2023 exhibition, Ancient Egypt–Obsessed with Life at the Moesgaard Museum in Aarhus, Denmark, employed a fixed scent station to present the Scent of the Afterlife (referred in this exhibition as the Scent of Eternal Life). Situated in a room representing an ancient Egyptian embalming workshop, the station allowed visitors to experience the reconstructed balm alongside objects and narratives related to mummification and the afterlife (Ehrich, 2024). Scent cartridges were placed inside two modern ceramic vessels that represented Senetnay's canopic jars, which were positioned next to an exhibition board with text and imagery of the original jars (Figure 3). Visitors were invited to lift the lids to sniff and experience the aroma of embalming as well as learn about the raw materials used in the reproduction.7 This setup allowed multiple visitors to engage simultaneously, creating a collective sensory experience. It also allowed for a meaningful integration of the olfactory experience into the exhibition's overall scenography. Positioned within the “mummification workshop” gallery and surrounded by original vessels and sets of canopic jars, the station complemented the display context while seamlessly fitting into the exhibition's flow, preventing congestion among the more than 260,000 visitors. Visitor observation suggested that the fixed scent station added a powerful sensory dimension to the display, deepening the emotional resonance of the exhibition narrative and enhancing its memorability.

Figure 3

Museum display for the Scent of the Afterlife at the Moesgaard Museum in Denmark's exhibition, Ancient Egypt–Obsessed with Life. Photograph by: Barbara Huber.

4 Discussion: the impact of the Scent of the Afterlife

The Scent of the Afterlife project shows how biomolecular research can be transformed into a powerful tool for education, science communication, and museum interpretation. By curating olfactory reproductions from biomolecular data, archaeological insights were brought to the public, creating sensorial encounters with the ancient past. This project provides further study for how museum practitioners can design olfactory museological projects and how these projects impact the people and institutions that are involved with them. The Scent of the Afterlife attracted international media attention, reaching new audiences and sparking dialogue about olfactory and sensory heritage. The scented cards were mailed to various institutions and individuals internationally, reaching audiences well beyond the museum. Together, these outcomes demonstrate how olfactory reproductions broaden the accessibility and impact of archaeological science. The following sections will outline how the Scent of the Afterlife has impacted visitor experience, museum practice and public outreach.

4.1 Visitor experience

Feedback from both informal conversations and structured surveys conducted on the guided tours at the Museum August Kestner, Hanover, suggests that the integration of scent provided an immediate and effective entry point into the ancient world. These surveys were conducted on approximately 250 visitors who participated in the tours over a 3 month period (see Supplementary material). The vast majority (around 99%) reported that the experience created a more intimate connection with the past, with many noting that it felt more immersive than traditional text- or object-based interpretation. Overall, respondents described the scent component as a valuable and informative addition to the tour, and most indicated that they had never previously encountered the use of scent in a museum setting. The act of smelling encouraged slower, more reflective engagement with the displays and encouraged discussions, echoing earlier findings of olfactory museology that scent can extend time spent with artworks and deepen comprehension (Aggleton and Waskett, 1999; Eardley et al., 2018; Verbeek et al., 2022). Another notable visitor observation was that engaging with the scent card altered initial expectations that mummies would have an unpleasant or “stinking” odor. Experiencing the scent, containing many aromatic ingredients identified in the embalming material, provided a sensory correction to this common misconception. The scent revealed that mummification was not a process of decay, but one of preservation, in which aromatic and bioactive substances played a vital role in protecting the body and ensuring eternal life. It should be noted, however, that the perfumer's brief intentionally specified a moderately pleasant hedonic tone to ensure visitor comfort and accessibility within the museum setting. While this design choice may have influenced visitors' perceptions, it was consistent with the historical reality that embalming materials were highly aromatic and fragrant. Through this olfactory encounter, visitors were able to perceive mummification as an act of care and transformation rather than one of death and decomposition. Such reactions underscore that olfactory interpretation provokes dialogue as much as immersion, encouraging critical engagement with the sensory past.

4.2 Museum practice

For museum practitioners, the project offered a model for how scientific data can be mobilized for multisensory interpretation. It also demonstrated how olfactory reproductions influence curatorial practice. The cross-disciplinary collaboration contributed new professional expertise for exhibition development, while also prompting reflection on practical issues. Decisions about integrating and designing the olfactory interpretation required careful attention to the affordances of the space and to consider potential visitor sensitivities. This process confirmed that olfactory interpretation is not merely an add-on but a design practice that must be carefully integrated into curatorial workflows (Ehrich and Leemans 2022, p. 13)8. Lastly, the integration of olfactory interpretation broadened accessibility and inclusion efforts, providing new pathways of engagement for those who are neurodiverse and that have disabilities.

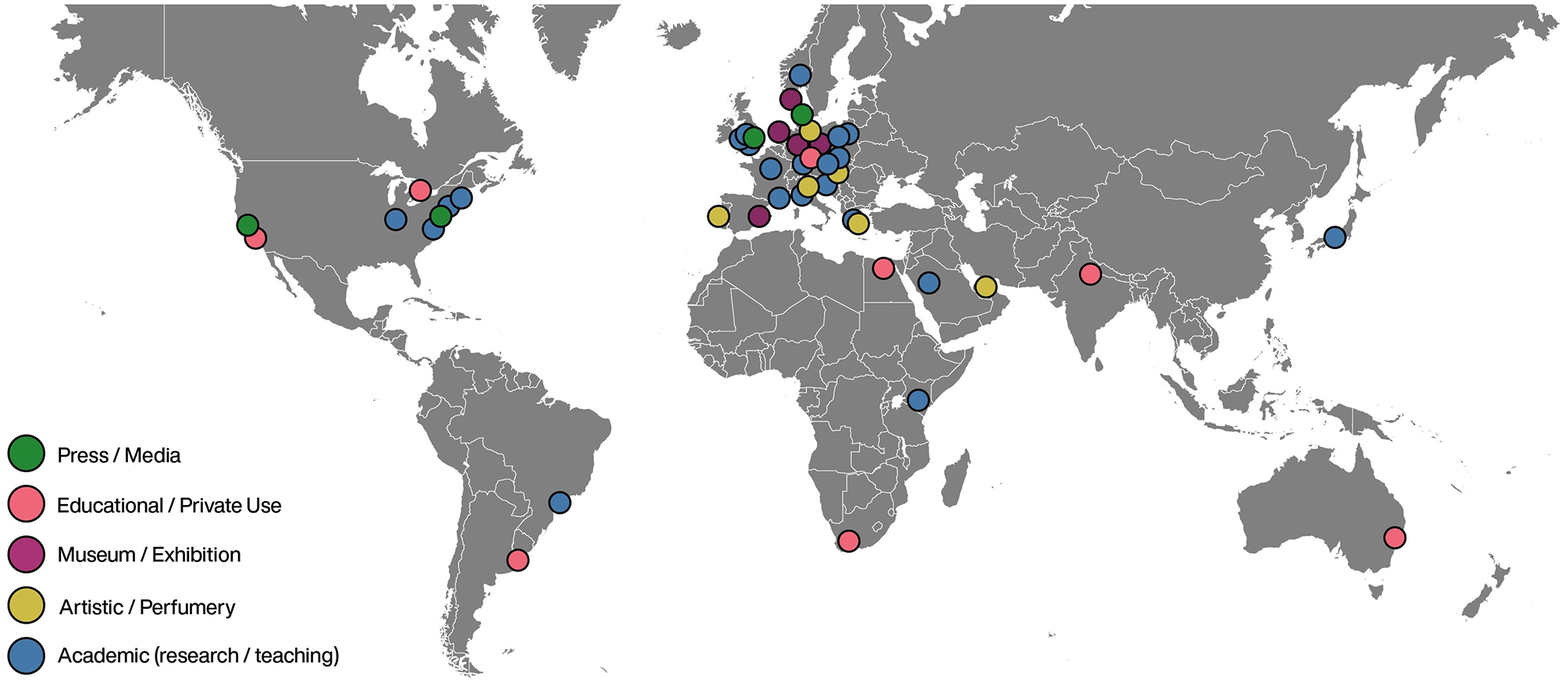

4.3 Public outreach

Beyond museums, the scented cards circulated internationally to individuals, institutions, students, journalists and artists, expanding the project's impact through networks of professional exchange media, education and art. Mapping this distribution reveals a wide-ranging uptake of the cards, from university seminars to heritage workshops, suggesting that scent can serve as an effective medium of knowledge transfer across different audiences (Figure 4). The cards also created a tangible trace of the project's dissemination: unlike text or images, receivers of the card carry with them an embodied, sensory reminder of the ancient past.

Figure 4

World network map showing the international distribution and reception of the Scent of the Afterlife.

As the dissemination of ancient scents based on biomolecules remains relatively novel in museum exhibitions, olfactory exhibitions tend to attract considerable press attention. Coverage of the Scent of the Afterlife at the Moesgaard Museum consistently highlighted the value of its olfactory interpretation. Reviewers praised the exhibition's innovative integration of scientific research and scent reconstruction, noting how new insights into embalming materials were brought to life through reconstructed aromas available for visitors to experience firsthand.

5 Outlook: toward a multisensory archaeology

Looking ahead, the Scent of the Afterlife points to several directions for future research and practice. First, olfactory museology would benefit from closer collaboration with archaeological science. While projects like Odeuropa developed frameworks for olfactory heritage interpretation, they remain largely rooted in textual and humanities-driven approaches. The material evidence and detailed data provided by biomolecular archaeology can uniquely enrich multisensory museum initiatives. Integrating these scientific insights more systematically into museological practice will require shared methodologies for documenting the creation of olfactory reproductions and for making interpretive decisions explicit.

Second, ethical reflection must remain central. Olfactory reproductions are never neutral: they are shaped by scientific constraints, cultural interpretations, and curatorial decisions. Careful attention to visitor sensitivities, including allergies and scent aversions, and respect for the cultural significance of reproduced substances are vital. Equally important, the decision to use modern, IFRA-compliant materials reflects ethical and environmental considerations, as many ancient aromatic ingredients are endangered, hazardous, or cannot be responsibly sourced today (Bongers et al., 2019). Contemporary equivalents thus represent the most sustainable and safe option for museum contexts. Furthermore, engaging stakeholder communities in the design and presentation of scents will help ensure that olfactory heritage is interpreted with care and inclusivity.

Building on these ethical and methodological considerations, future olfactory heritage initiatives could also make the scientific and creative processes behind scent reconstruction more visible to museum visitors. Although the Scent of the Afterlife already provides contextual information through guided tours and QR-linked resources, there remains significant potential to communicate more explicitly how biomolecular data, perfumery practice, and curatorial decisions intersect. Exhibitions could incorporate concise visualizations of the analytical workflow, together with elements of the olfactory brief, formulation stages, and key interpretive choices. Such “behind-the-scenes” insights, already common in fields like painting and artifact conservation, would invite dialogue about authenticity and method, and foreground the interdisciplinary collaboration that enables olfactory reproductions.

Finally, integrating biomolecular scent research into heritage practice opens new opportunities for developing a more accessible multisensory archaeology, particularly for visitors who are visually impaired or have low vision, as well as those who are deaf or hard of hearing, for whom smell can provide an alternative and meaningful sensory pathway into the past. As museums increasingly embrace soundscapes, tactile replicas, and immersive visualizations, smell can play a vital role in evoking the lived experiences of the past. Combining archaeological science with thoughtful museological design allows for an embodied understanding of history – one that invites us not only to see and read about the past, but also to smell, feel, and experience it. Lessons from the Scent of the Afterlife provide a foundation for future projects seeking to reconnect the public with the multisensory dimensions of cultural heritage.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SE: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology. CC: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. CL: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization. UD: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. ST: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BH: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Funding.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The publication of this work was funded under the Max Planck Society (MPG) DEAL agreement. Barbara Huber received funding for this project from the Joachim Herz Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fearc.2025.1736875/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^Alexopoulos, Georgios, Cecilia Bembibre et al. “Odeuropa Deliverable D6.2 Questionnaires for measuring the value of introducing smells in GLAMs.” Odeuropa, 2023.

2.^Senetnay lived around 1450 BCE and was a high-ranking noblewoman who served as wet nurse to the future Pharaoh Amenhotep II, son of Thutmose III. Her embalmed organs were discovered by Howard Carter in 1900 in Tomb KV 42 in the Valley of the Kings at Thebes (Loeben, 2009).

3.^Ehrich, Sofia Collette, and Inger Leemans. “Odeuropa Deliverable D7.4 The Olfactory Storytelling Toolkit.” Odeuropa, 2023, https://odeuropa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Draft_D7_4_Olfactory_Storytelling__Toolkit_rev.pdf.

4.^See page 12–13 of Ehrich, Sofia Collette, and Inger Leemans. “Odeuropa Deliverable D7.3 Impact Activities Report Y2,” Odeuropa, 2022. Available online at: https://odeuropa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Draft_D7_3_Impact_Activities_Report_Y2.pdf.

5.^The QR code on the back of the Scent of the Afterlife card leads to https://barbara-huber.com/scent-of-the-afterlife-a-peek-into-ancient-egyptian-mummification/.

6.^Selected Scent Station examples appear in the following exhibitions: Queens of Egypt at the The National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C. (2019), Fleeting - Scents in Colour at the Mauritshuis in the Netherlands (2021), Mondrian Moves at the Kunstmuseum in the Netherlands (2022), The Essence of a Painting. An Olfactory Exhibition at the Prado in Spain (2022), Scent and the Art of the Pre-Raphaelites at the The Barber Institute of Fine Arts in the United Kingdom (2024), and “Kindheit am Nil – Aufwachsen im Alten Ägypten” at Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst in Munich (2025).

7.^Each of the two fixed scent stations contained a scent cartridge that was affixed inside and at the bottom of the vessel. The scent cartridge consists of Pebax beads infused with the perfume oil and was replaced every two months. A sponge was attached to the underside of the lid and acted as a seal, ensuring the aroma remained contained within the jar. When interacting with the vessels, visitors could choose if they wanted to sniff the sponge or the jar.

8.^See page 13 of Ehrich, Sofia Collette, and Inger Leemans. “Odeuropa Deliverable D7.3 Impact Activities Report Y2,” Odeuropa, 2022. Available online at: https://odeuropa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Draft_D7_3_Impact_Activities_Report_Y2.pdf.

References

1

Aggleton J. P. Waskett L. (1999). The ability of odours to serve as state-dependent cues for real-world memories: can Viking smells aid the recall of Viking experiences?Br. J. Psychol.90, 1–7. doi: 10.1348/000712699161170

2

Badillo-Sanchez D. Serrano Ruber M. Davies-Barrett A. Jones D. J. L. Hansen M. Inskip S. (2023). Metabolomics in archaeological science: a review of their advances and present requirements. Sci. Adv.9:eadh0485. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adh0485

3

Bembibre C. (2021). “Archiving the intangible: preserving smells, historic perfumes and other ways of approaching the scented past,” in The Smells and Senses of Antiquity in the Modern Imagination, eds. A. Grand-Clément and C. Ribeyrol (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc), 155–173. doi: 10.5040/9781350169753.ch-007

4

Bembibre C. Leemans I. Elpers S. (2024). The Olfactory Heritage Toolkit. Amsterdam: Zenodo. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.10700211

5

Bembibre C. Strlič M. (2017). Smell of heritage: a framework for the identification, analysis and archival of historic odours. Herit. Sci.5:2. doi: 10.1186/s40494-016-0114-1

6

Bongers F. Groenendijk P. Bekele T. Birhane E. Damtew A. Decuyper M. et al . (2019). Frankincense in peril. Nat. Sustain.2, 602–610. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0322-2

7

Brøns C. (2025). The scent of ancient greco-roman sculpture. Oxford J. Archaeol.44, 182–201. doi: 10.1111/ojoa.12321

8

Cappellini E. Prohaska A. Racimo F. Welker F. Pedersen M. W. Allentoft M. E. et al . (2018). Ancient biomolecules and evolutionary inference. Annu. Rev. Biochem.87, 1029–1060. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-012002

9

Chazot I. R. Camus, A. Borloz S-V. Wicky E. David O. R. P. Fontaine T. (2023). The NOMEN Project. Classification of fragrant compositions for historical purposes. Representing, reconstituting, reconstructing or reinventing an ancient “perfume”?PsyAxiv preprint. https://hal.science/hal-04158225/document

10

Classen C. (2007). Museum manners: the sensory life of the early museum. J. Soc. Hist.40, 895–914. doi: 10.1353/jsh.2007.0089

11

Dupré S. (2017). Materials and techniques between the humanities and science: introduction. His. Humanit.2, 173–178. doi: 10.1086/690577

12

Dziobek E. Höveler-Müller M. Loeben C. E. eds. (2009). Das geheimnisvolle Grab 63: die neueste Entdeckung im Tal der Könige. Rahden/Westf: Leidorf.

13

Eardley A. F. Dobbin C. Neves J. Ride P. (2018). Hands-on, shoes-off: multisensory tools enhance family engagement within an art museum. Visit. Stud.21, 79–97. doi: 10.1080/10645578.2018.1503873

14

Ehrich S. C. (2024). Crafting intentional scents: enriching cultural heritage with educational olfactory reproductions. Ams. Museum J.2, 249–275. doi: 10.61299/it356Wqy

15

Ehrich S. C. Leemans I. Bembibre C. Tullett W. Verbeek C. Alexopoulos G. et al . (2023). Olfactory Storytelling Toolkit: A “How-To” Guide for Working with Smells in Museums and Heritage Institutions.Amsterdam: Zenodo. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.10254737

16

Evershed R. P. Clark K. A. (2020). “Trends in use of organic balms in egyptian mummification revealed through biomolecular analyses,” in the Handbook of Mummy Studies: New Frontiers in Scientific and Cultural Perspectives, eds. D. H. Shin and R. Bianucci (Singapore: Springer), 1–63. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-1614-6_9-1

17

Evershed R. P. Davey Smith G. Roffet-Salque M. Timpson A. Diekmann Y. Lyon M. S. et al . (2022). Dairying, diseases and the evolution of lactase persistence in Europe. Nature174, 336-345. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05010-7

18

Fulcher K. Serpico M. Taylor J. H. Stacey R. (2021). Molecular analysis of black coatings and anointing fluids from ancient Egyptian coffins, mummy cases, and funerary objects. PNAS118:e2100885118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2100885118

19

Germer R. (2005). Mumien. Düsseldorf: Albatros.

20

Gretzinger J. Biermann F. Mager H. King B. Zlámalová D. Traverso L. et al . (2025). Ancient DNA connects large-scale migration with the spread of Slavs. Nature646, 384-393. doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09437-6

21

Hausleiter A. Huber B. eds. (2025). Scents of Arabia: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Ancient Olfactory Worlds. Bicester: Archaeopress Archaeology.

22

Howes D. (2006). Charting the sensorial revolution. Senses Soc.1, 113–128. doi: 10.2752/174589206778055673

23

Howes D. (2014). Introduction to sensory museology. Senses Soc.9, 259–267. doi: 10.2752/174589314X14023847039917

24

Huber B. Hammann S. Loeben C. E. Jha D. K. Vassão D. G. Larsen T. et al . (2023). Biomolecular characterization of 3500-year-old ancient Egyptian mummification balms from the Valley of the Kings. Sci. Rep.13:12477. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-39393-y

25

Huber B. Hausleiter A. Dinies M. Al-Najem M. Alonazi M. Säumel I. et al . (2025a). “Exploring the aromatic diversity of incense materials at the ancient oasis of Taymā using metabolic profiling,” in Scents of Arabia: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Ancient Olfactory Worlds, eds. A. Hausleiter and B. Huber (Bicester: Archaeopress Archaeology), 61–86.

26

Huber B. Larsen T. Spengler R. N. Boivin N. (2022). How to use modern science to reconstruct ancient scents. Nat. Hum. Behav.6, 611–614. doi: 10.1038/s41562-022-01325-7

27

Huber B. Loeben C. E. (2023). Senetnay – “medienstar” aus hannover: weltweit wurde über analyse und duftrekonstruktion von balsamierungsresten berichtet. aMun – Magazin für die Freunde Ägyptischer Museen und Sammlungen67, 4–9.

28

Huber B. Luciani M. Abualhassan A. M. Giddings Vassão D. Fernandes R. Devièse T. (2025b). Metabolic profiling reveals first evidence of fumigating drug plant Peganum harmala in Iron Age Arabia. Commun. Biol.8:720. doi: 10.1038/s42003-025-08096-7

29

Ikram S. (1998). The Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

30

Kiechle M. A. (2016). Preserving the unpleasant: sources, methods, and conjectures for odors at historic sites. Future Anterior. J. Historic Preser. His. Theor. Crit.13, 22–32. doi: 10.5749/futuante.13.2.0023

31

Leemans I. Tullett W. Bembibre C. Marx L. (2022). Whiffstory: using multidisciplinary methods to represent the olfactory past. Am. Hist. Rev.127, 849–879. doi: 10.1093/ahr/rhac159

32

Levent N. S. Pascual-Leone A. eds. (2014). The Multisensory Museum: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory, and Space. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield. doi: 10.5040/9798881816100

33

Loeben C. E. (2009). “Katalog der ausstellungsstücke aus der ägyptischen sammlung des museum august kestner, hannover/catalogue of the exhibited objects from the egyptian collection of museum august kestner, hannover.,” in Das geheimnisvolle Grab 63: Die neueste Entdeckung im Tal der Könige – Archäologie und Kunst von Susan Osgood/The Mysterious Tomb 63: The Latest Discovery in the Valley of the Kings – Art and Archaeology of Susan Osgood, eds. E. Dziobek, M. Höveler-Müller, and C. E. Loeben (Leidorf, Rhaden/Westf.), 13, 142–188. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-39393-y

34

Mahan S. J. Stein R. Armitage R. A. (2025). Compositional analysis of greco-roman unguentaria residues from the Michael C. carlos museum. Herit.8:170. doi: 10.3390/heritage8050170

35

Marx L. Ehrich S. C. Tullett W. Leemans I. Bembibre C. (2022). Making Whiffstory: a contemporary re-creation of an early modern scent for perfumed gloves. Am. Hist. Rev.127, 881–893. doi: 10.1093/ahr/rhac150

36

Orsingher A. Solard B. Bertelli I. Ribechini E. Maritan L. Badreshany K. et al . (2025). Scents of home: phoenician oil bottles from motya. J. Archaeol. Method Theor.32:59. doi: 10.1007/s10816-025-09719-3

37

Paolin E. Bembibre C. Di Gianvincenzo F. Torres-Elguera J. C. Deraz R. Kraševec I. et al . (2025). Ancient Egyptian mummified bodies: cross-disciplinary analysis of their smell. J. Am. Chem. Soc., jacs:4c15769. doi: 10.1021/jacs.4c15769

38

Rageot M. Hussein R. B. Beck S. Altmann-Wendling V. Ibrahim M. I. M. Bahgat M. M. et al . (2023). Biomolecular analyses enable new insights into ancient Egyptian embalming. Nature614, 287–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05663-4

39

Ren M. Ren X. Wang X. Yang Y. (2022). Characterization of the incense sacrificed to the sarira of sakyamuni from famen royal temple during the ninth century in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A119:e2112724119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2112724119

40

Scott A. Power R. C. Altmann-Wendling V. Artzy M. Martin M. A. S. Eisenmann S. et al . (2020). Exotic foods reveal contact between South Asia and the near east during the second millennium BCE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A118:202014956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014956117

41

Spyrou M. A. Bos K. I. Herbig A. Krause J. (2019). Ancient pathogen genomics as an emerging tool for infectious disease research. Nat. Rev. Genet.20, 323–340. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0119-1

42

Squires K. Davidson A. Cooper S. Viner M. Hoban W. Loynes R. et al . (2024). A multidisciplinary investigation of a mummified Egyptian head and analysis of its associated resinous material from the salinas regional archaeological museum in palermo (Sicily). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep.55:104525. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2024.104525

43

Verbeek C. (2016). Presenting volatile heritage: two case studies on olfactory reconstructions in the museum. Future Anterior. J. His. Preser. His. Theor. Crit.13:33. doi: 10.5749/futuante.13.2.0033

44

Verbeek C. Leemans I. Fleming B. (2022). How can scents enhance the impact of guided museum tours? towards an impact approach for olfactory museology. Senses Soc.17, 315–342. doi: 10.1080/17458927.2022.2142012

45

Wilkin S. Ventresca Miller A. Fernandes R. Spengler R. Taylor W. T.-T. Brown D. R. et al . (2021). Dairying enabled early bronze age yamnaya steppe expansions. Nature598, 629–633. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03798-4

46

Zhao W. Whelton H. L. Blong J. C. Shillito L.-M. Jenkins D. L. Bull I. D. (2023). Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) as a rapid means for assessing the source of coprolites. iScience26:106806. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.106806

Summary

Keywords

biomolecular archaeology, multisensory museum experience, olfactory heritage, olfactory reproductions, past scents, olfactory museology

Citation

Ehrich SC, Calvez C, Loeben CE, Dubiel U, Terp Laursen S and Huber B (2026) From biomolecular traces to multisensory experiences: bringing scent reproductions to museums and cultural heritage. Front. Environ. Archaeol. 4:1736875. doi: 10.3389/fearc.2025.1736875

Received

31 October 2025

Revised

10 December 2025

Accepted

15 December 2025

Published

05 February 2026

Volume

4 - 2025

Edited by

Zihua Tang, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, China

Reviewed by

Sean Coughlin, Institute of Microbiology, Czechia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Ehrich, Calvez, Loeben, Dubiel, Terp Laursen and Huber.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Barbara Huber, huber@gea.mpg.de; Sofia Collette Ehrich, sofia@olfactorycontractor.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.