Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), along with other chronic liver diseases, leads to progressive fibrosis and, ultimately, cirrhosis. Liver fibrosis is a major cause of global morbidity and mortality. Although past efforts to develop antifibrotic drugs have largely failed, recent advances in MASH metabolic therapies offer new hope. These include both indirect-acting agents such as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) analogues, which reduce liver fat by promoting weight loss, and therapies with direct-acting mechanisms on the liver, such as thyroid hormone receptor beta (THRβ) activators and fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) analogues. This perspective summarises emerging antifibrotics, from the fast-evolving class of metabolic therapies through to the more sluggish development of non-metabolic antifibrotics. We consider future therapeutic combinations and patient stratifiers that may impact patient outcomes, and close by asking if fibrosis reversal should be the only goal.

1 Introduction

Worldwide, 1/25 deaths is due to liver disease (1), with more than a quarter of the global adult population living with chronic liver disease, whether that be MASH, alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD), viral hepatitis, cholestatic disorders such as primary biliary cholangitis, or genetic disorders such as haemochromatosis. Of particular concern is the rising prevalence of the so-called MASH ‘tsunami’ (2), fuelled by rising societal obesity. The consequence of MASH and other chronic liver conditions is fibrosis – scarring that progresses to cirrhosis in its most severe form. To date, fibrosis remains the strongest predictor of liver-associated morbidity and mortality, and so its regression has become a therapeutic ‘holy grail’ (3).

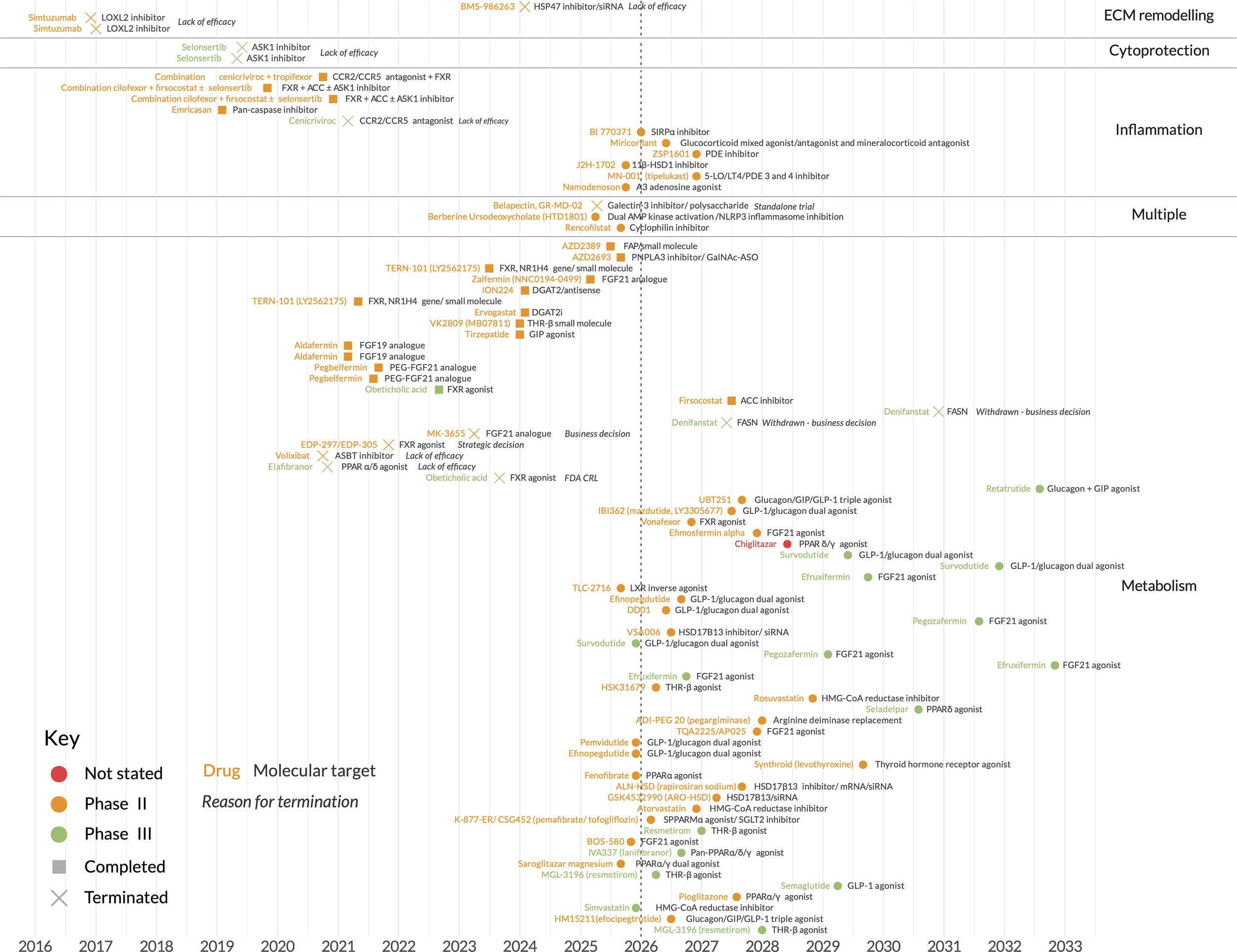

Until recently, the search for agents that regress liver fibrosis has been met with repeated failure across multiple therapeutic classes (Figure 1, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Examples include (i) cytoprotectants such as apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) inhibitors and pan-caspase inhibitors (4, 5); (ii) metabolic therapies such as acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) inhibitors and farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonists (6, 7); (iii) chemokine inhibitors such as C-C chemokine receptor type 2/C-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR2/CCR5) inhibitors and galectin-3 inhibitors (8, 9); and (iv) extracellular matrix (ECM) remodellers such as lysyl oxidase homologue 2 (LOXL2) inhibitors (10). However, the field has now been energised with renewed optimism thanks to indirect- and direct-acting metabolic agents targeted at MASH patients.

Figure 1

Key MASH clinical trials, past and ongoing. Dates shown are actual (past) or intended (future) completion dates. Further details are provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

2 MASH — fuelling an emerging metabolic toolbox

Metabolic therapies are shaping up as a critical success in chronic liver disease, with resmetirom (a direct-acting thyroid hormone receptor-beta [THR-β] agonist) becoming the first to receive US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) accelerated approval for non-cirrhotic MASH, in 2024. In a 52-week phase III trial (11), it achieved both histological surrogate endpoints required by the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) — improvement in steatohepatitis and fibrosis (12, 13). Twenty-six percent of patients achieved fibrosis improvement by at least one stage without worsening steatohepatitis, versus 14% with placebo (11). Although most patients still failed to reach a statistically significant response within 1 year, this has proven to be a seminal moment, with semaglutide (a glucagon-like peptide 1 [GLP-1] analogue) and efruxifermin (a fibroblast growth factor 21 [FGF21] analogue) rapidly following. In a 72-week phase III MASH trial, semaglutide improved fibrosis without worsening steatohepatitis in 37% of patients, versus 22% for placebo (14), resulting in its recent FDA approval (15).

While these trials have focused on pre-cirrhotic MASH, efruxifermin has become the first metabolic therapy to report positive results in more advanced fibrosis in a 96-week phase II trial of MASH patients with compensated cirrhosis (16). By intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, 29% of patients demonstrated at least one stage improvement in liver fibrosis without steatohepatitis worsening, versus 11% with placebo (16). While a therapeutic intervention regressing cirrhosis may be paradigm shifting, the findings of histological improvement remain a surrogate endpoint. The true impact of these results remains to be seen in phase III trials and beyond, in which morbidity and mortality outcomes – such as the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), decompensation, and transplant-free survival – will be the ultimate tests of efficacy (17).

With about 30 key trials expected to readout over the next 5 years (Figure 1, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), metabolic therapies look set to become a frontline option for patients with MASH and compensated cirrhosis. How might this frontline evolve and be used? A key question of the toolbox is where direct-acting versus indirect-acting mechanisms may prove most useful. Therapies that do not promote weight loss may, for example, be preferred for the one in six patients with MASH classed as ‘lean MASH’ (those with a normal body mass index [BMI]), in whom the sarcopenic side-effect of GLP-1 analogues would be undesirable. On the other hand, GLP-1 analogues will likely be preferred as part of broader cardiometabolic interventions in patients with BMI >30 kg/m2 and comorbidities. Interestingly, the reduction in alcohol intake observed with semaglutide (18) may also enable a new therapeutic option to improve abstinence in ALD (alone or in combination with MASH [MET-ALD]) without the side-effects commonly experienced with disulfiram and naltrexone.

Beyond BMI and comorbidity considerations is the question of therapies with alternative metabolic mechanisms. With the current low therapeutic response rates it stands to reason that multiple metabolic mechanisms, with their respective addressable patient populations and side-effects, will prove valuable. Of particular interest is targeting the metabolism of other liver cell populations. The dominant mechanism of the therapies discussed thus far is understood to be largely via a relative increase in hepatocyte beta oxidation. However, denifanstat, a fatty acid synthase (FASN) inhibitor that reduces de novo lipogenesis in both hepatocytes and stellate cells, may become one such complementary approach. In the ITT analysis of its phase II trial, 30% of patients achieved at least one stage of fibrosis improvement, versus 14% with placebo – with subgroup analysis suggesting the greatest response in F3 patients (19). However, a planned phase III study has been paused prior to enrollment for business reasons. Another potential therapy known to directly inhibit stellate cell activation is lanifibranor. Interest in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) agonists, such as lanifibranor, extends back several decades, despite weight gain and oedema limiting their use (20). Lanifibranor is currently in a phase III trial for MASH patients with type 2 diabetes (21), with pioglitazone (an insulin sensitising PPARγ agonist approved for type 2 diabetes) in multiple phase IV trials.

All things considered there is certainly promise for metabolic therapies of multiple mechanisms, but no clear home run yet beyond targeting weight loss, THRβ signalling, and FGF21 signalling.

3 An antifibrotic toolbox lacking diversity

While the low MASH therapy response rates are a crucial concern, another is that steatosis is not the primary driver of disease for a large proportion of liver fibrosis patients (22). This includes many patients in the later stages of MASH fibrosis. Globally, in 2017 hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), and alcohol were responsible for most cases of compensated cirrhosis, 33%, 25%, and 21%, respectively, compared with 8% of cases due to MASH. Similarly, the major causes of death due to cirrhosis were HBV (29%), HCV (26%), and alcohol (25%), with only 9% due to MASH (22). So, it stands to further reason that broader, non-metabolic, antifibrotic mechanisms are required for widespread patient impact. Non-metabolic therapies such as LOXL2 and ASK1 inhibitors have been clinically tested as far back as a decade ago, with progress remaining slow.

Antibodies have proven enticing, despite the early failure of simtuzumab, which targets LOXL2, a collagen cross-linker (10). Nevertheless, current successes remain predominantly at phase I: (i) BI 765423, an interleukin (IL-11) inhibitor with antifibrotic and cytoprotective mechanisms (23) (ii) lixudebart, an anti-claudin-1 antibody that reduces cell adhesion and allows tissue remodelling (24), and (iii) BI 770371 which activates innate and adaptive anti-tumour immune responses also relevant to fibrosis (25), recently moving into phase II development for compensated cirrhosis due to MASH. Cell-based therapies have demonstrated promise, with a recent phase II study of autologous macrophage therapy in cirrhosis demonstrating improvement in transplant-free survival (26). A chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, initially developed to treat haematological malignancies (27), has also demonstrated the ability to clear senescent hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) (28–30).

As with biologics, small molecule and ribonucleic acid (RNA) therapies have yet to demonstrate clear successes. PLN-1474, a selective αvβ1 integrin inhibitor that reduces fibrosis via transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signalling, has reported favourable safety, a key concern with TGF-β inhibition (31). However, with intended co-development plans terminated, the next steps seem uncertain. BMS-986263, a small interfering RNA (siRNA) against collagen chaperone heat shock protein 47 (HSP47) has demonstrated early therapeutic promise in a phase II study of HCV with fibrosis (32, 33). However, a phase II trial in patients with compensated MASH cirrhosis was terminated for lack of efficacy (34). Selvigaltin (GB1211), a small molecule of the TGF-β signalling protein, galectin-3, has been well tolerated (35). However, further studies appear to have been halted due to a change in clinical development strategy (36).

Collectively, non-metabolic antifibrotics await their ‘resmetirom moment’ to provide the much-needed diversity to the antifibrotic toolbox. A toolbox that will likely consider therapies not only by mechanism, but their potency and tolerability as variables in a precision medicine endeavour.

4 Antifibrotic precision medicine — the right combination in the right patient, at the right time

Epidemiological studies suggest that variability in response to antifibrotic agents is to be expected. It has been long recognised that while some F3 fibrosis patients progress to cirrhosis within a few years, others remain stable for over a decade (37). Varied outcomes in metabolic patients are also well documented, with one study proposing an obesity group at increased risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, and a second with limited comorbidity risk despite similar liver steatosis levels (38). Intrapatient responses also vary over time, as observed in a cenicriviroc MASH phase II study where not all patients maintained a therapeutic response after 1 year (39).

Sex, ethnicity, and genetics provide further clues that the evolution of liver antifibrotics will have precision medicine at its core. Premenopausal women are less prone to MASH fibrosis and HCC (40, 41), although trials have yet to demonstrate clear sex differences. Individuals of Hispanic ancestry have a greater MASH prevalence and severity, partly due to the known patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) gene risk allele, while individuals of some African ancestries exhibit lower liver steatosis and fibrosis (42). Population genetics provides further fascinating clues, with variants of two genes of particular MASH therapeutic interest (43). The PNPLA3 risk variant I148M is thought to reduce its hydrolyse activity and its degradation, resulting in increased triglycerides in hepatocytes and retinyl esters in stellate cells (43). The accumulation of poorly degraded, abnormal protein that sequesters cofactors of other lipases makes this a toxic gain-of-function that is amenable to inhibitors. AZD2693, a PNPLA3 antisense oligonucleotide in phase II (44, 45), and ALN-PNP, an siRNA in phase I (46), have been developed to reduce total PNPLA3, while ARO-PNPLA3, an siRNA (47) targets the variant. While PNPLA3 points to the metabolic roots of fibrosis, the mechanism of a second gene, HSD17B13, remains less clear. Its loss-of-function variants reduce inflammation without a reduction in steatosis (48). HSD17B13 therapies in phase II are GSK4532990 and ALN-HSD (separate licenses of the siRNA ARO-HSD) (49, 50), with INI-822, a small molecule inhibitor, in phase I (51).

While genetics, sex and ethnicity paint a picture of metabolic and non-metabolic stratifiers, perhaps the most challenging stratifiers will be age, comorbidities, and their interaction. Older patients live with a greater number of comorbidities, have a diminished liver regenerative capacity, and may not tolerate the effects of certain therapies (such as GLP-1 agonist-induced sarcopenia). The most common MASH comorbidities in older patients are, unsurprisingly, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidaemia, and hypertension. Diabetics, representing over half of the patients in the semaglutide phase III MASH trial (52), tend to have more significant fibrosis with microvascular damage, although response differences between those with or without diabetes are unclear. This may be a result of semaglutide’s dual therapeutic impact on diabetes and obesity. Notably, hypertension and dyslipidaemia have already emerged as a treatment stratifier, with the exclusion of obeticholic acid, an FXR agonist, due to its low-density lipoprotein-raising effect, unless the patient is on statins. Obeticholic acid has faced a particularly rocky path, with FDA restrictions on its use for primary biliary cholangitis, and denial of MASH approval (53).

For the clinician, the precision medicine mindset will mean balancing: (i) those therapies addressing the initial insult versus those with more general antifibrotic potential, and (ii) those therapies with high-potency, low-tolerability profiles versus those with greater tolerability but potentially lower potency. As of yet we can only speculate which patients will benefit first from a long-term therapy gradually addressing the initial insult, versus those in which a shorter induction phase with a potent, but less tolerable, antifibrotic would be best (54). What is clear is that few, if any, patients with more advanced disease will fully benefit from monotherapies. Sadly, past trials offer few lessons to guide future combination strategies (Figure 1, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Perhaps the most notable failure has been the MASH phase II combinations of selonsertib (an ASK 1 inhibitor), cilofexor (an FXR agonist), and firsocostat (an ACC inhibitor) (6). However, short study timelines (48 weeks) and inclusion of only the most significant fibrosis stages may partly explain the failure. In addition, these preclinical models and the proposed mechanistic rationales may be inadequate to elucidate the relevant outcomes. However, the reasons for the failure of these approaches remain unclear.

Despite limited data, the enthusiasm for augmenting GLP-1 therapies remains. Multi-agonist molecules being trialled include the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonist tirzepatide (55), the amylin receptor agonist amycretin (56), the glucagon receptor agonist survodutide (57), and the glucagon + GIP receptor agonist retatrutide (58, 59). Although some trials have focused solely on obesity, multi-agonism may improve antifibrotic potential. This is supported by survodutide’s FDA ‘breakthrough therapy’ designation for non-cirrhotic MASH (57), and tirzepatide’s effectiveness in resolving steatohepatitis without worsening of fibrosis (55).

5 Towards a fibrosis ‘cure’ and normal liver function

From MASH through to HCV infection, the extent of liver fibrosis has become established as the most meaningful surrogate endpoint for liver-associated morbidity (decompensation and HCC) and mortality (transplant-free survival) (3). Consequently, therapeutic reversal of fibrosis has become a central goal. As recently as 20 years ago, doubts remained as to how much reversal would be possible in significant liver fibrosis (‘F2’ portal fibrosis to ‘F3’ bridging fibrosis). However, the rising popularity in the early 2000s of bariatric surgery for obesity management, complete HBV suppression with tenofovir/entecavir, and the development of a cure for HCV by the mid-2010s, all helped set new expectations. Up to 33% reduction of fibrosis of at least one stage has been reported within 1 year after bariatric surgery (60), and a response of as much as 50% has been reported after 3–5 years in HCV patients with sustained virological response (61). More recently, FGF21 analogues have added to the enthusiasm for rapid and extensive fibrosis reversal, with efruxifermin, pegozafermin, and efimosfermin alpha phase II trials demonstrating remarkable response rates for significant fibrosis within 6 months (62–64). These results have elicited interest in acquisition of these compounds for potential phase III development, with efruxifermin currently under investigation for MASH in three phase III clinical trials (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1).

Should full fibrosis reversal therefore be the sole therapeutic goal in MASH, especially in patients with cirrhosis? To date, the greatest body of evidence rests with HCV studies, which have demonstrated that while some complications such as raised portal pressure may resolve even in decompensated disease (65), HCC risk does not fully return to that expected of the fibrosis level the patient regresses to (66). Interestingly, an ongoing MASH phase III study of belapectin (a galectin-3 inhibitor) has also suggested that fibrosis and adverse outcomes may not be fully coupled (67). Analysis of the per-protocol patient population has indicated an 11–13% risk of oesophageal varices at 18 months (versus 22% with placebo) in the absence of fibrosis reversal (67).

MASH studies over the coming years will no doubt provide more insights. Until then, a reasonable assumption would be that tissue architecture and microcirculation disturbances, ongoing inflammatory processes (such as senescent hepatocytes) (68), and oncogenic changes that remain after fibrosis reversal will require a lifetime of patient surveillance. Equally plausible is that some patients with advanced disease will benefit from regenerative therapies aimed at restoring liver function and increasing transplant-free survival. Although regenerative therapies, such as mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4) inhibitors (69), have largely yet to progress beyond animal models, a phase II trial evaluating transplantation of hepatocytes into lymph nodes to supplement liver function (70) may prove another fascinating cellular therapy option. Perhaps as interesting will be if regenerative therapies themselves demonstrate antifibrotic potential, a response that is seen in patients whose HCV is cured. While the suppression of regeneration in fibrotic livers, via mechanisms such as TGF-β signalling (71), have long been recognised, recent work has further demonstrated that inhibition of microfibril-associated glycoprotein 4 (MFAP4), an ECM protein that interacts with integrins, both reduces fibrosis and increases regeneration in mice (72).

6 Conclusion

We are at the beginning of what can be expected to be a challenging phase in the development of a liver antifibrotic toolbox that adequately treats all patients across aetiology, stage of disease and across the many, as yet to be fully understood, stratifiers. Whether functional restoration is possible is still unclear. Nevertheless, we can celebrate the current successes with metabolic therapies that appear to reverse fibrosis in some MASH patients without worsening steatohepatitis. As we continue to push the therapeutic boundaries into cirrhosis, the value of reducing fibrosis as the sole therapeutic goal will also become clearer as long-term patient morbidity and mortality data become available over the coming decade.

Statements

Data availability statement

All relevant data is contained within the article: The original contributions presented in the review are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

QW: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Kenny Moore, Julian Maller, Sarah Batey, Jack Castle, Leanne Hodson, Eduardo Martins, Scott Friedman, and Chinwe Ukomadu for providing critical reading. Writing and editorial assistance was provided by Cherry Bwalya of Cherry B Enterprises Ltd and Fiona Weston of Fiona Weston Editorial Services Ltd, funded by Ochre Bio, according to the Good Publication Practice guidelines.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgstr.2025.1704078/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Devarbhavi H Asrani SK Arab JP Nartey YA Pose E Kamath PS . Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J Hepatol. (2023) 79:516–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.03.017

2

Guo Z Wu D Mao R Yao Z Wu Q Lv W . Global burden of MAFLD, MAFLD-related cirrhosis and MASH-related liver cancer from 1990 to 2021. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:7083. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-91312-5

3

Taylor RS Taylor RJ Bayliss S Hagström H Nasr P Schattenberg JM et al . Association between fibrosis stage and outcomes of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. (2020) 158:1611–25.e12. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.043

4

Harrison SA Wong VW Okanoue T Bzowej N Vuppalanchi R Younes Z et al . Selonsertib for patients with bridging fibrosis or compensated cirrhosis due to NASH: results from randomised phase III STELLAR trials. J Hepatol. (2020) 73:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.02.027

5

Harrison SA Goodman Z Jabbar A Vemulapalli R Younes ZH Freilich B et al . A randomised, placebo-controlled trial of emricasan in patients with NASH and F1–F3 fibrosis. J Hepatol. (2020) 72:816–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.11.024

6

Loomba R Noureddin M Kowdley KV Kohli A Sheikh A Neff G et al . Combination therapies including cilofexor and firsocostat for bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis attributable to NASH. Hepatology. (2021) 73:625–43. doi: 10.1002/hep.31622

7

US National Library of Medicine . ClinicalTrials.gov (2025). Available online at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02548351 (Accessed December 17, 2025).

8

Anstee QM Neuschwander-Tetri BA Wai-Sun Wong V Abdelmalek MF Rodriguez-Araujo G Landgren H et al . Cenicriviroc lacked efficacy to treat liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: AURORA phase III randomised study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2024) 22:124–34.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.003

9

Chalasani N Abdelmalek MF Garcia-Tsao G Vuppalanchi R Alkhouri N Rinella M et al . Effects of belapectin, an inhibitor of galectin-3, in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Gastroenterology. (2020) 158:1334–45.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.296

10

Harrison SA Abdelmalek MF Caldwell S Shiffman ML Diehl AM Ghalib R et al . Simtuzumab is ineffective for patients with bridging fibrosis or compensated cirrhosis caused by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. (2018) 155:1140–53. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.006

11

Harrison SA Bedossa P Guy CD Schattenberg JM Loomba R Taub R et al . A phase 3, randomised, controlled trial of resmetirom in NASH with liver fibrosis. N Engl J Med. (2024) 390:497–509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2309000

12

US Food and Drug Administration . Noncirrhotic nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with liver fibrosis: developing drugs for treatment: guidance for industry (2018). Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/media/119044/download (Accessed December 17, 2025).

13

European Medicines Agency . Reflection paper on regulatory requirements for the development of medicinal products for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (2023). Available online at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/reflection-paper-regulatory-requirements-development-medicinal-products-non-alcoholic-steatohepatitis-nash_en.pdf (Accessed December 17, 2025).

14

Sanyal AJ Newsome PN Kliers I Østergaard LH Long MT Kjær MS et al . Phase 3 trial of semaglutide in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. (2025) 92:2089–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2413258

15

US Food and Drug Administration FDA . FDA approves treatment for serious liver disease known as ‘MASH’ (2025). Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-treatment-serious-liver-disease-known-mash (Accessed December 17, 2025).

16

Noureddin M Rinella ME Chalasani NP Neff GW Lucas KJ Rodriguez ME et al . Efruxifermin in compensated liver cirrhosis caused by MASH. N Engl J Med. (2025) 392:2413–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2502242

17

US Food and Drug Administration . Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with compensated cirrhosis: developing drugs for treatment: guidance for industry (2019). Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/media/127738/download (Accessed December 17, 2025).

18

Hendershot CS Bremmer MP Paladino MB Kostantinis G Gilmore TA Sullivan NR et al . Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with alcohol use disorder: a randomised clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. (2025) 82:395–405. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.4789

19

Loomba R Bedossa P Grimmer K Kemble G Bruno Martins E McCulloch W et al . Denifanstat for the treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2024) 9:1090–100. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(24)00246-2

20

Francque SM Bedossa P Ratziu V Anstee QM Bugianesi E Sanyal AJ et al . A randomized, controlled trial of the pan-PPAR agonist lanifibranor in NASH. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385:1547–58. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2036205

21

US National Library of Medicine . ClinicalTrials.gov (2025). Available online at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04849728 (Accessed December 17, 2025).

22

GBD 2017 Cirrhosis Collaborators . The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2020) 5:245–66. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30349-8

23

Boehringer Ingelheim . Boehringer Ingelheim begins clinical development of first-in-class treatment for fibrotic diseases (2023). Available online at: https://www.boehringer-ingelheim.com/science-innovation/human-health-innovation/il-11-inhibitor-antibody-clinical-development-launched?hl=en-GB (Accessed December 17, 2025).

24

Alentis Therapeutics . Alentis announces positive topline results from two studies of lixudebart (ALE.F02) in patients with ANCA-RPGN and advanced liver fibrosis (2025). Available online at: https://alentis.ch/alentis-announces-positive-topline-results-from-two-studies-of-lixudebart-ale-f02-in-patients-with-anca-rpgn-and-advanced-liver-fibrosis/?hl=en-GB (Accessed December 17, 2025).

25

Boehringer Ingelheim . Boehringer Ingelheim seals new oncology antibody partnership and reports progress in several pipeline projects (2025). Available online at: https://www.boehringer-ingelheim.com/us/science-innovation/human-health-innovation/new-partnership-and-significant-pipeline-progress (Accessed December 17, 2025).

26

Brennan PN MacMillan M Manship T Moroni F Glover A Troland D et al . Autologous macrophage therapy for liver cirrhosis: a phase 2 open-label randomised controlled trial. Nat Med. (2025) 31:979–87. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03406-8

27

Mitra A Barua A Huang L Ganguly S Feng Q He B . From bench to bedside: the history and progress of CAR T cell therapy. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1188049. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1188049

28

Friedman SL . Can we talk? The cryptic communications of hepatic stellate cells in lipid metabolism. Cell Metab. (2025) 37:794–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2025.03.008

29

Xiong H Guo J . Targeting hepatic stellate cells for the prevention and treatment of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma: strategies and clinical translation. Pharmaceuticals. (2025) 18:507. doi: 10.3390/ph18040507

30

Yashaswini CN Cogliati B Qin T To T Williamson T Papp TE et al . In vivo anti-FAP CAR T therapy reduces fibrosis and restores liver homeostasis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. bioRxiv. (2025), 2025.02.25.640143. doi: 10.1101/2025.02.25.640143. preprint.

31

Pliant Therapeutics . Pliant Therapeutics announces successful completion of PLN-1474 phase 1 study and development transition to global pharmaceutical partner (2021). Available online at: https://ir.pliantrx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/pliant-therapeutics-announces-successful-completion-pln-1474 (Accessed December 17, 2025).

32

Qosa H de Oliveira CHMC Cizza G Lawitz EJ Colletti N Wetherington J et al . Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of BMS-986263, a lipid nanoparticle containing HSP47 siRNA, in participants with hepatic impairment. Clin Transl Sci. (2023) 16:1791–802. doi: 10.1111/cts.13581

33

Lawitz EJ Shevell DE Tirucherai GS Du S Chen W Kavita U et al . BMS-986263 in patients with advanced hepatic fibrosis: 36-week results from a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Hepatology. (2022) 75:912–23. doi: 10.1002/hep.32181

34

US National Library of Medicine . ClinicalTrials.gov (2024). Available online at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04267393 (Accessed December 17, 2025).

35

Aslanis V Gray M Slack RJ Zetterberg FR Tonev D Phung D et al . Single-dose pharmacokinetics and safety of the oral galectin-3 inhibitor, selvigaltin (GB1211), in participants with hepatic impairment. Clin Drug Investig. (2024) 44:773–87. doi: 10.1007/s40261-024-01395-7

36

US National Library of Medicine . ClinicalTrials.gov (2021). Available online at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04607655 (Accessed December 17, 2025).

37

Loomba R Adams LA . The 20% rule of NASH progression: the natural history of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis caused by NASH. Hepatology. (2019) 70:1885–88. doi: 10.1002/hep.30946

38

Raverdy V Tavaglione F Chatelain E Lassailly G De Vincentis A Vespasiani-Gentilucci U et al . Data-driven cluster analysis identifies distinct types of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Nat Med. (2024) 30:3624–33. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03283-1

39

Ratziu V Sanyal A Harrison SA Wong VW Francque S Goodman Z et al . Cenicriviroc treatment for adults with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis: final analysis of the phase 2b CENTAUR study. Hepatology. (2020) 72:892–905. doi: 10.1002/hep.31108

40

Ghazanfar H Javed N Qasim A Zacharia GS Ghazanfar A Jyala A et al . Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis and progression to hepatocellular carcinoma: a literature review. Cancers. (2024) 16:1214. doi: 10.3390/cancers16061214

41

DiStefano JK . NAFLD and NASH in postmenopausal women: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Endocrinology. (2020) 161:bqaa134. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqaa134

42

Gulati R Moylan CA Wilder J Wegermann K . Racial and ethnic disparities in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Metab Target Organ Damage. (2024) 4:9. doi: 10.20517/mtod.2023.45

43

Seko Y Yamaguchi K Yano K Takahashi Y Takeuchi K Kataoka S et al . The additive effect of genetic and metabolic factors in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:17608. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-22729-5

44

Armisen J Rauschecker M Sarv J Liljeblad M Wernevik L Niazi M et al . AZD2693, a PNPLA3 antisense oligonucleotide, for the treatment of MASH in 148M homozygous participants: two randomised phase I trials. J Hepatol. (2025) 83:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2024.12.046

45

US National Library of Medicine . ClinicalTrials.gov (2025). Available online at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05809934 (Accessed December 17, 2025).

46

US National Library of Medicine . ClinicalTrials.gov (2025). Available online at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05648214 (Accessed December 17, 2025).

47

Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals Inc . Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals gains full rights to NASH candidate ARO-PNPLA3 with promising phase 1 results (2023). Available online at: https://arrowheadpharma.com/news-press/arrowhead-pharmaceuticals-gains-full-rights-to-nash-candidate-aro-pnpla3-with-promising-phase-1-results/?hl=en-GB (Accessed December 17, 2025).

48

Luukkonen PK Sakuma I Gaspar RC Mooring M Nasiri A Kahn M et al . Inhibition of HSD17B13 protects against liver fibrosis by inhibition of pyrimidine catabolism in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2023) 120:e2217543120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2217543120

49

US National Library of Medicine . ClinicalTrials.gov (2025). Available online at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05583344 (Accessed December 17, 2025).

50

US National Library of Medicine . ClinicalTrials.gov (2025). Available online at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05519475 (Accessed December 17, 2025).

51

Inipharm . Inipharm to present phase 1 pharmacokinetic data for INI-822 (2024). Available online at: https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/inipharm-to-present-phase-1-pharmacokinetic-data-for-ini-822 (Accessed December 17, 2025).

52

No authors listed . Phase 3 ESSENCE trial: semaglutide in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). (2024) 20:6–7. Available online at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39896971/.

53

US FDA Drug Safety Communication . Serious liver injury being observed in patients without cirrhosis taking Ocaliva (obeticholic acid) to treat primary biliary cholangitis (2024). Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/serious-liver-injury-being-observed-patients-without-cirrhosis-taking-ocaliva-obeticholic-acid-treat (Accessed December 17, 2025).

54

Ratziu V Charlton M . Rational combination therapy for NASH: insights from clinical trials and error. J Hepatol. (2023) 78:1073–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.12.025

55

Loomba R Hartman ML Lawitz EJ Vuppalanchi R Boursier J Bugianesi E et al . Tirzepatide for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis with liver fibrosis. N Engl J Med. (2024) 391:299–310. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2401943

56

Novo Nordisk . Novo Nordisk successfully completes phase 1b/2a trial with subcutaneous amycretin in people with overweight or obesity (2025). Available online at: https://www.novonordisk.com/news-and-media/news-and-ir-materials/news-details.html?id=915251&hl=en-GB (Accessed December 17, 2025).

57

Boehringer Ingelheim . Boehringer receives US FDA Breakthrough Therapy designation and initiates two phase III trials in MASH for survodutide (2024). Available online at: https://www.boehringer-ingelheim.com/human-health/metabolic-diseases/survodutide-us-fda-breakthrough-therapy-phase-3-trials-mash?hl=en-GB (Accessed December 17, 2025).

58

Jastreboff AM Kaplan LM Frías JP Wu Q Du Y Gurbuz S et al . Triple-hormone-receptor agonist retatrutide for obesity—a phase 2 trial. N Engl J Med. (2023) 389:514–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2301972

59

Eli Lilly and Company . Lilly’s triple agonist, retatrutide, delivered weight loss of up to an average of 71.2 lbs along with substantial relief from osteoarthritis pain in first successful Phase 3 trial. Available online at: https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lillys-triple-agonist-retatrutide-delivered-weight-loss-average (Accessed December 12, 2025).

60

Lassailly G Caiazzo R Buob D Pigeyre M Verkindt H Labreuche J et al . Bariatric surgery reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in morbidly obese patients. Gastroenterology. (2015) 149:379–88. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.014

61

Rockey DC . Fibrosis reversal after hepatitis C virus elimination. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. (2019) 35:137–44. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000524

62

Harrison SA Frias JP Neff G Abrams GA Lucas KJ Sanchez W et al . Safety and efficacy of once-weekly efruxifermin versus placebo in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (HARMONY): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2023) 8:1080–93. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00272-8

63

Loomba R Sanyal AJ Kowdley KV Bhatt DL Alkhouri N Frias JP et al . Randomised, controlled trial of the FGF21 analogue pegozafermin in NASH. N Engl J Med. (2023) 389:998–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2304286

64

No authors listed . Once-monthly efimosfermin alfa (BOS-580) in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis with F2/F3 fibrosis: results from a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). (2024) 20:15–6. Available online at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39896968/.

65

Sánchez-Torrijos Y Fernández-Álvarez P Rosales JM Pérez-Estrada C Alañón-Martínez P Rodríguez-Perálvarez M et al . Prognostic implications of recompensation of decompensated cirrhosis after SVR in patients with hepatitis C. J Hepatol. (2025) 83:652–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2025.02.041

66

Ioannou GN . HCC surveillance after SVR in patients with F3/F4 fibrosis. J Hepatol. (2021) 74:458–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.10.016

67

Alkhouri N Vuppalanchi R Noureddin M Shifmann M Lawitz EJ Mena E et al . LBO-006 Belapectin at 2 mg/kg/LBW reduces varices development in MASH cirrhosis with portal hypertension: results from the NAVIGATE trial. J Hepatol. (2025) 82:S12–13. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(25)00315-0

68

Wijayasiri P Astbury S Kaye P Oakley F Alexander GJ Kendall TJ et al . Role of hepatocyte senescence in the activation of hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis progression. Cells. (2022) 11:2221. doi: 10.3390/cells11142221

69

Zwirner S Abu Rmilah AA Klotz S Pfaffenroth B Kloevekorn P Moschopoulou AA et al . First-in-class MKK4 inhibitors enhance liver regeneration and prevent liver failure. Cell. (2024) 187:1666–84.e26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.02.023

70

LyGenesis . LyGenesis announces first patient dosed in its phase 2a clinical trial of a first-in-class regenerative cell therapy for patients with end-stage liver disease (2024). Available online at: https://www.lygenesis.com/media/press-releases/lygenesis-announces-first-patient-dosed-in-its-phase-2a-clinical-trial-of-a-first-in-class-regenerative-cell-therapy-for-patients-with-end-stage-liver-disease/ (Accessed December 17, 2025).

71

Fabregat I Moreno-Càceres J Sánchez A Dooley S Dewidar B Giannelli G et al . TGF-β signalling and liver disease. FEBS J. (2016) 283:2219–32. doi: 10.1111/febs.13665

72

Iakovleva V Wuestefeld A Ong ABL Gao R Kaya NA Lee MY et al . MFAP4: a promising target for enhanced liver regeneration and chronic liver disease treatment. NPJ Regener Med. (2023) 8:63. doi: 10.1038/s41536-023-00337-9

Summary

Keywords

antifibrotics, combination therapies, liver fibrosis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), metabolic therapies, precision medicine

Citation

Wills Q (2026) MASH and the race for liver antifibrotics. Front. Gastroenterol. 4:1704078. doi: 10.3389/fgstr.2025.1704078

Received

12 September 2025

Revised

19 December 2025

Accepted

29 December 2025

Published

23 January 2026

Volume

4 - 2025

Edited by

Joel E. Lavine, Columbia University, United States

Reviewed by

Mrigya Babuta, University of Hyderabad, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wills.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Quin Wills, quinwills@ochre-bio.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.