- 1Molecular Immunology Unit, Department of Experimental Oncology and Molecular Medicine, Fondazione IRCCS “Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori”, Milan, Italy

- 2Department of Molecular Virology, Immunology and Medical Genetics, Wexner Medical Center and Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

- 3Department of Anesthesiology, Wexner Medical Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

Invariant natural killer T cells (iNKT cells) are CD1d-restricted, lipid antigen-reactive T lymphocytes with immunoregulatory functions. iNKT cell development in the thymus proceeds through subsequent stages, defined by the expression of CD44 and NK1.1, and is dictated by a unique gene expression program, including microRNAs. Here, we investigated whether miR-155, a microRNA involved in differentiation of most hematopoietic cells, played any role in iNKT cell development. To this end, we assessed the expression of miR-155 along iNKT cell maturation in the thymus, and studied the effects of miR-155 on iNKT cell development using Lck-miR-155 transgenic mice, which over express miR-155 in T cell lineage under the lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (Lck) promoter. We show that miR-155 is expressed by newly selected immature wild-type iNKT cells and turned off along iNKT cells differentiation. In transgenic mice, miR-155 over-expression resulted in a substantial block of iNKT cell maturation at Stage 2, in the thymus toward an overall reduction of peripheral iNKT cells, unlike mainstream T cells. Furthermore, the effects of miR-155 over-expression on iNKT cell differentiation were cell autonomous. Finally, we identified Ets1 and ITK transcripts as relevant targets of miR-155 in iNKT cell differentiation. Altogether, these results demonstrate that a tight control of miR-155 expression is required for the development of iNKT cells.

Introduction

Invariant natural killer T (iNKT cells) cells are a unique T cell lineage characterized by the expression of a conserved semi-invariant αβ TCR, NK receptors, and by innate effector properties (1). NKT semi-invariant TCR is composed of an invariant α chain (Vα24Jα18 in human beings and Vα14Jα18 in mice), which couples with a limited repertoire of TCR β chains (preferentially Vβ11 in humans and Vβ2, Vβ7, and Vβ8.2 in mouse) (1). The semi-invariant TCR recognizes both self and bacterial glycolipid ligands presented by the antigen-presenting molecule CD1d (2), as well as at least one endogenous peptide involved in multiple disease conditions (3). This wide recognition confers iNKT cells the ability to act as regulators of immune homeostasis (4), as well as sentinels to invading pathogens. Accordingly, iNKT cells play important functions in autoimmune diseases, cancer, infection, and inflammation.

As conventional T lymphocytes, iNKT cells are generated in the thymus from CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP) precursors, upon stochastic rearrangement of the invariant TCR and positive selection by CD1d-expressing DP thymocytes (5, 6). Positively selected iNKT cells follow a defined developmental program, involving three subsequent stages defined by the expression of CD44 and NK1.1 and the down-regulation of the heat stable antigen (HSA or CD24). In particular, Stage 1 (CD24loCD44loNK1.1−) iNKT cells proliferate extensively to expand their pool; Stage 2 (CD24loCD44hiNK1.1−) iNKT cells become effector-memory cells; Stage 3 (CD24loCD44hiNK1.1+) iNKT cells up-regulate NK cell receptors such as NK1.1 and become terminally differentiated thymic residents (7, 8). Many factors have been described as crucial for this maturation path, including transcription factors (such as c-Myc, Egr2, Ets1, PLZF, T-bet), signal transducers (such as ITK and Irf1), and other molecules (as WASp and Osteopontin) [reviewed in Ref. (9)]. Emigration of iNKT cells from the thymus occurs mostly at Stage 2 through the lymphotoxin-β and the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. The peripheral acquisition of NK markers by iNKT cells is gained via CD1d-dependent mechanisms, but the complete functional maturation requires a final step in which the correct levels of SHP-1 phosphatase in iNKT cells are tuned by CD1d-expressing DCs (10).

MicroRNAs are small endogenous RNAs that play important gene-regulatory roles by pairing to the mRNAs of protein-coding genes to direct their posttranscriptional repression (11). Despite their relatively recent identification, growing evidence indicates that microRNAs are crucial controllers of the programs directing cell differentiation in the immune system, as demonstrated in mice mutants for Dicer, the RNase III enzyme that generates functional microRNAs. In particular, conditional deletion of Dicer causes significant impairment in the generation of functional regulatory T cell subsets, such as FoxP3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells (12) and iNKT cells (13). The search for the relevant individual microRNA involved in Treg development and function identified micro-RNA155 (miR-155) as a key factor for Treg maintenance. miR-155 is processed by Dicer from BIC, a non-coding transcript highly expressed in B and T cells and in monocytes/macrophages. In Treg, miR-155 is directly regulated by FoxP3 and targets suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1), leading to increased sensitivity of IL-2R to IL-2 (14, 15).

On the iNKT cell side, two groups identified miR-150 as the essential microRNA for thymic and peripheral iNKT cell maturation (16, 17). Notably, Zheng et al. described a partial block in thymic and peripheral iNKT maturation in miR-150 KO mice, whereas Lanier’s group showed a substantial reduction of iNKT cells in mice over-expressing miR-150. These data suggest that a dynamic and tightly regulated expression of miR-150 is required for optimal iNKT cell development.

Beyond the above-described role in Treg function, miR-155 has gained attention for its role in cancer. A moderate increase of miR-155 levels has been observed in many types of malignancies of B cell or myeloid origin, and some of us have shown that transgenic over-expression of miR-155 in mice results in cancer (18).

Given the relevance of miR-155 for the homeostasis of the immune system, in this study, we investigated the role of miR-155 in iNKT cells. Surprisingly, we found that miR-155 over-expression deeply impacts iNKT cell development, a result that stresses the importance of tight regulation of miRNAs for their correct functioning.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 wild-type (wt) mice were purchased from Charles River (Italy). Mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions at the animal facility of Fondazione IRCCS “Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori”. Animal experiments were authorized by the Institute Ethical Committee and performed in accordance to institutional guidelines and national law (DL116/92). Lck-miR-155 tg mice were generated as previously described (19) and were provided by Dr. Carlo Maria Croce (Wexner Medical Center and Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University).

Cell Preparations, Antibodies, Flow Cytometry, and Cell Sorting

Single-cell suspensions from thymus, liver, spleen, and bone marrow (BM) were prepared as previously described (6).

PerCPCy5.5 anti-HSA (M1/69), APC anti-TCRβ (H57-597), PE-Cy7 anti-NK1.1 (PK136), FITC anti-CD44 (IM7), FITC anti-CD45.1 (A20), PE-Cy7 anti-CD4 (GK1.5), and APC anti-CD8 (53-6.7) were purchased from eBioscience. PBS-57-loaded CD1d-tetramers were kindly provided by NIH Tetramer Core Facility at Emory University (task order # 14724). Surface staining was performed by incubating antibodies and tetramers at 5 μg/ml on ice for 30 min in PBS containing 2% FBS. Flow cytometry data were acquired on a LSR Fortessa (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed with FlowJo software (version 8.8.7; Treestar Inc.).

Invariant natural killer T cells pooled from thymocytes from wt and Lck-miR-155 tg mice were sorted using a FACSaria (Becton Dickinson) as:

HSA−TCRβ+tetramer+CD44loNK1.1− Stage 1 cells,

HSA−TCRβ+tetramer+CD44hiNK1.1− Stage 2 cells,

HSA−TCRβ+tetramer+CD44hiNK1.1+ Stage 3 cells.

Purity after sorting assessed around 98%.

Real Time RT-PCR

Fifty nanograms of total RNA, isolated by using the miRNeasy miRNA isolation kit (Qiagen), were subjected to reverse transcription according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative Real time RT-PCR analysis for miR-155 (assay ID: 002571) was performed according to the TaqMan MicroRNA Assays (Applied Biosystems) and samples normalized by evaluating RNA U6 (assay ID: 001973) expression.

RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions (RNeasy MICROKIT, Qiagen) and reverse transcribed using High-Capacity® cDNA Reverse Transcription Kits (Applied Biosystem). Real time RT-PCR were performed on 7900 HT (Applied Biosystem), using TaqMan® Fast Universal PCR masterMix (Applied Biosystem). Assays (Ets1 assay ID: Mm01175819_m1; Itk assay ID: Mm00439862_m1) and samples were normalized by evaluating HPRT1 (assay ID: Mm01545399_m1) expression. Results were obtained using the comparative Ct method.

BM Transplantation

Bone marrow cells were obtained by flushing the cavity of femurs from donor mice. Cells from Lck-miR-155 tg mice were mixed at 1:1 ratio with CD45.2 wt cells. Lck-miR-155 recipient mice were lethally γ irradiated with 1000 cGy (given as a split dose 500 + 500 cGy with a 3-h interval). Two hours later, mice were injected i.v. with 107 mixed BM cells. Recipient mice received 0.4 mg/ml gentalyn in the drinking water starting 1 week before irradiation and maintained thereafter.

Luciferase Assay

The 3′-UTRs of human ITK and ETS1 cloned downstream of Renilla luciferase gene were purchased from Switchgear Genomics and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Renilla luciferase assays were performed in MEG-01 cells 48 h after transfection (n = 10). The miR-155 target sites present on ITK-3′-UTR and ETS1-3′-UTR target site 1 and target site 2 (underlined) were mutated as indicated below (underlined and bold) using the shown corresponding primers. The mutations were prepared using QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit from Agilent following manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing of the clones was done to confirm the presence of each mutation. For ETS1, the double mutant clone (ETS-1-M1, 2) was prepared on the clone were the first miR-155 target site was previously mutated.

ITK original sequence:

GGATATGTCCTCATTCCATAGAGCATTAGAAGCTGCCACCAGCCCAGG

ITK mutated sequence (M):

GGATATGTCCTCATTCCATAGAGCGGTAGAAGCTGCCACCAGCCCAGG

Primers used for mutation:

ITKS 5′-GTCCTCATTCCATAGAGCGGTAGAAGCTGCCACCAG

ITKAS 5′-CTGGTGGCAGCTTCTACCGCTCTATGGAATGAGGAC

ETS original target site 1:

GGACTTAATGTTGAGCTAAGAAGCATTAAGTCTTTGAACTGAATGTATTTTGCATCCC

ETS mutated target site 1 (M1):

GGACTTAATGTTGAGCTAAGAAGCGGTAAGTCTTTGAACTGAATGTATTTTGCATCCC

Primers used for mutation:

ETS1S

5′-GGACTTAATGTTGAGCTAAGAAGCGGTAAGTCTTTGAACTGAATG

ETS1AS

5′-CATTCAGTTCAAAGACTTACCGCTTCTTAGCTCAACATTAAGTCC

ETS original target site 2:

GGAGATGAACACTCTGGGTTTTACAGCATTAACCTGCCTAACCTTCATGGTG

ETS mutated target site 2 (M2):

GGAGATGAACACTCTGGGTTTTACAGCGGTAACCTGCCTAACCTTCATGGTG

Primers used for mutation of target site 2 (M2):

ETS2S 5′-GAACACTCTGGGTTTTACAGCGGTAACCTGCCTAACC

ETS2AS 5′-GGTTAGGCAGGTTACCGCTGTAAAACCCAGAGTGTTC

The miR-Control and miR-155 were purchased from Life Technologies (catalog number AM17110 and PM12601, respectively). The miR-Control molecule is a random sequence, which has been extensively tested in human cell lines and tissues and has no known target transcripts. The miR-Control was used as a baseline for evaluating the effects of miR-155 on Est1 and Itk transcripts.

Statistical Analysis

The graphs and the analysis of data were performed using Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Results are expressed as means ± SEM or SD. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test with confidence intervals of 95%. Data were considered significantly different at p < 0.05 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005 by Student’s t-test).

Results

miR-155 is Down-Modulated Along Thymic iNKT Cell Maturation

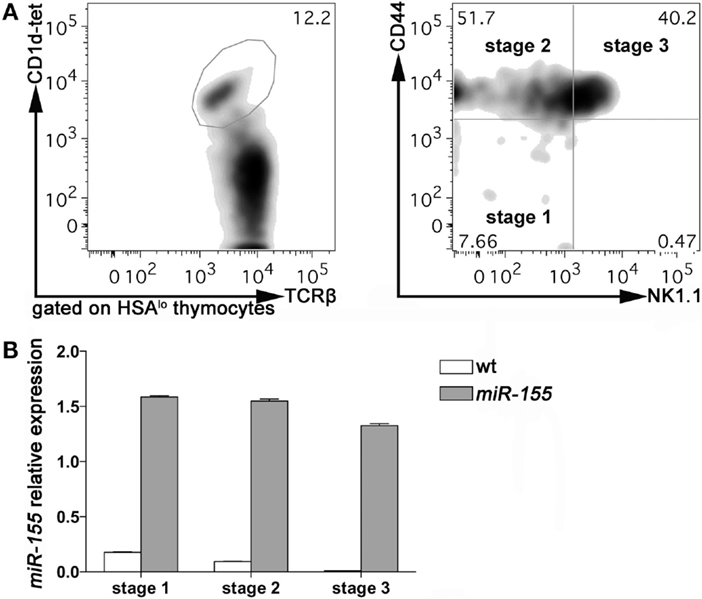

To evaluate the expression of miR-155 in thymic iNKT cells at different stages of maturation, we sorted Stage 1, Stage 2, and Stage 3 iNKT cells from 8 weeks old wild-type (wt) C57BL/6 mice, according to PBS-57-loaded CD1d-tetramers, TCRβ, NK1.1, and CD44 staining. Consistently with published literature, Stage 2 and 3 accounted for the majority of iNKT cells at this age, with Stage 1 representing <10% of HSA-negative iNKT cells (Figure 1A). The relative expression of miR-155 (compared to endogenous control small nuclear RNA U6) was higher in Stage 1, and decreased progressively in Stage 2 and Stage 3 iNKT cells (Figure 1B, white bars). These data indicated that miR-155 is down-modulated along iNKT cell maturation, suggesting that miR-155 may be important for early events in iNKT cell lineage instruction, but becomes irrelevant or even detrimental for further maturation. In conventional T cells, miR-155 is expressed at higher levels by CD4+ and CD8+ single positive (SP) cells than by CD4−CD8− double negative (DN) and CD4+CD8+ DP thymocytes (Figure S1A in Supplementary Material) and (20), indicating a different regulation exerted on and by miR-155 in iNKT and T cell subsets.

Figure 1. miR-155 expression in Stage 1, 2, and 3 wt and Lck-miR-155 tg iNKT cells. (A) Representative plots of the sorting strategy employed to sort wt and miR-155 tg thymic iNKT cells. iNKT cells were identified as HSA−TCRβ+CD1d-tetramer+ thymocytes, and sorted as Stage 1 (CD44−NK1.1−), Stage 2 (CD44+NK1.1−), and Stage 3 (CD44+NK1.1+) cells. (B) Evaluation of miR-155 levels in sorted cells, as assessed by RT-PCR. White bars represent wt iNKT cells, gray bars represent Lck-miR-155 tg iNKT cells. The graph shows the pooled results of two independent experiments (in which six mice per group were combined).

To assess whether the regulation of miR-155 along iNKT cell maturation in the thymus is relevant for the development of these cells, we analyzed the effects of a sustained and prominent expression of miR-155 on iNKT cells development, taking advantage from the Lck-miR-155 transgenic (tg) mice (19). These mice express miR-155 at high levels in T lymphocytes beginning at the DN stage (Figure S1B in Supplementary Material), including iNKT cells. Compared to their wt counterparts, Stage 1 iNKT cells from Lck-miR-155 tg mice expressed sevenfold more miR-155, and expression was maintained at the same levels in Stage 2 and 3 (Figure 1B, gray bars). Lck-miR-155 tg mice thus represent the ideal model to study the significance of miR-155 down-regulation in iNKT cell development.

Thymic and Peripheral iNKT Cell Maturation is Impaired in Lck-miR-155 Mice

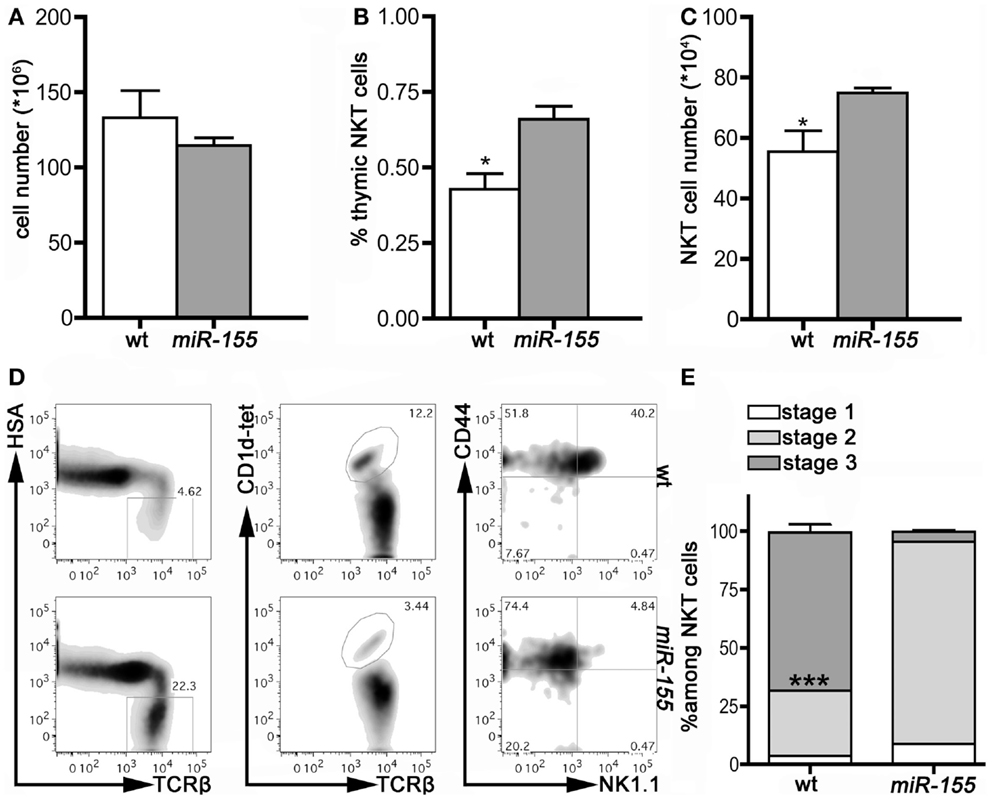

We then assessed miR-155 involvement in iNKT cell development by comparing thymus and peripheral organs of 8 weeks old wt and Lck-miR-155 tg mice, in terms of iNKT cell frequency, numbers, and phenotype. Interestingly, tg thymi were normal in total cell numbers (Figure 2A), but displayed alterations in the relative distribution of thymocytes in the DN, DP, and SP compartments (not shown), reasonably caused by miR-155 deregulation in developing tg thymocytes. Thymi from tg mice contained significantly more iNKT cells than wt mice (75 ± 32 × 104 cells in tg versus 55 ± 14 × 104 cells in wt mice, p = 0.033) (Figures 2B,C), but the great majority of the tg iNKT pool was constituted by cells with an immature phenotype. In fact, whereas wt iNKT cells were mostly Stage 3 NK1.1+ cells, tg iNKT cells encompassed mostly Stage 2 NK1.1− cells (Figures 2D,E), with only few mature NK1.1+ cells.

Figure 2. iNKT cells from Lck-miR-155 tg thymi display an immature phenotype. (A) Total cell number of thymi isolated from wt (white bar) and Lck-miR-155 tg mice (gray bar). (B) Percentage and (C) absolute number of iNKT cells in the thymi of wt (white bar) and Lck-miR-155 tg mice (gray bar). (D) Representative plots of thymic iNKT cells from wt and tg mice. iNKT cells were identified as HSA−TCRβ+CD1d-tetramer+ thymocytes, and then analyzed for CD44 and NK1.1 expression. (E) Bars showing the relative distribution in Stage 1, 2, and 3 of wt and miR-155 tg iNKT cells. White color represents Stage 1, light gray represents Stage 2 and dark gray represents Stage 3 iNKT cells. One representative of three independent experiments with five mice per group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005, two-tailed Student’s t-test.

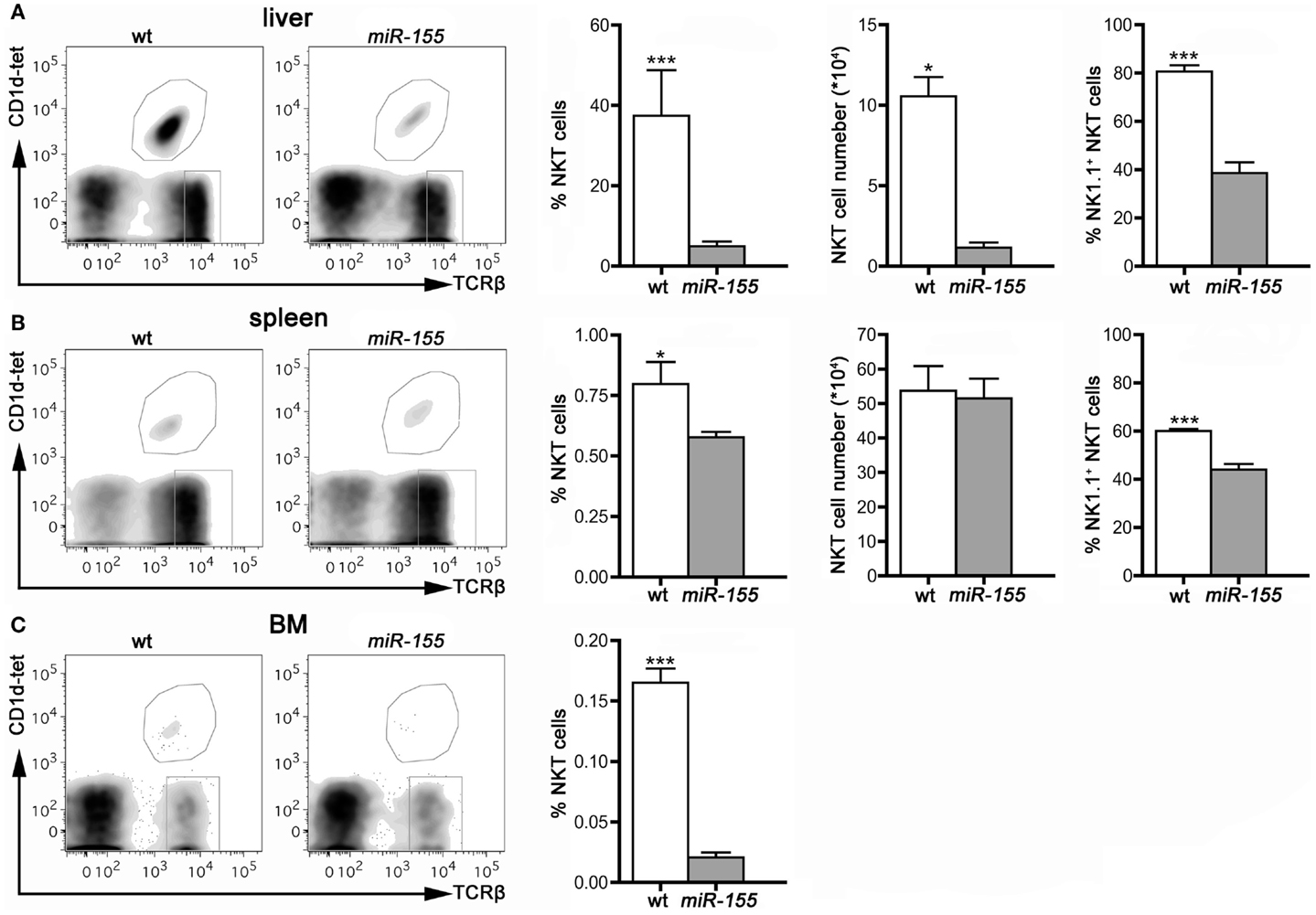

In contrast to the higher number of thymic iNKT cells, found in tg mice, peripheral iNKT cells were reduced in all the compartments analyzed, i.e., liver, spleen, and BM (Figures 3A–C), especially if analysis was restricted to mature NK1.1+ cells, in comparison to the wt counterparts.

Figure 3. iNKT cells are reduced in peripheral organs of Lck-miR-155 tg mice. Representative stainings and histograms summarizing iNKT cell frequency, absolute number, and NK1.1+ expression in liver (A), spleen (B) and bone marrow (C) of wt and Lck-miR-155 tg mice. iNKT cells were identified as TCRβ+CD1d-tetramer+ cells. One representative of three independent experiments with five mice per group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005, two-tailed Student’s t-test.

These results indicate that miR-155 over-expression in T cells arrests iNKT cell maturation at Stage 2 in the thymus and in the peripheral compartments, which results in an overall reduction of iNKT cells in periphery. Therefore, miR-155 critically regulates iNKT cell differentiation program.

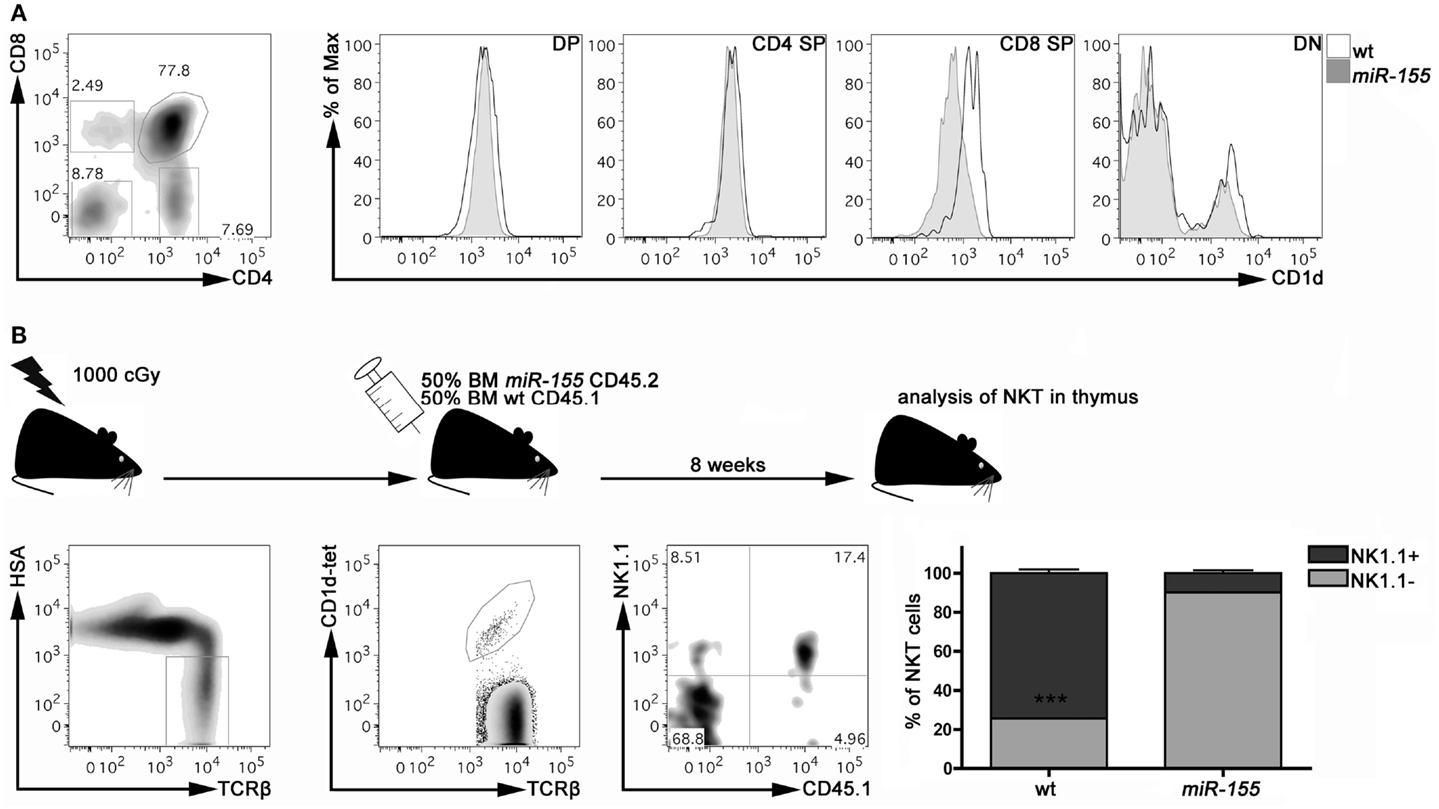

Defective Maturation of Thymic NKT Cells from Lck-miR-155 tg Mice is Cell Intrinsic

To dissect the mechanisms by which miR-155 over-expression impairs iNKT cell differentiation, we first ruled out that miR-155 over-expression might somehow affect thymic expression of CD1d, the major presenting molecule involved in iNKT cell generation. As shown in Figure 4A, DP, CD4+, and DN thymocytes from Lck-miR-155 tg and wt mice expressed similar levels of CD1d. CD8+ thymocytes from Lck-miR-155 tg mice displayed instead significantly lower levels of CD1d compared to the wt counterpart. As iNKT cells are positively selected by DP thymocytes and no existing data prove a relevant role for CD8+ thymocytes in the selection and maturation of iNKT cells, we have reasons to believe that iNKT cell generation is not affected by impaired CD1d expression in CD8+ thymocytes in Lck-miR-155 tg mice.

Figure 4. miR-155 over-expression intrinsically affects iNKT cell maturation in Lck-miR-155 tg mice. (A) Representative plot of thymic populations according to CD4 and CD8 expression, and CD1d expression on DP, CD4 SP, CD8 SP, and DN cells isolated form the thymus of wt (black line) and miR-155 tg (gray filled) mice. (B) Experimental scheme of mixed BM chimera generation. Eight weeks after transplantation, thymi were collected and frequency and maturation stage of wt (CD45.1) and miR-155 tg (CD45.2) NKT cells were evaluated. Plots are representative of one mouse of five. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.005, two-tailed Student’s t-test. DP, double positive; CD4 SP, CD4 single positive; CD8 SP, CD8 single positive; DN, double negative; BM, bone marrow.

To determine whether the iNKT cell developmental defect caused by miR-155 over-expression is instead cell autonomous, we verified whether the development of miR-155 over-expressing iNKT cells could be rescued by wt thymocytes in mixed BM chimeras. Lethally irradiated Lck-miR-155 tg mice were reconstituted with an equal mixture of BM cells derived from CD45.1 wt mice and CD45.2 Lck-miR-155 tg mice. As shown in Figure 4B, in the thymi of the BM chimeras the majority of iNKT cells derived from the CD45.1 wt BM were mature NK1.1+ cells. In contrast, iNKT cells derived from the CD45.2 Lck-miR-155 BM cells mostly displayed an immature NK1.1- phenotype.

Finally, we ruled out that iNKT cells from Lck-miR-155 tg mice might be characterized by altered homeostasis, impairing their differentiation program in the thymus. As determined by BrdU incorporation in vivo, miR-155 over-expression did not modify the proliferation of thymic iNKT cell in comparison with the wt counterpart (Figure S2 in Supplementary Material).

Thus, impaired iNKT cell maturation caused by miR-155 over-expression could not be rescued by wt thymocytes; in addition, iNKT cells derived from wt BM developed correctly in the thymic stroma of Lck-miR-155 tg mice. Collectively, these results indicate a cell-autonomous role for miR-155 in the control of iNKT cell differentiation.

Lck-miR-155 tg iNKT Cells Fail to Up-Regulate Ets1 and Itk upon Maturation

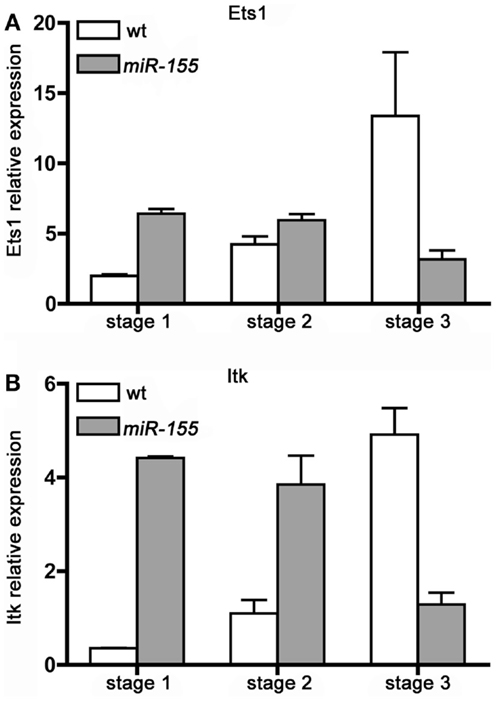

The search for the potential miR-155 targets in iNKT cells identified Ets1 and Itk (inducible T cell kinase) molecules as the most likely candidates. Ets1 is a member of the Ets winged helix-turn-helix transcription factor family. Itk belongs to the Tec family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases, which plays a significant role in signaling downstream of the TCR. Although in different cell types, both Ets1 (21) and Itk (22) have been shown to represent direct targets of miR-155 regulation. Both Ets1 KO (23, 24) and Itk KO (25) mice display a severe impairment in iNKT cells, characterized by an arrest at Stage 2 that closely resembles the condition of Lck-miR-155 tg mice. Considering the relevance of both Ets1 and Itk in iNKT differentiation and the regulatory roles exerted by miR-155 on these two genes, we investigated them further.

We determined the expression of Ets1 and Itk transcripts in Stage 1, 2, and 3, iNKT cells isolated from wt and Lck-miR-155 tg mice. As shown in Figure 5, wt iNKT cells up-regulate both transcripts upon maturation from Stage 1 to 2 and 3: in particular, Ets1 increases up to 13-fold from Stage 1 to Stage 3, whereas Itk has a 5-fold induction. In contrast, in iNKT cells from Lck-miR-155 tg mice, Stage 1 cells have a four to sixfold higher expression of both transcripts compared to the wt counterparts, but their expression decreases upon maturation, resulting in a severe reduction of Ets1 and Itk expression in Stage 3 cell compared to wt cells. The defective down-modulation of Ets1 and Itk at the Stage 1 and 2 of miR-155 tg iNKT cells might be due to the presence of a shorter isoform of their 3′UTR that may occur during differentiation/maturation (26).

Figure 5. iNKT cells over-expressing miR-155 fail to up-regulate Ets1 and Itk upon maturation. (A) Ets1 and (B) Itk transcripts expression level was evaluated in sorted Stage 1, 2, and 3 iNKT cells isolated from wt (white bars) and Lck-miR-155 tg (gray bars) mice. Along wt iNKT development both Ets1 and Itk are up modulated, mirroring the down-modulation of miR-155. On the contrary in miR-155 tg iNKT, the expression of both transcripts is impaired. Data are representative of two independent experiments, each counting five mice for group.

In the wt setting, Ets1 and Itk up-regulation along iNKT cell thymic maturation is paralleled by a concomitant decrease in miR-155 levels (Figure 1B); in tg iNKT cells, which over-express miR-155 (Figure 1B), expression of Ets1 and Itk is instead consistently down-modulated at least in Stage 3. These results strongly suggest the existence of a regulatory function exerted by miR-155 over Ets1 and Itk in iNKT cell maturation.

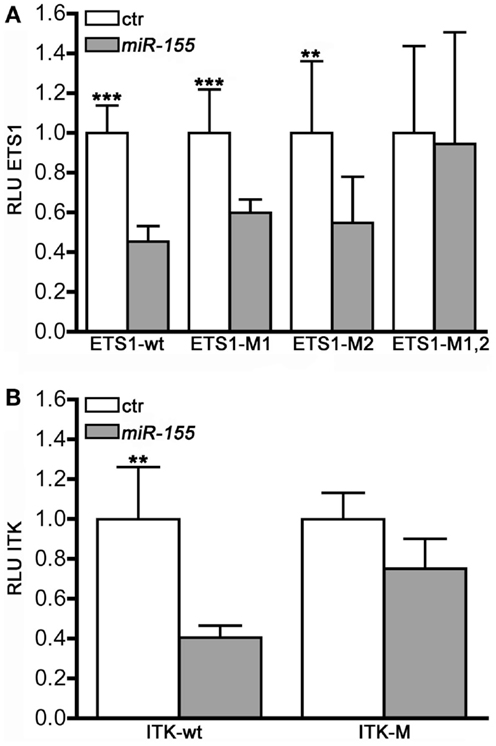

Ets1 and Itk are Direct miR-155 Targets in iNKT Cells

Function and immune response activities of miR-155 are conserved in both mouse and human (27). To further validate that miR-155 modulates iNKT cell maturation through the targeting of Ets1 and Itk transcripts, the 3′UTRs of Ets1 and Itk were cloned downstream of Renilla luciferase gene and the effects of miR-155 were assayed on luciferase reporter assays. Cotransfection of the wt constructs, or either Luciferase-Ets1-3′UTR or Luciferase-Itk-3′UTR, with miR-155 resulted in the reduction of the luciferase activity compared to the effects of miR-control. miR-155 over-expression also significantly reduced the expression of Luciferase-Ets1-3′UTR-M1 and Luciferase-Ets1-3′UTR-M2 constructs, each containing a single mutated miR-155 site, suggesting that each of the miR-155 target site in the Ets1 clone is functional. These effects were abolished when both putative miR-155 target seed sites were mutated on the Luciferase-Ets1-3′UTR (Figure 6A). Mutation of miR-155 target site on the Itk transcript also impaired the miR-155 downregulating effects on the Luciferase-Itk-3′UTR expression (Figure 6B). Altogether, these data demonstrate that miR-155 directly targets Ets1 and Itk transcripts, and further establish miR-155 as a key regulator of iNTK differentiation.

Figure 6. Ets1 and Itk are direct targets of miR-155. MEG-01 cells were co-transfected with luciferase reporter constructs containing either the wild-type or the mutated (A) ETS1-, and (B) ITK1-3′UTRs and with either miR-155 or miR-Control (ctr) and assessed for luciferase activity (RLU) 48 h after the transfection (n = 10).

Discussion

Invariant natural killer T cells are unconventional T cells, and, as such, follow a unique differentiation program. Upon positive selection by CD1d expressed on immature DP thymocytes, iNKT maturtion passes through three developmental stages according to CD44 and NK1.1 expression. This maturation process is strictly controlled by transcription factors, signals transduced (9), and microRNA (13).

Our study reveals for the first time a novel mechanism of control in iNKT cell maturation process, which involves the physiological decrease of miR-155, such to ensure the up-regulation of its targets (Itk and Ets1), and therefore proper iNKT lymphocyte maturation. We show that abundant and sustained expression of miR-155 in immature and mature T cells results in a dramatic defect in late-stage maturation of iNKT cells, and accordingly reduced number of iNKT cells in the peripheral compartments. Our data integrate previous studies on the control of iNKT cell physiology by microRNAs, and indicate that a complex and coordinated interaction with different microRNAs and their target is likely involved in the pathway of iNKT cell differentiation.

The crucial role exerted by miR-155 in regulating lymphocyte biology was demonstrated in a B cell restricted miR-155 transgenic mouse model. In these mice, the over-expression of miR-155 under the Eμ promoter caused uncontrolled pre-B cell proliferation followed by high-grade lymphoma/leukemia (18).

Interestingly, despite the dramatic consequences of miR-155 over-expression in B cells, none of the Lck-miR-155 tg mice under our observation developed thymomas or peripheral malignancies, suggesting that miR-155 regulates different targets in B and T lymphocytes, and that the targets in T cells might not necessary be tumor suppressor genes. It is also highly probable that the levels of miR-155 transgene expression under the Lck promoter did not reach the high levels reached by Eμ promoter in B cells. As the effects of the microRNAs are often dose dependent this might explain the lack of leukemogenesis in Lck-miR-155 tg mice.

Although the over-expression of miR-155 in Lck-miR-155 mice does not cause a neoplastic transformation, several studies highlighted the importance of a regulated expression of this microRNA in both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes (28). In particular, it was demonstrated that in CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells, miR-155 regulate SOCS1, intervening in the loop that, starting from FoxP3 and through SOCS1, leads to a sustained IL-2R signaling, necessary for Treg homeostasis (14).

In light of these observations, we extended the study of miR-155 to iNKT lymphocytes. We identified two targets of miR-155 in iNKT cells: Ets1 and Itk. Several studies have contributed to demonstrate that numerous molecules downstream the TCR are key for the development of iNKT cells, which strongly relies on the strength of TCR signaling in response to cognate interaction with CD1d. ITK is a member of the Tec family of non-receptor protein tyrosine kinases, which includes Rlk and Tec, and is important for effective signaling through the TCR. In the absence of ITK, iNKT cells are reduced in the thymus and periphery, and in both compartments they show a defective NK1.1 up-regulation, indicative of a failure to progress to Stage 3 (29). Defective ITK expression has been linked to an impaired induction of the transcription factor T-bet, the master regulator of iNKT cell maturation (30). Our data from Lck-miR-155 tg mice phenocopy those obtained in Itk KO mice, and show opposite expression levels of miR-155 and ITK in developing iNKT cells. Moreover, in both Itk KO and Lck-miR-155 tg mice, CD8 SP cells display reduced CD1d expression; this finding has probably no functional meaning, but constitutes an additional indication of the actual interaction between miR-155 and Itk in thymocytes. Similarly, Ets1 was also linked to the T cell maturation, via controlling the expression of TCRα gene (31).

We propose that miR-155 acts in itself as a modulator of TCR strength signaling by modulating the levels of Itk and Ets1 and consequently modulating iNTK cell maturation.

In conclusion, our study supports a novel regulatory role for miR-155 in the unique developmental program of iNKT cells and suggests that a dynamic regulation of miR-155 levels is critical for the physiology of these immunoregulatory cells.

Author Contributions

AB, PP, CC, and MC designed the study, AB, PP, ET, and AR performed research, SC generated the Lck-miR-155 tg mice. AB, PP, and ET wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of Health and AIRC (Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro) and by the National Institutes of Health (Grant 5R01CA124541, “Role of miR-155 in Leukemogenesis” to CC). AB and AR are supported by fellowships from FIRC (Fondazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro). We acknowledge Gabriella Abolafio and Andrea Vecchi for cell sorting, Ivano Arioli and Laura Botti for technical assistance.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00140

References

1. Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol (2007) 25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711

2. Borg NA, Wun KS, Kjer-Nielsen L, Wilce MC, Pellicci DG, Koh R, et al. CD1d-lipid-antigen recognition by the semi-invariant NKT T-cell receptor. Nature (2007) 448(7149):44–9. doi:10.1038/nature05907

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Liu Y, Teige A, Mondoc E, Ibrahim S, Holmdahl R, Issazadeh-Navikas S. Endogenous collagen peptide activation of CD1d-restricted NKT cells ameliorates tissue-specific inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest (2011) 121(1):249–64. doi:10.1172/JCI43964

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Issazadeh-Navikas S. NKT cell self-reactivity: evolutionary master key of immune homeostasis? J Mol Cell Biol (2012) 4(2):70–8. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjr035

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Bendelac A. Positive selection of mouse NK1+ T cells by CD1-expressing cortical thymocytes. J Exp Med (1995) 182(6):2091–6. doi:10.1084/jem.182.6.2091

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Schumann J, Pittoni P, Tonti E, Macdonald HR, Dellabona P, Casorati G. Targeted expression of human CD1d in transgenic mice reveals independent roles for thymocytes and thymic APCs in positive and negative selection of Valpha14i NKT cells. J Immunol (2005) 175(11):7303–10. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7303

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Benlagha K, Kyin T, Beavis A, Teyton L, Bendelac A. A thymic precursor to the NK T cell lineage. Science (2002) 296(5567):553–5. doi:10.1126/science.1069017

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Pellicci DG, Hammond KJ, Uldrich AP, Baxter AG, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. A natural killer T (NKT) cell developmental pathway involving a thymus-dependent NK1.1(-)CD4(+) CD1d-dependent precursor stage. J Exp Med (2002) 195(7):835–44. doi:10.1084/jem.20011544

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Godfrey DI, Stankovic S, Baxter AG. Raising the NKT cell family. Nat Immunol (2010) 11(3):197–206. doi:10.1038/ni.1841

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Napolitano A, Pittoni P, Beaudoin L, Lehuen A, Voehringer D, MacDonald HR, et al. Functional education of invariant NKT cells by dendritic cell tuning of SHP-1. J Immunol (2013) 190(7):3299–308. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1203466

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Bartel DP. microRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell (2009) 136(2):215–33. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Cobb BS, Hertweck A, Smith J, O’Connor E, Graf D, Cook T, et al. A role for Dicer in immune regulation. J Exp Med (2006) 203(11):2519–27. doi:10.1084/jem.20061692

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Fedeli M, Napolitano A, Wong MP, Marcais A, de Lalla C, Colucci F, et al. Dicer-dependent microRNA pathway controls invariant NKT cell development. J Immunol (2009) 183(4):2506–12. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0901361

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Lu LF, Thai TH, Calado DP, Chaudhry A, Kubo M, Tanaka K, et al. Foxp3-dependent microRNA155 confers competitive fitness to regulatory T cells by targeting SOCS1 protein. Immunity (2009) 30(1):80–91. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.010

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Piconese S, Pittoni P, Burocchi A, Gorzanelli A, Care A, Tripodo C, et al. A non-redundant role for OX40 in the competitive fitness of Treg in response to IL-2. Eur J Immunol (2010) 40(10):2902–13. doi:10.1002/eji.201040505

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Bezman NA, Chakraborty T, Bender T, Lanier LL. miR-150 regulates the development of NK and iNKT cells. J Exp Med (2011) 208(13):2717–31. doi:10.1084/jem.20111386

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Zheng Q, Zhou L, Mi QS. microRNA miR-150 is involved in Valpha14 invariant NKT cell development and function. J Immunol (2012) 188(5):2118–26. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1103342

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Costinean S, Zanesi N, Pekarsky Y, Tili E, Volinia S, Heerema N, et al. Pre-B cell proliferation and lymphoblastic leukemia/high-grade lymphoma in E(mu)-miR155 transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2006) 103(18):7024–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0602266103

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Ranganathan P, Heaphy CE, Costinean S, Stauffer N, Na C, Hamadani M, et al. Regulation of acute graft-versus-host disease by microRNA-155. Blood (2012) 119(20):4786–97. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-10-387522

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Kirigin FF, Lindstedt K, Sellars M, Ciofani M, Low SL, Jones L, et al. Dynamic microRNA gene transcription and processing during T cell development. J Immunol (2012) 188(7):3257–67. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1103175

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Zhu N, Zhang D, Chen S, Liu X, Lin L, Huang X, et al. Endothelial enriched microRNAs regulate angiotensin II-induced endothelial inflammation and migration. Atherosclerosis (2011) 215(2):286–93. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.12.024

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Das LM, Torres-Castillo MD, Gill T, Levine AD. TGF-beta conditions intestinal T cells to express increased levels of miR-155, associated with down-regulation of IL-2 and Itk mRNA. Mucosal Immunol (2013) 6(1):167–76. doi:10.1038/mi.2012.60

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Choi HJ, Geng Y, Cho H, Li S, Giri PK, Felio K, et al. Differential requirements for the Ets transcription factor Elf-1 in the development of NKT cells and NK cells. Blood (2011) 117(6):1880–7. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-09-309468

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Walunas TL, Wang B, Wang CR, Leiden JM. Cutting edge: the Ets1 transcription factor is required for the development of NK T cells in mice. J Immunol (2000) 164(6):2857–60. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.2857

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Felices M, Berg LJ. The Tec kinases Itk and Rlk regulate NKT cell maturation, cytokine production, and survival. J Immunol (2008) 180(5):3007–18. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3007

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Sandberg R, Neilson JR, Sarma A, Sharp PA, Burge CB. Proliferating cells express mRNAs with shortened 3’ untranslated regions and fewer microRNA target sites. Science (2008) 320(5883):1643–7. doi:10.1126/science.1155390

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Tili E, Michaille JJ, Croce CM. microRNAs play a central role in molecular dysfunctions linking inflammation with cancer. Immunol Rev (2013) 253(1):167–84. doi:10.1111/imr.12050

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Lind EF, Ohashi PS. Mir-155, a central modulator of T-cell responses. Eur J Immunol (2014) 44(1):11–5. doi:10.1002/eji.201343962

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

29. Qi Q, Kannan AK, August A. Tec family kinases: Itk signaling and the development of NKT alphabeta and gammadelta T cells. FEBS J (2011) 278(12):1970–9. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08074.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Matsuda JL, Zhang Q, Ndonye R, Richardson SK, Howell AR, Gapin L. T-bet concomitantly controls migration, survival, and effector functions during the development of Valpha14i NKT cells. Blood (2006) 107(7):2797–805. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-08-3103

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Dadi S, Le Noir S, Payet-Bornet D, Lhermitte L, Zacarias-Cabeza J, Bergeron J, et al. TLX homeodomain oncogenes mediate T cell maturation arrest in T-ALL via interaction with ETS1 and suppression of TCRalpha gene expression. Cancer Cell (2012) 21(4):563–76. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.013

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: iNKT cell, microRNA, transgenic, thymic development, gene expression regulation

Citation: Burocchi A, Pittoni P, Tili E, Rigoni A, Costinean S, Croce CM and Colombo MP (2015) Regulated expression of miR-155 is required for iNKT cell development. Front. Immunol. 6:140. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00140

Received: 17 December 2014; Accepted: 14 March 2015;

Published online: 30 March 2015.

Edited by:

Michael Loran Dustin, Harvard University, USAReviewed by:

Paula Kavathas, Yale University School of Medicine, USAQi-Jing Li, Duke University Medical Center, USA

Copyright: © 2015 Burocchi, Pittoni, Tili, Rigoni, Costinean, Croce and Colombo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mario Paolo Colombo, Molecular Immunology Unit, Department of Experimental Medicine, Fondazione IRCCS “Istituto Nazionale Tumori”, Via Amadeo 42, Milan I-20133, Italy e-mail:bWFyaW8uY29sb21ib0Bpc3RpdHV0b3R1bW9yaS5taS5pdA==

†Alessia Burocchi and Paola Pittoni have contributed equally to this work.

Alessia Burocchi

Alessia Burocchi Paola Pittoni1†

Paola Pittoni1† Esmerina Tili

Esmerina Tili Alice Rigoni

Alice Rigoni Stefan Costinean

Stefan Costinean Carlo Maria Croce

Carlo Maria Croce Mario Paolo Colombo

Mario Paolo Colombo