- 1Laboratory of Microbial Immunochemistry and Vaccines, Department of Immunochemistry, Ludwik Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy, Polish Academy of Sciences, Wroclaw, Poland

- 2Laboratory of Immunobiology of Infections, Institute of Medical Biology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Lodz, Poland

- 3Department of Biology of Bacteria, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, Institute of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Immunology, University of Lodz, Lodz, Poland

- 4Laboratory of General Microbiology, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, Institute of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Immunology, University of Lodz, Lodz, Poland

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, endotoxin), the main surface antigen and virulence factor of Gram-negative bacteria, is composed of lipid A, core oligosaccharide, and O-specific polysaccharide (O-PS) regions. Each LPS region is capable of complement activation. We have demonstrated that LPS of Hafnia alvei, an opportunistic human pathogen, reacts strongly with human and murine mannose-binding lectins (MBLs). Moreover, MBL–LPS interactions were detected for the majority of other Gram-negative species investigated. H. alvei was used as a model pathogen to investigate the biological consequences of these interactions. The core oligosaccharide region of H. alvei LPS was identified as the main target for human and murine MBL, especially l-glycero-d-manno-heptose (Hep) and N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (GlcNAc) residues within the outer core region. MBL-binding motifs of LPS are accessible to MBL on the surface of bacterial cells and LPS aggregates. Generally, the accessibility of outer core structures for interaction with MBL is highest during the lag phase of bacterial growth. The LPS core oligosaccharide–MBL interactions led to complement activation and also induced an anaphylactoid shock in mice. Unlike Klebsiella pneumoniae O3 LPS, robust lectin pathway activation of H. alvei LPS in vivo was mainly the result of outer core recognition by MBL; involvement of the O-PS is not necessary for anaphylactoid shock induction. Our results contribute to a better understanding of MBL–LPS interaction and may support development of therapeutic strategies against sepsis based on complement inhibition.

Introduction

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) is one of several pattern recognition molecules forming complexes with MBL-associated serine proteases (MASP) able to activate complement via the lectin pathway (LP). That process contributes to clearance of infection, but when excessive may be detrimental to the host (1).

Humans synthesize one type of MBL (hMBL), whereas mice (like the majority of mammals) synthesize two forms, MBL-A and -C, differing slightly in their specificity, serum concentration, activity, and local expression (2–5). Generally, hMBL recognizes carbohydrate patterns present on pathogens that are rich in d-mannose (d-Man), N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (d-GlcNAc), N-acetyl-d-mannosamine (d-ManNAc), or l-fucose (l-Fuc).

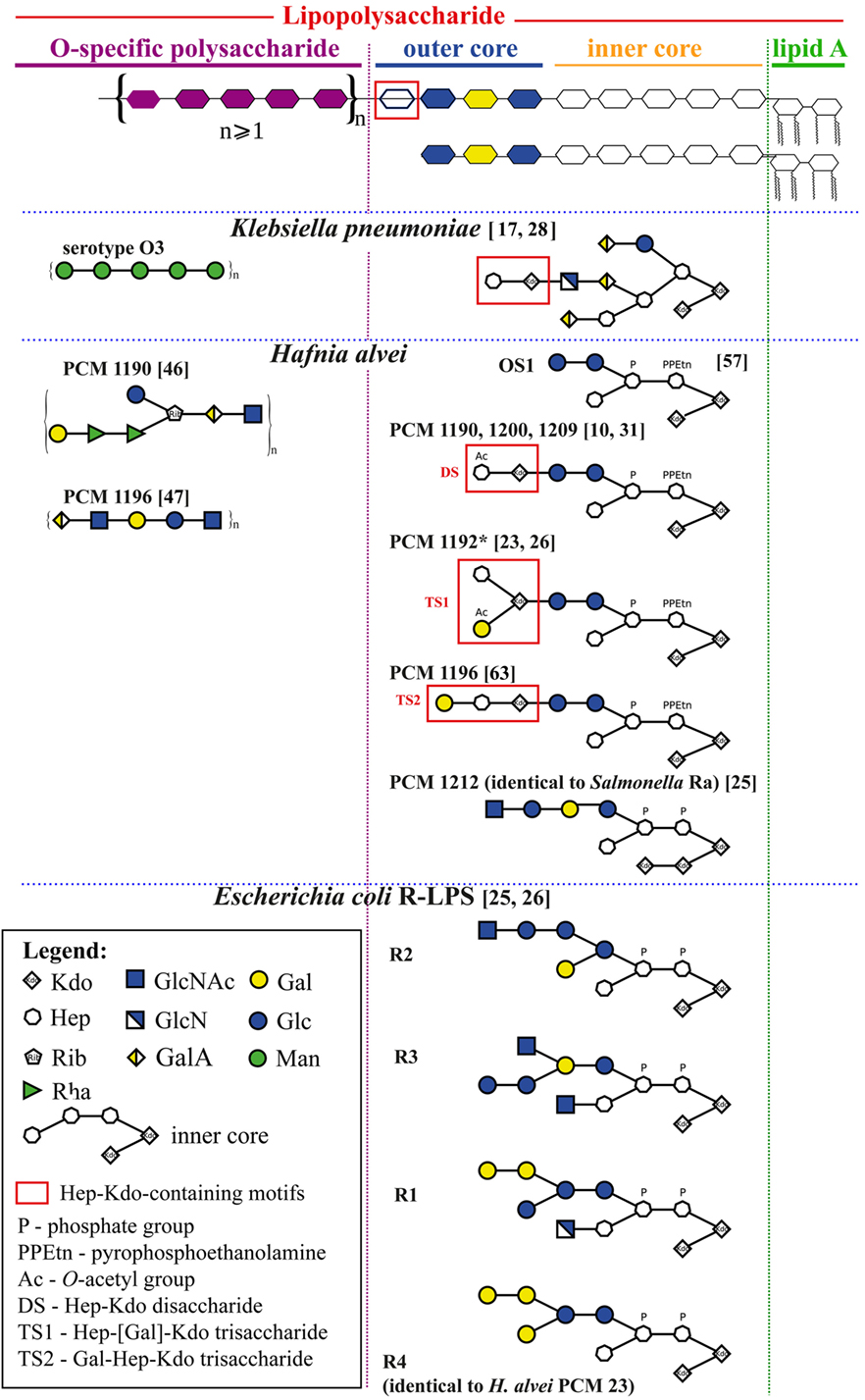

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, endotoxin), the main surface antigen of Gram-negative bacteria, may be a ligand of MBL. LPS is composed of lipid A linked to a core oligosaccharide (OS) consisting of inner and outer regions that is further substituted with O-specific polysaccharide (O-PS) comprising oligosaccharide repeating units. O-PS is a very variable region that determines O-serotype, whereas core OS and lipid A are characterized by moderate structural variability. Smooth bacterial strains synthesize highly heterogeneous LPS being the mixture of S-LPS built of all three regions and short R-LPS (devoid of the O-PS) (Figure 1). Rough bacteria synthesize exclusively R-LPS. Such factors as bacterial growth phase and temperature influence LPS heterogeneity (6).

Figure 1. Schematic structures of selected Klebsiella pneumoniae, Hafnia alvei, and E. coli, and Salmonella spp. lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) relevant for an interpretation of human mannose-binding lectin–LPS interactions. All structures are grouped according to the schematic diagram of an LPS molecule (upper panel) built of lipid A, core oligosaccharide (inner and outer), and O-specific polysaccharide consisting of a varying number of oligosaccharide repeating units. Information about linkages and isomers was hidden to simplify an interpretation of structures and may be found in details in references (numbers in brackets).

Each LPS region may induce synthesis of specific antibodies (Ab), able to activate the classical pathway (CP) of complement activation. However, in the absence of Ab, lipid A may activate CP via direct binding of C1, while core OS-LP (MBL-dependent) and O-PS may activate the alternative pathway (AP) and/or LP (involving MBL or ficolins) (7–10). Recently, MASP-1 (crucial for activating MASP-2 and therefore initiation of the LP cascade) was shown to participate in LPS-induced AP activation (11). Regarding core OS, l-glycero-d-manno-heptose (Hep) in the inner core region (characteristic for majority of LPS) and d-GlcNAc in the outer core region end (in Salmonella enterica serovar Minnesota) were reported as hMBL-binding motifs in R-LPS (12, 13). Although lipid A is considered the toxic principle of LPS, responsible for CD14–TLR-4–MD-2 complex-dependent immune cell response, the contribution of LPS polysaccharide-induced complement activation seems to be important for development of septic shock. Unlike lipid A-dependent endotoxic shock, polysaccharide-induced anaphylactoid reactions can be evoked in LPS-hyporesponsive mice (14, 15). Intravenous injection of certain S-LPS (but not isolated lipid A or R-type LPS) leads to rapid accumulation of platelets in the lungs and liver, followed by their degradation and release of serotonin, and death within 15–60 min, preceded by characteristic symptoms like convulsions and unconsciousness (16). Complement activated by LPS–MBL may be responsible for the degradation of platelets (16). LPS having mannose homopolymers (MHP) as O-PS (e.g., Klebsiella pneumoniae O3) (17) are potent inducers of anaphylaxis-like endotoxic shock in mice (16, 18). Some smooth bacteria (including Proteus vulgaris O25, S. enterica ser. Minnesota, and Abortusequi) have MBL-binding motifs within the core OS only and are capable of inducing a lethal early-phase shock (19, 20).

Hafnia alvei is an opportunistic human pathogen responsible for nosocomial mixed infections and sepsis (21). Most H. alvei LPS possesses smooth forms. So far, 40 O-serotypes (O-PS structures), and 4 types of core OS have been identified. H. alvei LPS is also an example of endotoxin having the E. coli-type structure of lipid A (22–24). A few strains of H. alvei synthesize LPS containing E. coli R4 [strains Polish Collection of Microorganisms (PCM) 23 or 1222] or Salmonella Ra (strain PCM 1212) core types (Figure 1) (25, 26). The OS1 hexasaccharide is the predominant core OS for this species, with Hep and Kdo residues in its inner core region like most Gram-negative bacteria (Table 1, footnote f) (24, 27).

Table 1. Structural characteristics of LPS and lectin blotting results of SDS-PAGE separated Hafnia alvei LPS with serum-derived hMBL.a

A peculiarity of H. alvei LPS is the presence of Hep-Kdo-containing motifs also in the outer core region (24) (Figure 1). Branched trisaccharide (TS1), l-α-d-Hepp-(1→4)-[α-d-Galp6OAc-(1→7)]-α-Kdop-(2→, was identified, for example, at the outer core region of H. alvei 32 and PCM 1192 LPS (OS1-TS1 core) (24, 31). Linear trisaccharide α-d-Galp-(1→2)-l-α-d-Hepp-(1→4)-α-Kdop-(2→ (TS2) is characteristic for H. alvei PCM 1196 (OS1-TS2 core) (32). The disaccharide (DS), l-α-d-Hepp3OAc-(1→4)-α-Kdop-(2→ was identified in H. alvei PCM 1200 and 1209 (OS1-DS type core) (29). The presence of Hep-Kdo-containing motifs in the outer core region makes H. alvei LPS similar to K. pneumoniae and P. vulgaris O25 LPS (28, 33). This similarity prompted us to examine the ability of H. alvei LPS to bind MBL, activate human and murine complement systems and induce anaphylactoid reactions in mice.

Here, we explicate the structural basis of interactions between MBL and core OS of a variety of H. alvei LPS. These interactions lead to the activation of complement via the LP. Moreover, complexes of H. alvei LPS with MBL were able to induce anaphylactoid shock in BALB/c mice. LPS from 10 different species of opportunistic pathogens were tested to identify other examples of such interactions. We suggest that common interactions between core OS of LPS and MBL triggering LP activation might influence the course of Gram-negative infections, including nosocomial infections and sepsis. Therefore, consideration of surface antigen structure should be helpful in understanding pathogenicity and may influence development of new therapeutic strategies in Gram-negative sepsis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

BALB/c mice (males, 7–8 weeks old) were purchased from the animal facility of the Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital, Research Institute, Lodz, Poland. The BALB/c mice were housed at the animal facility of the Ludwik Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy (Wroclaw, Poland) and in vivo experiments were approved by the Local Ethical Commission for Animal Experimentation (Wroclaw, Poland).

Bacteria

Hafnia alvei strains PCM 537, 1188, 1190, 1191, 1192, 1195, 1196, 1200, 1203, 1204, 1205, 1206, 1207, 1208, 1209, 1210, 1211, 1212, 1213, 1214, 1218, 1220, 1221, 1222, 1224, and E. coli O55 were obtained from the PCM at the Ludwik Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy (Wroclaw, Poland). Proteus spp. strains (P. mirabilis, P. vulgaris, P. penneri, P. myxofaciens, and P. genomospecies) came from the collection of the Laboratory of General Microbiology, University of Lodz (Poland). K. pneumoniae O3:K55− (strain 5505Δcps) was kindly provided by Prof. S. Kaluzewski (National Institute of Hygiene, Warsaw, Poland). H. alvei, E. coli, and K. pneumoniae were grown till exponential phase (8 h) in Davis medium as described (34), and Proteus spp. strains were grown in liquid nutrient broth containing 1% glucose (35). They were stored in a glycerol mixture at −75°C.

Sera

Sera obtained from BALB/c mice were used as a source of murine MBL and ficolins. Pooled normal human serum (NHS) was used as a source of hMBL and came from the collection of the Laboratory of Immunobiology of Infections, Institute of Medical Biology, Polish Academy of Sciences. Polyclonal rabbit sera anti-H. alvei core OS (OS1) conjugated with tetanus toxoid (OS1-TT) came from Laboratory of Microbial Immunochemistry and Vaccines (Ludwik Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy, Wroclaw, Poland). Polyclonal rabbit immunoglobulins specific for TS (Hep-[Gal]-Kdo) were isolated from antisera using an adsorption on bacterial mass as previously described (24). DS-specific Ab were isolated by two-step affinity chromatography of anti-H. alvei 1209 serum (immunization with killed bacteria, DS-positive strain) on: (i) H. alvei 1209 core OS1-Sepharose 4B gel and (ii) H. alvei 1209 O-PS-Sepharose 4B gel. Both resins were prepared as previously described (10, 36, 37). Eluates containing anti-DS Ab were collected in sterile vials and stored at −20°C.

Preparation of LPS

Lipopolysaccharide were extracted from bacterial cells by the hot phenol/water method (38) and purified by ultracentrifugation as previously described (34, 35). Proteus spp. LPS were extracted from dried bacterial cells, as previously described (39), by the phenol–water procedure according to the method of Westphal and Jann (38) and purified with aqueous 50% trichloroacetic acid. For analyses of growth phase dependence of hMBL–bacteria interactions (SDS-PAGE and lectin blotting), LPS was isolated from bacteria by Tri-Reagent method (40). LPS of H. alvei strains 1, 2, 17, 23, 31, 32, 37, 38, 39, 114/60, 481L, 600, 744, 981, Edwardsiella anguillimortifera, Citrobacter (kindly provided by Prof. E. Katzenellenbogen), and E. coli came from the collection of the Laboratory of Microbial Immunochemistry and Vaccines (Ludwik Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy, Wroclaw, Poland).

O-PSs, Core Oligosaccharides, and Lipid A Isolation

Polysaccharides, oligosaccharides, and lipids A were isolated by mild acidic hydrolysis of H. alvei PCM 1190, 1192, and 1200 LPS at 100°C for 45 min. Poly- and oligosaccharides were fractionated and purified as previously described using Bio-Gel P-10 (10). The Hep-Kdo-containing fraction was isolated from the heterogeneous core OS fraction and analyzed by the use of liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS) on SeQuant®ZIC®-HILIC column as previously described (41). Fractions 3 and 4 were pooled and used for surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis. Lipid A was isolated as a water-insoluble fraction of the LPS hydrolyzate. Prior to lectin blotting, lipids A were purified by extraction with 2:1:3 chloroform/methanol/water mixture (v/v/v) to remove membrane phospholipids and remains of LPS. Both water phase (w) and chloroform (ch) phase lipids A were collected (23).

SDS-PAGE

The LPS and lipids A were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Briefly, 4.5 and 15.4% polyacrylamide-bisacrylamide gels were used as the stacking and resolving gels, respectively. Glycolipids (3 µg) were mixed with sample buffer (65 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 35% glycerol, 0.6 M DTT, ~0.1% bromophenol blue) in ratio 1:1 (v/v). LPS/lipid A bands were visualized by the silver staining method (42).

Lectin Blotting

SDS-PAGE-separated LPS were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, USA). Membranes were blocked with SuperBlock® Blocking Buffer (Thermo Scientific, USA) for 2 h, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C, with 25-fold diluted human or murine serum as previously described (10). Bound proteins were detected by immunostaining with different primary Ab: (i) monoclonal mouse anti-hMBL Ab (clone HYB 131-01, BioPorto, Denmark), (ii) monoclonal rat anti-MBL-A (clone 2B4) and (iii) anti-MBL-C Ab (clone 16A8) (both from Hycult Biotech, The Netherlands), (iv) rabbit anti-ficolin-A kindly provided by Dr. Yuichi Endo (Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima, Japan), and (v) reactions were detected with HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse, anti-rat secondary IgG Ab (Dako, Denmark) or anti-rabbit IgG secondary Ab, and visualized with Immun-Star HRP Chemiluminescent Substrate Kit (Bio-Rad, USA) and G:Box chemiluminescent imaging system (Syngene, UK). Nonspecific interactions of secondary Ab were excluded by controls without the primary Ab or the serum as a source of hMBL.

ELISA for Lectin Binding

Interactions of hMBL, MBL-A, MBL-C, and murine ficolins A and B with H. alvei LPS were tested as previously described (10). Briefly, NUNC Maxisorp U96 plates were coated with 2 µg of LPS/well. After blocking with 0.1% BSA in TBS-Ca2+ buffer (10 mM Tris, 120 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4), NHS or murine serum (prediluted in 0.1% BSA/20 mM Tris, 1 M NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) was added. After overnight incubation at 4°C, the bound proteins were detected by using specific primary antibodies (mentioned in the lectin blotting procedure) and HPR-conjugated anti-mouse, anti-rat, or anti-rabbit corresponding anti-IgG antibodies (Dako, Denmark). As substrate for peroxidase, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenz-thiazoline-6-sulfonic)acid (ABTS) (Sigma, USA) was employed. Absorbance values were measured at 405 nm using Benchmark Plus microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad).

Determination of hMBL–MASP-2 and MBL–MASP-1 Complex Activity

Activity of lectin(s)-MASP-2 complexes was determined as previously described (43) with modification (44). LPS from various bacteria were used for coating of microtiter plates (Maxisorp U96, Nunc). The products of C4 activation were detected with rabbit anti-hC4c and HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit Ig (Dako). To test MBL-MASP-1 complex activity, VPR-AMC (Val-Pro-Arg-aminomethylcoumarin) peptide (Bachem, Switzerland), as the substrate for MASP-1 was used as previously described (45) and the fluorescence was read using a Varioskan Flash reader (Thermo Scientific, USA).

Flow Cytometry Analysis of Binding of hMBL to Formaldehyde-Inactivated Bacteria

Flow cytometry analysis was performed as previously described (10). Depending on experiment, bacteria were cultured and harvested at lag phase (3 h), log phase (6 h), or stationary phase (24 h) of growth. The growth phase of culture was determined on the basis of optical density measurement at 600 nm and the appropriate growth curve. Immediately before each experiment, bacterial cells were centrifuged, washed with PBS, and suspended in 10-fold diluted NHS (pool), used as a source of hMBL. Monoclonal anti-hMBL Ab (clone HYB 131-01) and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-mouse IgG Ab (Dako) were used as detection system. The analysis of the FITC-labeled bacteria was performed using a Cytomics FC 500 MPL Beckman-Coulter (USA) flow cytometer. Bacteria were detected using log-forward and log-side scatter dot plot. Gating region was set to exclude debris and larger aggregates of bacteria. A total of 10,000 events were acquired.

Induction of Anaphylaxis-Like Endotoxic Shock in muramyldipeptide (MDP)-Primed Mice

The BALB/c mice were treated i.p. with 100 µg of MDP in PBS (20), and after 4 h, animals received i.v. 100 µg of LPS. K. pneumoniae O3 and E. coli O55 LPS were used as a positive and negative control, respectively. Incidence, severity, and scoring of the anaphylaxis-like shock were recorded within 30 min: 0, no signs of shock; 1, staggering; 2, crawling and prostration; 3, prostration and weak convulsions; 4, prostration and strong convulsions (16). Subsequent mortality was recorded within 1 h and after 24 h after LPS injection.

Surface Plasmon Resonance

Surface plasmon resonance studies were assessed with a Biacore T200 system (GE Healthcare Bio-Science AB, Sweden). Carrier free recombinant hMBL (R&D Systems, USA) was immobilized in 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.0 on the CM5 series S sensor chip (GE Healthcare Bio-Science AB) at a flow rate 5 µl/min, to the level of 16,000 RU using the amine coupling chemistry. A flow cell with immobilized 240 RU of ethanolamine was used as a reference surface. HBS-P buffer (GE Healthcare Bio-Science AB) supplemented with Ca2+, Mg2+ ions (5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM CaCl2) was used as a running buffer. H. alvei O-PS (PCM 1190, 1196, 1200, and 1209) and core hexasaccharides from H. alvei PCM 1200 LPS at various concentrations were injected at a flow rate 30 µl/min. 0.5% SDS injected for 30 s was used as a regenerator in all SPR experiments.

Results

H. alvei LPS Core Oligosaccharide Is a Common MBL Target

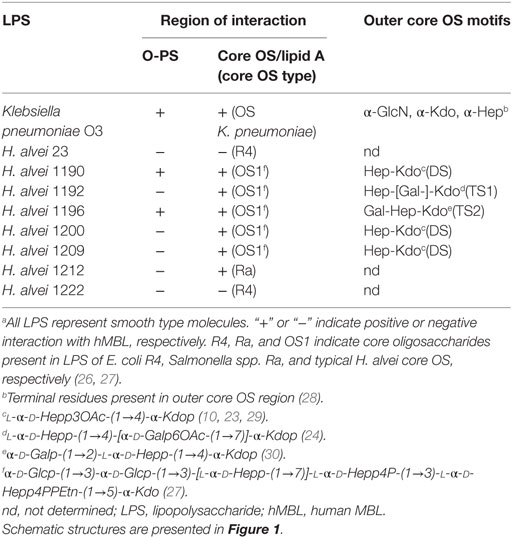

Screening for the presence of structural motifs recognized by hMBL was performed by lectin blotting for LPS isolated from 39 different O-serotypes of H. alvei (Figure 2). LPS isolated from smooth strains gave a characteristic ladder-like multi-band pattern after SDS-PAGE reflecting natural heterogeneity of LPS on the cell wall surface and facilitating core OS accessibility (Figure 2A). The fast-migrating fractions originate from lipid A substituted with core OS, whereas the slow-migrating fractions show the length distribution of the polymer built up of lipid A-core OS substituted with varying numbers of O-PS repeating units. LPS isolated from K. pneumoniae O3 strain 5505 (MHP as O-PS) was used as a positive control, where interactions were observed both in the core OS/lipid A and O-PS regions. hMBL recognized 34 out of 39 H. alvei LPS. Generally, reactivity was related to the fast-migrating fractions of the core OS-lipid A region. No interactions were observed for H. alvei 23, PCM 744, 1204, 1212, and 1222 LPS (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Silver stained SDS-PAGE (A) and lectin blotting analysis (B) of the interaction of human MBL (hMBL) with Hafnia alvei lipopolysaccharides (LPSs). Normal human serum (pool) was used as a source of hMBL. Lanes are depicted with the strain number in Polish Collection of Microorganisms. The number 5505 represents Klebsiella pneumoniae O3:K55− LPS used as a positive control.

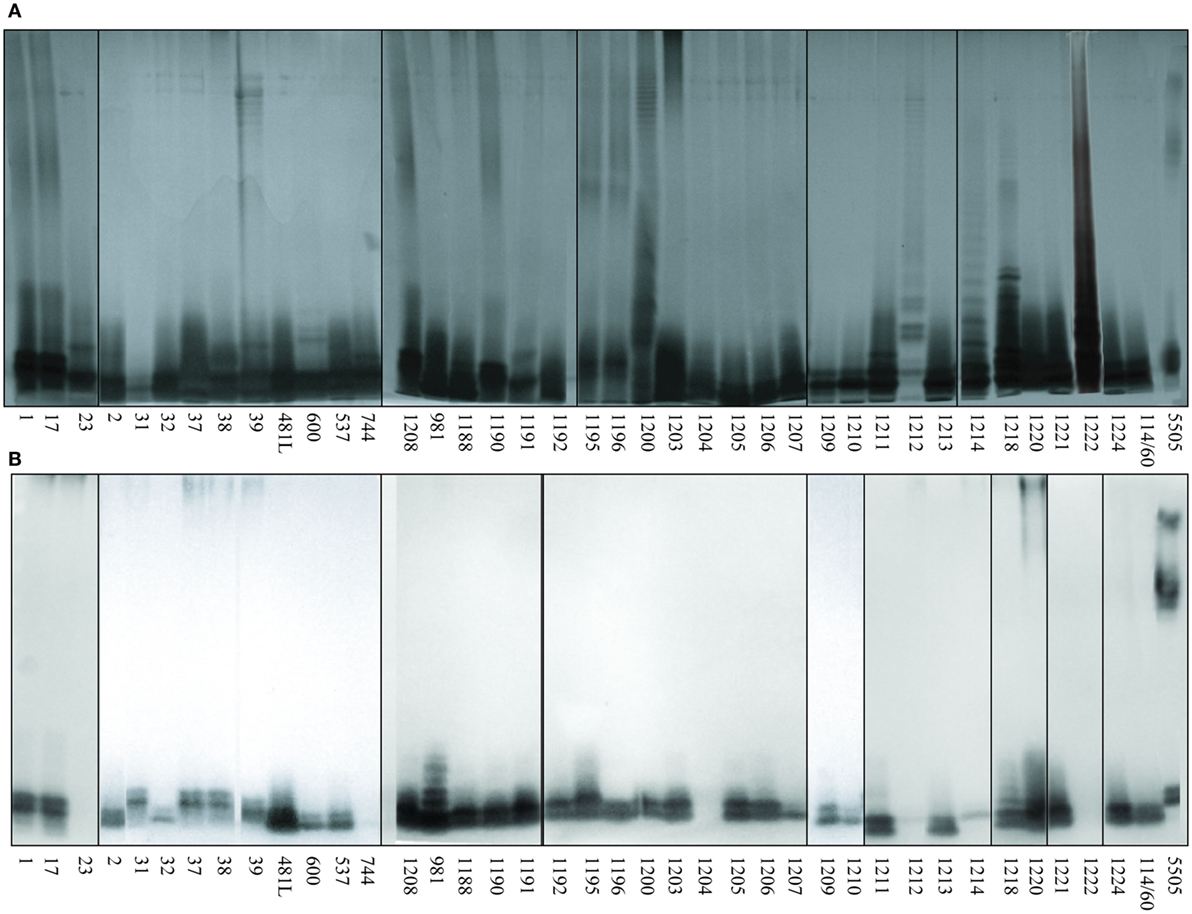

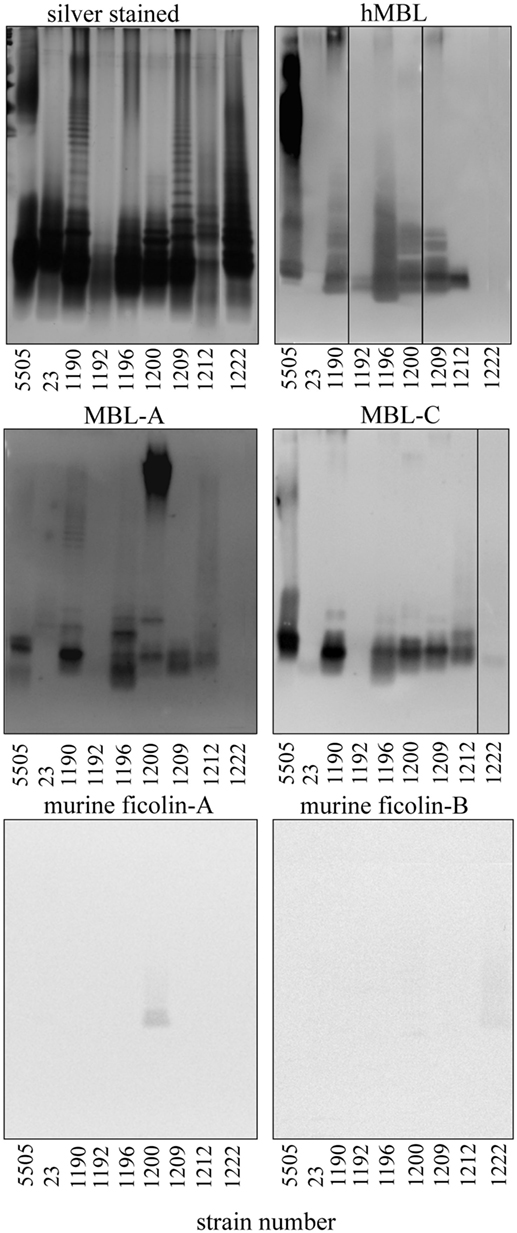

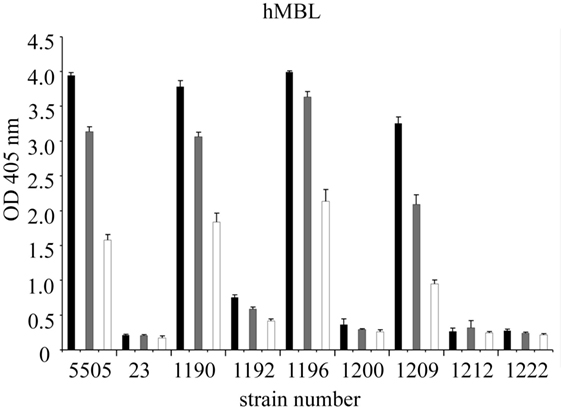

Nine representative LPS, chosen on the basis of well-characterized structure (Figure 1) and different hMBL-binding patterns (Figure 2B; Table 1), were selected for further experiments to explore human and murine MBL specificity (Figure 3). For H. alvei PCM 1192, 1200, 1209, and 1212, hMBL bound within the core OS region only. For H. alvei PCM 1190 and 1196, hMBL bound within both the core OS and O-PS regions. For H. alvei 23 and PCM 1222, no binding was observed. These LPS–hMBL interactions were confirmed by ELISA (Figure 4). Eight H. alvei LPS (and K. pneumoniae O3 LPS as positive control) were used as solid-phase antigens. The strongest reactions of serum hMBL were observed for LPS K. pneumoniae O3 and H. alvei PCM 1190, 1196, and 1209 LPS. In contrast to the lectin blotting, no reaction with H. alvei PCM 1200 LPS was observed, what might be explained by competition between strong binding of O-PS-reactive ficolin-3 (10) and moderate binding of core OS-reactive hMBL. In addition, long O-PS chains of LPS 1200 might also hinder hMBL access to core OS.

Figure 3. Silver stained SDS-PAGE of representative Hafnia alvei lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) and lectin blotting of their interactions with human MBL (hMBL) and murine mannose-binding lectin (MBL)-A, MBL-C, ficolin-A, and ficolin-B. Normal human serum and BALB/c mice sera were used as a source of hMBL or murine MBL-A, MBL-C, ficolin A, and B, respectively. Lanes are depicted with the strain number in Polish Collection of Microorganisms. Strain 5505 represents Klebsiella pneumoniae O3:K55− LPS used as a positive control.

Figure 4. Recognition of selected Hafnia alvei lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) by human MBL. Microtiter plates were coated with LPS, incubated with NHS to measure interactions with hMBL. Black, gray, and white bars represent 200-, 400-, and 800-fold dilutions, respectively. Data represent the mean values of four replicates and are marked by PCM strain number. Strain 5505 represents Klebsiella pneumoniae O3:K55− LPS used as a positive control. Abbreviations: OD, optical density measured at λ = 405 nm; hMBL, human MBL; NHS, normal human serum; PCM, Polish Collection of Microorganisms.

Since murine model was chosen for further studies to test in vivo activity of LPS on complement-mediated anaphylaxis-like endotoxic shock, the reactivity of LPS with murine MBL-A and MBL-C (as well as with ficolin A and ficolin B) was analyzed by lectin blotting (Figure 3). Murine MBL-C showed binding pattern very similar to hMBL within the core OS region. Strong reactions with H. alvei PCM 1190, 1196, 1200, 1209, 1212, and K. pneumoniae O3 LPS and negligible reactions with LPS 23, PCM 1192 and 1222 were noted. In addition, interactions with high molecular weight fractions (O-PS region) were easily visible for H. alvei 1190 and K. pneumoniae O3 LPS. For MBL-A, no reactivity was observed for PCM 1192 and 1222 and very weak reactivity for 23 (within O-PS). Binding of this lectin to LPS K. pneumoniae O3 and PCM 1209 strains was attributed to core OS only. Reactivity within both core OS and O-PS region were observed for H. alvei PCM 1190, 1196, 1212, and 1200. Especially strong recognition of PCM 1200 LPS was unique for MBL-A, whereas MBL-C (similarly to hMBL) were devoid of such activity. Moreover, only traces of signal related to O-PS region were observed for interactions of ficolin A with PCM 1200 and ficolin B with PCM 1222 (Figure 3). Interactions of MBL-A and MBL-C with H. alvei lipid A was excluded by lectin blotting (Figure 5B).

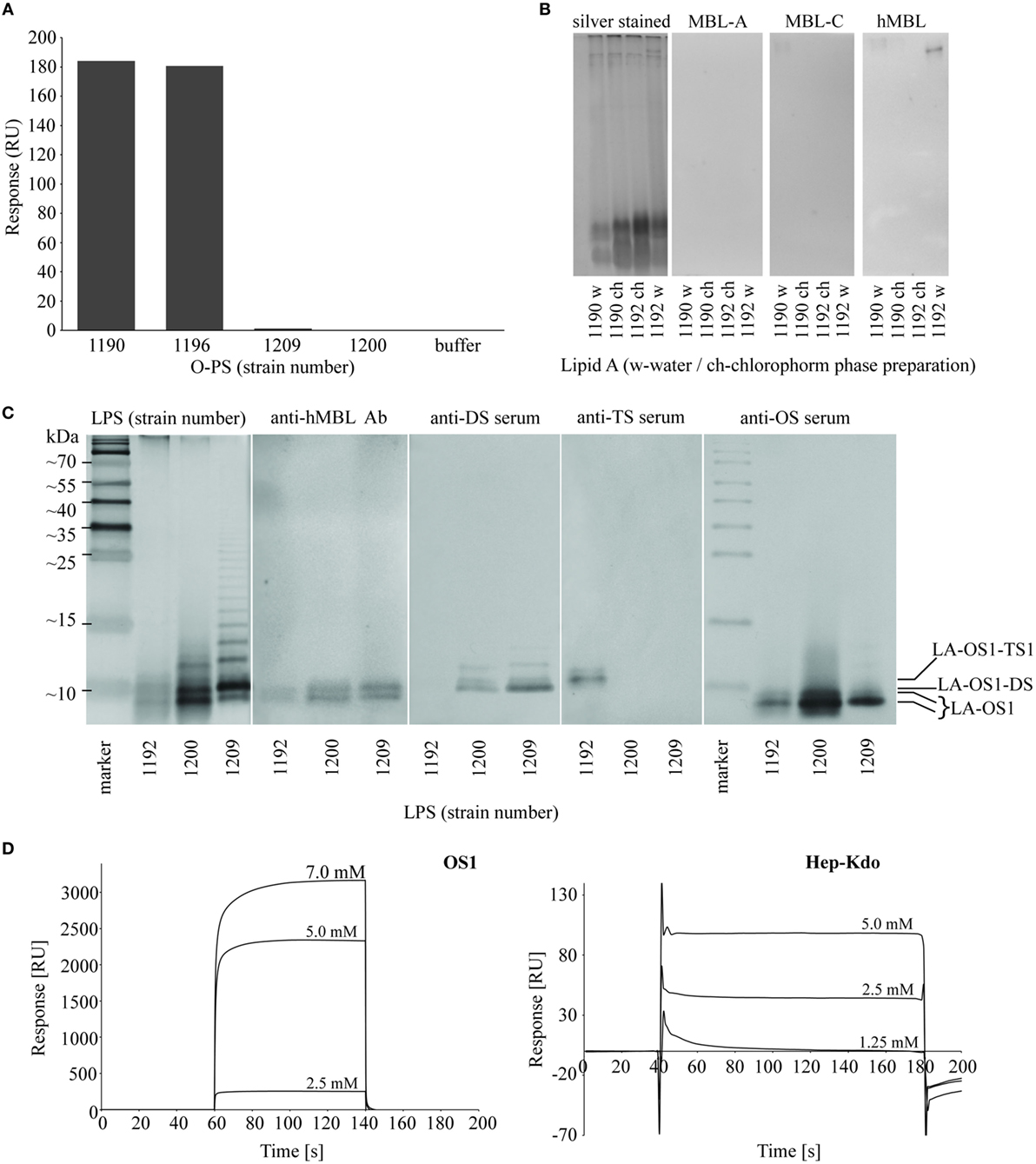

Figure 5. Identification of hMBL-binding regions in Hafnia alvei lipopolysaccharides (LPSs). (A) Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis of interactions between recombinant hMBL and O-specific polysaccharides (O-PSs) of H. alvei PCM 1190, 1196, 1200, and 1209 LPS. The bars represent binding response of immobilized recombinant hMBL (immobilization level: 16,000 RU) to O-PS (0.5 mg/ml) in running buffer HBS-P supplemented with MgCl2 and CaCl2. (B) Silver stained SDS-PAGE and lectin blotting analysis of the interaction between H. alvei lipids A [water phase (w) and chloroform phase (ch) preparations] and serum-derived murine MBL-A, MBL-C, and hMBL. Lanes are depicted with the strain PCM number. (C) Silver stained SDS-PAGE and lectin blotting analyses of the interactions between LPS of H. alvei PCM 1192 (TS1-positive), 1200 (DS-positive), 1209 (DS-positive) and serum-derived hMBL, DS-specific rabbit serum, TS1-specific rabbit serum, and OS1-specific rabbit serum. M—molecular weight markers. Marked bands corresponded to different forms of R-LPS: LA-OS1, LA-OS1-DS, LA-OS1-TS1, where LA stands for lipid A. (D) SPR sensograms for interactions of recombinant hMBL and OS1 and Hep-Kdo-containing OS isolated from H. alvei 1200 LPS. Sensor chip: CM5; Abbreviations: RU, response units; hMBL, human MBL; PCM, Polish Collection of Microorganisms; MBL, mannose-binding lectin.

Hep-Kdo Motifs in H. alvei LPS Inner and Outer Core Are Recognized by MBL

From lectin blotting (Figures 2 and 3), it was suggested that most H. alvei LPS were bound by hMBL via the core OS/lipid A region. SPR analyses confirmed interactions of hMBL with O-PS regions of PCM 1190 (46) and 1196 (47) and excluded O-PS of PCM 1209 and 1200 LPS as targets for the lectin (Figure 5A). Data from lectin blotting with the use of purified lipid A fractions of H. alvei PCM 1190 and 1192 confirmed the lack of hMBL reactivity with that part of LPS (Figure 5B).

Next, we identified the core OS regions involved. Immunostaining with the use of OS1, DS- and TS1-specific Ab revealed four bands of low molecular weight fractions of migrating LPS (Figure 5C) attributed to lipid A-OS1 (two bands), lipid A-OS1-TS1, and lipid A-OS1-DS molecules. Two bands marked by lipid A-OS1 reflected OS1 heterogeneity related to ethanolamine, phosphate groups, and glycine substituents and are common for all three studied LPS (PCM 1192, 1200, and 1209). The band assigned as lipid A-OS1-DS was present in DS-expressing LPS of H. alvei PCM 1200 and 1209, while the lipid A-OS1-TS1 band in LPS of H. alvei PCM 1192 LPS.

The ability of recombinant hMBL to bind different core OS fractions of H. alvei LPS was further investigated by SPR on Biacore T200 (Figure 5D). Core OS isolated from PCM 1200 LPS were used as analytes. Both isolated OS1 and low molecular weight fraction of Hep-Kdo interacted with immobilized recombinant hMBL in a concentration-dependent manner, with higher affinity observed for OS1. It was also confirmed by ELISA inhibition assay with the use of both analytes (data not shown).

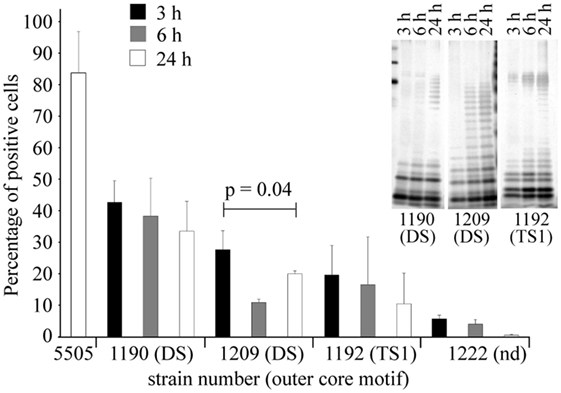

Bacterial Growth Phase Determines the Accessibility of LPS Core Region for MBL

Binding of hMBL to LPS on bacterial surface was further investigated by flow cytometry. Since bacterial growth phase may be associated with changes in LPS expression, accessibility of core OS regions for hMBL was examined using microbial cells collected at lag (3 h), log (6 h), and stationary phase (24 h) (Figure 6). Four strains were chosen for this study: (i) H. alvei PCM 1190 recognized by hMBL within DS-carrying core OS and O-PS regions, (ii) H. alvei PCM 1192 and 1209 with hMBL targets located in low molecular weight fraction of LPS (core OS1 decorated with TS1 or DS, respectively), and (iii) H. alvei PCM 1222 expressing LPS not recognized by hMBL. K. pneumoniae O3 grown to the stationary phase was used as a positive control. The percentage of hMBL-labeled cells was confronted with R-LPS and S-LPS distribution examined by SDS-PAGE analysis of LPS extracted from cells at lag, log, and stationary phases (Figure 6, inset).

Figure 6. Growth phase-dependence of hMBL–Hafnia alvei interactions observed in FACS analyses. Binding of hMBL to inactivated smooth H. alvei PCM 1190, 1192, and 1209 bacterial cells at the lag (black bars), exponential (gray bars), and the stationary phases (white bars) of growth. Silver stained SDS-PAGE (inset) of LPS 1190, 1209, and 1192 isolated from bacterial mass collected at lag, log, and stationary phases. Data represent the mean values ± SD from three independent experiments. DS and TS1 stand for the disaccharide and trisaccharide outer core motif in LPS of selected H. alvei strains. Abbreviations: Nd, not determined; hMBL, human MBL; PCM, Polish Collection of Microorganisms; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

For all hMBL-reacting strains (PCM 1190, 1192, and 1209), the highest values of labeled cells were recorded for lag phase, where R-LPS represented the prevailing LPS population. The low content of O-PS chains facilitated access of hMBL to outer core regions of R-LPS (OS1 and DS). For strains PCM 1190 and 1192, the proportions of labeled cells were inversely associated with the expression of the S-LPS population. The highest values, at each growth phase, were recorded for the PCM 1190 strain. This was expected since its LPS has MBL-binding motifs not only in the core but also in O-PS region. PCM 1192 and 1209 LPS were recognized by hMBL within the core OS region only, whereby the most efficient binding was observed for bacteria at the lag phase (10.4 and 27.7% positive cells, respectively). In contrast to other strains, PCM 1209 bacteria showed the lowest accessibility for hMBL at log but not stationary phase. That might be explained by a higher content of R-LPS forms with accessible OS1 and DS motifs at stationary phase contrary to log phase (as evidenced by SDS-PAGE). Performed experiments demonstrated that observed relationships clearly resulted from LPS structure, i.e., the length of O-PS chains that hindered structural motifs recognized by hMBL (OS1 and DS).

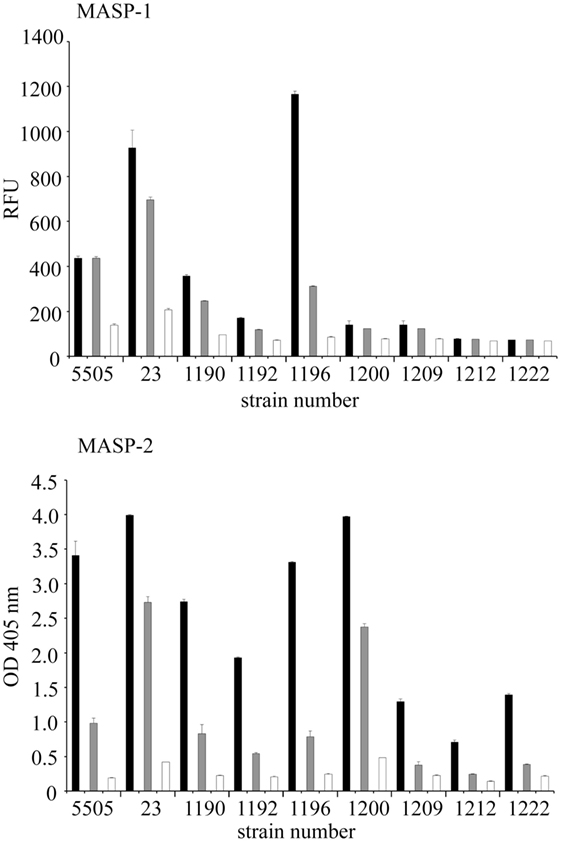

Interaction of hMBL With H. alvei LPS Leads to Complement Activation

The ability of selected LPS to initiate the complement cascade via the LP was tested by investigating activation of MASP-1 (cleavage of synthetic substrate, VPR-AMC) and MASP-2 (cleavage of C4) dependent on LPS recognition by LP molecules, especially hMBL. MBL–MASP-1 concentration-dependent activation was triggered by H. alvei 23, PCM 1190, 1192, 1196, 1200, 1209 LPS, as well as K. pneumoniae O3 (control) (Figure 7). The deposition of C4 activation products was additionally noted for PCM 1212 and 1222 LPS. It is worth mentioning that procedure employed does not exclude activation of LP by complexes of ficolin-3 with MASP (as described previously for 23 and PCM 1200 LPS) (10) or other than MBL collectins. Contribution of ficolin-1 and -2 was excluded (10). The influence of CP was excluded by high ionic strength of the buffer that inhibits the binding of C1q to immune complexes and disrupts the C1 complex, whereas MBL complexes integrity is maintained (48). The variations in reactivity profiles (Figures 4 and 7) may reflect differences in serum dilution used and sensitivity of assays.

Figure 7. Activation of the human lectin pathway of complement by Hafnia alvei LPS. (Top) Human LPS-MASP-1 activity (ability to cleave a VPR-AMC peptide). Black, gray, and white bars represent 5-, 20-, and 40-fold dilutions, respectively. (Bottom) Human LPS–MASP-1/2 complex-dependent C4c deposition. Black, gray, and white bars represent 50-, 200-, and 800-fold dilution, respectively. Each dilution series is described by the strain number on the X-axis. Pattern recognition molecule states for MBL or other complement-activating collectin/ficolin present in serum. Data represent the mean values of four replicates. LPS were used as solid phase. Abbreviations: RFU, relative fluorescence units; OD, optical density measured at λ = 405 nm; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MBL, mannose-binding lectin; MASP, MBL-associated serine proteases.

Interaction of MBL With H. alvei LPS Core Oligosaccharide Induces Anaphylactoid Shock

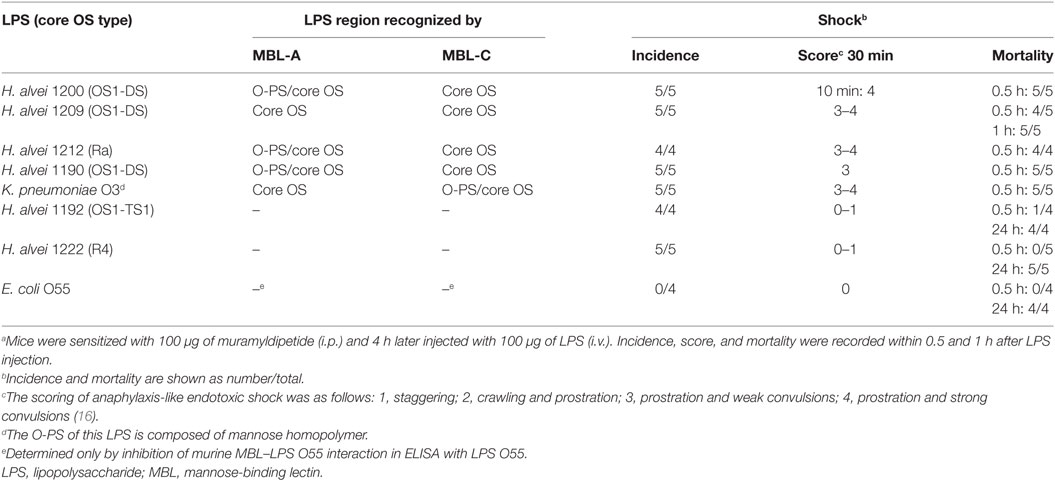

The biological consequences of in vivo MBL interaction with H. alvei PCM 1190, 1192, 1200, 1209, and 1212 LPS were tested by ability to induce an anaphylactoid reaction in mice. K. pneumoniae O3 and E. coli O55 as well as H. alvei PCM 1222 LPS were used as positive and negative controls, respectively (14).

Intravenous injection of H. alvei PCM 1190, 1200, 1209, or 1212 LPS-induced rapid shock (within 30 min, score 3–4) leading to death of MDP-sensitized BALB/c mice (Table 2). The distinctive effect was observed for LPS of H. alvei PCM 1200 that was strongly recognized by MBL-A within the O-PS region and moderately within the OS1-DS core region (Figure 3). The reaction, comparable to that provoked by K. pneumoniae O3 LPS, was also induced by H. alvei PCM 1190 (OS1-DS core type) and 1212 (Salmonella Ra core type) moderately bound by MBL-A and MBL-C within the O-PS and core OS regions. H. alvei PCM 1209 LPS (OS1-DS core type) that was reactive for murine MBL-A and MBL-C within the core OS region only (Figure 3), still had a powerful ability to induce an anaphylactoid shock similar to K. pneumoniae O3. By contrast, mice treated with H. alvei PCM 1192 (OS1-TS1 core type) or 1222 (E. coli R4 core type) LPS developed mild or no characteristic symptoms within the first hour and died in the late phase of endotoxic shock (lipid A-dependent) (Table 2), similar to animals injected with E. coli O55 LPS (negative control).

Table 2. Ability of LPS from smooth strains of Hafnia alvei, E. coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae to induce anaphylactoid shock and death in BALB/c mice.a

LPS Core Oligosaccharide Is a Common MBL Target in Many Gram-Negative Bacteria

Screening for LPS from a variety of opportunistic pathogens (Table S1 in Supplementary Material), recognized by serum hMBL was performed with the use of lectin blotting. False positive reactions of primary and secondary detecting Ab were excluded. We found interactions between hMBL and LPS core regions to be very common: 13 of 15 K. pneumoniae, 11/22 P. vulgaris, 10/33 P. mirabilis, 7/15 P. penneri, 1/1 P. myxofaciens, 5/10 E. coli (including R-LPS containing R2 and R3 core types), 1/5 Citrobacter spp., and all of 4/4 Edwardsiella anguillimortifera LPS gave positive results.

Discussion

Lipopolysaccharide is a major pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) and virulence factor of Gram-negative bacteria, responsible for development of sepsis and septic shock. Whereas the role of lipid A in those life-threatening events is well-documented (49), the influence of the polysaccharide region is poorly characterized. It is known that the carbohydrate moiety influences endotoxin clearance and biological activity of lipid A (50, 51). Recognition of LPS polysaccharide by a variety of pattern recognition molecules may lead to complement activation via CP, AP, and/or LP, all involved in sepsis development (52).

The core OS-lipid A region is a target for such plasma proteins as LPS-binding protein, BPI (bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein), CAP18 (cationic antimicrobial protein), and lysozyme. Consequently, bactericidal and inflammatory processes are induced by the host immune system. Due to the high structural heterogeneity of O-PS, the number of innate immunity factors interacting with that region is much lower. One example is ficolin-3, recognizing H. alvei PCM 1200 O-PS resulting in LP activation (10). Ficolin-3 was also demonstrated to enhance agglutination, phagocytosis, and killing of H. alvei PCM 1200 bacteria (53). Another example is pulmonary surfactant collectin SP-D binding mannose-rich O-PS of K. pneumoniae O3 and O5 (54).

This study provided well-documented evidence that core OS is the main target for human and murine MBL. Depending on the assay, the binding of recombinant (SPR) or NHS or murine serum MBL (lectin blotting, ELISA, flow cytometry) was detected in presented studies. Thus, it is worth noting that the oligomer distribution may vary for recombinant and NHS-derived MBL according to purification procedure (55), what may influences binding affinity between MBL and target ligand. Notwithstanding similar oligomer distribution patterns were reported for both forms (55, 56), including trimeric and tetrameric forms. Even though proposed oligomerization models indicated a polypeptide dimer as the basic unit in this process for MBL (57), higher oligomeric states are usually detected in rMBL and NHS-derived MBL preparations that ensure complement activation (56).

Performing screening analysis, we have shown that interactions of serum hMBL with different core OS regions were prevalent among LPS isolated from numerous opportunistic pathogens, such as H. alvei, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Proteus spp., Citrobacter spp., and E. anguillimortifera representing different O-serotypes (O-PS structure) (Table S1 in Supplementary Material). Among 145 LPS tested, as much as approximately 57% were recognized by hMBL within fast-migrating fractions (corresponding to R-LPS built up of lipid A-core OS), whereas the reaction with slow-migrating fractions (S-LPS containing O-PS) was found in approximately 10% only. Accordingly, hMBL interacted with 34 (approximately 87%) out of 39 H. alvei LPS within the core OS region of LPS. Moreover, we also showed that highly purified H. alvei hexaacylated lipid A is recognized neither by human nor murine MBL. However, such interactions were previously suggested by Ono et al. (58) and Shiratsuchi et al. (59) for commercially available E. coli lipid A. This discrepancy may result from impurities of bacterial origin in the commercial preparations or the presence of MBL-binding motifs other than in the lipid A region of LPS (residuals of complete LPS after lipid A isolation by LPS hydrolysis).

Clinical isolates of Gram-negative bacteria are commonly of smooth type and therefore synthesize a highly heterogeneous pool of LPS, consisting of long-chain S-LPS, shorter S-LPS, and R-LPS unsubstituted by O-PS. We found that H. alvei PCM 1209 core OS within R-LPS forms exposed on the bacterial surface is accessible for hMBL (Figure 6). SPR analysis (Figure 5A) clearly demonstrated that PCM 1209 O-PS is not the MBL target. The core OS accessibility may depend on natural LPS heterogeneity (coexistence of R-LPS and S-LPS in smooth strains), and is hindered by core OS substitution with O-PS. It may be influenced by growth phase or environmental conditions. Generally, expression of R-LPS containing hMBL-binding motifs decreased with the culture progression (from lag to stationary phase) (Figure 6). Moreover, the immune response against O-PS may cause selective pressure on bacteria to lose the ability to express it (phase variation) (60, 61).

The LPS core OS region is relatively conservative and usually composed of an inner core and an outer core built up of Kdo and Hep residues and hexoses and hexosamines, respectively. For example, among Salmonella spp. strains one prevailing core type was described (Ra). Using mutants with defects in LPS core OS synthesis it was demonstrated that Hep residues in the inner core region are recognized by human and murine MBL due to their accessibility in truncated and incomplete core OS (12). Even though the inner core is common for the majority of enterobacterial LPS and represents MBL-binding motifs, our results indicated also outer core structures as natural MBL ligands. Hep and Hep-Kdo motifs were detected also in the latter region, for example, in P. vulgaris O25 and K. pneumoniae O3, O1, O2, O4, and O5 LPS (28, 33) as well as in numerous H. alvei strains (expressing DS, TS1, and TS2) (Figure 1). The lectin blotting (Figure 5C) and SPR analysis (Figure 5D) revealed recombinant MBL binding to DS-decorated H. alvei PCM 1200 OS1 and OS1 alone. Moreover, interaction of MBL with purified Hep-Kdo-containing motifs was also evidenced (Figure 5D), and determined by Hep residue (but not Kdo) according to the previous reports (12, 62). In spite of manno configuration, Kdo residues (even terminal) might be excluded as an MBL ligand, since deep rough mutants (Re) of S. enterica ser. Typhimurium or Yersinia enterocolitica O3, expressing LPS consisting of lipid A and one, two or three Kdo residues were not recognized (12, 63). Thus, Hep and D-GlcNAc present in outer core regions are the main MBL targets. Any steric obstacles within these motifs hinder MBL access, as was demonstrated for TS-OS1 core type of H. alvei. In TS1, the DS motif is substituted by terminal Gal residue that prevented hMBL binding to H. alvei PCM 1192 (Figure 5C).

Our results indicate a crucial role for MBL-binding motifs within the outer core OS in the recognition of H. alvei LPS by human and murine MBL, induction of an anaphylactoid reaction and rapid death in MDP-sensitized mice. Previously, it was demonstrated that such events were induced by several LPS of smooth bacteria with O-PS that were homopolymers of mannose (K. pneumoniae O3 and O5), able to activate complement via the LP (16). Among six H. alvei LPS with different O-serotypes tested, the intravenous injection of DS-containing LPS (PCM 1200, 1209, and 1190) led to development of severe symptoms of an anaphylactoid reaction and resulted in the death of animals within 30 min. Furthermore, H. alvei PCM 1212 (synthesizing Ra core type, with d-GlcNAc residue in the outer core region) is as toxic for mice as the aforementioned LPS. By contrast, H. alvei PCM 1192 LPS with outer core OS1 substituted with TS1 (preventing MBL binding) was not active. Interestingly, in the case of PCM 1200, 1212, and 1190 LPS, MBL-A was able to recognize not only the core OS (Ra or OS1-DS type) but also the O-PS region. Moreover, MBL-A showed the highest affinity to O-PS of H. alvei PCM 1200 LPS, which was found to be the most toxic (Table 2). Our results demonstrated that MBL-binding motifs in outer core region are sufficient to induce an anaphylactoid reaction in mice; however, the presence of S-LPS in the heterogeneous LPS preparation was mandatory. It might be suggested that similar to SP-D exhibiting O-PS-stabilized reactivity with common core OS of K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and S. enterica ser. Minnesota LPS, the O-PS–MBL interaction may also stabilize residual interactions of the collectin with the core OS region (54, 64).

The data presented here have extended the repertoire of LPS recognized by MBL, including rough forms present in endotoxin preparations from smooth bacteria (Figure 1). Generally, d-GlcNAc or Hep residues in the outer core were common ligands for the lectin. Those structures may be accessible to MBL in vivo not only when LPS O-PS is relatively short but also when endotoxin is released due to bacterial cell damage (for example, after treatment of host with antibiotics). We demonstrated also that the O-PS structure might augment immune responses when recognized by MBL (the example of PCM 1200). We believe that clarifying MBL specificity/affinity may contribute to a better understanding of the role of the LP in Gram-negative infections in general, including those leading to sepsis or endotoxic shock. Species of the family Enterobacteriaceae are responsible for 40–50% of hospital-acquired infections leading to sepsis and septic shock. Over half of cases in the USA is connected with bacteria of the genera Klebsiella, Escherichia, Proteus or Enterobacter, and mortality is in the range of 20–50%. In some cases of invasive infections caused, for example, by K. pneumoniae, E. coli, or Proteus spp., MBL/ficolin-dependent complement activation by common core oligosaccharide regions or MHP might contribute to the severity of infections and sepsis. Although interaction of MBL (or other PAMPs) with LPS is generally beneficial for the host, it may be harmful under certain conditions. Upon antibiotic treatment, aggregates of endotoxin (mixed S- and R-LPS) are released into the bloodstream and activate a host immune response (49). Furthermore, R-LPS was reported to exhibit higher potency in cell activation through the TLR-4/MD-2 receptor (65). Although MBL deficiency has been associated with susceptibility to infections (especially in children or immunocompromised subjects), its contribution to life-threatening events (like post-operative SIRS) has also been proven (66). Our results contribute to a better understanding of MBL–LPS interaction. They also support further development of therapeutic strategies against sepsis based on complement inhibition or complement-related replacement therapies.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Local Ethical Commission for Animal Experimentation with the headquarters in the Ludwik Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy Polish Academy of Sciences (Wroclaw, Poland). The Local Ethical Commission for Animal Experimentation approved all in vivo protocols.

Author Contributions

JL, AS, AM-K, MC, and CL conceived and planned the experiments. AM-K, AM, AS, and JL carried out the experiments with prevailing role of AM-K and AS. JL, MH, AM, and CL prepared OS1- or TS1-specific rabbit antisera. AM-K, AM, and JL isolated some H. alvei LPS. AR and MS isolated and provided the collection of Proteus spp. LPS. AM-K, JL, AS, and MC contributed to the interpretation of the results. JL, AS, MC, and AM-K took the lead in writing the manuscript. All the authors approved the manuscript and provided critical feedback.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Wroclaw Research Centre EIT+ within the project “Biotechnologies and advanced medical technologies”—BioMed (POIG.01.01,02-02-003/08) co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (Operational Programme Innovative Economy, 1.1.2) and the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (project No. N40108432/1944). Publication of the results was supported by Wroclaw Centre of Biotechnology, programme The Leading National Research Centre (KNOW) for years 2014–2018. Wojciech Jachymek and Tomasz Niedziela from the Ludwik Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy, Wroclaw, Poland are acknowledged for their assistance during anaphylaxis-like endotoxic shock induction in vivo. Dr. Yuichi Endo from Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima, Japan is kindly acknowledged for rabbit anti-murine ficolin-A Ab. We are very grateful to Dr. David C. Kilpatrick for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussion.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01498/full#supplementary-material.

Abbreviations

Ab, antibody; AP, alternative pathway; CP, classical pathway; DS, disaccharide; LP, lectin pathway; LPS, lipopolysaccharide, endotoxin; MBL, mannose-binding lectin; MASP, MBL-associated serine proteases; MHP, mannose homopolymer; NHS; normal human serum; OS, oligosaccharide; O-PS, O-specific polysaccharide; PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; R-LPS, rough LPS; S-LPS; smooth LPS; TS, trisaccharide.

References

1. De Pascale G, Cutuli SL, Pennisi MA, Antonelli M. The role of mannose-binding lectin in severe sepsis and septic shock. Mediators Inflamm (2013) 2013:625803. doi:10.1155/2013/625803

2. Hansen S, Thiel S, Willis A, Holmskov U, Jensenius JC. Purification and characterization of two mannan-binding lectins from mouse serum. J Immunol (2000) 164:2610–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2610

3. Liu H, Jensen L, Hansen S, Petersen SV, Takahashi K, Ezekowitz AB, et al. Characterization and quantification of mouse mannan-binding lectins (MBL-A and MBL-C) and study of acute phase responses. Scand J Immunol (2001) 53:489–97. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00908.x

4. Uemura K, Saka M, Nakagawa T, Kawasaki N, Thiel S, Jensenius JC, et al. L-MBP is expressed in epithelial cells of mouse small intestine. J Immunol (2002) 169:6945–50. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6945

5. Wagner S, Lynch NJ, Walter W, Schwaeble WJ, Loos M. Differential expression of the murine mannose-binding lectins A and C in lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs and tissues. J Immunol (2003) 170:1462–5. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1462

6. Lahtinen P, Brzezinska A, Skurnik M. Temperature and growth phase regulate the transcription of the O-antigen gene cluster of Yersinia enterocolitica O:3. Adv Exp Med Biol (2003) 529:289–92. doi:10.1007/0-306-48416-1_55

7. Loos M, Bitter-Suermann D, Dierich M. Interaction of the first (C1), the second (C2) and the fourth (C4) component of complement with different preparations of bacterial lipopolysaccharides and with lipid A. J Immunol (1974) 112:935–40.

8. Morrison DC, Kline LF. Activation of the classical and properdin pathways of complement by bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS). J Immunol (1977) 118:362–8.

9. Roumenina LT, Popov KT, Bureeva SV, Kojouharova M, Gadjeva M, Rabheru S, et al. Interaction of the globular domain of human C1q with Salmonella typhimurium lipopolysaccharide. Biochim Biophys Acta (2008) 1784:1271–6. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.04.029

10. Swierzko A, Lukasiewicz J, Cedzynski M, Maciejewska A, Jachymek W, Niedziela T, et al. New functional ligands for ficolin-3 among lipopolysaccharides of Hafnia alvei. Glycobiology (2012) 22:267–80. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwr119

11. Parej K, Kocsis A, Enyingi C, Dani R, Oroszlan G, Beinrohr L, et al. Cutting edge: a new player in the alternative complement pathway, MASP-1 is essential for LPS-induced, but not for zymosan-induced, alternative pathway activation. J Immunol (2018) 200:2247–52. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1701421

12. Devyatyarova-Johnson M, Rees IH, Robertson BD, Turner MW, Klein NJ, Jack DL. The lipopolysaccharide structures of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Neisseria gonorrhoeae determine the attachment of human mannose-binding lectin to intact organisms. Infect Immun (2000) 68:3894–9. doi:10.1128/IAI.68.7.3894-3899.2000

13. Dumestre-Perard C, Doerr E, Colomb MG, Loos M. Involvement of complement pathways in patients with bacterial septicemia. Mol Immunol (2007) 44:1631–8. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2006.08.008

14. Swierzko A, Kirikae T, Kirikae F, Hirata M, Cedzynski M, Ziolkowski A, et al. Biological activities of lipopolysaccharides of Proteus spp. and their interactions with polymyxin B and an 18-kDa cationic antimicrobial protein (CAP18)-derived peptide. J Med Microbiol (2000) 49:127–38. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-49-2-127

15. Takada H, Hirai H, Fujiwara T, Koga T, Ogawa T, Hamada S. Bacteroides lipopolysaccharides (LPS) induce anaphylactoid and lethal reactions in LPS-responsive and -nonresponsive mice primed with muramyl dipeptide. J Infect Dis (1990) 162:428–34. doi:10.1093/infdis/162.2.428

16. Shibazaki M, Kawabata Y, Yokochi T, Nishida A, Takada H, Endo Y. Complement-dependent accumulation and degradation of platelets in the lung and liver induced by injection of lipopolysaccharides. Infect Immun (1999) 67:5186–91.

17. Vinogradov E, Frirdich E, MacLean LL, Perry MB, Petersen BO, Duus JO, et al. Structures of lipopolysaccharides from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Elucidation of the structure of the linkage region between core and polysaccharide O chain and identification of the residues at the non-reducing termini of the O chains. J Biol Chem (2002) 277:25070–81. doi:10.1074/jbc.M202683200

18. Zhao L, Ohtaki Y, Yamaguchi K, Matsushita M, Fujita T, Yokochi T, et al. LPS-induced platelet response and rapid shock in mice: contribution of O-antigen region of LPS and involvement of the lectin pathway of the complement system. Blood (2002) 100:3233–9. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-01-0252

19. Swierzko AS, Cedzynski M, Kirikae T, Nakano M, Klink M, Kirikae F, et al. Role of the complement-lectin pathway in anaphylactoid reaction induced with lipopolysaccharide in mice. Eur J Immunol (2003) 33:2842–52. doi:10.1002/eji.200323949

20. Takada H, Galanos C. Enhancement of endotoxin lethality and generation of anaphylactoid reactions by lipopolysaccharides in muramyl-dipeptide-treated mice. Infect Immun (1987) 55:409–13.

21. Janda JM, Abbott SL. The genus Hafnia: from soup to nuts. Clin Microbiol Rev (2006) 19:12–8. doi:10.1128/CMR.19.1.12-28.2006

22. Bobko E, Tyras M, Jachymek W. New complete structure of Hafnia alvei clinical isolate strain PCM 2670 semi-rough lipopolysaccharide. Carbohydr Res (2013) 374:67–74. doi:10.1016/j.carres.2013.03.029

23. Lukasiewicz J, Jachymek W, Niedziela T, Kenne L, Lugowski C. Structural analysis of the lipid A isolated from Hafnia alvei 32 and PCM 1192 lipopolysaccharides. J Lipid Res (2010) 51:564–74. doi:10.1194/jlr.M001362

24. Lukasiewicz J, Niedziela T, Jachymek W, Kenne L, Lugowski C. Two Kdo-heptose regions identified in Hafnia alvei 32 lipopolysaccharide: the complete core structure and serological screening of different Hafnia O serotypes. J Bacteriol (2009) 191:533–44. doi:10.1128/JB.00891-08

25. Romanowska E, Katzenellenbogen E, Jachymek W, Niedziela T, Bogulska M, Lugowski C. Non-typical lipopolysaccharide core regions of some Hafnia alvei strains: structural and serological studies. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol (1999) 24:63–71. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01266.x

26. Lukasiewicz J, Jachymek W, Niedziela T, Dzieciatkowska M, Lakomska J, Miedzybrodzki R, et al. Serological characterization of anti-endotoxin serum directed against the conjugate of oligosaccharide core of Escherichia coli type R4 with tetanus toxoid. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol (2003) 37:59–67. doi:10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00104-4

27. Jachymek W, Petersson C, Helander A, Kenne L, Lugowski C, Niedziela T. Structural studies of the O-specific chain and a core hexasaccharide of Hafnia alvei strain 1192 lipopolysaccharide. Carbohydr Res (1995) 269:125–38. doi:10.1016/0008-6215(94)00348-J

28. Vinogradov E, Cedzynski M, Ziolkowski A, Swierzko A. The structure of the core region of the lipopolysaccharide from Klebsiella pneumoniae O3 – 3-Deoxy-alpha-D-manno-octulosonic acid (alpha-Kdo) residue in the outer part of the core, a common structural element of Klebsiella pneumoniae O1, O2, O3, O4, O5, O8, and O12 lipopolysaccharides. Eur J Biochem (2001) 268:1722–9. doi:10.1046/j1432-1327.2001.02047

29. Kijewska M, Kuc A, Kluczyk A, Waliczek M, Man-Kupisinska A, Lukasiewicz J, et al. Selective detection of carbohydrates and their peptide conjugates by ESI-MS using synthetic quaternary ammonium salt derivatives of phenylboronic acids. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom (2014) 25:966–76. doi:10.1007/s13361-014-0857-4

30. Katzenellenbogen E, Gamian A, Romanowska E. Trisaccharide core fragment occurring in lipopolysaccharides of some Hafnia alvei strains. Carbohydr Lett (1998) 3:223–30.

31. Jachymek W, Lugowski C, Romanowska E, Witkowska D, Petersson C, Kenne L. The structure of a core oligosaccharide component from Hafnia alvei strain 32 and 1192 lipopolysaccharides. Carbohydr Res (1994) 251:327–30. doi:10.1016/0008-6215(94)84295-7

32. Katzenellenbogen E, Gamian A, Romanowska E, Dabrowski U, Dabrowski J. 3-Deoxy-octulosonic acid-containing trisaccharide fragment of an unusual core type of some Hafnia alvei lipopolysaccharides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (1993) 194:1058–64. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1993.1929

33. Vinogradov E, Cedzynski M, Rozalski A, Ziolkowski A, Swierzko A. The structure of the carbohydrate backbone of the core-lipid A region of the lipopolysaccharide from Proteus vulgaris serotype O25. Carbohydr Res (2000) 328:533–8. doi:10.1016/S0008-6215(00)00134-8

34. Petersson C, Niedziela T, Jachymek W, Kenne L, Zarzecki P, Lugowski C. Structural studies of the O-specific polysaccharide of Hafnia alvei strain PCM 1206 lipopolysaccharide containing D-allothreonine. Eur J Biochem (1997) 244:580–6. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00580.x

35. Palusiak A, Maciejewska A, Lugowski C, Rozalski A. The amide of galacturonic acid with lysine as an immunodominant component of the lipopolysaccharide core region from Proteus penneri 42 strain. Acta Biochim Pol (2014) 61:129–32.

36. Cuatrecasas P, Wilchek M, Anfinsen CB. Selective enzyme purification by affinity chromatography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1968) 61:636–43. doi:10.1073/pnas.61.2.636

37. Srere PA, Mattiasson B, Mosbach K. An immobilized three-enzyme system: a model for microenvironmental compartmentation in mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1973) 70:2534–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.9.2534

38. Westphal O, Jann K. Bacterial lipopolysacharides: extraction with phenol-water and further applications of the procedure. Methods Carbohydr Chem (1965) 5:83–9.

39. Palusiak A, Dzieciatkowska M, Sidorczyk Z. Application of two different kinds of sera against the Proteus penneri lipopolysaccharide core region in search of epitopes determining cross-reactions with antibodies. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) (2008) 56:135–40. doi:10.1007/s00005-008-0012-7

40. Yi EC, Hackett M. Rapid isolation method for lipopolysaccharide and lipid A from gram-negative bacteria. Analyst (2000) 125:651–6. doi:10.1039/b000368i

41. Man-Kupisinska A, Bobko E, Gozdziewicz TK, Maciejewska A, Jachymek W, Lugowski C, et al. Fractionation and analysis of lipopolysaccharide-derived oligosaccharides by zwitterionic-type hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. Carbohydr Res (2016) 427:29–37. doi:10.1016/j.carres.2016.03.024

42. Tsai CM, Frasch CE. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem (1982) 119:115–9. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-X

43. Cedzynski M, Szemraj J, Swierzko AS, Bak-Romaniszyn L, Banasik M, Zeman K, et al. Mannan-binding lectin insufficiency in children with recurrent infections of the respiratory system. Clin Exp Immunol (2004) 136:304–11. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02453.x

44. Swierzko AS, Szala A, Sawicki S, Szemraj J, Sniadecki M, Sokolowska A, et al. Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) and MBL-associated serine protease-2 (MASP-2) in women with malignant and benign ovarian tumours. Cancer Immunol Immunother (2014) 63:1129–40. doi:10.1007/s00262-014-1579-y

45. Presanis JS, Hajela K, Ambrus G, Gal P, Sim RB. Differential substrate and inhibitor profiles for human MASP-1 and MASP-2. Mol Immunol (2004) 40:921–9. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2003.10.013

46. Petersson C, Jachymek W, Kenne L, Niedziela T, Lugowski C. Structural studies of the O-specific chain of Hafnia alvei strain PCM 1190 lipopolysaccharide. Carbohydr Res (1997) 298:219–27. doi:10.1016/S0008-6215(96)00311-4

47. Katzenellenbogen E, Zatonsky GV, Kocharova NA, Rowinski S, Gamian A, Shashkov AS, et al. Structure of the O-specific polysaccharide of Hafnia alvei PCM 1196. Carbohydr Res (2001) 330:523–8. doi:10.1016/S0008-6215(01)00003-9

48. Petersen SV, Thiel S, Jensen L, Steffensen R, Jensenius JC. An assay for the mannan-binding lectin pathway of complement activation. J Immunol Methods (2001) 257:107–16. doi:10.1016/S0022-1759(01)00453-7

49. Ulmer AJ, Rietschel ET, Zahringer U, Heine A. Lipopolysaccharide: structure, bioactivity, receptors, and signal transduction. Trends Glycosci Glycotechnol (2002) 14:53–68. doi:10.4052/tigg.14.53

50. Hasunuma R, Morita H, Tanaka S, Ryll R, Freudenberg MA, Galanos C, et al. Differential clearance and induction of host responses by various administered or released lipopolysaccharides. J Endotoxin Res (2001) 7:421–9. doi:10.1179/096805101101533025

51. Pupo E, Lindner B, Brade H, Schromm AB. Intact rough- and smooth-form lipopolysaccharides from Escherichia coli separated by preparative gel electrophoresis exhibit differential biologic activity in human macrophages. FEBS J (2013) 280:1095–111. doi:10.1111/febs.12104

52. Charchaflieh J, Wei J, Labaze G, Hou YJ, Babarsh B, Stutz H, et al. The role of complement system in septic shock. Clin Dev Immunol (2012) 2012:407324. doi:10.1155/2012/407324

53. Michalski M, Swierzko A St, Lukasiewicz J, Man-Kupisinska A, Karwaciak I, Przygodzka P, et al. Ficolin-3 activity towards the opportunistic pathogen, Hafnia alvei. Immunobiology (2015) 220:117–23. doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2014.08.012

54. Sahly H, Ofek I, Podschun R, Brade H, He Y, Ullmann U, et al. Surfactant protein D binds selectively to Klebsiella pneumoniae lipopolysaccharides containing mannose-rich O-antigens. J Immunol (2002) 169:3267–74. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3267

55. Jensenius H, Klein DC, van Hecke M, Oosterkamp TH, Schmidt T, Jensenius JC. Mannan-binding lectin: structure, oligomerization, and flexibility studied by atomic force microscopy. J Mol Biol (2009) 391:246–59. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.083

56. Kjaer TR, Jensen L, Hansen A, Dani R, Jensenius JC, Dobo J, et al. Oligomerization of mannan-binding lectin dictates binding properties and complement activation. Scand J Immunol (2016) 84:12–9. doi:10.1111/sji.12441

57. Jensen PH, Weilguny D, Matthiesen F, McGuire KA, Shi L, Hojrup P. Characterization of the oligomer structure of recombinant human mannan-binding lectin. J Biol Chem (2005) 280:11043–51. doi:10.1074/jbc.M412472200

58. Ono K, Nishitani C, Mitsuzawa H, Shimizu T, Sano H, Suzuki H, et al. Mannose-binding lectin augments the uptake of lipid A, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli by Kupffer cells through increased cell surface expression of scavenger receptor A. J Immunol (2006) 177:5517–23. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5517

59. Shiratsuchi A, Watanabe I, Ju JS, Lee BL, Nakanishi Y. Bridging effect of recombinant human mannose-binding lectin in macrophage phagocytosis of Escherichia coli. Immunology (2008) 124:575–83. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02811.x

60. Lukacova M, Barak I, Kazar J. Role of structural variations of polysaccharide antigens in the pathogenicity of Gram-negative bacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect (2008) 14:200–6. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01876.x

61. Maldonado RF, Sa-Correia I, Valvano MA. Lipopolysaccharide modification in Gram-negative bacteria during chronic infection. FEMS Microbiol Rev (2016) 40:480–93. doi:10.1093/femsre/fuw007

62. Brade L, Brade H, Fischer W. A 28 kDa protein of normal mouse serum binds lipopolysaccharides of gram-negative and lipoteichoic acids of gram-positive bacteria. Microb Pathog (1990) 9:355–62. doi:10.1016/0882-4010(90)90069-3

63. Kasperkiewicz K, Swierzko AS, Bartlomiejczyk MA, Cedzynski M, Noszczynska M, Duda KA, et al. Interaction of human mannose-binding lectin (MBL) with Yersinia enterocolitica lipopolysaccharide. Int J Med Microbiol (2015) 305:544–52. doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2015.07.001

64. Kuan SF, Rust K, Crouch E. Interactions of surfactant protein D with bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Surfactant protein D is an Escherichia coli-binding protein in bronchoalveolar lavage. J Clin Invest (1992) 90:97–106. doi:10.1172/JCI115861

65. Huber M, Kalis C, Keck S, Jiang Z, Georgel P, Du X, et al. R-form LPS, the master key to the activation of TLR4/MD-2-positive cells. Eur J Immunol (2006) 36:701–11. doi:10.1002/eji.200535593

66. Pagowska-Klimek I, Swierzko AS, Michalski M, Glowacka E, Szala-Pozdziej A, Sokolowska A, et al. Activation of the lectin pathway of complement by cardiopulmonary bypass contributes to the development of systemic inflammatory response syndrome after paediatric cardiac surgery. Clin Exp Immunol (2016) 184:257–63. doi:10.1111/cei.12763

Keywords: lipopolysaccharide, endotoxin, anaphylactoid shock, complement, mannose-binding lectin, Hafnia

Citation: Man-Kupisinska A, Swierzko AS, Maciejewska A, Hoc M, Rozalski A, Siwinska M, Lugowski C, Cedzynski M and Lukasiewicz J (2018) Interaction of Mannose-Binding Lectin With Lipopolysaccharide Outer Core Region and Its Biological Consequences. Front. Immunol. 9:1498. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01498

Received: 24 April 2018; Accepted: 15 June 2018;

Published: 29 June 2018

Edited by:

Robert Braidwood Sim, University of Oxford, United KingdomReviewed by:

Teizo Fujita, Fukushima Medical University, JapanPéter Gál, Institute of Enzymology (MTA), Hungary

Copyright: © 2018 Man-Kupisinska, Swierzko, Maciejewska, Hoc, Rozalski, Siwinska, Lugowski, Cedzynski and Lukasiewicz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jolanta Lukasiewicz, am9sYW50YS5sdWthc2lld2ljekBpaXRkLnBhbi53cm9jLnBs

Aleksandra Man-Kupisinska1

Aleksandra Man-Kupisinska1 Anna S. Swierzko

Anna S. Swierzko Antoni Rozalski

Antoni Rozalski Maciej Cedzynski

Maciej Cedzynski Jolanta Lukasiewicz

Jolanta Lukasiewicz