- 1Center of Excellence for Molecular Biology and Genomics of Shrimp, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

- 2Omics Sciences and Bioinformatics Center, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), the small non-coding RNAs, play a pivotal role in post-transcriptional gene regulation in various cellular processes. However, the miRNA function in shrimp antiviral response is not clearly understood. This research aims to uncover the function of pmo-miR-315, a white spot syndrome virus (WSSV)-responsive miRNAs identified from Penaeus monodon hemocytes during WSSV infection. The expression of the predicted pmo-miR-315 target mRNA, a novel PmPPAE gene called PmPPAE3, was negatively correlated with that of the pmo-miR-315. Furthermore, the luciferase assay indicated that the pmo-miR-315 directly interacted with the target site in PmPPAE3 suggesting the regulatory role of pmo-miR-315 on PmPPAE3 gene expression. Introducing the pmo-miR-315 into the WSSV-infected shrimp caused the reduction of the PmPPAE3 transcript level and, hence, the PO activity activated by the PmPPAE3 whereas the WSSV copy number in the shrimp hemocytes was increased. Taken together, our findings state a crucial role of pmo-miR-315 in attenuating proPO activation via PPAE3 gene suppression and facilitating the WSSV propagation in shrimp WSSV infection.

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNA molecules transcribed from the genome and subsequently processed by Drosha and Dicer nucleases (1). Generally, when miRNA complementary binds to the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) of mRNAs, it can cleave the target mRNAs or inhibits the mRNA translation, thus, down-regulating the corresponding gene expression. In addition, it has been reported that the miRNAs can also bind to the 5′-untranslated regions (5′-UTR) (2) or even within the coding sequence of mRNAs (3). Accordingly, miRNA's function involves the regulation of various biological processes including the host-virus interaction upon viral infection. During virus infection, viral miRNAs downregulate specific viral and cellular mRNAs to establish a host environment conducive to the completion of viral life cycle. At the same time, the host miRNAs modulate both cellular and viral transcripts exerting influence over immune responses (4).

In crustaceans, there are many reports showing that the host miRNAs can regulate the expression of the host and viral genes and vice versa. In 2012, the first large-scale miRNA characterization in white spot syndrome virus (WSSV)-infected Marsupenaeus japonicas lymphoid organ has been reported (5). Several cellular WSSV-responsive miRNAs play important roles in shrimp immunity including apoptosis pathway (6, 7), phagocytosis (8), NF-kB pathway (9), and JAK/STAT pathway (10). Furthermore, the WSSV miRNAs were also identified and probably could target either the host or viral genes. In the WSSV-infected M. japonicas, the viral miRNAs could target virus transcripts and further promote virus infection (11). In the meantime, a viral miRNA, WSSV-miR-N24, could target the shrimp apoptotic gene, caspase 8, and further represses the apoptosis of shrimp hemocytes (12). Despite this, the study on the host miRNAs-virus relationship in shrimp is still very limited.

In Penaeus monodon, the 60 known miRNA homologs that are expressed in the hemocytes of WSSV-challenged shrimp at the early and late phases of infection have been identified (13). Their immune-related gene targets in apoptosis pathway, antimicrobial peptide, prophenoloxidase system, signal transduction, proteinase and proteinase inhibitor, blood clotting system, and heat shock protein have also been predicted. Among them, the pmo-miR-315 was found to be a highly up-regulated miRNA in response to WSSV challenge and its target gene was predicted to be a novel prophenoloxidase-activating enzyme, called PmPPAE3 (13). According to the previous reports, the miR-315 was also up-regulated after WSSV infection in lymphoid organ of M. japonicas (5) and hepatopancreas of F. chinensis (14). However, the function of miR-315 in shrimp immunity against WSSV infection is still unknown. In this research, the cellular mRNA target of pmo-miR-315 was confirmed. Moreover, the role of pmo-miR-315 in WSSV-infected shrimp was investigated.

Materials and Methods

Shrimp and WSSV

Healthy black tiger shrimp, P. monodon, of about 3–5 and 15–20 g in size were purchased from a farm in Surat Thani Province, Thailand. Due to the Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the use of animals for scientific purposes by the National Research Council of Thailand, this project was conducted according to the animal use protocol number 1823006 approved by the Chulalongkorn University Animal Care And Use Committee (CU-ACUC). The animals were reared in laboratory tanks at ambient temperature, and maintained in aerated water with a salinity of 15 ppt for at least 7 days before use.

The WSSV stock used for the experimental infection was prepared according to the method described by Xie et al. (15) and stored at −80°C until used. One microliter of WSSV stock was 10-fold serially diluted with 0.85% NaCl to 10−7 dilution. The diluted WSSV of 50 μL was injected into the second abdominal segment of the shrimp. The mortality was recorded daily. This dosage caused 100% mortality within 3–4 days after injection and was used for all subsequent viral infection experiment.

This project has been reviewed and approved by the CU-IBC (Approval number: SCI-01-001) to be in accordance with the levels of risk in pathogens and animal toxins listed in the Risk Group of Pathogen and Animal Toxin (2017) published by the Department of Medical Sciences, Ministry of Public Health, the Pathogen and Animal Toxin Act (2015) and Biosafety Guidelines for Modern Biotechnology, BIOTEC (2016).

Pmo-miR-315 Mimic and Its Scramble miRNA

The mimic microRNAs used in this research were synthesized by a commercial service GenePharma (Shanghai). The sequences of mimic pmo-miR-315 and pmo-miR-315 scramble were 5′-UUUUGAUUGUUGCUCAGAAG-3′ and 5′-GUGGUUAGCGUUAAUUCUAU-3′, respectively. The sequences of miR-315 inhibitor (AMO-miR-315) and miR-315 inhibitor scramble were 5′-CUUCUGAGCAACAAUCAAAA-3′ and 5′-ACGAACCUACGAUAAUAAUC-3′.

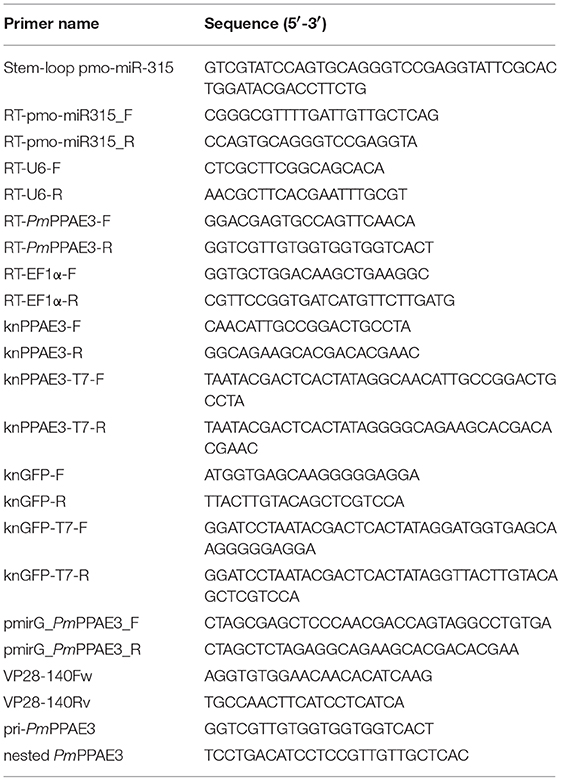

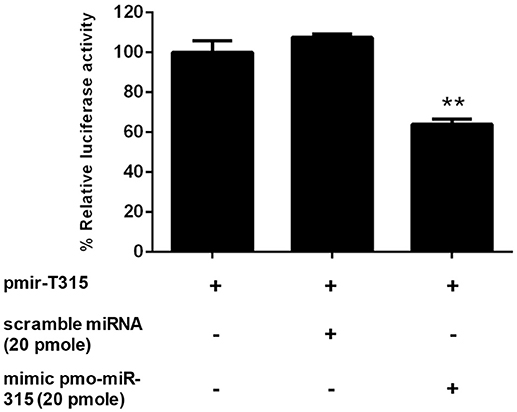

Pmo-miR-315 Expression in WSSV-Infected Shrimp Tissues

The expression of pmo-miR-315 in various shrimp tissues including hemocytes, gill, lymphoid organ and stomach of WSSV-infected P. monodon was determined by stem-loop quantitative real time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). The pooled total RNA of each tissue from 3 WSSV-infected individuals at 0, 6, 24, and 48 hpi was prepared using mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Life Technologies) and 1 μg was used as templates for the first strand stem-loop cDNA synthesis using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). The qPCR was performed using SsoFast™ EvaGreen® Supermix (Bio-Rad) on CFX96 touch real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad), where each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The amplification condition was 98°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 30 s. A non-coding small nuclear RNA, U6, was used as a reference. The primer sequences for stem-loop cDNA synthesis, pmo-miR-315: RT-pmo-miR315_F and RT-pmo-miR315_R, and for U6: RT-U6-F and RT-U6-R, are shown in Table 1. The miRNA relative expression level was calculated using the equation by Pfaffl (16).

In addition, the expression of the target mRNA of pmo-miR-315, a putative prophenoloxidase-activating enzyme (PmPPAE3), was determined in hemocytes of shrimp infected with WSSV at 0, 6, 24, and 48 hpi. The total RNA from hemocytes of 3 individuals was reverse-transcribed into the first strand cDNA using oligo (dT) as a primer following the manufacturer's instruction for RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo scientific). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed as described previously using EF-1α gene as an internal control.

Specificity and Inhibitory Activity of Pmo-miR-315 on Target PmPPAE3 mRNA

First, the pmirGLO vector (Promega) harboring the 200 bp PmPPAE3 gene fragment that contained the pmo-miR-315 binding region (Figure 2A) was constructed. The PmPPAE3 gene fragment was PCR amplified from P. monodon hemocyte cDNAs using the gene specific primers, pmirG_PmPPAE_F and pmirG_PmPPAE_R (Table 1), digested with SacI and XbaI (New England Biolabs), cloned into the likewise double digested pmirGLO, and transformed into an Escherichia coli stain XL1-blue. The recombinant plasmid, pmir-T315, was extracted and sequenced to confirm the correctness of the sequences (Macrogen, Korea).

To investigate the inhibitory activity of pmo-miR-315 on the PmPPAE3 gene target sequence, dual-luciferase activity assay was performed. The HEK293T cell culture of 8 × 104 cells/well was seeded into a 24-well plate. At 24 h after seeding, 200 ng of pmir-T315 and 20 pmole of mimic miRNA (pmo-miR-315 or scramble) were co-transfected into the HEK293T cells using the Effectene® transfection reagent (Qiagen). The luciferase activity was measured using Dual-luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega) at 48 h post-transfection. The control cells were transfected with pmir-T315 alone and co-transfected pmir-T315 with mimic miRNA scramble.

Introducing and Silencing of Pmo-miR-315 in WSSV-Infected Shrimp

To confirm the inhibitory effect of pmo-miR-315 on the PmPPAE3 target gene expression in shrimp after WSSV infection, the exogenous pmo-miR-315 mimic and anti-pmo-miR-315 (AMO-miR-315) were introduced into the WSSV-infected shrimp and the expression levels of pmo-miR-315 and target gene were quantified.

To study the effect of pmo-miR-315 in vivo, the exogenous pmo-miR-315 was introduced into the shrimp by injection. For pmo-miR-315 silencing, the AMO-miR-315 was injected into the shrimp. In these experiments, shrimp were divided into five groups of three individuals each. The first group was injected with 0.85% NaCl used as an injection control. The miRNA and AMO control groups were shrimp injected with scramble miRNA or scramble AMO-miR-315, respectively. The two test groups were shrimp injected with pmo-miR-315 mimic or AMO-miR-315. At 2 h after the first injection, all groups were muscularly injected with WSSV. After 48 h post-WSSV infection, shrimp hemolymph was collected. The total RNA was extracted and used for the first-strand cDNA production. The expression level of pmo-miR-315 and putative PmPPAE3 was determined by qRT-PCR.

Analysis of WSSV Copy Number Using qRT-PCR

To study the effect of pmo-miR-315 on WSSV replication, the WSSV copy number was also investigated according to a method described by Mendoza-Cano and Sánchez-Paz (17). The genomic DNA of WSSV-infected shrimp hemocytes was extracted using a FavorPrep™ Tissue Genomic DNA Extraction Mini Kit (Favorgen). The quantity and quality of genomic DNA was determined by NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Sciencetific) and 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis.

The qRT-PCR was performed in triplicates of 10 μL reaction containing 5 μL Luna® Universal qPCR Master mix (New England Biolabs) and 1.5 μL genomic DNA template (10 ng/ μL) and 250 nM VP28-140Fw and VP28-140Rv (Table 1). The amplification condition was 98°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 61°C for 30 s. The plasmid containing a highly conserved region of the WSSV VP28 gene, was used to generate a standard curve for the determination of WSSV copy number.

Phenoloxidase Activity Assay

The phenoloxidase (PO) activity was determined in the hemolymph of WSSV- infected shrimp. The shrimp hemolymph was collected at 48 h post-WSSV infection and the PO activity was measured using a method modified from Sutthangkul et al. (18). Briefly, 50 μL of hemolymph was mixed with 25 μL of 3 mg/mL freshly prepared L-3, 4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA; Fluka) and 25 μL of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0. The absorbance at 490 nm was monitored. The amount of hemolymph proteins was measured by the Bradford method (19). The PO activity was recorded as A490/mg total protein/min.

Identification of Full-Length cDNA of Putative PmPPAE3

According to our previous report on pmo-miR-315 target prediction (13), the partial nucleotide sequence of PmPPAE3 was obtained from P. monodon EST database. To identify the full-length cDNA, the 5′-RACE was performed using a SMARTer™ RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The specific primers of partial putative PmPPAE3 gene were designed, which are pri-PmPPAE3 and nested PmPPAE3 (Table 1). The primary and nested-PCR were used to amplify the 5′-RACE cDNA library using Advantage® 2 polymerase mix (Clontech). The PCR product was analyzed by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The nested PCR product was purified and cloned into the pGEM-T easy vector (Promega) and transformed into E. coli XL1-blue. The positive clone was selected and sequenced by a commercial service (Macrogen, Korea). The 5′-RACE PmPPAE3 nucleotide sequence was analyzed and combined with the starting PmPPAE3 sequence from the EST library.

The full-length cDNA of putative PmPPAE3 was analyzed using a Blast program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). The open reading frame (ORF) and the encoded amino acid sequence were predicted using ExPASy software (http://web.expasy.org/translate/). The putative signal peptide cleavage site was predicted by SignalP 4.1 server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/). Moreover, the structural protein domains were analyzed by a simple modular architecture research tool program (SMART) (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/).

Multiple amino acid sequence alignment was performed using the Clustal Omega program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk//Tools/msa/clustalo/). The deduced amino acid sequence of PmPPAE3 was aligned with other insect and crustacean PPAEs including Bombyx mori PO-activating enzyme (BmPAE: NP_001036832.1); Manduca sexta proPO-activating proteinase 1 (MsPAP1: AF059728), Holotrichia diomphalia proPO-activating factor I (HdPPAFI: AB013088), Glossina morsitans (GmPPAE: ABC84592) and Drosophila melanogaster melanization protease1 (DmMP1: NM141193); P. monodon proPO-activating enzyme 1, 2, and 3 (PmPPAE1: FJ595215, PmPPAE2: FJ620685, PmPPAE3: MH325330), Litopenaeus vannamei proPO-activating enzyme (LvPPAE: AFW98991.1), Fenneropenaeus chinensis proPO-activating enzyme (FcPPAE: AFW98985.1) and Pacifastacus leniusculus proPO-activating enzyme (PlPPAE: AJ007668). An unrooted phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method based on the amino acid sequences using MEGA 7 software (20). The bootstrap sampling was reiterated 1000 times.

Tissue Distribution Analysis of PmPPAE3 Gene

The PmPPAE3 gene expression in various tissues including hemocytes, gill, lymphoid organ, and stomach of healthy unchallenged P. monodon was analyzed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. The total RNA of each tissue was extracted by Tri reagent (Geneaid) and used for the first-strand cDNA synthesis using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific). The PCR reaction was performed using the PmPPAE3 specific primer pair (Table 1) and the EF-1α was used as an internal control. The expression profile was analyzed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Effect of PmPPAE3 Gene Silencing on PO Activity in Shrimp

The function of PmPPAE3 in shrimp was characterized using a RNA interference technique. The PmPPAE3 DNA template was amplified from normal shrimp cDNA with gene specific primers (knPPAE3-F, knPPAE3-R, knPPAE3-T7-F, and knPPAE3-T7-R) as shown in Table 1. In addition, the dsRNA of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) as the negative control, was prepared from the pEGFP-1 vector (Clontech) using the knGFP-F, knGFP-R, knGFP-T7-F, and knGFP-T7-R (Table 1). The PmPPAE3-dsRNA and GFP-dsRNA were prepared using T7 RiboMAX™ Express Large Scale RNA Production System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

The P. monodon of approximately 3 g body weight were divided into two groups of three individuals each. The first (control) group was injected with 5 μg/g shrimp of GFP-dsRNA, whilst the second group, the PmPPAE3 knockdown, was injected with 5 μg/g shrimp PmPPAE3-dsRNA. The hemolymph of individual shrimp was collected at 48 h post-injection. Then, the expression level of PmPPAE3 gene and also the PO activity were measured as described above.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. One-way ANOVA with Duncan's multiple range test was used to identify statistically significant differences with SPSS software (version 17.0). Data are presented as means ± 1 standard deviations of three biological replications. The statistical significance of differences among means was calculated by the paired-samples t-test where the significance was accepted at the P-value < 0.05.

Results

Expression of Pmo-miR-315 in Tissues of WSSV-Infected Shrimp

Previously, the differentially expressed miRNAs in hemocytes of WSSV-infected shrimp were identified (13). Among them, the pmo-miR-315 was highly up-regulated at 48 h post-WSSV infection. The pmo-miR-315 expression level in various tissues including hemocytes, gill, lymphoid organ, and stomach in WSSV-infected shrimp at 0, 6, 24, and 48 hpi was further studied. Although, the pmo-miR-315 expression was observed in all tissues tested, the significant response to WSSV infection were found only in hemocytes, in which it was up-regulated at 24 and 48 hpi for about 5- and 30-fold compared with that at 0 hpi (Figure 1). Our results suggested that the pmo-miR-315 was the WSSV-responsive miRNA that might have a function in shrimp immune response.

Figure 1. The expression of pmo-miR-315 in WSSV-infected shrimp tissues. Quantitative stem-loop real-time RT-PCR was performed to determine the expression level of pmo-miR-315 in hemocytes, gill, lymphoid organ and stomach at 0, 6, 24, and 48 hpi. Using U6 as an internal control, the relative expression level of miR-315 was calculated. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The * and ** indicate the significant difference at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

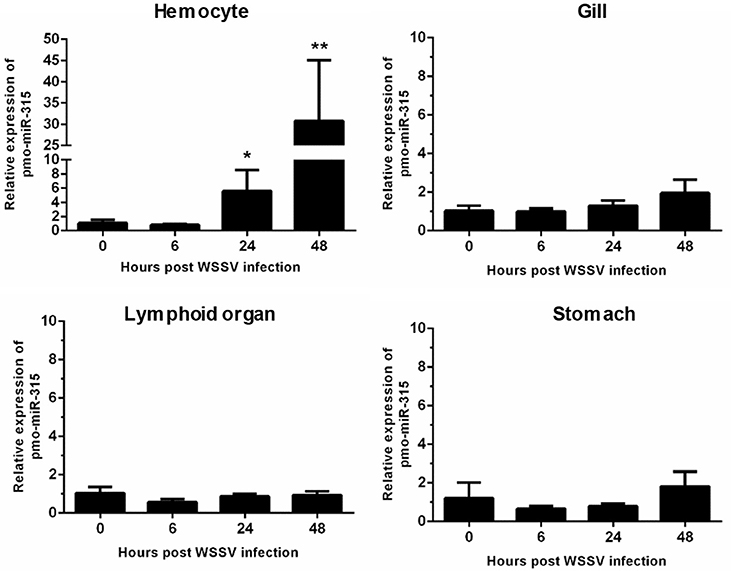

Expression of Pmo-miR-315 Target Gene in WSSV-Infected Shrimp Hemocytes

As stated before, the target mRNA of pmo-miR-315 has been predicted as a putative prophenoloxidase-activating enzyme (PmPPAE) by bioinformatic approaches (13). The PPAE is known as an enzyme that converts the prophenoloxidase (proPO) to active phenoloxidase (PO) in cascades of the proPO system (21). Previously, two isoforms of PPAEs including PmPPAE1 and PmPPAE2 were identified in P. monodon (22, 23). Preliminary analysis showed that the sequence of target mRNA of pmo-miR-315 was a novel isoform of PmPPAE. Herein, therefore, it was named as PmPPAE3. The RNA hybrid software used to analyze the structure and stability of miRNA/mRNA duplex showed that the seed region of pmo-miR-315 was perfectly complementary to the target sequence located on the coding sequence of PmPPAE3 mRNA (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. The pmo-miR-315 target mRNA, prophenoloxidase-activating enzyme 3 (PmPPAE3). (A) The pmo-miR-315/PmPPAE3 base pairing and the binding energy was predicted using RNA hybrid software. The number in bracket indicates the position of nucleotide of pmo-miR-315 target site on the PmPPAE3 CDS. (B) The relative expression level of PmPPAE3 gene at 0, 6, 24, and 48 h post-WSSV infection was investigated. The EF-1α gene was used as an internal control. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The ** indicates the significant difference at P < 0.05.

The possibility of PmPPAE3 transcript on being the pmo-miR-315 target was evaluated by the determination of the pattern of PmPPAE3 gene expression in comparison to that of pmo-miR-315. The expression of PmPPAE3 transcript was dramatically decreased by about 5-fold at 24 and 48 hpi compared with that at 0 hpi (Figure 2B). The negative correlation of expression pattern of pmo-miR-315 (Figure 1A) and PmPPAE3 (Figure 2B) during WSSV infection was noted, suggesting that the pmo-miR-315 was likely to inhibit the PmPPAE3 expression.

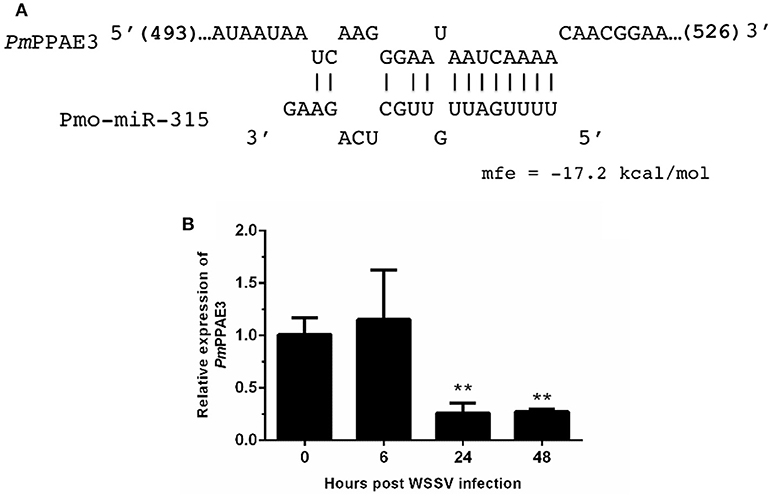

Interaction Between Pmo-miR-315 and PmPPAE3 in vitro

The specific interaction of pmo-miR-315 with target mRNA binding site on PmPPAE3 coding sequence was confirmed in vitro in HEK293T cell line. Either pmo-miR-315 mimic or its scramble miRNA and the luciferase reporter plasmid containing pmo-miR-315 binding site of PmPPAE3 (pmir-T315) were co-transfected into HEK293T cells and then assayed for the luciferase activity. The results showed that in the presence of the mimic pmo-miR-315, the luciferase activity was reduced by about 36% compared with the reaction containing scramble miRNA (Figure 3). The reduction of luciferase activity suggested the specific binding of mimic pmo-miR-315 to miRNA-binding site of PmPPAE3.

Figure 3. The pmo-miR-315/PmPPAE3 interaction by luciferase reporter assay. The target sequence of pmo-miR-315 from PmPPAE3 was amplified and cloned into the pmirGLO vector (pmir-T315). The pmo-miR-315 mimic or scramble pmo-miR-315 were co-transfected with pmir-T315 using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen) into HEK293T cells. At 48 h after transfection, the luciferase activity was measured using a Dual-luciferase® reporter assay system (Promega). The data shown is derived from triplicate experiments. The ** indicates significant difference (P < 0.01).

Characterization of PmPPAE3 Gene

As mentioned above, the PmPPAE3 entails the shrimp immunity against WSSV. The function of PPAE is generally involved in the proPO system as reported previously by Charoensapsri et al. (22), and Charoensapsri et al. (23). Therefore, the function of PmPPAE3 in the proPO system was investigated. The full-length gene of PmPPAE3 was identified (Supplementary Figure 1). Using the 5′-RACE technique, the PmPPAE3 full-length gene of 2,988 bp including 5′-UTR of 147 bp, 3′-UTR of 909 bp and the ORF of 1,932 bp encoding for 643 amino acid residue protein was obtained.

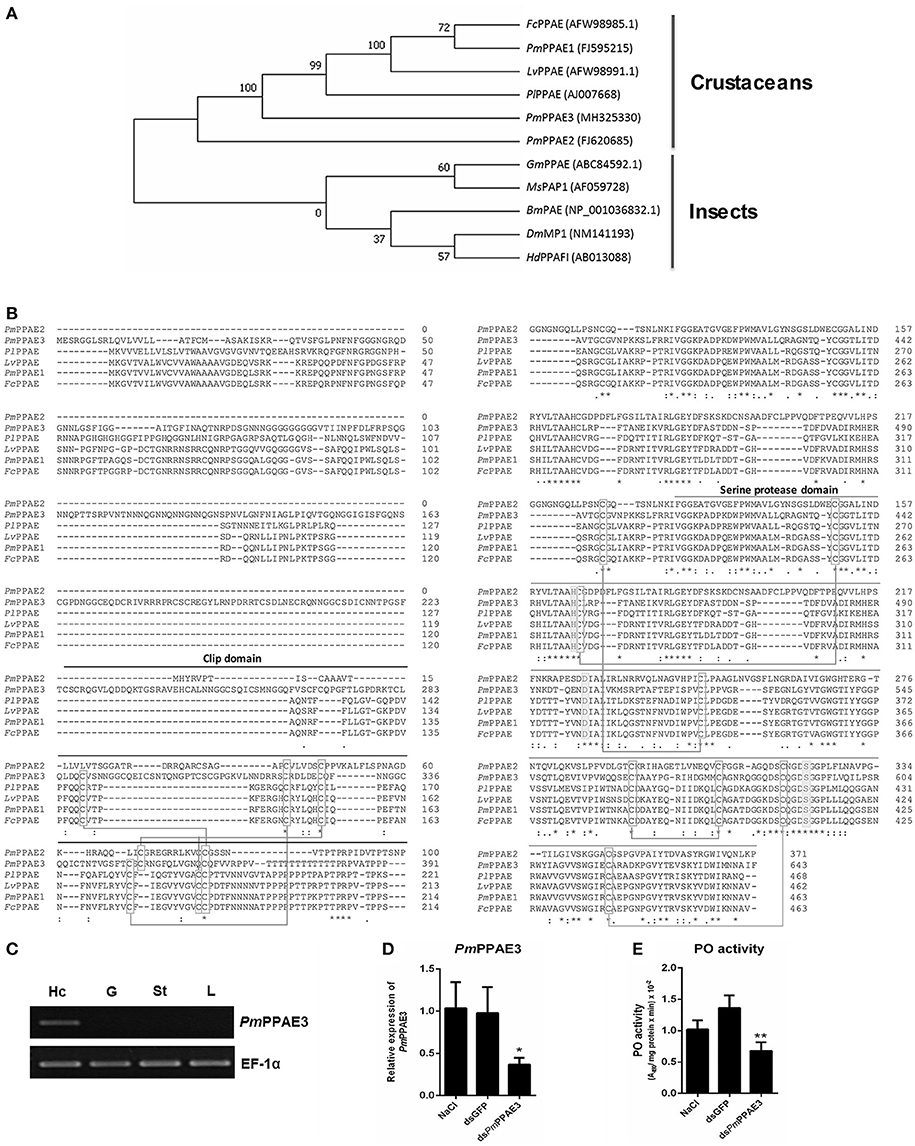

The phylogenetic tree constructed based on the deduced amino acid sequences corresponding to the ORFs of PPAEs from crustaceans and insects showed that the PPAEs are clustered into the crustacean and insect lineages. (Figure 4A). Amino acid sequence alignment of insect and crustacean PPAEs showed the conserved patterns of a clip domain, the serine proteinase domain, and the catalytic triad of histidine, aspartic acid, and serine residues (Figure 4B). Comparing with previously identified crustacean PPAEs, the PmPPAE3 showed about 46.43, 46.31, and 45.98% identity with FcPPAE, LvPPAE and PmPPAE1, respectively. Like the PmPPAE1 and PmPPAE2, the PmPPAE3 was specifically expressed in shrimp hemocytes (Figure 4C). Lastly, the function of PmPPAE3 in the proPO system was further investigated by RNA interference (Figure 4D). The PmPPAE3 gene knockdown dramatically reduced the PO activity in shrimp hemolymph (Figure 4E) suggesting its important role in the proPO system.

Figure 4. Characterization of PmPPAE3 gene. (A) Phylogenetic analysis of PPAEs from various organisms including crustaceans and insects, e.g., B. mori PO-activating enzyme (BmPAE); M. sexta proPO-activating proteinase 1 (MsPAP1), H. diomphalia proPO-activating factor I (HdPPAFI), G. morsitans (GmPPAE) and D. melanogaster melanization protease1 (DmMP1); shrimp P. monodon proPO-activating enzymes 1, 2 and 3 (PmPPAE1, PmPPAE2, PmPPAE3), shrimp, L. vannamei proPO-activating enzyme (LvPPAE), F. chinensis proPO-activating enzyme (FcPPAE), and crayfish P. leniusculus proPO-activating enzyme (PlPPAE), was performed using ClustaX 2.1 and MEGA7 softwares. (B) Multiple alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of PmPPAE3 with other crustacean PPAEs was conducted using the Clustal Omega program. The conserved features of PPAEs such as the disulfide bond, the catalytic triad (histidine, aspartic acid, and serine residues), the clip domain, and the serine proteinase domain are shown. (C) The representative result of PmPPAE3 gene tissue distribution analysis by semi-quantitative RT-PCR in the hemocytes (Hc), gill (G), stomach (St), and lymphoid organ (L), is shown. In this analysis, the EF-1α transcript was used as an internal control. All experiments were performed in triplicate. (D) The PmPPAE3 gene knockdown using PmPPAE3-dsRNA was performed to reveal the functional role of PmPPAE in proPO activating system. The effectiveness of the PmPPAE3 gene knockdown is shown. Hemocytes collected from the control groups of 0.85% NaCl and dsGFP injected shrimp and from the experimental shrimp injected with PmPPAE3-dsRNA was analyzed for the expression of PmPPAE3 gene by qRT-PCR using the EF-1α transcript as an internal control. (E) The PO activity was assayed in the PmPPAE3 knockdown shrimp hemocytes. The data are derived from three independently replicated experiments. The * and ** indicate the significant difference at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

Role of Pmo-miR-315 in WSSV-Infected Shrimp Hemocytes

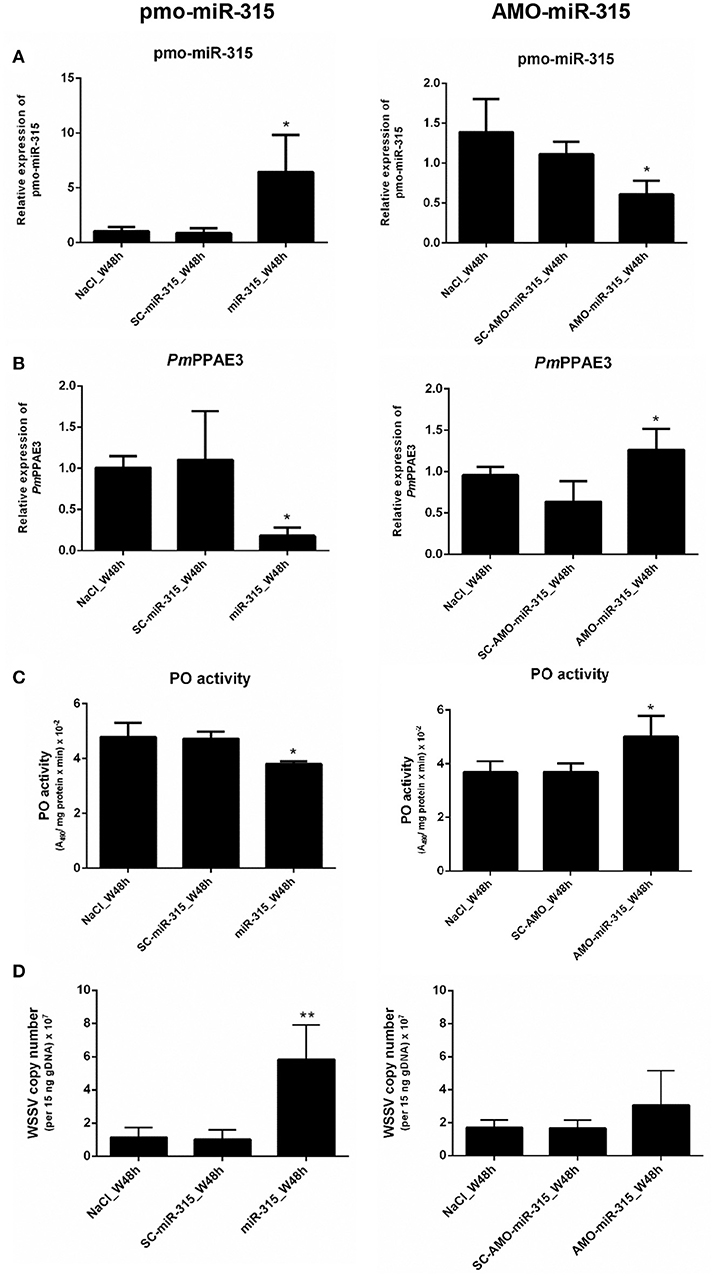

As stated in the previous experiment, suppression of PmPPAE3 gene expression resulted in a decrease in PO activity in shrimp hemolymph and the pmo-miR-315 could bind to specific site in the ORF of PmPPAE3 gene. In order to reveal the role of pmo-miR-315 in WSSV-infected shrimp, overexpression of pmo-miR-315 by introducing the exogenous pmo-miR-315 mimic and the silencing of pmo-miR-315 by anti-pmo-miR-315 injection (AMO-miR-315) were performed in shrimp after WSSV infection. The expression of pmo-miR-315 and its target gene, PmPPAE3, was analyzed to confirm the regulatory role of pmo-miR-315 on PmPPAE3 gene expression. As expected, the expression of PmPPAE3 was decreased whereas that of pmo-miR-315 was highly increased (Figures 5A,B).

Figure 5. The role of pmo-miR-315 in WSSV-infected shrimp hemocytes. In this experiment, either pmo-miR-315 mimic or AMO-miR-315 was injected into WSSV-infected shrimp. Then, several parameters were investigated including (A) pmo-miR-315 and (B) PmPPAE3 gene expression level, (C) PO activity and (D) WSSV copy number. The U6 and EF-1α were used as internal controls for pmo-miR-315 and PmPPAE3 expression, respectively. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The * and ** indicate the significant difference at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

The PO activity was also determined in shrimp hemolymph to further elucidate the involvement of pmo-miR-315 in modulating the proPO system. The mimic pmo-miR-315 injected into the WSSV-infected shrimp resulted in a deduction of PO activity (Figure 5C, Supplementary Table S1), indicating that the pmo-miR-315 negatively regulated the shrimp proPO system. The WSSV copy number was also analyzed in hemocytes to determine the effect of introducing the pmo-miR-315 on WSSV replication in shrimp. Interestingly, as compared with those of control groups of saline and scramble miR-315 injection, the WSSV copy number was significantly increased in WSSV-challenged shrimp if the mimic pmo-miR-315 was introduced (Figure 5D). Conversely, silencing of pmo-miR-315 in WSSV-infected shrimp caused an increase in PO activity because of the up-regulation of PmPPAE3 (Figure 5C, Supplementary Table S2). The inhibition of pmo-miR-315 activity by AMO-miR-315 slightly reduced the WSSV copy number when compared to that of pmo-miR-315 injection; however, it was still higher than the control groups (Figure 5D).

Discussion

In 2007, the miR-315 from Drosophila was found to act as a potent activator of Wingless (Wg) signaling, a conserved pathway that regulates growth and tissue specification (24). Previously, the miR-315s from M. japonicas, L. vannamei, P. monodon, and F. chinensis have been identified as a viral responsive miRNA in WSSV-infected shrimp hemocytes(5, 13, 14, 25, 26) suggesting that the shrimp miR-315 might be involved in antiviral immunity. Therefore, the pmo-miR-315 function was further characterized in this research.

The expression of pmo-miR-315 was detected in various shrimp tissues including hemocytes, gill, lymphoid organ, and stomach. Interestingly, the expression level of pmo-miR-315 in hemocytes was significantly up-regulated, more than 30 times at 48 h post-WSSV infection, implying the specific role of pmo-miR-315 in shrimp antiviral response in hemocytes. Although the target gene of pmo-miR-315 was predicted as putative prophenoloxidase-activating enzyme PmPPAE3 and serine/threonine protein kinase (13), in this research we focused on confirming the regulatory role of pmo-miR-315 on the expression of PmPPAE3.

Generally, the miRNA binds to the 3′-UTR of its target gene to regulate the translational repression and mRNA destabilization. Nevertheless, the binding site of miRNA can also be located at the 5′-UTR and coding sequence (CDS), albeit the regulatory activity may be different (27, 28). According to our prediction, the pmo-miR-315 can bind to CDS of PmPPAE3 gene (13). The luciferase reporter assay revealed that the pmo-miR-315 mimic could interact with the specific binding site on PmPPAE3 CDS, which was indicated by almost 36% reduction in luciferase activity.

Melanization activated by the prophenoloxidase (proPO) system is a principal innate immune response in shrimp. Upon pathogen invasion, the binding of Pattern Recognition Proteins (PRPs) to the microbial cell wall components activates the serine proteinase cascade that finally activates the final proteinases, called proPO-activating enzymes (PPAEs). The PPAEs, then, cleave the inactive proPOs to active POs leading to the initiation of melanin formation (29). In P. monodon, the active PmPPAE1 and PmPPAE2 cleaves PmproPO1 and PmproPO2 generating the active PO1 and PO2, respectively (30). The PmPPAE3 whose mRNA is the target of pmo-miR-315 is a novel isoform of PmPPAE characterized herein. It was mainly expressed in shrimp hemocytes and significantly suppressed after 24 and 48 h post-WSSV infection. As expected, the negative correlation of pmo-miR-315 expression and PmPPAE3 gene expression was observed in hemocytes after WSSV infection.

The full-length gene of PmPPAE3 was identified in this study and its deduced amino acid sequence was compared with other PmPPAEs from various species as well as the PmPPAE1 and PmPPAE2 (22, 23). The multiple alignment of different PPAE amino acid sequences revealed that the PmPPAE3 was closely related to FcPPAE, LvPPAE, and PmPPAE1. The phylogenetic analysis showed that the shrimp PPAEs and a crayfish PPAE belonged to the crustaceans cluster. Besides, the PmPPAE3 gene was hemocyte specific like PmPPAE1 and PmPPAE2. The function of PmPPAE3 in proPO system was confirmed using the RNA interference technique. Therefore, the PmPPAE3 was considered as a novel clips serine proteinase that function in the proPO system.

As mentioned above, the melanization reaction is activated through the proPO cascade after pathogen infection and unavoidably generates highly toxic molecules. These toxic intermediates are not only involved in pathogen killing but also cause the damage of the host cells (30, 31). Therefore, the activation cascade is needed to be tightly regulated. To date, several proteinase inhibitors of melanization cascade have been reported in shrimp, including the melanization inhibition protein (MIP), serine proteinase inhibitors (serpins), alpha-2-macroglobulin (A2M) and pacifastin (29). Furthermore, the small RNAs can also regulate the proPO system. The shrimp miR-100, which was up-regulated after WSSV or V. alginolyticus infection, can regulate several shrimp immune reactions including proPO activity, SOD activity and phagocytosis (32).

The involvement of proPO system upon WSSV infection has been reported. The PO activity is strongly decreased after WSSV-infection in shrimp (33). Later, it is found that the WSSV453 binds to and interferes with the proPmPPAE2 activation to active PmPPAE2 resulting in the suppression of shrimp melanization (18, 33). In our research, the role of pmo-miR-315 and PmPPAE3 in proPO system during WSSV infection in shrimp was explored. Injection of pmo-miR-315 mimic into the shrimp resulted in a reduction of PmPPAE3 gene expression and the PO activity as expected. On the other hand, inhibition of pmo-miR-315 by AMO-miR-315 increased the PmPPAE3 gene expression leading to the increase in PO activity in WSSV-infected shrimp hemocytes. Therefore, we can conclude that the pmo-miR-315 regulates the proPO system via PmPPAE3 post-transcriptional repression.

Upon WSSV infection, the shrimp proPO system takes part in shrimp antiviral immunity by producing melanin and cytotoxic intermediate for viral sequestration. However, the WSSV can overcome shrimp antiviral immunity partly by proPO system suppression. Several crustacean miRNAs have been reported to promote WSSV propagation. In M. rosenbergii, the host miR-s9041 and miR-9850 play positive roles in WSSV replication by targeting the STAT gene (10). In crabs, E. sinensis, the miR-217 leads to a decrease in the transcript level of Tube gene resulting in the enhancement of WSSV copies (34). Meanwhile, the survival rate of miR-100 silenced shrimp after WSSV infection is increased as the PO activity (32). According to our research, an increase in the viral copy number in WSSV-infected shrimp after pmo-miR-315 mimic injection indicated that the pmo-miR-315 functioned in enhancing viral replication by regulating the proPO system through the inhibition of PmPPAE3 gene expression. On the other hand, the viral copy number of AMO-miR-315 challenged shrimp was lower than that of WSSV-infected shrimp challenged with exogenous pmo-miR-315 but was not lower than the control groups as expected (Figure 5D). This might be because the pmo-miR-315 was not totally silenced. Since the whole genome sequence of P. monodon has not been reported yet, it was possible that the AMO-miR-315 could also target other unknown genes that might affect the WSSV propagation.

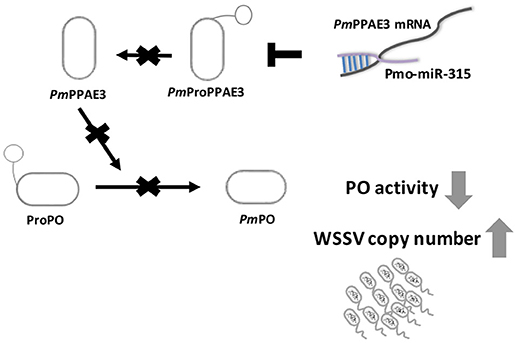

Taken together, our research offer a new mechanism on how WSSV inhibits proPO system by triggering host miRNA, as illustrated in Figure 6. The WSSV infection causes the pmo-miR-315 over-expression and subsequently inhibits the PmPPAE3 expression leading to a decrease in PO activity and increase in WSSV copy number in WSSV-infected shrimp hemocytes. Therefore, the pmo-miR-315 regulates the proPO system through the suppression of PPAE3 gene expression which leads to the promotion of viral propagation in shrimp hemocytes during WSSV infection.

Figure 6. A schematic representation of the pmo-miR-315 role in modulating proPO activity by PmPPE3 suppression during WSSV infection.

Author Contributions

KS participated in funding acquisition and supervision of this works. KS and PJ designed and provided the resources for the study. PJ performed in vivo experiments. PJ and CW performed in vitro experiments. All the authors analyzed, investigated the data and also wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund of Chulalongkorn University (CU-56-462-FW). Additional support from the Thailand Research Fund to KS (Grant No. RSA5980055) is acknowledged. Also, the scholarship to develop research potential for the Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University to CW and Postdoctoral Fellowship to PJ from Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund of Chulalongkorn University are greatly appreciated. We would like to thank the support to Omics Sciences and Bioinformatics Center under the Outstanding Research Performance Program: Chulalongkorn Academic Advancement into Its 2nd Century Project (CUAASC).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Dr. Vichien Rimphanitchayakit (from Chulalongkorn University) for commenting on the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02184/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell (2004) 116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5

2. Jopling CL, Yi M, Lancaster AM, Lemon SM, Sarnow P. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific microRNA. Science (2005) 309:1577–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1113329

3. Forman JJ, Coller HA. The code within the code: microRNAs target coding regions. Cell Cycle (2010) 9:1533–41. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.8.11202

4. Skalsky RL, Cullen BR. Viruses, microRNAs, and host interactions. Annu Rev Microbiol. (2010) 64:123–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134243

5. Huang T, Xu D, Zhang X. Characterization of host microRNAs that respond to DNA virus infection in a crustacean. BMC Genomics (2012) 13:159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-159

6. Yang L, Yang G, Zhang X. The miR-100-mediated pathway regulates apoptosis against virus infection in shrimp. Fish Shellfish Immunol. (2014) 40:146–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.06.019

7. Gong Y, Ju C, Zhang X. The miR-1000-p53 pathway regulates apoptosis and virus infection in shrimp. Fish Shellfish Immunol. (2015) 46:516–22. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.07.022

8. Shu L, Li C, Zhang X. The role of shrimp miR-965 in virus infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. (2016) 54:427–34. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.04.129

9. Xu X, Yuan J, Yang L, Weng S, He J, Zuo H. The dorsal/miR-1959/cactus feedback loop facilitates the infection of WSSV in Litopenaeus vannamei. Fish Shellfish Immunol. (2016) 56:397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.07.039

10. Huang Y, Wang W, Ren Q. Two host microRNAs influence WSSV replication via STAT gene regulation. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:23643. doi: 10.1038/srep23643

11. He Y, Yang K, Zhang X. Viral microRNAs targeting virus genes promote virus infection in shrimp in vivo. J Virol. (2014) 88:1104–12. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02455-13

12. Huang T, Cui Y, Zhang X. Involvement of viral microRNA in the regulation of antiviral apoptosis in shrimp. J Virol. (2014) 88:2544–54. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03575-13

13. Kaewkascholkul N, Somboonviwat K, Asakawa S, Hirono I, Tassanakajon A, Somboonwiwat K. Shrimp miRNAs regulate innate immune response against white spot syndrome virus infection. Dev Comp Immunol. (2016) 60:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2016.03.002

14. Li X, Meng X, Luo K, Luan S, Shi X, Cao B, et al. The identification of microRNAs involved in the response of Chinese shrimp Fenneropenaeus chinensis to white spot syndrome virus infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. (2017) 68:220–31. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2017.05.060

15. Xie X, Li H, Xu L, Yang F. A simple and efficient method for purification of intact white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) viral particles. Virus Res. (2005) 108:63–7. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.08.002

16. Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. (2001) 29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45

17. Mendoza-Cano F, Sánchez-Paz A. Development and validation of a quantitative real-time polymerase chain assay for universal detection of the white spot syndrome virus in marine crustaceans. Virol J. (2013) 10:186. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-186.

18. Sutthangkul J, Amparyup P, Eum J-H, Strand MR, Tassanakajon A. Anti- melanization mechanism of the white spot syndrome viral protein, WSSV453, via interaction with shrimp proPO-activating enzyme, PmproPPAE2. J Gen Virol. (2017) 98:769–78. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000729

19. Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. (1976) 72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3

20. Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. (2016) 33:1870–4. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054

21. Cerenius L, Söderhäll K. The prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrates. Immunol Rev. (2004) 198:116–26. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00116.x

22. Charoensapsri W, Amparyup P, Hirono I, Aoki T, Tassanakajon A. Gene silencing of a prophenoloxidase activating enzyme in the shrimp, Penaeus monodon, increases susceptibility to Vibrio harveyi infection. Dev Comp Immunol. (2009) 33:811–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2009.01.006

23. Charoensapsri W, Amparyup P, Hirono I, Aoki T, Tassanakajon A. PmPPAE2, a new class of crustacean prophenoloxidase (proPO)-activating enzyme and its role in PO activation. Dev Comp Immunol. (2011) 35:115–24. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2010.09.002

24. Silver SJ, Hagen JW, Okamura K, Perrimon N, Lai EC. Functional screening identifies miR-315 as a potent activator of Wingless signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2007) 104:18151–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706673104

25. Zeng D, Chen X, Xie D, Zhao Y, Yang Q, Wang H, et al. Identification of highly expressed host microRNAs that respond to white spot syndrome virus infection in the Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei (Penaeidae). Genet Mol Res. (2015) 14:4818–28. doi: 10.4238/2015

26. Sun X, Liu Q-h, Yang B, Huang J. Differential expression of microRNAs of Litopenaeus vannamei in response to different virulence WSSV infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. (2016) 58:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.08.062

27. Hausser J, Syed AP, Bilen B, Zavolan M. Analysis of CDS-located miRNA target sites suggests that they can effectively inhibit translation. Genome Res. (2013) 23:604–15. doi: 10.1101/gr.139758.112

28. Brümmer A, Hausser J. MicroRNA binding sites in the coding region of mRNAs: extending the repertoire of post-transcriptional gene regulation. Bioessays (2014) 36:617–26. doi: 10.1002/bies.201300104

29. Tassanakajon A, Rimphanitchayakit V, Visetnan S, Amparyup P, Somboonwiwat K, Charoensapsri W, et al. Shrimp humoral responses against pathogens: antimicrobial peptides and melanization. Dev Comp Immunol. (2018) 80:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.05.009

30. Amparyup P, Charoensapsri W, Tassanakajon A. Prophenoloxidase system and its role in shrimp immune responses against major pathogens. Fish Shellfish Immunol. (2013) 34:990–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2012.08.019

31. Charoensapsri W, Amparyup P, Suriyachan C, Tassanakajon A. Melanization reaction products of shrimp display antimicrobial properties against their major bacterial and fungal pathogens. Dev Comp Immunol. (2014) 47:150–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2014.07.010.

32. Wang Z, Zhu F. MicroRNA-100 is involved in shrimp immune response to white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) and Vibrio alginolyticus infection. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:42334. doi: 10.1038/srep42334

33. Sutthangkul J, Amparyup P, Charoensapsri W, Senapin S, Phiwsaiya K, Tassanakajon A. Suppression of shrimp melanization during white spot syndrome virus infection. J Biol Chem. (2015) 290:6470–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.605568

Keywords: microRNA, viral infection, invertebrates, Penaeus monodon, prophenoloxidase

Citation: Jaree P, Wongdontri C and Somboonwiwat K (2018) White Spot Syndrome Virus-Induced Shrimp miR-315 Attenuates Prophenoloxidase Activation via PPAE3 Gene Suppression. Front. Immunol. 9:2184. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02184

Received: 07 June 2018; Accepted: 04 September 2018;

Published: 25 September 2018.

Edited by:

Chu-Fang Lo, National Cheng Kung University, TaiwanReviewed by:

Arun K. Dhar, University of Arizona, United StatesChia-Ying Chu, National Taiwan University, Taiwan

Copyright © 2018 Jaree, Wongdontri and Somboonwiwat. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kunlaya Somboonwiwat, a3VubGF5YS5zQGNodWxhLmFjLnRo

†Present Address: Phattarunda Jaree, Institue of Molecular Biosciences, Mahidol University, Salaya, Thailand

Phattarunda Jaree

Phattarunda Jaree Chantaka Wongdontri

Chantaka Wongdontri Kunlaya Somboonwiwat

Kunlaya Somboonwiwat