- 1Department of Life Sciences, University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy

- 2Immunorheumatology Research Laboratory, Istituto Auxologico Italiano, IRCCS, Milan, Italy

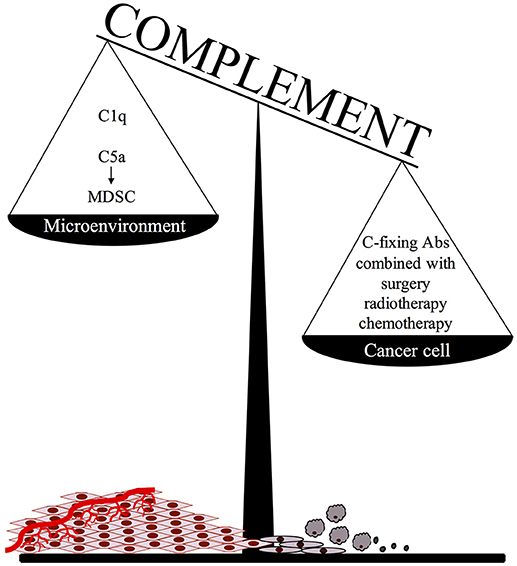

Deposits of complement components have been documented in several human tumors suggesting a potential involvement of the complement system in tumor immune surveillance. In vitro and in vivo studies have revealed a double role played by this system in tumor progression. Complement activation in the cancer microenvironment has been shown to promote cancer growth through the release of the chemotactic peptide C5a recruiting myeloid suppressor cells. There is also evidence that tumor progression can be controlled by complement activated on the surface of cancer cells through one of the three pathways of complement activation. The aim of this review is to discuss the protective role of complement in cancer with special focus on the beneficial effect of complement-fixing antibodies that are efficient activators of the classical pathway and contribute to inhibit tumor expansion as a result of MAC-mediated cancer cell killing and complement-mediated inflammatory process. Cancer cells are heterogeneous in their susceptibility to complement-induced killing that generally depends on stable and relatively high expression of the antigen and the ability of therapeutic antibodies to activate complement. A new generation of monoclonal antibodies are being developed with structural modification leading to hexamer formation and enhanced complement activation. An important progress in cancer immunotherapy has been made with the generation of bispecific antibodies targeting tumor antigens and able to neutralize complement regulators overexpressed on cancer cells. A great effort is being devoted to implementing combined therapy of traditional approaches based on surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy and complement-fixing therapeutic antibodies. An effective control of tumor growth by complement is likely to be obtained on residual cancer cells following conventional therapy to reduce the tumor mass, prevent recurrences and avoid disabilities.

Introduction

Cancer development is a complex biological process that starts with the malignant transformation of normal cells caused by genetic alterations and somatic mutations leading to unrestricted cell proliferation (1). The local microenvironment plays an important role in this process providing favorable conditions for the seeding of cancer cells in a protective niche that allows the growth and expansion of the tumor mass (2). Changes in the structural and organizational properties of extracellular matrix favor adhesion and migration of cancer cells from the initial tumor site (3). Active angiogenesis equally contributes to these environmental changes with the formation of new leaky vessels that supply growing cancer cells with nutrients and promote their metastatic spread to distant organs (4, 5).

Tumor development is constantly controlled by the immune system that recognizes cancer cells as potential threats to body homeostasis and mounts a response leading to local recruitment of effector cells of both innate and adaptive immunity (6). Although cell-mediated immunity has long been recognized to play a critical role in tumor eradication through the action of natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (7, 8), studies reported in recent years have shown that the complement (C) system is also an important player in cancer immune surveillance and these studies have revealed the complex interaction of C with cancer cells. C components are synthesized by resident and recruited cells including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, tissue specific cells, and macrophages (9, 10) and are released in the tumor microenvironment. Biologically active products generated as a result of C activation may directly kill cancer cells or favor their eradication by promoting an inflammatory process. However, it is important to emphasize that C does not always provide an effective protection against tumor growth since its damaging effect on cancer cells can be prevented by C regulatory proteins (CRPs) over-expressed on the cell surface or by other mechanisms of cell resistance to C attack. These evasion strategies are more likely to be operating under conditions of fast tumor growth.

Recent studies have elucidated a novel aspect of C interaction with cancer cells showing that it is able to promote rather than to inhibit tumor development. Markiewski et al. (11) made the original observation that C5a, released in the microenvironment as a result of C activation, recruits and activates myeloid derived suppressor cells that suppress anti-tumor T-cell responses against HPV-induced cancer. Similar findings have been reported in other syngeneic models of mouse tumors invariably associated with C activation (12, 13). Importantly, C5aR1-deficiency and pharmacological blockade of C5aR1 by selective C5aR1 antagonists have been shown to impair tumor growth, pointing to the C5a/C5aR1 signaling axis as an effector mechanism of C-mediated tumor-promoting functions (14).

More recently, C1q secreted in the tumor microenvironment was reported to favor tumor progression by enhancing adhesion, proliferation, and migration of cancer cells and promoting angiogenesis independently on C activation (15).

Given these restraints in C-dependent tumor control, the system has apparently limited chances to provide an effective defense barrier against cancer development unless the C protective functions are made more efficient by optimizing the conditions of its activation and effector activities. In this review, we shall discuss the strategies that may turn the C system into a more efficient therapeutic tool by enhancing its activation on the surface of cancer cells and overwhelming the mechanisms adopted by tumor cells to evade C attack.

Complement Activation at Tumor Site

Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor tissue has provided useful information on the contribution of the C system to the immune response to cancer revealing the presence of C components in several solid tumors of different tissues and organs. Various cell types in tumor tissue including cancer cells represent the main source of these components which may also derive, at least in part, from the circulation as a result of the increased permeability of the tumor vessels. C deposits have been observed in a number of tumors (16) and in one study that examined the deposition of various C components in glioblastoma, C1q was found to be the most highly expressed component (17). We have recently shown that C1q is present in various tumors in the absence of other C components and exerts functions unrelated to C activation (15). However, this does not exclude C activation at tumor sites as suggested by tissue deposition of known markers of C activation including C4d, C3d, and SC5b-9 (18, 19). Local changes in tumor tissue due to necrosis and apoptosis and, more importantly, inflammation are responsible for C activation to a degree related to the extent of these changes, in particular of the inflammatory process. This suggests that C deposits are likely to be negligible in the initial stages of tumor growth when the inflammatory reaction is hardly detectable and is probably more evident at a later stage of tumor expansion associated with an overt inflammatory reaction. Tumor cells may partly contribute to C activation using cell-bound proteases exposed on their surface to cleave C5 and to generate C5a, which in turn enhances cancer cell invasion (20).

It is not easy to evaluate the impact of C activation at tissue sites on tumor development because the immunohistochemical data have mostly been obtained from well-established cancers. Importantly, C activation products are mainly localized in the tumor microenvironment and found to be weakly or moderately bound to some but not all cancer cells, suggesting that they have limited effect in reducing cell survival. However, it is possible that C exerts a protective effect in the early phase of cancer growth, contributing to induce tumor regression, although this is difficult to ascertain in patients. One way to address this issue is to utilize mice that develop spontaneous tumors and analyze the effect of C activation on its progression at tumor sites. Using BALB/c females expressing the activated rat Her2/neu oncogene, Bandini et al. (21) have shown that the mammary carcinoma developing in C3−/− mice manifests faster growth rate and earlier lung metastasis than the tumor in wild type animals, suggesting that C activated by antibodies (Abs) directed against Her2/neu oncogene and/or other tumor-associated antigens may control tumor growth. Different results were obtained using a syngeneic mouse model of ovarian cancer which showed similar growth in wild type and C3−/− mice due to secretion of C3 by tumor cells that exerts a stimulating effect on cell proliferation (22). Overall, the available data support a dual role of C in tumor immune surveillance and its ability to either prevent or promote tumor progression depends on the characteristics of cancer cells and the anti-tumor efficiency of the C system.

Cancer Cells as Potential Target of Complement Attack

Expression of tumor-associated molecules on cells undergoing malignant transformation can lead to C activation on the cell surface by all three activation pathways. The lectin pathway has been implicated in C activation on glioma cells which express, like many other malignant cells, high mannose glycopeptides that bind MBL and trigger consumption of C4 and C3, but this reaction fails to induce cell lysis (23). Virus transformed cells express novel antigens that are able to activate the alternative pathway, as is the case of EBV-infected B lymphoblastic cell lines (24–26) and T and monocytic cell lines infected by HIV (27). The classical pathway of C can be activated on cancer cells by natural Abs, preferentially of IgM isotype, that recognize carbohydrate moieties on cell surfaces (28, 29). Cytotoxic Abs reacting with carbohydrate epitopes of gangliosides GD2 and GD3 on neuroblastoma and melanoma cell lines have been detected in a small number of sera from normal individuals (30). Unfortunately, besides the low frequency, the natural Abs are not efficient in promoting C-mediated cell killing due to their low titer and affinity.

Attempts have been made to vaccinate cancer patients with the aim to induce production of therapeutic Abs. The anti-tumor response has not always been satisfactory, although a novel vaccination procedure has recently been developed in rabbits to stimulate the generation of IgG Abs that cause strong C-mediated lysis of myeloma cells carrying the CD38 antigen (31).

Despite this improvement, the development of recombinant Abs against tumor antigens remains the preferential approach to stimulate selective C activation on cancer cells, although the identification of specific tumor-associated antigens able to discriminate cancer cells from healthy tissue still represents a major limitation in Ab-mediated cancer therapy. A major progress has been made in the immunotherapy of hematologic malignancies, in particular those derived from B cells, with the generation of monoclonal Abs directed against target antigens, such as CD19 and CD20, present only on B-cells at late stages of development, and not on hematopoietic stem cells that are therefore unaffected by the treatment. Conversely, the development of therapeutic Abs against solid tumors has been limited by the difficulty to identify specific target antigens on cancer cells, whether overexpressed self-antigens, or neoantigens due to tumor-specific mutations or oncogenic viruses.

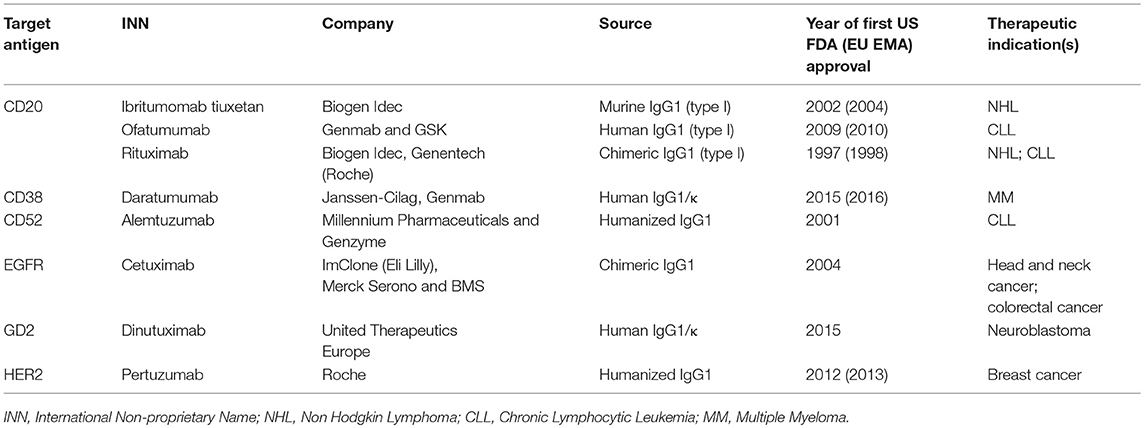

Only 15 monoclonal Abs have been approved by FDA for the treatment of all different solid tumors (32), and only 3 of them are C-fixing molecules, as described in Table 1.

Factors Affecting the Efficiency of the Antibodies to Activate Complement: The Antibodies Structure

Among the molecular characteristics of recombinant Abs responsible for C activation, the Ig class is critically important since human IgM, IgG1, and IgG3 are known to be the most effective C activators whereas IgG4 fails to bind C1q (33). The structure of the Fc region of these Abs has been extensively investigated to improve their therapeutic efficiency and changes of some amino acids in this region were found to enhance the Ab activity (34). In particular, computational design followed by high-throughput screening techniques has allowed the identification, production, and characterization of Fc variants with increased ability to bind C1q and to promote C-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) (35).

Glycosylation is an important secondary modification of immunoglobulins that has a significant impact on their capacity to activate different arms of the immune system. The addition of conserved glycans, in particular α (1,6)-linked core fucose, to the Fc region, was shown to be critical for the interaction of the Ab with the C system (36). This observation has raised strong research interest in several biotech companies, resulting in the commercialization of the anti-CD20 Ab obinutuzumab (Genentech, San Francisco, CA, USA). Terminal mannosylation is another important post-translational modification that prolongs the half-life of the Abs in the circulation and favors binding of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) (36). Importantly, the terminal glycosylation of IgG has been shown to influence CDC without affecting Ab-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC). In addition, an increased content of terminal galactose potentiates CDC activity by enhancing the binding of C1q to the modified Ab (37).

The discovery that hexamerization of Abs after binding to target antigens leads to a successful activation of the classical pathway represents a major advance in the development of new strategies to enhance C activation by IgG (38, 39). The critical role of this process in C activation is supported by the finding that some mutations of Fc amino acid sequence of anti-CD20 IgG result in impaired hexamer formation and reduced cell lysis. Conversely, other mutations have the opposite effect and similar results were obtained introducing the same mutations in the IgG4 isotype. A certain degree of flexibility of antigen-bound Abs allows a conformational change required for hexamerization. The ability of anti-CD20 Abs to exhibit a more efficient CDC after hexamer formation is shared also by anti-CD52 and anti-HLA Abs (38, 39).

Factors Affecting the Efficiency of the Antibodies to Activate Complement: The Antigen

Irrespective of the C-activating capacity of anti-tumor Abs, the characteristics of the target antigen remain of pivotal importance for a successful tumor cell lysis. The beneficial effects of Abs in cancer immunotherapy depend on the expression pattern and the tissue specificity of tumor antigen that should be present exclusively or predominantly on cancer cells to allow selective or almost exclusive targeting of tumor cells. It is equally important that the tumor antigens are expressed also on metastatic cells which represent the main target of Ab-based immunotherapy since other therapeutic approaches including surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy can be used to obtain an effective control of primary tumor. Moreover, the tumor antigens should be stably expressed on the cell surface to serve as useful targets for immunotherapy, whereas intracellular antigens, though specific for tumor cells, can only be used for diagnostic purposes. It is important to point out that tumor cells are often heterogeneous in the expression level of tumor antigens that may influence their susceptibility to CDC. We have observed that cells expressing low levels of CD20 isolated by cell sorting from a population of either chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or cancer B-cell lines and kept in culture for over a week give rise to cells expressing higher level of CD20 that more easily undergo C-mediated lysis (40, 41). This observation suggests that repeated injections of Abs administered at appropriate time intervals can be used to allow the emergence of cell clones expressing higher levels of CD20 and more susceptible to CDC. Finally, the release of antigen in the tumor microenvironment and in the circulation may lead to blockade of therapeutic Ab and contributes to reduce its expression level on the cell surface, making cancer cells less susceptible to Ab-mediated C-dependent killing (9).

The number of antigenic sites does not always account for the capacity of a monoclonal Ab to cause CDC. In this regard, the impact of the different distribution of two tumor antigens, the alpha isoform of folate receptor (42) and CD20 (43), on Ab binding and C activation has been compared. The folate receptor is associated with epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells and is expressed on several cell lines at a concentration of about 1 × 106 molecules/cells (44). CD20 is present on cancer B-cells at a substantially lower expression level of around 40,000–70,000 molecules/cell (45). Despite the marked difference in the number of cell-associated antigenic sites, the chimeric anti-CD20 Rituximab is able to activate C (46) and to kill B cells whereas a chimeric anti-folate receptor Ab fails to do so (42).

Additional factors may play a relevant role in promoting a more efficient C activation by recombinant Abs, including the proximity of the target epitopes to the cell surface (47), the density of target antigen (48), and the Ab-induced movement of the antigens across the cell membrane (49).

A recent study by Cleary and colleagues provided convincing evidences that the efficacy of C-mediated killing of cancer cells induced by Ab is largely influenced by the distance of the target epitope from the cell membrane and the greater the distance from the cell surface, the lower the efficiency of cell lysis (47). They used target cells transfected with fusion proteins containing either CD20 or CD52 epitopes attached to various CD137 scaffolds and showed that the cells displaying the target epitopes closer to the membrane were more susceptible to CDC than those expressing the epitopes furthest away from the cell surface. These data clearly suggest that the position of the epitope in the target antigen is an important factor to consider in the selection of therapeutic Abs. The surface expression level of the antigen has been shown to be equally important for an efficient C activation on both hematological and solid tumors. Golay et al. (45) analyzed freshly isolated cells from patients with B-CLL and prolymphocytic leukemia for CDC induced by Rituximab and found that the C sensitivity of these cells correlated with the surface expression of CD20. Derer et al. (48) reached similar conclusions using a fibroblast cell line expressing different levels of Epithelial Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) and reported data indicating that the cell susceptibility to CDC progressively increased at higher expression level of EGFR. An increased antigen density resulting from Ab-induced movement of the tumor-associated antigen across the cell membrane can also contribute to enhance Ab-dependent C activation. CD20 is an example of a membrane antigen, that is induced by the type 1 Abs rituximab and ofatumumab to translocate to the lipid rafts (49). As a consequence, the immune complexes reach a critical concentration required for hexamer formation and C1q binding (50).

Factors Affecting the Efficiency of the Antibodies to Activate Complement: The Complement System

C is an important player in Ab-induced tumor cell death and has therefore a major impact on the efficacy of therapeutic Abs. A clinical observation in patients with CLL treated with Abs is that the depletion of cancer and normal cells in the blood of patients is impaired in the presence of reduced levels of C components (51). Clearance of CLL cells induced by Abs to CD20 has been shown to be associated with C consumption, particularly of the early components, which persist for several days to weeks (52). This would cause a reduced therapeutic effect of subsequent infusions of the same Abs to control the malignant cells that circulate in blood in increasing number due to migration from bone marrow or lymph node. Using an in vitro model to evaluate the CDC of Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines induced by ofatumumab and rituximab, Beurskens et al. (51) have investigated the effect of different concentrations of anti-CD20 Abs on cell killing in two consecutive steps. They found that the dose of anti-CD20 Abs tested in the first step was critical for the degree of cell killing in the second step. In particular, using the maximal dose of anti-CD20 Abs in the first step, the cell lysis did not exceed 30% in the second step, while the percentage of cell killing increased to over 80% using a lower Ab concentration in the first step. These data suggest that the best therapeutic option would be to use the minimal concentration of Ab to trigger C-mediated killing of a relatively high number of cells leaving a C level sufficient to clear newly emerging malignant cells treated with an additional administration of Ab.

The critical role of C in CDC induced by recombinant Abs is supported by other uncontrolled studies suggesting that the killing of cancer B cells could be enhanced based on supplementation with purified C components or fresh frozen plasma (53, 54).

The response to immunotherapy of tumors that develop extravascularly is likely to be different from that of circulating cells. Unfortunately, it is difficult to evaluate the concentration of the Ab at cancer site, nor is it easy to measure the activity of the C system in the tumor microenvironment. However, the amount of Abs that reaches tumor sites (55) should be sufficient to activate C if the Abs tend to form hexamers that require limited amount of C components to activate the system (39).

Evidence supporting local C deposition was obtained by our group using a mouse xenograft model of B-cell lymphoma established in SCID mice with the intraperitoneal injection of a lymphoma cell line (56). This model is characterized by the development of peritoneal tumor masses and formation of foci of lymphoid cells in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow. Injection of rituximab into tumor-bearing mice resulted in the deposition of the Ab, C3, and C9 on tumor cells and in prolonged survival of these animals.

Complement-Mediated Cancer Cell Damage and Regulation

The importance of late C components in tumor development has recently been investigated by Verma et al. (57) in a xenogenic mouse model of B-cell lymphoma. They showed that tumor-bearing C5 deficient animals treated with rituximab died within the 52 days period of observation whereas all C5 sufficient mice survived. Although the tumor tissue was not examined for complement deposition, the membrane attack complex (MAC) is likely to have contributed to the C protective effect in this model.

MAC assembly on the cell membrane is the final step of C activation. Tumor cell killing caused by Ab-mediated C activation takes a few minutes to complete under standard in vitro conditions (52) and is largely mediated by increased Ca2+ influx and rapid activation of a large variety of enzymes as a result of MAC insertion (58, 59). C5a and other C activation products can also contribute to tumor control by recruiting to the tumor microenvironment inflammatory cells that cause cell death via C-dependent cell cytotoxicity and phagocytosis (60).

A large body of evidence has been collected showing that cancer cells can resist CDC by several different mechanisms acting either on the cell surface or intracellularly.

Removal of MAC from the cell surface is one of these mechanisms observed in different tumor cell types after the activation of the C system by mAbs (61–64). This removal is usually mediated through membrane vesiculation, directed both to the inner and the outer sides of cell surface (65).

Overexpression of the membrane-associated C regulatory proteins (mCRPs) CD46, CD55, and CD59 is another mechanism by which cancer cells can evade undesired C attack due to spontaneous or Ab-induced C activation. The mCRPs act at different steps of the C sequence by favoring the decay of the C3 convertases (CD55), promoting the degradation of C3b and C4b (CD46), and preventing the assembly of MAC (CD59) (66, 67). Because of their high expression level on several tumors, mCRPs are considered promising targets for cancer immunotherapy. CD46 has been shown to be highly expressed on colorectal, breast (68), prostate, lung, liver, and ovarian carcinoma (69) cancer cells. Elevated levels of CD55 have been documented in a wide range of cancers including lung, colorectal, gastric, breast, and cervical cancers as well as in leukemia (66). CD59 is also overexpressed on different types of carcinoma and sarcoma and on melanoma cells (70).

An important point to emphasize is that hyper-expression of mCRPs on the surface of tumor cells does not necessarily mean that they are equally involved in cell protection from C attack. Almost two decades ago, we analyzed various B-lymphoma cell lines for their susceptibility to CDC and found that all expressed increased levels of CD55, CD46, and CD59 and were variably resistant to C lysis (46). However, using neutralizing Abs to mCRPs, we were able to show that the resistance to C-dependent cell lysis was abrogated by blocking the inhibitory activity of CD55 and CD59 whereas inhibition of CD46 was totally ineffective (46). In contrast, CD46 appears to play a more prominent role in protecting ovarian cell lines from C attack as suggested from the substantial increase in C-mediated cell lysis observed inhibiting CD46 activity with anti-CD46 neutralizing Abs (42). These findings have important clinical implication for the selection of mCRP to inhibit in the immunotherapy of different tumors.

Therapeutic Strategies

Antibodies and Complement Activation

Over the past 20 years, therapeutic Abs have rapidly become the leading product in the biopharmaceutical market. Currently, there are more than 30 FDA-approved therapeutic Abs for cancer treatment and some of them are C-fixing Abs that mediate CDC (Table 1).

Rituximab was the first C-fixing Ab to receive FDA approval and has been used successfully to treat a large number of patients with CD20-expressing B-cell malignancies. Because CD20 is expressed on several B cell-derived cancer cells and also on normal cells from the late pro-B cell through memory cells, while absent on plasma cells and precursors hematopoietic stem cells, it is understandable why treatment with anti-CD20 Abs induces depletion of cancer cells but does not interfere with the repopulation of the B-cell compartment (71). Analysis of the binding mode of anti-CD20 Abs and their epitope specificity has led to the identification of two types of Abs that differ in their ability to form distinct complexes with CD20. Type I Abs stabilize CD20 in lipid rafts leading to stronger C1q binding and increased C activation whereas type II Abs exhibit reduced C1q binding that results in lower levels of cell death mediated by CDC (72).

Rituximab, ofatumumab and ibritumomab tiuxetan are examples of type I Abs known to be efficient activator of the C cascade (71). On the contrary, type II Abs like tositumumab performed poorly in CDC (49) and the same was observed for the optimized type II Ab obinutuzumab which fails to induce CDC (72, 73). However, Bologna et al. have reported that C plays a role in cell killing induced by high dose of the type II glycoengineered anti-CD20 mAb obinutuzumab on B-CLL expressing high levels of CD20, as suggested by the ability of the anti-C5 Ab eculizumab to totally prevent cell lysis (74).

In addition to anti-CD20 Abs, other approved C-fixing Abs directed against various tumor antigens have been recognized to activate C both in vitro and in vivo including anti-CD52 alemtuzumab (75), anti-CD38 daratumumab (76, 77), anti-EGFR cetuximab (78, 79), anti-GD2 dinutuximab (80) and anti-HER2 pertuzumab (81).

Strategies to Improve Complement Activation by Therapeutic Antibodies

Combination of Different Antibodies

The efficiency of C activation on the cell surface is largely influenced by the epitope density of the antigen recognized by recombinant Abs which can affect the formation of an adequate number of immune complexes capable of binding C1q. Two different strategies have been reported to increase the formation of C1q-fixing dimers. One approach is to use a combination of two Abs recognizing different epitopes on the same antigen sufficiently close to allow juxtaposition of the IgG Abs which is critical for C1q binding. Spiridon et al. (82) were the first to analyze C-mediated lysis of Her-2+ human breast cancer cell lines induced by several mAbs and showed an enhanced killing using a mixture rather than individual mAbs. Our group has investigated the C-fixing ability of two Abs, cMOV18, and cMOV19, that bind to distinct epitopes of the alpha isoform of folate receptor, highly expressed on epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Interestingly, the mixture of these two Abs was able to activate C and to cause death of ovarian cancer cells while individual Abs were totally ineffective (42). A similar pattern of C activation was obtained using combination of the anti-EGFR Abs cetuximab and matuzumab, which recognize different nonoverlapping epitopes of EGFR (79). Cetuximab was reported to induce some degree of CDC in lung cancer cell lines only at high concentrations (40 μg/mL) (79), whereas lower amount (10 μg/mL) of either cetuximab or matuzumab failed to trigger C activation. Interestingly, the mixture of the two Abs was able to induce C1q and C4c fixation leading to strong activation of CDC (50 and 80% of lysis of squamous cell carcinoma and glioblastoma cells, respectively) (78).

Although this approach has not yet been introduced in clinical practice, it represents a promising future development in immunotherapy with C-fixing Abs.

Neutralization of Membrane Complement Regulatory Proteins

Different approaches based on anti-mCRP Abs or silencing mCRP expression in combination with therapeutic Abs have been evaluated in vitro and in vivo by various groups to prevent the C-inhibitory effect of mCRP. We initially reported an increased susceptibility of follicular and Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines to CDC induced by Rituximab in the presence of Abs to CD55 and CD59 (46). These findings were later confirmed using an in vivo model of human CD20+ B-lymphoma established in severe combined immunodeficient mice treated with rituximab in combination with anti-CD55 and anti-CD59 Abs that resulted in a significant animal survival (56). Similar enhancing effect of anti-CD55 and anti-CD59 Abs was reported on C-mediated killing of two human lung carcinoma cell lines induced by Herceptin (trastuzumab) (83). Neutralizing Abs to CD46 and CD59 were instead required to enhance CDC of ovarian carcinoma cells induced by the mixture of cMOV18 and cMOV19 (42). Down-regulation of all three mCRPs obtained with cationic liposomes (AtuPLEXes) loaded with siRNAs proved effective in inducing substantial increase of CDC of HER2 positive breast, lung and ovarian adenocarcinoma cell lines stimulated by trastuzumab and pertuzumab (84).

Although lysis of C-resistant tumor cells can be restored by the addition of Abs neutralizing mCRPs, their use is limited by the ubiquitous expression of mCRPs on both normal and tumor cells. One way to avoid undesired side effects that may derived from the binding of Abs to normal cells resulting in decreased expression of mCRPs is to selectively deliver the Abs to tumor cells. To this end, our group has generated two bispecific Abs containing binding specificity to CD20 and either CD55 or CD59. These Abs were able to recognize CD20 expressed on Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines and to neutralize membrane-bound CD55 and CD59 enhancing cell susceptibility to C-mediated lysis. An in vivo model of Burkitt's lymphoma developed in SCID mice was used to investigate the tissue distribution of bispecific Abs that were found to target selectively the tumor mass due to the high affinity of the anti-CD20 portion as opposed to the lower affinity of the anti-CD55 or anti-CD59 arms and to prevent tumor development (60). The therapeutic effect of the Abs was largely dependent on C activation, as revealed by the increased deposition of C3 and C9 in tumor masses, and also by local recruitment of macrophages and NK cells. Importantly, the combination of these two bispecific Abs resulted in the survival of 100% of treated mice whereas treatment with a single bispecific recombinant Ab (MB20/55 or MB20/59) induced the survival of only 20% of animals (60).

An interesting approach aimed at inhibiting mortalin, an heat shock protein over-expressed in many cancer types, has been proposed by Fishelson and his group (85) to interfere with MAC formation and its release from cell surface. The level of mortalin is inversely related to MAC deposition and its over-expression in erythroleukemic cells protects from C activation through the classical pathway, while protein down-regulation using specific siRNA increases the level of cell-bound C9.

Complement Activation Potentiates Standard Therapies

Complement and Radiotherapy

Together with surgery and chemotherapy, radiotherapy is a clinical mainstay of treatment for many malignancies especially for aggressive tumors with poor prognosis.

Recent studies support an association between radiation therapy for both human and murine cancers and C activation. An elegant study by Surace et al. (86) showed that local irradiation of melanoma and colon carcinoma developing in mice with a single dose of 20 or 5 Gy resulted in rapid and transient C activation triggered by tumor cells undergoing necrosis, apoptosis, and mitotic catastrophe with the possible contribution of natural IgM Abs bound to necrotic cells. In addition, they documented tumor deposition of C3 activation products and local increases in C3a and C5a, which induce maturation and activation of tumor-associated dendritic cells expressing the receptors for these anaphylatoxins and in turn promoting the anti-tumor activity of CD8+ T lymphocytes. The important role of C activation in the control of tumor growth was supported by the finding that radiotherapy failed to exert a protective effect against the tumor in mice deficient in either C3, or in C3a or C5a receptors, suggesting the critical contribution of locally released C3a and C5a.

Somewhat different results were obtained by Elvington et al. (87) who used a lymphoma model in mice receiving low dose radiotherapy fractionated over a period of approximately 5 months. They found that C inhibition induced by the administration of CR2-Crry resulted in longer survival and reduced tumor mass in tumor-bearing mice. A possible explanation for these contrasting results is that a radiation treatment administered over a prolonged period of time induces a C-independent inflammatory response that contributes to promote tumor growth. Overall, these data indicate that dose and fractionation in the radiation therapy need to be further investigated to find optimal conditions that combine the beneficial anti-tumor effects of radiotherapy and C activation.

Complement and Chemotherapy

Limited information is available on the interplay between the C system and chemotherapeutic agents and the effect of this interaction on tumor control.

Levels of C3 and C4 were measured in patients with breast cancer treated with epirubicin/docetaxel-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy and found to be substantially reduced (88). This finding cannot be explained by C consumption because the low concentrations of C3 and C4 were not associated with a parallel increase in the level of the C activation product C4d. The relevance of this observation is unclear since the levels were equally reduced in responders and non-responders to chemotherapy. A similar conclusion was reached in another study that examined the changes in C activity in patients with various types of cancer and revealed a significant reduction in C activity which was not accompanied by a corresponding increase in the level of C3d (89). More direct evidence supporting the beneficial effect of a combination therapy with a chemotherapeutic agent and a recombinant Ab was obtained from a multicenter clinical trial conducted in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (90). The patients receiving the monoclonal Ab cetuximab directed against epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in combination with cisplatin/vinorelbine survived longer than those treated with the chemotherapeutic agents alone. In a subsequent study, cetuximab was found to bind to a lung cancer cell line expressing EGFR and to activate C resulting in the assembly of the membrane attack complex and cell death. C involvement in the killing of tumor cells was further documented by the finding that the inhibitory effect of cetuximab on tumor growth in an in vivo xenogeneic model of A549 lung cancer cells in nude mice was abolished in tumor-bearing mice treated with cobra venom factor to deplete C (79). These are promising results that need to be confirmed using a similar approach in the study of other tumors because the effect of chemotherapy on C activation and the consequent impact of these treatments on cancer cell killing may be different in various tumors.

Conclusion

The introduction of recombinant Abs into the clinic to control tumor growth has fostered the interest in C as an anti-tumor defense system acting in close collaboration with other components of both innate and acquired immunity. This has prompted the development of various strategies to optimize their therapeutic efficiency including structural modifications of the Abs to promote C activation and also control C inhibitors expressed on the tumor cell surface to enhance Ab-induced C-mediated cell killing. Major efforts are being made to selectively deliver mCRPs neutralizing agents to tumor cells and the recently generated bispecific Abs that target cancer cells and inhibit mCRP appear to move in this direction.

An important point to consider when adopting this therapeutic approach is that C activated in the tumor microenvironment, particularly in the case of slow growing tumors associated with an inflammatory process developing in the surrounding tissue, may promote cancer expansion due to recruitment of suppressor cells by locally released C5a (Figure 1). We believe that this undesired effect may be prevented or markedly reduced by focusing Ab dependent C activation on residual tumor cells after surgical removal or substantial reduction of tumor mass after radio and/or chemotherapy. It is important, though, that the protocols for radiation therapy and chemotherapeutic treatment are selected to be highly effective in the control of tumor growth with limited pro-inflammatory side effects and negligible C activation in the tumor microenvironment.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Italian Ministry of Health, IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Ricerca Corrente and by Italian Association for Cancer Research.

References

1. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell (2011) 144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013

2. Wang M, Zhao J, Zhang L, Wei F, Lian Y, Wu Y, et al. Role of tumor microenvironment in tumorigenesis. J Cancer (2017) 8:761–73. doi: 10.7150/jca.17648

3. Pickup MW, Mouw JK, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix modulates the hallmarks of cancer. EMBO Rep. (2014) 15:1243–53. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439246

4. Siemann DW. The unique characteristics of tumor vasculature and preclinical evidence for its selective disruption by Tumor-Vascular Disrupting Agents. Cancer Treat Rev. (2011) 37:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.05.001

5. Zuazo-Gaztelu I, Casanovas O. Unraveling the role of angiogenesis in cancer ecosystems. Front Oncol. (2018) 8:248. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00248

6. Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science (2011) 331:1565–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486

7. Marcus A, Gowen BG, Thompson TW, Iannello A, Ardolino M, Deng W, et al. Recognition of tumors by the innate immune system and natural killer cells. Adv Immunol. (2014) 122:91–128. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800267-4.00003-1

8. Durgeau A, Virk Y, Corgnac S, Mami-Chouaib F. Recent advances in targeting CD8 T-cell immunity for more effective cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:14. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00014

9. Macor P, Tedesco F. Complement as effector system in cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Lett. (2007) 111:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.04.014

10. Lubbers R, van Essen MF, van Kooten C, Trouw LA. Production of complement components by cells of the immune system. Clin Exp Immunol. (2017) 188:183–94. doi: 10.1111/cei.12952

11. Markiewski MM, DeAngelis RA, Benencia F, Ricklin-Lichtsteiner SK, Koutoulaki A, Gerard C, et al. Modulation of the antitumor immune response by complement. Nat Immunol. (2008) 9:1225–35. doi: 10.1038/ni.1655

12. Corrales L, Ajona D, Rafail S, Lasarte JJ, Riezu-Boj JI, Lambris JD, et al. Anaphylatoxin C5a creates a favorable microenvironment for lung cancer progression. J Immunol. (2012) 189:4674–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201654

13. Vadrevu SK, Chintala NK, Sharma SK, Sharma P, Cleveland C, Riediger L, et al. Complement c5a receptor facilitates cancer metastasis by altering t-cell responses in the metastatic niche. Cancer Res. (2014) 74:3454–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0157

14. Kolev M, Markiewski MM. Targeting complement-mediated immunoregulation for cancer immunotherapy. Semin Immunol. (2018) 37:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2018.02.003

15. Bulla R, Tripodo C, Rami D, Ling GS, Agostinis C, Guarnotta C, et al. C1q acts in the tumour microenvironment as a cancer-promoting factor independently of complement activation. Nat Commun. (2016) 7:10346. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10346

16. Mamidi S, Höne S, Kirschfink M. The complement system in cancer: ambivalence between tumour destruction and promotion. Immunobiology (2017) 222:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2015.11.008

17. Bouwens TA, Trouw LA, Veerhuis R, Dirven CM, Lamfers ML, Al-Khawaja H. Complement activation in Glioblastoma Multiforme pathophysiology: evidence from serum levels and presence of complement activation products in tumor tissue. J Neuroimmunol. (2015) 278:271–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.11.016

18. Niculescu F, Rus HG, Retegan M, Vlaicu R. Persistent complement activation on tumor cells in breast cancer. Am J Pathol. (1992) 140:1039–43.

19. Lucas S, Ek B, Rask L, Rastad J, Akerstrom G, Juhlin C. Identification of a 35 kD tumor-associated autoantigen in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Anticancer Res. (1996) 16:2493–6.

20. Nitta H, Murakami Y, Wada Y, Eto M, Baba H, Imamura T. Cancer cells release anaphylatoxin C5a from C5 by serine protease to enhance invasiveness. Oncol Rep. (2014) 32:1715–9. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3341

21. Bandini S, Curcio C, Macagno M, Quaglino E, Arigoni M, Lanzardo S, et al. Early onset and enhanced growth of autochthonous mammary carcinomas in C3-deficient Her2/neu transgenic mice. Oncoimmunology (2013) 2:1–14. doi: 10.4161/onci.26137

22. Cho MS, Vasquez HG, Rupaimoole R, Pradeep S, Wu S, Zand B, et al. Autocrine effects of tumor-derived complement. Cell Rep. (2014) 6:1085–95. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.014

23. Fujita T, Taira S, Kodama N, Matsushita M, Fujita T. Mannose-binding protein recognizes glioma cells: in vitro analysis of complement activation on glioma cells via the lectin pathway. Jpn J Cancer Res. (1995) 86:187–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1995.tb03038.x

24. Budzko DB, Lachmann PJ, McConnell I. Activation of the alternative complement pathway by lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from patients with Burkitt's lymphoma and infectious mononucleosis. Cell Immunol. (1976) 22:98–109. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(76)90011-3

25. Theofilopoulos AN, Perrin LH. Binding of components of the properdin system to cultured human lymphoblastoid cells and B lymphocytes. J Exp Med. (1976) 143:271–89. doi: 10.1084/jem.143.2.271

26. McConnell I, Klein G, Lint TF, Lachmann PJ. Activation of the alternative complement pathway by human B cell lymphoma lines is associated with Epstein-Barr virus transformation of the cells. Eur J Immunol. (1978) 8:453–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830080702

27. Yefenof E, Åsjö B, Klein E. Alternative complement pathway activation by HIV infected cells: C3 fixation does not lead to complement lysis but enhances NK sensitivity. Int Immunol. (1991) 3:395–401. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.4.395

28. Vollmers HP, Brändlein S. Natural antibodies and cancer. N Biotechnol. (2009) 25:294–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2009.03.016

29. Díaz-Zaragoza M, Hernández-Ávila R, Viedma-Rodríguez R, Arenas-Aranda D, Ostoa-Saloma P. Natural and adaptive IgM antibodies in the recognition of tumor-associated antigens of breast cancer (Review). Oncol Rep. (2015) 34:1106–14. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4095

30. Devarapu SK, Mamidi S, Plöger F, Dill O, Blixt O, Kirschfink M, et al. Cytotoxic activity against human neuroblastoma and melanoma cells mediated by IgM antibodies derived from peripheral blood of healthy donors. Int J Cancer (2016) 138:2963–73. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30025

31. Barabas AZ, Cole CD, Graeff RM, Morcol T, Lafreniere R. A novel modified vaccination technique produces IgG antibodies that cause complement-mediated lysis of multiple myeloma cells carrying CD38 antigen. Hum Antibodies (2016) 24:45–51. doi: 10.3233/HAB-160294

32. Chiavenna SM, Jaworski JP, Vendrell A. State of the art in anti-cancer mAbs. J Biomed Sci. (2017) 24:15. doi: 10.1186/s12929-016-0311-y

33. Merle NS, Church SE, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Roumenina LT. Complement system part I - molecular mechanisms of activation and regulation. Front Immunol. (2015) 6:262. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00262

34. Shields RL, Namenuk AK, Hong K, Meng YG, Rae J, Briggs J, et al. High resolution mapping of the binding site on human IgG1 for FcγRI, FcγRII, FcγRIII, and FcRn and design of IgG1 variants with improved binding to the FcγR. J Biol Chem. (2001) 276:6591–604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009483200

35. Idusogie EE, Wong PY, Presta LG, Gazzano-Santoro H, Totpal K, Ultsch M, et al. Engineered antibodies with increased activity to recruit complement. J Immunol. (2001) 166:2571–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2571

36. Hayes JM, Wormald MR, Rudd PM, Davey GP. Fc gamma receptors: glycobiology and therapeutic prospects. J Inflamm Res. (2016) 9:209–19. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S121233

37. Hodoniczky J, Yuan ZZ, James DC. Control of recombinant monoclonal antibody effector functions by Fc N-glycan remodeling in vitro. Biotechnol Prog. (2005) 21:1644–52. doi: 10.1021/bp050228w

38. Diebolder CA, Beurskens FJ, De Jong RN, Koning RI, Strumane K, Lindorfer MA, et al. Complement is activated by IgG hexamers assembled at the cell surface. Science (2014) 343:1260–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1248943

39. Cook EM, Lindorfer MA, van der Horst H, Oostindie S, Beurskens FJ, Schuurman J, et al. Antibodies that efficiently form hexamers upon antigen binding can induce complement-dependent cytotoxicity under complement-limiting conditions. J Immunol. (2016) 197:1762–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600648

40. Mezzaroba N, Zorzet S, Secco E, Biffi S, Tripodo C, Calvaruso M, et al. New potential therapeutic approach for the treatment of B-cell malignancies using chlorambucil/hydroxychloroquine-loaded Anti-CD20 nanoparticles. PLoS ONE (2013) 8:e74216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074216

41. Capolla S, Mezzaroba N, Zorzet S, Tripodo C, Mendoza-Maldonado R, Granzotto M, et al. New approach for the treatment of CLL using chlorambucil/hydroxychloroquine loaded anti-CD20 nanoparticles. Nanoresearch (2016) 9:537–48. doi: 10.1007/s12274-015-0935-3

42. Macor P, Mezzanzanica D, Cossetti C, Alberti P, Figini M, Canevari S, et al. Complement activated by chimeric anti-folate receptor antibodies is an efficient effector system to control ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. (2006) 66:3876–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3434

43. Ziller F, Macor P, Bulla R, Sblattero D, Marzari R, Tedesco F. Controlling complement resistance in cancer by using human monoclonal antibodies that neutralize complement-regulatory proteins CD55 and CD59. Eur J Immunol. (2005) 35:2175–83. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425920

44. Coney L, Mezzanzanica D, Casalini P, Colnaghi MI. Chimeric murine-human antibodies directed against folate binding receptor are efficient mediators of ovarian carcinoma cell killing. Cancer Res. (1994) 54:2448–55.

45. Golay J, Lazzari M, Facchinetti V, Bernasconi S, Borleri G, Barbui T, et al. CD20 levels determine the in vitro susceptibility to rituximab and complement of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: further regulation by CD55 and CD59. Blood (2001) 98:3383–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.12.3383

46. Golay J, Zaffaroni L, Vaccari T, Lazzari M, Borleri GM, Bernasconi S, et al. Biologic response of B lymphoma cells to anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab in vitro: CD55 and CD59 regulate complement-mediated cell lysis. Blood (2000) 95:3900–8.

47. Cleary KLS, Chan HTC, James S, Glennie MJ, Cragg MS. Antibody distance from the cell membrane regulates antibody effector mechanisms. J Immunol. (2017) 198:3999–4011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601473

48. Derer S, Beurskens FJ, Rosner T, Peipp M, Valerius T. Complement in antibody-based tumor therapy. Crit Rev Immunol. (2014) 34:199–214. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.2014009761

49. Cragg MS, Morgan SM, Chan HT, Morgan BP, Filatov AV, Johnson PW, et al. Complement-mediated lysis by anti-CD20 mAb correlates with segregation into lipid rafts. Blood (2003) 101:1045–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1761

50. Stasiłojć G, Österborg A, Blom AM, Okrój M. New perspectives on complement mediated immunotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev. (2016) 45:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.02.009

51. Beurskens FJ, Lindorfer MA, Farooqui M, Beum PV, Engelberts P, Mackus WJ, et al. Exhaustion of cytotoxic effector systems may limit monoclonal antibody-based immunotherapy in cancer patients. J Immunol (2012) 188:3532–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103693

52. Taylor RP, Lindorfer MA. Cytotoxic mechanisms of immunotherapy: harnessing complement in the action of anti-tumor monoclonal antibodies. Semin Immunol. (2016) 28:309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2016.03.003

53. Klepfish A, Gilles L, Ioannis K, Eliezer R, Ami S. Enhancing the action of rituximab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia by adding fresh frozen plasma: complementrituximab interactions and clinical results in refractory CLL. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2009) 1173:865–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04803.x

54. Xu W, Miao KR, Zhu DX, Fang C, Zhu HY, Dong HJ, et al. Enhancing the action of rituximab by adding fresh frozen plasma for the treatment of fludarabine refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Int J Cancer (2011) 128:2192–201. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25560

55. Biffi S, Garrovo C, Macor P, Tripodo C, Zorzet S, Secco E, et al. In vivo biodistribution and lifetime analysis of Cy5. 5-conjugated rituximab in mice bearing lymphoid tumor xenograft using time-domain near-infrared optical imaging. Mol Imaging (2008) 7:272–82. doi: 10.2310/7290.2008.00028

56. Macor P, Tripodo C, Zorzet S, Piovan E, Bossi F, Marzari R, et al. In vivo targeting of human neutralizing antibodies against CD55 and CD59 to lymphoma cells increases the antitumor activity of rituximab. Cancer Res. (2007) 67:10556–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1811

57. Verma MK, Clemens J, Burzenski L, Sampson SB, Brehm MA, Greiner DL, et al. A novel hemolytic complement-sufficient NSG mouse model supports studies of complement-mediated antitumor activity in vivo. J Immunol Methods (2017) 446:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2017.03.021

58. Triantafilou K, Hughes TR, Triantafilou M, Morgan BP. The complement membrane attack complex triggers intracellular Ca2+ fluxes leading to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Cell Sci. (2013) 126:2903–13. doi: 10.1242/jcs.124388

59. Lindorfer MA, Cook EM, Tupitza JC, Zent CS, Burack R, de Jong RN, et al. Real-time analysis of the detailed sequence of cellular events in mAb-mediated complement-dependent cytotoxicity of B-cell lines and of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B-cells. Mol Immunol. (2016) 70:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.12.007

60. Macor P, Secco E, Mezzaroba N, Zorzet S, Durigutto P, Gaiotto T, et al. Bispecific antibodies targeting tumor-associated antigens and neutralizing complement regulators increase the efficacy of antibody-based immunotherapy in mice. Leukemia (2015) 29:406–14. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.185

61. Ramm LE, Whitlow MB, Koski CL, Shin ML, Mayer MM. Elimination of complement channels from the plasma membranes of U937, a nucleated mammalian cell line: temperature dependence of the elimination rate. J Immunol. (1983) 131:1411–5.

62. Carney DF, Koski CL, Shin ML. Elimination of terminal complement intermediates from the plasma membrane of nucleated cells: the rate of disappearance differs for cells carrying C5b-7 or C5b-8 or a mixture of C5b-8 with a limited number of C5b-9. J Immunol. (1985) 134:1804–9.

63. Kerjaschki D, Schulze M, Binder S, Kain R, Ojha PP, Susani M, et al. Transcellular transport and membrane insertion of the C5b-9 membrane attack complex of complement by glomerular epithelial cells in experimental membranous nephropathy. J Immunol. (1989) 143:546–52.

64. Scolding NJ, Morgan BP, Houston WA, Linington C, Campbell AK, Compston DA. Vesicular removal by oligodendrocytes of membrane attack complexes formed by activated complement. Nature (1989) 339:620–2. doi: 10.1038/339620a0

65. Moskovich O, Fishelson Z. Live cell imaging of outward and inward vesiculation induced by the complement C5b-9 complex. J Biol Chem. (2007) 282:29977–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703742200

66. Dho SH, Lim JC, Kim LK. Beyond the role of CD55 as a complement component. Immune Netw. (2018) 18:e11. doi: 10.4110/in.2018.18.e11

67. Killick J, Morisse G, Sieger D, Astier AL. Complement as a regulator of adaptive immunity. Semin Immunopathol. (2018) 40:37–48. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0644-y

68. MacIejczyk A, Szelachowska J, Szynglarewicz B, Szulc R, Szulc A, Wysocka T, et al. CD46 expression is an unfavorable prognostic factor in breast cancer cases. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. (2011) 19:540–6. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e31821a0be9

69. Surowiak P, Materna V, Maciejczyk A, Kaplenko I, Spaczynski M, Dietel M, et al. CD46 expression is indicative of shorter revival-free survival for ovarian cancer patients. Anticancer Res. (2006) 26:4943–8.

70. Zhang R, Liu Q, Liao Q, Zhao Y. CD59: a promising target for tumor immunotherapy. Future Oncol. (2018) 14:781–91. doi: 10.2217/fon-2017-0498

71. Marshall MJE, Stopforth RJ, Cragg MS. Therapeutic antibodies: what have we learnt from targeting CD20 and where are we going? Front Immunol. (2017) 8:1245. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01245

72. Mössner E, Brünker P, Moser S, Püntener U, Schmidt C, Herter S, et al. Increasing the efficacy of CD20 antibody therapy through the engineering of a new type II anti-CD20 antibody with enhanced direct and immune effector cell - mediated B-cell cytotoxicity. Blood (2010) 115:4393–402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-225979

73. Cartron G, Watier H. Obinutuzumab: what is there to learn from clinical trials? Blood (2017) 130:581–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-03-771832

74. Bologna L, Gotti E, Manganini M, Rambaldi A, Intermesoli T, Introna M, et al. Mechanism of action of type II, glycoengineered, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody GA101 in B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia whole blood assays in comparison with rituximab and alemtuzumab. J Immunol. (2011) 186:3762–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000303

75. Zent CS, Secreto CR, LaPlant BR, Bone ND, Call TG, Shanafelt TD, et al. Direct and complement dependent cytotoxicity in CLL cells from patients with high-risk early-intermediate stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treated with alemtuzumab and rituximab. Leuk Res. (2008) 32:1849–56. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.05.014

76. de Weers M, Tai YT, van der Veer MS, Bakker JM, Vink T, Jacobs DC, et al. Daratumumab, a novel therapeutic human CD38 monoclonal antibody, induces killing of multiple myeloma and other hematological tumors. J Immunol. (2011) 186:1840–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003032

77. Nijhof IS, Groen RW, Lokhorst HM, van Kessel B, Bloem AC, van Velzen J, et al. Upregulation of CD38 expression on multiple myeloma cells by all-trans retinoic acid improves the efficacy of daratumumab. Leukemia (2015) 29:2039–49. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.123

78. Dechant M, Weisner W, Berger S, Peipp M, Beyer T, Schneider-Merck T, et al. Complement-dependent tumor cell lysis triggered by combinations of epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies. Cancer Res. (2008) 68:4998–5003. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6226

79. Hsu YF, Ajona D, Corrales L, Lopez-Picazo JM, Gurpide A, Montuenga LM, et al. Complement activation mediates cetuximab inhibition of non-small cell lung cancer tumor growth in vivo. Mol Cancer (2010) 9:139. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-139

80. Dhillon S. Dinutuximab : first global approval. Drugs (2015) 75:923–7. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0399-5

81. El-Sahwi K, Bellone S, Cocco E, Cargnelutti M, Casagrande F, Bellone M, et al. In vitro activity of pertuzumab in combination with trastuzumab in uterine serous papillary adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer (2010) 102:134–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605448

82. Spiridon CI, Ghetie MA, Uhr J, Marches R, Li JL, Shen GL, et al. Targeting multiple Her-2 epitopes with monoclonal antibodies results in improved antigrowth activity of a human breast cancer cell line in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. (2002) 8:1720–30.

83. Zhao WP, Zhu B, Duan YZ, Chen ZT. Neutralization of complement regulatory proteins CD55 and CD59 augments therapeutic effect of herceptin against lung carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. (2009) 21:1405–11. doi: 10.3892/or_00000368

84. Mamidi S, Cinci M, Hasmann M, Fehring V, Kirschfink M. Lipoplex mediated silencing of membrane regulators (CD46, CD55 and CD59) enhances complement-dependent anti-tumor activity of trastuzumab and pertuzumab. Mol Oncol. (2013) 7:580–94. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2013.02.011

85. Ray MS, Moskovich O, Iosefson O, Fishelson Z. Mortalin/GRP75 binds to complement C9 and plays a role in resistance to complement-dependent cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. (2014) 289:15014–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.552406

86. Surace L, Lysenko V, Fontana AO, Cecconi V, Janssen H, Bicvic A, et al. Complement is a central mediator of radiotherapy-induced tumor-specific immunity and clinical response. Immunity (2015) 42:767–77. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.03.009

87. Elvington M, Scheiber M, Yang X, Lyons K, Jacqmin D, Wadsworth C, et al. Complement-dependent modulation of antitumor immunity following radiation therapy. Cell Rep. (2014) 8:818–30. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.051

88. Michlmayr A, Bachleitner-Hofmann T, Baumann S, Marchetti-Deschmann M, Rech-Weichselbraun I, Burghuber C, et al. Modulation of plasma complement by the initial dose of epirubicin/docetaxel therapy in breast cancer and its predictive value. Br J Cancer (2010) 103:1201–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605909

89. Keizer MP, Kamp AM, Aarts C, Geisler J, Caron HN, van De Wetering MD, et al. The high prevalence of functional complement defects induced by chemotherapy. Front Immunol. (2016) 7:420. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00420

Keywords: complement system activation, tumor control, antibody-based immunotherapy, combination therapies, antibody

Citation: Macor P, Capolla S and Tedesco F (2018) Complement as a Biological Tool to Control Tumor Growth. Front. Immunol. 9:2203. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02203

Received: 29 June 2018; Accepted: 05 September 2018;

Published: 25 September 2018.

Edited by:

Maciej M. Markiewski, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Ronald Paul Taylor, University of Virginia, United StatesFabian Benencia, Ohio University, United States

Copyright © 2018 Macor, Capolla and Tedesco. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Francesco Tedesco, dGVkZXNjb0B1bml0cy5pdA==

Paolo Macor

Paolo Macor Sara Capolla

Sara Capolla Francesco Tedesco

Francesco Tedesco