- 1Center for Life Sciences, School of Life Sciences, Yunnan University, Kunming, China

- 2Department of Anesthesiology, McGovern Medical School, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, United States

Ample evidence suggests that hepatic macrophages play key roles in the injury and repair mechanisms during liver disease progression. There are two major populations of hepatic macrophages: the liver resident Kupffer cells and the monocyte-derived macrophages, which rapidly infiltrate the liver during injury. Under different disease conditions, the tissue microenvironmental cues of the liver critically influence the phenotypes and functions of hepatic macrophages. Furthermore, hepatic macrophages interact with multiple cells types in the liver, such as hepatocytes, neutrophils, endothelial cells, and platelets. These crosstalk interactions are of paramount importance in regulating the extents of liver injury, repair, and ultimately liver disease progression. In this review, we summarize the novel findings highlighting the impact of injury-induced microenvironmental signals that determine the phenotype and function of hepatic macrophages. Moreover, we discuss the role of hepatic macrophages in homeostasis and pathological conditions through crosstalk interactions with other cells of the liver.

Introduction

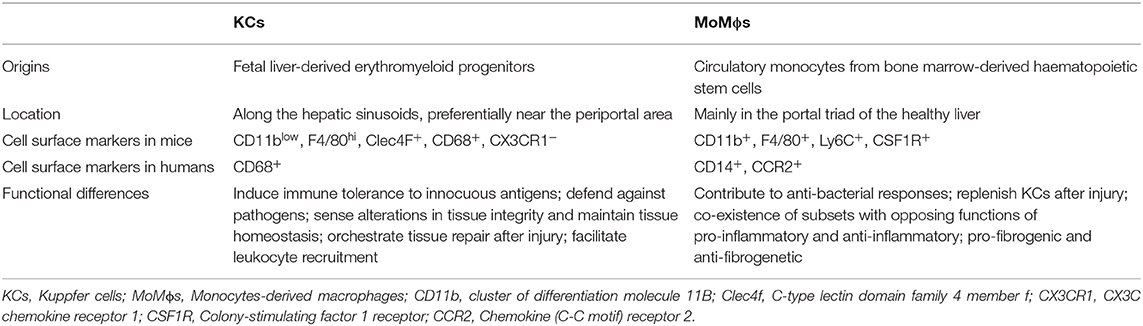

Hepatic macrophages, consisting of liver resident Kupffer cells (KCs) and monocyte-derived macrophages (MoMϕs), play a central role in maintaining homeostasis of the liver as well as contributing to the progression of acute or chronic liver injury (1). Kupffer cells are the most abundant tissue macrophages in mammalian bodies, accounting for 80–90% of total tissue macrophages (2). In the liver, KCs are distributed along the hepatic sinusoids, preferentially near the periportal areas (3). In the healthy liver, a small number of MoMϕs are located mainly in the portal triad areas (4, 5). In mouse, KCs and MoMϕs can be distinguished by their differential expression of certain cell surface markers. Kupffer cells are defined as CD11blow, F4/80hi, C-type lectin domain family 4 member F, CD68+, and CX3C chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1)− (6, 7). MoMϕs are CD11b+, F4/80+, Ly6C+, macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R)+. Human KCs are not as well-characterized and normally identified as CD68+ cells (8). Human MoMϕs are normally identified as CD14+, CC-chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2)+ cells (Table 1) (8, 9).

A salient function of macrophages is to remove pathogens and dead cells (3). In a healthy liver, KCs constantly phagocytose aged erythrocytes, neutrophils, and effector CD8+ T cells, thereby maintaining homeostasis within the liver (10–12). Monocyte-derived macrophages are also able to phagocytose dead endothelial cells and maintain integrity of vasculature under normal condition (13). The phagocytosis function of macrophages and its contribution to liver homeostasis and disease have been recently highlighted in an excellent review (14). Aside from phagocytosis, macrophages act as antigen-presenting cells and regulate adaptive immune responses. It is known that KCs play a central role in inducing immune tolerance to innocuous antigens that reached the liver from the intestine (15). In contrast, MoMϕs that are recruited into the liver lose the tolerogenic phenotype and instead contribute to antigen-specific proinflammatory immune responses (Table 1) (16). During liver injury, a large number of circulating monocytes infiltrate into the liver and further differentiate into MoMϕs (17). Injury-induced modulations of the liver tissue microenvironment, such as soluble mediators released by activated/stress cells and accumulation of dead cells, influence the phenotypes of both KCs and MoMϕs and determine their involvement in aggravation of liver injury or restoration of liver functions (6, 16, 17). Under healthy and disease conditions, we call any signals received from local microenvironment and prompted functional differentiation of hepatic macrophages as microenvironmental signals. Understanding how microenvironmental signals affect the heterogeneity of hepatic macrophages and how hepatic macrophages interact with other cells during liver injury is instrumental not only in gaining basic knowledge but also in designing therapeutic strategies to treat liver diseases. In this review, we summarize the latest findings about specific environmental signals that impact the phenotype and function of hepatic macrophages and discuss the functions of hepatic macrophages in healthy and diseased liver through interacting with other cells.

Origin of Hepatic Macrophages

The recent development and improvement of research tools have allowed us to gain novel insights into the origin of hepatic macrophages. Contrary to the notion that KCs are originated solely from bone marrow–derived circulating monocytes (18), recent evidence suggests that KCs are mainly derived from yolk sac erythromyeloid progenitors (EMPs). Erythromyeloid progenitors colonize the fetal liver at E8.5 and give rise to macrophage precursors (pMacs) at E9.5 in a CX3CR1-dependent manner. A distinct transcriptional programming involving the upregulation of DNA binding 3 (Id3) is important in the further differentiation of pMacs into KCs (19). With regard to the maintenance of tissue-resident macrophages including KCs, an interesting “niche competition” model has been put forth. This model proposes that bone marrow–derived circulating monocytes and EMPs have an almost identical potential to develop into KCs and that they compete for a restricted number of niches. However, during liver development, the majority of liver niches are taken by EMPs and few by monocytes. At steady state, the niches in liver are self-maintained and tightly controlled by specific Maf transcription repressors and enhancers (20). However, when a significant number of KCs die or depleted experimentally, circulating monocytes have been shown to contribute to the KCs pool, suggesting that circulating monocytes have the potential as their embryonic counterparts to develop into KCs (21–23).

Monocyte-derived macrophages are derived from circulatory monocytes, which are developed from bone marrow–resident hematopoietic stem cells (23). Hematopoietic stem cells first differentiate into common lymphoid progenitors and then into granulocyte–monocyte progenitors (24, 25). Granulocyte–monocyte progenitors further give rise to common monocyte progenitors (cMoPs) under the regulation of macrophage CSF-1 (26). Eventually, cMoPs differentiate into circulatory monocytes. These distinct steps of hepatic stellate cell (HSC) differentiation into monocytes are tightly regulated by a number of transcription factors and epigenetic DNA methylation mechanisms (23). In mice, there are two subsets of monocytes in the liver: Ly6Chi and Ly6Clow monocytes. The Ly6Chi monocytes can differentiate into Ly6Clow monocytes, which can further differentiate into MoMϕs (27, 28). In humans, the CD14hiCD16− and CD14−CD16hi monocytes correlate with Ly6Chi and Ly6Clow monocytes in mice, respectively (29).

Impact of Tissue Microenvironmental Factors on Hepatic Macrophages

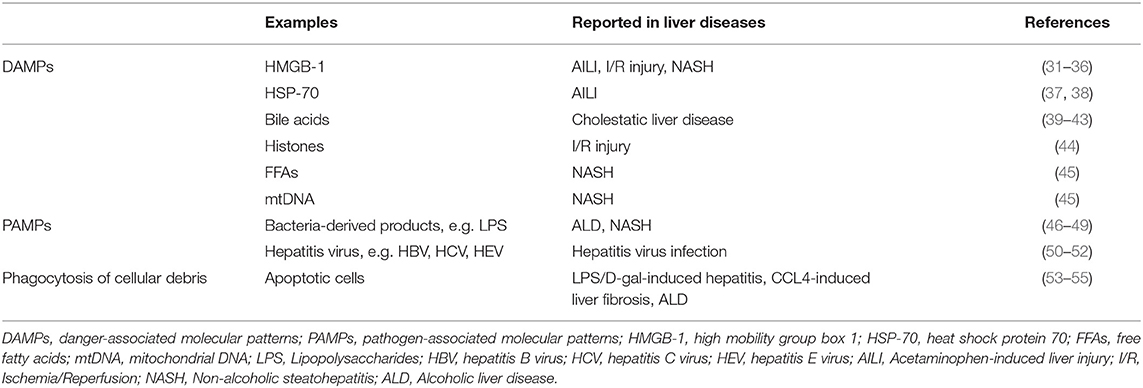

Irrespective of the cellular origins of hepatic macrophages, they differentiate into different phenotypes depending on the stimulatory signals in the tissue environment (30). In disease conditions, there are two major types of stimulatory signals (Table 2), including danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs).

Danger-associated molecular patterns are a diverse group of molecules including nucleic acid in various conformations (e.g., single-/double-stranded RNA or DNA), nuclear proteins [e.g., high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1)], cytosolic proteins [e.g., heat shock protein 70 (HSP-70)], purine nucleotides [e.g., adenosine triphosphate (ATP)], or mitochondrial compounds (e.g., mtDNA, N-formyl peptides). Danger-associated molecular patterns are recognized by pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs), which are expressed on hepatic macrophages and can activate the cells (56, 57). These PRR receptors include Toll-like receptors (TLRs), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain–like receptors (NLRs), and retinoic acid-inducible gene 1–like receptors (56). Danger-associated molecular patterns play a critical role in activating macrophages during sterile liver injury, which can be caused by a variety of stimuli, such as overdose of acetaminophen (APAP), cholestatic obstruction, excess accumulation of free fatty acids (FFAs), or hepatic ischemia, and reperfusion (I/R) (31, 58). The release of DAMPs is common in these situations, and it may be an active process from viable or dying cells, or a passive process leaking out from necrotic cells (56).

In APAP-induced liver injury (AILI), hepatocyte damage leads to the release of HMGB1, which activates KCs to produce proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (31). High mobility group box 1 is a nuclear-binding protein that can function as a DNA chaperone in nucleus, sustaining autophagy in cytosol and DAMP molecule outside the cell (32). High mobility group box 1–deficient mice show less inflammation and neutrophil recruitment post-APAP treatment when compared to their wild-type counterparts (31, 33). Mice lacking the receptor for advanced glycation end products, a receptor for HMGB1, on bone marrow–derived cells display a similar phenotype as the HMGB1-deficient mice (31, 33). Together, these data indicate that HMGB1 activates KCs and contributes to AILI (31, 33). Aside from HMGB1, HSP-70 has also been reported to be released by necrotic hepatocytes during AILI (37). Heat shock protein 70 is an important component of cellular machinery, facilitating protein folding, but also an inducible stress-response protein that can undergo translocation to the cell surface or is released into the extracellular milieu during cellular stress or necrotic death (38). Heat shock protein 70 can stimulate macrophages to promote immune response and inflammation (37).

Similar to the necroinflammatory injury pattern in AILI, cholestatic liver disease is also characterized by hepatocytes necrosis (59). Lesions in bile duct canaliculi cause an increase of bile acids, which result in liver injury, but appear to drive KCs into anti-inflammatory state (39, 59). Bile acids can bind to G-protein–coupled bile acid receptor (TGR5), which is expressed on hepatic macrophages (40). Activation of TGR5 in macrophages reduces proinflammatory cytokines while maintaining anti-inflammatory cytokines (41). The anti-inflammatory effect of TGR5 on macrophages is mediated by inhibiting nuclear factor κB and JNK signaling pathways and NLRP3 inflammasome (41, 43).

Hepatic I/R injury is another example of sterile tissue injury in which DAMPs are released. It is reported that after I/R injury hepatocytes actively secrete HMGB1, which binds to TLR4 and activates KCs (34). In addition to HMGB1, other DAMPs, such as histones, DNA fragments, ATP, and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), also activate KCs via different PRRs, such as TLR9 (recognizing histones) (44), TLR3 (recognizing RNA) (60, 61), TLR4 (recognizing HSP-70) (62), and nucleotide-binding domain leucine-rich repeat containing family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) (recognizing ATP) (63, 64). As a result, KCs secrete ample proinflammatory cytokines to exacerbate I/R injury (65).

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is characterized by steatosis with tissue injury and inflammation (35). Increased accumulation of fat in hepatocytes leads to lipotoxicity, which induces apoptotic and necrotic death of hepatocytes with concomitant release of DAMPs, such as HMGB1 and FFAs (35). Released HMGB1 activates KCs via TLR4 as in other liver injury cases (35, 36). Free fatty acids decrease the mitochondrial membrane potential and subsequently induce mtDNA release from the mitochondria to the cytoplasm (45). Released mtDNA causes NLRP3 inflammasome activation in KCs, which further promotes the production of proinflammatory interleukin 1β (IL-1β) (45).

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns include pathogen-specific polysaccharides, lipoproteins, and nucleic acids. They bind to PPRs expressed on hepatic macrophages and trigger inflammatory activation of these cells (66). In alcoholic liver disease (ALD), excess chronic ingestion of alcohol increases gut permeability and causes translocation of bacteria-derived products, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPSs), from the gut to the liver (67). Lipopolysaccharide binds to CD14 in association with TLR4 on KCs to initiate proinflammatory signaling (46). Numerous studies have demonstrated that KCs play a central role in alcohol-induced inflammation and injury of the liver (27, 28). Kupffer cells produce cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and free radicals to promote ALD (68, 69). In addition to KCs, MoMϕs can be differentiated from the circulating monocytes that are recruited into the liver as a result of the inflammatory response during liver injury (28). Two types of MoMϕs (Ly6Clow MoMϕs and Ly6Chi MoMϕs) have been reported to coexist in the liver of mice after chronic alcohol feeding. The Ly6Clow MoMϕs exhibit restorative phenotype, whereas Ly6Chi MoMϕs exhibit proinflammatory phenotype. A large dose of alcohol binge after chronic alcohol feeding enhances liver inflammation and injury with an increased ratio of Ly6Chi/Ly6Clow MoMϕ. Moreover, Ly6Chi MoMϕ switches to Ly6Clow MoMϕ upon phagocytosis of apoptotic hepatocytes. Taken together, KCs and MoMϕ are involved in the pathogenesis of ALD (27, 28, 70).

Whereas, translocation of LPS from the gut lumen to portal circulation in ALD may result from direct alcohol toxicity to intestinal epithelium (67), increased exposure to intestinal LPS has also been considered in the pathogenesis of NASH (71). Increased levels of LPS in the portal circulation have been observed during NASH development (72). The role of LPS-TLR4 signaling in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has been demonstrated in a number of studies (47). Toll-like receptor 4 expression on KCs is elevated both in patients with NASH and mice fed with methionine–choline–deficient diet (47, 48). Depletion of KCs by clodronate liposomes significantly reduced TLR4 expression and steatohepatitis (47). Together, endotoxin appears to play an important role in NAFLD through TLRs on KCs, particularly TLR4. However, the function of MoMϕ in response to endotoxin during NAFLD remains unclear.

Hepatitis virus infection is a leading cause of chronic liver diseases (49). Hepatitis B virus (HBV) modulates liver macrophage functions to favor viral replication and survival. These modulations include reduced production of antiviral cytokine IL-1β and enhanced levels of immunosuppressive IL-10 (73). Hepatitis C virus (HCV) can enter KCs through phagocytic uptake. Subsequently, viral RNA triggers myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88)–mediated TLR7 signaling to induce IL-1β expression. Hepatitis C virus uptake concomitantly induces a potassium efflux that activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and promotes the secretion of activated IL-1β. Interleukin 1β produced by KCs contributes to HCV disease severity (74). It has also been reported that the function of monocytes/macrophages is impaired in pregnant patients with hepatitis E virus (HEV)–induced acute hepatitis (50). Toll-like receptor 3 and TLR7 expressions are reduced, and MyD88 downstream molecules, IRF3 and IRF7, are decreased in macrophages from these patients (50). The macrophage phagocytic activity and Escherichia coli–induced ROS production are significantly impaired in macrophages from HEV patients as well (50). These data suggest that the impact of viruses on hepatic macrophages could result in immune suppression and/or inflammation and tissue damage.

Phagocytosis of Dead Cells

A salient function of macrophages is to remove dead cells and cellular debris, which is a key initial step in resolving tissue inflammation and promoting tissue repair from injury. It has been widely reported that phagocytosis of dead cells triggers transcriptional reprogramming of macrophages to switch from a proinflammatory to an anti-inflammatory and tissue restorative phenotype. For example, it is shown that the membrane-bound transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) on apoptotic cells can trigger KCs to produce IL-10, which suppresses the proinflammatory immune response in a mouse model of LPS/D-galactosamine–induced hepatitis (51, 52). In a mouse model of ALD, it is reported that phagocytosis of cellular debris triggers hepatic macrophages to switch from proinflammatory to an anti-inflammatory phenotype (28). Similarly, in a mouse model of carbon tetrachloride–induced liver fibrosis, phagocytosis of cellular debris induces Ly6Chi proinflammatory, profibrotic MoMϕs to differentiate into antifibrotic macrophages (52). The restorative macrophages are the most abundant subset in the liver during maximal fibrosis resolution and represent the predominant source of matrix metalloproteinases. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that phagocytosis of necrotic hepatocytes by macrophages activates Wnt ligand secretion, thereby promoting liver regeneration (53).

In summary, the particular function of KCs and MoMϕ is tightly regulated by microenvironmental signals, such as DAMPs and PAMPs. The same signals may play a similar role in different liver diseases; for example, HMGB1 released by hepatocytes triggers KC activation in AILI, I/R, and NASH, indicating similar functions of macrophages in various liver diseases (32–34, 37, 54, 56, 58, 75, 76). In certain liver diseases, such as NAFLD and ALD, DAMPs and PAMPs coexist to regulate macrophage functions (35, 56, 77, 78) However, more studies are warranted to better understand the differential functions of KCs and MoMϕs in a given disease situation.

Communication Between Hepatic Macrophages and Other Cells in the Liver

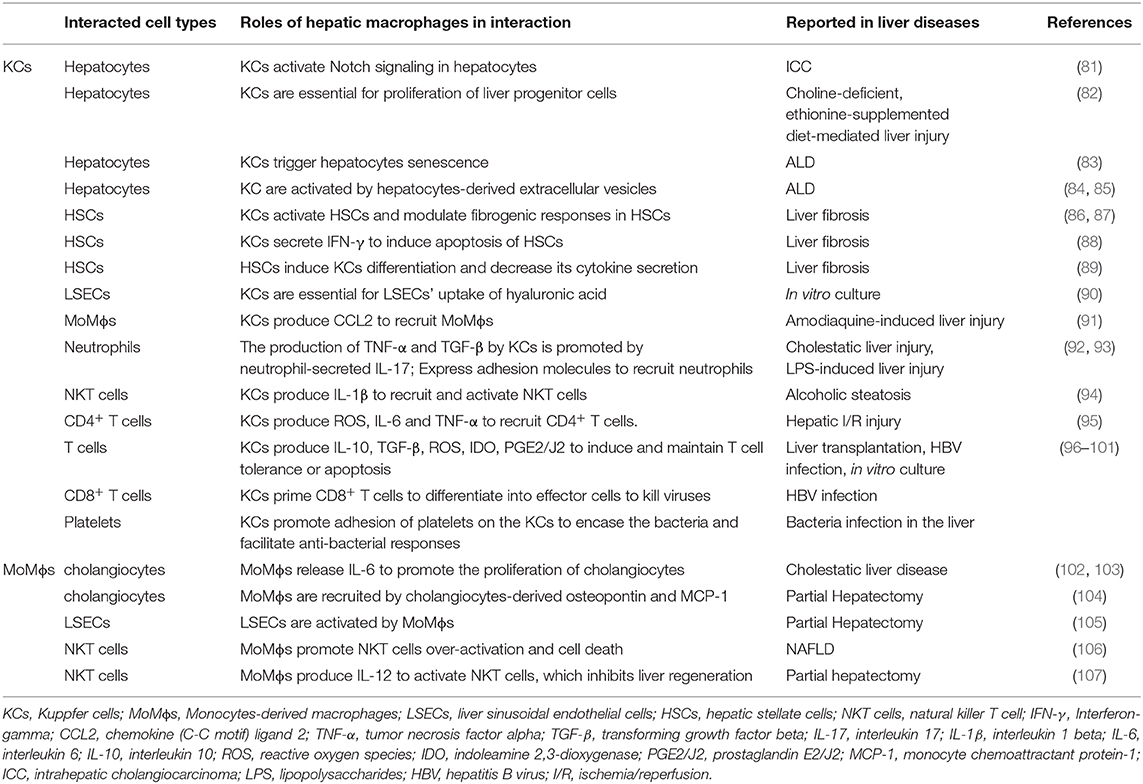

There are five major cell types in the liver including hepatocytes, biliary epithelial cells (cholangiocytes), liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs), KCs, and HSCs (66, 79). Hepatocytes account for roughly 80% of the liver's mass (79), and they perform a number of vital functions, including protein synthesis, detoxification, and metabolism of lipids and carbohydrates (79). Cholangiocytes are another type of epithelial cells in the liver, lining the lumen of the bile ducts (79). Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells form the lining of the smallest blood vessels in the liver, part of the reticuloendothelial system (79). Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells regulate the passage of molecules from the blood vessels into the liver (79). Hepatic stellate cells are found in the space of Disse, between hepatocytes and LSECs. Hepatic stellate cells can transdifferentiate from a quiescent state to an activated, highly proliferative, and wound-healing myofibroblast (80). In addition, there are a variety of other immune cells such as monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets that contribute to liver homeostasis as well as disease progression (66). In different types and stages of liver diseases, hepatic macrophages are critically involved in the progression and regression via close communication with other cells in the liver (Table 3) (108).

Crosstalk Between Hepatic Macrophages and Hepatocytes

The crosstalk between hepatic macrophages and hepatocytes has been indicated in a number of studies. In a mouse model of thioacetamide (TAA)–induced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, KCs accumulate around the central vein area and express Notch ligand Jagged-1 rapidly after the initiation of the TAA treatment, coinciding with the activation of Notch signaling in pericentral hepatocytes. Depletion of KCs prevents the Notch-mediated hepatocytes transformation to cholangiocytes, suggesting that KCs contribute to the cell fate change in hepatocytes (109). Another study has also demonstrated that KCs are required for the proliferation of liver progenitor cells that can differentiate into hepatocytes in a model of choline-deficient, ethionine-supplemented diet–mediated liver injury and regeneration (110). In ALD, it is shown that KC-produced IL-6 triggers hepatocyte senescence, which becomes resistant to apoptosis (81). Interestingly, recent studies also support that hepatocytes communicate with macrophages through the release of extracellular vesicles (EVs) that contain proteins and microRNAs (82, 83). In vitro studies using HepG2 cells have demonstrated that alcohol treatment induces an elevated release of EVs, which activate THP-1 cells, a human leukemia monocytic cell line into a proinflammatory phenotype through CD40 ligand (83). Another study also showed that exosomes derived from alcohol-treated hepatocytes mediated the transfer of liver-specific miRNA-122 to monocytes and sensitized monocytes to LPS stimulation (82). These studies suggest that hepatocytes release EVs that contain altered proteins and miRNAs to regulate the activation of monocytes/macrophages.

Interactions of Hepatic Macrophages With Cholangiocytes, HSCs, and LSECs

Macrophages secrete IL-6 during infection, and IL-6 can induce cholangiocyte proliferation leading to ductular reaction (84, 85). On the other hand, cholangiocytes are the major source of osteopontin and macrophage chemoattractant protein 1, which acts as chemotaxis to recruit MoMϕs during partial hepatectomy (102). Hepatic stellate cells and KCs are located in close proximity to each other (86, 103). In a mouse model of CCl4-induced liver fibrosis, it is shown that depletion of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α in HSCs inhibits KC activation and reduces the release of proinflammatory cytokines, suggesting a function of HSCs in regulating KCs during liver fibrosis (87). On the other hand, KCs have also been reported to modulate HSC functions. Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 6 stimulates the phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor and the expression of TGF-β in KCs, which further activates HSCs and results in liver fibrosis (103). It is reported that ROS and IL-6 activate KCs, which in turn modulate fibrogenic responses of HSCs (104). Activated KCs secrete interferon γ, which subsequently induces HSC apoptosis in a STAT1-dependent manner and reduces liver fibrosis (111). Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells are the major source of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1). In partial hepatectomy, ICAM-1 expressed on KCs and LSECs recruits leukocytes, which leads to TNF-α and IL-6 production, thereby promoting hepatocyte proliferation (89). Moreover, MoMϕs also play an important role in activating LSECs and contributing to vascular growth and liver regeneration (88). Kupffer cell depletion inhibits hyaluronic acid uptake by LSECs and impairs sinusoidal integrity, suggesting there is a crosstalk between KCs and LSECs (37, 112).

Interactions of Macrophages With Other Hepatic Immune Cells

Kupffer cell activation by pathogens results in CCL2 secretion, which promotes the recruitment of monocytes into the injured liver (105). It has been reported that alcohol treatment of THP-1 cells or human primary monocytes triggers the secretion of EVs, which induce the differentiation of naive monocytes into anti-inflammatory macrophages by delivering cargos, such as miR-27a (90).

Neutrophils are the most abundant white blood cells in the circulation, and they are recruited to the liver in various injury conditions (91). During cholestatic liver injury, neutrophils secrete IL-17, which promotes the production of TNF-α and TGF-β by KCs. On the other hand, KCs express adhesion molecules that induce neutrophil attachment and facilitate bacterial clearance in the liver (113). Another study reported that KCs coordinate with LSECs for neutrophil adhesion, recruitment, and activation through TLR4 during LPS-induced liver injury (78).

Natural killer T (NKT) cells are a group of “unconventional” T cells that express both natural killer (NK) cell receptors and T cell receptors. In the NASH liver, lipid accumulation causes an increase of the number of MoMϕs and activates the cells to a proinflammatory phenotype. Activated MoMϕs promote NKT cell activation and induce NKT cell deficiency, contributing to the pathogenesis of NAFLD (93). The importance of KC/NKT interaction in liver regeneration has also been described. After partial hepatectomy, MoMϕs produce IL-12 to activate hepatic NKT cells, which prohibit liver regeneration (114). In ALD, NLRP3 inflammasome activation results in IL-1β release by KCs. Released IL-1β recruits and activates hepatic invariant NKT cells, which promote liver inflammation, neutrophil infiltration, and liver injury (106). Furthermore, ample evidence supports the importance of macrophages in interacting with conventional T cells. It has been shown that KCs trigger the recruitment of CD4+ T cells by ROS, IL-6, and TNF-α (107). Kupffer cells express high levels of MHC class II and act as antigen-presenting cells. In fact, a number of studies have shown that KCs play an important role in inducing and maintaining T cell tolerance, through producing tolerogenic mediators such as IL-10, TGF-β, ROS, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, prostaglandin E2/J2 (94, 97). Moreover, it is reported that during liver transplantation KCs induce T cell apoptosis and thus promote immune tolerance (98). After HBV infection, KCs produce IL-10 and support liver tolerance by inducing anti-HBV CD8+ T cell exhaustion (99). A recent study demonstrated that the induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in HCC cell lines induces the secretion of EVs. The HCC-derived EVs induce elevated expression of programmed death ligand 1 on macrophages in vivo and in vitro, which causes T cell dysfunction and impaired proliferation (100). Recent studies showed that priming CD8+ T cells by KCs leads to the differentiation of CD8+ T cells into effector cells that have powerful killing activities against hepatitis viruses, such as HBV (101).

Moreover, interesting interactions between macrophages and platelets have been unveiled (115). Under basal conditions, platelets form transient “touch-and-go” interactions with von Willebrand factor constitutively expressed on KCs (115). During bacterial infection, platelets switch from “tough-and-go” to sustained GPIIb-mediated adhesion on the KCs to encase the bacteria and facilitate anti-bacterial responses (115).

In summary, hepatic macrophages interact with almost all cell types of the liver. In naive state, KCs, through these interactions, play a critical role in maintaining tissue homeostasis. Under injury or disease conditions, the crosstalk of macrophages with hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, LSECs, HSCs, and other immune cells contributes to exacerbation of tissue damage or promotion of liver repair and regeneration, depending on the cell type and signaling pathways involved.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication. ZS wrote the draft. CJ revised the manuscript.

Funding

CJ received funding from NIH (DK109574, DK121330, DK122708, AA021723, and AA024636) and support from a University of Texas System Translational STARs award. ZS received funding from YNU Double first class university plan (C1762201000142).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Ju C, Tacke F. Hepatic macrophages in homeostasis and liver diseases: from pathogenesis to novel therapeutic strategies. Cell Mol Immunol. (2016) 13:316–27. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.104

2. Bilzer M, Roggel F, Gerbes AL. Role of Kupffer cells in host defense and liver disease. Liver Int. (2006) 26:1175–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01342.x

3. Abdullah Z, Knolle PA. Liver macrophages in healthy and diseased liver. Pflugers Arch. (2017) 469:553–60. doi: 10.1007/s00424-017-1954-6

4. Theurl I, Hilgendorf I, Nairz M, Tymoszuk P, Haschka D, Asshoff M, et al. On-demand erythrocyte disposal and iron recycling requires transient macrophages in the liver. Nat Med. (2016) 22:945–51. doi: 10.1038/nm.4146

5. Gammella E, Buratti P, Cairo G, Recalcati S. Macrophages: central regulators of iron balance. Metallomics. (2014) 6:1336–45. doi: 10.1039/C4MT00104D

6. Scott CL, Zheng F, De Baetselier P, Martens L, Saeys Y, De Prijck S, et al. Bone marrow-derived monocytes give rise to self-renewing and fully differentiated Kupffer cells. Nat Commun. (2016) 7:10321. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10321

7. Lavin Y, Winter D, Blecher-Gonen R, David E, Keren-Shaul H, Merad M, et al. Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment. Cell. (2014) 159:1312–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.018

8. Krenkel O, Tacke F. Liver macrophages in tissue homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. (2017) 17:306–21. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.11

9. Dal-Secco D, Wang J, Zeng Z, Kolaczkowska E, Wong CH, Petri B, et al. A dynamic spectrum of monocytes arising from the in situ reprogramming of CCR2+ monocytes at a site of sterile injury. J Exp Med. (2015) 212:447–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141539

10. Terpstra V, van Berkel TJ. Scavenger receptors on liver Kupffer cells mediate the in vivo uptake of oxidatively damaged red blood cells in mice. Blood. (2000) 95:2157–63. doi: 10.1182/blood.V95.6.2157

11. Shi JL, Fujieda H, Kokubo Y, Wake K. Apoptosis of neutrophils and their elimination by Kupffer cells in rat liver. Hepatology. (1996) 24:1256–63. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240545

12. Crispe IN, Dao T, Klugewitz K, Mehal WZ, Metz DP. The liver as a site of T-cell apoptosis: graveyard, or krilling field? Immunol. Rev. (2000) 174:47–62. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.017412.x

13. Carlin LM, Stamatiades EG, Auffray C, Hanna RN, Glover L, Vizcay-Barrena G, et al. Nr4a1-dependent Ly6C(low) monocytes monitor endothelial cells and orchestrate their disposal. Cell. (2013) 153:362–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.010

14. Horst AK, Tiegs G, Diehl L. Contribution of macrophage efferocytosis to liver homeostasis and disease. Front Immunol. (2019) 10. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02670

15. Crispe IN. Immune tolerance in liver disease. Hepatology. (2014) 60:2109–17. doi: 10.1002/hep.27254

16. Heymann F, Peusquens J, Ludwig-Portugall I, Kohlhepp M, Ergen C, Niemietz P, et al. Liver inflammation abrogates immunological tolerance induced by Kupffer cells. Hepatology. (2015) 62:279–91. doi: 10.1002/hep.27793

17. Zigmond E, Samia-Grinberg S, Pasmanik-Chor M, Brazowski E, Shibolet O, Halpern Z, et al. Infiltrating monocyte-derived macrophages and resident kupffer cells display different ontogeny and functions in acute liver injury. J Immunol. (2014) 193:344–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400574

18. van Furth R, Cohn ZA. The origin and kinetics of mononuclear phagocytes. J Exp Med. (1968) 128:415–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.128.3.415

19. Mass E, Ballesteros I, Farlik M, Halbritter F, Gunther P, Crozet L, et al. Contribution of macrophage efferocytosis to liver homeostasis and disease. Science. (2016) 353:aaf4238. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4238

20. Soucie EL, Weng Z, Geirsdottir L, Molawi K, Maurizio J, Fenouil R, et al. Lineage-specific enhancers activate self-renewal genes in macrophages and embryonic stem cells. Science. (2016) 351:aad5510. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5510

21. Sawai CM, Babovic S, Upadhaya S, Knapp D, Lavin Y, Lau CM, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells are the major source of multilineage hematopoiesis in adult animals. Immunity. (2016) 45:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.08.007

22. Guilliams M, Scott CL. Does niche competition determine the origin of tissue-resident macrophages? Nat Rev Immunol. (2017) 17:451–60. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.42

23. Eaves CJ. Hematopoietic stem cells: concepts, definitions, and the new reality. Blood. (2015) 125:2605–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-570200

24. Auffray C, Fogg DK, Narni-Mancinelli E, Senechal B, Trouillet C, Saederup N, et al. CX3CR1+ CD115+ CD135+ common macrophage/DC precursors and the role of CX3CR1 in their response to inflammation. J Exp Med. (2009) 206:595–606. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081385

25. Liu K, Victora GD, Schwickert TA, Guermonprez P, Meredith MM, Yao K, et al. In vivo analysis of dendritic cell development and homeostasis. Science. (2009) 324:392–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1170540

26. Dai XM, Ryan GR, Hapel AJ, Dominguez MG, Russell RG, Kapp S, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood. (2002) 99:111–20. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.1.111

27. Wang M, Frasch SC, Li G, Feng D, Gao B, Xu L, et al. Role of gp91(phox) in hepatic macrophage programming and alcoholic liver disease. Hepatol Commun. (2017) 1:765–779. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1078

28. Wang M, You Q, Lor K, Chen F, Gao B, Ju C. Chronic alcohol ingestion modulates hepatic macrophage populations and functions in mice. J Leukoc Biol. (2014) 96:657–65. doi: 10.1189/jlb.6A0114-004RR

29. Ingersoll MA, Spanbroek R, Lottaz C, Gautier EL, Frankenberger M, Hoffmann R, et al. Comparison of gene expression profiles between human and mouse monocyte subsets. Blood. (2010) 115:e10–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235028

30. Xue J, Schmidt SV, Sander J, Draffehn A, Krebs W, Quester I, et al. Transcriptome-based network analysis reveals a spectrum model of human macrophage activation. Immunity. (2014) 40:274–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.006

31. Huebener P, Hernandez C, Schwabe RF. HMGB1 and injury amplification. Oncotarget. (2015) 6:23048–9. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5243

32. Chen RC, Hou W, Zhang QH, Kang R, Fan XG, Tang DL. Emerging role of high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) in liver diseases. Mol. Med. (2013) 19:357–66. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2013.00099

33. Huebener P, Pradere JP, Hernandez C, Gwak GY, Caviglia JM, Mu X, et al. The HMGB1/RAGE axis triggers neutrophil-mediated injury amplification following necrosis. J Clin Invest. (2015) 125:539–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI76887

34. Tsung A, Sahai R, Tanaka H, Nakao A, Fink MP, Lotze MT, et al. The nuclear factor HMGB1 mediates hepatic injury after murine liver ischemia-reperfusion. J Exp Med. (2005) 201:1135–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042614

35. Arrese M, Cabrera D, Kalergis AM, Feldstein AE. Innate immunity and inflammation in NAFLD/NASH. Dig Dis Sci. (2016) 61:1294–303. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4049-x

36. Li L, Chen L, Hu L, Liu Y, Sun HY, Tang J, et al. Nuclear factor high-mobility group box1 mediating the activation of Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in hepatocytes in the early stage of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Hepatology. (2011) 54:1620–30. doi: 10.1002/hep.24552

37. Martin-Murphy BV, Holt MP, Ju C. The role of damage associated molecular pattern molecules in acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. Toxicol Lett. (2010) 192:387–94. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.11.016

38. Wallin RP, Lundqvist A, More SH, von Bonin A, Kiessling R, Ljunggren HG. Heat-shock proteins as activators of the innate immune system. Trends Immunol. (2002) 23:130–5. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(01)02168-8

39. Fiorucci S, Biagioli M, Zampella A, Distrutti E. Bile acids activated receptors regulate innate immunity. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1853. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01853

40. Perino A, Schoonjans K. TGR5 and Immunometabolism: Insights from Physiology and Pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2015) 36:847–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.08.002

41. Reich M, Klindt C, Deutschmann K, Spomer L, Haussinger D, Keitel V. Role of the G protein-coupled bile acid receptor TGR5 in liver damage. Dig Dis. (2017) 35:235–40. doi: 10.1159/000450917

42. Lou G, Ma X, Fu X, Meng Z, Zhang W, Wang YD, et al. GPBAR1/TGR5 mediates bile acid-induced cytokine expression in murine Kupffer cells. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e93567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093567

43. Wang YD, Chen WD, Yu D, Forman BM, Huang W. The G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor, Gpbar1 (TGR5), negatively regulates hepatic inflammatory response through antagonizing nuclear factor kappa light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) in mice. Hepatology. (2011) 54:1421–32. doi: 10.1002/hep.24525

44. Huang H, Evankovich J, Yan W, Nace G, Zhang L, Ross M, et al. Endogenous histones function as alarmins in sterile inflammatory liver injury through Toll-like receptor 9 in mice. Hepatology. (2011) 54:999–1008. doi: 10.1002/hep.24501

45. Pan J, Ou Z, Cai C, Li P, Gong J, Ruan XZ, et al. Fatty acid activates NLRP3 inflammasomes in mouse Kupffer cells through mitochondrial DNA release. Cell Immunol. (2018) 332:111–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.08.006

46. Rao R. Endotoxemia and gut barrier dysfunction in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. (2009) 50:638–44. doi: 10.1002/hep.23009

47. Rivera CA, Adegboyega P, van Rooijen N, Tagalicud A, Allman M, Wallace M. Toll-like receptor-4 signaling and Kupffer cells play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. (2007) 47:571–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.019

48. Emontzpohl C, Stoppe C, Theissen A, Beckers C, Neumann UP, Lurje G, et al. The role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in remote ischemic conditioning induced hepatoprotection in a rodent model of liver transplantation. Shock. (2019) 52:e124–e34. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001307

49. Bernal W, Auzinger G, Dhawan A, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. Lancet. (2010) 376:190–201. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60274-7

50. Sehgal R, Patra S, David P, Vyas A, Khanam A, Hissar S, et al. Impaired monocyte-macrophage functions and defective Toll-like receptor signaling in hepatitis E virus-infected pregnant women with acute liver failure. Hepatology. (2015) 62:1683–96. doi: 10.1002/hep.28143

51. Zhang M, Xu S, Han Y, Cao X. Apoptotic cells attenuate fulminant hepatitis by priming Kupffer cells to produce interleukin-10 through membrane-bound TGF-beta. Hepatology. (2011) 53:306–16. doi: 10.1002/hep.24029

52. Ramachandran P, Pellicoro A, Vernon MA, Boulter L, Aucott RL, Ali A, et al. Differential Ly-6C expression identifies the recruited macrophage phenotype, which orchestrates the regression of murine liver fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2012) 109:E3186–95. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119964109

53. Boulter L, Govaere O, Bird TG, Radulescu S, Ramachandran P, Pellicoro A, et al. Macrophage-derived Wnt opposes notch signaling to specify hepatic progenitor cell fate in chronic liver disease. Nat Med. (2012) 18:572–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2667

54. Alisi A, Carsetti R, Nobili V. Pathogen- or damage-associated molecular patterns during nonalcoholic fatty liver disease development. Hepatology. (2011) 54:1500–2. doi: 10.1002/hep.24611

55. Evankovich J, Cho SW, Zhang R, Cardinal J, Dhupar R, Zhang L, et al. High mobility group box 1 release from hepatocytes during ischemia and reperfusion injury is mediated by decreased histone deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem. (2010) 285:39888–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.128348

56. Mihm S. Danger-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs): Molecular Triggers for Sterile Inflammation in the Liver. Int J Mol Sci. (2018) 19:E3104. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103104

57. Shi Y, Evans JE, Rock KL. Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature. (2003) 425:516–21. doi: 10.1038/nature01991

58. Antoine DJ, Williams DP, Kipar A, Jenkins RE, Regan SL, Sathish JG, et al. High-mobility group box-1 protein and keratin-18, circulating serum proteins informative of acetaminophen-induced necrosis and apoptosis in vivo. Toxicol Sci. (2009) 112:521–31. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp235

59. Li M, Cai SY, Boyer JL. Mechanisms of bile acid mediated inflammation in the liver. Mol Aspects Med. (2017) 56l:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2017.06.001

60. Kariko K, Ni H, Capodici J, Lamphier M, Weissman D. mRNA is an endogenous ligand for Toll-like receptor 3. J Biol Chem. (2004) 279:12542–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310175200

61. Cavassani KA, Ishii M, Wen H, Schaller MA, Lincoln PM, Lukacs NW, et al. TLR3 is an endogenous sensor of tissue necrosis during acute inflammatory events. J Exp Med. (2008) 205:2609–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081370

62. Calderwood SK, Gong J, Murshid A. Extracellular HSPs: the complicated roles of extracellular HSPs in immunity. Front Immunol. (2016) 7:159. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00159

63. Nomura J, So A, Tamura M, Busso N. Intracellular ATP decrease mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation upon nigericin and crystal stimulation. J Immunol. (2015) 195:5718–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402512

64. Baron L, Gombault A, Fanny M, Villeret B, Savigny F, Guillou N, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by nanoparticles through ATP, ADP and adenosine. Cell Death Dis. (2015) 6:e1629. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.576

65. Chang WJ, Toledo-Pereyra LH. Toll-like receptor signaling in liver ischemia and reperfusion. J Invest Surg. (2012) 25:271–7. doi: 10.3109/08941939.2012.687802

66. Gao B, Jeong WI, Tian Z. Liver: an organ with predominant innate immunity. Hepatology. (2008) 47:729–36. doi: 10.1002/hep.22034

67. Parlesak A, Schafer C, Schutz T, Bode JC, Bode C. Increased intestinal permeability to macromolecules and endotoxemia in patients with chronic alcohol abuse in different stages of alcohol-induced liver disease. J Hepatol. (2000) 32:742–7. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80242-1

68. Iimuro Y, Gallucci RM, Luster MI, Kono H, Thurman RG. Antibodies to tumor necrosis factor alfa attenuate hepatic necrosis and inflammation caused by chronic exposure to ethanol in the rat. Hepatology. (1997) 26:1530–37. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260621

69. Zhong Z, Connor H, Stachlewitz RF, VonFrankenberg M, Mason RP, Lemasters JJ, et al. Role of free radicals in primary nonfunction of marginal fatty grafts from rats treated acutely with ethanol. Mol Pharmacol. (1997) 52:912–19. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.5.912

70. Ju C, Liangpunsakul S. Role of hepatic macrophages in alcoholic liver disease. J Investig Med. (2016) 64:1075–7. doi: 10.1136/jim-2016-000210

71. Thuy S, Ladurner R, Volynets V, Wagner S, Strahl S, Konigsrainer A, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in humans is associated with increased plasma endotoxin and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 concentrations and with fructose intake. J Nutr. (2008) 138:1452–5. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.8.1452

72. Baffy G. Kupffer cells in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the emerging view. J Hepatol. (2009) 51:212–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.03.008

73. Faure-Dupuy S, Delphin M, Aillot L, Dimier L, Lebosse F, Fresquet J, et al. Hepatitis B virus-induced modulation of liver macrophage function promotes hepatocyte infection. J Hepatol. (2019) 71:1086–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.032

74. Negash AA, Ramos HJ, Crochet N, Lau DT, Doehle B, Papic N, et al. IL-1beta production through the NLRP3 inflammasome by hepatic macrophages links hepatitis C virus infection with liver inflammation and disease. PLoS Pathog. (2013) 9:e1003330. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003330

75. Dragomir AC, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Macrophage activation by factors released from acetaminophen-injured hepatocytes: potential role of HMGB1. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. (2011) 253:170–7. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.04.003

76. McDonald KA, Huang H, Tohme S, Loughran P, Ferrero K, Billiar T, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) antagonist eritoran tetrasodium attenuates liver ischemia and reperfusion injury through inhibition of high-mobility group box protein B1 (HMGB1) signaling. Mol Med. (2015) 20:639–48. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00076

77. Ganz M, Szabo G. Immune and inflammatory pathways in NASH. Hepatol Int. (2013) 7(Suppl 2):771–81. doi: 10.1007/s12072-013-9468-6

78. McDonald B, Jenne CN, Zhuo L, Kimata K, Kubes P. Kupffer cells and activation of endothelial TLR4 coordinate neutrophil adhesion within liver sinusoids during endotoxemia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2013) 305:G797–806. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00058.2013

79. Trefts E, Gannon M, Wasserman DH. The liver. Curr Biol. (2017) 27:R1147–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.019

80. Tsuchida T, Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastro Hepat. (2017) 14:397–411. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.38

81. Wan J, Benkdane M, Alons E, Lotersztajn S, Pavoine C. M2 kupffer cells promote hepatocyte senescence: an IL-6-dependent protective mechanism against alcoholic liver disease. Am J Pathol. (2014) 184:1763–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.02.014

82. Momen-Heravi F, Bala S, Kodys K, Szabo G. Exosomes derived from alcohol-treated hepatocytes horizontally transfer liver specific miRNA-122 and sensitize monocytes to LPS. Sci Rep. (2015) 5:9991. doi: 10.1038/srep09991

83. Verma VK, Li H, Wang R, Hirsova P, Mushref M, Liu Y, et al. Alcohol stimulates macrophage activation through caspase-dependent hepatocyte derived release of CD40L containing extracellular vesicles. J Hepatol. (2016) 64:651–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.020

84. Park J, Tadlock L, Gores GJ, Patel T. Inhibition of interleukin 6-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase activation attenuates growth of a cholangiocarcinoma cell line. Hepatology. (1999) 30:1128–33. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300522

85. Xiao Y, Wang J, Yan W, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Zhou K, et al. Dysregulated miR-124 and miR-200 expression contribute to cholangiocyte proliferation in the cholestatic liver by targeting IL-6/STAT3 signalling. J Hepatol. (2015) 62:889–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.033

86. Weiskirchen R, Tacke F. Cellular and molecular functions of hepatic stellate cells in inflammatory responses and liver immunology. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. (2014) 3:344–63.

87. Mochizuki A, Pace A, Rockwell CE, Roth KJ, Chow A, O'Brien KM, et al. Hepatic stellate cells orchestrate clearance of necrotic cells in a hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha-dependent manner by modulating macrophage phenotype in mice. J Immunol. (2014) 192:3847–57. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303195

88. Melgar-Lesmes P, Edelman ER. Monocyte-endothelial cell interactions in the regulation of vascular sprouting and liver regeneration in mouse. J Hepatol. (2015) 63:917–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.05.011

89. Selzner N, Selzner M, Odermatt B, Tian Y, Van Rooijen N, Clavien PA. ICAM-1 triggers liver regeneration through leukocyte recruitment and Kupffer cell-dependent release of TNF-alpha/IL-6 in mice. Gastroenterology. (2003) 124:692–700. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50098

90. Saha B, Momen-Heravi F, Kodys K, Szabo G. MicroRNA cargo of extracellular vesicles from alcohol-exposed monocytes signals naive monocytes to differentiate into M2 macrophages. J Biol Chem. (2016) 291:149–59. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.694133

91. Prame Kumar K, Nicholls AJ, Wong CHY. Partners in crime: neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages in inflammation and disease. Cell Tissue Res. (2018) 371:551–65. doi: 10.1007/s00441-017-2753-2

92. Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. (2007) 25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711

93. Tang T, Sui Y, Lian M, Li Z, Hua J. Pro-inflammatory activated Kupffer cells by lipids induce hepatic NKT cells deficiency through activation-induced cell death. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e81949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081949

94. You Q, Cheng L, Kedl RM, Ju C. Mechanism of T cell tolerance induction by murine hepatic Kupffer cells. Hepatology. (2008) 48:978–90. doi: 10.1002/hep.22395

95. Grohmann U, Fallarino F, Bianchi R, Belladonna ML, Vacca C, Orabona C, et al. IL-6 inhibits the tolerogenic function of CD8 alpha+ dendritic cells expressing indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J Immunol. (2001) 167:708–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.708

96. Bissell DM, Wang SS, Jarnagin WR, Roll FJ. Cell-specific expression of transforming growth factor-beta in rat liver. Evidence for autocrine regulation of hepatocyte proliferation. J Clin Invest. (1995) 96:447–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI118055

97. Knolle PA, Uhrig A, Protzer U, Trippler M, Duchmann R, zum Buschenfelde KHM, et al. Interleukin-10 expression is autoregulated at the transcriptional level in human and murine Kupffer cells. Hepatology. (1998) 27:93–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270116

98. Chen GS, Qi HZ. Effect of Kupffer cells on immune tolerance in liver transplantation. Asian Pac J Trop Med. (2012) 5:970–972. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60184-9

99. Li M, Sun R, Xu L, Yin WW, Chen YY, Zheng XD, et al. Kupffer cells support hepatitis B virus-mediated CD8(+) T cell exhaustion via hepatitis B core antigen-TLR2 interactions in mice. J Immunol. (2015) 195:3100–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500839

100. Liu J, Fan L, Yu H, Zhang J, He Y, Feng D, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress causes liver cancer cells to release exosomal miR-23a-3p and up-regulate programmed death ligand 1 expression in macrophages. Hepatology. (2019) 70:241–58. doi: 10.1002/hep.30607

101. Benechet AP, De Simone G, Di Lucia P, Cilenti F, Barbiera G, Le Bert N, Fumagalli V, et al. Dynamics and genomic landscape of CD8(+) T cells undergoing hepatic priming. Nature. (2019) 574:200–5. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1620-6

102. Wen Y, Feng D, Wu H, Liu W, Li H, Wang F, et al. Defective initiation of liver regeneration in osteopontin-deficient mice after partial hepatectomy due to insufficient activation of IL-6/Stat3 pathway. Int J Biol Sci. (2015) 11:1236–47. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.12118

103. Cai X, Li Z, Zhang Q, Qu Y, Xu M, Wan X, et al. CXCL6-EGFR-induced Kupffer cells secrete TGF-beta1 promoting hepatic stellate cell activation via the SMAD2/BRD4/C-MYC/EZH2 pathway in liver fibrosis. J Cell Mol Med. (2018) 22:5050–61. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13787

104. Nieto N. Oxidative-stress and IL-6 mediate the fibrogenic effects of [corrected] Kupffer cells on stellate cells. Hepatology. (2006) 44:1487–501. doi: 10.1002/hep.21427

105. Mak A, Uetrecht J. Involvement of CCL2/CCR2 macrophage recruitment in amodiaquine-induced liver injury. J Immunotoxicol. (2019) 16:28–33. doi: 10.1080/1547691X.2018.1516014

106. Cui KL, Yan GX, Xu CF, Chen YY, Wang J, Zhou RB, et al. Invariant NKT cells promote alcohol-induced steatohepatitis through interleukin-1 beta in mice. J Hepatology. (2015) 62:1311–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.027

107. Hanschen M, Zahler S, Krombach F, Khandoga A. Reciprocal activation between CD4(+) T cells and Kupffer cells during hepatic ischemia-reperfusion. Transplantation. (2008) 86:710–8. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181821aa7

108. Tacke F, Weiskirchen R. Liver immunology: new perspectives. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. (2014) 3:330. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2014.11.07

109. Terada M, Horisawa K, Miura S, Takashima Y, Ohkawa Y, Sekiya S, et al. Kupffer cells induce Notch-mediated hepatocyte conversion in a common mouse model of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:34691. doi: 10.1038/srep34691

110. Elsegood CL, Chan CW, Degli-Esposti MA, Wikstrom ME, Domenichini A, Lazarus K, et al. Kupffer cell-monocyte communication is essential for initiating murine liver progenitor cell-mediated liver regeneration. Hepatology. (2015) 62:1272–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.27977

111. Jeong WI, Park O, Radaeva S, Gao B. STAT1 inhibits liver fibrosis in mice by inhibiting stellate cell proliferation and stimulating NK cell cytotoxicity. Hepatology. (2006) 44:1441–51. doi: 10.1002/hep.21419

112. Deaciuc IV, Bagby GJ, Lang CH, Spitzer JJ. Hyaluronic acid uptake by the isolated, perfused rat liver: an index of hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cell function. Hepatology. (1993) 17:266–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840170217

113. Gregory SH, Cousens LP, van Rooijen N, Dopp EA, Carlos TM, Wing EJ. Complementary adhesion molecules promote neutrophil-Kupffer cell interaction and the elimination of bacteria taken up by the liver. J Immunol. (2002) 168:308–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.308

114. Wu X, Sun R, Chen Y, Zheng X, Bai L, Lian Z, et al. Oral ampicillin inhibits liver regeneration by breaking hepatic innate immune tolerance normally maintained by gut commensal bacteria. Hepatology. (2015) 62:253–64. doi: 10.1002/hep.27791

Keywords: Kupffer cells, monocyte-derived macrophages, liver injury, microenvironmental cues, cellular crosstalk

Citation: Shan Z and Ju C (2020) Hepatic Macrophages in Liver Injury. Front. Immunol. 11:322. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00322

Received: 12 December 2019; Accepted: 10 February 2020;

Published: 17 April 2020.

Edited by:

Ralf Weiskirchen, RWTH Aachen University, GermanyReviewed by:

Dechun Feng, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), United StatesLynette Beattie, The University of Melbourne, Australia

Manabu Kinoshita, National Defense Medical College, Japan

Copyright © 2020 Shan and Ju. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cynthia Ju, Y2hhbmdxaW5nLmp1QHV0aC50bWMuZWR1

Zhao Shan

Zhao Shan Cynthia Ju

Cynthia Ju