- 1Department of Trauma Orthopedics, Shenzhen Longhua District People’s Hospital, Shenzhen, China

- 2The Second Clinical Medical College of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China

- 3The First Clinical Medical College of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China

- 4Department of Bone and Joint Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China

- 5Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease characterized by synovial inflammation, cartilage degradation, and subchondral bone remodeling. Synovial macrophages, particularly their polarization into pro-inflammatory M1 or anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes, play a pivotal role in OA pathogenesis. M1 macrophages drive synovitis, oxidative stress, and cartilage catabolism by secreting cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α) and matrix-degrading enzymes (MMPs, ADAMTS-5), while M2 macrophages promote tissue repair via TGF-β and IL-10. Emerging therapeutic strategies, such as macrophage depletion, mTOR/SIRT1 modulation, and M2 polarization, demonstrate potential in rebalancing the M1/M2 ratio to attenuate OA progression. However, translating these macrophage-targeted strategies into clinical practice remains challenging due to difficulties in achieving subtype-specific targeting, avoiding off-target immune effects, and ensuring consistent therapeutic efficacy across patient populations. However, challenges remain in achieving subtype-specific targeting and translating preclinical findings to clinical applications. This review summarizes current knowledge and provides valuable insights for advancing OA management strategies, underscoring macrophages as promising therapeutic targets in osteoarthritis.

1 Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA), recognized as the most common degenerative joint disease, is characterized by complex pathological alterations involving multiple joint structures including articular cartilage, subchondral bone, synovial membrane, ligaments, and periarticular musculature (1–3). A critical pathological hallmark of OA is synovial inflammation (4–6), with accumulating evidence indicating that the severity of synovitis closely parallels disease progression (7–9). Synovitis, defined as inflammatory changes in the synovial membrane, manifests histologically through distinct features including synovial cell hyperplasia, angiogenesis, and infiltration of inflammatory cells (10–12).

Macrophages serve as versatile immune regulators that participate in both innate immune responses and tissue homeostasis, playing pivotal roles in host defense mechanisms and the maintenance of physiological balance (13). Within this inflammatory microenvironment, macrophages constitute the predominant immune cell population. These cells actively participate in OA pathogenesis through the sustained secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix-degrading enzymes, thereby driving disease exacerbation and promoting joint tissue destruction (14, 15). Therefore, an in-depth understanding of the role of synovial macrophages in the initiation and progression of OA is of critical importance. Importantly, among the various immune cells implicated in OA, synovial macrophages represent a particularly attractive therapeutic target due to their numerical dominance, plastic phenotypic switching capacity, and ability to orchestrate both destructive and reparative processes in the joint microenvironment (16). Unlike lymphocytes or neutrophils, which often act as downstream effectors, macrophages act as upstream modulators of inflammation, matrix degradation, and chondrocyte fate. Their dual polarization into pro-inflammatory (M1) and anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotypes provides a therapeutically exploitable axis to restore immune balance and promote tissue repair (17, 18). As such, targeting macrophage polarization offers a more direct and dynamic strategy for modulating joint inflammation and structural damage compared to other immune pathways.

2 Composition, functional roles, and phenotypic characteristics of synovial macrophages

2.1 Heterogeneity and functional significance of synovial macrophages

The pivotal role of macrophages in OA synovitis has been firmly established since early studies (19, 20). Athanasou et al (21). first identified macrophage markers (CD11b, CD14, CD16, CD68) in OA synovium, though these did not define activation states. Subsequent work by Haywood et al (22)., Benito et al (23)., and Bondeson et al (24). demonstrated markedly increased macrophage infiltration compared with healthy synovium, a finding reproduced in multiple OA animal models (25, 26). Manferdini et al (27). further revealed heterogeneous macrophage subsets (CD14, CD16, CD68, CD80, CD163), emphasizing phenotypic diversity. Polarization profiling has yielded variable results: Van den Bosch et al (28). reported simultaneous elevation of M1 (CD86, CCL3, CCL5) and M2 (CD206, IL−10, IL−1Ra) markers in end−stage OA, whereas Zhang et al (26). observed a pronounced M1 (iNOS +) predominance and M2 (CD206 +) reduction in human and murine OA models. ScRNA‐Seq Revealed the macrophages could be further categorized into two subclusters: C0 and C1. The relative proportion of C0 and C1 was dramatically elevated in the synovium of patients with diabetic OA compared to those with normal synovium (29).

Recent phenotyping advances identified folate receptor−β (FR−β) as a marker of pro−inflammatory monocytes (CD14high CD16−) (30). FOLR2 + tissue−resident macrophages (TRMs) localize perivascularly and interact with CD8 + T cells (31). This finding enabled non−invasive visualization of macrophage activation via ¹¹¹InCl 3−DTPA−folate SPECT imaging in rat OA models (32), revealing transient activation peaks in mono−iodoacetate−induced OA and sustained activity up to 12 weeks post−ACL transection. De Visser et al (32). further reported a 28.4% rise in FR−β + macrophages under high−fat diet conditions in a groove model, concentrated within synovial and subchondral bone regions. Clinical investigations have strengthened the association between macrophage activation and OA progression. Daghestani et al. (33) established significant correlations between synovial fluid levels of CD14/CD163 and SPECT-detected macrophage activity, with CD14 levels particularly associated with radiographic joint space narrowing, osteophyte formation, and clinical pain scores. Interestingly, CD163 as an M2 marker showed specific association with osteophyte progression, suggesting a potential role for M2 macrophages in this aspect of OA pathogenesis. Kraus et al. (25) extended these findings using 99Tc-m-EC20 (Etarfolatide) imaging in human knee OA, detecting activated macrophages in 76% of symptomatic knees with strong correlations to both pain severity and radiographic disease stage. Importantly, FR-β+ macrophages were identified in multiple OA-affected joints (fingers, shoulder, ankle), with their presence consistently associated with pain symptoms.

2.2 Phenotypic features and functional roles of synovial macrophages

The synovium, a specialized vascular connective tissue that lines the articular capsule, plays a pivotal role in maintaining joint homeostasis by enveloping intra-articular structures (34, 35). The pathological accumulation of macrophages within the synovial lining serves as a diagnostic indicator of synovitis (16, 36), while simultaneously contributing to synovial tissue homeostasis (37). In OA, activated synovial macrophages have been implicated in the pathogenesis of intra-synovial inflammation (38). These cells exhibit remarkable plasticity, undergoing polarization into distinct functional phenotypes in response to local cytokine gradients—a process termed M1/M2 polarization (39). Classical activation (M1 phenotype) occurs following exposure to pro-inflammatory mediators including IFN-γ, LPS, and TNF-α, resulting in enhanced secretion of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-12) and enzymes (COX-2), coupled with diminished IL-10 production (37). Conversely, alternative activation (M2 phenotype) is induced by Th2-derived cytokines (IL-4, IL-13), yielding anti-inflammatory macrophages that promote tissue repair. The M2 population can be further classified into functionally distinct subsets (M2a, M2b, M2c), all participating in extracellular matrix remodeling (40). Single-cell RNA sequencing studies have revealed a spectrum of macrophage activation profiles that do not conform strictly to the M1 or M2 paradigm, indicating that this polarization continuum demonstrates the dynamic adaptability of macrophages to microenvironmental cues. Emerging evidence highlights the prognostic significance of the synovial M1/M2 polarization balance in OA progression. Topoluk et al. (41) employed an innovative OA cartilage-synovium coculture system to demonstrate that synovial macrophage depletion significantly reduced the M1/M2 polarization ratio, concurrently decreasing IL-13 and MMP-13 expression while mitigating cartilage degradation. Complementary clinical findings by Liu et al. (42) revealed elevated M1/M2 polarization ratios in both synovial fluid and peripheral blood of knee OA patients, with positive correlations observed between this ratio and radiographic disease severity, suggesting its utility as a potential biomarker for OA staging.

3 Role of synovial macrophage polarization in OA pathogenesis

3.1 Synovial inflammation and OA progression

Synovial inflammation serves as a critical initiator of OA, with synovial macrophages, particularly the M1 phenotype, acting as central effectors in disease progression. This inflammatory response is marked by persistent low-grade inflammation, excessive MMP activity, and upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (43). Notably, synovitis often precedes overt cartilage degradation, emphasizing its role as an early pathological hallmark (44). Histological features include synovial lining hyperplasia, leukocyte infiltration, and aberrant angiogenesis (6, 45). Among these cellular changes, M1-polarized macrophages emerge as central mediators of synovial inflammation. Upon activation, these macrophages release a cascade of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and pain-inducing neuropeptides, while simultaneously exacerbating oxidative stress and inducing mitochondrial dysfunction through enhanced autophagy (46).

3.1.1 Oxidative stress regulation in OA

Under normal physiological conditions, reactive oxygen species (ROS) serve as critical signaling molecules involved in chondrocyte apoptosis regulation, gene expression modulation, and extracellular matrix (ECM) homeostasis maintenance (47, 48). However, pathological oxidative stress occurs when ROS generation surpasses the antioxidant defense capacity, resulting in structural damage to cellular components and articular tissues (49). Mitochondrial dysfunction is a key contributor to excessive ROS accumulation, which further disrupts intracellular signaling cascades and amplifies inflammatory responses (50). Elevated ROS levels exhibit a strong correlation with M1 macrophage infiltration in OA synovium (51). These classically activated macrophages secrete pro-inflammatory mediators, including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, TNF-α, ROS, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which collectively exacerbate synovial inflammation (17, 52, 53). The resulting oxidative stress, driven by ROS and nitric oxide (NO), accelerates chondrocyte apoptosis and cartilage matrix degradation (47). Mechanistically, excessive ROS inhibit the protective PI3K/Akt pathway while activating pro-inflammatory MEK/ERK signaling, further amplifying the inflammatory cascade (47, 54). Zheng et al. (55) demonstrated that populnin alleviates oxidative stress in OA synovium by suppressing NF-κB activation, reducing IL-1β-induced NO production, and downregulating iNOS expression. Macrophage polarization significantly influences cellular redox balance through metabolic reprogramming. M1 macrophages predominantly utilize glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway, enhancing ROS and NO generation and perpetuating inflammation. In contrast, M2 macrophages exhibit increased oxidative phosphorylation and express arginase-1 (Arg1), contributing to ROS scavenging and tissue repair (56). Notably, ROS also function as intracellular signaling molecules that reinforce M1 polarization by activating NF-κB and MAPK pathways, creating a self-sustaining inflammatory loop in OA synovitis (57–59).

3.1.2 Mitophagy regulation in OA

Mitochondria serve as the primary organelles for oxidative phosphorylation in eukaryotic cells, playing a pivotal role in cellular energy metabolism (60). Mitophagy, the selective autophagy of damaged mitochondria, is a critical mechanism for maintaining mitochondrial quality control and cellular homeostasis. However, dysregulation of this process can lead to pathological outcomes, as excessive mitophagy may disrupt intracellular balance and trigger apoptotic or necrotic cell death (61). Recent studies have elucidated the relationship between mitophagy and macrophage polarization. Recent studies demonstrated that LPS-stimulated macrophages polarized toward the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype exhibit elevated intracellular ROS levels, accompanied by mitochondrial dysfunction and marked upregulation of mitophagy-related proteins, including Beclin-1 and PINK1. This enhanced mitophagy activity contributes to the amplification of inflammatory responses. Notably, intervention with 2-deoxy-D-glucose was found to attenuate ROS generation during M1 polarization, thereby reducing the fusion of impaired mitochondria with lysosomes and subsequently suppressing excessive mitophagy, which may offer a potential strategy for mitigating inflammation (62, 63). Conversely, emerging evidence suggests that mitophagy modulation can reciprocally influence macrophage polarization states. For instance, stabilization of mitochondrial membrane potential and pharmacological inhibition of mitophagy have been shown to promote the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, thereby alleviating synovial inflammation (64).

3.2 Effects on cartilage

Cartilage, an avascular and aneural hyaline tissue, forms the articular surface of bones and is essential for smooth joint movement (65). Mechanical stress-induced cartilage injury triggers chondrocytes and macrophages to release MMPs, which degrade cartilage ECM and exacerbate OA progression (66). The pathological mechanisms of OA involve the imbalance between ECM synthesis and degradation due to elevated catabolic enzyme activity, and chondrocyte apoptosis and cellular senescence. Notably, modulating macrophage polarization, by enhancing the M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype or suppressing the M1 pro-inflammatory response, can promote cartilage repair, restore tissue homeostasis, and mitigate OA progression (67, 68).

3.2.1 Impact on chondrocyte anabolic and catabolic processes

Macrophage-chondrocyte crosstalk via paracrine signaling plays a pivotal role in OA pathogenesis. Activated synovial macrophages release pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6, which disrupt the chondrocyte microenvironment. These cytokines upregulate MMPs, leading to the breakdown of key ECM components such as type II collagen and aggrecan (69). Importantly, ECM degradation products act as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), further activating macrophages and perpetuating a self-sustaining cycle of synovial inflammation and cartilage destruction. Experimental evidence highlights the detrimental effects of M1 macrophages on chondrocyte function. Samavedi et al. (70) utilized a 3D co-culture model to demonstrate that chondrocytes exposed to LPS-polarized M1 macrophages exhibited significantly increased secretion of MMPs and inflammatory mediators (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IFN-γ). Furthermore, Zhang et al. (26) identified a novel mechanism wherein M1 macrophage polarization exacerbates OA through chondrocyte-derived R-spondin 2 (Rspo2), which activates β-catenin signaling and amplifies cartilage catabolism.

3.2.2 Impact on chondrocyte apoptosis

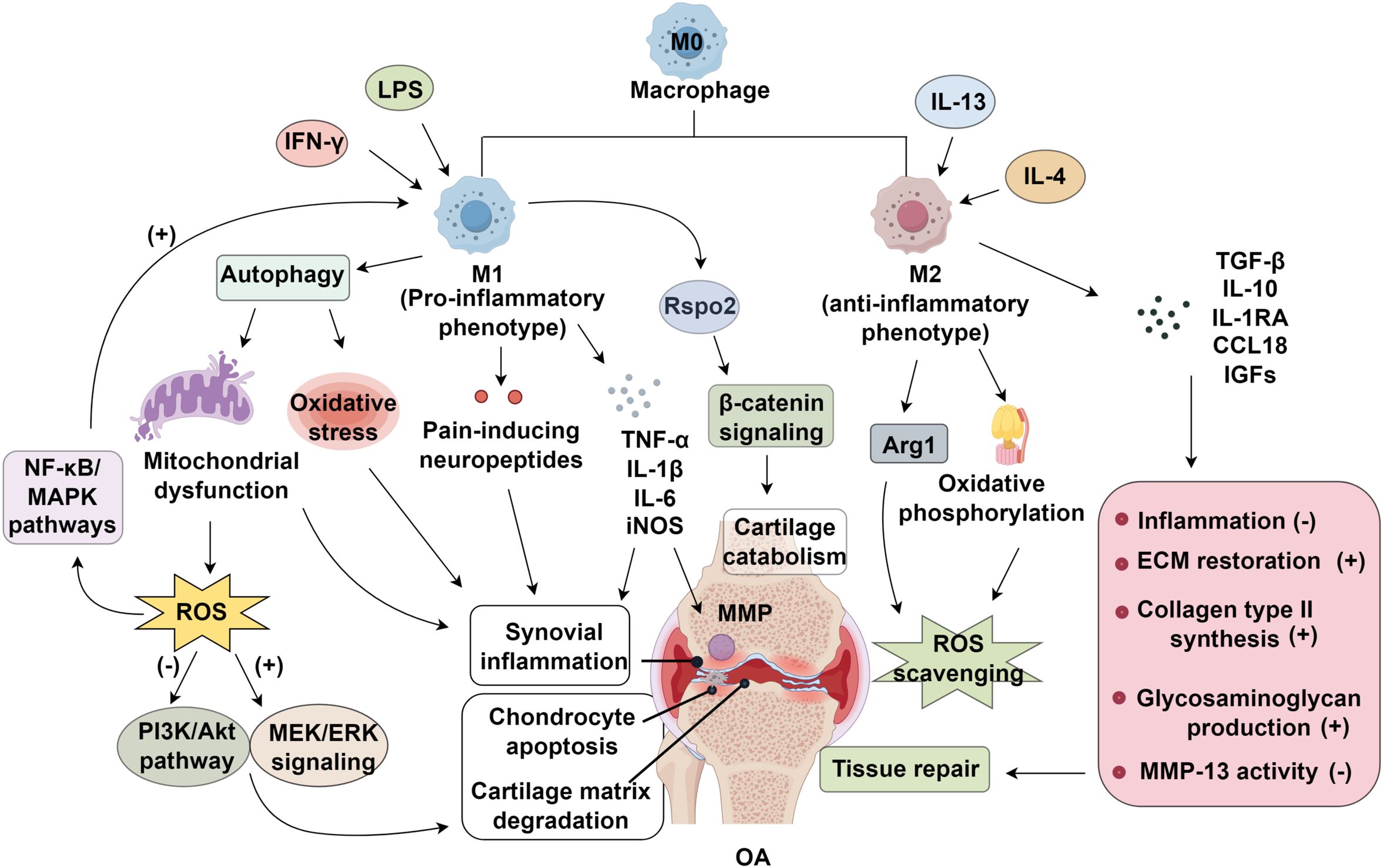

Growing research highlights the critical role of chronic low-grade synovial inflammation in cartilage degradation, where synovial macrophage polarization serves as a key mediator in OA progression (71). Pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages exacerbate OA pathology by promoting chondrocyte apoptosis, inducing cellular hypertrophy, and facilitating ECM degradation, ultimately leading to cartilage destruction (72). Experimental evidence suggests that targeted depletion of synovial macrophages reduces the M1/M2 ratio, suppresses IL-1 and MMP-13 expression, and mitigates cartilage damage (41). Mechanistically, M1-polarized macrophages in OA synovial tissue release pro-inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α and IL-1β, alongside MMPs, which collectively accelerate ECM breakdown and drive chondrocyte apoptosis (6). Among these cytokines, IL-1β plays a central role in chondrocyte apoptosis by activating the NF-κB and MAPK signaling cascades. Key components of these pathways—such as p50, p52, Rel proteins (Rel, Rel A, Rel B), p38, JNK, and ERK—regulate critical cellular processes, including chondrocyte proliferation, differentiation, and programmed cell death (73, 74). Pharmacological interventions targeting these pathways, such as paeoniflorin, have demonstrated therapeutic potential by modulating the Bax/Bcl-2/Caspase-3 axis and attenuating IL-1β-induced chondrocyte apoptosis (75). In contrast, M2 macrophages exhibit chondroprotective effects by promoting an anti-inflammatory microenvironment and facilitating cartilage repair. Dai et al. (76) demonstrated that type II collagen stimulates M2 polarization, which in turn suppresses chondrocyte apoptosis and hypertrophy while supporting the regeneration of damaged cartilage. This reparative function is partly mediated by TGF-β, a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine that enhances chondrogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) (67). Additionally, M2 macrophages secrete IL-10, IL-1RA, and CCL18, which counteract inflammation, alongside pro-chondrogenic factors such as insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) (77, 78). These macrophages also contribute to ECM restoration by upregulating collagen type II synthesis, enhancing glycosaminoglycan production, and inhibiting MMP-13 activity (79). Beyond direct paracrine effects, macrophage polarization influences chondrocyte fate through modulation of key signaling pathways, including TGF-β, JNK, Akt, NF-κB, and β-catenin. These interactions create a feedback loop wherein ECM degradation further skews macrophage polarization toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype, perpetuating a cycle of inflammation and cartilage deterioration (80) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mechanisms of synovial macrophage polarization in osteoarthritis (OA). Pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages induced by IFN-γ and LPS promote oxidative stress, ROS accumulation, and NF-κB/MAPK activation, driving synovial inflammation and cartilage catabolism. In contrast, IL-4/IL-13–induced M2 macrophages enhance ROS scavenging, ECM restoration, and cartilage repair through Arg1 and β-catenin signaling, thereby suppressing inflammation and promoting tissue regeneration. LPS; IGFs, insulin-like growth factors; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; OA, osteoarthritis; MEK, methyl Ethyl Ketone; ERK, Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; AKT, also known as protein kinase B (PKB); ECM, extracellular matrix.

3.3 Impact on chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells

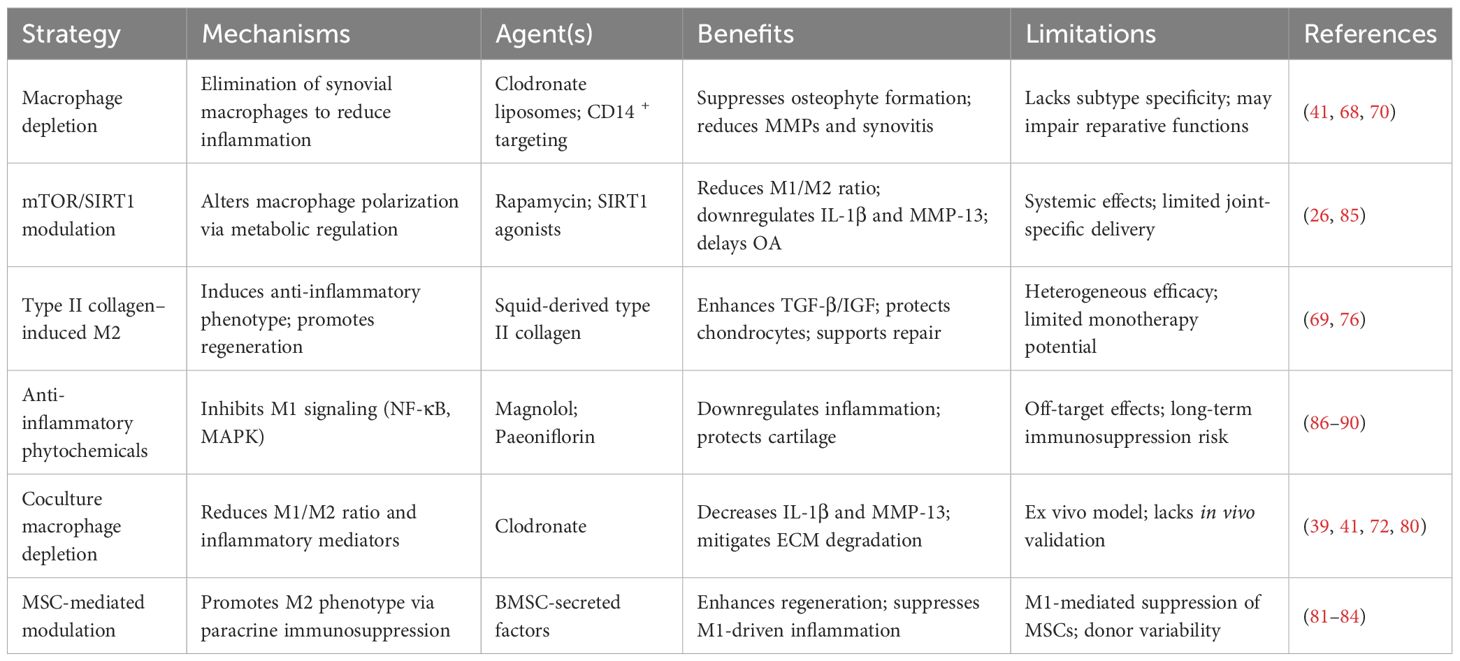

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), as multipotent stromal cells, are widely distributed in diverse tissues such as bone marrow, skeletal muscle, periosteum, and trabecular bone (81, 82). Notably, BMSCs exhibit significant immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties, which contribute to immune suppression and tolerance induction through the downregulation of pro-inflammatory responses. Additionally, BMSCs demonstrate considerable regenerative potential in cartilage repair (83). In the context of OA, BMSCs are recruited to injured joint tissues, where they secrete an array of bioactive molecules, including chemokines, cytokines, and growth factors. These factors play a crucial role in promoting M2 macrophage polarization, thereby facilitating tissue regeneration (67). Furthermore, MSCs exert a dual regulatory effect on macrophage polarization: they suppress the activation of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages while enhancing the transition to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes. Conversely, M1 macrophages negatively influence MSC functionality by impairing their proliferation and viability, exacerbating inflammatory responses, and accelerating cartilage matrix degradation (83). Supporting this, Fahy et al. demonstrated that M1 macrophages significantly inhibit the chondrogenic differentiation capacity of MSCs (84) (Table 1).

Table 1. Preclinical strategies targeting synovial macrophage polarization in OA and associated outcomes.

4 Targeting macrophages as a therapeutic strategy for osteoarthritis

Synovial macrophage depletion has elucidated their pivotal role in OA pathogenesis. Clodronate-loaded liposomes were first shown to effectively ablate synovial macrophages in mice, reducing TGF-β–mediated osteophyte formation (39). This effect was consistently observed across diverse OA models (DMM, CIAOA), reinforcing macrophage-driven osteophyte development (91–93). Subsequent studies also reported decreased VDIPEN levels and MMP-3/MMP-9 expression following depletion, suggesting direct involvement in cartilage matrix degradation (94). However, the lack of macrophage subtype specificity in such approaches limits their translational potential. To improve therapeutic precision, manipulation of mTOR signaling was employed to skew macrophage polarization, demonstrating M1-driven OA exacerbation versus M2-mediated protection (26). Similarly, clodronate treatment in an ex vivo OA model led to a reduced M1/M2 ratio and attenuated IL-1β, MMP-3 expression, and cartilage degradation (95, 96).

Further studies have explored selective macrophage depletion strategies. Targeting CD14 + macrophages in OA synovium was shown to reduce IL-1 and TNF-α levels (68), whereas CD14− macrophages exhibited higher TNF-α and IL-1β mRNA expression (97). In vitro co-culture experiments revealed that M1 macrophages upregulated MMPs, ADAMTS-5, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, contributing to cartilage breakdown (70). Conditioned media from M1-polarized macrophages elevated IL-1β, IL-6, MMP-13, and ADAMTS-5 while suppressing aggrecan and collagen II synthesis (98). Notably, M2 macrophages failed to counteract M1-mediated cartilage destruction, suggesting that simply promoting M2 polarization may not suffice to reverse OA progression. In contrast, type II collagen derived from squid was found to promote M2 macrophage polarization, enhance TGF-β and IGF expression, inhibit chondrocyte apoptosis, and facilitate cartilage repair (76). Additionally, magnolol was shown to reduce the synovial M1/M2 ratio and alleviate inflammation in OA mice by inhibiting the p38/ERK, p38/MAPK, and p65/NF-κB signaling pathways (86). Supporting this approach, SIRT1 activators administered either intraperitoneally or intra-articularly effectively reduced synovial inflammation, lowered the M1/M2 ratio, and delayed OA progression in murine models (85).

Collectively, these findings underscore the protective role of M2 macrophages and suggest that modulating macrophage polarization may represent a viable therapeutic strategy for OA (17, 87, 99). Despite encouraging preclinical results, current macrophage-targeted therapies face several limitations that hinder clinical translation. First, non-specific depletion or systemic modulation of macrophages may lead to unintended off-target effects, including disruption of physiological macrophage functions essential for tissue repair and host defense. Second, strategies that broadly promote M2 polarization or inhibit M1 phenotypes risk inducing generalized immunosuppression, potentially compromising innate immune responses and increasing susceptibility to infections. Third, variability in patient-specific factors such as baseline immune profiles, metabolic status, and genetic polymorphisms may result in heterogeneous therapeutic responses, posing challenges for personalized treatment optimization. Lastly, the lack of reliable biomarkers to monitor in vivo macrophage polarization hinders real-time assessment of therapeutic efficacy (87–90).

5 Conclusion

Synovial macrophages play a central role in OA pathogenesis, where their polarization state critically influences inflammatory cascades and tissue homeostasis. Pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages exacerbate synovitis, oxidative stress, and extracellular matrix degradation, whereas M2 macrophages promote resolution of inflammation and tissue repair. Emerging therapeutic approaches, including selective macrophage depletion, mTOR pathway modulation, and SIRT1 activation, have shown efficacy in shifting the M1/M2 equilibrium toward a reparative phenotype, thereby mitigating OA progression. Despite these advances, key challenges persist, particularly in achieving macrophage subtype-specific targeting and bridging the gap between preclinical models and clinical applications. To overcome these challenges, future strategies should emphasize cell-specific delivery systems, such as nanocarrier-mediated or ligand-directed targeting, to selectively reprogram synovial macrophage subtypes within the joint microenvironment. Moreover, combinatory approaches that integrate macrophage modulation with anti-inflammatory agents, regenerative medicine or mechanical joint unloading may yield synergistic benefits. By strategically manipulating macrophage polarization, researchers may unlock innovative treatments capable of not only slowing OA progression but also restoring joint integrity and function.

Author contributions

KuZ: Writing – original draft. ZW: Writing – original draft. JH: Writing – original draft. LL: Writing – original draft. WW: Writing – original draft. AY: Writing – original draft. HX: Writing – original draft. LH: Writing – original draft. YH: Writing – original draft. KeZ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MJ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. RW: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Medical research project of Shenzhen Longhua Medical Association (2024LHMA26) the Scientific Research Projects of Medical and Health Institutions of Longhua District, Shenzhen (2025011).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Peters H, Rockel JS, Little CB, and Kapoor M. Synovial fluid as a complex molecular pool contributing to knee osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. (2025) 21:447–64. doi: 10.1038/s41584-025-01271-4

2. Alad M, Yousef F, Epure LM, Lui A, Grant MP, Merle G, et al. Unraveling osteoarthritis: mechanistic insights and emerging therapies targeting pain and inflammation. Biomolecules. (2025) 15:874. doi: 10.3390/biom15060874

3. Jiang M, Wang Z, He X, Hu Y, Xie M, Jike Y, et al. A risk-scoring model based on evaluation of ferroptosis-related genes in osteosarcoma. J Oncol. (2022) 2022:4221756. doi: 10.1155/2022/4221756

4. Xue HY, Shen XL, Wang ZH, Bi HC, Xu HG, Wu J, et al. Research progress on mesenchymal stem cell−derived exosomes in the treatment of osteoporosis induced by knee osteoarthritis (Review). Int J Mol Med. (2025) 56:160. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2025.5601

5. Qian Z, Xu J, Zhang L, Miao Z, Lv Z, Ji H, et al. Muscone ameliorates osteoarthritis progression by inhibiting M1 macrophages polarization via Nrf2/NF-κB axis and protecting chondrocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. (2025) 503:117494. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2025.117494

6. Sanchez-Lopez E, Coras R, Torres A, Lane NE, and Guma M. Synovial inflammation in osteoarthritis progression. Nat Rev Rheumatol. (2022) 18:258–75. doi: 10.1038/s41584-022-00749-9

7. Bortoluzzi A, Furini F, and Scirè CA. Osteoarthritis and its management - Epidemiology, nutritional aspects and environmental factors. Autoimmun Rev. (2018) 17:1097–104. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.06.002

8. Furman BD, Kimmerling KA, Zura RD, Reilly RM, Zlowodzki MP, Huebner JL, et al. Articular ankle fracture results in increased synovitis, synovial macrophage infiltration, and synovial fluid concentrations of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2015) 67:1234–9. doi: 10.1002/art.39064

9. Ayral X, Pickering EH, Woodworth TG, Mackillop N, and Dougados M. Synovitis: a potential predictive factor of structural progression of medial tibiofemoral knee osteoarthritis – results of a 1 year longitudinal arthroscopic study in 422 patients. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2005) 13:361–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.01.005

10. Henrotin Y, Lambert C, and Richette P. Importance of synovitis in osteoarthritis: evidence for the use of glycosaminoglycans against synovial inflammation. Semin Arthritis Rheum. (2014) 43:579–87. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.10.005

11. Liu-Bryan R. Synovium and the innate inflammatory network in osteoarthritis progression. Curr Rheumatol Rep. (2013) 15:323. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0323-5

12. Scanzello CR and Goldring SR. The role of synovitis in osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Bone. (2012) 51:249–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.02.012

13. Wu CL, Harasymowicz NS, Klimak MA, Collins KH, and Guilak F. The role of macrophages in osteoarthritis and cartilage repair. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2020) 28:544–54. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.12.007

14. Bondeson J, Blom AB, Wainwright S, Hughes C, Caterson B, and van den Berg WB. The role of synovial macrophages and macrophage-produced mediators in driving inflammatory and destructive responses in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. (2010) 62:647–57. doi: 10.1002/art.27290

15. de Lange-Brokaar BJ, Ioan-Facsinay A, van Osch GJ, Zuurmond AM, Schoones J, Toes RE, et al. Synovial inflammation, immune cells and their cytokines in osteoarthritis: a review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2012) 20:1484–99. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.08.027

16. Kulakova K, Lawal TR, Mccarthy E, and Floudas A. The contribution of macrophage plasticity to inflammatory arthritis and their potential as therapeutic targets. Cells. (2024) 13:1586. doi: 10.3390/cells13181586

17. Zou X, Xu H, and Qian W. Macrophage polarization in the osteoarthritis pathogenesis and treatment. Orthop Surg. (2025) 17:22–35. doi: 10.1111/os.14302

18. Yuan Z, Jiang D, Yang M, Tao J, Hu X, Yang X, et al. Emerging roles of macrophage polarization in osteoarthritis: mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Orthop Surg. (2024) 16:532–50. doi: 10.1111/os.13993

19. Li W, Liu Y, Wei M, Yang Z, Li Z, Guo Z, et al. Functionalized biomimetic nanoparticles targeting the IL-10/IL-10Rα/glycolytic axis in synovial macrophages alleviate cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritis. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2025) 12:e2504768. doi: 10.1002/advs.202504768

20. Laouteouet D, Bortolotti O, Marineche L, Hannemann N, Chambon M, Glasson Y, et al. Monocyte-Derived macrophages-Synovial fibroblasts crosstalk unravels oncostatin signaling network as a driver of synovitis in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2025). doi: 10.1002/art.43299

21. Athanasou NA and Quinn J. Immunocytochemical analysis of human synovial lining cells: phenotypic relation to other marrow derived cells. Ann Rheum Dis. (1991) 50:311–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.5.311

22. Haywood L, McWilliams DF, Pearson CI, Gill SE, Ganesan A, Wilson D, et al. Inflammation and angiogenesis in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. (2003) 48:2173–7. doi: 10.1002/art.11094

23. Benito MJ, Veale DJ, FitzGerald O, van den Berg WB, and Bresnihan B. Synovial tissue inflammation in early and late osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. (2005) 64:1263–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.025270

24. Bondeson J, Wainwright SD, Lauder S, Amos N, and Hughes CE. The role of synovial macrophages and macrophage-produced cytokines in driving aggrecanases, matrix metalloproteinases, and other destructive and inflammatory responses in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. (2006) 8:R187. doi: 10.1186/ar2099

25. Kraus VB, McDaniel G, Huebner JL, Stabler TV, Pieper CF, Shipes SW, et al. Direct in vivo evidence of activated macrophages in human osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2016) 24:1613–21. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.04.010

26. Zhang H, Lin C, Zeng C, Wang Z, Wang H, Lu J, et al. et al: Synovial macrophage M1 polarisation exacerbates experimental osteoarthritis partially through R-spondin-2. Ann Rheum Dis. (2018) 77:1524–34. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213450

27. Manferdini C, Paolella F, Gabusi E, Silvestri Y, Gambari L, Cattini L, et al. From osteoarthritic synovium to synovial-derived cells characterization: synovial macrophages are key effector cells. Arthritis Res Ther. (2016) 18:83. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0983-4

28. van den Bosch MH, Blom AB, Schelbergen RF, Koenders MI, van de Loo FA, van den Berg WB, et al. Alarmin S100A9 induces proinflammatory and catabolic effects predominantly in the M1 macrophages of human osteoarthritic synovium. J Rheumatol. (2016) 43:1874–84. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.160270

29. Yang J, Li S, Li Z, Yao L, Liu M, Tong KL, et al. Targeting YAP1-regulated glycolysis in fibroblast-Like synoviocytes impairs macrophage infiltration to ameliorate diabetic osteoarthritis progression. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2024) 11:e2304617. doi: 10.1002/advs.202304617

30. Cerreto GM, Pozzi G, Cortellazzi S, Pasini LM, Di Martino O, Mirandola P, et al. Folate metabolism in myelofibrosis: a missing key? Ann Hematol. (2025) 104:35–46. doi: 10.1007/s00277-024-06176-y

31. Nalio Ramos R, Missolo-Koussou Y, Gerber-Ferder Y, Bromley CP, Bugatti M, Núñez NG, et al. Tissue-resident FOLR2(+) macrophages associate with CD8(+) T cell infiltration in human breast cancer. Cell. (2022) 185:1189–1207.e1125. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.02.021

32. Piscaer TM, Müller C, Mindt TL, Lubberts E, Verhaar JA, Krenning EP, et al. Imaging of activated macrophages in experimental osteoarthritis using folate-targeted animal single-photon-emission computed tomography/computed tomography. Arthritis Rheum. (2011) 63:1898–907. doi: 10.1002/art.30363

33. Daghestani HN, Pieper CF, and Kraus VB. Soluble macrophage biomarkers indicate inflammatory phenotypes in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2015) 67:956–65. doi: 10.1002/art.39006

34. Huzum RM, Huzum B, Hînganu MV, Lozneanu L, Lupu FC, and Hînganu D. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of the degenerative processes of the hip joint capsule and acetabular labrum. Diagnostics (Basel). (2025) 15:1932. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics15151932

35. Abdel-Aziz MA, Ahmed HM, El-Nekeety AA, and Abdel-Wahhab MA. Osteoarthritis complications and the recent therapeutic approaches. Inflammopharmacol. (2021) 29:1653–67. doi: 10.1007/s10787-021-00888-7

36. Wang D, Chai X-Q, Hu S-S, and Pan F. Cartilage: Joint synovial macrophages as a potential target for intra-articular treatment of osteoarthritis-related pain. Osteoarthr Cartil. (2022) 30:406–15. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2021.11.014

37. Shapouri-Moghaddam A, Mohammadian S, Vazini H, Taghadosi M, Esmaeili SA, Mardani F, et al. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol. (2018) 233:6425–40. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26429

38. Wang D, Chai XQ, Hu SS, and Pan F. Joint synovial macrophages as a potential target for intra-articular treatment of osteoarthritis-related pain. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2022) 30:406–15. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2021.11.014

39. Xu M and Ji Y. Immunoregulation of synovial macrophages for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Open Life Sci. (2023) 18:20220567. doi: 10.1515/biol-2022-0567

40. Orecchioni M, Ghosheh Y, Pramod AB, and Ley K. Macrophage Polarization: Different Gene Signatures in M1(LPS+) vs. Classically and M2(LPS-) vs. Alternatively Activated Macrophages. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:1084. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01084

41. Topoluk N, Steckbeck K, Siatkowski S, Burnikel B, Tokish J, and Mercuri J. Amniotic mesenchymal stem cells mitigate osteoarthritis progression in a synovial macrophage-mediated in vitro explant coculture model. J Tissue Eng Regener Med. (2018) 12:1097–110. doi: 10.1002/term.2610

42. Liu B, Zhang M, Zhao J, Zheng M, and Yang H. Imbalance of M1/M2 macrophages is linked to severity level of knee osteoarthritis. Exp Ther Med. (2018) 16:5009–14. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6852

43. Tay TL, BéChade C, D’Andrea I, St-Pierre MK, Henry MS, Roumier A, et al. Microglia gone rogue: impacts on psychiatric disorders across the lifespan. Front Mol Neurosci. (2017) 10:421. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00421

44. Dang Y, Liu Y, Zhang B, and Zhang X. Aging microenvironment in osteoarthritis focusing on early-stage alterations and targeted therapies. Bone Res. (2025) 13:84. doi: 10.1038/s41413-025-00465-6

45. Anderson RJ. Synovial histopathology across a Spectrum of Hip Disorders: From Pre-Arthritic Femoroacetabular Impingement to Advanced Osteoarthritis. The University of Western Ontario (Canada (2023).

46. Zheng Y, Wei K, Jiang P, Zhao J, Shan Y, Shi Y, et al. Macrophage polarization in rheumatoid arthritis: signaling pathways, metabolic reprogramming, and crosstalk with synovial fibroblasts. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1394108. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1394108

47. Zahan O-M, Serban O, Gherman C, and Fodor D. The evaluation of oxidative stress in osteoarthritis. Med Pharm Rep. (2020) 93:12. doi: 10.15386/mpr-1422

48. Qiu C, Zhang Z, Wang H, Liu N, Li R, Wei Z, et al. Identification and verification of XDH genes in ROS induced oxidative stress response of osteoarthritis based on bioinformatics analysis. Scientific Rep. (2025) 15:29759. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-11667-7

49. Minguzzi M, Cetrullo S, D’Adamo S, Silvestri Y, Flamigni F, and Borzì RM. Emerging players at the intersection of chondrocyte loss of maturational arrest, oxidative stress, senescence and low-grade inflammation in osteoarthritis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2018) 2018:3075293. doi: 10.1155/2018/3075293

50. Patergnani S, Bouhamida E, Leo S, Pinton P, and Rimessi A. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and “mito-inflammation”: actors in the diseases. Biomedicines. (2021) 9:216. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9020216

51. Sun H, Sun Z, Xu X, Lv Z, Li J, Wu R, et al. Blocking TRPV4 ameliorates osteoarthritis by inhibiting M1 macrophage polarization via the ROS/NLRP3 signaling pathway. Antioxidants (Basel). (2022) 11:2315. doi: 10.3390/antiox11122315

52. Deng Z, Yang W, Zhao B, Yang Z, Li D, and Yang F. Advances in research on M1/M2 macrophage polarization in the pathogenesis and treatment of osteoarthritis. Heliyon. (2025) 11. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e42881

53. Yu M, Wang S, and Lin D. Mechanism and application of biomaterials targeting reactive oxygen species and macrophages in inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 26:245. doi: 10.3390/ijms26010245

54. Iantomasi T, Aurilia C, Donati S, Falsetti I, Palmini G, Carossino R, et al. Oxidative stress, microRNAs, and long non-coding RNAs in osteoarthritis pathogenesis: cross-talk and molecular mechanisms involved. Int J Mol Sci. (2025) 26:6428. doi: 10.3390/ijms26136428

55. Zheng W, Tao Z, Cai L, Chen C, Zhang C, Wang Q, et al. Chrysin attenuates IL-1β-induced expression of inflammatory mediators by suppressing NF-κB in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes. Inflammation. (2017) 40:1143–54. doi: 10.1007/s10753-017-0558-9

56. Wang W, Chu Y, Zhang P, Liang Z, Fan Z, Guo X, et al. Targeting macrophage polarization as a promising therapeutic strategy for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Int Immunopharmacol. (2023) 116:109790. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.109790

57. Rahaman SN, Lishadevi M, and Anandasadagopan SK. Unraveling the molecular mechanisms of osteoarthritis: the potential of polyphenols as therapeutic agents. Phytother Res. (2025) 39:2038–71. doi: 10.1002/ptr.8455

58. Chen M, Zhang Y, Zhou P, Liu X, Zhao H, Zhou X, et al. Substrate stiffness modulates bone marrow-derived macrophage polarization through NF-κB signaling pathway. Bioact Mater. (2020) 5:880–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.05.004

59. Zhou F, Mei J, Han X, Li H, Yang S, Wang M, et al. Kinsenoside attenuates osteoarthritis by repolarizing macrophages through inactivating NF-κB/MAPK signaling and protecting chondrocytes. Acta Pharm Sin B. (2019) 9:973–85. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.01.015

60. Schirrmacher V. Mitochondria at work: new insights into regulation and dysregulation of cellular energy supply and metabolism. Biomedicines. (2020) 8:526. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8110526

61. Venditti P and Di Meo S. The role of reactive oxygen species in the life cycle of the mitochondrion. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:2173. doi: 10.3390/ijms21062173

62. Tian S, Zhang Y, Liu C, Zhang H, Lu Q, Zhao Y, et al. Double-edged mitophagy: balancing inflammation and resolution in lung disease. Clin Sci. (2025) 139:CS20256705. doi: 10.1042/CS20256705

63. Ke S, Li C, Liu X, Wang Y, Yang P, and Ye S. MoS2 quantum dots alter macrophage plasticity and induce mitophagy to attenuate endothelial barrier dysfunctions. ACS Appl Nano Mater. (2023) 6:6247–58. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.3c00595

64. Ma J, Wang X, Sun D, Chen J, Zhou L, Zou K, et al. DPSCs modulate synovial macrophage polarization and efferocytosis via PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2025) 16:356. doi: 10.1186/s13287-025-04565-2

65. Li M, Yin H, Yan Z, Li H, Wu J, Wang Y, et al. The immune microenvironment in cartilage injury and repair. Acta Biomater. (2022) 140:23–42. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.12.006

66. Thomson A and Hilkens CMU. Synovial macrophages in osteoarthritis: the key to understanding pathogenesis? Front Immunol. (2021) 12:678757. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.678757

67. Fernandes TL, Gomoll AH, Lattermann C, Hernandez AJ, Bueno DF, and Amano MT. Macrophage: A potential target on cartilage regeneration. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:111. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00111

68. Wang L and He C. Nrf2-mediated anti-inflammatory polarization of macrophages as therapeutic targets for osteoarthritis. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:967193. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.967193

69. Chen X, Liu Y, Wen Y, Yu Q, Liu J, Zhao Y, et al. A photothermal-triggered nitric oxide nanogenerator combined with siRNA for precise therapy of osteoarthritis by suppressing macrophage inflammation. Nanoscale. (2019) 11:6693–709. doi: 10.1039/C8NR10013F

70. Samavedi S, Diaz-Rodriguez P, Erndt-Marino JD, and Hahn MS. A three-dimensional chondrocyte-macrophage coculture system to probe inflammation in experimental osteoarthritis. Tissue Eng Part A. (2017) 23:101–14. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2016.0007

71. Xie J, Huang Z, Yu X, Zhou L, and Pei F. Clinical implications of macrophage dysfunction in the development of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. (2019) 46:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2019.03.004

72. Núñez-Carro C, Blanco-Blanco M, Montoya T, Villagrán-Andrade KM, Hermida-Gómez T, Blanco FJ, et al. Histone extraction from human articular cartilage for the study of epigenetic regulation in osteoarthritis. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:3355. doi: 10.3390/ijms23063355

73. López-Armada MJ, Caramés B, Lires-Deán M, Cillero-Pastor B, Ruiz-Romero C, Galdo F, et al. Cytokines, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta, differentially regulate apoptosis in osteoarthritis cultured human chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2006) 14:660–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.01.005

74. Ji B, Guo W, Ma H, Xu B, Mu W, Zhang Z, et al. Isoliquiritigenin suppresses IL-1β induced apoptosis and inflammation in chondrocyte-like ATDC5 cells by inhibiting NF-κB and exerts chondroprotective effects on a mouse model of anterior cruciate ligament transection. Int J Mol Med. (2017) 40:1709–18. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3177

75. Wang B, Bai C, and Zhang Y. Paeoniae radix alba and network pharmacology approach for osteoarthritis: A review. Separations. (2024) 11:184. doi: 10.3390/separations11060184

76. Dai M, Sui B, Xue Y, Liu X, and Sun J. Cartilage repair in degenerative osteoarthritis mediated by squid type II collagen via immunomodulating activation of M2 macrophages, inhibiting apoptosis and hypertrophy of chondrocytes. Biomaterials. (2018) 180:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.07.011

77. Das P, Jana S, and Kumar Nandi S. Biomaterial-based therapeutic approaches to osteoarthritis and cartilage repair through macrophage polarization. Chem Rec. (2022) 22:e202200077. doi: 10.1002/tcr.202200077

78. Couto CMS. Immunomodulatory Nanoenabled 3D Scaffolds for Chondral Repair. Porto, Portugal: Universidade do Porto (Portugal (2021).

79. Madsen DH, Leonard D, Masedunskas A, Moyer A, Jürgensen HJ, Peters DE, et al. M2-like macrophages are responsible for collagen degradation through a mannose receptor-mediated pathway. J Cell Biol. (2013) 202:951–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201301081

80. Zhang H, Cai D, and Bai X. Macrophages regulate the progression of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2020) 28:555–61. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2020.01.007

81. Fonseca LN, Bolívar-Moná S, Agudelo T, Beltrán LD, Camargo D, Correa N, et al. Cell surface markers for mesenchymal stem cells related to the skeletal system: A scoping review. Heliyon. (2023) 9. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13464

82. Feng H, Jiang B, Xing W, Sun J, Greenblatt MB, and Zou W. Skeletal stem cells: origins, definitions, and functions in bone development and disease. Life Med. (2022) 1:276–93. doi: 10.1093/lifemedi/lnac048

83. Sun Y, Zuo Z, and Kuang Y. An emerging target in the battle against osteoarthritis: macrophage polarization. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:8513. doi: 10.3390/ijms21228513

84. Fahy N, de Vries-van Melle ML, Lehmann J, Wei W, Grotenhuis N, Farrell E, et al. Human osteoarthritic synovium impacts chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells via macrophage polarisation state. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2014) 22:1167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.05.021

85. Miyaji N, Nishida K, Tanaka T, Araki D, Kanzaki N, Hoshino Y, et al. Inhibition of knee osteoarthritis progression in mice by administering SRT2014, an activator of silent information regulator 2 ortholog 1. Cartilage. (2021) 13:1356s–66s. doi: 10.1177/1947603519900795

86. Lu J, Zhang H, Pan J, Hu Z, Liu L, Liu Y, et al. Fargesin ameliorates osteoarthritis via macrophage reprogramming by downregulating MAPK and NF-κB pathways. Arthritis Res Ther. (2021) 23:142. doi: 10.1186/s13075-021-02512-z

87. Knights AJ, Redding SJ, and Maerz T. Inflammation in osteoarthritis: the latest progress and ongoing challenges. Curr Opin Rheumatol. (2023) 35:128–34. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000923

88. Zhao K, Ruan J, Nie L, Ye X, and Li J. Effects of synovial macrophages in osteoarthritis. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1164137. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1164137

89. Chang JW and Tang CH. The role of macrophage polarization in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: Pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Int Immunopharmacol. (2024) 142:113056. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113056

90. Yin X, Wang Q, Tang Y, Wang T, Zhang Y, and Yu T. Research progress on macrophage polarization during osteoarthritis disease progression: a review. J Orthop Surg Res. (2024) 19:584. doi: 10.1186/s13018-024-05052-9

91. Blom AB, van Lent PL, Holthuysen AE, van der Kraan PM, Roth J, van Rooijen N, et al. Synovial lining macrophages mediate osteophyte formation during experimental osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2004) 12:627–35. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.03.003

92. Wu CL, McNeill J, Goon K, Little D, Kimmerling K, Huebner J, et al. Conditional macrophage depletion increases inflammation and does not inhibit the development of osteoarthritis in obese macrophage fas-induced apoptosis-transgenic mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2017) 69:1772–83. doi: 10.1002/art.40161

93. Li J, Hsu HC, Yang P, Wu Q, Li H, Edgington LE, et al. Treatment of arthritis by macrophage depletion and immunomodulation: testing an apoptosis-mediated therapy in a humanized death receptor mouse model. Arthritis Rheum. (2012) 64:1098–109. doi: 10.1002/art.33423

94. Blom AB, Van Lent PL, Libregts S, Holthuysen AE, van der Kraan PM, Van Rooijen N, et al. Rheumatism: Crucial role of macrophages in matrix metalloproteinase–mediated cartilage destruction during experimental osteoarthritis: involvement of matrix metalloproteinase 3. Arthr Rheum. (2007) 56:147–57. doi: 10.1002/art.22337

95. Everett J, Menarim BC, Werre SR, Barrett SH, Byron CR, Pleasant RS, et al. Bone marrow mononuclear cell therapy for equine joint disease. In: 66th Annual Convention, Am Assoc Equine Pract Virginia, Blacksburg, USA: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (2020).

96. Moretti A, Paoletta M, Liguori S, Ilardi W, Snichelotto F, Toro G, et al. The rationale for the intra-articular administration of clodronate in osteoarthritis. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:2693. doi: 10.3390/ijms22052693

97. Takano S, Uchida K, Inoue G, Miyagi M, Aikawa J, Iwase D, et al. Nerve growth factor regulation and production by macrophages in osteoarthritic synovium. Clin Exp Immunol. (2017) 190:235–43. doi: 10.1111/cei.13007

98. Utomo L, Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM, Verhaar JA, and van Osch GJ. Cartilage inflammation and degeneration is enhanced by pro-inflammatory (M1) macrophages in vitro, but not inhibited directly by anti-inflammatory (M2) macrophages. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2016) 24:2162–70. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.07.018

Keywords: osteoarthritis, synovitis, macrophages, cartilage degeneration, macrophage polarization, immunomodulation

Citation: Zhang K, Wang Z, He J, Lu L, Wang W, Yang A, Xie H, Huang L, Huang Y, Zhang K, Jiang M and Wei R (2025) Mechanisms of synovial macrophage polarization in osteoarthritis pathogenesis and their therapeutic implications. Front. Immunol. 16:1637731. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1637731

Received: 29 May 2025; Accepted: 07 November 2025; Revised: 05 November 2025;

Published: 25 November 2025.

Edited by:

Nikolaos I. Vlachogiannis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceReviewed by:

Ibsen Bellini Coimbra, State University of Campinas, BrazilXidong Li, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Wang, He, Lu, Wang, Yang, Xie, Huang, Huang, Zhang, Jiang and Wei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ruqiong Wei, cnVxaW9uZ3dlaUBzci5neG11LmVkdS5jbg==; Mingyang Jiang, MjAyMTIwNTc2QHNyLmd4bXUuZWR1LmNu; Ke Zhang, a3oxODIwMjI4MjgwMUAxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Kun Zhang

Kun Zhang Zheng Wang

Zheng Wang Jiaqi He3

Jiaqi He3 Yuying Huang

Yuying Huang Ke Zhang

Ke Zhang Mingyang Jiang

Mingyang Jiang Ruqiong Wei

Ruqiong Wei