Abstract

Background:

Anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) disease represents the most severe form of crescentic glomerulonephritis. Previous studies demonstrated that Bowman’s capsule rupture contributed to the progression of crescentic glomerulonephritis. However, its role in anti-GBM disease remains unclear. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence and severity of Bowman’s capsule rupture in patients with anti-GBM disease and its clinical associations.

Methods:

A total of 72 patients diagnosed with biopsy-proven anti-GBM disease with complete clinical and pathologic data were retrospectively enrolled.

Results:

Extensive Bowman’s capsule rupture occurred in 70 patients (97.2%) with a median percentage of 52.8% of all glomeruli on each kidney biopsy. The percentage of Bowman’s capsule rupture showed a strong association with kidney injuries (incidence of oligoanuria, eGFR, and serum creatinine on diagnosis; P < 0.001) and the levels of anti-GBM antibody (P = 0.013). Histologically, Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage was positively correlated with crescent percentage (P = 0.001) and increased proportion of cellular–fibrous crescents specifically (P = 0.047). The Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed significantly divergent outcomes in kidney survival (P = 0.006) and kidney recovery (P = 0.016) when the patients were divided into different groups according to the percentage of Bowman’s capsule rupture. The incorporation of Bowman’s capsule rupture into two proposed prediction models of risk stratification tool and renal risk score could improve their prognostic performance.

Conclusions:

Bowman’s capsule rupture serves as both a distinct histopathological feature and a critical determinant of kidney injury in anti-GBM disease. More importantly, as a simple, standalone parameter, it demonstrates a robust predictive value for kidney outcomes in patients with anti-GBM disease.

Introduction

Anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) disease is a rare autoimmune kidney disease characterized by the presence of pathogenic autoantibodies against the GBM components, causing rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis with diffuse crescent formation on kidney biopsies (1). Although the utilization of aggressive immunosuppressive therapies leads to remarkable improvements in patient survival, kidney outcomes remain suboptimal. A substantial proportion of patients (60%–80%) progress to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) within the first year of follow-up, subsequently requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT) (2). Therefore, identifying clinical or pathological indicators to predict kidney prognosis would be useful for clinicians to make individualized treatment regimens (3–5).

Bowman’s capsule is the outer epithelial wall of the glomerular corpuscle and serves as a physical barrier to protect the glomerulus, which consists of a parietal layer composed of a single layer of flat partial epithelial cells (PECs). The proliferating PEC, the core component of Bowman’s capsule, is a pathological hallmark of crescentic glomerulonephritis (6–9). In recent years, accumulating evidence underscores the critical contribution of Bowman’s capsule rupture in the development of crescentic glomerulonephritis (10–12). We previously revealed that the prevalence of glomerular infiltrating CD8+ T cells was correlated with the percentage of Bowman’s capsule rupture in patients with anti-GBM disease (11). In addition, Chen et al. further elucidated that the peri-glomerular pathogenic CD8+ T cells attacked Bowman’s capsule, inducing its rupture and thereby exacerbating experimental anti-GBM nephritis (12). These findings together emphasize the essential involvement of Bowman’s capsule rupture in the pathogenesis of anti-GBM disease. However, the clinical association between the extent of Bowman’s capsule rupture on kidney biopsies and kidney prognosis in anti-GBM disease has not been previously studied. Therefore, in the present study, we aim to investigate the landscape of Bowman’s capsule rupture and its clinical significance in a large cohort of patients with biopsy-proven anti-GBM disease.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 72 patients diagnosed with biopsy-proven anti-GBM disease in Peking University First Hospital between 2005 and 2022 were enrolled. The diagnosis of anti-GBM diseases was based on serum detection of anti-GBM antibodies and kidney biopsy showing linear IgG fluorescence along the GBM. Anti-GBM antibodies were detected by commercial ELISA kits (Euroimmun, Luebeck, Germany). Patients with following criteria were excluded: (a) combined with other forms of crescentic glomerulonephritis, such as antineutrophil cytoplasm antibodies (ANCA)-associated vasculitis and lupus nephritis, (b) inadequate number of glomeruli on biopsy (<10), (c) other causes that resulted in linear IgG deposition, such as diabetes and fibrillary glomerulonephritis, and (d) loss of biopsy slides or incomplete clinical–pathological data. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical parameters and kidney histopathology

ESKD is defined as the maintenance of kidney replacement therapy (KRT) for at least 12 weeks and up to the last follow-up. Kidney recovery is defined as independence from RRT for at least 12 weeks during follow-up. At least eight consecutive levels were performed to assess different pathological indicators with various stains, including periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson, and dual PAS + Masson. For the evaluation of Bowman’s capsule rupture, kidney tissues primarily stained with periodic acid–Schiff and Masson were independently evaluated by two pathologists using light microscopy. Normal glomeruli are defined as glomeruli that did not exhibit glomerulosclerosis, crescents, or fibrinoid necrosis. Renal risk score (RRS) was calculated as described previously (4). Bowman’s capsule rupture was defined as a discontinuity in the wall of Bowman’s capsule on kidney biopsy sections. When a fibrous crescent occurred within the glomerulus in which collagen fibers may mimic a capsule or form a pseudo-capsule, the glomerulus was only defined as having Bowman’s capsule rupture if a suspected discontinuity in the capsule was accompanied by the presence of peri-glomerular inflammatory cell infiltration (as identified on H&E staining). The Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage was calculated as a fraction of the affected glomeruli divided by the total number of glomeruli on each kidney biopsy.

Statistics

Data are shown as the median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and number (%) for qualitative variables. The regression tree analysis was performed using the R package rpart (version 4.1.19; R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) to determine the cutoff values of Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage for categorizing patients into different groups. The Cochran–Armitage trend test was performed to compare the baseline data among groups. Factors predictive of kidney outcomes were evaluated by using Kaplan–Meier analysis, Cox proportional hazard model with discrimination capability (assessed by Harrell’s C statistic), and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. P-value <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R v4.0.5.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

A total of 72 patients with biopsy-confirmed anti-GBM disease were included in our study (Figure 1). The cohort demonstrated a balanced gender distribution (51.4% female and 48.6% male) and a median age of 43.5 years (IQR: 33.0-55.8) at diagnosis. The median serum creatinine on diagnosis was 613.8 μmol/L, and the median level of anti-GBM antibody was 156.00 RU/mL. A total of 49 (68.1%) patients received RRT at presentation. All patients (100%) received glucocorticoids, and 58 (80.6%) patients received cyclophosphamide.

Figure 1

Workflow and clinical outcomes of Bowman’s capsule rupture in patients with anti-GBM diseases. A total of 72 patients diagnosed with anti-GBM diseases who underwent kidney biopsies were enrolled. The severity of Bowman’s capsule rupture was evaluated using light microscopy. The proportion of individuals with varying Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage on the biopsies is shown in the pie chart. Correlation and prognostic analyses were performed between Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage and parameters.

During follow-up, 14/49 (28.6%) patients among those requiring RRT at presentation achieved kidney recovery, 40/72 (55.6%) patients progressed to ESKD, and one death (1.4%) occurred among all patients (Table 1).

Correlation between Bowman’s capsule rupture and the clinical features of anti-GBM patients

The histopathological evaluation demonstrated that the presence of Bowman’s capsule rupture was observed in 97.2% (70/72) of all patients, with a median percentage of 52.8% (42.3%, 71.4%) among all glomeruli. To evaluate the association of the percentage of Bowman’s capsule rupture among all glomeruli in patients with anti-GBM disease with kidney prognosis, the cutoff values for Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage were established using a regression tree analysis according to the status of kidney survival (Supplementary Figure S1). Three applicable cutoff values for Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage at 25%, 50%, and 75% were identified and thus categorized the patients into four groups (group 1: 0%–25%, n = 9; group 2: 25%–50%, n = 23; group 3: 50%–75%, n = 26; and group 4: 75%–100%, n = 14). Patients in higher Bowman’s capsule rupture categories had increasingly higher rates of oligoanuria incidence (P < 0.001), accompanied by marked declines in kidney function including serum creatinine (P < 0.001) on diagnosis and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR, P < 0.001; Table 1). Patients in higher Bowman’s capsule rupture categories, particularly groups 3 and 4, had increased levels of anti-GBM antibody (P = 0.013). The median proportion of normal glomeruli decreased significantly from 50.0% in group 1 to 0.0% in group 4 (P = 0.001), along with an increased median percentage of cellular–fibrous crescents from 17.1% to 48.8% (P = 0.047). More importantly, the rates of RRT initiation increased from 22.2% in group 1 to 92.9% in group 4 (P = 0.001), while the progression to ESKD increased from 22.2% to 85.7% (P = 0.012). Notably, the rates of kidney recovery were inversely correlated with Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage, declining from 50.0% in group 1 to 7.7% in group 4.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Total (n = 72) | Group 1 (0%–25%) (n = 9) | Group 2 (25%–50%) (n = 23) | Group 3 (50%–75%) (n = 26) | Group 4 (75%–100%) (n = 14) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 43.5 (33.0, 55.8) | 43.0 (32.0, 48.0) | 46.0 (34.5, 55.5) | 43.5 (32.5, 57.3) | 40.0 (34.5, 51.8) | 0.777 |

| Female (%) | 37 (51.4) | 3 (33.3) | 10 (43.5) | 12 (46.2) | 12 (85.7) | 0.034 |

| Prodromal infection (%) | 30 (41.7) | 5 (55.6) | 11 (47.8) | 6 (23.1) | 8 (57.1) | 0.105 |

| Hydrocarbon (%) | 8 (14.0) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (16.7) | 3 (15.0) | 1 (8.3) | 0.931 |

| Hemoptysis (%) | 14 (19.4) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (21.7) | 3 (11.5) | 3 (21.4) | 0.521 |

| Oligoanuri | 23 (31.9) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (17.4) | 8 (30.8) | 11 (78.6) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m^2) | 7.2 (4.9, 18.9) | 46.5 (16.4, 64.9) | 11.2 (5.2, 20.8) | 6.3 (5.1, 10.6) | 3.6 (2.4, 6.3) | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 613.8 (301.2, 882.5) | 124.0 (110.0, 391.0) | 493.0 (272.3, 785.1) | 677.2 (431.50, 842.2) | 1051.5 (678.0, 1549.0) | <0.001 |

| Anti-GBM Ab (RU/mL) | 156.0 (74.5, 200.0) | 90.5 (59.0, 174.5) | 88.0 (65.5, 178.0) | 157.0 (55.3, 200.0) | 200.0 (200.0, 200.0) | 0.013 |

| Bowman’s capsule rupture (%) | 52.8 (42.3, 71.4) | 10.7 (10.0, 20.0) | 43.8 (34.0, 47.5) | 65.9 (54.8, 69.8) | 86.2 (84.7, 93.7) | <0.001 |

| Normal glomeruli (%) | 8.7 (0.0, 29.6) | 50.0 (27.2, 66.7) | 11.7 (6.3, 36.7) | 7.7 (0.0, 22.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 6.9) | 0.001 |

| Crescents (%) | 85.4 (57.1, 92.9) | 39.0 (32.0, 57.8) | 78.6 (53.0, 90.1) | 85. (68.0, 92.2) | 93.9 (90.3, 100.0) | 0.001 |

| Cellular crescent (%) | 33.4 (16.7, 52.9) | 25.0 (7.7, 50.0) | 34.6 (14.4, 51.5) | 27.8 (17.5, 50.7) | 40.3 (28.3, 79.4) | 0.667 |

| Cellular-fibrous crescent (%) | 35.0 (16.4, 58.7) | 17.1 (0.0, 26.3) | 32.0 (19.9, 48.5) | 46.7 (27.3, 60.7) | 48.83 (10.0, 74.7) | 0.047 |

| Fibrous crescent (%) | 0.0 (0.0, 7.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 5.3) | 0.0 (0.0, 3.9) | 0.0 (0.0, 6.7) | 0.0 (0.0, 8.0) | 0.943 |

| Initial need for RRT (%) | 49 (68.1) | 2 (22.2) | 13 (56.5) | 21 (80.8) | 13 (92.9) | 0.001 |

| Glucocorticoids (%) | 72 (100.0) | 9 (100.0) | 23 (100.0) | 26 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | - |

| Cyclophosphamide (%) | 58 (80.6) | 9 (100.0) | 16 (69.6) | 21 (80.8) | 12 (85.7) | 0.242 |

| Plasma exchange (%) | 65 (90.3) | 8 (88.9) | 20 (87.0) | 23 (88.5) | 14 (100.0) | 0.590 |

| Kidney recovery (%) | 14 (28.6) | 1 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) | 6 (28.6) | 1 (7.7) | 0.158 |

| ESKD (%) | 40 (55.6) | 2 (22.2) | 10 (43.5) | 16 (61.5) | 12 (85.7) | 0.012 |

| Mortality (%) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.1) | 0.248 |

| Follow-up, months | 24.0 (5.5, 36.9) | 36.0 (24.0, 44.3) | 16.0 (5.4, 36.3) | 25.0 (3.5, 37.1) | 21.3 (12.1, 31.2) | 0.570 |

Baseline characteristics and comparison of patients in groups according to Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage.

Number (%) and median values (interquartile range) are shown. Statistically significant differences are reported with a bold P-value.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GBM, glomerular basement membrane; RRT, renal replacement therapy; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease.

As demonstrated in Figure 2 by correlation analysis, Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage exhibited a strong positive correlation with serum creatinine on diagnosis (r = 0.500, P < 0.001), oligoanuria incidence (r = 0.478, P < 0.001), levels of anti-GBM antibody (r = 0.386, P = 0.003), crescents (r = 0.451, P < 0.001), and cellular–fibrous crescents (r = 0.330, P = 0.004). Conversely, a significant inverse correlation was observed between Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage and eGFR (r = -0.510, P < 0.001).

Figure 2

Bowman’s capsule rupture is associated with clinical and pathological characteristics. An association between Bowman’s capsule rupture and parameters in patients with GBM disease is shown by a heatmap reflecting the P-value of Spearman’s analysis. Bowman’s capsule rupture was defined as a continuous variable here. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Anti-GBM Ab, anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody; TA/IF, tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Bowman’s capsule rupture and kidney outcomes of anti-GBM patients

A Kaplan–Meier analysis of kidney survival across the four-tiered Bowman’s capsule rupture severity classification revealed progressively worsening prognosis corresponding to increased Bowman’s capsule rupture severity (P = 0.006; Figure 3). Temporal survival patterns revealed early clinical differentiation: at 12, 24, and 36 months, the cumulative proportion of kidney survival was 87.5%, 87.5%, and 70.0% in group 1; 66.7%, 55.0%, and 55.0% in group 2; 42.3%, 42.3% and 38.1% in group 3; and 14.3%, 14.3%, and 14.3% in group 4. Patients in group 4 had the highest proportion of ESKD during follow-up: 12 of 14 patients progressed into ESKD, and 13 of 14 patients required RRT, with only one patient who had initial kidney recovery.

Figure 3

Kidney survival curves of the cumulative incidence of end-stage kidney disease. The patients were divided into four groups according to the percentage of Bowman’s capsule rupture on biopsies. A comparison of survival curves was performed with log-rank test.

To evaluate the prognostic significance of Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage in predicting kidney recovery, a regression tree analysis was performed to identify optimal cutoff values (Supplementary Figure S2). Stratification by a 50% Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage threshold significantly predicted kidney recovery, with the lower Bowman’s capsule rupture group (≤50%) showing superior recovery rates compared to the higher Bowman’s capsule rupture group (>50%). A survival analysis revealed statistically significant disparities in the chance of kidney recovery for both groups (P = 0.016; Figure 4). The cumulative proportion of kidney recovery at 3, 6, and 12 months was 25.0%, 63.5%, and 63.5% in lower Bowman’s capsule rupture group and 9.7%, 20.5%, and 24.7% in higher Bowman’s capsule rupture group.

Figure 4

Kidney recovery curves of patients receiving initial renal replacement therapy. The patients were divided into two groups according to the percentage of Bowman’s capsule rupture on biopsies. A comparison of survival curves was performed with log-rank test.

Bowman’s capsule rupture improves the prognostic performance of clinical prediction tools

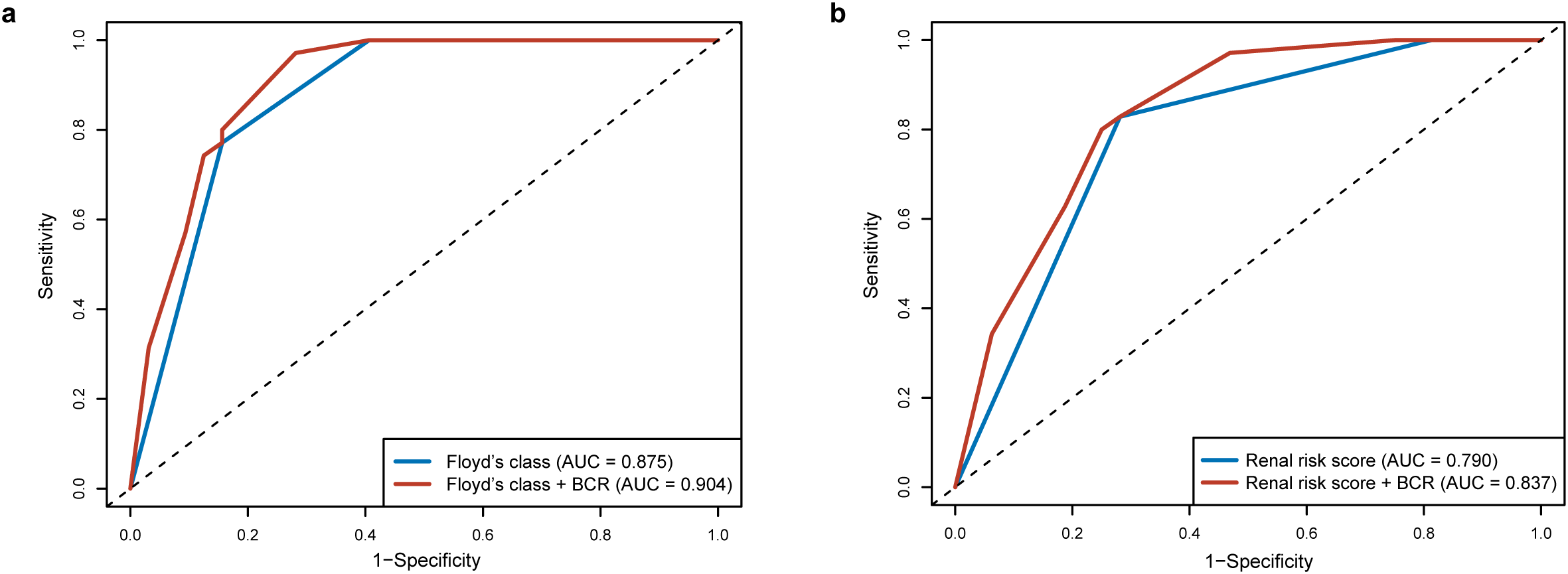

A risk stratification tool was recently established by Floyd et al. by stratifying the patients according to the percentage of normal glomeruli and the initial need for RRT (3). The tool was further validated to predict kidney survival in patients with anti-GBM disease in our previous studies (4). Besides that, a RRS model in ANCA-associated vasculitis was also extended to anti-GBM disease with favorable predictive performance. Among the histological predictors included in the current study, Bowman’s capsule rupture was significantly associated with kidney survival in the univariate analysis (P < 0.001 and C = 0.660, Table 2). The addition of Bowman’s capsule rupture to the risk stratification tool (Floyd’s class, P < 0.001 and C = 0.787) or the RRS tool alone (P < 0.001 and C = 0.720) improved the prognostic performance of the models (C = 0.802 and C = 0.746, respectively). The ROC analysis also demonstrated improved discriminatory performance for the combined models (Floyd’s class + Bowman’s capsule rupture: AUC = 0.904; RRS + Bowman’s capsule rupture: AUC = 0.837) compared to their individual counterparts (Floyd’s class: AUC = 0.875; RRS: AUC = 0.790) at 12-month follow-up although statistical significance was not achieved (P = 0.115 and P = 0.069, respectively; Figures 5a, b).

Table 2

| Predictor | C-index | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | |||

| Active lesions | |||

| Cellular crescents | 0.574 | 1.010 (1.000 to 1.021) | 0.067 |

| Fibrocellular crescents | 0.596 | 1.013 (1.001 to 1.025) | 0.031 |

| Fibrinoid necrosis | 0.533 | 0.998 (0.982 to 1.015) | 0.840 |

| Bowman’s capsule rupture | 0.660 | 1.835 (1.276 to 2.640) | <0.001 |

| Chronic lesions | |||

| Fibrous crescent | 0.540 | 0.978 (0.939 to 1.020) | 0.262 |

| Glomerulosclerosis | 0.581 | 0.647 (0.341 to 1.228) | 0.183 |

| Tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis | 0.491 | 0.967 (0.545 to 1.884) | 0.967 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||

| Floyd’s class only | 0.787 | 3.512 (2.144 to 5.753) | <0.001 |

| Floyd’s class + Bowman’s capsule rupture | 0.802 | ||

| Renal risk score only | 0.720 | 4.997 (2.456 to 10.170) | <0.001 |

| Renal risk score + Bowman’s capsule rupture | 0.746 | ||

Prognostic performance of pathological indicators for kidney survival.

Statistically significant differences are reported with a bold P-value.

C-index, Harrell’s concordance statistic; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; BCR, Bowman’s capsule rupture.

Figure 5

Comparison of prognostic performance for the severity of Bowman’s capsule rupture (BCR) and prediction tools. (a) Comparison of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves between Floyd’s class alone and Floyd’s class with Bowman’s capsule rupture. (b) Comparison of ROC curves between renal risk score alone and renal risk score with Bowman’s capsule rupture. Bowman’s capsule rupture was divided into degrees 1–4 (degree 1: 0%–25%, degree 2: 25%–50%, degree 3: 50%–75%, and degree 4, 75%–100%).

Discussion

In this study, we found that the presence of extensive Bowman’s capsule rupture was closely associated with clinical and histopathological parameters of kidney injuries in patients with anti-GBM disease, indicating a possible role of Bowman’s capsule rupture in its pathogenesis. A key finding of our study was that Bowman’s capsule rupture may serve as a valuable prognostic indicator for kidney outcomes and enhance the performance of existing prognostic tools in patients with anti-GBM disease. Bowman’s capsule rupture is widely regarded as a pathological signature of severe glomerular injury. In the current study, we revealed that a majority of patients (97.2%) with anti-GBM disease showed a feature of Bowman’s capsule rupture in their biopsy samples with an extensive rupture (52.8% of all glomeruli per sample). The markedly higher prevalence and severity of Bowman’s capsule rupture in anti-GBM disease, compared to other glomerulonephritis reported previously including ANCA-associated vasculitis (13), lupus nephritis (14), and IgA nephropathy (15), may reflect the exceptionally aggressive inflammation in the glomeruli and consequently poor prognosis in this disease.

Crescentic glomerulonephritis comprises a spectrum of kidney disorders distinguished by rapid deterioration of kidney function and the histological hallmark of glomerular crescent formation, with anti-GBM disease representing the most severe form (16). Glomerular crescents are composed of fibrin, proliferating PECs, T cells, and macrophages. While the precise mechanism underlying crescent formation remains incompletely understood, current evidence suggests that Bowman’s capsule rupture plays a crucial role in its progression (12, 17–19). The first hit of crescent formation, also well documented, is the formation of glomerular immune complex either in situ or from the circulation that induces podocyte injury and PEC activation, often resulting in early glomerular crescent formation. The second hit was recently proposed such that T cells and macrophages surrounding the glomerulus can migrate into the urinary space following breaches in Bowman’s capsule, promoting crescent formation (18). Our current study also revealed that the severity of Bowman’s capsule rupture positively correlated with crescent proportion, particularly the cellular–fibrous crescents, in patients with anti-GBM disease. This suggests that Bowman’s capsule rupture may occur in the late stage of crescent formation, supporting the notion that the “outside-in” attack of inflammation cells is a driver of crescent progression.

We firstly explored the clinical and prognostic significance of Bowman’s capsule rupture in patients with anti-GBM disease in this study. The severity of Bowman’s capsule rupture showed a strong correlation with kidney function, demonstrating a graded association with the incidence of oligoanuria, eGFR, and serum creatinine on diagnosis. Antibody-mediated autoimmunity has been considered as the major cause of anti-GBM disease (20–22). Our current findings demonstrated that the levels of anti-GBM antibody increased in parallel with Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage, suggesting that Bowman’s capsule rupture might contribute to the pathogenesis of anti-GBM disease. In terms of prognosis, our results showed that Bowman’s capsule rupture, as a single and simple pathological parameter on kidney biopsy, has discriminative ability to predict outcomes for both kidney survival and kidney recovery in patients with anti-GBM disease. Moreover, the incorporation of Bowman’s capsule rupture could enhance the predictive performance of two previously reported prognostic models—Floyd’s class and RRS model (3, 4). A similar predictive value of Bowman’s capsule rupture has been observed in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis (13), suggesting its broader clinical relevance in crescentic glomerulonephritis.

Our study has limitations inherent to its retrospective design and small sample size due to disease rarity. Future multi-center studies with larger cohorts would be necessary to validate the role and characteristics of Bowman’s capsule rupture in anti-GBM disease.

In conclusion, Bowman’s capsule rupture is a distinct histopathological feature and a critical indicator of kidney injury in patients with anti-GBM disease. More importantly, this simple parameter alone demonstrates a strong predictive value for the kidney outcomes of patients. Routine quantitative assessment of Bowman’s capsule rupture percentage on kidney biopsies may offer potential benefits for its management.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Peking University First Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HK: Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis. C-xL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. X-jY: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. ZC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. M-hZ: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Validation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. X-yJ: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82270763 to XYJ, 82325009 to ZC, and 82090020 to M-hZ).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1655319/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1Decision tree analysis of Bowman’s capsule rupture (BCR) to predict kidney survival. Each box includes the number of patients who progressed into end-stage kidney disease (left)/the total number of patients.

Supplementary Figure 2Decision tree analysis of Bowman’s capsule rupture (BCR) to predict kidney recovery. Each box includes the number of patients obtaining kidney recovery (left)/the number of patients receiving initial renal replacement therapy (right) with the median time of kidney recovery (below).

References

1

CuiZZhaoMH. Advances in human antiglomerular basement membrane disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2011) 7:697–705. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.89

2

KuangHJiangNJiaXYCuiZZhaoMH. Epidemiology, clinical features, risk factors, and outcomes in anti-glomerular basement membrane disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. (2024) 23:103531. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2024.103531

3

FloydLBateSHadi KafagiABrownNScottJSrikantharajahMet al. Risk stratification to predict renal survival in anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2023) 34:505–14. doi: 10.1681/asn.2022050581

4

KuangHZhaoYYWangJWCuiZZhaoMHJiaXY. Evaluation of the risk prediction models in predicting kidney outcomes in antiglomerular basement membrane disease. Kidney Int Rep. (2024) 9:624–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2023.12.011

5

GlassockRJ. Estimating prognosis in anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2023) 34:361–2. doi: 10.1681/asn.0000000000000069

6

LazarethHHeniqueCLenoirOPuellesVGFlamantMBolléeGet al. The tetraspanin CD9 controls migration and proliferation of parietal epithelial cells and glomerular disease progression. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:3303. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11013-2

7

EymaelJSharmaSLoevenMAWetzelsJFMoorenFFlorquinSet al. CD44 is required for the pathogenesis of experimental crescentic glomerulonephritis and collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. (2018) 93:626–42. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.09.020

8

SickingEMFussAUhligSJirakPDijkmanHWetzelsJet al. Subtotal ablation of parietal epithelial cells induces crescent formation. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2012) 23:629–40. doi: 10.1681/asn.2011050449

9

MelicaMEAntonelliGSemeraroRAngelottiMLLugliGLandiniSet al. Differentiation of crescent-forming kidney progenitor cells into podocytes attenuates severe glomerulonephritis in mice. Sci Transl Med. (2022) 14(657):eabg3277. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abg3277

10

GercikOBilginESolmazDCakalagaogluFSaglamAAybiOet al. Histopathological subgrouping versus renal risk score for the prediction of end-stage renal disease in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. (2020) 79:675–6. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216742

11

HuSYJiaXYLiJNZhengXAoJLiuGet al. T cell infiltration is associated with kidney injury in patients with anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. Sci China Life Sci. (2016) 59:1282–9. doi: 10.1007/s11427-016-5030-9

12

ChenALeeKD'AgatiVDWeiCFuJGuanTJet al. Bowman’s capsule provides a protective niche for podocytes from cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest. (2018) 128:3413–24. doi: 10.1172/jci97879

13

HakroushSTampeDKorstenPStröbelPTampeB. Bowman’s capsule rupture links glomerular damage to tubulointerstitial inflammation in ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. (2021) 39 Suppl 129:27–31. doi: 10.55563/clinexprheumatol/7eol6d

14

DuanTZhuXZhaoQXiaoLHeLLiuHet al. Association of Bowman’s capsule rupture with prognosis in patients with lupus nephritis. J Nephrol. (2022) 35:1193–204. doi: 10.1007/s40620-022-01316-x

15

ZhaoQDuanTChenAHeLLiuHYuanSet al. Bowman’s capsule rupture and the Oxford MEST-C score in adult patients with Immunoglobulin a vasculitis nephritis: a single center experience. Ann Med. (2023) 55:2215538. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2023.2215538

16

JennetteJC. Rapidly progressive crescentic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. (2003) 63:1164–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00843.x

17

HarrisDWyattCMFogoABRoncoP. The Bowman’s shield: a tribute to translational science and Detlef Schlöndorff. Kidney Int. (2018) 94:448–50. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.07.001

18

KitchingARAlikhanMA. CD8+ cells and glomerular crescent formation: outside-in as well as inside-out. J Clin Invest. (2018) 128:3231–3. doi: 10.1172/jci122045

19

AllisonSJ. Breaches in the Bowman’s capsule and CD8(+) T cell infiltration in crescentic GN. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2018) 14:597. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0046-y

20

LernerRAGlassockRJDixonFJ. The role of anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody in the pathogenesis of human glomerulonephritis. J Exp Med. (1967) 126:989–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.126.6.989

21

KuangHShenCRJiaXYTanMYangXFCuiZet al. Autoantibodies against laminin-521 are pathogenic in anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. Kidney Int. (2023) 104:1124–34. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2023.07.023

22

KuangHLiuJJiaXYCuiZZhaoMH. Autoimmunity in anti-glomerular basement membrane disease: A review of mechanisms and prospects for immunotherapy. Am J Kidney Dis. (2023) 81:90–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.07.006

Summary

Keywords

anti-glomerular basement membrane disease, crescentic glomerulonephritis, Bowman’s capsule rupture, end-stage kidney disease, prognosis

Citation

Kuang H, Lin C-x, Yu X-j, Cui Z, Zhao M-h and Jia X-y (2025) Bowman’s capsule rupture and its clinical significance in patients with anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. Front. Immunol. 16:1655319. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1655319

Received

27 June 2025

Revised

16 November 2025

Accepted

20 November 2025

Published

04 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Zinnia P. Parra-Guillen, University of Navarra, Spain

Reviewed by

Renate Kain, Medical University of Vienna, Austria

Salvatore Mignano, Incyte Diagnostics, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Kuang, Lin, Yu, Cui, Zhao and Jia.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiao-yu Jia, constancej@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.