- Translational Medicine Center, Honghui Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, China

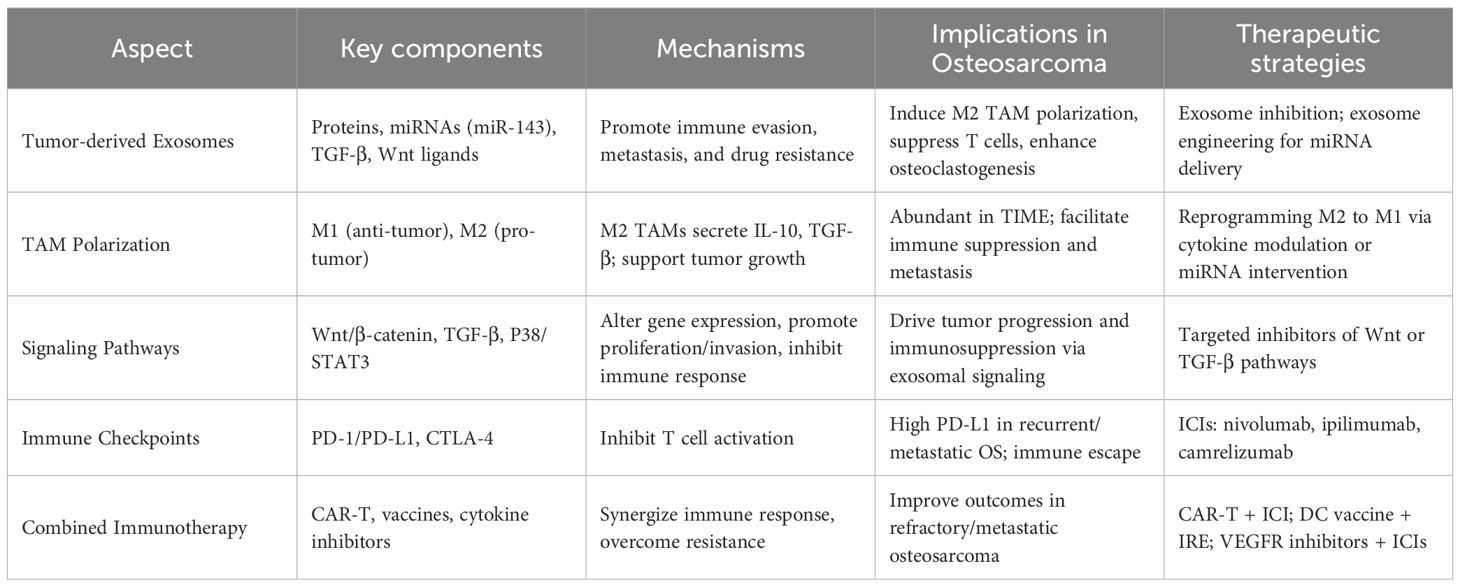

Osteosarcoma, the most common primary malignant bone tumor, poses significant clinical challenges due to its aggressive nature, high metastatic potential, and resistance to conventional therapies. Despite improvements in surgical and chemotherapeutic approaches, survival rates for relapsed or metastatic disease remain poor. Recent advances in understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) and exosome biology have uncovered critical mechanisms driving osteosarcoma progression, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), particularly the M2 phenotype, dominate the osteosarcoma immune landscape and contribute to immunosuppression through cytokine secretion and modulation of T cell function. Exosomes, as intercellular messengers, further exacerbate tumor progression by transporting oncogenic proteins, immunosuppressive factors (TGF-β), miRNAs, and drug-resistance molecules. These vesicles also influence critical signaling cascades including Wnt/β-catenin and TGF-β pathways, shaping both local and systemic tumor responses. This review delineates the roles of immune cells and tumor-derived exosomes in osteosarcoma biology and evaluates emerging immunotherapeutic strategies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T cells, tumor vaccines, cytokine-targeted agents, and combination therapies. We highlight ongoing clinical trials, numerical efficacy metrics, and the translational promise of exosome-based diagnostics and therapeutics. Ultimately, integrated approaches targeting both the TIME and exosome-mediated mechanisms may yield more effective and durable treatments for osteosarcoma patients.

1 Introduction

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignant bone tumor, accounting for approximately 20% of all primary malignant bone tumors worldwide (1). It predominantly affects children, adolescents, and elderly individuals. Traditional amputation yields a 5-year survival rate of <20% (2), but advancements in surgery, radiotherapy (RT), chemotherapy (CT), targeted therapy, and multidisciplinary approaches have improved survival to 60%–80% (2). Despite this, osteosarcoma retains the highest mortality among bone malignancies (3), with metastatic/recurrent cases showing <30% long-term survival (4), necessitating more effective therapies.

Recent insights into the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) have spurred progress in immunotherapy, including tumor vaccines, cytokine targeting, immune checkpoint inhibition, adoptive cell therapy, and combinatorial strategies (5, 6). However, their efficacy in osteosarcoma requires further exploration. Concurrently, exosome research has revealed their role in intercellular communication, transporting proteins, signaling factors, and miRNAs to modulate recipient cell function (7). Tumor-derived exosomes also contribute to drug resistance by expelling anticancer agents (8). Exosome analysis aids in early diagnosis, treatment guidance, and prognosis assessment, while engineered exosomes serve as potential drug/gene delivery vehicles. This review focuses on the immune microenvironment of osteosarcoma, discussing the immune therapeutic strategies associated with it, the translational applications of these strategies in osteosarcoma treatment, and evaluating the potential challenges and opportunities. We also look forward to future research directions in this field.

2 Immune microenvironment and exosome in osteosarcoma

2.1 The immune microenvironment of osteosarcoma

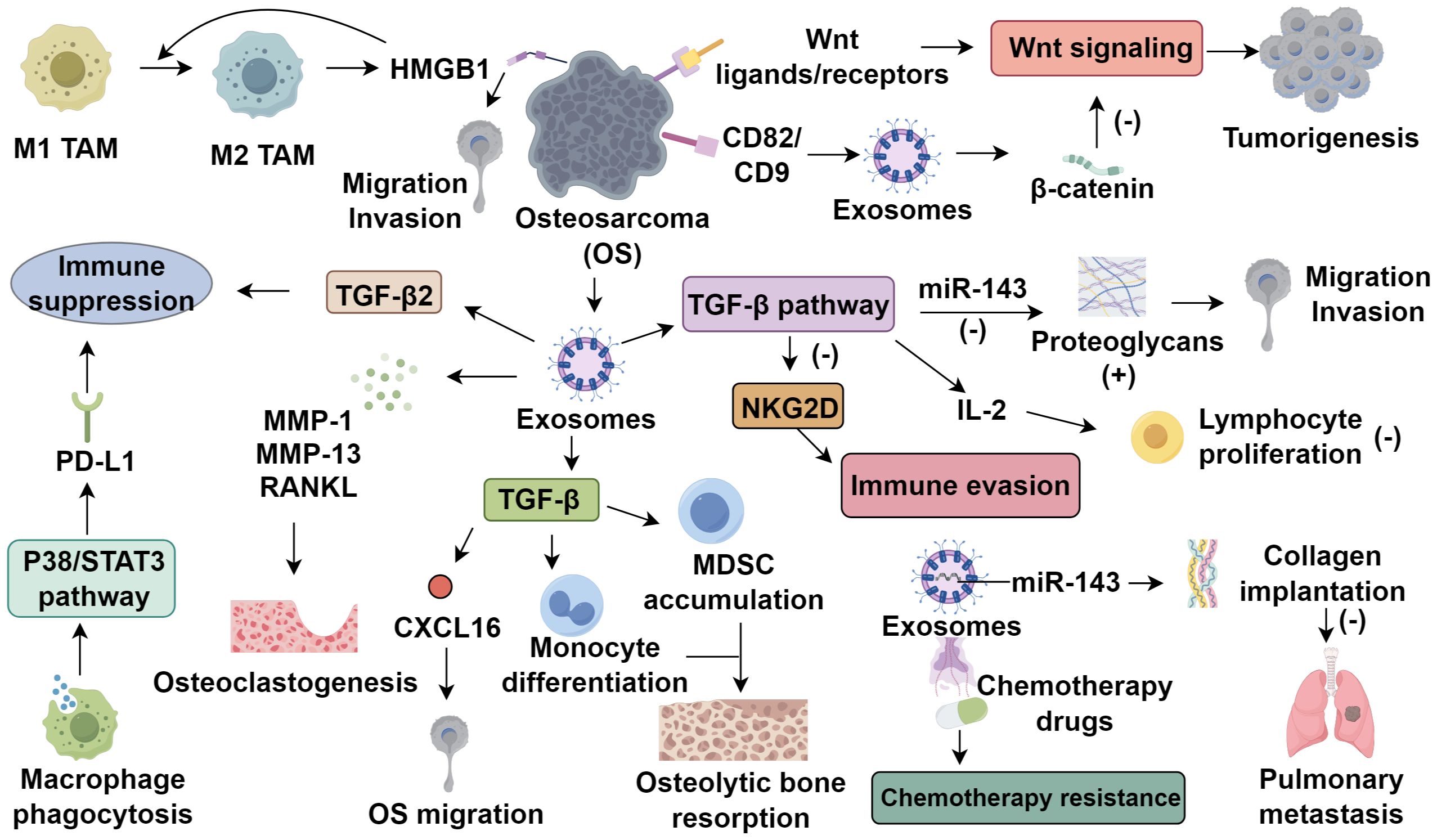

TIME in osteosarcoma is a complex system consisting of tumor cells, immune cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and extracellular components. These elements interact through cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors (9). In osteosarcoma tissues, monocytes and macrophages represent 70-80% of bone marrow cells, with dendritic cells (DCs) making up less than 5% (10). Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are the dominant immune cell type, constituting over 50% of the immune cell population (11, 12). TAMs are classified into M1 and M2 types. M1 TAMs exhibit pro-inflammatory and anti-tumor functions and are typically associated with improved prognosis (13). In contrast, M2 TAMs, induced primarily by IL-4 and IL-13 through activation of the STAT6 pathway, adopt an immunosuppressive phenotype characterized by the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors (14). These M2-polarized TAMs play pivotal roles in osteosarcoma progression by secreting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which promotes neovascularization and tumor perfusion, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which contributes to extracellular matrix deposition and tumor-associated fibrosis. Furthermore, they suppress cytotoxic T lymphocyte function and facilitate osteosarcoma cell invasion and metastasis (15). The polarization of M1 to M2 TAMs plays a significant role in osteosarcoma progression. M2 TAMs induce high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) expression in osteosarcoma cells, promoting migration and invasion, while HMGB1 further enhances M2 polarization (16). In addition, tumor-derived exosomes containing TGF-β2 can induce M2 polarization, thereby sustaining an immune-suppressive environment (17). Reversing M2 TAMs to M1 has emerged as a promising therapeutic approach (18). Additionally, cancer stem cells (CSCs) interact with TAMs to maintain osteosarcoma development (19), macrophage phagocytic activity modulates their polarization through the P38/STAT3 axis, promoting PD-L1 expression and enhancing immune evasion (20).

2.2 The role of exosomes in the tumor microenvironment of osteosarcoma

Exosomes, 40–100 nm vesicles released upon multivesicular body fusion with the plasma membrane, carry proteins, double-stranded DNA, and various RNAs (21). Their biogenesis is governed by Rab GTPases (Rab27a/b), ceramide metabolism, and tumor-associated pH changes (22, 23), and their membrane is enriched with scaffolding proteins (tubulin, annexins, Alix, TSG101), tetraspanins (CD9, CD63), and cell-specific markers such as MHC-I (24, 25). They encapsulate signaling molecules involved in oncogenic cascades, including Wnt/β-catenin and TGF-β pathways (26). Tumor microenvironmental stressors, notably hypoxia and acidosis, significantly enhance exosome release (27). In osteosarcoma, hypoxia-induced HIF-1α upregulates Rab22A, promoting multivesicular body formation and enriching exosomes with pro-angiogenic and immunosuppressive factors, thereby facilitating metastasis (27–29). Tumor-derived exosomes critically shape the TME, enhancing angiogenesis, metastasis, and immune evasion (30–32). Garimella et al. (33) characterized osteosarcoma-derived exosomes in a bioluminescent murine model using transmission electron microscopy. These exosomes contain matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1, MMP-13) and RANKL, contributing to matrix degradation, osteoclastogenesis, and potential prognostic value (34). Exosomal TGF-β modulates CXCL16 in osteoclasts and promotes monocyte-to-MDSC differentiation, exacerbating osteolytic disease (35, 36). CD9 modulates osteoclast differentiation and metastatic tropism, with blockade by KMC8 inhibiting osteoclastogenesis (37, 38). Additionally, intracellular mediators such as calcium, cAMP, and P2X7 receptor activation regulate exosome secretion (39–41). Therapeutic strategies targeting exosome biogenesis or function, such as Rab27a knockdown, CD9 blockade, or RANKL neutralization, may disrupt osteolytic signaling and preserve bone integrity in osteosarcoma (Figure 1).

3 The role of exosome-mediated signaling pathways in osteosarcoma

3.1 Wnt signaling pathway

Targeted therapy of the Wnt pathway in tumors has drawn significant interest. Chen et al. (42) found that osteosarcoma cell lines expressing Wnt ligands/receptors exhibit differentiation potential via autocrine Wnt signaling. Kansara et al. (43) reported that Wnt inhibitory factor 1 knockout increased osteosarcoma incidence in mice, suggesting Wnt activation promotes tumorigenesis. Conversely, Cleton-Jansen et al. (44) observed Wnt downregulation in osteosarcoma specimens versus osteoblastomas and mesenchymal stem cells. Studies also noted elevated Dkk-1 expression at tumor margins, correlating with invasiveness; Dkk-1 blockade inhibited osteosarcoma cell proliferation via activation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway (45). Besides, osteoblast-derived exosomes effectively inhibited the proliferation of osteosarcoma cells and promoted their mineralization via RG4/Wnt signaling pathway (46). These seemingly contradictory findings, Wnt pathway activation associated with tumor progression in some studies and suppression in others, highlight the context-dependent nature of Wnt signaling in osteosarcoma. Several factors may account for this dichotomy, including tumor heterogeneity, differences between early and late disease stages, and the interplay between canonical (β-catenin-dependent) and non-canonical Wnt pathways (44, 47). These findings not only emphasize the dualistic nature of Wnt signaling but also underscore the key role of exosomes in modulating and distributing Wnt pathway activity within the osteosarcoma microenvironment, informing future targeted therapies.

3.2 TGF-β signaling pathway

TGF-β regulates cell proliferation, differentiation, extracellular matrix production, angiogenesis, apoptosis, and immune responses (48). Li et al. (49) demonstrated in 60 osteosarcoma specimens that TGF-β1 upregulates proteoglycans by suppressing miR-143, enhancing tumor invasiveness and metastasis. In vitro studies have revealed that TGF-β1 enhances the migratory capacity of various osteosarcoma cell lines, a phenomenon likely linked to its ability to induce epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)-like changes. Moreover, TGF-β1 has been implicated in promoting angiogenesis within the osteosarcoma microenvironment (48). Exosomal TGF-β1 suppresses IL-2-induced lymphocyte proliferation, exhibiting 1400-fold greater immunosuppression than soluble TGF-β1 (50, 51). Tumor−derived exosomal TGF−β1 engages TGF−β receptor II on NK and CD8+ T cells, activating the SMAD2/3 pathway and leading to transcriptional repression of NKG2D, a critical activating receptor required for cytolytic granule release. This downregulation diminishes immune recognition and killing of osteosarcoma cells, allowing tumors to escape immune surveillance (52–54). Kawano et al. (55) found anti-TGF-β antibodies inhibit osteosarcoma proliferation and stimulate systemic immunity, suggesting therapeutic potential. Beyond their immunosuppressive effects, exosomal TGF-β1 particles represent promising delivery vehicles for targeted immunomodulation. Engineering exosomes to either block or reverse TGF-β1-mediated immunosuppression—such as loading antagonists or small interfering RNAs against TGF-β signaling—may offer a novel therapeutic avenue in overcoming immune evasion and restoring anti-tumor immunity in osteosarcoma (56).

3.3 Exosome-mediated miRNAs

Emerging evidence highlights the pivotal role of exosomal miRNAs in osteosarcoma progression and immune regulation. miR-143 suppresses pulmonary metastases in murine osteosarcoma models (57), promoting apoptosis and reducing tumor growth upon upregulation (58). Exosomal packaging enhances the stability and intercellular transport of miRNAs, enabling them to function as gene transfer agents. Shimbo et al. (59) showed that synthetic miR-143, delivered via exosomes from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, significantly reduced OS metastatic potential, with greater efficacy than conventional transfection. Other exosomal miRNAs further contribute to OS pathogenesis (60). Exosomal miR-21, miR-21, commonly overexpressed in OS, promotes proliferation, metastasis, drug resistance, and immune evasion via PTEN suppression and PI3K/AKT signaling (61, 62). Similarly, exosomal miR-148a enhances tumor progression by targeting PTEN and DNMT1 (63, 64). These findings underscore the diverse and critical functions of exosome-associated miRNAs in shaping the TIME and facilitating osteosarcoma pathogenesis. Exosome membranes harbor tumor-associated antigens, MHC molecules, and co-stimulatory signals, capable of eliciting cytotoxic T cell responses (65, 66). OS cells often downregulate MHC class molecules, impairing antigen presentation. Tumor-derived membranous vesicles (Texo) isolated from osteosarcoma cells can sensitize DCs, activating T cells to suppress tumor growth (59). These insights support the therapeutic potential of exosome-based strategies in osteosarcoma immunotherapy.

3.4 Exosomes and tumor drug resistance

The resistance of tumor cells to docetaxel is positively correlated with the amount of exosome secretion (8). Shedden et al. (67) observed that exosomes encapsulate and expel a variety of anti-cancer drugs, a phenomenon observed in multiple tumors, which may be related to the sensitivity of the tumors to anti-cancer drugs. Chemotherapeutic drugs can be expelled from tumor cells via exosomes, while antibody-based targeted drugs can also be neutralized. In addition to passive drug sequestration and efflux, exosomes actively contribute to chemoresistance by transporting drug-resistance-related proteins and regulatory RNAs. Notably, exosomes derived from chemoresistant osteosarcoma cells have been shown to carry functional P-glycoprotein (P-gp/ABCB1), a membrane-associated ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter (68, 69). Upon transfer to sensitive cells, exosomal P-gp can confer multidrug resistance by enhancing drug efflux capacity, thereby reducing intracellular drug accumulation and therapeutic efficacy. Moreover, these exosomes derived from chemoresistant osteosarcoma cells facilitate the development of drug resistance by delivering miR-331-3p and activating autophagy pathways. Targeted suppression of miR-331-3p expression may represent a potential strategy to overcome chemoresistance in osteosarcoma (70). Chemotherapy plays an important role in the treatment of osteosarcoma. Therefore, exploring the specific mechanisms by which osteosarcoma cell exosomes encapsulate, transport, and excrete chemotherapy drugs and their metabolic products is crucial for improving the efficacy of chemotherapy in osteosarcoma patients. Targeting exosome biogenesis or blocking the uptake of drug-resistant exosomes represents a promising strategy to overcome chemotherapy resistance in osteosarcoma.

4 Immunotherapy for osteosarcoma

4.1 Immune checkpoint inhibition

T cell activation, crucial for antitumor immunity, relies on TCR-MHC and CD28-CD80/CD86 co-stimulation (71). Immune checkpoints such as PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibit these pathways by by engaging PD-L1 or B7 ligands, leading to immune evasion and establishing the rationale for immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). PD-1 modulates autoimmunity, while PD-L1, expressed on tumor cells, inversely correlates with prognosis (72). Osteosarcoma studies show elevated PD-L1 serum levels, often exceeding PD-1, with high PD-L1 linked to recurrence/metastasis (73, 74), suggesting its regulation as a therapeutic target. ICIs act by blocking checkpoint proteins, releasing immune suppression and activating tumor cell killing. In osteosarcoma models, PD-1 inhibition promotes M1/M2 macrophage polarization in lung metastases, inducing regression (75). Anti-PD-L1 antibodies enhance NK cell cytotoxicity against osteosarcoma (76), suggesting PD-1/PD-L1 blockade may benefit patients. Clinical trials show PD-L1 expression/amplification correlates with ICI response, though optimal thresholds remain undefined (77, 78). Avelumab (anti-PD-L1) is under evaluation in a Phase II trial (NCT03006848), while apatinib plus camrelizumab improved PFS in PD-L1-positive advanced osteosarcoma (79). Another PD-1-targeting trial (NCT04359550) demonstrates socazolimab’s efficacy in postoperative maintenance. CTLA-4, a CD28 homolog, binds B7 ligands, enabling immune escape (80), observed in osteosarcoma. Anti-CTLA-4 enhances CTL activity (81), supporting CTLA-4 inhibition as a potential therapeutic strategy. However, ICI efficacy is inconsistent in osteosarcoma, likely due to its low tumor mutational burden (TMB) and heterogeneous PD-L1 expression, limiting neoantigen availability and immune recognition (82, 83). Notably, tumor-derived exosomes carrying membrane-bound PD-L1 exert systemic immunosuppressive effects by engaging PD-1 on T cells independent of direct tumor–T cell contact, contributing to therapy resistance and immune evasion in various cancers, including osteosarcoma (84). This mechanism suggests that PD-L1–positive exosomes may serve as both a biomarker for ICI resistance and a potential therapeutic target in osteosarcoma.

4.2 Adoptive cell therapy

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT), particularly chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapy, genetically engineers autologous T cells to recognize tumor-specific antigens, thereby inducing robust antitumor responses (85). While effective in hematological malignancies, CAR-T therapy faces challenges in solid tumors like osteosarcoma due to antigen heterogeneity, limited persistence, and the immunosuppressive TME (86). GD2, frequently overexpressed in osteosarcoma, has emerged as a key target. GD2-directed CAR-T cells demonstrate potent cytotoxicity, with Phase I trials confirming safety and feasibility (87, 88). However, PD-L1/PD-1–mediated immunosuppression and intratumoral variability in GD2 expression contribute to immune evasion and antigen escape (89). Moreover, dynamic downregulation of GD2 following immune pressure further reduces CAR-T efficacy, emphasizing the need for multi-targeting strategies (90). The TME, enriched in M2-like tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), regulatory T cells (Tregs), and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), releases suppressive cytokines (TGF-β, IL-10) and depletes essential nutrients (arginine, tryptophan), collectively impairing CAR-T function (91, 92). Overcoming these barriers may require combinatorial approaches involving checkpoint blockade, cytokine modulation, or metabolic reprogramming. Additionally, CAR-T cell trafficking is hindered by a dense extracellular matrix, abnormal vasculature, and lack of chemokine gradients (91). To improve tumor infiltration, strategies include engineering CAR-T cells to express chemokine receptors such as CCR2 (responsive to CCL2), or combining therapy with matrix-degrading enzymes or low-dose radiotherapy (91). Beyond GD2, emerging targets include alkaline phosphatase 1 (ALP-1), specific to metastatic osteosarcoma, and interleukin-11 receptor α (IL-11Rα), a bone-associated antigen. Preclinical data suggest ALP-1- and IL-11Rα-targeted CAR-T cells offer enhanced tumor specificity and cytotoxicity (89, 93, 94). Despite promise, further research is needed to optimize CAR-T efficacy in osteosarcoma.

4.3 Tumor vaccines

Tumor vaccines are an emerging immunotherapeutic strategy that harness tumor-associated antigens to elicit specific immune responses capable of targeting malignant cells. Among these, dendritic cell (DC) vaccines have shown the most clinical promise in osteosarcoma (95). As professional antigen-presenting cells, DCs prime cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), amplifying antitumor immunity. DC vaccines can be derived autologously, from patient-derived blood or bone marrow, or allogeneically, using donor-derived DCs. In both cases, DCs are pulsed with tumor antigens ex vivo prior to reinfusion. Although most DC-based vaccines remain in early-phase clinical trials, the advancement of agents such as DCVax-L to Phase III underscores their therapeutic potential (96). However, DC vaccine efficacy in osteosarcoma remains modest, prompting investigation into combinatorial regimens. Notably, irreversible electroporation (IRE) has been shown to enhance antigen release and immunogenicity, thereby augmenting DC vaccine efficacy and systemic antitumor responses (97). In parallel, peptide vaccines—constructed from tumor-associated or neoantigen-derived epitopes—offer a more defined and potentially personalized immunotherapeutic platform. Neoantigen-based approaches are particularly promising due to their high immunogenicity and reduced risk of central tolerance, and are now being explored in sarcomas (98, 99). Furthermore, exosome-loaded vaccines have emerged as a novel strategy to enhance antigen presentation and immune priming, making them attractive candidates for future osteosarcoma vaccine development (100).

4.4 Targeting cytokines

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a pivotal cytokine regulating endothelial cell growth, differentiation, and angiogenesis, promoting tumor progression by supplying oxygen and nutrients. Despite clinical trials of VEGF-targeting drugs (regorafenib, cabozantinib, sorafenib, pazopanib, bevacizumab), most show no significant median survival time (MST) improvement, indicating limited efficacy (101). However, some demonstrate therapeutic potential, such as regorafenib, currently under evaluation in trials (NCT02389244, EUCTR2013-003910-42, EUCTR2019-002629-31, NCT04698785, NCT04803877). DUFFAUD et al. (102) reported regorafenib significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) in advanced osteosarcoma, supported by subsequent studies (103, 104). Apatinib, a selective VEGFR2 inhibitor, suppresses Sox2 via STAT3, reducing doxorubicin resistance (105), and induces apoptosis by inhibiting VEGFR2/STAT3/BCL-2 signaling (106). Ongoing trials (NCT06125171, NCT05277480, ChiCTR2200062550) and phase II data support its use in chemotherapy-resistant advanced osteosarcoma (107). Similarly, surufatinib shows promise in a trial (NCT05106777) for chemotherapy-refractory cases, with ongoing recruitment (108). Beyond pharmacotherapy, VEGFR2 gene silencing offers a novel strategy for pulmonary metastasis. YU et al. (109) proposed a genetic circuit delivering VEGFR2 siRNA via plasmid DNA, enabling targeted lung delivery for metastatic osteosarcoma treatment. In addition to soluble VEGF, tumor-derived exosomes have been shown to encapsulate and transport VEGF molecules, thereby facilitating localized angiogenic signaling in a protected vesicular form. These VEGF-positive exosomes can be internalized by endothelial cells in the tumor microenvironment, enhancing vascular proliferation and remodeling (110). In osteosarcoma, such exosomal delivery may contribute to aberrant neovascularization and metastatic spread, highlighting exosomal VEGF as a novel target for anti-angiogenic therapies.

4.5 Combination immunotherapy

Combination immunotherapy for osteosarcoma has garnered significant attention, with studies highlighting synergistic effects of dual checkpoint inhibition. LUSSIER et al. (111) demonstrated that anti-PD-L1 antibodies reduced PD-1 expression on CD8+ T cells while increasing CTLA-4 in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), suggesting complementary roles in suppressing CTL responses. Metastatic osteosarcoma mouse model showed complete tumor control and prevented immune escape in 50% of cases with PD-L1/CTLA-4 blockade. D’ANGELO et al. (112) reported 49% survival with nivolumab/ipilimumab versus 32% with nivolumab alone in metastatic sarcoma. Combining ICIs with other modalities enhances efficacy. Anti-CTLA-4 antibodies paired with dendritic cell vaccines improved responses in osteosarcoma models (113), while ICIs augmented CAR-T cell activity by reversing T cell exhaustion (114). Targeted combinations also show promise. GD2 antibodies with IL-2/GM-CSF boosted solid tumor responses (115, 116), while GD2 plus cisplatin induced ER-mediated apoptosis in osteosarcoma (117). Low-dose doxorubicin enhanced dendritic cell efficacy via immunogenic cell death (118). These findings underscore combination therapy’s potential to improve response rates and durability, particularly for treatment-resistant cases. As mechanistic understanding advances, multimodal approaches may redefine osteosarcoma management (Table 1).

5 Conclusion

Osteosarcoma’s complex TIME and exosome-mediated interactions present both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic innovation. The immunosuppressive milieu, driven by M2-polarized TAMs and exosome-facilitated signaling, underscores the need for strategies that reprogram the TIME while targeting tumor-intrinsic pathways. Immunotherapy, particularly ICIs and CAR-T cells, has shown encouraging but variable efficacy, necessitating biomarker-driven patient stratification and combinatorial approaches to enhance durability. Exosomes, as mediators of metastasis, drug resistance, and intercellular communication, offer dual utility as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic vehicles, especially when engineered for targeted drug or miRNA delivery.

Key challenges include overcoming antigen heterogeneity, mitigating immune evasion, and optimizing exosome-based delivery systems. Future research should prioritize elucidating mechanisms of exosome-mediated immune suppression, developing exosome-mimetic nanotherapies, refining CAR-T designs for solid tumors, and integrating immunotherapy with targeted agents or chemotherapy to exploit immunogenic cell death. Clinical translation will depend on robust preclinical models and adaptive trial designs to evaluate emerging combinations. By bridging insights from TIME biology and exosome science, this field holds transformative potential to improve outcomes for osteosarcoma patients.

Author contributions

JW: Writing – original draft. KS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Zhao X, Wu Q, Gong X, Liu J, and Ma Y. Osteosarcoma: a review of current and future therapeutic approaches. BioMed Eng Online. (2021) 20:24. doi: 10.1186/s12938-021-00860-0

2. Bernthal NM, Federman N, Eilber FR, Nelson SD, Eckardt JJ, Eilber FC, et al. Long-term results (>25 years) of a randomized, prospective clinical trial evaluating chemotherapy in patients with high-grade, operable osteosarcoma. Cancer. (2012) 118:5888–93. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27651

3. Xu Y, Shi F, Zhang Y, Yin M, Han X, Feng J, et al. Twenty-year outcome of prevalence, incidence, mortality and survival rate in patients with Malignant bone tumors. Int J Cancer. (2024) 154:226–40. doi: 10.1002/ijc.34694

4. Moukengue B, Lallier M, Marchandet L, Baud’huin M, Verrecchia F, Ory B, et al. Origin and therapies of osteosarcoma. Cancers (Basel). (2022) 14:3503. doi: 10.3390/cancers14143503

5. Xie H, Xi X, Lei T, Liu H, and Xia Z. CD8(+) T cell exhaustion in the tumor microenvironment of breast cancer. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1507283. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1507283

6. Deng Y, Shi M, Yi L, Naveed Khan M, Xia Z, and Li X. Eliminating a barrier: Aiming at VISTA, reversing MDSC-mediated T cell suppression in the tumor microenvironment. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e37060. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37060

7. Vlassov AV, Magdaleno S, Setterquist R, and Conrad R. Exosomes: current knowledge of their composition, biological functions, and diagnostic and therapeutic potentials. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2012) 1820:940–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.03.017

8. Corcoran C, Rani S, O’Brien K, O’Neill A, Prencipe M, Sheikh R, et al. Docetaxel-resistance in prostate cancer: evaluating associated phenotypic changes and potential for resistance transfer via exosomes. PLoS One. (2012) 7:e50999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050999

9. Zhu T, Han J, Yang L, Cai Z, Sun W, Hua Y, et al. Immune microenvironment in osteosarcoma: components, therapeutic strategies and clinical applications. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:907550. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.907550

10. Zhou Y, Yang D, Yang Q, Lv X, Huang W, Zhou Z, et al. et al: Single-cell RNA landscape of intratumoral heterogeneity and immunosuppressive microenvironment in advanced osteosarcoma. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:6322. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20059-6

11. Cersosimo F, Lonardi S, Bernardini G, Telfer B, Mandelli GE, Santucci A, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages in osteosarcoma: from mechanisms to therapy. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:5207. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155207

12. Huang Q, Liang X, Ren T, Huang Y, Zhang H, Yu Y, et al. The role of tumor-associated macrophages in osteosarcoma progression - therapeutic implications. Cell Oncol (Dordr). (2021) 44:525–39. doi: 10.1007/s13402-021-00598-w

13. Xu J, Ding L, Mei J, Hu Y, Kong X, Dai S, et al. Dual roles and therapeutic targeting of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor microenvironments. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2025) 10:268. doi: 10.1038/s41392-025-02325-5

14. Bernstein ZJ, Shenoy A, Chen A, Heller NM, and Spangler JB. Engineering the IL-4/IL-13 axis for targeted immune modulation. Immunol Rev. (2023) 320:29–57. doi: 10.1111/imr.13230

15. Luo ZW, Liu PP, Wang ZX, Chen CY, and Xie H. Macrophages in osteosarcoma immune microenvironment: implications for immunotherapy. Front Oncol. (2020) 10:586580. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.586580

16. Hou C, Lu M, Lei Z, Dai S, Chen W, Du S, et al. HMGB1 positive feedback loop between cancer cells and tumor-associated macrophages promotes osteosarcoma migration and invasion. Lab Invest. (2023) 103:100054. doi: 10.1016/j.labinv.2022.100054

17. Wolf-Dennen K, Gordon N, and Kleinerman ES. Exosomal communication by metastatic osteosarcoma cells modulates alveolar macrophages to an M2 tumor-promoting phenotype and inhibits tumoricidal functions. Oncoimmunology. (2020) 9:1747677. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1747677

18. Anand N, Peh KH, and Kolesar JM. Macrophage repolarization as a therapeutic strategy for osteosarcoma. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:2858. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032858

19. Raggi C, Mousa HS, Correnti M, Sica A, and Invernizzi P. Cancer stem cells and tumor-associated macrophages: a roadmap for multitargeting strategies. Oncogene. (2016) 35:671–82. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.132

20. Lin J, Xu A, Jin J, Zhang M, Lou J, Qian C, et al. MerTK-mediated efferocytosis promotes immune tolerance and tumor progression in osteosarcoma through enhancing M2 polarization and PD-L1 expression. Oncoimmunology. (2022) 11:2024941. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2021.2024941

21. Kumar MA, Baba SK, Sadida HQ, Marzooqi SA, Jerobin J, Altemani FH, et al. Extracellular vesicles as tools and targets in therapy for diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2024) 9:27. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01735-1

22. Nambara S, Masuda T, Hirose K, Hu Q, Tobo T, Ozato Y, et al. Rab27b, a regulator of exosome secretion, is associated with peritoneal metastases in gastric cancer. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. (2023) 20:30–9. doi: 10.21873/cgp.20362

23. Xu M, Ji J, Jin D, Wu Y, Wu T, Lin R, et al. The biogenesis and secretion of exosomes and multivesicular bodies (MVBs): Intercellular shuttles and implications in human diseases. Genes Dis. (2023) 10:1894–907. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2022.03.021

24. Hu Q, Su H, Li J, Lyon C, Tang W, Wan M, et al. Clinical applications of exosome membrane proteins. Precis Clin Med. (2020) 3:54–66. doi: 10.1093/pcmedi/pbaa007

25. Waqas MY, Javid MA, Nazir MM, Niaz N, Nisar MF, Manzoor Z, et al. Extracellular vesicles and exosome: insight from physiological regulatory perspectives. J Physiol Biochem. (2022) 78:573–80. doi: 10.1007/s13105-022-00877-6

26. Ruksha T and Palkina N. Role of exosomes in transforming growth factor-β-mediated cancer cell plasticity and drug resistance. Explor Target Antitumor Ther. (2025) 6:1002322. doi: 10.37349/etat.2025.1002322

27. Mu Y, Yang M, Liu J, Yao Y, Sun H, and Zhuang J. Exosomes in hypoxia: generation, secretion, and physiological roles in cancer progression. Front Immunol. (2025) 16:1537313. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1537313

28. Pierrevelcin M, Fuchs Q, Lhermitte B, Messé M, Guérin E, Weingertner N, et al. Focus on hypoxia-related pathways in pediatric osteosarcomas and their druggability. Cells. (2020) 9:1998. doi: 10.3390/cells9091998

29. Papanikolaou NA, Kakavoulia M, Ladias C, and Papavassiliou AG. The ras-related protein RAB22A interacts with hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells in hypoxia. Mol Biol Rep. (2024) 51:564. doi: 10.1007/s11033-024-09516-3

30. Chen S, Sun J, Zhou H, Lei H, Zang D, and Chen J. New roles of tumor-derived exosomes in tumor microenvironment. Chin J Cancer Res. (2024) 36:151. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2024.02.05

31. Wang H, Liu S, Zhan J, Liang Y, and Zeng X. Shaping the immune-suppressive microenvironment on tumor-associated myeloid cells through tumor-derived exosomes. Int J Cancer. (2024) 154:2031–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.34921

32. Gong X, Chi H, Strohmer DF, Teichmann AT, Xia Z, and Wang Q. Exosomes: A potential tool for immunotherapy of ovarian cancer. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:1089410. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1089410

33. Garimella R, Eskew J, Bhamidi P, Vielhauer G, Hong Y, Anderson HC, et al. Biological characterization of preclinical Bioluminescent Osteosarcoma Orthotopic Mouse (BOOM) model: A multi-modality approach. J Bone Oncol. (2013) 2:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2012.12.005

34. De Martino V, Rossi M, Battafarano G, Pepe J, Minisola S, and Del Fattore A. Extracellular vesicles in osteosarcoma: antagonists or therapeutic agents? Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:12586. doi: 10.3390/ijms222212586

35. Ota K, Quint P, Weivoda MM, Ruan M, Pederson L, Westendorf JJ, et al. Transforming growth factor beta 1 induces CXCL16 and leukemia inhibitory factor expression in osteoclasts to modulate migration of osteoblast progenitors. Bone. (2013) 57:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.07.023

36. Xiang X, Poliakov A, Liu C, Liu Y, Deng ZB, Wang J, et al. Induction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by tumor exosomes. Int J Cancer. (2009) 124:2621–33. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24249

37. Ruan S, Rody WJ Jr., Patel SS, Hammadi LI, Martin ML, de Faria LP, et al. Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B is enriched in CD9-positive extracellular vesicles released by osteoclasts. Extracell Vesicles Circ Nucl Acids. (2023) 4:518–29. doi: 10.20517/evcna.2023.38

38. Yi T, Kim HJ, Cho JY, Woo KM, Ryoo HM, Kim GS, et al. Tetraspanin CD9 regulates osteoclastogenesis via regulation of p44/42 MAPK activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2006) 347:178–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.061

39. Golia MT, Gabrielli M, and Verderio C. P2X7 receptor and extracellular vesicle release. Int J Mol Sci (2023) 24:9805. doi: 10.3390/ijms24129805

40. Xia L, Wang X, Yao W, Wang M, and Zhu J. Lipopolysaccharide increases exosomes secretion from endothelial progenitor cells by toll-like receptor 4 dependent mechanism. Biol Cell. (2022) 114:127–37. doi: 10.1111/boc.202100086

41. Ludwig N, Yerneni SS, Menshikova EV, Gillespie DG, and Jackson EK. Whiteside TLJSr: Simultaneous inhibition of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation triggers a multi-fold increase in secretion of exosomes: possible role of 2′. 3′-cAMP. (2020) 10:6948. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63658-5

42. Chen C, Zhao M, Tian A, Zhang X, Yao Z, and Ma X. Aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling drives proliferation of bone sarcoma cells. Oncotarget. (2015) 6:17570–83. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4100

43. Kansara M, Tsang M, Kodjabachian L, Sims NA, Trivett MK, Ehrich M, et al. Wnt inhibitory factor 1 is epigenetically silenced in human osteosarcoma, and targeted disruption accelerates osteosarcomagenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. (2009) 119:837–51. doi: 10.1172/JCI37175

44. Cleton-Jansen A-M, Anninga JK, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, Romeo S, Oosting J, Egeler RM, et al. Profiling of high-grade central osteosarcoma and its putative progenitor cells identifies tumourigenic pathways. Br J Cancer. (2009) 101:1909–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605405

45. Xie Q, Shen Y, Yang Y, Liang J, Wu T, Hu C, et al. Identification of XD23 as a potent inhibitor of osteosarcoma via downregulation of DKK1 and activation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway. iScience. (2024) 27:110758. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2024.110758

46. Leng Y, Li J, Long Z, Li C, Zhang L, Huang Z, et al. Osteoblast-derived exosomes promote osteogenic differentiation of osteosarcoma cells via URG4/Wnt signaling pathway. Bone. (2024) 178:116933. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2023.116933

47. Miranda-Carboni GA and Krum SA. Targeting WNT5B and WNT10B in osteosarcoma. Oncotarget. (2024) 15:535–40. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.28617

48. Lamora A, Talbot J, Mullard M, Brounais-Le Royer B, Redini F, and Verrecchia F. TGF-β Signaling in bone remodeling and osteosarcoma progression. J Clin Med. (2016) 5:535–40. doi: 10.3390/jcm5110096

49. Li F, Li S, and Cheng T. TGF-β1 promotes osteosarcoma cell migration and invasion through the miR-143-versican pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2014) 34:2169–79. doi: 10.1159/000369660

50. Clayton A, Mitchell JP, Court J, Mason MD, and Tabi Z. Human tumor-derived exosomes selectively impair lymphocyte responses to interleukin-2. Cancer Res. (2007) 67:7458–66. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3456

51. Hosseini R, Hosseinzadeh N, Asef-Kabiri L, Akbari A, Ghezelbash B, Sarvnaz H, et al. Small extracellular vesicle TGF-β in cancer progression and immune evasion. Cancer Gene Ther. (2023) 30:1309–22. doi: 10.1038/s41417-023-00638-7

52. Jia J. TGF-β-enriched exosomes from acute myeloid leukemia activate smad2/3–MMP2 and ERK1/2 signaling to promote leukemic cell proliferation, migration, and immune modulation. Curr Issues Mol Biol. (2025) 47:690. doi: 10.3390/cimb47090690

53. Del Vecchio F, Martinez-Rodriguez V, Schukking M, Cocks A, Broseghini E, and Fabbri M. Professional killers: The role of extracellular vesicles in the reciprocal interactions between natural killer, CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells and tumour cells. J Extracell Vesicles. (2021) 10:. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12075

54. Clayton A, Mitchell JP, Court J, Linnane S, Mason MD, and Tabi Z. Human tumor-derived exosomes down-modulate NKG2D expression. J Immunol. (2008) 180:7249–58. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7249

55. Kawano M, Itonaga I, Iwasaki T, Tsuchiya H, and Tsumura H. Anti-TGF-β antibody combined with dendritic cells produce antitumor effects in osteosarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2012) 470:2288–94. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2299-2

56. Rodrigues-Junior DM, Tsirigoti C, Lim SK, Heldin CH, and Moustakas A. Extracellular vesicles and transforming growth factor β Signaling in cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2022) 10:849938. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.849938

57. Zhang P, Zhang J, Quan H, Wang J, and Liang Y. MicroRNA-143 expression inhibits the growth and the invasion of osteosarcoma. J Orthop Surg Res. (2022) 17:236. doi: 10.1186/s13018-022-03127-z

58. Zhang H, Cai X, Wang Y, Tang H, Tong D, and Ji F. microRNA-143, down-regulated in osteosarcoma, promotes apoptosis and suppresses tumorigenicity by targeting Bcl-2. Oncol Rep. (2010) 24:1363–9. doi: 10.3892/or_00000994

59. Shimbo K, Miyaki S, Ishitobi H, Kato Y, Kubo T, Shimose S, et al. Exosome-formed synthetic microRNA-143 is transferred to osteosarcoma cells and inhibits their migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2014) 445:381–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.007

60. Dong S, Xu H, Kong X, Bai Y, Hou X, Liu F, et al. C-X-C chemokine receptor family genes in osteosarcoma: expression profiles, regulatory networks, and functional impact on tumor progression. Hereditas. (2025) 162:194. doi: 10.1186/s41065-025-00569-3

61. Yang J, Zou Y, and Jiang D. Honokiol suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis via regulation of the miR−21/PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in human osteosarcoma cells. Int J Mol Med. (2018) 41:1845–54. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3433

62. Wang S, Ma F, Feng Y, Liu T, and He S. Role of exosomal miR−21 in the tumor microenvironment and osteosarcoma tumorigenesis and progression (Review). Int J Oncol. (2020) 56:1055–63. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2020.4992

63. Chang Y, Zhao Y, Gu W, Cao Y, Wang S, Pang J, et al. Bufalin inhibits the differentiation and proliferation of cancer stem cells derived from primary osteosarcoma cells through mir-148a. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2015) 36:1186–96. doi: 10.1159/000430289

64. Zhang H, Wang Y, Xu T, Li C, Wu J, He Q, et al. Increased expression of microRNA-148a in osteosarcoma promotes cancer cell growth by targeting PTEN. Oncol Lett. (2016) 12:3208–14. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5050

65. Nanru P. Immunomodulatory effects of immune cell-derived extracellular vesicles in melanoma. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1442573. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1442573

66. Wang S and Shi Y. Exosomes derived from immune cells: the new role of tumor immune microenvironment and tumor therapy. Int J Nanomedicine. (2022) 17:6527. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S388604

67. Shedden K, Xie XT, Chandaroy P, Chang YT, and Rosania GR. Expulsion of small molecules in vesicles shed by cancer cells: association with gene expression and chemosensitivity profiles. Cancer Res. (2003) 63:4331–7.

68. Yang Q, Xu J, Gu J, Shi H, Zhang J, Zhang J, et al. Extracellular vesicles in cancer drug resistance: roles, mechanisms, and implications. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2022) 9:e2201609. doi: 10.1002/advs.202201609

69. Martínez-Delgado P, Lacerenza S, Obrador-Hevia A, Lopez-Alvarez M, Mondaza-Hernandez JL, Blanco-Alcaina E, et al. Cancer stem cells in soft-tissue sarcomas. Cells. (2020) 9:1449. doi: 10.3390/cells9061449

70. Meng C, Yang Y, Feng W, Ma P, and Bai R. Exosomal miR-331-3p derived from chemoresistant osteosarcoma cells induces chemoresistance through autophagy. J Orthop Surg Res. (2023) 18:892. doi: 10.1186/s13018-023-04338-8

71. Havel JJ, Chowell D, and Chan TA. The evolving landscape of biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. (2019) 19:133–50. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0116-x

72. Yi M, Niu M, Xu L, Luo S, and Wu K. Regulation of PD-L1 expression in the tumor microenvironment. J Hematol Oncol. (2021) 14:10. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-01027-5

73. Hashimoto K, Nishimura S, and Akagi M. Characterization of PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint expression in osteosarcoma. Diagnostics (Basel). (2020) 10:10. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10080528

74. Toda Y, Kohashi K, Yamada Y, Yoshimoto M, Ishihara S, Ito Y, et al. PD-L1 and IDO1 expression and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in osteosarcoma patients: comparative study of primary and metastatic lesions. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. (2020) 146:2607–20. doi: 10.1007/s00432-020-03242-6

75. Dhupkar P, Gordon N, Stewart J, and Kleinerman ES. Anti-PD-1 therapy redirects macrophages from an M2 to an M1 phenotype inducing regression of OS lung metastases. Cancer Med. (2018) 7:2654–64. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1518

76. Zhang ML, Chen L, Li YJ, and Kong DL. PD−L1/PD−1 axis serves an important role in natural killer cell−induced cytotoxicity in osteosarcoma. Oncol Rep. (2019) 42:2049–56. doi: 10.3892/or.2019.7299

77. Boye K, Longhi A, Guren T, Lorenz S, Næss S, Pierini M, et al. Pembrolizumab in advanced osteosarcoma: results of a single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2021) 70:2617–24. doi: 10.1007/s00262-021-02876-w

78. Wen Y, Tang F, Tu C, Hornicek F, Duan Z, and Min L. Immune checkpoints in osteosarcoma: Recent advances and therapeutic potential. Cancer Lett. (2022) 547:215887. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2022.215887

79. Xie L, Xu J, Sun X, Guo W, Gu J, Liu K, et al. Apatinib plus camrelizumab (anti-PD1 therapy, SHR-1210) for advanced osteosarcoma (APFAO) progressing after chemotherapy: a single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial. J Immunother Cancer. (2020) 8:e000798. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000798

80. Sznol M and Melero I. Revisiting anti-CTLA-4 antibodies in combination with PD-1 blockade for cancer immunotherapy. Ann Oncol. (2021) 32:295–7. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.018

81. Roy D, Gilmour C, Patnaik S, and Wang LL. Combinatorial blockade for cancer immunotherapy: targeting emerging immune checkpoint receptors. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1264327. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1264327

82. He M, Abro B, Kaushal M, Chen L, Chen T, Gondim M, et al. Tumor mutation burden and checkpoint immunotherapy markers in primary and metastatic synovial sarcoma. Hum Pathol. (2020) 100:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2020.04.007

83. Jiang T, Zhang J, Zhao S, Zhang M, Wei Y, Liu X, et al. MCT4: a key player influencing gastric cancer metastasis and participating in the regulation of the metastatic immune microenvironment. J Transl Med. (2025) 23:276. doi: 10.1186/s12967-025-06279-8

84. Yin Z, Yu M, Ma T, Zhang C, Huang S, Karimzadeh MR, et al. Mechanisms underlying low-clinical responses to PD-1/PD-L1 blocking antibodies in immunotherapy of cancer: a key role of exosomal PD-L1. J Immunother Cancer. (2021) 9:e001698. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001698

85. Schultz L. Chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy for pediatric B-ALL: narrowing the gap between early and long-term outcomes. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:1985. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01985

86. Li S, Zhang H, and Shang G. Current status and future challenges of CAR-T cell therapy for osteosarcoma. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1290762. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1290762

87. Corti C, Venetis K, Sajjadi E, Zattoni L, Curigliano G, and Fusco N. CAR-T cell therapy for triple-negative breast cancer and other solid tumors: preclinical and clinical progress. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. (2022) 31:593–605. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2022.2054326

88. Kaczanowska S, Murty T, Alimadadi A, Contreras CF, Duault C, Subrahmanyam PB, et al. Immune determinants of CAR-T cell expansion in solid tumor patients receiving GD2 CAR-T cell therapy. Cancer Cell. (2024) 42:35–51.e38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.11.011

89. Zhu J, Simayi N, Wan R, and Huang W. CAR T targets and microenvironmental barriers of osteosarcoma. Cytotherapy. (2022) 24:567–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2021.12.010

90. Wiebel M, Kailayangiri S, Altvater B, Meltzer J, Grobe K, Kupich S, et al. Surface expression of the immunotherapeutic target G(D2) in osteosarcoma depends on cell confluency. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). (2021) 4:e1394. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.1394

91. Kankeu Fonkoua LA, Sirpilla O, Sakemura R, Siegler EL, and Kenderian SS. CAR T cell therapy and the tumor microenvironment: Current challenges and opportunities. Mol Ther Oncolytics. (2022) 25:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2022.03.009

92. Liu Z, Zhou Z, Dang Q, Xu H, Lv J, Li H, et al. Immunosuppression in tumor immune microenvironment and its optimization from CAR-T cell therapy. Theranostics. (2022) 12:6273–90. doi: 10.7150/thno.76854

93. Mensali N, Köksal H, Joaquina S, Wernhoff P, Casey NP, Romecin P, et al. ALPL-1 is a target for chimeric antigen receptor therapy in osteosarcoma. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:3375. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39097-x

94. Mu H, Zhang Q, Zuo D, Wang J, Tao Y, Li Z, et al. (2025). Methionine intervention induces PD-L1 expression to enhance the immune checkpoint therapy response in MTAP-deleted osteosarcoma. Cell Reports Medicine. 6:101977. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2025.101977

95. Lu Y, Zhang J, Chen Y, Kang Y, Liao Z, He Y, et al. Novel immunotherapies for osteosarcoma. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:830546. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.830546

96. Zhong R, Ling X, Cao S, Xu J, Zhang B, Zhang X, et al. Safety and efficacy of dendritic cell-based immunotherapy (DCVAC/LuCa) combined with carboplatin/pemetrexed for patients with advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer without oncogenic drivers. ESMO Open. (2022) 7:100334. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100334

97. Yu J, Sun H, Cao W, Song Y, and Jiang Z. Research progress on dendritic cell vaccines in cancer immunotherapy. Exp Hematol Oncol. (2022) 11:3. doi: 10.1186/s40164-022-00257-2

98. Li H, Sui X, Wang Z, Fu H, Wang Z, Yuan M, et al. A new antisarcoma strategy: multisubtype heat shock protein/peptide immunotherapy combined with PD-L1 immunological checkpoint inhibitors. Clin Transl Oncol. (2021) 23:1688–704. doi: 10.1007/s12094-021-02570-4

99. Dagher R, Long LM, Read EJ, Leitman SF, Carter CS, Tsokos M, et al. Pilot trial of tumor-specific peptide vaccination and continuous infusion interleukin-2 in patients with recurrent Ewing sarcoma and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: an inter-institute NIH study. Med Pediatr Oncol. (2002) 38:158–64. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1303

100. Zhou J, Xu L, Yang P, Lu Y, Lin S, and Yuan G. The exosomal transfer of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived miR-1913 inhibits osteosarcoma progression by targeting NRSN2. Am J Transl Res. (2021) 13:10178–92.

101. Assi T, Watson S, Samra B, Rassy E, Le Cesne A, Italiano A, et al. Targeting the VEGF pathway in osteosarcoma. Cells. (2021) 10:1240. doi: 10.3390/cells10051240

102. Duffaud F, Mir O, Boudou-Rouquette P, Piperno-Neumann S, Penel N, Bompas E, et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib in adult patients with metastatic osteosarcoma: a non-comparative, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. (2019) 20:120–33. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30742-3

103. Davis LE, Bolejack V, Ryan CW, Ganjoo KN, Loggers ET, Chawla S, et al. Randomized double-Blind phase II study of regorafenib in patients with metastatic osteosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. (2019) 37:1424–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02374

104. Duffaud F, Blay JY, Le Cesne A, Chevreau C, Boudou-Rouquette P, Kalbacher E, et al. Regorafenib in patients with advanced Ewing sarcoma: results of a non-comparative, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre Phase II study. Br J Cancer. (2023) 129:1940–8. doi: 10.1038/s41416-023-02413-9

105. Tian ZC, Wang JQ, and Ge H. Apatinib ameliorates doxorubicin-induced migration and cancer stemness of osteosarcoma cells by inhibiting Sox2 via STAT3 signalling. J Orthop Translat. (2020) 22:132–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2019.07.003

106. Liu K, Ren T, Huang Y, Sun K, Bao X, Wang S, et al. Apatinib promotes autophagy and apoptosis through VEGFR2/STAT3/BCL-2 signaling in osteosarcoma. Cell Death Dis. (2017) 8:e3015. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.422

107. Xie L, Xu J, Sun X, Tang X, Yan T, Yang R, et al. Apatinib for advanced osteosarcoma after failure of standard multimodal therapy: an open label phase II clinical trial. Oncologist. (2019) 24:e542–50. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0542

108. Zhang X, Pan Q, Peng R, Xu B, Hong D, and Que Y. A phase II study of surufatinib in patients with osteosarcoma and soft tissue sarcoma who have experienced treatment failure with standard chemotherapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol. (2023) 41:e23540–e23540. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.e23540

109. Yu L, Fan G, Wang Q, Zhu Y, Zhu H, Chang J, et al. In vivo self-assembly and delivery of VEGFR2 siRNA-encapsulated small extracellular vesicles for lung metastatic osteosarcoma therapy. Cell Death Dis. (2023) 14:626. doi: 10.1038/s41419-023-06159-3

110. Ahmadi M and Rezaie J. Tumor cells derived-exosomes as angiogenenic agents: possible therapeutic implications. J Transl Med. (2020) 18:249. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02426-5

111. Lussier DM, Johnson JL, Hingorani P, and Blattman JN. Combination immunotherapy with α-CTLA-4 and α-PD-L1 antibody blockade prevents immune escape and leads to complete control of metastatic osteosarcoma. J Immunother Cancer. (2015) 3:21. doi: 10.1186/s40425-015-0067-z

112. D’Angelo SP, Mahoney MR, Van Tine BA, Atkins J, Milhem MM, Jahagirdar BN, et al. Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab treatment for metastatic sarcoma (Alliance A091401): two open-label, non-comparative, randomised, phase 2 trials. Lancet Oncol. (2018) 19:416–26. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30006-8

113. Yang Y, Zhou Y, Wang J, Zhou Y, Watowich SS, and Kleinerman ES. CD103+ cDC1 dendritic cell vaccine therapy for osteosarcoma lung metastases. Cancers (Basel). (2024) 16:3251. doi: 10.3390/cancers16193251

114. Park JA and Cheung N-KV. Promise and challenges of T cell immunotherapy for osteosarcoma. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:12520. doi: 10.3390/ijms241512520

115. Mora J, Modak S, Kinsey J, Ragsdale CE, and Lazarus HM. GM-CSF, G-CSF or no cytokine therapy with anti-GD2 immunotherapy for high-risk neuroblastoma. Int J Cancer. (2024) 154:1340–64. doi: 10.1002/ijc.34815

116. Rohner C. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: A review of macrophage immunotherapies across cancer types. Urnst. (2025) 9:1–12. doi: 10.26685/urncst.700

117. Zhu W, Mao X, Wang W, Chen Y, Li D, Li H, et al. Anti-ganglioside GD2 monoclonal antibody synergizes with cisplatin to induce endoplasmic reticulum-associated apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells. Pharmazie. (2018) 73:80–6. doi: 10.1691/ph.2018.7836

Keywords: osteosarcoma, tumor-associated macrophages, exosome, immunosuppression, immune checkpoint inhibitors, immunotherapy

Citation: Wang J and Shi K (2025) Role of tumor-derived exosomes and immune cells in osteosarcoma progression and targeted therapy. Front. Immunol. 16:1658358. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1658358

Received: 02 July 2025; Accepted: 12 November 2025; Revised: 06 November 2025;

Published: 26 November 2025.

Edited by:

Wei Chong, Shandong Provincial Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Patrice Penfornis, University of Mississippi Medical Center, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Wang and Shi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kuohao Shi, c2hpa2gxMjE2QDE2My5jb20=

Jingchao Wang

Jingchao Wang Kuohao Shi

Kuohao Shi