- 1Department of Urology, Peking University Third Hospital, Beijing, China

- 2Department of Hernia and Abdominal Wall Surgery, Peking University People’s Hospital, Beijing, China

Kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) exhibit a higher incidence of neoplasms compared to the general population, primarily due to the prolonged administration of immunosuppressive agents and viral infections. In China, the primary type of tumor among KTRs is urothelial carcinoma (UC), which lacks specific clinical manifestations. Accurate diagnosis necessitates the integration of multiple diagnostic modalities, while therapeutic approaches must judiciously balance oncological control with the preservation of renal function, thereby presenting a considerable challenge to the health of KTRs. This article provides a comprehensive review of the epidemiological characteristics, risk factors, diagnostic methodologies, and therapeutic strategies associated with urothelial carcinoma post kidney transplantation (KT), aiming to enhance healthcare professionals’ understanding of this condition and improve patient management.

Introduction

KT constitutes a highly efficacious intervention for end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Advancements in technology, coupled with the extensive application of immunosuppressive agents, have markedly enhanced both the quality of life and long-term survival rates of recipients. Nonetheless, there has been a concomitant rise in tumor incidence, with the overall occurrence of malignant neoplasms in KTRs being two to three times greater than that observed in the general population (1, 2), which has become one of the major causes of death in KTRs after surgery (3–5). Among the malignancies observed in KTRs, lymphoma and skin cancer are the most prevalent, with genitourinary system tumors following in frequency (6–8). Recently, the incidence of UC post KT has attracted considerable scholarly attention. Notably, there is variability in the reported incidence rates across various studies. A study conducted in Asia reports that the incidence rates of urinary bladder urothelial carcinoma (UBUC) and upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) in KTRs are 25.5 times and 129.5 times higher, respectively, compared to the general population (9). Among 2,345 KTRs at a specific center, 20 patients were identified with urogenital cancers, including 13 cases of bladder or ureteral cancer (7). A separate retrospective analysis of 5,920 KTRs revealed that 13 cases (0.2%) were diagnosed with UC, of which 8 were bladder cancer (BC), yielding an incidence rate of 0.13%. This rate is significantly higher than the 0.02% observed in the general population (10). In Chinese KTRs, de novo urothelial carcinoma is notably prevalent, representing over 40% of all post-transplant malignant tumors (11–13). Presently, there is a limited understanding of the incidence characteristics, risk factors, and treatment strategies for UC following KT. This article seeks to systematically summarize the relevant literature to provide theoretical references and guidance for clinical practitioners.

Pathogenic characteristics

The majority of UC following KT have been documented to originate from the native urinary tract, but UC can also develop from the allograft (14, 15). Hematuria is a prevalent symptom; however, in KT patients, the diagnosis of tumors may be delayed compared to non-KT patients presenting with hematuria. A comparative study of UTUC patients in KT and non-KT cohorts revealed that the incidence rates of gross and microscopic hematuria in the KT group were 43% and 64%, respectively, which were lower than the corresponding rates of 76% and 86% observed in the non-KT group. Additionally, KT patients exhibiting hematuria demonstrated a higher incidence of non-organ-confined tumors (16). Wu MJ et al.’s study found that the most common initial symptoms in patients were painless gross hematuria and chronic urinary tract infection (UTI), often with bladder irritation symptoms like frequent urination, urgency, and dysuria (17). It is worth noting that abnormal urine cytology may also serve as the initial manifestation of UC in KTRs, accounting for 47.8% of cases (18). However, Wu MJ et al. observed that among patients who had undergone a minimum of three urine cytology examinations before biopsy, only 7 cases (23.3%) were strongly suspected of UC, indicating a high false-negative rate for urine cytology examinations (16). Furthermore, certain patients may present with symptoms associated with urinary tract obstruction, such as hydronephrosis resulting from ureteral tumors. This can lead to clinical manifestations including flank pain, oliguria, anuria, and compromised renal function, all of which significantly jeopardize the patients’ quality of life and prognosis.

In KTRs, UC is frequently high-stage, high-grade, and aggressive. Research indicates that 60% of UC cases in KTRs reach stage pT2 or higher, with 83% being high-grade (19). Compared to non-transplant patients, a higher percentage of female transplant recipients have UTUC staging above pT2 (20). Pathological types may include squamous differentiation and carcinoma sarcomatodes ingredients (21). In KTRs, those with UTUC who test positive for the polyomavirus large T antigen (LTAg) tend to develop the disease earlier (7). UC linked to BK polyomavirus (BKPyV) shows distinct pathological traits, including Glandular differentiation and micropapillary structures, with higher immunohistochemical positivity for LTAg, p53, and p16. Micropapillary UC, a rare and aggressive subtype, makes up 0.6%–1% of cases in the general population but accounts for 60% of cases in KTRs with BKPyV history. It features small clusters of tumor cells surrounded by lacunae, often with lymphovascular invasion and carcinoma in situ (22).

In Chinese KTRs, UC predominantly manifests as multifocal and bilateral. Notably, patients who utilize traditional Chinese medicine exhibit a significantly elevated risk of developing UC, with a higher prevalence observed among female patients (23–25). The onset of UC generally occurs within the first six years following transplantation, which is earlier compared to some Western countries. This discrepancy may be attributed to the frequency of post-transplant monitoring (26, 27). Furthermore, the incidence of UC in the upper urinary tract is greater than in the bladder among Chinese KTRs, contrasting with the pattern observed in dialysis patients (12, 28). In Western countries, UC in RTRs is predominantly bladder cancer, which stands in sharp contrast to the situation in China (23). Due to their immunosuppressed state, KTRs experience faster progression and widespread recurrence of UC compared to the general population. Studies have shown that the five-year recurrence rate following transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) is 77.7% in KTRs, and 38% in non-kidney transplant patients (29).

Risk factors

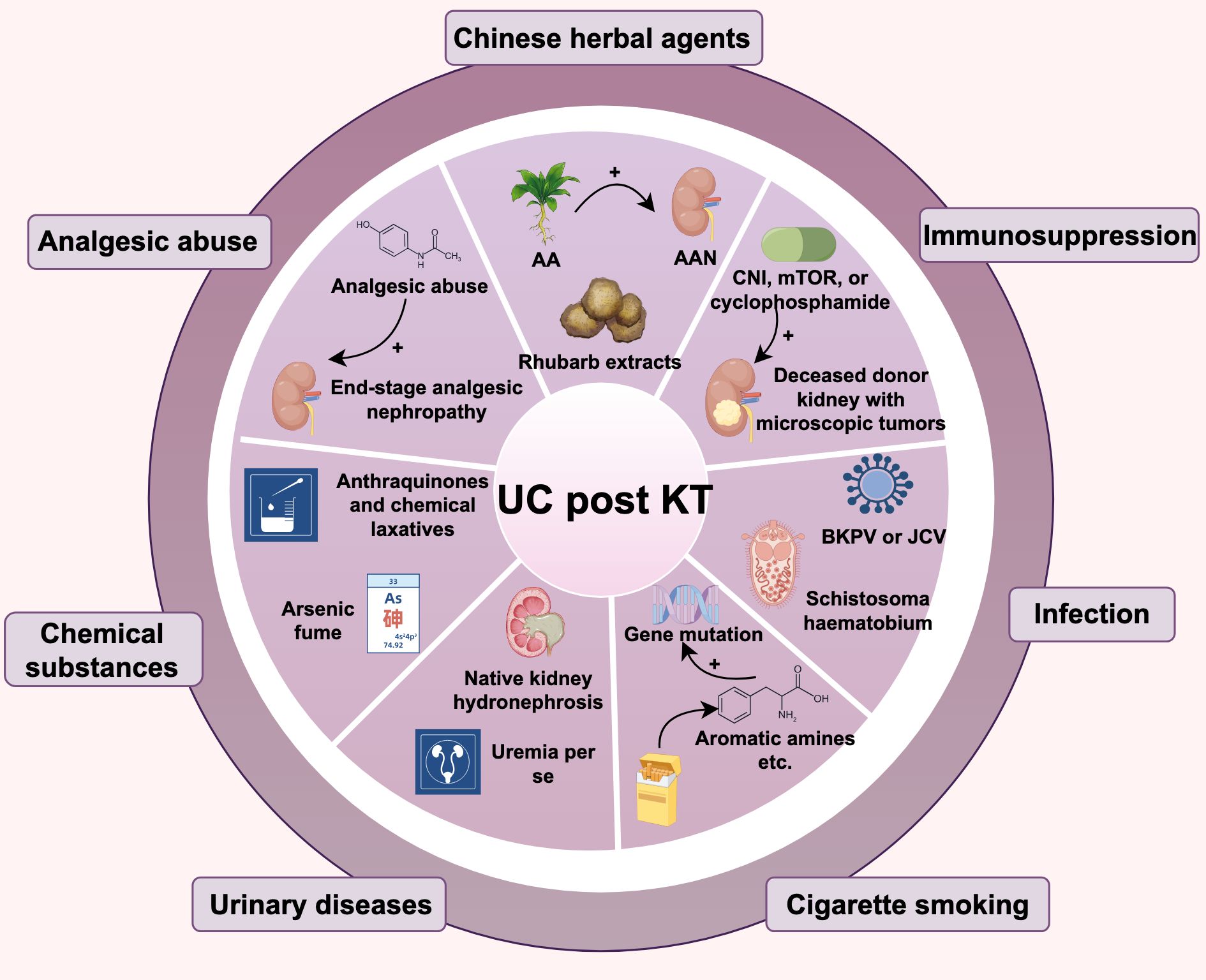

There are various risk factors for KTRs developing UC, including the use of traditional Chinese medicine, immunosuppression, and viral infections, etc. As shown in Figure 1.

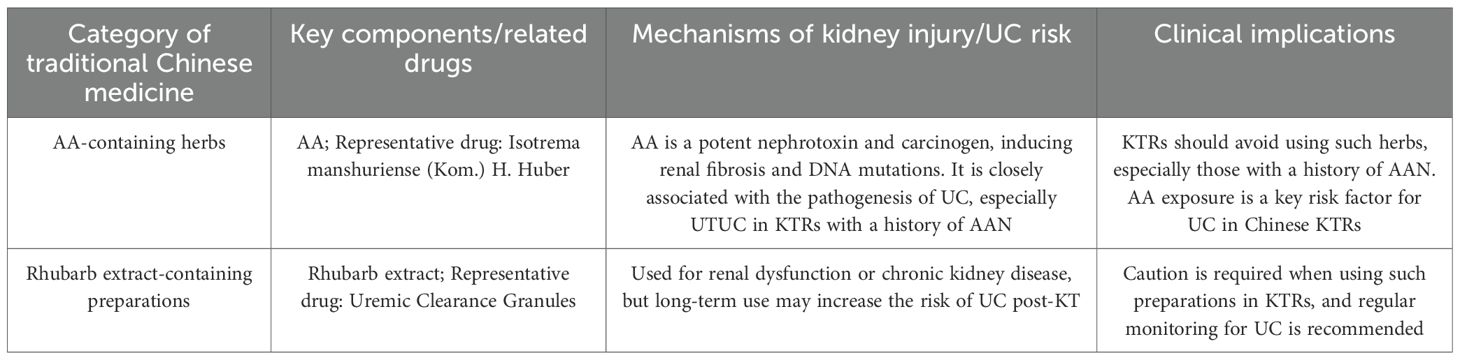

Chinese herbal agents

Aristolochic acid (AA) is a potent human nephrotoxin and carcinogen that plays a key role in the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis and UC, often found in traditional Chinese medicine for digestion and weight loss. It’s also used in ESRD patients to reduce serum creatinine (30). AA exposure may explain the higher rates of UC post-transplant in the Chinese population (25, 31), especially among KTRs with a history of Aristolochic Acid Nephropathy (AAN), who face a greater risk of primary kidney UTUC (32). Traditional Chinese medicines with AA, like Isotrema manshuriense (Kom.) H. Huber, may raise UC risk in KTRs. KTRs should be cautious about herbal ingredients’ impact on kidney function and cancer risk, particularly those with AA. In addition, Rhubarb extracts are also key components in certain traditional formulations, like uremic clearance granules. It is mainly used for renal dysfunction or chronic kidney disease, and may also cause UC post KT. Thus, overlooking other Chinese herbal products is unwise, as they too can have serious effects (23, 33), as shown in Table 1. In western countries, the etiological factor of Chinese herbal medicine intake is rarely mentioned. Instead, the common etiological factors for UC after renal transplantation in these countries are more closely associated with the use of immunosuppressants, abuse of analgesics, and other related factors. The impact of Chinese herbal medicine intake on the development of this cancer is far less significant than that in China (23).

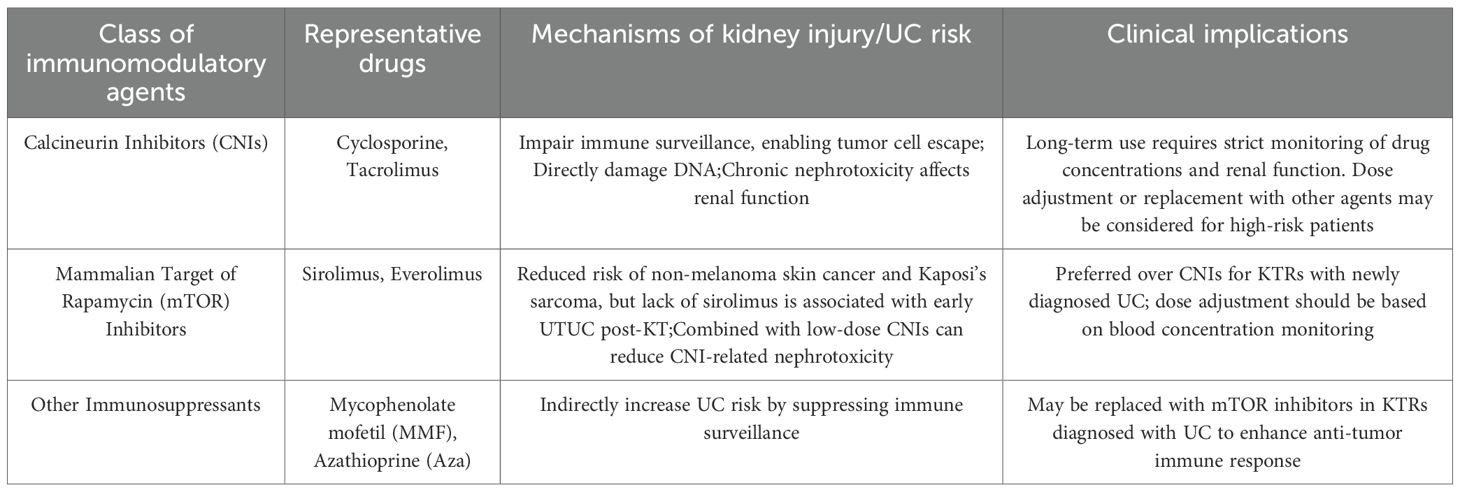

Immunosuppression

Evidence indicates that immunosuppressive therapy significantly raises cancer risk in KTRs (34). While these agents prevent kidney rejection, they also impair immune surveillance, allowing tumor cells to evade detectionand and clearance by the immune system, thus increasing UC risk (35). Additionally, long-term use of calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) like cyclosporine and tacrolimus, as well as mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors can directly damage DNA, further elevating UC risk (36). However, the lack of immunosuppressants, particularly sirolimus, is also linked to UC post KT. Lai HY et al. found early UTUC post KT was associated with not using sirolimus, which correlated with improved disease-free survival (DFS). And high levels of 7-(deoxyadenosin-N6-yl)aristolactam I (dA-AL-I) in matched normal tissues suggest AA exposure and could be a predictive and prognostic biomarker for new UTUC cases post KT (37). In addition, donor transmission, like a deceased transplant kidney with hidden microtumors, can lead to cancer growth after immunosuppressive therapy (38). Thus, it’s crucial to balance anti-rejection and anti-cancer treatments.

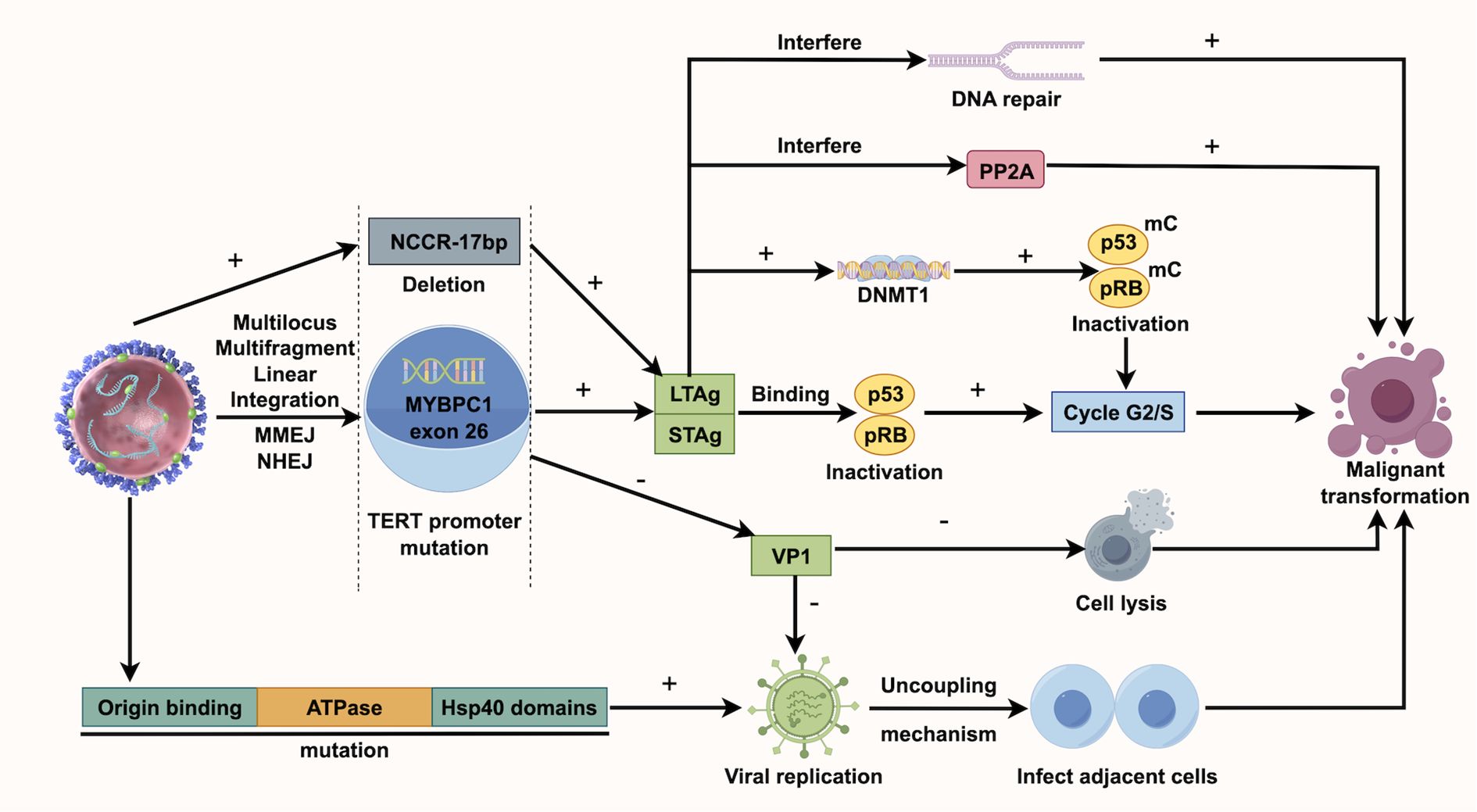

Virus infection

KTRs face a higher risk of viral infections due to immunosuppressive therapy, which may contribute to UC development (39). Human polyomavirus (HPyV), a non-enveloped double-stranded DNA virus, can integrate into the host genome, causing cell cycle disruptions and gene mutations, thereby increasing UC risk (34). BK polyomavirus (BKPV), a common HPyV, usually remains latent in healthy individuals but can reactivate and replicate in KTRs due to prolonged immunosuppressive treatment (40, 41). BKPV’s carcinogenic mechanism may involve its encoded Large T Antigen (LTAg), which can bind to and inactivate the host’s tumor suppressor genes p53 and pRB, resulting in unchecked cell cycle progression and tumor development (42). Chu YH et al. discovered that TAg-positive UC exhibited BKPV integration and higher levels of p16 and p53 compared to TAg-negative UC. Additionally, TAg-positive UC was more likely to present at advanced stages (50% T3-T4), associated with lymph node metastasis (50%), and had a higher UC-specific mortality rate (50%) (43). Kenan DJ et al. discovered that in KTRs with high-grade UC, BKPV disrupts VP1 protein expression and viral replication, meanwhile, deletions occur in the non-coding control region (NCCR). They suggest BKPV contributes to UC by disrupting cell cycle regulation and enhancing genetic instability (44). According to Yan L et al., all instances of polyomavirus-positive UC appeared more than 9 years following transplantation, indicating that the ‘time lapse’ could significantly influence polyomavirus-associated UC and calls for continuous observation (7). Jin Y et al. studied BKPyV integration in the bladder cancer of KTRs using whole-genome and viral capture sequencing. They identified a unique multi-site, multi-fragment linear integration pattern, unlike earlier models, possibly involving microhomology end joining (MMEJ) and nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ). The number of integration sites might correlate with tumor invasiveness, suggesting that monitoring viral load could help prevent related cancers (45). Figure 2 illustrates the BKPV’s mechanism of action. Besides, John cunningham virus (JCV) is believed to be linked to UC. While its carcinogenic role in the general population isn’t fully established, case reports in KTRs suggest JCV’s involvement in UC, as JCV DNA is frequently found in tumor tissues and is closely associated with tumor development (46). It should be noted that much of the current evidence on the roles of BKPV and JCV in carcinogenesis is primarily drawn from studies of bladder cancer rather than urothelial carcinoma more broadly.

Toxin and native kidney hydronephrosis

ESRD patients’ urine contains toxins that can lead to UC (47). Most ESRD patients, whether or not they have had a kidney transplant, experience decreased urine output, leading to prolonged retention of metabolic toxins such as aromatic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and inflammatory mediators in the bladder mucosa. This persistent exposure induces chronic oxidative stress and DNA damage in urothelial cells, creating a pro-carcinogenic microenvironment. Additionally, anuria reduces the elimination of potential carcinogens, such as aristolochic acid metabolites and viral particles that may accumulate in the bladder tissue over time. The bladder, positioned downstream in the urinary tract, has a larger surface area than the upper tract. KT could increase urine flow flushes the bladder. Ho CJ et al. propose this might partly account for the higher UC incidence in KTRs, with UTUC being more common than UBUC (19). Hydronephrosis is also linked to UC development due to urine stasis, recurrent UTI, chronic inflammation of the urinary tract lining, and toxin buildup, resulting in a toxic local environment. Ho CJ et al.’s study confirmed that native kidney hydronephrosis is a remarkably strong independent predictor for post-KT UTUC, with an Odds Ratio (OR) of 35.32 (95% CI, 17.99–69.36; p < 0.001) (19). Among 67 KTRs with UTUC, the incidence of hydronephrosis was 68.7%, significantly higher than the 4.8% in those without UTUC (19). Ho, C.J. et al. discovered that patients with new-onset hydronephrosis post KT had a higher likelihood of developing UC, particularly UBUC. Notably, synchronous UTUC was observed significantly more often in the NKH group (65.2% vs. 21.1%; p = 0.004), which reflects the highly aggressive and multifocal pan-urothelial field change in this patient population. This synergy further underscores the clinical significance of NKH as a key radiological marker for UC screening (48). Thus, diligent monitoring and prompt intervention are crucial for these patients.

Cigarette smoking

UC is also associated with smoking. In the general population, smoking is one of the primary risk factors for bladder cancer, with approximately 50% of bladder cancer cases linked to smoking (49). Harmful substances from smoking, like aromatic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, enter the bloodstream, reach the bladder, and can cause DNA mutations, leading to cancer. In KTRs, smoking significantly affects bladder cancer risk. Liu S et al. found smoking to be an independent risk factor for bladder cancer post KT. Their analysis showed that smoking raises bladder cancer risk 6.1 times in patients with polyomavirus, while polyomavirus replication in smokers increases the risk 9.7 times, indicating a potential synergistic effect (50).

Other factors

Besides, risk factors such as exposure to arsenic fumes, analgesic abuse, and chronic inflammatory status in KTRs contribute to the predominance of UTUC among female patients (51–53). Uremia per se have been reported to be predisposing factors for invasive bladder cancer in RTRs (54). Studies have indicated that using anthranoids and chemical laxatives for a year is significantly linked to UTUC risk in RTRs (55). An Egyptian report found that 0.4% of 1865 kidney transplant patients had bladder cancer, often linked to prior schistosomiasis infection (56). Genitourinary system diseases, such as reflux or obstructive uropathy, as well as congenital anomalies (accounting for approximately 40%), are also closely related to the occurrence of UC in RTRs (57).

Diagnosis strategies

Imaging examination

Ultrasound is a convenient and reproducible method for detecting kidney and ureter abnormalities, including hydronephrosis and ureteral masses, and is useful for initial UC screening in KTRs (58). Notably, given that Native Kidney Hydronephrosis (NKH) has been validated as an extremely strong independent predictor of post-KT UTUC (19), ultrasound is not only suitable for initial UC screening but also serves as the most effective non-invasive, high-yield method for periodic NKH monitoring in KTRs. This allows for timely identification of NKH, a key radiological marker that signals an elevated risk of UC development. Computed Tomography (CT) offers a clear view of a tumor’s location, size, shape, and relation to nearby tissues, aiding in staging and treatment planning, especially for KTRs suspected of UC. They can confirm lymph node metastasis (59). Retrograde pyelography can detect filling defects in the renal pelvis and ureter, useful for diagnosing UTUC. Each imaging method has its pros and cons, so combining multiple techniques is common in clinical practice to enhance diagnostic accuracy.

Cystoscopy and biopsy

Cystoscopy is essential for diagnosing bladder cancer by allowing direct bladder lesion visualization and tissue sampling for biopsy. Ureteroscopy with biopsy is used for diagnosing tumors in the renal pelvis and ureter. RTRs with AAN history should have regular cystoscopies (60). However, atrophy and upper urinary tract strictures complicate UTUC diagnosis, often making lesion access and biopsy difficult.

Urinalysis

Urinalysis can identify hematuria, but its occurrence is much lower in the KT group compared to the non-KT group. Relying solely on hematuria for screening may delay diagnosis, so it is recommended to combine it with imaging methods like ultrasound and CT for early detection of UTUC post KT (16). Although urinalysis can detect cancer cells, its sensitivity is low, especially due to reduced urine volume from ESRD, which limits detection mainly to bladder lesions. The presence of decoy cells and highly atypical cells in urine suggests potential malignancy, warranting further confirmation through immunohistochemistry, such as SV40. Odetola, O.E., et al. found that 17 of 36 cases had urine cytology tests, with 11 positive results and 5 showing both decoy and malignant cells (61). The effectiveness of urine cytology for detecting UTUC is debated (19), but washed urine cytology is crucial in standard UTUC examinations. Bilateral upper tract washing cytology is particularly useful for excluding high-grade UTUC in patients with repeated uncertain urine cytology and negative cystoscopy results (62).

Management of UC in KTRs

Surgical treatment is the standard for UC in KTRs, but long-term immunosuppression reduces their surgical tolerance, impairs wound healing, and increases infection risk, potentially worsening organ damage. Surgery can also trigger harmful inflammatory responses. There are no universal guidelines for post-transplant UC management, so treatment should be individualized based on tumor characteristics.

Surgical treatment of UTUC

Advanced, multifocal, or bilateral UTUC lesions have a poor prognosis, with radical nephroureterectomy (RNU) and excision of cuff of bladder as standard treatments in KTRs (63). Both open nephroureterectomy and laparoscopic nephroureterectomy (LNUT) have similar operative times, but the laparoscopic approach results in less blood loss, shorter hospital stays, and better oncological outcomes (64). However, the use of LNUT in KTRs with UTUC is limited, and there is no consensus on whether open or laparoscopic surgery should be used for patients with UTUC post KT. Wu JT et al. performed LNUT on 11 patients with in situ UTUC post KT, reporting no intraoperative complications, an average hospital stay of 6.7 days, stable renal function, and minimal disease progression. They concluded that LNUT is safe and effective, offering benefits like minimal trauma, quick recovery, and acceptable oncological outcomes. LNUT can be executed through either a retroperitoneal or transperitoneal method. The retroperitoneal laparoscopic technique efficiently reveals the renal pedicle, necessitating less dissection and minimizing the risk of injury to intraperitoneal organs. The primary drawback of this method is the restricted working area due to the heightened risk of harming the nearby transplanted kidney (65). Wu JT et al. noted that the laparoscopic method offers great access to the kidney and renal hilum and can be easily switched to open distal ureterectomy to protect the transplanted kidney from damage due to severe adhesions from distal ureteral cancer. They also routinely use this approach for lymph node removal (66). While LNUT offers several benefits, its use in treating UTUC in KTRs is challenging, particularly when the primary tumor and transplanted kidney are on the same side, as limited space heightens the risk of damaging the transplant (65, 66). Chang NW et al. note that despite the challenges of open surgery for KTRs, including scar tissue around the graft, and difficult ureteral dissection in laparoscopic procedures, in their team, the proportion of open surgery was higher in the KT group than in the non-KT group (67). Despite limited randomized trials, numerous case reports suggest that transplant recipients gain from laparoscopic surgery, experiencing less pain, shorter hospital stays, quicker recovery, and fewer wound complications (68). The key concern is the long-term outcomes of LNUT for these patients, but studies are scarce. Long-term follow-up is essential to evaluate LNUT’s effectiveness in treating UTUC in KTRs.

There is ongoing debate about performing prophylactic contralateral RNU for KTRs with unilateral UTUC, as studies indicate KTRs have a high risk of developing synchronous bilateral UC (17, 51). Furthermore, recurrence on the opposite side after a unilateral radical nephroureterectomy (URNU) is common. According to Fang et al, patients who underwent transplantation had a more than 15 times higher risk of developing tumors on the opposite side compared to those who did not undergo transplantation, with 60% of post-renal transplant patients developing contralateral tumors (69). The study by Huang et al. found that among patients who had renal transplants or were on regular dialysis, the contralateral recurrence rate over five years was 38.3%, with every recurrence occurring within the first three years (70). Therefor, they recommend simultaneous bilateral radical nephroureterectomy (SBRNU) once one side is diagnosed (69, 70). Zhang Q et al. studied the effectiveness of SBRNU versus URNU in treating newly diagnosed UTUC post KT, involving 48 patients (21 SBRNU, 27 URNU). SBRNU resulted in longer surgeries and hospital stays, but similar blood loss and perioperative complications compared to URNU. At a 65-month follow-up, SBRNU showed better progression free survival (PFS) and cancer specific survival (CSS). The author suggests that SBRNU can enhance survival rates without impacting perioperative outcomes. It may be a suitable treatment for high-risk patients, particularly females with prolonged AA exposure, prone to bilateral UTUC post KT (71). Lin KJ et al. studied 44 cases of KTRs with UTUC, finding that PFS was significantly better in the SBRNU group than in the URNU group (72). Kao YL et al. observed that 41% of UTUC cases post KT were synchronous and recommended prophylactic SBRNU due to high contralateral recurrence rates and lack of early screening methods. However, given the 0.2%–2.63% incidence of UTUC post KT, they advised against routine prophylactic SBRNU for all patients, suggesting instead close postoperative monitoring. SBRNU with bladder cuff resection is strongly recommended if UTUC is suspected or if there is high risk, while considering patient preferences (51). While this method reduces the risk of postoperative urinary tract infections and upper urinary tract tumor recurrence, it may raise the risk of other complications due to reduced residual urinary tract (56). Lang, H et al. performed systemic SBRNU on four patients but did not find any tumors (73). Therefore, some authors suggest that SBRNU heightens health risks for KTRs, recommending URNU first, with subsequent careful monitoring and evaluation (66). In summary, treatment for KTRs with unilateral UTUC should be personalized. The benefits of prophylactic SBRNU are uncertain, so it shouldn’t be standard practice. It’s important to weigh the risk of postoperative infections or tumor recurrence in the upper urinary tract against the advantages of maintaining some urinary function. For patients with AAN at high risk of synchronous UTUC, decisions should be made after thoroughly evaluating renal function, tumor traits, and surgical tolerance.

Surgical treatment of UBUC

Muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) occurs in 37% of KTRs, a higher rate than in the general population, with most cases diagnosed at advanced stages (74, 75). Treating bladder cancer in KTRs is complex due to the need to balance effective cancer treatment with maintaining kidney function and proper urinary drainage. Due to the aggressive nature of UC in KTRs, a conservative endoscopic approach should not be applied to the KT population. While transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) appears reasonably safe for low-risk diseases in the general population (76). MIBC is generally more aggressive than non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), with a higher progression rate, poorer prognosis, and lower survival rate (77). Therefore, early radical cystectomy (RC) and pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) are widely recommended (78). Comparative data from a series of cystectomies indicate that extended lymph node dissection improves overall survival (79), though some researchers prefer to avoid it on the transplant side to prevent blood supply damage. If needed, the opposite side’s dissection can be extended (77). When a cystectomy is needed in patients who have undergone a kidney transplant, the choice of urinary diversion must be evaluated and adjusted according to the renal transplant’s performance. Reconstruction options vary from basic cutaneous ureterostomy to an orthotopic neobladder, with the latter advised only for patients whose glomerular filtration rate is stable at 50 ml or higher. In the past, ileal conduits or Kock pouches were used for renal transplant recipients needing cystectomy, despite the high risk of renal infection and graft deterioration in immunosuppressed patients (77). Additionally, urinary diversion during cystectomy is crucial, with the studer in situ bladder procedure being a popular choice after RC. This technique uses an ileum segment to create a urinary reservoir, connecting the ureter to the urethra, allowing patients to regain near-normal urinary function. It’s suitable for those with MIBC or high-risk NMIBC, requiring careful evaluation of intestinal function and urethral sphincter status. Successful cases include KTRs undergoing this procedure. Manassero F et al. assert that the studer technique is effective for urinary tract reconstruction in bladder cancer patients post KT due to its adaptability to short ureters and its ability to prevent reflux (77, 80). However, when selecting a urinary diversion method, consider patient comfort and complication risks. While orthotopic neobladder is more physiologically suitable, it can heighten urinary tract infection risk from intermittent catheterization and cause metabolic issues due to urine absorption by the intestines. Yavuzsan AH et al. conducted a RC with ileal conduit diversion on a young female with invasive bladder cancer, featuring sarcomatoid and squamous cell variants, three years post KT. The procedure was likely chosen for its simplicity and lower complication risk, crucial for preserving the transplanted kidney and the patient’s overall health (81). In complex cases with both upper and lower urinary tract lesions, advanced surgeries like laparoscopic bilateral nephroureterectomy with PLND and orthotopic neobladder may be necessary (82).

Adjuvant therapy

UC is often multifocal, and adjuvant chemotherapy is crucial for advanced or high-risk cases. Adjuvant chemotherapy plays a significant role in the comprehensive treatment of UC post KT. However, immunosuppressed patients may poorly tolerate chemotherapy and face more complications, requiring careful patient selection. While platinum-based chemotherapy is the primary treatment for advanced UC, its nephrotoxicity limits its use in KTRs (83). Chang NW et al. analyzed 57 patients with advanced UTUC (stage T2 or higher) who underwent nephroureterectomy and bladder cuff excision, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus cisplatin or carboplatin. The study included 23 KTRs and 34 non-transplant patients. Results indicated the five-year disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were 45.7% vs. 70.2% and 62.8% vs. 77.6%, for the KT and non-KT groups. Hematologic toxicities showed significant differences between the KT and non-KT group. The KT group had more severe neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia compared to the non-KT group. In contrast, non-hematologic toxicities, including nausea/vomiting, nephrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and skin rash, did not differ statistically between the two groups. Notably, only 3 patients in the KT group and 2 in the non-KT group developed >grade 2 nephrotoxicity, which was reversible after treatment, indicating mild and acceptable impacts of chemotherapy on graft kidney function; additionally, recombinant human granulocyte colony stimulating factor was used to manage high-grade hematologic toxicities, though nearly half of KT patients and one-third of non-KT patients still required chemotherapy dose reductions. These findings are valuable for clinical treatment guidance (67). Additionally, Zhang, P., et al. found that gemcitabine and cisplatin (GC) chemotherapy was somewhat effective for locally advanced disease. In seven KTRs with advanced UC, pre- and postoperative GC treatment resulted in one complete response, two partial responses, and four stable cases, with a 43% overall efficacy rate. Myelosuppression was the primary toxicity and side effect linked to the GC regimen. Other adverse reactions included reversible nephrotoxicity, gastrointestinal and cutaneous manifestations, and phlebitis. Hematologic toxicities, meanwhile, encompassed reversible leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia (84). Wang, Z.P. et al. studied 22 patients with advanced UC post KT. Eleven received surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy (GC regimen), and the other eleven had surgery only. The group receiving adjuvant chemotherapy showed significantly better survival. KTRs with advanced UC who received surgery plus adjuvant GC chemotherapy had significantly better OS than those who only underwent surgery, with the median OS extended by 17 months. Hematologic toxicities occurred at a relatively high incidence, leading to dose reduction of chemotherapeutic agents in 45.5% of patients. Among nonhematologic toxicities, gastrointestinal reactions were the most prevalent. Grade 1 nephrotoxicity was documented in 3 patients, with no cases of higher-grade nephrotoxicity observed. Notably, serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels did not show significant changes during chemotherapy. Of these eleven patients, seven had UTUC (85). These data confirm that platinum-based AC significantly improves disease control and survival in KTRs with advanced UC. While Wang, Z.P. et al. confirmed the safety of platinum-based chemotherapy for KTRs, its long-term effects on patients with ≥T2 disease are uncertain. Du et al. reported no significant impact of this chemotherapy on the prognosis of such patients. Furthermore, the effectiveness of the GC or Gemcitabine and Carboplatin (GCa) regimen in preventing distant metastasis in these recipients remains unproven (83).

Bladder instillation chemotherapy effectively reduces NMIBC recurrence. Despite lacking evidence for benefits in KTRs, immediate postoperative instillation is advised due to high recurrence risk (78). Elkentaoui H et al. conducted TURBT on NMIBC patients post KT, followed by at least one mitomycin C instillation, observing no mitomycin C-related complications. Neuzillet et al. concluded that mitomycin C is safe for KTRs and may be beneficial without added risk (86, 87). For patients with tumor recurrence after intravesical mitomycin C therapy, intravesical gemcitabine may be an option. Although typically given intravenously for metastatic bladder cancer, studies indicate that a 1000 mg intravesical dose can help prevent recurrence in high-grade NMIBC patients unresponsive to BCG therapy (88). BCG is an effective treatment for high-risk NMIBC, typically requiring at least a year of maintenance to lower recurrence and progression rates (54). However, its use in KTRs is debated due to safety concerns in immunosuppressed patients. First, the effectiveness of BCG depends on the patient’s immune response, and it may be less effective in those with weakened immunity. However, studies have shown that BCG bladder instillation chemotherapy is both safe and effective (89, 90). Second, due to the patient’s impaired immune response, BCG may spread systemically, leading to significant side effects. There have been case reports of systemic infection following bladder instillation of BCG (91). Currently, only a limited number of medical centers have experience with BCG in KTRs, and even fewer have enough patients to create guidelines. Future research should focus on optimizing BCG treatment for KTRs (92).

Neoadjuvant or adjuvant immunotherapy currently improves survival in advanced UC, especially for patients ineligible for cisplatin with few other options (93). Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which enhance the immune response against tumors by blocking PD-1/PD-L1 pathways, have proven effective and safe in treating platinum-resistant metastatic UC. Various ICIs have demonstrated efficacy and safety comparable to chemotherapy, and pembrolizumab outperformed chemotherapy in a phase III trial (94). However, immunotherapy for UC in KTRs may still be a double-edged sword, as it may trigger T cells to attack both tumor and donor antigens. Research indicates that PD-1 can lead to kidney transplant rejection in some cases and often accelerates tumor growth (95). Some KTRs have effectively managed metastatic UC with anti-PD-1 monotherapy. In this instance, the patient showed partial tumor regression without any transplant rejection during the treatment (96). Wu CK et al. reported on a kidney transplant patient with metastatic UC treated with pembrolizumab, bevacizumab, cisplatin and gemcitabine with a continued immunosuppressants (mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus), leading to notable tumor reduction and stable graft function (97). Therefore, ICIs can potentially manage cancer without causing rejection. However, using ICIs in KTRs demands careful balancing of immune activation and rejection risk. As an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC), Enfortumab ventodin (EV) specifically targets the Nectin-4 protein. This protein is highly expressed in UC and has demonstrated significant efficacy in patients who have failed platinum-based chemotherapy and ICIs therapy (98). Studies have shown that EV is also well-tolerated in patients with renal impairment (99), which is particularly important for kidney transplant recipients. However, the safety and efficacy of EV in kidney transplant patients require further investigation. New treatments, like ADCs and ICIs combination therapies, are being studied and may improve patient outcomes (100). Fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitors, such as erdafitinib, have shown some success in treating UC, but more experience is needed for use in post-KT patients.

Adjustment of immunosuppressants

When a kidney transplant recipient is diagnosed with urothelial carcinoma, it’s crucial to reduce or adjust immunosuppressive drugs to boost immune surveillance. This adjustment is necessary, especially when using ICIs, to balance tumor treatment and prevent transplant rejection (59). Close monitoring of kidney function is essential to avoid rejection, making the careful adjustment of the immunosuppressive regimen a key part of treatment.

Tacrolimus, a CNI drug, has advanced transplantation with strong short-term outcomes, but its chronic nephrotoxicity poses a challenge (101). Similarly, cyclosporine, another CNI drug, can lead to malignant tumors (102). Conversely, mTOR inhibitors may lower the risk of cancers like non-melanoma skin cancer and Kaposi’s sarcoma (103). For KTRs with newly diagnosed UC, mTOR inhibitors are typically favored over CNI drugs. Some experts recommend minimizing CNI use in immunosuppressive regimens for those at high risk of tumor development (9). Combining CNI and mTOR inhibitors allows for lower CNI doses, minimizing adverse reactions without compromising transplant outcomes; rejection rates remain similar to standard doses, while renal function improves.

Hu XP et al. assessed the safety and effectiveness of combining rapamycin (RPM) with low-dose CNI in 15 KTRs with UC. The regimen replaced mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or azathioprine (Aza) with RPM, adjusting doses to maintain 4–6 μg/L blood levels, and reduced CNI doses to one-third after stabilization. All patients received surgical treatment and intravesical chemotherapy. Over two years, 9 patients had no tumor recurrence, 2 had two recurrences, and 4 had one. No acute rejection occurred, with hyperlipidemia and thrombocytopenia as common side effects. This approach appears to inhibit tumor growth, enhance graft function, and reduce cyclosporine nephrotoxicity, showing promising safety and efficacy (104). Combining mTOR inhibitors with tacrolimus regimens lowers the risk of UC post KT (105). However, Besarani et al. found that altering or stopping immunosuppressive therapy alongside chemotherapy offers limited benefits for patients with metastatic disease post KT (106).

In summary, adjusting immunosuppression regimens for post-KT patients with urothelial carcinoma requires careful monitoring of tumor recurrence, kidney function, and adverse reactions. Treatment should be personalized based on tumor status, incorporating surgical resection and local infusion chemotherapy to improve efficacy and quality of life. This complex process necessitates further clinical research to optimize outcomes. As shown in Table 2.

Prognosis and screening

The prognosis for UC post KT is poor, with high recurrence and mortality rates. A propensity-matched study showed that ESRD patients who received a kidney transplant had worse cancer outcomes for UTUC than those who did not (107). The prognosis of UC post KT is significantly affected by factors such as tumor staging, particularly stages ≥ T2 and positive lymph nodes (N+), which are independent risk factors for cancer-specific mortality. In a study of 106 patients with newly diagnosed UTUC post KT, cancer-specific survival rates were 89.2% at 1 year, 73.2% at 5 years, and 61.6% at 10 years (108). In addition, patient-specific factors, like hydronephrosis in the affected kidney and female gender, significantly influence UTUC prognosis (19). UC linked to polyomavirus infection often occurs earlier, affecting outcomes. Treatment choices also impact prognosis; radical surgery can improve tumor control but may not be suitable for all patients due to their health conditions (29).

Monitoring for recurrence and long-term follow-up are crucial in managing UC post KT. Close attention to changes in patient symptoms is essential. Even though hematuria might be atypical in KTRs, any occurrence of hematuria or flank pain should raise suspicion for tumor recurrence. In addition, regular physical exams, lab tests, and imaging can promptly identify tumor recurrence. Urine cytology is useful for monitoring urothelial carcinoma. In a study of patients with UC post KT, the test showed 82% sensitivity and 97% specificity for detecting recurrence (109). Regular ultrasounds can identify abnormalities in the kidneys, ureters, and bladder. Given the quantified predictive value of NKH for UC, we specifically recommend periodic ultrasound monitoring of the native kidneys every 6–12 months to detect NKH promptly. Once NKH is identified via ultrasound, proactive and comprehensive screening of the entire native urinary tract is imperative. Post-surgery CT urography is useful for detecting recurrent tumors in the upper urinary tract and bladder in UTUC patients. Additionally, routine cystoscopy is crucial for monitoring bladder tumor recurrence. Follow-up schedules should be personalized based on the patient’s condition, with more frequent visits soon after surgery and gradually extended intervals. High-risk patients, like those with advanced tumors or multiple infections, require more intensive follow-ups. Utilizing various monitoring methods aids in early detection of tumor recurrence, ensuring timely treatment. Collaboration among a multidisciplinary team for tailored treatment and vigilant follow-up enhances patient outcomes.

Conclusion

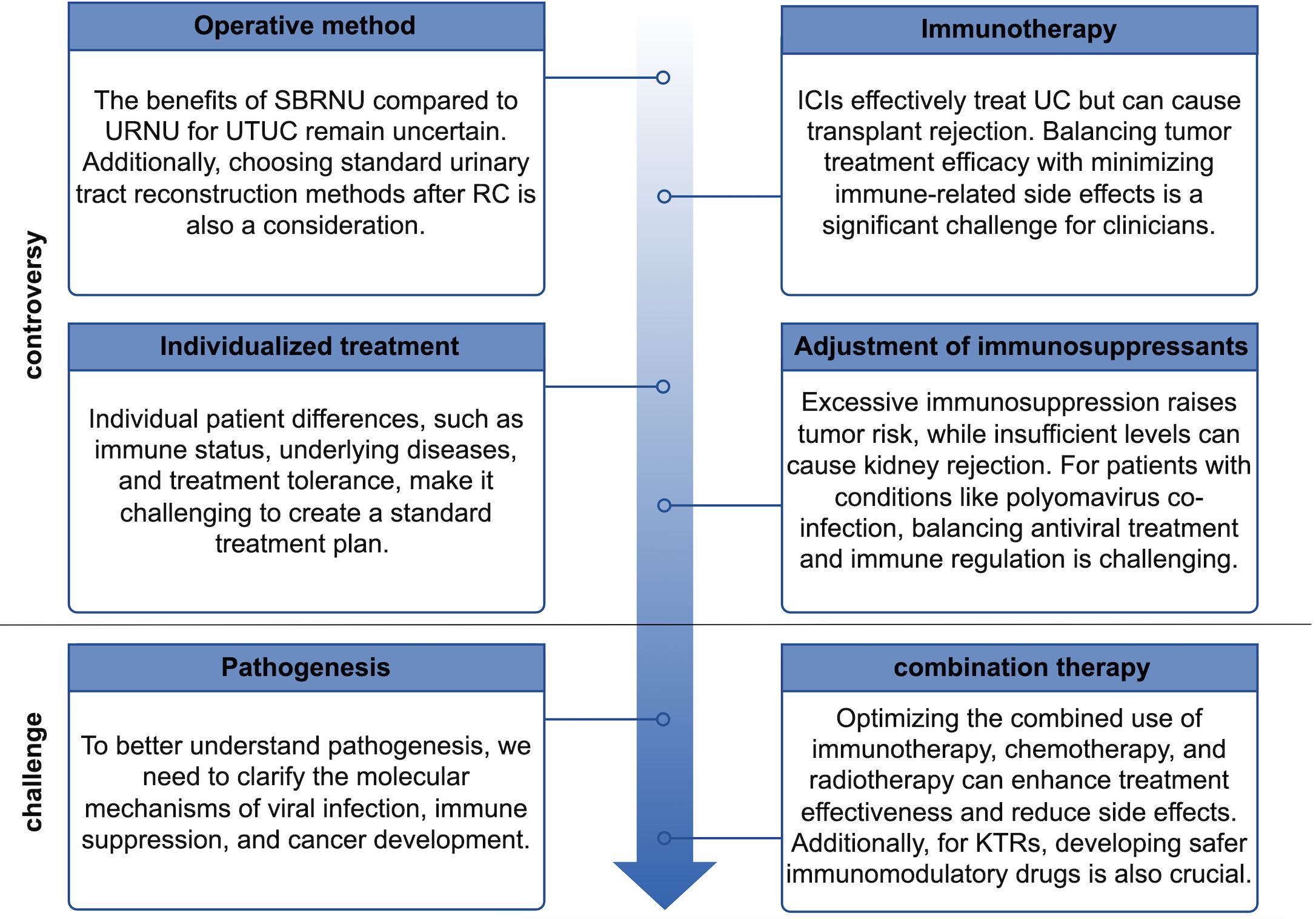

The incidence of UC post KT is markedly elevated compared to that in the general population. Within this cohort, female patients with a history of AAN constitute a high-risk group for the development of UC post KT and should be prioritized for screening. During clinical evaluations, particular attention should be directed towards the patient’s native urinary tract. Periodic ultrasound monitoring of native kidney hydronephrosis should be integrated as a core component of post-KT screening protocols, it is recommended that screening commence as soon as possible following KT. Early detection, timely intervention, and regular follow-up are essential for optimizing patient outcomes. While managing the tumor, it is imperative to preserve renal function to the greatest extent possible, thereby enhancing the quality of life and prognosis for patients with UC post KT. Future research should focus on addressing current gaps in the literature. Specifically, prospective multicenter trials are needed to explore in depth the interactions between immunosuppression, UC progression, and emerging therapies in kidney transplant recipients, thereby providing a basis for developing standardized clinical management guidelines. Figure 3 summarizes the controversies and challenges faced by KTRs.

Figure 3. Controversies and challenges faced by kidney transplant recipients with urothelial carcinoma.

Author contributions

LL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. FR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. ZL: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. XT: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. GW: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. LM: Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Glossary

KT: Kidney transplantation

ESRD: End-stage renal disease

KTRs: Kidney transplant recipients

UC: Urothelial carcinoma

UBUC: Urinary bladder urothelial carcinoma

UTUC: Upper tract urothelial carcinoma

UTI: Urinary tract infection

BKPyV: BK polyomavirus

AA: Aristolochic acid

AAN: Aristolochic acid nephropathy

CNI: Calcineurin inhibitor

mTOR: Mammalian target of rapamycin

DFS: Disease-free survival

HPyV: Human polyomavirus

BKPV: BK polyomavirus

LTAg: Large T antigen

NCCR: Non-coding control region

MMEJ: Microhomology end joining

NHEJ: Nonhomologous end joining

JCV: John Cunningham virus

NKH: Native kidney hydronephrosis

CT: Computed tomography

RNU: Radical nephroureterectomy

LNUT: Laparoscopic nephroureterectomy

URNU: Unilateral radical nephroureterectomy

SBRNU: Simultaneous bilateral radical nephroureterectomy

PFS: Progression-free survival

CSS: Cancer-specific survival

MIBC: Muscle-invasive bladder cancer

NMIBC: Non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer

TURBT: Transurethral resection of bladder tumor

RC: Radical cystectomy

PLND: Pelvic lymph node dissection

OS: Overall survival

GC: Gemcitabine + Cisplatin

GCa: Gemcitabine + Carboplatin

BCG: Bacillus Calmette-Guérin

ICIs: Immune checkpoint inhibitors

ADCs: Antibody–drug conjugates

EV: Enfortumab ventodin

FGFR: Fibroblast growth factor receptor

RPM: Rapamycin

MMF: Mycophenolate mofetil

Aza: Azathioprine

References

1. Morath C, Mueller M, Goldschmidt H, Schwenger V, Opelz G, and Zeier M. Malignancy in renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2004) 15:1582–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000126194.77004.9B

2. Al-Adra D, Al-Qaoud T, Fowler K, and Wong G. De novo Malignancies after kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2022) 17:434–43. doi: 10.2215/CJN.14570920

3. Sprangers B, Nair V, Launay-Vacher V, Riella LV, and Jhaveri KD. Risk factors associated with post-kidney transplant Malignancies: an article from the Cancer-Kidney International Network. Clin Kidney J. (2018) 11:315–29. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfx122

4. Hickman LA, Sawinski D, Guzzo T, and Locke JE. Urologic Malignancies in kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. (2018) 18:13–22. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14533

5. Krynitz B, Edgren G, Lindelöf B, Baecklund E, Brattström C, Wilczek H, et al. Risk of skin cancer and other Malignancies in kidney, liver, heart and lung transplant recipients 1970 to 2008–a Swedish population-based study. Int J Cancer. (2013) 132:1429–38. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27765

6. Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Fraumeni JF Jr, Kasiske BL, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, et al. Spectrum of cancer risk among US solid organ transplant recipients. JAMA. (2011) 306:1891–901. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1592

7. Yan L, Salama ME, Lanciault C, Matsumura L, and Troxell ML. Polyomavirus large T antigen is prevalent in urothelial carcinoma post-kidney transplant. Hum Pathol. (2016) 48:122–31. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.09.021

8. Rossetto A, Tulissi P, De Marchi F, Gropuzzo M, Vallone C, Adani GL, et al. De novo solid tumors after kidney transplantation: is it time for a patient-tailored risk assessment? Experience from a single center. Transplant Proc. (2015) 47:2116–20. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.01.029

9. Yu J, Lee CU, Kang M, Jeon HG, Jeong BC, Seo SI, et al. Incidences and oncological outcomes of urothelial carcinoma in kidney transplant recipients. Cancer Manag Res. (2019) 11:157–66. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S185796

10. Cox J and Colli JL. Urothelial cancers after renal transplantation. Int Urol Nephrol. (2011) 43:681–6. doi: 10.1007/s11255-011-9907-z

11. Li XB, Xing NZ, Wang Y, Hu XP, Yin H, and Zhang XD. Transitional cell carcinoma in renal transplant recipients: a single center experience. Int J Urol. (2008) 15:53–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01932.x

12. Chiang YJ, Yang PS, Wang HH, Lin KJ, Liu KL, Chu SH, et al. Urothelial cancer after renal transplantation: an update. Transplant Proc. (2012) 44:744–5. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.12.073

13. Zhang A, Shang D, Zhang J, Zhang L, Shi R, Fu F, et al. A retrospective review of patients with urothelial cancer in 3,370 recipients after renal transplantation: a single-center experience. World J Urol. (2015) 33:713–7. doi: 10.1007/s00345-014-1412-4

14. Vervloessem I, Oyen R, Vanrenterghem Y, Van Poppel H, Van Hover P, Debakker G, et al. Transitional cell carcinoma in a renal allograft. Eur Radiol. (1998) 8:936–8. doi: 10.1007/s003300050491

15. Ardelt PU, Rieken M, Ebbing J, Bonkat G, Vlajnic T, Bubendorf L, et al. Urothelial cancer in renal transplant recipients: incidence, risk factors, and oncological outcome. Urology. (2016) 88:104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.10.031

16. Lin SH, Luo HL, Chen YT, and Cheng YT. Using hematuria as detection of post-kidney transplantation upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma is associated with delayed diagnosis of cancer occurrence. Transplant Proc. (2017) 49:1061–3. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.03.070

17. Wu MJ, Lian JD, Yang CR, Cheng CH, Chen CH, Lee WC, et al. High cumulative incidence of urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma after kidney transplantation in Taiwan. Am J Kidney Dis. (2004) 43:1091–7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.03.016

18. Tsai HL, Chang JW, Wu TH, King KL, Yang LY, Chan YJ, et al. Outcomes of kidney transplant tourism and risk factors for de novo urothelial carcinoma. Transplantation. (2014) 98:79–87. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000023

19. Ho CJ, Huang YH, Hsieh TY, Yang MH, Wang SC, Chen WJ, et al. Native kidney hydronephrosis is associated with upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma in post-kidney transplantation patients. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:4474. doi: 10.3390/jcm10194474

20. Lughezzani G, Sun M, Perrotte P, Shariat SF, Jeldres C, Budäus L, et al. Gender-related differences in patients with stage I to III upper tract urothelial carcinoma: results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Urology. (2010) 75:321–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.09.048

21. Zivcić-Cosić S, Grzetić M, Valencić M, Oguić R, Maricić A, Dordević G, et al. Urothelial cancer in patients with Endemic Balkan Nephropathy (EN) after renal transplantation. Ren Fail. (2007) 29:861–5. doi: 10.1080/08860220701595882

22. Cannon E, Ntala C, Joss N, Rahilly M, Metcalfe W, O'Donnell M, et al. High grade urothelial carcinoma in kidney transplant patients with a history of BK viremia - Just a coincidence? Clin Transplant. (2023) 37:e15113. doi: 10.1111/ctr.15113

23. Liu GM, Fang Q, Ma HS, Sun G, and Wang XC. Distinguishing characteristics of urothelial carcinoma in kidney transplant recipients between China and Western countries. Transplant Proc. (2013) 45:2197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.10.035

24. Colin P, Koenig P, Ouzzane A, Berthon N, Villers A, Biserte J, et al. Environmental factors involved in carcinogenesis of urothelial cell carcinomas of the upper urinary tract. BJU Int. (2009) 104:1436–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08838.x

25. Nortier JL, Martinez MC, Schmeiser HH, Arlt VM, Bieler CA, Petein M, et al. Urothelial carcinoma associated with the use of a Chinese herb (Aristolochia fangchi). N Engl J Med. (2000) 342:1686–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006083422301

26. Xiao J, Zhu X, Hao GY, Zhu YC, Ma LL, Zhang YH, et al. Association between urothelial carcinoma after renal transplantation and infection by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18. Transplant Proc. (2011) 43:1638–40. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.03.053

27. Wu CF, Chang PL, Chen CS, Chuang CK, Weng HH, and Pang ST. The outcome of patients on dialysis with upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. J Urol. (2006) 176:477–81. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.099

28. Li D, Liu F, Chen Y, Li P, Liu Y, and Pang Y. Ipsilateral synchronous papillary renal neoplasm with reverse polarity and urothelial carcinoma in a renal transplant recipient: a rare case report with molecular analysis and literature review. Diagn Pathol. (2023) 18:120. doi: 10.1186/s13000-023-01405-w

29. Huang GL, Luo HL, Chen YT, and Cheng YT. Oncologic outcomes of post-kidney transplantation superficial urothelial carcinoma. Transplant Proc. (2018) 50:998–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.01.031

30. Rogers A, Ng JK, Glendinning J, and Rix D. The management of transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) in a European regional renal transplant population. BJU Int. (2012) 110:E34–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10777.x

31. Wang LJ, Wong YC, and Huang CC. Urothelial carcinoma of the native ureter in a kidney transplant recipient. J Urol. (2010) 184:728. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.04.049

32. Roumeguère T, Broeders N, Jayaswal A, Rorive S, Quackels T, Pozdzik A, et al. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy in non-muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma after renal transplantation for end-stage aristolochic acid nephropathy. Transpl Int. (2015) 28:199–205. doi: 10.1111/tri.12484

33. Miao XH, Wang CG, Hu BQ, Li A, Chen CB, and Song WQ. TGF-beta1 immunohistochemistry and promoter methylation in chronic renal failure rats treated with Uremic Clearance Granules. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. (2010) 48:284–91. doi: 10.2478/v10042-010-0001-7

34. Vajdic CM, McDonald SP, McCredie MR, van Leeuwen MT, Stewart JH, Law M, et al. Cancer incidence before and after kidney transplantation. JAMA. (2006) 296:2823–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.23.2823

35. Michel Ortega RM, Wolff DJ, Schandl CA, and Drabkin HA. Urothelial carcinoma of donor origin in a kidney transplant patient. J Immunother Cancer. (2016) 4:63. doi: 10.1186/s40425-016-0167-4

36. Melchior S, Franzaring L, Shardan A, Schwenke C, Plümpe A, Schnell R, et al. Urological de novo Malignancy after kidney transplantation: a case for the urologist. J Urol. (2011) 185:428–32. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.091

37. Lai HY, Wu LC, Kong PH, Tsai HH, Chen YT, Cheng YT, et al. High level of aristolochic acid detected with a unique genomic landscape predicts early UTUC onset after renal transplantation in Taiwan. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:828314. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.828314

38. Hejlesen MB, Youssef MH, Bech JN, and Mose FH. Urothelial carcinoma in an allograft kidney. Case Rep Nephrol Dial. (2022) 12:85–9. doi: 10.1159/000524901

39. Kotton CN and Fishman JA. Viral infection in the renal transplant recipient. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2005) 16:1758–74. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121113

40. Hirsch HH, Knowles W, Dickenmann M, Passweg J, Klimkait T, Mihatsch MJ, et al. Prospective study of polyomavirus type BK replication and nephropathy in renal-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. (2002) 347:488–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020439

41. Fioriti D, Videtta M, Mischitelli M, Degener AM, Russo G, Giordano A, et al. The human polyomavirus BK: Potential role in cancer. J Cell Physiol. (2005) 204:402–6. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20300

42. Jones H, Bhakta A, Jia L, Wojciechowski D, and Torrealba J. An unusual presentation of metastatic BK virus-associated urothelial carcinoma arising in the allograft, persisting after transplant nephrectomy. Int J Surg Pathol. (2023) 31:1586–92. doi: 10.1177/10668969231160258

43. Chu YH, Zhong W, Rehrauer W, Pavelec DM, Ong IM, Arjang D, et al. Clinicopathologic characterization of post-renal transplantation BK polyomavirus-associated urothelial carcinomaSingle institutional experience. Am J Clin Pathol. (2020) 153:303–14. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqz167

44. Kenan DJ, Mieczkowski PA, Burger-Calderon R, Singh HK, and Nickeleit V. The oncogenic potential of BK-polyomavirus is linked to viral integration into the human genome. J Pathol. (2015) 237:379–89. doi: 10.1002/path.4584

45. Jin Y, Zhou Y, Deng W, Wang Y, Lee RJ, Liu Y, et al. Genome-wide profiling of BK polyomavirus integration in bladder cancer of kidney transplant recipients reveals mechanisms of the integration at the nucleotide level. Oncogene. (2021) 40:46–54. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-01502-w

46. Querido S, Fernandes I, Weigert A, Casimiro S, Albuquerque C, Ramos S, et al. High-grade urothelial carcinoma in a kidney transplant recipient after JC virus nephropathy: The first evidence of JC virus as a potential oncovirus in bladder cancer. Am J Transplant. (2020) 20:1188–91. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15663

47. Maisonneuve P, Agodoa L, Gellert R, Stewart JH, Buccianti G, Lowenfels AB, et al. Cancer in patients on dialysis for end-stage renal disease: an international collaborative study. Lancet. (1999) 354:93–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06154-1

48. Ho CJ, Huang YH, Hsieh TY, Yang MH, Wang SC, Chen WJ, et al. New hydronephrosis in the native kidney is associated with the development of de novo urinary bladder urothelial carcinoma in patients with post-kidney transplantation. Healthcare (Basel). (2023) 11:1209. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11091209

49. Crivelli JJ, Xylinas E, Kluth LA, Rieken M, Rink M, and Shariat SF. Effect of smoking on outcomes of urothelial carcinoma: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol. (2014) 65:742–54. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.06.010

50. Liu S, Chaudhry MR, Berrebi AA, Papadimitriou JC, Drachenberg CB, Haririan A, et al. Polyomavirus replication and smoking are independent risk factors for bladder cancer after renal transplantation. Transplantation. (2017) 101:1488–94. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001260

51. Kao YL, Ou YC, Yang CR, Ho HC, Su CK, and Shu KH. Transitional cell carcinoma in renal transplant recipients. World J Surg. (2003) 27:912–6. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-6954-3

52. Tan LB, Chen KT, and Guo HR. Clinical and epidemiological features of patients with genitourinary tract tumour in a blackfoot disease endemic area of Taiwan. BJU Int. (2008) 102:48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07565.x

53. Chen CH, Dickman KG, Moriya M, Zavadil J, Sidorenko VS, Edwards KL, et al. Aristolochic acid-associated urothelial cancer in Taiwan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2012) 109:8241–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119920109

54. Master VA, Meng MV, Grossfeld GD, Koppie TM, Hirose R, and Carroll PR. Treatment and outcome of invasive bladder cancer in patients after renal transplantation. J Urol. (2004) 171:1085–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000110612.42382.0a

55. Pommer W, Bronder E, Klimpel A, Helmert U, Greiser E, and Molzahn M. Urothelial cancer at different tumour sites: role of smoking and habitual intake of analgesics and laxatives. Results of the Berlin Urothelial Cancer Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (1999) 14:2892–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.12.2892

56. Kamal MM, Soliman SM, Shokeir AA, Abol-Enein H, and Ghoneim MA. Bladder carcinoma among live-donor renal transplant recipients: a single-centre experience and a review of the literature. BJU Int. (2008) 101:30–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07210.x

57. Medani S, O'Kelly P, O'Brien KM, Mohan P, Magee C, and Conlon P. Bladder cancer in renal allograft recipients: risk factors and outcomes. Transplant Proc. (2014) 46:3466–73. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.06.075

58. Altinbas NK and Gunertem G. Urothelial carcinoma detected by ultrasonography in a renal transplant recipient. Exp Clin Transplant. (2019) 17:259–62. doi: 10.6002/ect.2018.0286

59. Hikita K, Nishikawa R, Taniguchi S, Mae Y, Iyama T, Takata T, et al. A case of rapidly progressing urothelial carcinoma arising after living donor kidney transplantation treated with chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Yonago Acta Med. (2025) 68:75–8. doi: 10.33160/yam.2025.02.009

60. Lemy A, Wissing KM, Rorive S, Zlotta A, Roumeguerre T, Muniz Martinez MC, et al. Late onset of bladder urothelial carcinoma after kidney transplantation for end-stage aristolochic acid nephropathy: a case series with 15-year follow-up. Am J Kidney Dis. (2008) 51:471–7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.015

61. Odetola OE, Isaila B, Pambuccian SE, and Barkan GA. Unusual BK polyomavirus-associated urologic Malignancies in renal transplant recipients: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. (2018) 46:1050–9. doi: 10.1002/dc.24044

62. Zhang ML, VandenBussche CJ, Hang JF, Miki Y, McIntire PJ, Peyton S, et al. A review of urinary cytology in the setting of upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Am Soc Cytopathol. (2021) 10:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2020.06.011

63. Piana A, López-Abad A, Lanzillotta B, Pecoraro A, Prudhomme T, Haberal HB, et al. Systematic review on upper urinary tract carcinoma in kidney transplant recipients. J Clin Med. (2025) 14:3927. doi: 10.3390/jcm14113927

64. Simone G, Papalia R, Guaglianone S, Ferriero M, Leonardo C, Forastiere E, et al. Laparoscopic versus open nephroureterectomy: perioperative and oncologic outcomes from a randomised prospective study. Eur Urol. (2009) 56:520–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.06.013

65. Ye J, Ma L, Huang Y, Hou X, Xiao C, Zhao L, et al. Retroperitoneal laparoscopic nephroureterectomy with bladder cuff excision for native upper tract transitional cell carcinoma ipsilateral to a transplanted kidney. Urology. (2010) 76:1395–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.022

66. Wu JT, Wan FC, Gao ZL, Wang JM, and Yang DD. Transperitoneal laparoscopic nephroureterectomy for native upper tract urothelial carcinoma in renal transplant recipients. World J Urol. (2013) 31:135–9. doi: 10.1007/s00345-012-0865-6

67. Chang NW, Huang YH, Sung WW, and Chen SL. Adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced upper tract urothelial carcinoma with or without kidney transplantation. J Clin Med. (2024) 13:1831. doi: 10.3390/jcm13071831

69. Fang D, Zhang L, Li X, Xiong G, Chen X, Han W, et al. Risk factors and treatment outcomes of new contralateral upper urinary urothelial carcinoma after nephroureterectomy: the experiences of a large Chinese center. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. (2014) 140:477–85. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1585-7

70. Huang PC, Huang CY, Huang SW, Lai MK, Yu HJ, Chen J, et al. High incidence of and risk factors for metachronous bilateral upper tract urothelial carcinoma in Taiwan. Int J Urol. (2006) 13:864–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01429.x

71. Zhang Q, Ma R, Li Y, Lu M, Zhang H, Qiu M, et al. Bilateral nephroureterectomy versus unilateral nephroureterectomy for treating de novo upper tract urothelial carcinoma after renal transplantation: A comparison of surgical and oncological outcomes. Clin Med Insights Oncol. (2021) 15:11795549211035541. doi: 10.1177/11795549211035541

72. Lin KJ, Chen SY, Chiang YJ, Chu SH, Liu KL, Lin CT, et al. The evolution of upper tract urothelial carcinoma management in kidney recipients. Transplant Proc. (2024) 56:554–6. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2024.01.041

73. Lang H, de Petriconi R, Wenderoth U, Volkmer BG, Hautmann RE, Gschwend JE, et al. Orthotopic ileal neobladder reconstruction in patients with bladder cancer following renal transplantation. J Urol. (2005) 173:881–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000152389.91401.59

74. Ehdaie B, Stukenborg GJ, and Theodorescu D. Renal transplant recipients and patients with end stage renal disease present with more advanced bladder cancer. J Urol. (2009) 182:1482–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.043

75. Shiels MS, Copeland G, Goodman MT, Harrell J, Lynch CF, Pawlish K, et al. Cancer stage at diagnosis in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus and transplant recipients. Cancer. (2015) 121:2063–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29324

76. Gallioli A, Uleri A, Verri P, Tedde A, Mertens LS, Moschini M, et al. Oncologic outcomes of endoscopic management of upper tract urothelial carcinoma: A systematic review and pooled analysis from the EAU-YAU urothelial working group. Eur Urol Focus. (2025) 11:482–95. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2025.01.009

77. Manassero F, Di Paola G, Mogorovich A, Giannarini G, Boggi U, and Selli C. Orthotopic bladder substitute in renal transplant recipients: experience with Studer technique and literature review. Transpl Int. (2011) 24:943–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01292.x

78. Pradere B, Schuettfort V, Mori K, Quhal F, Aydh A, Sari Motlagh R, et al. Management of de-novo urothelial carcinoma in transplanted patients. Curr Opin Urol. (2020) 30:467–74. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000749

79. Dhar NB, Klein EA, Reuther AM, Thalmann GN, Madersbacher S, Studer UE, et al. Outcome after radical cystectomy with limited or extended pelvic lymph node dissection. J Urol. (2008) 179:873–8; discussion 878. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.10.076

80. Atallah A, Rady MR, Kamal HM, El-Mansy N, Alsawy MFM, Hegazy A, et al. Telovelar approach to pediatric fourth ventricle tumors: feasibility and outcome. Turk Neurosurg. (2019) 29:497–505. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.24078-18.3

81. Yavuzsan AH, Yesildal C, Kirecci SL, Ilgi M Sr, and Albayrak AT. Radical cystectomy and ileal conduit diversion for bladder urothelial carcinoma with sarcomatoid and squamous variants after renal transplantation. Cureus. (2020) 12:e7935. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7935

82. Ketsuwan C, Sangkum P, Sirisreetreerux P, Viseshsindh W, Patcharatrakul S, and Kongcharoensombat W. Laparoscopic bilateral nephro-ureterectomy approach for complete urinary tract extirpation for the treatment of multifocal urothelial carcinoma in a kidney transplant patient: A case report and literature review. Transplant Proc. (2015) 47:2265–9. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.07.020

83. Du C, Zheng M, Wang Z, Zhang J, Lin J, Zhang L, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of kidney transplant recipients with de novo urothelial carcinoma: thirty years of experience from a single center. BMC Urol. (2023) 23:71. doi: 10.1186/s12894-023-01232-7

84. Zhang P, Zhang XD, Wang Y, and Wang W. Feasibility of pre- and postoperative gemcitabine-plus-cisplatin systemic chemotherapy for the treatment of locally advanced urothelial carcinoma in kidney transplant patients. Transplant Proc. (2013) 45:3293–7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.06.008

85. Wang ZP, Wang WY, Zhu YC, Xiao J, Lin J, Guo YW, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus cisplatin for kidney transplant patients with locally advanced transitional cell carcinoma: A single-center experience. Transplant Proc. (2016) 48:2076–9. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.02.075

86. Neuzillet Y, Cabaniols L, Karam G, Salomon L, Barrou B, Petit J, et al. Study of urothelial bladder tumours in renal transplant recipients. Prog Urol. (2006) 16:343–6.

87. Elkentaoui H, Robert G, Pasticier G, Bernhard JC, Couzi L, Merville P, et al. Therapeutic management of de novo urological Malignancy in renal transplant recipients: the experience of the French Department of Urology and Kidney Transplantation from Bordeaux. Urology. (2010) 75:126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.106

88. Dalbagni G, Russo P, Sheinfeld J, Mazumdar M, Tong W, Rabbani F, et al. Phase I trial of intravesical gemcitabine in bacillus Calmette-Guérin-refractory transitional-cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Clin Oncol. (2002) 20:3193–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.066

89. Alkassis M, Abi Tayeh G, Khalil N, Mansour R, Lilly E, Sarkis J, et al. The safety and efficacy of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin intravesical therapy in kidney transplant recipients with superficial bladder cancer. Clin Transplant. (2021) 35:e14377. doi: 10.1111/ctr.14377

90. Prabharasuth D, Moses KA, Bernstein M, Dalbagni G, and Herr HW. Management of bladder cancer after renal transplantation. Urology. (2013) 81:813–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.11.035

91. Ziegler J, Ho J, Gibson IW, Nayak JG, Stein M, Walkty A, et al. Disseminated Mycobacterium bovis infection post-kidney transplant following remote intravesical BCG therapy for bladder cancer. Transpl Infect Dis. (2018) 20:e12931. doi: 10.1111/tid.12931

92. Gupta G, Kuppachi S, Kalil RS, Buck CB, Lynch CF, Engels EA, et al. Treatment for presumed BK polyomavirus nephropathy and risk of urinary tract cancers among kidney transplant recipients in the United States. Am J Transplant. (2018) 18:245–52. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14530

93. Powles T, Bellmunt J, Comperat E, De Santis M, Huddart R, Loriot Y, et al. Bladder cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. (2022) 33:244–58. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.11.012

94. Jain RK, Snyders T, Nandagopal L, Garje R, Zakharia Y, Gupta S, et al. Immunotherapy advances in urothelial carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. (2018) 19:79. doi: 10.1007/s11864-018-0598-x

95. Lai HC, Lin JF, Hwang TIS, Liu YF, Yang AH, and Wu CK. Programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors in renal transplant patients with advanced cancer: A double-edged sword? Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 20:2194. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092194

96. Huang H, Dai Z, Jiang Z, Li X, Ma L, Ji Z, et al. Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy for the treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma in a kidney transplant recipient: a case report. BMC Nephrol. (2024) 25:390. doi: 10.1186/s12882-024-03825-2

97. Wu CK, Juang GD, and Lai HC. Tumor regression and preservation of graft function after combination with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy without immunosuppressant titration. Ann Oncol. (2017) 28:2895–6. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx409

98. Hanna KS. Clinical overview of enfortumab vedotin in the management of locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Drugs. (2020) 80:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01241-7

99. Alt M, Stecca C, Tobin S, Jiang DM, and Sridhar SS. Enfortumab Vedotin in urothelial cancer. Ther Adv Urol. (2020) 12:1756287220980192. doi: 10.1177/1756287220980192

100. You X, Zhu C, Yu P, Wang X, Wang Y, Wang J, et al. Emerging strategy for the treatment of urothelial carcinoma: Advances in antibody-drug conjugates combination therapy. BioMed Pharmacother. (2024) 171:116152. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116152

101. Naesens M, Kuypers DR, and Sarwal M. Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2009) 4:481–508. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04800908

102. Vanhove T, Annaert P, and Kuypers DR. Clinical determinants of calcineurin inhibitor disposition: a mechanistic review. Drug Metab Rev. (2016) 48:88–112. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2016.1151037

103. Knoll GA, Kokolo MB, Mallick R, Beck A, Buenaventura CD, Ducharme R, et al. Effect of sirolimus on Malignancy and survival after kidney transplantation: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMJ. (2014) 349:g6679. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6679

104. Hu XP, Ma LL, Wang Y, Yin H, Wang W, Yang XY, et al. Rapamycin instead of mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine in treatment of post-renal transplantation urothelial carcinoma. Chin Med J (Engl). (2009) 122:35–8.

105. Chang YL, Lee HC, Luo HL, Chen YT, Chiang PH, and Cheng YT. Preventive role of mTOR inhibitor in post-kidney transplant urothelial carcinoma. Transplant Proc. (2019) 51:2731–4. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.03.059

106. Besarani D and Cranston D. Urological Malignancy after renal transplantation. BJU Int. (2007) 100:502–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07049.x

107. Luo HL, Chiang PH, Cheng YT, and Chen YT. Propensity-matched survival analysis of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinomas between end-stage renal disease with and without kidney transplantation. BioMed Res Int. (2019) 2019:2979142. doi: 10.1155/2019/2979142

108. Li S, Zhang J, Tian Y, Zhu Y, Guo Y, Wang Z, et al. De novo upper tract urothelial carcinoma after renal transplantation: a single-center experience in China. BMC Urol. (2023) 23:23. doi: 10.1186/s12894-023-01190-0

Keywords: kidney transplantation, urothelial carcinoma, pathogenic characteristics, diagnosis, treatment strategies

Citation: Li L, Ren F, Liu Z, Tian X, Zhang H, Wang G, Zhang S and Ma L (2025) Urothelial carcinoma following kidney transplantation: a narrative review of Chinese insights and challenges from pathogenesis to precision diagnosis and treatment. Front. Immunol. 16:1668356. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1668356

Received: 17 July 2025; Accepted: 25 November 2025; Revised: 18 November 2025;

Published: 12 December 2025.

Edited by:

Angela Gonzalez, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Alessio Pecoraro, University of Florence, ItalyTzu-Chun Cheng, China Medical University, Taiwan

Sung-Lang Chen, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taiwan

Copyright © 2025 Li, Ren, Liu, Tian, Zhang, Wang, Zhang and Ma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shudong Zhang, c2hvb3RvbmdAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Lulin Ma, bWFsdWxpbnBrdUAxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Lei Li

Lei Li Fei Ren

Fei Ren Zhuo Liu1

Zhuo Liu1 Lulin Ma

Lulin Ma