- 1Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin, China

- 2Tianjin Institute of Digestive Disease, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin, China

The gut microbiota plays a fundamental role in establishing and maintaining host immune homeostasis through dynamic, bidirectional interactions with the innate and adaptive immune systems. This review synthesizes current knowledge on how commensal microbes guide the development and function of the intestinal immune system. Conversely, we examine how the host immune system, including immunoglobulin A (IgA) and T-cell responses, actively shapes microbial composition and colonization resistance. Disruptions in this equilibrium (dysbiosis) are critically implicated in pathogenesis. We explore the dysbiosis-immune axis in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and colorectal cancer (CRC), highlighting how specific microbial taxa and their metabolites influence disease progression through immune modulation. Furthermore, we discuss how acute infectious insults model the breakdown of this mutualism.

1 introduction

The mammalian organism hosts an extensive consortium of microorganisms across epithelial surfaces, notably within gastrointestinal, cutaneous, and mucosal niches, collectively designated as the microbiome (1). Among these sites, the intestinal tract sustains the highest microbial density and phylogenetic diversity relative to other host compartments (2). Inhabiting the human gut are approximately 1,500 bacterial species and 100 trillion microbial cells, whose collective genome encodes over tenfold more unique genes than the human genome (3, 4). Contemporary research underscores that gut microbiota dynamically modulates essential host physiological processes—spanning circadian regulation, nutrient assimilation, metabolic pathways, and immune function—rather than operating as inert residents (5, 6).

This host-microbiota interface represents an evolutionary co-adaptation spanning millennia, fundamentally characterized by mutualistic symbiosis (7). Ecologically, mammals and commensal microorganisms have co-evolved to establish homeostatic equilibrium (8). Through persistent immunological stimulation, the complex gut microbial community critically orchestrates the development and functional maturation of both innate and adaptive immunity (9, 10). In physiological states, microbiota-derived metabolites—generated via anaerobic fermentation of dietary substrates and host-microbial co-metabolites—serve as key immunomodulatory messengers (11). Specifically, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and related compounds directly interface with host cellular receptors to fine-tune immune responses (12). The gut immune system reciprocally influences the gut microbiota. It establishes immune tolerance toward commensal and harmless microorganisms while maintaining effective immune responses against pathogenic infections. Under healthy conditions, this host immune response to the intestinal microbiota is strictly compartmentalized to the mucosal surface (13). Therefore, the gut microbiota and the host immune system exhibit significant bidirectional regulation.

However, this meticulously balanced host-microbiota symbiosis is vulnerable to disruption. Pathological alterations in the gut microbial ecosystem, termed dysbiosis, are increasingly recognized as critical factors in the pathogenesis of a spectrum of intestinal disorders (14–17). Critically, immune dysregulation constitutes a central mechanistic link underpinning these conditions. Mounting evidence positions the gut microbiome as a pivotal regulator of immune ontogeny, response calibration, and mucosal barrier integrity (18). Consequently, disruptions in the intricate dialogue between the microbiota and the host immune system—encompassing failures in tolerance induction, aberrant inflammatory responses, and compromised barrier function—are implicated in the initiation and perpetuation of chronic inflammation observed in diseases such as IBD, IBS, and CRC. In this review, we synthesize current mechanistic insights into this bidirectional microbiota-immune crosstalk across both physiological homeostasis and major intestinal pathologies. Furthermore, we evaluate emerging therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating this critical axis to restore health, highlighting the pivotal role of understanding these interactions for developing novel interventions against dysbiosis-associated intestinal diseases.

2 Microbiota-immune interplay in physiological conditions

2.1 Microbiota-driven maturation and maintenance of intestinal immunity

Early colonization of mucosal surfaces in mammalian hosts plays a decisive role in immune system maturation (19). While debate continues regarding prenatal microbial exposure in utero, overwhelming evidence confirms a substantial microbial influx immediately after birth, predominantly derived from maternal microbiota (20, 21). Delivery mode critically shapes initial microbial composition: vaginally delivered infants acquire microbes resembling maternal vaginal/enteric communities (e.g., Lactobacillus, Prevotella), whereas cesarean-delivered neonates are colonized by skin-associated taxa (e.g., Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium) (22). Beyond providing passive immunity through maternal antibodies, breast milk induces commensal microbiota-dependent protective immunity, as demonstrated in germ-free models (18, 20).

The first three years of life constitute a critical developmental window characterized by high microbiota volatility preceding stabilization into adult-like configurations (23–25). This plasticity increases vulnerability to environmental microbial perturbations that may disrupt immunoregulatory circuits with lifelong consequences (26). Early-life microbial colonization limits the expansion of invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells, in part via production of sphingolipids, to prevent potential disease-promoting activity within the intestinal lamina propria and the lungs (27). Neonatal immune immaturity manifests clinically as heightened pathogen susceptibility – with infectious diseases representing leading causes of childhood mortality – and dysregulated inflammation, exemplified by necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in preterm infants (28–30).

Studies using germ-free mice reveal mechanistic insights into microbiota-driven immune maturation. These microbiome-deficient animals exhibit multiple immunological deficits: impaired development of gut-associated lymphoid tissues; 30% reduction in αβ/γδ intraepithelial lymphocytes; absence of intestinal lamina propria Th17 cells (inducible by segmented filamentous bacteria colonization); diminished Th1 responses compromising intracellular pathogen clearance; and markedly reduced IgA secretion – all reversible upon microbial colonization (31–37).

Collectively, early-life microbial colonization orchestrates immune development through three interconnected pathways: 1) Initial seeding mechanisms (birth mode and feeding) establish foundational microbiota architecture; 2) Dynamic microbiota-immune crosstalk during the plasticity window of less than 3 years directs tolerance programming; 3) Microbial antigens directly drive lymphoid tissue maturation and T-cell differentiation. Disruption of this process predisposes to either immunodeficiency or pathological inflammation, underscoring the necessity of maintaining early microbiota homeostasis for lifelong immune competence. germ-free animal models remain indispensable for mechanistic dissection, though future research must address strain-specific functions and clinical translation challenges.

Crucially, the influence of the gut microbiota on immune function extends far beyond early development and persists throughout adulthood in healthy individuals. In the mature gut, the established commensal community plays an indispensable role in the continuous maintenance, education, and fine-tuning of the immune system.

Perpetual Antigenic Stimulation & Immune Training: The diverse microbial antigens provide constant, low-level stimulation to the intestinal immune system. This persistent exposure is essential for maintaining the pool and functionality of resident immune cells, including lamina propria lymphocytes (e.g., Th17, Tregs, IELs), innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), and antigen-presenting cells (APCs) like dendritic cells and macrophages. It trains these cells to distinguish between commensals and pathogens, reinforcing immune tolerance towards the former while preserving vigilance against the latter (38, 39).

Metabolite-Mediated Immunomodulation: Microbiota-derived metabolites, particularly SCFAs like butyrate, propionate, and acetate, remain critical immunomodulatory messengers in the adult gut. SCFAs signal through G-protein-coupled receptors (GPR41, GPR43, GPR109a) and inhibit histone deacetylases (HDACs) in various immune cells. This promotes anti-inflammatory responses, enhances epithelial barrier integrity, drives the differentiation and function of regulatory T cells (Tregs), and modulates macrophage and dendritic cell function towards a tolerant phenotype (40–42).

Maintenance of Barrier Surveillance and IgA Dynamics: The healthy adult microbiota continuously stimulates IgA production by plasma cells in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). IgA, particularly secretory IgA (sIgA), plays a vital role in coating commensal bacteria, restricting their penetration into the epithelium and lamina propria, shaping microbial composition, and neutralizing potential pathobionts. This dynamic IgA coating is a hallmark of adult immune-microbiota mutualism (43, 44).

Sustaining Innate Effector Functions: Commensals continue to prime systemic innate immunity in adults. For example, microbial components (e.g., peptidoglycan fragments detected by NOD1) enhance neutrophil bone marrow egress and functional readiness. Microbiota-derived signals also maintain the “inflammatory anergy” of intestinal macrophages, preventing inappropriate activation against commensals (45–47).

Adaptation to Environmental Changes: The adult microbiota-immune axis allows for adaptation. Changes in diet, transient pathogen exposure, or mild stressors can induce shifts in microbial composition and metabolite profiles. A well-established immune system, calibrated by the microbiota, can dynamically respond to these shifts, restoring homeostasis without triggering chronic inflammation (48).

Therefore, the adult gut microbiota is not merely a passive resident but an active participant in a continuous, bidirectional crosstalk essential for sustaining immune quiescence, barrier defense, and the capacity for appropriate inflammatory responses throughout life. Disruption of this mature equilibrium (dysbiosis) can lead to immune dysfunction and contribute to disease pathogenesis, as discussed in subsequent sections.

2.2 Interactions between the innate immune system and the microbiota

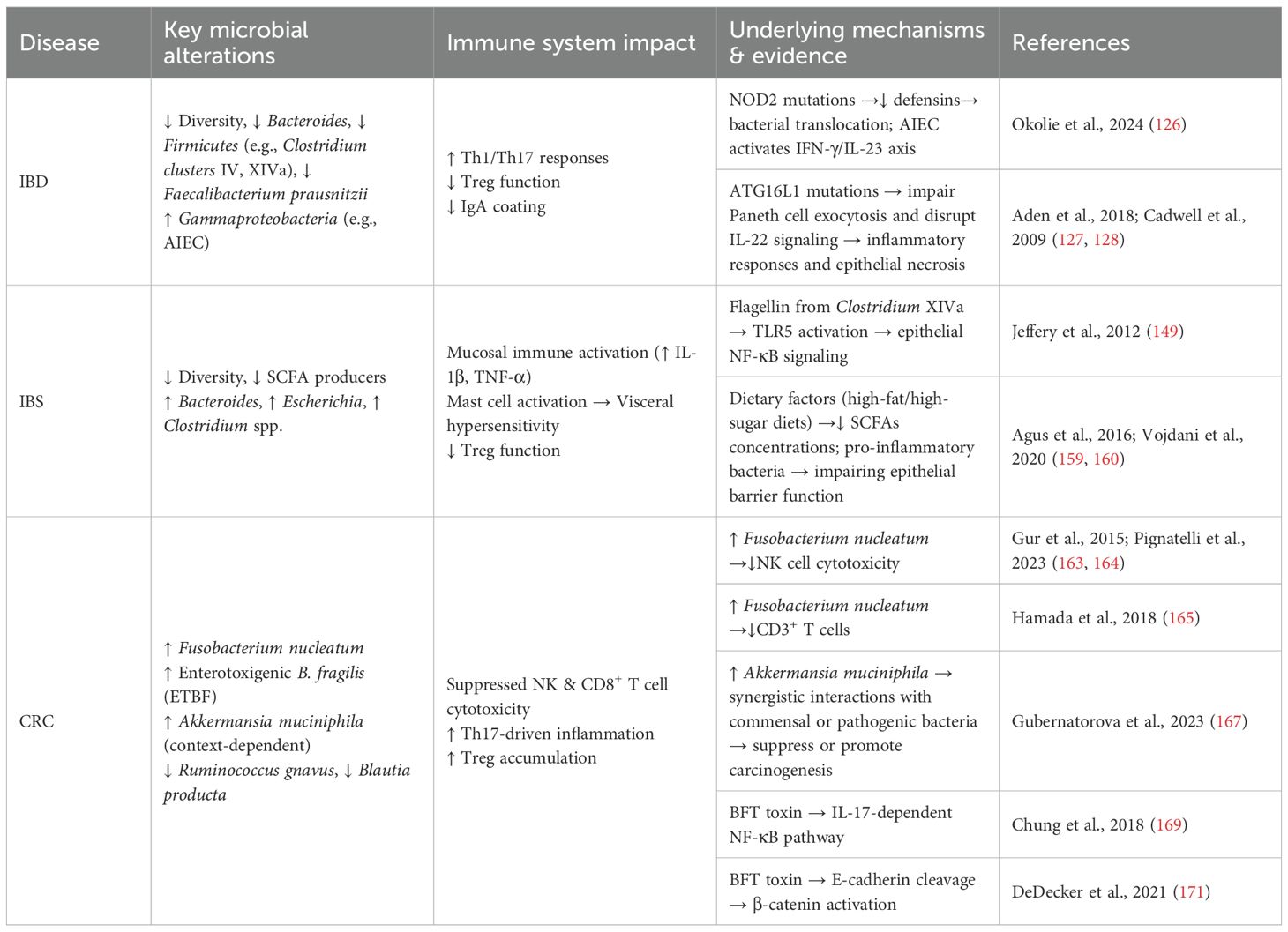

The gut microbiota critically shapes innate immunity through multifaceted molecular dialogues involving both local mucosal environments and systemic immune compartments (Figure 1). Microbial-derived ligands—including Toll-like receptor (TLR) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD) agonists—as well as immunomodulatory metabolites such as SCFAs and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligands, engage host pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to fine-tune immune activation and maintain homeostasis (49).

Figure 1. Intestinal microbiota-immunity interplay in homeostasis. TLR, Toll-like receptor; NOD, Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein; IL-10, Interleukin-10; IL-17, Interleukin-17; IL-4, Interleukin-4; IL-13, Interleukin-13; IL-22, Interleukin-22; IL-23, Interleukin-23; ILC3, group 3 innate lymphoid cell; Th17, T helper 17 cell; MHCII, Major histocompatibility complex class II; Treg, Regulatory T cell; iNKT, Invariant natural killer T cell; TGF-β, Transforming growth factor beta; iTregs, Induced regulatory T cell; SCFAs, Short-chain fatty acids; AhR, Aryl hydrocarbon receptor; PSA, Polysaccharide A; DC, Dendritic cell (Created in https://BioRender.com).

2.2.1 Mucosal programming of APCs

Commensal organisms have co-evolved with intestinal immune cells to promote immunological tolerance while preserving responsiveness to pathogens. Dendritic cells (DCs) in Peyer’s patches, for example, secrete significantly higher levels of interleukin-10 (IL-10) relative to splenic DCs under comparable stimuli, reflecting niche-specific tolerogenic adaptation (50). Intestinal macrophages exhibit a unique phenotype termed “inflammatory anergy,” whereby pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) is suppressed even in the presence of TLR ligands (45–47). This regulatory phenotype is microbiota-dependent and essential for sustaining mucosal tolerance (37). Furthermore, group 3 ILC(ILC3s) express MHC class II molecules that suppress activation of commensal-specific CD4+ T cells, serving as a checkpoint to prevent aberrant immune responses (51).

Mechanistically, microbiota-derived ATP activates P2X receptors on CD70+ intestinal DCs, promoting differentiation of RORγt+ Th17 cells via IL-6 and IL-23 pathways (52, 53). Germ-free models reinforce this dependence: monocolonization with Escherichia coli restores depleted intestinal DC populations without affecting systemic counterparts (37).

2.2.2 Systemic modulation of innate effector cells

Beyond the intestinal milieu, the microbiota exerts systemic effects on innate immunity. Germ-free mice display pronounced neutropenia, with a 30–40% reduction in circulating neutrophils, accompanied by compromised phagocytic activity and diminished production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (54–57). These defects are only partially reversed upon recolonization, indicating critical windows for microbial imprinting.

A pivotal role is played by NOD1, a cytosolic PRR that recognizes peptidoglycan fragments from Gram-negative bacteria. NOD1 activation enhances neutrophil myeloperoxidase activity and promotes their egress from bone marrow, effectively linking gut microbial sensing to peripheral immune readiness (58). Additionally, the microbiota influences natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity and mast cell protease expression, although the underlying pathways remain incompletely elucidated (59–61).

2.2.3 PRRs as regulators of microbiota composition

Host PRRs not only respond to microbial cues but actively modulate microbial ecology. Mice deficient in TLR5 exhibit significant shifts in microbiota composition—specifically, expansion of Proteobacteria and reduction in Bacteroidetes—alongside increased susceptibility to colitis, obesity, and metabolic syndrome (62–65). Similar dysbiosis has been observed in NOD1-, NOD2-, and NLRP6-deficient models, implicating cytosolic and inflammasome-associated PRRs in maintaining microbial homeostasis (66–69).

Notably, inflammasome dysfunction—particularly NLRP6 deficiency—results in transmissible dysbiosis mediated by impaired goblet cell mucin secretion and reduced antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) expression. Such microbiota shifts can propagate metabolic and inflammatory disorders to co-housed wild-type animals (69).

This collective evidence underscores a crucial paradigm: the innate immune system is not a passive sensor but an active architect of the gut microbial environment. Through the continuous expression of PRRs and effector molecules like AMPs, the host shapes the taxonomic composition and functional potential of the microbiota, determining which species can thrive in the intestinal niche. This active sculpting prevents the expansion of pro-inflammatory taxa and enforces a homeostatic community structure that is mutually beneficial. Thus, the dialogue between innate immunity and the microbiota is fundamentally bidirectional; innate signals educate the immune system, while immune mechanisms, in turn, mold the microbiota.

2.2.4 AMPs and microbial spatial organization

Paneth cells in the intestinal crypts secrete α-defensins and RegIIIγ, which constitute essential components of the mucosal chemical barrier. These AMPs maintain the sterility of the inner mucus layer and prevent microbial encroachment. Deficiency in these peptides disrupts spatial segregation, resulting in bacterial translocation into epithelial niches and subsequent epithelial hyperplasia via TLR signaling (70–73). Similarly, structural defects in the mucus layer compromise barrier integrity and foster pro-inflammatory microbial shifts (74).

In summary, microbiota-derived signals program innate immunity through PRR-mediated tolerance induction, systemic effector priming, and AMPs-dependent spatial containment. Disruption of this intricate crosstalk establishes a permissive environment for metabolic and inflammatory disorders.

2.3 Crosstalk between the adaptive immune system and the microbiota

The adaptive immune system has co-evolved with the gut microbiota to establish a highly specialized and reciprocal relationship essential for maintaining intestinal homeostasis. This mutualistic interaction is evident from studies showing pronounced microbial dysbiosis in immunodeficient mice lacking functional T or B cells (75). Two principal immunological axes underlie this crosstalk: T cell–mediated regulation of microbial composition and secretory IgA–dependent maintenance of mucosal equilibrium, with T cells playing a dominant role in shaping microbiota configuration (76). It is increasingly clear that the adaptive immune system exerts profound selective pressure on the microbiota, effectively functioning as a sophisticated ecological filter that determines microbial fitness and enforces community stability.

2.3.1 CD4+ T cell subset differentiation orchestrated by commensals

Within the intestinal microenvironment, microbial antigens direct the lineage commitment of naïve CD4+ T cells into distinct functional subsets—including Th1, Th2, Th17, and Tregs—thereby sculpting immune tone and microbial tolerance. Conversely, the resulting cytokine milieu actively feeds back to shape the microbial landscape. For instance, the IL-17 and IL-22 produced by Th17 cells stimulate epithelial cells to secrete AMPs, which directly target specific bacteria and influence community assembly. Similarly, the anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 and TGF-β derived from Tregs promote a tolerogenic environment that favors the persistence of beneficial, anti-inflammatory commensals. This creates a self-reinforcing loop where microbes induce specific T cell responses, which then modify the environment to favor or suppress different microbial groups.

Th1/Th2 Axis Regulation: Germ-free mice exhibit a Th2-skewed cytokine milieu, typified by elevated IL-4 and IL-5 levels, which correlates with increased susceptibility to allergic diseases such as asthma and eczema (77–79). Colonization with Bacteroides fragilis, through its capsular polysaccharide A (PSA), re-establishes Th1/Th2 equilibrium. PSA is internalized by lamina propria dendritic cells via a TLR2-dependent pathway, leading to the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into IL-10–secreting inducible Tregs (iTregs) or, in the presence of IL-23, Th17 cells (80).

Functional Dichotomy of Th17 Cells: Specific microbiota members shape distinct Th17 phenotypes. Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) elicit homeostatic, non-pathogenic Th17 cells, whereas pathogens such as Citrobacter rodentium induce inflammatory Th17 responses (81, 82). Mechanistically, SFB colonization activates the ILC3–IL-22–SAA axis, promoting IL-17A expression in RORγt+ Th17 cells (81). Although SFB is scarcely detected in the human microbiome, other taxa such as Eggerthella lenta may assume equivalent immunomodulatory roles (83).

Tregs Expansion and Function: Clostridium clusters IV and XIVa promote colonic Tregs accumulation via SCFAs production, while PSA from B. fragilis signals through TLR2 to suppress Th17-driven inflammation (84, 85). Colonic Tregs often bear microbiota-reactive TCRs and low Helios expression, indicating peripheral induction. Moreover, T follicular helper (Tfh) and exTh17 cells in Peyer’s patches contribute to B cell class-switch recombination and sIgA production, reinforcing microbiota compartmentalization and compositional control (86, 87).

2.3.2 IgA-mediated regulation of mucosal microbial ecology

SIgA represents a critical effector of adaptive immunity at mucosal surfaces, mediating immune exclusion, neutralization, and microbial homeostasis. The functional relevance of IgA is underscored by its dependency on T cell help for class switching and antigen specificity. Crucially, IgA is a principal mechanism by which the host actively and continuously shapes the gut microbiota. Rather than simply neutralizing pathogens, IgA imposes a selective pressure that governs bacterial gene expression, metabolic activity, and spatial distribution within the gut lumen.

T Cell–Dependent IgA Induction: In T cell–deficient models, Tregs are essential for restoring microbiota-reactive IgA responses (e.g., against flagellin), while Th17 cells promote antigen-specific IgA during mucosal perturbations (88–90). SFB uniquely co-induces both Th17 differentiation and IgA coating (91, 92). Germ-free mice require colonization with ≥109 CFU of viable bacteria to initiate robust IgA secretion (34).

Mechanisms of IgA-Mediated Homeostasis: IgA enforces microbial balance via several mechanisms. In AID-/- mice, which are deficient in class-switch recombination, SFB overgrowth can be reversed by IgA reconstitution (93, 94). Flagellin-specific IgA dampens bacterial flagellin expression, thereby reducing TLR5 activation and intestinal inflammation (95). Additionally, IgA suppresses Proteobacteria expansion during neonatal microbiota development (Mirpuri et al., 2014). Disruption of T cell–dependent IgA responses (e.g., via MyD88 deletion in T cells) alters IgA coating patterns, resulting in dysbiosis (96–98). High-affinity IgA not only immobilizes luminal microbes to prevent epithelial contact but also preserves microbiota diversity (87). This dynamic, antigen-specific selection is a quintessential example of the host immune system actively gardening its microbial inhabitants. The IgA repertoire adapts to the current microbial residents, and in doing so, it modulates their behavior and abundance, preventing the overdominance of any single strain and maintaining a diverse, stable ecosystem. This process is a continuous and active negotiation between the host and its microbiota.

Source and Distribution of IgA: GALT are rich in IgA+ plasma cells, which secrete up to 0.8 grams of IgA per meter of intestine per day (99). Germ-free mice exhibit marked reductions in both IgA-producing cells and intestinal IgA levels, as well as defective germinal center formation in the spleen (100, 101). They also show skewed immunoglobulin profiles, including elevated IgE and diminished IgG, indicative of a Th2-biased systemic state (102, 103). While BCR diversity is shaped by microbial exposure, the mechanisms underlying selective commensal tolerance remain incompletely understood (104).

2.3.3 Beyond CD4+ T cells and IgA: additional adaptive immune modulators

Although IgA and CD4+ T cells are central to microbiota-host dialogue, other adaptive immune components are also involved. For instance, CD8+ intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs), enriched in the gut epithelium, require microbial signals for functional competence and homeostasis. In germ-free mice, impaired clonal expansion of CD8+ IELs leads to diminished cytotoxic potential, compromising mucosal immunity (105). These IELs influence peripheral compartments, including marginal zone B cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (106).

In gut mucosal immunity, besides secretory sIgA, other immunoglobulins—IgG, IgE, and IgM—also contribute to immune regulation. IgG enters the lumen during barrier disruption (e.g., IBD), opsonizing microbes, activating complement, and driving inflammation, while also serving as a disease biomarker. IgE, low in healthy gut, can trigger mast cell degranulation in allergies and IBS, promoting hypersensitivity and dysmotility. IgM acts as a first-line defense and compensates for IgA deficiency via secretory IgM (sIgM), agglutinating microbes and moderating dysbiosis, though it cannot fully substitute IgA’s anti-inflammatory functions. Together, these antibodies coordinate to maintain intestinal immune homeostasis and contribute to pathology when dysregulated.

iNKT cells represent another subset regulated by the microbiota. Germ-free mice show iNKT immaturity and hypo-responsiveness, which can be reversed through colonization with B. fragilis or administration of microbial sphingolipids. These interventions enhance iNKT development and confer resistance to colitis (107).

In general, these findings underscore the intricate and dynamic interplay between the adaptive immune system and the gut microbiota. CD4+ T cell subsets—particularly Th17 and Tregs—respond to distinct microbial cues, thereby modulating intestinal immune tone and tolerance. Simultaneously, secretory IgA enforces microbial containment and compositional balance, not only as an effector of humoral immunity but also as a mediator of immune education. Additional adaptive elements further expand this regulatory network, highlighting the systemic impact of microbial signals. This bidirectional communication ensures that immune responses are appropriately calibrated to preserve mucosal integrity while accommodating the vast antigenic diversity of the gut microbiome. Understanding these interactions provides a foundation for therapeutic strategies targeting dysbiosis-related diseases, including IBD, allergies, and autoimmunity.

3 Dysbiosis-immune axis in in intestinal diseases

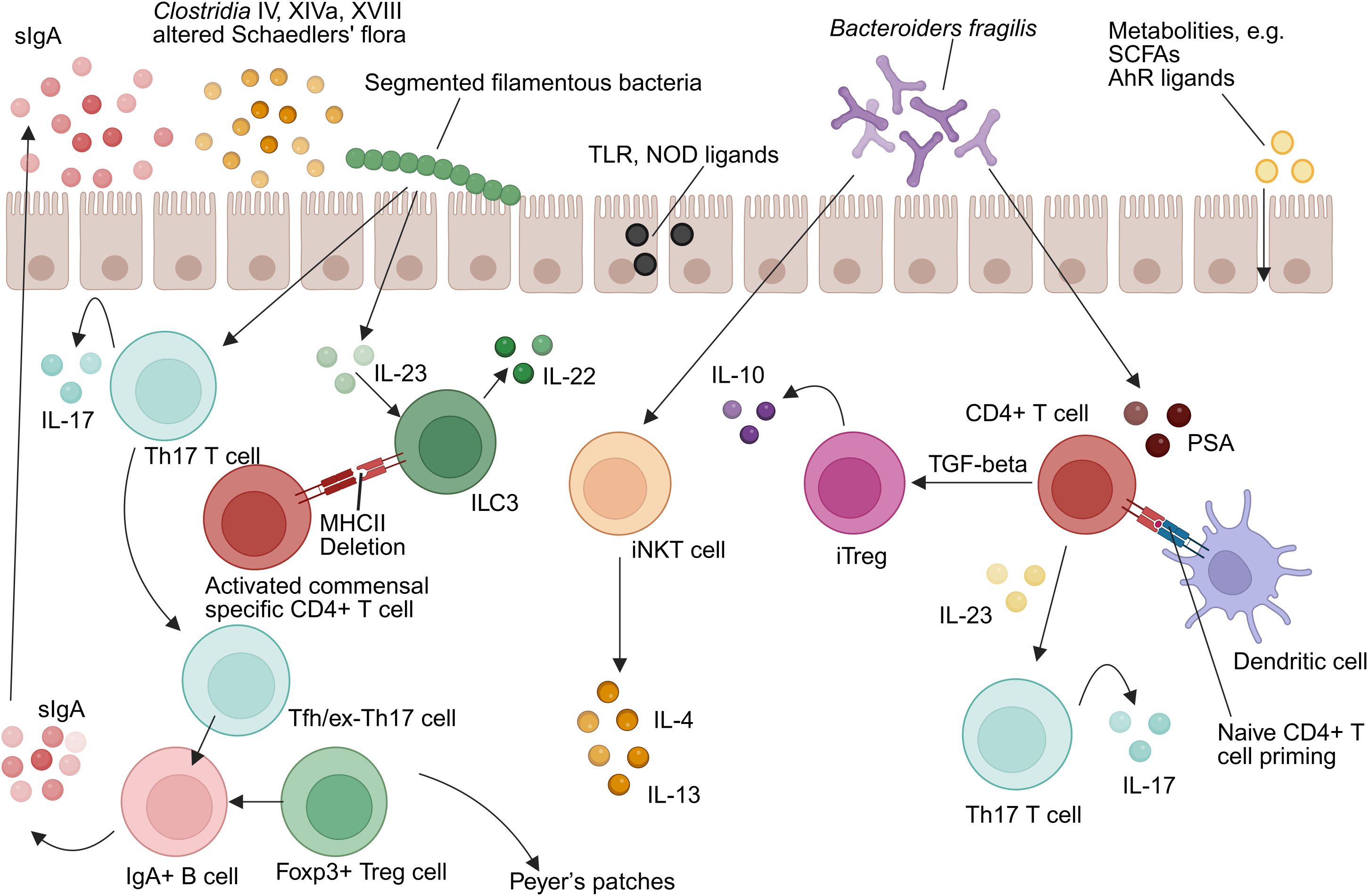

Mounting evidence indicates that dysbiosis-driven immune dysregulation serves as a cornerstone in the pathogenesis of intestinal pathologies (Figure 2). In genetically susceptible hosts, compromised mucosal barrier integrity—characterized by disrupted tight junctions and increased permeability—permits microbial metabolite translocation, initiating a cascade of inflammatory responses (108). This breach of intestinal homeostasis synergizes with immune imbalances: attenuated Tregs suppression, aberrant B cell activation, and skewed Th1/Th17 polarization collectively fuel chronic inflammation (109, 110). Critically, such maladaptations transcend the gut, with molecular mimicry mechanisms (e.g., microbial antigen cross-reactivity with host epitopes) linking enteric dysbiosis to systemic autoimmunity (111). While causal relationships remain under investigation, the convergence of genetic vulnerability (e.g., NOD2 mutations), environmental triggers (e.g., antibiotics/diet), and microbiome alterations establishes a permissive milieu for disease onset and progression. Below we delineate how these interactions manifest in specific intestinal and extra-intestinal disorders. an imbalance of intestinal immunity related to Th2 cytokines, while CD is associate to a Th1 and Th17 cytokine profile (Heller et al., 2005). In CD, differentiation into Th1 and Th17 occurs by induction of cytokines IL-12, IL-18, IL-23 and transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) produced by macrophages and other APC. In UC, increased secretion of IL-5, which is Th2 specific, is related to more effective activation of B cells and stimulation of immune responses when compared to the Th1 response observed in CD. Although the precise mechanisms underlying IBS remain unclear, it is widely recognized that its pathogenesis results from the interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental factors within the microbiome. This interaction, facilitated by a compromised intestinal epithelium, leads to excessive immune activation, which is thought to contribute to the clinical manifestations observed in IBD.

Figure 2. Dysregulation of microbiome-immunity interaction in disease. IBD, inflammatory bowel diseases; FMT, Fecal microbiota transplantation; Th17, T helper 17 cell; Th1, T helper 1 cell; Th2, T helper 2 cell; Treg, Regulatory T cell; SCFAs, Short-chain fatty acids; LPS, lipopolysaccharide(Created in https://BioRender.com).

3.1 IBD: microbial triggers of immune dysregulation

IBD, encompassing CD and UC, represents chronic, relapsing-remitting inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract exhibiting escalating global incidence (112). Compelling evidence implicates gut microbiome perturbations—dysbiosis—as central to IBD pathogenesis (18). Characteristically, IBD patients typically exhibit reduced bacterial diversity, with notable shifts in the abundance of specific bacterial taxa (113–115). For example, the abundances of Bacteroides, Firmicutes, Clostridia, Lactobacillus, and Ruminococcaceae decrease, while those of Gammaproteobacteria and Enterobacteriaceae increase (116, 117). Concurrently, the profiles of microbiome-associated metabolites are altered (118, 119).

To elucidate the underlying mechanisms, we turn to the role of epithelial integrity and genetic susceptibility. A critical pathophysiological event involves the breakdown of tightly regulated intestinal barrier integrity. This breach facilitates translocation of commensal bacteria into the mucosal lamina propria, triggering aberrant host immune activation and subsequent tissue damage (120). Barrier defects encompass multiple components: compromised mucus layer architecture (e.g., Muc2 deficiency, which precipitates spontaneous colitis and early dysbiosis in susceptible murine models), impaired epithelial tight junctions, and dysregulated AMPs secretion (121).

These structural vulnerabilities are further exacerbated by genetic predispositions that affect microbial sensing and immune response. Genome-wide association studies have identified >200 IBD susceptibility loci, many encoding proteins critical for microbial immune sensing and response (122). The NOD2 (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2) mutation, the first strongly associated CD risk allele, exemplifies this link (123). As an intracellular PRR detecting bacterial peptidoglycan, NOD2 regulates commensal ecology by modulating AMPs expression and suppressing expansion of pro-inflammatory species like Bacteroides vulgatus (124, 125). Dysfunctional microbiome-immune crosstalk consequent to NOD2 mutation is thus pivotal in CD development (126). Similarly, mutations in autophagy-related 16-like 1 (ATG16L1), another CD-associated allele, impair Paneth cell exocytosis and exacerbate inflammatory responses and epithelial necrosis via dysregulated IL-22 signaling (127, 128). Inflammasome signaling further modulates this axis; NLRP6 inflammasome perturbation, for instance, heightens susceptibility to murine colitis and potentiates inflammation in IL10-/- mice (129).

Beyond innate immunity, adaptive immune components significantly shape disease course. While the role of adaptive immunity—encompassing effector T cells, Tregs, and humoral responses—in expanding IBD-associated pathobionts is well-documented (130). establishing definitive causality between microbiome alterations and inflammation remains complex (111). Nonetheless, emerging evidence supports a contributory role for dysbiosis: Fecal microbiota transplantation from CD patients into germ-free mice harboring susceptibility genes triggers CD-like inflammation (131). Microbiota from IBD patients can also induce imbalances in intestinal Th17 and RORγt+ Tregs populations in germ-free recipients (132). Furthermore, specific pathobionts isolated from IBD patients, such as Mucispirillum schaedleri and adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC) strains, elicit colitis in susceptible murine models (133, 134).

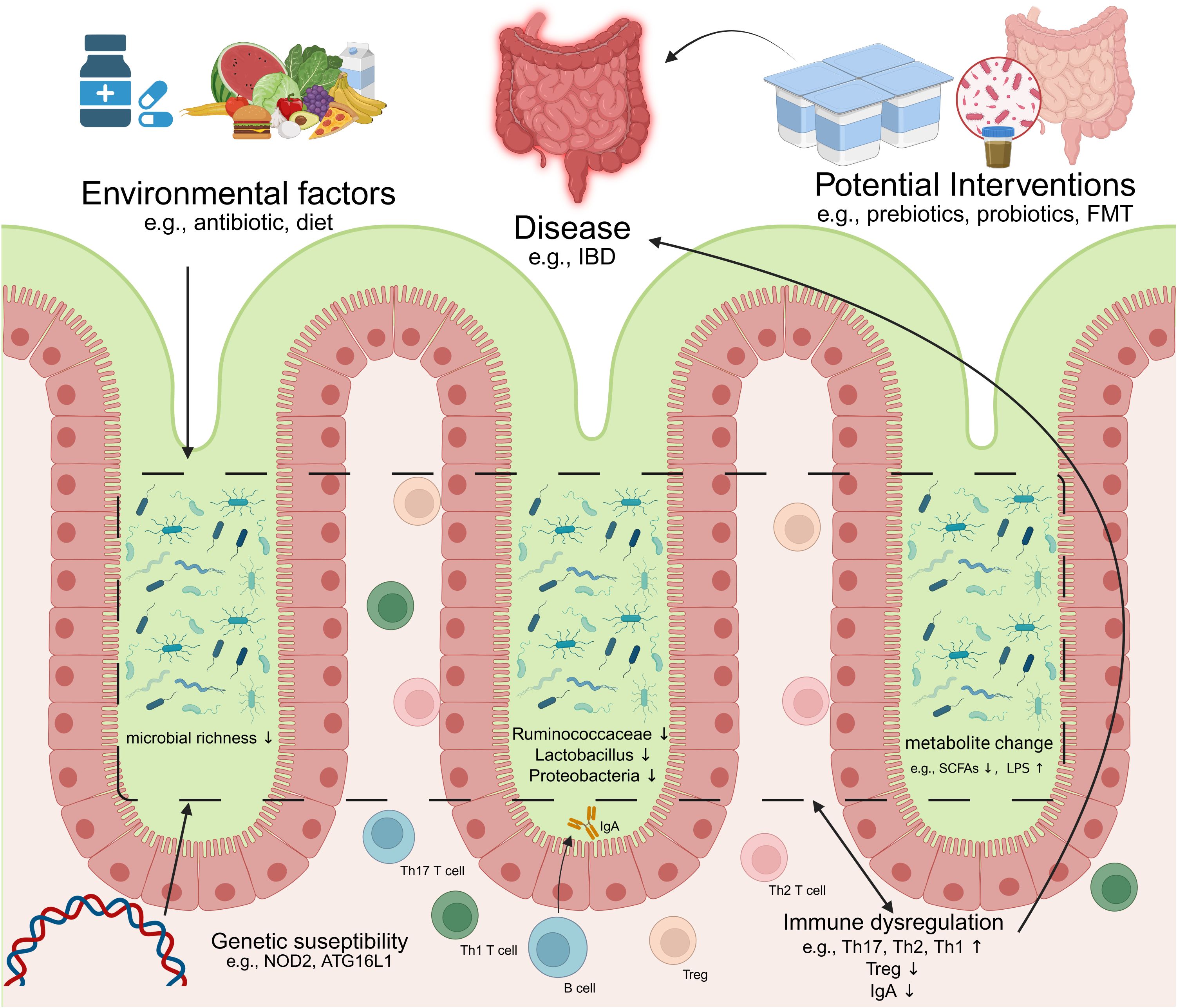

In conclusion, dysregulated crosstalk between the gut microbiome and host immune system constitutes a fundamental mechanism underpinning IBD pathogenesis (Table 1). Future research must prioritize elucidating the causal directionality of these interactions to inform targeted therapeutic interventions.

3.1.1 Acute infectious insults as a model of dysbiosis-immune dysregulation

Acute gastrointestinal infections model how a breach in host-microbiota mutualism precipitates immune dysfunction. The intestinal epithelium is the primary barrier, fortified by the resident microbiota. GF mice and animals deficient in microbial sensing (e.g., Nod2-/-, MyD88-/-) exhibit impaired AMPs production, compromising barrier integrity and facilitating pathogen translocation (135, 136). Deficiencies in AMPs (e.g., RegIIIγ) lead to elevated mucosal bacterial colonization (73).

The IL-22-regulated AMPs axis is critical for defense against enteric pathogens (137–140). sIgA, whose expression is modulated by microbiota, binds antigens and neutralizes pathogens (141–143). Systemically, the microbiota primes IL-1β for neutrophil mobilization and stimulates TH17 cell expansion, contributing to pathogen resistance (144).

3.2 IBS: gut microbiota–immune interplay and low-grade inflammation

IBS is increasingly recognized as a disorder driven by microbial perturbations and characterized by subtle yet persistent immunological disturbances (145). Unlike IBD, IBS lacks macroscopic inflammation and is instead marked by low-grade immune activation. In post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS), this is often initiated by acute enteric infections that compromise epithelial integrity, allowing microbial components to activate mucosal immunity (146). Approximately 10% of individuals who experience acute enteritis develop IBS symptoms, highlighting the link between barrier disruption and immune sensitization.

This chronic immune stimulation is frequently associated with gut dysbiosis. IBS patients often present with gut microbiota dysbiosis, characterized by reduced bacterial diversity, a depletion of beneficial taxa (e.g., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium), and an enrichment of pathobionts like Escherichia coli, Bacteroides, and Clostridium species (147, 148). These alterations are not merely associative; many of the enriched bacterial taxa express immune-activating molecules such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and flagellin, which engage PRRs on intestinal epithelial and immune cells, particularly TLR4 and TLR5, driving mucosal immune activation and barrier dysfunction (149).

From innate activation to adaptive immune consequences, further complexity arises in the immunopathology of IBS Increased intestinal permeability following infection allows microbial antigens to reach the lamina propria, where they stimulate dendritic cells, macrophages, and mast cells, triggering Th1 and Th17 differentiation (150–152). Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines—such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)—are frequently observed, while anti-inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-10, IL-13) are often suppressed (153, 154).

Microbial metabolites, particularly SCFAs such as butyrate, acetate, and propionate, play a pivotal role in modulating intestinal immunity and maintaining mucosal homeostasis (155). Produced through bacterial fermentation of dietary fibers, SCFAs exert their immunoregulatory effects by promoting the differentiation of Tregs via histone deacetylase inhibition, activating G-protein-coupled receptors (GPR43, GPR109A), and enhancing epithelial barrier integrity (40–42). However, SCFAs production is diminished in IBS patients due to dietary factors and depletion of key producers such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (156). Concurrently, other bacterial metabolites (e.g., histamine, 5-HT, dopamine) can directly modulate sensory nerve function, further amplifying nociceptive signaling (157, 158).

Lastly, we consider how environmental factors amplify this dysbiosis-immune feedback loop. Dietary patterns (e.g., high-fat, low-fiber intake) and psychological stress activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, releasing corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) that triggers mast cell activation and barrier dysfunction (159, 160). These changes perpetuate a vicious cycle wherein immune activation reshapes microbial niches, worsening dysbiosis.

In summary, IBS is increasingly recognized as an immunological disorder driven by microbial perturbations. The convergence of low-grade inflammation, dysregulated metabolite signaling, and neuroimmune sensitization establishes a new paradigm for understanding IBS and guiding microbiota-targeted therapies.

3.3 CRC: microbiota-mediated immune evasion and carcinogenesis

The gut microbiota critically modulates cancer immune surveillance through dynamic interactions with host immunity (18). CRC is the most common cancer of the digestive system with high mortality and morbidity rates (161). Compared to healthy individuals, patients with CRC exhibit reduced gut microbial diversity and distinct dysbiosis (162). Within the colorectal tumor microenvironment (TME), specific bacterial species actively impair antitumor immunity. A prominent example is Fusobacterium nucleatum, which accumulates in CRC tissues and directly inhibits NK cell cytotoxicity. This immunosuppressive effect is primarily mediated by the binding of the bacterial Fap2 protein to the inhibitory receptor TIGIT on NK cells (163, 164). Clinically, elevated abundance of F. nucleatum in human CRC correlates with reduced intratumoral infiltration of CD3+ T cells—a lymphocyte population associated with improved patient survival—further implicating this bacterium in promoting an immunosuppressive TME (165).

Furthermore, increased abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila in patients with epithelial tumors correlates positively with response to PD-1 blockade. This effect potentially involves the recruitment of CCR9+CXCR3+CD4+ T lymphocytes to tumors and enhanced IL-12 secretion (166). Research on A. muciniphila in CRC reveals context-dependent outcomes. Murine studies demonstrate conflicting roles: while some report protective effects, others show administration exacerbates tumorigenesis. Emerging consensus attributes these discrepancies to strain-specific properties, as A. muciniphila may degrade the mucin barrier and engage in synergistic interactions with commensal or pathogenic bacteria that either suppress or promote carcinogenesis (167).

Similarly, enterotoxigenic B. fragilis (BFT+) contributes to early carcinogenesis. Its secreted metalloproteinase toxin (BFT) is implicated in human colonic adenoma and serrated polyp formation, promotes Th17-mediated colitis in mouse models (168), and drives distal CRC in Apcmin+/− mice via IL-17-dependent NF-κB pathway activation (169). BFT+ B. fragilis colonization additionally facilitates regulatory T cell accumulation, inducing IL-17-driven procarcinogenic inflammation (170). At the epithelial level, BFT cleaves E-cadherin, increasing paracellular permeability and activating β-catenin signaling to enhance proliferation (171). It further induces DNA damage through polyamine catabolism in CRC cells (172). Notably, this bacterium promotes local dysbiosis by expanding other procarcinogenic species, compromising host immunity (170), disrupting the gut barrier (171), and degrading mucin (173).

In contrast, commensals like Ruminococcus gnavus and Blautia producta enhance antitumor immunity. They degrade lysoglycerophospholipids within the intestinal niche, thereby potentiating the tumor immune surveillance function of CD8+ T cells and inhibiting colon carcinogenesis (174).

4 Conclusion and future perspectives

The intricate bidirectional interplay between the gut microbiome and the host immune system is a cornerstone of intestinal health and a key factor in the pathogenesis of a spectrum of diseases. While this review has synthesized compelling evidence of how dysbiosis drives immune dysfunction in IBD, IBS, CRC, and following infection, it is crucial to recognize the significant limitations inherent in this rapidly evolving field. A primary challenge remains establishing definitive causality rather than correlation. While animal models, particularly gnotobiotic mice, have been indispensable for mechanistic dissection, they often fall short of recapitulating the full complexity of human physiology, genetics, and environmental exposures. The widely used inbred laboratory mice possess a depauperate microbiota and an immune system calibrated for this simplified community, which may yield exaggerated or misleading effects compared to humans harboring a far more complex and resilient microbial ecosystem. Furthermore, the staggering inter-individual heterogeneity in both microbiome composition and immune responses often exceeds differences related to disease status itself, complicating the identification of universal therapeutic targets and the translation of findings from population-level studies to the individual patient.

To overcome these hurdles and move from association to mechanism, future research must embrace a multi-faceted and integrative approach:

Multi-omics Integration: Disentangling causality will require the longitudinal collection and integrated analysis of multi-omics datasets—encompassing metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, metabolomics, metaproteomics, and host epigenomics—from well-characterized human cohorts. This will help bridge the gap between microbial taxonomy, gene expression, functional output, and host response, revealing the active drivers of immune modulation.

Next-Generation Animal Models: The field must transition beyond conventional laboratory mice. “Wildling” or “dirty” mouse models, which are colonized with a complex, naturalized microbiota from wild mice or human donors, offer a more physiologically relevant preclinical platform. These models exhibit immune responses closer to humans and can better predict the efficacy and safety of microbiota-targeted interventions.

Leveraging Artificial Intelligence: Machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) are poised to play a transformative role. These tools can decipher the immense complexity of multi-omics data, identify predictive biomarkers of disease susceptibility or treatment response, and ultimately build models for personalized microbiome medicine. AI can help navigate the heterogeneity problem by stratifying patients into subpopulations based on their unique microbiome-immune signatures.

Expanding the Microbiome Definition: Future studies must look beyond bacteria to fully incorporate the virome (phages), mycobiome (fungi), and archaea into the ecosystem-level understanding of host-microbe interactions. Their roles in modulating immune tone and influencing bacterial community dynamics are still poorly understood but are likely significant.

The therapeutic landscape targeting the microbiota-immune axis is promising yet fraught with challenges. While Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) has demonstrated proof-of-principle, its long-term safety, variable efficacy, and lack of standardized protocols necessitate caution. Next-generation live biotherapeutic products (LBPs) and precision prebiotics offer a more controlled approach but must demonstrate robust and reproducible effects in diverse human populations. Similarly, while postbiotic strategies (e.g., administering SCFAs) are attractive for their safety and defined nature, their efficacy may be limited by the redundancy and complexity of microbial metabolic networks in vivo.

In conclusion, while the past decade has yielded profound insights into the microbiota-immune dialogue, the path forward requires a critical acknowledgment of current limitations and a concerted effort to adopt more sophisticated, integrative, and human-relevant approaches. By harnessing the power of multi-omics, advanced animal models, and computational biology, the field can move beyond descriptive associations and toward a causal, mechanistic, and ultimately translational understanding of how to harness the microbiome for immune health. This refined knowledge is essential for developing the next generation of safe, effective, and personalized therapies for the multitude of diseases rooted in a disrupted microbiota-immune equilibrium.

Author contributions

QW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. YL: Writing – review & editing. XL: Writing – review & editing. JZ: Writing – review & editing. YM: Writing – review & editing. ZY: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Conceptualization, Supervision, Investigation. XC: Supervision, Validation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Sender R, Fuchs S, and Milo R. Are we really vastly outnumbered? Revisiting the ratio of bacterial to host cells in humans. Cell. (2016) 164:337–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.013

3. Ley RE, Peterson DA, and Gordon JI. Ecological and evolutionary forces shaping microbial diversity in the human intestine. Cell. (2006) 124:837–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.017

4. Robles-Alonso V and Guarner F. progress in the knowledge of the intestinal human microbiota. Nutricion Hospitalaria. (2013) 28:553–7. doi: 10.3305/nh.2013.28.3.6601

5. Hacquard S, Garrido-Oter R, González A, Spaepen S, Ackermann G, Lebeis S, et al. Microbiota and host nutrition across plant and animal kingdoms. Cell Host Microbe. (2015) 17:603–16. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.009

6. Lynch JB and Hsiao EY. Microbiomes as sources of emergent host phenotypes. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2019) 365:1405–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aay0240

7. Bäckhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, and Gordon JI. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2005) 307:1915–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816

8. Dethlefsen L, McFall-Ngai M, and Relman DA. An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human-microbe mutualism and disease. Nature. (2007) 449:811–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06245

9. Belkaid Y and Harrison OJ. Homeostatic immunity and the microbiota. Immunity. (2017) 46:562–76. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.008

10. Lathrop SK, Bloom SM, Rao SM, Nutsch K, Lio CW, Santacruz N, et al. Peripheral education of the immune system by colonic commensal microbiota. Nature. (2011) 478:250–4. doi: 10.1038/nature10434

11. Belkaid Y and Hand TW. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. (2014) 157:121–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011

12. Rooks MG and Garrett WS. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. (2016) 16:341–52. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.42

13. Konrad A, Cong Y, Duck W, Borlaza R, and Elson CO. Tight mucosal compartmentation of the murine immune response to antigens of the enteric microbiota. Gastroenterology. (2006) 130:2050–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.055

14. Hansen R, Russell RK, Reiff C, Louis P, McIntosh F, Berry SH, et al. Microbiota of de-novo pediatric IBD: increased faecalibacterium prausnitzii and reduced bacterial diversity in crohn’s but not in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. (2012) 107:1913–22. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.335

15. Littman DR and Pamer EG. Role of the commensal microbiota in normal and pathogenic host immune responses. Cell Host Microbe. (2011) 10:311–23. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.004

16. Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, Lakhdari O, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Gratadoux JJ, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2008) 105:16731–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804812105

17. Machiels K, Joossens M, Sabino J, De Preter V, Arijs I, Eeckhaut V, et al. A decrease of the butyrate-producing species roseburia hominis and faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. (2014) 63:1275–83. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304833

18. Zheng D, Liwinski T, and Elinav E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. (2020) 30:492–506. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0332-7

19. Gensollen T, Iyer SS, Kasper DL, and Blumberg RS. How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2016) 352:539–44. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9378

20. Gomez de Agüero M, Ganal-Vonarburg SC, Fuhrer T, Rupp S, Uchimura Y, Li H, et al. The maternal microbiota drives early postnatal innate immune development. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2016) 351:1296–302. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2571

21. Wang J, Zheng J, Shi W, Du N, Xu X, Zhang Y, et al. Dysbiosis of maternal and neonatal microbiota associated with gestational diabetes mellitus. Gut. (2018) 67:1614–25. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-315988

22. Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N, et al. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2010) 107:11971–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002601107

23. Bäckhed F, Roswall J, Peng Y, Feng Q, Jia H, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, et al. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe. (2015) 17:690–703. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.004

24. Koenig JE, Spor A, Scalfone N, Fricker AD, Stombaugh J, Knight R, et al. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2011) 108 Suppl 1:4578–85. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000081107

25. Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. (2012) 486:222–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11053

26. MacGillivray DM and Kollmann TR. The role of environmental factors in modulating immune responses in early life. Front Immunol. (2014) 5:434. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00434

27. Wingender G, Hiss M, Engel I, Peukert K, Ley K, Haller H, et al. Neutrophilic granulocytes modulate invariant NKT cell function in mice and humans. J Immunol (baltimore Md.: 1950). (2012) 188:3000–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101273

28. Bhutta ZA and Black RE. Global maternal, newborn, and child health–so near and yet so far. New Engl J Med. (2013) 369:2226–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1111853

29. Neu J and Walker WA. Necrotizing enterocolitis. New Engl J Med. (2011) 364:255–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1005408

30. Zhang X, Zhivaki D, and Lo-Man R. Unique aspects of the perinatal immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. (2017) 17:495–507. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.54

31. Chung H, Pamp SJ, Hill JA, Surana NK, Edelman SM, Troy EB, et al. Gut immune maturation depends on colonization with a host-specific microbiota. Cell. (2012) 149:1578–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.037

32. Damsker JM, Hansen AM, and Caspi RR. Th1 and Th17 cells: adversaries and collaborators. Ann New York Acad Sci. (2010) 1183:211–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05133.x

33. Fiebiger U, Bereswill S, and Heimesaat MM. Dissecting the interplay between intestinal microbiota and host immunity in health and disease: lessons learned from germfree and gnotobiotic animal models. Eur J Microbiol Immunol. (2016) 6:253–71. doi: 10.1556/1886.2016.00036

34. Hapfelmeier S, Lawson MAE, Slack E, Kirundi JK, Stoel M, Heikenwalder M, et al. Reversible microbial colonization of germ-free mice reveals the dynamics of IgA immune responses. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2010) 328:1705–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1188454

35. Hou K, Wu ZX, Chen XY, Wang JQ, Zhang D, Xiao C, et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. (2022) 7:135. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00974-4

36. Ivanov II, Frutos R de L, Manel N, Yoshinaga K, Rifkin DB, Sartor RB, et al. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host Microbe. (2008) 4:337–49. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.009

37. Wu HJ and Wu E. The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut Microbes. (2012) 3:4–14. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19320

38. Chun J and Toldi G. The impact of short-chain fatty acids on neonatal regulatory T cells. Nutrients. (2022) 14:3670. doi: 10.3390/nu14183670

39. Kim CH, Park J, and Kim M. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids, T cells, and inflammation. Immune Network. (2014) 14:277–88. doi: 10.4110/in.2014.14.6.277

40. Singh N, Gurav A, Sivaprakasam S, Brady E, Padia R, Shi H, et al. Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity. (2014) 40:128–39. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.007

41. Sun M, Wu W, Liu Z, and Cong Y. Microbiota metabolite short chain fatty acids, GPCR, and inflammatory bowel diseases. J Gastroenterol. (2017) 52:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1242-9

42. Wu SE, Hashimoto-Hill S, Woo V, Eshleman EM, Whitt J, Engleman L, et al. Microbiota-derived metabolite promotes HDAC3 activity in the gut. Nature. (2020) 586:108–12. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2604-2

43. Brandtzaeg P. Secretory IgA: designed for anti-microbial defense. Front Immunol. (2013) 4:222. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00222

44. Tejedor Vaquero S, Neuman H, Comerma L, Marcos-Fa X, Corral-Vazquez C, Uzzan M, et al. Immunomolecular and reactivity landscapes of gut IgA subclasses in homeostasis and inflammatory bowel disease. J Exp Med. (2024) 221:e20230079. doi: 10.1084/jem.20230079

45. Duan T, Du Y, Xing C, Wang HY, and Wang RF. Toll-like receptor signaling and its role in cell-mediated immunity. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:812774. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.812774

46. Smythies LE, Shen R, Bimczok D, Novak L, Clements RH, Eckhoff DE, et al. Inflammation anergy in human intestinal macrophages is due to smad-induced IkappaBalpha expression and NF-kappaB inactivation. J Biol Chem. (2010) 285:19593–604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.069955

47. Talwar C, Singh V, and Kommagani R. The gut microbiota: a double-edged sword in endometriosis†. Biol Reprod. (2022) 107:881–901. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioac147

48. Desai MS, Seekatz AM, Koropatkin NM, Kamada N, Hickey CA, Wolter M, et al. A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell. (2016) 167:1339–1353.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043

49. Shao T, Hsu R, Rafizadeh DL, Wang L, Bowlus CL, Kumar N, et al. The gut ecosystem and immune tolerance. J Autoimmun. (2023) 141:103114. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2023.103114

50. Iwasaki A and Kelsall BL. Freshly isolated peyer’s patch, but not spleen, dendritic cells produce interleukin 10 and induce the differentiation of T helper type 2 cells. J Exp Med. (1999) 190:229–39. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.2.229

51. Constantinides MG, McDonald BD, Verhoef PA, and Bendelac A. A committed precursor to innate lymphoid cells. Nature. (2014) 508:397–401. doi: 10.1038/nature13047

52. Atarashi K, Nishimura J, Shima T, Umesaki Y, Yamamoto M, Onoue M, et al. ATP drives lamina propria T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature. (2008) 455:808–12. doi: 10.1038/nature07240

53. Yamamoto S, Matsuo K, Sakai S, Mishima I, Hara Y, Oiso N, et al. P2X receptor agonist enhances tumor-specific CTL responses through CD70+ DC-mediated Th17 induction. Int Immunol. (2021) 33:49–55. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxaa068

54. Clarke TB, Davis KM, Lysenko ES, Zhou AY, Yu Y, and Weiser JN. Recognition of peptidoglycan from the microbiota by Nod1 enhances systemic innate immunity. Nat Med. (2010) 16:228–31. doi: 10.1038/nm.2087

55. Herb M and Schramm M. Functions of ROS in macrophages and antimicrobial immunity. Antioxidants (basel Switzerland). (2021) 10:313. doi: 10.3390/antiox10020313

56. Ohkubo T, Tsuda M, Suzuki S, El Borai N, and Yamamura M. Peripheral blood neutrophils of germ-free rats modified by in vivo granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor and exposure to natural environment. Scandinavian J Immunol. (1999) 49:73–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00456.x

57. Riaz B and Sohn S. Neutrophils in inflammatory diseases: unraveling the impact of their derived molecules and heterogeneity. Cells. (2023) 12:2621. doi: 10.3390/cells12222621

58. Abubakar J, Edo G, and Aydinlik NP. Phytochemical and GCMS analysis on the ethanol extract of foeniculum vulgare and petroselinum crispum leaves. Int J Chem Technol. (2021) 5:117–24. doi: 10.32571/ijct.911711

59. Kunii J, Takahashi K, Kasakura K, Tsuda M, Nakano K, Hosono A, et al. Commensal bacteria promote migration of mast cells into the intestine. Immunobiology. (2011) 216:692–7. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.10.007

60. Sanos SL, Bui VL, Mortha A, Oberle K, Heners C, Johner C, et al. RORgammat and commensal microflora are required for the differentiation of mucosal interleukin 22-producing NKp46+ cells. Nat Immunol. (2009) 10:83–91. doi: 10.1038/ni.1684

61. Zhang D and Frenette PS. Cross talk between neutrophils and the microbiota. Blood. (2019) 133:2168–77. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-11-844555

62. Carvalho FA, Koren O, Goodrich JK, Johansson MEV, Nalbantoglu I, Aitken JD, et al. Transient inability to manage proteobacteria promotes chronic gut inflammation in TLR5-deficient mice. Cell Host Microbe. (2012) 12:139–52. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.07.004

63. Chassaing B, Koren O, Carvalho FA, Ley RE, and Gewirtz AT. AIEC pathobiont instigates chronic colitis in susceptible hosts by altering microbiota composition. Gut. (2014) 63:1069–80. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304909

64. Chassaing B, Ley RE, and Gewirtz AT. Intestinal epithelial cell toll-like receptor 5 regulates the intestinal microbiota to prevent low-grade inflammation and metabolic syndrome in mice. Gastroenterology. (2014) 147:1363–1377.e17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.033

65. Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Carvalho FA, Cullender TC, Mwangi S, Srinivasan S, et al. Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking toll-like receptor 5. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2010) 328:228–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1179721

66. Bouskra D, Brézillon C, Bérard M, Werts C, Varona R, Boneca IG, et al. Lymphoid tissue genesis induced by commensals through NOD1 regulates intestinal homeostasis. Nature. (2008) 456:507–10. doi: 10.1038/nature07450

67. Elinav E, Strowig T, Kau AL, Henao-Mejia J, Thaiss CA, Booth CJ, et al. NLRP6 inflammasome regulates colonic microbial ecology and risk for colitis. Cell. (2011) 145:745–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.022

68. Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, Jin C, Hao L, Mehal WZ, Strowig T, et al. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature. (2012) 482:179–85. doi: 10.1038/nature10809

69. Wlodarska M, Thaiss CA, Nowarski R, Henao-Mejia J, Zhang JP, Brown EM, et al. NLRP6 inflammasome orchestrates the colonic host-microbial interface by regulating goblet cell mucus secretion. Cell. (2014) 156:1045–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.026

70. Jakobsson HE, Rodríguez-Piñeiro AM, Schütte A, Ermund A, Boysen P, Bemark M, et al. The composition of the gut microbiota shapes the colon mucus barrier. EMBO Rep. (2015) 16:164–77. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439263

71. Salzman NH, Hung K, Haribhai D, Chu H, Karlsson-Sjöberg J, Amir E, et al. Enteric defensins are essential regulators of intestinal microbial ecology. Nat Immunol. (2010) 11:76–83. doi: 10.1038/ni.1825

72. Salzman NH and Bevins CL. Dysbiosis–a consequence of paneth cell dysfunction. Semin Immunol. (2013) 25:334–41. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.09.006

73. Vaishnava S, Yamamoto M, Severson KM, Ruhn KA, Yu X, Koren O, et al. The antibacterial lectin RegIIIgamma promotes the spatial segregation of microbiota and host in the intestine. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2011) 334:255–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1209791

74. Sommer F, Adam N, Johansson MEV, Xia L, Hansson GC, and Bäckhed F. Altered mucus glycosylation in core 1 O-glycan-deficient mice affects microbiota composition and intestinal architecture. PloS One. (2014) 9:e85254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085254

75. Zhang H, Sparks JB, Karyala SV, Settlage R, and Luo XM. Host adaptive immunity alters gut microbiota. ISME J. (2015) 9:770–81. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.165

76. Sutherland DB, Suzuki K, and Fagarasan S. Fostering of advanced mutualism with gut microbiota by immunoglobulin a. Immunol Rev. (2016) 270:20–31. doi: 10.1111/imr.12384

77. El Aidy S, Hooiveld G, Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F, and Kleerebezem M. The gut microbiota and mucosal homeostasis: colonized at birth or at adulthood, does it matter? Gut Microbes. (2013) 4:118–24. doi: 10.4161/gmic.23362

78. Qian LJ, Kang SM, Xie JL, Huang L, Wen Q, Fan YY, et al. Early-life gut microbial colonization shapes Th1/Th2 balance in asthma model in BALB/c mice. BMC Microbiol. (2017) 17:135. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-1044-0

79. Russell SL, Gold MJ, Hartmann M, Willing BP, Thorson L, Wlodarska M, et al. Early life antibiotic-driven changes in microbiota enhance susceptibility to allergic asthma. EMBO Rep. (2012) 13:440–7. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.32

80. Fujimura KE and Lynch SV. Microbiota in allergy and asthma and the emerging relationship with the gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. (2015) 17:592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.007

81. Omenetti S, Bussi C, Metidji A, Iseppon A, Lee S, Tolaini M, et al. The intestine harbors functionally distinct homeostatic tissue-resident and inflammatory Th17 cells. Immunity. (2019) 51:77–89.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.05.004

82. Wang Y, Yin Y, Chen X, Zhao Y, Wu Y, Li Y, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by flagellins from segmented filamentous bacteria. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:2750. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02750

83. Teng F, Felix KM, Bradley CP, Naskar D, Ma H, Raslan WA, et al. The impact of age and gut microbiota on Th17 and tfh cells in K/BxN autoimmune arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. (2017) 19:188. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1398-6

84. Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, Imaoka A, Kuwahara T, Momose Y, et al. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous clostridium species. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2011) 331:337–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469

85. Round JL, Lee SM, Li J, Tran G, Jabri B, Chatila TA, et al. The toll-like receptor 2 pathway establishes colonization by a commensal of the human microbiota. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2011) 332:974–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1206095

86. Kato LM, Kawamoto S, Maruya M, and Fagarasan S. The role of the adaptive immune system in regulation of gut microbiota. Immunol Rev. (2014) 260:67–75. doi: 10.1111/imr.12185

87. Kawamoto S, Maruya M, Kato LM, Suda W, Atarashi K, Doi Y, et al. Foxp3(+) T cells regulate immunoglobulin a selection and facilitate diversification of bacterial species responsible for immune homeostasis. Immunity. (2014) 41:152–65. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.016

88. Cong Y, Feng T, Fujihashi K, Schoeb TR, and dominant ECOA. coordinated T regulatory cell-IgA response to the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2009) 106:19256–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812681106

89. Hirota K, Turner JE, Villa M, Duarte JH, Demengeot J, Steinmetz OM, et al. Plasticity of Th17 cells in peyer’s patches is responsible for the induction of T cell-dependent IgA responses. Nat Immunol. (2013) 14:372–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.2552

90. Tsuji M, Komatsu N, Kawamoto S, Suzuki K, Kanagawa O, Honjo T, et al. Preferential generation of follicular B helper T cells from Foxp3+ T cells in gut peyer’s patches. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2009) 323:1488–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1169152

91. Klaasen HL, van der Heijden PJ, Stok W, Poelma FG, Koopman JP, Van den Brink ME, et al. Apathogenic, intestinal, segmented, filamentous bacteria stimulate the mucosal immune system of mice. Infection Immun. (1993) 61:303–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.303-306.1993

92. Talham GL, Jiang HQ, Bos NA, and Cebra JJ. Segmented filamentous bacteria are potent stimuli of a physiologically normal state of the murine gut mucosal immune system. Infection Immun. (1999) 67:1992–2000. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.4.1992-2000.1999

93. Fagarasan S, Muramatsu M, Suzuki K, Nagaoka H, Hiai H, and Honjo T. Critical roles of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in the homeostasis of gut flora. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2002) 298:1424–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1077336

94. Suzuki K, Meek B, Doi Y, Muramatsu M, Chiba T, Honjo T, et al. Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA-deficient gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2004) 101:1981–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307317101

95. Cullender TC, Chassaing B, Janzon A, Kumar K, Muller CE, Werner JJ, et al. Innate and adaptive immunity interact to quench microbiome flagellar motility in the gut. Cell Host Microbe. (2013) 14:571–81. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.10.009

96. Kawamoto S, Tran TH, Maruya M, Suzuki K, Doi Y, Tsutsui Y, et al. The inhibitory receptor PD-1 regulates IgA selection and bacterial composition in the gut. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2012) 336:485–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1217718

97. Kubinak JL, Petersen C, Stephens WZ, Soto R, Bake E, O’Connell RM, et al. MyD88 signaling in T cells directs IgA-mediated control of the microbiota to promote health. Cell Host Microbe. (2015) 17:153–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.12.009

98. Maruya M, Kawamoto S, Kato LM, and Fagarasan S. Impaired selection of IgA and intestinal dysbiosis associated with PD-1-deficiency. Gut Microbes. (2013) 4:165–71. doi: 10.4161/gmic.23595

99. Planchais C, Molinos-Albert LM, Rosenbaum P, Hieu T, Kanyavuz A, Clermont D, et al. HIV-1 treatment timing shapes the human intestinal memory B-cell repertoire to commensal bacteria. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:6326. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42027-6

100. Bauer H, Horowitz RE, Levenson SM, and Popper H. The response of the lymphatic tissue to the microbial flora. Studies on germfree mice. Am J Pathol. (1963) 42:471–83.

101. Crabbé PA, Bazin H, Eyssen H, and Heremans JF. The normal microbial flora as a major stimulus for proliferation of plasma cells synthesizing IgA in the gut. The germ-free intestinal tract. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. (1968) 34:362–75. doi: 10.1159/000230130

102. Durkin HG, Bazin H, and Waksman BH. Origin and fate of IgE-bearing lymphocytes. I. Peyer’s patches as differentiation site of cells. Simultaneously bearing IgA and IgE. J Exp Med. (1981) 154:640–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.154.3.640

103. Hooijkaas H, Benner R, Pleasants JR, and Wostmann BS. Isotypes and specificities of immunoglobulins produced by germ-free mice fed chemically defined ultrafiltered A’ntigen-free’ diet. Eur J Immunol. (1984) 14:1127–30. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830141212

104. Li H, Limenitakis JP, Greiff V, Yilmaz B, Schären O, Urbaniak C, et al. Mucosal or systemic microbiota exposures shape the B cell repertoire. Nature. (2020) 584:274–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2564-6

105. Konjar Š, Ferreira C, Blankenhaus B, and Veldhoen M. Intestinal barrier interactions with specialized CD8 T cells. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:1281. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01281

106. Campbell C, Kandalgaonkar MR, Golonka RM, Yeoh BS, Vijay-Kumar M, and Saha P. Crosstalk between gut microbiota and host immunity: impact on inflammation and immunotherapy. Biomedicines. (2023) 11:294. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11020294

107. Wakao H, Kawamoto H, Sakata S, Inoue K, Ogura A, Wakao R, et al. A novel mouse model for invariant NKT cell study. J Immunol (baltimore Md.: 1950). (2007) 179:3888–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3888

108. Yoo JY, Groer M, Dutra SVO, Sarkar A, and McSkimming DI. Gut microbiota and immune system interactions. Microorganisms. (2020) 8:1587. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8101587

109. Kamali AN, Noorbakhsh SM, Hamedifar H, Jadidi-Niaragh F, Yazdani R, Bautista JM, et al. A role for Th1-like Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune disorders. Mol Immunol. (2019) 105:107–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2018.11.015

110. Raphael I, Nalawade S, Eagar TN, and Forsthuber TG. T cell subsets and their signature cytokines in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Cytokine. (2015) 74:5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.09.011

111. Maciel-Fiuza MF, Muller GC, Campos DMS, do Socorro Silva Costa P, Peruzzo J, Bonamigo RR, et al. Role of gut microbiota in infectious and inflammatory diseases. Front Microbiol. (2023) 14:1098386. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1098386

112. Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2015) 12:720–7. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.150

113. Barbara G, Barbaro MR, Fuschi D, Palombo M, Falangone F, Cremon C, et al. Inflammatory and microbiota-related regulation of the intestinal epithelial barrier. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:718356. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.718356

114. Bautzova T, Hockley JRF, Perez-Berezo T, Pujo J, Tranter MM, Desormeaux C, et al. 5-oxoETE triggers nociception in constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome through MAS-related G protein-coupled receptor D. Sci Signaling. (2018) 11:eaal2171. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aal2171

115. Xu H, Liu M, Cao J, Li X, Fan D, Xia Y, et al. The dynamic interplay between the gut microbiota and autoimmune diseases. J Immunol Res. (2019) 2019:7546047. doi: 10.1155/2019/7546047

116. Gevers D, Kugathasan S, Denson LA, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Van Treuren W, Ren B, et al. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe. (2014) 15:382–92. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.005

117. Kostic AD, Xavier RJ, and Gevers D. The microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease: current status and the future ahead. Gastroenterology. (2014) 146:1489–99. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.009

118. Franzosa EA, Sirota-Madi A, Avila-Pacheco J, Fornelos N, Haiser HJ, Reinker S, et al. Gut microbiome structure and metabolic activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol. (2019) 4:293–305. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0306-4

119. Lloyd-Price J, Arze C, Ananthakrishnan AN, Schirmer M, Avila-Pacheco J, Poon TW, et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature. (2019) 569:655–62. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1237-9

120. Landy J, Ronde E, English N, Clark SK, Hart AL, Knight SC, et al. Tight junctions in inflammatory bowel diseases and inflammatory bowel disease associated colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. (2016) 22:3117–26. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i11.3117

121. Van der Sluis M, De Koning BAE, De Bruijn ACJM, Velcich A, Meijerink JPP, Van Goudoever JB, et al. Muc2-deficient mice spontaneously develop colitis, indicating that MUC2 is critical for colonic protection. Gastroenterology. (2006) 131:117–29. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.020

122. Noble AJ, Nowak JK, Adams AT, Uhlig HH, and Satsangi J. Defining interactions between the genome, epigenome, and the environment in inflammatory bowel disease: progress and prospects. Gastroenterology. (2023) 165:44–60.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.03.238

123. Hampe J, Cuthbert A, Croucher PJ, Mirza MM, Mascheretti S, Fisher S, et al. Association between insertion mutation in NOD2 gene and crohn’s disease in german and british populations. Lancet (london England). (9272) 2001:357. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05063-7

124. Al Nabhani Z, Dietrich G, Hugot JP, and Barreau F. Nod2: the intestinal gate keeper. PloS Pathog. (2017) 13:e1006177. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006177

125. Rehman A, Sina C, Gavrilova O, Häsler R, Ott S, Baines JF, et al. Nod2 is essential for temporal development of intestinal microbial communities. Gut. (2011) 60:1354–62. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.216259

126. Okolie MC, Edo GI, Ainyanbhor IE, Jikah AN, Akpoghelie PO, Yousif E, et al. Gut microbiota and immunity in health and diseases: a review. Proc Indian Natl Sci Acad. (2024) 91: 397–414. doi: 10.1007/s43538-024-00355-1

127. Aden K, Tran F, Ito G, Sheibani-Tezerji R, Lipinski S, Kuiper JW, et al. ATG16L1 orchestrates interleukin-22 signaling in the intestinal epithelium via cGAS-STING. J Exp Med. (2018) 215:2868–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171029

128. Cadwell K, Patel KK, Komatsu M, Virgin HW, and Stappenbeck TS. A common role for Atg16L1, Atg5 and Atg7 in small intestinal paneth cells and crohn disease. Autophagy. (2009) 5:250–2. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.2.7560

129. Levy M, Thaiss CA, Zeevi D, Dohnalová L, Zilberman-Schapira G, Mahdi JA, et al. Microbiota-modulated metabolites shape the intestinal microenvironment by regulating NLRP6 inflammasome signaling. Cell. (2015) 163:1428–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.048

130. Geremia A, Biancheri P, Allan P, Corazza GR, and Di Sabatino A. Innate and adaptive immunity in inflammatory bowel disease. Autoimmun Rev. (2014) 13:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.06.004

131. Schaubeck M, Clavel T, Calasan J, Lagkouvardos I, Haange SB, Jehmlich N, et al. Dysbiotic gut microbiota causes transmissible crohn’s disease-like ileitis independent of failure in antimicrobial defence. Gut. (2016) 65:225–37. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309333

132. Britton GJ, Contijoch EJ, Spindler MP, Aggarwala V, Dogan B, Bongers G, et al. Defined microbiota transplant restores Th17/RORγt+ regulatory T cell balance in mice colonized with inflammatory bowel disease microbiotas. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2020) 117:21536–45. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1922189117

133. Caruso R, Mathes T, Martens EC, Kamada N, Nusrat A, Inohara N, et al. A specific gene-microbe interaction drives the development of crohn’s disease-like colitis in mice. Sci Immunol. (2019) 4:eaaw4341. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaw4341

134. Qi Y, Wu HM, Yang Z, Zhou YF, Jin L, Yang MF, et al. New insights into the role of oral microbiota dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Digestive Dis Sci. (2022) 67:42–55. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-06837-2

135. Kobayashi KS, Chamaillard M, Ogura Y, Henegariu O, Inohara N, Nuñez G, et al. Nod2-dependent regulation of innate and adaptive immunity in the intestinal tract. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2005) 307:731–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1104911

136. Vaishnava S, Behrendt CL, Ismail AS, Eckmann L, and Hooper LV. Paneth cells directly sense gut commensals and maintain homeostasis at the intestinal host-microbial interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2008) 105:20858–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808723105

137. Satoh-Takayama N, Vosshenrich CAJ, Lesjean-Pottier S, Sawa S, Lochner M, Rattis F, et al. Microbial flora drives interleukin 22 production in intestinal NKp46+ cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity. (2008) 29:958–70. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.001

138. Zheng Y, Valdez PA, Danilenko DM, Hu Y, Sa SM, Gong Q, et al. Interleukin-22 mediates early host defense against attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat Med. (2008) 14:282–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1720

139. Kiss EA, Vonarbourg C, Kopfmann S, Hobeika E, Finke D, Esser C, et al. Natural aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands control organogenesis of intestinal lymphoid follicles. Sci (new York N.Y.). (2011) 334:1561–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1214914

140. Qiu J, Heller JJ, Guo X, Chen Z ming E, Fish K, Fu YX, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates gut immunity through modulation of innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. (2012) 36:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.011

141. Fagarasan S, Kawamoto S, Kanagawa O, and Suzuki K. Adaptive immune regulation in the gut: T cell-dependent and T cell-independent IgA synthesis. Annu Rev Immunol. (2010) 28:243–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101314

142. Frantz AL, Rogier EW, Weber CR, Shen L, Cohen DA, Fenton LA, et al. Targeted deletion of MyD88 in intestinal epithelial cells results in compromised antibacterial immunity associated with downregulation of polymeric immunoglobulin receptor, mucin-2, and antibacterial peptides. Mucosal Immunol. (2012) 5:501–12. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.23

143. Suzuki K, Maruya M, Kawamoto S, Sitnik K, Kitamura H, Agace WW, et al. The sensing of environmental stimuli by follicular dendritic cells promotes immunoglobulin a generation in the gut. Immunity. (2010) 33:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.003

144. Franchi L, Kamada N, Nakamura Y, Burberry A, Kuffa P, Suzuki S, et al. NLRC4-driven production of IL-1β discriminates between pathogenic and commensal bacteria and promotes host intestinal defense. Nat Immunol. (2012) 13:449–56. doi: 10.1038/ni.2263

145. Almonajjed MB, Wardeh M, Atlagh A, Ismaiel A, Popa SL, Rusu F, et al. Impact of microbiota on irritable bowel syndrome pathogenesis and management: a narrative review. Medicina. (2025) 61:109. doi: 10.3390/medicina61010109

146. Barbara G, Grover M, Bercik P, Corsetti M, Ghoshal UC, Ohman L, et al. Rome foundation working team report on post-infection irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. (2019) 156:46–58.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.011

147. Berumen A, Edwinson AL, and Grover M. Post-infection irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clinics North America. (2021) 50:445–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2021.02.007

148. Dicksved J, Ellström P, Engstrand L, and Rautelin H. Susceptibility to campylobacter infection is associated with the species composition of the human fecal microbiota. Mbio. (2014) 5:e01212–1214. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01212-14

149. Jeffery IB, Quigley EMM, Öhman L, Simrén M, and O’Toole PW. The microbiota link to irritable bowel syndrome: an emerging story. Gut Microbes. (2012) 3:572–6. doi: 10.4161/gmic.21772

150. El-Salhy M, Hatlebakk JG, and Hausken T. Possible role of peptide YY (PYY) in the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Neuropeptides. (2020) 79:101973. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2019.101973

151. Kim HS, Lim JH, Park H, and Lee SI. Increased immunoendocrine cells in intestinal mucosa of postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome patients 3 years after acute shigella infection–an observation in a small case control study. Yonsei Med J. (2010) 51:45–51. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.1.45