- 1College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Hubei University of Chinese Medicine, Wuhan, China

- 2First Clinical Medical College, Anhui University of Chinese Medicine, Hefei, China

- 3Rehabilitation Department, Hubei Provincial Hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine, Wuhan, China

- 4Digestive System Department, Wuhan Hospital of Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, Wuhan, China

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a globally prevalent metabolic disorder with a high average worldwide prevalence. It occurs more frequently in men than in women, and its incidence increases with age. MASLD can progressively advance to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and even hepatocellular carcinoma, while also elevating the risk of cardiovascular, renal, and other systemic diseases. Its pathological progression is closely associated with dysregulation of the hepatic immune microenvironment, in which aberrant crosstalk between Macrophages (Mø) and regulatory T cells (Tregs) serves as a central driving mechanism. Under physiological conditions, liver-resident Macrophages (Kupffer cells, KCs) and Tregs maintain immune homeostasis through a “complementary origin–spatial co-localization-molecular crosstalk” mechanism. In MASLD, KCs numbers decline while monocyte-derived Macrophages (MDMs) are abnormally recruited, giving rise to Macrophages with distinct phenotypes. Tregs influence the classical phenotypic differentiation of Macrophages. However, dynamic alterations in Treg abundance exhibit a “double-edged sword” effect. The disrupted crosstalk between KCs and Tregs involves dysregulated chemokine networks [e.g., c-x-c motif chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9), c-c motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2)], cytokine interactions [e.g., interleukin-1β (IL-1β), transforming growth factor- Beta (TGF-β)], and signaling pathways such as beta-catenin (β-catenin) and notch homolog 1 (Notch1). Collectively, these alterations drive disease progression from steatosis to hepatitis and fibrosis. This review systematically summarizes the physiological mechanisms underlying Macrophages -Tregs crosstalk, its pathological dysregulation in MASLD, and the associated molecular networks, while proposing targeted therapeutic strategies based on disease stage.

1 Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a form of metabolic liver disease characterized by hepatic steatosis that occurs in the absence of other specific liver disorders, though it may coexist with alcohol consumption. It has emerged as a major global health concern (1). In 2020, an international expert panel representing 22 countries officially renamed non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) as MASLD (2), emphasizing the central role of metabolic dysfunction in its pathogenesis (2). As global dietary patterns and socioeconomic conditions evolve, MASLD increasingly coexists with metabolic comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes, with its prevalence rising in parallel with these disorders (3). Epidemiological studies report a global average MASLD prevalence of approximately 30% (4), with regional variations: 17.31% in high-income regions (5), 32.45% in the United States (6), and 36.7% in China (7). The disease also exhibits demographic variation, with higher incidence in males than females and a notable age-related increase in prevalence (7, 8). Pathologically, MASLD progression involves hepatic metabolic derangements and chronic inflammatory responses. In severe cases, it may advance to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), liver fibrosis, and cirrhosis (9), potentially progressing to end-stage liver diseases such as MASLD-related hepatocellular carcinoma (1). These complications impose substantial burdens on both patient health and healthcare systems (4, 10). Furthermore, MASLD significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular and renal diseases (11, 12).

Maintenance of hepatic immune homeostasis relies heavily on the precise crosstalk between Macrophages and regulatory T cells (Tregs), and the disruption of this balance represents a key mechanism driving MASLD progression (13). Chronic inflammation is a major driver of MASLD advancement, primarily mediated by Macrophages and Tregs (14). Experimental studies have shown that, under physiological conditions, liver-resident Macrophages recognize pathogens to initiate innate immune defense, rapidly phagocytose foreign substances, and secrete cytokines as early warning signals (15–18), and this phenomenon is observed in both humans and animals (19). In mice, Tregs, in turn, sense inflammatory cues within the hepatic microenvironment through surface receptors and secreted cytokines, thereby constraining the excessive activation of effector T cells (20–22). In this “sensing-constraint” model, the delicate quantitative balance between the two classical Macrophages phenotypes (M1/M2: pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory) forms the basis for immune stability (23). However, in MASLD, this equilibrium is disrupted, leading to “bidirectional dysregulation.” On one hand, studies in MASLD mouse models show that Kupffer cells (KCs) numbers decline while monocyte-derived Macrophages (MDMs) are increasingly recruited (24, 25), a phenomenon that may also occur in humans (24). As Macrophages undergo phenotypic switching in response to environmental signals, their cytokine secretion patterns influence Tregs differentiation (13). Conversely, the expanding Tregs population exhibits dual, context-dependent effects (26). For example, in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mice, increased hepatic Tregs alter Macrophages phenotype and function through multiple pathways (27). This dynamic transition from “homeostatic regulation” to “pathological drive” represents a critical mechanistic question that warrants further investigation in MASLD research.

As a globally prevalent chronic liver disease, MASLD progression is tightly linked to aberrant Macrophages-Tregs crosstalk. Previous studies have primarily examined Macrophages and Tregs individually, while the integrated mechanisms underlying their dynamic interaction during disease progression remain insufficiently characterized. This review systematically elucidates the biological basis of Macrophages-Tregs communication, highlights its pathological alterations in MASLD, and analyzes the underlying regulatory networks. We further propose stage-specific therapeutic strategies to advance understanding of MASLD pathogenesis and provide conceptual frameworks for both basic and translational research.

2 Physiological basis for macrophages-tregs crosstalk in the hepatic microenvironment

Under physiological conditions, hepatic immune homeostasis is maintained through a three-dimensional framework of “source complementarity-spatial co-localization-molecular interaction” between Macrophages and Tregs. These three layers function in a logically sequential and mutually reinforcing manner, forming a highly efficient immunoregulatory system.

2.1 Complementarity of origin and differentiation: homeostatic maintenance of cellular reservoirs

Macrophages and Tregs display pronounced complementarity in their cellular origins, ensuring both stability and functional diversity of the hepatic immune cell reservoir. KCs, the specialized liver-resident Macrophages, are constitutively localized within hepatic sinusoids, where they adhere to the surface of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs). KCs origin involves two major sources. First, KCs primarily derive from yolk sac-specific progenitor cells during embryonic development, which colonize liver tissue and maintain population stability throughout life via self-renewal (28, 29). This “yolk sac origin-embryonic colonization-self-renewal” mechanism is highly conserved across mammals, including humans (30). Functionally, KCs serve as immune sentinels: in mice, they phagocytose foreign particles (31), while in human primary hepatic cells, they secrete anti-inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), thereby establishing the liver’s immunotolerant microenvironment (32, 33). Second, animal studies have shown that differentiation of bone marrow-derived MDMs—a process tightly regulated by local microenvironmental factors such as Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor—is minimal under physiological conditions, forming a KCs reservoir. Differentiated MDMs exhibit strong expression of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) activation-related pathways, maintain a proliferation index below 0.3% per week, and directly limit excessive expansion (34).

The tissue-resident Tregs populations in the liver are predominantly localized within the hepatic parenchyma and interstitial compartments (35). Under physiological conditions, Tregs utilize cytotoxic t-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) to competitively bind CD80/CD86 on LSECs, thereby preventing effector T cells from engaging these co-stimulatory ligands. This suppresses excessive effector T-cells activation, maintains local immune tolerance, and preserves hepatic immune homeostasis (35). Another subset of Tregs originates in the thymus. Following maturation, these cells enter the periphery as naive CD4+ T cells, which can differentiate into induced Tregs (iTregs) under the influence of the hepatic microenvironment (20, 27). The defining CD4+CD25+ fork head box p3 (FoxP3+) signature characterizes Tregs. Specifically, iTregs arise from naive CD4+ T cells through TGF-β-dependent differentiation, a process notably mediated by LSECs in the liver. These iTregs stably express FoxP3 yet retain numerical and functional plasticity, allowing adaptation to dynamic inflammatory cues (36).

The dual-origin paradigms of Macrophages—derived primarily from embryonic progenitors with bone-marrow supplementation—and Tregs—arising from both thymic derivation and peripheral induction—together establish a functionally complementary immune cell reservoir. This foundation provides the basis for their subsequent spatial co-localization and molecular interactions.

2.2 Spatial co-localization of macrophages and tregs: the foundation for precision crosstalk in the immune microenvironment

Building upon the stable cell pools formed through complementary origins, Macrophages and Tregs achieve spatial co-localization via chemokine-mediated regulation, establishing the physical conditions necessary for direct molecular interaction and functional synergy.

As liver-resident Macrophages, KCs are primarily located within hepatic sinusoids (HS) and adhere to LSECs. Tregs, by contrast, are concentrated in periportal regions and adjacent sinusoidal areas, displaying marked spatial overlap with KCs distribution patterns (37). This proximity enables their functional cooperation. Within this compartmentalized architecture, the HS, as key conduits for metabolic and immune exchange, are particularly susceptible to exposure from gut-derived antigens and metabolic stimuli. Under physiological conditions, KCs rapidly sense circulating exogenous molecules, such as microbial antigens from the gut, and initiate innate immune defense through efficient antigen capture (37). Tregs situated near KCs respond to these antigenic cues by secreting IL-10, thereby modulating local immune activation. Upon antigen uptake, KCs further promote the activation and expansion of antigen-specific Tregs. These activated Tregs, in turn, suppress the overactivation of KCs and MDMs, preventing excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This sequential process—antigen capture by KCs, activation of Tregs, and reciprocal regulation of Macrophages—constitutes a central mechanism by which the liver filters gut-derived antigens and protects the parenchyma from Macrophages-mediated injury (38). The periportal region functions as a critical immune hub, facilitating the recruitment of diverse immune cells. Here, the co-localization of MDMs, Tregs, and KCs collaboratively filters gut-derived antigens, mitigating chronic inflammation driven by the gut-liver axis (39). Even under pathological conditions, Tregs retain their protective function: by restraining immune intensity, they prevent secondary hepatic injury caused by excessive Macrophages activation (40). This compartmentalized collaboration, modulated by cytokines, chemokines, and metabolites, establishes a dynamic and context-dependent framework for immune cell interactions within the liver (20).

2.3 Molecular crosstalk between macrophages and tregs: from homeostatic collaboration to pathological disruption

Spatially co-localized Macrophages and Tregs execute the core functions of the “source complementarity–spatial co-localization–molecular interaction” framework through both direct intercellular binding and cytokine-mediated regulation, enabling precise and adaptable molecular crosstalk.

First, animal experiments have confirmed that direct molecular interactions potentiate immunosuppressive signaling. In pathological states, programmed death-1(PD-1) expressed on hepatic Tregs binds programmed death-ligand 1(PD-L1) on Macrophages, directly enhancing the immunosuppressive activity of Tregs. This interaction suppresses effector T-cell overactivation and helps preserve hepatic immune tolerance (41, 42). Additionally, antigen-specific interactions between Tregs and antigen-presenting cells (APCs)—where Treg T-cell receptors (TCRs) engage major histocompatibility complex class II(MHC-II) molecules on APCs—are essential for the targeted differentiation and activation of Tregs (43). Second, cytokine-mediated indirect regulation serves to balance the immune response. The co-secretion of IL-10 by Tregs and KCs generates a synergistic anti-inflammatory signal that protects hepatic tissue (44). Furthermore, the high-affinity interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor α-chain (CD25) on Tregs competitively binds IL-2 in the hepatic microenvironment, depriving effector T cells of this critical proliferative signal and thereby inhibiting their expansion and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). Conversely, Macrophages secrete IL-2 and TGF-β to promote Tregs differentiation (41, 45). The maintenance of the anti-inflammatory phenotype of KCs is supported by the regulatory activity of other APCs. KCs sustain an M2-polarized state through toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling, which suppresses pro-inflammatory mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathways while upregulating anti-inflammatory mediators including TGF-β and IL-10 (41, 42, 45). Additionally, LSECs autonomously secrete TGF-β, thereby serving as key regulators of Tregs differentiation and function (36).

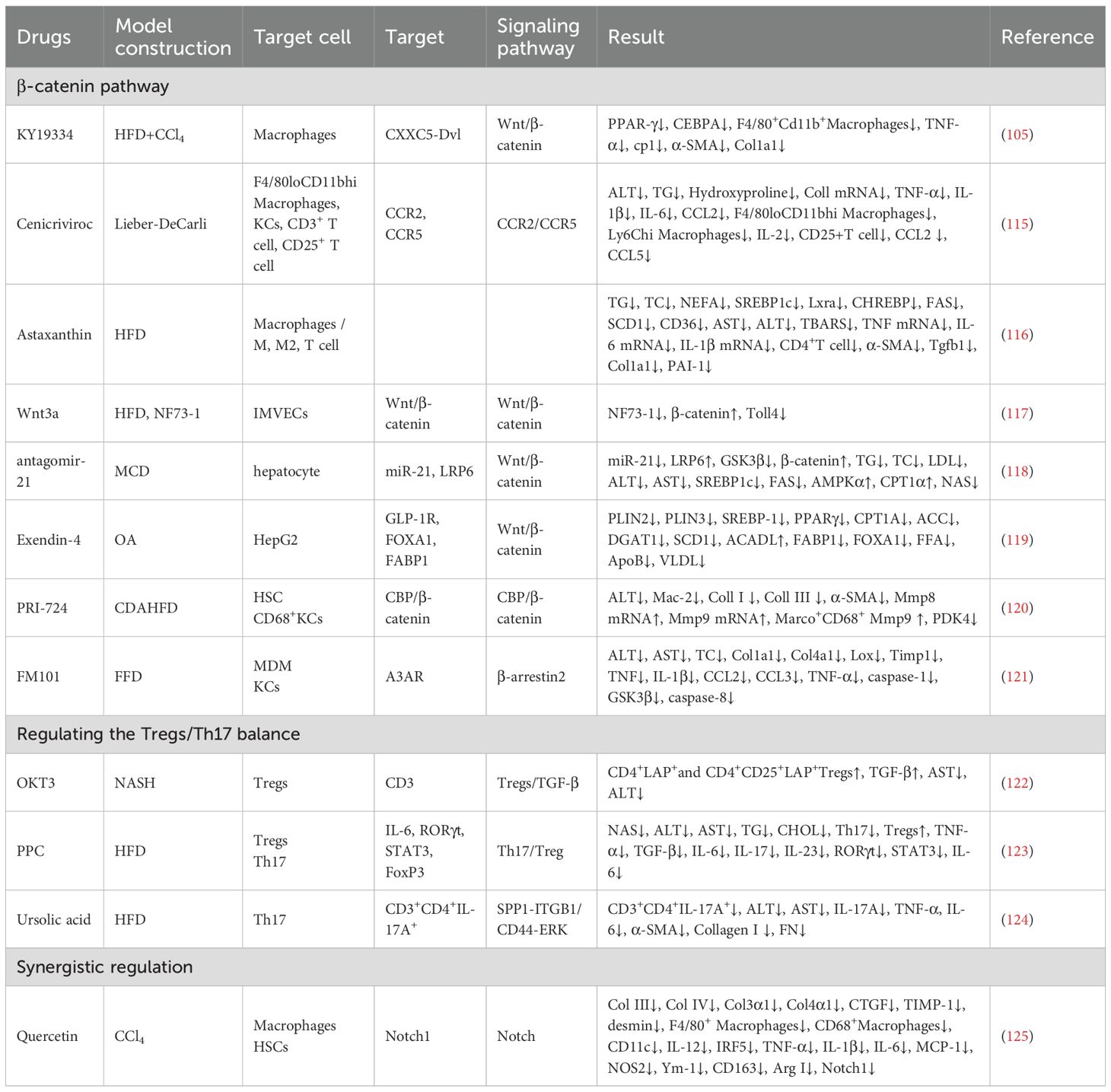

However, disturbances in metabolic, oxidative, and intestinal homeostasis can disrupt KCs-Tregs communication. Such dysregulation leads to pro-inflammatory MDMs infiltration and dysfunctional Tregs expansion, converting a homeostatic regulatory circuit into a pathological driver of inflammation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Spatial colocalization and molecular interactions between Macrophages and Tregs in the liver.

3 Initiation of crosstalk imbalance in MASLD

3.1 KCs depletion and MDMs infiltration: early signals of crosstalk imbalance

In MASLD, the “source complementarity–spatial co-localization–molecular interaction” framework becomes progressively dysregulated. This cascade, from the destabilization of cellular reservoirs to disordered spatial localization and aberrant molecular communication, shifts Macrophages-Tregs crosstalk from homeostatic regulation to pathological activation.

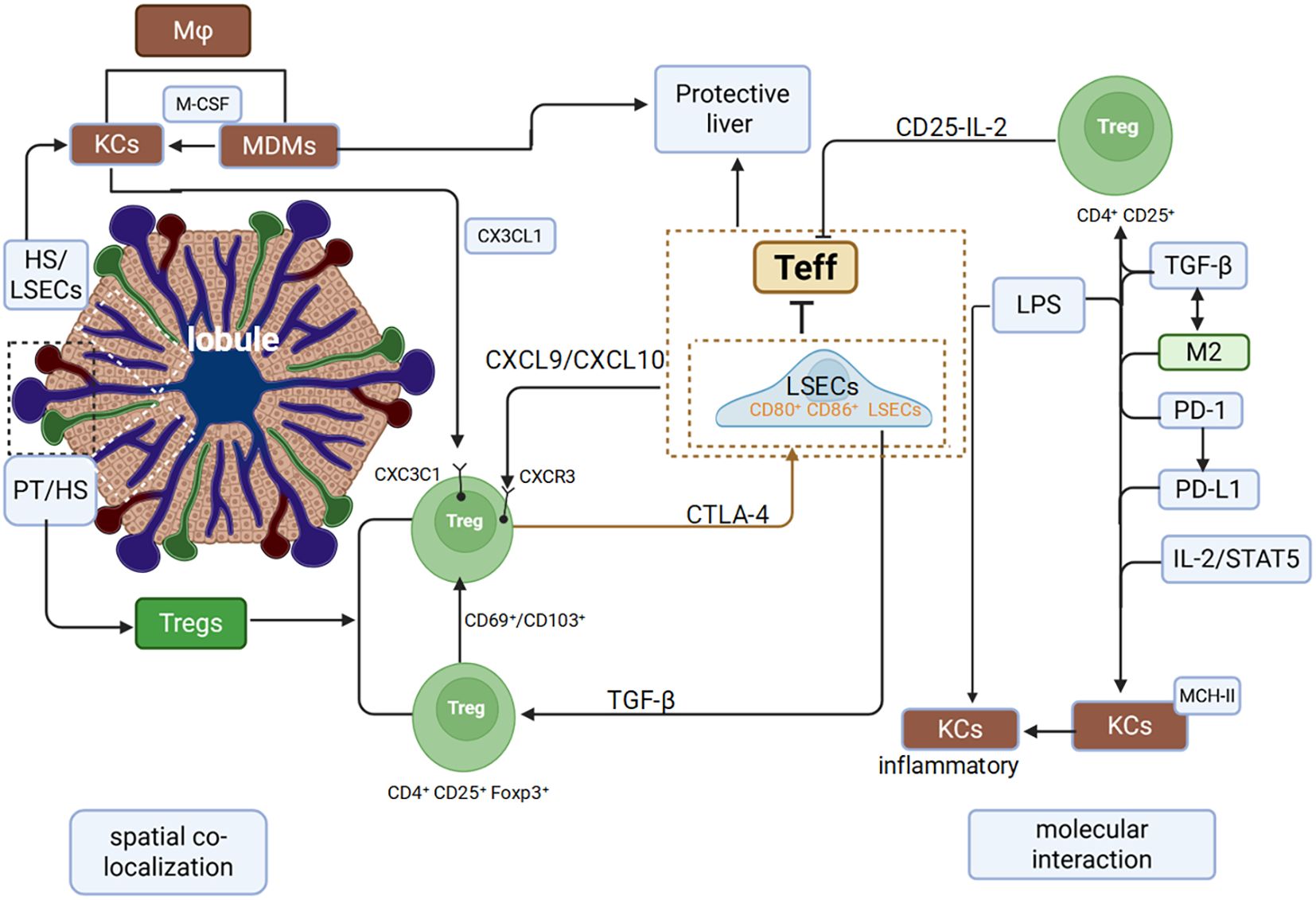

KCs depletion promotes MDMs recruitment and impairs KCs-Tregs anti-inflammatory coordination, thereby initiating the disruption of immunological crosstalk (46). The core mechanism of MDMs recruitment involves hepatic infiltration of circulating monocytes followed by their differentiation into phenotypically distinct Macrophages. In MASLD mouse models, depletion of c-type lectin domain family 4, member f (Clec4F+) T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin domain-containing protein 4 (Tim4+) KCs and expansion of MDMs subsets, including Clec4F–Tim4– and Clec4F+Tim4– populations resembling KCs, are observed. This phenomenon correlates with elevated Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-2 Alpha (HIF-2α) expression in KCs during Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH). HIF-2α activation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathways induces TFEB phosphorylation, impairing KC phagocytic and efferocytotic functions and promoting apoptosis, as reflected by increased active caspase-3+ KCs (24, 25). Consequently, MDMs gradually become the predominant hepatic Macrophages population in MASLD (47). (Figure 2a).

Figure 2. Macrophages and Tregs interact with each other in MASLD (a) Reduction in KCs. (b) Chemokine-mediated crosstalk between Macrophages and Tregs. (c) The phenotype and classical phenotypic differentiation of Macrophages are influenced by Tregs. (d) Dual roles of Tregs.

Disruption of the embryonic origin stability of KCs and aberrant recruitment of MDMs directly undermine the cellular reservoir equilibrium central to the “source complementarity” framework.

3.2 Reciprocal regulation between macrophages and tregs recruitment

Following the imbalance in cellular origins, the nature of intercellular interactions also undergoes significant alteration. Cross-regulatory chemotactic signaling orchestrates the recruitment of MDMs and Tregs, synergistically reshaping the inflammatory microenvironment. A key mechanism driving the early progression from MASLD to metabolic-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) in mice involves the release of high mobility group box 1(HMGB1) from injured hepatocytes. By binding to TLR4 on KCs, HMGB1 activates the TLR4/ myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88)/NF-κB pathway, leading to KCs activation and the subsequent production of CCL2, with potential modulation of c-c motif chemokine ligand 3 (CCL3) and c-x-c motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8). This chemokine milieu mediates the recruitment of Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes and neutrophils, thereby initiating and sustaining NAFLD-associated inflammation (48–51). C-c motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) directly promotes the recruitment of MDMs, including the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (Trem2+) subset, through interaction with c-c motif chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) on Ly6C+ monocytes, while c-c motif chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5) acts synergistically with c-c motif chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) in this process (52, 53). Additionally, IFN-γ-activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) express c-x3-c motif chemokine ligand 1 (CX3CL1), which undergoes proteolytic cleavage into a soluble form that binds to c-x3-c motif chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1) on monocytes, further enhancing MDMs recruitment (54). Conversely, genetic ablation of CCL2 or pharmacological blockade of CCR2/CCR5 provides reverse evidence supporting the critical role of this chemokine axis in Macrophages recruitment (52) (55).

CXCL9 and c-x-c motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) secreted by LSECs guide the migration of peripheral CD4+ T cells into the liver through CXCR3, where they differentiate into Tregs under TGF-β induction. Notably, monokine induced by gamma interferon (MIG)/CXCL9 downregulates CXCR3 expression on Tregs to fine-tune their immunosuppressive activity (56). Moreover, CCL2 derived from group type 1 innate lymphoid cell (ILC1s) not only recruits Tregs (40), but also establishes a feedback loop in which Treg-secreted IL-10 stimulates further chemokine production by immune cells (36), thereby establishing a regulatory circuit (Figure 2b).

3.3 Macrophages phenotypic differentiation and the regulatory role of tregs

3.3.1 The phenotypic spectrum of macrophages in MASLD

In MASLD, Macrophages differentiation displays marked heterogeneity and dynamic plasticity. Firstly, it is the dual abnormality of the decrease in the number of KCs and their functional impairment. Under normal conditions, KCs express high levels of the markers CLEC4F, TIM4, and cluster of differentiation 163 (CD163). However, in MASLD mice, the number of TIM4+CD163+ KCs decreases significantly (57). Treatment with bisphosphonates depletes KCs, although resident KCs retaining phenotypic markers, along with CD68+ Macrophages, remain less affected. Concomitantly, mRNA levels of KCs-associated pro-inflammatory chemokines, including CCL2 and TNF-α, are significantly upregulated. These findings indicate that KCs numbers are reduced and that a subset of remaining KCs actively contributes to the pro-inflammatory process (58).

Secondly, there are changes in MDMs. They differentiate into pro-inflammatory MDMs in the early stage. When KCs depletion occurs, the number of TIM4–CCR2+ MDMs derived from Ly6C+ monocytes increases (57), with these MDMs distributed within the space of Disse and around the central vein. Ly6C+ Macrophages can further differentiate into short-lived Clec4e+ pro-inflammatory Macrophages (59). In MASLD mice, both lipid-associated Macrophages (LAMs) and monocyte-derived KCs (MoKCs) are markedly increased (60). In the early stages of MASLD, CLEC2+CLEC4F– precursor MoKCs (pre-MoKCs) are recruited, expressing CX3CR1 and later differentiating into MoKCs that primarily localize within hepatic sinusoids (61). LAMs exhibit pro-inflammatory properties in the early stage and pro-fibrotic properties in the late stage. In mice fed HFD diet, hepatic F4/80hiCD11b1nTIM4− CX3CR1-high LAMs are early-recruited subsets that express high levels of CX3CR1, CCR2, and Trem2 but low levels of CD63 and glycoprotein non-metastatic melanoma protein b (Gpnmb). Conversely, LAMs with low CX3CR1/CCR2 expression and high Trem2, CD63, Gpnmb, and secreted phosphoprotein 1 (Spp1) expression preferentially accumulate in HSC-activated regions, promoting the progression of liver fibrosis (47). Analysis of human clinical samples further reveals that the proportion of M1 Macrophages (CD86+, TNF-α+) is increased, whereas M2 Macrophages (CD206+) are reduced in MASLD patients (62).

Therefore, the differentiation of macrophages in MASLD is a complex process involving ldquo;KCs functional dissociation - MDMs subset specialization - dynamic functional transition (59, 63), and their phenotypes and functions exhibit high heterogeneity and plasticity.

3.3.2 Classical phenotypic differentiation of macrophages and its regulation by tregs

M1 Macrophages are closely associated with the initiation of inflammation (64). Under stimulation by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and IFN-γ, Macrophages polarize toward the M1 phenotype, secreting pro-inflammatory mediators such as Interleukin-1 Beta (IL-1β), TNF-α, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), while activating the TLR4/NF-κB and janus kinase (JAK) /signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) signaling pathways (65). During early steatosis, lipid-laden hepatocytes release free fatty acids (FFAs) as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which activate the NF-κB pathway through the TLR4/ myeloid differentiation 2 (MD-2) /Cluster of Differentiation 14 (CD14) complex on Macrophages, inducing pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and promoting the differentiation of MDMs into M1 Macrophages (66–68). Studies using primary human hepatocytes show that BMP9 overexpression in NASH upregulates TLR4 expression on Macrophages surfaces (69). Sustained accumulation of M1 Macrophages in the human liver drives inflammation, disrupts lipid metabolism, and promotes hepatic fibrosis, thereby accelerating NASH progression (70). Tregs antagonize the pro-inflammatory activity of M1 Macrophages through multiple mechanisms. Animal studies have demonstrated that, in MASLD mice modeled with CCL2, hepatic Tregs directly inhibit M1 Macrophages activation via IL-10 secretion (40). Conversely, depletion of Tregs results in a significant increase in hepatic M1 Macrophages, further supporting their suppressive role (71).

In the MASLD liver, Tregs also promote Macrophages polarization toward the M2 phenotype. Upon liver injury, TGF-β secreted by Tregs suppresses Macrophages-derived pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-1β (72), while IL-10 from Tregs directly facilitates the M1-to-M2 phenotypic switch (40). M2 Macrophages polarization is further induced by IL-4 and IL-13 (73) through activation of the JAK/STAT6 signaling pathway (65, 74). The IL-4/JAK1/STAT6/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) axis plays a key role in enhancing IL-4-driven M2 polarization (74). Notably, treatment with a PPAR-γ agonist increases splenic Tregs populations and elevates hepatic IL-10 levels in HFD-fed mice (75) (Figure 2c).

When the number of Tregs increases, the IL-10 they secrete inhibits the polarization of M1 Macrophages. Additionally, IL-10 and TGF-β synergistically promote the polarization of M2 Macrophages. This regulatory mechanism plays a crucial role in regulating the progression of inflammation and fibrosis during the pathological process of MASLD.

3.4 Dynamic imbalance of tregs quantity: a double-edged sword

In MASLD patients, the total number of intrahepatic CD4+ T cells decreases, whereas Tregs undergo significant expansion. This trend is corroborated in animal models, where IL-10 expression by Tregs is also markedly elevated (76). The expansion of intrahepatic Tregs does not arise solely from local proliferation but rather reflects enhanced recruitment and accumulation of peripheral Tregs due to alterations in the hepatic microenvironment. For example, animal studies have shown that amphiregulin (Areg)-producing Tregs are enriched in the livers of both mice and humans with NASH, where they contribute to tissue repair. Paradoxically, deletion of Areg in myeloid cells attenuates liver fibrosis (77). These findings demonstrate that FoxP3+ Tregs in MASLD exert a pronounced “double-edged sword” effect during disease progression (26). In early-stage MASLD, intrahepatic Tregs expand through recruitment and activation (78), supporting immune equilibrium and metabolic homeostasis. However, as the disease progresses to MASH and fibrosis, inflammatory and metabolic alterations in the hepatic microenvironment impair the immunosuppressive capacity of Tregs (79). At this stage, the increased Tregs population paradoxically exacerbates disease progression. Adoptive T-cell transfer experiments directly demonstrate that Tregs aggravate hepatic steatosis, enhance lipid accumulation, and worsen metabolic dysregulation (80)(Figure 2d).

The increased number of Tregs is accompanied by functional heterogeneity, and they regulate inflammation and fibrosis through the secretion of cytokines and other substances, thereby exhibiting a double-edged sword property.

4 Impact of dysregulated macrophages-tregs crosstalk on MASLD progression

4.1 The vicious cyclical role of chemokines in MASLD

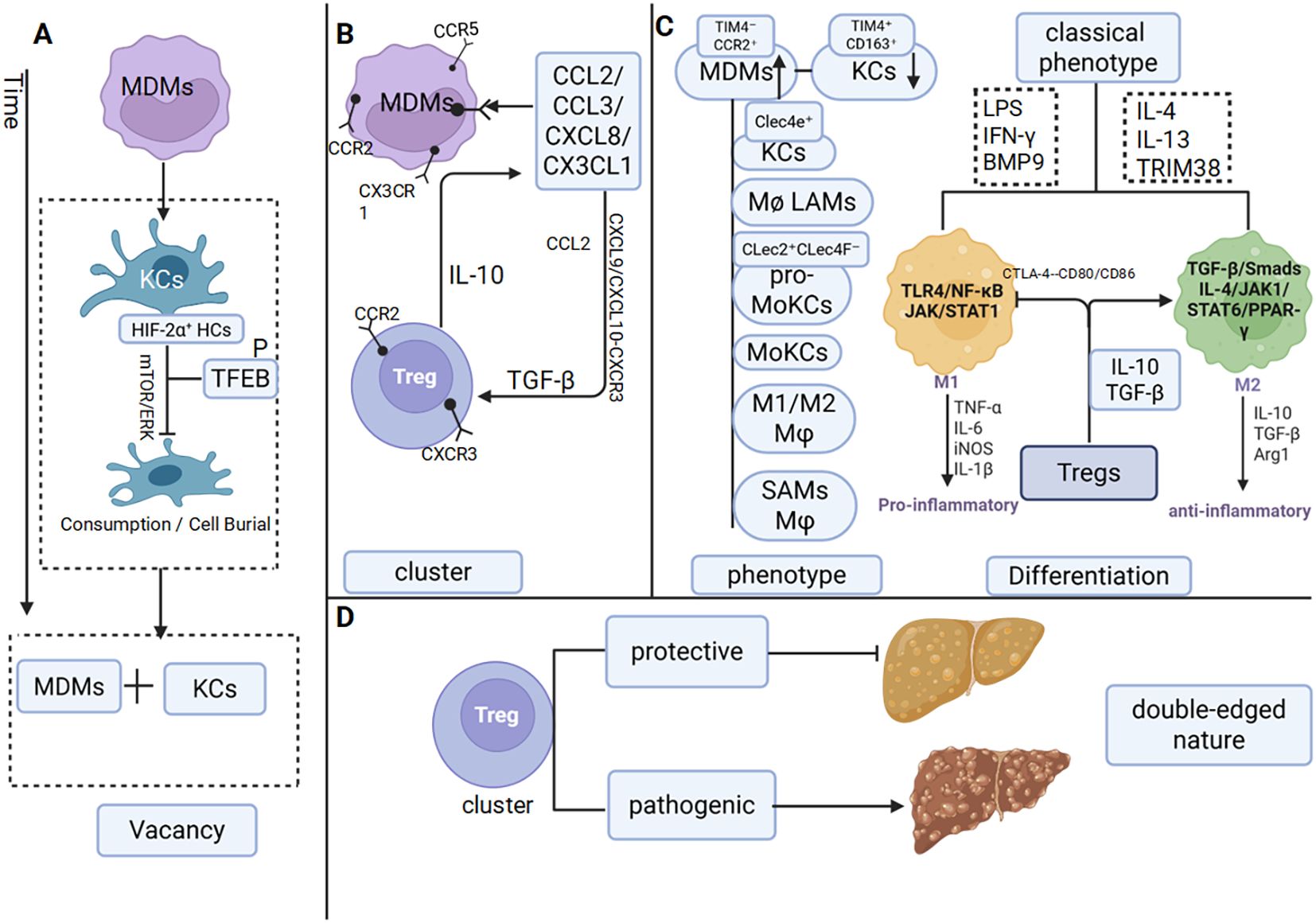

Data from human genetic databases on MASLD indicate that CXCL9, a pivotal chemokine, exhibits a strong positive correlation with M1 Macrophages activity in the liver (81). CXCL9 is significantly upregulated in hepatocytes of patients with MASH, and a comparable increase is observed in mice fed an methionine-choline-deficient diet (MCD) diet (82). Silencing the MIG/CXCL9 gene in MASH mice ameliorates disease pathology, likely by altering the Treg/ interleukin-17 (Th17) cell ratio (56), thereby establishing a vicious cycle in which elevated CXCL9 suppresses Tregs function and promotes Th17 expansion, ultimately amplifying inflammation. In ApoA4−/− models, the proportion of CXCL9-high inflammatory Macrophages subsets (2-Macrophages-CXCL9) markedly increases, exacerbating intrahepatic inflammation (83), and supporting its potential as a biomarker of disease progression (84). In contrast to the pro-inflammatory role of CXCL9, CXCL4 (PF4) is highly expressed in Ncoa5− Macrophages, where it not only promotes lipid accumulation by activating the PPAR-γ2 pathway in hepatocytes but also induces M2 Macrophages polarization and recruits Tregs (85). This dual activity contributes to an aberrant hepatic microenvironment characterized by “lipid accumulation promotion plus pathological immune suppression.” In CD4+ T cell-specific KLF10 knockout mice, Tregs from HFD-fed animals exhibit impaired migration toward CCL19 (due to reduced CCR7 expression) and decreased TGF-β3 secretion. This dysfunction leads to the pathological accumulation of Ly6C+ high pro-inflammatory Macrophages and the formation of crown-like structures (CLSs) in adipose tissue (86).

SPP1 exerts complex, bidirectional regulatory effects within the dynamic Macrophages-Tregs crosstalk network, displaying context-dependent roles that correlate with MASLD progression and immune infiltration (83, 84). In both NASH patients and murine models, SPP1+ -high Macrophages show an inverse correlation with pro-inflammatory genes such as CCL2, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and TNF-α, and are associated with lower steatosis scores, suggesting a potential anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective role for these hepatic Macrophages populations (87). Conversely, in advanced fibrosis (F3-F4), increased SPP1 expression coincides with enhanced infiltration of Tregs and CD68+CD11b+ KCs, implicating SPP1 in fibrotic progression via immune cell recruitment (88). Furthermore, chronic intermittent hypoxia exacerbates hepatocellular injury and fibrogenesis through SPP1-mediated M1 Macrophages polarization (89). In obesity-driven chronic inflammation, SPP1 deficiency increases Tregs proportions, indicating that SPP1 overexpression normally suppresses Tregs accumulation (61) (Figure 3a).

Figure 3. The molecular mechanisms underlying the interaction between Macrophages and Tregs. (a) Role of chemokines in regulating Macrophage-Treg crosstalk during MASLD progression. (b) Macrophages and Tregs promote MASLD through signaling pathways.

The high expression of SPP1 regulates the crosstalk balance between Macrophages and regulatory Tregs. In the early stage, it exhibits anti-inflammatory properties by downregulating chemokine expression; in the late stage, however, it exerts pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic effects. These findings demonstrate the dual nature of SPP1.

4.2 Cytokine crosstalk in the inflammation-fibrosis transition

4.2.1 Cytokine imbalance-mediated tregs-macrophages crosstalk in MASLD inflammatory progression

Cytokines act as the central mediators of Macrophages-Tregs crosstalk and serve as molecular switches driving the transition from inflammation to fibrosis in MASLD. Their dysregulated network profoundly alters Macrophages-Tregs interactions, directly influencing disease trajectory (90, 91). As previously discussed, Tregs regulate Macrophages phenotypic plasticity, and both cell types are dynamically shaped by the surrounding cytokine milieu. In murine MASLD models, T cell-specific nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group a member 1/2 (Nr4a1/2) double knockout leads to a significant expansion of tissue-resident Tregs (CD44+CD62L–CD69+), accompanied by reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and IL-17, and diminished activation of inflammatory Macrophages (92). This attenuation of systemic inflammation is largely mediated by IL-10 secreted from Tregs, which promotes M2 polarization of Macrophages (40). Moreover, Tregs expansion directly suppresses Macrophages infiltration, resulting in a marked reduction of hepatic inflammation (93). Conversely, genetic ablation of Tregs (Foxp3DTR mice) induces substantial hepatic infiltration of neutrophils and Macrophages (93), coupled with decreased Arginase-1 expression in M2 Macrophages and elevated levels of M1-associated mediators such as IL-1β and iNOS (71). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that reciprocal phenotypic regulation between Tregs and Macrophages is a key determinant of inflammatory progression during MASLD.

4.2.2 Th17/tregs imbalance drives the inflammation-fibrosis cascade

Within the dysregulated Macrophages-Tregs interaction network, the Th17/Tregs ratio and functional disequilibrium serve as pivotal determinants of inflammatory amplification and fibrotic progression in MASLD (94). Clinical evidence indicates that NASH patients with NAS scores > 4 display both increased intrahepatic Foxp3+ Tregs populations correlating with inflammatory severity and expanded CD68+ Macrophages regions (95). Elevated Th17 cell frequency is a hallmark of disease progression (96). IL-17, a key Th17 effector cytokine, exacerbates hepatocyte lipotoxicity via JNK pathway activation and counteracts the protective effects of interleukin-22 (IL-22), thereby impairing Tregs-mediated immunosuppression (97, 98). Additionally, IL-17 disrupts insulin signaling to worsen steatosis and synergizes with FFAs to induce IL-6 production in both HepG2 cells and murine hepatocytes. The combination of IL-6 and TGF-β promotes Th17 expansion (99), establishing a self-perpetuating inflammatory loop. This cascade ultimately impairs the suppressive function of Tregs within the hepatic microenvironment (79).

4.2.3 Dual role of tregs and TGF-β in MASLD: from immunosuppression to fibrosis

TGF-β, a pleiotropic cytokine, suppresses cytotoxic t lymphocyte (CTL), T Helper 1 Cell (Th1), and T Helper 2 Cell (Th2) differentiation while promoting peripheral Tregs generation, thus maintaining immune homeostasis (100). In the liver, TGF-β facilitates immunosuppression by enhancing Tregs recruitment via LSEC-derived signaling and promoting M2 Macrophages polarization through Tregs-derived IL-10, establishing TGF-β as a central mediator of Macrophages-Tregs crosstalk (40).

However, the activation of TGF-β is also a critical driver of hepatic fibrogenesis. It classically induces extracellular matrix (ECM) gene transcription in HSCs via the Smad2/3 pathway. Concurrently, its interaction with the unfolded protein response (UPR) further amplifies ECM synthesis and HSC activation, thereby accelerating fibrotic progression (101). Both in vivo and in vitro studies have shown that Tregs and M2 Macrophages synergistically promote excessive TGF-β expression (40, 102). leading to aggravated fibrosis. Selective depletion of Tregs reduces M2 Macrophages proportions in fibrotic livers and decreases TGF-β secretion, suggesting that Tregs enhance TGF-β production by driving KCs polarization toward the M2 phenotype, thus facilitating fibrosis (71). Moreover, integrin αvβ8, specifically expressed by Tregs, cleaves latent TGF-β; its upregulation in fatty liver-associated Tregs directly implicates them in exacerbating fibrosis via enhanced TGF-β activation (27).

Tregs also promote fibrogenesis through Areg secretion in addition to TGF-β signaling (103). Tregs-derived Areg activates HSCs via epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling, inducing myofibroblast transdifferentiation, enhancing collagen synthesis, and promoting ECM deposition. Conditional deletion of Areg in Tregs significantly reduces expression of HSC activation markers (α-smooth Muscle Actin 2 (α-SMA/Acta2) and Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases 1 (Timp1)) and attenuates fibrosis (77, 104) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Macrophages and Tregs promote MASLD via cytokines and dual roles of Tregs and TGF-β in MASLD.

4.3 Crosstalk between signaling pathways

β-Catenin expression in MASLD displays stage-specific alterations distinct from those observed in healthy individuals. Studies demonstrate that β-catenin-related genes (TCF7L2, GLP1, AXIN2, FOSL1, WISP1) are suppressed in NASH patients (105), whereas β-catenin upregulation in infiltrating Macrophages promotes Tregs differentiation by regulating exosomal α-SNAP secretion (106). Furthermore, myeloid PTEN-mediated β-catenin activation induces FOXP3+ Tregs through the PPAR-γ/Jagged-1/Notch pathway while concurrently suppressing Th17 cell differentiation (107), a process likely coordinated through synergistic interaction with Notch1 (Notch1) signaling.

Notch1, the central transmembrane receptor of the Notch signaling pathway, also contributes to MASLD progression. In liver tissues from both MASLD patients and HFD-fed mice, Notch1 activation is markedly elevated, particularly in infiltrating Macrophages exhibiting β-catenin upregulation, and its activity shows a significant negative correlation with Tregs abundance. Macrophages-specific Notch1 knockout (Notch1M-KO) alleviates hepatic steatosis and normalizes Tregs frequencies through a mechanism dependent on Macrophages-derived exosomal miR-142a-3p, which targets TGF-β receptor 1 in T cells (13). In parallel, Rbpj, a key transcriptional regulator of Notch signaling, when deleted reduces the accumulation of pro-inflammatory Clec4e+ Macrophages and diminishes the production of inflammatory cytokines (59).

Beta-arrestin 2 (β-arrestin2) further modulates Macrophages polarization in the pathogenesis of MASH. In MASH patients, β-arrestin2 expression in hepatic CD68+ Macrophages and circulating monocytes positively correlates with hepatic steatosis severity and the expression of M1 markers (IL-1β, NOS2). Its knockdown suppresses M1 polarization, decreases pro-inflammatory IL-1β secretion, and increases anti-inflammatory IL-10 levels (108). Mechanistically, β-arrestin2 competitively binds tak1-binding protein 1 (TAB1), thereby inhibiting formation of the transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1)/ Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 (TGF-β1) complex (109). Given that TGF-β1 is crucial for Tregs differentiation, this interference indirectly impairs Tregs development (101).

In addition, toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) signaling regulates TNF-α secretion by KCs in MCD diet-induced MASLD mice, promoting Tregs apoptosis. Conversely, TLR7 knockout or TLR7 antagonist treatment restores Tregs proportions, mitigates intrahepatic inflammation, and reduces hepatic steatosis (110) (Figure 3b).

5 Stage-specific targeted therapeutic strategies for MASLD

Given the heterogeneity and dynamic progression of MASLD, therapeutic strategies targeting Macrophages-Tregs crosstalk must be tailored to specific disease stages. In the simple steatosis stage, dysregulated lipid metabolism and pro-inflammatory factor secretion by KCs dominate (111, 112). In contrast, during the MASH to fibrosis transition, infiltration of pro-inflammatory Macrophages phenotypes and an increase in Tregs abundance trigger activation of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic gene programs (113, 114). Consequently, the therapeutic focus differs across these stages.

Thus, pathology-stratified, stage-specific treatments represent a critical direction for future clinical translation. The following sections outline potential therapeutic strategies targeting Macrophages-Tregs crosstalk according to MASLD progression.

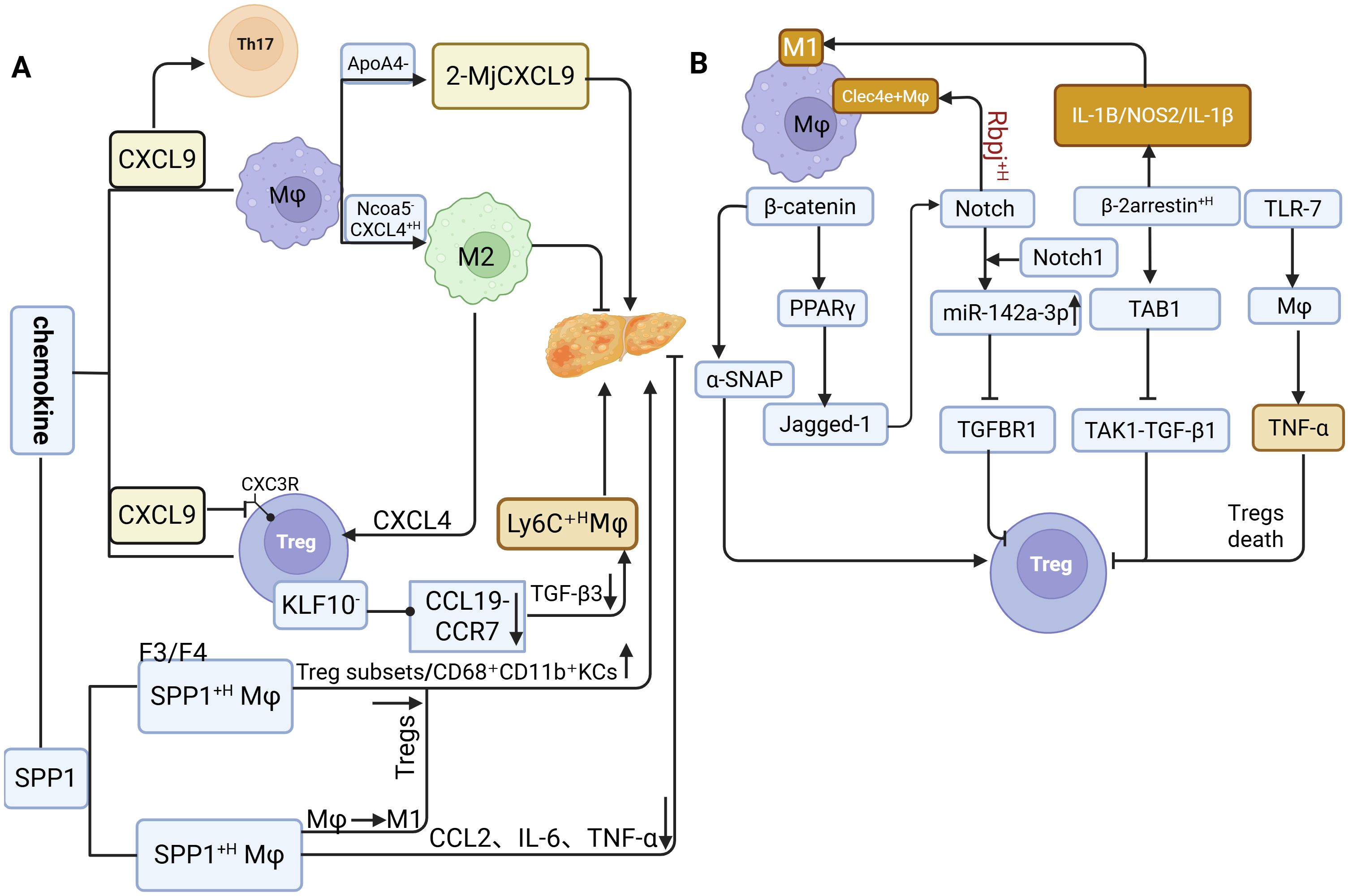

5.1 Synergistic regulation of macrophages and tregs to delay MASLD: for the simple steatosis stage

Early modulation of chemokine activity can ameliorate Macrophages-Tregs crosstalk, thereby delaying MASLD progression. The dual CCR2/5 inhibitor cenicriviroc reduces serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels by shifting Macrophages polarization from Ly6Chi to Ly6Cmed subsets, concurrently suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and T-cell activation markers (IL-2, CD25+) (115).

Astaxanthin exerts multi-target protective effects in MASLD. It downregulates lipid metabolism genes (Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 1c (SREBP1c), FAS, CD36) to decrease hepatic triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), and non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) accumulation. Simultaneously, it inhibits the JNK/p38 MAPK/NF-κB pathway, reducing F4/80+ Macrophages infiltration and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (TNF, IL-6). Astaxanthin also promotes Macrophages polarization toward the M2 phenotype, upregulates CD11c–CD206+, Cd163, and IL-10, and decreases CD4+ T-cell infiltration by 54%. Clinical studies have confirmed that astaxanthin alleviates hepatic steatosis and improves NAS scores in NASH patients (116).

5.2 Modulation of β-catenin signaling in macrophages to delay MASLD progression: for the MASH stage

Therapeutically targeting the β-catenin signaling pathway may disrupt MASLD pathogenesis and represents a promising clinical strategy. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays a central regulatory role in MASLD. Studies show that CXXC5 expression is markedly elevated in both NASH patients and mouse models, while KY19334, a small-molecule activator, enhances Wnt/β-catenin signaling to suppress hepatic lipogenic genes (PPAR-γ, CEBPA), reduce hepatic infiltration of F4/80+ and Cd11b+ Macrophages, and downregulate inflammatory and fibrogenic markers (TNF-α, Mcp1, α-SMA, Col1a1), exhibiting superior efficacy to current treatments (105). Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway also protects the gut vascular barrier against Escherichia coli NF73-1-induced disruption, preventing bacterial translocation and mitigating HFD-induced steatosis (117). Additionally, microRNA-21 antagonism enhances β-catenin signaling by upregulating Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 6 (LRP6), downregulating Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Beta (GSK3β), and increasing β-catenin stability, thereby improving lipid metabolism and reducing TG, TC, ALT, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) through SREBP1c/ fatty acid synthase (FAS) inhibition and amp-activated protein kinase α subunit (AMPKα)/CPT1α activation (118). The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonist Exendin-4 further modulates FABP1/FOXA1 expression via a Wnt/β-catenin-dependent mechanism, influencing lipid synthesis (SREBP-1/PPAR-γ) and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion (ApoB) (119).

Treatment with PRI-724, a β-catenin/CBP inhibitor, significantly ameliorates hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in MASLD mouse models, evidenced by increased hepatic Marco+Mmp9+Cd68+ KCs and reduced levels of ALT, Mac-2 bp, and fibrotic markers (collagen I/III, α-SMA) (120). Similarly, the A3AR antagonist FM101 promotes lysosomal degradation of A3AR via β-arrestin2, effectively improving liver injury by reducing ALT/AST/cholesterol and downregulating fibrogenic (Col1a1, Col4a1, Lox, Timp1) and pro-inflammatory genes (TNF-α, IL-1β, CCL2/3), while inhibiting JNK/ERK/NF-κB and other key inflammatory pathways (121).

5.3 Targeting the tregs-Th17 balance for immunomodulation to delay MASLD: for the fibrotic phase

Regulating the Tregs-Th17 balance is a key immunomodulatory strategy to mitigate MASLD progression. Oral administration of the OKT3 antibody increases CD4+LAP+ and CD4+CD25+LAP+ Tregs populations, elevates serum TGF-β, significantly reduces AST, and improves insulin resistance and hepatic injury (122). Inhibition of IL-17 or IL-6 restores Th17/Tregs balance; IL-17 neutralization reduces ALT levels and hepatic inflammation via suppression of the JNK/NF-κB pathway (99). Polyenyl phosphatidylcholine (PPC) exerts therapeutic effects by downregulating Th17-associated factors ( retinoic acid-related orphan receptor γt (RORγt), STAT3, IL-6) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, TGF-β), while modulating the RORγt/FoxP3 ratio, leading to improvements in ALT/AST and lipid metabolism (TG/CHOL) (123). Ursolic acid alleviates MASLD in HFD-induced models by inhibiting Th17 differentiation through the SPP1-ITGB1/CD44-ERK pathway, thereby reducing TG, TC, ALT, AST, IL-17A, TNF-α, and IL-6, and diminishing hepatic lipid deposition. It also decreases fibrotic markers (α-SMA, collagen I, fibronectin) and extracellular matrix accumulation, alongside a pronounced reduction in IL-17A+CD3+CD4+ (Th17) cells in the liver (124).

Targeting Notch1 signaling can further coordinate Macrophages polarization and Tregs function. Notch1M-KO alleviates steatosis and restores Tregs proportions (13). Quercetin suppresses Notch1 expression, reducing F4/80+ and CD68+ Macrophages infiltration, downregulating M1 markers (CD11c, IL-12, IRF5) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), NOS2), while lowering M2-associated proteins (Ym-1, CD163, Arg I) and fibrotic indicators (Col3α1, Col4α1, CTGF, TIMP-1) (125). (Table 1).

6 Summary and future perspective

The dynamic balance between Macrophages and Tregs is essential for maintaining hepatic immune homeostasis, and their aberrant crosstalk constitutes a central mechanism driving MASLD progression. This interplay involves Macrophages recruitment, phenotypic differentiation, and quantitative changes in Tregs, orchestrated through networks of chemokines, cytokines, and signaling pathways. Dysregulation across these levels promotes the transition from hepatic inflammation to fibrosis.

The heterogeneity of both Macrophages and Tregs poses significant challenges for targeted modulation in MASLD. Macrophages phenotypic plasticity is dynamically shaped by the hepatic microenvironment, whereas Tregs exhibit stage-dependent dual roles, rendering single-target interventions insufficient. Moreover, the convergence of multiple intersecting pathways (such as β-catenin and Notch1) raises the risk of off-target effects. A critical barrier in MASLD clinical translation is the difficulty of precisely staging patients due to a lack of specific biomarkers, coupled with a dynamic immune microenvironment that renders therapeutic effects highly variable. The current lack of stage-stratified treatment protocols remains a major impediment to progress.

Future breakthroughs will require single-cell resolution analyses to delineate cellular heterogeneity and the development of stage-specific combination therapies targeting key pathways such as Notch1 and IL-17 through cell-specific delivery strategies.

Author contributions

HZ: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WW: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. ZS: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81173217) for the research on "Study on the activation of PGC-1α and mitochondrial metabolism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease induced by Xinwen Tongyang Chinese medicine".

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China for supporting this study and LetPub (www.letpub.com.cn) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Glossary

MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Tregs: Regulatory T cells

KCs: Kupffer cells

MDMs: Monocyte-derived Macrophages

HFD: High-fat diet

LSECs: Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells

IL-10: Interleukin-10

TGF-β: Transforming growth factor Beta

CTLA-4: Cytotoxic t-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

CD80: Cluster of differentiation 80

CD86: Cluster of differentiation 86

FoxP3: Fork head box p3

CD25: Cluster of differentiation 25

HS: Hepatic sinusoids

PD-1: Programmed death-1

PD-L1: Programmed death-ligand 1

APCs: Antigen-presenting cells

TCRs: Treg T-cell receptors

IL-2: Interleukin-2

TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

IFN-γ: Interferon-gamma

TLR4: Toll-like receptor 4

NF-κb: Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B Cells

CLEC4F: C-type lectin domain family 4, member F

TIM4: T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 4

HIF-2α: Hypoxia-inducible factor-2 alpha

NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

mTOR: Mechanistic target of rapamycin

ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

MASH: Metabolic-associated steatohepatitis

HMGB1: High mobility group box 1

MyD88: Myeloid differentiation primary response 88

CCL2: C-c motif chemokine ligand 2

CCL3: C-c motif chemokine ligand 3

CXCL8: C-x-c motif chemokine ligand 8

Trem2: Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2

CCR2: C-c motif chemokine receptor 2

CCL5: C-c motif chemokine ligand 5

HSCs: Hepatic stellate cells

CX3CL1: C-x3-c motif chemokine ligand 1

CX3CR1: C-x3-c motif chemokine receptor 1

CXCL9: C-x-c motif chemokine ligand 9

CXCL10: C-x-c motif chemokine ligand 10

MIG: Monokine induced by gamma interferon

ILC1s: Type 1 innate lymphoid cell

CD163: Cluster of differentiation 163

FPC: Fructose: palmitate and cholesterol

References

1. Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, Anstee QM, Targher G, Romero-Gomez M, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. (2020) 73:202–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039

2. Mohan V, Joshi S, Kant S, Shaikh A, Sreenivasa Murthy L, Saboo B, et al. Prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: mapping across different Indian populations (MAP study). Diabetes Ther. (2025) 16:1435–50. doi: 10.1007/s13300-025-01748-1

3. Younossi ZM, Kalligeros M, and Henry L. Epidemiology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. (2025) 31:S32–50. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2024.0431

4. Miao L, Targher G, Byrne CD, Cao Y-Y, and Zheng M-H. Current status and future trends of the global burden of MASLD. Trends Endocrinol Metab. (2024) 35:697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2024.02.007

5. Younossi ZM, Zelber-Sagi S, Kuglemas C, Lazarus JV, Paik A, De Avila L, et al. Association of food insecurity with MASLD prevalence and liver-related mortality. J Hepatol. (2025) 82:203–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2024.08.011

6. Kalligeros M, Vassilopoulos A, Vassilopoulos S, Victor DW, Mylonakis E, and Noureddin M. Prevalence of steatotic liver disease (MASLD, metALD, and ALD) in the United States: NHANES 2017–2020. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2024) 22:1330–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.11.003

7. Liu Z, Huang J, Dai L, Yuan H, Jiang Y, Suo C, et al. Steatotic liver disease prevalence in China: A population-based study and meta-analysis of 17.4 million individuals. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2025) 61:1110–22. doi: 10.1111/apt.70051

8. Giri S and Singh A. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in India – an updated review for 2024. J Clin Exp Hepatol. (2024) 14:101447. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2024.101447

9. Bansal SK and Bansal MB. Pathogenesis of MASLD and MASH – role of insulin resistance and lipotoxicity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2024) 59:S10–22. doi: 10.1111/apt.17930

10. Xiao J, Wang F, Yuan Y, Gao J, Xiao L, Yan C, et al. Epidemiology of liver diseases: global disease burden and forecasted research trends. Sci China Life Sci. (2025) 68:541–57. doi: 10.1007/s11427-024-2722-2

11. Lee H-H, Lee HA, Kim E-J, Kim HY, Kim HC, Ahn SH, et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and risk of cardiovascular disease. Gut. (2023) 31:S32–50. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2023-331003

12. Sandireddy R, Sakthivel S, Gupta P, Behari J, Tripathi M, and Singh BK. Systemic impacts of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) on heart, muscle, and kidney related diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2024) 12:1433857. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2024.1433857

13. Zhang M, Li K, Huang X, Xu D, Zong R, Hu Q, et al. Macrophage Notch1 signaling modulates regulatory T cells via the TGFB axis in early MASLD. JHEP Rep. (2025) 7:101242. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2024.101242

14. Huby T and Gautier EL. Immune cell-mediated features of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Nat Rev Immunol. (2022) 22:429–43. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00639-3

15. Su GL, Klein RD, Aminlari A, Zhang HY, Steinstraesser L, Alarcon WH, et al. Kupffer cell activation by lipopolysaccharide in rats: Role for lipopolysaccharide binding protein and toll-like receptor 4. Hepatology. (2000) 31:932–6. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5634

16. Zhao D, Yang F, Wang Y, Li S, Li Y, Hou F, et al. ALK1 signaling is required for the homeostasis of Kupffer cells and prevention of bacterial infection. J Clin Invest. (2022) 132:e150489. doi: 10.1172/JCI150489

17. Zeng Z, Surewaard BGJ, Wong CHY, Geoghegan JA, Jenne CN, and Kubes P. CRIg functions as a macrophage pattern recognition receptor to directly bind and capture blood-borne gram-positive bacteria. Cell Host Microbe. (2016) 20:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.06.002

18. Sakai M, Troutman TD, Seidman JS, Ouyang Z, Spann NJ, Abe Y, et al. Liver-derived signals sequentially reprogram myeloid enhancers to initiate and maintain kupffer cell identity. Immunity. (2019) 51:655–70. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.09.002

19. Miyamoto Y, Kikuta J, Matsui T, Hasegawa T, Fujii K, Okuzaki D, et al. Periportal macrophages protect against commensal-driven liver inflammation. Nature. (2024) 629:901–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07372-6

20. Osei-Bordom D, Bozward AG, and Oo YH. The hepatic microenvironment and regulatory T cells. Cell Immunol. (2020) 357:104195. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2020.104195

21. Ding C, Yu Z, Sefik E, Zhou J, Kaffe E, Wang G, et al. A Treg-specific long noncoding RNA maintains immune-metabolic homeostasis in aging liver. Nat Aging. (2023) 3:813–28. doi: 10.1038/s43587-023-00428-8

22. Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, and Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. (2008) 133:775–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009

23. Ma P, Zhao W, Gao C, Liang Z, Zhao L, Qin H, et al. The Contribution of Hepatic Macrophage Heterogeneity during Liver Regeneration after Partial Hepatectomy in Mice. J Immunol Res. (2022) 2022:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2022/3353250

24. Jeelani I, Moon J-S, Da Cunha FF, Nasamran CA, Jeon S, Zhang X, et al. HIF-2α drives hepatic Kupffer cell death and proinflammatory recruited macrophage activation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Sci Transl Med. (2024) 16:764. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adi0284

25. Vahrenbrink M, Coleman CD, Kuipers S, Lurje I, Hammerich L, Kunkel D, et al. Dynamic changes in macrophage populations and resulting alterations in Prostaglandin E2 sensitivity in mice with diet-induced MASH. Cell Commun Signal. (2025) 23:227. doi: 10.1186/s12964-025-02222-y

26. Wang H, Tsung A, Mishra L, and Huang H. Regulatory T cell: a double-edged sword from metabolic-dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis to hepatocellular carcinoma. eBioMedicine. (2024) 101:105031. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105031

27. Wang K, Farrell A, Zhou E, Qin H, Zeng Z, Zhou K, et al. ATF4 drives regulatory T cell functional specification in homeostasis and obesity. Sci Immunol. (2025) 10:105. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.adp7193

28. Geissmann F, Manz MG, Jung S, Sieweke MH, Merad M, and Ley K. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science. (2010) 327:656–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331

29. Parthasarathy G and Malhi H. Macrophage heterogeneity in NASH: more than just nomenclature. Hepatology. (2021) 74:515–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.31790

30. Gomez Perdiguero E, Klapproth K, Schulz C, Busch K, Azzoni E, Crozet L, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages originate from yolk-sac-derived erythro-myeloid progenitors. Nature. (2015) 518:547–51. doi: 10.1038/nature13989

31. Gola A, Dorrington MG, Speranza E, Sala C, Shih RM, Radtke AJ, et al. Commensal-driven immune zonation of the liver promotes host defence. Nature. (2021) 589:131–6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2977-2

32. Guillot A and Tacke F. Liver macrophages: old dogmas and new insights. Hepatol Commun. (2019) 3:730–43. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1356

33. Knoll P, Schlaak J, Uhrig A, Kempf P, Zum Büschenfelde K-HM, and Gerken G. Human Kupffer cells secrete IL-10 in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge. J Hepatol. (1995) 22:226–9. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80433-1

34. Liu Z, Gu Y, Chakarov S, Bleriot C, Kwok I, Chen X, et al. Fate mapping via ms4a3-expression history traces monocyte-derived cells. Cell. (2019) 178:1509–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.009

35. Burton OT, Bricard O, Tareen S, Gergelits V, Andrews S, Biggins L, et al. The tissue-resident regulatory T cell pool is shaped by transient multi-tissue migration and a conserved residency program. Immunity. (2024) 57:1586–602. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2024.05.023

36. Carambia A, Freund B, Schwinge D, Heine M, Laschtowitz A, Huber S, et al. TGF-β-dependent induction of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. J Hepatol. (2014) 61:594–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.04.027

37. Breous E, Somanathan S, Vandenberghe LH, and Wilson JM. Hepatic regulatory T cells and Kupffer cells are crucial mediators of systemic T cell tolerance to antigens targeting murine liver†. Hepatology. (2009) 50:612–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.23043

38. Karlmark KR, Zimmermann HW, Roderburg C, Gassler N, Wasmuth HE, Luedde T, et al. The fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 protects against liver fibrosis by controlling differentiation and survival of infiltrating hepatic monocytes. Hepatology. (2010) 52:1769–82. doi: 10.1002/hep.23894

39. Heymann F, Peusquens J, Ludwig-Portugall I, Kohlhepp M, Ergen C, Niemietz P, et al. Liver inflammation abrogates immunological tolerance induced by Kupffer cells. Hepatology. (2015) 62:279–91. doi: 10.1002/hep.27793

40. Wang R, Liang Q, Zhang Q, Zhao S, Lin Y, Liu B, et al. Ccl2-induced regulatory T cells balance inflammation through macrophage polarization during liver reconstitution. Adv Sci. (2024) 11:2403849. doi: 10.1002/advs.202403849

41. Li X, Wang Z, Zou Y, Lu E, Duan J, Yang H, et al. Pretreatment with lipopolysaccharide attenuates diethylnitrosamine-caused liver injury in mice via TLR4-dependent induction of Kupffer cell M2 polarization. Immunol Res. (2015) 62:137–45. doi: 10.1007/s12026-015-8644-2

42. Anderson AC, Joller N, and Kuchroo VK. Lag-3, tim-3, and TIGIT: co-inhibitory receptors with specialized functions in immune regulation. Immunity. (2016) 44:989–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.001

43. Zhou Y, Zhang H, Yao Y, Zhang X, Guan Y, and Zheng F. CD4+ T cell activation and inflammation in NASH-related fibrosis. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:967410. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.967410

44. Erhardt A, Biburger M, Papadopoulos T, and Tiegs G. IL-10, regulatory T cells, and Kupffer cells mediate tolerance in concanavalin A–induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology. (2007) 45:475–85. doi: 10.1002/hep.21498

45. Shahoei SH, Kim Y-C, Cler SJ, Ma L, Anakk S, Kemper JK, et al. Small heterodimer partner regulates dichotomous T cell expansion by macrophages. Endocrinology. (2019) 160:1573–89. doi: 10.1210/en.2019-00025

46. Shen Z, Shen B, Dai W, Zhou C, Luo X, Guo Y, et al. Expansion of macrophage and liver sinusoidal endothelial cell subpopulations during non-alcoholic steatohepatitis progression. iScience. (2023) 26:106572. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.106572

47. Daemen S, Gainullina A, Kalugotla G, He L, Chan MM, Beals JW, et al. Dynamic shifts in the composition of resident and recruited macrophages influence tissue remodeling in NASH. Cell Rep. (2021) 34:108626. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108626

48. Seidman JS, Troutman TD, Sakai M, Gola A, Spann NJ, Bennett H, et al. Niche-specific reprogramming of epigenetic landscapes drives myeloid cell diversity in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Immunity. (2020) 52:1057–74. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.001

49. Li L, Chen L, and Hu L. Nuclear factor high-mobility group box1 mediating the activation of toll-like receptor 4 signaling in hepatocytes in the early stage of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. J Clin Exp Hepatol. (2011) 1:123–4. doi: 10.1016/S0973-6883(11)60136-9

50. Nati M, Chung K-J, and Chavakis T. The role of innate immune cells in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Innate Immun. (2022) 14:31–41. doi: 10.1159/000518407

51. Saiman Y and Friedman SL. The role of chemokines in acute liver injury. Front Physiol. (2012) 3:213. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00213

52. Kang J, Postigo-Fernandez J, Kim K, Zhu C, Yu J, Meroni M, et al. Notch-mediated hepatocyte MCP-1 secretion causes liver fibrosis. JCI Insight. (2023) 8:e165369. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.165369

53. Hendrikx T, Porsch F, Kiss MG, Rajcic D, Papac-Miličević N, Hoebinger C, et al. Soluble TREM2 levels reflect the recruitment and expansion of TREM2+ macrophages that localize to fibrotic areas and limit NASH. J Hepatol. (2022) 77:1373–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.06.004

54. Bourd-Boittin K, Basset L, Bonnier D, L’Helgoualc’h A, Samson M, and Théret N. CX3CL1/fractalkine shedding by human hepatic stellate cells: contribution to chronic inflammation in the liver. J Cell Mol Med. (2009) 13:1526–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00787.x

55. Krenkel O, Puengel T, Govaere O, Abdallah AT, Mossanen JC, Kohlhepp M, et al. Therapeutic inhibition of inflammatory monocyte recruitment reduces steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis. Hepatology. (2018) 67:1270–83. doi: 10.1002/hep.29544

56. Li L, Xia Y, Ji X, Wang H, Zhang Z, Lu P, et al. MIG/CXCL9 exacerbates the progression of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease by disrupting Treg/Th17 balance. Exp Cell Res. (2021) 407:112801. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2021.112801

57. Yang BQ, Chan MM, Heo GS, Lou L, Luehmann H, Park C, et al. Molecular imaging of macrophage composition and dynamics in MASLD. JHEP Rep. (2024) 6:101220. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2024.101220

58. Bradić I, Kuentzel KB, Pirchheim A, Rainer S, Schwarz B, Trauner M, et al. From LAL-D to MASLD: Insights into the role of LAL and Kupffer cells in liver inflammation and lipid metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Cell Biol Lipids. (2025) 1870:159575. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2024.159575

59. Guo W, Li Z, Anagnostopoulos G, Kong WT, Zhang S, Chakarov S, et al. Notch signaling regulates macrophage-mediated inflammation in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Immunity. (2024) 57:2310–27. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2024.08.016

60. Kim D, Shah M, Kim JH, Kim J, Baek Y-H, Jeong J-S, et al. Integrative transcriptomic and genomic analyses unveil the IFI16 variants and expression as MASLD progression markers. Hepatology. (2025) 81:962–75. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000805

61. Soysouvanh F, Rousseau D, Bonnafous S, Bourinet M, Strazzulla A, Patouraux S, et al. Osteopontin-driven T-cell accumulation and function in adipose tissue and liver promoted insulin resistance and MAFLD. Obesity. (2023) 31:2568–82. doi: 10.1002/oby.23868

62. Li J, Chen X, Song S, Jiang W, Geng T, Wang T, et al. Hexokinase 2-mediated metabolic stress and inflammation burden of liver macrophages via histone lactylation in MASLD. Cell Rep. (2025) 44:115350. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2025.115350

63. Peiseler M, Araujo David B, Zindel J, Surewaard BGJ, Lee W-Y, Heymann F, et al. Kupffer cell–like syncytia replenish resident macrophage function in the fibrotic liver. Science. (2023) 381:eabq5202. doi: 10.1126/science.abq5202

64. Lv J-J, Wang H, Zhang C, Zhang T-J, Wei H-L, Liu Z-K, et al. CD147 sparks atherosclerosis by driving M1 phenotype and impairing efferocytosis. Circ Res. (2024) 134:165–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.123.323223

65. Wang C, Ma C, Gong L, Guo Y, Fu K, Zhang Y, et al. Macrophage polarization and its role in liver disease. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:803037. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.803037

66. Ma M, Jiang W, and Zhou R. DAMPs and DAMP-sensing receptors in inflammation and diseases. Immunity. (2024) 57:752–71. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2024.03.002

67. Sierra-Filardi E, Nieto C, Domínguez-Soto Á, Barroso R, Sánchez-Mateos P, Puig-Kroger A, et al. CCL2 shapes macrophage polarization by GM-CSF and M-CSF: identification of CCL2/CCR2-dependent gene expression profile. J Immunol. (2014) 192:3858–67. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302821

68. Poulsen KL, Ross CKC-D, Chaney JK, and Nagy LE. Role of the chemokine system in liver fibrosis: a narrative review. Dig Med Res. (2022) 5:30–0. doi: 10.21037/dmr-21-87

69. Jiang Q, Li Q, Liu B, Li G, Riedemann G, Gaitantzi H, et al. BMP9 promotes methionine- and choline-deficient diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in non-obese mice by enhancing NF-κB dependent macrophage polarization. Int Immunopharmacol. (2021) 96:107591. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107591

70. Xu X, Dong Y, Liu J, Zhang P, Yang W, and Dai L. Regulation of inflammation, lipid metabolism, and liver fibrosis by core genes of M1 macrophages in NASH. J Inflammation Res. (2024) 17:9975–86. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S480574

71. Zhang X, Lou J, Bai L, Chen Y, Zheng S, and Duan Z. Immune regulation of intrahepatic regulatory T cells in fibrotic livers of mice. Med Sci Monit. (2017) 23:1009–16. doi: 10.12659/MSM.899725

72. Feng M, Wang Q, Zhang F, and Lu L. Ex vivo induced regulatory T cells regulate inflammatory response of Kupffer cells by TGF-beta and attenuate liver ischemia reperfusion injury. Int Immunopharmacol. (2012) 12:189–96. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.11.010

73. Yang H, Jung S, and Choi E-Y. E3 ubiquitin ligase trim38 regulates macrophage polarization to reduce hepatic inflammation by interacting with hspa5. (2025) 157:114662. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.5082691

74. Xu Y, Liu J, Wang J, Wang J, Lan P, and Wang T. USP25 stabilizes STAT6 to promote IL-4-induced macrophage M2 polarization and fibrosis. Int J Biol Sci. (2025) 21:475–89. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.99345

75. Xu Z, Wang G, Zhu Y, Liu R, Song J, Ni Y, et al. PPAR-γ agonist ameliorates liver pathology accompanied by increasing regulatory B and T cells in high-fat-diet mice. Obesity. (2017) 25:581–90. doi: 10.1002/oby.21769

76. Wang H, Zhang H, Wang Y, Brown ZJ, Xia Y, Huang Z, et al. Regulatory T-cell and neutrophil extracellular trap interaction contributes to carcinogenesis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. (2021) 75:1271–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.07.032

77. Savage TM, Fortson KT, De Los Santos-Alexis K, Oliveras-Alsina A, Rouanne M, Rae SS, et al. Amphiregulin from regulatory T cells promotes liver fibrosis and insulin resistance in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Immunity. (2024) 57:303–18. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2024.01.009

78. Dywicki J, Buitrago-Molina LE, Noyan F, Davalos-Misslitz AC, Hupa-Breier KL, Lieber M, et al. The detrimental role of regulatory T cells in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol Commun. (2022) 6:320–33. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1807

79. Chaudhary S, Rai R, Pal PB, Tedesco D, Singhi AD, Monga SP, et al. Western diet dampens T regulatory cell function to fuel hepatic inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. (2023). doi: 10.1101/2023.03.23.533977

80. Van Herck MA, Vonghia L, Kwanten WJ, Vanwolleghem T, Ebo DG, Michielsen PP, et al. Adoptive cell transfer of regulatory T cells exacerbates hepatic steatosis in high-fat high-fructose diet-fed mice. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:1711. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01711

81. Zhang J, Wang L, and Jiang M. Diagnostic value of sphingolipid metabolism-related genes CD37 and CXCL9 in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Med (Baltimore). (2024) 103:e37185. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000037185

82. Wang W, Liu X, Wei P, Ye F, Chen Y, Shi L, et al. SPP1 and CXCL9 promote non-alcoholic steatohepatitis progression based on bioinformatics analysis and experimental studies. Front Med. (2022) 9:862278. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.862278

83. Liu X-H, Zhou J-T, Yan C, Cheng C, Fan J-N, Xu J, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals a novel inhibitory effect of ApoA4 on NAFL mediated by liver-specific subsets of myeloid cells. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:1038401. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1038401

84. Wu X, Yuan C, Pan J, Zhou Y, Pan X, Kang J, et al. CXCL9, IL2RB, and SPP1, potential diagnostic biomarkers in the co-morbidity pattern of atherosclerosis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:16364. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-66287-4

85. Zhang Y, Luo Y, Liu X, Kiupel M, Li A, Wang H, et al. NCOA5 haploinsufficiency in myeloid-lineage cells sufficiently causes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2024) 17:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2023.09.007

86. Wara AK, Wang S, Wu C, Fang F, Haemmig S, Weber BN, et al. KLF10 deficiency in CD4+ T cells triggers obesity, insulin resistance, and fatty liver. Cell Rep. (2020) 33:108550. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108550

87. Han H, Ge X, Komakula SSB, Desert R, Das S, Song Z, et al. Macrophage-derived osteopontin (SPP1) protects from nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. (2023) 165:201–17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.03.228

88. Sanchez JI, Parra ER, Jiao J, Solis Soto LM, Ledesma DA, Saldarriaga OA, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Cancers. (2023) 15:2871. doi: 10.3390/cancers15112871

89. Lu FY, Chen XX, Li MY, Yan YR, Wang Y, Li SQ, et al. Chronic intermittent hypoxia exacerbates the progression of NAFLD via SPP1-mediated inflammatory polarization in macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med. (2025) 238:261–74. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2025.06.050

90. Ajith A, Merimi M, Arki MK, Hossein-khannazer N, Najar M, Vosough M, et al. Immune regulation and therapeutic application of T regulatory cells in liver diseases. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1371089. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1371089

91. Friedline RH, Noh HL, Suk S, Albusharif M, Dagdeviren S, Saengnipanthkul S, et al. IFNγ-IL12 axis regulates intercellular crosstalk in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:5506. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-49633-y

92. Aki D, Hayakawa T, Srirat T, Shichino S, Ito M, Saitoh S-I, et al. A. The Nr4a family regulates intrahepatic Treg proliferation and liver fibrosis in MASLD models. J Clin Invest. (2024) 134:e175305. doi: 10.1172/JCI175305

93. Vonghia L, Ruyssers N, Schrijvers D, Pelckmans P, Michielsen P, De Clerck L, et al. CD4+ROR γ t++ and tregs in a mouse model of diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Mediators Inflammation. (2015) 2015:239623. doi: 10.1155/2015/239623

94. Schmitt V, Rink L, and Uciechowski P. The Th17/Treg balance is disturbed during aging. Exp Gerontol. (2013) 48:1379–86. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.09.003

95. Söderberg C, Marmur J, Eckes K, Glaumann H, Sällberg M, Frelin L, et al. Microvesicular fat, inter cellular adhesion molecule-1 and regulatory T-lymphocytes are of importance for the inflammatory process in livers with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: INFLAMMATORY PROCESS IN LIVERS WITH NASH. APMIS. (2011) 119:412–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2011.02746.x

96. Rau M, Schilling A-K, Meertens J, Hering I, Weiss J, Jurowich C, et al. Progression from nonalcoholic fatty liver to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is marked by a higher frequency of th17 cells in the liver and an increased th17/resting regulatory T cell ratio in peripheral blood and in the liver. J Immunol. (2016) 196:97–105. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501175

97. Świderska M, Jaroszewicz J, Stawicka A, Parfieniuk-Kowerda A, Chabowski A, and Flisiak R. The interplay between Th17 and T-regulatory responses as well as adipokines in the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Exp Hepatol. (2017) 3:127–34. doi: 10.5114/ceh.2017.68466

98. Rolla S, Alchera E, Imarisio C, Bardina V, Valente G, Cappello P, et al. The balance between IL-17 and IL-22 produced by liver-infiltrating T-helper cells critically controls NASH development in mice. Clin Sci. (2016) 130:193–203. doi: 10.1042/CS20150405

99. Tang Y, Bian Z, Zhao L, Liu Y, Liang S, Wang Q, et al. Interleukin-17 exacerbates hepatic steatosis and inflammation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Exp Immunol. (2011) 166:281–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04471.x

100. Sanjabi S, Oh SA, and Li MO. Regulation of the immune response by TGF-β: from conception to autoimmunity and infection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. (2017) 9:a022236. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022236

101. Moreau JM, Velegraki M, Bolyard C, Rosenblum MD, and Li Z. Transforming growth factor–β1 in regulatory T cell biology. Sci Immunol. (2022) 7:eabi4613. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abi4613

102. Nuñez SY, Ziblat A, Secchiari F, Torres NI, Sierra JM, Raffo Iraolagoitia XL, et al. Human M2 macrophages limit NK cell effector functions through secretion of TGF-β and engagement of CD85j. J Immunol. (2018) 200:1008–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700737

103. Wu K, Qian Q, Zhou J, Sun D, Duan Y, Zhu X, et al. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) in liver fibrosis. Cell Death Discov. (2023) 9:53. doi: 10.1038/s41420-023-01347-8

104. Lu Y, Wang Y, Ruan T, Wang Y, Ju L, Zhou M, et al. Immunometabolism of Tregs: mechanisms, adaptability, and therapeutic implications in diseases. Front Immunol. (2025) 16:1536020. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1536020

105. Seo SH, Kim E, Yoon M, Lee S-H, Park B-H, and Choi K-Y. Metabolic improvement and liver regeneration by inhibiting CXXC5 function for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis treatment. Exp Mol Med. (2022) 54:1511–23. doi: 10.1038/s12276-022-00851-8

106. Zong R, Liu Y, Zhang M, Liu B, Zhang W, Hu H, et al. β-Catenin disruption decreases macrophage exosomal α-SNAP and impedes Treg differentiation in acute liver injury. JCI Insight. (2025) 10:e182515. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.182515

107. Zhu Q, Li C, Wang K, Yue S, Jiang L, Ke M, et al. Phosphatase and tensin homolog–β-catenin signaling modulates regulatory T cells and inflammatory responses in mouse liver ischemia/reperfusion injury. Liver Transpl. (2017) 23:813–25. doi: 10.1002/lt.24735

108. Wei X, Wu D, Li J, Wu M, Li Q, Che Z, et al. Myeloid beta-arrestin 2 depletion attenuates metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis via the metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Cell Metab. (2024) 36:2281–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2024.08.010

109. Chen T-T, Shan S, Chen Y-N, Li M-Q, Zhang H-J, Li L, et al. Deficiency of β-arrestin2 ameliorates MASLD in mice by promoting the activation of TAK1/AMPK signaling. Arch Pharm Res. (2025) 48:384–403. doi: 10.1007/s12272-025-01544-2

110. Roh YS, Kim JW, Park S, Shon C, Kim S, Eo SK, et al. Toll-like receptor-7 signaling promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by inhibiting regulatory T cells in mice. Am J Pathol. (2018) 188:2574–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.07.011

111. Vonderlin J, Chavakis T, Sieweke M, and Tacke F. The multifaceted roles of macrophages in NAFLD pathogenesis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2023) 15:1311–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2023.03.002

112. Tosello-Trampont A-C, Landes SG, Nguyen V, Novobrantseva TI, and Hahn YS. Kuppfer cells trigger nonalcoholic steatohepatitis development in diet-induced mouse model through tumor necrosis factor-α Production. J Biol Chem. (2012) 287:40161–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.417014

113. Hupa-Breier KL, Schenk H, Campos-Murguia A, Wellhöner F, Heidrich B, Dywicki J, et al. Novel translational mouse models of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease comparable to human MASLD with severe obesity. Mol Metab. (2025) 93:102104. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2025.102104

114. Luo X, Li H, Ma L, Zhou J, Guo X, Woo S-L, et al. Expression of STING is increased in liver tissues from patients with NAFLD and promotes macrophage-mediated hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in mice. Gastroenterology. (2018) 155:1971–1984.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.010

115. Ambade A, Lowe P, Kodys K, Catalano D, Gyongyosi B, Cho Y, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of CCR2/5 signaling prevents and reverses alcohol-induced liver damage, steatosis, and inflammation in mice. Hepatology. (2019) 69:1105–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.30249

116. Ni Y, Nagashimada M, Zhuge F, Zhan L, Nagata N, Tsutsui A, et al. Astaxanthin prevents and reverses diet-induced insulin resistance and steatohepatitis in mice: A comparison with vitamin E. Sci Rep. (2015) 5:17192. doi: 10.1038/srep17192

117. Ke Z, Huang Y, Xu J, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al. Escherichia coli NF73-1 disrupts the gut–vascular barrier and aggravates high-fat diet-induced fatty liver disease via inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway. Liver Int. (2024) 44:776–90. doi: 10.1111/liv.15823

118. Wang X, Wang X, Huang Y, Chen X, Lu M, Shi L, et al. Role and mechanisms of action of microRNA−21 as regards the regulation of the WNT/β−catenin signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of non−alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Mol Med. (2019) 44:2201–12. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4375

119. Khalifa O, AL-Akl NS, Errafii K, and Arredouani A. Exendin-4 alleviates steatosis in an in vitro cell model by lowering FABP1 and FOXA1 expression via the Wnt/-catenin signaling pathway. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:2226. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-06143-5

120. Yamaji K, Iwabuchi S, Tokunaga Y, Hashimoto S, Yamane D, Toyama S, et al. Molecular insights of a CBP/β-catenin-signaling inhibitor on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-induced liver fibrosis and disorder. BioMed Pharmacother. (2023) 166:115379. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115379

121. Park J-S, Ma Y-Q, Wang F, Ma H, Sui G, Rustamov N, et al. A3AR antagonism mitigates metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease by exploiting monocyte-derived Kupffer cell necroptosis and inflammation resolution. Metabolism. (2025) 164:156114. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2024.156114

122. Lalazar G, Mizrahi M, Turgeman I, Adar T, Ben Ya’acov A, Shabat Y, et al. Oral administration of OKT3 MAb to patients with NASH, promotes regulatory T-cell induction, and alleviates insulin resistance: results of a phase IIa blinded placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Immunol. (2015) 35:399–407. doi: 10.1007/s10875-015-0160-6

123. He B, Wu L, Xie W, Shao Y, Jiang J, Zhao Z, et al. The imbalance of Th17/Treg cells is involved in the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. BMC Immunol. (2017) 18:33. doi: 10.1186/s12865-017-0215-y

124. Zheng Y, Zhao L, Xiong Z, Huang C, Yong Q, Fang D, et al. Ursolic acid targets secreted phosphoprotein 1 to regulate Th17 cells against metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. (2024) 30:449–67. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2024.0047