- 1Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, Changsha, China

- 2Department of Nephrology, The Central Hospital of Shaoyang, Shaoyang, Hunan, China

- 3People’s Hospital of Ningxiang City, Ningxiang, China

Neurodegenerative diseases are a group of disorders characterized by progressive loss of neuronal function due to degenerative damage to neural cells. Ferroptosis, a newly identified form of regulated cell death, is pathologically defined by iron-dependent accumulation of lipid peroxides, mitochondrial shrinkage, and increased mitochondrial membrane density. Unlike apoptosis or necrosis, ferroptosis is driven by a combination of factors, including excessive lipid peroxidation, disruption of iron homeostasis, and depletion of antioxidant defenses such as glutathione (GSH) and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4). The ferroptotic process engages multiple biological functions—such as iron metabolism, lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, mevalonate signaling, transsulfuration pathways, heat shock protein activation, glutamate/cystine transport, and GSH biosynthesis. While initial studies focused on its role in cancer, accumulating evidence now links ferroptosis to neurological disorders. Ferroptosis has been implicated in the pathophysiology of stroke, traumatic brain injury, and major neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and Huntington’s disease (HD). Several small-molecule inhibitors—including ferrostatin-1, liproxstatin-1, and iron chelators such as deferoxamine (DFO)—have demonstrated efficacy in animal models by attenuating neuronal damage and improving behavioral outcomes through the suppression of ferroptosis. In addition, natural compounds have emerged as promising candidates for targeting ferroptosis due to their structural diversity, low toxicity, and multitarget regulatory properties. These agents offer potential leads for developing novel neuroprotective therapeutics. Neurodegenerative diseases remain a significant global health burden, with limited effective treatments available to date. Modulation of ferroptosis presents a new conceptual framework for therapeutic intervention, offering hope for disease-modifying strategies. This review summarizes recent advances in understanding the role of ferroptosis in neurodegenerative disease mechanisms, focusing on its contribution to pathological progression, molecular regulation, and therapeutic interventions. By integrating current findings, we aim to provide theoretical insights into novel pathogenic mechanisms and scientific guidance for the development of targeted therapies that modulate ferroptosis to slow or halt disease progression.

1 Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases are irreversible disorders of the nervous system caused by progressive loss of neurons in the brain and spinal cord (1). These diseases result from the degeneration of neurons and/or their myelin sheaths, leading to worsening functional impairments over time (2). Neurodegenerative diseases can be classified as acute or chronic. Acute neurodegeneration includes conditions such as cerebral ischemia (CI), brain injury (BI), and epilepsy, whereas chronic forms encompass major diseases like Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD). Among these, AD and PD are the two most prevalent neurodegenerative diseases in the elderly population—AD is primarily characterized by cognitive decline, while PD manifests with motor dysfunction (3). Despite extensive research, the exact etiology of most neurodegenerative diseases remains elusive, and no curative treatments currently exist, making these diseases a significant threat to human health and quality of life. Age-associated neurodegenerative diseases pose an increasing risk in the context of global population aging (2–4). According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, in 2019 alone, the global prevalence of AD and related dementias reached 51.62 million, with an overall prevalence rate of 667.2 per 100,000 individuals and an age-standardized prevalence of 682.5 per 100,000 (5). In China, the incidence of PD among individuals aged ≥65 years is approximately 1.7%, with approximately 100,000 new cases reported annually, reflecting a rapidly rising trend. More than 2.5 million people in China suffer from AD, making it the country with both the largest absolute number of patients and the fastest-growing AD population globally (6). Therefore, there is an urgent need to uncover the underlying mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases.

In recent decades, studies have identified several key factors contributing to neurodegeneration, including inflammation, aging, oxidative stress, and genetic mutations (7, 8). Given that neurodegenerative diseases predominantly affect middle-aged and elderly populations, cellular senescence has been increasingly recognized as a central driver of disease onset and progression. Aging-related accumulation of senescent cells in the nervous system leads to neuronal dysfunction and exacerbates disease pathology (9), highlighting cellular aging as one of the most critical risk factors for neurodegeneration (4). Evidence suggests that cellular stress responses, such as oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction, accelerate cellular aging (10). During physiological aging and the development of age-related pathologies, the cellular response to oxidative stress and its capacity for repair become dysregulated, further promoting senescence and cell death (11).

Over the past few decades, multiple modes of cell death have been defined. The Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death (NCCD) classifies cell death into two broad categories based on functional and mechanistic criteria: accidental cell death (ACD), a passive process, and regulated cell death (RCD), an active, gene-controlled mechanism (12). RCD encompasses several subtypes, among which apoptosis—the caspase-dependent form of programmed cell death—is the most extensively studied (12). However, in pathological contexts such as infection, trauma, and neurodegenerative diseases, alternative non-apoptotic forms of RCD dominate, including necroptosis, pyroptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis (13–16).

Ferroptosis, first identified and described by Dixon et al. in 2012, is a unique form of regulated necrosis driven by iron-dependent accumulation of toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) within lipid membranes (17). Subsequent studies revealed that ferroptosis may serve as a crucial cell death mechanism in acute brain injuries such as ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage (18). At the molecular level, ferroptosis is characterized by iron-dependent lipid ROS accumulation, which results from irreversible lipid peroxidation and membrane permeabilization (19). Morphologically, ferroptosis presents with distinct mitochondrial changes, including organelle shrinkage and loss of cristae (20). Although the precise mechanisms driving these morphological alterations remain unclear, they serve as hallmark indicators of ferroptosis. The concept of iron-dependent cell death is not entirely novel. Prior to the formal identification of ferroptosis, numerous studies had already linked iron overload and oxidative stress to pathological cell death in neurodegenerative diseases and brain injury (21–23). Accumulating evidence indicates that many neurodegenerative diseases feature localized iron accumulation in specific regions of the central or peripheral nervous system. This iron deposition often results from altered cellular iron distribution, triggering Fenton chemistry and lipid peroxidation—processes tightly associated with the progression of neurological disease and accompanied by reductions in GSH and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) levels. Currently, therapeutic strategies targeting ferroptosis are rapidly evolving, including iron chelation, enhancement of antioxidant defenses, lipid metabolism modulation, and the development of specific small-molecule inhibitors. These approaches have demonstrated neuroprotective effects in various preclinical models, laying a foundation for future clinical translation.

However, the precise role of ferroptosis across different neurodegenerative conditions remains incompletely understood. A major challenge lies in developing targeted interventions that modulate ferroptosis without compromising essential physiological functions. To address this, this review summarizes recent advances in ferroptosis mechanisms and their roles in neurodegenerative diseases. Looking ahead, emerging technologies such as single-cell multi-omics, spatial transcriptomics, and organoid modeling offer unprecedented opportunities to dissect the complex regulatory networks linking ferroptosis to neurodegeneration. Ultimately, targeting ferroptosis may open new avenues for early diagnosis and precision therapy in neurodegenerative diseases, advancing the field toward more effective and individualized treatment paradigms.

2 Mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases are a group of age-related disorders characterized by highly heterogeneous pathogenesis and clinical manifestations, with progressive loss of vulnerable neurons and gradual decline in brain function (24). As irreversible disorders caused by the loss of neurons in the brain and spinal cord, recent studies have identified eight hallmarks of neurodegeneration: pathological protein aggregation, synaptic and neuronal network dysfunction, proteostasis imbalance, cytoskeletal abnormalities, altered energy homeostasis, DNA and RNA damage, inflammation, and neuronal cell death (25, 26). These findings highlight the necessity for multitargeted and personalized therapeutic approaches, offering new directions for drug discovery. Although these diseases exhibit distinct histopathological features, they may share common cellular and molecular mechanisms. Thus, identifying effective preventive strategies is crucial for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

2.1 Genetic factors in neurodegenerative diseases

Age remains a key risk factor for AD, which predominantly affects the elderly and causes significant burdens on daily living through progressive memory and learning deficits (4). Approximately 4%–8% of AD cases are influenced by genetic factors, leading to early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD) driven by mutations in genes such as APP and PSEN1 (25). These genes are involved in lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. For example, ALDH2 overexpression protects against APP/PSEN1 mutation-induced cardiac atrophy, contractile dysfunction, and mitochondrial damage by regulating PSEN1–ACSL4-mediated lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis (25, 26). PD is characterized by reduced dopamine levels and the presence of Lewy bodies. Studies show that single-gene mutations play a critical role in familial forms of PD. For instance, mutations in genes such as DJ-1 accelerate disease progression. In addition, patients with PD exhibit elevated lipid peroxidation, glutathione depletion, deficiencies in DJ-1 and coenzyme Q10, reduced glutathione peroxidase 4 activity, mitochondrial dysfunction, iron accumulation, and α-synuclein aggregation. Together, these features are closely associated with ferroptosis, indicating that ferroptosis contributes to the pathogenesis of PD (27, 28).

Furthermore, recent studies have shown that under stress from ferroptosis inducers, DJ-1 can significantly suppress ferroptosis. This protective effect occurs through the preservation of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase activity, which helps inhibit ferroptosis (28, 29).

2.2 Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative pathology

Mitochondria are central regulators of cellular respiration, metabolism, energy production, intracellular signaling, and free radical generation (10, 30). Accumulating evidence indicates that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a pivotal role in regulating cell death and aging, serving as a hallmark of neurodegeneration (31). In the central nervous system (CNS), the sufficient energy supply required for neuronal survival and excitability largely depends on mitochondrial function (32). In AD, mitochondrial defects represent one of the earliest and most recognized pathological features, particularly linked to impaired energy metabolism (33). Targeting mitochondrial pathways has shown promise in mitigating neurodegeneration and functional impairment, indicating that mitochondrial disruption accelerates AD progression. In Parkinson’s disease, mitochondrial dysfunction also plays a central role (34). Both familial and sporadic forms of PD involve mutations in mitochondrial-associated proteins—such as PINK1, Parkin, DJ-1, and α-synuclein. One of the most compelling pieces of evidence is the observed reduction in mitochondrial complex I activity in postmortem brains of PD patients, reinforcing mitochondrial involvement in PD pathology. This suggests that improving mitochondrial function may serve as a key strategy for slowing disease progression. In amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), mitochondrial impairments—including reduced ATP synthesis, altered axonal distribution, morphological changes, elevated ROS production, and respiratory chain defects—are associated with rapid disease progression (35). Morphological and biochemical mitochondrial abnormalities have also been confirmed in postmortem spinal cords of ALS patients, further supporting the central role of mitochondrial dysfunction in ALS pathogenesis (36). Similarly, in Huntington’s disease (HD), mitochondrial dysfunction leads to neuronal degeneration, contributing to disease onset and progression.

2.3 Relationship between oxidative stress and neurodegenerative disorders

With aging, redox imbalance develops alongside elevated levels of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). These changes contribute to regional neuronal dysfunction, memory impairment, and cognitive decline. Such findings support a close link between oxidative damage and neuronal injury (37, 38). AD, the most common neurodegenerative disorder among the elderly, involves multiple molecular events in its pathogenesis, with hallmark features including neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), senile plaques, and neuronal loss (39, 40). Several lines of evidence suggest that oxidative stress is a key driver of AD progression. In AD mouse models, peroxidase activity was shown to improve cognition and spatial memory while reducing Aβ plaque deposition in the cortex and hippocampus (41). In other neurodegenerative diseases, Parkinson’s disease is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder among individuals over 60 years of age (42–44). Dopaminergic neurons are especially susceptible to ROS-induced damage (45). The neurotoxin MPP+, a metabolite transported into dopaminergic neurons via the dopamine transporter, accumulates in the mitochondria and inhibits complex I activity of the electron transport chain, reducing ATP production and increasing ROS release, ultimately causing degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and striatum (46). Studies on PD mouse models have also demonstrated that DJ-1 plays a role in antioxidant defense (47). Mutations in several genes—including SOD1, TARDBP, FUS, UBQLN2, C9orf72, and TAF15—have been found in approximately 5% of ALS cases. Mutant SOD1 enhances ROS/RNS production, accelerating disease progression (48, 49). Huntington’s disease is considered a protein misfolding disorder, where excessive ROS production leads to abnormal protein folding and impaired neurotransmission. HD is also associated with disrupted mitochondrial morphology and function, resulting in energy deficiency and progressive neurodegeneration. Animal models of HD have revealed that when antioxidant capacity is compromised, mitochondrial function deteriorates (50), highlighting the role of oxidative stress in HD pathogenesis.

2.4 Relationship between aging and neurodegenerative diseases

Given the high prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases in older adults, aging is considered the primary risk factor for neurodegeneration (51). Due to the high metabolic and energetic demands of the brain, neurons are particularly prone to ROS overproduction, which damages brain tissue. This damage increases with age due to declining DNA repair capacity, emphasizing the importance of understanding aging mechanisms in developing interventions for neurodegenerative diseases (52). Currently, the most common neurodegenerative diseases—such as AD and PD—predominantly affect the elderly population. Cellular senescence in AD may be driven by increased DNA damage and reduced DNA repair capacity, which worsens with disease progression (53). Similarly, PD pathogenesis involves multiple pathways, including α-synuclein aggregation, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, calcium dysregulation, axonal transport defects, and neuroinflammation. At the cellular level, increased α-synuclein deposition correlates with cellular aging, evidenced by elevated numbers of senescent cells and increased β-galactosidase expression in postmortem PD brain tissues (54).

Beyond AD and PD, numerous other neurodegenerative diseases show strong associations with cellular senescence. For example, ALS presents both sporadic and familial forms, often linked to defective DNA repair, which leads to neuronal damage, premature aging, and subsequent neurodegeneration (55). Clinical evidence supports the view that DNA repair deficiencies drive neuronal aging and degeneration in ALS. In HD, age-related telomere attrition impairs transcriptional regulation, a process thought to underlie widespread neuronal death in HD (56). These observations reinforce the concept that aging is deeply intertwined with neurodegenerative processes. Therefore, future research should focus on the intersection between aging and neurodegeneration, potentially informing novel therapeutic strategies for these devastating conditions.

2.5 Ferroptosis in neurodegenerative pathogenesis

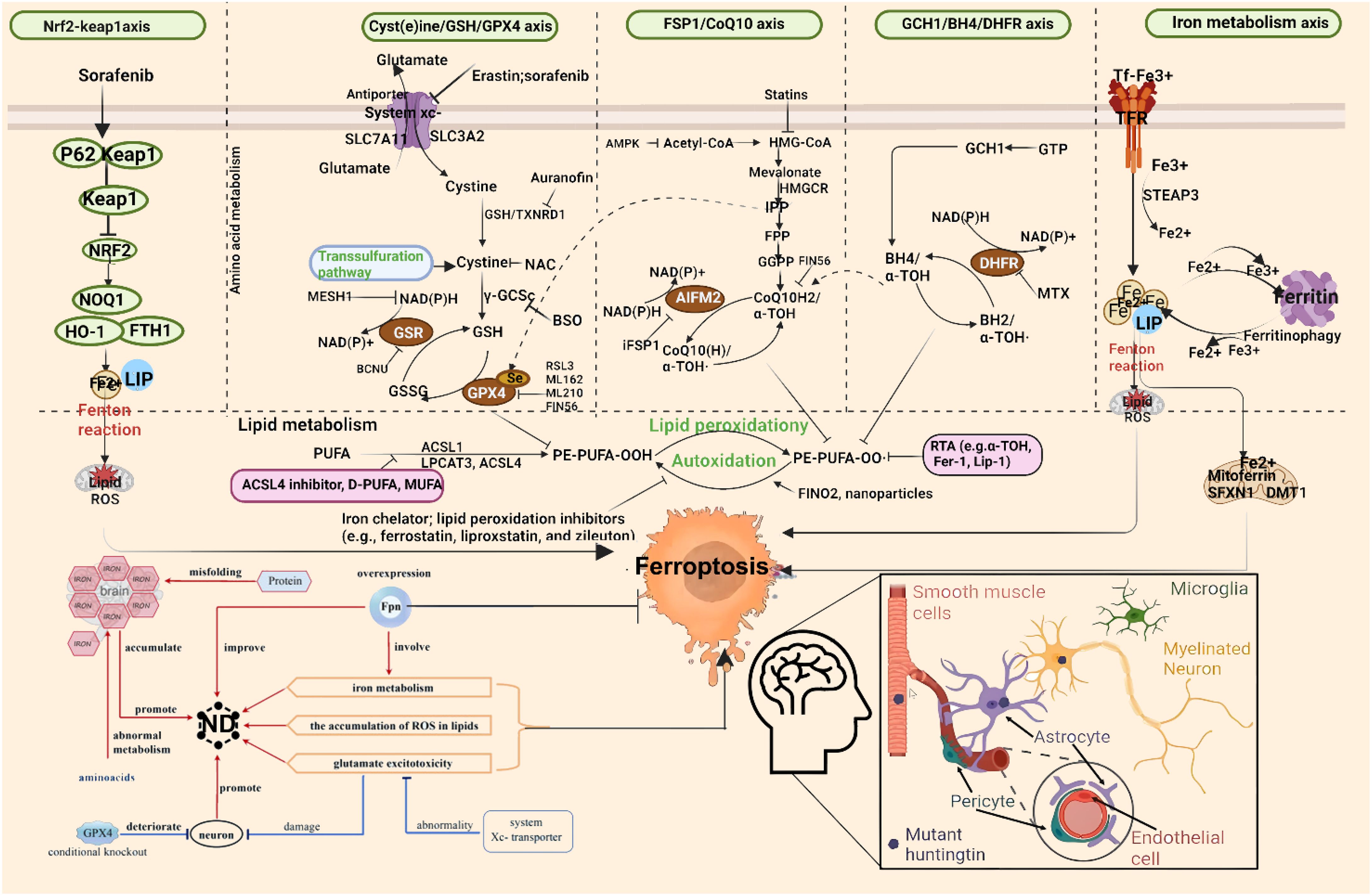

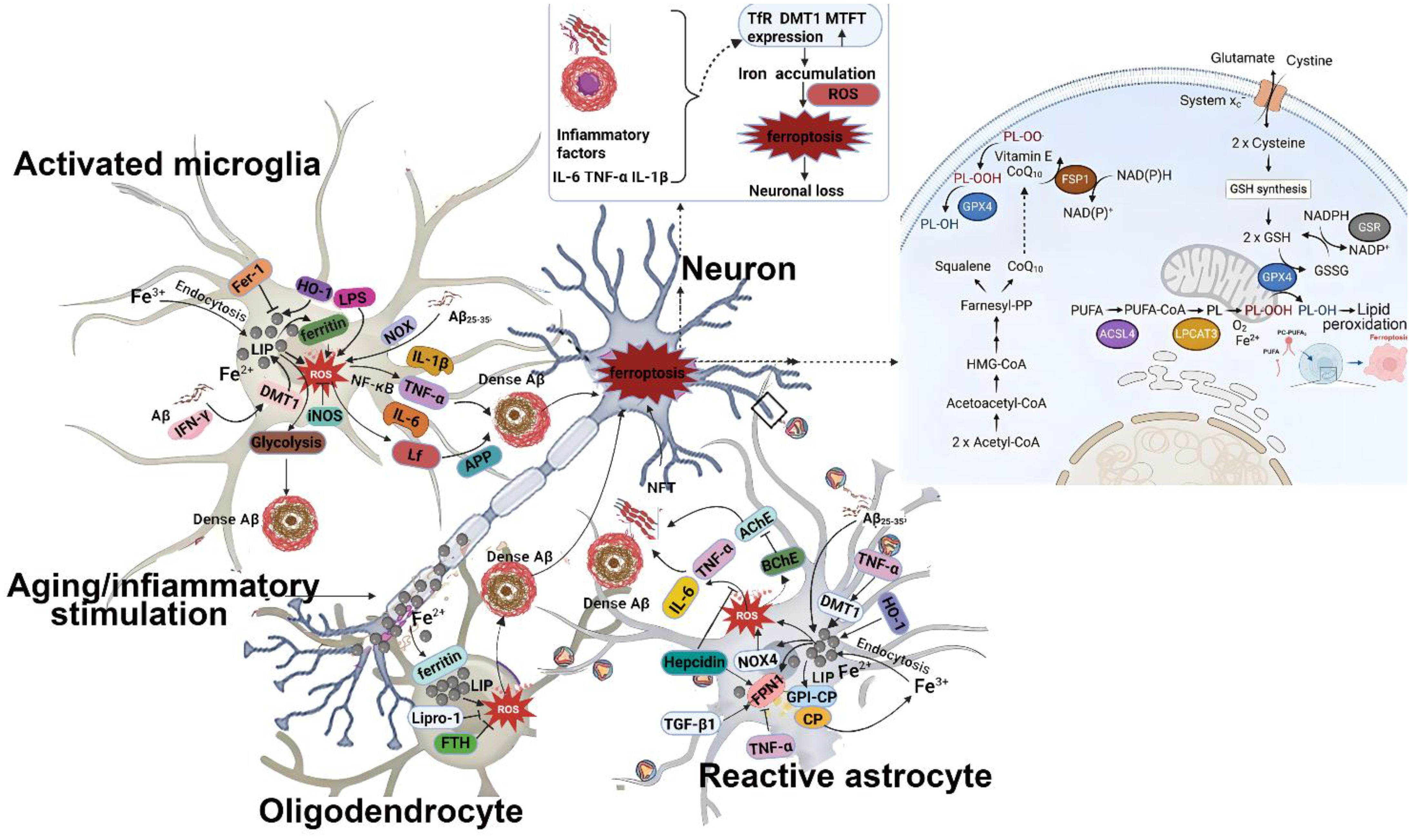

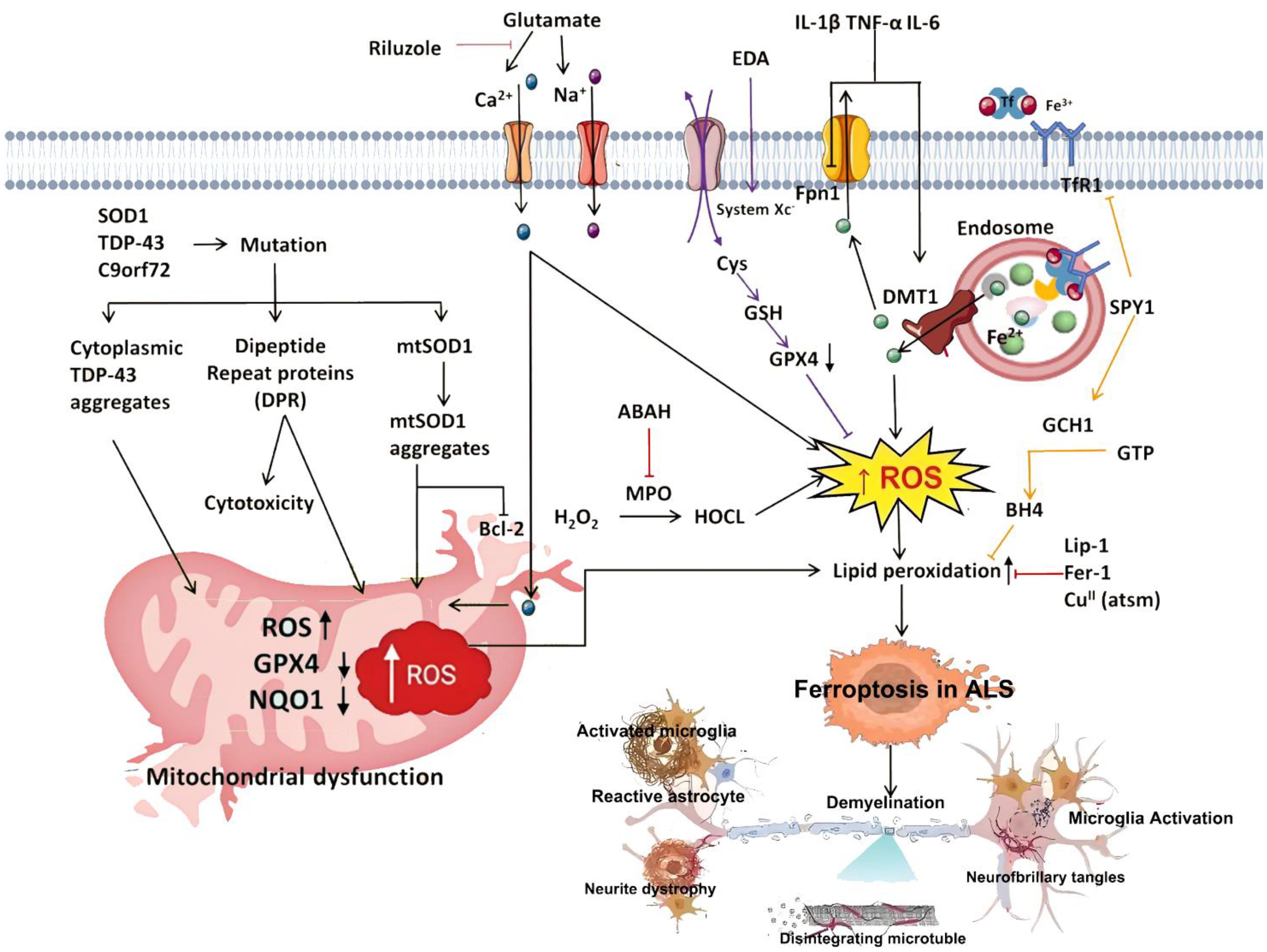

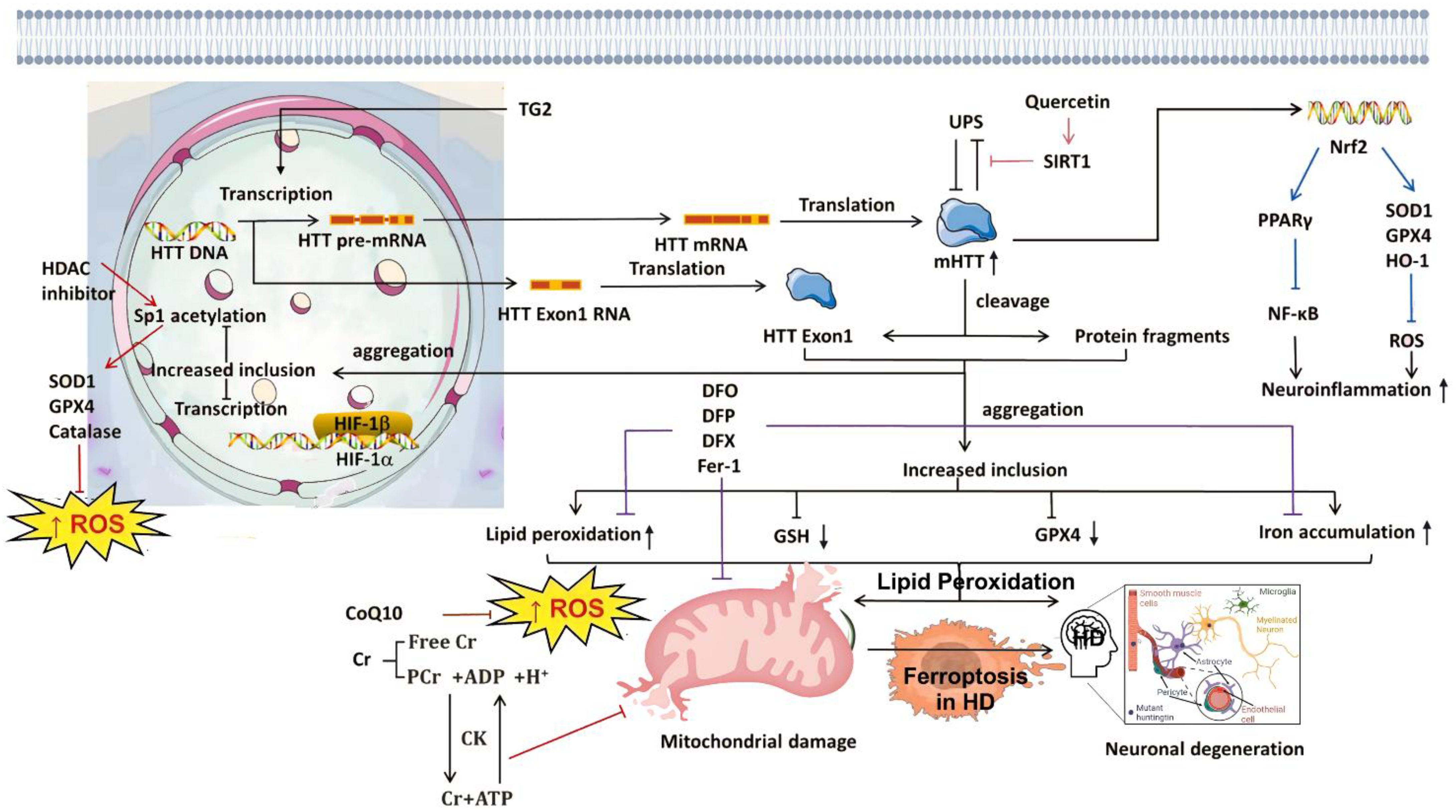

Iron is the most abundant transition metal in the human brain and participates in vital CNS functions such as mitochondrial energy transduction, enzymatic catalysis, myelination, synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmitter synthesis and degradation (57). Since the formal identification of ferroptosis, researchers have increasingly viewed it as a critical contributor to neuronal death in PD, AD, and HD (58). Animal models and anatomical studies in humans reveal varying degrees of iron accumulation in the aging brain, which may lead to age-dependent ferroptotic cell death. Long-term exposure to excess iron in mice disrupts membrane transporter function and intracellular iron homeostasis, elevating ROS and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, ultimately triggering neuronal death (59). These findings underscore the critical role of cerebral iron content in linking neurodegenerative diseases and ferroptosis. For instance, Alzheimer’s disease, the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder, is characterized by NFTs. Studies have reported correlations between brain iron and ferritin levels and the extent of amyloid-beta deposition (60). These observations suggest that ferroptosis may play a central role in AD pathogenesis, warranting deeper investigation. In Parkinson’s disease, neuropathological hallmarks include the loss of catecholaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus. Clinically, iron levels in the substantia nigra are significantly higher in PD patients compared to controls (61). Moreover, selective depletion of glutathione (GSH) is a defining feature of PD, aligning with the core characteristics of ferroptosis (62) and implicating ferroptosis as a potential driver of dopaminergic neuron loss. In Huntington’s disease, GSH dysregulation, iron overload, and lipid peroxidation are commonly observed in HD patients. However, administration of the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 has been shown to suppress lipid peroxidation, restore GSH levels, reduce iron accumulation, and markedly attenuate neuronal death (63), suggesting that targeting ferroptosis could provide therapeutic benefits in HD. The mechanism of ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases. From left to right: The diagram illustrates ferroptosis mechanisms induced by distinct regulatory pathways. The classical regulatory pathway is shown in the first column on the left: cystine is imported into the cell via the system Xc− and subsequently reduced to cysteine through either the GSH-dependent or TXNRD1-dependent pathway, promoting GSH synthesis. GSR catalyzes the reduction of GSSG to GSH using electrons provided by NADPH/H+. The second column highlights the FSP1/CoQ10 axis. This pathway has been shown to protect cells from ferroptosis induced by either pharmacological inhibition or genetic deletion of GPX4. Unlike the GPX4/GSH pathway, FSP1 exerts its protective effect through coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) and α-tocopherol. The rightmost column summarizes additional mechanisms involved in ferroptosis suppression. GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; GSH, glutathione; TXNRD1, thioredoxin reductase 1; GSR, glutathione reductase; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; FSP1, ferroptosis suppressor protein 1; SLC7A11, solute carrier family 7 member 11; SLC40A1, solute carrier family 40 member 1.

Despite significant challenges in managing neurodegenerative diseases, advances in mechanistic understanding are rapidly emerging. As outlined above, multiple interconnected mechanisms—including genetic predispositions, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, aging, and ferroptosis—converge in driving neurodegenerative pathology. However, our comprehension of the full complexity underlying these diseases remains incomplete. Beyond the discussed mechanisms, neurodegeneration may also involve inflammatory responses, energy metabolism defects, endoplasmic reticulum stress, immune dysfunction, and viral infection. Further in-depth exploration of these interwoven mechanisms, supported by modern experimental technologies and multidisciplinary integration, will be essential to uncover robust strategies for the prevention and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Such efforts hold the potential to transform current therapeutic paradigms, offering hope for precision medicine in the fight against neurodegeneration.

3 Ferroptosis: characteristics and molecular mechanisms

In recent years, ferroptosis, a newly identified form of regulated cell death, has emerged as a distinct mechanism characterized by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation and morphologically distinct from other modes of cell death (64, 65). Ferroptosis is closely associated with various human diseases, including cancer, aging-related disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and ischemia–reperfusion injury (66–68). For instance, ferroptosis inducers such as sulfasalazine and erastin have been shown to significantly inhibit tumor cell proliferation (69), highlighting their therapeutic potential. 1) Morphological features of ferroptosis: The morphological hallmarks of ferroptosis include loss of plasma membrane integrity, cytoplasmic and organelle swelling, chromatin condensation, and increased cellular detachment and aggregation (70). Notably, the mitochondria exhibit characteristic changes such as shrinkage, increased membrane density, reduction or disappearance of cristae, and outer membrane rupture (71). These structural alterations differentiate ferroptosis from other types of cell death such as apoptosis or necrosis. 2) Biochemical features of ferroptosis: Ferroptosis is biochemically defined by the accumulation of ROS, iron overload, and lipid peroxidation (72). Under normal conditions, cells maintain redox balance through antioxidant systems. However, when these defenses are compromised, excess Fe²+ mediates Fenton reactions that generate hydroxyl radicals—highly reactive species that oxidize polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in phospholipids. This oxidative damage destabilizes the lipid bilayer, leading to membrane breakdown and ultimately triggering ferroptosis (72). Differences between ferroptosis and other types of programmed cell death are shown in Table 1.

3.1 Molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis

Ferroptosis is intricately linked to intracellular metabolism involving amino acids, lipids, and iron. Additional metabolic pathways and regulatory factors also influence cellular susceptibility to ferroptosis.

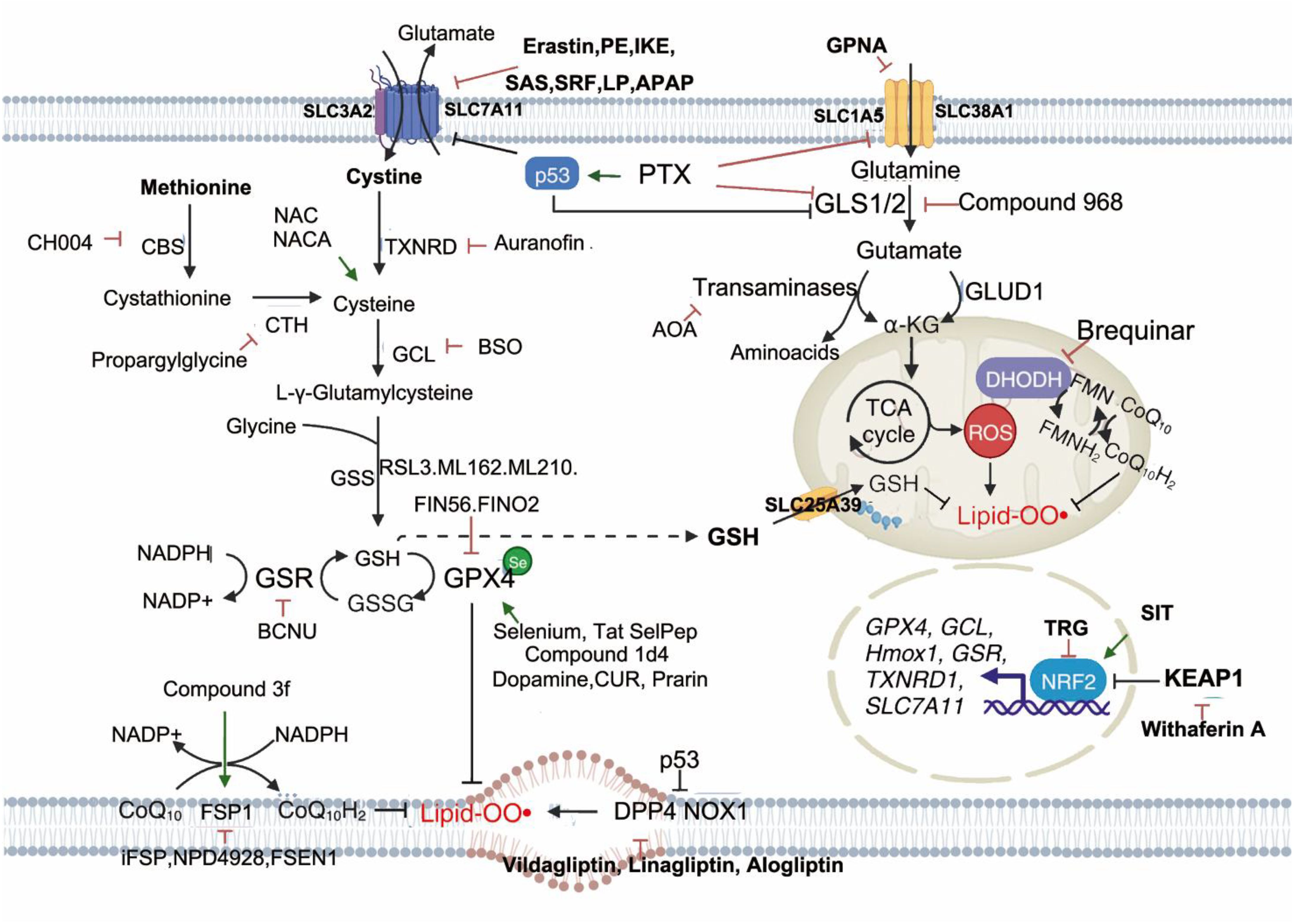

3.1.1 Relationship between amino acid metabolism and ferroptosis

The system Xc−, a cystine/glutamate antiporter located on the cell membrane, consists of the light chain SLC7A11 and heavy chain SLC3A2, linked via disulfide bonds. This system mediates a 1:1 exchange of extracellular cystine for intracellular glutamate, enabling cystine uptake and subsequent conversion into L-cysteine, which is used for the synthesis of GSH (73). GPX4 serves as a key enzyme in the antioxidant defense system. Utilizing GSH as a cofactor, GPX4 catalyzes the reduction of lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) to non-reactive lipid alcohols, thereby suppressing ferroptosis.

Erastin and RAS-selective lethal small molecule 3 (RSL3) are well-established ferroptosis inducers (74). Erastin binds to SLC7A11 and inhibits its function, impairing cystine import and reducing GSH synthesis. This leads to the accumulation of lipid ROS and subsequent membrane damage, culminating in ferroptotic cell death (75). Additionally, erastin disrupts mitochondrial membranes by targeting voltage-dependent anion channels (VDACs), causing intracellular release of reactive species and further promoting cell death (76). In contrast, RSL3 directly covalently binds to GPX4, rendering it inactive and disrupting the redox balance. This results in elevated lipid peroxidation and induction of ferroptosis (77).

Transcription factors regulate SLC7A11 expression and thus modulate ferroptosis. The transcription factor NFE2L2 (Nrf2) positively regulates SLC7A11 expression, whereas tumor suppressors such as TP53, BAP1, and BECN1 downregulate SLC7A11, increasing ferroptosis sensitivity (78–80). Therefore, targeting GSH metabolism represents a promising avenue for modulating ferroptosis in disease contexts.

3.1.2 Relationship between lipid metabolism and ferroptosis

PUFAs, particularly those containing bis-allylic hydrogen atoms such as arachidonate (AA) and adrenate (AdA), are highly susceptible to oxidation by ROS, making them central to ferroptosis (81). Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) enriched in AA or AdA serve as critical substrates for lipid peroxidation during ferroptosis. Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) catalyzes the conjugation of free AA or AdA with coenzyme A (CoA) to form AA-CoA or AdA-CoA. These derivatives are subsequently esterified into membrane PEs by lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) (82). Thus, enhancing PUFA availability increases ferroptosis susceptibility, while inhibition of ACSL4 or LPCAT3 suppresses ferroptosis (83). The generation of CoA-conjugated PUFAs and their incorporation into phospholipids represent key steps in ferroptosis signaling, offering potential therapeutic targets for diseases associated with this mode of cell death.

Lipoxygenases (LOXs), iron-containing enzymes, play a direct role in inducing ferroptosis by catalyzing the peroxidation of membrane-bound PUFAs. In p53-mediated ferroptosis, p53 activates arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase (ALOX12), triggering ferroptosis independently of GPX4 activity (84). Targeting ALOX12—either pharmacologically or genetically—represents a novel strategy for preventing ferroptotic neuronal injury (85).

3.1.3 Relationship between iron metabolism and ferroptosis

Iron exists in two major oxidation states: Fe²+ and Fe³+. Dietary Fe³+ is reduced to Fe²+ in the gastrointestinal tract before being absorbed by intestinal epithelial cells (86). Within cells, Fe²+ is exported via the iron transporter ferroportin 1 (FPN1) and oxidized to Fe³+ by multicopper oxidases. Fe³+ then binds to transferrin (TF) to form the TF-Fe³+ complex, which circulates and delivers iron to various tissues (87). Upon binding to transferrin receptor (TfR1) at the cell surface, TF-Fe³+ enters the cell via endocytosis. Intracellular STEAP3, a metalloreductase, reduces Fe³+ to Fe²+, which is then released into the labile iron pool (LIP) through the action of divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) (87). Under physiological conditions, the LIP maintains iron homeostasis. However, under pathological conditions, excessive Fe²+ drives the Haber–Weiss and Fenton reactions, producing high levels of ROS. These radicals initiate lipid peroxidation of PUFAs within membrane phospholipids, leading to membrane disruption and ferroptosis (88). Moreover, Fe²+ functions as a cofactor for multiple metabolic enzymes—including LOXs and PDH1—enhancing their activity and further stimulating ROS production (89). Therefore, components of iron metabolism represent potential therapeutic targets in ferroptosis regulation. The tumor suppressor OTUD1 interacts with and promotes deubiquitination of IREB2 (iron-responsive element-binding protein 2), stabilizing IREB2 and activating downstream TFRC gene expression. This enhances Fe²+ influx, elevates ROS levels, and increases cellular sensitivity to ferroptosis. Knockdown of IREB2 reduces ferroptosis susceptibility (90, 91). Furthermore, studies suggest that inhibition of transferrin (TF) activity can reduce Fenton reaction-driven ROS accumulation and lipid peroxidation, thereby attenuating ferroptosis (90). Deferoxamine (DFO), an iron chelator, prevents ferroptosis caused by iron overload, and limiting iron intake can slow liver injury induced by ferroptosis (92). Despite these findings, the precise mechanisms linking iron metabolism to ferroptosis remain incompletely understood and warrant further investigation.

3.1.4 Redox stress-metabolic pathways regulating ferroptosis

Additional regulators of ferroptosis include coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), NADPH, selenium, p53, NRF2/NFE2L2, and vitamin E. Among these, CoQ10, when reduced by ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1), acts to prevent lipid oxidation and suppress ferroptosis (93). This suggests that FSP1 may serve as a promising therapeutic target in diseases involving ferroptosis. NADPH plays a crucial role in the regeneration of the GSH–GPX4 axis. Depletion of NADPH compromises antioxidant capacity, tipping the redox balance toward ferroptosis (94, 95). Selenium, an essential trace nutrient, contributes to GPX4 stability and enzymatic activity by cooperating with transcription factors TFAP2c and Sp1, exerting protective effects against ferroptosis in neurons (96). The NFE2L2 (Nrf2) pathway constitutes a key cellular defense against ferroptosis. NFE2L2 transactivates multiple genes involved in iron and GSH metabolism, as well as ROS detoxification, thereby limiting oxidative damage (67). As a major endogenous antioxidant, vitamin E protects cell membranes from lipid peroxidation. Studies show that vitamin E synergizes with GPX4 to suppress ferroptosis by inhibiting lipoxygenase (ALOX) activity and reducing lipid peroxide formation (97). Thus, vitamin E holds therapeutic promise as a ferroptosis-targeted intervention. Transcription factors p53 and NRF2 also play significant roles in ferroptosis. Although p53’s involvement in various forms of cell death has been studied for over two decades, its role in ferroptosis was only recently uncovered (98). p53 induces ferroptosis by repressing SLC7A11 expression and blocking cystine uptake. Nutlin-3, an inhibitor of murine double minute 2 (MDM2), enhances p53 stability and preserves intracellular GSH levels via a p53-dependent mechanism, allowing cell survival under cystine-deprived conditions (98). Conversely, p53 can inhibit dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4), counteracting erastin-induced ferroptosis. Loss of p53 promotes DPP4–NADPH oxidase 1 (NOX1) interactions, forming a NOX1–DPP4 complex that mediates plasma membrane lipid peroxidation and triggers ferroptosis (78). NRF2 (also known as NFE2L2) is a central regulator of redox homeostasis. Through the p62–Keap1–NRF2 pathway, NRF2 upregulates the expression of genes involved in iron and ROS metabolism, such as NQO1, HO1, and FTH1, thereby suppressing ferroptosis (99). Evidence also indicates that SLC7A11 is a transcriptional target of NRF2, suggesting that SLC7A11 may mediate the protective effects of NRF2. Further studies are required to validate this interaction (99).

3.2 Regulatory mechanisms of ferroptosis

As research progresses, scientists have uncovered a complex and finely tuned regulatory network governing ferroptosis, involving both inhibitory and activatory pathways, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Pathways regulating ferroptosis. Different molecules regulate lipid peroxidation in multiple ways. BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin; GCH1, recombinant GTP cyclohydrolase 1; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; FSP1: ferroptosis-suppressor protein-1.

3.2.1 Inhibitory pathways of ferroptosis

The ferroptosis-inhibiting mechanisms include the classical GSH–GPX4 axis and several GPX4-independent pathways (100). 1) GSH–GPX4 antioxidant system in the cytosol and mitochondria: One of the most critical defenses against ferroptosis is the GSH–GPX4 system located in both the cytosol and mitochondria (101). On the cell membrane, the cystine/glutamate antiporter SLC7A11/SLC3A2—also known as system Xc−—transports extracellular cystine into the cell in a 1:1 exchange with intracellular glutamate release (101). Once inside the cell, cystine is reduced to L-cysteine, which is then used by glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL) and glutathione synthetase (GSS) to synthesize GSH, with NADPH serving as a key reducing cofactor. Finally, GPX4 utilizes GSH to reduce lipid hydroperoxides into non-reactive lipid alcohols, thereby suppressing ferroptosis (102). 2) GPX4-independent ferroptosis suppression—FSP1–CoQ10 pathway: Myristoylated ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1), also known as apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondrial 2 (AIFM2), resides on the plasma membrane and functions as a CoQ10 reductase. It plays a pivotal role in capturing lipophilic radicals and preventing lipid peroxide formation (103, 104). 3) GPX4-independent ferroptosis suppression—GCH1–BH4 pathway: GTP cyclohydrolase I (GCH1) and its metabolite tetrahydrobiopterin/dihydrobiopterin (BH4/BH2) protect cells from ferroptosis by selectively inhibiting the consumption of phospholipids containing two polyunsaturated acyl chains (105, 106). 4) GPX4-independent ferroptosis suppression—DHODH–CoQ10H2 pathway in the mitochondria: Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH), a flavin-dependent enzyme localized to the mitochondrial inner membrane, catalyzes the fourth step of pyrimidine biosynthesis—converting dihydroorotate (DHO) to orotate (OA)—while transferring electrons to mitochondrial ubiquinone, reducing it to CoQ10H2, which acts as a radical-trapping antioxidant (107). Studies show that under conditions of low GPX4 expression, DHODH effectively suppresses mitochondrial lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. However, when GPX4 levels are high, combining system Xc− inhibitors such as sulfasalazine with DHODH inhibitors can synergistically induce ferroptosis (107).

3.2.2 Activating pathways of ferroptosis

Lipid peroxidation serves as the final execution mechanism of ferroptosis. The synthesis of free fatty acids via acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACAC) or their liberation through lipophagy leads to intracellular accumulation of free fatty acids, promoting ferroptosis (108). Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase family member 4 (ACSL4) facilitates the incorporation of PUFAs, including arachidonate and adrenate, into cellular membranes (82). These PUFAs are subsequently esterified into phospholipids by lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3), generating PUFA-phospholipids (PUFA-PLs) that are highly susceptible to oxidation by lipoxygenases (ALOXs), ultimately leading to ferroptosis (109, 110). Iron availability is a defining feature of ferroptosis. Fe²+ drives the Fenton reaction, producing unstable hydroxyl radicals that initiate lipid oxidation of PUFAs, forming conjugated dienes and eventually yielding toxic lipid peroxidation products such as 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and MDA. These molecules increase membrane fragility, impair cellular function, and promote ferroptotic death (91, 111). Several key genes in iron metabolism that regulate ferroptosis were identified, including transferrin and SLC39A14 iron transporters (112), the heavy chain of ferritin (FTH1) (113, 114), as well as TFR1 (115), FPN1 (116, 117), PCBP1 (118), and NCOA4 (119)—all reported to modulate ferroptosis through iron homeostasis. These findings highlight the central role of iron metabolism in ferroptosis regulation and underscore the need for further mechanistic exploration.

3.3 Pharmacological modulation of ferroptosis

Both inducers and inhibitors of ferroptosis have emerged as potential therapeutic agents, targeting different nodes along the ferroptotic pathway.

3.3.1 Ferroptosis inducers

Small molecules targeting iron metabolism: Erastin was first identified in 2003 as a genetically selective antitumor agent that induces ferroptosis primarily through interaction with VDACs (76, 120). Another compound, RSL5, binds VDAC3 and similarly triggers ferroptosis. VDACs can be allosterically blocked by 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS), a small-molecule inhibitor of mitochondrial anion channels. Temozolomide (TMZ), an anticancer drug used in glioblastoma treatment, enhances DMT1 activity and promotes ferroptosis. A recently discovered ferroptosis inducer, MMRi62, induces degradation of the ferritin heavy chain (120).

Small molecules targeting lipid metabolism: The antitumor agent sorafenib, in the presence of ACSL4, activates ferroptosis by directly affecting lipid ROS generation pathways (121). Similarly, tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BuOOH) increases lipid ROS production, inducing oxidative stress, mitochondrial depolarization, and DNA damage. t-BuOOH exerts its effect through cardiolipin oxidation, and this process can be reversed by cardiolipin oxidation inhibitors such as XJB-5–131 and JP4–039 (121).

Small molecules targeting the GSH/GPX4 axis: RSL3 and RSL5, although functionally distinct, were among the earliest identified GPX4-targeted ferroptosis inducers. RSL3 covalently binds to the active site of GPX4, inactivating its enzymatic function (77). Other compounds, such as ML162, DPI7, and DPI10, exhibit similar effects. Additionally, FIN56 accelerates GPX4 degradation, promoting ferroptosis. Besides erastin and its analogs, several FDA-approved drugs have been shown to inhibit the system Xc−. For example, sulfasalazine (SAS) suppresses system Xc− and exhibits antitumor properties. Sorafenib indirectly inhibits system Xc− by blocking upstream regulators and also reduces GPX4 activity. iv) Small molecules targeting the FSP1/CoQ pathway: In addition to erastin, FIN56 is another multimodal inducer of ferroptosis. FIN56 not only promotes GPX4 degradation but also binds squalene synthase (SQS) and depletes CoQ, thereby triggering ferroptosis (122). NDP4928, a specific FSP1 inhibitor, sensitizes cells to GSH depletion by binding and inhibiting FSP1. Statins, formulated as therapeutic nanoparticles, block HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR) in the mevalonate pathway, thereby reducing CoQ levels and promoting ferroptosis (122).

3.3.2 Ferroptosis inhibitors

Iron-lowering agents: Ciclopirox olamine (CPX) is an iron chelator with broad-spectrum antifungal and antibacterial activity. Beyond its chelating capacity, CPX-O has been shown to induce ferritin degradation in polycystic kidney disease mouse models (123, 124). DFO is a widely used iron chelator that has demonstrated efficacy in traumatic spinal cord injury. Additional iron chelators such as deferiprone (DFP) and deferasirox (DFX) have also been reported to inhibit ferroptosis (124).

Lipid peroxidation inhibitors: Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) suppresses lipid peroxidation and rescues p53-driven ferroptosis (125). α-Tocopherol (vitamin E) and structurally related analogs of Fer-1 share similar protective functions, though with variable efficacy and stability. Recent studies have identified vitamin K hydroquinone (VKH2), the fully reduced form of vitamin K, as a potent inhibitor of lipid oxidation and ferroptosis. iii) Modulators of the GSH/GPX4 axis: Small molecules such as β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) prevent ferroptosis by stabilizing redox balance (126). Selenium (Se) supplementation enhances GPX4 expression, offering protection against ferroptotic insults. In short, the development of ferroptosis inducers and inhibitors is essential for dissecting the molecular basis of this unique form of regulated cell death. As new targets and pathways continue to emerge, they provide a foundation for developing novel therapeutics across a spectrum of diseases where ferroptosis plays a pathogenic role, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and ischemia–reperfusion injury.

4 Ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases: mechanistic insights

Ferroptosis is a regulated form of cell death driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, and mounting evidence suggests its involvement in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, including ischemic stroke, PD, AD, and HD (127). The mechanisms underlying ferroptosis—such as iron overload, lipid metabolism dysregulation, and antioxidant defense failure—are increasingly recognized as key contributors to neuronal loss and functional deterioration in these disorders. This section will discuss classical neurodegenerative diseases (such as AD, PD, HD, and ALS), as well as other acute and chronic neurological disorders known to involve ferroptosis, including ischemic stroke, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and Friedreich’s ataxia (FRDA).

4.1 Ferroptosis in cerebral ischemia

Stroke, also known as cerebral ischemia, is a leading cause of global mortality and disability. According to the GBD 2021 study published in The Lancet Neurology, 11.9 million individuals experienced their first stroke in 2021, resulting in 7.25 million deaths and 160 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (127). Stroke ranks as the third leading cause of death and the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide (127). Ischemic stroke occurs when blood flow to specific brain regions is restricted due to occlusion of the middle cerebral artery, vertebral/basilar artery, or internal carotid artery (128). This deprivation of oxygen and nutrients activates an ischemic cascade, leading to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and ultimately neuronal death (129). Ferroptosis has emerged as a major mechanism of neuronal death in this context, with studies showing that inhibition of ferroptosis can prevent ischemia/reperfusion injury (130–151). In the middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model, mice treated with ferroptosis inhibitors exhibit reduced brain damage, indicating that ferroptosis contributes significantly to post-ischemic neuronal death. Notably, tau knockout mice are resistant to ferroptotic cell death following reperfusion, suggesting that the tau–iron interaction serves as a pleiotropic modulator of ferroptosis and ischemic stroke progression (130). Current understanding attributes ferroptosis in ischemic stroke to several factors, including intracellular iron accumulation, lipoxygenase activation, GSH depletion, GPX4 inactivation, and system Xc− disruption (130) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Summary of the mechanisms of ferroptosis in cerebral ischemia. Following cerebral ischemia, energy depletion impairs the clearance of excitatory neurotransmitters from the synaptic cleft, leading to the accumulation of glutamate and other excitatory signals. This excess glutamate activates AMPA receptors, promoting Na+ influx into neurons. Elevated intracellular Na+ levels trigger the conversion of prothrombin into active thrombin, which in turn induces phosphorylation and activation of calcium-dependent cPLA2α. Additionally, thrombin from the bloodstream may enter the brain through a compromised blood–brain barrier, further activating cPLA2α by increasing cytosolic Ca²+ concentrations. Activated cPLA2α hydrolyzes membrane phospholipids at the sn-2 position to release AA. AA is then converted to AA-CoA by ACSL4 and subsequently incorporated into membrane phospholipids via LPCAT3, forming PL-AA. Under the catalytic action of ALOX15 and the Fenton reaction, PL-AA undergoes peroxidation, generating bioactive lipid peroxides that contribute to ferroptosis. GPX4 normally reduces LOOH to non-toxic LOH. However, elevated extracellular glutamate inhibits cystine uptake, limiting GSH synthesis. This depletion of GSH inactivates GPX4, leading to the accumulation of toxic lipid peroxides and promoting ferroptosis. Moreover, ischemia-induced reduction in soluble tau protein impairs the transport of APP to the neuronal membrane. This disruption inhibits the interaction between APP and Fpn, blocking Fe²+ export and resulting in intracellular Fe²+ accumulation and iron-dependent cell death. cPLA2α, cytosolic phospholipase A2α; AA, arachidonic acid; ACSL4, acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; LPCAT3, lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3; PL-AA, AA-containing phospholipids; ALOX15, arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; LOOH, lipid peroxides; LOH, lipid alcohols; GSH, glutathione; APP, amyloid precursor protein; Fpn, ferroportin.

4.1.1 Role of iron metabolism in ischemic stroke

Prior to the formal identification of ferroptosis, studies had already linked iron accumulation to neuronal damage in both clinical settings and animal models of cerebral ischemia (35, 36, 131). Excessive iron exacerbates mitochondrial oxidative damage and enlarges infarct size (19, 37, 132). In children, increased iron deposition is observed in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and periventricular white matter after severe hypoxic–ischemic injury (25, 130), reinforcing the role of disrupted iron homeostasis in ferroptosis and stroke pathology. Iron overload following ischemia may be mediated through two primary pathways: IL-6–JAK/STAT3–hepcidin axis: Ischemia-induced IL-6 activates the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway, which enhances hepcidin expression. Elevated hepcidin downregulates FPN1, impairing iron export and promoting cellular iron retention and subsequent ferroptosis (133). However, the precise mechanisms driving IL-6 upregulation during ischemia remain incompletely understood. HIF-1α–TFR1 axis: Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) is upregulated during ischemia, enhancing transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1) expression. Since TFR1 mediates the main route of iron entry into neurons via the Tf-TFR1 complex, HIF-1α-dependent TFR1 induction leads to iron influx and overload within neurons (134). These findings highlight the central role of iron dyshomeostasis in the pathophysiology of ischemic stroke and suggest that targeting iron metabolism could represent a viable therapeutic strategy.

4.1.2 Role of lipid metabolism in ischemic stroke

Studies indicate that ACSL4 is overexpressed after cerebral ischemia and contributes to reperfusion injury (135). miR-347 has been implicated in ACSL4 regulation, with elevated miR-347 levels observed in stroke patients correlating with increased ACSL4 expression (135). Conversely, other studies report decreased ACSL4 levels in the hippocampus of MCAO rats after reperfusion, coinciding with elevated thrombin activity. This downregulation appears to be an early event independent of neuronal death, potentially mediated by thrombin-induced ACSL4 degradation and ferroptosis promotion (136). Downregulation of ACSL4 may thus serve as a protective mechanism against ferroptosis during reperfusion. Further research confirms that ACSL4 suppression in early ischemic stages is time-dependent and likely driven by increased HIF-1α, which binds to the ACSL4 promoter and suppresses its expression (137). Lipoxygenases (LOXs), particularly 12/15-LOX, play a pivotal role in ferroptosis-mediated injury. These enzymes not only induce neuronal damage but also promote nuclear translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) (138, 139). Inhibition of 12/15-LOX reduces neuronal and vascular injury following stroke (140). 5-LOX overexpression exacerbates inflammation and neuronal damage after ischemia/reperfusion (I/R). Conversely, miR-193b-3p, which targets 5-LOX, exerts neuroprotective effects in I/R injury, identifying it as a potential therapeutic target (141, 142).

4.1.3 Role of amino acid metabolism in ischemic stroke

Selenium activates transcription factors such as Sp1 and TFAP2c, thereby enhancing GPX4 expression and inhibiting ferroptosis (143, 144). Experimental models show that GPX4 overexpression alleviates cerebral injury after stroke, whereas GPX4 deletion exacerbates infarction (145). The cystine/glutamate antiporter system Xc−, composed of SLC7A11 and SLC3A2, supports GSH synthesis and maintains redox homeostasis (146). Under normal conditions, this system facilitates cystine uptake and glutamate efflux in a non-ATP-dependent manner. During stroke, however, elevated extracellular glutamate causes excitotoxicity, blocking system Xc− function and reducing GSH synthesis, thereby triggering ferroptosis (147). Impaired system Xc− activity has been linked to xCT subunit inactivation (148), which sustains glutamate excitotoxicity in rat models of cerebral ischemia (149). At high concentrations, system Xc− may paradoxically enhance glutamate toxicity and ferroptosis. The exact contribution of system Xc− to ferroptosis in human stroke remains to be fully elucidated.

4.1.4 Therapeutic targeting of ferroptosis in ischemic stroke

The primary goal in treating ischemic stroke is rapid reperfusion, a prerequisite for effective neuroprotection. Currently, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is the only FDA-approved thrombolytic agent for acute ischemic stroke (149). Despite ongoing efforts, most neuroprotectants have failed to demonstrate significant benefits in clinical trials, underscoring the need for novel mechanistic approaches. Iron chelators offer a promising avenue for intervention. DFO, an FDA-approved iron chelator, effectively reduces hydroxyl radical generation and attenuates brain injury in experimental stroke models (150, 151). Although DFO shows preclinical efficacy, its clinical translation remains limited, necessitating further evaluation of safety and effectiveness in stroke patients. Small-molecule ferroptosis inhibitors such as Fer-1 and liproxstatin-1 (Lip-1) inhibit ferroptosis induced by system Xc− blockade or GPX4 loss (130). Delayed administration of Lip-1 (6 h post-reperfusion) still provides neuroprotection by preventing sustained neuronal damage (25, 130). Intranasal delivery of Fer-1 improves neurological deficits and reduces infarct volume 24 h after MCAO (25, 130). Recent advances have led to the development of new ferroptosis inhibitors, including phenothiazine derivatives, which exhibit potent neuroprotective effects in ischemic stroke models (152). These compounds act similarly to classical antioxidants by capturing reactive radicals, offering a novel approach to lipid peroxidation suppression.

Upregulating GPX4 represents another promising therapeutic strategy. Cysteamine, a cystamine derivative, elevates GSH levels in cortical neurons and protects against ferroptosis (153). In animal models, cystamine reduces infarct volume and promotes recovery (154). Selenium-based interventions also activate protective gene expression programs that enhance GPX4 and counteract excitotoxicity and ER stress-induced neuronal death (155). Additionally, cystamine and ornithine-threonine-cysteine (OTC), a cysteine prodrug, protect neurons from oxygen–glucose deprivation (OGD)-induced death by increasing GSH levels in the penumbra after reperfusion, demonstrating neuroprotection (156). Moreover, lipid ROS sensors such as Liperfluo provide real-time assessment of lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis, enabling dynamic monitoring of redox status in ischemic brain tissues (16). These tools support the development of lipid-targeted therapies for stroke. Selective 5-LOX inhibitors like zileuton reduce leukotriene production and dampen inflammatory responses during reperfusion (157). In transient global cerebral ischemia models, zileuton lowers inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (158), and in MCAO rats, it improves neurological outcomes and reduces infarct volume compared to controls (159). While zileuton demonstrates neuroprotective properties in animal models, direct evidence linking its effects to ferroptosis inhibition remains lacking. In contrast, 12/15-LOX has been directly implicated in ferroptosis-driven neuronal injury. siRNA-mediated knockdown of 12/15-LOX confers resistance to ferroptosis in vitro and protects neurons in ischemic mouse models (160). Pharmacological inhibition of 12/15-LOX using agents such as ML351, LOXBlock-1, and BW-B70C significantly reduces infarct volume and mitigates poststroke brain damage (161–163). These findings position 12/15-LOX as a critical mediator of ferroptosis in ischemic stroke and a promising drug target for neuroprotection.

4.1.5 Natural compounds and traditional Chinese medicine targeting ferroptosis in ischemic stroke

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) categorizes ischemic stroke under “Zhong Feng” (中风), with acupuncture, herbal extracts, and compound formulations playing integral roles in treatment. Accumulating evidence suggests that TCM interventions exert neuroprotective effects through modulation of ferroptosis. Electroacupuncture (EA), an advanced form of acupuncture incorporating electrical stimulation, has shown beneficial effects in ischemic stroke models. EA reduces OGD/R-induced ferroptosis in hippocampal neurons; decreases ACSL4, Tf, and GSK-3β expression; and increases GPX4, Wnt1, and β-catenin levels, implicating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in EA-mediated neuroprotection (164). In MCAO rats, EA applied at specific acupoints such as Zusanli (ST36) and Quchi (LI11) reduces iron overload and oxidative stress, ameliorates mitochondrial injury, and limits ferroptosis (165, 166). Overall, EA regulates ferroptosis by modulating iron-related proteins and redox homeostasis (167). Network pharmacology approaches have revealed multiple active ingredients and signaling pathways in TCM that influence ferroptosis. Ou et al. identified six TCM compounds acting on multiple ferroptosis-related targets, and 7 out of 15 predicted ferroptosis regulators sensitive to TCM modulation (168). This highlights the potential of TCM in targeting ferroptosis for stroke therapy. For example, rehmannioside A, a glycoside isolated from Rehmannia glutinosa, improves cognitive deficits and neurological function in MCAO rats. Its neuroprotective effects are associated with activation of the PI3K/AKT/NRF2 and SCL7A11/GPX4 signaling pathways, indicating a multitarget mechanism of action (169).

Baicalin, a flavone derived from Scutellaria baicalensis, suppresses ferroptosis markers such as iron levels, lipid peroxidation products, and morphological changes in tMCAO mice. It also inhibits RSL3-induced ferroptosis in HT22 cells and reverses I/R injury through the GPX4/ACSL4/ACSL3 axis and PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitochondrial autophagy regulation (170, 171). Similarly, galangin, a flavonoid extracted from Alpinia officinarum, activates the SCL7A1/GPX4 axis and suppresses ferroptosis in gerbil hippocampal neurons after I/R injury (172). Astragaloside IV, a saponin from Astragalus membranaceus, reduces infarct volume and neuronal damage in MCAO rats, potentially through modulation of transmembrane iron transport and ferroptosis pathways (173). However, the specific bioactive components responsible for this effect remain to be characterized. Danhong injection (DHI), a standardized formulation containing Salvia miltiorrhiza and Carthamus tinctorius, is widely used in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease management (174). In MCAO mice, DHI treatment significantly reduces infarct size, mitochondrial necrosis, and iron accumulation, highlighting its ability to suppress ferroptosis and improve stroke outcomes (175). Another TCM formula, Compound Tongluo Decoction (CTLD), reduces infarct volume, alleviates endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and stimulates angiogenesis. Mechanistically, CTLD suppresses ferroptosis via activation of the Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) pathway (176). Our group previously demonstrated that Naotai Formula (NTF) enhances the HSF1/HSPB1 pathway and regulates brain iron homeostasis by suppressing TFR1/dMT1 and activating SCL7A11/GPX4, thereby protecting against ferroptosis in MCAO rats (177, 178). Although current data support the therapeutic potential of TCM in targeting ferroptosis after stroke, the multicomponent and multitarget nature of these interventions necessitates deeper mechanistic exploration to optimize clinical translation.

Ferroptosis is a multifactorial process involving iron metabolism, lipid peroxidation, and antioxidant defense systems. In ischemic stroke, ferroptosis contributes to neuronal death and brain injury through mechanisms involving iron overload, LOX activation, and system Xc− dysfunction. Emerging evidence indicates that targeting ferroptosis—either through small-molecule inhibitors, natural compounds, or TCM formulations—can mitigate brain damage and improve functional outcomes. Despite these promising findings, several challenges remain. First, the molecular triggers of ferroptosis in stroke are not fully understood, and specific biomarkers distinguishing ferroptosis from other forms of programmed cell death are currently lacking. Second, most evidence is derived from preclinical models, and large-scale clinical validation is required. Third, while TCM offers multitarget neuroprotection, its mechanisms and active components remain poorly defined. Future research should focus on identifying key regulatory nodes in ferroptosis, validating novel therapeutics, and dissecting the molecular basis of TCM interventions. By integrating these approaches, we can develop more effective and personalized strategies for managing ischemic stroke and related neurodegenerative conditions.

In summary, although current studies on ferroptosis in cerebral ischemia have identified key biological processes such as lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism imbalance, two central challenges remain unresolved. First, the specificity and clinical utility of ferroptosis biomarkers in human patients have yet to be established. Biomarkers validated in animal models—such as serum GPX4 activity and cerebrospinal fluid 4-HNE levels—show marked individual variability among ischemic stroke patients and are strongly influenced by reperfusion timing and comorbidities such as diabetes. At present, no multicenter cohort studies have validated biomarkers with both diagnostic and prognostic value, nor has the issue of in vivo molecular imaging sensitivity been overcome, particularly for PET probes targeting transferrin receptors. Second, the interaction between ferroptosis and other cell death pathways (such as apoptosis and pyroptosis) remains poorly defined across brain regions. In the ischemic penumbra, neurons predominantly undergo ferroptosis, while astrocytes in the ischemic core are more prone to pyroptosis. However, the signaling intersections between these pathways—for example, whether the NLRP3 inflammasome regulates ferritin heavy chain degradation—remain controversial. Existing reviews tend to list these interactions without critically addressing the gap in understanding of cell-type-specific interaction axes.

In contrast, the innovation of this review lies in three key aspects. 1) By integrating 2025 single-cell sequencing and proteomic datasets, it incorporates vascular endothelial cells for the first time and constructs a three-dimensional map of ferroptosis heterogeneity across neurons, glia, and endothelium. This allows us to propose a novel “stage–cell type–regulator” network model that addresses the limitation of previous reviews which overlooked cellular heterogeneity. 2) To overcome the biomarker bottleneck, we introduce a dual-dimensional diagnostic strategy that combines exosomal proteins and miRNAs, thereby enhancing subtype specificity and improving diagnostic synergy. 3) By linking iron-mediated ferroptosis with necroptosis-like apoptotic features, we propose a “nanocarrier-based dual-target inhibitor” design tailored to specific reperfusion stages. This interdisciplinary approach provides a theoretical framework for precision intervention and offers a more targeted foundation for clinical translation.

4.2 Ferroptosis in intracerebral hemorrhage

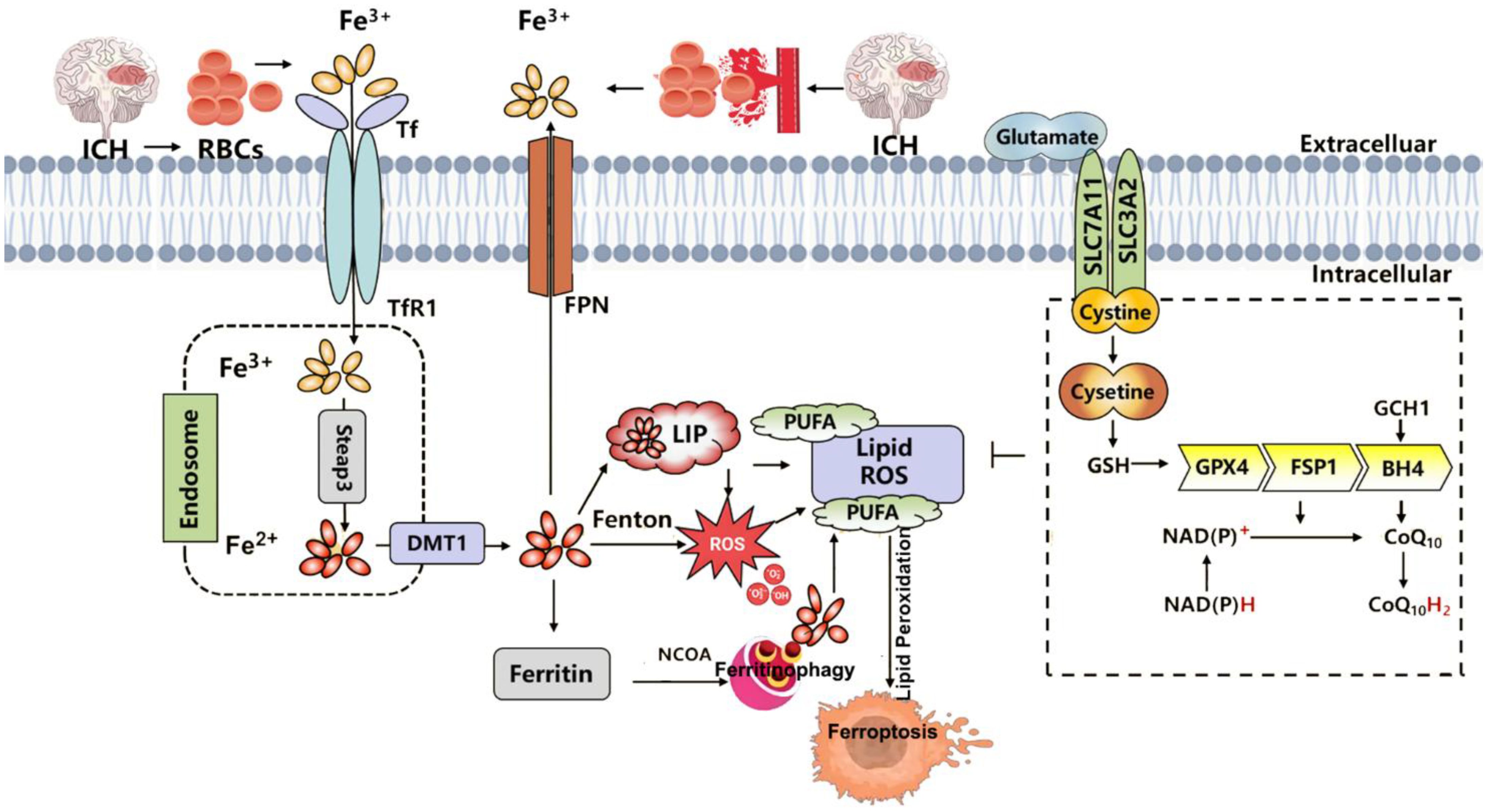

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), a form of intracranial bleeding, is a life-threatening cerebrovascular disorder associated with high mortality and long-term disability worldwide (179, 180). ICH is characterized by sudden onset, rapid progression, and multiple complications, contributing to its substantial clinical burden. Current management primarily relies on surgical intervention to alleviate primary injury; however, no effective therapies exist for secondary brain injury after ICH (SBI-ICH) (180). The pathophysiology of ICH involves both primary mechanical damage from hematoma expansion and secondary biochemical and biomechanical alterations that exacerbate neuronal injury (181). In particular, the degradation of hemoglobin from lysed red blood cells releases toxic substances—such as iron—that contribute to oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and blood–brain barrier disruption (182). A 2017 study was the first to demonstrate activation of ferroptotic pathways following ICH (183), and subsequent studies have confirmed that ferroptosis contributes to neuronal damage after hemorrhage via mechanisms involving neurotoxin release and oxidative stress (184, 185). Following ICH, iron released from hemoglobin triggers excessive ROS production, leading to oxidative stress and secondary brain injury. Preclinical and clinical evidence indicates that toxins derived from hematomas can induce neuronal death through ferroptosis. Specifically, during ICH, erythrocyte lysis leads to hemoglobin release, which is subsequently phagocytized by activated microglia and macrophages. These cells reduce Fe³+ to Fe²+, which is then exported via FPN1 and transported into neurons via the transferrin–transferrin receptor system. Within neurons, excess Fe²+ undergoes Fenton or Haber–Weiss reactions, generating hydroxyl radicals that attack DNA, proteins, and lipid membranes, thereby inducing ROS and lipid peroxidation (183). Therefore, targeting hemoglobin- and iron-induced toxicity may represent a novel therapeutic strategy for ICH.

In organotypic hippocampal slice cultures, the specific ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 prevents neuronal death and reduces hemoglobin-induced iron deposition. Mice treated with Fer-1 after ICH show significant neuroprotection and improved neurological function (183). Moreover, Fer-1 attenuates lipid ROS accumulation and suppresses the upregulation of PTGS2 (which encodes COX-2)—a marker of ferroptosis—supporting the involvement of ferroptosis in post-hemorrhagic neuronal loss (186). Iron-dependent cell death occurs not only at the core of the hematoma but also in remote brain regions, suggesting widespread ferroptosis after ICH (186). In this context, FPN1, the only known mammalian iron exporter, is significantly upregulated in aged ICH patients and mouse models. Genetic deletion of Fpn1 worsens ICH outcomes, whereas viral overexpression of Fpn1 improves recovery, indicating that enhancing iron efflux can mitigate ferroptosis after hemorrhage (117). Oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (OLR1), also known as LOX-1, is upregulated in ICH hematomas. Silencing OLR1 in rat models reduces brain edema, neuronal loss, inflammation, and oxidative stress. This protective effect is mediated through upregulation of GPX4 and FTH1, and downregulation of COX-2, highlighting OLR1 as a key regulator of ferroptosis in ICH (187). Sphingosine kinase 1 (Sphk1) is another critical mediator of ferroptosis in ICH. Its expression is elevated after hemorrhage, and it functions in sphingolipid metabolism to promote ferroptosis (188). Inhibition of Sphk1 in both in vivo and in vitro ICH models attenuates secondary brain injury and neuronal death, reinforcing the role of Sphk1 in ferroptosis-driven ICH pathology. These findings suggest that targeting Sphk1 could offer a promising approach for preventing and treating ICH-related neurodegeneration. Collectively, these data support the hypothesis that ferroptosis is a major contributor to neuronal injury after ICH, potentially through modulation of ferroptosis-associated gene expression (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Summary of the mechanisms of ferroptosis in intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). ICH leads to the extravasation of RBCs into brain tissue. Upon lysis, RBCs release hemoglobin, which is degraded into heme, releasing iron into the local microenvironment. Extracellular Fe³+ binds to Tf and is internalized through TfR1-mediated endocytosis. Within endosomes, Fe³+ is reduced to Fe²+ by Steap3 and transported into the cytoplasm via DMT1. Once in the cytosol, Fe²+ enters the LIP, where it may be stored in ferritin, released through ferritinophagy, or exported by FPN1. Excess Fe²+ catalyzes the Fenton reaction, generating ROS that drive lipid peroxidation of PUFAs, ultimately triggering ferroptosis and neuronal injury. Three major ferroptosis-suppressing pathways counteract this process: the system Xc−–GSH–GPX4 axis, which supports detoxification of lipid peroxides; the FSP1–CoQ10–NAD(P)H pathway, which prevents membrane lipid damage; and the GCH1–BH4 axis, which enhances CoQ10 synthesis and ROS clearance to alleviate oxidative stress. RBC, red blood cell; Tf, transferrin; TfR1, transferrin receptor 1; Steap3, six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 3; DMT1, divalent metal transporter 1; LIP, labile iron pool; FPN1, ferroportin 1; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; GSH, glutathione; FSP1, ferroptosis suppressor protein 1; CoQ10, coenzyme Q10; NAD(P)H, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate): reduced form; GCH1, GTP cyclohydrolase 1; BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin.

4.2.1 Mechanisms of neuronal ferroptosis after intracerebral hemorrhage

Due to the presence of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), iron entry into the brain is tightly regulated. Under normal conditions, Fe³+ circulates bound to transferrin and enters neurons via TfR1-mediated endocytosis (189). Upon ICH, this balance is disrupted: increased extracellular hemoglobin enhances Fe²+ release, overwhelming cellular antioxidant defenses and triggering ferroptosis. Within the brain parenchyma, some Fe²+ is stored in the labile iron pool, while excess iron is exported via FPN1. However, in the setting of ICF, the brain’s limited antioxidant capacity makes it highly susceptible to oxidative damage (190, 191). Post-ICH, activated microglia phagocytize hemoglobin and release chemokines that recruit blood-derived macrophages to the hemorrhagic site. These cells metabolize hemoglobin into free iron, which is then transported into neurons via TfR1. The resulting Fenton reaction generates hydroxyl radicals, promoting extensive lipid peroxidation and damaging macromolecules such as proteins, lipids, and DNA, ultimately leading to neuronal death (192).

To counteract this, the body activates antioxidant systems such as the GPX4–GSH axis. However, during ICH, extracellular glutamate levels rise, inhibiting system Xc− activity, reducing GSH synthesis, and impairing GPX4 function (193). Consequently, redox homeostasis is lost, lipid peroxidation cascades are initiated, and ferroptosis ensues.

4.2.2 Ferroptosis exacerbates secondary brain injury post-ICH

Secondary brain injury after ICH results from complex interplay between brain edema, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and programmed cell death including autophagy, apoptosis, and ferroptosis (193). Ferroptosis intensifies these processes, worsening overall outcome. Hemoglobin and iron released from hematomas activate microglia, leading to elevated inflammatory cytokines and mediators (193). Fe²+ further drives ROS generation via Fenton chemistry, initiating lipid peroxidation and disrupting redox balance. Accumulated hydroxyl radicals and lipid peroxides accelerate the oxidation of biomolecules, amplifying oxidative stress and neuronal damage (157). Hydroxyl radicals generated via Fenton reactions directly increase cerebral edema by impairing ion homeostasis. ROS inhibit Na+-K+ ATPase and Ca²+ pumps, leading to intracellular ionic dysregulation, acidosis, and cytotoxic edema (194). Iron overload not only promotes lipid peroxidation but also induces apoptosis and autophagy, further aggravating secondary brain injury (195). These findings underscore that ferroptosis plays a central role in exacerbating ICH-induced brain damage and that interventions targeting this pathway may provide neuroprotection.

4.2.3 Nrf2 activation suppresses ferroptosis and mitigates secondary brain injury after ICH

Activation of nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2) has emerged as a promising strategy for limiting ferroptosis and improving functional outcomes after ICH. Withaferin A (WFA), a natural compound with neuroprotective properties, significantly reduces MDA levels and enhances antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and GPX in a murine model of striatal ICH (196). WFA activates the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, promoting nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and increasing HO-1 expression. Knockdown of Nrf2 reverses these effects, confirming that WFA exerts neuroprotection via Nrf2-dependent suppression of ferroptosis. Furthermore, combining WFA with Fer-1 reduces hemin-induced neuronal damage in SH-SY5Y cells, reinforcing the therapeutic potential of dual ferroptosis inhibition (196). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) synergizes with Nrf2 to enhance antioxidant gene expression and suppress ferroptosis. Administration of pioglitazone (PDZ), a PPARγ agonist, activates Nrf2 and GPX4 in primary rat hippocampal neurons exposed to hemin. In an autologous blood injection model of ICH, PDZ improves neurological recovery, an effect blocked by the Nrf2 inhibitor ML385, demonstrating that PPARγ/Nrf2/GPX4 signaling underlies its protective mechanism (197). Crocin, a carotenoid derived from saffron, alleviates brain edema and neurological deficits in a mouse model of ICH. Crocin increases SOD and GPX activity; elevates GPX4, FTH1, and SLC7A11 expression; and suppresses lipid peroxidation and iron accumulation, supporting its anti-ferroptotic function (198). Further mechanistic studies indicate that crocin exerts these effects through Nrf2 activation, offering a multitargeted approach to ameliorate secondary brain injury (198). (−)-Epicatechin (EC), a flavanol found in green tea and cocoa, reduces lesion volume and perihematomal neuronal death in experimental ICH. EC activates Nrf2, decreases HO-1 expression, and limits iron deposition, thereby suppressing ferroptosis and related gene expression (199). These findings reinforce the importance of Nrf2 in mitigating ferroptosis and improving stroke outcomes.

Collectively, these studies highlight that pharmacological activation of Nrf2 can reduce ferroptosis and improve neurological deficits in preclinical models of ICH.

4.2.4 Therapeutic potential of ferroptosis inhibitors in ICH

Ferroptosis is closely linked to iron overload, impaired antioxidant defense, and lipid peroxidation in ICH, all of which contribute to inflammation and neuronal damage. Targeting these pathways offers new therapeutic opportunities for reducing secondary brain injury.

1. Iron chelators: Fer-1, a selective ferroptosis inhibitor, reduces ROS and lipid peroxidation, preserves neuronal viability, and improves neurological function in both in vitro and in vivo models (200). Iron chelators such as DFO, DFP, VK28, and clioquinol bind free Fe²+, forming stable complexes that limit iron toxicity. These agents inhibit microglial activation, reduce hemolysis-induced iron overload and oxidative stress, and protect neurons from ferroptosis (201, 202). Clioquinol also enhances Fpn1 expression, facilitating iron efflux and offering an additional route of ferroptosis inhibition (203). Minocycline, a tetracycline antibiotic, shows iron-chelating properties and protects aging female rats from ICH-induced brain injury, although its exact mechanism remains unclear (204). The lipophilic iron chelator pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazone (PIH) reduces total iron, ROS, and lipid peroxidation in perihematomal tissue; increases GPX4 expression; shifts microglia toward the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype; and suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby exerting broad neuroprotection (205).

2. Lipid peroxidation inhibitors: Long non-coding RNA H19 promotes ferroptosis in brain microvascular endothelial cells by regulating the miR-106b-5p/ACSL4 axis. Knockdown of H19 increases SLC7A11 and GPX4 mRNA levels and downregulates TFR1, effectively blocking ferroptosis (206). Paeonol, a natural product isolated from Paeonia suffruticosa, inhibits ferroptosis via the HOTAIR/UPF1/ACSL4 axis in both in vitro and in vivo ICH models, improving neurological outcomes (207). Antioxidants such as N-acetylcysteine (NAC) neutralize toxic lipids generated by arachidonate-dependent lipoxygenase 5 (ALOX5) activity, protecting neurons from ferroptosis and improving post-ICH prognosis (208). Another small molecule, HET0016, inhibits the biosynthesis of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE), a metabolite of arachidonic acid, and demonstrates neuroprotective effects after ICH (209). Liproxstatin-1, a spiroquinoxalinone derivative, suppresses ferroptosis by reducing ROS and activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, restoring memory function, reducing brain atrophy, and alleviating neurological deficits (210).

3. Antioxidant enhancers: The GPX4–GSH axis is one of the most studied antioxidant pathways in ferroptosis. During acute ICH, GSH treatment enhances antioxidant capacity, reduces brain infarct size, improves neurological deficits, and lowers mortality in ICH mice (211). As an upstream precursor of GSH, NAC partially exerts its protective effects through GPX4–GSH restoration, counteracting ALOX5-mediated lipid peroxidation and neuronal damage (208). Selenium, a trace element essential for GPX4 function, modulates GPX4 expression and activity, thereby blocking ferroptosis and improving brain function post-ICH (212). Natural compounds such as baicalin, curcumin, epicatechin, and isoureguanidine alkaloids have shown promise in ICH models by upregulating GPX4 or SLC7A11 and enhancing cellular antioxidant defenses (210–213). For example, curcumin nanoparticles exert anti-ferroptotic effects via the NRF2/HO-1 pathway (213). EC protects against early-stage hemorrhagic injury by enhancing Nrf2-dependent antioxidant responses and reducing HO-1 induction and iron deposition via Nrf2-independent mechanisms (214). Isoureguanidine alkaloids target the miR-122-5p/TP53/SLC7A11 axis, upregulating miR-122-5p and SLC7A11 while suppressing TP53 to prevent ferroptosis (215). Baicalin inhibits SLC11A2, a key iron transporter, thereby reducing iron deposition and conferring protection in ICH models (216).

In summary, ferroptosis is a key pathological mechanism in ICH, contributing to neuronal death and secondary brain injury. Recent studies have identified multiple molecular targets and therapeutic strategies that inhibit ferroptosis, including iron chelators, lipid peroxidation inhibitors, and natural antioxidants capable of restoring GPX4 and GSH levels. However, the translational gap between basic research and clinical application remains unresolved. In the field of biomarkers, the challenge extends beyond a simple lack of specificity to a more fundamental flaw in translational logic. The low detection accuracy of in vivo imaging, caused by interference from free iron, parallels the translational paradox seen in clinical trials of iron chelators such as deferoxamine—effective in animals but ineffective in humans—revealing that a coordinated validation system linking molecular targets, imaging evaluation, and clinical efficacy is still lacking.

Although traditional Chinese medicine research has identified several signaling pathways that regulate ferroptosis, over 90% of these studies are confined to rodent models, without validation of targets or dosage in human patients. This limitation further fragments biomarker translation. In the study of cell death interactions, the problem of “mechanistic isolation” is prominent. The lack of understanding of the signaling cascade between pericyte ferroptosis and endothelial necrosis has made it difficult to select effective vascular-protective targets. If the process is mediated by inflammatory factors, interventions should focus on the TLR4/NLRP3 axis; if driven by iron diffusion, the emphasis should shift to intercellular iron transport channels such as ferroportin. These two mechanisms require entirely different therapeutic approaches. Moreover, the unclear regulatory relationship between the H3K14la/PMCA2 axis and microglial pyroptosis further undermines the theoretical foundation for targeting the integrated “neurovascular–immune” cell death network.

Future research should focus on an integrated strategy that connects mechanism, biomarker, and intervention. The innovative framework proposed in this review provides a starting point for such an approach. At the biomarker level, it is necessary to establish a combined plasma exosome panel adjusted for ethnic variability to minimize individual differences, and to define stratified thresholds according to ICH subtype (hypertensive or traumatic). At the mechanistic level, spatial single-cell transcriptomic studies are urgently needed to map cell death interactions across the hematoma core, penumbra, and surrounding normal tissue. At the interventional level, combination therapy strategies—borrowed from cancer research—should be employed, together with targeted drug delivery systems such as modified nanocarriers to expand the therapeutic window. Only through such coordinated advances can the current gap between mechanistic understanding and clinical efficacy be bridged, enabling ferroptosis modulation to become a truly transformative direction in ICH treatment.

4.3 Ferroptosis in traumatic central nervous system injury