- Department of Ophthalmology, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, Hubei, China

Glaucoma is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the progressive loss of retinal ganglion cell and optic nerve damage. Recent studies have highlighted the pivotal role of microglia in the onset and progression of glaucoma. This review aims to elucidate the key mechanisms of microglial activation in glaucoma and assess its potential as a therapeutic target for novel treatment strategies. Microglia activation in glaucoma is multifactorial, driven by biomechanical, metabolic, and inflammatory signals. Activated microglia contribute to both neuroinflammatory injury and neuroprotective responses. Their interaction with other kinds of cell establishes a dynamic inflammatory signaling network that exacerbates retinal ganglion cell loss. Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that key targets in microglial activation, such as APOE, LGALS3, CX3CR1, etc. play critical roles in disease progression, revealing promising targets for therapeutic intervention. Microglia act as central regulators of the retinal immune microenvironment in glaucoma. Their dual role in neurotoxicity and neuroprotection is shaped by complex interactions with other kinds of cell. Targeting microglial activation state and restoring metabolic homeostasis represent promising strategies for the development of pressure-independent treatments for glaucoma.

Introduction

Glaucoma is a group of chronic, progressive neurodegenerative eye diseases characterized by optic nerve damage and visual field defects, and it remains the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide (1, 2). A characteristics of glaucoma is the progressive loss of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) and optic nerve degeneration, typically accompanied by elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) (3, 4). It is estimated that approximately 95 million people are affected by glaucoma globally, with at least 10 million experiencing blindness in one eye, and many more suffering from visual impairment that compromises daily functioning (3, 5). Although current treatments primarily focus on lowering IOP, accumulating evidence shows that progressive optic nerve damage still occurs in patients with well-controlled IOP, suggesting that the pathogenesis of glaucoma involves more complex mechanisms beyond pressure elevation alone (6, 7). In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to neuroimmune inflammation in the development of glaucoma, particularly to the activation of microglia, the resident immune cells of the central nervous system, and their close relationship with RGC injury (8, 9).

Microglia are resident innate immune cells in the retina that play essential roles in maintaining tissue homeostasis and responding to injury (10, 11). During the pathogenesis of glaucoma, microglia can be activated by various stimuli such as elevated IOP, axonal injury, and metabolic dysregulation, leading to morphological changes, enhanced secretion of inflammatory mediators, and altered phagocytic activity (12, 13). Activated microglia may induce neuronal apoptosis and axonal degeneration by releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and complement proteins (14–16). In addition, it engage in complex intercellular interactions with other cells, including astrocyte and Müller cell, forming a dynamic network that collectively regulates inflammation, metabolic homeostasis, and the balance between neuroprotection and neurodegeneration.

Recent advances in single-cell transcriptomics, spatial transcriptomics, and metabolomics have enabled researchers to investigate microglia phenotypic and functional heterogeneity in glaucoma with unprecedented resolution (17–19). These technologies have facilitated the identification of microglia subpopulations, signaling pathways, and potential therapeutic targets (20, 21). This review focuses on the mechanisms underlying microglia activation in glaucoma, its interactions with other cells, and its roles in mechanical stress sensing, mitochondrial function, and energy metabolism remodeling. Furthermore, we discuss emerging intervention strategies aimed at modulating microglia function, with the goal of providing theoretical insight for future mechanistic study and therapeutic target discovery in glaucoma.

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a common blinding disease characterized by progressive optic nerve damage and visual field loss (4). Based on the anatomical configuration of the anterior chamber angle and the site of aqueous humor outflow obstruction, glaucoma is typically classified into open-angle and angle-closure types (22, 23). Among them, primary open-angle glaucoma is the most prevalent form. Its main pathophysiological mechanism involves structural or functional abnormalities in the aqueous humor outflow pathways, resulting in increased outflow resistance and elevated IOP. In contrast, angle-closure glaucoma is caused by the closure of the anterior chamber angle, which impedes aqueous humor drainage and leads to a rapid rise in IOP. Sustained elevation of IOP can compress the optic nerve head (ONH), damage the axons of RGC, and subsequently trigger progressive RGC degeneration (24).

Although elevated IOP is a major factor causing damage for glaucoma, a subset of patients develops glaucomatous optic neuropathy even when IOP remains within the normal range, a condition referred to as normal tension glaucoma (25, 26). Conversely, some individuals with high IOP do not exhibit detectable optic nerve damage (27, 28). Furthermore, some patients continue to experience disease progression despite adequate IOP control (29, 30). These findings suggest that the pathogenesis of glaucoma involves more than IOP elevation alone and is influenced by a complex interplay of intraocular and systemic factors. Therefore, the development of novel therapeutic strategies that directly protect RGC and preserve visual function through IOP-independent mechanisms is of great clinical importance for improving glaucoma management.

Microglia in glaucoma

Accumulating evidence suggests that immune and inflammatory responses also play a critical role in its onset and progression (31). In particular, activation of microglia, the resident immune cells of the central nervous system, has emerged as a key pathological feature in glaucoma neurodegeneration.

In the chronic ocular hypertension mouse model, IOP elevation leads to increased microglia numbers and promotes their migration from the inner plexiform layer toward the ganglion cell layer and nerve fiber layer (32, 33). Microglia proliferation begins as early as day 1 after model induction and peaks at week 2 (34, 35). In the unilateral laser-induced ocular hypertension model, microglia activation and migration toward the injury site can be detected within 24 hours of IOP elevation, even in the absence of a significant change in total microglia number (36). Morphologically, activated microglia are characterized by an enlarged soma, retracted processes, and an amoeboid appearance, along with upregulated expression of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II), a marker of phagocytic activation (37). In the ONH, such changes are evident as early as day 3 following IOP elevation. By day 7, microglia are widely distributed across the ganglion cell layer and retinal nerve fiber layer, and this activated state persists for at least 2 weeks (35). This finding was further validated in human samples, which showed a significant increase in IBA1 intensity in the retina, although the number of IBA1+ microglias did not significantly increase (38). In another human study, numerous amoeboid IBA1+ microglias or infiltrating monocytes were observed predominantly along the inner edge of the ILM, where rod-shaped or bipolar IBA1+ cells also accumulated (39). This microglial activation was accompanied by a marked upregulation of inflammatory markers and pro-inflammatory cytokines (40). Meanwhile, as a result of RGC degeneration in glaucoma, changes in microglia morphology and gene expression have also been reported in the brain, especially in the dorsolateral geniculate nucleus. These findings suggest that the alteration of these microglia may be a secondary and major adaptive immune response to vision-related neurodegeneration (41). However, the mechanisms underlying glial cell activation in the retina of glaucoma patients and their association with neuronal death remain to be further elucidated. Although single-cell transcriptomic studies have advanced our understanding of the normal human retina, obtaining the retina of glaucoma patients still pose major challenges (17, 42).

As the innate immune cells of the CNS, microglia possess a range of functions, including environmental sensing, phagocytosis of cell debris, and immune regulation (43, 44). Under physiological conditions, microglia exhibit a ramified morphology and continuously monitor their microenvironment via dynamic extension and retraction of their processes. Upon exposure to external stimuli such as elevated IOP or neuronal injury, microglia rapidly transition into an activated state, adopting an amoeboid morphology and exhibiting functional polarization into either pro-inflammatory M1 or anti-inflammatory and M2 phenotypes (45, 46). M1 microglia secrete pro-inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), thereby amplifying the inflammatory cascade. In contrast, M2 microglia express molecules such as CD206 and IL-10, which contribute to neuroprotection and tissue repair (47). M2 microglia is composed of three distinct subpopulations. It mainly includes the M2a subtype involved in anti-inflammation and tissue repair, the M2b subtype involved in regulating immune responses, and the M2c subtype involved in phagocytosis and immunosuppression (8, 48). In addition, there is a type of microglia that is activated by CSF-1 or IL-34 and is different from the M1 or M2a polarization state, which is defined as M3 type (49). This type of cell may be closely related to the division and prolife. However, there are currently no studies on type M3 glaucoma. Other microglial phenotypes have also been described, including rod-like microglia with elongated somata, limited cytoplasm, and reduced branching, which have been observed in mouse models of glaucoma and are implicated in retinal neurodegeneration (50). Although the M1/M2 classification represents a simplified framework, it remains useful for enhancing our understanding of microglial functional states.

In recent years, advancements in single-cell sequencing have deepened our understanding of the pathological states of microglia in glaucoma. By performing large-scale RNA sequencing on microglia isolated from two distinct models of glaucomatous neurodegeneration, researchers identified a disease-associated microglia (DAM) state, whose transcriptional profile closely resembles that observed in multiple models of neurodegeneration in the brain (51, 52). This state is characterized by the upregulation of secretory molecules such as apolipoprotein E (APOE) and lectin, galactoside binding soluble 3 (LGALS3), pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α and chemokines including C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) (53). In the future, with the application of higher-resolution technologies, our understanding of the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of microglia in glaucoma, as well as their disease-specific features, is expected to deepen (54). Such advances will facilitate the identification of key regulatory factors influencing microglial states and may contribute to the development of targeted therapeutic strategies for glaucoma and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Neuroprotective microglia in glaucoma

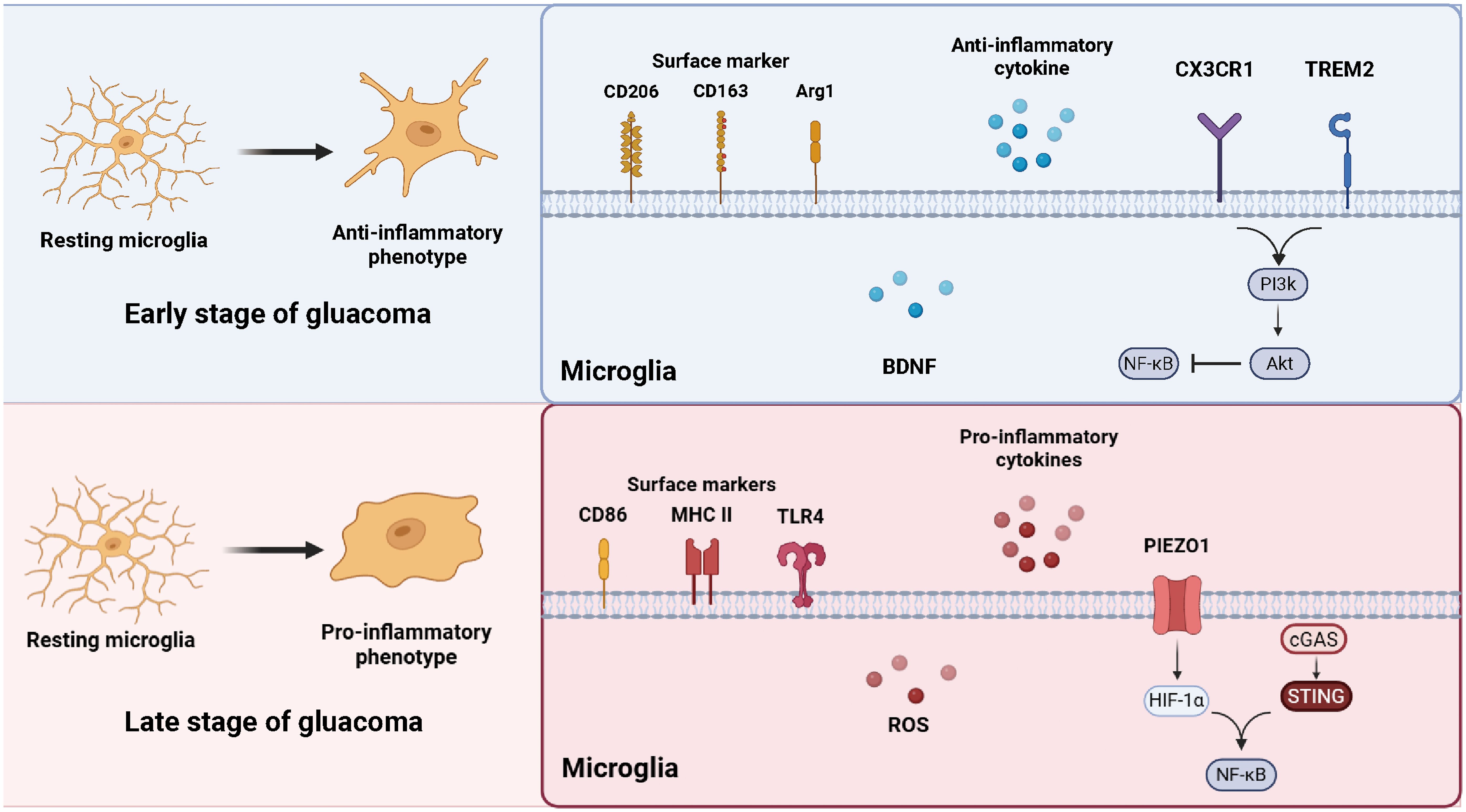

Microglia activation is considered one of the earliest events in glaucomatous neurodegeneration, often preceding detectable RGC loss (55, 56). In experimental glaucoma models, CD206+ M2 microglia transiently increase during the early stage, whereas CD86+ M1 microglia become predominant at later stage (33, 57). This seems to suggest that microglial activation in the early stage of glaucoma may have a neuroprotective effect, while prolonged or chronic activation can exacerbate neurodegeneration. At this point, the early clearance of microglia in DBA/2J mice with age-related intraocular pressure elevation and glaucomatous neurodegeneration, which shows exacerbated glaucomatous neurodegeneration, also seems to demonstrate the early protective effect against glaucoma (58). Studies have shown that early administration of exogenous IL-4 can prolong the duration of M2 microglial polarization after RIR and effectively improve the loss of RGC in the late stage (57). This suggests that, in addition to inhibiting the pro-inflammatory M1 microglia at later stage, prolonging the presence or activity of M2 microglia may also exert neuroprotective effects.

Following RGC apoptosis, the externalization of phosphatidylserine on the cell membrane acts as a classical “eat-me” signal that activates microglia, thereby inducing their activation and phagocytic response (59). Study has shown that intravitreal injection of apoptotic neurons can trigger microglia activation in vivo, suggesting that apoptotic neurons may serve as key stimuli for microglia phenotypic shifts (60). In the early stage of glaucoma, activated M2 microglia clear apoptotic or degenerated RGCs through phagocytosis, thereby maintaining a non-toxic retinal environment and preventing the further spread of inflammation. In addition, M2 microglia can secrete brain-derived neurotrophic factor and other anti-inflammatory cytokines to exert anti-apoptotic effects on RGCs (48).

Neurotoxic microglia in glaucoma

In later stage of experimental glaucoma, the number of activated M1 microglia gradually increases (33). The activation of microglia in this context primarily exhibits pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic effects. Research has shown that in an experimental mouse model of glaucoma with transient elevation of IOP, pharmacological suppression of microglial activation by minocycline significantly increased RGC survival (61). The protective effect observed with the inhibition of microglial activity, in contrast to the aggravated damage caused by microglial depletion, suggests that the outcomes of modulating microglial activation may vary depending on the timing and the specific intervention strategies applied. At this stage, microglia phagocytose neuronal debris or fragmented DNA, activating intracellular pathways such as NF-κB and cGAS–STING and promoting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and exosomes (62). These microglia-derived cytokines and exosomes further amplify inflammation by enhancing microglial migration, phagocytosis, and proliferation, as well as inducing neuronal ROS production and cell death, thereby exacerbating retinal neurodegeneration under elevated IOP conditions (63). It is worth noting that such damage is not limited to RGCs. In animal models of acute or chronic glaucoma, electroretinogram assessments have demonstrated functional impairments in multiple types of retinal cells, including amacrine and bipolar cells (64, 65). Immunohistochemical analyses further corroborate these finding (66). Moreover, although photoreceptor loss is typically not associated with primary open-angle glaucoma, it has been reported in cases of secondary angle-closure glaucoma and in experimental animal models (67–70). Highly activated microglia may therefore contribute to the degeneration and loss of retinal cells beyond RGCs.

Beyond biochemical stimuli, physical factors such as mechanical stretch may also contribute to microglia activation (71). The mechanosensitive ion channel PIEZO1 is highly expressed in microglia cell lines and brain endothelial cells and has been shown to regulate microglia motility and immune responsiveness (72). In monocyte, PIEZO1 mediates calcium influx in response to mechanical stimulation, thereby activating hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α)-dependent inflammatory pathways (73). In both in vitro and in vivo settings, Piezo1 knockout in microglia suppresses LPS-induced expression of inflammatory cytokines, while treatment with the PIEZO1 agonist YODA1 enhances their production (74). Another mechanosensitive and osmotically sensitive ion channel, transient receptor potential vanilloid 4, may also sense extracellular matrix stiffness and regulate microglia inflammatory responses (75, 76). These findings indicate that microglia can sense mechanical stress resulting from elevated IOP and respond with inflammatory activation. ONH is the primary site of early glaucomatous damage. Because RGC axons converge at this region, microglia in the ONH exhibit heightened sensitivity to mechanical deformation and extracellular matrix remodeling compared with Müller cells. Moreover, due to the close crosstalk between microglia and astrocytes, mechanotransduction within ONH astrocytes can trigger their activation and the release of inflammatory mediators, which in turn modulate microglial behavior through intercellular signaling (77). It is important to note that for normal pressure glaucoma, mechanical stress may not play a major role in the triggering of inflammatory damage.RGC loss, progressive axonal degeneration and reactive gliosis were observed in OPTN-E50K knock-in mice, a commonly used animal model of normal stress glaucoma. One possible mechanism is that retinal microglia regulate high levels of apolipoprotein A1 to lead to apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells and reduction in retinal peripapillary vascular density, thereby further augments RGCs damage (78).

The integrity of mitochondrial function plays an important role in regulating microglia polarization under inflammatory conditions. Mitochondrial dysfunction is recognized as a key driver of pro-inflammatory microglia phenotypes in various neurodegenerative diseases (79, 80). In DBA/2J mice, microglia exhibit transcriptional signs of metabolic dysregulation prior to axonal degeneration at the ONH, including upregulation of mitochondrial genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation and abnormal expression of genes related to glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and lipid metabolism (81). Similarly, RNA sequencing of microglia in glaucoma animal models reveals increased expression of Slc16a1, a bidirectional transporter of lactate, pyruvate, and ketone bodies, suggesting heightened metabolic demands and functional plasticity of microglia in early stage of glaucoma (81). This metabolic shift may be associated with the upregulation of HIF-1α, the key glycolytic transcription factor under oxidative stress and inflammatory conditions, as further supported by studies using microbead-induced ocular hypertension mouse models (82). Moreover, mitochondrial fragmentation is enhanced in activated microglia and released extracellularly (83). These extracellular mitochondria may trigger innate immune responses in neighboring astrocyte or serve as signaling molecules in glia-neuron interactions (84). Mitochondrial dysfunction may also contribute to retinal hypoxia and reduced glucose availability, resulting in excessive ROS generation, oxidative stress, and exacerbated RGC damage (85, 86). (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Microglial phenotypic transformation during glaucoma. In the early stage of glaucoma, resting microglia shift toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype, characterized by the expression of surface markers CD206, CD163, and ARG1, and the release of neuroprotective factors such as BDNF, CX3CR1 and TREM2 signaling maintain microglial homeostasis through the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB pathways. In the late stage, microglia adopt a pro-inflammatory phenotype expressing CD86, MHC II, and TLR4, accompanied by increased production of ROS and pro-inflammatory cytokines. External stimulus further triggers the cGAS–STING and HIF-1α–NF-κB pathways, amplifying neuroinflammation and contributing to RGC degeneration. (The figure is created by https://www.biorender.com/).

Microglia crosstalk with retinal cells in glaucoma

Astrocyte

Astrocyte play a vital supportive role for RGC within the retina. They are primarily localized in the nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell layer, where they envelop blood vessels extensively in the ONH region (11). Similar to their functions in the brain, retinal astrocyte contribute to the maintenance of the blood-retinal barrier (BRB) and immune privilege through close interactions with the vasculature (12, 87). They regulate vascular tone and facilitate the transport of metabolic substrates from the bloodstream, thereby supporting the energy demands of RGC axons.

In glaucoma, pro-inflammatory activation of microglia may disrupt astrocyte function through the release of cytokines and other mediators. M1-polarized microglia can secrete inflammatory factors such as complement component C1q, IL-1β, and TNF-α, which collectively drive the transformation of astrocyte into a neurotoxic A1 phenotype, further amplifying neuroinflammation (88). Studies in mouse models of glaucoma have shown that the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist NLY01 can inhibit the production of these cytokines by microglia and prevent the induction of A1 astrocyte, ultimately protect the RGC. Under homeostatic conditions, both astrocyte and microglia express matrix metalloproteinase-2 primarily at their perivascular endfeet (89). However, upon activation, the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 is markedly upregulated, contributing to increased BRB permeability, pathological neovascularization, and glial scar formation, all of which exacerbate retinal injury (90, 91).

Müller cell

Müller cells are the principal radial glial cells in the retina and play a pivotal role in maintaining retinal homeostasis. Müller cells provide necessary metabolic support and ionic homeostasis for RGCs. In the early stage of glaucoma, muller cells can sense retinal hypoxia earlier, but the activation at this time may still be mainly protective, providing necessary metabolic support for the hypoxic nerve cells (82). In addition, upon activation, Müller cells can release ATP through connexin 43 hemichannels (92, 93). Studies have shown that ATP released by activated Müller cells can trigger microglia activation by stimulating P2X7R on the microglia surface (33). On the day4 after chronic ocular hypertension (COH), activated microglia in branched and amoeba-like shapes were observed. In addition, microglia transfer from the inner/outer plexiform layer of the retina to the GCL of the COH retina (94, 95). Intravitreal injection of the P2X7R agonist BzATP or in vitro stimulation with DHPG can increase the migration and proliferation of microglia. In particular, the P2X7R, which is closely associated with inflammatory responses, can be activated by ATP to initiate NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome assembly and induce the release of multiple pro-inflammatory mediators, such as IL-1β (96–98). It has been demonstrated that pharmacological blocking or knockout of P2X7R delays activation of microglia and RGC death following COH in mice (35). Further evidence supports the involvement of microglial activity in RGC degeneration, as P2X7R knockout has been shown to delay RGC death following optic nerve crush in mice (99).

In normal mice, intravitreal injection of the group I metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist DHPG has been shown to induce Müller cell activation. Following DHPG administration, the expression of translocator protein (TSPO), the markers of microglia activation, gradually increases and becomes significantly elevated after one week. In contrast, inhibition of Müller cell activation using the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 antagonist MPEP leads to a reduction in TSPO level, along with decreased GFAP expression, suggesting that Müller cell activation may serve as an important upstream event in microglia activation (33).

In addition to inflammatory crosstalk, Müller cells and microglia engage in neuroprotective interactions mediated by neurotrophic factors. Microglia can secrete nerve growth factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which not only exert direct protective effects on RGC but also promote the expression of basic fibroblast growth factor and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in Müller cells, thereby exerting synergistic neuroprotective effects (100–102).

Monocyte

Both active extravasation and passive leakage of monocyte have been observed in experimental models of glaucoma, closely associated with the breakdown of the BRB (103, 104). Notably, monocyte infiltration has been detected in the ONH region of glaucoma eyes, suggesting that monocyte recruitment may be an early pathological feature of the disease, as documented in several animal models (39, 105–107).

The CCL2 signaling axis plays a critical role in regulating monocyte migration. CCL2 binding to its receptor CCR2 directs monocyte to sites of injury, promoting their infiltration. Elevated levels of CCL2 have been shown to reduce neuronal survival in animal models of glaucoma (108). Conversely, genetic deletion of Ccl2 significantly preserves RGC and reduces the density of retinal myeloid cells, without altering the expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. These findings suggest that monocyte recruitment itself may exert pathogenic effects independent of subsequent inflammatory signaling (109).

Therapeutic strategies targeting microglia in glaucoma

Currently, regardless of the subtype of glaucoma, clinical treatment primarily focuses on lowering IOP by either reducing aqueous humor production or enhancing its outflow. However, extensive clinical and experimental evidence indicates that IOP-lowering therapy alone is insufficient to halt the progressive visual deterioration of the majority of patients (110). Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop IOP-independent therapeutic strategies for glaucoma.

While mice express a single APOE isoform, humans possess three major alleles (APOE2, APOE3, and APOE4). APOE4 is a well-established genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, but paradoxically, it has been associated with reduced glaucoma risk in several human studies (111–113). Even under elevated IOP conditions, ApoE4-expressing microglia exhibit robust suppression of pro-inflammatory genes such as Lgals3, Tnf-α, and Ccl2, while maintaining the expression of homeostatic genes like C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (Cx3cr1) and colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (Csf1r) (114, 115). Moreover, ApoE is markedly upregulated in phagocytic retinal microglia, and this finding has been validated at the protein level. In wild-type microglia, phagocytic activation induces the upregulation of DAM genes such as Lgals3, Gpnmb, Spp1. In contrast, this phenotype is significantly attenuated in APOE-deficient retinal microglia (60).

LGALS3 is considered a key regulator of microglia activation. It has been shown to directly activate microglia, act as a chemoattractant for monocyte, and serve as a marker of phagocytic states (116, 117). In both the microbead-induced model and DBA/2J mice, Lgals3 expression is upregulated at both the mRNA and protein levels, and is modulated by APOE signaling. In the microbead model of glaucoma, Lgals3 is one of the genes most strongly affected by APOE deficiency (60). Genetic deletion of Lgals3 or pharmacological inhibition using agents such as TD139 significantly protects RGC, even under elevated IOP (60, 118). Although the precise mechanisms underlying the neurotoxicity of LGALS3 remain unclear, it is known to function as an endogenous ligand for toll-like receptor 4, potentially acting upstream of inflammasome activation (119, 120). Furthermore, LGALS3 can bind the receptor, and may serve as a critical molecular bridge for its activation in microglia (121, 122). Collectively, these findings support the involvement of LGALS3 in mediating pathological inflammation and phagocytic responses of microglia in glaucoma neurodegeneration.

Under physiological conditions, the homeostasis of microglia is tightly regulated by a repertoire of signaling molecules that suppress aberrant activation through interactions with microglia surface receptors. Among these, the CX3CL1-CX3CR1 axis is a critical inhibitory pathway. CX3CR1, the receptor for CX3CL1, is predominantly expressed in microglia within ocular tissues (123). Studies have shown that CX3CR1 can suppress the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and CCL2 under homeostatic conditions (124, 125). In animal models of glaucoma, CX3CR1 deficiency lowers the activation threshold of microglia, enhances their pro-inflammatory phenotype, and exacerbates RGC loss in response to transient IOP elevation (61, 126, 127). In the rd10 mouse model of retinal degeneration, CX3CR1 knockout results in increased microglia phagocytic activity and elevated secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators, accelerating photoreceptor degeneration. Conversely, intravitreal administration of recombinant CX3CL1 effectively suppresses abnormal microglia activation, suggesting a potential neuroprotective role of this signaling axis (128, 129). Moreover, the loss of CX3CL1- CX3CR1 signaling can also exacerbates disease pathology in other ocular disease models. For example, in laser-induced choroidal neovascularization model, CX3CR1-deficient mice exhibit more severe phenotypes, including thinning of the outer retina and drusen-like subretinal deposits (125). Similarly, in experimental autoimmune uveitis, CX3CR1 deficiency correlates with increased disease severity (130).

The precise physiological roles of microglia in the retina remain under investigation. Genetic tools targeting CX3CR1 have been used to selectively deplete microglia, revealing that retinal neurons can maintain gross structural integrity and viability in the absence of microglia (131). However, functional assessments showed a gradual reduction in electroretinography amplitudes in response to light stimuli, despite retained visual function. Transmission electron microscopy further revealed dystrophic and morphologically abnormal presynaptic terminals, suggesting that microglia may play a crucial role in maintaining mature retinal synaptic integrity.

Additional studies using the CSF1R inhibitor PLX5622 to deplete microglia showed that PLX5622 treatment alone does not impair RGC function. However, in ischemia reperfusion injury models, microglia depletion significantly attenuated IR-induced neuroinflammation and inner BRB disruption (132). In diabetic retinopathy models, approximately two months of PLX5622 treatment also mitigated neurodegenerative and vascular changes (133). In contrast, in models of acute optic nerve crush injury, microglia depletion via PLX5622 had no significant impact on RGC degeneration (134). It suggests that microglia may play a more prominent role in responding to extrinsic stressors (e.g., ischemia, elevated IOP, or metabolic dysregulation) than in direct RGC injury.

At the molecular level, genome-wide association studies have identified common variants near the ABCA1 gene as being associated with increased glaucoma susceptibility (135, 136). ABCA1, a cholesterol efflux pump, plays a vital role in maintaining lipid homeostasis and modulating inflammatory responses. Deficiency of ABCA1 has been linked to retinal neurodegeneration (137). In a mouse model of acute IOP elevation-induced ischemia reperfusion injury, elevated IOP promotes ubiquitin-mediated degradation of ABCA1. This in turn impairs membrane translocation of annexin A1, facilitates microglia activation, and contributes to RGC apoptosis (138).

Conclusion

Glaucoma is a multifactorial neurodegenerative disorder, the progression of which involves a complex interplay of cellular and molecular mechanisms. Among these, microglia activation play a central role in shaping the retinal inflammatory microenvironment and mediating RGC damage. Accumulating evidence indicates that microglia contribute not only through the release of pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic mediators, but also via intricate crosstalk with other kinds of cells, collectively forming a dynamic network of metabolism and homeostasis regulation.

This network is modulated by multiple pathological cues, including cell death, mechanical stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. These findings underscore the importance of shifting from a reductionist that approach focused on individual cell types or signaling pathways to a systems-level perspective that emphasizes the coordinated interactions among different cell populations.

Advances in single cell transcriptomics, spatial omics, and metabolomics offer powerful tools to unravel the spatiotemporal dynamics of cell networks in glaucoma. Integrating these technologies holds great promise for deciphering the molecular logic underlying glial reprogramming and for identifying novel therapeutic strategies aimed at microglia functional modulation, inflammation resolution, and metabolic intervention in glaucoma.

Author contributions

LC: Investigation, Writing – original draft. SY: Writing – original draft, Methodology. DW: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. PH: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Flaxman SR, Bourne RRA, Resnikoff S, Ackland P, Braithwaite T, Cicinelli MV, et al. Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990-2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. (2017) 5:e1221–e34. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30393-5

2. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the Right to Sight: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Health. (2021) 9:e144–e60. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30489-7

3. Jayaram H, Kolko M, Friedman DS, and Gazzard G. Glaucoma: now and beyond. Lancet. (2023) 402:1788–801. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01289-8

4. Weinreb RN, Aung T, and Medeiros FA. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. Jama. (2014) 311:1901–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3192

5. Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, and Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. (2014) 121:2081–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013

6. Almasieh M, Wilson AM, Morquette B, Cueva Vargas JL, and Di Polo A. The molecular basis of retinal ganglion cell death in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. (2012) 31:152–81. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.11.002

7. Fry LE, Fahy E, Chrysostomou V, Hui F, Tang J, van Wijngaarden P, et al. The coma in glaucoma: Retinal ganglion cell dysfunction and recovery. Prog Retin Eye Res. (2018) 65:77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.04.001

8. Li H, Li B, and Zheng Y. Role of microglia/macrophage polarisation in intraocular diseases (Review). Int J Mol Med. (2024) 53:45. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2024.5446

9. Fernández-Albarral JA, Ramírez AI, de Hoz R, Matamoros JA, Salobrar-García E, Elvira-Hurtado L, et al. Glaucoma: from pathogenic mechanisms to retinal glial cell response to damage. Front Cell Neurosci. (2024) 18:1354569. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2024.1354569

10. Silverman SM and Wong WT. Microglia in the retina: roles in development, maturity, and disease. Annu Rev Vis Sci. (2018) 4:45–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev-vision-091517-034425

11. Reichenbach A and Bringmann A. Glia of the human retina. Glia. (2020) 68:768–96. doi: 10.1002/glia.23727

12. Alarcon-Martinez L, Shiga Y, Villafranca-Baughman D, Cueva Vargas JL, Vidal Paredes IA, Quintero H, et al. Neurovascular dysfunction in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. (2023) 97:101217. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2023.101217

13. Miao Y, Zhao GL, Cheng S, Wang Z, and Yang XL. Activation of retinal glial cells contributes to the degeneration of ganglion cells in experimental glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. (2023) 93:101169. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2023.101169

14. Li Q and Barres BA. Microglia and macrophages in brain homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. (2018) 18:225–42. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.125

15. Au NPB and Ma CHE. Neuroinflammation, microglia and implications for retinal ganglion cell survival and axon regeneration in traumatic optic neuropathy. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:860070. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.860070

16. Vecino E, Rodriguez FD, Ruzafa N, Pereiro X, and Sharma SC. Glia-neuron interactions in the mammalian retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. (2016) 51:1–40. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.06.003

17. Monavarfeshani A, Yan W, Pappas C, Odenigbo KA, He Z, Segrè AV, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of the ocular posterior segment completes a cell atlas of the human eye. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2023) 120:e2306153120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2306153120

18. Mok JH, Park DY, and Han JC. Differential protein expression and metabolite profiling in glaucoma: Insights from a multi-omics analysis. Biofactors. (2024) 50:1220–35. doi: 10.1002/biof.2079

19. Leruez S, Marill A, Bresson T, de Saint Martin G, Buisset A, Muller J, et al. A metabolomics profiling of glaucoma points to mitochondrial dysfunction, senescence, and polyamines deficiency. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2018) 59:4355–61. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-24938

20. Hamel AR, Yan W, Rouhana JM, Monovarfeshani A, Jiang X, Mehta PA, et al. Integrating genetic regulation and single-cell expression with GWAS prioritizes causal genes and cell types for glaucoma. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:396. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-44380-y

21. van Zyl T, Yan W, McAdams A, Peng YR, Shekhar K, Regev A, et al. Cell atlas of aqueous humor outflow pathways in eyes of humans and four model species provides insight into glaucoma pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2020) 117:10339–49. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2001250117

22. Schuster AK, Erb C, Hoffmann EM, Dietlein T, and Pfeiffer N. The diagnosis and treatment of glaucoma. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2020) 117:225–34. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0225

24. Zhang Y, Huang S, Xie B, and Zhong Y. Aging, cellular senescence, and glaucoma. Aging Dis. (2024) 15:546–64. doi: 10.14336/AD.2023.0630-1

25. Leung DYL and Tham CC. Normal-tension glaucoma: Current concepts and approaches-A review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. (2022) 50:247–59. doi: 10.1111/ceo.14043

26. Fox AR and Fingert JH. Familial normal tension glaucoma genetics. Prog Retin Eye Res. (2023) 96:101191. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2023.101191

27. Hark LA, Myers JS, Pasquale LR, Razeghinejad MR, Maity A, Zhan T, et al. Philadelphia telemedicine glaucoma detection and follow-up study: intraocular pressure measurements found in a population at high risk for glaucoma. J Glaucoma. (2019) 28:294–301. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001207

29. King AJ, Hudson J, Azuara-Blanco A, Burr J, Kernohan A, Homer T, et al. Evaluating primary treatment for people with advanced glaucoma: five-year results of the treatment of advanced glaucoma study. Ophthalmology. (2024) 131:759–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2024.01.007

30. Bengtsson B, Heijl A, Aspberg J, Jóhannesson G, Andersson-Geimer S, and Lindén C. The glaucoma intensive treatment study (GITS): A randomized controlled trial comparing intensive and standard treatment on 5 years visual field development. Am J Ophthalmol. (2024) 266:274–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2024.06.017

31. Baudouin C, Kolko M, Melik-Parsadaniantz S, and Messmer EM. Inflammation in Glaucoma: From the back to the front of the eye, and beyond. Prog Retin Eye Res. (2021) 83:100916. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100916

32. Nadal-Nicolás FM, Jiménez-López M, Salinas-Navarro M, Sobrado-Calvo P, Vidal-Sanz M, and Agudo-Barriuso M. Microglial dynamics after axotomy-induced retinal ganglion cell death. J Neuroinflammation. (2017) 14:218. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0982-7

33. Hu X, Zhao GL, Xu MX, Zhou H, Li F, Miao Y, et al. Interplay between Müller cells and microglia aggravates retinal inflammatory response in experimental glaucoma. J Neuroinflammation. (2021) 18:303. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02366-x

34. Zhang ML, Zhao GL, Hou Y, Zhong SM, Xu LJ, Li F, et al. Rac1 conditional deletion attenuates retinal ganglion cell apoptosis by accelerating autophagic flux in a mouse model of chronic ocular hypertension. Cell Death Dis. (2020) 11:734. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-02951-7

35. Xu MX, Zhao GL, Hu X, Zhou H, Li SY, Li F, et al. P2X7/P2X4 receptors mediate proliferation and migration of retinal microglia in experimental glaucoma in mice. Neurosci Bull. (2022) 38:901–15. doi: 10.1007/s12264-022-00833-w

36. Ramírez AI, de Hoz R, Fernández-Albarral JA, Salobrar-Garcia E, Rojas B, Valiente-Soriano FJ, et al. Time course of bilateral microglial activation in a mouse model of laser-induced glaucoma. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:4890. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61848-9

37. Ebneter A, Casson RJ, Wood JP, and Chidlow G. Microglial activation in the visual pathway in experimental glaucoma: spatiotemporal characterization and correlation with axonal injury. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2010) 51:6448–60. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5284

38. Salkar A, Palanivel V, Basavarajappa D, Mirzaei M, Schulz A, Yan P, et al. Glial and immune dysregulation in glaucoma independent of retinal ganglion cell loss: a human post-mortem histopathology study. Acta Neuropathol Commun. (2025) 13:141. doi: 10.1186/s40478-025-02066-0

39. Rutigliani C, Tribble JR, Hagström A, Lardner E, Jóhannesson G, Stålhammar G, et al. Widespread retina and optic nerve neuroinflammation in enucleated eyes from glaucoma patients. Acta Neuropathol Commun. (2022) 10:118. doi: 10.1186/s40478-022-01427-3

40. Salkar A, Wall RV, Basavarajappa D, Chitranshi N, Parilla GE, Mirzaei M, et al. Glial cell activation and immune responses in glaucoma: A systematic review of human postmortem studies of the retina and optic nerve. Aging Dis. (2024) 15:2069–83. doi: 10.14336/AD.2024.0103

41. Thompson JL, McCool S, Smith JC, Schaal V, Pendyala G, Yelamanchili S, et al. Microglia remodeling in the visual thalamus of the DBA/2J mouse model of glaucoma. PloS One. (2025) 20:e0323513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0323513

42. Liang Q, Cheng X, Wang J, Owen L, Shakoor A, Lillvis JL, et al. A multi-omics atlas of the human retina at single-cell resolution. Cell Genom. (2023) 3:100298. doi: 10.1016/j.xgen.2023.100298

43. Wolf SA, Boddeke HW, and Kettenmann H. Microglia in physiology and disease. Annu Rev Physiol. (2017) 79:619–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034406

44. Colonna M and Butovsky O. Microglia function in the central nervous system during health and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Immunol. (2017) 35:441–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-051116-052358

45. Zhang Z, Peng S, Xu T, Liu J, Zhao L, Xu H, et al. Retinal microenvironment-protected rhein-GFFYE nanofibers attenuate retinal ischemia-reperfusion injury via inhibiting oxidative stress and regulating microglial/macrophage M1/M2 polarization. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2023) 10:e2302909. doi: 10.1002/advs.202302909

46. Glass CK, Saijo K, Winner B, Marchetto MC, and Gage FH. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell. (2010) 140:918–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.016

47. Walker DG and Lue LF. Immune phenotypes of microglia in human neurodegenerative disease: challenges to detecting microglial polarization in human brains. Alzheimers Res Ther. (2015) 7:56. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0139-9

48. Fan W, Huang W, Chen J, Li N, Mao L, and Hou S. Retinal microglia: Functions and diseases. Immunology. (2022) 166:268–86. doi: 10.1111/imm.13479

49. De I, Nikodemova M, Steffen MD, Sokn E, Maklakova VI, Watters JJ, et al. CSF1 overexpression has pleiotropic effects on microglia in vivo. Glia. (2014) 62:1955–67. doi: 10.1002/glia.22717

50. Wang M, Ma W, Zhao L, Fariss RN, and Wong WT. Adaptive Müller cell responses to microglial activation mediate neuroprotection and coordinate inflammation in the retina. J Neuroinflammation. (2011) 8:173. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-173

51. Keren-Shaul H, Spinrad A, Weiner A, Matcovitch-Natan O, Dvir-Szternfeld R, Ulland TK, et al. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of alzheimer’s disease. Cell. (2017) 169:1276–90.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.018

52. Krasemann S, Madore C, Cialic R, Baufeld C, Calcagno N, El Fatimy R, et al. The TREM2-APOE pathway drives the transcriptional phenotype of dysfunctional microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunity. (2017) 47:566–81.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.08.008

53. Pitts KM and Margeta MA. Myeloid masquerade: Microglial transcriptional signatures in retinal development and disease. Front Cell Neurosci. (2023) 17:1106547. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2023.1106547

54. Wang S, Tong S, Jin X, Li N, Dang P, Sui Y, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis of the retina under acute high intraocular pressure. Neural Regener Res. (2024) 19:2522–31. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.389363

55. Ramirez AI, de Hoz R, Salobrar-Garcia E, Salazar JJ, Rojas B, Ajoy D, et al. The role of microglia in retinal neurodegeneration: alzheimer’s disease, parkinson, and glaucoma. Front Aging Neurosci. (2017) 9:214. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00214

56. Bosco A, Steele MR, and Vetter ML. Early microglia activation in a mouse model of chronic glaucoma. J Comp Neurol. (2011) 519:599–620. doi: 10.1002/cne.22516

57. Chen D, Peng C, Ding XM, Wu Y, Zeng CJ, Xu L, et al. Interleukin-4 promotes microglial polarization toward a neuroprotective phenotype after retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Neural Regener Res. (2022) 17:2755–60. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.339500

58. Diemler CA, MacLean M, Heuer SE, Hewes AA, Marola OJ, Libby RT, et al. Microglia depletion leads to increased susceptibility to ocular hypertension-dependent glaucoma. Front Aging Neurosci. (2024) 16:1396443. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2024.1396443

59. Fracassi A, Marcatti M, Tumurbaatar B, Woltjer R, Moreno S, and Taglialatela G. TREM2-induced activation of microglia contributes to synaptic integrity in cognitively intact aged individuals with Alzheimer’s neuropathology. Brain Pathol. (2023) 33:e13108. doi: 10.1111/bpa.13108

60. Margeta MA, Yin Z, Madore C, Pitts KM, Letcher SM, Tang J, et al. Apolipoprotein E4 impairs the response of neurodegenerative retinal microglia and prevents neuronal loss in glaucoma. Immunity. (2022) 55:1627–44.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.07.014

61. Wang K, Peng B, and Lin B. Fractalkine receptor regulates microglial neurotoxicity in an experimental mouse glaucoma model. Glia. (2014) 62:1943–54. doi: 10.1002/glia.22715

62. Wu X, Yu N, Ye Z, Gu Y, Zhang C, Chen M, et al. Inhibition of cGAS-STING pathway alleviates neuroinflammation-induced retinal ganglion cell death after ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cell Death Dis. (2023) 14:615. doi: 10.1038/s41419-023-06140-0

63. Aires ID, Ribeiro-Rodrigues T, Boia R, Catarino S, Girão H, Ambrósio AF, et al. Exosomes derived from microglia exposed to elevated pressure amplify the neuroinflammatory response in retinal cells. Glia. (2020) 68:2705–24. doi: 10.1002/glia.23880

64. Bierlein ER, Smith JC, and Van Hook MJ. Mechanism for altered dark-adapted electroretinogram responses in DBA/2J mice includes pupil dilation deficits. Curr Eye Res. (2022) 47:897–907. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2022.2044055

65. Zeng S, Du L, Lu G, and Xing Y. CREG Protects Retinal Ganglion Cells loss and Retinal Function Impairment Against ischemia-reperfusion Injury in mice via Akt Signaling Pathway. Mol Neurobiol. (2023) 60:6018–28. doi: 10.1007/s12035-023-03466-w

66. Akopian A, Kumar S, Ramakrishnan H, Viswanathan S, and Bloomfield SA. Amacrine cells coupled to ganglion cells via gap junctions are highly vulnerable in glaucomatous mouse retinas. J Comp Neurol. (2019) 527:159–73. doi: 10.1002/cne.24074

67. Kendell KR, Quigley HA, Kerrigan LA, Pease ME, and Quigley EN. Primary open-angle glaucoma is not associated with photoreceptor loss. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (1995) 36:200–5.

68. Panda S and Jonas JB. Decreased photoreceptor count in human eyes with secondary angle-closure glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (1992) 33:2532–6.

69. Nork TM, Ver Hoeve JN, Poulsen GL, Nickells RW, Davis MD, Weber AJ, et al. Swelling and loss of photoreceptors in chronic human and experimental glaucomas. Arch Ophthalmol. (2000) 118:235–45. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.2.235

70. Ortín-Martínez A, Salinas-Navarro M, Nadal-Nicolás FM, Jiménez-López M, Valiente-Soriano FJ, García-Ayuso D, et al. Laser-induced ocular hypertension in adult rats does not affect non-RGC neurons in the ganglion cell layer but results in protracted severe loss of cone-photoreceptors. Exp Eye Res. (2015) 132:17–33. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.01.006

71. Ayata P and Schaefer A. Innate sensing of mechanical properties of brain tissue by microglia. Curr Opin Immunol. (2020) 62:123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2020.01.003

72. Zhang Y, Chen K, Sloan SA, Bennett ML, Scholze AR, O’Keeffe S, et al. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. (2014) 34:11929–47. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014

73. Solis AG, Bielecki P, Steach HR, Sharma L, Harman CCD, Yun S, et al. Mechanosensation of cyclical force by PIEZO1 is essential for innate immunity. Nature. (2019) 573:69–74. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1485-8

74. Zhu T, Guo J, Wu Y, Lei T, Zhu J, Chen H, et al. The mechanosensitive ion channel Piezo1 modulates the migration and immune response of microglia. iScience. (2023) 26:105993. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.105993

75. Zhang F, Mehta H, Choudhary HH, Islam R, and Hanafy KA. TRPV4 channel in neurological disease: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic potential. Mol Neurobiol. (2025) 62:3877–91. doi: 10.1007/s12035-024-04518-5

76. Redmon SN, Yarishkin O, Lakk M, Jo A, Mustafić E, Tvrdik P, et al. TRPV4 channels mediate the mechanoresponse in retinal microglia. Glia. (2021) 69:1563–82. doi: 10.1002/glia.23979

77. Pitha I, Du L, Nguyen TD, and Quigley H. IOP and glaucoma damage: The essential role of optic nerve head and retinal mechanosensors. Prog Retin Eye Res. (2024) 99:101232. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2023.101232

78. Zhang D, Chen S, Zhang Y, Qiu L, Du M, Song W, et al. Microglia drive peripapillary vascular density reduction in normal tension glaucoma by regulating the rpl17/stat5b/apoa1 axis. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2025):e07894. doi: 10.1002/advs.202507894

79. Tezel G. A broad perspective on the molecular regulation of retinal ganglion cell degeneration in glaucoma. Prog Brain Res. (2020) 256:49–77. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2020.05.027

80. Wong KY, Roy J, Fung ML, Heng BC, Zhang C, and Lim LW. Relationships between mitochondrial dysfunction and neurotransmission failure in alzheimer’s disease. Aging Dis. (2020) 11:1291–316. doi: 10.14336/AD.2019.1125

81. Tribble JR, Harder JM, Williams PA, and John SWM. Ocular hypertension suppresses homeostatic gene expression in optic nerve head microglia of DBA/2 J mice. Mol Brain. (2020) 13:81. doi: 10.1186/s13041-020-00603-7

82. Jassim AH, Nsiah NY, and Inman DM. Ocular Hypertension Results in Hypoxia within Glia and Neurons throughout the Visual Projection. Antioxidants (Basel). (2022) 11:888. doi: 10.3390/antiox11050888

83. Joshi AU, Minhas PS, Liddelow SA, Haileselassie B, Andreasson KI, Dorn GW 2nd, et al. Fragmented mitochondria released from microglia trigger A1 astrocytic response and propagate inflammatory neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci. (2019) 22:1635–48. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0486-0

84. Hayakawa K, Esposito E, Wang X, Terasaki Y, Liu Y, Xing C, et al. Transfer of mitochondria from astrocytes to neurons after stroke. Nature. (2016) 535:551–5. doi: 10.1038/nature18928

85. Catalani E, Brunetti K, Del Quondam S, and Cervia D. Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress to prevent the neurodegeneration of retinal ganglion cells. Antioxidants (Basel). (2023) 12:2011. doi: 10.3390/antiox12112011

86. Wu X, Pang Y, Zhang Z, Li X, Wang C, Lei Y, et al. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant peptide SS-31 mediates neuroprotection in a rat experimental glaucoma model. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). (2019) 51:411–21. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmz020

87. Selvam S, Kumar T, and Fruttiger M. Retinal vasculature development in health and disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. (2018) 63:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.11.001

88. Sterling JK, Adetunji MO, Guttha S, Bargoud AR, Uyhazi KE, Ross AG, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonist NLY01 reduces retinal inflammation and neuron death secondary to ocular hypertension. Cell Rep. (2020) 33:108271. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108271

89. Lorenzl S, Albers DS, Narr S, Chirichigno J, and Beal MF. Expression of MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-1 and their endogenous counterregulators TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 in postmortem brain tissue of Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. (2002) 178:13–20. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8019

90. Giebel SJ, Menicucci G, McGuire PG, and Das A. Matrix metalloproteinases in early diabetic retinopathy and their role in alteration of the blood-retinal barrier. Lab Invest. (2005) 85:597–607. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700251

91. Hsu JY, McKeon R, Goussev S, Werb Z, Lee JU, Trivedi A, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 facilitates wound healing events that promote functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. (2006) 26:9841–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1993-06.2006

92. Uckermann O, Wolf A, Kutzera F, Kalisch F, Beck-Sickinger AG, Wiedemann P, et al. Glutamate release by neurons evokes a purinergic inhibitory mechanism of osmotic glial cell swelling in the rat retina: activation by neuropeptide Y. J Neurosci Res. (2006) 83:538–50. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20760

93. Xing L, Yang T, Cui S, and Chen G. Connexin hemichannels in astrocytes: role in CNS disorders. Front Mol Neurosci. (2019) 12:23. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00023

94. Campagno KE, Lu W, Jassim AH, Albalawi F, Cenaj A, Tso HY, et al. Rapid morphologic changes to microglial cells and upregulation of mixed microglial activation state markers induced by P2X7 receptor stimulation and increased intraocular pressure. J Neuroinflammation. (2021) 18:217. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02251-7

95. Xue B, Xie Y, Xue Y, Hu N, Zhang G, Guan H, et al. Involvement of P2X(7) receptors in retinal ganglion cell apoptosis induced by activated Müller cells. Exp Eye Res. (2016) 153:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2016.10.005

96. Savio LEB, de Andrade Mello P, da Silva CG, and Coutinho-Silva R. The P2X7 receptor in inflammatory diseases: angel or demon? Front Pharmacol. (2018) 9:52. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00052

97. Ventura ALM, Dos Santos-Rodrigues A, Mitchell CH, and Faillace MP. Purinergic signaling in the retina: From development to disease. Brain Res Bull. (2019) 151:92–108. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2018.10.016

98. Campagno KE, Lu W, Sripinun P, Albalawi F, Cenaj A, and Mitchell CH. Retinal microglial cells increase expression and release of IL-1β when exposed to ATP. bioRxiv. (2024). doi: 10.1101/2024.06.25.600617

99. Nadal-Nicolás FM, Galindo-Romero C, Valiente-Soriano FJ, Barberà-Cremades M, deTorre-Minguela C, Salinas-Navarro M, et al. Involvement of P2X7 receptor in neuronal degeneration triggered by traumatic injury. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:38499. doi: 10.1038/srep38499

100. Zloh M, Kutilek P, Hejda J, Fiserova I, Kubovciak J, Murakami M, et al. Visual stimulation and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) have protective effects in experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis. Life Sci. (2024) 355:122996. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122996

101. Telegina DV, Kolosova NG, and Kozhevnikova OS. Immunohistochemical localization of NGF, BDNF, and their receptors in a normal and AMD-like rat retina. BMC Med Genomics. (2019) 12:48. doi: 10.1186/s12920-019-0493-8

102. Le YZ, Xu B, Chucair-Elliott AJ, Zhang H, and Zhu M. VEGF mediates retinal müller cell viability and neuroprotection through BDNF in diabetes. Biomolecules. (2021) 11:712. doi: 10.3390/biom11050712

103. Howell GR, Macalinao DG, Sousa GL, Walden M, Soto I, Kneeland SC, et al. Molecular clustering identifies complement and endothelin induction as early events in a mouse model of glaucoma. J Clin Invest. (2011) 121:1429–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI44646

104. Alarcon-Martinez L, Shiga Y, Villafranca-Baughman D, Belforte N, Quintero H, Dotigny F, et al. Pericyte dysfunction and loss of interpericyte tunneling nanotubes promote neurovascular deficits in glaucoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2022) 119:e2110329119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2110329119

105. Margeta MA, Lad EM, and Proia AD. CD163+ macrophages infiltrate axon bundles of postmortem optic nerves with glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. (2018) 256:2449–56. doi: 10.1007/s00417-018-4081-y

106. Williams PA, Braine CE, Foxworth NE, Cochran KE, and John SWM. GlyCAM1 negatively regulates monocyte entry into the optic nerve head and contributes to radiation-based protection in glaucoma. J Neuroinflammation. (2017) 14:93. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0868-8

107. Chen X, Lei F, Zhou C, Chodosh J, Wang L, Huang Y, et al. Glaucoma after ocular surgery or trauma: the role of infiltrating monocytes and their response to cytokine inhibitors. Am J Pathol. (2020) 190:2056–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.07.006

108. Chiu K, Yeung SC, So KF, and Chang RC. Modulation of morphological changes of microglia and neuroprotection by monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in experimental glaucoma. Cell Mol Immunol. (2010) 7:61–8. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.110

109. Guo M, Schwartz TD, Lawrence ECN, Lu J, Zhong A, Wu J, et al. Loss of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 reduced monocyte recruitment and preserved retinal ganglion cells in a mouse model of hypertensive glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. (2025) 254:110325. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2025.110325

110. Reddingius PF, Kelly SR, Ometto G, Garway-Heath DF, and Crabb DP. Does the visual field improve after initiation of intraocular pressure lowering in the United Kingdom glaucoma treatment study? Am J Ophthalmol. (2025) 269:346–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2024.08.023

111. Yamazaki Y, Zhao N, Caulfield TR, Liu CC, and Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: pathobiology and targeting strategies. Nat Rev Neurol. (2019) 15:501–18. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0228-7

112. Serrano-Pozo A, Das S, and Hyman BT. APOE and Alzheimer’s disease: advances in genetics, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. (2021) 20:68–80. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30412-9

113. Freeman EE, Bastasic J, Grant A, Leung G, Li G, Buhrmann R, et al. Inverse association of APOE ϵ4 and glaucoma modified by systemic hypertension: the canadian longitudinal study on aging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2022) 63:9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.63.13.9

114. Rangaraju S, Dammer EB, Raza SA, Rathakrishnan P, Xiao H, Gao T, et al. Identification and therapeutic modulation of a pro-inflammatory subset of disease-associated-microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. (2018) 13:24. doi: 10.1186/s13024-018-0254-8

115. Shi Y and Holtzman DM. Interplay between innate immunity and Alzheimer disease: APOE and TREM2 in the spotlight. Nat Rev Immunol. (2018) 18:759–72. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0051-1

116. Ge MM, Chen N, Zhou YQ, Yang H, Tian YK, and Ye DW. Galectin-3 in microglia-mediated neuroinflammation: implications for central nervous system diseases. Curr Neuropharmacol. (2022) 20:2066–80. doi: 10.2174/1570159X20666220201094547

117. Yu C, Lad EM, Mathew R, Shiraki N, Littleton S, Chen Y, et al. Microglia at sites of atrophy restrict the progression of retinal degeneration via galectin-3 and Trem2. J Exp Med. (2024) 221:e20231011. doi: 10.1084/jem.20231011

118. Rombaut A, Brautaset R, Williams PA, and Tribble JR. Intravitreal injection of the Galectin-3 inhibitor TD139 provides neuroprotection in a rat model of ocular hypertensive glaucoma. Mol Brain. (2024) 17:84. doi: 10.1186/s13041-024-01160-z

119. Soares LC, Al-Dalahmah O, Hillis J, Young CC, Asbed I, Sakaguchi M, et al. Novel galectin-3 roles in neurogenesis, inflammation and neurological diseases. Cells. (2021) 10:3047. doi: 10.3390/cells10113047

120. García-Revilla J, Boza-Serrano A, Espinosa-Oliva AM, Soto MS, Deierborg T, Ruiz R, et al. Galectin-3, a rising star in modulating microglia activation under conditions of neurodegeneration. Cell Death Dis. (2022) 13:628. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-05058-3

121. Puigdellívol M, Allendorf DH, and Brown GC. Sialylation and galectin-3 in microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Front Cell Neurosci. (2020) 14:162. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00162

122. Cockram TOJ, Puigdellívol M, and Brown GC. Calreticulin and galectin-3 opsonise bacteria for phagocytosis by microglia. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:2647. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02647

123. Wang SK, Xue Y, Rana P, Hong CM, and Cepko CL. Soluble CX3CL1 gene therapy improves cone survival and function in mouse models of retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2019) 116:10140–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901787116

124. Sennlaub F, Auvynet C, Calippe B, Lavalette S, Poupel L, Hu SJ, et al. CCR2(+) monocytes infiltrate atrophic lesions in age-related macular disease and mediate photoreceptor degeneration in experimental subretinal inflammation in Cx3cr1 deficient mice. EMBO Mol Med. (2013) 5:1775–93. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201302692

125. Combadière C, Feumi C, Raoul W, Keller N, Rodéro M, Pézard A, et al. CX3CR1-dependent subretinal microglia cell accumulation is associated with cardinal features of age-related macular degeneration. J Clin Invest. (2007) 117:2920–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI31692

126. Breen KT, Anderson SR, Steele MR, Calkins DJ, Bosco A, and Vetter ML. Loss of fractalkine signaling exacerbates axon transport dysfunction in a chronic model of glaucoma. Front Neurosci. (2016) 10:526. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00526

127. Yu C, Roubeix C, Sennlaub F, and Saban DR. Microglia versus monocytes: distinct roles in degenerative diseases of the retina. Trends Neurosci. (2020) 43:433–49. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.03.012

128. Zabel MK, Zhao L, Zhang Y, Gonzalez SR, Ma W, Wang X, et al. Microglial phagocytosis and activation underlying photoreceptor degeneration is regulated by CX3CL1-CX3CR1 signaling in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Glia. (2016) 64:1479–91. doi: 10.1002/glia.23016

129. Peng B, Xiao J, Wang K, So KF, Tipoe GL, and Lin B. Suppression of microglial activation is neuroprotective in a mouse model of human retinitis pigmentosa. J Neurosci. (2014) 34:8139–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5200-13.2014

130. Dagkalis A, Wallace C, Hing B, Liversidge J, and Crane IJ. CX3CR1-deficiency is associated with increased severity of disease in experimental autoimmune uveitis. Immunology. (2009) 128:25–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03046.x

131. Wang X, Zhao L, Zhang J, Fariss RN, Ma W, Kretschmer F, et al. Requirement for microglia for the maintenance of synaptic function and integrity in the mature retina. J Neurosci. (2016) 36:2827–42. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3575-15.2016

132. Zhou L, Xu Z, Lu H, Cho H, Xie Y, Lee G, et al. Suppression of inner blood-retinal barrier breakdown and pathogenic Müller glia activation in ischemia retinopathy by myeloid cell depletion. J Neuroinflammation. (2024) 21:210. doi: 10.1186/s12974-024-03190-9

133. Church KA, Rodriguez D, Vanegas D, Gutierrez IL, Cardona SM, Madrigal JLM, et al. Models of microglia depletion and replenishment elicit protective effects to alleviate vascular and neuronal damage in the diabetic murine retina. J Neuroinflammation. (2022) 19:300. doi: 10.1186/s12974-022-02659-9

134. Hilla AM, Diekmann H, and Fischer D. Microglia are irrelevant for neuronal degeneration and axon regeneration after acute injury. J Neurosci. (2017) 37:6113–24. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0584-17.2017

135. Chen Y, Lin Y, Vithana EN, Jia L, Zuo X, Wong TY, et al. Common variants near ABCA1 and in PMM2 are associated with primary open-angle glaucoma. Nat Genet. (2014) 46:1115–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.3078

136. Gharahkhani P, Burdon KP, Fogarty R, Sharma S, Hewitt AW, Martin S, et al. Common variants near ABCA1, AFAP1 and GMDS confer risk of primary open-angle glaucoma. Nat Genet. (2014) 46:1120–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.3079

137. Ban N, Lee TJ, Sene A, Choudhary M, Lekwuwa M, Dong Z, et al. Impaired monocyte cholesterol clearance initiates age-related retinal degeneration and vision loss. JCI Insight. (2018) 3:e120824. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.120824

Keywords: glaucoma, high intraocular pressure, microglia, retinal ganglion cell, intercellular communications

Citation: Chen L, Yang S, Wang D and Huang P (2025) The role of microglia in glaucoma - trigger and potential target. Front. Immunol. 16:1685495. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1685495

Received: 14 August 2025; Accepted: 27 October 2025;

Published: 11 November 2025.

Edited by:

Johnny Di Pierdomenico, University of Murcia, SpainReviewed by:

Francisco M. Nadal-Nicolás, National Eye Institute (NIH), United StatesKenji Sakamoto, Teikyo University, Japan

Zeeshan Ahmad, Wayne State University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Chen, Yang, Wang and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pingping Huang, MjAyMzI4MzAyMDE4OUB3aHUuZWR1LmNu; Di Wang, MTAxMjU0NDAxNkBxcS5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work and share senior authorship

Liugui Chen†

Liugui Chen† Pingping Huang

Pingping Huang