- 1School of Medicine, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan

- 2Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapy, Henry Ford Health, Detroit, MI, United States

Introduction: Steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease (SR-aGVHD) is a significant complication of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Extracorporeal Photopheresis (ECP) represents a key second-line option. Previous reviews have provided valuable insights, and recent studies allow for an updated synthesis of efficacy, safety, and patterns of ECP use in SR-aGVHD, including outcomes not fully analysed previously. This study aims to address the literature gap by providing a comprehensive updated review of the efficacy of ECP and its patterns of use in SR-aGVHD.

Materials and methods: A Systematic literature search was conducted as per PRISMA guidelines, up to September 2024, using the PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane databases. Studies investigating the use of ECP in the setting of chronic GVHD, GVHD prophylaxis, or first-line treatment of aGVHD were excluded. Meta-analyses using fixed and random effects models were employed to estimate the pooled effect sizes.

Results: Thirty-eight studies, including a total of 1249 participants, were included, and 29 were included in the quantitative analyses. Most studies focused on the adult population, and the majority used a retrospective single-arm study design (n = 30). Overall, skin, gut, and liver response rates were 72%, 89%, 54%, and 36%, respectively. The pooled steroid-sparing percentage was 66%. ECP showed significantly higher survival in patients with grade 2 GVHD compared with grades 3 and 4 (HR: 2.35, 95% CI: 1.67 – 3.29). ECP demonstrated a positive trend in overall survival compared to other treatments, but the results were not significant.

Conclusion: This review indicates that ECP is an effective treatment for SR-aGVHD, with favorable response and survival outcomes. However, due to the heterogeneity observed in the analyses among the studies, more controlled trials are needed to establish its effects in combination with other agents and against other regimens.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD42024585471.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a vital procedure used to treat several hematological, immunological, and hereditary conditions, by revitalizing the immune system after high-dose chemotherapy or irradiation (1). Despite the advent of newer prophylactic regimens, including post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy), 20-50% of HSCT patients develop acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD), a serious treatment complication of HSCT that significantly impacts patient survival (2–4). First-line treatment of aGVHD typically involves steroids, conventionally with prednisone or methylprednisolone at a starting dose of 1 to 2 mg/kg (5, 6). Unfortunately, a significant number of patients fail to respond to treatment, resulting in steroid-refractory aGVHD (SR-aGVHD), which is associated with a worse prognosis (7).

Extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP), an immunomodulatory cell therapy, is regarded as one of the main second-line treatment options for SR-aGVHD and involves exposing circulating leukocytes to 8-methoxypsoralen (8-MOP) and ultraviolet A (UVA) radiation upon reinfusion into the patient, which suppresses aGVHD through immunomodulatory pathways (8). These pathways promote a transition from pro- to anti-inflammatory cytokines, in addition to the upregulation of donor T regulatory cell (Treg) activity, suppressing alloreactive T-cells that mediate GVHD pathology (9, 10). Furthermore, ECP is associated with an excellent safety profile and limited immunosuppression, making it an ideal choice in this population and allowing its use alongside other agents (8). However, ECP is administered in multiple sessions across multiple weeks, posing a considerable burden to patients (9).

Regarding existing literature, two systematic reviews and meta-analyses (SR/MA) have examined the role of ECP in SR-aGVHD, by Zhang et al. and Abu-Dalle et al., both focusing mainly on prospective studies (11, 12), along with more recent narrative reviews by Greinix et al. and (8, 13, 17). These reviews have provided valuable insights, but the expanding body of clinical studies offers an opportunity for a comprehensive updated synthesis. Our objective is to evaluate the most recent evidence on the efficacy, safety, and patterns of use of ECP in SR-aGVHD, including outcomes that were not fully explored in earlier reviews.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO CRD42024585471).

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search across PubMed, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library for studies published from inception to September 2024, applying exclusion filters to remove non-human studies and non-English publications. Additionally, two reviewers screened the bibliographies of review articles and meta-analyses to identify any missed studies. The search strategy was adapted from a prior review on the same subject (14). A detailed description of the full-text search strategy is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Study selection

Studies were included if they focused on patients with steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) from any source and evaluated extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) as the intervention, with or without a comparator. Eligible studies must report at least one efficacy outcome such as overall response rate (ORR), complete, partial, or organ-specific response, duration of response (DOR), overall survival (OS), non-relapse mortality (NRM), and steroid-sparing effects. Accepted study designs included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), Interventional non-RCTs, case-control studies, and cohort studies. Studies were excluded if they were case reports, letters, comments, conference proceedings, or reviews. Studies were also excluded if they investigated ECP only as prophylaxis or first-line therapy.

Two independent reviewers initially screened the titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles for eligibility with any disagreement resolved through consensus. Subsequently, two other independent reviewers assessed the full-text articles of those selected during the initial screening. Any discrepancies between their findings were discussed and resolved until a consensus was reached.

Data extraction and quality assessment

We developed a comprehensive data extraction form to ensure the systematic collection of all relevant clinical information. The extracted data included study characteristics such as design, sample size, number of treatment arms, treatment assignment, study phase, and treatment doses/regimens. Additionally, patient-related details were collected, including age, gender, pre-transplant diagnosis, transplant source, aGvHD grade, organ involvement, and conditioning regimen, along with key outcomes. To maintain accuracy, two independent reviewers conducted the data extraction, resolving any discrepancies through consultation with a third reviewer.

Quality assessment was carried out using appropriate tools based on the study design. For interventional studies the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) was used (15). Observational studies with a control group were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), while a modified version was used for those without a control group (16). Two authors independently conducted the quality assessments, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached. We followed the guidelines for each assessment tool to evaluate the overall risk of bias in each study. Further details of the data extraction and quality assessment methods are discussed in the Supplementary Material S1; Supplementary Material 9–11).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R 4.3.3, utilizing the “meta”, “metafor”, and “metamedian” packages. Meta-analysis was conducted using both fixed-effect models (I² < 50%) and random-effects models (I² ≥ 50%). For proportional outcomes (e.g., response rates, steroid-sparing effects), the inverse variance method with the DerSimonian-Laird estimator was used to estimate the between-study variance (τ²). Confidence intervals for τ² and τ were calculated using the Jackson method. Additionally, the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation was applied to stabilize variance and ensure that proportions were properly modeled. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore differences in outcomes across categories (e.g., adult vs pediatric populations, treatment regimens).

For continuous outcomes (e.g., overall survival rates), hazard ratios (HRs) were pooled using the inverse variance method and the DerSimonian-Laird estimator for τ², with subgroup differences tested to explore potential moderators. The analysis of overall survival (OS) and non-relapse mortality (NRM) rates over time was stratified by year intervals (1, 2, and 4 years). The prediction interval for the random-effects model was derived based on the t-distribution, with degrees of freedom (df) set to 11 to account for variability among studies.

Meta-regression analysis was conducted using mixed-effects models for outcomes with sufficient study/arm numbers (k ≥ 10). This analysis aimed to investigate moderators, such as patient characteristics, treatment regimens, and publication year, on the primary outcomes/effect sizes. The results of the meta-regression are presented as univariate and multivariate models, with significance determined at p < 0.05.

Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s regression test and visualized through funnel plots. A significant bias was considered when the p-value of Egger’s test was below 0.05. To account for potential publication bias, the Trim and Fill method was applied, which adjusts the pooled estimates to correct for missing studies due to bias.

A meta-analysis of medians was also performed using the method of calculating the median of the difference of medians, weighted by sample size, to ensure the robustness of findings related to survival data. A 95% confidence level was applied for all median-based estimates. The analyses were considered significant if the p-value for the corresponding test was less than 0.05.

Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using the I² statistic, with values above 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity. Where appropriate, subgroup analyses were performed based on study characteristics, including patient age, GVHD grade, and ECP regimen.

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a significance threshold of p < 0.05 was used for all analyses.

Results

Study selection

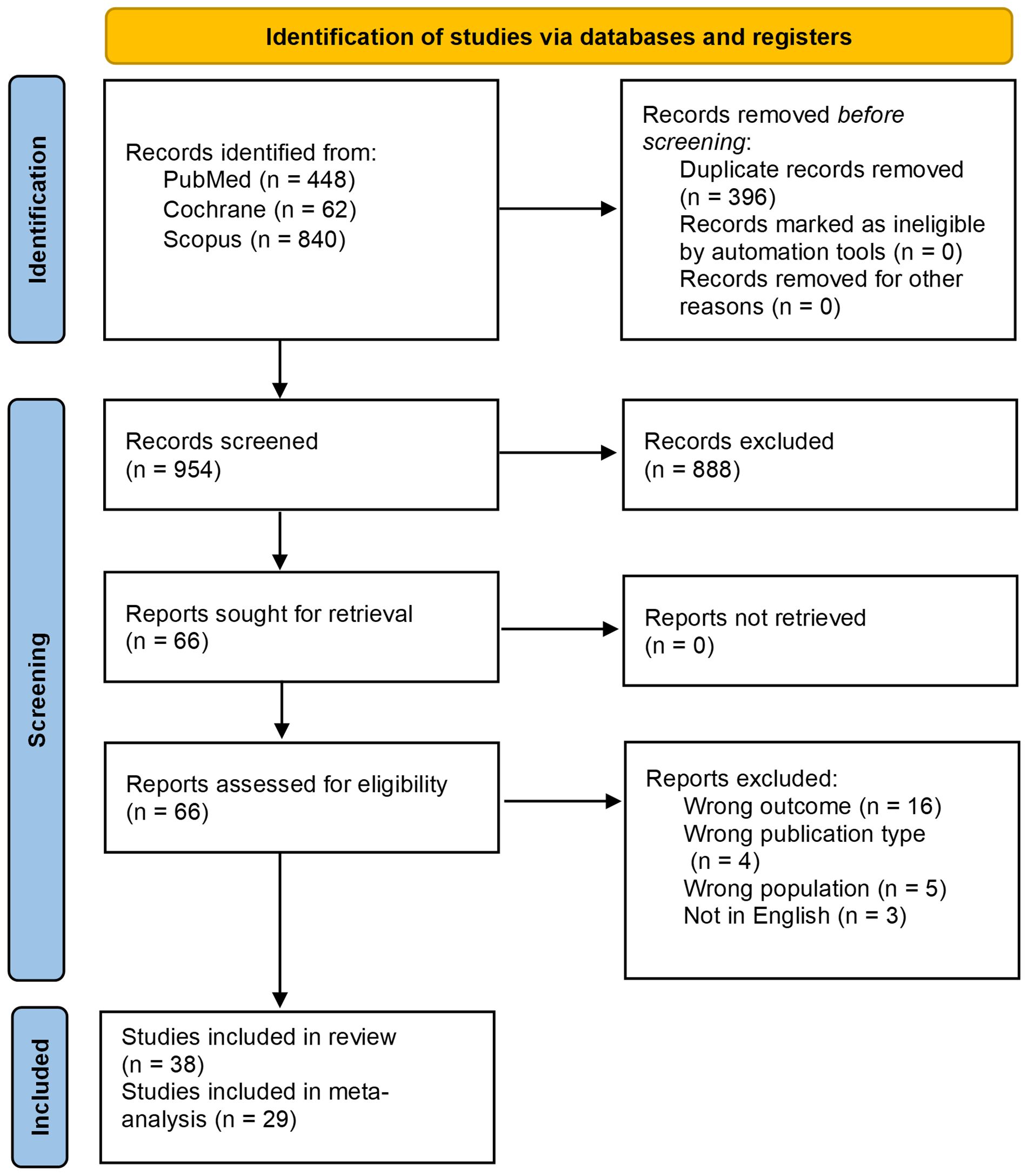

A total of 1350 records were identified through the initial database search. After excluding 396 duplicates, 888 records were further excluded through title & abstract screening. Full-text screening resulted in the exclusion of 28 records, including 16 studies due to having the wrong outcome, 4 for having the wrong publication type, 5 for having the wrong population, and 3 for being non-English studies. Ultimately, 38 studies were found to be eligible (17–54); however, 9 provided data that could not be used for the meta-analyses and so they were subsequently quantitatively excluded, resulting in the inclusion of 29 studies in the final meta-analyses. The PRIMSA flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Study characteristics

A total of 1249 patients were included in the study, with 30, 2, and 6 studies employing a retrospective cohort, prospective cohort, and a single-arm interventional study design, respectively (Table 1). Most studies were conducted on adult patients (n=23/38), with some studies involving both adults and pediatrics (n=5/38) (Supplementary Table 2). In-line ECP was the most commonly used technique (n=16/32), followed by off-line ECP (n=13/32) (Supplementary Table 3). Most studies reported on only steroid-refractory disease (n=19/32) with some also reporting on steroid-dependent (n=13/32) or steroid-intolerant or contraindicated disease (n=4/32) (Supplementary Table 4). The 1994 consensus conference criteria were the most used grading system (n=18/36) followed by the Glucksberg criteria (n=14/36) (55, 56), most studies were centered on grade II-IV GVHD with some also reporting on grade I GVHD (Supplementary Table 4). Conditions requiring transplant were reported in detail in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table 5), a more concise version is reported here with leukemia being the most common cause (Table 1). There was significant variation among the studies in terms of donor type, conditioning regimen, treatment combination, and treatment regimen, with the latter demonstrating considerable variation in terms of duration & frequency. (Supplementary Table 3, 6–8).

A detailed overview of the study characteristics and the quality assessment of the individual studies are provided in the supplementary material. (Supplementary Table 2, 9–11).

Meta analyses

Response rate

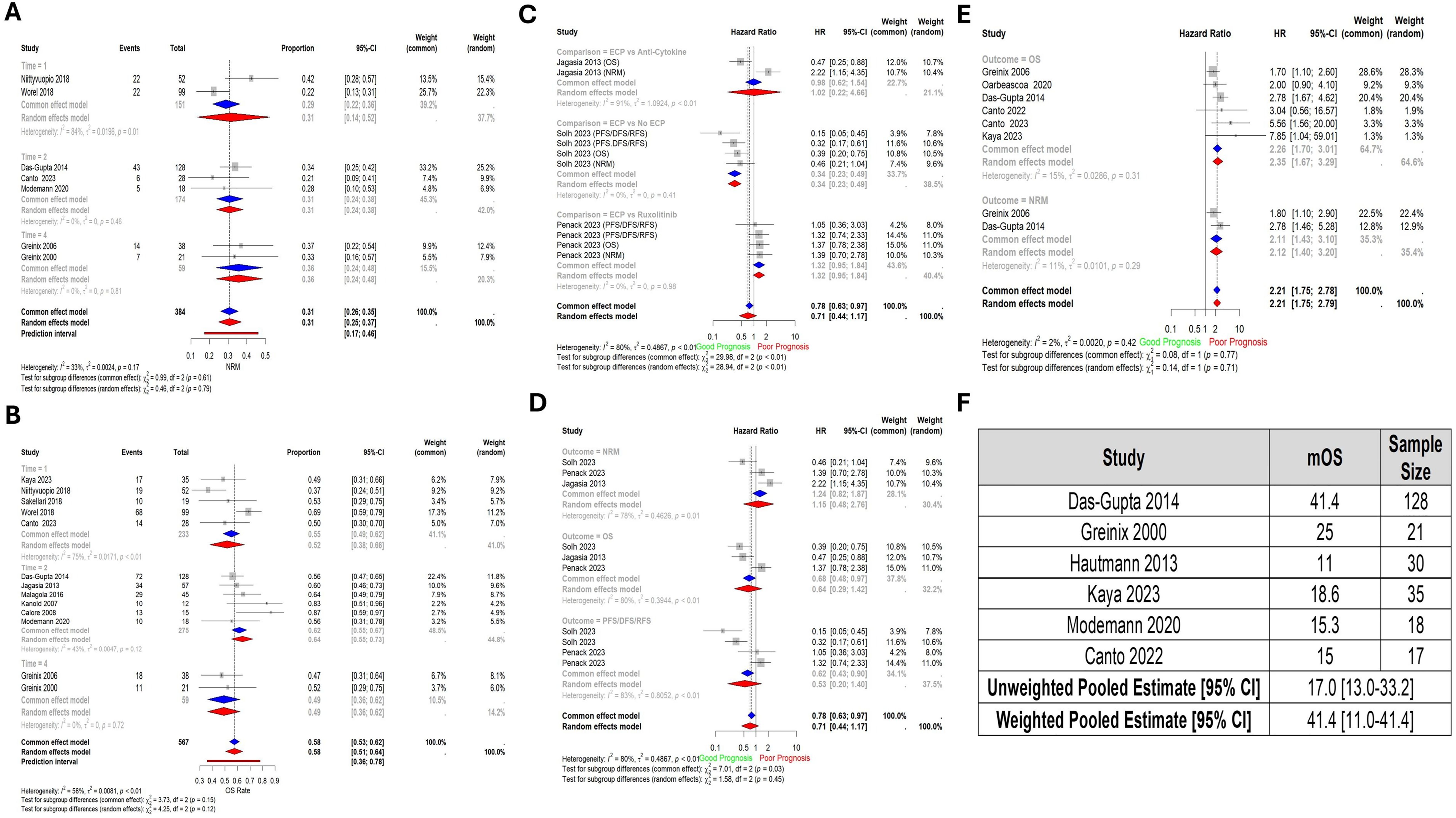

The ORR was pooled using a total of 28 studies (1007 patients), resulting in a pooled ORR of 72% (95% CI: 68% - 77%; Figure 2B). For the organ-specific responses, 17 studies (512 patients), 16 (467 patients), and 15 (458 patients) were included for the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and liver responses, respectively. The response rate for the skin was 89% (95% CI: 80% - 95%), the gastrointestinal tract was 54% (95% CI: 42%- 67%), and the liver was 36% (95% CI: 24% - 48%) (Figure 2A). Additionally, the pooled steroid-sparing rate was 66% (95% CI: 58% - 74%; 15 studies, 426 patients) (Figure 2C). Substantial heterogeneity was noted across the analyses, with I2 of 84%, 59%, and 54% for liver, skin, and gut responses, respectively. Similarly, ORR and the steroid-sparing rate showed significant heterogeneity (I² = 72% and 61%, respectively). (Figures 2A-C).

Figure 2. Forest plots of response rates (A) Organ-specific response rate. (B) Overall response rate (ORR). (C) Steroid-sparing rate.

Survival

The NRM at 1, 2, and 4 years was 31% (95% CI: 14% - 52%; 2 studies, 151 patients), 31% (95% CI: 24% - 38%; 3 studies, 174 patients), and 36% (95% CI: 24% - 48%; 2 studies; 59 patients), respectively (Figure 3A). Furthermore, the pooled OS rate at year 1 was 52% (95% CI: 38% - 66%), at year 2 64% (95% CI: 55% - 73%), and at year 4 was 49% (95% CI: 36% - 62%), and they included 5 studies (233 patients), 6 studies (275 patients), and 2 studies (59 patients) respectively (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Forest plots of survival outcomes (A) Non-relapse mortality by year (NRM). Time – Year (B) Overall survival rate by year. Time – Year (C) Pooled comparisons of ECP against other drugs by type of drug. Each of PFS, DFS, and RFS is represented under the same surrogate “PFS/DFS/RFS”. (D) Pooled comparisons of ECP against other drugs by outcome. (E) Pooled Hazard Ratio of Grade 3 and 4 Graft-versus-Host Disease compared to Grade 2. (F) Pooled median overall survival. Abbreviations: NRM – Non-relapse mortality; OS – Overall Survival; PFS – Progression-free survival; FFS – Failure-free survival; DFS – Disease-free survival; Time – Year; No ECP – Same regimen with the exclusion of ECP.

When ECP was compared to other treatments, there was no significant difference in terms of pooled prognostic outcomes (HR: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.44 - 1.17; 3 studies, 189 patients), or at the level of individual outcomes (NRM, OS, and PFS/DFS/RFS). However, when compared against specific comparators, ECP versus No ECP (HR: 0.34, 95% CI: 0.23-0.49); was significant (HRs for OS, NRM, and PFS/RFS/DFS pooled) (Figure 3C-D).

The pooled HR comparing OS between patients with grade II vs grade III and IV aGVHD showed a significantly worse OS in the latter group (HR: 2.35, 95% CI: 1.67 – 3.29; 6 studies, 323 patients) (Figure 3E).

The pooled median OS in the weighted model was 41.1 months (95% CI: 11.0-41.1) (Figure 3F).

Meta-regression analysis

Multiple meta-regression outcomes are summarized in Table 2. The table highlights significant heterogeneity across studies (I² values), with some outcomes showing strong moderator effects. Key findings include the influence of population type (Pediatrics vs. Mixed population vs. Adults), with studies focusing on pediatric populations showing superior survival, and studies containing mixed populations showing improved skin and gut responses. Additionally, a positive trend was seen in skin response with publication year, with more recent studies showing improved response. Some outcomes, like liver response and steroid-sparing, lack significant moderators, implying unexplained variability.

Table 2. Multiple Meta-Regression results. Combination: combination with other active treatments (yes/no). Reference categories: combination (No), Comparison (ECP vs Anti-Cytokine), Population (Adults). Variables included in models: publication year, classification (Glucksberg, MAGIC, etc.), combination, outcome (OS, NRM, PFS/RFS/DFS), and comparison.

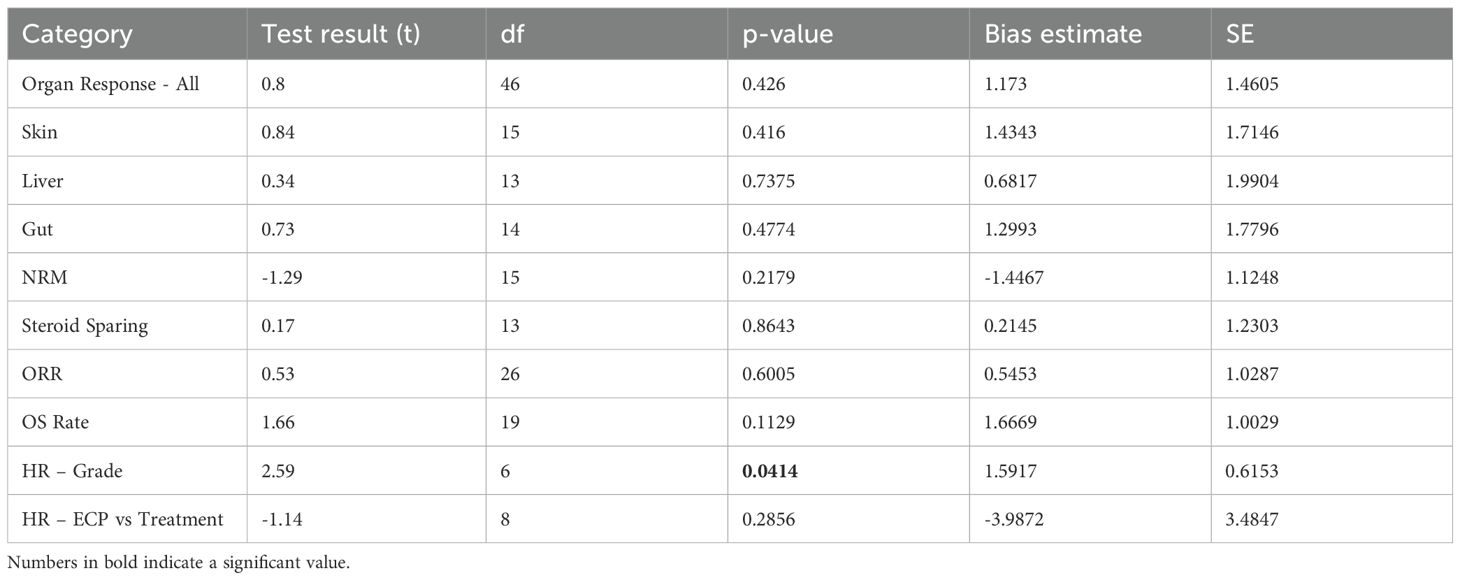

Publication bias

No significant publication bias was observed except for HR comparing patients with grade II vs grade III and IV aGVHD (bias estimate = 1.5917, p = 0.0414) (Table 3). Funnel plots are displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Funnel plots Abbreviations: NRM – Non-relapse mortality; OS – Overall Survival; ORR – Overall response rate; HR – Hazard ratio; G2 – Grade 2 GVHD; G(3 + 4) – Grade 3 and 4 GVHD.

Discussion

This study synthesized data from 38 studies comprising 1249 patients, of which 29 studies (1007 patients) were included in the meta-analyses. Unlike prior meta-analyses which were limited to prospective trials (11, 12), this study incorporated a wider array of data, including retrospective studies. This broader inclusion strategy improves the generalizability of the findings and allows for the analysis of novel outcomes such as time to ECP, treatment duration, and steroid-sparing effects, factors with important implications for clinical decision-making.

The pooled ORR to ECP was 72%, with a steroid-sparing effect observed in 66% of patients. These findings reinforce the role of ECP as a valuable second-line therapy for aGVHD, especially with the high steroid-sparing effect. Organ-specific responses varied significantly: skin involvement demonstrated the highest response rate (89%), while gastrointestinal (54%) and hepatic (36%) responses were more modest. These differences show the variable sensitivity of target organs to ECP and may have implications for tailored treatment strategies, which is consistent with the literature (8). This is likely due to the distribution and trafficking patterns of alloreactive T cells in skin versus gut/liver. In cutaneous GVHD, many of the pathogenic T cells bear skin-homing markers and recirculate through the peripheral blood en route to the skin. This means a larger fraction of skin-targeting effector T cells is accessible during ECP leukapheresis. By contrast, GVHD effectors that home to the gut or liver may reside more sequestered in those tissues, making them less exposed to ECP’s direct pro-apoptotic effects (57).

NRM remained relatively stable at around 31–36% at years 1, 2 and 4. This suggests that mortality rates due to causes other than relapse are similar and does not drastically increase over time as evident by the overlapping CI. This trend aligns with earlier findings (25). Furthermore, pooled OS increased from year 1 to year 2 (52% → 64%), which is consistent with previously reported data (51) and then declined slightly at year 4 (49%), possibly indicating late mortality due to relapse or complications. The decline after year 2 may reflect late post-treatment effects, disease progression, or comorbidities. Patients with grade III/IV aGVHD had significantly worse survival than those with grade II (HR: 2.35; 95% CI: 1.67–3.29). This indicates that advanced-grade disease nearly doubles the risk of death.

There were few comparative studies; however, the pooled results showed that ECP was not significantly different from pooled comparators overall (HR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.44–1.17) (43, 51). However, when ECP was directly compared to “No ECP”, it was significantly beneficial (HR: 0.34; 95% CI: 0.23–0.49). This indicates that ECP outperforms not receiving ECP, but its effect may be diluted when compared against other active therapies. In addition, a significant number of studies combined ECP with other active treatments, while others did not, and the meta-regression results showed that it did not affect the outcomes, with the exception of improved gut response in patients receiving active combinations (Table 2). However, these results were most likely influenced by the variations in the type of combinations and the number of patients who received such combinations from the entire population.

The limitations of this study include the retrospective nature of most of the included studies. Retrospective studies inherently have a higher risk of bias since the data collection, data entry, and data quality assurance were not planned ahead of time (58). Additionally, some clinical outcomes (such as ORR, complete, partial, or organ-specific response, DOR, OS, NRM, and steroid-sparing effects) were inconsistently reported or entirely absent, which might prevent a full assessment of the clinical impact of ECP. Furthermore, there was considerable clinical variation across studies regarding grading systems used to define aGVHD, ECP regimens, baseline characteristics, treatment duration and adjunctive therapies which may influence the variability of pooled estimates.

The meta-analysis exhibits considerable heterogeneity, particularly for liver response, ORR, and OS rate, as reflected by high I² values and significant residual heterogeneity. Some of these variations are explained by moderators such as population type (adults vs. mixed) and publication year for skin and gut responses. Interestingly, the pediatric population was associated with improved OS outcomes, indicating potential age-related variability in response. This finding contrasts with earlier reports that did not identify age as a significant predictor (59). However, for outcomes like liver response and steroid-sparing, none of the tested moderators could explain the heterogeneity, indicating unexplained differences, the heterogeneity in the latter could be explained by the lack of consistency in how it was defined across different studies. Additionally, publication bias was observed in HR comparing patients with grade II vs those with grade III and IV aGVHD and it may contribute to heterogeneity in this outcome.

While ECP offers a valuable second-line treatment for SR-aGVHD, its optimal role remains undefined due to a lack of standardized procedures and reporting. Future studies should prioritize investigating ECP in treatment regimens alongside other agents such as Ruxolitinib and comparative studies to further explore its optimal use. A global, prospective registry or randomized comparative studies may be essential to resolve current uncertainties and guide the use of ECP in SR-aGVHD.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ZM: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. AI: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. JY: Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. LA: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation. MN: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. MA: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. MZ: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SF: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1696862/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Balassa K, Danby R, and Rocha V. Haematopoietic stem cell transplants: principles and indications. Br J Hosp Med. (2019) 80:33–9. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2019.80.1.33

2. Rashid N, Krakow EF, Yeh AC, Oshima MU, Onstad L, Connelly-Smith L, et al. Late effects of severe acute graft-versus-host disease on quality of life, medical comorbidities, and survival. Transplant Cell Ther. (2022) 28:844.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.08.027

3. Sureda A, Corbacioglu S, Greco R, Kröger N, and Carreras E. The EBMT handbook: hematopoietic cell transplantation and cellular therapies (2024). Cham (CH: Springer. Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK608238/ (Accessed October 10, 2025).

4. Bolaños-Meade J, Hamadani M, Wu J, Malki MMA, Martens MJ, Runaas L, et al. Post-transplantation cyclophosphamide-based graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. (2023) 388:2338–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2215943

5. Mielcarek M, Storer BE, Boeckh M, Carpenter PA, McDonald GB, Deeg HJ, et al. Initial therapy of acute graft-versus-host disease with low-dose prednisone does not compromise patient outcomes. Blood. (2009) 113:2888–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168401

6. Messina C, Faraci M, de Fazio V, Dini G, Calò MP, and Calore E. Prevention and treatment of acute GvHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2008) 41:S65–70. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.57

7. Westin JR, Saliba RM, De Lima M, Alousi A, Hosing C, Qazilbash MH, et al. Steroid-refractory acute GVHD: predictors and outcomes. Adv Hematol. (2011) 2011:601953. doi: 10.1155/2011/601953

8. Greinix HT, Ayuk F, and Zeiser R. Extracorporeal photopheresis in acute and chronic steroid−refractory graft-versus-host disease: an evolving treatment landscape. Leukemia. (2022) 36:2558–66. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01701-2

9. Cho A, Jantschitsch C, and Knobler R. Extracorporeal photopheresis—An overview. Front Med. (2018) 5:236/full. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00236/full

10. Xia CQ, Campbell KA, and Clare-Salzler MJ. Extracorporeal photopheresis-induced immune tolerance: a focus on modulation of antigen-presenting cells and induction of regulatory T cells by apoptotic cells. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. (2009) 14:338–43. doi: 10.1097/mot.0b013e32832ce943

11. Zhang H, Chen R, Cheng J, Jin N, and Chen B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies for ECP treatment in patients with steroid-refractory acute GVHD. Patient Prefer Adherence. (2015) 9:105–11. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s76563

12. Abu-Dalle I, Reljic T, Nishihori T, Antar A, Bazarbachi A, Djulbegovic B, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis in steroid-refractory acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease: results of a systematic review of prospective studies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant. (2014) 20:1677–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.05.017

13. Asensi Cantó P, Sanz Caballer J, Solves Alcaína P, de la Rubia Comos J, and Gómez Seguí I. Extracorporeal photopheresis in graft-versus-host disease. Transplant Cell Ther. (2023) 29:556–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2023.07.001

14. Buder K, Zirngibl M, Bapistella S, Meerpohl JJ, Strahm B, Bassler D, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis versus standard treatment for acute graft-versus-host disease after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2022) 9:CD009759. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd009759.pub4

15. Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Brugere C, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, et al. Validation of a methodological index (MINORS) for non-randomized studies. Ann Chir. (2003) 73:128. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x

16. Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. (2010) 25:603–5.

17. Asensi Cantó P, Sanz Caballer J, Fuentes Socorro C, Solves Alcaína P, Lloret Madrid P, Solís Ruíz J, et al. Role of extracorporeal photopheresis in the management of children with graft-vs-host disease. J Clin Apheresis. (2022) 37:573–83. doi: 10.1002/jca.22012\

18. Asensi Cantó P, Sanz Caballer J, Sopeña Pell-Ilderton C, Solís Ruiz J, Lloret Madrid P, Villalba Montaner M, et al. Real-world experience in extracorporeal photopheresis for adults with graft-versus-host disease. Transplant Cell Ther. (2023) 29:765. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2023.09.001

19. Axt L, Naumann A, Toennies J, Haen SP, Vogel W, Schneidawind D, et al. Retrospective single center analysis of outcome, risk factors and therapy in steroid refractory graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2019) 54:1805–14. doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0544-y

20. Batgi H, Dal MS, Erkurt MA, Kuku I, Kurtoglu E, Hindilerden IY, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis in the treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease: A multicenter experience. Transfus Apher Sci. (2021) 60. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2021.103242

21. Berger M, Pessolano R, Albiani R, Asaftei S, Barat V, Carraro F, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis for steroid resistant graft versus host disease in pediatric patients: a pilot single institution report. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2007) 29:678–87. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31814d66f5

22. Berger M, Albiani R, Sini B, and Fagioli F. Extracorporeal photopheresis for graft-versus-host disease: the role of patient, transplant, and classification criteria and hematologic values on outcome—results from a large single-center study. Transfusion (Paris). (2015) 55:736–47. doi: 10.1111/trf.12900

23. Besnier DP, Chabannes D, Mahé B, Mussini JMG, Baranger T a. R, Muller JY, et al. TREATMENT OF GRAFT-VERSUS-HOST DISEASE BY EXTRACORPOREAL PHOTOCHEMOTHERAPY: A pilot study: 1. Transplantation. (1997) 64:49. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199707150-00010

24. Calore E, Calò A, Tridello G, Cesaro S, Pillon M, Varotto S, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy may improve outcome in children with acute GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2008) 42:421–5. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.174

25. Das-Gupta E, Greinix H, Jacobs R, Zhou L, Savani BN, Engelhardt BG, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis as second-line treatment for acute graft-versus-host disease: impact on six-month freedom from treatment failure. Haematologica. (2014) 99:1746–52. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.108217

26. Garban F, Drillat P, Makowski C, Jacob MC, Richard MJ, Favrot M, et al. Extracorporeal chemophototherapy for the treatment of graft-versus-host disease: hematologic consequences of short-term, intensive courses. Haematologica. (2005) 90:1096–101.

27. González Vicent M, Ramirez M, Sevilla J, Abad L, and Díaz MA. Analysis of clinical outcome and survival in pediatric patients undergoing extracorporeal photopheresis for the treatment of steroid-refractory GVHD. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2010) 32:589. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181e7942d

28. Greinix HT, Volc-Platzer B, Rabitsch W, Gmeinhart B, Guevara-Pineda C, Kalhs P, et al. Successful use of extracorporeal photochemotherapy in the treatment of severe acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. (1998) 92:3098–104. doi: 10.1182/blood.V92.9.3098

29. Greinix HT, Volc-Platzer B, Kalhs P, Fischer G, Rosenmayr A, Keil F, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy in the treatment of severe steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease: a pilot study. Blood. (2000) 96:2426–31. doi: 10.1182/blood.V96.7.2426

30. Greinix HT, Knobler RM, Worel N, Schneider B, Schneeberger A, Hoecker P, et al. The effect of intensified extracorporeal photochemotherapy on long-term survival in patients with severe acute graft-versus-host disease. Haematologica. (2006) 91:405–8.

31. Hautmann AH, Wolff D, Hahn J, Edinger M, Schirmer N, Ammer J, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis in 62 patients with acute and chronic GVHD: results of treatment with the COBE Spectra System. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2013) 48:439–45. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.156

32. Jagasia M, Greinix H, Robin M, Das-Gupta E, Jacobs R, Savani BN, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis versus anticytokine therapy as a second-line treatment for steroid-refractory acute GVHD: a multicenter comparative analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant. (2013) 19:1129–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.04.018

33. Kanold J, Merlin E, Halle P, Paillard C, Marabelle A, Rapatel C, et al. Photopheresis in pediatric graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic marrow transplantation: clinical practice guidelines based on field experience and review of the literature. Transfusion (Paris). (2007) 47:2276–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01469.x

34. Kaya A, Erkurt MA, Kuku İ, Kaya E, Berber İ, Biçim S, et al. Effect of extracorporeal photopheresis on survival in acute graft versus host disease. J Clin Apheresis. (2023) 38:602–10. doi: 10.1002/jca.22071

35. Kitko CL, Abdel-Azim H, Carpenter PA, Dalle JH, Diaz-de-Heredia C, Gaspari S, et al. A prospective, multicenter study of closed-system extracorporeal photopheresis for children with steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. Transplant Cell Ther. (2022) 28:261.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.01.025

36. Malagola M, Cancelli V, Skert C, Leali PF, Ferrari E, Tiburzi A, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis for treatment of acute and chronic graft versus host disease: an italian multicentric retrospective analysis on 94 patients on behalf of the gruppo italiano trapianto di midollo osseo. Transplantation. (2016) 100:e147. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001466

37. Messina C, Locatelli F, Lanino E, Uderzo C, Zacchello G, Cesaro S, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for paediatric patients with graft-versus-host disease after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. (2003) 122:118–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04401.x

38. Michallet M, Sobh M, Deloire A, Revesz D, Chelgoum Y, El-Hamri M, et al. Second line extracorporeal photopheresis for cortico-resistant acute and chronic GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematological Malignancies: Long-term results from a real-life study. Transfus Apher Sci. (2024) 63. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2024.103899

39. Modemann F, Ayuk F, Wolschke C, Christopeit M, Janson D, von Pein UM, et al. Ruxolitinib plus extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) for steroid refractory acute graft-versus-host disease of lower GI-tract after allogeneic stem cell transplantation leads to increased regulatory T cell level. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2020) 55:2286–93. doi: 10.1038/s41409-020-0952-z

40. Niittyvuopio R, Juvonen E, Heiskanen J, Lindström V, Nihtinen A, Sahlstedt L, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis in the treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease: a single-center experience. Transfusion (Paris). (2018) 58:1973–9. doi: 10.1111/trf.14649

41. Nygaard M, Karlsmark T, Andersen NS, Schjødt IM, Petersen SL, Friis LS, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis is a valuable treatment option in steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent acute graft versus host disease—experience with three different approaches. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2019) 54:150–4. doi: 10.1038/s41409-018-0262-x

42. Oarbeascoa G, Lozano ML, Guerra LM, Amunarriz C, Saavedra CA, Garcia-Gala JM, et al. Retrospective multicenter study of extracorporeal photopheresis in steroid-refractory acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2020) 26:651–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.12.769

43. Penack O, Peczynski C, Boreland W, Lemaitre J, Afanasyeva K, Kornblit B, et al. ECP versus ruxolitinib in steroid-refractory acute GVHD – a retrospective study by the EBMT transplant complications working party. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1283034/full. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1283034/full

44. Perfetti P, Carlier P, Strada P, Gualandi F, Occhini D, Van Lint MT, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis for the treatment of steroid refractory acute GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2008) 42:609–17. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.221

45. Perotti C, Del Fante C, Tinelli C, Viarengo G, Scudeller L, Zecca M, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy in graft-versus-host disease: a longitudinal study on factors influencing the response and survival in pediatric patients. Transfusion (Paris). (2010) 50:1359–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02577.x

46. Reschke R, Zimmerlich S, Döhring C, Behre G, and Ziemer M. Effective extracorporeal photopheresis of patients with transplantation induced acute intestinal gvHD and bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Biomedicines. (2022) 10:1887. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10081887

47. Rubegni P, Feci L, Poggiali S, Marotta G, D’Ascenzo G, Murdaca F, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis: a useful therapy for patients with steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease but not for the prevention of the chronic form. Br J Dermatol. (2013) 169:450–7. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12332

48. Sakellari I, Gavriilaki E, Batsis I, Mallouri D, Panteliadou AK, Lazaridou A, et al. Favorable impact of extracorporeal photopheresis in acute and chronic graft versus host disease: Prospective single-center study. J Clin Apheresis. (2018) 33:654–60. doi: 10.1002/jca.21660

49. Salvaneschi L, Perotti C, Zecca M, Bernuzzi S, Viarengo G, Giorgiani G, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for treatmentof acute and chronic GVHD in childhood. Transfusion (Paris). (2001) 41:1299–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41101299.x

50. Smith EP, Sniecinski I, Dagis AC, Parker PM, Snyder DS, Stein AS, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for treatment of drug-resistant graft-vs.-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant. (1998) 4:27–37. doi: 10.1016/S1083-8791(98)90007-6

51. Solh MM, Farnham C, Solomon SR, Bashey A, Morris LE, Holland HK, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) improves overall survival in the treatment of steroid refractory acute graft-versus-host disease (SR aGvHD). Bone Marrow Transplant. (2023) 58:168–74. doi: 10.1038/s41409-022-01860-x

52. Ussowicz M, Musiał J, Mielcarek M, Tomaszewska A, Nasiłowska-Adamska B, Kałwak K, et al. Steroid-sparing effect of extracorporeal photopheresis in the therapy of graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transplant Proc. (2013) 45:3375–80. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.07.053

53. Winther-Jørgensen S, Nygaard M, Heilmann C, Ifversen M, Sørensen K, Müller K, et al. Feasibility of extracorporeal photopheresis in pediatric patients with graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. (2019) 23:e13416. doi: 10.1111/petr.13416

54. Worel N, Lehner E, Führer H, Kalhs P, Rabitsch W, Mitterbauer M, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis as second-line therapy for patients with acute graft-versus-host disease: does the number of cells treated matter? Transfusion (Paris). (2018) 58:1045–53. doi: 10.1111/trf.14506

55. Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 Consensus conference on acute GVHD grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. (1995) 15:825–8.

56. Glucksberg H, Storb R, Fefer A, Buckner CD, Neiman PE, Clift RA, et al. Clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of marrow from HL-A-matched sibling donors. Transplantation. (1974) 18:295–304. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197410000-00001

57. Engelhardt BG, Jagasia M, Savani BN, Bratcher NL, Greer JP, Jiang A, et al. Regulatory T cell expression of CLA or α4β7 and skin or gut acute GVHD outcomes. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2010) 46:436. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.127

58. Norvell DC. Study types and bias—Don’t judge a study by the abstract’s conclusion alone. Evid-Based Spine-Care J. (2010) 1:7. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1100908

Keywords: acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD), steroid refractory acute graft-versus-host disease, extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP), systematic review, meta-analysis, meta-regression

Citation: Muhanna Z, Issa A, Yasin J, Alkuttob L, Niss M, Alsufi M, Al Zyoud M and Farhan S (2025) The efficacy of extracorporeal photopheresis in the treatment of steroid refractory acute graft-versus-host disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 16:1696862. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1696862

Received: 01 September 2025; Accepted: 13 November 2025; Revised: 11 October 2025;

Published: 16 December 2025.

Edited by:

Agnieszka Tomaszewska, Medical University of Warsaw, PolandReviewed by:

Olivier Hequet, Établissement Français du Sang (EFS), FrancePedro Asensi Cantó, Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Muhanna, Issa, Yasin, Alkuttob, Niss, Alsufi, Al Zyoud and Farhan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Muntaser Al Zyoud, bXVudGFzZXJ6eW91ZEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†ORCID: Zaid Muhanna, orcid.org/0009-0008-5633-687X

Ahmad Issa, orcid.org/0009-0000-3102-808X

Jehad Yasin, orcid.org/0000-0002-9205-2988

Leen Alkuttob, orcid.org/0009-0007-8783-5682

Maya Niss, orcid.org/0009-0006-9480-6364

Muaath Alsufi, orcid.org/0009-0005-8564-7034

Muntaser Al Zyoud, orcid.org/0000-0001-5341-8468

Zaid Muhanna

Zaid Muhanna Ahmad Issa

Ahmad Issa Jehad Yasin

Jehad Yasin Leen Alkuttob

Leen Alkuttob Maya Niss

Maya Niss Muaath Alsufi

Muaath Alsufi Muntaser Al Zyoud

Muntaser Al Zyoud Shatha Farhan

Shatha Farhan