Abstract

This study evaluated the impact of donor age on clinical outcomes in 274 patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) haplo-HCT using PTCY-based prophylaxis. Median patient age was 53 years, with 42.6% classified as high-risk AML. The median donor age of 38 years; 31% were under 30. An optimal donor age cut-off of 30 years was identified through ROC analysis. Patients receiving grafts from younger donors (<30 years) showed lower rates of aGVHD grade II–IV (3.0% vs. 19.9%, p < 0.001) and grade III–IV (1.5% vs. 10.2%, p = 0.034), with no differences in cGVHD or relapse rates. Overall survival (OS) was higher in the younger donor group (2-year: 80.6% vs. 64.3%, p = 0.011), along by lower non-relapse mortality (NRM) (2-year: 11.1% vs. 23.2%, p = 0.031). Multivariate analysis confirmed donor age ≥30 years as an independent adverse factor for OS (HR: 1.88, p = 0.019) and NRM (HR: 2.06, p = 0.049), along with older recipient age, higher HCT-CI score, and high-risk AML. These findings suggest that younger donor age contributes to improved survival, primarily through reduced NRM and aGVHD, supporting prioritization of younger donors when multiple haploidentical options are available to optimize transplant outcomes.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) is a potentially curative strategy for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The effectiveness of allo-HCT in AML patients resides in the anti-leukemia cytotoxicity gained from the conditioning regimen and the allogeneic donor-cell graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect. Furthermore, due to its efficacy in achieving long-term disease control, the indication for allo-HCT in AML patients has been expanding (1). This is largely due to advances in induction therapies, the availability of clinical trials, and the growing number of older patients now eligible for curative-intent therapies.

Post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy)-based prophylaxis has become a widely adopted strategy for preventing graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in haploidentical allo-HCT (haplo- HCT). The introduction of PTCy has played a transformative role in expanding access to allo- HCT by making haplo-HCT a viable and safer alternative in the absence of matched donors (2). However, donor selection in the haplo-HCT setting remains complex, and optimal criteria are still under investigation (3). Among various donor characteristics, donor age has emerged as a significant factor impacting transplant outcomes. Younger donors are generally associated with lower rates of chronic GVHD and better overall survival, making age a key consideration in donor selection. As haplo-HCT increases access to transplant for patients who previously lacked suitable donors, understanding the role of donor age and other clinical variables becomes increasingly important to refine donor choice and improve patient outcomes (4).

The present study aims to investigate the impact of donor age in patients with AML undergoing haplo-HCT. Specifically, it seeks to identify how donor age affects clinical outcomes, transplant-related toxicity, GVHD incidence, and disease relapse. Ultimately, the goal is to generate evidence that can support donor selection in the haploidentical setting, especially in cases where more than one potential donor is available and age becomes a distinguishing factor.

Methods

Study design and patient selection

This is a retrospective and multicenter, registry-based study sponsored by the Grupo Español de Trasplante Hematopoyético y Terapia Celular (GETH-TC), a non-profit scientific society comprising members from all institutions performing HCT in Spain and Portugal. All institutions members of the GETH-TC were invited to participate, and16 transplant centers affiliated with GETH-TC participated in the study.

The study sample included 274 adult AML patients who underwent their first peripheral blood (PB) haplo-HCT at the participant institutions between 2011 and 2022. Retrospective data were collected through retrospective chart review and updated in December 2024. Data collection and management were performed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted by GETH-TC. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona and adhered to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. No external funding was received.

Donor election practices across institutions, allo-HCT information and main definitions

Each transplant center followed their internal donor selection methodology during the study period. High resolution DNA typing for HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1 was conducted in recipients and donors. All patients underwent allo-HCT from haploidentical first-degree relative donors. An HLA- matched sibling donor (MSD) followed by a 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donor (MUD) were generally preferred upfront, and haploidentical donors were considered in the absence of a HLA-matched donors. Donor age was considered the main explanatory variable for the study conduction. Unfortunately, data related to donor/recipient CMV serostatus and ABO compatibility were not recorded. Induction therapies, eligibility criteria for allo-HCT, donor selection, conditioning regimens, and GVHD prophylaxis followed the standard protocols of each participating institution. Conditioning regimen intensity was tailored to each patient’s age and comorbidities. Acute and chronic GVHD (aGVHD and cGVHD) were graded according to established criteria. Complete remission (CR) and disease relapse were determined by the treating physician and recorded in the database.

Statistical analysis

The primary objective of this study was to assess the impact of donor age on outcomes, including overall survival (OS) and non-relapse mortality (NRM). Donor age was analyzed as a continuous variable and as a dichotomized variable, using a 30-year cut-off determined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Additional relevant outcomes included the cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR), cumulative incidence of GVHD, and GVHD-free/relapse-free survival (GRFS).

Continuous variables were assessed using Student’s T-test or appropriate non-parametric methods. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages and compared using Fisher’s exact test. OS was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, while NRM was estimated using the cumulative incidence function. The cumulative incidence of GVHD was calculated accounting for death and relapse as competing events. CIR and other post-transplant complications were analyzed death as competing event. GRFS was defined as the time from transplantation to the first occurrence of grade III–IV a GVHD, moderate/severe cGVHD, disease relapse, or death from any cause. Patients alive and free from these events were censored at last follow-up. The impact of donor age on OS and NRM was assessed with univariate and multivariable regression analyses (UVA and MVA). Variables found significant in the univariate analyses, or deemed clinically relevant, were included in the MVA. The proportionality assumption was evaluated using Schoenfeld test, with no violation detected.

All p-values were two-sided, with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using RStudio (version 2024.04.4), EZR, and GraphPad Prism 10.

Results

Patient characteristics and main outcomes

Baseline characteristics of patients and donors are summarized in Table 1. Among the 274 patients included, the median age was 53 years (range, 17–74), with 62 (22.6%) patients over 64 years. A total of 123 (45%) patients were female, and 99 (36.8%) had a Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Comorbidity Index (HCT-CI) > 2. According to the European LeukemiaNet (ELN) classification (2017 or 2022 depending on the date of diagnosis), 116 (42.6%) patients were classified as high-risk.

Table 1

| Variables | All patients N=274 | Donor age < 30 years N=85 | Donor age ≥ 30 years N=189 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range)(years) Older ≥65 years, total (%) |

53 (17-74) 62 (22.6) |

53 (17-69) 10 (11.8) |

53 (17-74) 52 (27.5) |

0.916 0.004 |

| Sex, total (%) Female |

123 (44.9) | 35 (41.2) | 88 (46.6) | 0.433 |

| ELN1 Classification, total (%) I-II III |

156 (57.4) 116 (42.6) |

52 (61.2) 33 (38.8) |

104 (55.6) 83 (48.7) |

0.429 |

| Disease status prior allo-HCT2, total (%) Complete Remission 1 Complete Remission 2 or more |

220 (80.3) 54 (19.7) |

68 (80) 17 (20) |

163 (83.2) 37 (19.6) |

1 |

| HCT-CI3 ≥3, total (%) | 99 (36.8) | 29 (34.1) | 70 (38) | 0.588 |

| Intensity, total (%) Myeloablative (MAC) Reduced intensity (RIC) |

145 (52.9) 129 (47.1) |

48 (56.5) 37 (43.5) |

97 (51.3) 92 (48.7) |

0.436 |

| Transplantation period After 2020 |

115 (42.1) |

35 (41.2) |

80 (42.3) |

0.91 |

| GVHD4 Prophylaxis PTCY5-CNI6 PTCY-CNI MMF7 PTCY Sir8 PTCY-Sir-MMF |

27 (10.1) 238 (89.1) 1 (0.4) 1 (0.4) |

8 (9.6) 75 (90.4) 0 (0) 0 (0) |

19 (10.3) 163 (88.6) 1 (0.5) 1 (0.5) |

1 |

| Post-HCT Follow-up, median (IQR)(days) | 35.5 (7.2-52.7) | 39.1 (15.6-60) | 34 (6.3-49.1) | 0.195 |

| Donor Information Age, median (range)(years) Female to Male Stem Cell Products, total (%) Cryopreservation, total (%) |

38 (13-75) 45 (16.4) 49 (24.1) |

24 (13-30) 15 (17.6) 18 (28.1) |

42 (31-75) 30 (15.9) 31 (22.1) |

<0.001 0.726 0.38 |

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort and according to donor age.

1ELN, European LeukemiaNet risk classification. 2Allo-HCT, allogenic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. 3HCT-CI, Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (HCT)-specific Comorbidity Index. 4GVHD, Graft Versus Host Disease. 5PTCy, Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide. 6CNI, Calcineurin inhibitor. 7MMF, Mycophenolate mofetil. 8Sir, Sirolimus.

Values highlighted in bold indicate a statistically significant p value.

At transplant, 220 (80.3%) patients were in first morphological remission and 2 (0.7%) underwent the procedure with active disease. MAC regimens were administered to 145 (53%) patients, and all allo-HCT were performed with PTCY-based prophylaxis. No patient received antithymocyte globulin in the conditioning regimen. Overall, with a median follow-up of 35.5 months, 60 (22.0%) patients experienced disease relapse and 103 (37.6%) patients died. For the entire cohort, the estimated 2-year OS, NRM and CIR rates were 68.5%, 19.4%, and 19.9%, respectively.

Donor age cut-off determination and impact on outcomes

The median donor age was 38 years (range, 13–75). Overall, 49 (17.9%) donors were female, and in 46 (16.4%) cases, female donors provided grafts to male recipients. All hematopoietic stem cell donations were collected from peripheral blood. In univariate analysis Table 2A older donor age (continuous variable) was associated with lower OS (HR: 1.01; 95% CI: 1.01–1.03; p = 0.041) and higher NRM (HR: 1.02; 95% CI: 1.01–1.04; p = 0.009). Importantly, donor age as a continuous variable retained statistical significance in the multivariate analysis for both OS and NRM (HR: 1.034, p = 0.022; HR: 1.04, p = 0.003, respectively).

Table 2A

| Univariate analysis | OS1 HR3 (95% CI4) | P value | NRM2 HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Continuous Older than 59 years (vs. younger) |

1.032 (1.015-1.05) 1.907 (1.273-2.855) |

<0.001 0.001 |

1.037 (1.014-1.061) 1.891 (1.118-3.196) |

0.002 0.017 |

| Donor Information Median Age Older than 29 years (vs. younger) Female to Male Stem Cell Products |

1.015 (1.001-1.03) 1.638 (1.025-2.615) 0.907 (0.591-1.392) |

0.041 0.009 0.274 |

1.024 (1.006-1.043) 2.056 (1.071-3.946) 1.335 (0.778-2.29) |

0.009 0.03 0.31 |

| ELN5 Classification III (vs I-II) |

1.629 (1.164-2.28) |

0.019 |

1.157 (0.796-1.682) |

0.7 |

| Disease status: CR62 or more (vs. CR1) |

1.042 (0.617-1.759) |

0.878 |

1.342 (0.717-2.512) |

0.36 |

| HCT-CI7 ≥3 (vs. 0-2) |

1.901 (1.094-3.305) | <0.001 | 2.521 (1.259-5.047) | 0.002 |

| Conditioning Regimen RIC8 (vs. MAC9) |

1.657 (1.11-2.476) |

0.013 |

1.569 (0.946-2.602) |

0.081 |

| Transplantation period After 2020 |

1.176 (0.736-1.877) |

0.498 |

0.629 (0.322-1.228) |

0.231 |

| Grades 2-4 aGVHD10 Time-Dependent Variable |

2.303 (0.557-9.519) |

0.249 |

1.402 (0.175-11.23) |

0.75 |

| Grades 3-4 aGVHD Time-Dependent Variable |

1.858 (1.036-3.333) |

0.037 |

2.327 (1.042-5.199) |

0.039 |

Univariate Cox regression analysis of OS and NRM for the entire cohort.

1OS, Overall Survival; 2NRM, Non-Relapse Mortality; 3HR, Hazard Ratio; 4CI, Confidence Interval; 5ELN, European LeukemiaNet risk classification. 6CR, Complete remission. 7HCT-CI, Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (HCT)-specific Comorbidity Index. 8RIC, Reduced Intensity Conditioning; 9MAC, Myeloablative Conditioning; 10aGVHD, Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease.

Values highlighted in bold indicate a statistically significant p value.

Table 2B

| Multivariate analysis | OS1 HR2 (95% CI3) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age Older than 59 years (vs. younger) |

1.02 (1.04-1.04) |

0.016 |

| Donor Information Older than 29 years (vs. younger) |

1.88 (1.11-3.21) |

0.019 |

| ELN4 Classification III (vs I-II) |

1.60 (1.05-2.45) |

0.029 |

| HCT-CI5 ≥3 (vs. 0-2) |

2.02 (1.35-3.02) |

<0.001 |

| Conditioning Regimen RIC6 (vs. MAC7) |

0.88 (0.54-1.45) |

0.631 |

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of OS for the entire cohort.

1OS, Overall Survival; 2HR, Hazard Ratio; 3CI, Confidence Interval; 4ELN, European LeukemiaNet risk classification. 5HCT-CI, Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (HCT)-specific Comorbidity Index. 6RIC, Reduced Intensity Conditioning; 7MAC, Myeloablative Conditioning.

Values highlighted in bold indicate a statistically significant p value.

Table 2C

| Multivariate analysis | NRM1 HR2 (95% CI3) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age Older than 59 years (vs. younger) |

1.02 (0.99-1.04) |

0.09 |

| Donor Information Older than 29 years (vs. younger) |

2.03 (1.02-4.13) |

0.049 |

| HCT-CI4 ≥3 (vs. 0-2) |

2.06 (1.21-3.49) |

0.007 |

| Conditioning Regimen RIC5 (vs. MAC6) |

0.89 (0.48-1.67) |

0.74 |

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of NRM for the entire cohort.

1NRM, Non-Relapse Mortality; 2HR, Hazard Ratio; 3CI, Confidence Interval; 4HCT-CI,

Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (HCT)-specific Comorbidity Index. 6RIC, Reduced Intensity Conditioning; 6MAC, Myeloablative Conditioning.

Values highlighted in bold indicate a statistically significant p value.

Based on these associations, an optimal donor age cut-off to stratify patients into two risk groups was estimated. Using ROC curve analysis, the optimal donor age cut-off for predicting overall mortality was identified 30 years (AUC = 0.569; 95% CI, 0.502–0.637), and this threshold was used to define the two study cohorts.

Patient and allo-HCT information according to donor-age groups

As described in Table 1, the study cohort was divided into two groups according to donor age showing that 85 (31%) patients received grafts from younger donors, and 189 (69%) from older donors. The median donor age was 24 years (range, 13-30) and 42 years (range, 31-75), respectively. Notably, baseline characteristics and allo-HCT practices were comparable between groups, except for a higher proportion of recipients aged over 65 years in the older donor group (27.5% vs. 11.8%, p = 0.004).

Post-transplant information and disease relapse according to donor age

The main post-transplant information is reported in Table 3. The median time to neutrophil and platelet engraftment was 18 and 24 days, respectively, with no significant differences between patients receiving grafts from younger versus older donors (p = 0.416 and p = 0.948, respectively). Primary or secondary graft failure occurred in 37 (13.9%) patients, with comparable rates between groups (14.5% vs. 13.6%; p = 0.75).

Table 3

| All patients N=274 | Donor age < 30 years N=85 | Donor age ≥ 30 years N=189 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days to neutrophil engraftment, median (IQR) | 18 (15-23) | 18 (16-21) | 18 (15-21) | 0.416 |

| Days to platelet engraftment, median (IQR) | 24 (16-30) | 23 (16-34) | 24 (16-29) | 0.948 |

| Graft failure, total (%) | 37 (13.9) | 12 (14.5) | 25 (13.6) | 0.75 |

| SOS1, total (%) | 11 (4) | 5 (5.9) | 6 (3.2) | 0.326 |

| TA-TMA2, total (%) | 17 (6.3) | 4 (4.8) | 13 (6.9) | 0.596 |

| Infectious Complications During First 180 Days | ||||

| Bacteraemia, total (%) | 122 (44.5) | 43 (50.6) | 79 (42.2) | 0.237 |

| CMV3 reactivation, total (%) | 168 (63.6) | 41 (60.3) | 127 (64.8) | 1 |

| CMV disease, total (%) | 23 (8.7) | 7 (10.3) | 16 (8.2) | 0.523 |

| PTLD4, total (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Cumulative Incidences of GVHD % (95% CI) | ||||

| Day 100 Grades II-IV aGVHD | 15.6 (11.5-20.2) | 3.0 (0.6-9.3) | 19.9 (14.6-25.8) | <0.001 |

| Day 100 Grades III-IV aGVHD | 8.0 (5.1-11.7) | 1.5 (0.1-7.2) | 10.2 (6.5-14.9) | 0.034 |

| 2-Y Mod/Sev cGVHD | 11.5 (7.7-16.0) | 11.7 (5.1-21.3) | 11.4 (7.1-16.7) | 0.49 |

| Relapse, total (%) | 60 (21.9) | 17 (20) | 43 (22.8) | 0.64 |

| Dead, total (%) | 103 (37.6) | 24 (28.2) | 79 (42) | 0.032 |

| Directly secondary to NRM5, total (%) | 57 (20.8) | 11 (12.9) | 46 (24.3) | 0.016 |

| Main Causes of Death (CIBMTR) | ||||

| Relapse | 40 (38.8) | 5 (20.8) | 35 (44.3) | 0.055 |

| Infections | 32 (31.1) | 8 (33.3) | 24 (30.4) | 0.805 |

| GVHD | 10 (9.7) | 1 (4.2) | 9 (11.4) | 0.446 |

| Graft Failure | 4 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 4 (5.1) | 0.571 |

| Multi-organ failure | 2 (1.9) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (1.3) | 1 |

| Others | 15 (14.6) | 9 (37.5) | 6 (7.6) | 0.001 |

| Main Post-Transplant Outcomes [% (95% CI)] | ||||

| 2-y Overall Survival | 68.5 (62.5-73.8) | 80.6 (68.9-88.2) | 64.3 (57.0-70.7) | 0.011 |

| 2-y Relapse-Free Survival | 60.7 (54.4-66.3) | 73.1 (60.7-82.1) | 56.3 (48.9-63.0) | 0.012 |

| 2-y Non-Relapse Mortality | 19.4 (14.9-24.4) | 11.1 (5.4-19.1) | 23.2 (17.3-29.5) | 0.031 |

| 2-y Cumulative Incidence of Relapse | 19.9 (15.2-25.0) | 18.6 (11.0-27.8) | 20.6 (14.9-26.9) | 0.599 |

| 2-y GRFS6 | 0.51 (0.45-0.57) | 0.61 (0.49-0.72) | 0.48 (0.41-0.55) | 0.067 |

Main post-transplant information and outcomes.

1SOS: Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. 2TMA: Thrombotic Microangiopathy. 3CMV: cytomegalovirus. 4PTLD: Post-Transplant Lymphoproliferative Syndrome. 5NRM: Non-Relapse Mortality. 6GRFS: Graft- versus-host disease-free, Relapse-free survival.

Values highlighted in bold indicate a statistically significant p value.

The incidence of veno-occlusive disease and post-transplant thrombotic microangiopathy was 5.9% and 4.8%, respectively, among recipients receiving grafts from younger donors, and 3.2% (p = 0.326) and 6.9% (p = 0.596) among those receiving grafts from older donors. Infectious complications during the first 180 days post-transplant were frequent regardless of donor age, with similar rates of bloodstream infections (50.6% vs. 42.2%; p = 0.237), CMV reactivation (60.3% vs. 64.8%; p = 1), and CMV disease (10.3% vs. 8.2%; p = 0.523) in both groups.

Notably, patients who received grafts from younger donors had a significantly lower incidence of aGVHD, both for grade II–IV (Day +100: 3.0% vs. 19.9%; p < 0.001; Figure 1A) and for severe grade III–IV (Day +100: 1.5% vs. 10.2%; p = 0.034; Figure 1B). However, the incidence of moderate-to-severe cGVHD at two years was similar between groups (11.7% vs. 11.4%; p = 0.49). Donor age—particularly when over 50 years (OR 4.9, p = 0.016)—and female recipient (OR 3.8, p = 0.045) were independently associated with a significantly increased risk of developing GVHD. This association remained statistically significant in the multivariate analysis (Tables 4A, B).

Figure 1

(A). Cumulative incidence of grade II-IV aGVHD according to donor age. (B) Cumulative incidence of grade III-IV aGVHD according to donor age.

Disease relapse occurred in 17 (20.0%) patients transplanted from younger donors and in 43 (22.8%) patients from donors aged 30 years or older. The two-year cumulative incidence of relapse was 18.6% and 20.6%, respectively (p = 0.599).

Table 4A

| Variables | Univariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR1 | Inferior 95% CI2 | Superior 95% CI | p value | |

| Patient age Older than 59 years |

1.03 2.24 |

0.97 0.56 |

1.10 8.98 |

0.320 0.255 |

| Donor age Older than 49 years |

1.05 4.93 |

1.01 1.35 |

1.11 18.0 |

0.048

0.016 |

| RIC3 (vs. MAC4) | 0.61 | 0.17 | 2.15 | 0.446 |

| Female recipient | 3.80 | 1.03 | 14.0 | 0.045 |

| Female donor | 1.22 | 0.33 | 4.53 | 0.761 |

| HCT-CI5 | 2.05 | 0.32 | 13.3 | 0.454 |

Univariate logistic regression analysis to predict acute graft-versus-host disease.

1OR: Odds ratio; 2CI: Confidence Interval; 3RIC: Reduced Intensity Conditioning; 4MAC: Myeloablative Conditioning; 5HCT-CI: Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (HCT)-specific Comorbidity Index.

Values highlighted in bold indicate a statistically significant p value.

Table 4B

| Variables | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | Inferior 95% CI | Superior 95% CI | p value | |

| Donor age Older than 59 years |

4.55 | 1.20 | 17.3 | 0.026 |

| Female recipient | 3.94 | 0.99 | 15.5 | 0.050 |

Multivariate logistic regression analysis to predict acute graft-versus-host disease.

Values highlighted in bold indicate a statistically significant p value.

Donor age and post-transplant outcomes

As shown in Table 3, mortality rate was significantly lower in patients receiving grafts from donors younger than 30 years compared to those in the older donor group (28.2% vs. 42.0%, p = 0.032), as interestingly, main causes of death were attributable to NRM (12.9% vs. 24.3%, p = 0.016). Regarding the causes of death, they were comparable between groups, with infections representing the leading cause in both cohorts (33.3% vs. 30.4%, P = 0.805). Miscellaneous causes (hemorrhage, stroke, arrhythmia, respiratory failure, thrombotic microangiopathy and sinusoidal obstruction syndrome) accounted for 37.5% of deaths in the younger donor group, while GVHD represented 11.4% of deaths in the older donor group.

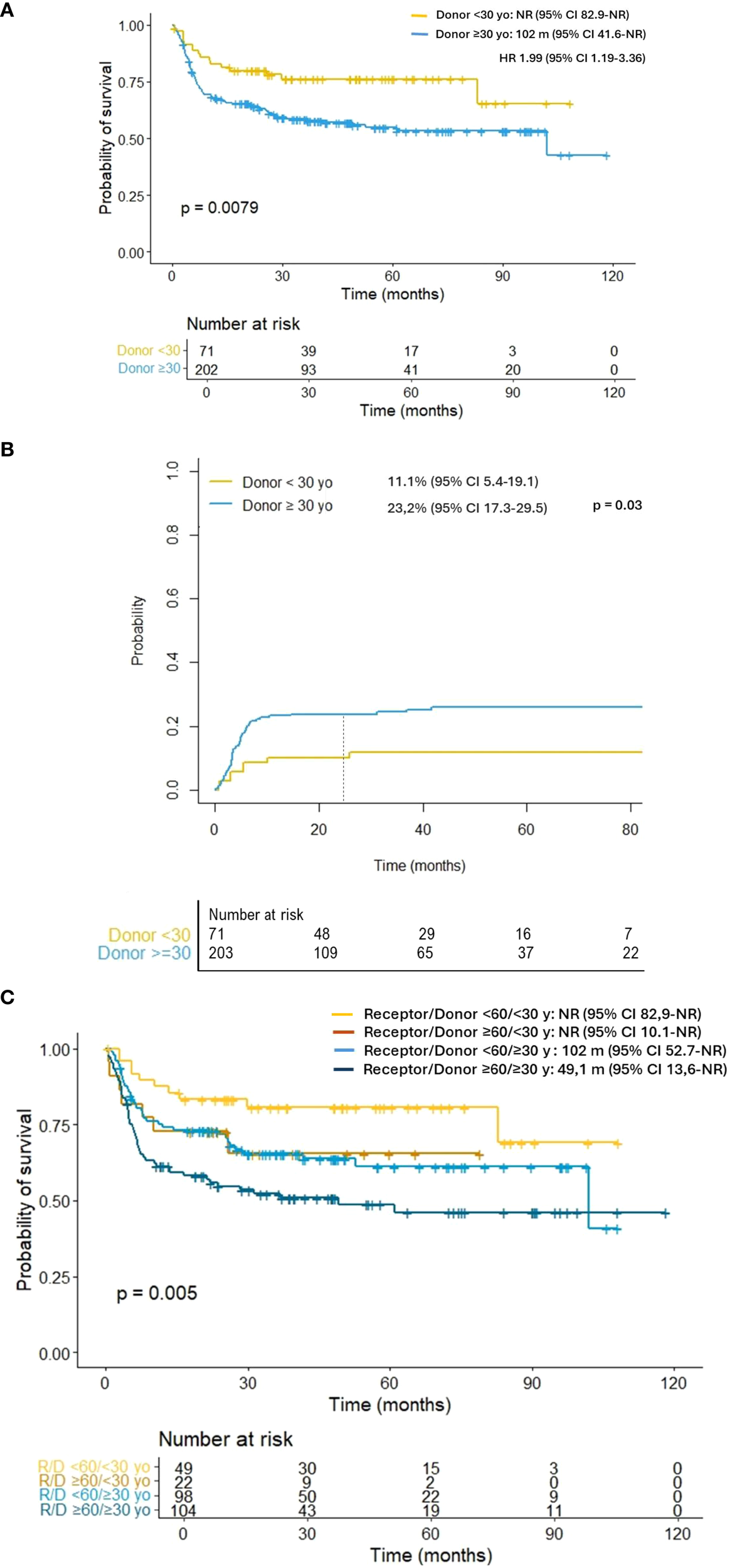

As illustrated in Figure 2A, patients receiving grafts from younger donors had higher OS (2- year: 80.6% vs. 64.3%, p = 0.011) and lower NRM (11.1% vs. 23.2%, p = 0.031; Figure 2B) than those included in the older donor cohort. Regarding patient age, individuals over 60 years who received a transplant from a younger donor demonstrated OS comparable to that of patients under 60 years who received grafts from older donors (102 months vs NR; p = 0.889; Figure 2C). In addition, younger donor cohort exhibited a significantly higher RFS (2-year: 73.1% vs. 56.3%, p = 0.012) due to the reduced rates of NRM observed in this group of patients.

Figure 2

(A) Overall survival according to donor age. (B) Non-relapse mortality according to donor age. (C) Overall survival according to donor and receptor age. Individuals over 60 years who received a transplant from a younger donor demonstrated overall survival comparable to that of patients under 60 years who received grafts from older donors (101 months vs NR; p = 0.889).

Donor age as an independent predictive factor for survival

As shown in Table 2A, the UVA indicated that patients undergoing haplo-HCT from donors aged ≥30 years had significantly worse OS (HR: 1.63; 95% CI: 1.02–2.61; p = 0.009) and higher NRM risk (HR: 2.05; 95% CI: 1.07–3.94; p = 0.03). Based on these findings, a MVA was performed, including the variables found to be significant in the UVA and other considered clinically relevant. As shown in Table 2B, the MVA confirmed that grafts from older donors were associated with worse OS (HR: 1.88; 95% CI: 1.10–3.20; p = 0.019) and higher NRM (HR: 2.06; 95% CI: 1.01–4.13; p = 0.049) (Table 2C).

Additionally, the MVA for OS revealed that patients older than 59 years (HR 1.02, p = 0.016), those with high-risk AML (HR: 1.60; p = 0.029), and those with an HCT-CI score >3 (HR: 2.01; p < 0.001) had an increased risk of mortality. For NRM, a higher comorbidity burden (HCT-CI >3; HR: 2.06; p = 0.007) and age over 59 years (HR: 1.02; p = 0.09) were also identified as additional risk factors.

Discussion

Haplo-HCT with PTCY-based prophylaxis represents a safe and effective strategy that has expanded access to transplantation for patients without a suitable HLA-matched donor. However, optimal criteria for donor selection remain under investigation. In this multicenter, retrospective analysis, we evaluated 274 patients who underwent haplo-HCT. Our findings indicate that donor age is an independent and significant factor, with younger donor age than 30 years associated with improved OS, reduced NRM and a lower incidence of clinically relevant aGVHD.

Donor age has emerged one of the main factors investigated in the search for optimal donor characteristics to improve allo-HCT outcomes in the recent years. Previous evidence conducted in HLA-matched allo-HCT settings has demonstrated the significant role of younger donor age in outcomes (5). However, older sibling donors are generally linked to older patients limiting the evaluation of the independent effects of both variables on transplant results. Notably, recent studies in the context of MUD allo-HCT have further demonstrated that selecting younger donors increases the likelihood of transplantation success. Specifically, younger donor age has been associated with lower incidences of GVHD, improved immune reconstitution, and superior overall survival, thereby underscoring the critical impact of donor age on transplantation outcomes (4, 6, 7).

Over the past 15 years, the indication of haplo-HCT has steadily increased and currently represents approximately 20% of all allogeneic HCTs performed in Europe (8, 9). This expansion is largely attributable to the adoption of PTCy-based prophylaxis, which has revolutionized the field of allo-HCT due to its immunomodulatory effects for GVHD prevention and favorable safety profile (10). Consistently, many patients who previously lacked a suitable HLA-matched donor are now able to safely undergo haplo-HCT. In addition, among haploidentical donors, the degree of relatedness can vary—typically including children, siblings, and parents—leading to a wide range of donor ages within this group, justifying the importance of refining donor selection criteria in the haplo-HCT setting and determining the role of donor age in haplo-HCT outcomes. In AML, where relapse risk remains a major barrier to cure, the more widespread use of PTCy platforms not only increases donor availability but also shifts the focus toward donor optimization. Recent large-scale analyses in the PTCy era, reported by Sanz J. et al. and Ye Y. et al. (11, 12), indicate that donor-related factors such as age and relationship now emerge as independent predictors of outcome, suggesting that donor selection—beyond mere donor availability—is increasingly relevant for AML patients undergoing haplo-HCT.

According to our results, the infusion of peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) products from haploidentical donors younger than 30 years was associated with higher OS, lower NRM and comparable relapse rates. These results are particularly relevant in haplo-HCT settings, where potential donors often span a wide age range, including siblings, parents, children, and other relatives. As illustrated in Figure 2C, older patients (≥60 years) who received grafts from donors under 30 years exhibited survival outcomes comparable to younger recipients transplanted from older donors (101 months vs. not reached; p = 0.889). This 30-year cut-off should be interpreted with caution due to the limited statistical power, and further research is needed to refine the optimal threshold. Nevertheless, it provides a clinically applicable criterion for donor selection.

Our results are consistent with previous data reported by DeZern et al. (13), further supporting the favorable impact of selecting younger donors in the haplo-HCT setting performed with non-myeloablative conditioning regimens, and support transplant practices at different institutions were a youngest adult-sized haploidentical donor is selected if feasible and medically appropriate. Moreover, conclusions are particularly relevant for AML patients, a disease frequently affecting elderly patients who often have older siblings as potential donors (14).

Notably, our results also demonstrate that patients receiving grafts from younger donors exhibited a significantly lower incidence of aGVHD, both grade II–IV and grade III–IV (3.0% vs. 19.9%, p < 0.001; and 1.5% vs. 10.2%, p = 0.034, respectively). In contrast, no significant differences were observed in the incidence of cGVHD (11.7% vs. 11.4%; p = 0.49). These findings are clinically relevant, given that GVHD remains a major source of morbidity and mortality following allo-HCT, and its prevention is a central therapeutic objective, particularly in the haploidentical setting. In addition, observations are consistent with prior reports (7, 13), where younger donor age has been associated with lower aGVHD rates and improved immune reconstitution. It is hypothesized that younger donors provide a higher proportion of functional, naïve T cells with distinct cytokine profiles, contributing to reduced alloreactivity and GVHD risk.

In contrast to the significant differences in aGVHD, our study found no differences in the relapse incidence between younger and older donor cohorts (18.6% vs. 20.6%, p = 0.599). This finding is consistent with previous studies suggesting that donor age exerts limited impact on graft-versus-leukemia effects (7, 13). Thus, the survival benefit observed with younger donors appears to be primarily driven by reduced NRM, rather than differences in disease control. Overall, these results reinforce the notion that relapse risk is determined by a complex interplay of factors beyond donor age, including leukemia biology, conditioning regimen intensity, and post-transplant immunosuppressive strategies (15). In this context, selecting younger donors may help minimize transplant-related complications without compromising anti-leukemic efficacy.

Grafts obtained from younger donors may possess more favorable biological characteristics compared to those from older donors. Aged HSCs exhibit impaired self-renewal and long-term reconstitution potential (16). Moreover, clonal hematopoiesis increases with age, with a prevalence of approximately 1% in healthy individuals under 40 years and up to 20% in those over 65 and has been associated with shorter OS and a higher risk of relapse (17). HCT from younger donors are associated with improved immune reconstitution, based on faster kinetics of CD4+ T cell, CD8+ T cell, B cell and NK cell development (18). Age-related differences in lymphoid cell populations may also influence haplo-HCT outcomes. In this context, the presence of innate lymphoid cells in allogeneic grafts has been reported to reduce the incidence of GVHD (19), potentially reflecting impaired alloreactivity in grafts from older donors. Nevertheless, the underlying causes of the improved outcomes observed with younger donors have not yet been well characterized. In this regard, further research is needed to clarify the interplay between biological and clinical factors that may explain the findings observed in the present study.

Our study has several limitations. The retrospective design inherently carries a risk of selection and reporting biases, and the restriction to centers within a single country and a specific disease may limit the generalizability of our findings to broader or more diverse populations. In addition, the present analysis focuses its investigation on donor age and does not include information about donor/recipient CMV serostatus or ABO compatibility. Although the results are of interest, caution is needed in their interpretation, as other relevant donor-related variables were not included in this study. To further address this limitation, future analyses will be conducted to explore their potential impact on transplant outcomes. In the present study, CMV serostatus was not included at the time of data collection since part of the patients transplanted after 2021 received letermovir prophylaxis. Moreover, the impact of ABO compatibility on haplo-HCT outcomes has already been investigated in previous reports, supporting the consideration of this variable as well when selecting haploidentical donors for transplantation (20).

In summary, our findings confirm that donor age is an independent determinant of outcomes in haplo-HCT, with younger donors associated with improved OS, reduced NRM, and lower incidence of aGVHD. This effect remains significant regardless of recipient age and appears unrelated to relapse risk. The results underscore the importance of donor age as a key consideration in donor selection in AML patients. Biological factors such as clonal hematopoiesis and immune cell composition may underline these associations.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Comité de Ética de la Investigación con medicamentos. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because deceased patients cannot sign an informed consent.

Author contributions

DM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. EP-L: Writing – review & editing. CM: Writing – review & editing. ML: Writing – review & editing. AE: Writing – review & editing. CMC: Writing – review & editing. CA: Writing – review & editing. FP-M: Writing – review & editing. IH: Writing – review & editing. IO: Writing – review & editing. AS: Writing – review & editing. SF-L: Writing – review & editing. JD-G: Writing – review & editing. SV: Writing – review & editing. JL-L: Writing – review & editing. CAF: Writing – review & editing. AG-R: Writing – review & editing. LG: Writing – review & editing. TT: Writing – review & editing. SF: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. PB: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. MP: Writing – review & editing. MR: Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank our patients and the nursing and support staff in the Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Programs participating in the study and the support provided by the GETH-TC. We additionally thank REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) service for permitting the use of their service without costs. REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Magee G Ragon BK . Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. (2023) 36:101466. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2023.101466

2

Arcuri LJ Aguiar MTM Ribeiro AAF Pacheco AGF . Haploidentical transplantation with post-transplant cyclophosphamide versus unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transpl. (2019) 25:2422–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.07.028

3

Solomon SR Aubrey MT Zhang X Piluso A Freed BM Brown S et al . Selecting the best donor for haploidentical transplant: impact of HLA, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor genotyping, and other clinical variables. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transpl. (2018) 24:789–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.01.013

4

Abid MB Estrada-Merly N Zhang MJ Chen K Allan D Bredeson C et al . Impact of donor age on allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation outcomes in older adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Transplant Cell Ther. (2023) 29:578.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2023.06.020

5

Kollman C Howe CWS Anasetti C Antin JH Davies SM Filipovich AH et al . Donor characteristics as risk factors in recipients after transplantation of bone marrow from unrelated donors: the effect of donor age. Blood. (2001) 98:2043–51. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.7.2043

6

Piemontese S Labopin M Choi G Broers AEC Peccatori J Meijer E et al . Older MRD vs. younger MUD in patients older than 50 years with AML in remission using post-transplant cyclophosphamide. Leukemia. (2024) 38:2016–22. doi: 10.1038/s41375-024-02359-8

7

Kim HT Ho VT Nikiforow S Cutler C Koreth J Shapiro RM et al . Comparison of older related versus younger unrelated donors for older recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome: A large single-center analysis. Transplant Cell Ther Off Publ Am Soc Transplant Cell Ther. (2024) 30:687.e1–687.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2024.05.001

8

Passweg JR Baldomero H Bader P Bonini C Duarte RF Dufour C et al . Use of haploidentical stem cell transplantation continues to increase: the 2015 European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplant activity survey report. Bone Marrow Transpl. (2017) 52:811–7. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2017.34

9

Passweg JR Baldomero H Atlija M Kleovoulou I Witaszek A Alexander T et al . The 2023 EBMT report on hematopoietic cell transplantation and cellular therapies. Increased use of allogeneic HCT for myeloid Malignancies and of CAR-T at the expense of autologous HCT. Bone Marrow Transpl. (2025) 60:519–28. doi: 10.1038/s41409-025-02524-2

10

Kachur E Patel JN Morse AL Moore DC Arnall JR . Post-transplant cyclophosphamide for the prevention of graft-vs.-host disease in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: A guide to management for the advanced practitioner. J Adv Pract Oncol. (2023) 14:520–32. doi: 10.6004/jadpro.2023.14.6.5

11

Sanz J Labopin M Choi G Kulagin A Peccatori J Vydra J et al . Younger unrelated donors may be preferable over HLA match in the PTCy era: a study from the ALWP of the EBMT. Blood. (2024) 143:2534–43. doi: 10.1182/blood.2023023697

12

Ye Y Berland ATF Labopin M Chen J Wu D Blaise D et al . Better outcome following younger haploidentical donor versus older matched unrelated donor transplant for fit patients with acute myeloid leukemia transplanted in first remission: A study from the global committee and the acute leukemia working party of the EBMT. Am J Hematol. (2025) 100:1252–5. doi: 10.1002/ajh.27681

13

DeZern AE Franklin C Tsai HL Imus PH Cooke KR Varadhan R et al . Relationship of donor age and relationship to outcomes of haploidentical transplantation with posttransplant cyclophosphamide. Blood Adv. (2021) 5:1360–8. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003922

14

Pulsipher MA Logan BR Chitphakdithai P Kiefer DM Riches ML Rizzo JD et al . Effect of aging and predonation comorbidities on the related peripheral blood stem cell donor experience: report from the related donor safety study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transpl. (2019) 25:699–711. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.11.004

15

Ossenkoppele GJ Janssen JJWM van de Loosdrecht AA . Risk factors for relapse after allogeneic transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. (2016) 101:20–5. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.139105

16

De Haan G Lazare SS . Aging of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. (2018) 131:479–87. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-06-746412

17

Gillis N Ebied A Thompson ZJ Pidala JA . Clinical impact of clonal hematopoiesis in hematopoietic cell transplantation: a review, meta-analysis, and call to action. Haematologica. (2024) 109:3952–64. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2024.285392

18

Lin RJ Elias HK van den Brink MRM . Immune reconstitution in the aging host: opportunities for mechanism-based therapy in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:674093. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.674093

19

Kroeze A. van Hoeven V. Verheij M. W. Turksma A. W. Weterings N. van Gassen S. et al . Presence of innate lymphoid cells in allogeneic hematopoietic grafts correlates with reduced graft-versus-host disease. Cytotherapy. (2022) 24:302–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2021.10.011

20

Güven M Peczynski C Boreland W Blaise D Peffault de Latour R Yakoub-Agha I et al . The impact of ABO compatibility on allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation outcomes: a contemporary and comprehensive study from the transplant complications working party of the EBMT. Bone Marrow Transpl. (2025) 60:956–63. doi: 10.1038/s41409-025-02580-8

Summary

Keywords

donor age, allo-HCT, haplo-HCT, PTCY, AML

Citation

Munárriz D, Pérez-López E, Martín Rodríguez C, Luque M, Esquirol A, Calvo CM, Aparicio C, Peña-Muñóz F, Heras Fernando I, Oiartzabal Ormtegi I, Sáez Marín AJ, Fernández-Luis S, Domínguez-García JJ, Villar Fernández S, López-Lorenzo JL, Acosta Fleitas C, González-Rodriguez AP, García L, Torrado T, Filaferro S, Balsalobre P, Pascual Cascon MJ, Rovira M and Queralt Salas M (2025) Donor age as an independent predictor of inferior outcomes after haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia. Study conducted on behalf of GETH-TC. Front. Immunol. 16:1700463. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1700463

Received

06 September 2025

Revised

10 November 2025

Accepted

12 November 2025

Published

28 November 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Emmanuel Katsanis, University of Arizona, United States

Reviewed by

Xiao-Hua Luo, First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, China

Remy Dulery, Hôpital Saint-Antoine, France

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Munárriz, Pérez-López, Martín Rodríguez, Luque, Esquirol, Calvo, Aparicio, Peña-Muñóz, Heras Fernando, Oiartzabal Ormtegi, Sáez Marín, Fernández-Luis, Domínguez-García, Villar Fernández, López-Lorenzo, Acosta Fleitas, González-Rodriguez, García, Torrado, Filaferro, Balsalobre, Pascual Cascon, Rovira and Queralt Salas.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: María Queralt Salas, queralt.salas87@outlook.es; mqsalas@clinic.cat

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.