Abstract

Mosquitoes rely exclusively on blood-derived sterols, transported by sterol carrier protein (SCP), for reproduction and metabolic regulation. SCP expression is strongly induced after blood feeding and dynamically modulated during Plasmodium vivax infection—upregulated in the midgut and salivary glands but suppressed in hemocytes—indicating that parasite infection modulates the host sterol transport and metabolism. RNAi-mediated knockdown of SCP significantly reduced mosquito fecundity, underscoring its vital role in reproductive physiology. These findings highlight SCP as a key metabolic regulator linking nutrient uptake to reproductive outcome, while its Plasmodium infection-driven modulation may facilitate the parasite growth. While reproduction remains the primary physiological outcome, the metabolic modulation of SCP during infection also points to it as a possible transmission-blocking target in integrated malaria control strategies.

Introduction

Mosquitoes transmit numerous arboviral and parasitic diseases, including malaria, dengue, chikungunya, and Zika. Malaria is caused by Plasmodium species and transmitted by Anopheles mosquito species, and it remains a major global health and economic concern (1). Even though Plasmodium falciparum is the major cause of global morbidity, Plasmodium vivax is also a rapidly emerging problem in Southeast Asian regions. In India, highly endemic areas are facing an increased burden of both species, and thus, in parallel, there is an urgent need to focus on P. vivax (2). Blood feeding by adult female mosquitoes is vital for their egg development and gonotrophic cycle maintenance (3, 4). Following the ingestion of protein-rich blood meal, the gut metabolic machinery activates to digest the blood meal; to facilitate the conversion of blood to a nutritional supplement, the nutrients are supplied to the ovary for egg development via the fat body.

Cholesterol is a crucial biomolecule for maintaining the structural integrity of cell membranes, cell signaling, and larval metamorphosis. Kim et al. and Perera and Wijerathna demonstrated that an inhibitor targeting sterol carrier protein has shown larvicidal activity, highlighting the essential role of sterol carrier protein (SCP) in mosquito aquatic development, serving as a good candidate for a metabolic target for vector control (5, 6).

Moreover, it is the precursor for the ecdysone hormone responsible for vitellogenesis in adult female mosquitoes (7, 8). In vertebrates, SCP-2 is characterized as a lipid carrier protein, having a sterol binding domain (SCP-2, SCP-x, SCP-like-2, SCP-like-3, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type IV, and stomatin) that binds with sterols, fatty acids, fatty acid acyl-CoA, and phospholipids (9). Although the molecular mechanisms and fundamental nature of SCP-2’s ligand selectivity are ambiguous, it may mediate cholesterol trafficking, metabolism, and fatty acid uptake and trafficking (5, 10). Mosquitoes lack enzyme squalene monooxygenase and lanosterol synthase, which help in cholesterol de novo synthesis; hence, mosquitoes take a blood meal for cholesterol (6). Due to the hydrophobic nature of cholesterol, it cannot traverse the intracellular environment; thus, it needs SCPs to facilitate its transfer through the membrane (11). As cholesterol crosses the membrane, lipophorin assists its transport in hemolymph to the fat body and ovary for storage and egg development, respectively.

Although previous studies have demonstrated that the inhibition of SCP disrupts cholesterol uptake and results in larval mortality, the physiological role of SCP in adult mosquitoes remains poorly understood. Limited evidence suggests that P. falciparum and Plasmodium berghei infections can alter mosquito anti-parasitic immune responses; however, the potential involvement of SCP in maintaining nutritional homeostasis and cholesterol utilization during infection is yet to be elucidated (12). In the case of P. vivax, such investigations have been particularly constrained by the absence of a reliable and reproducible long-term in vitro culture system, which hampers mechanistic studies of parasite–vector interactions. Our recent comparative gut-RNA-Seq data analysis highlighted that P. vivax infection induces several unique transcripts that encode proteins such as trehalase, folliculin, and sterol carrier (13). These proteins may have a potential role in the management of nutritional homeostasis. A functional knockdown of trehalase enzyme transcripts led to a significant loss of egg development. However, P. vivax infection causes an increased expression of these transcripts in the gut and salivary glands of the Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes (14). Here, we aimed to evaluate the spatial–temporal expression of SCP in response to i) blood meal digestion, along with cholesterol absorption and its distribution in various tissues, and ii) P. vivax infection in the midgut, hemocyte, and salivary glands. We also aimed to evaluate the possible role in the reproductive physiology of the adult female An. stephensi mosquitoes. Here, we demonstrate that sterol carrier protein transcript (AsSCP) upregulates after a few hours in response to blood feeding in uninfected mosquitoes, while P. vivax infection boosts sterol carrier protein transcription in the gut and salivary glands. Our data suggest that blood meal-induced modulation of SCP favors optimal maturation of ovarian development. However, P. vivax infection may alter the nutritional stress response and influence anti-Plasmodium immunity in the mosquito. A significant reduction in the eggs laid by AsSCP-silenced gravid females correlates with its possible role in mosquito reproductive physiology.

Materials and methods

Mosquito collection, rearing, and maintenance

An. stephensi mosquitoes, an Indian strain, were taken from an established colony perpetuated in the insectary at ICMR-National Institute of Malaria Research and maintained under conditions of 28°C ± 2°C, ~80% relative humidity, and a photoperiod of 12:12 hr. Throughout the project, adult mosquitoes were regularly supplemented with sterile sugar solution (10%) using a cotton swab (15), while for maintenance initiation of gonotrophic cycles, 3–4-day-old mosquitoes were allowed to feed on a rabbit obtained from an institutional animal house facility. After 72 hrs of blood feeding, adult female mosquitoes were allowed to lay eggs on moistened filter paper pasted along the wall of a small plastic cup, one-third of which was filled with pre-cooled boiled water. Then, hatched larvae were transferred to enamel trays containing water and supplemented with mixed dried powder of fish food and dog biscuit in a ratio of 4:6 as larval feed. At a regular interval of 24 hrs, waste was removed, and a fresh nutrient supply to the larvae was provided. Following completion of larval stages (L1–L4), the mature pupae were manually collected in a water-containing plastic cup and kept inside a 30 × 30 × 30 cm3 muslin cloth cage for adult emergence. Post-emergence, the adult mosquitoes fed on soaked raisins and sterile water swabs. All the procedures for the rearing and maintenance of mosquito culture protocols were approved by the Institute Animal Ethics Committee (NIMR/IAEC/2017-1/07).

Mosquito tissue sample collection

As per the technical design of the experiments under distinct physiological conditions, 3–4-day-old, naïve, sugar-fed, adult female An. stephensi mosquitoes were cold (4°C)-anesthetized for 5 min and immobilized in a drop of ice-cold Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) on microscopic slides. The desired tissues, such as midgut, salivary glands, hemolymph, fat body, and ovary, were dissected under a microscope and directly collected in a sterile 1.5-mL Eppendorf tube containing ~100 μL TRIzol as described earlier (16). Likewise, the developmental stages of the An. stephensi mosquitoes were monitored; egg, larvae (stages I–IV), and pupae were also collected in TRIzol reagent after removal of excess water using filter paper, and all the collected samples were stored at −20°C until RNA extraction. For hemolymph collection, approximately 2–3 μL of anticoagulant consisting of 60% Schneider’s medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 30% citrate buffer was injected into the thorax. The mosquitoes’ belly bulged out, and a small incision was made in the abdomen using a microscopic needle so that transparent hemolymph oozed out. Hemolymph was collected using a micropipette and pooled in TRIzol. The fat body was collected by pulling all the abdominal tissues from the last two abdominal segments, and afterward, force tapping of the abdominal carcass was conducted so that the fat body (pale yellow in color) oozed out (16).

Infectivity assay

The blood sample was collected from the P. vivax-infected patients with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Malaria Research (NIMR), Delhi (ECR/NIMR/EC/2012/41). Written informed consent (IC) was obtained from donors visiting the NIMR clinic, and 0.5 to 2 mL of venous blood was drawn into heparin-containing tubes and kept at 37°C until feeding. For mosquito infection, overnight-starved, 4–5-day-old female An. stephensi mosquitoes were fed using a pre-optimized artificial membrane feeding assay (AMFA). The control mosquito group, originating from the same cohort, was offered uninfected blood obtained from a volunteer donor. After successful blood feeding, the unfed and partially fed mosquitoes were carefully removed, while fully fed mosquitoes were maintained under optimal insectarium conditions. The positive infection was confirmed via standard mercurochrome staining of the gut oocysts readily observed under a compound microscope, and the desired tissue samples, such as midgut, salivary glands, and hemocytes, were collected from 20–25 mosquitoes for subsequent analysis as described earlier (17).

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the midgut, salivary glands, and other tissues following the standard manufacturer’s protocol involving phenol-chloroform extraction. The isolated total RNA was quantified by NanoDrop (ND-2000; Thermo Fisher, USA, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), and each RNA sample was treated with RNase-free DNase I to exclude any genomic DNA contamination. One microgram of total RNA was utilized for the synthesis of first-strand cDNA using a mixture of oligo-dT and random hexamer primers, and PrimeScript II reverse transcriptase as per the described protocol (Verso cDNA synthesis Kit, Cat#AB-1453/A, EU, Lithuania) (15, 18).

Routine RT-PCR was performed using SCP-2 primer sequences Fw: AGTTGAAGGTGGAGAAAGGT and Rev: TGATTTACTGACGTACTGCG and housekeeping gene Actin primer sequences Fw: TGCGTGACATCAAGGAGAAG and Rev: GATTCCATACCCAGGAACGA and validated via agarose gel electrophoresis, while relative gene expression analysis was performed using Real-Time PCR. Approximately 25 ng of cDNA was used in 10-μL real-time PCR reactions. The relative abundance of the gene of interest was assessed using the SYBR Green qPCR master mix (Thermo Scientific) and the Bio-Rad CFX96 PCR machine. PCR cycle parameters involved an initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 min, and 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C, 15 s at 52°C, and 22 s at 72°C. After the final extension step, the melting curve was derived and examined for quality control. Each experiment was performed in three independent biological replicates.

Gene knockdown RNAi assays in adult mosquitoes

To knock down SCP expression, dsRNA primers carrying a T7 overhang were synthesized as listed in the Supplementary Table (ST1). The amplified PCR product was examined via agarose gel electrophoresis, purified (Thermo Scientific Gene JET PCR Purification Kit #K0701), quantified, and subjected to double-stranded RNA synthesis using Transcript Aid T7 high-yield transcription kit (Cat# K044, Ambion, USA, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), and the dsrLacZ gene was used as a control. Approximately 69 nL (3 μg/μL) of purified dsRNA product was injected into the thorax of a cold-anesthetized, 1–2-day-old female mosquito using a nano-injector (Drummond Scientific, CA, USA, Broomall, Pennsylvania, United States), as described earlier (14, 16). The knockdown of the respective gene was confirmed via quantitative RT-PCR after 3–4 days of dsRNA injection.

Oviposition assay

Overnight, 50 mated female (either control or SCP knockdown) mosquitoes were blood-fed on a rabbit. After blood feeding, partially/incompletely blood-fed females were removed; fully engorged females were kept in a cage for 48 hrs and then individually placed in netted plastic cups containing half-filled water and paper fixed on the wall of cups, which provided a moisture surface to lay eggs. After 24 hrs, the total number of eggs laid on the blotting paper was manually counted and compared between the two mosquito groups. The number of eggs laid was recorded in three independent experiments.

Statistical analysis

The relative quantification data of the gene expression were normalized with an internal control (Actin) and analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method in the Origin8.1 software. Initially, relative expression was evaluated as a general response using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) through multiple comparisons. However, wherever required, “test” sample data were compared with “control” data set and statistically analyzed using Student’s t-test. All the data were expressed as mean ± SD, and the results were significant if the p-value was less than 0.05. Each experiment was performed at least three times to validate the findings. Egg-laying statistical analysis using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, with p < 0.05, confirmed the statistical significance of the reduction.

Gene phylogeny analysis

Standard BLAST homology search analysis was performed to retrieve the corresponding homolog sequences from the vector base. Phylogenetic trees were prepared with selected SCP amino acid sequences using the maximum likelihood (ML) method in the MEGA X program.

All our selected SCP sequences were aligned using the ClustalW algorithm, where the reliability of the branching was tested using a bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates. The processed phylogenetic tree was examined based on clusters and nodes formed.

Result and discussion

Identification and molecular characterization of AsSCP

To unravel the tissue-specific molecular complexity of mosquito–parasite interaction, currently, we are annotating a large-scale RNA-Seq database generated from naïve control versus P. vivax-infected mosquitoes (13). Plasmodium invades different tissues such as the midgut, hemolymph, and salivary glands. These tissues are subjected to various immune responses and altered metabolic conditions. The successful development of Plasmodium heavily depends upon the host’s nutrient resources. Parasites sense the host environment and respond quickly to metabolic fluctuations to survive within their host. Thus, identification of the host factors implicated in the host–parasite interaction is crucial in comprehending the growth and development of the parasite within the vector and uncovering novel approaches to intervene in Plasmodium development. While studying how Plasmodium development within the vector modulates the nutritional homeostasis of the host to favor its development, we observed an increased read count of a transcript encoding sterol carrier homolog protein (which facilitates the intracellular transport of cholesterol/lipid) in P. vivax-infected mosquitoes (13).

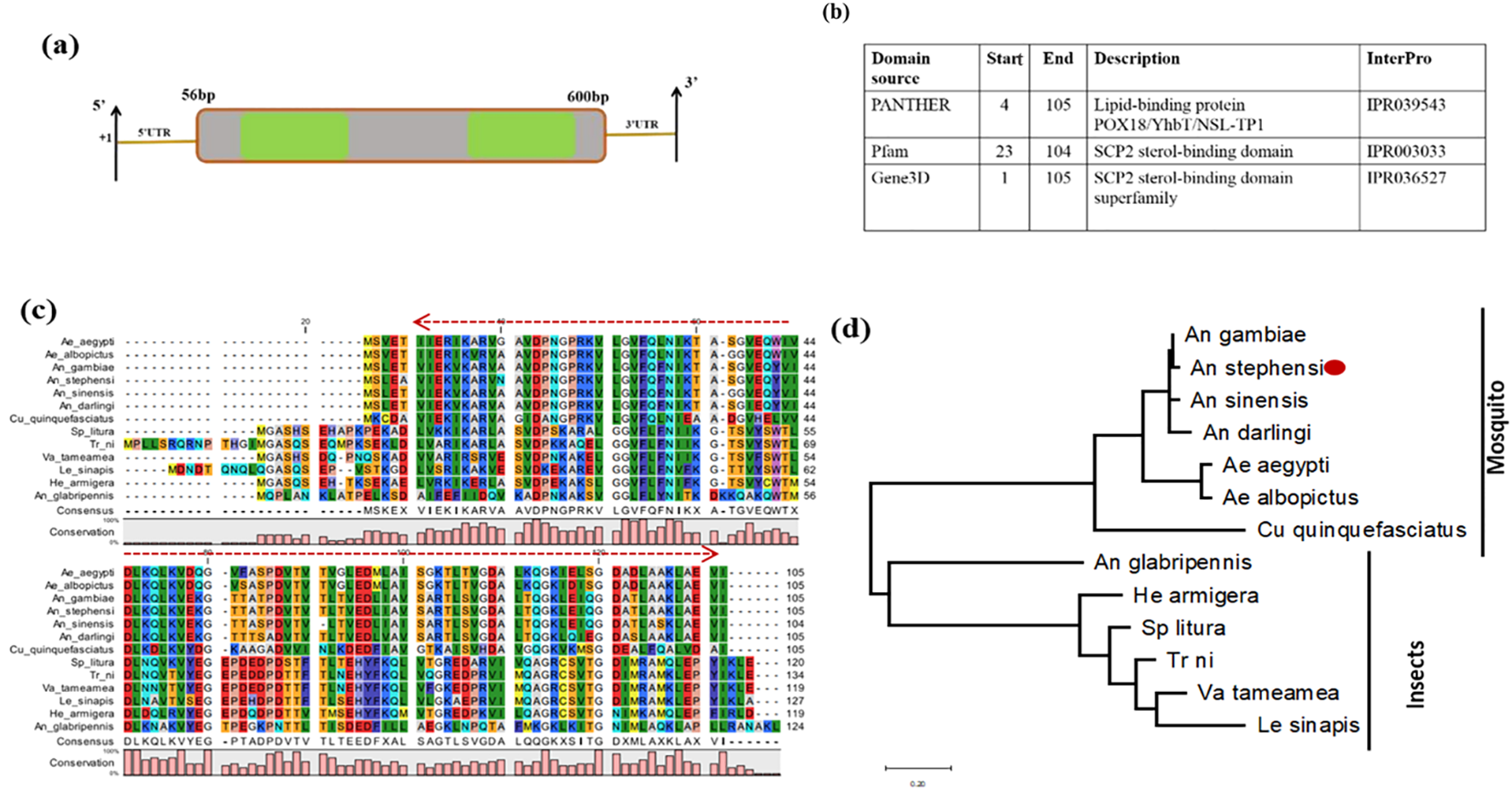

Like other insects, mosquitoes cannot synthesize de novo cholesterol and must acquire it from a blood meal. We further characterized and evaluated the SCP expression in the mosquito to examine its possible physiological role in the mosquito. An in silico analysis revealed that AsSCP (ASTEI04293-PA) is a 655-bp-long transcript, encoding 105 amino acids, and has a high degree of conservation among the insects and blood-feeding mosquito species (Figures 1a–d). AsSCP comprises two exons followed by 3′ and 5′ UTR regions, but the putative conserved domain is still obscure. However, a comprehensive search of the mosquito-specific genomic database suggested that AsSCP may carry a poorly characterized “lipid-binding protein POX18/YhbT/NSL-TP1” domain. Non-specific lipid-transfer protein-like 1 (NSL-TP1 or nlt-1) from Caenorhabditis elegans is found in the peroxisome (19), while protein YhbT from Escherichia coli is cytosolic. POX18 from the yeast Candida tropicalis is involved in beta-oxidation of long-chain fatty acids and non-specific lipid-transfer activity, despite lacking the catalytic cysteine conserved in SCP2.

Figure 1

Genomic organization and molecular characterization of AsSCP. (a) Schematic representation of the genomic architecture of SCP. Two green-colored boxes (E1 and E2) represent exons, and +1 indicates the transcription initiation site. A 50-bp UTR region is present on both 5′ and 3′ ends of the transcript. (b) SCP predicts domain description. (c) Multiple sequence alignment of mosquitoes and other insect-encoded SCP homolog protein showing strong conservation among anopheline mosquitoes; red arrow highlights the conserved lipid-binding domain. (d) Phylogenetic relationship of AsSCP proteins within the insect taxa species: non-blood-feeding insects included Anoplophora glabripennis, Spodoptera litura, Helicoverpa armigera, Vanessa tameamea, Trichoplusia ni, and Leptidea sinapis, while blood-feeding insects included mosquito species of Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus, Culex quinquefasciatus, Anopheles darlingi, Anopheles sinensis, Anopheles gambiae, and Anopheles stephensi. The evolutionary history was built using the maximum likelihood method and Jones-Taylor (JT) matrix-based model involving 13 amino acid sequences. The heuristic search was obtained by applying neighbor-joining and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated, followed by topology selection with the superior log-likelihood value. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. SCP, sterol carrier protein.

Developmental expression pattern of AsSCP in An. stephensi

Although we observed a high expression of AsSCP in the pupal stage, after emergence, the adult male mosquitoes exhibited higher expression compared to the adult female mosquitoes (Supplementary Figure 1). The transformation from pupa to adult is brought about by ecdysteroid and a decline in the level of juvenile hormone (JH) during the pupal stage (20). Together, these data indicate that the active pupal stage may serve as a reserve source of cholesterol mobilization for the synthesis of ecdysone during the final molting of pupa to adult mosquitoes. Although the exact mechanism is yet to be elucidated, the knockdown of SlSCPx transcripts in the Spodoptera litura larvae adversely affected the transition from the larval to pupal stage (21).

The altered cholesterol accumulation in response to SlSCPx knockdown suggests that AsSCP may have a similar effect. Likewise, SCP inhibitors suppressed cholesterol uptake in Aedes aegypti fourth instars and showed larvicidal activities (22).

Tissue-specific and blood meal-induced expression of AsSCP in An. stephensi

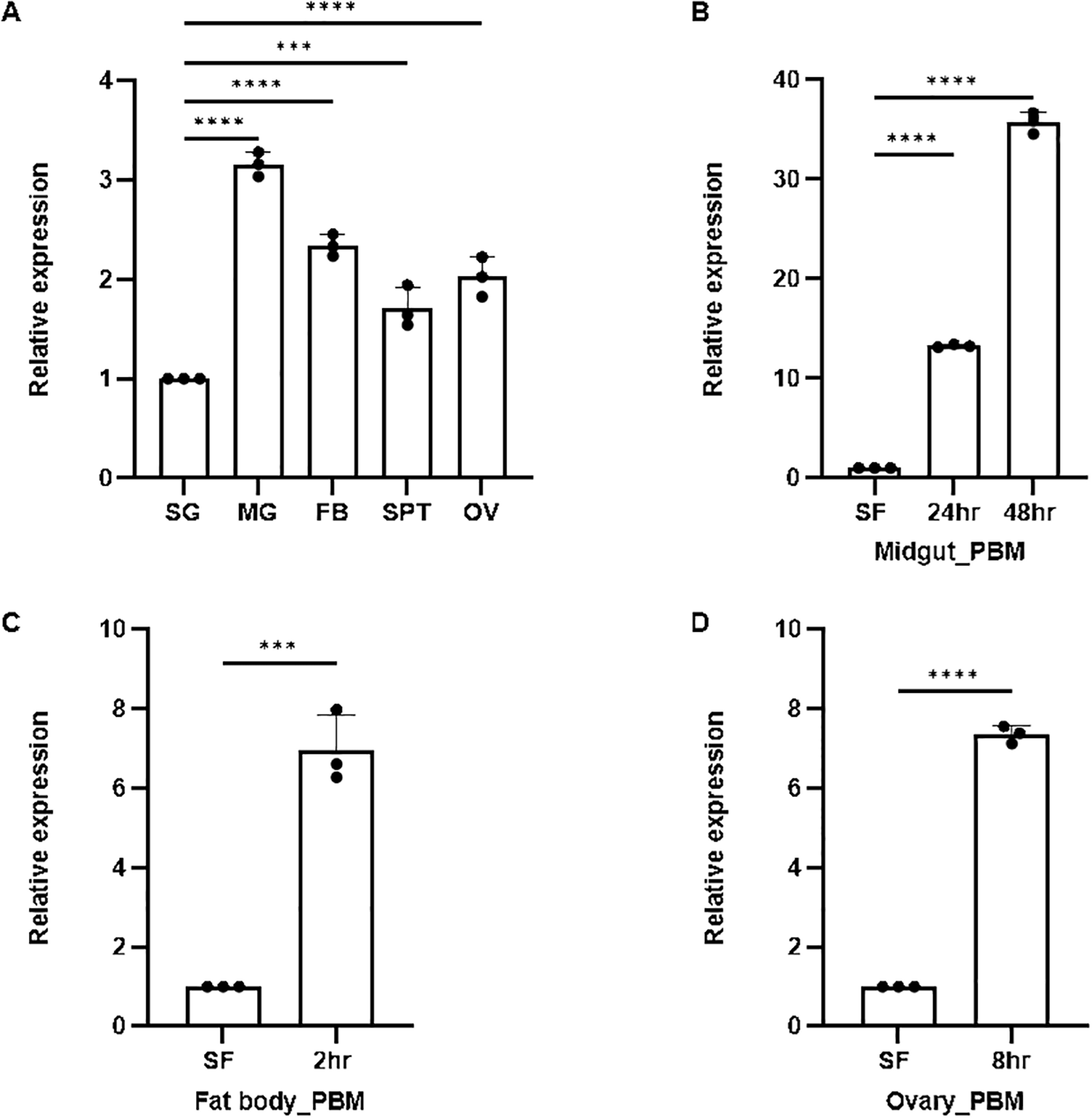

An enriched expression of AsSCP in the gut compared to other tissues in the naïve adult female mosquitoes (Figure 2a) prompted us to evaluate the effect of blood meal on its expression. First, we profiled and compared detailed time-dependent transcriptional responses of AsSCP in the midgut of blood-fed mosquitoes. Since blood meal serves as an excellent nutritional source through vitellogenesis and engages multiple organs, including the fat body and ovaries in storage and mobilization, we also monitored AsSCP expression in the fat body and the ovary of gravid female mosquitoes. Our observation of the gradual induction of AsSCP within the midgut epithelium (Figure 2b; also see Supplementary Figure 2) supports the idea that AsSCP may favor the absorption of cholesterol in the gut lumen (23). Our results are consistent with earlier work in Anopheles sacharovi, where SCP-2 transcripts were found to be highly enriched in the midgut and fat body. Similar expression patterns were observed in An. stephensi—with AsSCP strongly expressed in both tissues and further upregulated following a blood meal—suggesting a conserved role for SCP in regulating lipid assimilation and metabolism across anopheline species (24).

Figure 2

Spatio-temporal expression of SCP. (A) Real-time PCR-based tissue-specific expression analysis of SCP in different tissues of female mosquitoes observed highest expression in MG (p < 0.0001), FB (p < 0.0001), OV (p < 0.0001), and SPT (p < 0.0006). Here, salivary gland was considered as control for each test sample. (B) Relative expression profiling of SCP in the midgut after blood meal (24 hrs PBM and 48 hrs): SF (sugar-fed) was considered as control. All the samples were collected in three biological replicates and analyzed with the help of one-way ANOVA (Dunnett’s multiple comparison test) in GraphPad Prism. (C) Relative expression profiling of SCP in the FB after 2 hrs (p < 0.0003) blood meal: SF (sugar-fed) FB was considered as the control. (D) Relative expression profiling of SCP in the ovary after 8 hrs (p < 0.0001) blood meal: SF (sugar-fed) OV was considered as the control. Three independent biological replicates (n = 3, N = 30) were considered for statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005 and ****p < 0.0001) and calculated using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test with the help of GraphPad Prism. n, number of replicates; N, the number of mosquitoes pooled for sample collection; PBM, post blood meal; BF, blood fed; SG, salivary gland; MG, midgut; SPT, spermatheca; FB, fat body; OV, ovary; SF, sugar-fed; SCP, sterol carrier protein.

Large amounts of required proteins, such as lipophorin, responsible for lipid/sterol transport in circulation, or vitellogenin for egg maturation, are secreted by the fat body (20). Furthermore, in parallel, we observed an early [2 hr post blood meal (PBM)] multi-fold induction of AsSCP in the fat body (p < 0.0003; Figure 2c, Supplementary Figure 3). The results indicate that AsSCP may be involved in the transportation of cholesterol/sterol from the fat body to the hemolymph side for loading into lipophorin, in due course incorporating into the developing oocytes. Previous literature supporting this notion states that 24 hrs post blood meal, sterol from the fat body is utilized in the developing oocytes of Ae. aegypti (22). In the case of the ovary, a high expression of AsSCP 8 hr PBM was observed (p < 0.0001; Figure 2d, Supplementary Figure 4).

Modulation of AsSCP during P. vivax infection

Cholesterol is essential for cell membranes and cell signaling; therefore, its consumption by intracellular parasites for their development is typical in the host-vector. For example, Toxoplasma gondii acquires cholesterol from the host cells, and any interference with cholesterol uptake by the parasite significantly reduces the viability of the parasite (25). In mammalian hosts, the Plasmodium parasite scavenges the cholesterol lipid from the host erythrocyte membrane (26). Likewise, the Plasmodium oocysts in mosquito vectors may acquire fatty acids and phospholipids for developing oocysts and their structural development via lipophorin (LP), although during its development within the mosquito host, Plasmodium elicits tissue-specific differential immuno-physiological responses (27). However, the exact nature of the SCP involvement in Plasmodium infection is yet unclear.

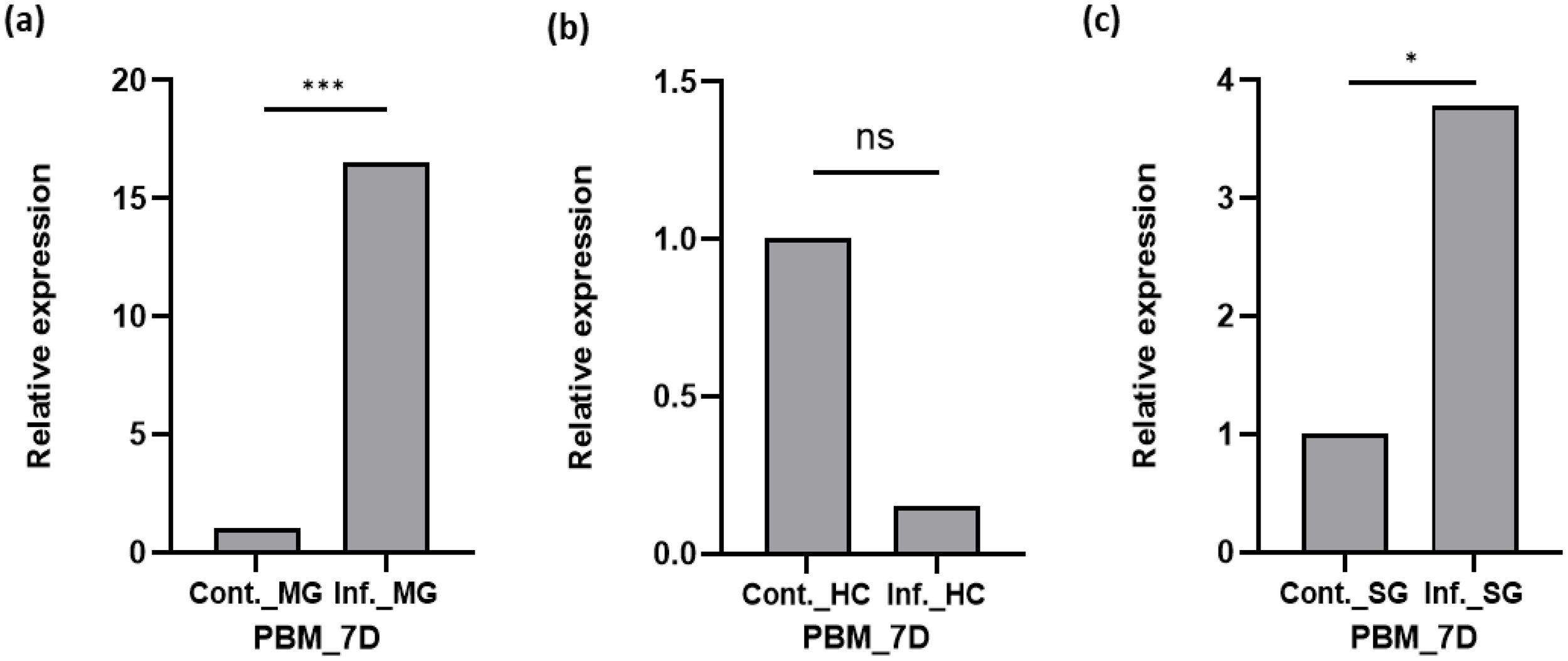

Because Plasmodium is incapable of synthesizing de novo cholesterol and heavily depends on the host’s nutritional resources for its development, therefore, we investigated whether the P. vivax infection alters the expression of SCP in the midgut (site for oocyst for 6–8 days), hemocyte (an immune organ), and salivary glands (hosts and stores sporozoites for Plasmodium transmission). We discerned that Plasmodium infection (Figure 3) induces a multifold SCP expression in the midgut 7 days post-infection (DPI; p < 0.000935; Figure 3a; also see Supplementary Figure 5), but hemocyte tissues depicted suppression of AsSCP expression (Figure 3b), while again, a heightened expression in the salivary glands was readily observable in the salivary glands (p < 0.011435; Figure 3c). Taken together, these observations suggest that the pronounced enrichment of SCP in the midgut and salivary glands may contribute to the provision of lipids or sterols to developing oocysts and emerging sporozoites, respectively. Our findings are consistent with previous reports showing that P. falciparum sporozoites significantly deplete lipid reserves in Anopheles gambiae, underscoring the importance of host-derived lipids for parasite development. In addition to a potential role in supplying cholesterol and other lipids to the oocyst, the modulation of AsSCP during P. vivax infection may reflect parasite-induced metabolic adjustments, reminiscent of the lipid metabolism remodeling described in the midgut of Ae. aegypti (28) during bacterial and viral infections. However, the lack of a reliable in vitro culture system for P. vivax limits our ability to directly assess the functional consequences of SCP modulation on parasite development and mosquito anti-Plasmodium immunity.

Figure 3

Transcriptional profiling of SCP in different tissues after Plasmodium vivax infection of mosquitoes. (a) Relative expression profiling of SCP in the midgut after P. vivax infection time series and control normal blood meal midgut (MG). (b) Relative expression profiling of SCP in hemocyte (HC) after P. vivax infection and control normal blood meal. (c) Relative expression profiling of SCP in salivary gland (SG) after P. vivax infection and control normal blood meal SG. Three independent biological replicates (n = 3, N = 30) were considered for statistical significance (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.005, and ***p < 0.0005) and calculated using Student’s t-test. n, the number of mosquitoes pooled for sample collection; N, number of replicates; HC, hemocyte; SG, salivary gland; PV, P. vivax; C, control; INF, infected; D, day; BF, blood-fed; SCP, sterol carrier protein. ns, non-significant.

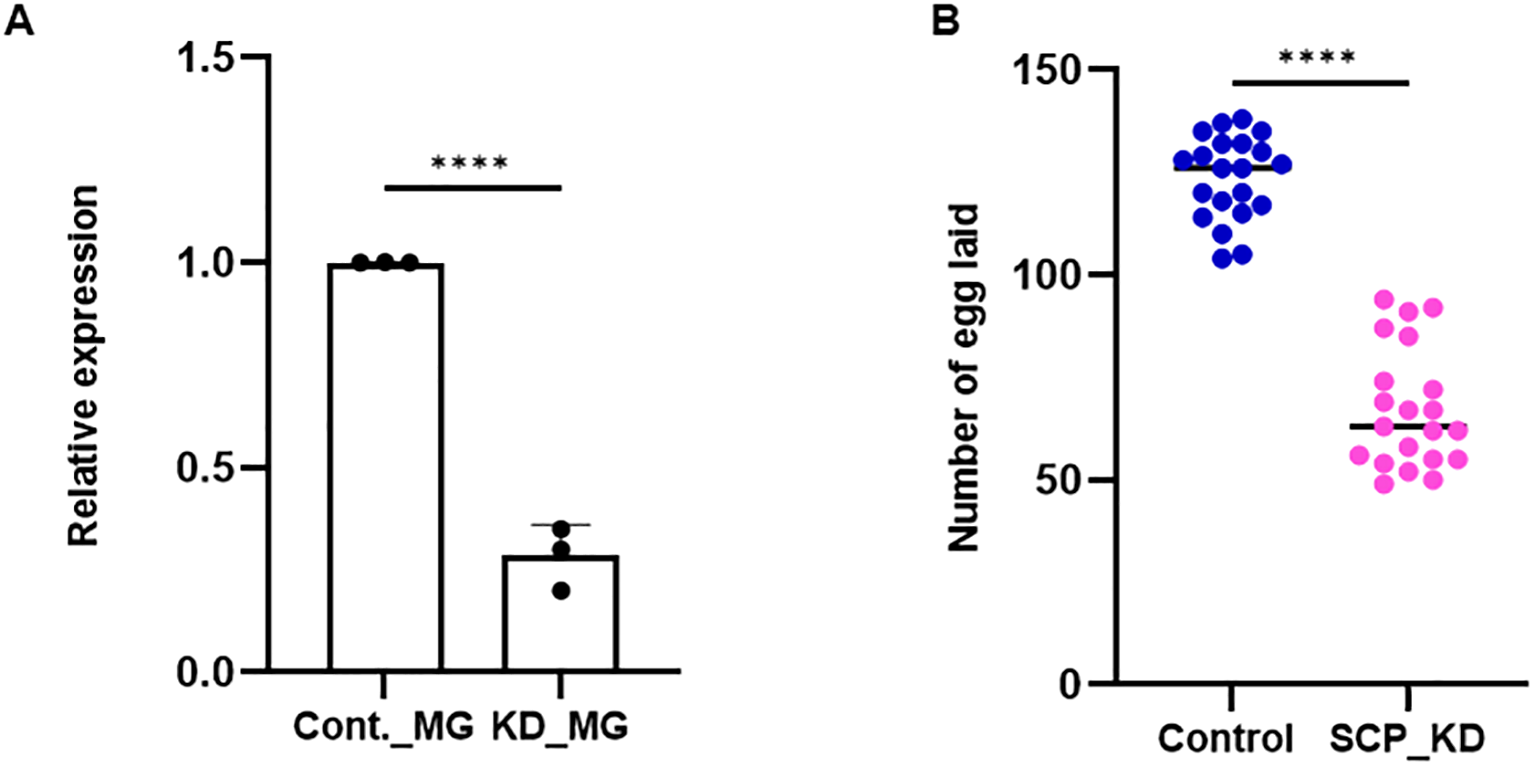

Functional knockdown (RNA silencing) of AsSCP and impact on mosquito fecundity

An early induction of AsSCP in the fat body and ovary after blood feeding compelled us to check the impact of AsSCP’s role on the reproductive physiology of the uninfected female mosquito, as the fat body and ovary are central tissues to mosquito reproduction. The ovary utilizes cholesterol for the biosynthesis of ecdysone hormone to initiate the vitellogenesis process.

The gene silencing strategy was followed, and an oviposition assay was performed. A significant depletion (~70%/p < 0.0001) of AsSCP mRNA was noticeable in the midgut (Figure 4a) of the adult female mosquitoes. After mating with naïve adult male mosquitoes, both silenced and control adult female mosquito groups were subjected to a blood meal to monitor reproductive success. A significant reduction (p < 0.0001) in the egg numbers laid by AsSCP-silenced adult female mosquitoes compared with controls (Figure 4b) suggests that SCP may have a direct role in the reproductive physiology of this mosquito species. These results reinforce SCP’s central role in reproductive physiology; however, at the same time, its nutritional role may represent a potential vulnerability to parasites, and thus, by impairing both fecundity and parasite-supportive pathways, SCP provides a dual advantage that may also inform future vaccine-oriented interventions.

Figure 4

SCP silencing effect on fecundity. (a)AsSCP silencing exhibited a >70% reduction in mRNA expression level as compared to control (p < 0.0001), as tested in the MG. A minimum of three biological replicates were performed and analyzed with the help of unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. (b) After mating with age-matched healthy male mosquitoes, AsSCP-silenced female mosquitoes were offered blood meal from rabbit, and 72 hrs after meal, silenced mosquitoes laid reduced number of eggs (p < 0.0001) compared with the control mosquito group. A minimum of three biological replicates were performed and analyzed with the help of unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (n = 3, N = 7 females/trial). n, number of replicates; N, the number of mosquitoes pooled for sample collection. All the statistical analyses were conducted with the help of GraphPad Prism. Cont., control; MG, midgut; KD, knockdown; SCP, sterol carrier protein. Statistically, **** represents data significance, which marks p < 0.0001.

In summary, previous studies have shown that SCP is essential for mosquito development, as chemical inhibition disrupts lipid uptake and causes larval mortality. Our findings extend this role to adults, demonstrating that RNAi-mediated suppression of AsSCP markedly reduces fecundity, underscoring SCP’s importance in both larval survival and adult reproductive success.

Conclusion

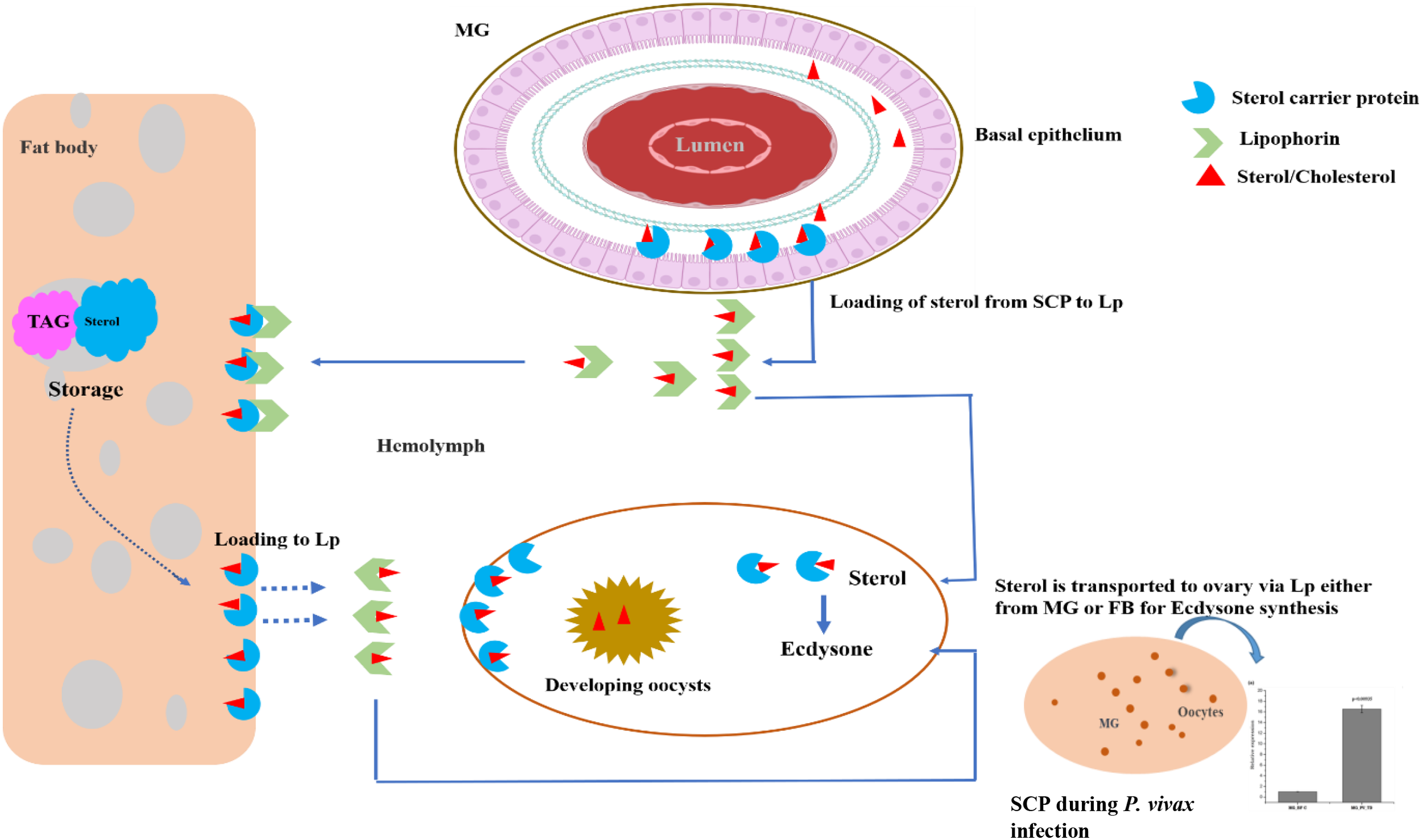

SCP inhibitors are known to exhibit larvicidal properties. However, its role in the regulation of nutritional physiology and Plasmodium development remains uncertain. In our study, we characterized and evaluated the molecular responses of the sterol carrier protein (AsSCP) gene in response to blood feeding and Plasmodium infection in the An. stephensi mosquitoes. Although we do not provide any functional experimental proof, our transcriptional profiling concerning P. vivax infection suggests that AsSCP may be providing lipids/sterols to the developing oocysts. However, further additional studies based on SCP’s knockout or knockdown infection assay will clarify its specific role in Plasmodium growth and survival. Tissue-specific alteration in response to blood meal uptake and functional knockdown experiments demonstrated that AsSCP probably plays a crucial role in egg development. While reproduction remains the dominant phenotype, its dual involvement in nutrition and infection suggests that SCP may serve as a bridge between physiology and immunity. Here, we propose that AsSCP (Figure 5) may serve as a unique target to disrupt nutrition-dependent Plasmodium development as well as mosquitoes’ reproduction, opening the door for innovative transmission-blocking tools for malaria control.

Figure 5

A proposed hypothesis for the possible role of AsSCP in the adult female mosquito. The mosquito acquires the dietary cholesterol from the blood meal once inside the midgut epithelial cell. A small fraction of sterol, along with other lipids, is stored in the lipid droplet of the midgut, and the remaining amount of sterol/lipid is transported intracellularly toward the basal side of the midgut via SCP and loaded into lipophorin for transportation to the fat body. During oogenesis, SCP facilitates the mobilization and transport of stored sterol within the fat body and loads it into lipophorin for the developing oocyte. During the early hours of blood feeding, the sterol is intracellularly transported to the site of utilization within the ovary, where sterol is converted into ecdysone to initiate the process of vitellogenesis. A blood meal or a fat body could be the source of sterol in the ovary. Although SCP induction after blood feeding suggests a link to ecdysone production via sterol transport, we did not measure ecdysone; LC–MS/MS-based quantification is needed to confirm this metabolic connection. SCP, sterol carrier protein.

Limitations and future directions

The findings of our study demonstrate that SCP is associated with mosquito reproduction and modulation in its gene expression pattern during P. vivax infection, although we have provided no experimental evidence of how it influences ecdysone production or Plasmodium growth. Due to limitations of P. vivax culture and/or availability of P. vivax-infected blood samples, we were not able to check the parasite load after SCP silencing. In future studies, if possible, we intend to carry out an infection study in RNAi-silenced mosquitoes to check how the knockdown of SCP influences the parasite growth and transmission if we are able to obtain fresh infected samples. Additionally, we also intend to assess the hormone level using Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) in SCP-silenced female mosquitoes after blood feeding to check whether impaired sterol transport results in lower ecdysone production and egg formation. This functional experiment will clarify SCP’s role in mosquito metabolism, reproduction, and infection.

Statements

Data availability statement

The SCP was identified from the RNAseq data of the midgut and was deposited to NCBI with Accession number (Migut-control: SRR8580010; Midgut-Infected: SRR8580011).

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institute Ethics Committee, ICMR-National Institute of Malaria Research. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The animal study was approved by Institute Animal Ethics Committee, ICMR-National Institute of Malaria Research. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

PY: Visualization, Writing – original draft. SK: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NS: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. JR: Writing – review & editing. GS: Writing – review & editing. CC: Writing – review & editing. ST: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RD: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The work in the laboratory was supported by the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India (BT/HRD/35/02/01/2009), and ICMR Grant (Ref # VBD/NIMR/Intra/002-ECD-II). ST is a recipient of the UGC Research Fellowship (22/12/2013(II)EU-V), and SK is a recipient of the CSIR Research Fellowship (09/905 (0015)/2015-EMR-1).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the technical staff members of the central insectary for mosquito rearing and Kunwarjeet Singh for the laboratory assistance. We are grateful to the patients of the malaria clinic, who contributed to the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor CP declared a past co-authorship with the author RD.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1703479/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Charlwood JD Smith T Billingsley PF Takken W Lyimo EOK Meuwissen J . Survival and infection probabilities of anthropophagic anophelines from an area of high prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum in humans. Bull Entomol Res. (1997) 87:445–53. doi: 10.1017/S0007485300041304

2

Guerra CA Howes RE Patil AP Gething PW Van Boeckel TP Temperley WH et al . The international limits and population at risk of Plasmodium vivax transmission in 2009. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2010) 4:e774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000774

3

Phasomkusolsil S Tawong J Monkanna N Pantuwatana K Damdangdee N Khongtak W et al . Maintenance of mosquito vectors: effects of blood source on feeding, survival, fecundity, and egg hatching rates. J Vector Ecol. (2013) 38:38–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1948-7134.2013.12006.x

4

Mamai W Bimbile-Somda NS Maiga H Juarez JG Muosa ZAI Ali AB et al . Optimization of mosquito egg production under mass rearing setting: effects of cage volume, blood meal source and adult population density for the malaria vector, Anopheles arabiensis. Malar J. (2017) 16:41. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1685-3

5

Kim M Wessely V Lan Q . Identification of mosquito sterol carrier protein-2 inhibitors. J Lipid Res. (2005) 46:650–7. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400389-JLR200

6

Perera H Wijerathna T . Sterol carrier protein inhibition-based control of mosquito vectors: current knowledge and future perspectives. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. (2019) 2019:7240356. doi: 10.1155/2019/7240356

7

Krause MR Regen SL . The structural role of cholesterol in cell membranes: from condensed bilayers to lipid rafts. Acc Chem Res. (2014) 47:3512–21. doi: 10.1021/ar500260t

8

Patra SK . Dissecting lipid raft facilitated cell signaling pathways in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Reviews Cancer. (2008) 1785:182–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.11.002

9

Schroeder F Atshaves BP McIntosh AL Gallegos AM Storey SM Parr RD et al . Sterol carrier protein-2: new roles in regulating lipid rafts and signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Molecul Cell Biol Lipids. (2007) 1771:700–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.04.005

10

Kim M-S Lan Q . Sterol carrier protein-x gene and effects of sterol carrier protein-2 inhibitors on lipid uptake in Manduca sexta. BMC Physiol. (2010) 10:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-10-9

11

Halling KK Ramstedt B Nyström JH Slotte JP Nyholm TKM . Cholesterol interactions with fluid-phase phospholipids: effect on the lateral organization of the bilayer. Biophys J. (2008) 95:3861–71. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.133744

12

Zhao YO Kurscheid S Zhang Y Liu L Zhang L Loeliger K et al . Enhanced survival of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes during starvation. PloS One. (2012) 7:e40556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040556

13

Kumari S Chauhan C Tevatiya S Singla D Das De T Sharma P et al . Genetic changes of Plasmodium vivax tempers host tissue-specific responses in Anopheles stephensi. Curr Res Immunol. (2021) 2:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.crimmu.2021.02.002

14

Tevatiya S Kumari S Sharma P Rani J Chauhan C Das De T et al . Molecular and functional characterization of trehalase in the mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Front Physiol. (2020) 11:575718. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.575718

15

Thomas T Das De T Sharma P Lata S Saraswat P Pandey KC et al . Hemocytome: deep sequencing analysis of mosquito blood cells in Indian malarial vector Anopheles stephensi. Gene. (2016) 585:177–90. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.02.031

16

Chauhan C Das De T Kumari S Rani J Sharma P Tevatiya S et al . Hemocyte-specific FREP13 abrogates the exogenous bacterial population in the hemolymph and promotes midgut endosymbionts in Anopheles stephensi. Immunol Cell Biol. (2020) 98:757–69. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12374

17

Sharma P Rani J Chauhan C Kumari S Tevatiya S Das De T et al . Altered gut microbiota and immunity defines Plasmodium vivax survival in Anopheles stephensi. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:609. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00609

18

Sharma P Sharma S Mishra AK Thomas T Das De T Rohilla SL et al . Unraveling dual feeding associated molecular complexity of salivary glands in the mosquito Anopheles culicifacies. Biol Open. (2015) 4:1002–15. doi: 10.1242/bio.012294

19

Gaudet P Livstone MS Lewis SE Thomas PD . Phylogenetic-based propagation of functional annotations within the Gene Ontology consortium. Brief Bioinform. (2011) 12:449–62. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbr042

20

Hiruma K Kaneko Y . Hormonal regulation of insect metamorphosis with special reference to juvenile hormone biosynthesis. Curr Top Dev Biol. (2013) 103:73–100. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385979-2.00003-4

21

Guo X-R Zheng S-C Liu L Feng Q-L . The sterol carrier protein 2/3-oxoacyl-CoA thiolase (SCPx) is involved in cholesterol uptake in the midgut of Spodoptera litura: gene cloning, expression, localization and functional analyses. BMC Mol Biol. (2009) 10:102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-102

22

Blitzer EJ Vyazunova I Lan Q . Functional analysis of AeSCP-2 using gene expression knockdown in the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aEgypti. Insect Mol Biol. (2005) 14:301–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2005.00560.x

23

Jouni ZE Zamora J Wells MA . Absorption and tissue distribution of cholesterol in Manduca sexta. Arch Insect Biochem Physiology: Published Collab Entomolog Soc America. (2002) 49:167–75. doi: 10.1002/arch.10017

24

Aygün S Düzlü Ö Yıldırım A . Molecular characterization and expression analysis of the sterol-carrier protein-2 fragment in anopheles sacharovi generations. Turkish J Parasitol. (2022) 46:312–321. doi: 10.4274/tpd.galenos.2022.68553

25

Nolan SJ Romano JD Kline JT Coppens I . Novel approaches to kill Toxoplasma gondii by exploiting the uncontrolled uptake of unsaturated fatty acids and vulnerability to lipid storage inhibition of the parasite. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2018) 62:10–1128. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00347-18

26

Petersen W Stenzel W Silvie O Blanz J Saftig P Matuschewski K et al . Sequestration of cholesterol within the host late endocytic pathway restricts liver-stage Plasmodium development. Mol Biol Cell. (2017) 28:726–35. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e16-07-0531

27

Smith RC Jacobs-Lorena M . “Plasmodium–mosquito interactions: a tale of roadblocks and detours”. In: Advances in insect physiology, vol. 39. Elsevier (2010) 39:119–49. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381387-9.00004-X

28

Barletta ABF Alves LR Nascimento Silva MCL Sim S Dimopoulos G Liechocki S et al . Emerging role of lipid droplets in Aedes aEgypti immune response against bacteria and Dengue virus. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:19928. doi: 10.1038/srep19928

Summary

Keywords

mosquito, sterol-carrier protein, nutritional physiology, anti-Plasmodium immunity, reproduction

Citation

Kumari S, Yadav P, Sankhala N, Rani J, Sharma G, Chauhan C, Tevatiya S and Dixit R (2025) Plasmodium vivax infection-driven modulation of sterol carrier protein reveals a metabolic link to reproductive physiology in Anopheles stephensi. Front. Immunol. 16:1703479. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1703479

Received

11 September 2025

Revised

15 November 2025

Accepted

21 November 2025

Published

11 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Chiranjib Pal, West Bengal State University, India

Reviewed by

Arijit Bhattacharya, Adamas University, India

Madhuri Dutta, Virginia Commonwealth University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Kumari, Yadav, Sankhala, Rani, Sharma, Chauhan, Tevatiya and Dixit.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sanjay Tevatiya, sanjaycena51@gmail.com; Rajnikant Dixit, rkdixit@icmr.gov.in

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.