- 1Department of Biological Sciences, George Washington University, Washington, WA, United States

- 2Noblis, Science Technology and Engineering, Reston, VA, United States

- 3Histopathology and Tissue Shared Resource, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Georgetown University, Washington, WA, United States

Xenopus laevis juvenile frogs regenerate wounded skin without scarring, yet the underlying mechanisms driving this process remain poorly defined. Macrophages are critical to wound repair across vertebrates, and our results indicate a transient influx of macrophages into regenerating frog wounds. The colony stimulating factor-1 (CSF1) and interleukin-34 (IL34) growth factors control macrophage development. Through RNA in situ hybridization studies, we found that csf1 gene expression peaked early during juvenile frog wound responses, whereas il34 expression increased later in the repair process. Our past studies indicate that X. laevis CSF1- and IL34-differentiated macrophages are functionally distinct. Presently, we treated frog wounds with recombinant (r)CSF1 and rIL34 to determine the roles of the corresponding macrophage subsets in wound repair. Using a combination of RNA in situ hybridization, RNA sequencing and histology, we demonstrated that wounds skewed towards greater proportions of rCSF1-macrophages exhibited greater infiltration of leukocytes, chiefly amongst them neutrophils. These wounds also possessed robust expression of inflammatory genes and transcripts associated with granulation and fibrosis. By contrast, rIL34-treated frog wounds exhibited greater fibroblast activation concurrent with greater type I/III collagen ratios and expression of genes typically seen at later phases of wound repair. Together, we propose that while CSF1-macrophages are likely more prominently involved in the inflammatory phase of X. laevis wound repair, IL34-macrophages predominate the later reparative phase of these responses.

1 Introduction

Mammalian skin is composed of epidermal and dermal layers, and when the latter is damaged, the lost tissue is replaced with collagenous scar tissue, devoid of secondary structures such as sweat glands or hair follicles (1–3). These scars may be disfiguring and lack some of the functions of the original dermal tissue, often resulting in cosmetic and/or medical issues (4). Mammalian immune systems play critical roles during all phases of wound repair, from the initial inflammation to the resolution of the inflammatory response and the ensuing coordinated repair pathways (5). Notably, amphibians possess immune systems remarkably similar to those of mammals (6) and yet have impressive capacities to repair and regrow damaged tissues and even limbs (7, 8). Urodele amphibians (newts and salamanders), and pre-metamorphic anuran amphibians (frogs and toads) can regrow whole limbs and some organs. In contrast, post-metamorphic anurans lack these regenerative capacities but do exhibit a remarkable propensity to regenerate wounded skin without forming scars (4, 9, 10).

Macrophage (Mϕ) lineage cells are critical to skin wound repair (11, 12) including coordinating inflammation (4), clearing of debris and dead cells (13), promoting vascularization (4) and re-epithelialization (4), facilitating extracellular matrix deposition (14), and recruiting and activating fibroblasts (2, 15). The involvement of Mϕs in the process of wound repair appears to be evolutionarily conserved across vertebrates, from fish to mammals (5, 16–19). In the early phases of mammalian wound healing, resident and infiltrating Mϕs predominantly express pro-inflammatory mediators, transitioning to anti-inflammatory profiles as wound healing progresses (16). How Mϕ subtypes participate in wound repair outside of mammals remains largely unknown.

While vertebrates possess numerous Mϕ-lineage subsets (20, 21), the differentiation and functionality of all vertebrate Mϕs depend on the colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF1R), which is ligated by CSF1 and interleukin-34 (IL34) cytokines (22). Dimeric IL34 and CSF1 both interact with dimerized CSF1R (23), with IL34 exhibiting greater affinity and slower dissociation from CSF1R (23, 24), thus resulting in more sustained and stronger cell signaling (25) (reviewed in 26). CSF1 exclusively signals through the CSF1R, whereas IL34 also binds to the receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase-ζ (PTP-ζ) (27) and chondroitin sulfates, chiefly amongst these syndecan-1 (28). IL34-PTP-ζ interactions contribute to microglia homeostasis in the CNS whereas binding of IL34 to syndecan-1 serves as a means of regulating IL34 bioavailability and thus IL34-mediated CSF1R activation (27–29).

CSF1 and IL34 appear to confer at least partially non-overlapping roles in Mϕ development, homeostasis and polarization (29–31). For example, CSF1R signaling is essential for Langerhans cell (LC) development in most vertebrates (32) with IL34 being more critical to steady-state maintenance of LCs (30), while CSF1 contributes to LC development during skin inflammatory responses (33) (reviewed in 34, 35). The more recently discovered IL34 has also been linked with the development and maintenance of osteoclasts (36), microglia (37), and B-cell-stimulating mononuclear phagocytes (38). Indeed, human Mϕs differentiated with CSF1 and IL34 possess disparate polarization, with IL34-Mϕs exhibiting greater expression of IL10 and CCL17 (39) and greater resistance to HIV1 (40) and mycobacteria (41).

Mammalian CSF1-Mϕs have been implicated in tissue remodeling (42) and wound repair (43) and likewise, IL34-Mϕs promote healing (30) and collagen deposition (29). In turn, our previous studies indicate that frog (Xenopus laevis) CSF1- and IL34-Mϕs are morphologically and functionally distinct (44, 45). Both csf1 and il34 genes are expressed in healthy X. laevis skin (46), suggesting that CSF1- and IL34-Mϕs are both constitutively present in this tissue. Presently, we investigated the roles of these CSF1- and IL34-Mϕs in X. laevis scarless skin wound repair.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Animal husbandry, wounding, and cytokine administration

Xenopus laevis juveniles (animals that have undergone metamorphosis within the past 30 days) were purchased from Xenopus 1 (Dexter, Michigan, USA) and reared in an aquatics laboratory in-house. Frogs were housed in an XR5 aquatic housing unit (IWAKI), and the water was filtered with carbon and sedimentation flow-through filtration systems. All animals were handled under the strict laboratory regulations of the Animal Research Facility at The George Washington University (GWU) and as per the GWU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee regulations (Approval number A2023-044).

X. laevis juveniles (weighing approximately 2g) were anesthetized with 1g/L tricaine methanesulfonate (TMS), and sterile 2 mm biopsy punches (Royaltek) were used to excise both epidermal and dermal layers of dorsal skin while leaving the underlying musculature intact. Frogs were allowed to recover on moist filter floss and returned to water when recovered.

For Mϕ polarization experiments, frogs were subcutaneously injected at 3 days post-wounding (dpw) with 20μL (1μg/animal) of rCSF1, rIL34, or an equal volume of rctrl (generated as described below) in sterile amphibian-PBS.

2.2 Recombinant X. laevis CSF1 and IL34

We previously described the production of X. laevis recombinant (r)CSF1 and rIL34 (44, 45). Briefly, pMIB/V5His A (Invitrogen, Cat # V803001) insect cell expression constructs containing the signal peptide-cleaved representations of respective cytokine cDNAs were generated and transfected into Sf9 insect cells via Cellfectin II (Invitrogen, Cat # 10362100). Successfully transfected cells were selected using 100 μg/mL blasticidin, and expression was confirmed by Western Blot. Cultures were scaled to 300 mL, grown to confluency (5–6 x 106 cells/mL), and the culture supernatants (sups) were dialyzed overnight at 4 °C against PBS, pH 8. Recombinant proteins were isolated from dialyzed sups using Ni-NTA Resin Beads (Thermo Scientific, Cat # PI88221), which were washed with 5 × 10 mLs of low-stringency wash buffer (50 mM Sodium Phosphate; 1 M Sodium Chloride; 40 mM Imidazole). Recombinant cytokines were eluted using 250 mM imidazole and were confirmed by Western blot against the V5 epitopes. Proteins were concentrated in polyethylene glycol at 4 °C to a volume of approximately 1mL and then dialyzed overnight at 4 °C against amphibian-PBS (APBS; 6.6g/L NaCl, 1.15g/L Na2HPO4, 0.4g/L KH2PO4), pH 7.4. Protein concentrations were determined by NanoDrop (RRID: SCR_023005). Proteins were stored at -20 °C in sterile aliquots until use.

A recombinant control (rctrl) was generated by transfecting Sf9 cells with an empty pMIB/V5 His A expression vector, selecting positive transfectants with blasticidin, scaling up these cultures, and processing the derived sups using the same approaches described above for rCSF1 and rIL34 production.

2.3 Histology and microscopy

Animals were euthanized by TMS overdose (5g/L) followed by cervical dislocation. The dorsal skins of individual animals were excised and fixed for 24 hrs in 10% NBF, transferred to 70% EtOH, and trimmed to a 6mm circle surrounding the wound (or a 6mm whole skin sample for controls). All tissues were processed at the Histopathology & Tissue Shared Resource at Georgetown University, District of Columbia. Tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned (5 μm), and stained with either hematoxylin and eosin, Picrosirius red (PSR; ScyTek, Cat #SRS250), or used for RNA in situ hybridization (RNA-ISH), as described below. Histology stains were performed according to the respective manufacturers’ instructions.

Hematoxylin and eosin and PSR-stained tissues were examined using either polarized light microscopy and/or brightfield microscopy using a Leica DMi8 Inverted Fluorescence Microscope at the GWU Nanofabrication and Imaging Center.

2.4 RNAScope fluorescent and chromogenic RNA-in situ hybridization

RNA-ISH was performed according to the instructions of the manufacturer, Advanced Cell Diagnostics (RRID: SCR_012481), documents USM322500, UM323100, and UM3400 and published by Wang et al. in 2012 (47). Briefly, tissues were fixed and sectioned as described above. The tissue was then deparaffinized, target retrieval was performed, and X. laevis-specific il34 (Cat # 1220711-C1), csf1 (Cat #1220701-C2), csf1r (Cat #1310031-C3), mpo (Cat # 1310041-C3), and acta2 (Cat #1310051-C3) RNA probes were hybridized onto the tissue sections. X. laevis-specific positive control probes Cyclophilin B (ppib; Cat #580861-C2) and DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB1 (polr2a; Cat #580841) and a negative control probe targeting dapB (Cat # 320871) from the soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis, were run in conjunction with each staining trial. Through a series of amplifications and developments, color-based signals were developed either using chromogenic stains or fluorescent probes. Images were acquired using a Leica DMi8 Inverted Fluorescence Microscope and analyzed using ImageJ, as described below.

2.5 Image analyses

All images were acquired with scale bars, which were used in ImageJ (RRID: SCR_003070) to assign scale to respective images and calculate areas of interest. Numbers of transcript-positive cells and quantities of transcripts were enumerated and quantified as proportions of tissue areas. When deemed helpful, RNA-ISH images were inverted using ImageJ software to optimally visually differentiate transcript staining from background staining.

Collagen I and III composition was quantified using ImageJ Trainable Weka Segmentation plugin, with the classifier trained to determine red, orange, yellow, green, and black (background) pixels within our PSR images. Some images were segmented into tiles for processing efficiency, and the same classifier was then applied to all respective images, and image averages were calculated. Color percentages as defined by the classifier were then quantified per target area and averaged across samples. Type I/type III collagen ratios were calculated by dividing the percent area of pixels with red, orange, or yellow (type I) by the percent area of pixels with green (type III) for each sample. To better visualize collagen organization, select polarized light images were also converted to black and white image casts using the built-in thresholding software.

2.6 RNA isolation and sequencing

For all experiments, tissues and cells were flash frozen in TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen, Cat #15596026) on dry ice and stored at -20 °C. RNA isolation was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and samples were stored at -80 °C. Strand-specific RNA sequencing was performed by GENEWIZ (RRID: SCR_003177). Briefly, ribosomal RNA was depleted using a removal kit to enrich for messenger RNA and remove non-coding transcripts. Strand-specific RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (Cat # E7760S) or equivalent, following the manufacturer’s instructions, to preserve strand directionality. Library quality was confirmed via Qubit quantification and Bioanalyzer profiling. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 Sequencing System (RRID: SCR_016387) platform using paired-end 150 bp reads, generating a minimum of 30 million reads per sample. Raw sequencing data was delivered in FASTQ format and subjected to downstream quality control and differential expression analysis using fastqc (v0.12.1) to view the quality of reads and fastp (v1.0.1) for adapter trimming with flag –detect_adapter_for_pe.

2.7 RNA sequencing analysis

Raw sequencing data was mapped to the RefSeq (RRID: SCR_003496) Xenopus_laevis_v10.1 GCF_017654675.1 assembly using Minimap2 (RRID: SCR_018550) with “-ax sr” and SAMTOOLS (RRID: SCR_002105) to produce a .bam file for each paired-end read set. An expression matrix was produced from all samples using featureCounts (RRID: SCR_012919) with parameters “–countReadPairs -B -t exon -g gene_id” using the GCF_017654675.1 genomic.gtf annotated from NCBI (RRID: SCR_006472). Downstream RNA sequencing analysis was performed using the iDEP: Integrated Differential Expression and Pathway analysis (RRID: SCR_027373) web application. Briefly, raw count data was pre-processed by removing lowly expressed genes and genes with 0.5 counts per million in at least 10 libraries were retained for further analysis. DESeq2 (RRID: SCR_015687) was then used to identify differentially expressed genes, where an adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Data is available on NCBI under GEO accession number GSE306422 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE306422).

2.8 Statistical analyses

Where applicable, quantitative data was normalized to either the number of transcript-positive cells or the number of transcripts per unit area. Statistical analyses of all quantitative data (including Picrosirius red quantification data) were performed in RStudio (RRID: SCR_000432), using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test to determine pairwise significance. Data plotted in bar graphs is representative of two independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). RNA-seq expression data was averaged for each treatment across each time point, and the statistical significance of transcript expression across treatments was calculated in RStudio via pairwise Wilcox tests. The whiskers of box plots extend to the largest and smallest values within 1.5× the interquartile range from the box.

3 Results

3.1 Kinetics of juvenile X. laevis skin wound repair

We developed a biopsy punch approach to study X. laevis skin wound repair and examined the process over 60 days post wounding (dpw; localized epidermal and dermal dorsal skin damage; Figure 1). At 7 dpw we observed established wound epidermis (“WE”) several cells thick without distinguishable epidermal or dermal layers (Figure 1B). By 14 dpw demarcated epidermal and dermal layers were restored with skin glands beginning to form (Figure 1C) and by 21 dpw, the skin architecture was substantially restored, albeit with underdeveloped skin glands (Figure 1D). By 28 dpw, the repair process was substantially advanced and nearly complete by 60 dpw (Figures 1E, F). Top-down views of unwounded skin and healing wounds across the same time course complement our histological analysis (Figures 1G–N). At 60 dpw, the healed wound is indistinguishable from the surrounding tissue (Figure 1N), corroborating what we observe histologically.

Figure 1. Juvenile X. laevis skin regeneration over time. (A–F) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) – stained skin sections from (A) unwounded controls (ctrl) and at (B) 7, (C) 14, (D) 21, (E) 28 and (F) 60 days post wounding (dpw). Open arrowheads mark wound edges. Control skin showing epidermis (E), dermis (D), and well-defined mucus (M) and serous (S) glands. WE, wound epidermis. (G–N) Top-down images of (G) control skin and wounds at (H) 0, (I) 3, (J) 7, (K) 14 (L) 21, (M), 28 and (N) 60 dpw. Contrast and brightness adjusted uniformly across images.

3.2 Involvement of Mϕs, CSF1, and IL34 in regenerating frog skin wounds

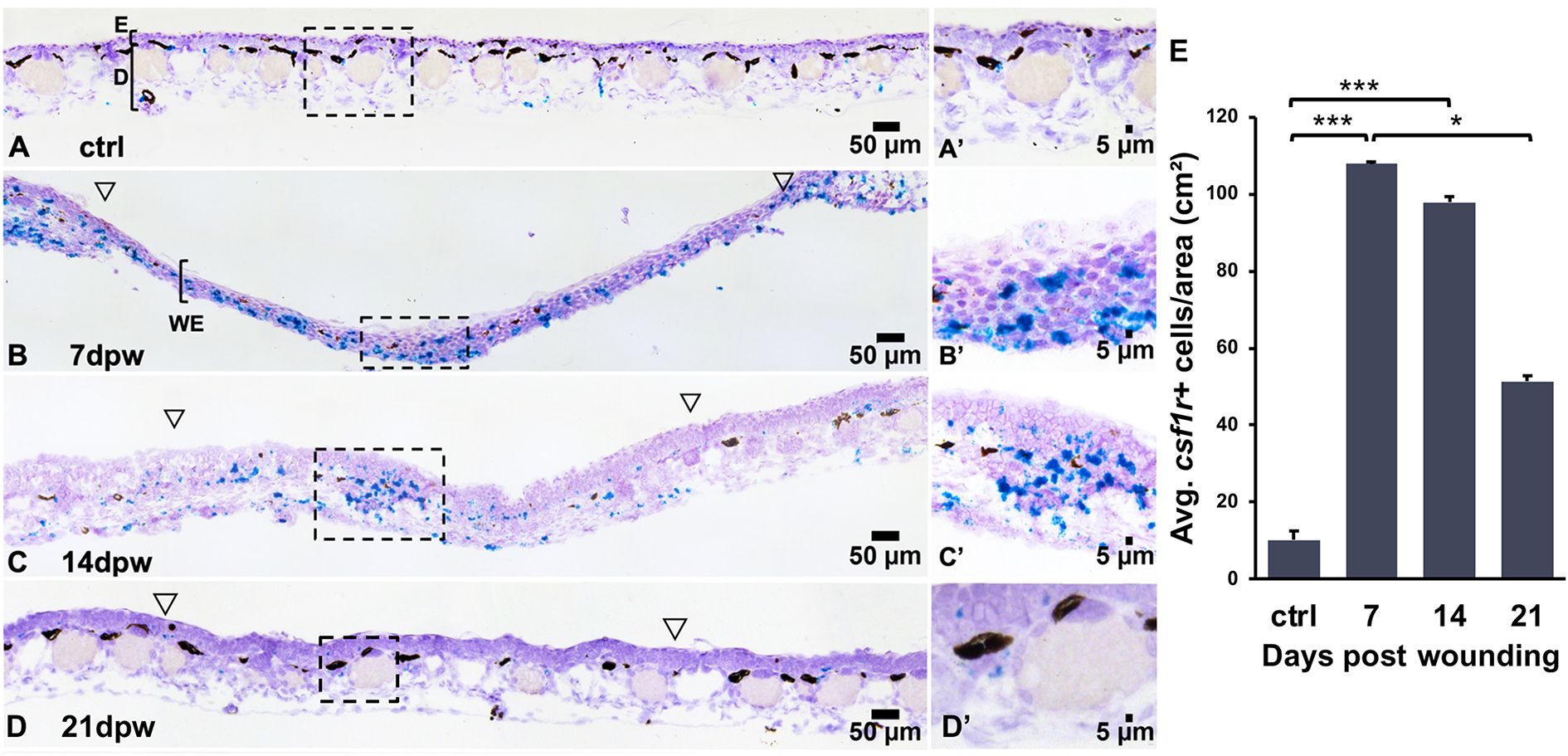

The colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) is indispensable to Mϕ biology, thus serving as a well-established marker of this leukocyte lineage (6). As such, we used csf1r expression to visualize Mϕs in regenerating X. laevis skin wounds. To characterize the kinetics of early X. laevis skin wound repair, full thickness wound areas from dorsal skins were collected at 0, 7, 14, and 21 dpw and Mϕs were visualized using RNA in situ hybridization (RNA-ISH), targeting csf1r transcripts (Figure 2). Unfortunately, the regenerating wound epithelia proved too fragile for histological processing of tissues earlier than 7 dpw. Our results indicate that Mϕs were present in healthy frog skins at relatively low levels, predominating in the dermal layers (Figures 2A, A’). Following skin wounding, high numbers of csf1r+ cells could be seen infiltrating the WE at 7 dpw, with dense clusters appearing both within the wound bed and at the wound margins (Figures 2B, B’). With the WE thickening and dermal tissues beginning to reform by 14 dpw, the elevated csf1r+ cell numbers persisted within regenerating wounds as clusters of Mϕs within the wound beds (Figures 2C, C’). By 21 dpw, wound csf1r+ Mϕ numbers had markedly declined, suggesting the resolution of Mϕ infiltration, as regeneration progressed (Figure 2D, D’). Quantification of these wound-infiltrating csf1r+ cells confirmed these observations, wherein the numbers of csf1r+ cells per area were significantly elevated at 7 and 14 dpw compared to controls/unwounded skin (p < 0.001) and significantly decreased by 21dpw (p < 0.05, Figure 2E). Together, this data highlights a dynamic but transient Mϕ response in the regenerating skin, with maximal WE infiltration during the early and mid-phases of healing, followed by a decline as wound resolution occurs.

Figure 2. Csf1r+ macrophages accumulate transiently during wound repair. (A–D′) RNA in situ hybridization detecting csf1r+ cells (teal) in (A, A′) unwounded skin and at (B, B′) 7, (C, C′) 14 and (D, D′) 21 days post wounding (dpw). Open arrowheads mark wound edges, boxed regions indicate higher magnification in A′–D′. (E) Quantification of csf1r+ cell density (cells/cm²). Data are mean ± SEM (n = 4-5 biological replicates per group). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

To gain greater insight into Mϕ subtype involvement during skin regeneration, we next examined the expression patterns of principal Mϕ growth factors, colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF1) and interleukin-34 (IL34) following skin wounding. Using RNA-ISH, we quantified transcripts per wounded area from tissue sections collected at 0, 7, 14, and 21 dpw (Figure 3). Transcript levels of csf1 and il34 in healthy, unwounded skin were low (Figures 3A, E), coinciding with our observations of relatively low proportions of Mϕs in healthy skin (Figures 2A, E). Expression of csf1 was significantly elevated at 7 dpw compared to unwounded control levels (p < 0.01) and was significantly higher at that timepoint than il34 expression (p < 0.01; Figure 3E). Expression of csf1 declined thereafter, with significantly lower levels detected at 14 dpw from 7 dpw (p < 0.05, Figure 3E, significance not shown). In contrast, il34 expression showed a more gradual increase following wounding, with the greatest expression observed 14 and 21 dpw (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05 compared to ctrl; Figure 3E). This suggests a shift in proportions of CSF1- to IL34-Mϕs with progressing wound repair.

Figure 3. Expression of csf1 and il34 in regenerating skin wounds. (A–D) RNA in situ hybridization detecting csf1 (magenta) and il34 (blue/teal) transcripts in (A) unwounded skin, and skin at (B) 7, (C) 14 and (D) 21 days post wounding (dpw; counterstained with hematoxylin). WE, wound epidermis; E, epidermis; D, dermis. (E) Quantification of csf1 and il34 transcript density (transcripts/cm²). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 4-7 biological replicates per group). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; p < 0.05. Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance from ctrl. Asterisks (**) above bar denotes significance between the groups indicated by the bar. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

3.3 Proportions of CSF1- and IL34-Mϕs influence the immune status of wounded skin

The transition from injury-induced inflammation to a resolution and repair phase is critical to prevent fibrotic scarring during wound healing (48). In mammals, pro-inflammatory Mϕs are present early on during wound formation/repair (5, 49, 50), producing inflammatory mediators (50). As inflammation resolves and wound healing transitions into proliferative and remodeling phases, Mϕs traditionally shift towards immune suppression and tissue remodeling phenotypes (5, 49). To define how CSF1- and IL34-Mϕs respectively influence the skin repair process, we wounded frogs as above and at 3 dpw subcutaneously injected them near the sites of injury with recombinant (r)IL34, rCSF1, or a recombinant control (rctrl). Dorsal skin wounds of juvenile frogs becomes re-epithelialized within 24–48 hours (51). This tissue is only several cells thick and is prone to tearing if manipulated. Thus, we waited 3 days post wounding before performing nearby subcutaneous injections. Csf1r+ cell quantification via RNA-ISH indicated that cytokine treatment did not significantly increase the amount of Mϕs in the wounds (Supplementary Figure 1). We concluded that the following results reflect consequences of changing the polarization of Mϕs already present within skin wounds rather than recruitment of additional Mϕs.

Because Mϕ recruitment to skin wounds peaked at 7 dpw (Figure 2B), we chose to focus our subsequent studies within and relatively soon after this timepoint. To this end, we next examined the wound histology of cytokine-administered animals, noting infiltration of leukocyte types therein at 7 and 14 dpw (Figures 4A–C’, Supplementary Figures 2A–C). At 7 dpw and compared to rctrl- and rIL34-treated wounds, the rCSF1-administered wounds possessed greater leukocyte infiltration, marked by greater proportions of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and Mϕs (Figures 4B, B’). At 14 dpw, we did not observe discernable differences in the histology of control and cytokine-treated wounds (Supplementary Figures 2A–C).

Figure 4. Analyses of histology and neutrophil infiltration of rCSF1- and rIL34-administered wounds. Histology, 7 days post wounding (dpw) of (A, A′) rctrl-, (B, B′) rCSF1-, and (C, C′) rIL34-administered wounds (cytokines administered 3 dpw). Inset panels (A′–C′) depict higher magnification. Lymphocytes (black arrows), macrophages (red arrows), and neutrophils (blue arrows) are indicated. (D–F) RNA in situ hybridization for mpo (magenta), visualizing neutrophil localization 7 days post wounding (dpw) in (D) rctrl-, (E) rCSF1- and (F) rIL34-administered wounds (cytokines administered 3 dpw). Open arrowheads mark wound edges. (G) Quantification of mpo⁺ cell density (cells/cm²) at 7 and 14 dpw. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3-7 biological replicates per group). Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; *p < 0.05. (H) Expression analysis of inflammatory response genes at 7 dpw across treatments. Boxplots represent medians with interquartile range; letters indicate statistically distinct groups (p < 0.05, pairwise Wilcox test).

To corroborate the elevated neutrophil infiltration observed in rCSF1-administered wounds, we performed RNA-ISH analyses of myeloperoxidase (mpo), which is a defining neutrophil marker (14, 52, 53). Indeed, rCSF1-treated wounds had significantly higher proportions of mpo+ cells at 7 dpw, compared to both control and rIL34-treated animals (Figures 4D–G). With respect to rctrl- and rCSF1-treatment groups, the rIL34-treated wounds exhibited greater numbers of mpo+ cells at 14 dpw (Figure 4G, Supplementary Figures 2D–F), albeit not significantly so.

We next examined immune gene expression profiles of these cytokine-treated frog wounds during the repair process. The rCSF1-administered wounds possessed markedly greater pro-inflammatory gene expression at 7 dpw (Figure 4H). Amongst these was colony-stimulating factor 3 receptor (csf3r.l), a neutrophil growth factor receptor (54) and marker of frog neutrophils (55–57). Concurrently, the rCSF1-treated wounds exhibited greater expression of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8/interleukin-8 (cxcl8) genes, the products of which facilitate neutrophil recruitment (58, 59) as well as hallmark proinflammatory cytokines and receptors (il1b.l/s, il17ra, il17re.l/s; Figure 4H). By contrast, at 7 dpw, rIL34-treated wounds showed significantly decreased expression of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 beta (il1β.l/s) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (tnf.l). At 7 dpw, IL34-treated wounds also displayed reduced expression of receptors for interleukin-17, -18, and -23 (il17ra, il17re.l, il18.2.s, il18rap.l, il23r), neutrophil-associated genes csf3r.l and cxcl8.l/s, and the chemokine C-C motif chemokine ligand 4 (ccl4.l; Figure 4H). At 14 dpw, rCSF1-treated wounds continued to express greater levels of csf3r and cxcl8.s as well as the chemokine receptor, cxcr4 when compared to controls (Supplementary Figure 2G). At this time, rIL34-administered wounds now also possessed greater mRNA levels of the cxcr4 as well as several chemokine ligand genes (ccl4.l/s, cxcl8.l/s, cxcl8a.2.l, cxcl13.l; Supplementary Figure 2G), perhaps explaining the greater numbers of neutrophils seen in this treatment group at this time (Figure 4G, Supplementary Figures 2D, F). Taken together, these findings suggest that CSF1 and IL34 respectively promote and diminish wound inflammation, with rIL34 administration possibly having compensatory effects or changes to wound repair kinetics seen by 14 dpw.

3.4 Proportions of CSF1- and IL34-Mϕs in wounded skin influence myofibroblast activation, collagen deposition, and remodeling

To further understand the roles of CSF1- and IL34-Mϕs in wound repair, we characterized the kinetics of frog wound fibroblast activation. The activation of fibroblasts to the myofibroblast phenotype (acta2+) is a hallmark of wound healing across vertebrates (60), with a previous study (10) and the present work indicating that this is also true of X. laevis skin wounds. Compared to rctrl- and rCSF1-administered animals, frogs injected with rIL34 exhibited significantly more acta2+ cells in their wounds at 7 and 14 dpw (Figures 5A–D, Supplementary Figures 3A–D), suggesting that IL34-Mϕs may be more important than CSF1-Mϕs in X. laevis skin wound myofibroblast activation. Notably, skin glands in and outside wounded skin also stained positive for acta2 (Figures 5A–C, Supplementary Figures 3A–C), possibly owing to inherent roles for myofibroblasts in these structures.

Figure 5. Myofibroblast accumulation in rCSF1- and rIL34-administered wounds. (A–C′) Immunofluorescence staining of (red) acta2 and (blue) DAPI in (A, A′) rctrl, (B, B′) rCSF1, and (C, C′) rIL34 wounds at 7 dpw (cytokines administered 3 dpw). Open arrowheads mark wound edges, boxed regions indicate sections of higher magnification in (A′–C′). (D) Quantification of acta2⁺ area (% total wound region, excluding gland-adjacent expression). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 4-7 biological replicates per group). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; *p < 0.05. Images were created using fluorescent microscopy and inverting uniformly in ImageJ.

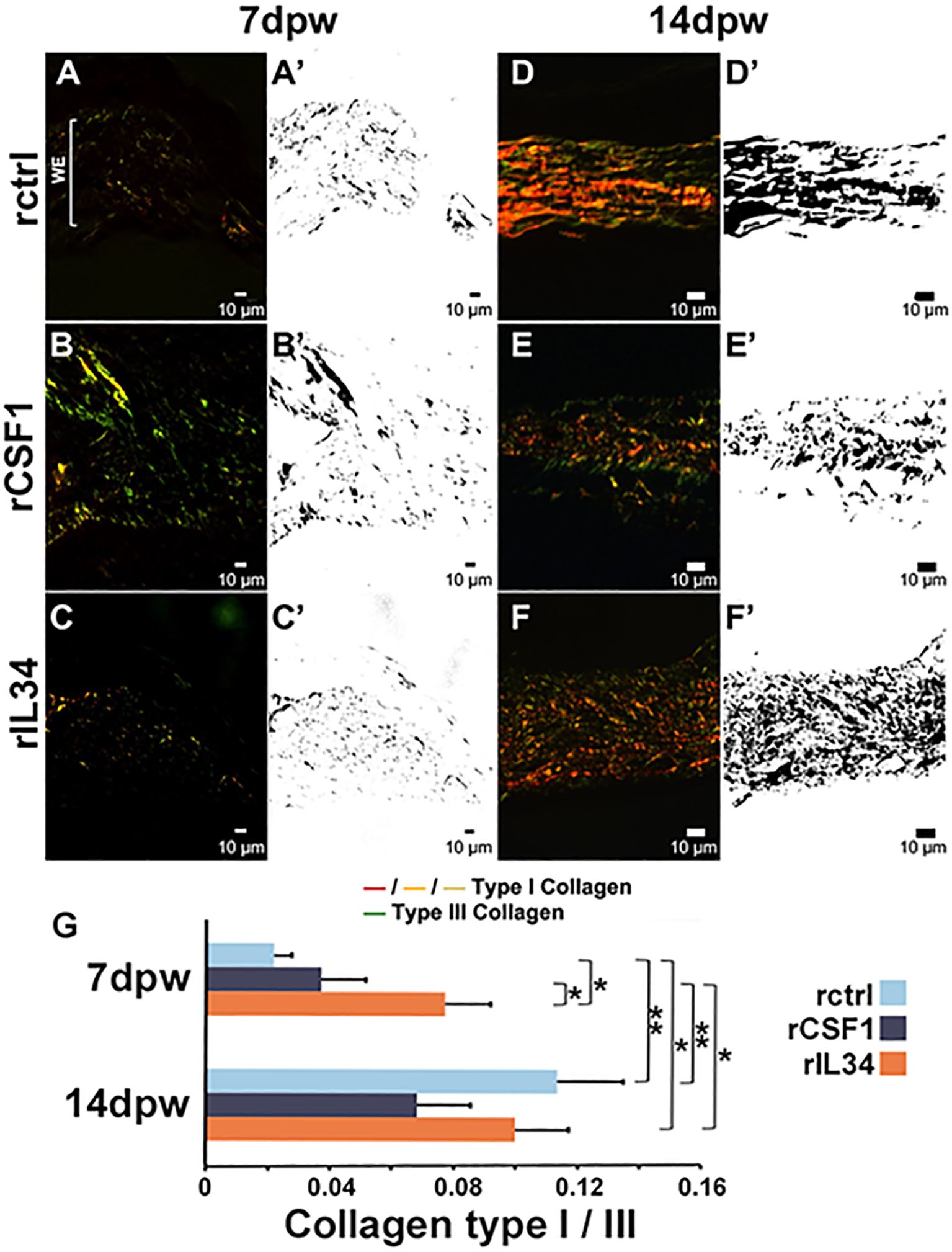

Myofibroblast-mediated wound repair is marked by collagen deposition and remodeling (4, 9, 61) while mammalian skin is predominated by collagen types I and III (43, 62, 63). In turn, analysis of the collagen I/III ratio is frequently used to assess scarring and fibrosis in mammalian wound healing studies (64). Because myofibroblast activation drives this process, we next examined collagen deposition in rCSF1- and rIL34-skewed skin wounds during repair (Figures 6A–F’). When we examined the ratios of collagen I to collagen III deposition in the healing skin, we found that at 7 dpw the rIL34-administered animals possessed significantly higher collagen I/III ratios compared to control and rCSF1-treated animals (p < 0.05, Figures 6A–C, G), suggesting that IL34-Mϕs promote type I collagen deposition, presumably at least in part via myofibroblast activation. While the collagen I/III ratios were less prominent in rCSF1-administered wounds than in rIL34-treated wounds at 7 dpw (Figure 6G), those tissues displayed greater overall amounts of both collagen types, but especially type III (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Collagen I and III deposition in rCSF1- and rIL34-administered wounds. (A–C′) Picrosirius red (PSR) staining of (A, A′) rctrl, (B, B′) rCSF1, and (C, C′) rIL34-administered wounds at 7 days post wound (dpw; cytokines administered 3 dpw), imaged with polarized light microscopy. Collagen I (red/orange/yellow) and collagen III (green) birefringence is shown; corresponding binary masks are in A′–C′. (D–F′) PSR staining of (D, D′) rctrl, (E, E′) rCSF1, and (F, F′) rIL34 wounds at 14 dpw with corresponding masks (D′–F′). (G) Quantification of collagen I/III ratios at 7 and 14 dpw. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 7-12 biological replicates per group). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

By 14 dpw, all treatment groups had greater collagen deposition, with control and rIL34-treated wounds exhibiting greater (not significantly so) collagen I/III ratios than rCSF1-administered wounds (Figures 6D–G). Moreover, at 14 dpw the patterns of the remodeled collagen were markedly different across these treatment groups (Figures 6D–F’). The control wounds displayed mostly parallel collagen fibers across the wound beds by 14 dpw, consistent with what is seen at this stage in other vertebrates with superior regenerative capacities (65) (Figures 6D, D’). The rCSF1-treated wounds exhibited dense, fragmented collagen with irregular orientation, indicative of disorganized deposition/remodeling and reminiscent of what is typical of pro-inflammatory milieu (65, 66) (Figures 6E, E’). In contrast, rIL34-treated wounds showed dense collagen deposition with fibers that were more interwoven and heterogeneous in orientation, suggesting accelerated but remodeling-competent matrix assembly (Figures 6F, F’).

Our transcriptomic analysis supported the above observations. For example, rIL34-treated wounds exhibited significantly greater expression of collagen type I alpha 2 chain (col1a2.l/s) at 7 dpw (Figure 7A), consistent with their greater I/III ratios (Figure 6G). In line with greater myofibroblast activation (Figure 5), rIL34-treated wounds also had greater expression of secreted protein acidic and cysteine rich (sparc.s; Figure 7A), the product of which contributes to myofibroblast differentiation and regulation of collagen-remodeling (67). The gene encoding transforming growth factor beta-induced protein (tgfbi), a downstream effector of TGFβ1, involved in collagen fiber organization and myofibroblast contractility (68) was likewise upregulated in rIL34-treated wounds, as was tgfbr2.s (Figure 7A), the ligand for which is prominently involved in wound repair and fibrosis (69). Moreover, fibroblast growth factor-9 (FGF9) is known to inhibit TGFβ1-induced myofibroblast differentiation (70), and thus our observation that fgf9.s expression was decreased in the rIL34-treatment group, also supports greater fibroblast activation at 7 dpw in this group (Figure 7A). Reduced platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) signaling is a hallmark of scarless healing (71) and so the decreased expression of several PDGF-related genes (pdgfa.l, pdgfc.s, and pdgfrb.s) in rIL34-treated wounds likewise corroborates the possible role of IL34 in regenerative repair (Figure 7A). Elevated connective tissue growth factor (ccn2) and endothelin-1 (edn1.l) levels have been respectively linked to fibrosis (72) and vascular dysfunction (73), so it is notable that these transcripts were elevated in rCSF1-treated wounds but diminished in rIL34-administered wounds (Figure 7A). By 14 dpw, the rIL34-treated wound had significantly diminished expression of collagen genes, col1a2.s/l whereas the rCSF1-treated wounds possessed marginally increased col1a2.s/l expression (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. Gene expression in rCSF1- and rIL34-administered wounds. (A) RNA-seq expression analysis of ECM- and fibrosis-associated genes at 7 and 14 dpw across treatments. (B) RNA-seq expression analysis of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their regulators (TIMPs) at 7 and 14 dpw across treatments. Boxplots show median, interquartile range, and statistical groupings, letters denote significance; p < 0.05.

Extracellular matrix remodeling by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their regulation by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) is a key feature of wound repair (48, 74) and this process is integral to collagen remodeling and amphibian regeneration (75–77). Our results showed that at 7 dpw, rCSF1-treated wounds possessed elevated expression of genes encoding pro-fibrotic MMPs (mmp13.s, mmp28.l) (75, 76, 78) as well as the pro-collagen I remodeling mmp14.l (66, 79) (Figure 7B). The rIL34-treated wounds showed significantly increased expression of mmp9 and mmp14, the former known to be important in regeneration (79, 80) (Figure 7B). The rIL34-treated wounds also had significantly reduced expression of the pro-fibrotic mmp24 (81) and upregulated expression of timp2.l, a prominent MMP inhibitor (69) (Figure 7B). Both treatment groups exhibited elevated levels of mmp1.s when compared to controls, albeit more modestly so in rIL34-treated wounds (Figure 7B). At 14 dpw, CSF1-enriched wounds maintained high expression of mmp7 and mmp13, which are known to be upregulated during inflammation (72). Conversely, rIL34-enriched wounds expressed greater levels of mmp1 and mmp25, the latter being associated with angiogenesis (79, 82) (Figure 7B). These findings demonstrate that rCSF1 and rIL34-polarization of regenerating wounds culminated in distinct MMP signatures despite comparable collagen I/III ratios at 14 dpw.

4 Discussion

By two months post injury, juvenile X. laevis skin wounds are entirely regenerated to a point of being indistinguishable from the surrounding tissue, both histologically and macroscopically (83). At this time the afflicted skin possesses fully reformed epidermal and dermal layers, along with regenerated glands, which are albeit smaller and fewer in number than those in the surrounding unwounded skin (83). In contrast, adult X. laevis exhibit fibrotic repair of their skin wounds, characterized by irregularly organized collagen fibers (10). Much remains to be discerned about the immune determinants of juvenile versus adult X. laevis wound repair capacities. The results presented here indicate that X. laevis Mϕ subsets are intimately involved in the juvenile X. laevis skin wound repair.

Mϕs are rapidly recruited to X. laevis juvenile skin wounds and remain within the regenerating tissues for up to three weeks. This is reminiscent of the mammalian phases of wound healing, wherein Mϕs are essential for early inflammation, debris clearance, and signaling to downstream effectors like fibroblasts (12). In turn, our expression analysis of csf1 and il34, as well as our Mϕ polarization studies indicate that CSF1- and IL34-Mϕs play disparate and temporally regulated roles in wound repair. Altering the relative proportions of CSF1- and IL34-Mϕs in the frog wounds resulted in profound consequences to the immune status of those wounds. Whereas rIL34-treatment manifested in reduced gene expression of key pro-inflammatory mediators, rCSF1 stimulation increased the expression of several hallmark inflammatory genes alongside increased neutrophil infiltration into the wound beds. Accordingly, we postulate that CSF1-Mϕs predominate the initial inflammatory responses, whereas IL34-Mϕs likely promote wound repair through fibroblast activation, altered collagen deposition, and advanced remodeling later in the repair process. It is of note that in mammals, IL34 facilitates steady-state maintenance of epidermal skin Langerhans cells (LCs) (30) whereas CSF1 contributes to LC production during skin inflammatory responses (33). In turn, our past studies indicate that the X. laevis CSF1-Mϕs may be more inflammatory than IL34-Mϕs in certain contexts (45, 84), while there is a growing body of literature indicating that in mammals, IL34 is produced in tolerogenic contexts by T regulatory (Treg) cells (85). Future studies employing repeated injections or sustained formulated release of rCSF1 and rIL34 will grant added perspectives on these respective Mϕ subsets and on the utility of such reagents to therapeutic applications.

In mammals, cutaneous injury triggers the rapid recruitment of circulating monocytes into wound beds, which extravasate from blood vessels, enter the wound area, and differentiate into inflammatory Mϕs or monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MoDCs) (86). These recruited cells are reinforced by locally expanding skin-resident dermal Mϕs and LCs (58, 87), which also contribute to wound surveillance and orchestration of repair processes. Resident tissue Mϕ and DC precursors are seeded into tissues like skin during embryonic development and self-renew therein, independently of blood-derived monocytes (88). This includes mammalian LC precursors, which repopulate LCs at steady-state (88). Though it is not clear from our analysis where the Mϕs involved in amphibian wound healing originate, we speculate that these effector Mϕs comprise of both tissue-resident and recruited, hematopoietic progenitors-derived populations. recruited. Considering the number of Mϕs decreases with frog wound repair, concurrent with changes in il34 and csf1 gene expression, we anticipate that some of these cells leave the wounds or undergo apoptosis. However, other Mϕs likely remain, shifting from CSF1-polarized to IL34-polarized subtypes, possibly resembling the shift from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory Mϕ phenotypes seen in healing mammalian wounds (89). It will be interesting to see the extent to which this CSF1/IL34 wound repair dichotomy is evolutionarily conserved.

Fibroblasts are critical to wound repair (60, 90, 91), differentiating into myofibroblasts upon activation and upregulating their expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin (acta2/acta2) (4, 17, 90). Fibroblasts are thought to migrate into wounds from surrounding tissues (92), though it is not clear in either frogs or mammals, what proportion of these cells come from neighboring healthy skin versus other sources. Myofibroblasts synthesize and deposit collagen types I and III (90), causing wound contraction and closure (5, 64) as well as scar formation and fibrosis in mammalian wound healing (4, 34). Mammalian scar tissue formation reflects higher collagen I/III ratios (i.e. higher levels of collagen I), with normal and hypertrophic scars possessing a 6:1 ratio and keloid scars showing a staggering 17:1 ratio (64). During mammalian wound healing, thin collagen III fibers are deposited first, followed by the thicker collagen I fibers, as scars form (90). In contrast, regenerating amphibians actively suppress type I collagen deposition early on during wound repair, while type III collagen is deposited in low amounts as loose fibers (93). As amphibian regeneration progresses, collagen I is deposited considerably more slowly than in mammals, preventing fibrosis and scar formation. We anticipate that the greater type I collagen deposition and increases in acta2+ myofibroblasts seen in rIL34-treated wounds reflect the roles of IL34-Mϕs in later, reparative phase of the repair process. Consistent with this notion, while rIL34-administration increased col1a gene expression, it also resulted in reduced inflammatory gene expression, suggesting a transition towards repair. Conversely, rCSF1-treatment elevated pro-inflammatory transcripts and total collagen deposition. This interpretation is further supported by the divergent expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and a regulator, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 (TIMP2), as these are the principal mediators of collagen turnover. Cytokine treatments produced distinct MMP profiles that paralleled the elicited collagen deposition phenotypes. At 7 dpw, rCSF1-treated wounds possessed elevated MMP13 and MMP28, which are respectively associated with granulation and fibrosis (81, 94). Both cytokine treatment groups upregulated the pro-fibrotic MMP1 (76), but only rIL34-treated wounds had increased TIMP2 expression. We anticipate that the high MMP1, MMP13 and MMP28 expression in the rCSF1-treated wounds is more likely to result in fibrosis and scar formation. Conversely, modestly increased MMP1 together with high expression of the pro-regenerative MMP14, MMP25 and TIMP2 concurrent with reduced MMP24, seen in rIL34-treated wounds, likely results in more controlled collagen remodeling and is less likely to lead to scar formation. At 14 dpw, in addition to MMP13, rCSF1-treated wounds also exhibited elevated expression of MMP7, which has been associated with delayed healing (87). The rIL34-administered wounds possessed elevated MMP1, but also MMP25 expression, reminiscent of MMP profiles associated with localized collagen trimming (79, 95, 96). It will be interesting to learn the precise kinetics with which disparate Mϕ subsets control deposition and remodeling of extracellular matrices.

TGFβ signaling is a hallmark of X. laevis regeneration (97), and rIL34-treated wounds possessed greater expression of multiple TGFβ downstream effectors including col1a2, sparc, tgfbi, and tgfbr2l. The increase in tgfbr2l.s is especially compelling as TGFβR2 is the prominent receptor in TGFβ signaling (97). SPARC and TGFβI, both upregulated in rIL34-treated wounds, are key regulators of collagen organization and fibroblast contractility (98). Their increased expression, alongside more robust myofibroblast recruitment/activation, likely contributes to the higher collagen I deposition seen in rIL34-treated wounds. These observations support our notion that IL34-Mϕs promote wound healing following the inflammatory phase of the repair response. Pertinently, studies looking at tail and limb regeneration in X. laevis have indicated that early-phase treatment of wounds with anti-inflammatory agents enhance regenerative capacities (99).

It is speculated that mucosal tissue possesses traits that enable regeneration, which is why oral mucosa in mammals can heal with little to no scar formation (87). Mammalian oral mucosa wound repair leads to increased release of chemokine CCL5, a robust early influx of neutrophils and Mϕs, and higher levels of IL6, IL1β, and TNFα (87). This presents an interesting comparison, as these overlap with the expression profiles seen in the wounds of both the control and rCSF1-treated animals. Even though frog skin serves as both a skin and a mucosal barrier, our previous work suggests that other frog skin-resident immune cells, at least in some contexts, more closely resemble mammalian skin-resident over their mucosal counterparts (100). The thus far characterized frog inflammatory response elicited during wounding also closely resemble those seen in human wounds (101).

While our polarization studies indicate potentially disparate roles for CSF1- and IL34-Mϕs during regenerative skin repair, much remains to be learned about how these respective subsets confer changes to aspects of wound repair such as recruitment and activation of distinct fibroblast subsets as well as deposition and remodeling of extracellular matrix components. We did not see increased Mϕ infiltration of wounds treated with rCSF1 or rIL34, suggesting that the observed effects are due to polarization rather than expansion of the respective Mϕ subset. Unfortunately, our attempts to deplete these Mϕ types within wounds by administering purified polyclonal antibodies against frog rCSF1 and rIL34 were not successful. While we believe our present findings to be compelling, we also feel that further resolution of when and how CSF1- and IL34-Mϕs contribute to scarless wound repair needs to be achieved through future studies using Mϕ-subset-specific depletion or knock-out approaches.

The present findings represent a window into the roles of frog Mϕ subsets in scarless wound repair. However, much remains to be discerned regarding the coordinated and kinetic involvement of these and other myeloid populations in frog skin regeneration and how these cells and processes relate to those taking place in mammals. We believe that studies akin to those reported here will bridge that gap in our understanding of the determinants of successful wound repair.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE306422, GSE306422.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by GWU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee regulations (Approval number A2023-044). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

CG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Software, Validation. KH: Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BA: Conceptualization, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. EC: Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. EJ: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AD: Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. LG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by a National Science Foundation (NSF-IOS: 1749427) grant to LG as well as and support from the Noblis-Sponsored Research (NSR) Program.

Acknowledgments

CG thanks the Wilbur V. Harlan Trust for summer support. We thank the reviewers, who’s insightful comments and suggestions helped to improve this manuscript. The authors would also like to thank the GWU Nanofabrication and Imaging Center for the use of its instruments and the guidance from its members during the acquisition of this data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1713361/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Ferguson MWJ and O’Kane S. Scar–free healing: from embryonic mechanisms to adult therapeutic intervention. In: Brockes JP and Martin P, editors. Philos trans R soc lond B biol sci United Kingdom: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: biological Sciences, vol. 359 (2004). p. 839–50.

2. Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, and Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. (2008) 453:314–21. doi: 10.1038/nature07039

3. Stocum DL. Tissue restoration through regenerative biology and medicine. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol (2004) 176:III-VIII, 1–101. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-18928-9

4. Abe G, Hayashi T, Yoshida K, Yoshida T, Kudoh H, Sakamoto J, et al. Insights regarding skin regeneration in non-amniote vertebrates: Skin regeneration without scar formation and potential step-up to a higher level of regeneration. Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2020) 100:109–21. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2019.11.014

5. Larouche J, Sheoran S, Maruyama K, and Martino MM. Immune regulation of skin wound healing: mechanisms and novel therapeutic targets. Adv Wound Care. (2018) 7:209–31. doi: 10.1089/wound.2017.0761

6. Robert J and Ohta Y. Comparative and developmental study of the immune system in Xenopus. Dev Dyn. (2009) 238:1249–70. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21891

7. Brockes JP. Amphibian limb regeneration: rebuilding a complex structure. Science. (1997) 276:81–7. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.81

8. Kawasumi A, Sagawa N, Hayashi S, Yokoyama H, and Tamura K. Wound healing in mammals and amphibians: toward limb regeneration in mammals. In: Heber-Katz E and Stocum DL, editors. New perspectives in regeneration, vol. 367 . Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg (2012). p. 33–49. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. doi: 10.1007/82_2012_305

9. Franchini A. Adaptive immunity and skin wound healing in amphibian adults. Open Life Sci. (2019) 14:420–6. doi: 10.1515/biol-2019-0047

10. Bertolotti E, Malagoli D, and Franchini A. Skin wound healing in different aged Xenopus laevis. J Morphol. (2013) 274:956–64. doi: 10.1002/jmor.20155

11. Kloc M ed. Macrophages: origin, functions and biointervention. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2017). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-54090-0

12. Kim SY and Nair MG. Macrophages in wound healing: activation and plasticity. Immunol Cell Biol. (2019) 97:258–67. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12236

13. Minutti CM, Knipper JA, Allen JE, and Zaiss DMW. Tissue-specific contribution of macrophages to wound healing. Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2017) 61:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.08.006

14. Knipper JA, Willenborg S, Brinckmann J, Bloch W, Maaß T, Wagener R, et al. Interleukin-4 receptor α Signaling in myeloid cells controls collagen fibril assembly in skin repair. Immunity. (2015) 43:803–16. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.09.005

15. Chazaud B. Macrophages: Supportive cells for tissue repair and regeneration. Immunobiology. (2014) 219:172–8. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2013.09.001

16. Krzyszczyk P, Schloss R, Palmer A, and Berthiaume F. The role of macrophages in acute and chronic wound healing and interventions to promote pro-wound healing phenotypes. Front Physiol. (2018) 9:419/full. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00419/full

17. Lucas T, Waisman A, Ranjan R, Roes J, Krieg T, Müller W, et al. Differential roles of macrophages in diverse phases of skin repair. J Immunol. (2010) 184:3964–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903356

18. Godwin JW, Pinto AR, and Rosenthal NA. Macrophages are required for adult salamander limb regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2013) 110:9415–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300290110

19. Zhang MZ, Yao B, Yang S, Jiang L, Wang S, Fan X, et al. CSF-1 signaling mediates recovery from acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest. (2012) 122:4519–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI60363

20. Guiducci C, Vicari AP, Sangaletti S, Trinchieri G, and Colombo MP. Redirecting In vivo Elicited Tumor Infiltrating Macrophages and Dendritic Cells towards Tumor Rejection. Cancer Res. (2005) 65:3437–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4262

21. Saccani A, Schioppa T, Porta C, Biswas SK, Nebuloni M, Vago L, et al. p50 nuclear factor-κB overexpression in tumor-associated macrophages inhibits M1 inflammatory responses and antitumor resistance. Cancer Res. (2006) 66:11432–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1867

22. Stanley ER, Berg KL, Einstein DB, Lee PSW, Pixley FJ, Wang Y, et al. Biology and action of colony-stimulating factor-1. Mol Reprod Dev. (1997) 46:4–10. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199701)46:1<4::AID-MRD2>3.0.CO;2-V

23. Liu H, Leo C, Chen X, Wong BR, Williams LT, Lin H, et al. The mechanism of shared but distinct CSF-1R signaling by the non-homologous cytokines IL-34 and CSF-1. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2012) 1824:938–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.04.012

24. Ma X, Lin WY, Chen Y, Stawicki S, Mukhyala K, Wu Y, et al. Structural basis for the dual recognition of helical cytokines IL-34 and CSF-1 by CSF-1R. Struct Lond Engl. (2012) 20:676–87. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.02.010

25. Lin H, Lee E, Hestir K, Leo C, Huang M, Bosch E, et al. Discovery of a cytokine and its receptor by functional screening of the extracellular proteome. Science. (2008) 320:807–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1154370

26. Baghdadi M, Umeyama Y, Hama N, Kobayashi T, Han N, Wada H, et al. Interleukin-34, a comprehensive review. J Leukoc Biol. (2018) 104:931–51. doi: 10.1002/JLB.MR1117-457R

27. Nandi S, Cioce M, Yeung YG, Nieves E, Tesfa L, Lin H, et al. Receptor-type protein-tyrosine phosphatase ζ Is a functional receptor for interleukin-34. J Biol Chem. (2013) 288:21972–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.442731

28. Segaliny AI, Brion R, Mortier E, Maillasson M, Cherel M, Jacques Y, et al. Syndecan-1 regulates the biological activities of interleukin-34. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Cell Res. (2015) 1853:1010–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.01.023

29. Muñoz-Garcia J, Cochonneau D, Télétchéa S, Moranton E, Lanoe D, Brion R, et al. The twin cytokines interleukin-34 and CSF-1: masterful conductors of macrophage homeostasis. Theranostics. (2021) 11:1568–93. doi: 10.7150/thno.50683

30. Wang Y and Colonna M. Interkeukin-34, a cytokine crucial for the differentiation and maintenance of tissue resident macrophages and Langerhans cells. Eur J Immunol. (2014) 44:1575–81. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344365

31. Greer A, Berrill M, and Wilson P. Five amphibian mortality events associated with ranavirus infection in south central Ontario, Canada. Dis Aquat Organ. (2005) 67:9–14. doi: 10.3354/dao067009

32. Lonardi S, Scutera S, Licini S, Lorenzi L, Cesinaro AM, Gatta LB, et al. CSF1R is required for differentiation and migration of langerhans cells and langerhans cell histiocytosis. Cancer Immunol Res. (2020) 8:829–41. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0232

33. Baud’Huin M, Renault R, Charrier C, Riet A, Moreau A, Brion R, et al. Interleukin-34 is expressed by giant cell tumours of bone and plays a key role in RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. J Pathol. (2010) 221:77–86. doi: 10.1002/path.2684

34. Yamane F, Nishikawa Y, Matsui K, Asakura M, Iwasaki E, Watanabe K, et al. CSF-1 receptor-mediated differentiation of a new type of monocytic cell with B cell-stimulating activity: its selective dependence on IL-34. J Leukoc Biol. (2013) 95:19–31. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0613311

35. Greter M, Lelios I, Pelczar P, Hoeffel G, Price J, Leboeuf M, et al. Stroma-derived interleukin-34 controls the development and maintenance of langerhans cells and the maintenance of microglia. Immunity. (2012) 37:1050–60. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.001

36. Benson TM, Markey GE, Hammer JA, Simerly L, Dzieciatkowska M, Jordan KR, et al. CSF1-dependent macrophage support matrisome and epithelial stress-induced keratin remodeling in Eosinophilic esophagitis. Mucosal Immunol. (2025) 18:105–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mucimm.2024.09.006

37. Wang K, Song B, Zhu Y, Dang J, Wang T, Song Y, et al. Peripheral nerve-derived CSF1 induces BMP2 expression in macrophages to promote nerve regeneration and wound healing. NPJ Regener Med. (2024) 9:35. doi: 10.1038/s41536-024-00379-7

38. Franzè E, Dinallo V, Laudisi F, Di Grazia A, Di Fusco D, Colantoni A, et al. Interleukin-34 stimulates gut fibroblasts to produce collagen synthesis. J Crohns Colitis. (2020) 14:1436–45. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa073

39. Boulakirba S, Pfeifer A, Mhaidly R, Obba S, Goulard M, Schmitt T, et al. IL-34 and CSF-1 display an equivalent macrophage differentiation ability but a different polarization potential. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:256. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18433-4

40. Paquin-Proulx D, Greenspun BC, Kitchen SM, Saraiva Raposo RA, Nixon DF, and Grayfer L. Human interleukin-34-derived macrophages have increased resistance to HIV-1 infection. Cytokine. (2018) 111:272–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.09.006

41. Popovic M, Yaparla A, Paquin-Proulx D, Koubourli DV, Webb R, Firmani M, et al. Colony-stimulating factor-1- and interleukin-34-derived macrophages differ in their susceptibility to Mycobacterium marinum. J Leukoc Biol. (2019) 106:1257–69. doi: 10.1002/JLB.1A0919-147R

42. Nakamichi Y, Udagawa N, and Takahashi N. IL-34 and CSF-1: similarities and differences. J Bone Miner Metab. (2013) 31:486–95. doi: 10.1007/s00774-013-0476-3

43. Merkel JR, DiPaolo BR, Hallock GG, and Rice DC. Type I and type III collagen content of healing wounds in fetal and adult rats. Exp Biol Med. (1988) 187:493–7. doi: 10.3181/00379727-187-42694

44. Yaparla A, Docter-Loeb H, Melnyk MLS, Batheja A, and Grayfer L. The amphibian (Xenopus laevis) colony-stimulating factor-1 and interleukin-34-derived macrophages possess disparate pathogen recognition capacities. Dev Comp Immunol. (2019) 98:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2019.04.011

45. Yaparla A, Popovic M, and Grayfer L. Differentiation-dependent antiviral capacities of amphibian (Xenopus laevis) macrophages. J Biol Chem. (2018) 293:1736–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.794065

46. Grayfer L and Robert J. Divergent antiviral roles of amphibian (Xenopus laevis) macrophages elicited by colony-stimulating factor-1 and interleukin-34. J Leukoc Biol. (2014) 96:1143–53. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4A0614-295R

47. Wang F, Flanagan J, Su N, Wang LC, Bui S, Nielson A, et al. RNAscope. J Mol Diagn. (2012) 14:22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.08.002

48. Rodrigues M, Kosaric N, Bonham CA, and Gurtner GC. Wound healing: A cellular perspective. Physiol Rev. (2019) 99:665–706. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00067.2017

49. Zuroff LR, Torbati T, Hart NJ, Fuchs DT, Sheyn J, Rentsendorj A, et al. Effects of IL-34 on macrophage immunological profile in response to alzheimer’s-related Aβ42 assemblies. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:1449/full. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01449/full

50. Wynn TA and Vannella KM. Macrophages in tissue repair, regeneration, and fibrosis. Immunity. (2016) 44:450–62. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.015

51. Erickson JR and Echeverri K. Learning from regeneration research organisms: The circuitous road to scar free wound healing. Dev Biol. (2018) 433:144–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.09.025

52. Opneja A, Kapoor S, and Stavrou EX. Contribution of platelets, the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems to cutaneous wound healing. Thromb Res. (2019) 179:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.05.001

53. Loria V, Dato I, Graziani F, and Biasucci LM. Myeloperoxidase: a new biomarker of inflammation in ischemic heart disease and acute coronary syndromes. Mediators Inflamm. (2008) 2008:135625. doi: 10.1155/2008/135625

54. Hossainey MRH, Hauser KA, Garvey CN, Kalia N, Garvey JM, and Grayfer L. A perspective into the relationships between amphibian (Xenopus laevis) myeloid cell subsets. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. (2023) 378:20220124. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0124

55. Hauser K, Popovic M, Yaparla A, Koubourli DV, Reeves P, Batheja A, et al. Discovery of granulocyte-lineage cells in the skin of the amphibian Xenopus laevis. In: Lesbarrères D, editor. FACETS Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: FACETS Journal, vol. 5 (2020). p. 571–97.

56. Koubourli DV, Wendel ES, Yaparla A, Ghaul JR, and Grayfer L. Immune roles of amphibian (Xenopus laevis) tadpole granulocytes during Frog Virus 3 ranavirus infections. Dev Comp Immunol. (2017) 72:112–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.02.016

57. Yaparla A, Koubourli DV, Popovic M, and Grayfer L. Exploring the relationships between amphibian (Xenopus laevis) myeloid cell subsets. Dev Comp Immunol. (2020) 113:103798. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2020.103798

58. De Oliveira S, Reyes-Aldasoro CC, Candel S, Renshaw SA, Mulero V, and Calado Â. Cxcl8 (IL-8) mediates neutrophil recruitment and behavior in the zebrafish inflammatory response. J Immunol. (2013) 190:4349–59. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203266

59. Koubourli DV, Yaparla A, Popovic M, and Grayfer L. Amphibian (Xenopus laevis) interleukin-8 (CXCL8): A perspective on the evolutionary divergence of granulocyte chemotaxis. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:2058. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02058

60. Desmouliere A, Darby IA, Laverdet B, and Bonté F. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in wound healing. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. (2014) 301:301–11. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S50046

61. Seifert AW, Monaghan JR, Voss SR, and Maden M. Skin regeneration in adult axolotls: A blueprint for scar-free healing in vertebrates. In: Zhou Z, editor. PLoS ONE San Francisco, CA, US: PLOS One, vol. 7 (2012). p. e32875.

62. Singh D, Rai V, and KAgrawal D. Regulation of collagen I and collagen III in tissue injury and regeneration. Cardiol Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 07.

63. Wynn T. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol. (2008) 214:199–210. doi: 10.1002/path.2277

64. Xue M and Jackson CJ. Extracellular matrix reorganization during wound healing and its impact on abnormal scarring. Adv Wound Care. (2015) 4:119–36. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0485

65. Kashimoto R, Furukawa S, Yamamoto S, Kamei Y, Sakamoto J, Nonaka S, et al. Lattice-patterned collagen fibers and their dynamics in axolotl skin regeneration. iScience. (2022) 25:104524. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104524

66. Do NN and Eming SA. Skin fibrosis: Models and mechanisms. Curr Res Transl Med. (2016) 64:185–93. doi: 10.1016/j.retram.2016.06.003

67. Wong SLI and Sukkar MB. The SPARC protein: an overview of its role in lung cancer and pulmonary fibrosis and its potential role in chronic airways disease. Br J Pharmacol. (2017) 174:3–14. doi: 10.1111/bph.13653

68. Dou F, Liu Q, Lv S, Xu Q, Wang X, Liu S, et al. FN1 and TGFBI are key biomarkers of macrophage immune injury in diabetic kidney disease. Med (Baltimore). (2023) 102:e35794. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000035794

69. Verrecchia F and Mauviel A. Transforming growth factor-β and fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. (2007) 13:3056. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i22.3056

70. Joannes A, Brayer S, Besnard V, Marchal-Sommé J, Jaillet M, Mordant P, et al. FGF9 and FGF18 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis promote survival and migration and inhibit myofibroblast differentiation of human lung fibroblasts in vitro. Am J Physiol-Lung Cell Mol Physiol. (2016) 310:L615–29. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00185.2015

71. Olutoye OO, Yager DR, Cohen IK, and Diegelmann RF. Lower cytokine release by fetal porcine platelets: A possible explanation for reduced inflammation after fetal wounding. J Pediatr Surg. (1996) 31:91–5. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(96)90326-7

72. Jun JI and Lau LF. CCN2 induces cellular senescence in fibroblasts. J Cell Commun Signal. (2017) 11:15–23. doi: 10.1007/s12079-016-0359-1

73. Bohm F and Pernow J. The importance of endothelin-1 for vascular dysfunction in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. (2007) 76:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.06.004

74. Kandhwal M, Behl T, Singh S, Sharma N, Arora S, Bhatia S, et al. Role of matrix metalloproteinase in wound healing. Am J Transl Res. (2022) 14:4391–405.

75. Vinarsky V, Atkinson DL, Stevenson TJ, Keating MT, and Odelberg SJ. Normal newt limb regeneration requires matrix metalloproteinase function. Dev Biol. (2005) 279:86–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.003

76. Chernoff EAG, O’hara CM, Bauerle D, and Bowling M. Matrix metalloproteinase production in regenerating axolotl spinal cord. Wound Repair Regen. (2000) 8:282–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2000.00282.x

77. Brinckerhoff CE and Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: a tail of a frog that became a prince. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2002) 3:207–14. doi: 10.1038/nrm763

78. Toriseva M, Laato M, Carpén O, Ruohonen ST, Savontaus E, Inada M, et al. MMP-13 regulates growth of wound granulation tissue and modulates gene expression signatures involved in inflammation, proteolysis, and cell viability. PloS One. (2012) 7:e42596. Yang CM, editor. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042596

79. Caley MP, Martins VLC, and O’Toole EA. Metalloproteinases and wound healing. Adv Wound Care. (2015) 4:225–34. doi: 10.1089/wound.2014.0581

80. Wynn T and Barron L. Macrophages: master regulators of inflammation and fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis. (2010) 30:245–57. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255354

81. Pardo A. Matrix metalloproteases in aberrant fibrotic tissue remodeling. Proc Am Thorac Soc. (2006) 3:383–8. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-012TK

82. Schevenels G, Cabochette P, America M, Vandenborne A, De Grande L, Guenther S, et al. A brain-specific angiogenic mechanism enabled by tip cell specialization. Nature. (2024) 628:863–71. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07283-6

83. Yokoyama H, Maruoka T, Aruga A, Amano T, Ohgo S, Shiroishi T, et al. Prx-1 expression in xenopus laevis scarless skin-wound healing and its resemblance to epimorphic regeneration. J Invest Dermatol. (2011) 131:2477–85. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.223

84. Yaparla A and Grayfer L. Isolation and culture of amphibian (Xenopus laevis) sub-capsular liver and bone marrow cells. In: Vleminckx K, editor. Xenopus, vol. 1865 . Springer New York, New York, NY (2018). p. 275–81. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8784-9_20

85. Ni B, Zhang D, Zhou H, Zheng M, Wang Z, Tao J, et al. IL-34 attenuates acute T cell-mediated rejection following renal transplantation by upregulating M2 macrophages polarization. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e24028. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24028

86. Koh TJ and DiPietro LA. Inflammation and wound healing: The role of the macrophage. Expert Rev Mol Med. (2011) 13:e23. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411001943

87. Waasdorp M, Krom BP, Bikker FJ, Van Zuijlen PPM, Niessen FB, and Gibbs S. The bigger picture: why oral mucosa heals better than skin. Biomolecules. (2021) 11:1165. doi: 10.3390/biom11081165

88. Epelman S, Lavine KJ, and Randolph GJ. Origin and functions of tissue macrophages. Immunity. (2014) 41:21–35. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.013

89. Ferrante CJ and Leibovich SJ. Regulation of macrophage polarization and wound healing. Adv Wound Care. (2012) 1:10–6. doi: 10.1089/wound.2011.0307

90. Bainbridge P. Wound healing and the role of fibroblasts. J Wound Care. (2013) 22:407–12. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2013.22.8.407

91. Buechler MB, Fu W, and Turley SJ. Fibroblast-macrophage reciprocal interactions in health, fibrosis, and cancer. Immunity. (2021) 54:903–15. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.04.021

92. Otsuka-Yamaguchi R, Kawasumi-Kita A, Kudo N, Izutsu Y, Tamura K, and Yokoyama H. Cells from subcutaneous tissues contribute to scarless skin regeneration in Xenopus laevis froglets: Hypodermis Contributes To Skin Regeneration. Dev Dyn. (2017) 246:585–97. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24520

93. Calve S, Odelberg SJ, and Simon HG. A transitional extracellular matrix instructs cell behavior during muscle regeneration. Dev Biol. (2010) 344:259–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.007

94. Pardo A, Selman M, and Kaminski N. Approaching the degradome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis☆. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. (2008) 40:1141–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.11.020

95. Gifford V and Itoh Y. MT1-MMP-dependent cell migration: proteolytic and non-proteolytic mechanisms. Biochem Soc Trans. (2019) 47:811–26. doi: 10.1042/BST20180363

96. Sohail A, Sun Q, Zhao H, Bernardo MM, Cho JA, and Fridman R. MT4-(MMP17) and MT6-MMP (MMP25), A unique set of membrane-anchored matrix metalloproteinases: properties and expression in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. (2008) 27:289–302. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9129-8

97. Ho DM and Whitman M. TGF-β signaling is required for multiple processes during Xenopus tail regeneration. Dev Biol. (2008) 315:203–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.031

98. Francki A, McClure TD, Brekken RA, Motamed K, Murri C, Wang T, et al. SPARC regulates TGF-beta1-dependent signaling in primary glomerular mesangial cells. J Cell Biochem. (2004) 91:915–25. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20008

99. King MW, Neff AW, and Mescher AL. The developing xenopus limb as a model for studies on the balance between inflammation and regeneration. Anat Rec. (2012) 295:1552–61. doi: 10.1002/ar.22443

100. Yaparla A, Popovic M, Hauser KA, Rollins-Smith LA, and Grayfer L. Amphibian (Xenopus laevis) Macrophage Subsets Vary in Their Responses to the Chytrid Fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. J Fungi. (2025) 11:311. doi: 10.3390/jof11040311

Keywords: wound repair, regeneration, macrophage, interleukin-34, colony stimulating factor-1

Citation: Garvey Griffith CN, Hauser KA, Abramson B, Chapkin ER, Jones EJ, Duttargi AN and Grayfer L (2025) The contribution of amphibian macrophage subsets to scarless regeneration of skin wounds. Front. Immunol. 16:1713361. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1713361

Received: 25 September 2025; Accepted: 11 November 2025; Revised: 05 November 2025;

Published: 11 December 2025.

Edited by:

Sabyasachi Das, Emory University, United StatesReviewed by:

Mengmeng Zhao, Foshan University, ChinaFrancisco Fontenla-Iglesias, Emory University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Garvey Griffith, Hauser, Abramson, Chapkin, Jones, Duttargi and Grayfer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Leon Grayfer, bGVvbl9ncmF5ZmVyQGd3dS5lZHU=

Christina N. Garvey Griffith1

Christina N. Garvey Griffith1 Kelsey A. Hauser

Kelsey A. Hauser Bradley Abramson

Bradley Abramson Leon Grayfer

Leon Grayfer