Abstract

Introduction:

Mycoplasma phocimorsus is increasingly recognized as an emerging human pathogen, despite its primary association with marine mammals. It has recently been identified as a causative agent of bloodstream infections and sepsis, a major cause of mortality among hospitalized patients. To date, no approved vaccine is available against M. phocimorsus, underscoring the urgent need for preventive strategies.

Methods:

The current study was aimed at employing immunoinformatic approaches to design a vaccine based on multiple epitopes derived from the six core proteomic datasets of representative M. phocimorsus strains.

Results:

By subtractive genomics, we retrieved 3,576 nonredundant proteins from M. phocimorsus proteomes following only one putative immunoglobulin-blocking virulence outer membrane protein conserved in six strains. The epitopes derived from the putative immunoglobulin-blocking virulence protein exhibited promising features such as strong binding affinity, lack of allergenicity, nontoxic properties, high antigenicity scores, and excellent solubility. Moreover, these epitopes include nine linear B cell epitopes, eight MHC class I epitopes, and five MHC class II epitopes. In addition, adjuvants and linker molecules were successfully merged into a chimeric vaccine with significant immunogenicity and stimulation of both adaptive and innate immune responses. The promising potential of the selected vaccine candidates was further validated through their favorable physico-chemical characteristics, strong interaction with TLR-4, and stable performance in molecular dynamics simulations.

Discussion:

These results suggest that the putative immunoglobulin-blocking outer membrane virulence protein could effectively participate in activating the primary innate immune response, thereby serving as a strong foundation for subsequent adaptive immune activation. The proposed vaccine provides substantial basis for developing effective preventive and therapeutic measures against the zoonotic M. phocimorsus, whose association with sepsis, soft tissue, and respiratory infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals emphasizes the crucial need for vaccine development.

1 Introduction

Bloodstream infection (BSI) is a significant global public health challenge with high mortality rates. Prompt and effective treatment is crucial, as delays in therapy can severely impact patient outcomes (1). BSI can complicate the progression of many severe community acquired infectious diseases. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli are responsible for more than 70% of all BSIs (2, 3). Pseudomonas aeruginosa accounts for up to 5% of community-onset bloodstream infections, predominantly affecting patients with severe underlying health conditions and recent exposure to healthcare settings (4). Similarly, the incidence of BSIs caused by community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) has shown signs of stabilizing in recent years, not only in the United States but also in the majority of other endemic regions, after a marked increase during the early 2000s (5, 6). Additionally, the number of BSIs caused by Enterobacterales that produce extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) is slowly increasing because these pathogens are very common in the community. The incidence of ESBL-producing isolates in K. pneumoniae and E. coli bloodstream infections resulting from urinary tract infections currently surpasses 5%, with some locations reporting levels as high as 20%, comparable to total bloodstream infection rates (7, 8).

In the context of M. phocimorsus, bloodstream infections are a potential concern, particularly because of its emerging zoonotic role. Although humans and animals coexist in a symbiotic relationship, animals can also serve as reservoirs of zoonotic pathogens, posing significant health risks to humans through the transmission of infectious diseases (9). M. phocimorsus is increasingly recognized as an emerging human pathogen, despite its primary association with marine mammals. M. phocimorsus can infect humans, especially those who have close contact with marine mammals, such as veterinarians, marine biologists, zookeepers, and workers in rehabilitation centers (10). Marine mammals, such as harbor seals, often carry Mycoplasma species. During the late 1970 s and early 1980 s, M. Phocidae, M. phocacerebrale, and M. phocarhinis were first isolated from harbor seals in New England, USA, following an epizootic pneumonia outbreak (11–13). Recently, scientists identified a new species of Mycoplasma called M. phocimorsus, which was isolated from Scandinavian patients who had septic arthritis or seal arthritis after coming into contact with seals (14). Treatment is challenging due to antibiotic resistance (13, 14). Moreover, a recent case reported a woman who developed tendinous panaritium following a cat scratch, from which M. phocimorsus was identified, suggesting the possibility of transmission through non-traditional animal hosts (15).

Vaccination is crucial for public health, controlling germ outbreaks and reducing mortality rates. Current vaccines are not universally used and require ongoing development and an understanding of immune response mechanisms (16–18). Pangenome sequencing analyses offer comprehensive insights into the antigenic repertoire of the target pathogen, while high-throughput approaches facilitate the identification of potential antigenic candidates (19). Advancements in genome sequencing technologies and biomedical computing sciences have enabled the development of numerous computational and statistical tools and specialized databases to analyze, predict, and annotate various aspects of vaccinology (20). The development of a vaccine against M. phocimorsus is particularly warranted over that against other pathogens for several compelling reasons such as the increasedpotential for zoonotic transmission, the inability of humans to develop immunity to M. phocimorsus due to limited exposure in the general population and the ability of the pathogen to cause life-threatening bloodstream infections, septicemia, and organ failure (21).

We employed immunoinformatics and simulation approaches using five representative strains to identify potential vaccine targets against M. phocimorsus. Following subtractive genomics, we identified a putative immunoglobulin-blocking virulence protein as a potential vaccine candidate with highly antigenic characteristics, and met the criteria of physico-chemical, structural, allergenicity, and antigenicity features, which were further confirmed by docking and molecular dynamics simulation.

2 Materials and methods

Figure 1 shows a simplified illustration of the chimeric vaccine design and analysis using an immunoinformatic method.

Figure 1

Schematic presentation of the subtractive genomics and reverse vaccinology approaches for potential vaccine development.

2.1 Obtaining proteome data and identifying nonredundant proteins

Six completely sequenced genomes of M. phocimorsus (M6620, M6447, M6879, M6642, M5725, and M6921) were retrieved from the NCBI database (Table 1) to identify their core proteome (13). The bacterial pangenome analysis (BPGA) tool, a high-speed and robust tool specifically designed for the comprehensive pan-genome analysis of bacterial species, was used for this analysis. BPGA effectively categorizes genes into core, accessory, and unique gene pools, providing critical insights into genetic conservation and variability within and across bacterial genomes. Determining the core proteome is important for choosing proteins or epitopes that are conserved and could be used to develop cross-protective vaccines (22).

Table 1

| Species | Sequencing depth | Contigs | Size | GC content | CDS | Isolation country | Host name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. phocimorsus strain M6447 | 91.0x | 12 | 744321 | 25.10906 | 626 | Finland | Homo sapiens |

| M. phocimorsus strain M6620 | 118.0x | 51 | 772409 | 25.17734 | 675 | Denmark | Homo sapiens |

| M. phocimorsus strain M6879 | 110.0x | 12 | 745732 | 25.09816 | 628 | Norway | Homo sapiens |

| M. phocimorsus strain M6921 | 140.0x | 50 | 758898 | 24.96554 | 662 | Sweden | Homo sapiens |

| M. phocimorsus strain M6642 | 126.0x | 34 | 752889 | 25.11087 | 641 | Denmark | Homo sapiens |

| M. phocimorsus strain M5725 | 94.0x | 28 | 755408 | 25.17183 | 641 | Denmark | Homo sapiens |

List and features of the genomics data utilized in this study.

Moreover, by focusing on the core proteome, we aimed to overcome the antigen variability that is common in Mycoplasma species and increase the chances of obtaining broad-spectrum protection. The complete proteomes of the six M. phocimorsus strains were obtained from the Universal Protein Resource Knowledgebase (UniProtKB), followed by redundant protein elimination via the CD-HIT suite (23). The criterion for sequence identity was set at 80%, and the remaining parameters were maintained at their default values. A cut off of 80% in CD-HIT influences the selection of nonredundant proteins by clustering sequences that share 80% or more sequence identity into the same group. BLASTp was performed against the human proteome using a list of nonredundant proteins to eliminate proteins that are similar to those identified in humans (24). A bit score cut off of 100, an E-value threshold of 10-3, and a minimum sequence identity of ≤30% were set as a criterion.

2.2 Prediction of essential proteins and their subcellular localization

Essential proteins were identified using the Database of Essential Genes (DEG) (25), where M. pneumoniae used as the reference strain and by using BLASTn algorithm. Essential genes are identified using unique DEG identification numbers, reference numbers, functions, and sequences, and are stored and processed via MySQL as the database management system. The identification process targeted the host non-homologous list of proteins to filter essential proteins. A stringent selection criterion was built, setting a minimum identity threshold of ≥30% and a bit score of 100, to ensure the presence of sequences that are not similar to human proteins. Moreover, nonhomologous sequences were further accurately chosen for subsequent analysis to alleviate potential cross-reactivity. By utilizing PSORTb (26) and CELLO (27) nonhomologous proteins can be further categorized into cytoplasmic and outer membrane (OM) proteins.

2.3 Prioritization of antigenic proteins and epitope mapping

The host immune system identifies a molecule known as an antigen, which triggers the immune response (28). The VaxiJen v2.0 server was employed to predict the potential antigenic properties of the selected proteins (29) by setting the cut off to >0.5. We employed AllerTOP v2.1 to assess the allergenicity of the OM protein. To develop an epitope-based vaccine, it is very important that the chosen epitopes can cause a strong and specific immune response (30). OM protein sequences were used to predict the immunogenic epitope via the online IEDB analysis tool (31, 32). VaxiJen v2.0 server, ToxinPred2 (33), and AllergenFP (34) were employed to examine all the potential epitopes along with their respective antigenicity, toxicity, and allergenicity. Only epitopes identified as antigenic, non-toxic, non-allergenic were selected for subsequent analysis.

2.4 Vaccine construct design and structure prediction

Linkers significantly contribute to the design of multiepitope vaccines by maintaining structural integrity and enhancing the immunogenicity of epitopes (35). By utilizing different linkers such as GPGPG, highly promising epitopes can be joined. Furthermore, the EAAAK linker was employed to attach the adjuvant, thereby improving the overall efficacy of the vaccine construct. The His-tag, comprising six histidine residues, was subsequently attached to the construct’s C-terminus as previously reported (36). ProtParam (37) performs calculations on the basis of amino acid one-letter codes (A-Z) and ignores non amino acid symbols or average hydropathy scores. PSIPRED web servers (31), which retrieve the protein’s secondary structure providing information on alpha-helices, beta-strands, and coils, were utilized to envisage the physico-chemical attributes, and the secondary structure of the vaccine was subsequently improved by using the GalaxRefine server (38). Both before and after refinement, Z score and Ramachandran plots were used to check the quality of the vaccine model and its structure with PROCHECK and ProSA-web (LaskowskiMacArthur and Thornton; 39).

2.5 Molecular docking analysis

Many biological molecules depend on the interaction of proteins for function. To estimate the molecular interactions or affinities between these molecules, analyzing the complex structures that form between them is crucial (40). Toll-like receptors (TLRs), regarded as recognition receptors, largely depend on the recognition of infections. There are ten TLR-encoding genes (41) and among them, TLR-4 was selected to dock with the vaccine construct since it is a useful bacterial-sensing TLR (42). The key interaction between the vaccine model and TLR-4, an innate immune receptor, was examined using the ClusPro 2.0 protein-protein docking server. This particular tool is known for its remarkable efficiency, such as not only providing unusual customization choices, but also rotating the ligand 70,000 times to find the position with the lowest RMSD (43). To ensure that the TLR-4 structure was ready for docking, ligand and oligosaccharide molecules were removed following energy minimization. The ClusPro web server rigid-body docks two proteins through billions of different conformations. The cores of the largest clusters are used as possible models of the complex based on low-energy docked structures. The study revealed the crystal structure of TLR-4, which was obtained from the PDB with the ID 2z64. Protein-protein interactions were examined using the software program RING 3.0 (44).

2.6 Molecular dynamics simulations of vaccine constructs

Desmond software facilitated 100-nanosecond molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, enabling a thorough investigation of receptor and ligand complex dynamics by docking studies. This static technique provides a precise image of molecule binding within the protein’s active site (45). We used MD simulations to study the dynamic characteristics of complexes, applying Newton’s classical equation of motion. This approach provides a comprehensive understanding of receptor-ligand systems, allowing for realistic predictions and insights into dynamic interactions in biological settings (46). We extensively utilized Maestro’s protein preparation wizard for optimization and structural refinement. Subsequent systems were meticulously crafted using the System Builder tool. The OPLS_2005 force field and incorporated the TIP3P (transferable intermolecular potential with 3 points orthorhombic box solvent model was employed for simulation. To simulate physiological conditions, 0.15 M sodium chloride was added and counterions were introduced to neutralize the system. The simulations were performed using default parameters to ensure consistency with normal physiological conditions. Specifically, the NPT ensemble was employed, maintaining a pressure of 1 atm and a temperature of 310 K. We relaxed the models before the simulation to establish a stable starting configuration. The simulation trajectories were saved after every 100 ps intervals to ensure a comprehensive analysis. Stability was further assessed by continuously monitoring the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the ligand and protein over time (16).

2.7 Normal mode analysis of the vaccine construct

Protein-protein complex stability is typically assessed via normal mode analysis (NMA), a standard procedure in computational research (47–49). This assessment comprises analyzing the dynamics of proteins and contrasting their behavior with their usual behavior (47) and the iMODS server is a potential tool for this specific purpose (50), as it provides valuable insights into the intrinsic motions of a variety of proteins (51). It computes several parameters, such as B-factors, eigenvalues, covariance, and deformability, to describe the stability and dynamics of the protein (52). Eigenvalues signify the primary chain deformability. This feature is directly related to the energy required to initiate such deformations. Covariance offers information about the coordinated motion of various protein elements by assisting in the identification of protein structure associated movements (53, 54). Elevated B-factors indicate enhanced flexibility and movement. These values are crucial for determining whether the complex performs its intended function and exhibits the expected behavior, particularly in the context of vaccines or other biomedical applications (55, 56).

2.8 The vaccine construct, in silico, cloning and codon optimization

Once cloned and inserted into an appropriate vector, the in silico cloning process ensures that a specific host will express the vaccine construct. To achieve successful cloning, the optimization and vaccine construct insertion into the expression vector were carried out. The Java codon adaptation tool (JCat) was used for the back-translation of vaccine sequences into cDNA to amplify the engineered vaccine. This specific tool plays an essential role in the determination of the codon adaptation index (CAI), the DNA sequence, and the GC content, which are crucial for optimizing the nucleotide sequence (57, 58). Furthermore, SnapGene, a sequence analysis and molecular cloning software built by Insightful Science, was employed. With the help of SnapGene, biologists may easily see, examine, modify, and share data on molecular biology sequences and processes (59).

2.9 Immune response simulation

The C-ImmSim platform was used to assess the potential immunological response of the designed vaccine. This process involved the use of a position-specific scoring matrix, with all existing options configured to their default settings. This study simulated the following parameters: a) a vaccine devoid of LPS, b) three vaccine doses were administered at intervals of 1, 84, and 168 days to elicit an effective and enduring immune response, and c) the simulation volume and steps were set to 10 and 1100, respectively. All other parameters remained constant (58).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Retrieval of the core proteome and prioritization of vaccine candidates

Six well-known representative and pathogenic strains of M. phocimorsus from various countries were selected for vaccine design (Table 1), and 3,576 core proteins were retrieved by proteomics analysis. CD-HIT clustering at a 90% threshold yielded 829 nonredundant proteins. Owing to their substantial contribution to the essential functions and pathways of pathogens, unique and non-redundant proteins are promising targets for vaccine design (60, 61).

3.2 Non-homologues and essential protein prediction

Homologous proteins share similarities due to their evolutionary origin; therefore, eliminating human homologous proteins from the bacterial proteome is crucial to prevent potential interference (62). A BLASTp analysis identified 192 nonhomologous proteins to the human proteome, reducing the risk of autoimmune responses and improving the safety of the profile for further investigation (63). Essential proteins are vital for the sustainability of cellular functions and constitute a core set of proteins that are crucial for life support (63). BLASTp analysis revealed 170 proteins as essential proteins. These essential proteins appear to have the ability to modulate important processes such as pathogenicity, nutrient absorption, and virulence.

3.3 Assessment of subcellular localization and physico-chemical properties

We retained the essential proteins identified as OM for further analysis, a crucial step in assessing their suitability for vaccine design. Two proteins, the C1 family peptidase and the putative immunoglobulin-blocking virulence protein, were identified as OM via the online tools CELLO v. 2.5 and PSORTb v.3 (Table 2) and were considered suitable for subsequent assessment as potential vaccine candidates. OM proteins are chosen because of their exposure to the host’s immune system and their antigenic sequences, which trigger strong immune responses (60). Among these two proteins, the putative immunoglobulin-blocking virulence protein with a molecular weight of 60701.75 Da, which contains 540 amino acids, has an isoelectric point (pI) of 9.15 because its pH is greater than neutral at 7.0. This protein resembles positively charged proteins and has an instability index of 37.15 indicating nucleoprotein stability. Additionally, the protein has high thermostability as evidenced by its aliphatic index of 79.26. The ability of the putative immunoglobulin-blocking virulence protein to meaningfully contribute to infection and replication within host cells is well established, and this protein is also used in vaccine design (64).

Table 2

| Accession no. | Protein name | Sequence | VaxiJen score | Antigenicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPI0024BF7784 | C1 family peptidase | MKKRIAAIYAFLGLVSLSGASMHYHSNKYVFHESVYDPRTMTLNNYLTKVKHQGKDGICWAYSTTAVIESNILKNKLAIDPLNLDLSEKNLAYKTLNRLTNEDVLHNSDFDNYTNNNWLNEGSRTIFAGIASLQWNKLKRESENWQTALDLNDYKVTDYISLNHLKENWKQNVKTAIKAYGAVSISFDISNIYKKLYYNPNELSANVKFPHAATIVGWNDNIEANKFGHKTKTNGAWIVKNSWGDKFGEGGYFYLSYEALIQDLFTLNVVKGDEYTSNYYYDGGYKDMYENQETAHQKATVSFWAKNSLPTLKEKLKAVNVGIFGDDNEVEIKIYKNNNNVTPNSLELGQLVHTQRQHFIHGGLRTIILDNPIYLEPNENFSIVAQILNPKGYSAIRFSKESNSQSDFSYIEENGKWVSSQKHLDGAVARIKAFVVTEKVQNQEESNDLKYAKVILKGKYYHQYNEKVDEELITVMYKDKKLELNKDYTLQYTTEIDENIFKHSKASVGYTKVKINGTGTYTGNNFIFLDVKKANKNSYK IKLEENWKMLSNKGIYYGLNRIEIEYIGPNKHLFNNNKVTLNIHKIDPNKPKEEPIIIKNEDKTWNSLFSALSKFGQIIVSFFSFW | 0.4216 | ANTIGEN |

| UPI0024BFD15D | putative immunoglobulin-blocking virulence protein | MKRKNRIILFITSFSVLPIATTTGYFIYKHFLNDNKTHIFESNDNKLQNNARQQNSNKIYIADINFKENIPKLPPRKEPLPIEIPNSNKTINILENKLTPFIPKKEKEKLQRITKVPDLIIKPSEIPTPKPNPKPASPTPAPIPTPPTPKPAPIPVPAPSIPSPAPTPEPSPVPSPAPSNENISGGLYEESADSTGGNYGTGNYTGWDKSGNQLEEGKQIKGSEFFKYGVSTKNHEIKIFKLEDKNNKNILGIKNGYSVDADLSNVFGLTTFRSVNELLDNDNKKVIQYRFTNIGAYDDTRNLKLIFESIQENAPQVTLIFKENRIDMLKHLKNKKIKQLDLFSNSDVNSKNWSINPLFLENISNINNNNYANEIGLDTDTNGGKKIVFNSLYFNKEDVDNDNNKFSKINKGLKMVYEDRKNEDFFKGSKKVGYPTELDLSDTDLKSLKGLKFDFTDSRGKKVRLTKLTLNGGNSSNFEINADELNEANFEVLDYDYSGSEIVFKGNVNKISPKNPNDLTDQGKKNLGILRKLAKISA | 0.6144 | ANTIGEN |

Outer membrane proteins identified as potential vaccine candidates.

Additionally, immunoglobulins are thought to affect bacterial infections in a number of ways, including antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, complement activation, phagocytosis, and toxin neutralization (65, 66). The processes by which immunoglobulins influence bacterial infections are believed to include bacterial cell destruction by complement activation, phagocytosis via bacterial opsonization, toxin neutralization, and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (64).The literature reveals that the selection of proteins on the basis of various stringent criteria has potential and is vital for the development of multiepitope based vaccines.

3.4 Epitope prediction and analysis lead to the finalization of potential vaccine candidates

Subsequent analysis of the epitopes was conducted through the IEDB platform. Through the utilization of the B cell epitope prediction tool provided by the IEDB, nine peptides were identified as possible B cell epitopes (Table 3).

Table 3

| Start | End | Peptide | Length | Non-allergenic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34 | 141 | DNKTHIFESNDLNKLQNNARQQNSNKIYIADINFKENIPKLPPRKEPLPIEIPNSNKTINILENKLTPFIPKKEKEKLQRITKVPDLIIKPSEIPTPKPNPKPASPTP | 108 | Yes |

| 147 | 257 | PPTPKPAPIPVPAPSIPSPAPTPEPSPVPSPAPSNENISGGLYEESADSTGGNYGTGNYTGWDKSGNQLEEGKQIKGSEFFKYGVSTKNHEIKIFKLEDKNNKNILGIKNG | 111 | Yes |

| 267 | 271 | VFGLT | 5 | Yes |

| 333 | 334 | HL | 2 | Yes |

| 336 | 340 | NKKIK | 5 | Yes |

| 346 | 355 | SNSDVNSKNW | 10 | Yes |

| 429 | 464 | KGSKKVGYPTELDLSDTDLKSLKGLKFDFTDSRGKK | 36 | Yes |

| 467 | 501 | LNEANFEVLDYDYSG | 15 | Yes |

| 511 | 524 | NKISPKNPNDLTDQ | 14 | Yes |

The table presents the prediction of linear B cell epitopes along with their potential vaccine features.

The elimination of bacteria from the body generally requires the involvement of both humoral and cellular immunity mechanisms. A very important part of initiating humoral immune responses is the interaction between B cell epitopes and antibodies (67). The predicted B cell epitopes were analyzed to evaluate their potential immunogenicity and determine their binding affinities and interaction sites with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II molecules as shown in Figure 2, with a cut off value of 0.5.

Figure 2

(A) Global population coverage of MH class I epitopes. (B) Global population coverage of MH class II epitopes. (C) HLA allele coverage worldwide for T-cell epitope prediction.

B cell epitopes were selected based on several criteria, including their sequence, position, antigenic scores, length, and nonallergenic properties as detailed in Table 3. The antigenic scores ranged from a minimum value of 0.4439 to a maximum of 0.6107. Analysis of antigenicity revealed both the highest and lowest values, with a mean score of 0.7926. It is highly useful for identifying specific regions of a protein that are recognized by antibodies. These regions, known as B cell epitopes, are specific segments of an antigen that can elicit an antibody response, enabling the design of targeted antibodies without requiring the entire protein. Following B cell epitope prediction, 170 potential MHC class I epitopes were predicted on the basis of the stringent selection criterion of an IC value less than 1000 via the IEDB MHC class 1 tool. Eight epitopes were selected for inclusion in the vaccine formulation after 63, which fulfilled the pre-requisite of interacting with at least 10 alleles that were eliminated. As shown in Table 3, these eight epitopes were chosen because of their potential antigenic properties as well as the lack of any poisonous or allergic characteristics.

The utilization of the IEDB Tongaonkar and Kolaskar antigenicity methods resulted in seven MHC class II epitopes which were categorized by their nonallergenic and nontoxic natures (68). Together with their innate antigenicity, the noteworthy Comb scores of the predicted epitopes make them extremely promising choices. In particular, epitopes such as LKSLKGLKFDFTDSR, GLKFDFTDSRGKKVR, DLKSLKGLKFDFTDS, NLKLIFESIQENAPQ, RGKKVRLTKLTLNGG, LKGLKFDFTDSRGKK, RIDMLKHLKNKKIKQ have been recognized as potential binders with alleles such as HLA-DRB4*01:01, HLA-DRB3*01:01, HLA-DRB3*01:01, HLA-DRB1*07:01, HLA-DRB4*01:01, HLA-DRB1*03:01, and HLA-DRB5*01:01 (Table 4).These findings suggest a broad population coverage and highlight the potential of these epitopes to activate CD4+ T-helper cells, which play a pivotal role in coordinating both humoral and cellular immune responses (69). Overall, the identification of these highly antigenic, conserved, and nonallergenic MHC class II epitopes underscores their promise as key components for the design of an effective multiepitope vaccine against M. phocimorsus.

Table 4

| Epitopes | Interacting alleles | Antigenicity | Allergenicity | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APTPEPSPV | HLA-B*51:01 | 0.8684 | NO | NO |

| DNKKVIQYR | HLA-A*68:01 | 0.481 | NO | NO |

| EIVFKGNVNK | HLA-A*30:01 | 0.4079 | NO | NO |

| ELNEANFEV | HLA-A*02:06 | 1.4901 | NO | NO |

| ESIQENAPQV | HLA-A*26:01 | 0.8181 | NO | NO |

| FLNDNKTHI | HLA-B*53:01 | 0.9904 | NO | NO |

| GKQIKGSEFF | HLA-A*23:01 | 0.9031 | NO | NO |

| HLKNKKIKQL | HLA-A*02:03 | 1.0732 | NO | NO |

Predicted MHC class I with their antigenic score and allergenic and toxic properties.

Furthermore, the integration of multiple peptide epitopes that can activate various HLA-restricted T cell specificities, in conjunction with B cell epitopes, establishes the basis of a universal vaccine formulation. This design guarantees a comprehensive immune response by activating both humoral and cellular immunity. T cell epitopes activate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells across diverse HLA haplotypes, fostering strong and enduring immunity, whereas B cell epitopes augment antibody synthesis, facilitating quick pathogen neutralization (70, 71). This integrated method is especially advantageous for addressing genetic heterogeneity within the human population, hence enhancing vaccine efficacy across various populations.

3.5 Population coverage analysis

By employing the IEDB tool, a comprehensive evaluation of global population coverage was conducted for four epitopes, considering MHC class epitopes I and II alleles worldwide. This detailed analysis aims to ensure broad population coverage, supporting the design of a vaccine capable of targeting diverse populations across the globe (72). The study revealed that 92.77% of the global population was covered by MHC class I epitopes and that 49.02% was covered by MHC class II epitopes. These findings indicate that these epitopes could be used to make vaccines, as shown in Figure 2. The shared population coverage was 96.31%. Typically, population coverage above 80% is observed for MHC class I epitopes as the class I alleles (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C) are more conserved and fewer in number, whereas MHC class II epitopes (HLA-DR, -DQ, -DP) are more polymorphic, resulting in lower coverage, usually around 50-60% (73, 74). In terms of relevance to vaccine design and epitope prediction, population coverage reproduces the capacity or likelihood of epitopes binding to MHC molecules across diverse global populations (75). Several factors play roles in the target population for a vaccine, such as the disease’s epidemiology, affected demographic groups, and public health priorities (76). Overall, the highly significant percentage of the global population justifies vaccine design.

3.6 The proposed MEV model

Small peptide linkers were used to link 24 shortlisted epitopes i.e., nine B cell epitopes, eight MHC class I epitopes, and seven MHC class II epitopes. Figure 3 represents the 630 amino acid-based vaccine model in brief MEV (multiepitope vaccine), which was enhanced with an immunogenic adjuvant and extra supporting peptides. An adjuvant used in vaccine design is a protein cholera toxin B subunit, which is used as an adjuvant in universal vaccine formulations and can enhance the immune response against both B cell and T cell epitopes, ensuring broad and long-lasting immunity (77). The cholera toxin B subunit is a powerful mucosal adjuvant that generates mucosal antibody responses and specific immunity (78).

Figure 3

A visual representation of the multi-epitope vaccine construct is depicted through graphics. The components of the construct are linked together using different linkers, namely (1) EAAAK, (2) CPGPG, and (3) AAY. CD8+ epitopes are joined using the AAY linker, CD4+ epitopes are joined using the CPGPG linker, and B-cell epitopes are joined using the EAAAK linker.

It binds strongly to the GM1-ganglisoside receptor, enhancing the immunogenicity of exogenous antigens, enhancing B cell and T cell responses, and decreasing the antigen dose (79). Various linkers were used to combine adjuvants with B cell epitopes in order to trigger an adapted immune response (80). Five components (the adjuvant, EAAAK linker, GPGPG linker, AAY linker, and 6x His tag) were combined to strengthen the structure, provoke a significant immunological reaction, and facilitate its use in further purification tests. The first step was the introduction of a TLR-4 adjuvant with UniProt ID: 2z64. Subsequently, linkers were utilized to separate and combine the B and T cell-specific epitopes within the construct. We added a 6x His-tag to the vaccine sequence (at the C-terminus) to identify and purify the proteins.

3.7 Prediction of the secondary and tertiary structures of the vaccine

The secondary and tertiary structures of proteins are crucial in vaccine design, particularly in protein-based or peptide-based vaccines. The secondary and tertiary structures of the formulated vaccine model included 49.34% helices, 12.57% sheets, and 37.22% loops. The Ramachandran plot specified that 84.2% of the residues of the tertiary structure exist in the most favored region of the refined structure (Supplementary Figure S1). We added a 6x His-tag to the vaccine sequence (at the C-terminus) to identify and purify the proteins. The solubility of our MEV vaccine was assessed via protein-sol, a crucial stage in vaccine biotechnology, as it aids in purification and isolation processes. The vaccine protein construct was soluble, when it was overexpressed in E. coli (predicted scaled solubility: 0.581), thereby ensuring downstream isolation and purification. Both the tertiary and secondary structures of the vaccine model were characterized by PSIPRED web servers, GalaxRefine server, PROCHECK and ProSA-web and its solubility were in line with those reported previously (41, 58).

3.8 Molecular docking studies of the vaccine construct and the TLR-4 receptor

Molecular docking that accurately enables the interaction between a ligand and a target protein such as TLR-4 is enabled by the use of ClusPro. In total, ten models were obtained, among which the first model encoded a virtuous H-bond interaction and a 90.3 favored region as shown in Figure 4. The lowest energy weighted scores are -1383.2 and -1033.0. The H-bond analysis findings revealed that specific residue pairs interacted with each other, including ASP59-LYS109 with a distance of 2.85 Å, SER85-LYS109 with a distance of 3.21 Å, GLU134-THR112 with a distance of 3.09 Å, and GLU134-THR112 with a distance 3.19 Å. Additionally, HIS158-GLU111 interacted with a distance of 3.01 Å, ASP208-ARG106 with a distance of 3.29 Å, ARG233-ASP100 with a distance of 2.65 Å, LYS263-ASP101 with a distance of 2.82 Å, ASP264-THR115 with a distance of 3.27 Å, ASP264-SER103 with a distance of 2.64 Å, ARG337-ASP101 with a distance of 2.70 Å, and ARG337-ASP101 with a distance of 2.80 Å. The use of PDBsum to represent different interactions between the TLR-4 receptor and the vaccine construct can indeed provide valuable insights into the immunogenic potency of the vaccine.

Figure 4

The molecular docking structure of MEV and TLR-4. As illustrated in the figure, “pink” stands for the MEV, and “light purple” stands for the TLR-4 and red color denotes interacting residues.

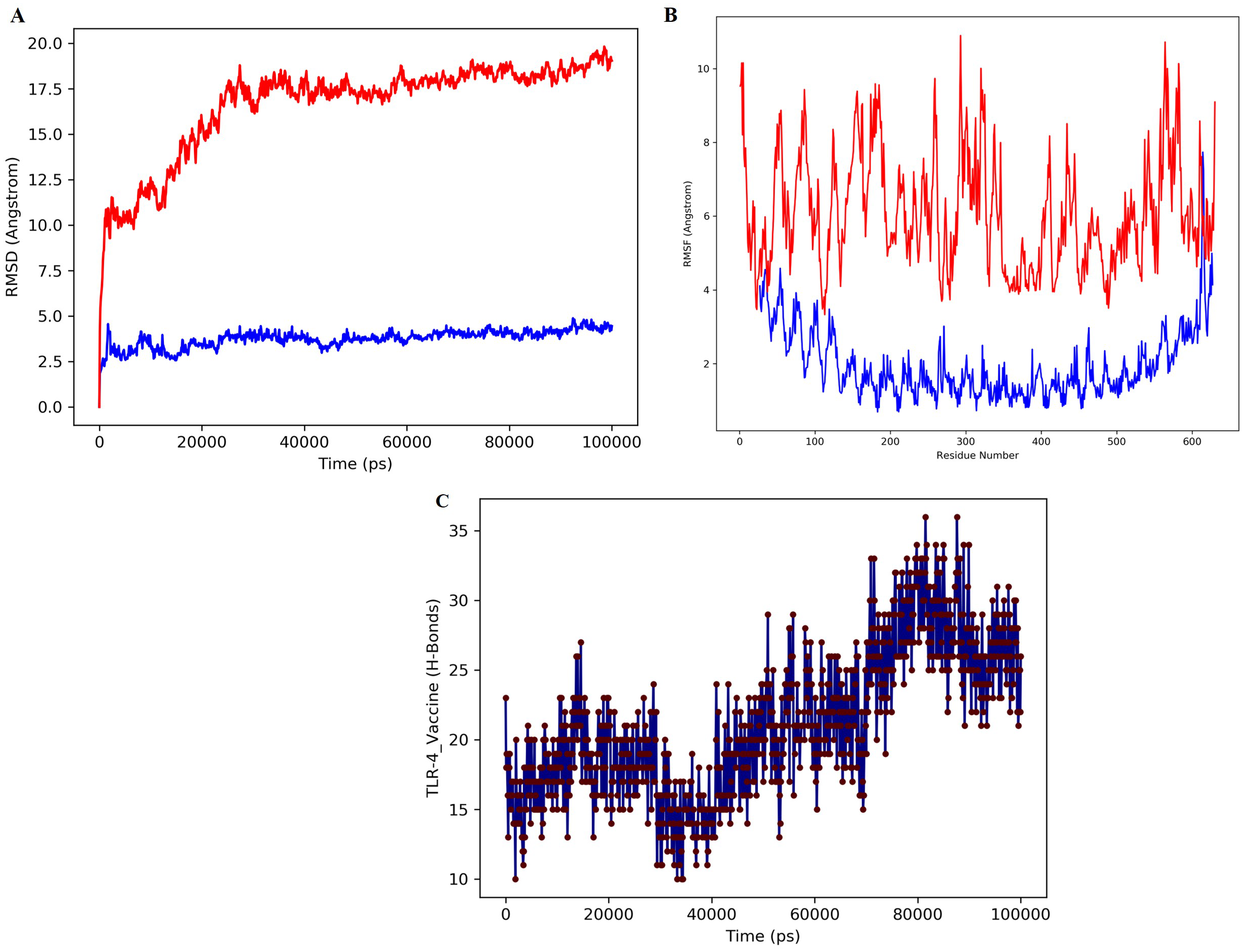

3.9 Vaccine-TLR-4 complex MD simulations

The vaccine-TLR-4 complex was dynamically simulated for 100 ns in the MD simulation to confirm the stability of the complex in a dynamic state. Various analyses, such as RMSD, RMSF, and H bond analyses were carried out for the MD simulations. The analysis of macromolecular structures and dynamics widely utilizes RMSD. Two basic parameters can be understood based on the pattern of the RMSD plot: a) whether the system had reached the equilibrium state, and b) whether the simulation time was sufficient. The RMSD plot of the simulated complex reached a plateau, confirming system equilibration and indicating that the simulation time was sufficient for this protein under the given condition (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the absence of significant fluctuations in the RMSD profile demonstrates the stability of the ligand–receptor complex throughout the simulation.

Figure 5

MD simulation of the docked complex of MEV, (A) The structural stability of the protein over time of the vaccine construct. The blue color represent receptor protein RMSD while red color denotes the design vaccine RMSD. (B) RMSF assesses the flexibility of individual residues of the vaccine construct. The blue color represents the receptor protein RMSF while red color represents the vaccine RMSF. (C) Represent the number of hydrogen bonds formed between the TLR-4 receptor and the vaccine construct.

The fluctuation of each protein residue was analyzed by using RMSF (Figure 5B). Figure B shows the RMSF profile of protein residues during the simulation. The vaccine–TLR-4 complex (blue) displays consistently lower fluctuations approximately 1-3 Å than the unbound structure (red), which reaches 8-10 Å in several flexible regions. This reduction in residue mobility indicates that vaccine binding stabilizes the receptor, particularly in loop and terminal regions. Overall, the RMSF trend confirms that the complex maintains a more rigid and stable conformation throughout the simulation. Intermolecular hydrogen bonds of the vaccine and TLR-4 were observed throughout the time of simulation. Figure 5C represents a significant number of hydrogen bonds. These results indicate that the receptor-ligand complex is compact and that the components are moving closer and forming more stable interactions. Overall, the final construct-TLR-4 complex demonstrated good stability in a solvated dynamic state.

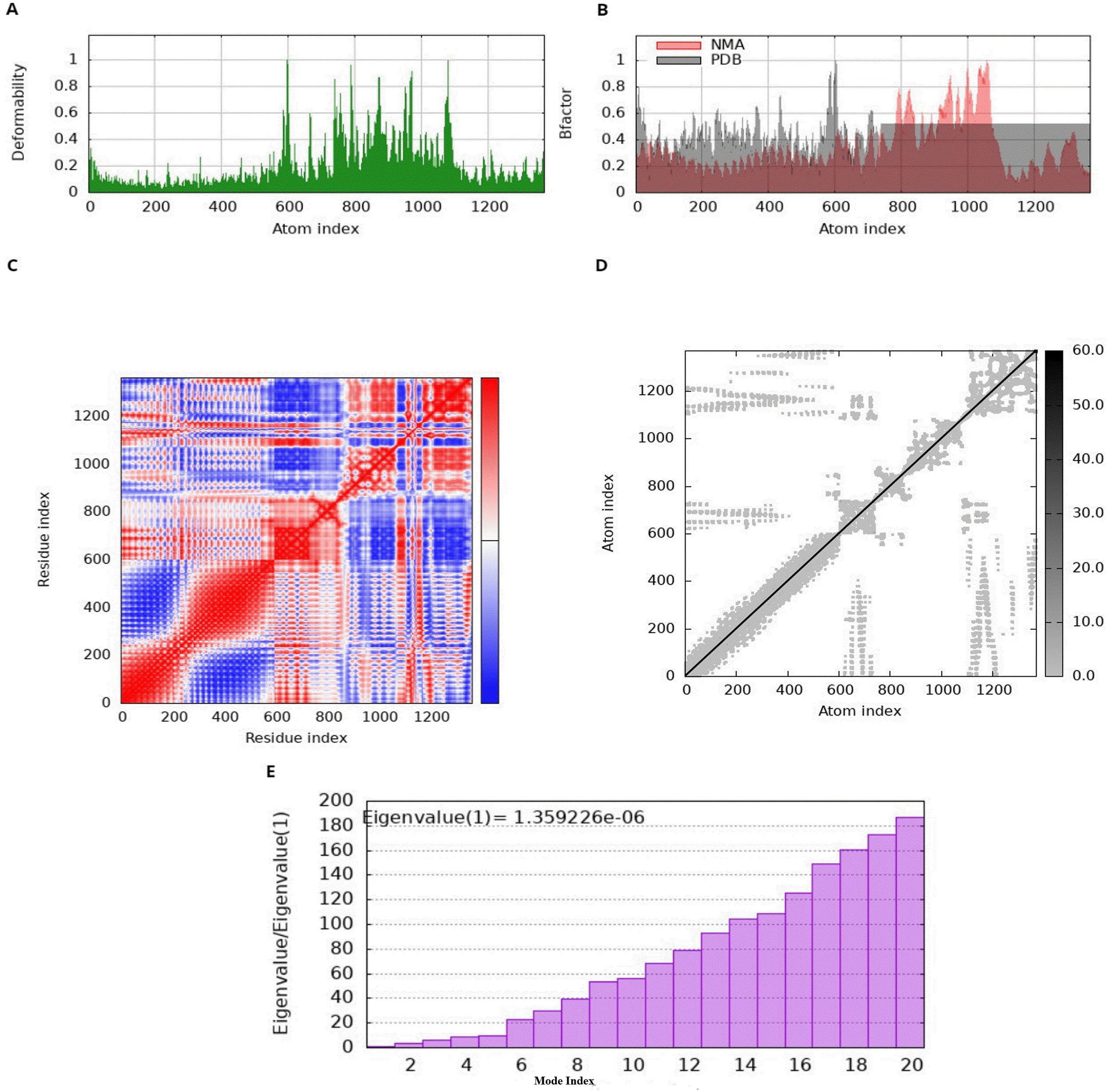

3.10 Normal mode analysis of potential vaccine candidates

The normal mode behavior of the MEV and receptor docked complex was assessed using iMODS, which provides important information about the deformability of particular residues. Deformability, in this context, pertains to the propensity of a protein to undergo conformational changes in its three-dimensional configuration. The graphical illustration of peaks represents areas of high deformability, which shows how easily the protein’s three-dimensional structure can be changed (81). Specifically, the NMA data exhibit higher and more frequent peaks compared to the PDB data., indicating that NMA forecasts higher B-factors. This illustrates, on the other hand, that experimentally calculated B-factor values from the PDB file show less flexibility and mobility than those anticipated by computational NMA simulations. Moreover, the variance graph shows an inverse relationship with the eigenvalue graph, with red indicating individual variance and green representing cumulative variance. The covariance matrix shows the relationships between residues with white, blue, and red colors representing uncorrelated, correlated, and anticorrelated interactions among amino acids respectively (81). The stability of the docked complex is shown by examination of the docking complex, which reveals a strong correlation between residue pairs (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Normal mode analysis of MEV, (A) deformability representing defined feature of M. phocimorsus that plays a critical role in its pathogenicity and immune evasion (B) B-factor; reflecting the atomic mobility or flexibility within a biomolecule (C) covariance index representing the conserved regions and binding interfaces that are less prone to mutation, making them ideal targets for vaccines, (D) elastic network analysis representing the potential protein dynamics and interactions useful for vaccine design. (E) A bar chart of eigenvalue ratios against mode index, with a noted eigenvalue.

3.11 C-ImmSim simulation

Importantly, according to the C-ImmSim immunological tool, the antigen count of the injected antigen peaked count on the fifth day after injection, followed by a slow decline until the fifteenth day. Subsequent to antigen introduction, several antibodies increased (IgM > 600,000; IgG + IgM > 700,000; IgG1 > 500,000; IgG1 + IgG2), and the concentration of the antigen decreased. The data in Figure 7A show a substantial increase in the ratios of the IgM and IgG titers. Additionally, as shown in Figure 7B, there was an obvious increase in B-cell counts following each vaccination session. Interestingly, T cell activity significantly increased after primary and secondary immunization, and this increase was amplified in later stages, as shown in Figures 7C, D. Notably, the impact of the vaccine formulation on innate immune cell populations is shown in Figure 7E. Moreover., the significant increase of T helper cells (TH) cells and the levels of IFN-γ, and IL-2 play pivotal roles in the immune response, as shown in Figure 7F.

Figure 7

Immune simulation profile of the designed vaccine construct (A) Immunoglobulin production shown by black lines after antigen injection; colored lines indicate immune cell classes (B) Changes in B-cell population and memory production (C) Total number of B-lymphocyte cells in plasma per cell (D) Production of helper T-cells (E) Total number of TC cells (F) Displayed elevated rates of cytokines and interleukins.

3.12 Codon optimization and in silico cloning

The codon optimization process was carried out via the JCat program (82), and the final vaccine was cloned. To obtain the highest level of expression in strain K12 of E. coli, the sequence of the vaccine was reverse translated. An average CAI value of 54.8% and a predicted GC content of 0.95 were found when the final vaccine model was assessed. These results show that the vaccine design was successfully expressed in the E. coli system, indicating that the expression procedure was carried out successfully (Supplementary Figure S2). The optimized codon sequence of the finished vaccine was then included in the pET28a (+) vector using the SnapGene tool to create the recombinant plasmid (Figure 8). Typically, codons are commonly assessed using the CAI, a scale ranging from 0 - 1. A CAI value of 0 indicates that synonymous codons are used equally within a gene, whereas a value of 1 reflects a strong preference, utilizing only the best one.

Figure 8

The codons optimized for the gene linked to the vaccine protein were computationally inserted into the pET28a (+) vector within microbial platforms to enhance expression. Integration of the genetic sequence into the cloning vector occurs at the multiple cloning site. The genetic sequence of the tailored vaccine construct (depicted in Magenta), the foundational structure of the vector (depicted in Black), and the kanamycin resistance gene (depicted in Green). Direction and location of gene expression are indicated by colored arrows.

4 Conclusions

The comprehensive analysis and design efforts focused on various representative M. phocimorsus strains have achieved promising results in the pursuit of treatment and preventive measures against this bacterium. Through in-depth genome and proteome analysis, a potential vaccine candidate has been identified, emphasizing the importance of understanding the biology and pathogenic mechanisms of bacteria. In summary, the integrated approach outlined here represents a potential vaccine construct to fight against M. phocimorsus infection, offering promise for effective treatments involving protein-based vaccines and mitigating the impact of this emerging pathogen on human health. Moreover, since the vaccine was designed using core and conserved proteins from six strains of M. phocimorsus, it may offer broader applicability by protecting against infections caused by related Mycoplasma species, particularly those sharing common antigens or conserved virulence factors. Additional experimental validation and clinical studies are essential to confirm the efficiency and safety of the designed vaccine, ultimately paving the way for its clinical application.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

RY: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Methodology. AH: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MI: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. WA: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. LB: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The work is partially supported by Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Zhejiang Province (2026-88).

Acknowledgments

Ongoing Research Funding Programs (ORF-2025-332), King Saud University, Saudi Arabia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1719398/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Shi X Sharma S Chmielewski RA Markovic MJ Vanepps JS Yau ST . Rapid diagnosis of bloodstream infections using a culture-free phenotypic platform. Commun Med (Lond). (2024) 4:77. doi: 10.1038/s43856-024-00487-x

2

Laupland KB Church DL . Population-based epidemiology and microbiology of community-onset bloodstream infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2014) 27:647–64. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00002-14

3

Timsit JF Ruppe E Barbier F Tabah A Bassetti M . Bloodstream infections in critically ill patients: an expert statement. Intensive Care Med. (2020) 46:266–84. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05950-6

4

Martinez Perez-Crespo PM Rojas A Lanz-Garcia JF Retamar-Gentil P Reguera-Iglesias JM Lima-Rodriguez O et al . Pseudomonas aeruginosa community-onset bloodstream infections: characterization, diagnostic predictors, and predictive score development-results from the PRO-BAC cohort. Antibiotics (Basel). (2022) 11:707. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11060707

5

Corona A Bertolini G Lipman J Wilson AP Singer M . Antibiotic use and impact on outcome from bacteraemic critical illness: the BActeraemia Study in Intensive Care (BASIC). J Antimicrob Chemother. (2010) 65:1276–85. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq088

6

Mccarthy KL Paterson DL . Community-acquired Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infection: a classification that should not falsely reassure the clinician. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. (2017) 36:703–11. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2852-0

7

Karanika S Karantanos T Arvanitis M Grigoras C Mylonakis E . Fecal colonization with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing enterobacteriaceae and risk factors among healthy individuals: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Clin Infect Dis. (2016) 63:310–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw283

8

See I Mu Y Albrecht V Karlsson M Dumyati G Hardy DJ et al . Trends in incidence of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections differ by strain type and healthcare exposure, United States 2005-2013. Clin Infect Dis. (2020) 70:19–25. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz158

9

Rahman MT Sobur MA Islam MS Ievy S Hossain MJ El Zowalaty ME et al . Zoonotic diseases: etiology, impact, and control. Microorganisms. (2020) 8:1405. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091405

10

Khan F Engers D Lieberman JA Moudgal V . Disseminated infection with a previously undescribed mycoplasma species from a cat bite. Infect Dis Clin Pract. (2024) 32:1–4. doi: 10.1097/IPC.0000000000001314

11

Giebel J Meier J Binder A Flossdorf J Poveda JB Schmidt R et al . Mycoplasma phocarhinis sp. nov. and Mycoplasma phocacerebrale sp. nov., two new species from harbor seals (Phoca vitulina L.). Int J Syst Bacteriol. (1991) 41:39–44. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-1-39

12

Ruhnke HL Madoff S . Mycoplasma phocidae sp. nov., isolated from harbor seals (Phoca vitulina L.). Int J Syst Bacteriol. (1992) 42:211–4. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-2-211

13

Skafte-Holm A Pedersen TR Frolund M Stegger M Qvortrup K Michaels DL et al . Mycoplasma phocimorsus sp. nov., isolated from Scandinavian patients with seal finger or septic arthritis after contact with seals. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. (2023) 73. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.006163

14

Gomez Rufo D Garcia Sanchez E Garcia Sanchez JE Garcia Moro M . Clinical implications of the genus Mycoplasma. Rev Esp Quimioter. (2021) 34:169–84. doi: 10.37201/req/014.2021

15

Skafte-Holm A Pedersen TR Frølund M Stegger M Hallstrøm S Rasmussen A et al . Detection of Mycoplasma phocimorsus in Woman with Tendinous Panaritium after Cat Scratch, Denmark. Emerg Infect Dis J. (2025) 31:380–2. doi: 10.3201/eid3102.241219

16

Aboshaiqah AE Alonazi WB Patalagsa JG . Patients’ assessment of quality of care in public tertiary hospitals with and without accreditation: comparative cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs. (2016) 72:2750–61. doi: 10.1111/jan.13025

17

Frasca S Jr. Castellanos Gell J Kutish GF Michaels DL Brown DR . Complete sequence and annotation of the mycoplasma phocicerebrale strain 1049(T) genome. Microbiol Resour Announc. (2019) 8:e00514–19. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00514-19

18

Sáfadi MAP . The importance of immunization as a public health instrument. J Pediatr (Rio J. (2023) 99:00. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2022.12.003

19

Anani H Zgheib R Hasni I Raoult D Fournier P-E . Interest of bacterial pangenome analyses in clinical microbiology. Microbial Pathogen. (2020) 149:104275. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104275

20

Salemi A Pourseif MM Omidi Y . Next-generation vaccines and the impacts of state-of-the-art in-silico technologies. Biologicals. (2021) 69:83–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2020.10.002

21

Partin C . Mycoplasma phocimorsus (mῑ-kō-′plaz-mǝ fō-ki-′mȯr-sǝs), panaritium (pan-ǝ-′rish-ē-ǝm). Emerg Infect Dis J. (2025) 31:407. doi: 10.3201/eid3102.241778

22

Fiuza TS Lima JPMS De Souza GA . EpitoCore: mining conserved epitope vaccine candidates in the core proteome of multiple bacteria strains. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:2020. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00816

23

Fu L Niu B Zhu Z Wu S Li W . CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. (2012) 28:3150–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565

24

Boratyn GM Camacho C Cooper PS Coulouris G Fong A Ma N et al . BLAST: a more efficient report with usability improvements. Nucleic Acids Res. (2013) 41:W29–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt282

25

Luo H Lin Y Liu T Lai FL Zhang CT Gao F et al . DEG 15, an update of the Database of Essential Genes that includes built-in analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. (2021) 49:D677–86. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa917

26

Gardy JL Spencer C Wang K Ester M Tusnady GE Simon I et al . PSORT-B: Improving protein subcellular localization prediction for Gram-negative bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. (2003) 31:3613–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg602

27

Yu CS Cheng CW Su WC Chang KC Huang SW Hwang JK et al . CELLO2GO: a web server for protein subCELlular LOcalization prediction with functional gene ontology annotation. PloS One. (2014) 9:e99368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099368

28

Hou Y Chen M Bian Y Zheng X Tong R Sun X . Advanced subunit vaccine delivery technologies: From vaccine cascade obstacles to design strategies. Acta Pharm Sin B. (2023) 13:3321–38. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.01.006

29

Doytchinova IA Flower DR . VaxiJen: a server for prediction of protective antigens, tumour antigens and subunit vaccines. BMC Bioinf. (2007) 8:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-4

30

Dimitrov I Bangov I Flower DR Doytchinova I . AllerTOP v.2–a server for in silico prediction of allergens. J Mol Model. (2014) 20:2278. doi: 10.1007/s00894-014-2278-5

31

Buchan DWA Jones DT . The PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. (2019) 47:W402–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz297

32

Dhanda SK Mahajan S Paul S Yan Z Kim H Jespersen MC et al . IEDB-AR: immune epitope database-analysis resource in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. (2019) 47:W502–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz452

33

Sharma N Naorem LD Jain S Raghava GPS . ToxinPred2: an improved method for predicting toxicity of proteins. Brief Bioinform. (2022) 23:bbac174. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbac174

34

Dimitrov I Naneva L Doytchinova I Bangov I . AllergenFP: allergenicity prediction by descriptor fingerprints. Bioinformatics. (2014) 30:846–51. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt619

35

Arya H . Chapter 8 - Epitope prediction and selection of linkers and adjuvant. In: BhattTKNimeshS, editors. The Design & Development of Novel Drugs and Vaccines. India: Academic Press (2021). p. 97–107.

36

Strauss A Pohlner J Klauser T Meyer TF . C-terminal glycine-histidine tagging of the outer membrane protein Iga beta of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. (1995) 127:249–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07481.x

37

Gasteiger E Gattiker A Hoogland C Ivanyi I Appel RD Bairoch A . ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. (2003) 31:3784–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563

38

Heo L Park H Seok C . GalaxyRefine: Protein structure refinement driven by side-chain repacking. Nucleic Acids Res. (2013) 41:W384–388. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt458

39

Wiederstein M Sippl MJ . ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. (2007) 35:W407–410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290

40

Agu PC Afiukwa CA Orji OU Ezeh EM Ofoke IH Ogbu CO et al . Molecular docking as a tool for the discovery of molecular targets of nutraceuticals in diseases management. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:13398. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-40160-2

41

Asad M Hassan A Wang W Alonazi WB Khan MS Ogunyemi SO et al . An integrated in silico approach for the identification of novel potential drug target and chimeric vaccine against Neisseria meningitides strain 331401 serogroup X by subtractive genomics and reverse vaccinology. Comput Biol Med. (2024) 178:108738. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108738

42

Nosratababadi R Bagheri V Zare-Bidaki M Hakimi H Zainodini N Kazemi Arababadi M . Toll like receptor 4: an important molecule in recognition and induction of appropriate immune responses against Chlamydia infection. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. (2017) 51:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2017.03.004

43

Kozakov D Hall DR Xia B Porter KA Padhorny D Yueh C et al . The ClusPro web server for protein-protein docking. Nat Protoc. (2017) 12:255–78. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.169

44

Clementel D Del Conte A Monzon AM Camagni GF Minervini G Piovesan D et al . RING 3.0: fast generation of probabilistic residue interaction networks from structural ensembles. Nucleic Acids Res. (2022) 50:W651–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac365

45

Bowers KJ Chow E Xu H Dror RO Eastwood MP Gregersen BA et al . Scalable algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations on commodity clusters. In: Proceedings of the 2006 ACM/IEEE conference on Supercomputing. Association for Computing Machinery, Tampa, Florida (2006).

46

Hildebrand PW Rose AS Tiemann JKS . Bringing molecular dynamics simulation data into view. Trends Biochem Sci. (2019) 44:902–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2019.06.004

47

Bahar I Lezon TR Bakan A Shrivastava IH . Normal mode analysis of biomolecular structures: functional mechanisms of membrane proteins. Chem Rev. (2010) 110:1463–97. doi: 10.1021/cr900095e

48

Nair PC Miners JO . Molecular dynamics simulations: from structure function relationships to drug discovery. In Silico Pharmacol. (2014) 2:4. doi: 10.1186/s40203-014-0004-8

49

Liu X Shi D Zhou S Liu H Liu H Yao X . Molecular dynamics simulations and novel drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. (2018) 13:23–37. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2018.1403419

50

Lopez-Blanco JR Aliaga JI Quintana-Orti ES Chacon P . iMODS: internal coordinates normal mode analysis server. Nucleic Acids Res. (2014) 42:W271–276. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku339

51

Siddiqui MQ Badmalia MD Patel TR . Bioinformatic analysis of structure and function of LIM domains of human zyxin family proteins. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:2647. doi: 10.3390/ijms22052647

52

Aiman S Ahmad A Khan AA Alanazi AM Samad A Ali SL et al . Vaccinomics-based next-generation multi-epitope chimeric vaccine models prediction against Leishmania tropica - a hierarchical subtractive proteomics and immunoinformatics approach. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1259612. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1259612

53

Ichiye T Karplus M . Collective motions in proteins: a covariance analysis of atomic fluctuations in molecular dynamics and normal mode simulations. Proteins. (1991) 11:205–17. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110305

54

Bevacqua A Bakshi S Xia Y . Principal component analysis of alpha-helix deformations in transmembrane proteins. PloS One. (2021) 16:e0257318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257318

55

Trent DW Beasley DWC . Development of vaccines for microbial diseases. Vaccinology. (2015), 192–211. doi: 10.1002/9781118638033.ch11

56

Sun Z Liu Q Qu G Feng Y Reetz MT . Utility of B-factors in protein science: interpreting rigidity, flexibility, and internal motion and engineering thermostability. Chem Rev. (2019) 119:1626–65. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00290

57

Rapin N Lund O Bernaschi M Castiglione F . Computational immunology meets bioinformatics: the use of prediction tools for molecular binding in the simulation of the immune system. PloS One. (2010) 5:e9862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009862

58

Hasan A Alonazi WB Ibrahim M Bin L . Immunoinformatics and Reverse Vaccinology Approach for the Identification of Potential Vaccine Candidates against Vandammella animalimors. Microorganisms. (2024) 12:1270. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12071270

59

Samad A Ahammad F Nain Z Alam R Imon RR Hasan M et al . Designing a multi-epitope vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: an immunoinformatics approach. J Biomol Struct Dyn. (2022) 40:14–30. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1792347

60

Kennedy RB Ovsyannikova IG Palese P Poland GA . Current challenges in vaccinology. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:1181. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01181

61

Pisetsky DS . Pathogenesis of autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2023) 19:509–24. doi: 10.1038/s41581-023-00720-1

62

Lavelle DT Pearson WR . Globally, unrelated protein sequences appear random. Bioinformatics. (2010) 26:310–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp660

63

Lopez JA Denkova M Ramanathan S Dale RC Brilot F . Pathogenesis of autoimmune demyelination: from multiple sclerosis to neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease. Clin Transl Immunol. (2021) 10:e1316. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1316

64

Sawa T Kinoshita M Inoue K Ohara J Moriyama K . Immunoglobulin for treating bacterial infections: one more mechanism of action. Antibodies (Basel). (2019) 8:52. doi: 10.20944/preprints201909.0144.v1

65

Warrington R Watson W Kim HL Antonetti FR . An introduction to immunology and immunopathology. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. (2011) 7 Suppl 1:S1. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-7-S1-S1

66

Marshall JS Warrington R Watson W Kim HL . An introduction to immunology and immunopathology. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. (2018) 14:49. doi: 10.1186/s13223-018-0278-1

67

Sanchez-Trincado JL Gomez-Perosanz M Reche PA . Fundamentals and methods for T- and B-cell epitope prediction. J Immunol Res. (2017) 2017:2680160. doi: 10.1155/2017/2680160

68

Kolaskar AS Tongaonkar PC . A semi-empirical method for prediction of antigenic determinants on protein antigens. FEBS Lett. (1990) 276:172–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80535-Q

69

Painter MM Mathew D Goel RR Apostolidis SA Pattekar A Kuthuru O et al . Rapid induction of antigen-specific CD4(+) T cells is associated with coordinated humoral and cellular immunity to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Immunity. (2021) 54:2133–42.e2133. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.08.001

70

Kao DJ Hodges RS . Advantages of a synthetic peptide immunogen over a protein immunogen in the development of an anti-pilus vaccine for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chem Biol Drug Des. (2009) 74:33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00825.x

71

Lim HX Lim J Jazayeri SD Poppema S Poh CL . Development of multi-epitope peptide-based vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Biomed J. (2021) 44:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2020.09.005

72

Giri-Rachman EA Kurnianti AMF Rizarullah Setyadi AH Artarini A Tan MI et al . An immunoinformatics approach in designing high-coverage mRNA multi-epitope vaccine against multivariant SARS-CoV-2. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. (2025) 23:100524. doi: 10.1016/j.jgeb.2025.100524

73

Bui HH Sidney J Dinh K Southwood S Newman MJ Sette A . Predicting population coverage of T-cell epitope-based diagnostics and vaccines. BMC Bioinf. (2006) 7:153. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-153

74

Nielsen M Lund O Buus S Lundegaard C . MHC class II epitope predictive algorithms. Immunology. (2010) 130:319–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03268.x

75

Mochizuki M . Basic concept of immunology. Yan Ke Xue Bao. (1986) 2:240–4. doi: 10.1177/0115426593008004177

76

Majidiani H Pourseif MM Kordi B Sadeghi M-R Najafi A . TgVax452, an epitope-based candidate vaccine targeting Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoite-specific SAG1-related sequence (SRS) proteins: immunoinformatics, structural simulations and experimental evidence-based approaches. BMC Infect Dis. (2024) 24:886. doi: 10.1186/s12879-024-09807-x

77

Facciola A Visalli G Lagana A Di Pietro A . An overview of vaccine adjuvants: current evidence and future perspectives. Vaccines (Basel). (2022) 10:819. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10050819

78

Tepale-Segura A Gajon JA Munoz-Cruz S Castro-Escamilla O Bonifaz LC . The cholera toxin B subunit induces trained immunity in dendritic cells and promotes CD8 T cell antitumor immunity. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1362289. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1362289

79

Hou J Liu Y Hsi J Wang H Tao R Shao Y . Cholera toxin B subunit acts as a potent systemic adjuvant for HIV-1 DNA vaccination intramuscularly in mice. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2014) 10:1274–83. doi: 10.4161/hv.28371

80

Stratmann T . Cholera toxin subunit B as adjuvant–an accelerator in protective immunity and a break in autoimmunity. Vaccines (Basel). (2015) 3:579–96. doi: 10.3390/vaccines3030579

81

Evangelista FMD Van Vliet AHM Lawton SP Betson M . In silico design of a polypeptide as a vaccine candidate against ascariasis. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:3504. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-30445-x

82

Grote A Hiller K Scheer M Munch R Nortemann B Hempel DC et al . JCat: a novel tool to adapt codon usage of a target gene to its potential expression host. Nucleic Acids Res. (2005) 33:W526–531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki376

Summary

Keywords

Mycoplasma phocimorsus , reverse vaccinology, subtractive genomics, B-cell epitopes, drug targets, MD simulation

Citation

Yu R, Hasan A, Ibrahim M, Alonazi WB and Bin L (2025) An integrated immunoinformatic approach to design a novel multiepitope chimeric vaccine against Mycoplasma phocimorsus as a causal agent of bloodstream infections. Front. Immunol. 16:1719398. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1719398

Received

06 October 2025

Revised

08 November 2025

Accepted

17 November 2025

Published

05 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Pitchiah Sivaperumal, Saveetha University, India

Reviewed by

Nazmul Hasan, Jashore University of Science and Technology, Bangladesh

Kashaf Khalid, Helmholtz Zentrum, Germany

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Yu, Hasan, Ibrahim, Alonazi and Bin.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Li Bin, libin0571@zju.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.