Abstract

Neutrophils are the body’s primary responders to infection and injury, yet they also exert diverse effects within tumours through distinct subtypes and mechanisms of action. In light of persistent challenges in clinical oncology, including drug resistance, a research focus on neutrophil biology represents a promising frontier. This review examines neutrophil heterogeneity in cancer by exploring their developmental stages, tumour-specific mechanisms influencing progression, and established classification systems. It further highlights emerging neutrophil subpopulations identified across specific tumours and disease contexts, offering insights into their dual roles in pathogenesis. By integrating recent findings, this work provides a framework to guide drug development and clinical therapeutics in oncology and related pathologies.

1 Introduction

Neutrophils, also known as polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), are the most abundant type of white blood cells in human circulation and a key component of the innate immune system (1). They play a crucial role in infections, tissue injury, and chronic diseases. In recent years, neutrophil heterogeneity has emerged as a growing research focus, with accumulating evidence showing that neutrophil populations display diverse functional properties under both homeostatic and pathological conditions (2). During neutrophil development, microenvironmental conditions can direct their differentiation into different subsets, challenging the traditional view of neutrophils as a homogeneous population. Owing to their broad and context-specific functions in innate immunity, neutrophils have also opened new perspectives in cancer therapy. Integrating neutrophil heterogeneity into tumour treatment represents a relatively novel research direction. Although promising advances have been achieved, a more precise understanding of how neutrophil heterogeneity specifically influences tumour progression is still needed for clinical translation.

Current research techniques enable relatively accurate classification of neutrophils based on surface-specific molecular structures, such as the human neutrophil antigen (HNA) system. The HNA system comprises polymorphic, neutrophil-specific surface antigens that participate in intercellular recognition and signal transduction. In 1998, the Granulocyte Antigen Working Group of the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT) established a standardised nomenclature for well-defined neutrophil antigens based on their glycoprotein localisation, designating them as “human neutrophil alloantigen” (HNA) to reflect their expression on neutrophils (3). To date, the ISBT Granulocyte Immunobiology Working Party (GIWP) has identified five HNA antigen systems: HNA-1, HNA-2, HNA-3, HNA-4, and HNA-5 (4). Among these, two antigen groups (HNA-1 and HNA-2) are expressed exclusively on neutrophils and are sometimes referred to by their historical names (NA and NB, respectively), as they are truly neutrophil-specific and not shared with other primate cells (5). By contrast, other HNA antigens (e.g., HNA-3) exhibit broader tissue distribution, including expression on lymphocytes, platelets, and pulmonary endothelial cells (6). Nevertheless, due to their clinical relevance in neutrophil biology, these antigens have also been incorporated into the HNA system.

In this context, this article synthesises experimental studies and review literature to clarify neutrophil developmental processes and their cancer-associated heterogeneity in the setting of specific tumours, aiming to provide a consolidated perspective for future research.

2 Developmental stages of neutrophils

2.1 Circulatory system/blood

Neutrophils are derived from granulocyte-macrophage progenitors. Prior research has identified three distinct neutrophil subpopulations within human bone marrow: precursor neutrophils, non-proliferative neutrophils, and mature neutrophils. Neutrophil precursors undergo differentiation into both immature and mature neutrophils (7). Under physiological conditions, the development of neutrophils follows a sequential progression through several stages, including hematopoietic stem cells, multipotent progenitors, common myeloid progenitors, early unipotent neutrophil progenitors, pre-neutrophils, myelocytes, metamyelocytes, band cells, and mature neutrophils, each distinguished by specific surface markers. Within the tumour microenvironment (TME), neutrophils are typically classified into anti-tumour and pro-tumour subtypes (8).

TANs exert profound effects on tumour biology and exhibit multiple subtypes (Figure 1). In healthy individuals, circulating neutrophils exist at different densities, with functional specialisation: low-density neutrophils (LDNs) display antimicrobial activity and lymphocyte suppression, whereas high-density neutrophils (HDNs) exhibit weaker effector functions. These subsets are rarely detected under physiological conditions (12). For decades, neutrophils were considered terminally differentiated cells restricted to antimicrobial defence and inflammatory responses (11, 12). This paradigm has been challenged by evidence demonstrating that LDNs and HDNs exert both tumour-promoting and tumour-suppressing effects. Using discontinuous density gradient separation, neutrophils were isolated from the high-density granulocyte fraction, whereas low-density (LD) monocytes were obtained from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). This methodology allowed researchers to classify circulating neutrophils into HDNs and LDNs. In cancer, LDNs exhibit both mature and immature morphological phenotypes, although the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. LDNs may also arise from the HD fraction, serving as a source of mature neutrophils. Notably, the spontaneous conversion of HDNs into LDNs has been observed in the circulation of late-stage tumour-bearing mice (13).

Figure 1

Tumour-induced mobilisation of neutrophils from haematopoiesis to the tumour microenvironment. Haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) serve as progenitors of neutrophils during early development. HSCs give rise to granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs), which proliferate into hNePs before differentiating into mature neutrophils. These mature neutrophils reside in the bone marrow for 4–6 days before entering circulation. Their release is regulated by inflammatory chemokine receptors: C-X-C motif chemokine receptor (CXCR)2 promotes neutrophil mobilisation, whereas CXCR4 mediates neutrophil retention. Tumour cells secrete granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), which stimulates the production of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)1 and CXCL2. tumour-released proinflammatory substances like G-CSF and IL-1β signal the bone marrow, causing hematopoietic issues and continuous systemic neutrophil proliferation (9). G-CSF also facilitates mobilisation by downregulating CXCL12 expression in the bone marrow, thereby promoting the egress of immature neutrophils—cells with incomplete immune functions-into the bloodstream. In addition, tumour-derived interleukin-1β (IL-1β) enhances the expansion and development of HSCs within the bone marrow, accelerating neutrophil production and maturation. The mobilisation of neutrophils into circulation by tumour cells is a prerequisite for their infiltration into the TME, where they differentiate into tumour-associated neutrophil (TANs) (10, 11).

Cell surface marker profiling remains the most reliable approach for neutrophil subtyping. In cancer patients, circulating neutrophils include three granulocyte subsets: mature segmented HDNs, mature LDNs, and immature LDNs. Importantly, HDNs and LDNs are not homogeneous populations but represent subtypes defined by specific molecular signatures. Recent research has elucidated the complex roles of neutrophils in cancer, highlighting their involvement in tumour growth and metastasis, maintenance of cancer stem cells, regulation of cell cycle progression, impairment of immune surveillance, and co-modulation of T cell responses (14). These subsets exhibit distinct surface marker profiles and fulfil differential roles in tumour biology (Table 1).

Table 1

| Related molecules | Roles | Molecular mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| ROS, RNS, Proteases | Tumour-promoting | Neutrophils induce epithelial damage and pro-tumourigenic inflammation through ROS/RNS and protease secretion, facilitating epithelial-to-cancer cell transformation (17). |

| TNF, IL-17, CD4+ T cells | Tumour-promoting | Neutrophils are activated by TNF-induced IL-17+CD4+ T lymphocytes. |

| IL-1R | Tumour-promoting | Neutrophils convert senescent cancer cells into proliferative cells via IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra). |

| NE, IRS1, PI3K | Tumour-promoting | NE translocates to cancer cells, degrades IRS1, and activates PI3K signalling to directly stimulate proliferation. |

| ARG1 | Immunosuppression | Arg-1-mediated L-arginine depletion suppresses CD8+ T cell function (18). |

| TGFβ | Immunosuppression | Neutrophils mediate immune suppression through TGFβ signalling. |

| CXCL1/2/5, Hypoxia | Tumour-suppressive | Hypoxia-induced CXCL1/2/5 secretion recruits tumouricidal neutrophils (19). |

| MET, TNF, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) | Tumour-suppressive | Endothelial MET receptor upregulation triggers TNF-dependent iNOS production in neutrophils, inducing cytotoxic effects on cancer cells. |

| BV8, MMP-9, VEGF-A | Pro-angiogenic | Neutrophil-derived BV8 and MMP-9 activate VEGF-A, remodelling ECM and inducing angiogenesis (15). |

| CD11b | Pro-metastatic | CD11b-dependent neutrophil guidance promotes cancer-endothelial cell co-localisation during early metastasis. |

| HMGB1, TLR4, IL-17, NETs, LTB4, iNOS | Dual roles (Promotion/Suppression) | Bidirectional regulation via: • Pro-metastatic: HMGB1-TLR4 signalling, IL-17+ γδT cell activation, NETosis, LTB4 • Antitumour: iNOS-mediated T cell suppression (15) |

2.1.1 LDN

In non-oncological contexts, LDNs were first described in 1986 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis. In 2003, Bennett et al. performed microarray analysis of PBMCs from paediatric SLE patients and identified elevated expression of neutrophil-specific genes. This “granulocyte signature” was attributed to increased LDNs within the PBMC fraction (20). In the TME, neutrophils exhibit phenotypic plasticity, giving rise to a distinct LDN subpopulation. Tumour-associated LDNs emerge transiently during inflammation and progressively accumulate in malignancies. This subset consists of at least two morphologically different neutrophil populations regulated by discrete immunomodulatory mechanisms. In 4T1 mouse models, circulating neutrophils progressively increased during cancer progression. In healthy mice, HDNs accounted for >95% of total neutrophils. However, tumour growth was accompanied by an increase in LDNs and a proportional decrease in HDNs. Importantly, the rise in LDNs was not explained solely by HDN conversion, since the absolute HDN count remained stable, suggesting that most LDNs arise de novo during disease progression (12). Morphologically, LDNs share similar granularity with HDNs but are markedly larger. Spontaneous conversion of HDNs into LDNs was observed in late-stage tumour-bearing mice, occurring more frequently than the reverse process. This interconversion is mediated by transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) (21). In humans, LDNs are elevated in the blood of breast cancer (BC) patients, particularly those with metastatic disease. Higher LDN prevalence has been associated with poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (22, 23).

2.1.1.1 Subpopulations and functions of LDNs

Mature LDNs originate from the bone marrow and spleen. Two major subpopulations, mature and immature, have been identified, both characterised by lower density in peripheral blood (21). LDNs are not restricted to pathological states and can also appear in healthy adults when peripheral neutrophils undergo activation-induced density changes. Functionally, LDNs foster a tumour-supportive microenvironment by suppressing cytotoxicity against tumour cells and strongly inhibiting cluster of differentiation (CD)8+ T-cell proliferation. They also exhibit a diminished inflammatory profile, with reduced expression of CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL10, C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL) 2, CCL3, C-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5), CXCR2, and cluster of differentiation 62 ligand (CD62L). Compared with HDNs, mature human LDNs display higher levels of activation markers integrin alpha M (CD11b) and CD66b. Three neutrophil subpopulations have been described within the LDN fraction, with notable interindividual variability: CD16+(Fc gamma receptor III)/CD11b+, CD16-/CD11b+, and CD16-/CD11b-. Since CD11b and CD66b localise to secretory vesicles, gelatinase granules, and/or specific granules, their expression intensity likely reflects activation and degranulation states. LDNs exhibit reduced apoptosis, prolonging their lifespan (11). Moreover, HDNs that transition into LDNs acquire immunosuppressive functions. Clinically, elevated circulating LDNs correlate with poor therapeutic response and reduced survival (24). Key Functions of LDNs: Impaired phagocytosis, Reduced oxidative burst, Inhibition of CD8+ T cell proliferation, Prolonged neutrophil survival (11).

Immature LDNs (iLDNs) resemble polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (PMN-MDSCs), although direct classification as PMN-MDSCs remains unproven. In patients with lung or ovarian cancer, two subsets have been identified: CD45high LDNs, which suppress T-cell proliferation and display mature morphology, and CD45low LDNs, which are immature and lack immunosuppressive activity (24). Mature LDNs inhibit immune-mediated tumour clearance and promote metastasis through cytokine and chemoattractant secretion, including CXCL2 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

2.1.2 HDNs

HDNs represent the predominant subset of mature neutrophils and are central to antitumour immunity. Characterised by segmented nuclei and higher density, they are typically isolated from the high-density fraction using gradient centrifugation. HDNs express mature neutrophil markers such as CD66b, CD11b, termed 3-fucosyl-N-acetyl-lactosamine (CD15), and CD16 in humans, or Lymphocyte Antigen 6 Complex, Locus G (Ly6G) in mice (11, 25). CD11b and CD66b also serve as activation markers. Within the TME, HDNs are regulated by TGF-β, Interleukin-8 (IL-8), and G-CSF, which can drive degranulation or dedifferentiation into LDNs. HDN phenotype shifts with tumour stage: in early disease, HDNs exhibit antitumour N1 characteristics, whereas in advanced tumours, TGF-β polarises them into a protumourigenic N2 phenotype, marked by secretion of pro-angiogenic and pro-metastatic factors such as VEGF and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) (11).

2.1.2.1 Role of HDN

HDNs generally function as tumour suppressors with cytotoxic capabilities. They exert antitumour activity through production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (26), release of proteases (e.g., myeloperoxidase [MPO]), and direct contact-mediated tumour cell killing. In early tumour stages, HDNs strongly inhibit tumour cell migration to pre-metastatic niches. Their Fc receptors (e.g., CD16) recognise tumour antigen-antibody complexes, mediating antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), exemplified by the antitumour effect of anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) antibodies in BC (11, 27). A subset of immunostimulatory HDNs also functions as antigen-presenting cells (APCs), activating T-cell proliferation via upregulation of costimulatory molecules such as CD86 and tumour necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 4 (OX40L). The HDN-to-LDN ratio, reflected in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), serves as an independent prognostic marker in several cancers, including lung and BC (28). A higher proportion of HDNs generally predicts favourable outcomes. Therapeutically, strategies include enhancing HDN activity (e.g., with interferon-β [IFN-β] or TGF-β inhibitors), blocking their conversion to LDNs, and reversing immunosuppressive phenotypes using monoclonal antibodies such as programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors (11).

2.1.3 PMN-MDSCs

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a heterogeneous population of immunosuppressive myeloid cells that arise under pathological conditions from aberrantly activated bone marrow progenitors and immature myeloid cells. They reside in the bone marrow, peripheral blood, spleen, liver, lungs, and tumour tissues, and are broadly classified into PMN-MDSCs and monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (M-MDSCs). MDSCs are defined by their expression of CD11b and granulocyte receptor-1 (Gr-1) (2), and their expansion is driven by dysregulated cytokine expression in cancer, infection, and inflammatory disorders. PMN-MDSCs, a granulocytic subset of MDSCs (29), display potent immunosuppressive activity within the TME. They inhibit antitumour immunity through multiple mechanisms: (i) expression of immune checkpoint ligands such as PD-L1, which engages programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) on T cells to induce exhaustion; (ii) secretion of immunosuppressive mediators including nitric oxide (NO), arginase-1 (Arg-1), and ROS, which impair T-cell proliferation and function; and (iii) recruitment of regulatory T cells (Tregs), thereby reinforcing an immunosuppressive milieu and suppressing effector T-cell responses (30).

PMN-MDSCs also suppress natural killer (NK) cell activity. By releasing NO and TGF-β, they impair NK cell cytotoxicity and activation, weakening their tumouricidal potential (2). In addition, PMN-MDSCs promote tumour progression by secreting VEGF to stimulate angiogenesis, releasing MMP-9 to remodel the extracellular matrix (ECM) and facilitate invasion, and contributing to the establishment of pre-metastatic niches in distant organs. They also induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in tumour cells, thereby enhancing invasiveness and metastatic potential (31).

Despite extensive research, it remains unclear whether circulating neutrophils and PMN-MDSCs represent the same population or distinct subsets (32, 33). Both share common surface markers and morphological features, leading to persistent controversy. LDNs and PMN-MDSCs also demonstrate phenotypic and density-related similarities (31, 34), further complicating their distinction. Currently, no definitive method exists to discriminate neutrophils from polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (PMN-MDSCs), and whether they constitute separate entities remains unresolved.

2.2 Intratumoural neutrophils

During tumour progression, malignant cells undergo sequential stages, including formation and growth, detachment from the primary site, entry into the circulation, and colonisation of distant organs. Metastasis requires several key capacities: invasion (detachment from the primary tumour, penetration of the basement membrane, and infiltration of adjacent tissues, blood vessels, or lymphatics), extravasation (migration of tumour cells across vascular or lymphatic walls into new tissues), and colonisation at secondary sites.

As presented in Figure 2, neutrophils can exert dual regulatory roles in tumour immunity (14), depending on the microenvironmental context (35). Understanding the molecular basis of neutrophil-tumour interactions may support the development of targeted therapies. At present, TANs are classified using either the MDSC framework or the simplified N1-N2 paradigm (36). Both M-MDSCs and G/PMN-MDSCs represent immunosuppressive subsets (29). G/PMN-MDSCs often coexist with neutrophils in pathological settings and may also arise via transformation pathways from neutrophils (37). Human neutrophils are typically defined as CD14−CD11b+CD15+CD66b+ cells, distinguishing them from PMN-MDSCs on the basis of surface markers (35, 38, 39). Moreover, MDSCs can differentiate into granulocytes ex vivo, with granulocytes including neutrophils and other granular leucocytes (40).

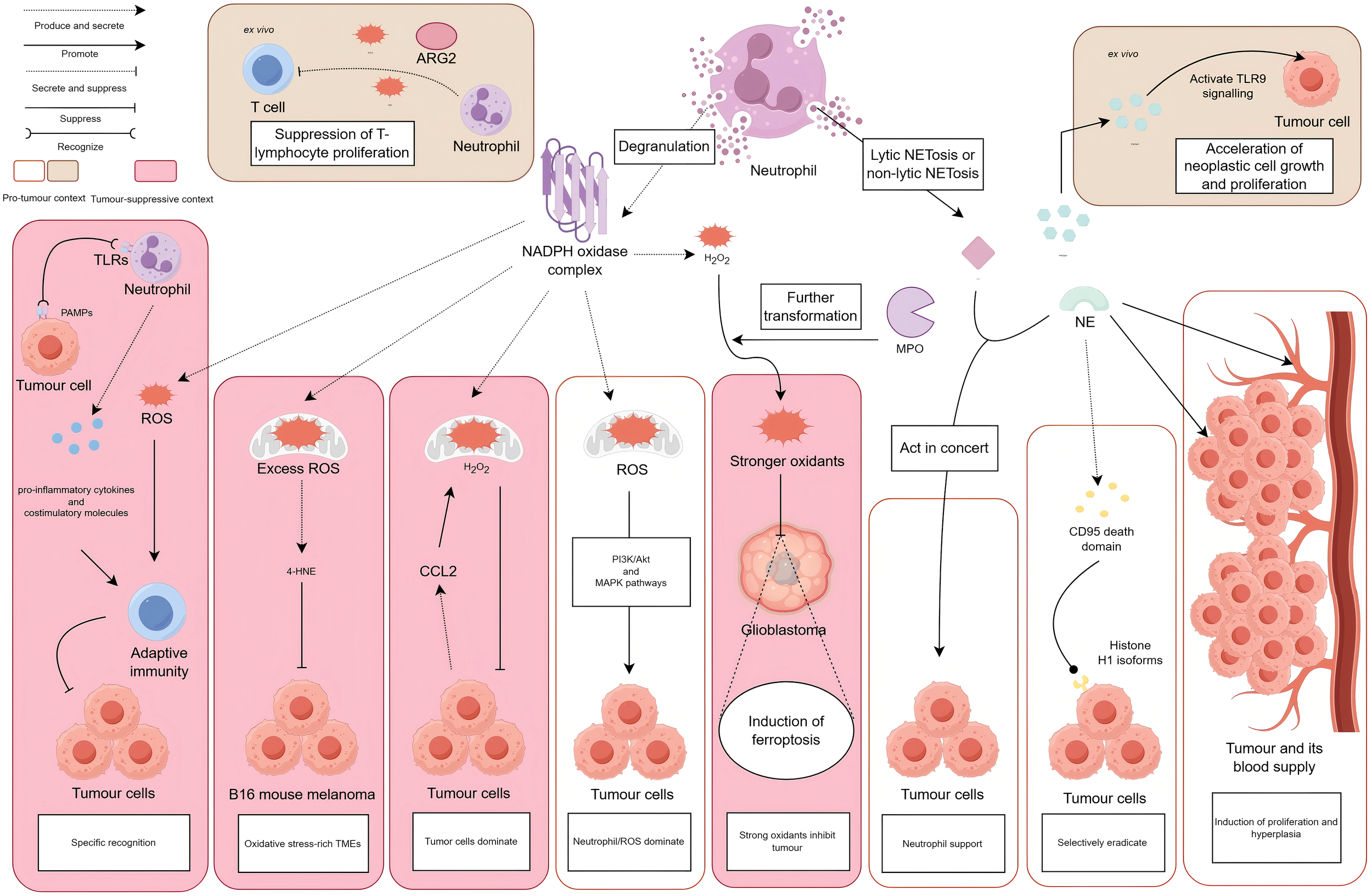

Figure 2

Neutrophils perform dual antitumoural and protumoural roles, either through degranulation that releases ROS, NO, and ARG2, or via NETosis that liberates NET components such as MPO and NE. In vitro, tumour-associated neutrophils produce ROS, NO, and ARG2, indicating a capacity for T-cell immunosuppression. Neutrophil-derived NETs stimulate HMGB1 release, which activates TLR9-dependent signalling in cancer cells and accelerates tumour proliferation. In vivo, TLR engagement on neutrophils by PAMPs triggers ROS production, proinflammatory cytokine secretion, and costimulatory molecule upregulation, together initiating adaptive antitumour immunity. Within oxidative stress-rich TMEs, excessive ROS from neutrophils initiates polyunsaturated fatty acid peroxidation cascades, yielding 4-HNE that suppresses B16-F10 melanoma growth. Tumour-secreted CCL2 mediates neutrophil H2O2 production to inhibit metastasis. In contrast, neutrophil-derived ROS activates PI3K/Akt and MAPK signalling pathways, thereby promoting tumourigenesis. MPO converts H2O2 into more potent oxidants that accumulate in glioblastoma cells alongside iron-mediated lipid peroxides, inducing ferroptosis and tumour necrosis. NE acts synergistically with MMP-9 to promote tumour migration and invasion. Proteolytic cleavage by NE releases CD95 death domains that bind histone H1 variants on malignant cells, selectively triggering apoptosis without harming normal tissues. Paradoxically, neutrophil-secreted NE also enhances tumour proliferation and angiogenesis.

Cytokine- and disease-driven stimuli polarise neutrophils into pro-tumourigenic or antitumourigenic states during tumourigenesis (41). Following the convention for macrophage polarisation (M1/M2) (42, 43), neutrophils can be broadly classified as N1 (anti-tumour) or N2 (pro-tumour). Although not all studies explicitly adopt this nomenclature, their findings are generally interpreted within this framework. N1 neutrophils are induced by IFN-β, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (38), with interferon-alpha (IFN-α) or IFN-β alone also sufficient to promote the phenotype (43, 44). By contrast, TGF-β alone induces N2 polarisation (40, 43). N2 neutrophils show upregulation of arginase 1 (ARG1), CCL17, and CXCL14, and downregulation of CXCL10, CXCL13, CCL6, tumour necrosis factor (TNF), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1), and endothelial-associated proteins (38, 43). Functionally, N2 neutrophils enhance chemotaxis, increase cytotoxicity, and suppress host immune responses. When cytokines such as TGF-β or IFNs are tested in combination with GM-CSF or G-CSF, tumour growth may either accelerate or show temporary control, reflecting the central role of cytokines in neutrophil recruitment (45–47). The precise origin of N2 neutrophils remains unresolved. It is unclear whether they derive from MDSCs recruited into tumours and subsequently transformed, or from circulating neutrophils that acquire the N2 phenotype under the influence of tumour-derived TGF-β (40, 43). Clarifying this issue may provide opportunities for therapeutic interventions targeting either systemic circulation or the tumour itself (48).

Neutrophils influence tumours in both directions using ROS/RNS and NETs (49, 50). ROS and RNS can function as signalling intermediates that sustain invasiveness in tumour cells, but can also induce senescence or apoptosis, serving as antitumour effectors (51). Accumulation of RNS contributes to oxidative stress, a hallmark of malignancy and a driver of tumour progression. NETs are fibrous DNA-histone structures decorated with granular proteins. They include proteases such as cathepsin G (CG), neutrophil elastase (NE), proteinase 3 (PR3), and MMP-2/9; enzymes such as MPO; and proteins including lactotransferrin, leucine leucine-37 (LL-37), calprotectin, bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein, pentraxin 3, citrullinated histone H3 (CitH3), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and Interleukin-17A (IL-17A) (46, 52–54). NETs and their components contribute to tumour progression via diverse mechanisms but in some contexts may also exert tumour-suppressive effects. Since neutrophils can produce similar effects via different molecules, or use the same mediator through different pathways, their functions in tumours remain highly context dependent. Table 2 summarises the principal neutrophil-derived molecules and their dual roles in tumour regulation.

Table 2

| Cytokine/factor | Biological effect | Molecular mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| CD32a, CD16b | Kill the tumour cells | Cytotoxic effect (55) |

| TNF-α | Dose-dependent dichotomous effects on neutrophil function and tumour cell viability | Immune regulation, targeting tumour cells (39, 45, 56, 58) |

| CCL2 | Suppresses tumour dissemination and exerts tumouricidal activity | ROS generation; MET pathway activation (58) |

| CCL2/CCL17 | Modulates immune mechanisms to promote tumour cell proliferation, progression, and therapy resistance | Enhances migration of HCC cells and Tregs (40) |

| NETs | Dual role: • antitumour (39, 47, 65, 71) • Pro-tumour (72, 73, 76, 77) |

Physical barrier formation (39); Immune system modulation (47, 51, 65) |

| MPO | Mediates tumour cell cytotoxicity (58) | Generates reactive ROS/RNS (58) |

| NE | Selectively eradicates malignant cells whereas providing pro-survival signals for TANs (75) | Cleaves CD95 death domain (61); Promotes angiogenesis (75) |

| NE + MMP-9 | Angiogenesis promotion | Facilitates tumour cell migration/invasion (79) |

| MMP-2/MMP-9 | Promotes tumour cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis | ECM remodelling (39, 63) |

| Histones | Tumour suppression | Tumour antigen recognition; Immune regulation (60) |

| Integrins | Tumour-promoting | Dormant tumour cell reactivation (72) |

| PAD4 | Promotes melanoma, CRC liver metastases, and pancreatic tumour growth (43, 73, 74) | Histone citrullination-induced NETosis (43, 82); Cancer-associated fibroblast(CAF) interaction (74) |

| TLRs | antitumour immunity | Adaptive immune activation (58) |

| BAFF/APRIL/IL-21 | antitumour immunity | Enhances adaptive immune responses (66) |

| CCL3/CXCL9-10/IL-12/TNF-α/GM-CSF | antitumour immunity | Cytotoxic lymphocyte activation (39, 43, 71) |

| Bv8/MMP-9/VEGF-A | Tumour-promoting | Vascular niche establishment (75) |

| IL-6 | Promote the survival of tumour cells | Anti-apoptotic signalling (88) |

| IL-8 + Neutrophils | Mediates tumour growth, angiogenesis, metastasis, extravasation, and endothelial anchoring (93) | MCAM/MUC18 interaction (melanoma) (93) |

| IL-8 + ICAM-1 | Tumour-promoting | Individual effects: Maintains tumour cell dissemination, migration, and extravasation capacity (76, 81) Cooperative effects: Mediates coordinated tumour extravasation and endothelial anchoring (82) |

| SAFP | Maintain higher invasiveness and metastatic capacity of tumour cells (79) | EMT induction (78, 79); NET formation |

| LTB4 | Metastatic niche formation | Selectively expand subgroups of cancer cells with high tumourigenic potential (76) |

| BMP2/TGF-β2 | Increased expression of HCC tumour stem cells, promoting colonisation and tumour growth | Higher levels of CXCL chemokine 5 (CXCL5) were secreted, and more TAN infiltration increased the expression of HCC tumour stem cells, promoting colonisation and tumour growth (40) |

| Matrix metalloproteinases | Metastasis/immune evasion | ECM degradation (43) |

| HMGB1 | Increases tumour aggressiveness | TLR9 pathway activation (72, 73, 77) |

| CXCR4 | Acquired the ability to generate early angiogenesis, genotoxic damage, and viral infections | In areas of the lungs rich in CXCL12; special reactions occur in the bone marrow and spleen (97) |

| ARG2 | Immune suppression | Inhibits T-cell proliferation (38, 95, 96) |

Cytokines and factors with dual roles in tumour progression and suppression.

2.2.1 Antitumour effects

Early studies showed that neutrophils exert antitumour effects through multiple mechanisms, including direct tumouricidal activity and ADCC (41). These functions are mediated by cytokine secretion, release of effector molecules, or modulation of the TME. Collectively, they induce tumour cell apoptosis, inhibit migration, regulate adaptive immune responses, and enhance host antitumour immunity (1). TANs express Fc gamma receptor IIa (FcγRIIa, CD32a), enabling recognition and elimination of immunoglobulin G (IgG)-opsonised tumour cells through antigen-antibody interactions. Fc gamma receptor IIIb (CD16b) expression is also essential: blockade with anti-FcγRIIIb immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibodies abolishes neutrophil-mediated cytotoxicity (55). Neutrophils can further induce tumour cell apoptosis by Fas receptor (FasR)-Fas ligand (FasL) engagement (56). However, some tumours evade this pathway by downregulating FasL, suggesting it may not represent the predominant neutrophil-mediated antitumour mechanism.

2.2.1.1 Secretion of specialised substances or upregulation of endogenous molecules

In murine models, neutrophils secrete tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which exerts context-dependent effects. TNF-α can support tumour growth but also induces neutrophil apoptosis, implying transient antitumour potential (39, 45). In clinical settings, therapeutic TNF-α has shown limited efficacy. Given its tumour-promoting actions, TNF-α blockade, either alone or in combination with immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), has demonstrated antitumour promise (56). Inhibiting TNF-driven activation-induced T cell death, for example, improves ICB efficacy. In oxidative stress-rich TMEs, neutrophils generate excess ROS, triggering lipid peroxidation cascades in polyunsaturated fatty acids and producing 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), which suppresses B16 mouse melanoma, Fluorescence-selected subline 10 (B16-F10) melanoma growth (57). Tumour-derived CCL2 also stimulates neutrophil production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), restricting metastatic spread. In addition, activation of the MET signalling pathway, mediated by the receptor tyrosine kinase MET and its ligand hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), enhances neutrophil NO release, which amplifies oxidative stress and promotes tumour cell killing (58). Simultaneously, elevated CCL2 from breast cancer cells recruits IFN-γ-producing monocytes, which then induce TMEM173 expression on neutrophils, enhancing their cytotoxicity (59).

2.2.1.2 NETs under antitumour conditions

NETs can function as physical barriers that limit tumour dissemination. Their histone components exert direct cytotoxic effects on tumour cells (60). Among NET proteins, MPO generates ROS/RNS that induce apoptosis. In glioblastoma, MPO amplifies iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, triggering ferroptosis and necrosis (58). NE also hydrolytically releases the CD95 death domain, which interacts with histone H1 subtypes on cancer cell surfaces, selectively killing malignant cells whereas sparing normal tissues (61). Evidence suggests that NET components may exert either antitumour or pro-tumour effects depending on their molecular interactions and context (39, 51–53, 58, 60–63).

2.2.1.3 Immunomodulatory functions: cytotoxic effects and release of bioactive substances

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), particularly Toll-like receptors (TLRs), enable neutrophils to detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Engagement of these receptors induces ROS/RNS production, release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and upregulation of costimulatory molecules, collectively priming adaptive immunity (57). Neutrophils further modulate adaptive responses through NET formation, which serves as an immunostimulatory platform that enhances lymphocyte activation (64). Splenic neutrophils secrete B cell-activating factor (BAFF), a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL), and IL-21, activating marginal zone (MZ) B cells and promoting class switching, somatic hypermutation, and antibody production (65). As APCs, neutrophils express MHC class II (MHCII) and can prime CD4+ T cells both in vitro and in vivo (66). They also secrete chemoattractants (e.g., CCL3, CXCL9, CXCL10) and cytokines (e.g., interleukin-12 [IL-12], TNF-α, GM-CSF, VEGF) that recruit and activate CD8+ T cells, thereby enhancing cytotoxicity. Through cell-cell contact and TNF-α release, neutrophils activate dendritic cells (DCs), enhancing antigen presentation and T cell priming (43). In addition, neutrophils stimulate macrophages, NK cells, and T cell subsets, amplifying antitumour immunity (39, 66). NETs further enhance T cell activation by lowering the antigen threshold required for priming, thereby boosting adaptive immune responses (47). Collectively, these findings establish neutrophils not only as innate effector cells but also as potent modulators of adaptive antitumour immunity.

2.2.1.4 Clinical applications as delivery vectors

This represents a clinically distinct approach from conventional neutrophil-mediated antitumour mechanisms, exemplified by their synergistic use with oncolytic viruses (OVs) (44). OVs selectively infect and lyse tumour cells whereas stimulating host immunity. They include DNA viruses (e.g., adenovirus [Adv], herpes simplex virus [HSV]) and RNA viruses (e.g., measles virus [MV]) (44). Their antitumour activity may occur naturally or be enhanced through genetic engineering. OVs replicate selectively within tumours, deliver therapeutic genes, and remodel the immunosuppressive TME through multiple mechanisms (67).

For example, in clinical studies combining neutrophils with vaccinia virus (VACV), intravenous administration of recombinant VACV engineered to express interleukins (ILs) enhanced neutrophil infiltration and migration. Although VACV directly targeted tumour cells, neutrophils contributed additional antitumour activity, collectively suppressing malignant mesothelioma growth modified vaccinia ankara (MVA) (68). With vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), pretreatment using the neutrophil-depleting rat anti-mouse lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus G/lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus C (Ly-6G/Ly-6C) monoclonal antibody clone RB6-8C5 (RB6-8C5) antibody (44) both recruited neutrophils and compensated for replication suppression inherent to VSV, thereby optimising the TME (69). In parallel, VSV combined with neutrophils induced disruption of tumour vasculature, attributable to VSV’s natural tropism for tumour vessels and neutrophil-mediated fibrin deposition and clot initiation (70). A key limitation of this strategy, however, is that excessive neutrophil recruitment suppresses VSV replication and dissemination, diminishing therapeutic efficacy (44).

2.2.2 Pro-tumour effects

2.2.2.1 Promotion of cancer cell activation, progression, and dissemination

NETs, induced by pro-inflammatory stimuli, remodel laminin proteolytically, activating integrins that stimulate dormant cancer cell proliferation and accelerate tumour progression (43, 71, 72). As summarised in Table 2, neutrophils promote melanoma, colorectal cancer (CRC) liver metastasis, and pancreatic cancer progression via peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PAD4) and citrullinated histone synthesis and secretion (43, 73, 74). During tumour development, neutrophils support malignant cells by promoting angiogenesis at primary and metastatic sites, thereby supplying nutrients, increasing metabolic burden, and complicating therapy. VEGF secretion is central to this process. vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) recruits pro-angiogenic CD11b+Gr-1+ (granulocyte receptor-1-positive) CXCR4+ neutrophils, enhancing post-transplant islet revascularisation and functional integration (75). Neutrophils also reinforce VEGF activity by releasing proteins such as prokineticin 2 (PROK2, also known as Bv8) and MMP-9 (75). NE has likewise been shown to drive tumour proliferation and angiogenesis (75). MDSCs, a heterogeneous immunosuppressive population, expand in the spleen and peripheral blood of cancer patients. Existing as monocytic (lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus C positive [Ly6C+]) or granulocytic (Lymphocyte Antigen 6 Complex, Locus G Positive [Ly6G+]) subsets, MDSCs exert systemic immunosuppressive and pro-angiogenic functions (43). TANs are closely related to MDSCs (39, 43), suggesting that modulation of splenic and circulating MDSCs may provide therapeutic benefit.

Cancer cell dissemination describes the spread of tumour cells or their metabolites within tissues, enabling expansion at the primary site. Dissemination occurs through passive diffusion (concentration gradients) or active diffusion (environmental changes). M2 macrophages and activated neutrophils secrete interleukin-8 (IL-8), sustaining tumour dissemination and migration (76). Increased motility and detachment from the primary lesion facilitate more extensive spread.

2.2.2.2 Promotion of tumour cell activation, detachment, and circulatory entry

Metastatic tumour cells demonstrate enhanced migration, with neutrophils playing a central role in this process (77). Neutrophils promote EMT, which confers invasive and migratory potential (78). For instance, hypopharyngeal tumour cells undergo partial EMT upon stimulation by PMNs, with more complete transformation following Staphylococcus aureus exposure, leading to greater invasiveness. In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), interactions among bacteria, neutrophils, and tumour cells accelerate the emergence of mesenchymal, metastasis-prone phenotypes (79). After EMT, tumour cells undergo morphological, molecular, and functional changes, transitioning from localised lesions to invasive malignant forms (78). They may further enhance migration by expressing surface chemoattractants or clustering with neutrophils (tumour cell-PMN complexes, TC-PMNs) via vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) interactions (80). Neutralisation of IL-8 reduces extravasation of PMN-associated tumour cells, whereas ICAM-1 overexpression provides an alternative pathway for melanoma extravasation (76, 81).

Circulating tumour cells (CTCs) undergoing EMT display heightened metastatic potential. Most CTCs exhibit incomplete EMT, co-expressing epithelial and mesenchymal markers yet showing increased malignancy (45). In BC, differential gene expression between CTCs and their associated neutrophils supports cell cycle progression, accelerating metastatic seeding (82). Neutrophils also facilitate pulmonary invasion by CTCs, enhancing survival, proliferation, invasion, and extravasation through secretion of cytokines and chemoattractants as well as NET formation. They additionally condition the pre-metastatic niche and remodel the TME to support colonisation (76, 82, 83).

2.2.2.3 Maintenance or enhancement of tumour invasion, metastasis, and colonisation

Tumour invasion refers to the penetration of the basement membrane by tumour cells at the primary site and infiltration into adjacent tissues. Metastasis denotes dissemination to distant organs, where colonisation refers to the proliferation of tumour cells following “settlement” at secondary sites. Ex vivo studies in MC38 colon cancer cell lines and hepatic metastasis models demonstrated that NETs promote release of high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), which activates Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) signalling in cancer cells. This enhances proliferation, adhesion, migration, and invasion, thereby increasing tumourigenic potential (72, 73, 77). In vivo, elevated NET levels correlate with poor prognosis in breast, colorectal, gastric, lung, and pancreatic cancers, and are strongly associated with liver, lung, and omental metastases (46). Once formed, NETs use their fibrous networks to capture CTCs, facilitating metastatic spread (76). Clinical samples from triple-negative breast cancer patients show that NETs can drive tumour metastasis. Experiments with NK cells indicate that NETs’ physical barrier contributes to their pro-tumour effects (84). NETs create a favorable microenvironment for ovarian cancer growth and metastasis, aiding its colonization in the omentum and the hepatic colonization of colorectal, lung, and breast cancers (85). At the molecular level, neutrophil elastase and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in NETs can trigger dormant lung cancer cells to proliferate through laminin remodelling (86). NE and MMP-9 cooperate to promote tumour migration and invasion (79). Similarly, MMP-2 and MMP-9 remodel the ECM, further supporting tumour cell proliferation and metastasis (38, 39). Neutrophil-secreted IL-6 enhances tumour cell survival by conferring resistance to apoptosis (87, 88). Furthermore, β2 integrins (CD18) on IL-8+ neutrophils interact with ICAM-1 on melanoma cells, anchoring tumour cells to vascular endothelium and facilitating extravasation (82). Leukotriene B4 (LTB4) has also been shown to enhance colonisation by expanding highly tumourigenic cancer cell subsets (76).

Other mechanisms include neutrophil secretion of cytokines such as CCL2 and CCL17, which modulate immune responses to promote tumour growth, progression, and drug resistance (40). Sorafenib is a treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) that enhances its anticancer effects by inhibiting CCL2 and CCL17 transcriptional regulators in neutrophils (89). In HCC, neutrophils activate stem cell activity through secretion of bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) and transforming growth factor-beta 2 (TGF-β2) and downstream mediators (40). Neutrophil-derived CXCR4-dependent transformation has also been implicated in tumour promotion within the lungs, bone marrow, and spleen (90). Additionally, neutrophils support tumour metastasis by producing matrix-degrading enzymes while simultaneously suppressing anti-tumour immune responses (43). ROS serve as signalling molecules that activate phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase [PI3K]-AKT Serine/Threonine Kinase [AKT]) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, driving tumour progression (91, 92). Furthermore, interactions between melanoma cell adhesion molecule (melanoma cell adhesion molecule [MCAM, also termed MUC18 or CD146]) on tumour surfaces and neutrophil-derived IL-8 promote melanoma proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis (93).

2.2.2.4 Neutrophils and their synthesised/secreted substances suppress tumour-specific and non-specific immune functions

Experimental evidence indicates that targeting neutrophil activity may improve therapeutic efficacy in cancer. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), modulation of neutrophil function has been shown to enhance responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) (94). Transcriptomic analyses of neutrophils from the spleen and blood of breast cancer-bearing mice revealed that tumour-induced neutrophils produce ROS, NO, and arginase 2(ARG2), suppressing T-cell proliferation ex vivo and demonstrating an immunosuppressive N2-like phenotype (38, 95, 96). In renal cell carcinoma and NSLC patients, high ARG production in neutrophils can suppress T cell functions, akin to the effect of M2 tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) (43, 59). TAMs, an immunosuppressive macrophage subset within the TME (43). Moreover, stimulation of tumour cells with Staphylococcus aureus filtrate preparation (SAFP) indirectly activates PMNs, inducing NET formation. These NETs form a barrier that impedes NK cell surveillance of partial epithelial-mesenchymal transition (p-EMT) tumour cells, enabling immune evasion and sustaining their invasive and metastatic potential (79).

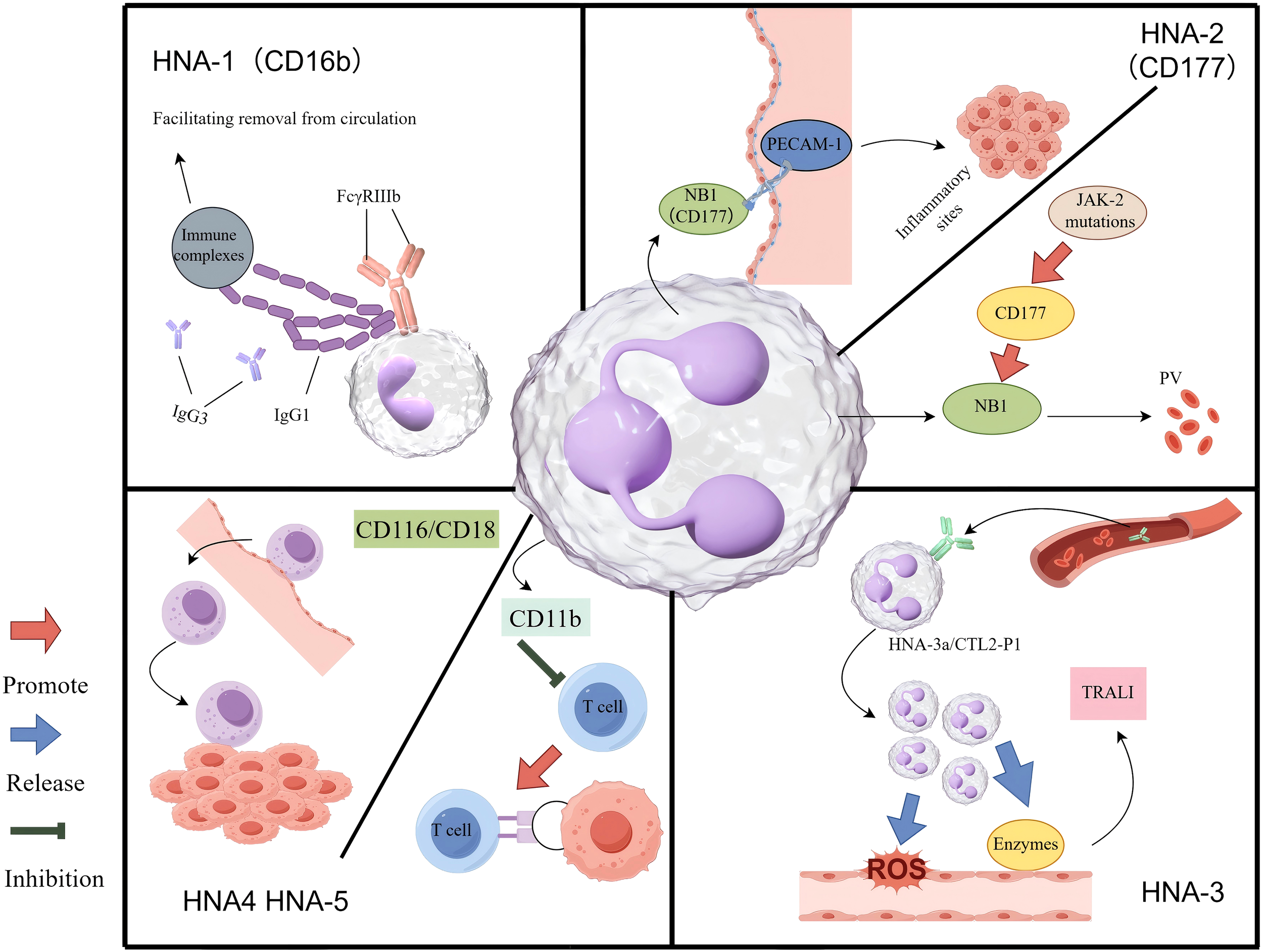

3 HNA system and tumour

The HNA system holds considerable clinical relevance in neutrophil biology. As summarised in Table 3. Non-neutrophil-specific groups, including HNA-3, HNA-4, and HNA-5, are predominantly associated with transfusion-related complications, neutropenia, HSCs transplant rejection, and renal allograft rejection (97). In addition, certain antigen subtypes regulate neutrophil function and influence the tumour immune microenvironment (TIME), thereby affecting tumour initiation, progression, treatment response, and prognosis (Figure 3).

Table 3

| HNA antigen system | Allele | Nucleotide position of corresponding Allele | Amino acid position in glycoprotein | Epitope | Glycoprotein | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional positions (141) (147) (227) (266) (277) (349) |

FccRIIIb,CD16 | |||||

| HNA-1 | FCGR3B*01 FCGR3B*02 FCGR3B*03 FCGR3B*04 FCGR3B*05 FCGR3B*null |

108G 114C 194A 233C 244G 316G 108C 114T 194G 233C 244A 316A 108C 114T 194G 233A 244A 316A 108G 114C 194A 233C 244G 316A 108C 114T 194G 233C 244G 316A No alleles |

36Arg 38Leu 65Asn 78Ala 82Asp 106Val 36Ser 38Leu 65Ser 78Ala 82Asn 106Ile 36Ser 38Leu 65Ser 78Asp 82Asn 106Ile 36Arg 38Leu 65Asn 78Ala 82Asp 106Ile 36Ser 38Leu 65Ser 78Ala 82Asp 106Ile No glycoprotein (gp) |

HNA-1a HNA-1b HNA-1d‡ HNA-1b HNA-1c HNA-1a HNA-1b|| HNA-1 null |

No gp | Low-affinity IgG receptor involved in immune complex clearance and phagocytosis (98). |

| HNA-2 | CD177 | Allelic variation of this gene does not code for different serological phenotypes Differential mRNA splicing: HNA-2 negative phenotype |

HNA-2 HNA-2null |

CD177 No gp |

Plays a role in immunoregulation and inflammatory responses (99), contributes to neutrophil function and myeloid cell proliferation. Promotes neutrophil transendothelial migration (99); co-expressed with PR3 (99). | |

| HNA-3 | SLC44A2*01 SLC44A2*02 SLC44A2*03 |

451C 455G 451C 455A 451T 455G |

151Leu 152Arg 151Leu 152Gln 151Phe 152Arg |

HNA-3a HNA-3b HNA-3a|| |

||

| HNA-4 | ITGAM*01 ITGAM*02 |

230G 230A |

Arg61 His61 |

HNA-4a HNA-4b |

CD11b | Plays a role in leucocyte adhesion and phagocytosis (100). |

| HNA-5 | ITGAL*01 ITGAL*02 |

2372G 2372C |

Arg766 Thr766 |

HNA-5a | CD11a | Leucocyte adhesion molecule (98) |

Biochemical characteristics, genetic expression and clinical significance of HNA antigen system.

‡HNA-1d is the antithetical epitope of HNA-1c.

||Variations in reactivity with human antisera may be observed.

A single allele may encode multiple epitopes (e.g., FCGR3B03 encodes both HNA-1b and HNA-1c; FCGR3B02 encodes HNA-1b and HNA-1d). Conversely, an antigen may be encoded by multiple alleles (e.g., HNA-1a is encoded by both FCGR3B01 and FCGR3B04) (4).

In this table of HNA alleles and antigens, the underlined characters/bolded (such as "106Ile" of FCGR3B03, "316A" of FCGR3B04, "244G" and "82Asp" of FCGR3B05, "HNA-3a§" of SLC44A203) represent the nucleotide/amino acid changes at these positions as the "key variant sites" of the allele, which are the core differences distinguishing this allele from other subtypes. Specifically:For example, "106Ile" of FCGR3B03: This indicates that the amino acid at position 106 of this allele is isoleucine (Ile), which is the differentiating site from other FCGR3B subtypes (such as 01/*02);"316A" of FCGR3B*04: This represents that the nucleotide at position 316 of this allele is A (adenine), a unique nucleotide variation of this allele;Similarly, the underlined annotations such as "82Asp" and "244G" are all characteristic nucleotide/amino acid sites that distinguish this allele from other subtypes, serving as the core identifiers of this allele.

Figure 3

The mechanism of HNA antigen system in inflammation and tumour. HNA-1: The FcγRIIIb receptor engages the Fc region of polymeric immune complexes through its membrane-proximal domain. In resting neutrophils, FcγRIIIb is predominantly utilized to detect immune complexes and facilitate their clearance from the circulatory system. HNA-2: Upon activation, neutrophils express HNA-2 (also referred to as NB1 glycoprotein) on their surface, which interacts with PECAM-1 on vascular endothelial cells in a coordinated manner. This interaction facilitates firm adhesion to the vessel wall, followed by cytoskeletal reorganization and transendothelial migration into tissues, where neutrophils play a role in resolving inflammation or infection. In individuals with a JAK2 mutation, hyperactivation of the CD177 gene, which regulates HNA-2 expression, leads to excessive production of NB1 glycoprotein (HNA-2). This overexpression may alter neutrophil migratory behaviour, potentially contributing to the pathogenesis of polycythemia vera. HNA-3: Circulating anti-HNA-3a antibodies interact with neutrophils expressing the HNA-3a/CTL2-P1 antigen. This antigen-antibody interaction induces neutrophil agglutination and activates NADPH oxidase. Consequently, the activated neutrophils release ROS and proteolytic enzymes, resulting in endothelial damage, compromised vascular integrity, and edema, ultimately leading to TRALI. HNA-4 & HNA-5: The CD11b/CD18 integrin facilitates the adhesion of immune cells to the vascular endothelium and supports their migration into tumour sites. On TANs, the expression of CD11b may contribute to immune evasion, in part by suppressing T-cell function.

3.1 HNA-1

3.1.1 Biochemical characteristics, genetic expression, and clinical significance

The carrier protein of HNA-1 is Fcγ receptor IIIb (FcγRIIIb, CD16b), which is anchored to the cell membrane via glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) (101). FcγRIIIb can be shed from the neutrophil surface upon stimulation by chemoattractants such as formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) or G-CSF. Currently identified HNA-1 subtypes include HNA-1a, HNA-1b, HNA-1c, and HNA-1d, encoded by allelic variants of the Fc fragment of IgG receptor IIIb (FCGR3B) gene that exhibit extensive polymorphism. HNA-1a and HNA-1b differ by five single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), resulting in four amino acid substitutions, whereas HNA-1c arises from a single-nucleotide variant (266C>A) (98). HNA-1d is defined by the Alanine-78 through Asparagine-82 (Ala78-Asn82) sequence encoded by FCGR3B02, whereas FCGR3B03 carries an Ala78Asp (alanine-to-aspartate substitution at position 78) mutation that abolishes HNA-1d expression, sharing allelic identity with HNA-1b (102).

Neutrophil development is a continuous process regulated by transcription factors and epigenetic mechanisms, identifiable by distinct progenitor states and lineages (103). In human bone marrow, neutrophil progenitors like NCP5 and NCP6, which precede promyelocytes, have unique gene expressions and differentiation potential (104). A key study found that human metamyelocytes and band cells naturally have immunosuppressive properties (105), highlighting the link between developmental stages and immune functions. FcγRIIIb (CD16b) expression starts at the myelocyte stage, leading to high HNA-1 alloantigen levels in mature neutrophils, while remaining low in early progenitors like NCP5 and NCP6 (98). In paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH), the absence of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins leads to deficient FcγRIIIb and HNA-1 expression on granulocytes (106, 107). The distribution of HNA-1 alleles varies markedly among populations. HNA-1a is highly prevalent in East Asians, whereas HNA-1b and HNA-1d are more common in Europeans. HNA-1c is rare in European and African populations and virtually absent in East Asians, including Chinese, Japanese, and Korean cohorts (108) Clinically, HNA-1 is implicated in neonatal alloimmune neutropenia (NAIN), autoimmune neutropenia (AIN), and transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI).

3.1.2 Possible mechanisms affecting the TME

HNA-1 (CD16b) likely contributes to tumour immunity through roles in immune complex clearance and phagocytosis. Certain tumours, including acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and solid tumours, may evade immune surveillance by modulating Fc gamma receptor (FcγR) expression (109). FcγRIIIb functions as a low-affinity receptor for IgG1 and immunoglobulin G3 (IgG3), binding polymeric immune complexes but not monomeric IgG. Resting neutrophils engage FcγRIIIb to bind immune complexes, facilitating their removal from circulation (98). Polymorphisms in FCGR3B influence receptor affinity: neutrophils homozygous for HNA-1a exhibit higher affinity for IgG3 and enhanced phagocytic capacity, whereas HNA-1b carriers demonstrate weaker activity (110). These differences may modulate neutrophil-mediated cytotoxicity against tumour cells.

In AML, HNA-1 antibodies are strongly associated with transfusion-related risks, particularly TRALI, which remains a major complication in patients undergoing chemotherapy or HSCs transplantation. This risk is heightened by exposure to blood products containing HNA-1 antibodies, often derived from multiparous female donors (111). Whether HNA-1 is expressed directly on AML cells remains unresolved.

3.2 HNA-2

3.2.1 Biochemical characteristics, genetic expression, and clinical significance

HNA-2, also known as the NB system, is a neutrophil-specific antigen carried by the NB1 glycoprotein, encoded by the CD177 gene. CD177 encodes a 58–64 kDa GPI-anchored glycoprotein belonging to the Ly-6/urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR)/snake toxin family, containing three N-linked glycosylation sites and two cysteine-rich domains. The gene is located on chromosome 19q13.31, spans ~9.5 kb, and comprises nine exons encoding 437 amino acids.

Unlike most HNA-2-positive individuals, who express this glycoprotein only on a variable fraction of granulocytes, HNA-2-negative individuals (equivalent to the HNA-2 null phenotype) completely lack its expression (98). The proportion of HNA-2-positive neutrophils varies markedly among individuals, and dysregulated expression has been implicated in diseases such as myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), and gastric cancer(GC) (112). A unique feature of HNA-2 is that its expression begins at the myelocyte stage and remains restricted to neutrophil subpopulations, including myelocytes, metamyelocytes, and mature segmented neutrophils (97).

HNA-2 is expressed in 97% of Caucasians, 95% of African Americans, and 89% of Japanese individuals, but only in neutrophil subpopulations, averaging 50-60% (113). Among blood cells, HNA-2 is uniquely expressed on neutrophils, localised to the plasma membrane, secondary granules, and secretory vesicles (114). Its expression is influenced by multiple factors, including sex (slightly higher in females), pregnancy, G-CSF stimulation, and severe bacterial infections. HNA-2 deficiency, observed in 3-5% of the population, arises mainly from abnormal CD177 mRNA splicing or transcriptional silencing and is strongly associated with myeloproliferative disorders (MPDs) (112, 115).

The clinical relevance of HNA-2 (CD177) spans transfusion medicine (TRALI, neonatal immune neutropenia), autoimmune disease [anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) vasculitis], haematological malignancies [diagnosis and prognosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs)], and the solid TME (potential carcinogenic functions). HNA-2, a key neutrophil antigen, is crucial for immune regulation, inflammation, neutrophil function, and myeloid cell growth (99, 112). In tumours, neutrophils have a dual role (116, 117): they can either inhibit tumour growth by activating T cells and inducing apoptosis or promote tumour progression by causing inflammation, enhancing angiogenesis, and suppressing immune responses (118). This dual function, divided into anti-tumour N1 and pro-tumour N2 phenotypes, highlights the adaptability of neutrophils in cancer immune regulation, influenced by microenvironmental signals (38).

3.2.2 Mechanisms in haematological neoplasms

Polycythaemia vera (PV) is a chronic MPN characterised by clonal expansion of erythroid, megakaryocytic, and granulocytic lineages. HNA-2 is the only antigen markedly upregulated in a neutrophil subpopulation following G-CSF stimulation in PV or during bacterial infections (119).

The NB1 glycoprotein encoded by CD177 regulates neutrophil-endothelial adhesion via binding to platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1, CD31), which is essential for transendothelial migration during inflammation (99). In PV, CD177 RNA expression is significantly increased, likely reflecting the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) V617F mutation, a central driver of disease (5, 113).

Moreover, membrane-bound proteinase 3 (mPR3), a serine protease, is co-expressed with CD177 on a neutrophil subset. HNA-2 is required for PR3 anchoring, linking it to autoimmune pathology (120). Whereas HNA-2 is a primary alloantibody target in neutropenia-related conditions, mPR3 serves as a major autoantigen in ANCA-associated vasculitis (99, 119, 120). Elevated CD177 expression is observed in PV, essential thrombocythaemia, and primary myelofibrosis, as well as in secondary polycythaemia, CML, and MDS (115). Structurally, NB1 resembles polycythaemia rubra vera-1 (PRV-1) and uPAR, both overexpressed in PV granulocytes, suggesting a shared role in haematopoiesis (121).

3.2.3 Potential association with gastric carcinogenesis

HNA-2 expression is significantly upregulated in aggressive GC tissues compared with normal gastric mucosa, correlating with tumour size, lymph node metastasis, and clinical stage (122). Immunohistochemistry reveals CD177 expression not only in tumour-infiltrating neutrophils but also in gastric adenocarcinoma cells, regardless of differentiation status (122). Given CD177’s structural similarity to uPAR, a mediator of cell adhesion and migration (123), it may regulate tumour adhesion and invasion in GC. HNA-2 overexpression may also polarise neutrophils towards pro-tumour phenotypes, promoting angiogenesis and immunosuppression within the TME. Although CD177 overexpression is linked to MPDs (e.g., PV) (115), its role in GC proliferation remains unconfirmed. Paradoxically, some data associate CD177 expression with improved prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma (122), suggesting a dual role as both a carcinogenic driver and a prognostic biomarker (120, 122). Although its precise contribution to GC proliferation remains unconfirmed, the association of CD177 with inflammation, immune regulation (99), and cell migration supports its potential role in gastric tumour progression. Large-scale clinical studies are required to validate its prognostic and therapeutic value.

3.3 HNA-3

3.3.1 Biochemical characteristics, genetic expression, and clinical significance

The HNA-3 antigen system comprises HNA-3a (formerly 5b) and HNA-3b (formerly 5a) and is not neutrophil-specific. HNA-3 antibodies can bind not only to neutrophils but also to lymphocytes, platelets, and other tissues, including inner ear structures (124). The target glycoprotein is choline transporter-like protein 2 (CTL2), encoded by Solute Carrier Family 44 Member 2 (SLC44A2). CTL2 contains five extracellular loops, with the HNA-3 antigen located on the first loop. A conformation-sensitive epitope at position 152 differentiates arginine (arginine at position 152 [Arg152], HNA-3a) from glutamine (glutamine at position 152 [Gln152], HNA-3b), defining the two polymorphisms (125). HNA-3a is encoded by the G allele, whereas HNA-3b is encoded by the A allele (126). Three genotypes/phenotypes exist: HNA-3aa homozygotes (55-64% of Caucasians), HNA-3ab heterozygotes (30-40%), and HNA-3bb homozygotes (≈5%) (127). Flow cytometry and polyclonal anti-CTL2 antibody assays indicate that HNA-3 genotypes influence antigen density on neutrophils but not overall CTL2 expression (128).

Unlike HNA-1 and HNA-2, which are neutrophil-restricted, HNA-3 exhibits multi-tissue expression, broadening its pathological relevance (120). The HNA-3a-negative phenotype occurs more frequently in East Asians (6-19%) than in Europeans (4-5%) and is rare in Africans (97). HNA-3a antibodies represent the leading cause of severe or fatal TRALI, due to combined effects on neutrophils and endothelial cells. Antibody type influences susceptibility: HNA-3ab heterozygotes are less prone to anti-HNA-3a-mediated TRALI than HNA-3aa homozygotes (128). In contrast, HNA-3b displays lower immunogenicity, and anti-HNA-3b alloantibodies are rarely clinically severe.

3.3.2 Potential association with AML

AML patients are at high risk for TRALI because of frequent transfusion requirements. Anti-HNA-3a alloantibodies can cause fatal TRALI via complement activation, leading to pulmonary microvascular endothelial damage and non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Transfusion of HNA-3a antibody-containing blood products, particularly platelets, can trigger acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in AML patients (129).

For example, a 66-year-old AML patient developed ARDS after platelet transfusion; post-mortem analysis revealed diffuse pulmonary oedema with leukaemic infiltration. Donor serum contained anti-HNA-3a antibodies, whereas the patient was HNA-3aa homozygous. Although findings suggested pulmonary leukaemic infiltration rather than typical TRALI, a role for HNA-3 antibodies could not be excluded (130). In another report, a paediatric AML patient developed fatal TRALI post-transplant after receiving platelets containing anti-HNA-3 antibodies, highlighting the potential for HNA-3 incompatibility to exacerbate pulmonary injury (111). AML-associated neutropenia, immune dysfunction, and chemotherapy may heighten vulnerability to HNA-3-mediated reactions. Following haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), donor-derived granulocytes may interact with residual recipient antibodies (e.g., anti-HNA-3), worsening transplant-associated lung injury through complement activation (129).

3.4 HNA-4

3.4.1 Biochemical characteristics, genetic expression, and clinical significance

HNA-4 is encoded by the integrin subunit alpha M (ITGAM) gene, with the antigenic determinant located on CD11b (αM subunit of the CD11b/CD18 integrin). The ITGAM gene resides on chromosome 16p11.2, spans 73 kb, and contains 30 exons encoding a 1,152-amino acid protein (97). The HNA-4a/HNA-4b polymorphism arises from an Arg61His substitution in CD11b, part of the CD11b/CD18 integrin (also known as Mac-1, CR3, or αMβ2 integrin). This integrin is expressed on neutrophils, monocytes, and NK cells, where it regulates leucocyte adhesion to endothelial cells and platelets, migration to inflammatory sites, phagocytosis, and oxidative burst activity (98, 131). Anti-HNA-4a antibodies can impair neutrophil adhesion and cause neonatal immune neutropenia. Conversely, the HNA-4b allele has been associated with increased risk of SLE (132).

3.4.2 Role in the TME

The HNA-4 antigen is located on CD11b, a key integrin subunit with dual roles in tumour immunity. CD11b activation promotes antitumour responses and suppresses tumour growth (133). In resting leukocytes, including neutrophils, monocytes, and NK cells, CD11b/CD18 remains inactive but is rapidly upregulated upon activation. This facilitates immune cell adhesion to vascular endothelium, migration to tumour sites, phagocytosis, and oxidative burst (100). Beyond these effector functions, CD11b contributes to adaptive immunity. CD11b+ DCs and macrophages present tumour antigens to CD8+ T cells, thereby enhancing cytotoxic responses (132). Clinically, high CD11b expression on tumour-infiltrating myeloid cells correlates with prolonged patient survival. Conversely, CD11b also plays a central role in establishing an immunosuppressive TME. CD11b+ Gr-1+ MDSCs inhibit T-cell activity through secretion of interleukin-10 (IL-10) and TGF-β, facilitating tumour immune evasion. Similarly, CD11b+ TAMs release VEGF and MMP-9, promoting angiogenesis and metastasis (134). During chronic inflammation, CD11b+ myeloid cells generate (ROS and proinflammatory mediators, which induce DNA damage and precancerous transformation, further linking inflammation to carcinogenesis.

3.5 HNA-5

3.5.1 Biochemical characteristics, genetic expression, and clinical significance

HNA-5 is encoded by the integrin subunit alpha L (ITGAL) gene and located on the αL subunit (CD11a) of the leucocyte β2-integrin family (CD11a/CD18, also termed lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 [LFA-1]) (125). Amino acid substitutions give rise to two subtypes: HNA-5a and HNA-5b. The ITGAL gene is positioned at 16p11.2 on chromosome 16, spans ~50.5 kb, and consists of 31 exons encoding a 1,170-amino acid protein (97). The CD11a/CD18 complex is expressed on all leucocytes and mediates leucocyte adhesion (98). The HNA-5a antigen is highly prevalent in European and East Asian populations but relatively uncommon in African populations (120). Although anti-HNA-5a alloantibodies have not been implicated in neutropenia, they have been detected in patients with aplastic anaemia. Interestingly, the HNA-5b polymorphism has been associated with enhanced immune responses to hepatitis B vaccination.

3.5.2 Molecular basis and tumour-associated pathways

The HNA-5 antigen arises from polymorphisms in CD11a/CD18. This integrin complex plays important roles in leucocyte adhesion, migration, and infiltration, particularly of neutrophils and MDSCs. It contributes to tumour cell extravasation and metastasis by regulating ECM interactions. CD11b, another β2-integrin subunit, is highly expressed on TANs and MDSCs, where it promotes immune evasion by suppressing T-cell function, in part through PD-L1/2 signalling (134). By analogy, polymorphisms in HNA-5 may influence neutrophil functional polarisation and thereby shape tumour-associated immune responses.

4 Specific tumour type-based perspectives

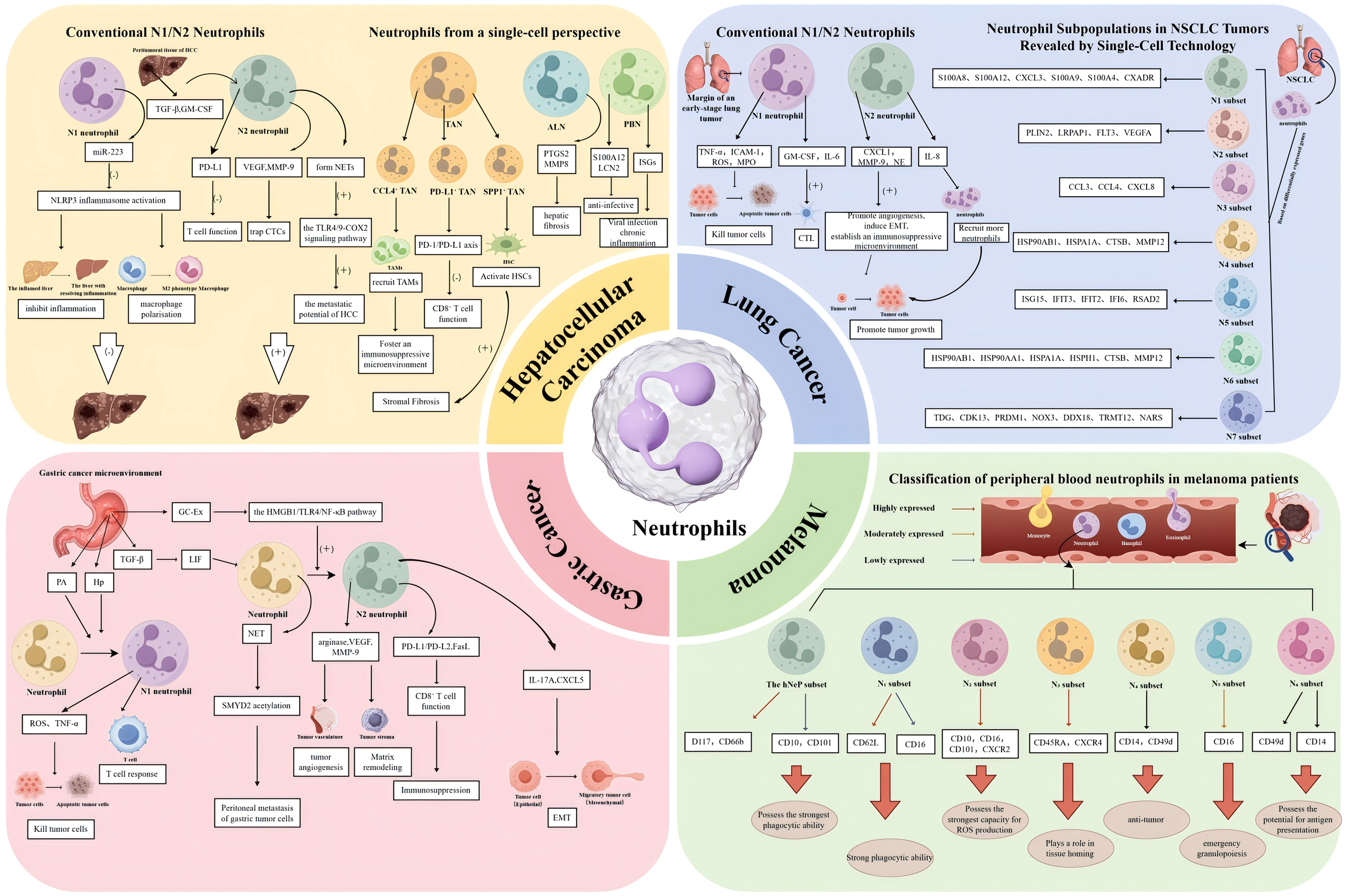

Neutrophils are central components of innate immunity and are increasingly recognised as regulators of tumour progression. They provide new opportunities for therapeutic intervention, but their heterogeneity complicates both mechanistic understanding and clinical translation. This section synthesises current research on neutrophil heterogeneity within the TME, emphasising classification systems based on phenotypic characteristics and functional specialisation (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Functional heterogeneity, molecular mechanisms, and clinical relevance of neutrophils across four cancer types. This schematic delineates the distinct neutrophil subpopulations, their regulatory mechanisms, and dual functions within the TMEs of HCC, lung cancer, GC, and melanoma, as characterized by both traditional paradigms and single-cell high-resolution technologies. HCC is depicted in two contrasting paradigms. The left panel, representing the traditional N1/N2 Paradigm, illustrates the balance between anti-tumour N1 neutrophils, such as HDNs that generate ROS and miR-223, and pro-tumour N2 neutrophils, including LDNs that are stimulated by TGF-β and GM-CSF to express PD-L1 and form NETs. In contrast, the right panel, adopting a Single-Cell Perspective, reveals the heterogeneity of TANs, ALNs, and PBNs as elucidated by scRNA-seq. This analysis identifies pro-tumour subpopulations, including CCL4-positive TANs, which facilitate macrophage recruitment; PD-L1-positive TANs, which suppress T cell activity; and SPP1-positive TANs, which contribute to fibrosis. Lung Cancer. The left panel illustrates the traditional N1/N2 paradigm, depicting the polarization of TANs into anti-tumour N1 phenotypes, induced by IFN-β, and pro-tumour N2 phenotypes, induced by TGF-β. The right panel provides a single-cell perspective, identifying seven distinct neutrophil clusters (N1-N7) through scRNA-seq in NSCLC. This analysis emphasizes key clusters, including N1 (mature), N2 (pro-angiogenic), N3 (pro-inflammatory), and N5 (interferon-responsive). Gastric cancer is examined with a focus on the origin, polarization, and functions of TANs. The accompanying diagram illustrates the recruitment of TANs from the bone marrow and their subsequent polarization into N1 (anti-tumour) and N2 (pro-tumour) phenotypes, influenced by factors such as TGF-β and IL-17A. The diagram further emphasizes key pro-tumour mechanisms mediated by N2 TANs, including NETosis through the HMGB1/TLR4 pathway, exosome secretion of miR-4745-5p, the promotion of angiogenesis via VEGF, EMT, and the induction of immunosuppression, notably through the PD-L1 pathway. In the context of melanoma, circulating neutrophils in patients who have not yet undergone treatment are classified into seven distinct subsets through CyTOF analysis. These subsets include a hNeP and six additional subsets labelled N1 through N6. Each subset is characterized by specific surface markers, such as CD10, CD16, and CD101, which are associated with the stage of the disease and the functional capacities of the cells, including phagocytosis and ROS production. Arrows are utilized to denote the pathways of differentiation, recruitment, signalling, or functional effects.

4.1 Neutrophils in hepatocellular carcinoma

HCC is one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with its TIME exerting a major influence on progression and therapeutic response (135). Primary liver cancer (PLC) comprises three main histological subtypes: HCC, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), and combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (CHC) (136). Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) have provided insight into the diversity of immune cell populations, including neutrophils, in liver cancer. Neutrophils in HCC demonstrate dual functionality: they can suppress tumour growth via antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity, yet also promote angiogenesis, immune suppression, and metastasis (38) (Figure 4).

4.1.1 Neutrophil heterogeneity: from conventional perspectives to single-cell insights

4.1.1.1 Functional subsets and mechanisms of conventional N1/N2 neutrophils

In HCC, neutrophils are commonly classified as antitumour N1 or protumour N2 subsets. N1 neutrophils exert tumouricidal effects through ROS release, cytotoxic granules, and activation of DCs and CD8+ T cells. They also secrete microRNA-223 (miR-223), which suppresses NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation, promotes resolution of hepatic inflammation, and drives macrophage polarisation towards a reparative type 2 macrophage (M2) phenotype (137). HDNs, identified by a CD16high/CD62Lhigh phenotype, represent a mature subset enriched in HCC patients with improved prognosis, with overall survival (OS) extended by approximately six months (p = 0.01) (21).

By contrast, N2 neutrophils promote HCC progression through secretion of pro-angiogenic factors (e.g., VEGF, MMP-9), immunosuppressive molecules (e.g., PD-L1, Arg-1), and NETs, which capture CTCs. He et al (138) reported that TGF-β and GM-CSF in peritumoural tissues induce PD-L1 upregulation on N2 neutrophils, suppressing T-cell activity. NETs also enhance HCC metastatic potential by activating Toll-like Receptor 4/9 (TLR4/9)-Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2) signalling (139). LDNs, recruited via the CXCL5/CXCR2 axis, facilitate angiogenesis and immune evasion (140). LDNs further suppress T-cell proliferation by depleting arginine through Arg-1 secretion (141). The proportion of LDNs in peripheral blood correlates strongly with portal vein tumour thrombus incidence in HCC patients (r = 0.71, p < 0.001), highlighting their value as predictive biomarkers (139). Overall, N1 and N2 neutrophils exert diametrically opposed effects in HCC. Their balance may critically influence tumour progression, metastasis, and therapy responsiveness, forming the basis for neutrophil-targeted immunotherapeutic strategies.

4.1.1.2 Functional subsets of neutrophils identified by single-cell sequencing

Neutrophils were once regarded as short-lived and homogeneous. However, recent studies have demonstrated marked heterogeneity within tumours. Using scRNA-seq, Zhang et al. (135) profiled 34,307 neutrophils from tumour tissue, adjacent non-tumour liver tissue, and peripheral blood of patients with HCC, identifying 11 functionally distinct subsets. These were grouped into three categories according to tissue origin and molecular features (135).

The first category comprises peripheral blood neutrophils (PBNs), such as Neu_02_s100 calcium binding protein A12 (S100A12) and Neu_03_interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15), which express high levels of antimicrobial peptide genes (e.g., S100A12, Lipocalin 2 [LCN2]), consistent with anti-infective activity. The Neu_03_ISG15 subset additionally shows activation of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), potentially associated with viral infection or chronic inflammation (135). The second category includes adjacent liver tissue neutrophils (ALNs), exemplified by Neu_05_elongation factor for RNA polymerase II 2 (ELL2), which express matrix remodelling genes such as prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) and matrix metalloproteinase 8 (MMP8). These neutrophils may contribute to hepatic fibrogenesis and tissue repair in cirrhosis (135, 141). The third category consists of TANs, including Neu_09_interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 (IFIT1), Neu_10_secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1), and Neu_11_CCL4, which display strong pro-tumourigenic functions. Single-cell trajectory analysis suggests that TANs arise primarily through phenotypic remodelling of circulating neutrophils, rather than through local proliferation (135, 142). Cross-cancer comparative analyses further indicate that HCC TANs show unique metabolic programming, characterised by upregulation of glycolytic genes (HK2, PFKP) and fatty acid oxidation genes (carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A[CPT1A]). Such metabolic reprogramming may be a central driver of their functional heterogeneity (143).

4.1.1.3 Functional subsets of TANs and their mechanisms

TANs display substantial heterogeneity in the HCC microenvironment, with distinct subsets contributing to tumour progression and immune regulation through specialised mechanisms. CCL4+ TANs (Neu_11_CCL4) act as macrophage-recruiting “accomplices.” They express high levels of CCL3 and CCL4, which recruit TAMs via the CCL4-CCR5 axis, fostering an immunosuppressive niche (135). Ex vivo co-culture of hepatoma cells with neutrophils confirmed CCL4 upregulation, and patient-derived TANs secreted significantly higher levels of CCL4 than non-TANs (135).

PD-L1+ TANs (e.g., Neu_09_IFIT1) function as T-cell “suppressors.” By overexpressing PD-L1, they inhibit CD8+ T-cell cytotoxicity through the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. CD8+ T cells co-cultured with PD-L1+ TANs exhibited markedly reduced IFNγ and granzyme B (GZMB) expression, an effect reversed by anti-PD-L1 antibodies (43). Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with high throughput sequencing (ATAC-seq) analysis further revealed increased chromatin accessibility of CD274 (encoding PD-L1) in TANs compared with non-TANs, suggesting epigenetic regulation of this phenotype (135).

SPP1+ TANs (Neu_10_SPP1) serve as stromal “facilitators.” By overexpressing osteopontin (SPP1) and integrin Integrin subunit beta 1 (ITGB1), they activate the PI3K-AKT pathway in hepatic stellate cells (HSC), driving stromal fibrosis and remodelling (135, 144). This subset is enriched in ICC, where SPP1+ TAN abundance correlates with serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) levels (r = 0.62, p = 0.003) and increased postoperative recurrence risk ([HR] = 1.8, p = 0.02), consistent with ICC’s poor prognosis (21, 135).

4.1.2 Clinical significance and therapeutic potential of neutrophils in liver cancer

4.1.2.1 Prognostic biomarkers

The Tumour-Immune Microenvironment Enhancement by Linking All Signals to Effector Responses (TIME-LASER) classification identified an immunosuppressive myeloid subtype enriched in TANs (Tumour Immune Microenvironment - Instruction, Suppression, Memory [TIME-ISM]), which correlated with shorter progression-free survival (PFS) (135). Specific TAN subsets (e.g., Neu_09, Neu_10, Neu_11) may therefore serve as independent prognostic indicators. Systemic markers also carry prognostic value: the NLR is a strong predictor of clinical outcomes. In pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (pNETs), an NLR ≥ 4 was associated with liver metastasis and poor prognosis (145). In HCC, a high NLR (>3) correlated with advanced stage, vascular invasion, and reduced OS (146), likely reflecting suppression of lymphocyte-mediated antitumour responses by expanded neutrophil populations.

4.1.2.2 Spatial distribution and functional heterogeneity of TANs

In HCC tissues, TANs are enriched at invasive margins and metastatic foci. scRNA-seq analyses identified two major TAN subsets: a pro-angiogenic subset (matrix metalloproteinase-9 positive, vascular endothelial growth factor A positive [MMP-9+VEGF-A+]) and an immunosuppressive subset (programmed death-ligand 1 positive, arginase 1 positive [PD-L1+ARG1+]). The latter contributes to immune evasion by inhibiting CD8+ T-cell activity (135). TAN density is higher in hepatic metastatic lesions than in primary tumours and correlates with complement pathway activation, suggesting that neutrophils may facilitate metastasis via complement-mediated mechanisms (145).

4.1.2.3 Therapeutic targets

Targeting TAN-mediated immune regulation offers opportunities for combination therapy. Inhibition of complement signalling (e.g., with anti-complement component 5a [C5a] antibodies) suppresses pro-tumour neutrophil functions by disrupting C5a-driven neutrophil-tumour interactions (147). Blocking the CCL4-CCR5 axis reduces TAM recruitment, reversing immunosuppressive conditions (135). Synergistic effects are evident when neutrophil-directed interventions are combined with checkpoint blockade. Targeting PD-L1+ neutrophils enhances anti-PD-1 efficacy, whereas combining anti-PD-L1 therapy with TAN depletion (e.g., anti-Ly6G antibodies) leads to potent tumour suppression in preclinical models (135). Clinically, atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1) plus bevacizumab (anti-VEGF) significantly improved survival in advanced HCC, in part through dynamic modulation of TAN phenotypes (148). Importantly, cross-species studies confirm high conservation of key TAN subsets (e.g., CCL4+ and PD-L1+), strengthening the translational potential of preclinical findings (135). Collectively, these results support TANs as promising therapeutic targets, enabling multidimensional modulation of the myeloid cell network to enhance immunotherapy efficacy.

4.2 Neutrophils in lung cancer

Lung cancer has the highest global incidence and mortality among malignant tumours. NSCLC accounts for nearly 85% of cases, yet the 5-year survival rate remains as low as 16% (141). The heterogeneity of immune cells within the TME plays a pivotal role in disease progression. TANs, a central component of the TME, have become a focus of investigation because of their functional plasticity and phenotypic diversity. Conventionally, TANs have been divided into pro-tumoural N2 and antitumoural N1 phenotypes (43). More recently, scRNA-seq has revealed additional complexity within neutrophil subpopulations (142) (Figure 4).

4.2.1 Heterogeneity of neutrophils: from traditional perspectives to single-cell insights