- 1Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 2Hematology Research Unit, King Fahd Medical Research Center, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 3Special Infectious Agents Unit, King Fahd Medical Research Center, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Antibodies represent indispensable tools in the armamentarium against infectious diseases, with widespread application in prophylactic, therapeutic, and diagnostic settings. Conventional mammalian immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies have been extensively utilized in clinical and research contexts; however, their utility is sometimes constrained by intrinsic limitations such as thermal instability, susceptibility to proteolytic degradation, limited mucosal efficacy, and the high costs associated with mammalian expression systems. These challenges have driven increasing interest in alternative antibody formats derived from non-mammalian species that offer distinct structural and functional advantages. In recent years, a growing body of research has focused on non-canonical immunoglobulins, including immunoglobulin Y (IgY) from birds, nanobodies derived from the variable domain of heavy-chain-only antibodies (VHH) in camelids, and variable new antigen receptors (VNARs) sourced from the immunoglobulin new antigen receptor (IgNAR) system in cartilaginous fish such as sharks. The structural simplicity and functional robustness of these antibody platforms enable their integration into diverse biomedical applications, encompassing passive immunization, targeted drug delivery, and point-of-care diagnostics. Indeed, these molecules exhibit unique biochemical properties, including superior thermal and protease resistance, small molecular size, and the ability to access recessed or conformational epitopes that are often inaccessible to conventional IgG antibodies. Moreover, their typically lower immunogenic profiles and reduced pro-inflammatory activity render them suitable for a broad range of therapeutic strategies, including repeated administration and mucosal delivery, and position them as particularly promising agents for combating respiratory pathogens. This review highlights the unique properties, practical advantages, and translational therapeutic potential of IgY, nanobodies, and VNARs. It underscores their advantages over traditional antibody formats and their emerging role as next-generation Immunotherapeutics in the global effort to address persistent and emerging respiratory viral threats.

1 Introduction

Antibodies have long stood as one of the most powerful tools in immunotherapy, offering targeted mechanisms to neutralize pathogens, modulate immune responses, and enable precision diagnostics (1). Among them, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) derived from mammalian immunoglobulin G (IgG) have revolutionized the treatment of infectious diseases, autoimmune conditions, and cancers (2–4). Their ability to selectively bind and inactivate viral and microbial antigens has led to several approved therapeutics and widespread clinical success. However, despite their achievements, IgG-based therapies are not without limitations. High production costs, complex manufacturing, limited stability in mucosal environments, and Fc-mediated inflammatory responses pose considerable challenges, especially for large-scale or field-deployable applications (2–4).

In response to these limitations, growing attention is being directed toward unconventional antibodies produced by non-mammalian species. Animals such as birds, camelids, and sharks have evolved unique immunoglobulin types, IgY, heavy-chain-only antibodies (HCAbs), and IgNAR, respectively, with distinctive structural and functional traits (5–8). These extraordinary antibodies offer several advantages over classical IgG, including enhanced biochemical stability, reduced immunogenicity, superior tissue penetration, and the ability to bind novel or cryptic epitopes inaccessible to conventional antibodies (5–8) (Figure 1). For instance, IgY antibodies from chicken egg yolk can be harvested non-invasively and have shown promise in mucosal protection and passive immunization (5, 9). Nanobodies, derived from the variable domain of camelid HCAbs, are small, single-domain fragments that can be engineered for high affinity and deep tissue penetration (6, 8, 10). Shark variable new antigen receptors (VNAR) derived from IgNAR antibodies represent an ancient yet highly stable form of immunity that provide evolutionary insights for therapeutic design (7, 11).

Figure 1. Structural diversity of antibodies across different species. This diagram illustrates the immunoglobulin (Ig) structures from various vertebrates, highlighting key differences in their architecture. (A) Human IgG (top left): Composed of two heavy chains and two light chains, forming a Y-shaped molecule with CH1, CH2, and CH3 constant domains, and variable VH and VL regions responsible for antigen binding. (B) Chicken IgY (top right): Structurally similar to IgG but with a longer Fc region that includes CH1–CH4 domains, lacking the hinge region seen in mammalian IgG. (C) Camelid heavy-chain antibody (bottom left): Consists solely of heavy chains without light chains, containing CH2 and CH3 domains and a single variable domain (VHH or nanobody) that mediates antigen binding. (D) Shark IgNAR (bottom right): Composed of heavy chains only, with a unique structure characterized by multiple constant domains (CNAR1–CNAR5) and a single variable domain (VNAR) at the N-terminus.

This review explores the therapeutic potential of these unconventional antibodies in combating respiratory viral infections. By highlighting both their strengths and translational potentials, this review aims to shed light on how these lesser-known unique immunoglobulins may help shape the next generation of antibody-based therapeutics.

2 IgY (avian-derived antibodies in egg yolk)

While most antibody therapies in modern medicine are based on mammalian IgG, alternative immunoglobulins found in birds have steadily gained attention, especially due to their accessibility and distinct immunological properties (1, 3). Birds have developed unique mechanisms for generating antibody diversity, primarily relying on gene conversion, rather than somatic hypermutation as seen in mammals (12).

Chief among these is Immunoglobulin Y (IgY), the major serum antibody in avian species. From an evolutionary standpoint, IgY is considered an ancient precursor to IgG (13). However, unlike IgG, which is predominantly found in mammalian plasma, IgY is naturally concentrated in egg yolk, a reflection of the bird’s strategy to confer passive immunity to its offspring during early development (14). IgY antibodies derived from egg yolk offer a range of unique properties and practical advantages that make them a compelling alternative to mammalian IgG for passive immunization strategies.

2.1 Unique properties of IgY: comparative advantages of avian IgY over mammalian IgG

Structurally, IgY differs in notable ways from its mammalian analogues (15). It is heavier in molecular weight, has a different glycosylation pattern, and lacks the hinge region found in IgG as supported by biophysical analyses (15, 16) (Figure 1). While this reduces conformational flexibility, IgY displays greater stability under harsh conditions and enhance its resilience during storage and formulation, but with less flexibility in antigen binding (17). More importantly, IgY does not bind to mammalian Fc receptors and does not activate the complement system, key factors that help minimize inflammatory responses and enhances its safety for therapeutic use (18, 19). Indeed, IgY’s lack of interaction with mammalian Fc receptors and complement proteins making it an excellent candidate for passive immunization, particularly in immune-compromised individuals or in mucosal applications where local inflammation could be detrimental (9, 18–20). In addition, this makes IgY ideal for diagnostic applications, especially in settings where interference from host IgG or rheumatoid factor can confound results (21, 22).

Immunologically, IgY benefits from its phylogenetic distance from mammals (15). Hens produce strong humoral responses after just two immunizations, generating robust quantities of specific antibodies that remain present in the yolk for several months (23, 24). This heightened responsiveness often results in greater antigen recognition breadth, especially for mammalian proteins that may be poorly immunogenic in mammals themselves (25).

Functionally, IgY has a superior stability profile (26). It demonstrates enhanced resistance to proteolytic enzymes, retaining significant biological activity even after prolonged exposure to gastrointestinal proteases such as trypsin and chymotrypsin (27). This property is especially important for oral delivery routes, where mammalian IgG would typically degrade before reaching the target site.

2.2 Practical advantages of IgY production

What makes IgY particularly appealing is not just its biological role but also its practical advantages (5). It can be harvested directly from eggs, offering a non-invasive and animal-friendly production system (28). This contrasts with traditional IgG extraction, which involves repeated blood draws from animals. From a production standpoint, IgY is remarkably cost-effective. A single hen can produce over 22 grams per year of total IgY annually, with 2% to 10% of that being antigen-specific (28). This yield is equivalent to the amount of IgG obtained from approximately four to five rabbits, but without the need for blood collection or animal sacrifice (28).

Although the current biopharmaceutical market is dominated by monoclonal IgG-based drugs, the technological and commercial potential of IgY is steadily expanding. Its production simplicity, ethical sourcing, and low-cost scalability, paired with its broad utility in diagnostics and promising results in infectious disease models, suggest that IgY is not just an academic novelty, but a serious candidate in the future landscape of immunotherapy.

2.3 Potential therapeutic applications of IgY against respiratory viruses

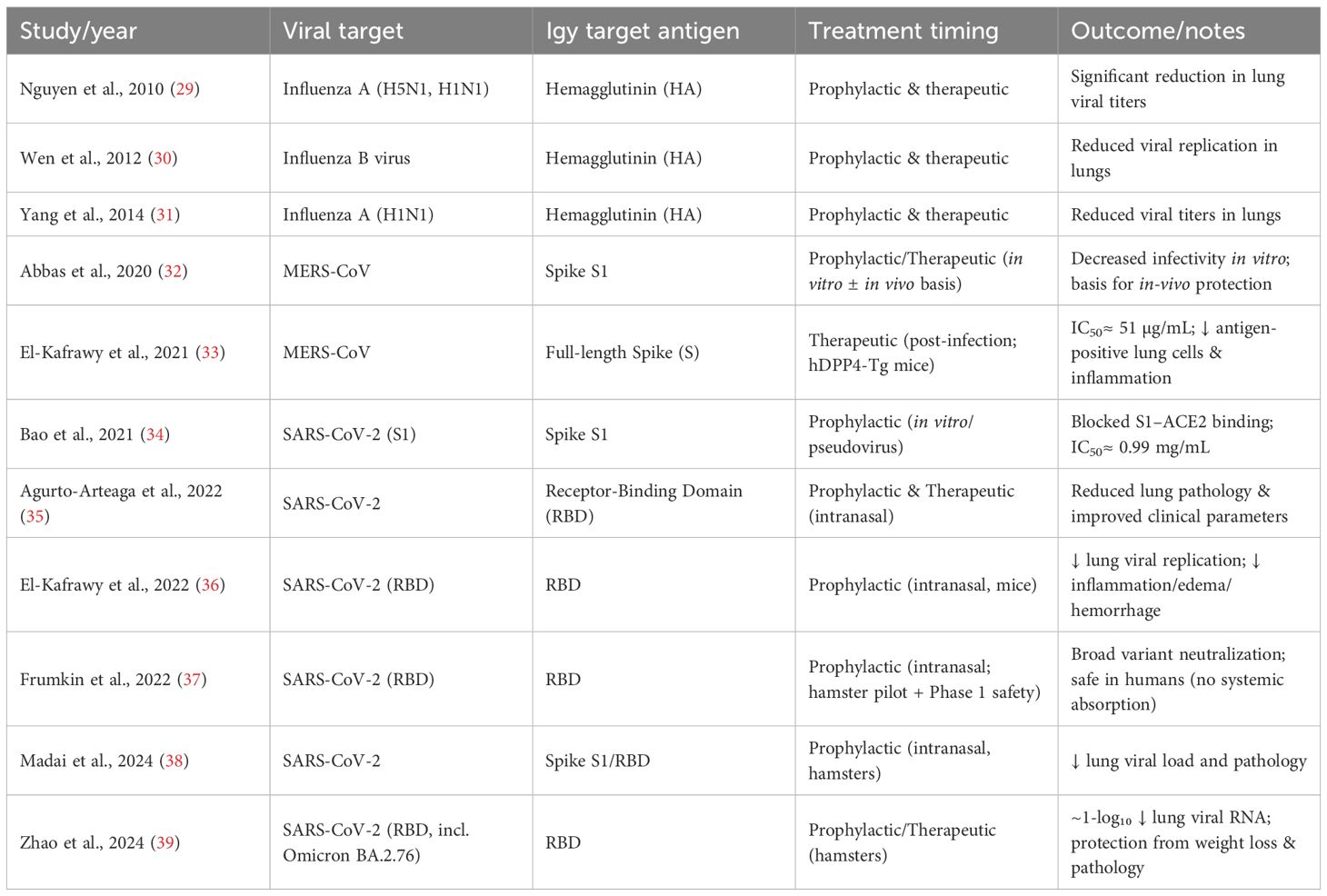

The physicochemical resilience of IgY, being stable across pH 3.5–11 and moderately resistant to pepsin degradation, makes it particularly well suited for formulations such as nasal drops, mouth rinses, and enteric-coated capsules designed to target mucosal surfaces where many respiratory viruses initially establish infection (20, 29). Recent formulation advances using alginate microspheres, chitosan nanoparticles, and lipid carriers can further extend IgY stability and bioavailability, particularly for aerosolized or lyophilized forms suitable for field or outpatient use. Hence, there is growing interest in utilizing IgY for therapeutic use, particularly for mucosal infections (Table 1). Since it shows good stability in gastrointestinal environments and does not elicit strong immune reactions when administered orally or nasally, it holds promise for passive immunization against respiratory viruses such as influenza viruses, coronaviruses (MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2), and Bovine respiratory syncytial viruses (BRSV).

Table 1. Summary of avian IgY antibodies developed against respiratory viruses, highlighting their prophylactic and therapeutic applications.

Preclinical studies have shown that chickens immunized with inactivated influenza viruses produce high titers of functional IgY in egg yolks (40). For instance, immunization with H1N1 resulted in IgY that bound strongly to viral hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, as confirmed by hemagglutination inhibition and Western blot assays (40). These IgYs reduced viral infection in plaque reduction assays and protected mice from lung pathology and weight loss when administered intranasally (40). In another study targeting influenza B, virus-specific IgY was produced in large quantities (over 75 mg per yolk) with high purity (30). In vitro assays showed the IgY neutralized infection in MDCK (Madin-Darby Canine Kidney) cells, while in vivo intranasal administration in mice reduced viral replication and provided effective protection (30). These findings support the idea that intranasal IgY delivery could be a viable tool in managing influenza outbreaks, particularly in situations where vaccine production lags behind viral evolution.

IgY antibodies have also demonstrated cross-reactivity and protection against multiple influenza strains. Mice treated intranasally with IgY against H5N1 showed full protection against not only H5N1 but also the A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) strain. Additionally, prophylactic and post-infection treatment with these antibodies conferred complete recovery in cases of lethal H5N1 and H5N2 challenges (41). Notably, trace levels of anti-H5N1 IgY have even been detected in commercially available eggs, highlighting the robustness of the immune response in hens (29). Expanding beyond chickens, ostriches have been used as an IgY source, with immunization against swine influenza virus strains yielding substantial amounts of cross-reactive IgY (40). These antibodies demonstrated strong activity against both pandemic and swine-origin H1N1 strains, as shown by ELISA, immunocytochemistry, and viral neutralization assays (40). The high yield per bird and cost-effectiveness of ostrich IgY production make this an attractive option for large-scale antibody manufacturing during pandemics. Avian species diversity (e.g., ducks, turkeys, and quails) can be a biotechnological advantage for their egg-derived immunoglobulins, some of which may show unique glycosylation patterns that enhance mucosal adhesion and viral-neutralization efficiency. Such interspecies comparisons could inform next-generation scalable antibody-farming systems.

During the 2002–2003 SARS outbreak, hens were immunized with recombinant SARS-CoV spike (S) protein antigens, generating IgY that neutralized the virus (42). These antibodies retained functionality after lyophilization, supporting their potential for long-term storage and emergency distribution (42). For SARS-CoV-2, hens were similarly immunized with the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the S protein (36). The resulting IgY was shown to competitively inhibit the interaction between viral RBD and human ACE2 receptor in vitro. Mouse models challenged with SARS-CoV-2 confirmed that intranasal IgY administration conferred protection, reducing viral load and pathological features in the respiratory tract (36). A phase I clinical trial using nasal IgY spray reported no adverse events, though large-scale efficacy data are still awaited (43, 44). Other groups have expanded this evidence base: intranasal or oral IgY formulations targeting the SARS-CoV-2 RBD demonstrated cross-neutralization against Alpha, Beta, Delta, and Omicron variants, significantly lowering lung viral RNA copies and preventing alveolar damage in animal models (36, 37, 39). The absence of systemic absorption following intranasal use underscores its safety, and the ability to rapidly adapt IgY production to new spike variants suggests an agile, variant-agnostic passive immunotherapy approach (35, 38). Furthermore, MERS-CoV studies confirmed that IgY raised against the S1 or full-length spike protein achieved potent neutralization (IC50≈ 51 µg/mL) and reduced histopathological lung inflammation in hDPP4-transgenic mice (32, 33). Together, these coronavirus-targeted IgY investigations establish a conceptual bridge between zoonotic coronaviruses and human passive-immunization platforms, positioning IgY as a first-line rapid countermeasure in future coronavirus spillovers.

Bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) shares a close genetic and pathogenic resemblance to human RSV, a major cause of lower respiratory infections in children, particularly under five years of age. There is a lack of broadly effective treatments for RSV. BRSV in calves serves as a suitable animal model for preclinical testing of novel therapeutics. In a comparative study, hens immunized with different BRSV doses produced IgY antibodies that showed high neutralizing titers in vitro (45). Notably, a simplified two-dose regimen yielded comparable results to more extended immunization schedules, suggesting that increasing antigen concentration can reduce the number of injections needed—benefiting both animal welfare and production timelines (45). Dot blot and neutralization assays confirmed the specificity of the antibodies, with measurable activity at high dilutions (up to 1:20,480) (45). These results underscore the potential of IgY as a scalable and effective agent for RSV-related prophylaxis, possibly extending to human applications in the future.

2.4 Structural, functional, and practical limitations of IgY

Despite their growing promise as next-generation immunotherapeutics, IgY exhibits intrinsic limitations that affect their pharmacological performance, manufacturability, and translational potential. Structurally, IgY lacks the flexible hinge region found in mammalian IgG, which can limit antigen-binding adaptability (5, 46). IgY is also highly sensitive to pH extremes and repeated freeze–thaw cycles, resulting in loss of activity under acidic or unstable storage conditions (47). Functionally, reviews report pH-dependent neutralization efficiency and occasionally limited in-vivo stability (5, 47). From a practical perspective, large-scale production faces hurdles such as purification complexity, batch variability, and high cost for monoclonal formulations (46) (Constantin et al., 2020). While polyclonal IgY is relatively inexpensive, scaling to clinical-grade monoclonal IgY remains challenging due to standardization and regulatory constraints (48).

In summary, avian IgY antibodies have shown considerable promise in the prophylaxis and treatment of several major respiratory viral infections. Immunization with either inactivated whole virus (e.g., H1N1, BRSV, Influenza B), or recombinant antigens (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 RBD), results in high-yield antibody production. The use of IgY offers a rapid, low-cost, and scalable countermeasure—particularly suitable for outbreak response, mucosal delivery, and passive protection, especially in vulnerable populations where vaccines are delayed or less effective. Prospectively, the integration of IgY-based prophylaxis into pandemic-preparedness frameworks could complement existing vaccine programs, especially for frontline workers or immunocompromised individuals. Advances in recombinant-antigen design, large-scale purification, and freeze-drying technologies are now enabling shelf-stable nasal or oral IgY therapeutics that can be stockpiled and deployed rapidly during viral outbreaks. As regulatory pathways for biologics evolve, IgY antibodies may soon occupy a niche similar to monoclonal antibodies, offering safe, ethical, and scalable immunotherapy derived from a renewable source.

3 Camelid nanobodies and shark VNARs (single-domain antibodies)

Single-domain antibodies (sdAbs) represent an innovative class of antibody fragments composed solely of heavy-chain variable domains, capable of binding antigens with high specificity and affinity (49). Among them, two prominent representatives have emerged: camelid- nanobodies (derived from variable domain of the heavy chain; (VHH)) and shark-derived VNARs (variable new antigen receptors derived from the IgNAR). Despite their similar monomeric formats and molecular weights (~12–15 kDa), these molecules evolved independently and exhibit distinct structural features that define their antigen-binding behavior.

Camelid nanobodies originate from heavy-chain-only antibodies found in camels, llamas, and alpacas. These VHH domains are soluble, thermally stable, and amenable to microbial expression, making them highly suitable for recombinant production (50). A defining feature of nanobodies is their elongated complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3), which enables them to reach deeply recessed or hidden epitopes, regions often inaccessible to conventional IgG antibodies (51).

In parallel, VNARs are derived from the IgNAR isotype found in cartilaginous fish, including sharks (52). Their unique stabilization mechanism relies on inter-CDR disulfide bonds, particularly between CDR1 and CDR3 (53). This configuration imparts exceptional stability under acidic or denaturing conditions, allowing VNARs to maintain binding activity in low-pH environments or in the presence of hydrophobic interfaces (53).

Both nanobodies and VNARs exhibit remarkable adaptability in recognizing a broad spectrum of antigens—from small molecules and enzymes to viral glycoproteins. Their compact size not only allows for deep antigen penetration but also supports multivalent and multispecific engineering, where several paratopes can be fused to enhance binding strength, broaden target coverage, or modulate pharmacokinetics.

3.1 Unique properties of camelid nanobodies and shark VNARs: comparative advantages to mammalian IgG

Unlike conventional antibodies like IgG, which are large and complex with two heavy and two light chains, nanobodies and VNARs are single-domain antibodies (sdAbs) that simplify this structure significantly. Nanobodies are derived from camelids (such as camels and llamas) and consist of only VHH, while VNARs come from sharks and originate from a unique type of immunoglobulin known as IgNAR (54, 55). Both are extremely small, yet retain high specificity and affinity for their targets.

The compact design of nanobodies and VNARs enables them to access recessed or hidden antigenic sites that are often inaccessible to traditional antibodies (6, 8, 51). Their small size also allows better tissue penetration and faster clearance from the body, which can be advantageous in certain therapeutic contexts. Nanobodies, in particular, feature an extended CDR3 loop that enables them to engage with hard-to-reach or deeply buried epitopes, such as enzyme pockets or viral surface grooves (51). Indeed, nanobodies excel at binding to concave and recessed surfaces on antigens, where larger antibodies typically fail due to steric hindrance. Their flexible, elongated CDR3 loops can dive into grooves and clefts (51). Nanobodies are also effective at recognizing cryptic or hidden epitopes. Studies show that VHH nanobodies can bind enzyme active sites, such as the catalytic cleft of lysozyme, through their long CDR3 loops (56). In infectious disease research, nanobodies targeting Clostridium difficile toxin components blocked enzymatic activity by penetrating the NAD-binding site (57). In the context of SARS-CoV-2, bispecific nanobodies bn03 which showed broad neutralizing activity by targeting conserved, hidden regions within the spike protein, including sites shielded in trimeric structures of RBD (58). Overall, the unique structure and biochemical properties of nanobodies and VNARs offer compelling advantages for immunotherapy, diagnostics, and biotechnology especially when targeting viral antigens or delivering antibodies to difficult-to-reach tissues.

3.2 Practical advantages of camelid nanobodies and shark VNARs production

In terms of production efficiency, these single-domain antibodies can be efficiently expressed in microbial systems like E. coli and yeast, which makes them attractive for large-scale, cost-effective manufacturing (6). Their frameworks are rich in hydrophilic residues, especially in framework region 2, enhancing their solubility and resistance to aggregation (59). In addition, nanobodies and VNARs are naturally more stable than conventional antibodies, retaining functionality across a wide range of pH, temperature, and solvent conditions (11, 50). This makes them ideal candidates for field-deployable diagnostics, oral or nasal delivery formulations, and applications in resource-limited settings (11). However, their small size also means they are rapidly cleared from circulation. To address this, they can be engineered with Fc domains, PEGylated, or fused with albumin to extend their half-life (8, 60–62). These capabilities make nanobodies and VNARs exceptionally versatile tools for the development of immunotherapies against viral infections.

3.3 Therapeutic applications of camelid nanobodies against respiratory viruses

Influenza viruses undergo frequent antigenic drift, especially in their hemagglutinin (HA) proteins, posing challenges for conventional vaccine and antibody approaches. Nanobodies, due to their structural plasticity and small size, provide promising alternatives capable of targeting conserved and often sterically shielded regions on the HA protein (63). A study designed multidomain antibodies (MDAbs) by fusing four camelid-derived nanobodies targeting distinct conserved regions across both influenza A and B strains (63). The constructs MD3606 and MD2407 target HA stem regions and receptor-binding sites of several influenza A and B strains. These MDAbs were delivered intranasally in mice using adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors, achieving robust protection against lethal challenges with H1N1 and H7N9 (63). The combined targeting of stem and receptor-binding domains blocks both viral attachment and membrane fusion, critical steps in viral entry (63). Another study demonstrated the therapeutic potential of nanobody E10 which can bind a lateral patch on the HA head domain, a cryptic site shielded from immune recognition in typical immune responses (64). This site, centered around residues K166 and S167, is conserved among H1, H3, and H7 subtypes, providing a route for broad subtype coverage (64). A study using an Fc-fused nanobody targeting HA2 reported full protection in animal models exposed to lethal IAV doses (65). Collectively, these studies highlight the unique advantage of nanobodies in penetrating conserved yet sterically hindered antigenic pockets on HA that are inaccessible to conventional monoclonal antibodies. Because of their small (≈15 kDa) monomeric size and extended CDR3 loop, VHHs can recognize epitopes buried at the interface of HA monomers or within the fusion stem, regions that remain conserved across multiple influenza subtypes. In this way, they hold strong potential as universal influenza countermeasures when combined into multidomain or multiepitope constructs.

Nanobodies also show promise against less conventional targets like neuraminidase (NA) and matrix protein M2 (66, 67). Although traditionally seen as non-neutralizing, NA-binding nanobodies have been shown to delay viral spread by preventing virion release. One study showed that NA-specific nanobodies protected mice from lethal H5N1 challenge, including oseltamivir-resistant strains (66). Similarly, nanobodies against the M2 ion channel reduced viral replication in vivo, though without full protection (67). These emerging strategies broaden the antiviral scope of nanobodies and demonstrate their flexibility in targeting dynamic and elusive viral epitopes. Moreover, the inherent stability of camelid VHHs, maintaining structure after lyophilization, high temperature exposure, and aerosolization, makes them ideal for formulations such as intranasal sprays or inhalable powders. Using AAV-encoded nanobodies have demonstrated long-term expression in respiratory epithelia, enabling months-long mucosal protection with a single administration (63). Such delivery innovations could transform prophylaxis during influenza epidemics, particularly among immunocompromised or elderly populations.

The SARS-CoV-2 S protein is a trimeric glycoprotein that plays a central role in viral entry into host cells, making it a prime target for therapeutic intervention. Nanobodies have been developed against various regions of this protein to block infection through multiple mechanisms (6). Key regions of interest include the receptor-binding domain (RBD) and the N-terminal domain (NTD). Several nanobodies, such as VHH72, mNb6, and Ty1, have demonstrated high-affinity binding to the RBD, effectively blocking the virus’s ability to interact with the ACE2 receptor (68–70). Other nanobodies like XG2v046 and XGv280 target the NTD. By destabilizing the prefusion spike trimer, they interfere with viral entry mechanisms (71). Another study introduced multivalent nanobody constructs that fuse multiple RBD-specific nanobodies into a single molecule (72). These include homotrimeric forms (e.g., EEE) that enhance avidity and potency, and biparatopic forms (e.g., VE and EV) that bind two non-overlapping epitopes on the RBD (72). The biparatopic design has proven especially effective at neutralizing diverse SARS-CoV-2 variants by reducing escape through simultaneous dual-epitope engagement (72). Further engineering has yielded aerosolized and thermostable nanobodies that remain active at room temperature and under shear stress during nebulization (73, 74). This physicochemical robustness allows their use in portable, non-invasive delivery systems suitable for both prophylaxis and post-exposure therapy. In animal models, intranasally administered nanobody cocktails provided rapid viral clearance in the upper airways, an advantage not typically achieved by parenterally administered monoclonals (75, 76).

A notable example is the bispecific nanobody bn03 (58). Cryo-EM analyses revealed that bn03 binding locks the RBD in a neutralized conformation, achieving broad activity against Omicron subvariants (BA.1, BA.2, BA.4/5) and other variants of concern (58). Furthermore, its small size and high stability allowed formulation into inhalable aerosols, which showed therapeutic efficacy in murine models by reducing viral loads in both upper and lower respiratory tracts (58). This work underscores the unique adaptability of nanobodies in rapidly evolving viral outbreaks.

Beyond RBD neutralization, recent studies have identified nanobodies targeting conserved epitopes within the S2 fusion core, capable of cross-reacting with SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV (62, 77). Such broadly reactive nanobodies could provide the foundation for pan-sarbecovirus therapeutics. Their modularity allows combination into multiepitope constructs that retain potency despite emerging mutations, a property already being explored in clinical-stage inhalable VHH therapies (76, 78).

Camelid single-domain antibodies have been extensively evaluated for RSV. Nanobodies directed against the prefusion conformation of the RSV fusion (F) glycoprotein exhibit potent neutralizing activity and therapeutic efficacy in both prophylactic and post-infection models. Intranasal and inhaled VHH constructs (bivalent, trimeric, and Fc-fused formats) have shown marked reductions in lung viral titers, inflammation, and disease severity, confirming their suitability as inhalable antiviral biologics for respiratory infections (78–81). Beyond RSV, recent investigations have extended single-domain antibody applications to human metapneumovirus (HMPV), another pneumovirus closely related to RSV. Neutralizing nanobodies have been developed against conserved trimer-interface epitopes on the HMPV F protein, providing protection in vivo (82). Of note, a study has revealed cross-neutralizing antibodies targeting structurally conserved prefusion-F epitopes shared between RSV and HMPV (83). These findings suggest that conserved antigenic sites across pneumoviruses can be exploited to design broad-spectrum single-domain antibody therapeutics, and that analogous epitope regions could serve as targets for IgY- or VNAR-based platforms in future mucosal immunotherapy development.

Collectively, the exceptional camelid nanobodies solubility, deep-epitope recognition, and facile engineering for bispecific or multivalent constructs confer unique advantages over conventional antibodies (Table 2). When coupled with intranasal or aerosol delivery routes, nanobodies represent a next-generation class of biologics capable of preventing infection at its point of entry, offering rapid, variant-resilient protection against viral respiratory infections (63, 73, 75).

Table 2. Summary of camelid single-domain antibodies (nanobodies/VHHs) targeting epitopes of respiratory viruses, demonstrating neutralization and intranasal delivery potential.

3.4 Therapeutic Applications of Shark VNARs Against Respiratory Viruses

The unique structural features and binding versatility of vNARs position them as a promising and scalable platform for the development of novel immunotherapeutics targeting conserved membrane proteins in respiratory viruses (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of shark-derived variable new antigen receptors (VNARs) with neutralizing activity against respiratory viruses.

Researchers have explored shark-derived vNARs as next-generation antiviral agents against influenza. The vNAR AM2H10 was isolated from Chiloscyllium plagiosum (bamboo shark) following immunization with nanodisc-reconstituted tetrameric M2 protein (91). This approach preserved the native membrane-bound structure of M2, enhancing antigenicity and enabling the identification of functional binders (91). AM2H10 exhibited high specificity for the native M2 tetramer, rather than linear M2e peptides, and demonstrated potent inhibition of proton channel activity in both wild-type and amantadine-resistant (S31N) M2 channels (91). This study represented the first reported vNAR with antiviral activity against influenza A, offering both broad-spectrum potential and resistance-overcoming capability (91). This discovery was particularly significant because it illustrated how VNARs, unlike conventional monoclonal antibodies, can bind to recessed or transmembrane epitopes, regions of viral ion channels and fusion proteins that are typically inaccessible. The exceptional paratope plasticity of VNARs, defined by their elongated CDR3 loops and truncated β-sandwich scaffold, allows these antibodies to probe concave epitopes, allosteric sites, and channel pores that are beyond the reach of traditional IgG or even camelid nanobodies (6, 59). This structural property gives VNARs an edge in tackling highly conserved but cryptic viral targets, such as M2, HA stem, and fusion subunits.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, where viral evolution has continually outpaced many conventional antibody therapies, shark-derived VNARs have emerged as promising next-generation therapeutics (7). Studies have demonstrated the potent neutralizing capacity of VNARs across a wide range of SARS-CoV-2 variants, including Alpha, Beta, Delta, and Omicron (7). VNARs have been isolated from both immune and synthetic libraries using phage display as the dominant selection platform, with several reengineered as Fc-fusion constructs to enhance avidity, half-life, and therapeutic potency. Notably, clones such as 20G6-Fc and SP240 have shown broad-spectrum neutralization in both in vitro and in vivo models (93). Some VNARs, such as 3B4, 2C02, and 4C10 have demonstrated strong binding and neutralizing activity (IC50< 10 nM) against both SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-1 in vitro. Furthermore, these VNARs also neutralized WIV1-CoV, a pre-emergent zoonotic virus, with 3B4 additionally capable of neutralizing MERS-CoV pseudovirus, likely due to its small size and protruding CDR3, enabling access to conserved β-coronavirus epitopes. Structural analyses revealed that 3B4 and 2C02 bind distinct, non-overlapping sites on the RBD, away from the ACE2 interface, and hence the study proposes a therapeutic cocktail comprising 3B4 and 2C02 based on their complementary binding profiles and cross-variant neutralization potential (92). Subsequent cryo-EM analyses of newer VNARs such as 79C11 and R1C2 revealed binding to conserved epitopes within the spike S2 or HR1 regions, conferring cross-neutralization against SARS-CoV-1, Omicron subvariants, and even sarbecoviruses found in bats and pangolins (95, 96). In murine models, intranasal administration of VNAR-Fc constructs led to significant reductions in lung viral loads and prevented alveolar inflammation, underscoring their potential for mucosal immunotherapy (94, 96).

Because VNARs are only 12–15 kDa, among the smallest naturally occurring antibody fragments, they display excellent thermostability, resistance to pH extremes, and compatibility with aerosolization and lyophilization. This makes them highly suitable for pulmonary delivery, as demonstrated by recent intranasal or aerosolized VNAR formulations that retained full neutralizing activity after nebulization (96). Moreover, their simple genetic structure enables rapid selection and optimization from synthetic libraries within weeks, drastically shortening discovery timelines during emerging outbreaks.

Altogether, these findings underscore the clinical potential of VNARs as highly adaptable, modular antibody formats for combating respiratory viruses. Their unique structure, compatibility with diverse engineering strategies, and rapid discovery timelines from synthetic libraries position them as a powerful complement to current antiviral platforms, especially in the face of mutational drift and vaccine resistance. Moving forward, VNARs could serve as ideal building blocks for hybrid biologics, such as bispecific VNAR–VHH or VNAR–IgY fusion constructs, combining the deep-epitope access of shark antibodies with the neutralization breadth and mucosal stability of avian and camelid systems (90, 94, 95). Their potential for low-cost microbial expression and high yield also supports future large-scale manufacturing, paving the way toward accessible, thermostable, and variant-resilient therapeutics for global respiratory health emergencies (92, 96).

3.5 Structural, functional, and practical limitations of camelid nanobodies and shark VNARs

Camelid nanobodies and shark VNARs share a compact, single-domain structure that grants unique advantages but introduces common disadvantages. Structurally, their small molecular mass (~12–15 kDa) leads to rapid renal clearance and short serum half-life, often necessitating Fc fusion or PEGylation to prolong circulation (8, 97). However, these modifications increase molecular size, limit mucosal delivery (e.g., intranasal), and elevate production cost. Both nanobodies and VNARs are prone to aggregation during bacterial or yeast expression, and shark VNARs in particular exhibit complex disulfide-bond patterns that can hinder correct folding (98).

Functionally, single-domain antibodies show reduced cross-reactivity across viral variants, particularly in highly variable spike regions (S1 domain), and cannot recruit Fc-mediated immune functions unless engineered (97). Immunogenicity remains a potential risk when derived from non-human species, especially sharks.

From a practical standpoint, the main challenges include instability during storage, loss of bacterial production efficiency after Fc fusion, high PEGylation cost, and limited industrial infrastructure for VNAR manufacturing (8). Regulatory pathways for marine- or camelid-derived therapeutic antibodies are still under development, representing a major translational bottleneck. In summary, while single-domain antibodies (VHHs and VNARs) provide exciting opportunities for respiratory antiviral therapy, their successful clinical deployment will depend on overcoming half-life limitations, stability optimization, and manufacturing scalability through continued bioengineering and regulatory innovation.

4 Conclusions and future directions

The evolution of antibody formats beyond the classical IgG paradigm has opened new horizons in the fight against viral infections. This review has explored the structural and functional diversity of alternative antibody systems derived from birds, camelids, and sharks, underscoring their capacity to overcome some of the intrinsic limitations of conventional antibodies. IgY, nanobodies, and VNARs represent distinct immunological innovations shaped by divergent evolutionary pressures, yet they converge on a common theme: adaptability to hostile environments, unique epitope recognition, and amenability to novel delivery platforms. Their demonstrated efficacy in neutralizing respiratory viruses, including influenza strains, coronaviruses, and paramyxoviruses, highlights their translational promise for both prophylactic and therapeutic applications. These antibody types also hold immense potential in the development of mucosal immunotherapies, a domain where traditional IgG-based biologics often falter due to poor stability and immunogenic complications.

Despite these advances, the clinical and commercial realization of these antibody classes remains at a formative stage. The immunogenicity of non-human-derived sequences, challenges in regulatory standardization, and the absence of large-scale manufacturing pipelines tailored to these molecules are non-trivial hurdles. Additionally, while their small size and unique architectures offer delivery advantages, they also pose pharmacokinetic limitations, including rapid systemic clearance. Overcoming these barriers will require further bioengineering innovations, such as half-life extension technologies, improved formulation strategies, and scalable recombinant production systems. It is equally essential to generate robust clinical data to validate their safety and efficacy across diverse populations and viral contexts. Nonetheless, as viral pathogens continue to evolve and evade traditional immune countermeasures, the strategic inclusion of IgY, nanobodies, and VNARs in the antiviral toolkit offers a resilient and versatile approach to next-generation immunotherapy. Their integration into mainstream biomedical pipelines will not only diversify therapeutic modalities but also enhance our preparedness for future infectious disease threats.

Author contributions

AB: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. TA: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This Project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia under grant no. (IPP: 1621-142-2025). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. AI was used only to assist with language editing, formatting consistency, and structuring of tables summarizing verified literature sources. No generative AI was used to create, interpret, or analyze scientific data or draw conclusions.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Aboul-Ella H, Gohar A, Ali AA, Ismail LM, Mahmoud AEE, Elkhatib WF, et al. Monoclonal antibodies: From magic bullet to precision weapon. Mol Biomed. (2024) 5:47. doi: 10.1186/s43556-024-00210-1

2. Liu B, Zhou H, Tan L, Siu KTH, and Guan X-Y. Exploring treatment options in cancer: tumor treatment strategies. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. (2024) 9:175. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01856-7

3. Esposito S, Amirthalingam G, Bassetti M, Blasi F, De Rosa FG, Halasa NB, et al. Monoclonal antibodies for prophylaxis and therapy of respiratory syncytial virus, SARS-CoV-2, human immunodeficiency virus, rabies and bacterial infections: an update from the World Association of Infectious Diseases and Immunological Disorders and the Italian Society of Antinfective Therapy. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:2023. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1162342

4. Puthenpurail A, Rathi H, Nauli SM, and Ally A. A brief synopsis of monoclonal antibody for the treatment of various groups of diseases. World J Pharm Pharm Sci. (2021) 10:14–22.

5. Abbas AT, El-Kafrawy SA, Sohrab SS, and Azhar EIA. IgY antibodies for the immunoprophylaxis and therapy of respiratory infections. Hum Vaccines Immunotherapeut. (2019) 15:264–75. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1514224

6. Zhu H and Ding Y. Nanobodies: from discovery to AI-driven design. Biology. (2025) 14(5):547. doi: 10.3390/biology14050547

7. Cabanillas-Bernal O, Valdovinos-Navarro BJ, Cervantes-Luevano KE, Sanchez-Campos N, and Licea-Navarro AF. Unleashing the power of shark variable single domains (VNARs): broadly neutralizing tools for combating SARS-CoV-2. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1257042. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1257042

8. Swart IC, Van Gelder W, De Haan CAM, Bosch B-J, and Oliveira S. Next generation single-domain antibodies against respiratory zoonotic RNA viruses. Front Mol Biosci. (2024) 11:2024. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2024.1389548

9. Gadde U, Rathinam T, and Lillehoj HS. Passive immunization with hyperimmune egg-yolk IgY as prophylaxis and therapy for poultry diseases–A review. Anim Health Res Rev. (2015) 16:163–76. doi: 10.1017/S1466252315000195

10. Asaadi Y, Jouneghani FF, Janani S, and Rahbarizadeh F. A comprehensive comparison between camelid nanobodies and single chain variable fragments. biomark Res. (2021) 9:87. doi: 10.1186/s40364-021-00332-6

11. Manoutcharian K and Gevorkian G. Shark VNAR phage display libraries: An alternative source for therapeutic and diagnostic recombinant antibody fragments. Fish Shellfish Immunol. (2023) 138:108808. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2023.108808

12. Lee W, Syed Atif A, Tan SC, and Leow CH. Insights into the chicken IgY with emphasis on the generation and applications of chicken recombinant monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol Methods. (2017) 447:71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2017.05.001

13. Warr GW, Magor KE, and Higgins DA. IgY: clues to the origins of modern antibodies. Immunol Today. (1995) 16:392–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80008-5

14. Rose ME, Orlans E, and Buttress N. Immunoglobulin classes in the hen's egg: their segregation in yolk and white. Eur J Immunol. (1974) 4:521–3. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830040715

15. Zhang X, Calvert RA, Sutton BJ, and Doré KA. IgY: a key isotype in antibody evolution. Biol Rev Cambridge Philos Soc. (2017) 92:2144–56. doi: 10.1111/brv.12325

16. Shimizu M, Nagashima H, Sano K, Hashimoto K, Ozeki M, Tsuda K, et al. Molecular stability of chicken and rabbit immunoglobulin G. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. (1992) 56:270–4. doi: 10.1271/bbb.56.270

17. Kovacs-Nolan J and Mine Y. Egg yolk antibodies for passive immunity. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. (2012) 3:163–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-022811-101137

18. Tian Z and Zhang X. Progress on research of chicken IgY antibody-FcRY receptor combination and transfer. J Receptor Signal Transduction Res. (2012) 32:231–7. doi: 10.3109/10799893.2012.703207

19. Kubickova B, Majerova B, Hadrabova J, Noskova L, Stiborova M, and Hodek P. Effect of chicken antibodies on inflammation in human lung epithelial cell lines. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. (2014) 35 Suppl 2:99–104.

20. Rahman S, Van Nguyen S, Icatlo FC Jr., Umeda K, and Kodama Y. Oral passive IgY-based immunotherapeutics: a novel solution for prevention and treatment of alimentary tract diseases. Hum Vaccines Immunotherapeut. (2013) 9:1039–48. doi: 10.4161/hv.23383

21. da Silva MC, Schaefer R, Gava D, Souza CK, da Silva Vaz I Jr., Bastos AP, et al. Production and application of anti-nucleoprotein IgY antibodies for influenza A virus detection in swine. J Immunol Methods. (2018) 461:100–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2018.06.023

22. Thirumalai D, Visaga Ambi S, Vieira-Pires RS, Xiaoying Z, Sekaran S, and Krishnan U. Chicken egg yolk antibody (IgY) as diagnostics and therapeutics in parasitic infections - A review. Int J Biol Macromol. (2019) 136:755–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.06.118

23. Thu HM, Myat TW, Win MM, Thant KZ, Rahman S, Umeda K, et al. Chicken egg yolk antibodies (IgY) for prophylaxis and treatment of rotavirus diarrhea in human and animal neonates: A concise review. Korean J Food Sci Anim Resources. (2017) 37:1–9. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2017.37.1.1

24. Nilsson E, Stålberg J, and Larsson A. IgY stability in eggs stored at room temperature or at +4 °C. Br Poul Sci. (2012) 53:42–6. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2011.646951

25. Gassmann M, Thömmes P, Weiser T, and Hübscher U. Efficient production of chicken egg yolk antibodies against a conserved mammalian protein. FASEB J: Off Publ Fed Am Societies Exp Biol. (1990) 4:2528–32. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.8.1970792

26. Carlander D, Stålberg J, and Larsson A. Chicken antibodies: a clinical chemistry perspective. Upsala J Med Sci. (1999) 104:179–89. doi: 10.3109/03009739909178961

27. Dávalos-Pantoja L, Ortega-Vinuesa JL, Bastos-González D, and Hidalgo-Alvarez R. A comparative study between the adsorption of IgY and IgG on latex particles. J Biomater Sci Polymer Ed. (2000) 11:657–73. doi: 10.1163/156856200743931

28. Pauly D, Dorner M, Zhang X, Hlinak A, Dorner B, and SChade R. Monitoring of laying capacity, immunoglobulin Y concentration, and antibody titer development in chickens immunized with ricin and botulinum toxins over a two-year period. Poul Sci. (2009) 88:281–90. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00323

29. Nguyen HH, Tumpey TM, Park H-J, Byun Y-H, Tran LD, Nguyen VD, et al. Prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of avian antibodies against influenza virus H5N1 and H1N1 in mice. PloS One. (2010) 5:e10152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010152

30. Wen J, Zhao S, He D, Yang Y, Li Y, and Zhu S. Preparation and characterization of egg yolk immunoglobulin Y specific to influenza B virus. Antiviral Res. (2012) 93:154–9. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.11.005

31. Yang Y-e, Wen J, Zhao S, Zhang K, and Zhou Y. Prophylaxis and therapy of pandemic H1N1 virus infection using egg yolk antibody. J Virol Methods. (2014) 206:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.05.016

32. Abbas AT, El-Kafrawy SA, Sohrab SS, Tabll AA, Hassan AM, Iwata-Yoshikawa N, et al. Anti-S1 MERS-COV igY specific antibodies decreases lung inflammation and viral antigen positive cells in the human transgenic mouse model. Vaccines (Basel). (2020) 8(4):634. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8040634

33. El-Kafrawy SA, Abbas AT, Sohrab SS, Tabll AA, Hassan AM, Iwata-Yoshikawa N, et al. Immunotherapeutic efficacy of igY antibodies targeting the full-length spike protein in an animal model of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Pharmaceuticals. (2021) 14:511. doi: 10.3390/ph14060511

34. Bao L, Zhang C, Lyu J, Yi P, Shen X, Tang B, et al. Egg yolk immunoglobulin (IgY) targeting SARS-CoV-2 S1 as potential virus entry blocker. J Appl Microbiol. (2022) 132:2421–30. doi: 10.1111/jam.15340

35. Agurto-Arteaga A, Poma-Acevedo A, Rios-Matos D, Choque-Guevara R, Montesinos-Millán R, Montalván Á, et al. Preclinical assessment of igY antibodies against recombinant SARS-coV-2 RBD protein for prophylaxis and post-infection treatment of COVID-19. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:2022. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.881604

36. El-Kafrawy SA, Odle A, Abbas AT, Hassan AM, Abdel-dayem UA, Qureshi AK, et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific immunoglobulin Y antibodies are protective in infected mice. PloS Pathogens. (2022) 18:e1010782. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010782

37. Frumkin LR, Lucas M, Scribner CL, Ortega-Heinly N, Rogers J, Yin G, et al. Egg-derived anti-SARS-coV-2 immunoglobulin Y (IgY) with broad variant activity as intranasal prophylaxis against COVID-19. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:2022. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.899617

38. Madai M, Hanna D, Hetényi R, Földes F, Lanszki Z, Zana B, et al. Evaluating the protective role of intranasally administered avian-derived igY against SARS-coV-2 in Syrian hamster models. Vaccines. (2024) 12:1422. doi: 10.3390/vaccines12121422

39. Zhao B, Peng H, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Kong D, Cao S, et al. Rapid development and mass production of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing chicken egg yolk antibodies with protective efficacy in hamsters. Biol Res. (2024) 57:24. doi: 10.1186/s40659-024-00508-y

40. Tsukamoto M, Hiroi S, Adachi K, Kato H, Inai M, Konishi I, et al. Antibodies against swine influenza virus neutralize the pandemic influenza virus A/H1N1. Mol Med Rep. (2011) 4:209–14. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.410

41. Wallach MG, Webby RJ, Islam F, Walkden-Brown S, Emmoth E, Feinstein R, et al. Cross-protection of chicken immunoglobulin Y antibodies against H5N1 and H1N1 viruses passively administered in mice. Clin Vaccine Immunol: CVI. (2011) 18:1083–90. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05075-11

42. Fu CY, Huang H, Wang XM, Liu YG, Wang ZG, Cui SJ, et al. Preparation and evaluation of anti-SARS coronavirus IgY from yolks of immunized SPF chickens. J Virol Methods. (2006) 133:112–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.10.027

43. Gjetting T, Gad M, Fröhlich C, Lindsted T, Melander MC, Bhatia VK, et al. Sym021, a promising anti-PD1 clinical candidate antibody derived from a new chicken antibody discovery platform. mAbs. (2019) 11:666–80. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2019.1596514

44. Yakhkeshi S, Wu R, Chelliappan B, and Zhang X. Trends in industrialization and commercialization of IgY technology. Front Immunol. (2022) 13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.991931

45. Ferella A, Bellido D, Chacana P, Wigdorovitz A, Santos MJD, and Mozgovoj MV. Chicken egg yolk antibodies against bovine respiratory syncytial virus neutralize the virus in vitro. Proc Vaccinol. (2012) 6:33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.provac.2012.04.006

46. Constantin C, Neagu M, Diana Supeanu T, Chiurciu V, and D AS. IgY - turning the page toward passive immunization in COVID-19 infection (Review). Exp Ther Med. (2020) 20:151–8. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8704

47. Wang H, Zhong Q, and Lin J. Egg yolk antibody for passive immunization: status, challenges, and prospects. J Agric Food Chem. (2023) 71:5053–61. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c09180

48. Budama-Kilinc Y, Kurtur OB, Gok B, Cakmakci N, Kecel-Gunduz S, Unel NM, et al. Use of immunoglobulin Y antibodies: biosensor-based diagnostic systems and prophylactic and therapeutic drug delivery systems for viral respiratory diseases. Curr Topics Med Chem. (2024) 24:973–85. doi: 10.2174/0115680266289898240322073258

49. Hamers-Casterman C, Atarhouch T, Muyldermans S, Robinson G, Hamers C, Songa EB, et al. Naturally occurring antibodies devoid of light chains. Nature. (1993) 363:446–8. doi: 10.1038/363446a0

50. Kunz P, Zinner K, Mücke N, Bartoschik T, Muyldermans S, and Hoheisel JD. The structural basis of nanobody unfolding reversibility and thermoresistance. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:7934. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26338-z

51. Vu KB, Ghahroudi MA, Wyns L, and Muyldermans S. Comparison of llama VH sequences from conventional and heavy chain antibodies. Mol Immunol. (1997) 34:1121–31. doi: 10.1016/S0161-5890(97)00146-6

52. Greenberg AS, Avila D, Hughes M, Hughes A, McKinney EC, and Flajnik MF. A new antigen receptor gene family that undergoes rearrangement and extensive somatic diversification in sharks. Nature. (1995) 374:168–73. doi: 10.1038/374168a0

53. Kovalenko OV, Olland A, Piché-Nicholas N, Godbole A, King D, Svenson K, et al. Atypical antigen recognition mode of a shark immunoglobulin new antigen receptor (IgNAR) variable domain characterized by humanization and structural analysis. J Biol Chem. (2013) 288:17408–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.435289

54. Minatel VM, Prudencio CR, Barraviera B, and Ferreira RS. Nanobodies: a promising approach to treatment of viral diseases. Front Immunol. (2024) 14:2023. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1303353

55. Lim HT, Kok BH, Lim CP, Abdul Majeed AB, Leow CY, and Leow CH. Single domain antibodies derived from ancient animals as broadly neutralizing agents for SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses. Biomed Eng Adv. (2022) 4:100054. doi: 10.1016/j.bea.2022.100054

56. Lauwereys M, Arbabi Ghahroudi M, Desmyter A, Kinne J, Hölzer W, De Genst E, et al. Potent enzyme inhibitors derived from dromedary heavy-chain antibodies. EMBO J. (1998) 17:3512–20. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3512

57. Unger M, Eichhoff AM, Schumacher L, Strysio M, Menzel S, Schwan C, et al. Selection of nanobodies that block the enzymatic and cytotoxic activities of the binary Clostridium difficile toxin CDT. Sci Rep. (2015) 5:7850. doi: 10.1038/srep07850

58. Li C, Zhan W, Yang Z, Tu C, Hu G, Zhang X, et al. Broad neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 variants by an inhalable bispecific single-domain antibody. Cell. (2022) 185:1389–401.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.009

59. Muyldermans S. Single domain camel antibodies: current status. J Biotechnol. (2001) 74:277–302. doi: 10.1016/S1389-0352(01)00021-6

60. Kontermann RE. Strategies to extend plasma half-lives of recombinant antibodies. BioDrugs: Clin Immunotherapeut Biopharmaceut Gene Ther. (2009) 23:93–109. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200923020-00003

61. Moliner-Morro A, JS D, Karl V, Perez Vidakovics L, Murrell B, McInerney GM, et al. Picomolar SARS-coV-2 neutralization using multi-arm PEG nanobody constructs. Biomolecules. (2020) 10(12):1661. doi: 10.3390/biom10121661

62. Hanke L, Das H, Sheward DJ, Perez Vidakovics L, Urgard E, Moliner-Morro A, et al. A bispecific monomeric nanobody induces spike trimer dimers and neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 in vivo. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:155. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27610-z

63. Laursen NS, Friesen RHE, Zhu X, Jongeneelen M, Blokland S, Vermond J, et al. Universal protection against influenza infection by a multidomain antibody to influenza hemagglutinin. Sci (New York NY). (2018) 362:598–602. doi: 10.1126/science.aaq0620

64. Chen ZS, Huang HC, Wang X, Schön K, Jia Y, Lebens M, et al. Influenza A Virus H7 nanobody recognizes a conserved immunodominant epitope on hemagglutinin head and confers heterosubtypic protection. Nat Commun. (2025) 16:432. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-55193-y

65. Voronina DV, Shcheblyakov DV, Favorskaya IA, Esmagambetov IB, Dzharullaeva AS, Tukhvatulin AI, et al. Cross-reactive fc-fused single-domain antibodies to hemagglutinin stem region protect mice from group 1 influenza a virus infection. Viruses. (2022) 14(11):2485. doi: 10.3390/v14112485

66. Cardoso FM, Ibañez LI, Van den Hoecke S, De Baets S, Smet A, Roose K, et al. Single-domain antibodies targeting neuraminidase protect against an H5N1 influenza virus challenge. J Virol. (2014) 88:8278–96. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03178-13

67. Wei G, Meng W, Guo H, Pan W, Liu J, Peng T, et al. Potent neutralization of influenza A virus by a single-domain antibody blocking M2 ion channel protein. PloS One. (2011) 6:e28309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028309

68. Hanke L, Vidakovics Perez L, Sheward DJ, Das H, Schulte T, Moliner-Morro A, et al. An alpaca nanobody neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 by blocking receptor interaction. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:4420. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18174-5

69. Schoof M, Faust B, Saunders RA, Sangwan S, Rezelj V, Hoppe N, et al. An ultrapotent synthetic nanobody neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 by stabilizing inactive Spike. Sci (New York NY). (2020) 370:1473–9. doi: 10.1126/science.abe3255

70. Schepens B, van Schie L, Nerinckx W, Roose K, Van Breedam W, Fijalkowska D, et al. An affinity-enhanced, broadly neutralizing heavy chain-only antibody protects against SARS-CoV-2 infection in animal models. Sci Trans Med. (2021) 13:eabi7826. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abi7826

71. Zhu Q, Liu P, Liu S, Yue C, and Wang X. Enhancing RBD exposure and S1 shedding by an extremely conserved SARS-CoV-2 NTD epitope. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. (2024) 9:217. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01940-y

72. Koenig PA, Das H, Liu H, Kümmerer BM, Gohr FN, Jenster LM, et al. Structure-guided multivalent nanobodies block SARS-CoV-2 infection and suppress mutational escape. Sci (New York NY). (2021) 371(6530):eabe6230. doi: 10.1126/science.abe6230

73. Esparza TJ, Chen Y, Martin NP, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Bowen RA, Tolbert WD, et al. Nebulized delivery of a broadly neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific nanobody prevents clinical, virological, and pathological disease in a Syrian hamster model of COVID-19. mAbs. (2022) 14:2047144. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2022.2047144

74. Huo J, Mikolajek H, Le Bas A, Clark JJ, Sharma P, Kipar A, et al. A potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralising nanobody shows therapeutic efficacy in the Syrian golden hamster model of COVID-19. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:5469. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25480-z

75. Wu X, Wang Y, Cheng L, Ni F, Zhu L, Ma S, et al. Short-term instantaneous prophylaxis and efficient treatment against SARS-coV-2 in hACE2 mice conferred by an intranasal nanobody (Nb22). Front Immunol. (2022) 13:2022. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.865401

76. Aksu M, Kumar P, Güttler T, Taxer W, Gregor K, Mußil B, et al. Nanobodies to multiple spike variants and inhalation of nanobody-containing aerosols neutralize SARS-CoV-2 in cell culture and hamsters. Antiviral Res. (2024) 221:105778. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2023.105778

77. Stalin Raj V, Okba NMA, Gutierrez-Alvarez J, Drabek D, van Dieren B, Widagdo W, et al. Chimeric camel/human heavy-chain antibodies protect against MERS-CoV infection. Sci Adv. (2018) 4:eaas9667. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aas9667

78. Cunningham S, Piedra PA, Martinon-Torres F, Szymanski H, Brackeva B, Dombrecht E, et al. Nebulised ALX-0171 for respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infection in hospitalised children: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir Med. (2021) 9:21–32. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30320-9

79. Schepens B, Ibañez LI, De Baets S, Hultberg A, Bogaert P, De Bleser P, et al. Nanobodies® Specific for respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein protect against infection by inhibition of fusion. J Infect Dis. (2011) 204:1692–701. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir622

80. Detalle L, Stohr T, Palomo C, Piedra Pedro A, Gilbert Brian E, Mas V, et al. Generation and characterization of ALX-0171, a potent novel therapeutic nanobody for the treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. (2015) 60:6–13. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01802-15

81. Larios Mora A, Detalle L, Gallup JM, Van Geelen A, Stohr T, Duprez L, et al. Delivery of ALX-0171 by inhalation greatly reduces respiratory syncytial virus disease in newborn lambs. mAbs. (2018) 10:778–95. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2018.1470727

82. Ballegeer M, van Scherpenzeel RC, Delgado T, Iglesias-Caballero M, García Barreno B, Pandey S, et al. A neutralizing single-domain antibody that targets the trimer interface of the human metapneumovirus fusion protein. mBio. (2024) 15:e0212223. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02122-23

83. Wen X, Suryadevara N, Kose N, Liu J, Zhan X, Handal LS, et al. Potent cross-neutralization of respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus through a structurally conserved antibody recognition mode. Cell Host Microbe. (2023) 31:1288–300.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2023.07.002

84. Ibañez LI, De Filette M, Hultberg A, Verrips T, Temperton N, Weiss RA, et al. Nanobodies with in vitro neutralizing activity protect mice against H5N1 influenza virus infection. J Infect Dis. (2011) 203:1063–72. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq168

85. Barbieri ES, Sosa-Holt C, Ibañez LI, Baztarrica J, Garaicoechea L, Gay CL, et al. Anti-hemagglutinin monomeric nanobody provides prophylactic immunity against H1 subtype influenza A viruses. PloS One. (2024) 19:e0301664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0301664

86. Hwang J, Jang I-Y, Bae E, Choi J, Kim JH, Lee SB, et al. H1N1 nanobody development and therapeutic efficacy verification in H1N1-challenged mice. Biomed Pharmacother. (2024) 176:116781. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116781

87. Zhao G, He L, Sun S, Qiu H, Tai W, Chen J, et al. A novel nanobody targeting middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-coV) receptor-binding domain has potent cross-neutralizing activity and protective efficacy against MERS-coV. J Virol. (2018) 92(18):e00837-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00837-18

88. Wrapp D, De Vlieger D, Corbett KS, Torres GM, Wang N, Van Breedam W, et al. Structural basis for potent neutralization of betacoronaviruses by single-domain camelid antibodies. Cell. (2020) 181:1004–15.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.047

89. Wu X, Cheng L, Fu M, Huang B, Zhu L, Xu S, et al. A potent bispecific nanobody protects hACE2 mice against SARS-CoV-2 infection via intranasal administration. Cell Rep. (2021) 37:109869. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109869

90. Liu Q, Lu Y, Cai C, Huang Y, Zhou L, Guan Y, et al. A broad neutralizing nanobody against SARS-CoV-2 engineered from an approved drug. Cell Death Dis. (2024) 15:458. doi: 10.1038/s41419-024-06802-7

91. Yu C, Ding W, Zhu L, Zhou Y, Dong Y, Li L, et al. Screening and characterization of inhibitory vNAR targeting nanodisc-assembled influenza M2 proteins. iScience. (2023) 26:105736. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105736

92. Ubah OC, Lake EW, Gunaratne GS, Gallant JP, Fernie M, Robertson AJ, et al. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 neutralization by shark variable new antigen receptors elucidated through X-ray crystallography. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:7325. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27611-y

93. Feng B, Chen Z, Sun J, Xu T, Wang Q, Yi H, et al. A class of shark-derived single-domain antibodies can broadly neutralize SARS-related coronaviruses and the structural basis of neutralization and omicron escape. Small Methods. (2022) 6:e2200387. doi: 10.1002/smtd.202200387

94. Chen W-H, Hajduczki A, Martinez EJ, Bai H, Matz H, Hill TM, et al. Shark nanobodies with potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing activity and broad sarbecovirus reactivity. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:580. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36106-x

95. Liu X, Wang Y, Sun L, Xiao G, Hou N, Chen J, et al. Screening and optimization of shark nanobodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD. Antiviral Res. (2024) 226:105898. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2024.105898

96. Feng B, Li C, Zhang Z, Huang Y, Liu B, Zhang Z, et al. A shark-derived broadly neutralizing nanobody targeting a highly conserved epitope on the S2 domain of sarbecoviruses. J Nanobiotechnol. (2025) 23:110. doi: 10.1186/s12951-025-03150-2

97. De Vlieger D, Ballegeer M, Rossey I, Schepens B, and Saelens X. Single-domain antibodies and their formatting to combat viral infections. Antibodies (Basel Switzerland). (2018) 8(1):1. doi: 10.3390/antib8010001

Keywords: IgY, nanobody, VHH, vNAR, IgNAR, respiratory viral infections, immunotherapy, influenza

Citation: Basabrain AA and Alandijany TA (2025) Unique antibodies across the animal kingdom (birds, camelids, and sharks): therapeutic potential against human respiratory viral infections. Front. Immunol. 16:1723343. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1723343

Received: 12 October 2025; Accepted: 04 November 2025; Revised: 01 November 2025;

Published: 21 November 2025.

Edited by:

Junping Hong, The Ohio State University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Basabrain and Alandijany. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Thamir A. Alandijany, dGFsYW5kaWphbnlAa2F1LmVkdS5zYQ==

Ammar A. Basabrain1,2

Ammar A. Basabrain1,2 Thamir A. Alandijany

Thamir A. Alandijany