Abstract

Osteosarcoma (OS), the most common primary malignant bone tumor in children and adolescents, remains a major therapeutic challenge due to its high metastatic potential and limited response to conventional treatments, including immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Oncolytic viruses (OVs) have emerged as a promising strategy with dual antitumor functions: direct oncolysis and the induction of immunogenic cell death (ICD). By releasing damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and activating the cGAS–STING pathway, OVs can remodel the immunologically “cold” tumor microenvironment (TME) into an inflamed and immune-responsive phenotype, thereby enhancing CD8+ T-cell infiltration and improving antitumor immunity. Encouraging preclinical evidence has been reported: VSV-IFNβ-NIS achieved a long-term survival rate of approximately 35% in canine OS models, and synergistic combination regimens have demonstrated tumor inhibition rates exceeding 70%. Despite these advances, OV-based therapies still face critical translational challenges, including the immunosuppressive TME, intratumoral delivery barriers, and safety concerns. This review systematically summarizes the molecular mechanisms underlying OV-mediated antitumor immunity, evaluates current clinical evidence, and highlights future opportunities, such as combination immunotherapy, mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-based delivery platforms, and AI-driven precision medicine approaches. Our goal is to provide a comprehensive theoretical framework to support the clinical translation and personalized application of OV therapy in osteosarcoma.

1 Introduction

Osteosarcoma (OS) is the most common primary malignant bone tumor, predominantly affecting children and adolescents. It is characterized by high aggressiveness and a strong propensity for metastasis, particularly to the lungs, which remains the leading cause of mortality (1). While neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with surgical resection can increase the 5-year survival rate to approximately 70% for patients without metastasis, this rate drops by more than half once pulmonary metastasis develops (1). Even with multidrug chemotherapy, the 5-year survival rate remains below 20%, especially in cases where metastatic lesions cannot be completely removed (2, 3). Moreover, conventional immunotherapies such as PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have demonstrated limited clinical benefit in OS, largely due to its inherent low tumor mutational burden (TMB), impaired antigen presentation, and profoundly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME), leading to objective response rates typically below 10% (4, 5). These limitations underscore the urgent need for novel therapeutic approaches capable of reshaping OS immunogenicity and improving survival outcomes.

Oncolytic viruses (OVs) have emerged as a promising immunotherapeutic strategy for OS (6), offering dual antitumor mechanisms. First, OVs selectively infect and lyse tumor cells, inducing immunogenic cell death (ICD) and releasing damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), including ATP, HMGB1, and calreticulin, alongside tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), thereby mediating direct tumor cytotoxicity (7, 8). Second, OVs activate innate immune pathways, notably the cGAS-STING signaling axis, stimulating robust type I interferon responses and enhancing recruitment and activation of immune effector cells (9, 10). Concomitantly, OVs promote dendritic cell antigen presentation, trigger tumor-specific T-cell immunity, and drive macrophage polarization from an immunosuppressive M2 phenotype toward a pro-inflammatory M1 state, effectively converting an immunologically “cold” TME into a “hot” one enriched with infiltrating CD8+ T cells (11, 12). Recent findings further indicate that oHSV engineered to express GM-CSF can augment PD-1 blockade responses and strengthen NK-cell-mediated cytotoxicity, collectively reversing OS-associated immune suppression (13, 14).

Several OVs have already demonstrated clinical potential. T-VEC is FDA-approved for melanoma, and DNX-2401 has shown durable survival benefit and favorable safety in glioblastoma patients (15, 16). In the context of OS, agents such as VCN-01, Delta-24-ACT, and VSV-IFNβ-NIS have significantly suppressed tumor growth and extended survival in preclinical models (6, 17), offering a compelling foundation for further translational development.

This review aims to address four key questions (Figure 1):

Figure 1

Oncolytic virus therapy for osteosarcoma: transforming “cold” into “hot” tumors. This figure illustrates the therapeutic paradigm of oncolytic virus (OV)-mediated immune remodeling in osteosarcoma. Left panel (Problem): Osteosarcoma exhibits an immunologically “cold” tumor microenvironment (TME) characterized by immunosuppression, resulting in minimal response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs; <10% objective response rate). Center panel (Mechanism): OVs selectively infect and lyse tumor cells, inducing immunogenic cell death (ICD) and releasing damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). This triggers three parallel immune activation pathways: (1) cGAS-STING signaling (blue arrow) promotes type I interferon production; (2) Dendritic cell (DC) activation (green arrow) enhances CD8+ T cell priming and cross-presentation; (3) Tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) reprogramming (orange arrow) drives M2-to-M1 polarization with enhanced pro-inflammatory function. These coordinated mechanisms converge to transform immunologically “cold” tumors into “hot” immune-reactive environments. Right panel (Outcomes and Future): Preclinical and early clinical evidence demonstrates that OV therapy achieves 35% long-term survival rates and 70% tumor suppression, accompanied by enhanced T cell infiltration (represented by the inflamed tumor). Future translational strategies include artificial intelligence (AI)-guided precision medicine, mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-based delivery systems to overcome delivery barriers, and rationally designed combination therapies to maximize therapeutic efficacy. Arrows indicate directional biological processes; color-coded pathways distinguish immune activation mechanisms; gradient transitions represent the cold-to-hot tumor transformation continuum.

-

1. How do OVs synergistically exert antitumor effects in OS through induction of ICD, activation of critical signaling pathways, and remodeling of the TME?

-

2. What is the current preclinical and clinical evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of OV-based therapies in OS, and what major obstacles—such as immune evasion and delivery barriers—impede clinical translation?

-

3. How can combination therapies with ICIs, novel delivery platforms, and optimized dosing strategies overcome these challenges and achieve superior therapeutic outcomes?

-

4. How might AI-driven personalized approaches and intelligent delivery systems advance OV therapy toward precision oncology in OS?

2 Core mechanisms of oncolytic virus therapy in osteosarcoma

Upon infection of tumor cells, oncolytic viruses (OVs) can induce immunogenic cell death (ICD) in osteosarcoma through multiple coordinated pathways, including caspase-3/7–dependent apoptosis, MLKL-mediated necroptosis, GSDME-dependent pyroptosis, and autophagy-associated cell death (18). These processes lead to the release of classical damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), such as HMGB1, calreticulin, and ATP (19, 20), and promote the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β and IL-18 via GSDME-driven pyroptosis, thereby fostering a robust inflammatory response that amplifies antitumor immunity (18). In parallel, OV infection generates pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), and together with DAMPs, elicits strong innate immune recognition and activation through multiple pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), effectively breaking tumor-induced immune tolerance that limits conventional therapies (19, 20).

These effects converge on three critical immunoregulatory mechanisms that collectively shape the therapeutic efficacy of OV therapy:

-

(1) activation of the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase–stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS–STING) pathway,

-

(2) enhancement of dendritic cell-mediated antigen presentation and T-cell priming, and

-

(3) repolarization of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype.

The cGAS–STING signaling axis represents a central mechanism of OV-induced immune activation. During viral replication, both viral double-stranded DNA and tumor-derived cytosolic DNA accumulate and are recognized by the DNA sensor cGAS, which catalyzes the synthesis of cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) from ATP and GTP. cGAMP subsequently binds and activates STING (21, 22). Activated STING recruits TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), leading to phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of IRF3, which directly drives type I interferon (IFN-I) expression. Concurrently, NF-κB signaling is engaged, resulting in robust production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 (21–23), thereby establishing an immune-inflamed tumor microenvironment that favors antitumor responses. However, due to the pronounced intratumoral heterogeneity of osteosarcoma, both the expression and functional activity of the cGAS–STING pathway vary considerably among tumor cells, resulting in differential production of inflammatory chemokines such as CXCL10 and CCL5 (24). These variations ultimately influence the efficiency of immune cell recruitment and the magnitude of antitumor immune activation (22).

Dendritic cell (DC)–mediated antigen presentation and T-cell priming serve as an essential intermediate link in the antitumor immune cascade triggered by oncolytic virotherapy. Upon OV infection, tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are released and rapidly recognized and internalized by DCs, thereby enabling efficient antigen presentation (25–27). Among these subsets, cDC1 plays a pivotal role by cross-presenting exogenous antigens on MHC-I molecules, resulting in the activation of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and subsequent tumor cell killing (26–28). In addition, OV infection can directly upregulate MHC-I expression on tumor cells (19, 20), or indirectly enhance antigen presentation by activating the cGAS–STING pathway and promoting type I interferon production, which further increases the expression of co-stimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86) and MHC-I/MHC-II molecules on DCs (25–28), thereby helping overcome the impaired antigen presentation frequently observed in osteosarcoma (19, 20). Besides antigen presentation, co-stimulatory signaling, such as the CD40/CD40L axis, synergistically promotes the activation of CTLs and helper T cells. Together, the coordinated induction of antigen presentation and co-stimulation ultimately establishes a robust adaptive immune response network to exert antitumor immunity (29).

Reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) represents another critical component of OV-mediated remodeling of the tumor immune microenvironment. OV infection induces a local proinflammatory milieu and facilitates the repolarization of immunosuppressive M2-like TAMs into proinflammatory M1-like macrophages, thereby reshaping the tumor microenvironment (TME) (19, 30). Mechanistically, OVs suppress IL-4/IL-13–activated STAT6 signaling and IL-10–activated STAT3 signaling to reverse M2 polarization (31, 32). Meanwhile, DAMPs and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) released after OV infection activate TLR7/8/9 and trigger the MyD88–NF-κB signaling cascade, promoting STAT1 activation and driving the expression of M1-related genes including iNOS, TNF-α, and IL-12 (16, 31–35). This phenotypic transition is accompanied by a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation typical of M2 macrophages toward a glycolytic program characteristic of M1 macrophages, which provides essential bioenergetic support for inflammatory responses and antitumor activity (23, 31). Furthermore, M2-to-M1 repolarization markedly enhances macrophage antigen-presenting capacity and phagocytic function (19, 30), thereby boosting NK cell and T-cell effector responses. This forms a positive feedback loop that sustains and amplifies antitumor immunity within the TME (19, 30).

OV-mediated immune activation follows a coordinated temporal cascade (25–28). In the early phase of infection, viral replication induces the rapid release of DAMPs and PAMPs (6, 8), which are sensed by tissue-resident DCs. Subsequently, activation of the cGAS–STING pathway drives type I interferon production (21–23), promoting DC maturation and upregulation of MHC-I and co-stimulatory molecules (25–28). Mature DCs then migrate to the draining lymph nodes, where they prime naïve CD8+ T cells via CD40–CD40L signaling (26–29). Ultimately, activated effector T cells home to the tumor site, where they cooperate with M1-polarized TAMs to execute cytotoxic activity (26–28).

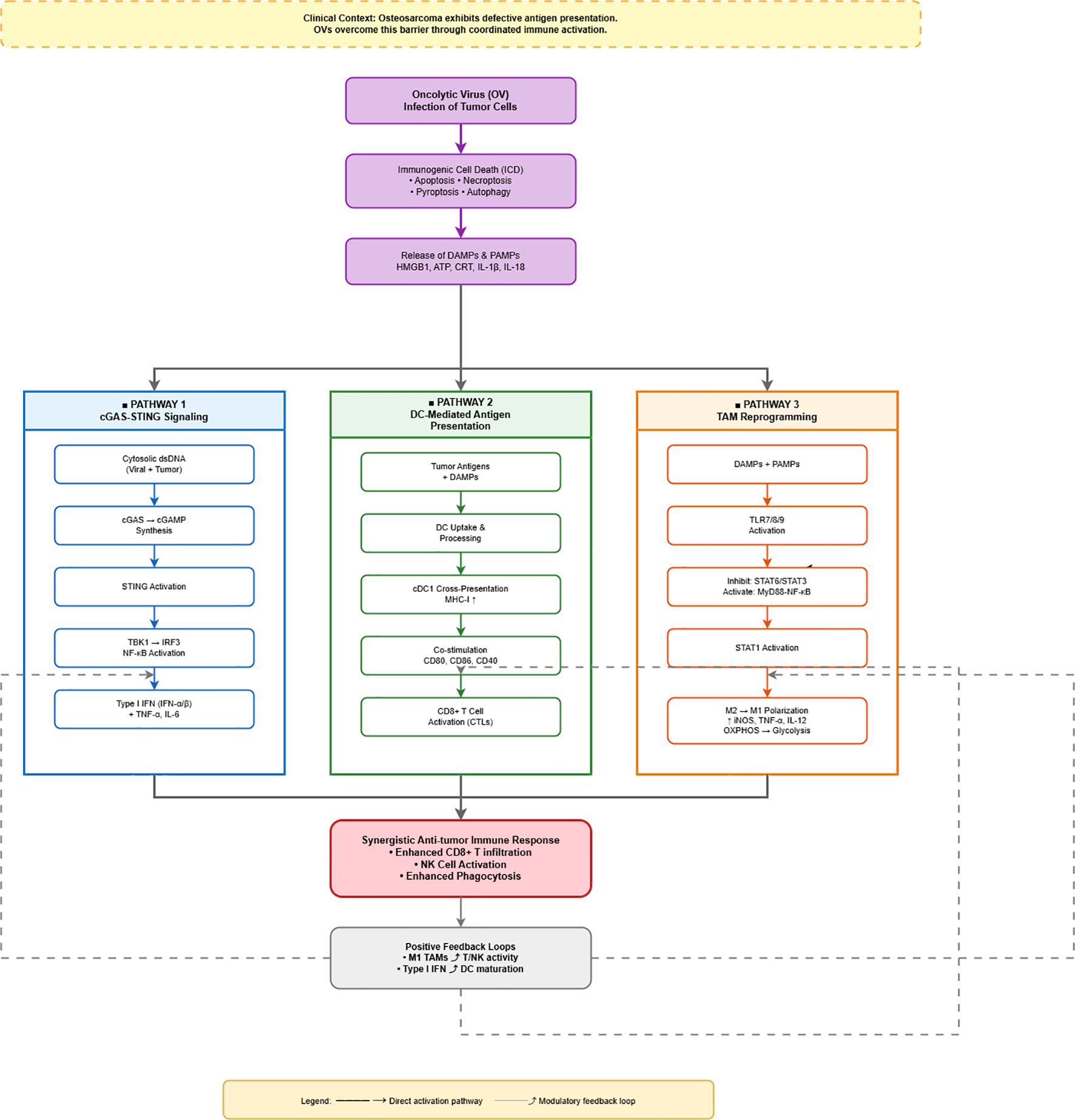

This spatiotemporally ordered process involves the coordinated engagement of three interdependent immune pathways (Figure 2): the cGAS–STING signaling axis (blue), DC-mediated antigen presentation and T-cell priming (green), and M2-to-M1 TAM repolarization (orange). These pathways reinforce each other through positive feedback loops, collectively driving a synergistic antitumor immune response. Detailed mechanisms, regulatory events, OV categories, and signaling interactions are systematically summarized in Tables 1-4: Table 1 outlines OV-induced ICD molecular pathways; Table 2 details cGAS–STING/type I IFN signaling; Table 3 describes the molecular framework of the DC–T-cell activation axis; and Table 4 compiles pathways and effectors involved in M2-to-M1 repolarization.

Figure 2

Mechanistic pathways of oncolytic virus-mediated antitumor immunity in osteosarcoma. This figure depicts how oncolytic viruses (OVs) overcome defective antigen presentation in osteosarcoma through coordinated immune activation. OV infection induces immunogenic cell death (ICD), releasing damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). These danger signals simultaneously activate three parallel pathways (color-coded columns): (1) cGAS-STING signaling (blue) recognizes cytosolic DNA and produces type I interferons and pro-inflammatory cytokines; (2) DC-mediated antigen presentation (green) enables cross-presentation via MHC-I and co-stimulation, activating CD8+ T cells; (3) TAM reprogramming (orange) activates TLR signaling to drive M2-to-M1 macrophage polarization with enhanced pro-inflammatory function. These pathways converge to generate a synergistic antitumor immune response characterized by enhanced T cell infiltration, NK cell activation, and increased phagocytosis. Positive feedback loops (dashed arrows) further amplify immunity: M1 TAMs enhance T/NK activity, while type I interferons promote DC maturation. Solid arrows indicate direct pathways; dashed arrows represent modulatory feedback. Color coding emphasizes the distinct yet coordinated nature of the three parallel immune activation mechanisms.

Table 1

| Mechanism | Key components/processes | Biological function | Applicable OV types | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAMPs release | HMGB1, ATP, calreticulin (CRT) | Activates APC-mediated antigen presentation and promotes DC maturation | HSV, adenovirus, ORFV | (6, 8, 40, 60–64) |

| PAMPs release | Viral nucleic acids and proteins | Triggers PRRs, induces type I IFN signaling, enhances innate immunity | Broad OV species | (6, 8, 40, 62, 63) |

| Immunogenic apoptosis | Caspase-3/7 | Tumor cell lysis and antigen release | HSV, adenovirus | (8, 60, 62, 63) |

| Programmed necrosis | MLKL | Immunogenic necroptosis with robust DAMPs release | HSV, SFV | (8, 62) |

| Pyroptosis | GSDME, caspase-1/8, IL-1β/18 | Inflammatory rupture, promotes IL-1β release and T-cell infiltration | ORFV | (62, 65) |

| Autophagy-associated death | LC3, Beclin-1 | Enhances antigen processing and improves T-cell priming | NDV | (62, 63) |

| Immune activation | Type I IFN, IL-1β, IL-18 | Promotes DC activation and CTL responses | Multiple OV types | (8, 40, 60, 62–64) |

| Microenvironment remodeling | TAM reprogramming, NK/T cell activation | Converts “cold” tumors into immunologically “hot” tumors | HSV, GM-CSF-modified OVs | (6, 13, 40, 61) |

Molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways of OV-induced immunogenic cell death (ICD) in osteosarcoma.

This table summarizes seven major mechanistic modules of OV-induced ICD, including DAMP/PAMP release, pyroptosis, necroptosis, and autophagy pathways contributing cooperatively to antitumor immunity.

Table 2

| Mechanism | Key molecules | Functional role | Influencing factors | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytosolic DNA accumulation | Viral or tumor-derived dsDNA | Activates cGAS as an innate immune sensor | OV infection or genomic instability | (21, 22, 66) |

| cGAS activation and cGAMP synthesis | cGAS, cGAMP | Produces second messenger cGAMP to activate STING | cGAS expression levels determine responsiveness | (21, 22) |

| STING activation and trafficking | STING, TBK1 | Golgi translocation and TBK1 recruitment/activation | Cell-line-dependent signaling variations | (21, 22) |

| Downstream signaling | TBK1, IRF3 | IRF3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation to induce IFN genes | Pathway integrity determines IFN induction efficiency | (21, 22) |

| Effector cytokine production | IFN-α/β, TNF-α, IL-6 | Enhances antitumor and antiviral signaling; activates DCs and T cells | Facilitates immune activation and cell recruitment | (21–23) |

| Immune microenvironment remodeling | M1 polarization, DAMPs | Suppresses immunosuppression and reshapes tumor microenvironment | Supports synergy with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade | (66, 67) |

| Cell line heterogeneity | STING, cGAS | Determines pathway activity and OV response | Biomarker for selecting responsive patients | (22) |

cGAS–STING/type I interferon pathway activation by OVs in osteosarcoma.

This table outlines the full signaling cascade of OV-triggered cGAS–STING activation and emphasizes its bridging role in initiating antitumor immunity.

Table 3

| Mechanism | Key elements | Functional consequences | Regulatory factors | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor antigen release | TAAs, DAMPs | Initiates DC activation and priming | Critical ICD-associated step | (25–27) |

| DC activation and maturation | cGAS–STING, type I IFN, CD80/86, MHC-I/II | Enhances antigen presentation and T-cell priming | Predominantly dependent on Batf3-driven cDC1 | (25–28) |

| Cross-presentation | cDC1, CD103+ DCs | Efficient activation of CD8+ T cells against neoantigens | Essential for immune memory | (26–28) |

| T-cell activation | CD8+ CTL, CD4+ Th, CD40/CD40L | Mediates tumor killing and long-term response | Requires DC-derived costimulation | (25–29) |

| Microenvironment remodeling | Reduced Tregs, increased CD8+/CD4+ infiltration | Limits immune escape and improves ICI response | OVs act as immune-sensitizing platforms | (26–28) |

OV-mediated activation of the DC–T cell axis in osteosarcoma.

This table highlights key steps in DC–T cell crosstalk, including antigen presentation, T-cell activation, and microenvironment modulation.

Table 4

| Mechanism | Pathway/targets | Immunological effect | Representative agents | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition of M2 polarization | IL-4/IL-13-STAT6, IL-10-STAT3, TGF-β | Reduces pro-tumor functions and immunosuppression | STAT6/STAT3 inhibitors, anti-TGF-β | (31, 32, 68) |

| Activation of M1 polarization | TLR7/8/9, MyD88, NF-κB, STAT1 | Enhances pro-inflammatory responses and antigen presentation | TLR agonists, CpG ODN, engineered exosomes | (16, 31–35, 69) |

| Metabolic reprogramming | PFKFB3, HK2 | Supports glycolysis-driven M1 phenotype | 2-DG, PFKFB3 inhibitors | (23, 31) |

| Targeting M2-specific markers | MARCO, IL4R, CD206 | Eliminates or reprograms M2-like TAMs | Anti-MARCO Abs, IL4R inhibitors | (70, 71) |

| TME signaling regulation | DAMPs, PAMPs, IFN-γ, GM-CSF | Promotes M1 differentiation and immune recruitment | OV infection, GM-CSF-engineered cells | (16, 31–35, 72) |

| Suppression of immunosuppressive factors | IL-10, TGF-β, VEGF | Limits angiogenesis and immune escape | Neutralizing antibodies; small-molecule inhibitors | (16, 31–35, 72) |

Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies for TAM repolarization (M2 to M1).

This table summarizes major signaling axes and therapeutic approaches for TAM repolarization, supporting TME remodeling strategies.

Despite compelling preclinical evidence suggesting that introducing immune checkpoint blockade after sufficient OV-induced antigen presentation may enhance T-cell effector function (11), this idealized temporal model may be disrupted in osteosarcoma due to multiple barriers. These include inefficient DC cross-presentation (26), excessive infiltration of immunosuppressive myeloid populations (12), and intrinsic STING pathway deficiencies within tumor cells (36). Importantly, these bottlenecks represent potential intervention targets for optimized combination strategies.

3 Opportunities

Oncolytic virotherapy has demonstrated promising antitumor efficacy in both preclinical and early clinical osteosarcoma studies (Table 5). In a phase I clinical trial involving pet dogs with naturally occurring osteosarcoma, VSV-IFNβ-NIS achieved long-term survival in approximately 35% of treated animals and markedly enhanced the expression of T-cell–related immune genes, indicating reinforced T-cell immunity and improved antitumor responses (37). Adenovirus-based platforms such as Ad5-Δ24-RGDOX have shown potent therapeutic activity, with tumor volume reductions of 30–60% in animal models and long-term survival extended to 35% in canine studies (12, 17). A novel armed OV, CAV2-AU-M3, demonstrated 40–70% decreases in cellular viability in vitro and was engineered to secrete functional anti-PD-1 antibodies, contributing to tumor progression control (14). In addition, combination strategies such as G-CSF plus adenovirus yielded further synergy, achieving tumor-inhibition rates of up to 70% (12).

Table 5

| OV type | Study model | Antitumor outcomes | Safety profile | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSV-IFNβ-NIS | Canine phase I / spontaneous osteosarcoma | ~35% survival improvement; enhanced T-cell response | Well tolerated; no severe toxicities | (37, 73) |

| Ad5-Δ24-RGDOX / ICOVIR-5 | Phase I / animal models | Tumor regression 30–60%; canine long-term survival 35% | Mild–moderate fever; no DLT | (12, 17) |

| HSV-G207 / T-VEC + pembrolizumab | Preclinical / multi-tumor clinical trials | Increased CD8+ T-cell infiltration; improved ICI response | Favorable safety across tumor types | (6, 17) |

| Reovirus / CDV / H-1PV | Preclinical / animal studies | 40–70% cancer cell viability reduction; significant tumor inhibition | High tolerability | (6, 17) |

| CAV2-AU-M3 | In vitro / murine studies | 40–70% tumor suppression; secretes anti-PD-1 antibody | No severe toxicity; high engineering potential | (14, 74) |

| G-CSF + adenovirus | Animal studies | Tumor inhibition 60–70%; increased TIL infiltration | No systemic toxicity observed | (12) |

| Trabectedin + HSV | Animal studies | Higher CR/PR rates versus monotherapy; synergistic inhibition | Good tolerability without increased toxicity | (10) |

Summary of representative OVs, therapeutic efficacy, and safety in osteosarcoma.

This table integrates key efficacy and safety evidence for OV monotherapy and combination strategies in osteosarcoma, covering canine clinical data, animal models, and in vitro studies.

Alongside these encouraging antitumor outcomes, OV therapy has also exhibited a favorable safety profile (Table 5). Across phase I clinical trials in both canines and humans, most adverse effects were limited to mild-to-moderate fever and local inflammatory reactions, without the onset of severe organ toxicities or dose-limiting toxicities (6, 12, 17). The phase I trial of Celyvir (ICOVIR-5/Δ24-RGD; NCT01844661) further confirmed the safety of adenoviral OVs in patients with advanced osteosarcoma, with a subset of individuals achieving disease stabilization or measurable tumor regression (12).

4 Challenges

4.1 Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and model limitations

The tumor microenvironment of osteosarcoma exhibits a strongly immunosuppressive profile, characterized by the predominance of M2-type macrophages, high levels of regulatory T cells (Tregs), excessive PD-L1 expression, and profoundly impaired T-cell and NK-cell functions. As a result, the antitumor efficacy of OV monotherapy is generally limited, with tumor inhibition rates typically below 20% (6, 38). In addition, commonly used immune-deficient and canine models fail to fully recapitulate the complexity of the human immune system, making it difficult to accurately reflect OV-induced immune responses and the dynamic evolution of the tumor microenvironment (6, 39). Sample sizes in these models are often small, which compromises statistical power (17).

4.2 Challenges in viral delivery and intratumoral distribution

Effective OV delivery and distribution within tumors face multiple barriers. During systemic administration, OVs are often neutralized by circulating antibodies, substantially reducing the viral load reaching the tumor site (12, 17). Osteosarcoma cells display significant heterogeneity in their expression of different OV-associated receptors, such as CAR and integrins αvβ3/5, leading to variable infection and lytic efficiency (17, 38). Moreover, the extracellular matrix (ECM) is structurally complex and highly heterogeneous; components such as collagen fibers and hyaluronic acid increase interstitial pressure and form physical barriers that hinder OV diffusion (40). Abnormal and irregular vascularization further limits drug perfusion in certain tumor regions, resulting in uneven viral distribution and suboptimal therapeutic concentrations (6, 41).

4.3 Safety, resistance, and neutralizing antibody responses

The therapeutic window for OVs is relatively narrow. Low-dose regimens often fail to achieve sufficient antitumor responses, whereas high-dose strategies are required for osteosarcoma cells with MDR1-mediated drug resistance, which may trigger systemic inflammatory reactions (10, 42). Additionally, high viral exposure leads to the induction of neutralizing antibodies (nAbs), impairing subsequent OV reinfection of tumor cells and significantly diminishing therapeutic efficacy upon repeated administration (43–46). Notably, pediatric patients are more susceptible to virus-associated immune toxicities, including hepatotoxicity and hematologic complications, necessitating special attention to treatment safety (47). These key challenges, their underlying mechanistic bases, and corresponding potential countermeasures are systematically summarized in Table 6.

Table 6

| Challenge | Mechanistic basis and evidence | Key findings | Strategies | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunosuppressive TME and limitations of preclinical models | High M2-type TAM and Treg infiltration; PD-L1 upregulation; impaired T/NK cell effector function; conventional immune-deficient models fail to recapitulate human immunity | OV monotherapy yields <20% tumor inhibition; combination therapies elevate inhibition to 60–70%; immune-deficient models poorly represent OV-induced immune dynamics | Combine with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, GM-CSF/G-CSF; develop humanized immune mouse models; expand studies using spontaneous canine osteosarcoma | (6, 13, 17, 38, 39, 48) |

| Limited OV delivery and intratumoral distribution | Receptor heterogeneity (e.g., CAR, integrins); ECM barriers (collagen, hyaluronic acid); abnormal vasculature restricts perfusion; dense bone matrix limits penetration | Intratumoral or MSC-based OV delivery increases viral titers 2–5× compared to systemic dosing; necrotic tumor cores remain poorly reached | Personalized OV serotype selection; co-expression of hyaluronidase/collagenase; optimized MSC carriers (chemotaxis engineering, immune-shielding); bone-targeted delivery platforms | (6, 12, 17, 38, 40, 41) |

| Safety concerns, resistance, and neutralizing antibody (nAb) responses | High-dose OVs trigger systemic inflammation/cytokine release; MDR1 upregulation causes viro-resistance; rapid nAb synthesis clears OVs; pediatric patients are more susceptible to toxicity | High-dose regimens induce systemic inflammatory reactions; >50% efficacy loss upon repeat dosing; pediatric hepatotoxicity incidence higher than adults | Serotype-switching strategies; liposomal/polymer encapsulation to evade nAbs; low-dose immunomodulators to balance immune activation; optimized PK/PD-guided dosing schedules | (10, 42, 43, 46, 47) |

Key challenges, mechanistic basis, and potential countermeasures in oncolytic virotherapy for osteosarcoma.

This table summarizes three major barriers in OV therapy for osteosarcoma—TME-induced immune suppression, delivery constraints, and safety/resistance issues—and highlights corresponding mechanistic evidence and counteracting strategies.

5 Discussion

To address immunosuppressive tumor microenvironmental barriers, the next 5–10 years will likely see increasing use of combination therapies including PD-1 inhibitors to restore T-cell function, potentially improving tumor inhibition rates from <20% with OV monotherapy to 60–70% (6, 38). The coordinated administration of G-CSF or GM-CSF is expected to enhance tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) recruitment and functionality (12, 13). Furthermore, targeting macrophage polarization using anti-M2 agents and M1-promoting cytokines may convert the immunologically “cold” tumor phenotype into a “hot” state, thereby strengthening NK- and T-cell-mediated antitumor responses (48). AI-based prediction models will likely support personalized OV selection and virus–host matching to overcome current therapeutic limitations and significantly improve response rates (49–52).

Advances in systemic delivery and intratumoral distribution are anticipated with the development of multiple novel strategies. Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-based carrier systems show high promise by shielding OVs from nAb-mediated clearance and exploiting tumor-homing properties to increase intratumoral viral accumulation by 2–5-fold (12, 17). Local intratumoral administration will further improve viral concentration at target sites (53). Viral engineering approaches, including the insertion of RGD motifs to enhance receptor binding and the overexpression of ECM-degrading enzymes such as hyaluronidase, are expected to facilitate OV penetration through dense matrix structures (6). Additionally, smart nanocarriers combined with AI-guided real-time monitoring will allow dynamic adjustment of treatment strategies and optimization of long-term survival outcomes (54–56).

To mitigate risks of toxicity and viral resistance, future approaches will incorporate AI-assisted dose optimization to maximize efficacy while minimizing systemic inflammatory responses (42). Combination regimens such as OBP-702 with chemotherapy may suppress MDR1-mediated resistance and reduce reliance on high-dose OVs, adding 30–40% tumor suppression benefit (10). AI-based antibody kinetics modeling will aid in optimizing dosing intervals and minimizing nAb accumulation (43, 47), while serotype rotation or liposomal shielding will extend therapeutic windows (46, 57). For pediatric patients, individualized toxicity monitoring supported by AI may help balance efficacy and safety more precisely (45).

Additionally, in cases of skeletal metastases of unknown primary (SMUP) coexisting with osteosarcoma, both diseases may exhibit RANK/RANKL pathway dysregulation and increased bone turnover markers such as CTX and alkaline phosphatase. These findings indicate shared pathophysiological mechanisms in the bone microenvironment that modulate OV diffusion, replication, and immune activation (58). Thus, further mechanistic studies incorporating AI-assisted platforms may accelerate the translation of OV-based precision therapies and enable coordinated management of such comorbid conditions (59).

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

J-WW: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Visualization, Validation, Investigation, Software. XG: Validation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization. J-HL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. XZ: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Panez-Toro I Muñoz-García J Vargas-Franco JW Renodon-Cornière A Heymann M Lézot F et al . Advances in osteosarcoma. Curr Osteoporos Rep. (2023) 21:330–43. doi: 10.1007/s11914-023-00803-9

2

Harris MA Hawkins CJ . Recent and ongoing research into metastatic osteosarcoma treatments. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:3817. doi: 10.3390/ijms23073817

3

Meazza C Scanagatta P . Metastatic osteosarcoma: a challenging multidisciplinary treatment. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. (2016) 16:543–56. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2016.1168697

4

Lian H Zhang J Hou S Ma S Yu J Zhao W et al . Immunotherapy of osteosarcoma based on immune microenvironment modulation. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1498060. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1498060

5

Wen Y Tang F Tu C Hornicek F Duan Z Min L . Immune checkpoints in osteosarcoma: Recent advances and therapeutic potential. Cancer Lett. (2022) 547:215887. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2022.215887

6

Karadimas T Huynh TH Chose C Zervoudakis G Clampitt B Lapp S et al . Oncolytic viral therapy in osteosarcoma. Viruses. (2024) 16:1139. doi: 10.3390/v16071139

7

Ma J Ramachandran M Jin C Quijano-Rubio C Martikainen M Yu D et al . Characterization of virus-mediated immunogenic cancer cell death and the consequences for oncolytic virus-based immunotherapy of cancer. Cell Death Dis. (2020) 11:48. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2236-3

8

Palanivelu L Liu CH Lin LT . Immunogenic cell death: The cornerstone of oncolytic viro-immunotherapy. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:1038226. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1038226

9

Jiang J Wang W Xiang W Jiang L Zhou Q . The phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor ZSTK474 increases the susceptibility of osteosarcoma cells to oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus VSVΔ51 via aggravating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Bioengineered. (2021) 12:11847–57. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.1999372

10

Ringwalt E Currier M Glaspell A Cannon M Chen C Gross A et al . Abstract 1087: Synergistic mechanisms against pediatric bone sarcoma models: Trabectedin enhances oncolytic virotherapy intratumoral spread and antitumor immune activation. Cancer Res. (2024) 84:1087–7. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2024-1087

11

Jhawar SR Wang SJ Thandoni A Bommareddy PK Newman JH Marzo AL et al . Combination oncolytic virus, radiation therapy, and immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment in anti-PD-1-refractory cancer. J Immunother Cancer. (2023) 11:e006780. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2023-006780

12

Morales-Molina A Gambera S Leo A García-Castro J . Combination immunotherapy using G-CSF and oncolytic virotherapy reduces tumor growth in osteosarcoma. J Immunother Cancer. (2021) 9:e001703. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001703

13

Barr TK Jennings VA Taylor A Murby J Caplen NJ Khan J et al . Abstract B049: Oncolytic HSV1716-GMCSF combination strategies to remodel the immunosuppressive osteosarcoma tumor-microenvironment and promote anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Res. (2024) 84:B049–9. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.PEDIATRIC24-B049

14

Khan S Higgins T Lofano IS Agarwal P . Abstract 6551: Exploring oncolytic viral therapy to target osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. (2025) 85:6551–1. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2025-6551

15

Philbrick B Adamson DC . DNX-2401: an investigational drug for the treatment of recurrent glioblastoma. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. (2019) 28:1041–9. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2019.1694000

16

Wang X Shen Y Wan X Hu X Cai W Wu Z et al . Oncolytic virotherapy evolved into the fourth generation as tumor immunotherapy. J Transl Med. (2023) 21:500. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-04360-8

17

Hu M . New horizons in oncolytic virotherapy for osteosarcoma. Theor Natural Sci. (2025). doi: 10.54254/2753-8818/2025.la22601

18

Sinkovics JG Horvath JC . Self-defense of human sarcoma cells against cytolytic lymphoid cells of their host. Eur J Microbiol Immunol (Bp). (2021) 11:44–9. doi: 10.1556/1886.2021.11111

19

Costanzo M De Giglio M Roviello GN . Deciphering the relationship between SARS-coV-2 and cancer. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:7803. doi: 10.3390/ijms24097803

20

Ringwalt EM Currier MA Glaspell AM Chen C Cannon M Cam M et al . Trabectedin promotes oncolytic virus antitumor efficacy, viral gene expression, and immune effector function in models of bone sarcoma. Mol Ther Oncol. (2024) 32:200886. doi: 10.1016/j.omton.2024.200886

21

Li B Zhang C Xu X Shen Q Luo S Hu J . Manipulating the cGAS-STING Axis: advancing innovative strategies for osteosarcoma therapeutics. Front Immunol. (2025) 16:1539396. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1539396

22

O’Donoghue JC Freeman FE . Make it STING: nanotechnological approaches for activating cGAS/STING as an immunomodulatory node in osteosarcoma. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1403538. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1403538

23

Liu K Zan P Li Z Lu H Liu P Zhang L et al . Engineering bimetallic polyphenol for mild photothermal osteosarcoma therapy and immune microenvironment remodeling by activating pyroptosis and cGAS-STING pathway. Adv Healthc Mater. (2024) 13:e2400623. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202400623

24

Armando F Fayyad A Arms S Barthel Y Schaudien D Rohn K et al . Intratumoral canine distemper virus infection inhibits tumor growth by modulation of the tumor microenvironment in a murine xenograft model of canine histiocytic sarcoma. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:3578. doi: 10.3390/ijms22073578

25

Liu K Liao Y Zhou Z Zhang L Jiang Y Lu H et al . Photothermal-triggered immunogenic nanotherapeutics for optimizing osteosarcoma therapy by synergizing innate and adaptive immunity. Biomaterials. (2022) 282:121383. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121383

26

Svensson-Arvelund J Cuadrado-Castano S Pantsulaia G Kim K Aleynick M Hammerich L et al . Expanding cross-presenting dendritic cells enhances oncolytic virotherapy and is critical for long-term anti-tumor immunity. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:7149. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34791-8

27

Yang Y Zhou Y Wang J You Z Watowich SS Kleinerman ES . CD103+ cDC1 dendritic cell vaccine therapy for osteosarcoma lung metastases. Cancers (Basel). (2024) 16:3251. doi: 10.3390/cancers16193251

28

Jneid B Bochnakian A Hoffmann C Delisle F Djacoto E Sirven P et al . Selective STING stimulation in dendritic cells primes antitumor T cell responses. Sci Immunol. (2023) 8:eabn6612. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abn6612

29

Jiang K Zhang Q Fan Y Li J Zhang J Wang W et al . MYC inhibition reprograms tumor immune microenvironment by recruiting T lymphocytes and activating the CD40/CD40L system in osteosarcoma. Cell Death Discov. (2022) 8:117. doi: 10.1038/s41420-022-00923-8

30

Lombardo MS Armando F Marek K Rohn K Baumgärtner W Puff C . Persistence of infectious canine distemper virus in murine xenotransplants of canine histiocytic sarcoma cells after intratumoral application. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:8297. doi: 10.3390/ijms25158297

31

Sezginer O Unver N . Dissection of pro-tumoral macrophage subtypes and immunosuppressive cells participating in M2 polarization. Inflammation Res. (2024) 73:1411–23. doi: 10.1007/s00011-024-01907-3

32

Zhang Q Sioud M . Tumor-associated macrophage subsets: shaping polarization and targeting. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:7493. doi: 10.3390/ijms24087493

33

Boutilier AJ Elsawa SF . Macrophage polarization states in the tumor microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:6995. doi: 10.3390/ijms22136995

34

Gao J Liang Y Wang L . Shaping polarization of tumor-associated macrophages in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:888713. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.888713

35

Liu J Geng X Hou J Wu G . New insights into M1/M2 macrophages: key modulators in cancer progression. Cancer Cell Int. (2021) 21:389. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-02089-2

36

Sibal PA Matsumura S Ichinose T Bustos-Villalobos I Morimoto D Eissa IR et al . STING activator 2’3’-cGAMP enhanced HSV-1-based oncolytic viral therapy. Mol Oncol. (2024) 18:1259–77. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.13603

37

Makielski KM Sarver AL Henson MS Stuebner KM Borgatti A Suksanpaisan L et al . Neoadjuvant systemic oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus is safe and may enhance long-term survivorship in dogs with naturally occurring osteosarcoma. Mol Ther Oncolytics. (2023) 31:100736. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2023.100736

38

Mochizuki Y Tazawa H Demiya K Kure M Kondo H Komatsubara T et al . Telomerase-specific oncolytic immunotherapy for promoting efficacy of PD-1 blockade in osteosarcoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2021) 70:1405–17. doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02774-7

39

Martinez-Velez N Laspidea V Zalacain M Labiano S García-Moure M Puigdelloses M et al . Local treatment of a pediatric osteosarcoma model with a 4-1BBL armed oncolytic adenovirus results in an antitumor effect and leads to immune memory. Mol Cancer Ther. (2022) 21:471–80. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0565

40

Soko GF Kosgei BK Meena SS Ng YJ Liang H Zhang B et al . Extracellular matrix re-normalization to improve cold tumor penetration by oncolytic viruses. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1535647. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1535647

41

Kurozumi K Hardcastle J Thakur R Yang M Christoforidis G Fulci G et al . Effect of tumor microenvironment modulation on the efficacy of oncolytic virus therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2007) 99:1768–81. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm229

42

Sugiu K Tazawa H Hasei J Yamakawa Y Omori T Komatsubara T et al . Oncolytic virotherapy reverses chemoresistance in osteosarcoma by suppressing MDR1 expression. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. (2021) 88:513–24. doi: 10.1007/s00280-021-04310-5

43

Groeneveldt C van den Ende J van Montfoort N . Preexisting immunity: Barrier or bridge to effective oncolytic virus therapy? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. (2023) 70:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2023.01.002

44

Ono R Nishimae F Wakida T Sakurai F Mizuguchi H . Effects of pre-existing anti-adenovirus antibodies on transgene expression levels and therapeutic efficacies of arming oncolytic adenovirus. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:21560. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-26030-3

45

Tsaregorodtseva TS Gubaidullina AA Kayumova BR Shaimardanova AA Issa SS Solovyeva VV et al . Neutralizing antibodies: role in immune response and viral vector based gene therapy. Int J Mol Sci. (2025) 26:5224. doi: 10.3390/ijms26115224

46

Wang Y Huang H Zou H Tian X Hu J Qiu P et al . Liposome encapsulation of oncolytic virus M1 to reduce immunogenicity and immune clearance in vivo. Mol Pharm. (2019) 16:779–85. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b01046

47

Parra-Guillen ZP Trocóniz IF Freshwater T . Role of antidrug antibodies in oncolytic viral therapy: A dynamic modelling approach in cancer patients treated with V937 alone or in combination. Clin Pharmacokinet. (2025) 64:1549–59. doi: 10.1007/s40262-025-01546-9

48

Wang Z Wang Z Li B Wang S Chen T Ye Z . Innate immune cells: A potential and promising cell population for treating osteosarcoma. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:1114. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01114

49

Qiu X Li H Ver Steeg G Godzik A . Advances in AI for protein structure prediction: implications for cancer drug discovery and development. Biomolecules. (2024) 14:339. doi: 10.3390/biom14030339

50

Zhang Z Wei X . Artificial intelligence-assisted selection and efficacy prediction of antineoplastic strategies for precision cancer therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. (2023) 90:57–72. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2023.02.005

51

Chen ZH Lin L Wu CF Li C Xu R Sun Y . Artificial intelligence for assisting cancer diagnosis and treatment in the era of precision medicine. Cancer Commun (Lond). (2021) 41:1100–15. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12215

52

Mao Y Shangguan D Huang Q Xiao L Cao D Zhou H et al . Emerging artificial intelligence-driven precision therapies in tumor drug resistance: recent advances, opportunities, and challenges. Mol Cancer. (2025) 24:123. doi: 10.1186/s12943-025-02321-x

53

Melero I Castañón E Álvarez M Champiat S Marabelle A . Intratumoural administration and tumour tissue targeting of cancer immunotherapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2021) 18:558–76. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00507-y

54

Das KP JC . Nanoparticles and convergence of artificial intelligence for targeted drug delivery for cancer therapy: Current progress and challenges. Front Med Technol. (2022) 4:1067144. doi: 10.3389/fmedt.2022.1067144

55

Hasei J Nakahara R Otsuka Y Nakamura Y Hironari T Kahara N et al . High-quality expert annotations enhance artificial intelligence model accuracy for osteosarcoma X-ray diagnosis. Cancer Sci. (2024) 115:3695–704. doi: 10.1111/cas.16330

56

Moingeon P Kuenemann M Guedj M . Artificial intelligence-enhanced drug design and development: Toward a computational precision medicine. Drug Discov Today. (2022) 27:215–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2021.09.006

57

Elliott NM Kendall BL Dutta S Sarkar D Vant J Thompson J et al . Repeat systemic delivery of cross-neutralization resistant synthetic vesiculoviruses immunomodulates the tumor microenvironment. bioRxiv. (2025). doi: 10.1101/2025.08.01.668184

58

Argentiero A Solimando AG Brunetti O Calabrese A Pantano F Iuliani M et al . Skeletal metastases of unknown primary: biological landscape and clinical overview. Cancers (Basel). (2019) 11:1270. doi: 10.3390/cancers11091270

59

Rodrigues L Wu K Harvey G Post G Miller A Lambert L et al . Abstract 3914: Leveraging canine osteosarcoma as a model to advance precision medicine and targeted therapies in human osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. (2025) 85:3914–4. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2025-3914

60

Kalus P De Munck J Vanbellingen S Carreer L Laeremans T Broos K et al . Oncolytic herpes simplex virus type 1 induces immunogenic cell death resulting in maturation of BDCA-1+ Myeloid dendritic cells. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:4865. doi: 10.3390/ijms23094865

61

Lovatt C Parker AL . Oncolytic viruses and immune checkpoint inhibitors: the “Hot” New power couple. Cancers (Basel). (2023) 15:4178. doi: 10.3390/cancers15164178

62

Mardi A Shirokova AV Mohammed RN Keshavarz A Zekiy AO Thangavelu L et al . Biological causes of immunogenic cancer cell death (ICD) and anti-tumor therapy; Combination of Oncolytic virus-based immunotherapy and CAR T-cell therapy for ICD induction. Cancer Cell Int. (2022) 22:168. doi: 10.1186/s12935-022-02585-z

63

Wu YY Sun TK Chen MS Munir M Liu H . Oncolytic viruses-modulated immunogenic cell death, apoptosis and autophagy linking to virotherapy and cancer immune response. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2023) 13:1142172. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1142172

64

Zhang J Chen J Lin K . Immunogenic cell death-based oncolytic virus therapy: A sharp sword of tumor immunotherapy. Eur J Pharmacol. (2024) 981:176913. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2024.176913

65

Lin J Sun S Zhao K Gao F Wang R Li Q et al . Oncolytic Parapoxvirus induces Gasdermin E-mediated pyroptosis and activates antitumor immunity. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:224. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-35917-2

66

Young E Johnson C Lee A Sweet-Cordero E . Abstract 5370: Tumor-intrinsic cGAS-STING activation promotes anti-tumor inflammatory response in osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. (2024) 84:5370–0. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2024-5370

67

Young EP Johnson CA Lee AG Schott C Sweet-Cordero E . Abstract B036: cGAS-STING activation promotes anti-tumor inflammatory response in osteosarcoma: Implications for tumor microenvironment reprogramming and tumor progression in patients. Cancer Immunol Res. (2023) 11:B036–6. doi: 10.1158/2326-6074.TUMIMM23-B036

68

Xiao H Guo Y Li B Li X Wang Y Han S et al . M2-like tumor-associated macrophage-targeted codelivery of STAT6 inhibitor and IKKβ siRNA induces M2-to-M1 repolarization for cancer immunotherapy with low immune side effects. ACS Cent Sci. (2020) 6:1208–22. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.9b01235

69

Mahmoudi M Taghavi-Farahabadi M Hashemi SM Mousavizadeh K Rezaei N Mojtabavi N . Reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages using exosomes from M1 macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2024) 733:150697. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.150697

70

Ding L Wu L Cao Y Wang H Li D Chen W et al . Modulating tumor-associated macrophage polarization by anti-maRCO mAb exerts anti-osteosarcoma effects through regulating osteosarcoma cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis. J Orthop Surg Res. (2024) 19:453. doi: 10.1186/s13018-024-04950-2

71

Gunassekaran GR Poongkavithai Vadevoo SM Baek MC Lee B . M1 macrophage exosomes engineered to foster M1 polarization and target the IL-4 receptor inhibit tumor growth by reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages into M1-like macrophages. Biomaterials. (2021) 278:121137. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121137

72

Anand N Peh KH Kolesar JM . Macrophage repolarization as a therapeutic strategy for osteosarcoma. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:2858. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032858

73

Léger JL Tai LH . Gaining insights into virotherapy with canine models. Mol Ther Oncolytics. (2023) 31:100754. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2023.100754

74

Ismail AA Patton DJ Higgins TA Sandey M Smith B Agarwal P . Abstract 2339: Exploration of multiple immunotherapy modalities in ostesarcoma. Cancer Res. (2023) 83:2339–9. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2023-2339

Summary

Keywords

oncolytic virus, osteosarcoma, immunogenic cell death, tumor microenvironment, precision medicine

Citation

Wang J-W, Ge X, Liu J-H and Zhang X (2025) Oncolytic virus therapy for osteosarcoma: mechanisms, opportunities, and challenges. Front. Immunol. 16:1724768. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1724768

Received

14 October 2025

Revised

25 November 2025

Accepted

26 November 2025

Published

10 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Antonio Giovanni Solimando, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Italy

Reviewed by

Antonella Argentiero, National Cancer Institute Foundation (IRCCS), Italy

Roger Leng, University of Alberta, Canada

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Wang, Ge, Liu and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaoyu Zhang, 48501616@hebmu.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.