Abstract

Biorepositories, or biobanks, are vital to marine science. Their collections safeguard biological knowledge, enable follow-up studies and reproducibility confirmations, and help extend ecological baselines. Biorepository networks and data portals aggregate catalogs and facilitate open data and material exchange. Such integrations enrich contextual data and support holistic ecosystem-based research and management. In the Arctic, where researchers face vast scales, rapidly changing ecosystems, and limited resampling opportunities, biobanking builds capacities. However, marine and polar biodiversity remains underrepresented in collections. Heterogeneous methodologies and documentation practices hinder data integrations. And open science faces high institutional and cultural barriers. Here, we explore the potential of biobanking to amplify the impact of individual marine studies. We address gaps in standardization and vouchering and suggest improvements to funding and publishing models to incentivize collaboration. We bring together calls for biobanking advancements from diverse perspectives and provide examples of expeditions, databases, specimen collections, and standards. The general analysis is illustrated with two case studies, showcasing the range of the field: inclusion of citizen science observations in cetacean monitoring, and preservation of specimens in environmental microbiome studies. In the former, we suggest strategies for harmonizing data collection for inclusion in global databases. In the latter, we propose cooperative field collection and intact living microbiome (complex microbial community) cryopreservation. Our perspective frames biobanking as a cooperative research strategy, essential to accelerating science under the current climate change-related pressures. We advocate for international investment as the precautionary approach to academic and conservation stewardship of the Arctic biodiversity heritage.

1 Introduction

1.1 Biorepository networks for Arctic marine research

Broadly defined, biorepositories (biobanks) are archival collections of biological data or materials (Bledsoe et al., 2019). Biorepositories include museums, zoos, document archives, and databases (Lotze and Worm, 2009; Moss et al., 2023; Schmidt et al., 2024; Yeates et al., 2016). Cryorepositories (cryobanks) are biorepositories that hold living biological material (e.g., algal cultures, gametes, and tissue samples) in stasis at ultra-low temperatures (Corthals and Desalle, 2005; Martínez-Páramo et al., 2017). Biorepository networks (e.g., Distributed System of Scientific Collections – DiSSCo DiSSCo, GGBN, GBIF, and GenBank) aggregate specimen and data catalogs into shared databases and establish specimen sharing agreements (Collins et al., 2021; Hardisty et al., 2022; Supplementary Table 1; Wu et al., 2017).

As biobanking advances, repositories can address increasingly complex research problems (Jensen et al., 2022). At the same time, Arctic marine ecosystems face accelerated warming, shifts in trophic webs, pollution, and exploitation (Alabia et al., 2023; Cassotta and Goodsite, 2024; Colaço et al., 2022; Ford and Myers, 2008; Lydersen et al., 2014; Post et al., 2021; Qi et al., 2024; Rantanen et al., 2022). With ecosystems changing, returning scientists may not find comparable samples, managers lack data for baselines, and conservationists see populations in decline (Álvarez-Romero et al., 2018; Fontaine et al., 2012). Biorepositories are hedges against biodiversity loss and sources of material for follow-up studies, new investigations, and active conservation, including assisted reproduction (Bolton et al., 2022; González et al., 2018; Meineke et al., 2018; Supplementary Table 1).

1.2 Holistic science: integrated, place-based, and transdisciplinary

Collection integrations (cross-referencing of repository catalogs into meta-databases) support multidisciplinary ecosystem-based management and science, and data aggregators (e.g., GBIF, Seabird) enable investigations across broad spatiotemporal scales (Bernard et al., 2021; Cook et al., 2017; Davies et al., 2021; Schindel and Cook, 2018). For example, eDNA testing, remote sensing, and historical records can complement traditional monitoring efforts (see Section 4.2) (Citta et al., 2018; Cubaynes et al., 2019; Ojaveer et al., 2018; Stefanni et al., 2022; Vachon et al., 2022). Coordinated collecting of specimens, metagenomes, observations, and environmental data also supports genes-to-ecosystems modeling (González et al., 2018; Leigh et al., 2021; Supplementary Table 1). Meta-databases and aggregators work by cross-referencing item-associated metadata (Bakker et al., 2020; González et al., 2018; Supplementary Table 1).

1.3 Cooperative fieldwork: growing capacities in remote locations

Cooperation and crowdsourcing enable data collecting at scale and at amortized project costs (Rölfer et al., 2021). Examples include global collecting drives (Earth Microbiome Project), equipment sharing on expeditions and observation platforms (Tara, FRAM), and opportunistic collecting from commercial vessels (Fadeev et al., 2021; Fischer et al., 2020; Gilbert et al., 2014; Karsenti et al., 2011; Supplementary Table 1; Stephenson, 2021; Thompson et al., 2017; Valsecchi et al., 2021). See Sections 3.2–3 and 5.3 for examples.

Cooperative fieldwork includes sharing across time. Today, archives and museum collections advance modeling and discovery (Bakker et al., 2020; Hornborg et al., 2021; Mecklenburg et al., 2011; Thornton and Scheer, 2012). Tomorrow, restoration programs might rely on the fertility cryocollections established today (Bolton et al., 2022; Mooney et al., 2023; Moss et al., 2023). Participation can also cycle, such as when different “cohorts” of volunteers contribute to separate stages of a citizen science project (Sweeney et al., n.d.).

Citizen science expands options for cooperative research, engaging non-specialist contributors during project planning, field collecting, or data analysis (Burgess et al., 2017; Garcia-Soto and van der Meeren, 2017; Danielson et al., 2022; Johnston et al., 2023). Participants may be external researchers, trained long-term volunteers, or members of the public (Gilbert et al., 2014; Sayigh et al., 2013; Valsecchi et al., 2021).

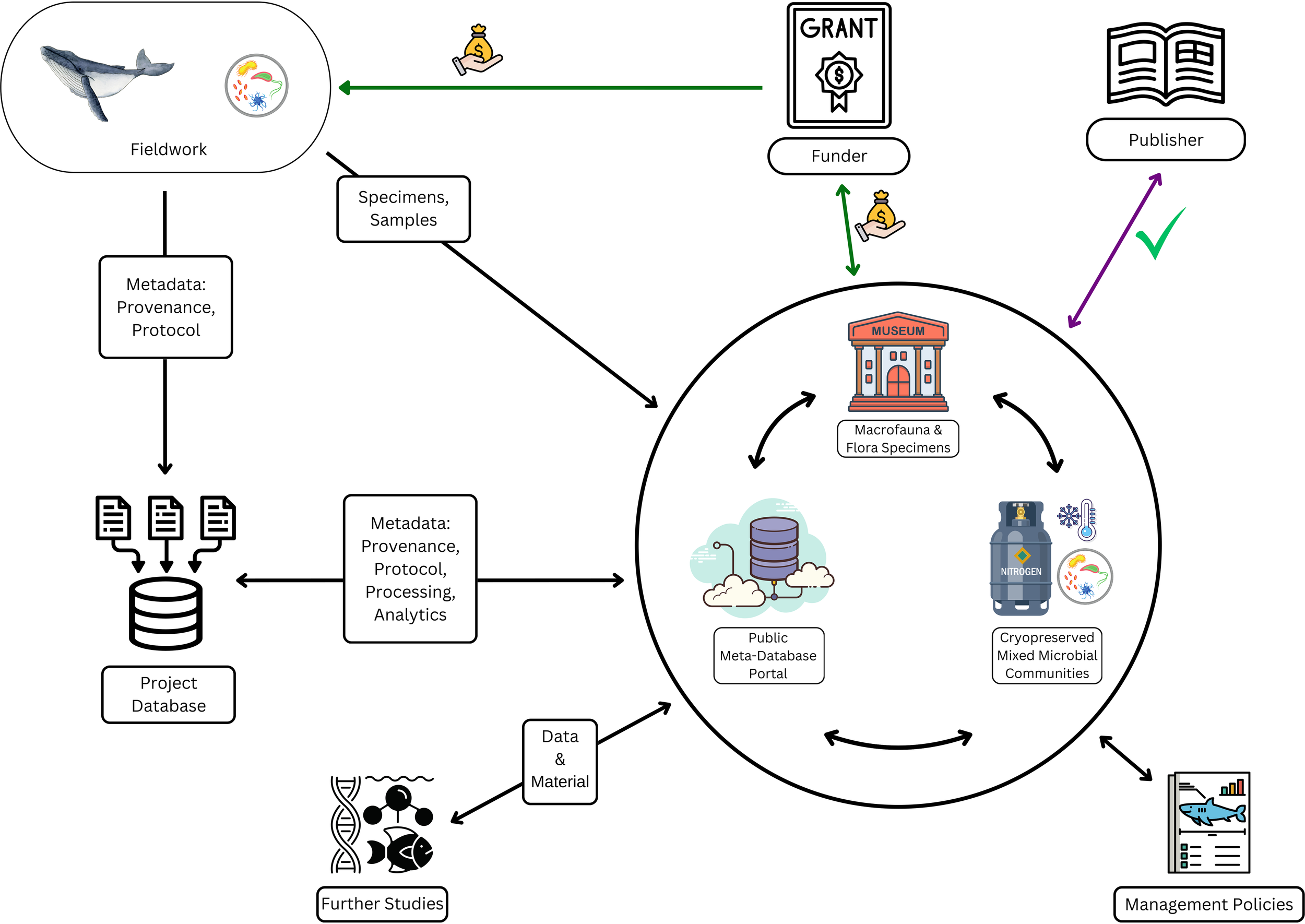

As collecting capacities grow and repository infrastructures develop, Arctic marine science is gaining material for research, restoration, and data-driven stewardship (Figure 1). In Section 2, we discuss the general challenges in collecting, standardizing, and integrating biodiversity data and the financial and cultural barriers to sharing. Building on that discussion, the case study in Section 3 brings into focus the specifics of standardized data collection, as seen through the eyes of a cetologist. Next, Sections 4 and 5 highlight the needs of specimen collections, through the lens of microbiological cryoconservation.

Figure 1

Visualization of our perspective: Fieldwork teams collect samples and/or observations. For microbiome studies, duplicates of the raw samples are sent to biorepositories. Researchers analyze samples and data, and submit to biorepositories all that is applicable of: contextual metadata, raw data, processed data, written analytics code, and sample processing protocols. Global biorepository networks are integrated, so that collections of physical specimens, omic sequences, environmental conditions, published literature, etc. are cross-referenced. (Physical specimens may include: microorganisms and tissues cryopreserved in stasis, microbial cultures, museum specimens, historical records, archaeological records, etc..) Funders and publishers require open data, open protocol/analytics, and open specimens (when feasible) as conditions for funding and publication. Funders and publishers access biorepository portals to verify submissions. For all steps in the cycle, accompanying metadata include information on provenance, chain of custody (traceability), and techniques, protocols and equipment used in sample and/or data collection, curation, storage, and processing. Metadata records also make use of globally unique specimen, data, and project IDs, to support meta-database cross-referencing. Repository-secured biodiversity materials and integrated data are available to future research. Integrated data is accessible to policy makers, managers of marine areas and stocks, and to local stakeholders.

2 Biodiversity biobanking needs and recommendations

2.1 Standardization for cross-referencing, discoverability, traceability, and reproducibility

To integrate catalogs, historically independent databases must adopt common metadata vocabularies and translations (Sterner et al., 2020). However, current standards (e.g., DwC, MIxS) have limited coverage of disciplines and ontologies and insufficient provisions for searchability (machine-readability), and their implementations are lagging due to the difficulties of building global acceptance and of re-annotating existing data. Experimental methodologies are also unharmonized. Consequently, cross-institutional and transdisciplinary integrations, such as associating zoo specimens with museum-based research or field specimens with omics and environmental observations, are rare. Global coordination initiatives must address these gaps (examples in Sections 3.3, 4.2, and 5.2) (Blumberg et al., 2021; Canonico et al., 2019; Colella et al., 2021; Howe et al., 2008; Meyer et al., 2023; Poo et al., 2022; Rölfer et al., 2021; Ryan et al., 2021a; Schuurman and Leszczynski, 2008).

Standardization toward Access and Benefit Sharing traceability is also lacking. Key stakeholders, such as local contributors and Indigenous communities, are inconsistently represented in metadata. We join calls for institutional resources and comprehensive standards of conduct toward inclusive co-creation (Arctic Council, 2019; Collins et al., 2019; Laird and Wynberg, 2018; McCluskey, 2017; Stephenson, 2021; Supplementary Table 1).

2.2 Funding biorepository networks and cooperative fieldwork

Arctic biodiversity is severely underrepresented in collections (Laiolo et al., 2024; Lendemer et al., 2020). To address this, novel funding strategies must spur the adoption of cooperative research (Rölfer et al., 2021; Rosendal et al., 2016). Networks need financing toward collection rescues and backups, standardization, and education and legal compliance services (Bakker et al., 2020; Bledsoe et al., 2022; Boundy-Mills et al., 2020; Goodwin et al., 2017; O’Brien et al., 2022; Supplementary Table 1). Specimen repositories need expansions to accommodate project vouchers alongside type specimens (Colella et al., 2020). (A type specimen identifies a species, whereas multiple voucher specimens provide evidence of that species at a certain time and place). Strategies, such as setting wait intervals for future scientists, can help conserve finite materials (Duarte, 2015).

Researchers need dedicated funding allocations for shipments to biorepositories. Building on recent work by Bentley et al. (2024), we also suggest funder-led matching of applicants to repositories, along with repository services offering guidance on the writing of specimen and data management plans (SMPs and DMPs). Funding for small projects should be prioritized. While large, long-term expeditions are rare, small and local projects already cover wide areas (Gauthier et al., 2021; Rusch et al., 2007; Sunagawa et al., 2020; Supplementary Table 1). With additional funding and standardization training, smaller teams can amplify their impact by contributing source material for future research (Cook et al., 2017; Vangay et al., 2021). We recommend that field teams collect duplicate samples for accessioning (O’Brien et al., 2022). When feasible, cryopreservation on site using portable containers or shipboard equipment is ideal (Bakker et al., 2020; Corrales and Astrin, 2023; Corthals and Desalle, 2005; Gauthier et al., 2021; Nissimov et al., 2022; Tennant et al., 2022; Zuchowicz et al., 2021). Alternatively, DNA/RNA specimens can be fixed in solution at ambient temperature and later cryopreserved by the receiving repository (Brennan and Logares, 2023; Song et al., 2016). More research is needed to optimize techniques (Lee et al., 2019; Menke et al., 2017) (see Sections 3.1–3 and 5.2–3).

While the upfront costs of amplifying biobanking may seem high, they are fractional compared to other infrastructure investments (Dasgupta, 2021; Duarte, 2015; Smith et al., 2014). At the same time, collections minimize redundancies and increase returns on investment into science (Boundy-Mills et al., 2020; González et al., 2018; Schindel and Cook, 2018). Biorepositories guard biodiversity heritage and resources and must be secured long-term through multi-agency and international partnerships (Alivisatos et al., 2015; Collins et al., 2021; Lendemer et al., 2020; McCluskey, 2017).

2.3 Academic culture: incentivizing shared stewardship of samples and data

Academic culture often disincentivizes open science due to “publish or perish” pressures, industry vs. academia tensions, insufficient recognition of collaborative work, and intellectual property concerns. Yet, open data practices bolster replicability, traceability (Becker et al., 2019; Stark, 2018), and inclusivity (Buckner et al., 2021; O’Brien et al., 2022). Transparency empowers integrated marine management and policymaking and informs funding impact metrics. Unfortunately, there is no consensus on implementation and specimen deposits and full data disclosures are rare (Buckner et al., 2021; Colella et al., 2021; Costello et al., 2013; Laird and Wynberg, 2018; Tessnow-von Wysocki and Vadrot, 2020). Smaldino and McElreath (2016) see a gradual institutional shift away from good science and research longevity.

To encourage transparency, institutional and cultural barriers must be lowered. Academic journals must realize coordinated guidelines and verification structures for associating publications with published primary and secondary (derived) data, code, and vouchers. Metadata for sequence records must include machine-readable links to environmental and metagenomic contexts, accessioned vouchers, data, methods and analytics, stakeholders, generated publications and patents, and subsequent downloads and use (Blumberg et al., 2021; Buckner et al., 2021; Laird and Wynberg, 2018; Samuel et al., 2021). Researchers need paid learning and preparation time (Fredston and Lowndes, 2024). Publishers, funders, and institutions must invest in transparency, recognition of interproject collaboration, archiving, and vouchering in researchers’ impact metrics and career assessments (Bernard et al., 2021; Costello et al., 2013; Hardisty et al., 2022; Howe et al., 2008; Vangay et al., 2021). Fears of “getting scooped” and intellectual property considerations can impede compliance. However, open data management planning provides for the coordinated release of proprietary time-sensitive data (Colella et al., 2021; Dubilier et al., 2015).

3 Case study: biobanking of Arctic cetacean data

3.1 Cetacean biorepository networks

On top of the general challenges of Arctic research, gathering data on cetaceans is difficult, given the animals’ long-distance movements and elusive nature (Mann, 1999; Stephenson, 2021). Arctic cetaceans are affected by climate change due to their reliance on affected Arctic ecosystems (van Weelden et al., 2021). A repository of cetacean observations over time can help assess such changes. Large-scale research cruises, such as the long-running North Atlantic Sightings Survey, have collected standardized data for scientific estimates of cetacean abundance (NAMMCO, 2019), though at high financial costs. Regionalized cetacean data collection apps and databases, such as Whale Alert (Conserve.io), Whale Spotter (EarthNC, Inc.), WhaleReport (Ocean Wise), Whale and Dolphin Tracker (Davidson et al., 2014), and MONICET (García et al., 2023), have emerged. Regionalized data are often collected by trained personnel on public platforms such as whale-watching boats (Vinding et al., 2015), cruise ships (Compton et al., 2007), or ferries (Aïssi et al., 2015) to lower costs (see Sections 1.3 and 2.2).

The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) has a public database boasting occurrence data of over 1.8 million animal species, including cetaceans (GBIF), contributed by global partner organizations collecting standardized biodiversity data. Metadata standardization requirements allow GBIF to integrate observations from multiple sources, as discussed in Sections 1.2 and 2.1. The resultant amalgamated catalog can be a rich source of data for scientific research and publication (GBIF). Similarly, the Joint Cetacean Data Programme collates standardized ship-based and aerial cetacean survey data in an open-access database for scientific use (Joint Cetacean Data Programme Information Hub). Recently, machine learning photo-identification database projects such as Flukebook (WildMe, 2024) and Happywhale (2024) began gathering cetacean photos from users, including companies, research organizations, and individual “citizen scientists.”

3.2 Cooperative fieldwork through citizen science

The case of cetacean research showcases both the potential and needs of interdisciplinary collections and citizen science. In the Arctic and worldwide, whale-watching tours and expedition ships can provide valuable platforms for opportunistic data collection (Robbins and Frost, 2009). NOAA encourages this, provided that data are collected with clear scientific or management goals, and those collecting the data are well trained (Pyle, 2007). Citizen science can provide valuable information on species distribution and abundance, as well as on the differences between data collection methods to further determine best practices (McBride-Kebert et al., 2019). Another advantage is that collection can cover greater areas and longer time spans at lower costs than when performed by dedicated researchers. For example, Alessi et al. (2019) found that including citizen science data in their research resulted in the expansion of the distribution map of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) by 22%.

Citizen science is not limited to visual observations. For example, trained volunteers can conduct opportunistic hydroacoustic surveys and eDNA collection for cetacean monitoring from commercial ferries and offshore energy platform service ships, increasing the range and frequency of surveys while minimizing costs (Stephenson, 2021; Valsecchi et al., 2021). Citizen science also extends to data analysis. For example, the Zooniverse web platform helps researchers engage volunteers to process remote sensing data. Accuracy and reliability are ensured by online tutorial training and by requiring agreement between multiple observers before an observation is accepted (Deep Sea Explorers - Zooniverse; Killer Whale Count - Zooniverse; Sayigh et al., 2013). Machine learning algorithms for species identifications and counts in opportunistic observations are trained on such crowdsourced data (Canonico et al., 2019).

3.3 Needs and recommendations

Public observation databases successfully support projects such as Flukebook (WildMe, 2024) and Happywhale (2024). Their machine learning photo-identification algorithms rely mainly on location data and a high-quality photo. However, standardization of citizen science data collection protocols across platforms and regions is needed for integrated cetacean studies (Bowser et al., 2020; Garcia-Soto and van der Meeren, 2017). Firstly, a thorough protocol should be developed for all participants. Suggested basic required data to be collected include species, number of animals, GPS location, date and time, Beaufort sea state, and start and end time of tour (e.g., Bertulli et al., 2018; García et al., 2023). Additional information could include behaviors of interest, such as foraging and jumping. Behavior sampling should include the start and end time of the observation and would be considered ad libitum, meaning that only as much data as possible or the most easily interpreted behaviors are recorded (Mann, 1999).

eBird is a global public observations database with clear standards, and an example of the principles to be applied to cetacean data collection. eBird accepts standardized observations of bird sightings from citizen scientists, researchers, and organizations. It also provides open-access data for species monitoring and conservation management plans (eBird, 2023). To improve accuracy, the eBird observation reporting app has users gauging sightings against filtered lists of local species. Similar workflows would aid observers in cetacean species identification. eBird requires photos or further identifying details for species flagged as rare in the observer’s area (eBird, 2023), and this would also benefit cetacean data. For example, a cetacean monitoring project in the North Atlantic (CETUS) found that once they required photos for species/genus validation, the accuracy of their survey data improved and even led to the addition of a species (Oliveira-Rodrigues et al., 2022).

Each participating region should have a local organization or group of experts overseeing the database. They may be expert volunteers or research institute/NGO staff who have an interest in the data and can manage community submissions. Though the model can be labor-intensive, feasibility is demonstrated by eBird, where expert volunteers verify rare bird sightings in each covered area (eBird, 2023). It is also the model for Happywhale, where organization members verify all submissions (Happywhale, 2024). Whale-watching companies are likely to be quick to adopt such a platform, given that studies on spatial and temporal occurrence and abundance are already conducted using whale-watching boats as research platforms (e.g., Isojunno et al., 2012; Hupman et al., 2014; Vinding et al., 2015; Klotz et al., 2017; García et al., 2023).

Smartphone technology makes data collection relatively easy. Smartphone apps can present dynamic training and observation workflows, collect location data and photos, and assist in identifications. Apps may also help implement Aarhus Convention-mandated reporting (Garcia-Soto and van der Meeren, 2017). Networked portals are well-positioned to develop such tools (Chandler et al., 2017). Given their value to science and conservation, funding should be made available for standardized, collaborative, open-access citizen science platforms to be created, managed, and included in biorepository networks.

4 Case study: biobanking of Arctic marine microbiomes

4.1 Microbial biorepository networks: museums, universities, and microbial domain Biological Resource Centers (mBRCs)

Arctic oceans are rich in microbial biodiversity hotspots (Aalto et al., 2022; Gilbertson et al., 2022; Morganti et al., 2022). The microorganisms’ adaptations to their extreme habitats are vital to ecosystem functions and have inspired discoveries in biotechnologies, medicine, and evolutionary modeling (Bruno et al., 2019; Brennan and Logares, 2023; Dorrell et al., 2023; Galand et al., 2009; Gregory et al., 2019; Suttle, 2007). However, Arctic microbes are under threat, with studies showing slow community recovery times and permanent shifts in response to environmental changes, and emphasizing that scientific preservation efforts are crucial to future research (Amend et al., 2019; Gilbertson et al., 2022; Ibáñez et al., 2023; Lofgren and Stajich, 2021).

4.2 Holistic science: integrated monitoring, restoration, and innovation

Because microbial communities participate in ecosystem processes, their compositions can signal ecological change. Thus, microbial monitoring can complement traditional ecological assessments (see Section 1.2). In the Arctic, autonomous observatories monitor microbial DNA year-round to establish management baselines (Canonico et al., 2019; Goodwin et al., 2017; Wietz et al., 2021; Supplementary Table 1).

Similarly, animal and plant microbiomes can be specific to host species, and can reflect life histories, host fitness, and adaptive responses to changing conditions. With further study, host-associated microbiomes may give new options for non-invasive monitoring (Apprill et al., 2017; Franz et al., 2022; Glaeser et al., 2022; Hanning and Diaz-Sanchez, 2015; Osman and Weinnig, 2022; Sehnal et al., 2021; Sanders et al., 2015; Wilkins et al., 2019). Conversely, healthy (fitness-supporting) host microbiomes are integral to the success of active in situ restoration and ex situ (captive) breeding efforts (Hahn et al., 2022; Lynch and Hsiao, 2019). Microbial management, such as through transplantation, probiotics, prebiotics, and captive environment engineering, may prove vital, and microbiota preservation must be included in restoration planning (Hauffe and Barelli, 2019; Peixoto et al., 2022; West et al., 2019).

With references disappearing in the wild, biobanked microbiomes may become reservoirs of material for future research, industries, and active restoration of biodiversity.

5 Biobanking marine microbiomes—needs and recommendations

5.1 Sequencing is limited; biorepositories are missing microbiomes

Most microbiome studies are limited to taxonomic profiling of prokaryotic community compositions (Flaviani et al., 2018; Knight et al., 2018). Advanced omics technologies are less accessible and have their own limitations, especially for low-biomass Arctic marine samples (Breitwieser et al., 2019; Edwards et al., 2020; Thukral et al., 2023). Microbiome investigations can miss intraspecific variations (microdiversity), organismal adaptations (functional diversity), interdomain and cell-to-cell interactions, and epigenetic responses (Gregory et al., 2019; Manter et al., 2017; Rotter et al., 2021). For Arctic microbiomes, the dearth of reference data is a particular challenge (Edwards et al., 2020). Future technologies will enable deeper investigations and serendipitous discoveries. However, context is lost without the ability to re-examine the original sources (Astrin et al., 2013; Eirin-Lopez and Putnam, 2019; Heylen et al., 2012). Researchers need vouchers of intact whole microbiomes, such as source substrates (Edwards et al., 2020). Multistrain vouchers are also needed in climate studies, aquaculture, and biotechnological and pharmaceutical research, where microbial consortia can outperform monocultures as model systems (Biteen et al., 2016; Borges et al., 2021; Hoag, 2009; Kerckhof et al., 2014>; Wolf et al., 2019).

Despite their importance, environmental microbiome vouchers are rare. Collections are dominated by commercially relevant bacterial and algal monocultures (Nissimov et al., 2022; Prakash et al., 2013; Ryan et al., 2021b). Conservation agendas must include microbial biodiversity, in all domains. We join calls for international initiatives to expand cryocollections and include whole microbiomes (Dubilier et al., 2015; Lofgren and Stajich, 2021; Ryan et al., 2021b). Such collections would capture biodiversity better than traditional methods alone, and enable repeat examinations (Rain-Franco et al., 2021; Vekeman and Heylen, 2015). Priority must be given to microbiomes from unique, understudied, and endangered environments and hosts, such as those in the Arctic (Colella et al., 2020). Non-prokaryotic material is essential to community and ecosystem functions, and needs focus (Cockell and Jones, 2009; Danovaro et al., 2011).

5.2 Extending metadata standards and optimizing collection and cryopreservation

To integrate microbial records with other databases (see Section 2.1), microbiological data need references to the source contexts (originating microbiomes and environments) (Goodwin et al., 2017; Lobanov et al., 2022; Sehnal et al., 2021). Commercial bioprospecting potential also demands comprehensive compliance-related tracking of contributors and beneficiaries (Fritze, 2009; Laird and Wynberg, 2018). Extensions to existing standards are in discussion (Ryan et al., 2021a).

Reliable comparisons of results across studies also require standardization of techniques (Osman and Weinnig, 2022; Samuel et al., 2021; Supplementary Table 1). Many microbial collections use cryopreservation to save storage space, avoid subculturing-associated contamination and genetic drift, and accommodate non-culturable or unstable material (Becker et al., 2019; Boundy-Mills et al., 2020; Nakanishi et al., 2012; Nissimov et al., 2022; Vekeman and Heylen, 2015). However, there are no standard methodologies for environmental microbiomes or for many of the component viral, prokaryotic, and eukaryotic taxa, and marine microorganisms are not prioritized in research (Kerckhof et al., 2014; Lofgren and Stajich, 2021; Nissimov et al., 2022; Prakash et al., 2020). Notably, the new MICROBE EU initiative seeks to expand scientific focus. Storage temperatures can vary, with many smaller collections using −80°C electric freezers. While −80°C is sufficient for up to 5 years, −196°C in a liquid nitrogen facility is best practice for long-term storage (Corrales and Astrin, 2023; Heylen et al., 2012). This is especially true for Arctic marine psychrophiles, which may retain some activity at ultra-low temperatures (Junge et al., 2006). Investment is needed toward collection transfers to liquid nitrogen facilities (Becker et al., 2019; Manter et al., 2017; Nissimov et al., 2022). Standardized live/dead analysis techniques would add value by giving insight into the community states at the time of collection. One such technique is the collection of a duplicate aliquot, pretreated with the propidium monoazide (PMA) permanent dye to exclude relic, contaminant, and other exDNA from downstream amplification (Burot et al., 2021; Emerson et al., 2017; Yun et al., 2023; Supplementary Table 1). It may be of particular interest in Arctic marine microbiology, where low biomass and contamination are significant challenges. Further research is needed, including knowledge-sharing collaborations with medical and agricultural cryopreservation programs and innovative non-profits (Bolton et al., 2022; Hagedorn et al., 2019; Martiny et al., 2020; Ryan et al., 2021b; Supplementary Table 1).

Despite its technical challenges, cryopreservation is imperative as the precautionary approach, as damaged specimens can still provide genetic material toward more traditional studies (De Vero et al., 2019; Microbe, 2023; Prakash et al., 2013, 2020; Ryan et al., 2021b; Supplementary Table 1).

5.3 Funding cooperative fieldwork: novel and opportunistic samples and evolved expectations

In addition to the capacity and interoperability needs described in Section 2.2, cryocollections need funding to broaden accepted biodiversity (Debode et al., 2024; Lofgren and Stajich, 2021; Ryan et al., 2023). Many mBRCs (e.g., ECCO, MIRRI, WFCC) are partially self-funding and need independent financing for conservation-focused growth (McCluskey, 2017; Rosendal et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2014). Museums and academic centers need funding to process and store novel material and share collection backups. Fundamentally, specimens obtained with public funds should not be wasted or lost (Cary and Fierer, 2014; Costello et al., 2013; Dubilier et al., 2015).

Colella et al. (2020) suggest establishing collaborative sampling networks. An expansion to the principle would be the creation of “matchmaking” organizers to connect field teams with projects that need access. For example, Project A has limited field access. They request to be matched with teams working in the target area. Project B already has a fieldwork grant, and agrees to also collect samples for Project A. The organizer assists both teams with paperwork and allocates extra funding to Project B. In contrast to collaborative research, in this cooperative model the teams are matched after they receive their individual project grants. They are working on separate topics, much as teams sharing an expedition ship would.

Grants for teams to collect specimens or data on behalf of other projects are not the current norm. However, given the benefits of wider collections and inclusive access and the costliness of Arctic research, new funding paradigms may prevent future opportunity losses (Mallory et al., 2018). We also propose a new type of publication impact metric, to acknowledge major contributors who collect data without participating in the analysis. This particular acknowledgment would confer credit without the complication of meeting co-authorship standards (Buckner et al., 2021; Hardisty et al., 2022; Vangay et al., 2021). See Sections 2.2–3 for a generalized discussion.

6 Conclusion

As Arctic ecosystems destabilize, researchers are rushing to capture biodiversity across expansive spatio-temporal scales. Cooperative science is evolving, expanding access and reach for scientists.

Biorepository networks are essential to this effort, and are expanding catalogs and capabilities. However, biobanking is lagging behind the pace of change in the Arctic. Modernized funding, publishing, and academic practices are called for. Repositories require permanent funding through multi-agency multinational alliances, and researchers need new grant budget categories. Current academic realities discourage co-creation, and publishers, employers, and funders must drive a cultural shift by updating incentivization and assistance models.

The case of citizen science-led cetacean monitoring demonstrates the technological conditions of coordinated observing through biorepository networks. Acceptance of collection and documentation standards will help harmonize records between studies and environmental datasets. Data quality can be ensured with oversight of annotations by regional experts. The case of microbiome cryopreservation highlights the need for holistic science and specimen preservation. Global cryocollections hold little of Arctic marine biodiversity, and few specimens are shared across projects or reused. Expanding public cryocollections with environmental microbiomes will help secure a legacy for the next generation and maximize scientific opportunities.

With the environmental challenges coming in the next decades, scientists will be increasingly working from biorepositories. Biobanking is essential to improving the representation of Arctic marine resources in research and is a precautionary approach to the problem of biodiversity loss. Costs of inaction are high.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DC: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CB: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Open-access publication fees were covered by the state of Bremen, Germany. The University of Iceland Student Fund (Ice: Stúdentasjóður) has provided a grant to attend the ICYMARE conference.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Abigail Hils for their invaluable assistance in the editing and proofreading of this manuscript, with keen attention to detail and commitment to clarity. We also deeply appreciate Ted Brengle for his kind support and feedback on language, flow, and accessibility. We sincerely thank our editor, Dr. Simon Jungblut, for his kind guidance in explaining the process and practice, and our two anonymous reviewers and Drs. Paredes and Savoie for their time, expertise, and direction. Finally, we would like to thank the staff directing the review process for the support and structure offered during this journey.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2024.1385797/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1Glossary, lists of expeditions, observatories, repositories and networks, and examples of laboratory, legal, and metadata standards and findings.

References

1

Aalto N. J. Schweitzer H. D. Krsmanovic S. Campbell K. Bernstein H. C. (2022). Diversity and selection of surface marine microbiomes in the atlantic-influenced arctic. Front. Microbiol.13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.892634

2

Aïssi M. Arcangeli A. Crosti R. Daly Yahia M. N. Loussaief B. Moulins A. et al . (2015). Cetacean occurrence and spatial distribution in the central Mediterranean Sea using ferries as platform of observation. Russ J. Mar. Biol.41, 343–350. doi: 10.1134/S1063074015050028

3

Alabia I. D. García Molinos J. Hirata T. Mueter F. J. David C. L. (2023). Pan-Arctic marine biodiversity and species co-occurrence patterns under recent climate. Sci. Rep.13, 4076. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-30943-y

4

Alessi J. Bruccoleri F. Cafaro V. (2019). How citizens can encourage scientific research: The case study of bottlenose dolphins monitoring. Ocean Coast. Manage.167, 9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.09.018

5

Alivisatos A. P. Blaser M. J. Brodie E. L. Chun M. Dangl J. L. Donohue T. J. et al . (2015). A unified initiative to harness Earth’s microbiomes. Science350, 507–508. doi: 10.1126/science.aac8480

6

Álvarez-Romero J. G. Mills M. Adams V. M. Gurney G. G. Pressey R. L. Weeks R. et al . (2018). Research advances and gaps in marine planning: towards a global database in systematic conservation planning. Biol. Conserv.227, 369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.06.027

7

Amend A. Burgaud G. Cunliffe M. Edgcomb V. P. Ettinger C. L. Gutiérrez M. H. et al . (2019). Fungi in the marine environment: open questions and unsolved problems. mBio10, e01189–e01118. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01189-18

8

Apprill A. Miller C. A. Moore M. J. Durban J. W. Fearnbach H. Barrett-Lennard L. G. (2017). Extensive core microbiome in drone-captured whale blow supports a framework for health monitoring. mSystems2, e00119–e00117. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00119-17

9

Arctic Council (2019). PAME: policy: meaningful engagement of indigenous peoples and local communities in marine activities. Available online at: https://pame.is/document-library/pame-reports-new/pame-ministerial-deliverables/2019-11th-arctic-council-ministerial-meeting-rovaniemi-Finland/425-meaningful-engagement-of-indigenous-peoples-and-local-communities-in-marine-activities-mema-part-ii-findings-for-policy-makers/file (Accessed December 1, 2023).

10

Astrin J. Zhou X. Misof B. (2013). The importance of biobanking in molecular taxonomy, with proposed definitions for vouchers in a molecular context. ZooKeys365, 67–70. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.365.5875

11

Bakker F. T. Antonelli A. Clarke J. A. Cook J. A. Edwards S. V. Ericson P. G. P. et al . (2020). The Global Museum: Natural history collections and the future of evolutionary science and public education. PeerJ8, e8225. doi: 10.7717/peerj.8225

12

Becker P. Bosschaerts M. Chaerle P. Daniel H.-M. Hellemans A. Olbrechts A. et al . (2019). Public microbial resource centers: key hubs for findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) microorganisms and genetic materials. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.85, e01444–e01419. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01444-19

13

Bentley A. Thiers B. Moser W. E. Watkins-Colwell G. J. Zimkus B. M. Monfils A. K. et al . (2024). Community action: planning for specimen management in funding proposals. BioScience. 74, 435–439. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biae032

14

Bernard A. Rodrigues A. S. L. Cazalis V. Grémillet D. (2021). Toward a global strategy for seabird tracking. Conserv. Lett.14, e12804. doi: 10.1111/conl.12804

15

Bertulli C. G. Guéry L. McGinty N. Suzuki A. Brannan N. Marques T. et al . (2018). Capture-recapture abundance and survival estimates of three cetacean species in Icelandic coastal waters using trained scientist-volunteers. J. Sea Res.131, 22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2017.10.001

16

Biteen J. S. Blainey P. C. Cardon Z. G. Chun M. Church G. M. Dorrestein P. C. et al . (2016). Tools for the microbiome: nano and beyond. ACS Nano10, 6–37. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07826

17

Bledsoe E. K. Burant J. B. Higino G. T. Roche D. G. Binning S. A. Finlay K. et al . (2022). Data rescue: saving environmental data from extinction. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci.289, 20220938. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2022.0938

18

Bledsoe M. J. Watson P. H. Hewitt R. E. Catchpoole D. R. Grizzle W. E. (2019). Biobank: what’s in a name? Biopreservation Biobanking17, 204–208. doi: 10.1089/bio.2019.29053.mjb

19

Blumberg K. L. Ponsero A. J. Bomhoff M. Wood-Charlson E. M. DeLong E. F. Hurwitz B. L. (2021). Ontology-enriched specifications enabling findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable marine metagenomic datasets in cyberinfrastructure systems. Frontiers in Microbiology12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.765268.

20

Bolton R. L. Mooney A. Pettit M. T. Bolton A. E. Morgan L. Drake G. J. et al . (2022). Resurrecting biodiversity: advanced assisted reproductive technologies and biobanking. Reprod. Fertility3, R121–R146. doi: 10.1530/RAF-22-0005

21

Borges N. Keller-Costa T. Sanches-Fernandes G. M. M. Louvado A. Gomes N. C. M. Costa R. (2021). Bacteriome structure, function, and probiotics in fish larviculture: the good, the bad, and the gaps. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci.9, 423–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-062920-113114

22

Boundy-Mills K. McCluskey K. Elia P. Glaeser J. A. Lindner D. L. Nobles D. R. et al . (2020). Preserving US microbe collections sparks future discoveries. J. Appl. Microbiol.129, 162–174. doi: 10.1111/jam.14525

23

Bowser A. Cooper C. de Sherbinin A. Wiggins A. Brenton P. Chuang T.-R. et al . (2020). Still in need of norms: the state of the data in citizen science. Citizen Science: Theory Pract.5 (1): 18, 1–16. doi: 10.5334/cstp.303

24

Breitwieser F. P. Lu J. Salzberg S. L. (2019). A review of methods and databases for metagenomic classification and assembly. Briefings Bioinf.20, 1125–1136. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx120

25

Brennan G. L. Logares R. (2023). Tracking contemporary microbial evolution in a changing ocean. Trends Microbiol.31, 336–345. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2022.09.001

26

Bruno S. Coppola D. di Prisco G. Giordano D. Verde C. (2019). Enzymes from marine polar regions and their biotechnological applications. Mar. Drugs17, 544. doi: 10.3390/md17100544

27

Buckner J. C. Sanders R. C. Faircloth B. C. Chakrabarty P. (2021). The critical importance of vouchers in genomics. eLife10, e68264. doi: 10.7554/eLife.68264

28

Burgess H. K. DeBey L. B. Froehlich H. E. Schmidt N. Theobald E. J. Ettinger A. K. et al . (2017). The science of citizen science: Exploring barriers to use as a primary research tool. Biol. Conserv.208, 113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.014

29

Burot C. Amiraux R. Bonin P. Guasco S. Babin M. Joux F. et al . (2021). Viability and stress state of bacteria associated with primary production or zooplankton-derived suspended particulate matter in summer along a transect in Baffin Bay (Arctic Ocean). Sci. Total Environ.770, 145252. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145252

30

Canonico G. Buttigieg P. L. Montes E. Muller-Karger F. E. Stepien C. Wright D. et al . (2019). Global observational needs and resources for marine biodiversity. Front. Mar. Sci.6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00367

31

Cary S. C. Fierer N. (2014). The importance of sample archiving in microbial ecology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.12, 789–790. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3382

32

Cassotta S. Goodsite M. (2024). Deep-seabed mining: an environmental concern and a holistic social environmental justice issue. Front. Ocean Sustainability2. doi: 10.3389/focsu.2024.1355965

33

Chandler M. See L. Copas K. Bonde A. M. Z. López B. C. Danielsen F. et al . (2017). Contribution of citizen science towards international biodiversity monitoring. Biol. Conserv.213, 280–294. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.09.004

34

Citta J. J. Lowry L. F. Quakenbush L. T. Kelly B. P. Fischbach A. S. London J. M. et al . (2018). A multi-species synthesis of satellite telemetry data in the Pacific Arctic, (1987–2015): Overlap of marine mammal distributions and core use areas. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Topical Stud. Oceanography152, 132–153. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2018.02.006

35

Cockell C. S. Jones H. L. (2009). Advancing the case for microbial conservation. Oryx43 (4), 520–526. doi: 10.1017/S0030605309990111

36

Colaço A. Rapp H. T. Campanyà-Llovet N. Pham C. K. (2022). Bottom trawling in sponge grounds of the Barents Sea (Arctic Ocean): A functional diversity approach. Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanographic Res. Papers183, 103742. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2022.103742

37

Colella J. P. Stephens R. B. Campbell M. L. Kohli B. A. Parsons D. J. Mclean B. S. (2021). The open-specimen movement. BioScience71, 405–414. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biaa146

38

Colella J. P. Talbot S. L. Brochmann C. Taylor E. B. Hoberg E. P. Cook J. A. (2020). Conservation genomics in a changing arctic. Trends Ecol. Evol.35, 149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2019.09.008

39

Collins J. E. Harden-Davies H. Jaspars M. Thiele T. Vanagt T. Huys I. (2019). Inclusive innovation: Enhancing global participation in and benefit sharing linked to the utilization of marine genetic resources from areas beyond national jurisdiction. Mar. Policy109, 103696. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103696

40

Collins J. E. Rabone M. Vanagt T. Amon D. J. Gobin J. Huys I. (2021). Strengthening the global network for sharing of marine biological collections: recommendations for a new agreement for biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction. ICES J. Mar. Sci.78, 305–314. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsaa227

41

Compton R. Banks A. Goodwin L. Hooker S. K. (2007). Pilot cetacean survey of the sub-Arctic North Atlantic utilizing a cruise-ship platform. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom87, 321–325. doi: 10.1017/S0025315407054781

42

Cook J. A. Galbreath K. E. Bell K. C. Campbell M. L. Carrière S. Colella J. P. et al . (2017). The Beringian Coevolution Project: Holistic collections of mammals and associated parasites reveal novel perspectives on evolutionary and environmental change in the North. Arctic Sci.3, 585–617. doi: 10.1139/as-2016-0042

43

Corrales C. Astrin J. J. (Eds.) (2023). Biodiversity Biobanking – a Handbook on Protocols and Practices. (12, Prof. Georgi Zlatarski Str. 12 1111 Sofia, Bulgaria: Pensoft, Advanced Books). Available at: https://ab.pensoft.net/article/101876/ (Accessed April 6, 2023).

44

Corthals A. Desalle R. (2005). An application of tissue and DNA banking for genomics and conservation: the ambrose monell cryo-collection (AMCC). Systematic Biol.54, 819–823. doi: 10.1080/10635150590950353

45

Costello M. J. Michener W. K. Gahegan M. Zhang Z.-Q. Bourne P. E. (2013). Biodiversity data should be published, cited, and peer reviewed. Trends Ecol. Evol.28, 454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2013.05.002

46

Cubaynes H. C. Fretwell P. T. Bamford C. Gerrish L. Jackson J. A. (2019). Whales from space: Four mysticete species described using new VHR satellite imagery. Mar. Mammal Sci.35, 466–491. doi: 10.1111/mms.12544

47

Danielson S. L. Grebmeier J. M. Iken K. Berchok C. Britt L. Dunton K. H. et al . (2022). Monitoring alaskan arctic shelf ecosystems through collaborative observation networks. Oceanography35, 198–209. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2022.119

48

Danovaro R. Corinaldesi C. Dell’Anno A. Fuhrman J. A. Middelburg J. J. Noble R. T. et al . (2011). Marine viruses and global climate change. FEMS Microbiol. Rev.35, 993–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00258.x

49

Dasgupta P. (2021). The economics of biodiversity: The Dasgupta review (London: HM Treasury). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/final-report-the-economics-of-biodiversity-the-dasgupta-review (Accessed January, 12, 2024).

50

Davidson E. Currie J. J. Stack S. H. Kaufman G. D. Martinez E. (2014). Whale and dolphin tracker, a web-application for recording cetacean sighting data in real-time: Example using opportunistic observations reported in 2013 from tour vessels off Maui, Hawai`i Vol. 65b (Report to the International Whaling Commission), 1–17.

51

Davies T. E. Carneiro A. P. B. Tarzia M. Wakefield E. Hennicke J. C. Frederiksen M. et al . (2021). Multispecies tracking reveals a major seabird hotspot in the North Atlantic. Conserv. Lett.14, e12824. doi: 10.1111/conl.12824

52

Debode F. Caulier S. Demeter S. Dubois B. Gelhay V. Hulin J. et al . (2024). Roadmap for the integration of environmental microbiomes in risk assessments under EFSA’s remit. EFS321, 8602E. doi: 10.2903/sp.efsa.2024.EN-8602

53

Deep Sea Explorers - Zooniverse . Available online at: https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/reinforce/deep-sea-explorers (Accessed January 29, 2024).

54

De Vero L. Boniotti M. B. Budroni M. Buzzini P. Cassanelli S. Comunian R. et al . (2019). Preservation, characterization and exploitation of microbial biodiversity: the perspective of the Italian network of culture collections. Microorganisms7, 685. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7120685

55

Distributed System of Scientific Collections – DiSSCo DiSSCo. Available online at: https://www.dissco.eu/ (Accessed May 30, 2024).

56

Dorrell R. G. Kuo A. Füssy Z. Richardson E. H. Salamov A. Zarevski N. et al . (2023). Convergent evolution and horizontal gene transfer in Arctic Ocean microalgae. Life Sci. Alliance6, e202201833. doi: 10.26508/lsa.202201833

57

Duarte C. M. (2015). Seafaring in the 21St century: the malaspina 2010 circumnavigation expedition. Limnology Oceanography Bull.24, 11–14. doi: 10.1002/lob.10008

58

Dubilier N. McFall-Ngai M. Zhao L. (2015). Microbiology: Create a global microbiome effort. Nature526, 631–634. doi: 10.1038/526631a

59

eBird (2023). The eBird Review Process. Available online at: https://support.ebird.org/en/support/solutions/articles/48000795278-the-ebird-review-process (Accessed February 1, 2024).

60

Edwards A. Cameron K. A. Cook J. M. Debbonaire A. R. Furness E. Hay M. C. et al . (2020). Microbial genomics amidst the Arctic crisis. Microb. Gen.6, e000375. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000375

61

Eirin-Lopez J. M. Putnam H. M. (2019). Marine environmental epigenetics. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci.11, 335–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010318-095114

62

Emerson J. B. Adams R. I. Román C. M. B. Brooks B. Coil D. A. Dahlhausen K. et al . (2017). Schrödinger’s microbes: Tools for distinguishing the living from the dead in microbial ecosystems. Microbiome5, 86. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0285-3

63

Fadeev E. Cardozo-Mino M. G. Rapp J. Z. Bienhold C. Salter I. Salman-Carvalho V. et al . (2021). Comparison of two 16S rRNA primers (V3–V4 and V4–V5) for studies of arctic microbial communities. Front. Microbiol.12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.637526

64

Fischer P. Brix H. Baschek B. Kraberg A. Brand M. Cisewski B. et al . (2020). Operating cabled underwater observatories in rough shelf-sea environments: A technological challenge. Front. Mar. Sci.7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00551

65

Flaviani F. Schroeder D. C. Lebret K. Balestreri C. Highfield A. C. Schroeder J. L. et al . (2018). Distinct oceanic microbiomes from viruses to protists located near the antarctic circumpolar current. Front. Microbiol.9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01474

66

Fontaine B. Perrard A. Bouchet P. (2012). 21 years of shelf life between discovery and description of new species. Curr. Biol.22, R943–R944. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.029

67

Ford J. S. Myers R. A. (2008). A global assessment of salmon aquaculture impacts on wild salmonids. PloS Biol.6, e33. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060033

68

Franz M. Whyte L. Atwood T. C. Laidre K. L. Roy D. Watson S. E. et al . (2022). Distinct gut microbiomes in two polar bear subpopulations inhabiting different sea ice ecoregions. Sci. Rep.12, 522. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-04340-2

69

Fredston A. L. Lowndes J. S. S. (2024). Welcoming more participation in open data science for the oceans. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci.16, 537–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-041723-094741

70

Fritze D. (2009). A common basis for facilitated legitimate exchange of biological materials proposed by the European Culture Collections’ Organisation. International Journal of the Commons, 4 (1), 507–527. doi: 10.18352/ijc.153

71

Galand P. E. Casamayor E. O. Kirchman D. L. Lovejoy C. (2009). Ecology of the rare microbial biosphere of the Arctic Ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.106, 22427–22432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908284106

72

García L. G. Fernández M. Azevedo J. M. N. (2023). MONICET: The Azores whale watching contribution to cetacean monitoring. Biodiversity Data J.11, e106991. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.11.e106991

73

Garcia-Soto C. van der Meeren G. I. (2017). Advancing citizen science for coastal and ocean research. Eur. Mar. Board. Available at: https://imr.brage.unit.no/imr-xmlui/handle/11250/2476796 (Accessed May 24, 2024).

74

Gauthier A. E. Chandler C. E. Poli V. Gardner F. M. Tekiau A. Smith R. et al . (2021). Deep-sea microbes as tools to refine the rules of innate immune pattern recognition. Sci. Immunol.6, eabe0531. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abe0531

75

GBIF . Available online at: https://www.gbif.org/ (Accessed June 14, 2024).

76

Gilbert J. A. Jansson J. K. Knight R. (2014). The Earth Microbiome project: Successes and aspirations. BMC Biol.12, 69. doi: 10.1186/s12915-014-0069-1

77

Gilbertson R. Langan E. Mock T. (2022). Diatoms and their microbiomes in complex and changing polar oceans. Front. Microbiol.13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.786764

78

Glaeser S. P. Silva L. M. R. Prieto R. Silva M. A. Franco A. Kämpfer P. et al . (2022). A Preliminary Comparison on Faecal Microbiomes of Free-Ranging Large Baleen (Balaenoptera musculus, B. physalus, B. borealis) and Toothed (Physeter macrocephalus) Whales. Microb. Ecol.83, 18–33. doi: 10.1007/s00248-021-01729-4

79

González Á.F. Rodríguez H. Outeiriño L. Vello C. Larsson C. Pascual S. (2018). A biobanking platform for fish-borne zoonotic parasites: a traceable system to preserve samples, data and money. Fisheries Res.202, 29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2017.03.014

80

Goodwin K. D. Thompson L. R. Duarte B. Kahlke T. Thompson A. R. Marques J. C. et al . (2017). DNA sequencing as a tool to monitor marine ecological status. Front. Mar. Sci.4. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00107

81

Gregory A. C. Zayed A. A. Conceição-Neto N. Temperton B. Bolduc B. Alberti A. et al . (2019). Marine DNA viral macro- and microdiversity from pole to pole. Cell177, 1109–1123.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.040

82

Hagedorn M. Varga Z. Walter R. B. Tiersch T. R. (2019). Workshop report: Cryopreservation of aquatic biomedical models. Cryobiology86, 120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2018.10.264

83

Hahn M. A. Piecyk A. Jorge F. Cerrato R. Kalbe M. Dheilly N. M. (2022). Host phenotype and microbiome vary with infection status, parasite genotype, and parasite microbiome composition. Mol. Ecol.31, 1577–1594. doi: 10.1111/mec.16344

84

Hanning I. Diaz-Sanchez S. (2015). The functionality of the gastrointestinal microbiome in non-human animals. Microbiome3, 51. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0113-6

85

Happywhale (2024). About happywhale. Available online at: https://happywhale.com/about (Accessed February 1 2024).

86

Hauffe H. C. Barelli C. (2019). Conserve the germs: the gut microbiota and adaptive potential. Conserv. Genet. 20, 19–27. doi: 10.1007/s10592-019-01150-y

87

Hardisty A. R. Ellwood E. R. Nelson G. Zimkus B. Buschbom J. Addink W. et al . (2022). Digital extended specimens: enabling an extensible network of biodiversity data records as integrated digital objects on the internet. BioScience72, 978–987. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biac060

88

Heylen K. Hoefman S. Vekeman B. Peiren J. De Vos P. (2012). Safeguarding bacterial resources promotes biotechnological innovation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.94, 565–574. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3797-y

89

Hoag H. (2009). The cold rush. Nat. Biotechnol.27, 690–692. doi: 10.1038/nbt0809-690

90

Hornborg S. Törnqvist O. Novaglio C. Selgrath J. Kågesten G. Loo L.-O. et al . (2021). On potential use of historical perspectives in Swedish marine management. Available online at: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:ri:diva-52981 (Accessed May 13, 2024).

91

Howe D. Costanzo M. Fey P. Gojobori T. Hannick L. Hide W. et al . (2008). The future of biocuration. Nature455, 47–50. doi: 10.1038/455047a

92

Hupman K. Visser I. Martinez E. Stockin K. (2014). Using platforms of opportunity to determine the occurrence and group characteristics of orca (Orcinus orca) in the Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand. New Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res.49, 132–149. doi: 10.1080/00288330.2014.980278

93

Ibáñez A. Garrido-Chamorro S. Barreiro C. (2023). Microorganisms and climate change: A not so invisible effect. Microbiol. Res.14 (3), 918–947. doi: 10.3390/microbiolres14030064

94

Isojunno S. Matthiopoulos J. Evans P. G. H. (2012). Harbour porpoise habitat preferences: robust spatio-temporal inferences from opportunistic data. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.448, 155–170. doi: 10.3354/meps09415

95

Jensen E. L. Díez-del-Molino D. Gilbert M. T. P. Bertola L. D. Borges F. Cubric-Curik V. et al . (2022). Ancient and historical DNA in conservation policy. Trends Ecol. Evol.37, 420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2021.12.010

96

Johnston A. Matechou E. Dennis E. B. (2023). Outstanding challenges and future directions for biodiversity monitoring using citizen science data. Methods Ecol. Evol.14, 103–116. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.13834

97

Joint Cetacean Data Programme Information Hub . Available online at: https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/joint-cetacean-data-programme/ (Accessed June 3, 2024).

98

Junge K. Eicken H. Swanson B. D. Deming J. W. (2006). Bacterial incorporation of leucine into protein down to –20°C with evidence for potential activity in sub-eutectic saline ice formations. Cryobiology52, 417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2006.03.002

99

Karsenti E. Acinas S. G. Bork P. Bowler C. Vargas C. D. Raes J. et al . (2011). A holistic approach to marine eco-systems biology. PloS Biol.9, e1001177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001177

100

Kerckhof F.-M. Courtens E. N.P. Geirnaert A. Hoefman S. Ho A. Vilchez-Vargas R. et al . (2014). Optimized Cryopreservation of Mixed Microbial Communities for Conserved Functionality and Diversity. PLoS One9, e99517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099517

101

Killer Whale Count - Zooniverse . Available online at: https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/alexa-dot-hasselman/killer-whale-count (Accessed May 19, 2024).

102

Klotz L. Fernandez R. Rasmussen M. H. (2017). Annual and monthly fluctuations in humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) presence in Skjálfandi Bay, Iceland, during the feeding season (April–October). J. Cetacean Res. Manage.16, 9–16. doi: 10.47536/jcrm.v16i1

103

Knight R. Vrbanac A. Taylor B. C. Aksenov A. Callewaert C. Debelius J. et al . (2018). Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.16, 410–422. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0029-9

104

Laiolo E. Alam I. Uludag M. Jamil T. Agusti S. Gojobori T. et al . (2024). Metagenomic probing toward an atlas of the taxonomic and metabolic foundations of the global ocean genome. Front. Sci.1. doi: 10.3389/fsci.2023.1038696

105

Laird S. Wynberg R. (2018). Fact-finding and scoping study on digital sequence information on genetic resources in the context of the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Nagoya Protocol. In Montreal: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Ad Hoc Technical Expert Group on Digital Sequence Information on Genetic Resources (pp. 2-79). Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/b39f/4faf/7668900e8539215e7c7710fe/dsi-ahteg-2018-01-03-en.pdf (Accessed February 6, 2025).

106

Lee K. M. Adams M. Klassen J. L. (2019). Evaluation of DESS as a storage medium for microbial community analysis. PeerJ7, e6414. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6414

107

Leigh D. M. van Rees C. B. Millette K. L. Breed M. F. Schmidt C. Bertola L. D. et al . (2021). Opportunities and challenges of macrogenetic studies. Nat. Rev. Genet.22, 791–807. doi: 10.1038/s41576-021-00394-0

108

Lendemer J. Thiers B. Monfils A. K. Zaspel J. Ellwood E. R. Bentley A. et al . (2020). The extended specimen network: A strategy to enhance US biodiversity collections, promote research and education. BioScience70, 23–30. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biz140

109

Lobanov V. Gobet A. Joyce A. (2022). Ecosystem-specific microbiota and microbiome databases in the era of big data. Environ. Microbiome17, 37. doi: 10.1186/s40793-022-00433-1

110

Lofgren L. A. Stajich J. E. (2021). Fungal biodiversity and conservation mycology in light of new technology, big data, and changing attitudes. Curr. Biol.31, R1312–R1325. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.06.083

111

Lotze H. K. Worm B. (2009). Historical baselines for large marine animals. Trends Ecol. Evol.24, 254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.12.004

112

Lydersen C. Assmy P. Falk-Petersen S. Kohler J. Kovacs K. M. Reigstad M. et al . (2014). The importance of tidewater glaciers for marine mammals and seabirds in Svalbard, Norway. J. Mar. Syst.129, 452–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2013.09.006

113

Lynch J. B. Hsiao E. Y. (2019). Microbiomes as sources of emergent host phenotypes. Science365, 1405–1409. doi: 10.1126/science.aay0240

114

Mallory M. L. Gilchrist H. G. Janssen M. Major H. L. Merkel F. Provencher J. F. et al . (2018). Financial costs of conducting science in the Arctic: examples from seabird research. Arctic Sci.4, 624–633. doi: 10.1139/as-2017-0019

115

Mann J. (1999). Behavioral sampling methods for cetaceans: A review and critique. Mar. Mammals Sci.15, 102–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00784.x

116

Manter D. K. Delgado J. A. Blackburn H. D. Harmel D. Pérez de León A. A. Honeycutt C. W. (2017). Why we need a National Living Soil Repository. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.114, 13587–13590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720262115

117

Martínez-Páramo S. Horváth Á. Labbé C. Zhang T. Robles V. Herráez P. et al . (2017). Cryobanking of aquatic species. Aquaculture472, 156–177. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.05.042

118

Martiny J. B. H. Whiteson K. L. Bohannan B. J. M. David L. A. Hynson N. A. McFall-Ngai M. et al . (2020). The emergence of microbiome centres. Nat. Microbiol.5, 2–3. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0644-x

119

McBride-Kebert S. Taylor J. S. Lyn H. Moore F. R. Sacco D. Kar B. et al . (2019). Controlling for survey effort is worth the effort: comparing bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) habitat use between standardized and opportunistic photographic-identification surveys. Aquat. Mammals45, 21–29. doi: 10.1578/AM.45.1.2019.21

120

McCluskey K. (2017). A review of living collections with special emphasis on sustainability and its impact on research across multiple disciplines. Biopreservation Biobanking15, 20–30. doi: 10.1089/bio.2016.0066

121

Mecklenburg C. W. Møller P. R. Steinke D. (2011). Biodiversity of arctic marine fishes: taxonomy and zoogeography. Mar. Biodiv41, 109–140. doi: 10.1007/s12526-010-0070-z

122

Meineke E. K. Davies T. J. Daru B. H. Davis C. C. (2018). Biological collections for understanding biodiversity in the Anthropocene. Phil Transact Royal Soc B: Biolog Sci.374, 20170386. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2017.0386

123

Menke S. Gillingham M. A. F. Wilhelm K. Sommer S. (2017). Home-made cost effective preservation buffer is a better alternative to commercial preservation methods for microbiome research. Front. Microbiol.8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00102

124

Meyer R. Appeltans W. Duncan W. Dimitrova M. Gan Y.-M. Jeppesen T. S. et al . (2023). Aligning standards communities for omics biodiversity data: sustainable darwin core-MIxS interoperability. Biodiversity Data J.11, e112420. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.11.e112420

125

Microbe (2023). Available online at: https://www.microbeproject.eu/ (Accessed June 19, 2024).

126

Mooney A. Ryder O. A. Houck M. L. Staerk J. Conde D. A. Buckley Y.M (2023). Maximizing the potential for living cell banks to contribute to global conservation priorities. Zoo Biol.42, 697–708. doi: 10.1002/zoo.21787

127

Morganti T. M. Slaby B. M. de Kluijver A. Busch K. Hentschel U. Middelburg J. J. et al . (2022). Giant sponge grounds of Central Arctic seamounts are associated with extinct seep life. Nat. Commun.13, 638. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28129-7

128

Moss A. Vukelic M. Walker S. L. Smith C. Spooner S. L. (2023). The role of zoos and aquariums in contributing to the kunming–montreal global biodiversity framework. J. Zoological Botanical Gardens4, 445–461. doi: 10.3390/jzbg4020033

129

Nakanishi K. Deuchi K. Kuwano K. (2012). Cryopreservation of four valuable strains of microalgae, including viability and characteristics during 15 years of cryostorage. J. Appl. Phycol24, 1381–1385. doi: 10.1007/s10811-012-9790-8

130

NAMMCO (2019). Sightings Surveys in the North Atlantic: 30 years of counting whales. NAMMCO Sci. Publications11. doi: 10.7557/3.11

131

Nissimov J. I. Campbell C. N. Probert I. Wilson W. H. (2022). Aquatic virus culture collection: an absent (but necessary) safety net for environmental microbiologists. Appl. Phycology3, 211–225. doi: 10.1080/26388081.2020.1770123

132

O’Brien K. M. Crockett E. L. Adams B. J. Amsler C. D. Appiah-Madson H. J. Collins A. et al . (2022). The time is right for an Antarctic biorepository network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.119, e2212800119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2212800119

133

Ojaveer H. Galil B. S. Carlton J. T. Alleway H. Goulletquer P. Lehtiniemi M. et al . (2018). Historical baselines in marine bioinvasions: Implications for policy and management. PloS One13, e0202383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202383

134

Oliveira-Rodrigues C. Correia A. M. Valente R. Gil A. Gandra M. Rosso M. et al . (2022). Assessing data bias in visual surveys from a cetacean monitoring programme. Sci. Data9, 682. doi: 10.1038/s41597-022-01803-7

135

Osman E. O. Weinnig A. M. (2022). Microbiomes and obligate symbiosis of deep-sea animals. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci.10, 151–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-081621-112021

136

Peixoto R. S. Voolstra C. R. Sweet M. Duarte C. M. Carvalho S. Villela H. et al . (2022). Harnessing the microbiome to prevent global biodiversity loss. Nat. Microbiol.7, 1726–1735. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01173-1

137

Post S. Werner K. M. Núñez-Riboni I. Chafik L. Hátún H. Jansen T. (2021). Subpolar gyre and temperature drive boreal fish abundance in Greenland waters. Fish Fisheries22, 161–174. doi: 10.1111/faf.12512

138

Poo S. Whitfield S. M. Shepack A. Watkins-Colwell G. J. Nelson G. Goodwin J. (2022). Bridging the research gap between live collections in zoos and preserved collections in Natural History Museums. BioScience72, 449–460. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biac022

139

Prakash O. Nimonkar Y. Desai D. (2020). A recent overview of microbes and microbiome preservation. Indian J. Microbiol.60, 297–309. doi: 10.1007/s12088-020-00880-9

140

Prakash O. Nimonkar Y. Shouche Y. S. (2013). Practice and prospects of microbial preservation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett.339, 1–9. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12034

141

Pyle P. (2007). Standardizing At-sea Monitoring Programs for Marine Birds, Mammals, Other Organisms, Debris, and Vessels, including Recommendations for West-Coast National Marine Sanctuaries. Available online at: https://sanctuarysimon.org/regional_docs/monitoring_projects/84_doc3.pdf (Accessed January 28, 2024).

142

Qi X. Li Z. Zhao C. Zhang Q. Zhou Y. (2024). Environmental impacts of Arctic shipping activities: A review. Ocean Coast. Manage.247, 106936. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2023.106936

143

Rain-Franco A. de Moraes G. P. Beier S. (2021). Cryopreservation and resuscitation of natural aquatic prokaryotic communities. Front. Microbiol.11. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.597653

144

Rantanen M. Karpechko A. Y. Lipponen A. Nordling K. Hyvärinen O. Ruosteenoja K. et al . (2022). The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ.3, 1–10. doi: 10.1038/s43247-022-00498-3

145

Robbins J. Frost M. (2009). An on-line database for world-wide tracking of commercial whale watching and associated data collection programs. Paper SC/61/WW7 presented to the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission. Retrieved June 4, 2011. Available online at: https://iwc.int/document_1788 (Accessed January 28, 2024).

146

Rölfer L. Liconti A. Prinz N. Klöcker C. A. (2021). Integrated research for integrated ocean management. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.693373

147

Rosendal G. K. Myhr A. I. Tvedt M. W. (2016). Access and benefit sharing legislation for marine bioprospecting: lessons from Australia for the role of marbank in Norway. J. World Intellectual Property19, 86–98. doi: 10.1111/jwip.12058

148

Rotter A. Barbier M. Bertoni F. Bones A. M. Cancela M. L. Carlsson J. et al . (2021). The essentials of marine biotechnology. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.629629

149

Rusch D. B. Halpern A. L. Sutton G. Heidelberg K. B. Williamson S. Yooseph S. et al . (2007). The sorcerer II global ocean sampling expedition: northwest atlantic through eastern tropical pacific. PloS Biol.5, e77. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050077

150

Ryan M. J. Mauchline T. H. Malone J. G. Jones S. Thompson C. M. A. Bonnin J. M. et al . (2023). The UK Crop Microbiome Cryobank: A utility and model for supporting Phytobiomes research. CABI Agric. Bioscience4, 53. doi: 10.1186/s43170-023-00190-2

151

Ryan M. J. Schloter M. Berg G. Kinkel L. L. Eversole K. Macklin J. A. et al . (2021a). Towards a unified data infrastructure to support European and global microbiome research: a call to action. Environ. Microbiol.23, 372–375. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15323

152

Ryan M. J. Schloter M. Berg G. Kostic T. Kinkel L. L. Eversole K. et al . (2021b). Development of microbiome biobanks – challenges and opportunities. Trends Microbiol.29, 89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2020.06.009

153

Samuel R. M. Meyer R. Buttigieg P. L. Davies N. Jeffery N. W. Meyer C. et al . (2021). Toward a global public repository of community protocols to encourage best practices in biomolecular ocean observing and research. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.758694

154

Sanders J. G. Beichman A. C. Roman J. Scott J. J. Emerson D. McCarthy J. J. et al . (2015). Baleen whales host a unique gut microbiome with similarities to both carnivores and herbivores. Nat. Commun.6, 8285. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9285

155

Sayigh L. Quick N. Hastie G. Tyack P. (2013). Repeated call types in short-finned pilot whales, Globicephala macrorhynchus. Mar. Mammal Sci.29, 312–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2012.00577.x

156

Schindel D. E. Cook J. A. (2018). The next generation of natural history collections. PloS Biol.16, e2006125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006125

157

Schmidt T. S. B. Fullam A. Ferretti P. Orakov A. Maistrenko O. M. Ruscheweyh H.-J. et al . (2024). SPIRE: A searchable, planetary-scale mIcrobiome REsource. Nucleic Acids Res.52, D777–D783. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad943

158

Schuurman N. Leszczynski A. (2008). Ontologies for bioinformatics. Bioinform. Biol. Insights2, BBI.S451. doi: 10.4137/BBI.S451

159

Sehnal L. Brammer-Robbins E. Wormington A. M. Blaha L. Bisesi J. Larkin I. et al . (2021). Microbiome composition and function in aquatic vertebrates: small organisms making big impacts on aquatic animal health. Front. Microbiol.12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.567408

160

Smaldino P. E. McElreath R. (2016). The natural selection of bad science. R. Soc. Open Sci.3, 160384. doi: 10.1098/rsos.160384

161

Smith D. McCluskey K. Stackebrandt E. (2014). Investment into the future of microbial resources: culture collection funding models and BRC business plans for biological resource centres. SpringerPlus3, 81. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-81

162

Song S. J. Amir A. Metcalf J. L. Amato K. R. Xu Z. Z. Humphrey G. et al . (2016). Preservation methods differ in fecal microbiome stability, affecting suitability for field studies. mSystems1, 10.1128/msystems.00021-16. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00021-16

163

Stark P. B. (2018). Before reproducibility must come preproducibility. Nature557, 613–613. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05256-0

164

Stefanni S. Mirimin L. Stanković D. Chatzievangelou D. Bongiorni L. Marini S. et al . (2022). Framing cutting-edge integrative deep-sea biodiversity monitoring via environmental DNA and optoacoustic augmented infrastructures. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.797140

165

Stephenson P. J. (2021). A Review Of Biodiversity Data Needs And Monitoring Protocols for the Offshore Wind Energy Sector in the Baltic Sea and North Sea (Berlin, Germany: Report for the Renewables Grid Initiative). Available online at: https:/renewables-grid.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/_RGI_Report_PJ-Stephenson_October.pdf (Accessed January 27, 2025).

166

Sterner B. W. Gilbert E. E. Franz N. M. (2020). Decentralized but globally coordinated biodiversity data. Front. Big Data3. doi: 10.3389/fdata.2020.519133

167

Sunagawa S. Acinas S. G. Bork P. Bowler C. Eveillard D. Gorsky G. et al . (2020). Tara Oceans: towards global ocean ecosystems biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.18, 428–445. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-0364-5

168

Suttle C. A. (2007). Marine viruses—Major players in the global ecosystem. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.5801–812. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1750

169

Sweeney K. Birkemeier B. Fritz L. Gelatt T. Burkanov V. Altukhov A. (n.d.). Steller Watch - Zooniverse. Available at: https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/sweenkl/steller-watch/about/results (Accessed September 5, 2024).

170

Tennant R. K. Power A. L. Burton S. K. Sinclair N. Parker D. A. Jones R. T. et al . (2022). In-situ sequencing reveals the effect of storage on lacustrine sediment microbiome demographics and functionality. Environ. Microbiome17, 5. doi: 10.1186/s40793-022-00400-w

171

Tessnow-von Wysocki I. Vadrot A. B. M. (2020). The voice of science on marine biodiversity negotiations: A systematic literature review. Front. Mar. Sci.7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.614282

172

Thompson L. R. Sanders J. G. McDonald D. Amir A. Ladau J. Locey K. J. et al . (2017). A communal catalogue reveals Earth’s multiscale microbial diversity. Nature551, 457–463. doi: 10.1038/nature24621

173

Thornton T. F. Scheer A. M. (2012). Collaborative engagement of local and traditional knowledge and science in marine environments: A review. Ecol. Soc.17 (3). Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26269064.

174

Thukral M. Allen A. E. Petras D. (2023). Progress and challenges in exploring aquatic microbial communities using non-targeted metabolomics. ISME J.17, 2147–2159. doi: 10.1038/s41396-023-01532-8

175

Vachon F. Hersh T. A. Rendell L. Gero S. Whitehead H. (2022). Ocean nomads or island specialists? Culturally driven habitat partitioning contrasts in scale between geographically isolated sperm whale populations. R. Soc. Open Sci.9, 211737. doi: 10.1098/rsos.211737

176

Valsecchi E. Arcangeli A. Lombardi R. Boyse E. Carr I. M. Galli P. et al . (2021). Ferries and environmental DNA: underway sampling from commercial vessels provides new opportunities for systematic genetic surveys of marine biodiversity. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.704786

177

Vangay P. Burgin J. Johnston A. Beck K. L. Berrios D. C. Blumberg K. et al . (2021). Microbiome metadata standards: report of the national microbiome data collaborative’s workshop and follow-on activities. mSystems6, 10.1128/msystems.01194-20. doi: 10.1128/msystems.01194-20

178

van Weelden C. Towers J. R. Bosker T. (2021). Impacts of climate change on cetacean distribution, habitat and migration. Climate Change Ecol.1, 100009. doi: 10.1016/j.ecochg.2021.100009

179

Vekeman B. Heylen K. (2015). “Preservation of microbial pure cultures and mixed communities,” in Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology Protocols: Isolation and Cultivation Springer Protocols Handbooks. Eds. McGenityT. J.TimmisK. N.NogalesB. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg), 299–315. doi: 10.1007/8623_2015_51

180

Vinding K. Bester M. Kirkman S. P. Chivell W. Elwen S. H. (2015). The use of data from a platform of opportunity (Whale watching) to study coastal cetaceans on the southwest coast of South Africa. Tourism Mar. Environments11, 33–54. doi: 10.3727/154427315x14398263718439

181

West A. G. Waite D. W. Deines P. Bourne D. G. Digby A. McKenzie V. J. et al . (2019). The microbiome in threatened species conservation. Biol. Conserv.229, 85–98. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.11.016

182

Wietz M. Bienhold C. Metfies K. Torres-Valdés S. von Appen W.-J. Salter I. et al . (2021). The polar night shift: seasonal dynamics and drivers of Arctic Ocean microbiomes revealed by autonomous sampling. Isme Commun.1, 1–12. doi: 10.1038/s43705-021-00074-4

183

WildMe (2024). About flukebook. Available online at: https://www.flukebook.org/overview.jsp (Accessed February 1 2024).

184

Wilkins L. G. E. Leray M. O’Dea A. Yuen B. Peixoto R. S. Pereira T. J. et al . (2019). Host-associated microbiomes drive structure and function of marine ecosystems. PloS Biol.17, e3000533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000533

185