- 1Department of Public Health and Infectious Diseases, Sapienza University, Rome, Italy

- 2Department of Chemical Sciences, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy

- 3Laboratory of Biochemistry, Centre for Protein Engineering, University of Liège, Liège, Belgium

Microbial biofilms have great negative impacts on the world’s economy and pose serious problems to industry, public health and medicine. The interest in the development of new approaches for the prevention and treatment of bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation has increased. Since, bacterial pathogens living in biofilm induce persistent chronic infections due to the resistance to antibiotics and host immune system. A viable approach should target adhesive properties without affecting bacterial vitality in order to avoid the appearance of resistant mutants. Many bacteria secrete anti-biofilm molecules that function in regulating biofilm architecture or mediating the release of cells from it during the dispersal stage of biofilm life cycle. Cold-adapted marine bacteria represent an untapped reservoir of biodiversity able to synthesize a broad range of bioactive compounds, including anti-biofilm molecules. The anti-biofilm activity of cell-free supernatants derived from sessile and planktonic cultures of cold-adapted bacteria belonging to Pseudoalteromonas, Psychrobacter, and Psychromonas species were tested against Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. Reported results demonstrate that we have selected supernatants, from cold-adapted marine bacteria, containing non-biocidal agents able to destabilize biofilm matrix of all tested pathogens without killing cells. A preliminary physico-chemical characterization of supernatants was also performed, and these analyses highlighted the presence of molecules of different nature that act by inhibiting biofilm formation. Some of them are also able to impair the initial attachment of the bacterial cells to the surface, thus likely containing molecules acting as anti-biofilm surfactant molecules. The described ability of cold-adapted bacteria to produce effective anti-biofilm molecules paves the way to further characterization of the most promising molecules and to test their use in combination with conventional antibiotics.

Introduction

The great ability of bacteria to colonize new environments can be linked, in most cases, to their capacity to develop a protective architecture called biofilm. The biofilm lifestyle is associated with a high tolerance to exogenous stress, and treatment of biofilms with antibiotics or other biocides is usually ineffective at eradicating them (Hall-Stoodley and Stoodley, 2009). Biofilm formation is therefore a major problem in many fields, ranging from the food industry to medicine (López et al., 2010; Høiby et al., 2011). It is worth mentioning that, in medical settings, biofilms are the cause of persistent infections implicated in 80% or more of all microbial cases-releasing harmful toxins and even obstructing indwelling catheters (Epstein et al., 2012).

Staphylococci are recognized as the most frequent causes of biofilm-associated infections (Otto, 2008). Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is an opportunistic dangerous pathogen that can cause serious diseases in humans, ranging from skin and soft tissue infections to invasive infections of the bloodstream, heart, lungs and other organs. A statistical study showed that 30% of U.S. population was colonized by S. aureus (Nicholson et al., 2013). In addition, 1.5% of U.S. population was found to be a carrier of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) that is a major cause of healthcare-related infections, responsible for significant proportion of nosocomial infections worldwide. Recently in the U.S., deaths from MRSA infections have surpassed those from many other infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS (Nicholson et al., 2013).

Staphylococcus epidermidis, conventionally considered as a commensal bacterium of human skin, it can cause significant problems when breaching the epithelial barrier, especially during biofilm-associated infection of indwelling medical devices (Dohar et al., 2009; Rogers et al., 2009). Most diseases caused by S. epidermidis are of a chronic character and occur as device-related infections (such as intravascular catheter or prosthetic joint infections) and/or their complications (Rogers et al., 2009).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) is an important pathogen responsible for infections in patients who suffer from respiratory diseases (Saxena et al., 2014) like cystic fibrosis (CF). Recurrent and chronic respiratory tract infections in CF patients result in progressive lung damage and represent the primary cause of morbidity and mortality. P. aeruginosa can cause hard to treat life threatening infections due to its high resistance to antibiotics and to the ability to form antibiotic tolerant biofilms.

The development of anti-biofilm strategies is therefore of major interest and currently constitutes an important field of investigation in which non–biocidal molecules are highly valuable to avoid the rapid appearance of escape mutants.

From another point of view, the biofilm could be considered as a source of novel drugs and holds great potential due to the specific physical and chemical conditions of its ecosystem. For example, the production of extracellular molecules that degrade adhesive components in the biofilm matrix is a basic mechanism used in the biological competition between phylogenetically different bacteria (Brook, 1999; Wang et al., 2007, 2010). These compounds often exhibit broad-spectrum biofilm-inhibiting or biofilm-detaching activity when tested in vitro and their use in a combination therapy with antibiotics could be of interest.

Marine bacteria are a resource of biologically active products (Debbab et al., 2010). Cold-adapted marine bacteria represent an untapped reservoir of biodiversity endowed with an interesting chemical repertoire. A preliminary characterization of molecules isolated from cold-adapted bacteria revealed that these compounds display antimicrobial, anti-fouling and various pharmaceutically relevant activities (Bowman, 2007). The ability of Polar marine bacteria, belonging to different genera/species, to synthesize bioactive molecules might represent the results of the selective pressure to which these bacteria are subjected. One of the developed survival strategies may be represented by the production of metabolites with anti-biofilm activity, which might be exploited to fight the biological competition of other bacteria.

Recently, we observed that Antarctic marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis TAC125 produces and secretes several compounds of biotechnological interest (Papaleo et al., 2013), including molecules inhibiting the biofilm of the human pathogen S. epidermidis (Papa et al., 2013b; Parrilli et al., 2015). This activity impairs biofilm development and disaggregates the mature biofilm without affecting bacterial viability, showing that its action is specifically directed against biofilm (Papa et al., 2013b; Parrilli et al., 2015).

In this work we evaluated the anti-biofilm activity of supernatants derived from cultures of cold-adapted bacteria belonging to Pseudoalteromonas, Psychrobacter, and Psychromonas genera. Supernatants were obtained from bacterial cultures made both in sessile and planktonic conditions. The potential anti-biofilm activity was tested on bacterial cultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1, three different strains of S. aureus and three different strains belonging S. epidermidis species. The results obtained highlighted that several supernatants show anti-biofilm activity against most species analyzed. Preliminary evaluations on the physico-chemical nature of the molecules responsible for anti-biofilm activity emphasized their different nature.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

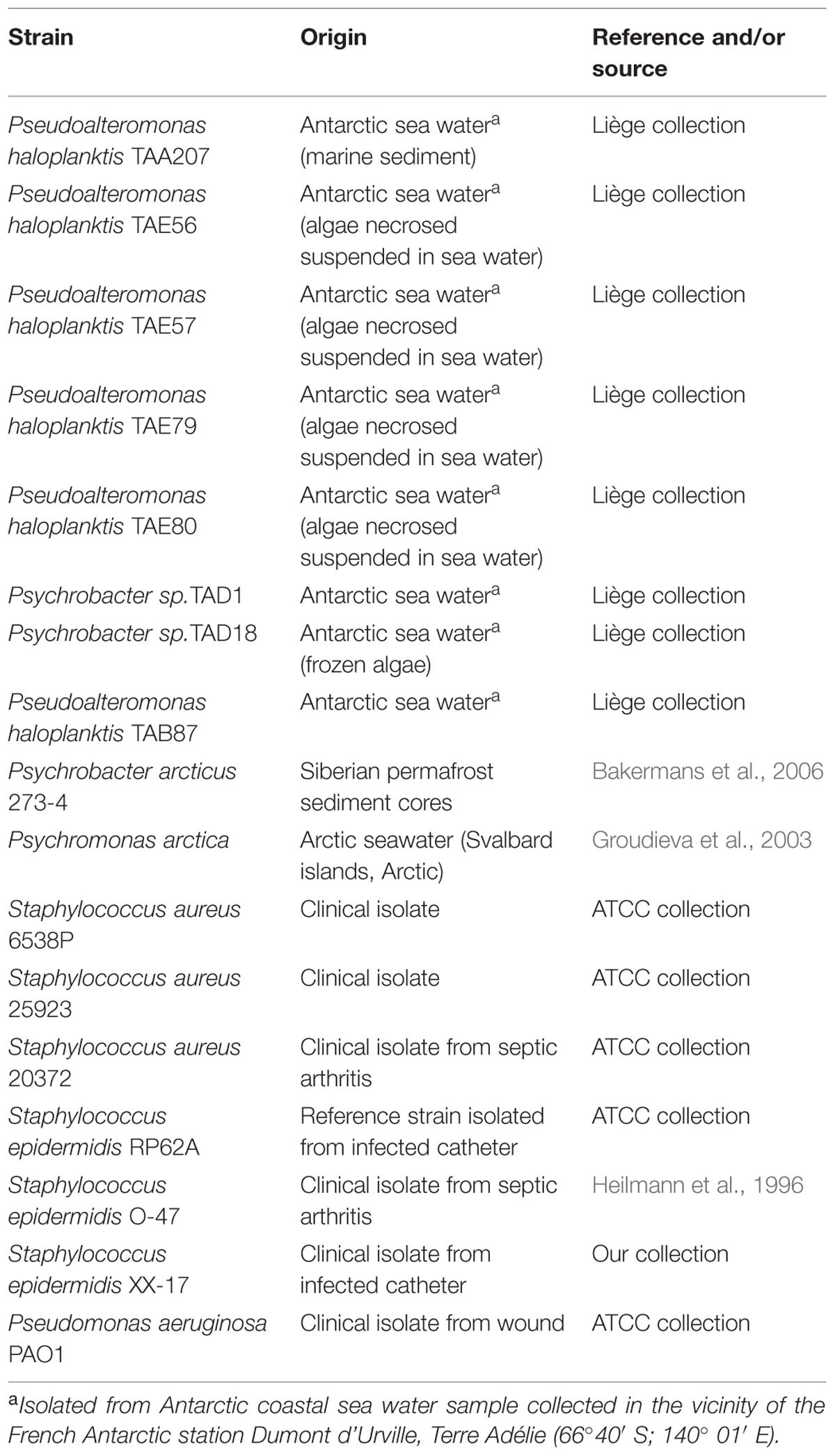

Bacterial strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were grown in Brain Heart Infusion broth (BHI, Oxoid, UK). Biofilm formation was assessed in static conditions. Planktonic cultures were grown in flasks under vigorous agitation (180 rpm). Cold-adapted bacteria were grown at 15°C, while staphylococci and P. aeruginosa were grown at 37°C.

Biofilm Formation of Polar Bacteria

Biofilm formation of cold-adapted bacteria was obtained at 15°C in BHI (Oxoid, UK). The wells of a sterile 24-well flat-bottomed polystyrene plate were filled with 1 ml of BHI, and an opportune dilution of bacterial culture in exponential growth phase (about 0.1 OD 600 nm) was added into each well. The plates were aerobically incubated up to 96 h at 15°C in static condition, measuring biofilm formation each 24 h. After the removal of spent medium and of not adhered cells and rinsing with PBS, adhered cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet, rinsed twice with double-distilled water, and thoroughly dried as previously described (Papa et al., 2013a). The dye bound to adherent cells was solubilized with 20% (v/v) glacial acetic acid and 80% (v/v) ethanol. The absorbance of each well was measured at 590 nm. Each data point is composed of four independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Preparation of Cell-free Supernatants from Cold-adapted Bacteria

The cell-free supernatants of a liquid culture of cold-adapted strains grown in sessile condition were designated as SNB, while the cell-free supernatants of a liquid culture of psychrophilic strains grown in planktonic condition were designated as SNP.

For the preparation of SNB, wells of a sterile 24-well flat-bottomed polystyrene plate were filled with 900 μl of BHI and 100 μl of each overnight bacterial culture was added into each well. The plates were incubated at 15°C monitoring biofilm formation each 24 h. After 96 h, supernatants were recovered and centrifuged at 13000 rpm at 4°C for 30 min. Supernatants were sterilized by filtration through membranes with a pore diameter of 0.22 μm, and stored at 4°C until use.

For the preparation of SNP bacterial cultures were grown in planktonic conditions at 15°C under vigorous agitation (180 rpm) for 24 h. Supernatants were recovered by centrifugation at 13000 rpm at 4°C and processed as described above.

Biofilm Formation of Staphylococci and Pseudomonas

Biofilm formation of Staphylococcus and Pseudomonas species was evaluated in the presence of SNB and SNP supernatants, respectively. Quantification of in vitro biofilm production was based on method previously reported (Artini et al., 2015). Briefly, the wells of a sterile 96-well flat-bottomed polystyrene plate were filled with 100 μl of the appropriate medium. 1/100 dilution of overnight bacterial cultures was added into each well (about 5.0 OD 600 nm). Each well was filled with 50 μl of BHI and 50 μl of each supernatant, respectively. In this way each supernatant was used diluted 1:2 with a final concentration of 50%. As control, the first row contained bacteria grown only in 100 μl of BHI (untreated bacteria). The plates were incubated aerobically for 24 h at 37°C.

Biofilm formation was measured using crystal violet staining. After treatment, planktonic cells were gently removed; each well was washed three times with PBS and patted dry with a piece of paper towel in an inverted position. To quantify biofilm formation, each well was stained with 0.1% crystal violet and incubated for 15 min at room temperature, rinsed twice with double-distilled water, and thoroughly dried. The dye bound to adherent cells was solubilized with 20% (v/v) glacial acetic acid and 80% (v/v) ethanol. After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, OD590 was measured to quantify the total biomass of biofilm formed in each well. Each data point is composed of three independent experiments each performed at least in eight-replicates.

Surface Coating Assay

A volume of 25 μl of cell-free supernatant (SNB or SNP), or 25 μl of saline as control, was deposited to the center of a well of a 24-well tissue-culture-treated polystyrene microtiter plate. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 1 h to allow complete evaporation of the liquid. The wells were then filled with 1 ml of broth containing 104–105 CFU/ml of S. epidermidis O-47 and incubated at 37°C. After 18 h, wells were rinsed with water and stained with 1 ml of 0.1% crystal violet. Stained biofilms were rinsed with water and dried, and the wells were photographed.

Physico-chemical Characterization of Anti-biofilm Compounds

The heat sensitivity of anti-biofilm compounds were evaluated by incubating the culture supernatants (SNB or SNP), for 1 h in a water bath at 50°C and cooled on ice. For the protease treatment, proteinase K (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was added to aliquots of supernatants at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml and the reactions were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. As controls, supernatants were incubated for 1 h at 37°C without proteinase K, a treatment which did not impair the anti-biofilm activities. For each of the above tests, the anti-biofilm activities of treated and untreated culture supernatants were compared using the microtiter plate assay against staphylococci and P. aeruginosa PAO1, respectively. Each data point is composed of three independent experiments performed in six-replicates.

Statistics and Reproducibility of Results

Data reported were statistically validated using Student’s t-test comparing mean absorbance of treated and untreated samples. The significance of differences between mean absorbance values was calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Cold-adapted Bacteria Biofilm Formation

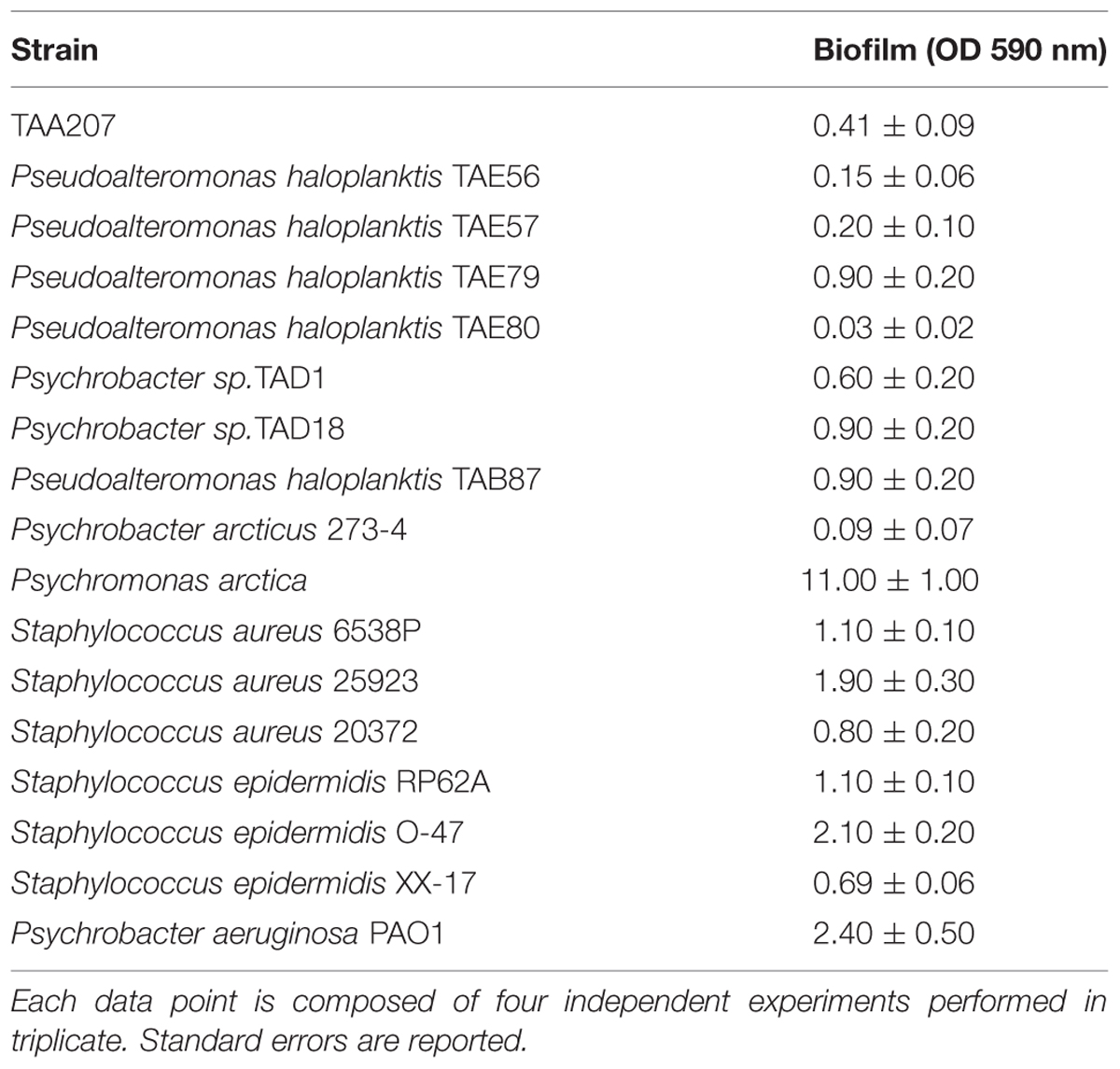

Biofilm formation of Polar bacteria was evaluated at 15°C in BHI at different times as described in material and methods section. Bacteria were grown in static condition in the same medium used for staphylococci and P. aeruginosa cultures to avoid interference in the following experiments due to the medium composition. The biofilm-forming ability of Polar bacterial strains was tested by a quantitative assay. The best production of biofilm was obtained by incubating the cells in static condition for 96 h at 15°C (data not shown). Almost all studied bacteria are able to form biofilm with different capabilities (Table 2). For example, in the tested condition, Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis TAE80 and Psychrobacter arcticus 273-4 seemed to be unable to produce biofilm, while Psychromonas arctica was found to be a strong biofilm producer, as already reported (Vishnivetskaya et al., 2000; Groudieva et al., 2003).

Effect of Exoproducts Derived from Cold-adapted Cultures on Biofilm Formation of Different Pathogen

The anti-biofilm effects of cold-adapted bacterial culture supernatants grown at 15°C either in planktonic or sessile conditions were examined on different pathogens: P. aeruginosa PAO1, three strains belonging to S. epidermidis species, and three strains belonging to S. aureus species (Table 1).

The specific environmental conditions prevailing within biofilms induce profound genetic and metabolic rewiring of the biofilm-dwelling bacteria and can allow the production of metabolites different from those obtained in planktonic condition. Therefore, supernatants deriving from sessile growths were designated as B letter, while supernatants deriving from planktonic cultures under vigorous agitation were designated as P letter, respectively.

In order to exclude that the tested Polar supernatants contain molecules affecting bacterial viability, the 20 cell-free supernatants were analyzed also for antimicrobial activity. An opportune dilution (106cfu/ml were used as reported by National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards NCCLS, 2004) of each bacterial culture of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa in exponential phase was seeded on TSA plates. Each plate was spotted with Polar cell free supernatant separately and incubated at 37°C for 20 h. No antimicrobial activity on S. aureus and P. aeruginosa strains was highlighted for all tested supernatants (data not shown).

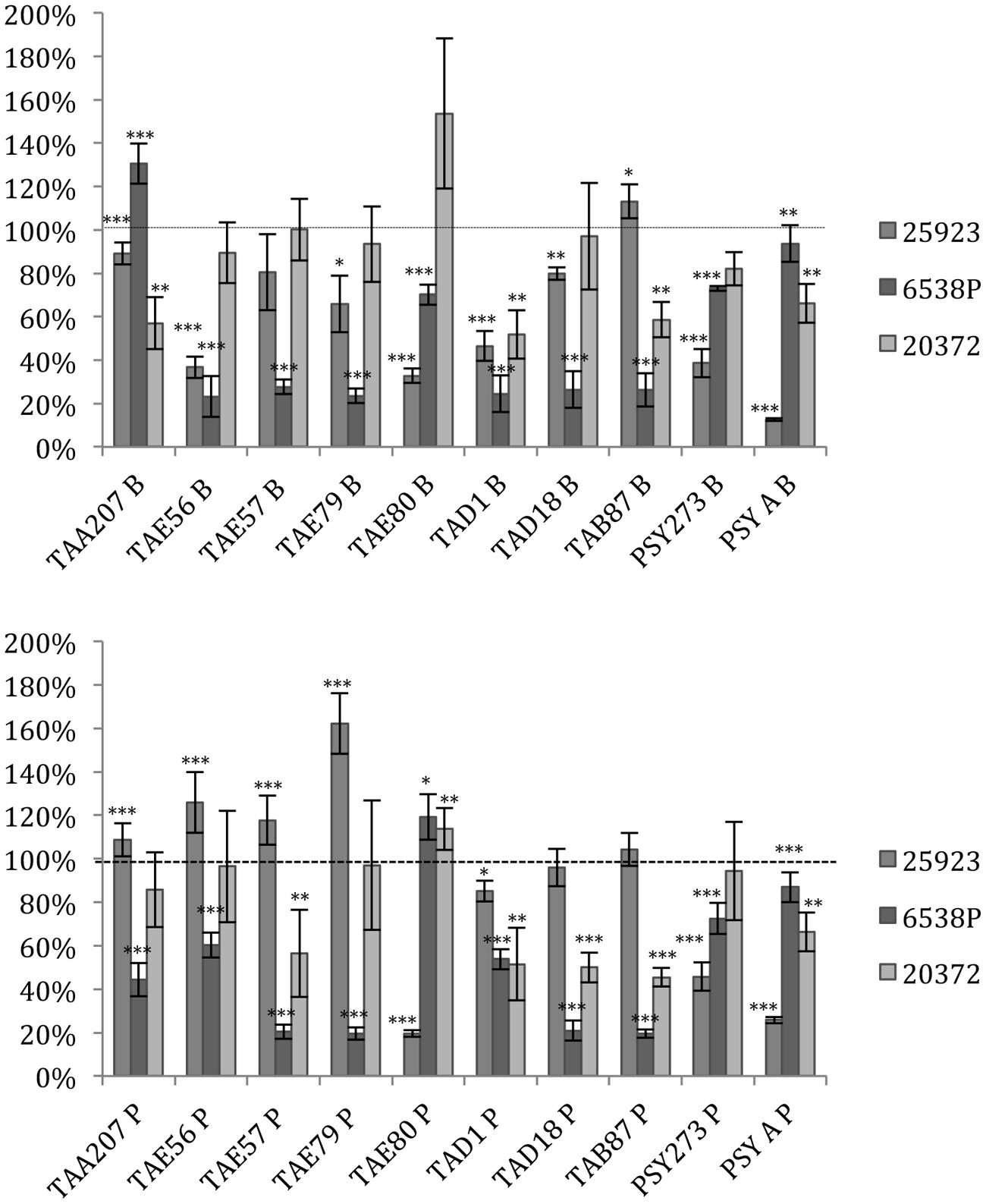

Anti-biofilm effect is reported as percentage of residual biofilm after treatment in comparison with untreated bacteria. In some cases an increase of biofilm formation was highlighted after the treatment.

Several supernatants of Polar bacteria have anti-biofilm activity against all S. aureus tested strains (Figure 1, Supplementary Table S1). S. aureus 6538P showed a reduction in biofilm formation when treated with cold-adapted bacteria supernatants except in the case of TAA207 B and TAE80 P supernatants. TAE80 and PSYA supernatants deriving from both sessile and planktonic growth conditions showed a good anti-biofilm effect on S. aureus 25923, a reference strain for CF infections (Alhanout et al., 2011) (Figure 1). Three supernatants (TAD1 B, TAD18 P, TAB87 P) allowed a reduction of S. aureus 20372 biofilm higher than 50% (Figure 1). As shown in Figure 1, supernatants derived from sessile and planktonic cultures showed differences in their ability to prevent S. aureus biofilm formation and the effect of each supernatant is strictly strain-specific. Indeed, in such cases, the same supernatant is able to impair biofilm formation of one strain rather than others belonging to the same bacterial species; for example, TAD18 P is able to inhibit the biofilm formation of S. aureus 6538P and S. aureus 20372 but it is of not effective on S. aureus 25923. It is interesting to note that supernatants derived from sessile and planktonic cultures of the same Polar bacterium showed differences in their ability to prevent S. aureus biofilm formation, for example TAE80 B supernatant is able to impair biofilm of S. aureus 6538P while TAE80 P induces a significant increase in the biofilm formation. In addition TAE79 B, but not TAE79 P, produces an anti-biofilm molecule able to inhibit the biofilm formation of S. aureus 25923. On the contrary TAE79 P treatment increases the biofilm production of 25923 strain. It is worth mentioning that one supernatant, i.e., TAD1 B, is quite effective in interfering with biofilm formation of all tested S. aureus strains.

FIGURE 1. Effect of Polar supernatant treatment on biofilm formation for three strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Data are reported as percentage of residual biofilm after the treatment. Biofilm formation was considered unaffected in the range 90–100%. Differences in mean absorbance were compared to the untreated control and considered statistically significant when p < 0.05 (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) according to Student’s t-test.

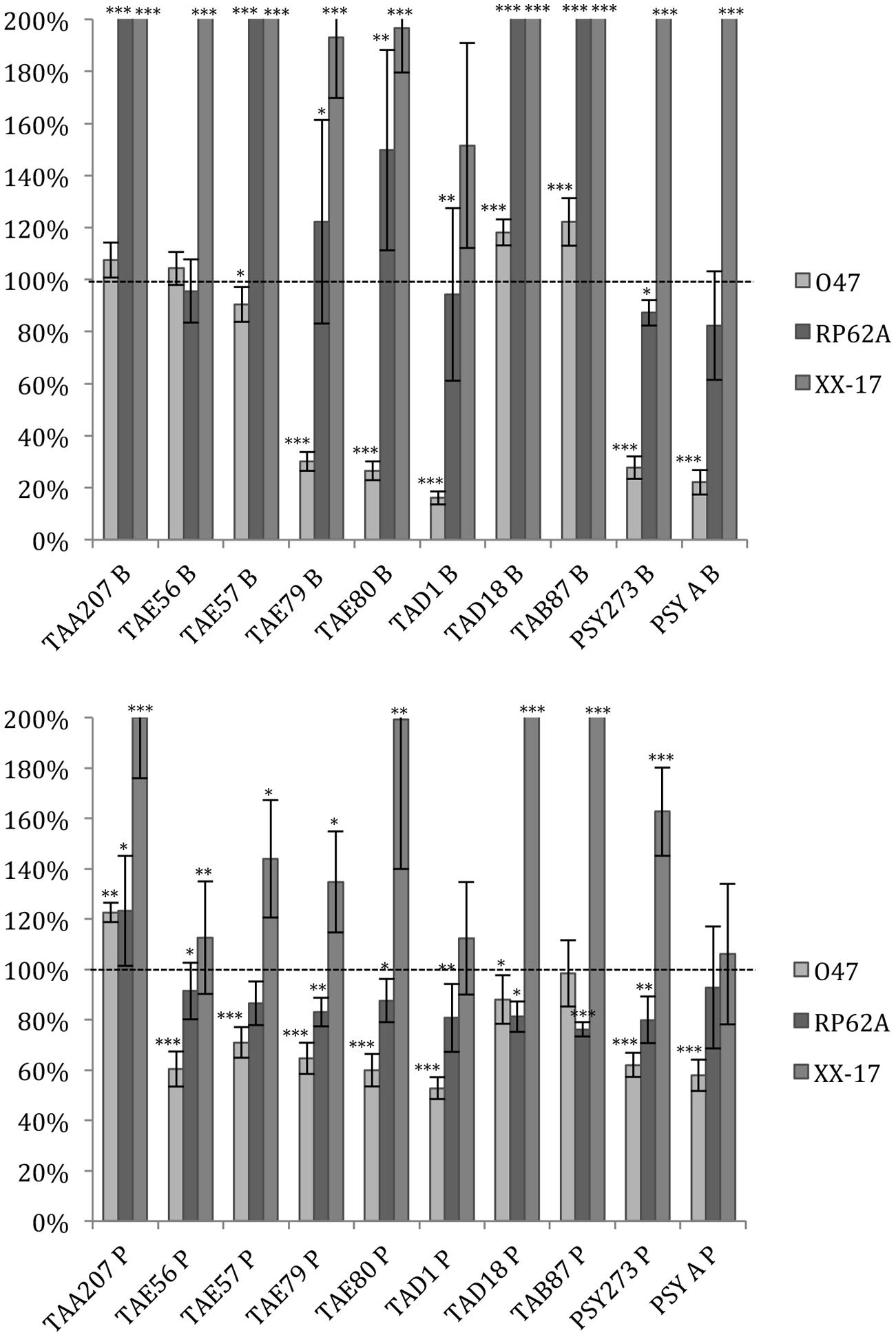

As far as S. epidermidis is concerned (Figure 2), in most cases the treatments induced an increase in biofilm formation, except for S. epidermidis O-47 strain treated with TAE79, TAE80, TAD1, PSY273 and PSYA supernatants derived from planktonic and sessile cultures where a strong reduction was evidenced (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Effect of Polar supernatant treatment on biofilm formation for three strains of S. epidermidis. Data are reported as percentage of residual biofilm after the treatment. Biofilm formation was considered unaffected in the range 90–100%. Differences in mean absorbance were compared to the untreated control and considered statistically significant when p < 0.05 (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) according to Student’s t-test.

Also in the case of S. epidermidis, supernatants derived from sessile and planktonic cultures of the same Polar bacterium showed differences in their ability to prevent biofilm formation. Cell free supernatant of TAE56P is able to inhibit the biofilm of S. epidermidis O-47 while TAE56B has no effect, indicating that the anti-biofilm molecule is produced only when the cells are grown in planktonic condition.

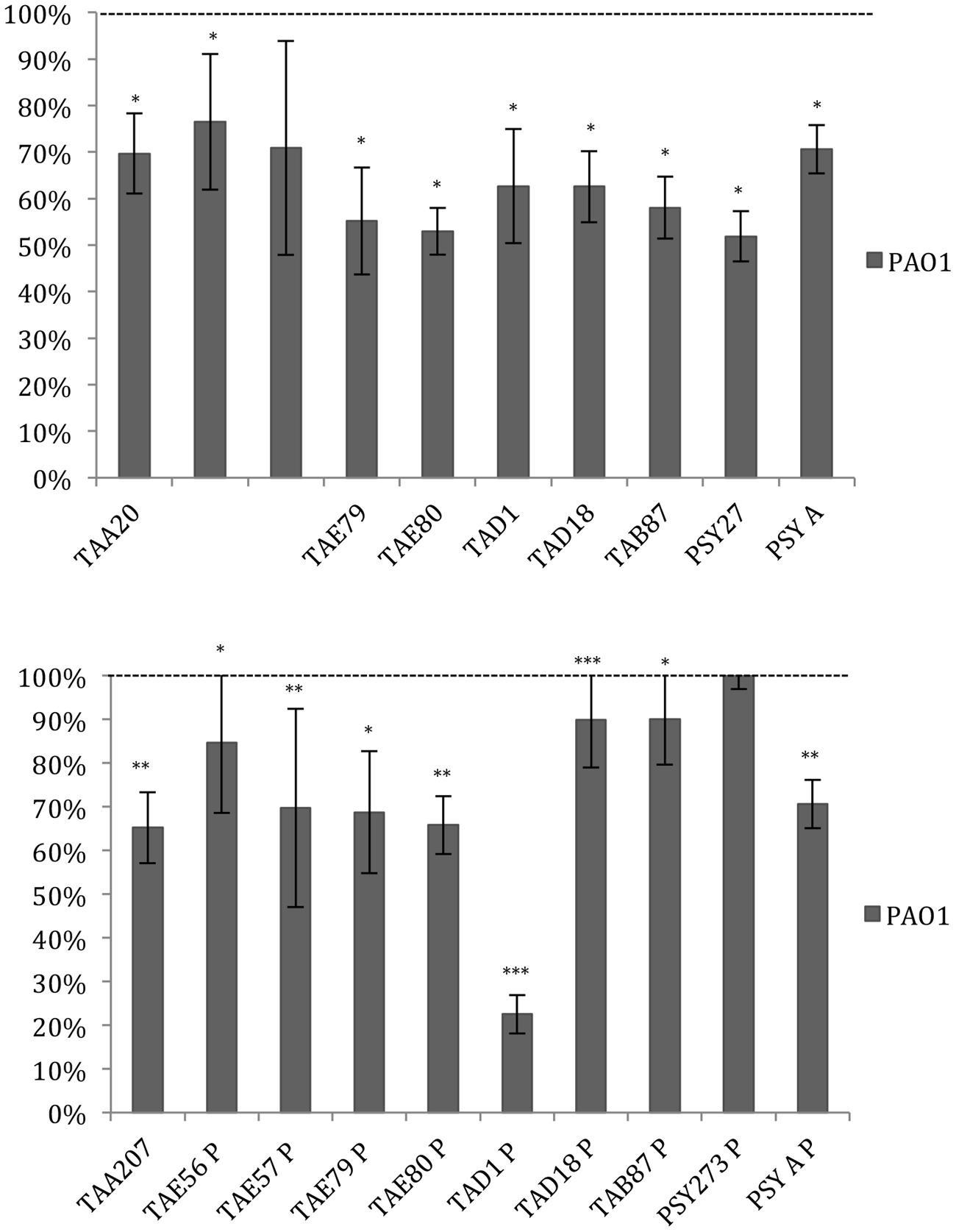

Data reported in Figure 3 demonstrated that the ability of P. aeruginosa PAO1 to form biofilm is affected by all cold-adapted supernatants deriving from sessile cultures with a rate of reduction between 30 and 50%. Only TAD1 P is able to reduce the P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilm more than 70%. An additional control experiment was performed for P. aeruginosa in order to exclude a dilution effect on the bacterial growth after the supplementation with each supernatant due to diverse nutrient concentration between the untreated bacteria and the treated ones. In particular, as growth medium was also used BHI 2X concentrated. This experiment was performed in addition to the standard condition because we noted an inhibitory effect on biofilm formation when P. aeruginosa was treated with all supernatants. Data obtained with BHI twofold concentrated were nearly superimposable excluding an effect due to the diverse nutrient concentration between the treated and untreated bacteria (data not shown).

FIGURE 3. Effect of Polar supernatant treatment on biofilm formation for P. aeruginosa PAO1. Data are reported as percentage of residual biofilm after the treatment. Biofilm formation was considered unaffected in the range 90–100%. Differences in mean absorbance were compared to the untreated control and considered statistically significant when p < 0.05 (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) according to Student’s t-test.

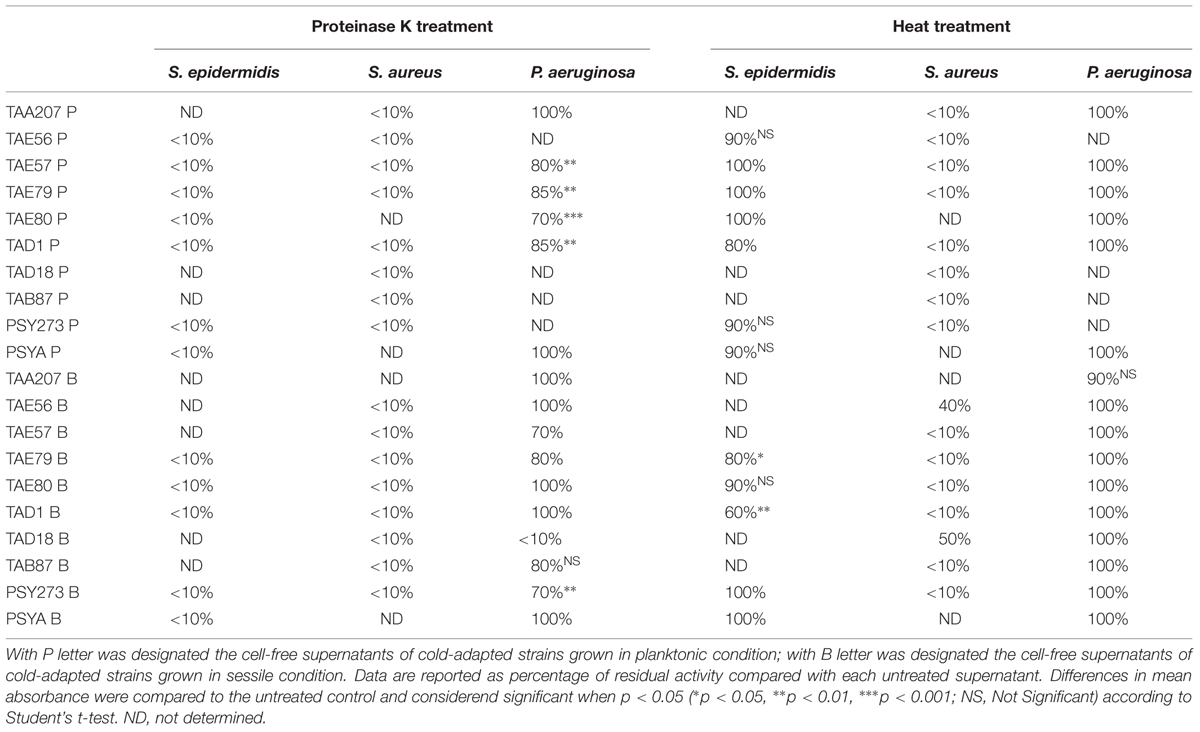

Physico-chemical Characterization of Anti-biofilm Compounds from Polar Bacteria

To determine a preliminary chemical characterization of biofilm-inhibiting compounds, cell free supernatants of cold-adapted bacteria were dispensed in several aliquots, and submitted to chemical (proteinase K) and physical (thermal) treatments. Percentage of biofilm inhibition of each treated aliquot was determined on S. epidermidis O-47, S. aureus 6538P and P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms (Table 3). Data are reported as the percentage of anti-biofilm activity remaining after each treatment compared to the effect of the same untreated supernatant. As shown in Table 3, the proteinase K treatment reduced the anti-biofilm activity of tested supernatants on S. epidermidis O-47 and S. aureus 6538P biofilms, while this treatment did not interfere with their anti-biofilm ability on P. aeruginosa PAO1 except for TAD18 B, indeed the proteinase K treatment reduced its anti-biofilm activity at value less than 10%.

TABLE 3. Effect of physico-chemical treatments on the anti-biofilm activity of cold-adapted bacteria supernatants on S. epidermidis O-47, S. aureus 6538P and P. aeruginosa PAO1, respectively.

Furthermore, thermal treatment at 50°C significantly reduced the anti-biofilm effect of almost all supernatants on S. aureus but did not impair their activity on P. aeruginosa and S. epidermidis. This latter suggests that each supernatant contains different molecules with anti-biofilm activity that works selectively and independently on different bacterial species.

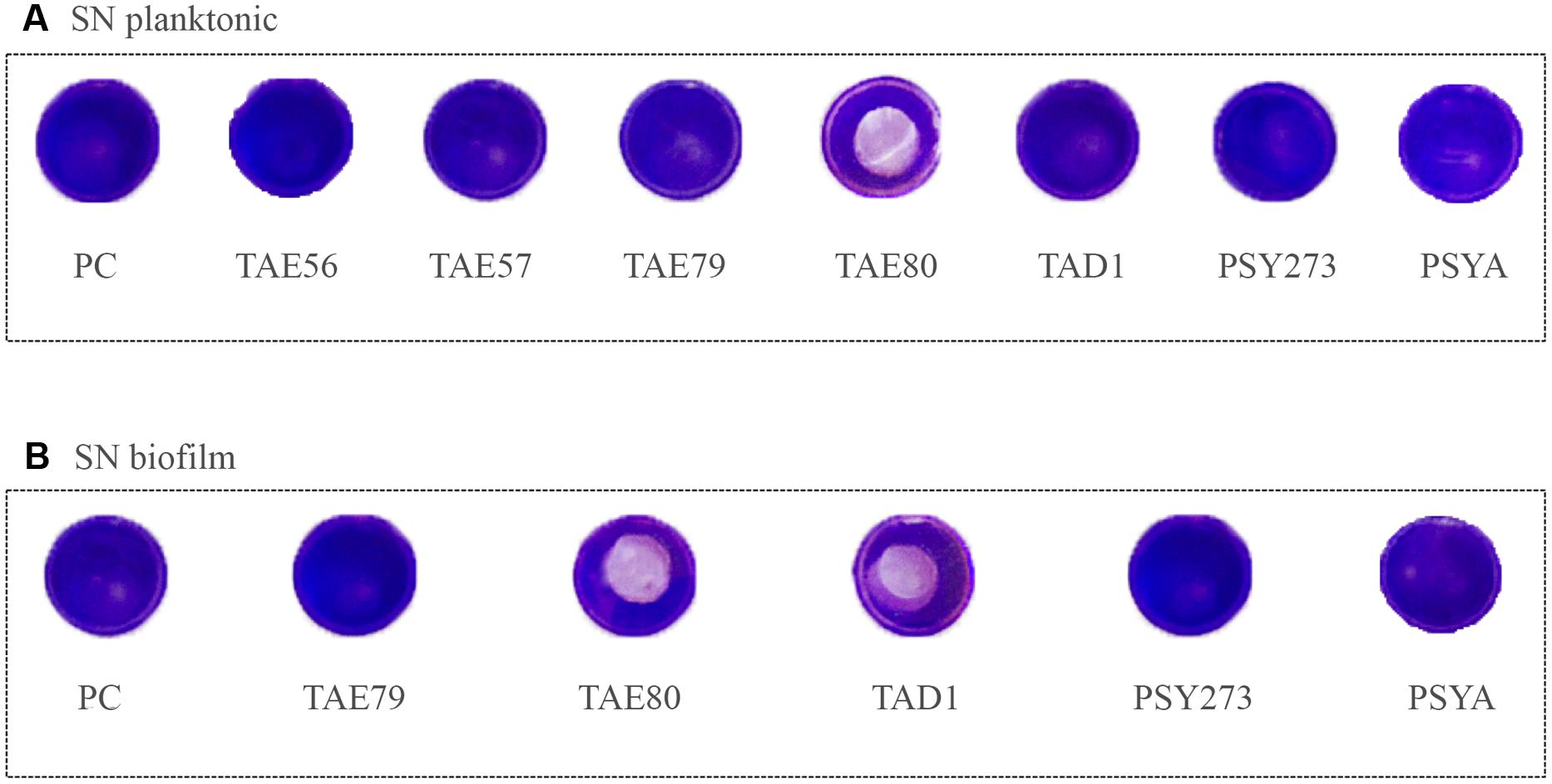

Anti-biofilm Surfactant Activity of Polar Compounds

To assess the ability of cell free Polar bacteria supernatants to modify the surface properties of an abiotic substrate, a surface coating assay was performed. Evaporation coating was used to deposit each supernatant onto the surface of polystyrene wells, and then the ability of the coated surfaces to repel biofilm formation by S. epidermidis O-47 was tested. This latter pathogen was selected for this assay as it is the strongest biofilm producer amongst the bacteria used in this work and because it is able to preferentially form biofilm on the surface while P. aeruginosa typically forms biofilm at the liquid/air interface.

As clearly visible in Figure 4, TAE80 supernatants derived from both planktonic and sessile cultures and TAD1 supernatant derived from only sessile growth, were able to repel biofilm formation specifically only in the area where the supernatants were deposited, indicating that they contain molecules acting as anti-biofilm surfactants.

FIGURE 4. Analysis of surfactant capability of each Polar supernatant on S. epidermidis O-47. The center of each well of a 24-well tissue-culture-treated polystyrene microtiter plate was coated with each supernatant. After evaporation, the wells were then filled with staphylococci and incubated at 37°C. Then wells were rinsed with water and stained with 1 ml of 0.1% crystal violet. Stained biofilms were rinsed with water and dried, and the wells were photographed. (A) Supernatants derived from planktonic growths. (B) Supernatants derived from biofilm growths.

Discussion

In this paper the attention was focused on anti-biofilm molecules produced by cold-adapted marine bacteria since they represent an untapped reservoir of biodiversity and a potential source of molecules able to inhibit pathogens biofilm formation. The target pathogens chosen were P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and S. epidermidis.

Biofilm is a key element in S. epidermidis, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa infectious processes, but the matrix composition and molecules involved in attachment, development and detachment phases in these three bacterial species, are very different (Joo and Otto, 2012). Further, pathways and regulation of quorum sensing systems in these three strains are deeply different (Solano et al., 2014).

In staphylococci biofilm formation depends on a complex interplay of several elements such as adhesins, extracellular matrix binding proteins, biofilm associated proteins, proteins involved in PIA synthesis (icaADBC), autolysins (Alt), etc. Staphylococcus strains used in this work were chosen on the basis of different characteristics. In particular, S. aureus ATCC 6538P is a reference strain for antimicrobial testing; S. aureus ATCC 25923 and ATCC 20372 are clinical isolates. As for their ability to form biofilm, S. aureus strains were classified as reported: ATCC 25923 is a strong biofilm producer, ATCC 6538P is a medium/strong biofilm producer and ATCC 20372 is a medium/weak biofilm producer according to Cafiso et al. (2007).

Several cold adapted bacteria produce molecules able to interfere with S. aureus biofilm formation. These molecules display a different efficiency on different S. aureus tested strains and in all strains the anti-biofilm molecules seems to be proteinaceous. On the contrary only few Polar strains produce anti-biofilm molecules active on S. epidermidis O-47 and RP62A biofilms, and none are able to interfere with S. epidermidis XX-17 biofilm formation. It is important to underline that XX-17 strain produces a biofilm characterized by a polysaccharide ica-independent poorly characterized so far.

Staphylococcus epidermidis RP62A is a reference strain isolated from infected catheter; S. epidermidis XX-17 and O-47 are clinical isolates. The clinical isolate O-47 is a naturally occurring non-functional agr mutant characterized by a frameshift mutation within agrC (Vuong et al., 2003) while the S. epidermidis XX-17 is an ica defective mutant (Artini et al., 2013). Determination of S. epidermidis biofilm formation showed a strong production for the O-47 strain, medium/strong production for the reference strain RP62A and a medium/weak biofilm formation for the XX-17 strain defined according to the literature (Cafiso et al., 2004). Moreover, the six staphylococcal strains considered here were previously investigated to assess the presence of genes coding for various proteins involved in adhesion and biofilm formation (Artini et al., 2013).

In P. aeruginosa the biofilm matrix is totally different, because the bacterium produces three exopolysaccharides, the glucose-rich Pel polysaccharide (Friedman and Kolter, 2004), the mannose-rich Psl polysaccharide (Friedman and Kolter, 2004), and alginate (Govan and Deretic, 1996). In particular, for P. aeruginosa we used the reference strain PAO1 since the biofilm characterization of this strain was previously reported (Yang et al., 2005).

The reported differences in biofilm features of the three pathogens could explain the different ability of cold adapted bacteria supernatants to impair their biofilm formation. It is interesting to note that, in all reported cases, the supernatants proved to be non-biocidal and specifically directed against biofilm.

All studied Polar strains are able to produce anti-biofilm molecules against P. aeruginosa biofilm. Furthermore in all cases the anti-biofilm molecules seems to have the same chemical-physical features (were not heat-labile and seem to have a non-protein nature), except in case of TAD18 B. These results could suggest that the molecule responsible for the anti-biofilm activity is the same for all cold-adapted strains. In particular, Polar anti-biofilm molecules involved in the inhibition of P. aeruginosa biofilm could be polysaccharides or a small molecule acting as quorum sensing inhibitors. Several studies have identified different bacterial polysaccharides and signaling molecules that inhibit biofilm formation by wide spectrum of bacteria including P. aeruginosa (Valle et al., 2006; Wittschier et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2009).

The increase of biofilm production following the treatment with such supernatants is an interesting result. This latter strengthens the hypothesis regarding the production of bacterial molecules able to regulate the biofilm formation inter- and intra- species in different environmental niches. The regulatory pathways of this phenotype could be linked to competition dynamics of extreme habitats (i.e., Polar niches). The identification of the molecules responsible for these mechanisms could be interesting and also open new perspectives for the control of bacterial biofilm formation. It is worth to note that “row” supernatants that we used represent a complex pool of chemical cues that could be characterized by different capabilities either responsible for impair biofilm formation and increase it.

Data reported in this paper demonstrate that anti-biofilm activity of cold-adapted bacteria supernatants deriving from planktonic and sessile cell cultures display several differences in terms of specificity and efficiency. Some biofilm-specific metabolites previously reported (Gjersing et al., 2007; Booth et al., 2011; Yeom et al., 2013) may exhibit an antagonist effect against competing microorganisms. Indeed, several studies showed that bacterial biofilm constitute untapped sources of natural bioactive molecules antagonizing adhesion or biofilm formation of other bacteria (Papa et al., 2013b; Rendueles et al., 2013). Furthermore, differences between activity of supernatants, derived from sessile and planktonic cultures, could be linked to a different concentration of active molecules produced in these two growth conditions. This latter could be particularly relevant if the active molecules are involved in quorum sensing signaling.

Moreover, in this paper we report that several cold-adapted strains (TAD1, TAE79, TAE80, PSY273 and PSYA), belonging to different genera, are able to produce different anti-biofilm molecules active against S. epidermidis, S. aureus and P. aeruginosa biofilms.

The preliminary chemical characterization of the anti-biofilm molecules indicates that the same bacterium produces different molecules active against different targets. For example, TAD1 produces a thermo-stable protein active against S. epidermidis biofilm, a thermo-labile protein active against S. aureus biofilm, and a non-proteinaceus molecule able to impair P. aeruginosa biofilm. Furthermore the supernatants of TAD1 deriving from biofilm and planktonic growth showed also a different behavior in surface coating assay, suggesting the production of an anti-biofilm surfactant molecule only when TAD1 is grown in sessile form. Also for the supernatants deriving from TAE80 growths were evidenced the presence of different anti-biofilm molecules that are able to specifically act against the different bacterial species tested. In particular, we analyzed the dose dependent profile of TAE80 supernatants deriving form planktonic and biofilm growths tested against strongest biofilm producers belonging the three different species (Supplementary Figure S1). Both TAE80 supernatants (TAE80B and TAE80P) showed an anti-biofilm activity clearly dose-dependent against S. aureus 25923 and S. epidermidis O-47 while their activity against P. aeruginosa does not seem to be dose-dependent.

The ability of cold-adapted marine bacteria to produce several anti-biofilm molecules could suggest that the capacity to avoid the biofilm and colonization of competitor bacteria is a selective advantage in this extreme environment. Besides their ecological meaning, the anti-biofilm molecules from cold-adapted bacteria may have interesting biomedical applications combined with conventional antibiotics in order to eradicate biofilm infection.

Funding

This work was supported by Programma Nazionale di Ricerche in Antartide 2013/B1.04 Tutino. This work was supported by Programma Operativo Nazionale Ricerca e Competitività 2007–2013 (D. D. Prot. n. 01/Ric. del 18.1.2010) – PON01_01802.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01333

FIGURE S1 | A dose-dependent effect on biofilm formation of S. aureus 25923 (A), S. epidermidis O-47 (B), P. aeruginosa PaO1 (C) in the presence of scalar concentration of TAE80 B and TAE80 P, respectively (starting from 50%). Results are representative of three independent experiments. UN, untreated samples.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Alhanout, K., Brunel, J. M., Dubus, J. C., Rolain, J. M., and Andrieu, V. (2011). Suitability of a new antimicrobial aminosterol formulation for aerosol delivery in cystic fibrosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66, 2797–2800. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr380

Artini, M., Cellini, A., Scoarughi, G. L., Papa, R., Tilotta, M., Palma, S., et al. (2015). Evaluation of contact lens multipurpose solutions on bacterial biofilm development. Eye Contact Lens 41, 177–182.

Artini, M., Papa, R., Scoarughi, G. L., Galano, E., Barbato, G., Pucci, P., et al. (2013). Comparison of the action of different proteases on virulence properties related to the staphylococcal surface. J. Appl. Microbiol. 114, 266–277. doi: 10.1111/jam.12038

Bakermans, C., Ayala-del-Río, H. L., Ponder, M. A., Vishnivetskaya, T., Gilichinsky, D. A., Thomashow, M. F., et al. (2006). Psychrobacter cryohalolentis sp. nov. and Psychrobacter arcticus sp. nov., isolated from Siberian permafrost. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56, 1285–1291. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64043-0

Booth, S. C., Workentine, M. L., Wen, J., Shaykhutdinov, R., Vogel, H. J., Ceri, H., et al. (2011). Differences in metabolism between the biofilm and planktonic response to metal stress. J. Proteome Res. 10, 3190–3199. doi: 10.1021/pr2002353

Bowman, J. P. (2007). Bioactive compound synthetic capacity and ecological significance of marine bacterial genus pseudoalteromonas. Mar. Drugs 5, 220–241. doi: 10.3390/md504220

Brook, I. (1999). Bacterial interference. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 25, 155–172. doi: 10.1080/10408419991299211

Cafiso, V., Bertuccio, T., Santagati, M., Campanile, F., Amicosante, G., and Perilli, M. G. (2004). Presence of the ica operon in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis and its role in biofilm production. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10, 1081–1088. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01024.x

Cafiso, V., Bertuccio, T., Santagati, M., Demelio, V., Spina, D., Nicoletti, G., et al. (2007). Agr-Genotyping and transcriptional analysis of biofilm-producing Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 51, 220–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00298.x

Debbab, A., Aly, A. H., Lin, W. H., and Proksch, P. (2010). Bioactive compounds from marine bacteria and fungi. Microb. Biotechnol. 3, 544–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00179.x

Dohar, J. E., Hebda, P. A., Veeh, R., Awad, M., Costerton, J. W., Hayes, J., et al. (2009). Mucosal biofilm formation on middle-ear mucosa in a nonhuman primate model of chronic suppurative otitis media. Laryngoscope 115, 1469–1472. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000172036.82897.d4

Epstein, A. K., Wong, T. S., Belisle, R. A., Boggs, E. M., and Aizenberg, J. (2012). Liquid-infused structured surfaces with exceptional anti-biofouling performance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109, 13182–13187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201973109

Friedman, L., and Kolter, R. (2004). Two genetic loci produce distinct carbohydrate-rich structural components of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. J. Bacteriol. 186, 4457–4465. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.14.4457-4465.2004

Gjersing, E. L., Herberg, J. L., Horn, J., Schaldach, C. M., and Maxwell, R. S. (2007). NMR metabolomics of planktonic and biofilm modes of growth in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Anal. Chem. 79, 8037–8045. doi: 10.1021/ac070800t

Govan, J. R., and Deretic, V. (1996). Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol. Rev. 60, 539–574.

Groudieva, T., Grote, R., and Antranikian, G. (2003). Psychromonas arctica sp. nov., a novel psychrotolerant, biofilm-forming bacterium isolated from Spitzbergen. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53, 539–545. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02182-0

Hall-Stoodley, L., and Stoodley, P. (2009). Evolving concepts in biofilm infections. Cell. Microbiol. 11, 1034–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01323.x

Heilmann, C., Gerke, C., Perdreau-Remington, F., and Götz, F. (1996). Characterization of Tn917 insertion mutants of Staphylococcus epidermidis affected in biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 64, 277–282.

Høiby, N., Ciofu, O., Johansen, H. K., Song, Z. J., Moser, C., Jensen, P. O., et al. (2011). The clinical impact of bacterial biofilms. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 3, 55–65. doi: 10.4248/IJOS11026

Joo, H. S., and Otto, M. (2012). Molecular basis of in vivo biofilm formation by bacterial pathogens. Chem. Biol. 19, 1503–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.10.022

Kim, H. S., Kim, S. M., Lee, H. J., Park, S. J., and Lee, K. H. (2009). Expression of the cpdA gene, encoding a 3′,5′-cyclic AMP (cAMP) phosphodiesterase, is positively regulated by the cAMP-cAMP receptor protein complex. J. Bacteriol. 191, 922–930. doi: 10.1128/JB.01350-08

López, D., Vlamakis, H., and Kolter, R. (2010). Biofilms. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2:a000398. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000398

Nicholson, T. L., Shore, S. M., Smith, T. C., and Frana, T. S. (2013). Livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (la-mrsa) isolates of swine origin form robust biofilms. PLoS ONE 8:e73376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073376

Papa, R., Artini, M., Cellini, A., Tilotta, M., Galano, E., Pucci, P., et al. (2013a). A new anti-infective strategy to reduce the spreading of antibiotic resistance by the action on adhesion-mediated virulence factors in Staphylococcus aureus. Microb. Pathog. 63, 44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2013.05.003

Papa, R., Parrilli, E., Sannino, F., Barbato, G., Tutino, M. L., Artini, M., et al. (2013b). Anti-biofilm activity of the Antarctic marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis TAC125. Res. Microbiol. 164, 450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.01.010

Papaleo, M. C., Romoli, R., Bartolucci, G., Maida, I., Perrin, E., Fondi, M., et al. (2013). Bioactive volatile organic compounds from Antarctic (sponges) bacteria. Natl. Biotechnol. 30, 824–838. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2013.03.011

Parrilli, E., Papa, R., Carillo, S., Tilotta, M., Casillo, A., Sannino, F., et al. (2015). Anti-biofilm activity of Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis TAC125 against Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm: evidence of a signal molecule involvement? Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 28, 104–113. doi: 10.1177/0394632015572751

Rendueles, O., Kaplan, J. B., and Ghigo, J. M. (2013). Antibiofilm polysaccharides. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 334–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02810.x

Rogers, K. L., Fey, P. D., and Rupp, M. E. (2009). Coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections. Infect. Dis. Clin. North. Am. 23, 73–98. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2008.10.001

Saxena, S., Banerjee, G., Garg, R., and Singh, M. (2014). Comparative study of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients of lower respiratory tract infection. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 8, DC09–DC11. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7808.4330

Solano, C., Echeverz, M., and Lasa, I. (2014). Biofilm dispersion and quorum sensing. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 18, 96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.02.008

Valle, J., Da Re, S., Henry, N., Fontaine, T., Balestrino, D., Latour-Lambert, P., et al. (2006). Broad-spectrum biofilm inhibition by a secreted bacterial polysaccharide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 12558–12563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605399103

Vishnivetskaya, T., Kathariou, S., McGrath, J., Gilichinsky, D., and Tiedje, J. M. (2000). Low-temperature recovery strategies for the isolation of bacteria from ancient permafrost sediments. Extremophiles. 4, 165–173. doi: 10.1007/s007920070031

Vuong, C., Gerke, C., Somerville, G. A., Fischer, E. R., and Otto, M. (2003). Quorum-sensing control of biofilm factors in Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Infect. Dis. 188, 706–718. doi: 10.1086/377239

Wang, C., Fan, J., Niu, C., Wang, C., Villaruz, A. E., Otto, M., et al. (2010). Role of spx in biofilm formation of Staphylococcus epidermidis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 59, 152–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00673.x

Wang, C., Li, M., Dong, D., Wang, J., Ren, J., Otto, M., et al. (2007). Role of ClpP in biofilm formation and virulence of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Microbes. Infect. 9, 1376–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.06.012

Wittschier, N., Lengsfeld, C., Vorthems, S., Stratmann, U., Ernst, J. F., Verspohl, E. J., et al. (2007). Large molecules as anti-adhesive compounds against pathogens. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 59, 777–786. doi: 10.1211/jpp.59.6.0004

Yang, W., Shi, L., Jia, W. X., Yin, X., Su, J. Y., Kou, Y., et al. (2005). Evaluation of the biofilm-forming ability and genetic typing for clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus-based PCR. Microbiol. Immunol. 49, 1057–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2005.tb03702.x

Keywords: Polar bacteria, anti-virulence, anti-biofilm molecules, anti-adhesive, non-biocidal agents

Citation: Papa R, Selan L, Parrilli E, Tilotta M, Sannino F, Feller G, Tutino ML and Artini M (2015) Anti-biofilm Activities from Marine Cold Adapted Bacteria Against Staphylococci and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 6:1333. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01333

Received: 11 August 2015; Accepted: 13 November 2015;

Published: 14 December 2015.

Edited by:

Márcia Vanusa Da Silva, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, BrazilReviewed by:

Robert J. C. McLean, Texas State University, USAJoanna S. Brooke, DePaul University, USA

Copyright © 2015 Papa, Selan, Parrilli, Tilotta, Sannino, Feller, Tutino and Artini. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marco Artini, bWFyY28uYXJ0aW5pQHVuaXJvbWExLml0

Rosanna Papa

Rosanna Papa Laura Selan

Laura Selan Ermenegilda Parrilli

Ermenegilda Parrilli Marco Tilotta

Marco Tilotta Filomena Sannino2

Filomena Sannino2 Georges Feller

Georges Feller Maria L. Tutino

Maria L. Tutino Marco Artini

Marco Artini