Abstract

Introduction:

Mycoplasma pneumoniae (M. pneumoniae) is a leading pathogen of pediatric pneumonia, yet its epidemiological profile in Chengdu remains understudied. This study aimed to analyze the epidemiological trends of M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates among children in Chengdu from 2017 to 2024, encompassing periods before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic, and to assess associated changes in respiratory disease patterns.

Methods:

We retrospectively analyzed clinical diagnoses and M. pneumoniae antibody test results from 222,364 children with respiratory infections treated in the emergency, outpatient, and inpatient departments of Chengdu Women and Children's Central Hospital (January 2017–December 2024). Local temperature and humidity data were concurrently collected. Epidemiological trends in M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates were evaluated by year, sex, age, season, and climate parameters, alongside shifts in respiratory disease composition among M. pneumoniae-positive children.

Results:

The M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates exhibited an overall upward trend, with three epidemic peaks (2017, 2019, and 2023–2024) and a notable decline during the pandemic. Females showed higher susceptibility than males. Outpatients aged 3–6 years and inpatients aged 0–3 years were most vulnerable pre-pandemic; however, post-pandemic, M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates increased with age (0–6 years). Seasonal peaks typically occurred in autumn, but during the mid-to-late pandemic, winter-autumn alternation was observed. Early-pandemic humidity positively correlated with M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates. Post-pandemic, asthma replaced post-infection cough as the third most common outpatient diagnosis, while inpatient diagnoses were dominated by pneumonia and severe pneumonia, the latter showing a significant rise in proportion.

Discussion:

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, a substantial increase of Mycoplasma pneumoniae (M. pneumoniae) antibody positive rates was observed among pediatric populations in Chengdu beginning in 2023. This study presents a descriptive analysis of serum antibody detection results, offering baseline epidemiological data to inform prevention and control strategies for M. pneumoniae infections among children in the Chengdu region.

Introduction

Respiratory infections are among the most common diseases worldwide, affecting individuals of all ages. Mycoplasma pneumoniae (M. pneumoniae), a cell wall-free obligate parasitic pathogen, occupies an intermediate position between bacteria and viruses and is a significant cause of Acute Respiratory Infections (ARIs) in children. M. pneumoniae infections can lead to severe upper and lower respiratory tract symptoms, in excess of 10% of cases progressing to pneumonia and potentially life-threatening complications (Yang et al., 2024; Hu et al., 2023). Globally, M. pneumoniae outbreaks occur cyclically every 3–7 years in specific regions, with each outbreak lasting approximately 1–2 years (Yamazaki and Kenri, 2016). Following the COVID-19 outbreak in late 2019, countries implemented Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs), including school closures, social distancing, mask mandates, enhanced hand hygiene, and restrictions on outdoor activities. These measures effectively curbed the spread of COVID-19. However, since December 2022, China began gradually relaxing NPIs, leading to significant shifts in the prevalence of M. pneumoniae infections (Baker et al., 2020). Since June 2023, an early peak in M. pneumoniae infections among children has been observed in multiple regions of China, particularly in September. The surge in cases has been accompanied by more severe clinical manifestations, with many infections involving macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae strains, which are associated with worse clinical outcomes (Yan et al., 2024).

The prevalence of M. pneumoniae infections in children exhibits regional variations due to differences in climate, culture, and geography (Wang et al., 2025). However, limited studies have examined changes in M. pneumoniae infection patterns before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, and data on M. pneumoniae epidemiology in Chengdu remain scarce. This study retrospectively analyzed the epidemiological trends of M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates in children with Respiratory Tract Infections (RTIs) at Chengdu Women and Children's Central Hospital from January 2017 to December 2024. The findings provide valuable baseline data for optimizing region-specific prevention and control strategies against M. pneumoniae infections in children.

Materials and methods

Materials

The clinical diagnoses and M. pneumoniae antibody test results of two lakhs twenty two thousand three hundred and sixty four children with Respiratory Tract Infections (RTIs), including eighty nine thousand two hundred and sixty eight hospitalized cases, were retrospectively analyzed at the outpatient and emergency department of Chengdu Women and Children's Central Hospital from January 2017 to December 2024. The cohort also comprised one lakh thirty three thousand hundred and seventy eight outpatients; And with one lakh twenty one thousand four hundred and eighty eight males and one lakh eight hundred and seventy six females with a sex ratio of 1.2:1. Age groups included infants and young children (0 ≤ age ≤ 3 years old), preschoolers (3 < age ≤ 6 years old) and school-age children (6 < age ≤ 14 years old). Climate data (temperature and humidity, 2017-2024) were sourced from the Sichuan Meteorological Bureau's official records. The study period was divided into pre-pandemic (2017-2019), pandemic (2020-2022), and post-pandemic (2023-2024).

Inclusion criteria

(1) Clinical diagnosis of respiratory tract infection according to WHO criteria; (2) Availability of M. pneumoniae antibody testing; (3) Complete M. pneumoniae antibody test results and demographic data; (4) Age 0-14 years; (5) Presence of characteristic clinical manifestations (e.g., paroxysmal cough, persistent fever ≥38 °C, or radiologically confirmed pulmonary abnormalities); (6) No record of M. pneumoniae antibody positivity in the prior 6 months; (7) Single serum M. pneumoniae antibody titer ≥1:160 (PA method), indicating a positive result.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by age, gender, year, month, and climate. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages, and the Chi-square test (χ2) was used for comparisons. Bivariate correlation analysis was performed to assess relationships. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 27.0 software.

Results

Analysis of gender and age differences in children with M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates before, during and after the pandemic

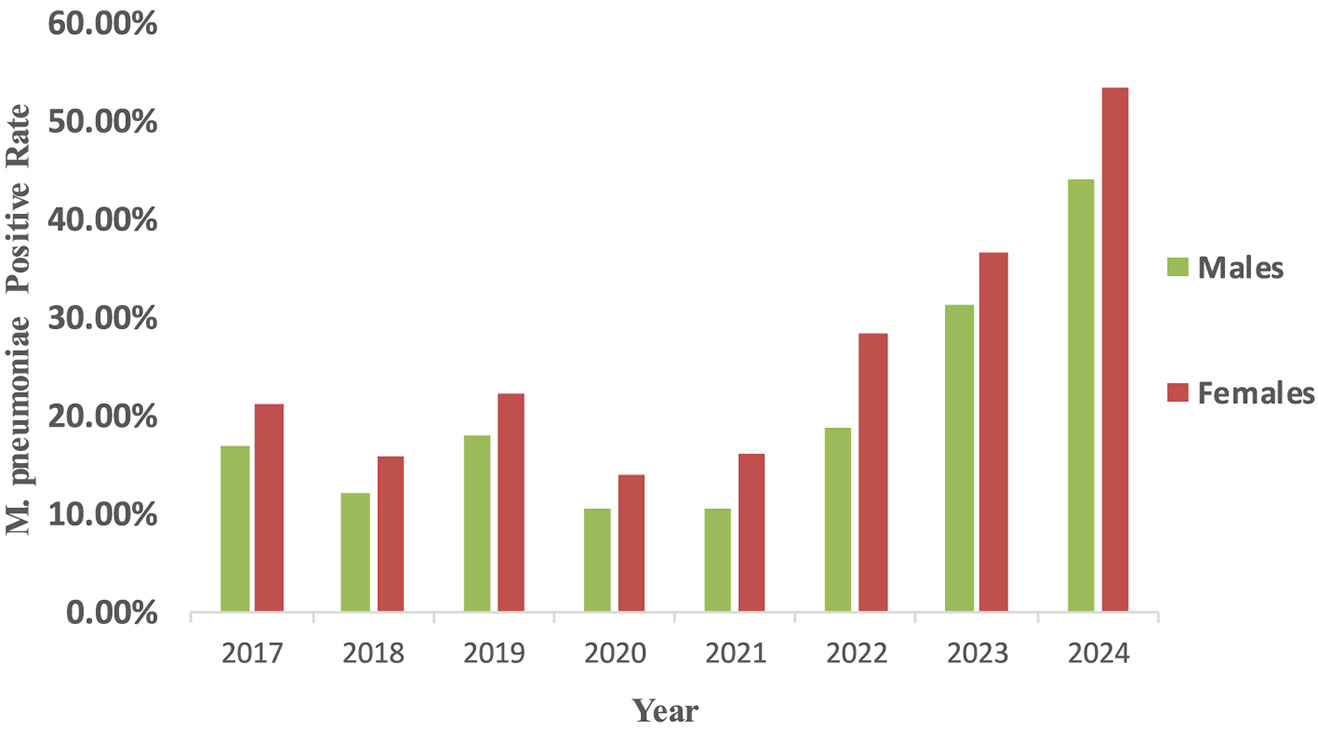

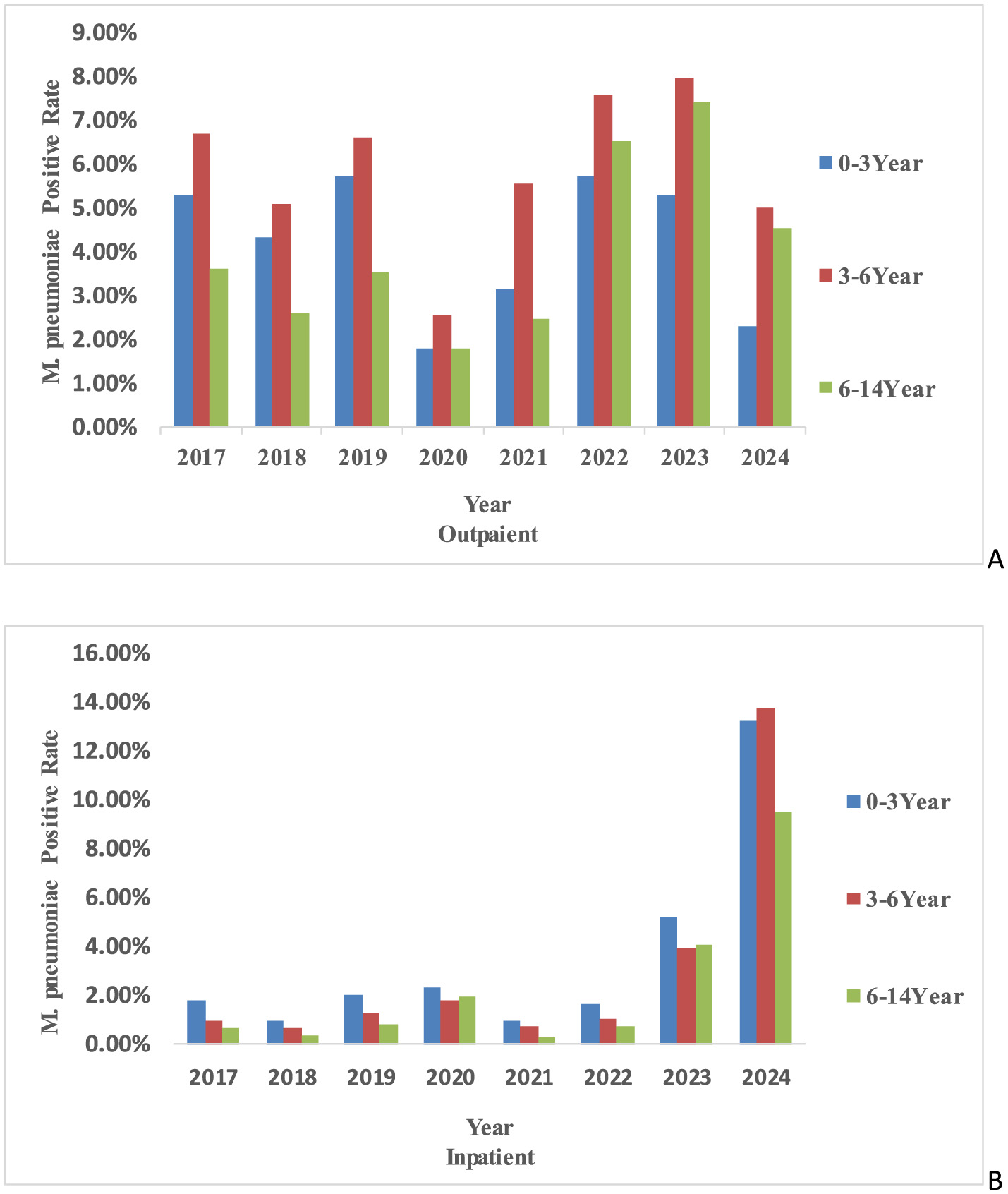

From 2017 to 2024, the M. pneumonia antibody positive rates was significantly higher in female children than in males (χ2 = 135, P < 0.001) (Figure 1). Age-specific differences in M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates were also observed during this period (χ2 = 693, P < 0.001). Age groups included one lakh twenty one thousand three hundred and ninety eight infants and young children, sixty six thousand hundred and seventy three preschoolers and thirty four thousand eight hundred and ninety three school-age children. Notably, the antibody positive rates increased with age (0-6 years) in the later stages of the pandemic. Pre-pandemic, preschool-aged children (3–6 years) were the most affected group, followed by infants and young children (0–3 years) and school-age children (6–14 years). Post-pandemic, the antibody positive rates among school-age children surpassed that of infants and young children, becoming the second most affected group after preschoolers (Figure 2A). Among hospitalized children, preschoolers had higher M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates than infants and young children in 2024 (Figure 2B).

Figure 1

Epidemiological changes of M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates according to patient gender. M. pneumoniae positive rate were computed as the proportion of M. pneumoniae antibody positive individuals among all tested individuals of each gender. The detection of serum antibodies merely reflects prior exposure to M. pneumoniae and does not constitute definitive evidence of acute infection.

Figure 2

The age-specific trends of M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates. (A) The age-specific trends in outpatient M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates in different years. (B) Age-specific trends in inpatient M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates in different years.

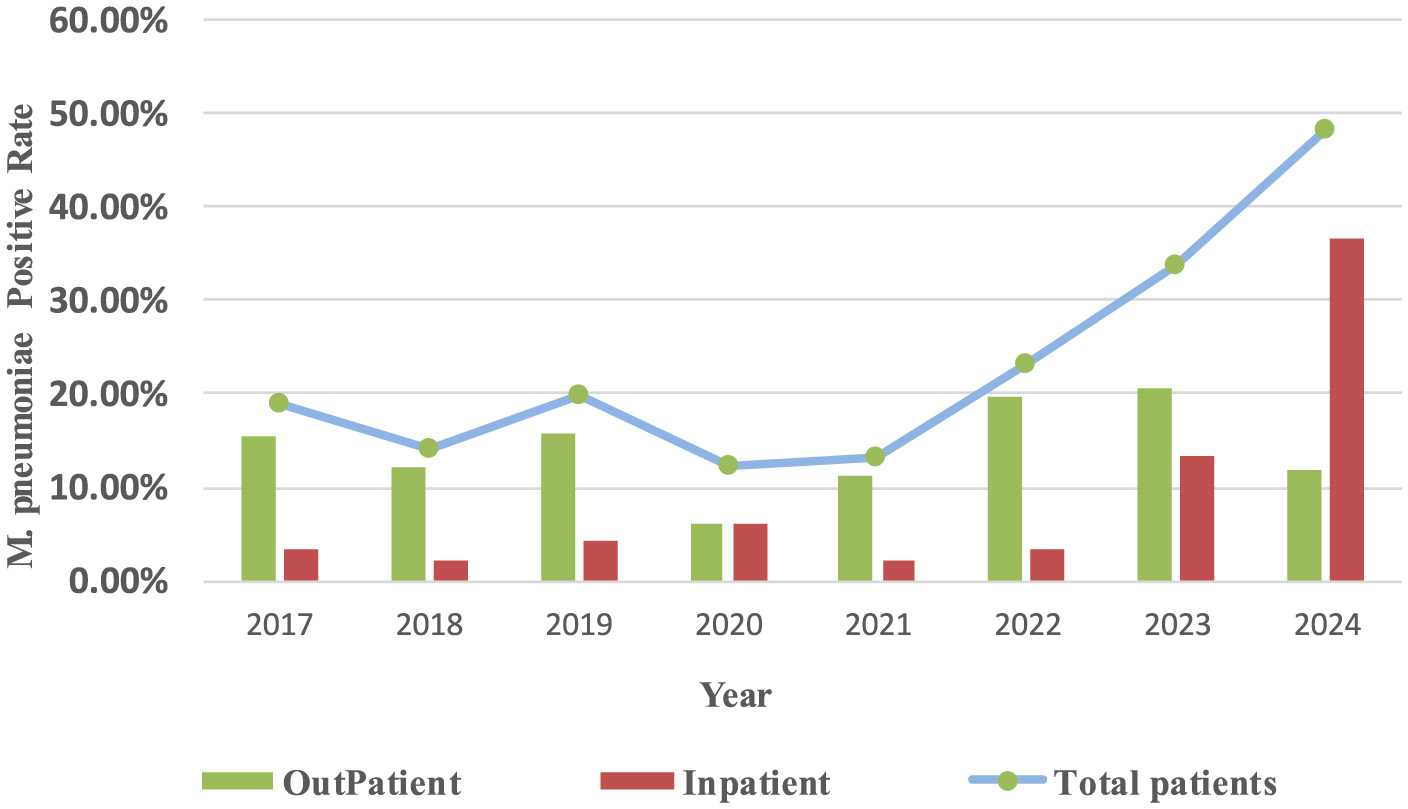

Analysis of differences in M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates across years before, during and after the pandemic

From 2017 to 2024, the M. pneumoniae-positive rates in outpatients were 14.47%, 12.69%, and 16.18% during the pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic periods, respectively. For inpatients, the corresponding rates were 3.24%, 3.82%, and 24.97%. Pre-pandemic, M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates exhibited a biennial increase, with epidemic peaks occurring in 2017, 2019 and 2023–2024. Post-pandemic, the M. pneumoniae-positive rate continued to rise (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Yearly trends in M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates in different hospitalization methods and total positive rates.

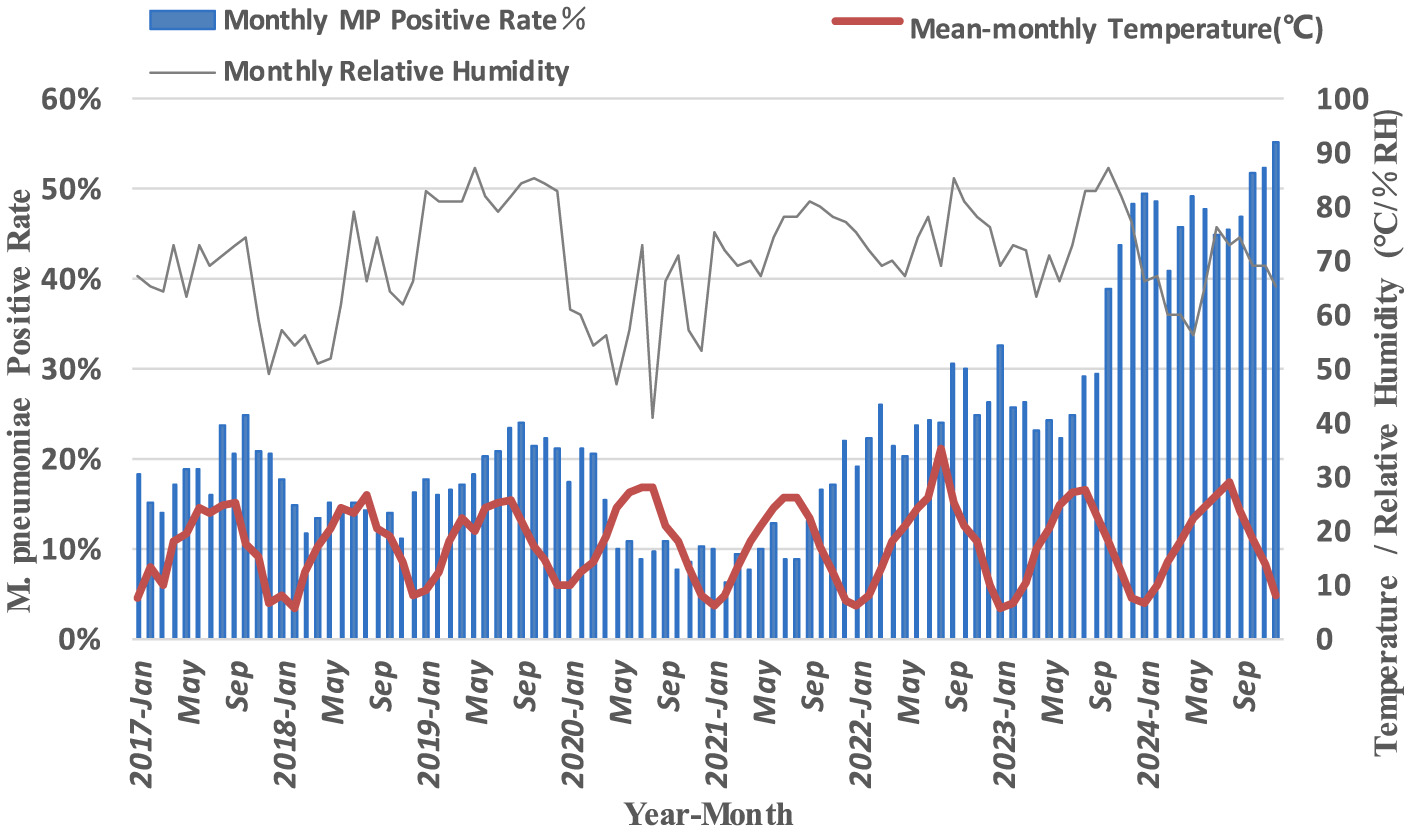

Analysis of monthly M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates and environmental temperature and humidity before, during and after the pandemic

Significant monthly variations in M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates were observed from 2017 to 2024 (P < 0.001). Pre-pandemic, antibody positive rates were consistently higher from August to December each year. Post-pandemic, the peak duration of M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates extended, though no significant correlation was found with monthly temperature changes (P > 0.05) (Figure 4). A positive correlation was identified between M. pneumoniae-positive rates and environmental humidity before the pandemic (P < 0.01). However, this correlation was not observed in the post-pandemic period (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Figure 4

Monthly M. pneumoniae antibody positive rate and environmental temperature and humidity.

Table 1

| Time | Mean-monthly temperature | Monthly relative humidity |

|---|---|---|

| 2017/1-2019/12 | 0.175 | 0.463** |

| 2020/1-2022/12 | 0.034 | 0.358* |

| 2023/1-2024/12 | −0.183 | −0.226 |

Correlation analysis between monthly M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates and environmental temperature and humidity.

** P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

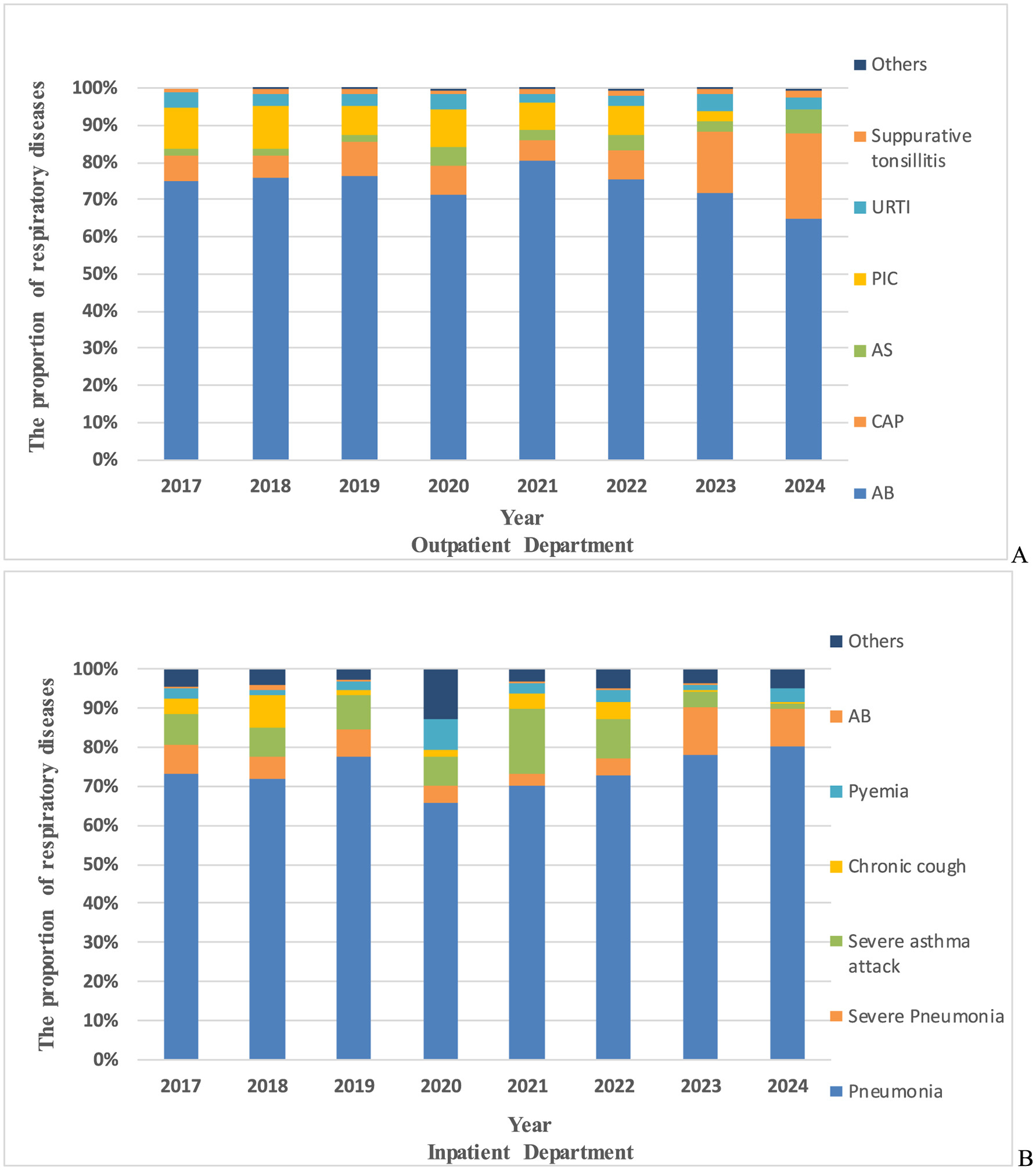

Comparison of the proportion of respiratory diseases in children with M. pneumoniae antibody positive

Significant differences were observed in the spectrum of respiratory diseases associated with M. pneumoniae antibody positive among outpatients and inpatients from 2017 to 2024 (χ2 = 2,447, P < 0.001). Among outpatients, the top three diagnoses for M. pneumoniae antibody positive before and during the pandemic were Acute Bronchitis (AB), pneumonia, and Post-Infectious Cough (PIC). However, post-pandemic, asthma replaced PIC as the third most common diagnosis, with AB and pneumonia remaining the top two (Figure 5A). For hospitalized patients, the leading M. pneumoniae-related diagnoses before the pandemic were pneumonia, severe pneumonia, and severe asthma attacks. During the pandemic, the ranking shifted slightly, with pneumonia remaining the most common, followed by severe asthma attacks and severe pneumonia. Post-pandemic, the primary diagnoses among hospitalized M. pneumoniae-positive children were pneumonia and severe pneumonia, with a notable increase in the proportion of severe pneumonia cases (Figure 5B).

Figure 5

The proportion of respiratory diseases in M. pneumoniae antibody positive. (A) The proportion of respiratory diseases in M. pneumoniae antibody positive in outpatient department. (B) The proportion of respiratory diseases in M. pneumoniae antibody positive in inpatient department. AB, acute bronchitis; PIC, post-infectious cough; CAP, community acquired pneumonia; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection; AS, asthma; others, respiratory diseases other than these.

Discussion

This study identified significant gender differences in M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates, with female children exhibiting higher rates than males, consistent with previous findings (Mao et al., 2025; Ai et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2021). This suggests that females may be more susceptible to be positive for M. pneumoniae antibodies, potentially due to differences in activity and social behaviors. Female children may engage more frequently in indoor group activities, which could facilitate M. pneumoniae transmission in enclosed environments. While M. pneumoniae primarily affects children, it can infect individuals of all ages, including infants and the elderly. Previous studies indicate that M. pneumonia-positive predominantly occur in children over 5 years old (Zhang et al., 2025). During 2017–2024, preschool-aged children were the most susceptible outpatient group to M. pneumoniae antibody positive in Chengdu. Pre-pandemic, infants had the second-highest antibody positive rates after preschoolers. However, during and after the pandemic, M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates increased with age (0-6 years), and by 2022–2024, school-age children exhibited higher antibody positive rates than infants, aligning with studies from Wuhan, Henan, and Chengdu (Mao et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023). Among hospitalized children, infants were the most susceptible group, with preschoolers showing higher antibody positive rates than school-age children, consistent with prior research. Notably, in 2020 and 2023, school-age children had higher M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates than preschoolers, possibly due to their broader and more active social interactions following the relaxation of NPIs (Miao et al., 2025). Additionally, the rise in macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae strains, which peaked in Taiwan in 2020 (Wu et al., 2024), may have contributed to increased hospitalization rates among school-age children due to treatment challenges. This trend is further substantiated by recent findings demonstrating a significant escalation in the mutation rate of macrolide resistance loci in M. pneumoniae across mainland China, with 2023 data showing a marked increase compared to the 2019 to 2022 surveillance period (Xu et al., 2024). Geographical and pandemic-related factors also influenced age-specific susceptibility. For instance, in Anhui, M. pneumoniae-positive cases were primarily observed in children aged 7–10 years pre-pandemic, shifting to 6–14 years post-pandemic, with low antibody positive rates among infants (Chen et al., 2024), consistent with patterns in France and Denmark (Edouard et al., 2024; Nordholm et al., 2024). Conversely, in Shanghai, post-pandemic M. pneumoniae-positive rates increased among infants, suggesting a trend toward younger susceptible age groups (Zhu et al., 2024). These variations may be attributed to regional differences in childcare practices, school environments, and climatic conditions. Immature immune systems, crowded indoor settings, and close contact among children likely exacerbate M. pneumoniae transmission. Furthermore, air quality and environmental factors, such as PM 2.5 and PM 10 levels, have been linked to M. pneumoniae-positive, as these pollutants can carry respiratory pathogens (Gu et al., 2024).

This study also revealed that M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates in Chengdu peaked in 2017, 2019 and 2023–2024, consistent with previous reports (Wang et al., 2024). Pre-pandemic, M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates exhibited a biennial increase, but during the pandemic, outpatient rates declined significantly, with a slight rebound in 2022. Our study revealed a significant decline in M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates during 2020. This epidemiological pattern may be attributed to the comprehensive infection control measures and stringent case management policies enacted during the pandemic period. In China, public health strategies prioritized the treatment of severe COVID-19 cases while enforcing standardized isolation protocols for mild infections. A research reveal that during the pandemic, a proportion of COVID-19 cases were managed outside hospital settings. Furthermore, surveillance limitations were evident, as a number of symptomatic individuals remained untested, potentially resulting in underreporting of positve rates (Wu et al., 2025). This observation may similarly apply to M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates. And the overall decline in M. pneumoniae antibody positive during the pandemic also has been attributed to NPIs, such as personal protective measures and social distancing. A study has shown the M. pneumoniae positive rate during the NPI phase was significantly lower than that during the non-NPI phase, our results align well with these observations (Jiang et al., 2024). Post-pandemic, both outpatient and inpatient M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates rose sharply, with inpatient rates surpassing outpatient rates. This trend may reflect increased macrolide resistance and the “immunity debt” hypothesis. Supporting this notion, recent surveillance data from Henan and Beijing, China, demonstrate a marked increase in the proportion of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae isolates since 2023 compared to pre-pandemic levels (Qi et al., 2025; Jia et al., 2024). The latter hypothesis posits that prolonged implementation of NPIs during the COVID-19 pandemic substantially reduced population-wide pathogen exposure, consequently impairing immune surveillance and increasing susceptibility to M. pneumoniae positive. This hypothesis has gained empirical support through observed epidemiological patterns of various respiratory pathogens, most notably Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), during their post-pandemic resurgence periods (Munro and House, 2024), thereby corroborating our current findings. Seasonal patterns of M. pneumoniae antibody positive also shifted during the study period. Pre-pandemic, antibody positive rates peaked in autumn (August–October), consistent with findings from Beijing (Wang et al., 2022). However, during and after the pandemic, seasonal peaks alternated between winter and autumn, extending into the following spring. Notably, in 2022, the peak shifted to spring and summer, likely due to pandemic-related disruptions in typical seasonal transmission patterns (Edouard et al., 2024). Regional variations in seasonal trends were also observed. For example, in Shanghai and Wuhan, M. pneumoniae-positive rates peaked in autumn and winter 2023, persisting into spring 2024 (Edouard et al., 2024; Mao et al., 2025), while in Northeast China and Inner Mongolia, peaks shifted from winter and spring to summer and autumn (Wang et al., 2024). These changes underscore the impact of COVID-19 on M. pneumoniae seasonality (Ai et al., 2024). Early in the pandemic, environmental humidity positively correlated with M. pneumoniae positive rates (Wagatsuma, 2024), a study by Japanese scientists has identified a significant positive association between the incidence of M. pneumoniae positive rates and weekly average temperature and humidity levels (Onozuka et al., 2009). But our finding has shown that this relationship weakened post-pandemic, possibly due to increased parental awareness and interventions such as air purifiers and cleaning behaviors (Liu et al., 2025).

The spectrum of respiratory diseases among M. pneumoniae-positive children also evolved post-pandemic. In outpatient settings, asthma replaced post-infectious cough (PIC) as the third most common diagnosis. This shift may reflect reduced exposure to environmental pathogens during the pandemic, leading to immune dysregulation and heightened allergic responses upon re-exposure (Sampath et al., 2023). Current research substantiates that children with acute asthma had significantly higher seropositivity for anti- M. pneumoniae IgM antibodies than children with stable asthma (Liu et al., 2021) and asthmatic children with M. pneumoniae-positive exhibit elevated serum levels of both IL-4 and IFN-γ (Xiao and Hou, 2025). Notably, IL-4 has been clinically established as a key mediator associated with asthma susceptibility and disease pathogenesis (Jin and Zheng, 2022). Among hospitalized children, severe pneumonia replaced asthma as the second most common diagnosis, likely due to the rise in macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae strains and the “immunity debt” phenomenon, which predisposed children to more severe respiratory complications (Miao et al., 2025; Qiu et al., 2024). A study has shown that the clinical manifestations of drug-resistant M. pneumoniae pneumonia are more severe and the hospital stay is longer (Jiang et al., 2023). Similar trends were observed in Zhejiang, Guangzhou, Northeast China, and Inner Mongolia, where pneumonia and severe pneumonia predominated among hospitalized M. pneumoniae-positive children post-pandemic (Wang et al., 2024; Qiu et al., 2024). These findings highlight the need for heightened vigilance and early intervention in managing M. pneumoniae-related respiratory diseases, particularly pneumonia, severe pneumonia, and asthma, in the post-pandemic era. This study has several limitations. First, this observational study utilized single-point serum M. pneumoniae antibody detection as a surveillance tool, rather than employing laboratory-confirmed acute infection criteria through paired serological testing or PCR confirmation, which cannot distinguish between acute infection and persistent antibodies from previous exposures. This approach may consequently overestimate the true prevalence of acute M. pneumoniae infections in the pediatric population. Second, data were limited to Chengdu Women and Children's Central Hospital, excluding M. pneumoniae resistance gene profiles and cases from other regional hospitals. The relatively narrow geographic scope and sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Given the methodological constraints of single-timepoint serology in distinguishing acute versus historical M. pneumoniae infections, our reported positivity rates represent the combined effects of population seroprevalence and new infections. Future investigations should integrate pathogen genomic surveillance with longitudinal serological monitoring to more precisely characterize the true epidemic dynamics of M. pneumoniae.

Conclusion

In summary, this study presents a comprehensive retrospective analysis the epidemiological trends of M. pneumoniae antibody positive rates in Chengdu spanning from 2017 to 2024, with particular emphasis on comparative assessments before, during, and after the COVID-19 outbreak. The findings provide valuable baseline data for local healthcare practitioners in enhancing early diagnosis and preventive strategies against M. pneumoniae infections. Given the distinct epidemiological patterns of M. pneumonia positive rates, region-specific and demographic-targeted prevention strategies should be implemented for children. Our analysis of the M. pneumoniae antibody positive disease spectrum reveals dynamic epidemiological shifts, particularly a marked increase in asthma and severe pneumonia cases in the post-pandemic period. These findings carry substantial clinical implications, underscoring the need to adapt current diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for M. pneumoniae antibody positive. Further research is warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms, including potential alterations in host immune responses or pathogen evolution. Furthermore, our study highlights the critical need for heightened vigilance during the post-holiday period and initial school reopening phases. We recommend implementing enhanced protective measures and prompt diagnostic testing upon symptom onset to facilitate early intervention and effective disease management.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

LY: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. HD: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation. HZ: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. ZD: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology. ML: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Sichuan Province Maternal and Child Medical Science and Technology Innovation Project (2024FX03).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, and the Chengdu Women's and Children's Central Hospital for providing technical supports for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Ai L. Liu B. Fang L. Zhou C. Gong F. (2024). Comparison of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children admitted with community acquired pneumonia before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective study at a tertiary hospital of southwest China. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.43, 1213–1220. 10.1007/s10096-024-04824-9

2

Baker R. E. Park S. W. Yang W. Vecchi G. A. Metcalf C. J. E. Grenfell B. T. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions on the future dynamics of endemic infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.117, 30547–30553. 10.1073/pnas.2013182117

3

Chen B. Gao L. Chu Q. Zhou T. Tong Y. Han N. et al . (2024). The epidemic characteristics of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection among children in Anhui, China, 2015–2023. Microbiol. Spectr.12:e0065124. 10.1128/spectrum.00651-24

4

Edouard S. Boughammoura H. Colson P. La Scola B. Fournier P.-E. Fenollar F. (2024). Large-scale outbreak of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection, Marseille, France, 2023–2024. Emerg. Infect. Dis.30, 1481–1484. 10.3201/eid3007.240315

5

Gu M. Liang Y.i. Gu Y. Li M. (2024). Correlation analysis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children with environmental and climatic factors in Meizhou region. Chin. J. Matern. Child Health Res.35, 33–36. 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5293.2024.10.06

6

Hu J. Ye Y. Chen X. Xiong L. Xie W. Liu P. (2023). Insight into the pathogenic mechanism of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Curr. Microbiol.80:14. 10.1007/s00284-022-03103-0

7

Jia X. Chen Y. Gao Y. Ren X. Du B. Zhao H. et al . (2024). Increased in vitro antimicrobial resistance of Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolates obtained from children in Beijing, China, in 2023. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.14:8087. 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1478087

8

Jiang M. Zhang H. Yao F. Lu Q. Sun Q. Liu Z. et al . (2024). Influence of non-pharmaceutical interventions on epidemiological characteristics of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children during and after the COVID-19 epidemic in Ningbo, China. Front. Microbiol.15:5710. 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1405710

9

Jiang T.-T. Sun L. Wang T.-Y. Qi H. Tang H. Wang Y.-C. et al . (2023). The clinical significance of macrolide resistance in pediatric Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.13:1181402. 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1181402

10

Jin X. Zheng J. (2022). Corrigendum on “IL-4-C-590T locus polymorphism and susceptibility to asthma in children: a meta-analysis”. J. Pediatr.98:111. 10.1016/j.jped.2021.11.001

11

Li X. Li T. Chen N. Kang P. Yang J. (2023). Changes of Mycoplasma pneumoniae prevalence in children before and after COVID-19 pandemic in Henan, China. J. Infect.86, 256–308. 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.12.030

12

Liu W. Chang J. Zhang N. Lai W. Li W. Shi W. et al . (2025). Family cleaning behaviors and air treatment equipment significantly affect associations of indoor damp indicators with childhood pneumonia among preschoolers. Int. J. Environ. Health Res.35, 1581–1595. 10.1080/09603123.2024.2398092

13

Liu X. Wang Y. Chen C. Liu K. (2021). Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection and risk of childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Microb. Pathog.155:104893. 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.104893

14

Mao J. Niu Z. Liu M. Li L. Zhang H. Li R. et al . (2025). Comparison of the epidemiological characteristics of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections among children during two epidemics in Wuhan from 2018 to 2024. BMC Pediatr.25:4359. 10.1186/s12887-025-05435-9

15

Miao Y. Li J. Huang L. Shi T. Jiang T. (2025). Mycoplasma pneumoniae detections in children with acute respiratory infection, 2010–2023: a large sample study in China. Ital. J. Pediatr.51:11. 10.1186/s13052-025-01846-7

16

Munro A. P. S. House T. (2024). Cycles of susceptibility: immunity debt explains altered infectious disease dynamics post-pandemic. Clin. Infect. Dis.11:ciae493. 10.1093/cid/ciae493

17

Nordholm A. C. Søborg B. Jokelainen P. Lauenborg Møller K. Flink Sørensen L. Grove Krause T. et al . (2024). Mycoplasma pneumoniae epidemic in Denmark, October to December, 2023. Eurosurveillance29:2300707. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2024.29.2.2300707

18

Onozuka D. Hashizume M. Hagihara A. (2009). Impact of weather factors on Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Thorax64, 507–511. 10.1136/thx.2008.111237

19

Qi J. Li H. Li H. Wang Z. Zhang S. Meng X. et al . (2025). Epidemiological changes of Mycoplasma pneumoniae among children before, during, and post the COVID-19 pandemic in Henan, China, from 2017 to 2024. Microbiol. Spectr.13:e0312124. 10.1128/spectrum.03121-24

20

Qiu W. Ding J. Zhang H. Huang S. Huang Z. Lin M. et al . (2024). Mycoplasma pneumoniae detections in children with lower respiratory infection before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a large sample study in China from 2019 to 2022. BMC Infect. Dis.24:4382. 10.1186/s12879-024-09438-2

21

Sampath V. Aguilera J. Prunicki M. Nadeau K. C. (2023). Mechanisms of climate change and related air pollution on the immune system leading to allergic disease and asthma. Semin. Immunol.67:101765. 10.1016/j.smim.2023.101765

22

Wagatsuma K. (2024). Effect of meteorological factors on the incidence of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in Japan: a time series analysis. Int. J. Biometeorol.68, 1903–1907. 10.1007/s00484-024-02712-7

23

Wang F. Cheng Q. Duo H. Wang J. Yang J. Jing S. et al . (2024). Childhood Mycoplasma pneumoniae epidemiology and manifestation in Northeast and Inner Mongolia, China. Microbiol. Spectr.12:e000972410.1128/spectrum.00097-24

24

Wang W. Luo X. Ren Z. Fu X. Chen Y. Wang W. et al . (2025). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic measures on hospitalizations and epidemiological patterns of twelve respiratory pathogens in children with acute respiratory infections in southern China. BMC Infect. Dis.25:103. 10.1186/s12879-025-10463-y

25

Wang X. Li M. Luo M. Luo Q. Kang L. Xie H. et al . (2022). Mycoplasma pneumoniae triggers pneumonia epidemic in autumn and winter in Beijing: a multicentre, population-based epidemiological study between 2015 and 2020. Emerg. Microbes Infect.11, 1508–1517. 10.1080/22221751.2022.2078228

26

Wu T.-H. Fang Y.-P. Liu F.-C. Pan H.-H. Yang Y.-Y. Song C.-S. et al . (2024). Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections among children before and during COVID-19 Pandemic, Taiwan, 2017–2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis.30, 1692–1696. 10.3201/eid3008.231596

27

Wu Y. Wang M. Lv X. Chen J. Song L. (2025). Characteristics of symptoms among outpatients following the discontinuation of the dynamic zero-COVID-19 policy in China: insights from an online nationwide cross-sectional survey in 2022. J. Thorac. Dis.17, 1593–1604. 10.21037/jtd-24-1244

28

Xiao S. Hou X. (2025). Changes in the Levels of the Serum Markers Serum Amyloid a and Immunoglobulin M in Children with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection complicated with asthma and their clinical significance. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr.35, 27–37. 10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2025056739

29

Xu Y. Yang C. Sun P. Zeng F. Wang Q. Wu J. et al . (2024). Epidemic features and megagenomic analysis of childhood Mycoplasma pneumoniae post COVID-19 pandemic: a 6-year study in southern China. Emerg. Microbes Infect.13:2353298. 10.1080/22221751.2024.2353298

30

Yamazaki T. Kenri T. (2016). Epidemiology of Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infections in Japan and Therapeutic Strategies for Macrolide-Resistant M. pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol.7:0693. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00693

31

Yan C. Xue G.-H. Zhao H.-Q. Feng Y.-L. Cui J.-H. Yuan J. (2024). Current status of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in China. World J. Pediatr.20, 1–4. 10.1007/s12519-023-00783-x

32

Yang S. Lu S. Guo Y. Luan W. Liu J. Wang L. (2024). A comparative study of general and severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children. BMC Infect. Dis.24:449. 10.1186/s12879-024-09340-x

33

Zhang J. Wu R. Mo L. Ding J. Huang K. (2025). Trends in Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in pediatric patient preceding, during, and following the COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive longitudinal analysis. Microbiol. Spectr.13:e0100124. 10.1128/spectrum.01001-24

34

Zhang Y. Huang Y. Ai T. Luo J. Liu H. (2021). Effect of COVID-19 on childhood Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in Chengdu, China. BMC Pediatr.21:202. 10.1186/s12887-021-02679-z

35

Zhu X. Liu P. Yu H. Wang L. Zhong H. Xu M. et al . (2024). An outbreak of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children after the COVID-19 pandemic, Shanghai, China, 2023. Front. Microbiol.15:7702. 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1427702

Summary

Keywords

respiratory tract infection (RTI), children, Mycoplasma pneumoniae (M. pneumoniae), epidemiology, the COVID-19 pandemic

Citation

Yan L, Dong H, Zhang H, Du Z, Lai M and Zhang L (2025) Positive rates of Mycoplasma pneumoniae antibodies in children before, during and after COVID-19 outbreak: an observational study in Chengdu, China from 2017 to 2024. Front. Microbiol. 16:1649615. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1649615

Received

18 June 2025

Accepted

27 August 2025

Published

16 September 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Arryn Craney, Petrified Bugs LLC, United States

Reviewed by

Mahinder Paul, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, United States

Zheng Liu, Tianjin University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Yan, Dong, Zhang, Du, Lai and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lei Zhang 534167313@qq.comMeimei Lai 8313974@qq.com

†These authors share second authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.