- School of Biological Science, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, United Kingdom

Invasive fungal infections caused by pathogenic yeasts are an escalating global health crisis that demands urgent attention within a One Health framework. This review critically examines mounting evidence that widespread agricultural azole fungicide use is a key driver accelerating antifungal resistance in pathogenic yeast. We dissect the shared molecular targets and resistance pathways that underpin dangerous cross-resistance between environmental fungicides and clinical azoles. Traditionally viewed as human commensals, we provide a comprehensive account of the evidenced environmental reservoirs of yeast pathogens, including agricultural soils, wastewater, and the food chain. Ecosystems burdened by persistent azole contamination that create hotspots for resistance evolution and amplification. With antifungal treatment options rapidly diminishing and resistant infections causing rising morbidity and mortality worldwide, we identify vulnerabilities in our shared environment and consider integrated surveillance, stewardship, and environmental interventions to help preserve the efficacy of life-saving antifungals and mitigate the growing threat of fungal disease.

1 Current uses and limitations of antifungal drugs

Over the past several years, opportunistic fungal pathogens have become a significant threat to human health. The most prevalent invasive fungal infections are the result of Candida species (70%), Aspergillus species (10%), and Cryptococcus species (20%) (Fang et al., 2023). It is estimated that invasive fungal infections (IFIs) result in 3.8 million deaths globally each year (Denning, 2024), with more than 90% of deaths associated with Candida and Aspergillus species (Shafiei et al., 2020). The severity of the fungal disease is dependent on the host immune system (Shah et al., 2024), with immunocompromised individuals significantly at risk.

Agricultural environments are also highly susceptible to fungal infections, posing a serious global food security risk. It is estimated that crop fungal infections lead to 10–23% loss pre-harvest and an additional 10–20% loss post-harvest despite fungicide treatment (Steinberg and Gurr, 2020), equating to the amount of food which could sufficiently feed ~4,000 million people for a year (Olita et al., 2024). Some of the most prevalent fungal phytopathogens are associated with Fusarium and Zymoseptoria species, with Fusarium resulting in a global crop yield loss of ~80% (Amar, 2021), and Z. tritici causing up to 50% yield losses of wheat annually (Stukenbrock and Gurr, 2023).

Our arsenal of drugs to combat fungal disease is very limited. There are four primary antifungal drug classes used to treat IFIs in the clinic: azoles, polyenes, pyrimidine analogs (5-FC), and echinocandins (Souza et al., 2025). In agricultural settings, the situation is better, with fungicide classes being divided according to 52 different modes of action (Lamberth, 2022). The five major classes of fungicides include benzimidazoles, demethylation inhibitors (DMIs), quinone outside inhibitors (Qols), quinone inside inhibitors (Qils) and succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors (SDHIs) (Corkley et al., 2022).

1.1 Mechanism of action of ergosterol biosynthetic inhibitors

Azole antifungals represent one of the most widely used drug classes in clinical medicine, targeting the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway (Monk et al., 2020). Ergosterol is the prevalent sterol in fungal cell membranes, with crucial functions in the regulation of membrane structure, fluidity and permeability (reviewed in Rodrigues, 2018). Azoles alter membrane function by inhibiting the cytochrome P450-dependent enzyme, 14-⍺-demethylase, encoded by ERG11 in yeast and CYP51 in moulds (Cowen et al., 2014). Azole antifungals are mostly fungistatic towards yeasts, arresting their growth as opposed to killing them, whereas they can be fungicidal for some moulds (Geissel et al., 2018). However, under certain conditions azoles are fungicidal against yeast. For example, in C. albicans, itraconazole was shown to trigger apoptosis (Lee and Lee, 2018).

Despite their fungistatic nature, azoles remain the first line of therapy in clinical settings due to their low incidence of toxicity compared to other drug classes (Osa et al., 2020). In agricultural settings, the comparable fungicide drug class are demethylase inhibitors, or DMIs (Stenzel and Vors, 2019), as they are largely comprised of triazole and imidazole compounds (FRAC, 2025) and also target the enzyme 14-⍺-demethylase, encoded by CYP51 in phytopathogens (Mair et al., 2020). DMIs are the most widely used fungicide in agriculture as they exhibit a broad range of activity with high efficacy levels (Wang et al., 2024). For this review we will use the broad term azole to refer to both clinical antifungals and agro-chemical fungicides that target ergosterol biosynthesis through CYP51/ERG11 inhibition.

1.2 Structural conservation of azole targets - implications for cross-reactivity

As depicted in Figure 1, both clinical and agricultural azoles share similar structures (Monk et al., 2020). A key structural feature of all azoles is a nitrogen ring with two adjacent CH or N ring members which enables non-competitive binding to the iron-heme active site of the ERG11/CYP51 enzyme (Yoshida and Aoyama, 1987; Podust et al., 2001). Extensive studies on the molecular interactions reveal that hydrophobic forces between the drug and the non-polar residues of the enzyme’s active site primarily drive this binding (Reviewed in Ruge et al., 2005). Azoles can be classified as short-tailed or long-tailed, based on both the length of the compound but also the extent to which they bind to their target. Long-tailed azoles forming additional hydrophobic interactions along the active site, leading to increased binding affinities and drug potency (Sagatova et al., 2016; Warrilow et al., 2010). This distinction is clear for clinical azoles, however most DMIs are considered short-tailed (Gisi, 2022). Although not explicitly classed as long-tailed azoles, some DMIs (difenoconazole and prochloraz) can still demonstrate long-tailed drug potency (Zhang et al., 2021; Strickland et al., 2022).

Figure 1. Chemical structures of short-tailed (fluconazole, voriconazole, propiconazole, and tebuconazole), and long-tailed (itraconazole, posaconazole, difenoconazole, and prochloraz) ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors. The common structure is highlighted by a yellow box, featuring a nitrogen-containing ring with two adjacent CH or N ring members. *imidazole-based DMIs, †fungicides which are classified as long-tailed based on potency, not length.

Despite major differences in their targeted fungus, both clinical and agricultural azoles can cross-react due to the high structural conservation of cytochrome P450 enzymes in biology (Nelson, 2018; Srejber et al., 2018; Lepesheva and Waterman, 2011). Indeed, 42% of amino acid sites are invariant among fungal P450 homologues, many of which occupy structurally critical positions (Lepesheva et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2019). Furthermore, residues involved in the azole-enzyme interaction are evolutionarily conserved between ERG11 and CYP51 homologues. For example, an active site tyrosine that forms critical H-bonds with azoles are conserved between Candida albicans ERG11 (Y132) and the CYP51 homologues of the phytopathogens, Z. tritici (Y137), Penicillium digitatum (Y126) and Blumeria graminis (Y136). Additionally, there is a core set of invariant non-polar residues on the azole binding surface of many ERG11/CYP51 homologues (Sagatova et al., 2016; Parker et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2020; Li et al., 2011). Given such structurally similarities, it is unsurprising that both clinical azoles and agricultural fungicides bind to and inhibit C. albicans Erg11p to similar extents, with comparable Kd and IC50 values, respectively, (Parker et al., 2014). Theoretically, this means that DMI exposure can exert strong selective pressure on C. albicans, and potentially other pathogenic yeasts. Encouraging them to adapt to azole. This raises significant concerns, as widespread agricultural use of DMIs may contribute to azole resistance in environmental pathogenic yeast populations, potentially compromising clinical treatment options for candidiasis (Gomez Londono and Brewer, 2023).

This review focuses on the impact of DMIs on antifungal drug resistance in pathogenic yeast. Specifically, we are only considering yeast from the Ascomycota phylum, with a focus on Candida albicans, Candida parapsilosis, Candida tropicalis, and Candida associated yeasts Pichia kudriavzevii (Candida krusei), Candidozyma auris (Candida auris), Meyerozyma guilliermondii (Candida guillermondii), and Nakaseomyces glabratus (Candida glabrata), these will be referred to collectively as pathogenic yeasts. We will use ‘cross-resistance’ to mean dual resistance towards azole antifungals and fungicides based on a single mechanism, and ‘multi-drug resistance’ as the ability of a single species to be resistant to multiple classes of antifungals or fungicides (Figure 2). Our aim is to address the following questions related to azole cross-resistance in Candida species.

1. Do Candida species exhibit shared resistance mechanisms to clinical and agricultural azoles that enable cross-resistance?

2. Are environmental reservoirs of Candida spp. exposed to agricultural DMIs?

3. Are there plausible transmission routes through which humans are exposed to DMI-adapted Candida strains?

Figure 2. Resistance profiles in fungal pathogens. The image illustrates the potential resistance profiles of pathogenic yeast to antifungal drugs.

By addressing these questions, based on our current knowledge, we aim to critically evaluate the threat posed by agricultural DMI use on clinical azole resistance and the epidemiology of fungal infections.

2 Mechanisms of resistance to azoles in pathogenic yeast

Acquired fungal drug resistance arises from the selection of genetic adaptive mutations by drug exposure (Czajka et al., 2023). In the context of ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors, acquired resistance in pathogenic yeast species typically evolves via either target-site (direct) or non-target-site (indirect) mechanisms. Most clinically relevant fungal species exhibit both routes, although some show a bias toward one, potentially due to a factors such as species-specific mutational bias (reviewed in Osset-Trénor et al., 2023). Direct resistance mechanisms to azoles commonly involve point mutations within ERG11/CYP51, the genes encoding the target enzyme, that reduce drug binding affinity. Overexpression of ERG11 is another direct mechanism, effectively increasing the amount of target enzyme and necessitating higher drug concentrations to achieve inhibition (Zavrel et al., 2017; Handelman et al., 2021). Indirect resistance mechanisms primarily entail enhanced drug efflux, mediated by upregulated expression of transmembrane transporters. These often result from gain-of-function mutations in either the promoter regions of efflux pump genes or in transcription factors that regulate their expression (Hokken et al., 2019). While these mechanisms represent the most well-characterized routes to azole resistance, they do not encompass the full complexity of resistance evolution in pathogenic yeast. For example, other studies have demonstrated that changes in ploidy (Ahmad et al., 2014), and the roles of DNA mismatch repair pathways (Legrand et al., 2007) can also alter azole susceptibility. Several comprehensive reviews have catalogued the diversity of mutations and regulatory changes contributing to this phenotype (Bhattacharya et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021; Chaabane et al., 2019; Fisher et al., 2022).

2.1 Experimentally induced azole cross resistance in pathogenic yeast

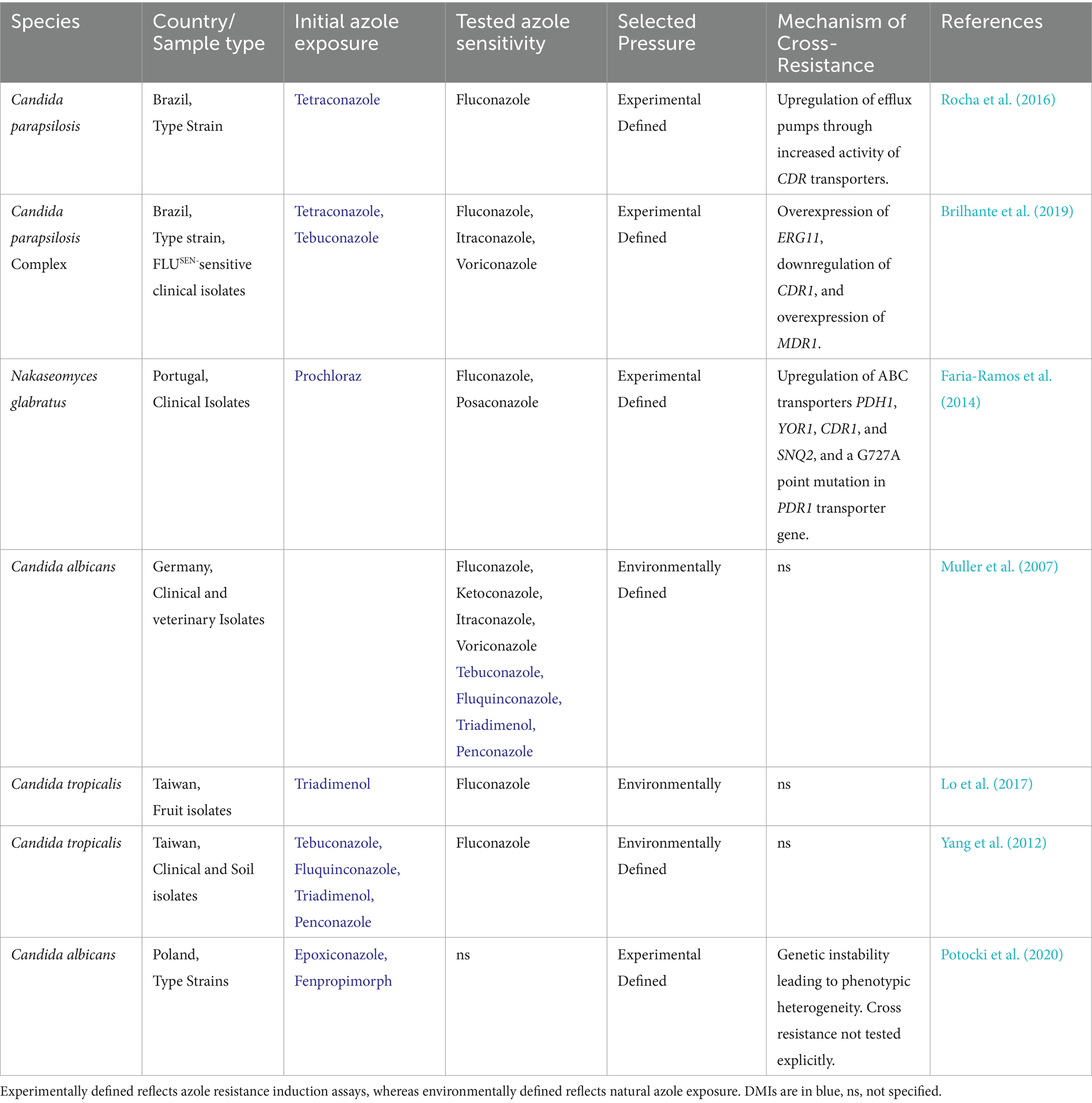

Despite the pressing need to understand molecular cross-resistance mechanisms in yeast pathogens, evidence remains limited. Most studies have employed in vitro induction assays: Yeast isolates are first exposed to agricultural DMIs, then tested for azole susceptibility. Faria-Ramos et al. (2014) demonstrated that a 90-day exposure to the DMI prochloraz led to stable cross-resistance to fluconazole and posaconazole—but only in Nakaseomyces. glabratus isolates (Faria-Ramos et al., 2014). Similarly, Rocha et al. (2016) demonstrated that resistance to fluconazole, itraconazole and voriconazole evolves in Candida parapsilosis following 49-day exposure to the DMI tetraconazole (Rocha et al., 2016). Such findings were expanded by the same group in 2019 showing that only 15-day exposure to the DMIs tebuconazole and tetraconazole was sufficient to cause fluconazole resistance in C. orthopsilosis, C. metapsilopsis and C. parapsilosis (Brilhante et al., 2019). Together, these findings robustly support that exposure to DMIs can select for mutations that confer resistance to clinical azoles in multiple Candida species under experimental conditions.

Interestingly, exposure to DMIs does not universally result in cross-resistance in yeast. For instance, although prochloraz exposure induced resistance to DMIs in C. albicans and C. parapsilosis, no corresponding decrease in susceptibility to fluconazole or posaconazole was observed, indicating an absence of clinically relevant cross resistance in these strains (Faria-Ramos et al., 2014). Similarly, prolonged growth in the presence of tebuconazole or tetraconazole did not confer resistance to itraconazole or voriconazole in C. parapsilosis or C. orthopsilosis (Brilhante et al., 2019). These findings suggest that the development of cross resistance following DMI exposure is not uniform across yeast species or azole compounds and may be contingent upon species/strain-specific responses or compound-specific effects. The difference in chemical structure of azole compounds may also impact cross-resistance patterns. For example, mutations which select for resistance towards short-tailed triazoles will not confer resistance towards long-tailed azoles (Toepfer et al., 2023; Rallos and Baudoin, 2016). It is also worth noting that such in vitro assays are inherently limited by the stochastic nature of mutational events that drive resistance evolution (Hawkins et al., 2016), underscoring the need for broader and more systematic investigations to clarify the conditions under which cross resistance may emerge.

2.2 Molecular basis of azole cross-resistance in yeast pathogens

Gene expression analyses of experimentally derived cross resistant yeast strains have begun to elucidate the molecular basis of this phenotype. In Nakaseomyces glabratus, exposure to prochloraz induces overexpression of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters ngPDH1 and ngCDR1, as well as the transcription factor ngPDR1, which regulates their expression (Faria-Ramos et al., 2014). These mechanisms mirror those commonly associated with resistance to clinical azoles. Notably, this study also identified overexpression of ngYOR1, encoding an ABC transporter not previously linked to azole resistance, suggesting the existence of a potentially unique cross resistance pathway in N. glabratus (Faria-Ramos et al., 2014). In Candida parapsilosis, however, the molecular responses to DMI exposure appear more variable. One study reported increased expression and activity of the efflux transporter cpCDR1 following tetraconazole exposure (Rocha et al., 2016). Conversely, a separate investigation found that cpCDR1 was downregulated in the C. parapsilosis species complex after exposure to tebuconazole and tetraconazole, while cpERG11 expression was upregulated (Brilhante et al., 2019). Despite these differences, both studies implicate efflux transporters in the cross resistance response of C. parapsilosis and C. metapsilosis, suggesting a potential bias toward indirect resistance mechanisms in these closely related species (Rocha et al., 2016; Brilhante et al., 2019). Collectively, these findings support the view that DMI exposure can dysregulate indirect resistance pathways, primarily involving efflux transporters and their regulators (summarized in Table 1).

Exposure to DMIs also elicits broader physiological and genomic responses in yeast species. Potocki et al. (2020) reported that treatment with the fungicide epoxiconazole led to increased ROS, altered fatty acid and phospholipid composition, reduced biofilm formation, and heightened DNA damage across four species—C. albicans, N. glabratus, C. tropicalis, and C. pulcherrima—resulting in genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous populations (Potocki et al., 2020). Notably, diminished biofilm formation was also observed in tebuconazole-treated C. parapsilosis (Rocha et al., 2016). In addition, Hu et al. (2025) demonstrated that C. tropicalis exposed to tebuconazole resulted in cross-resistance to both fluconazole and voriconazole. Furthermore, these resistance strains displayed genomic instability manifesting as ploidy variation—including haploidization, and a reduction in growth rate (Hu et al., 2025). Such genomic plasticity underscores a potential mechanism by which environmental DMIs contribute to the evolution of clinically relevant azole resistance (Hu et al., 2025).

3 Environmental reservoirs of yeast species

For fungicide-exposed human pathogens to drive clinical resistance, two conditions must be met. (1) Human fungal pathogens must actively grow in agricultural environments where they are exposed to fungicides, and (2) Humans must routinely come into contact with these environmentally derived strains. Both conditions are met in the case of Aspergillus species (Rhodes et al., 2022). These opportunistic pathogens are considered ubiquitous in the environment and have been detected in soil, organic matter, air, and water (Paulussen et al., 2017). Aspergillus spp. produce airborne spores which are easily inhaled by humans. Indeed, it is estimated that humans inhale 500–100,000 pathogenic spores daily (Salazar-Hamm et al., 2022), and not surprisingly, inhalation is the primary route of infection for invasive aspergillosis (Park et al., 2019). This means that Aspergillus spores from environments regularly exposed to DMIs, offer a direct pathway for potentially resistant fungal pathogens to move from the environment to humans.

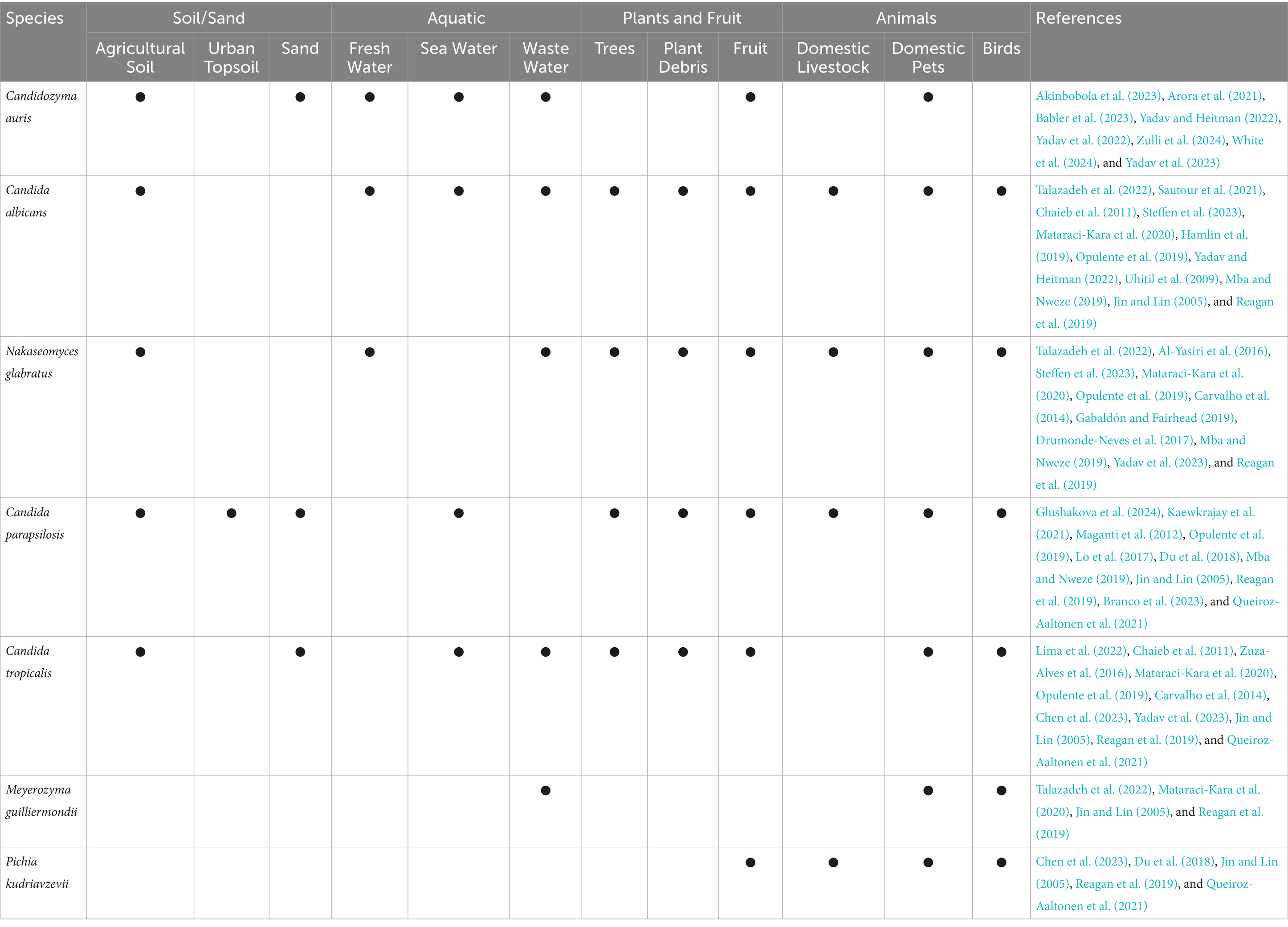

For opportunistic yeast species the role of fungicide exposure in driving cross-resistance is less obvious. Firstly yeast species are not widespread in the environment (Kumamoto et al., 2020), and are not classed as significant environmental pathogen (Ratnadass and Martin, 2022) suggesting limited exposure to DMIs. Opportunistic yeast pathogens, such as Candida spp. are primarily commensal organisms existing within the natural microflora of the gastrointestinal tract, skin, and oral and vaginal mucosa of humans (Boonsilp et al., 2021; Limon et al., 2017). Similarly, in animals, opportunistic yeasts can be part of their microbiome. Candida tropicalis has been isolated from the microbiome of healthy ruminants (goats, sheep), horses, shrimp, sirenians (manatees), and dwarf sperm whales (Cordeiro Rde et al., 2015). Additionally C. albicans and non-albicans strains considered commensals have been isolated from avian species; Galliformes, Anseriformes, Columbiformes, and Passeriformes (Salazar-Hamm et al., 2025; Talazadeh et al., 2022; Talazadeh et al., 2023), psittacine, and rheas (Cordeiro Rde et al., 2015).

This commensal lifestyle however, does mean that many opportunistic yeasts can be environmental contaminants, due to shedding from their host and animal excretions (Carpouron et al., 2022; Branda Dos Reis et al., 2024; Rosario Medina et al., 2017). Although this fungal contamination does not indicate a true environmental niche, the main point is that regardless of their origin, clinically relevant yeast species have been isolated from non-clinical environmental reservoirs such as soil, water, fruit, trees, and plants (Akinbobola et al., 2023), as summarized in Table 2. This suggests that environmental exposure to DMIs, while likely a lot lower than for Aspergillus, cannot be ruled out entirely.

3.1 Yeast species in soil

Soil may serve as a potential environmental reservoir for opportunistic yeast species. Research shows that yeast favour agricultural and grassland soils, likely due to their copiotrophic lifestyle – thriving on simple sugars and tolerating low oxygen conditions (Yurkov, 2018). Many yeasts also contribute to soil health by participating in nutrient cycling and transformation, organic matter decomposition and soil fertilisation (Samarasinghe et al., 2021). For instance, Candida tropicalis HY (CtHY), isolated from rice rhizosphere, produces plant growth regulators and is commonly used as biofertilizer (Amprayn et al., 2012).

Evidence suggests soil-dwelling yeasts are globally distributed (Lima et al., 2022; Glushakova et al., 2024). Candida tropicalis has been isolated from agricultural fields, forest and sludge soil across Taiwan, China, Brazil, USA, UK and Ireland (Lima et al., 2022) and C. parapsilosis from urban topsoil in Moscow (Glushakova et al., 2024). While N. glabratus is often recovered from soil, its presence is attributed to contamination from yellow-legged gull faeces (Al-Yasiri et al., 2016). Regardless of how these yeast species reach soils, it clearly survives in this environment, C. albicans for example was shown to replicate in French soils for up to 30-days (Sautour et al., 2021).

3.2 Yeast species in aquatic environments

An increasing number of studies associate yeast pathogens with aquatic environments. The most notable example is Candidozyma auris (formally Candida auris) a recently identified species known for its thermotolerance and halotolerance. These traits have led researchers to hypothesize that, C. auris originated in marine or freshwater ecosystems (Akinbobola et al., 2023; Sharma and Chakrabarti, 2020; Casadevall et al., 2019). Supporting this, Arora et al. (2021), isolated C. auris from sandy beaches and salt marshes in India’s coastal wetlands, while Escandon (2022) reported C. auris presence in estuaries in Colombia. Additionally, C. auris shares a close relationship with Candida haemulonii, a species previously isolated from seawater off the coast of Portugal and the skin of dolphins (Garcia-Bustos et al., 2024). This phylogenetic link further suggests that C. auris originated in aquatic ecosystems. Alarmingly, these environmental C. auris strains often display multidrug resistance to clinical azoles, underscoring the threat they pose to human health (Arora et al., 2021). Furthermore, Akinbobola et al. (2024) observed that C. auris can colonise plastic pollutants in marine environments for up to 30 days, without compromising pathogenicity (Akinbobola et al., 2024).

Other opportunistic yeasts, including C. albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis also exhibit halo-tolerance, suggesting an ability to survive in marine niches (Chaieb et al., 2011; Zuza-Alves et al., 2017; Kaewkrajay et al., 2021). Accordingly, C. albicans persists in Tunisian seawater for up to 200 days (Chaieb et al., 2011), and C. tropicalis has been isolated from sand and coastal waters of Miami and Brazil (Zuza-Alves et al., 2016; Vogel et al., 2007). A startling 2024 study has uncovered a rising threat of fungal infections among cetacean marine species, including cases involving drug-resistant Candida yeast (Garcia-Bustos et al., 2024). Furthermore, C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis are associated with marine sponges in the South China Sea, isolated from seawater, sea sediments, marine ecosystems, and beach sand (Kaewkrajay et al., 2021). Worryingly, fluconazole resistant N. glabratus has been found in river water, alongside C. albicans, and both are now classified as river water contaminants in South Africa (Steffen et al., 2023).

Wastewater and sewage effluent is another significant aquatic reservoir for human fungal pathogens (Assress et al., 2019). It has been suggested that the phenotypic plasticity exhibited by many yeast species such as biofilm formation and their ability to adapt rapidly to changing environments, may explain their persistence in wastewater (Buratti et al., 2022; Marta and Alina, 2017). Given their role as gut commensals, it is unsurprising that 0.1–1% of human faecal matter is fungal in origin (Qin et al., 2010), including major opportunistic yeast pathogens (Gurleen and Savio, 2016). Indeed, one study investigating Candida species present in wastewater from Brazil identified six Candida species within sewage samples (Correa-Moreira et al., 2024). Similarly, C. albicans, N. glabratus, C. tropicalis, Meyerozyma guilliermondii, and C. auris are routinely isolated from both hospital and community wastewater sources (Mataraci-Kara et al., 2020; Babler et al., 2023). Indeed C. auris has been found in 190 general wastewater treatment plants across 41 US states (Zulli et al., 2024).

3.3 Yeast species and plants

In recent years growing evidence has highlighted the association between opportunistic yeast and plants. While much of this attention has focused on the detection of human pathogens in the food chain, especially fruit, reports also document the incidence of yeast directly on trees and in plant litter (Bensasson et al., 2019; Hamlin et al., 2019; Maganti et al., 2012; Opulente et al., 2019). Research from North America has reported various species including C. albicans (Hamlin et al., 2019), C. parapsilosis (Maganti et al., 2012), C. tropicalis, and N. glabratus (Carvalho et al., 2014) on trees such as oak, pine, maple, ash, cedar and birch. In some cases, these associations appear species-specific, with one study noting that C. parapsilosis exclusively colonized pine trees (Maganti et al., 2012). Nakaseomyces glabratus and C. tropicalis also associate with cedar and birch trees (Carvalho et al., 2014). All four species have also been isolated from decaying plant matter, including duff and leaf litter (Opulente et al., 2019).

Even more concerning is the repeated detection of yeast pathogens on raw fruit, which can serve as a direct route of human exposure. Drug-resistant strains such as fluconazole-resistant C. auris have been isolated from apples in India (Yadav and Heitman, 2022; Yadav et al., 2022). In Taiwan, C. tropicalis and Pichia kudriavzevii were found on a range of fruits including pears, mangoes, melons, and guavas (Chen et al., 2023). Other studies have reported C. tropicalis on bananas and waxed apples, P. kudriavzevii on tomatoes, and C. parapsilosis on pears (Lo et al., 2017). Though less common, N. glabratus has been recovered from crushed grapes and during wine fermentation (Gabaldón and Fairhead, 2019; Drumonde-Neves et al., 2017). While C. albicans has been isolated from a freshly harvested apple in India (Yadav and Heitman, 2022), and from fresh orange juice in Croatia (Uhitil et al., 2009).

While some argue that these findings may result from human handling, since many yeast species are part of the skin microbiome (Yadav and Heitman, 2022). This explanation does not lessen the risk. Importantly, fruit can serve as a nutritional source for yeasts permitting their growth and persistence, even those transferred from humans. Moreover, many fruits especially non-organic ones, are treated with post-harvest fungicides to prevent spoilage (Yadav et al., 2022). This creates an environment where opportunistic yeast pathogens, regardless of how it arrived on the surface, are exposed to drugs that can select for resistance, possibly driving cross resistance (Crump and Edlinds, 2004).

These observations challenge the conventional view of yeast species as obligate human commensals and underscore the necessity of re-evaluating their ecological breadth (Sautour et al., 2021; Sharma and Chakrabarti, 2020). Although methodological limitations may obscure the true prevalence of Candida and other yeast species in environmental samples, the diversity of niches yielding positive detections is striking and emphasizes the importance of further research into their environmental biology. It remains unclear whether these fungi represent long-term components of these ecosystems or are recent introductions via anthropogenic or zoonotic shedding. Both scenarios are likely contributory. Notably, recent genomic evidence suggests that environmental C. albicans isolates recovered from oak trees exhibit significant genetic divergence from clinical strains, implying independent evolutionary trajectories (Salazar-Hamm et al., 2025). Despite the frequent recovery of pathogenic yeast species from non-clinical reservoirs, the implications of their environmental persistence for the epidemiology of candidiasis remain poorly understood (Czajka et al., 2023).

4 A one health perspective on antifungal resistance

The One Health framework emphasizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health, recognizing that the health of each domain is inextricably linked (Mackenzie and Jeggo, 2019). In the context of antifungal resistance in opportunistic yeast, a One Health approach provides a critical lens through which to examine the relationship between the agricultural use of DMI and the declining efficacy of clinical azoles in treating candidiasis. Here, we define this perspective as encompassing the environmental evolution and potential transmission of azole cross-resistant yeast pathogens to humans.

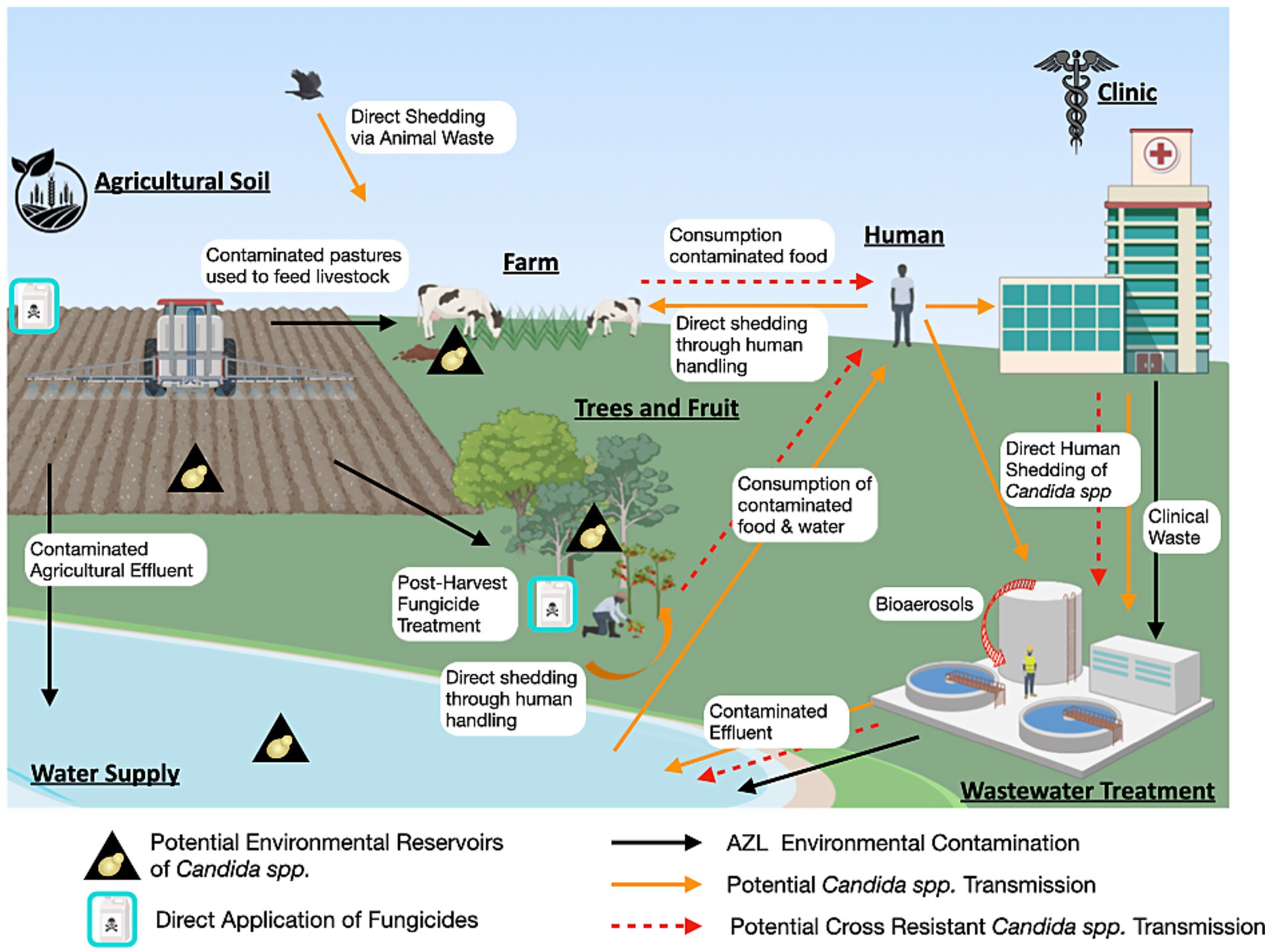

If yeast pathogens are capable of actively growing in non-host environments, and DMI exposure can select for mutations that confer cross-resistance, then the emergence of environmentally derived resistant strains in human populations becomes a plausible scenario. The detection of azole-resistant Candida isolates in treatment-naïve patients further supports the notion that environmental acquisition of resistance may be more common than previously appreciated (Chen et al., 2019; Chong et al., 2012; Daneshnia et al., 2023; Alcoceba et al., 2022). Although another explanation for this could be nosocomial transmission of resistant isolates. Evidence has shown that clonal fluconazole-resistant strains can spread between patients and can also be transmitted from contaminated surfaces within hospitals (Hwang et al., 2024; De Carolis et al., 2024). This raises a key question: through what pathways do fungicide-exposed yeast strains transition from the environment to human hosts? The current understanding of the environmental-to-human interface in the emergence of azole cross-resistant opportunistic yeast is outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3. One Health perspective of Candida azole resistance. This diagram illustrates the non-clinical reservoirs of Candida species, the environmental contamination of clinical azoles and DMIs, as well as the potential routes of transmission of cross-resistant strains (Figure generated using Biorender.com).

4.1 Food-chain associated transmission of cross-resistant yeast pathogens

One prominent route for the transmission of azole-resistant yeast pathogens to humans is through the food chain. This includes consumption of fruits contaminated with fungicide-resistant yeasts, as has been previously described. Another critical pathway involves the transmission of resistant opportunistic yeast through the consumption of animal-derived food products. Candida spp. and other yeast pathogens are well-recognized members of the natural gastrointestinal microbiota of animals, similar to humans (Castelo-Branco et al., 2020; Deng et al., 2025). What is particularly striking is the increasing incidence of azole-resistant Candida isolates recovered from livestock, despite systemic antifungal therapy rarely being applied in veterinary contexts (Lima et al., 2022; Castelo-Branco et al., 2022). This paradoxical emergence of azole resistance in animal associated yeast species is likely driven by indirect environmental pressures. Constant exposure to agricultural fungicides, especially DMIs used extensively on crops and pastures, may select for resistant fungal populations within the animal microbiota or the environment they inhabit (Castelo-Branco et al., 2022; Fisher et al., 2018). Additionally, direct transmission from fungicide-exposed environmental yeast populations to animals may occur.

Notably, yeast species such as C. albicans, P. kudriavzevii, N. glabratus and C. parapsilosis have been implicated in mycotic mastitis in dairy cattle, causing mammary gland infections that reduce milk yield (Devanathan et al., 2024). Resistance profiles of these isolates are concerning: Du et al. (2018) demonstrated that P. kudriavzevii isolates from mastitis milk samples were resistant to fluconazole, ketoconazole, and itraconazole, despite the absence of prior antifungal treatment in the affected cows (Du et al., 2018). This suggests environmental stressors, likely prolonged exposure to agricultural DMIs driving azole resistance independently of clinical antifungal use.

Further evidence of environmentally mediated azole resistance is reported in other domestic livestock including pigs, goats, sheep, horses and chickens (Lima et al., 2022; Mba and Nweze, 2019). Mba and Nweze (2019) isolated yeast species (C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, and N. glabratus) from blood and urine samples of apparently healthy animals in an abattoir setting. Alarmingly, 12 out of 14 isolates from blood showed resistance to multiple azoles including fluconazole, voriconazole, ketoconazole, and itraconazole. These findings raise significant public health concerns because these azole-resistant strains were recovered from animals with no history of infection or antifungal treatment and were considered fit for human consumption (Mba and Nweze, 2019). The circulation of these resistant strains may be further amplified by dissemination via animal waste, environmental contamination, and direct contact between animals and humans, potentially facilitating the spread of resistant fungi along the food chain and environment (Fisher et al., 2022; Verweij et al., 2009).

4.2 Environmental modes of transmission of cross-resistant yeast pathogens

The presence of pathogenic yeast in wastewater environments may contribute significantly to the emergence and evolution of azole cross-resistance. This is largely due to the co-occurrence of clinical and agricultural azole compounds in wastewater, which exerts selective pressure on fungal populations and facilitates the enrichment of resistant strains (Assress et al., 2021). Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are largely ineffective at removing many of these compounds; for example, concentrations of fluconazole, propiconazole, and tebuconazole remain largely unaltered after treatment and are subsequently discharged into the aquatic environment (Kahle et al., 2008). The persistence of fungal pathogens in treated effluent has been documented in various regions, including a South African WWTP, underscoring the limitations of current treatment protocols in eliminating fungal pathogens (Assress et al., 2019). Furthermore, during wastewater processing, aerosolization of fungal pathogens, including yeasts, can lead to their dissemination as bioaerosols and dust particulates, posing potential inhalational risks for humans and contributing to the spread of cross-resistant strains (Szulc et al., 2021; Tian et al., 2020).

Agricultural effluent is another major route through which DMIs enter natural water bodies, where they persist and exert non-specific toxic effects (Zhu et al., 2023; Wightwick et al., 2012). Fungicides can enter aquatic systems through surface runoff, and drainage primarily from heavy agricultural areas, or from wastewater treatment discharge (Zubrod et al., 2019). This environmental contamination not only disrupts aquatic ecosystems (Zhu et al., 2023), but also imposes selective pressure on environmental fungal populations, potentially driving the development of azole resistance. River systems polluted with both fungicides and yeast pathogens may therefore serve as important reservoirs and evolutionary hotspots for the emergence of cross-resistant strains.

Soil is also a critical environmental niche for opportunistic yeast, especially given the high persistence and low degradation rates of agricultural fungicides, which accumulate over time and maintain selective pressure (Castelo-Branco et al., 2022; Ockleford et al., 2018). In a 2012 study by Yang et al., C. tropicalis strains isolated from agricultural soils in Taiwan exhibited reduced susceptibility to fluconazole in 17 out of 18 samples, and several of these strains were also resistant to the DMIs penconazole and tebuconazole (Mackenzie and Jeggo, 2019). Notably, genotyping these strains revealed close genetic relationships between soil C. tropicalis isolates and those from clinical and food sources, such as fruit (Yang et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2019) suggesting potential for environmental-to-human transmission. Similarly, a study from Brazil isolated C. albicans, C. parapsilosis sensu stricto, C. tropicalis, and C. metapsilosis from fungicide-treated agricultural soils. All 24 isolates showed resistance to the DMIs tetraconazole and tebuconazole, and several C. albicans strains also demonstrated elevated resistance to fluconazole and voriconazole (Sidrim et al., 2021). These findings are concerning within the One Health framework, as they highlight the potential for environmental reservoirs, particularly soil, to harbour medically relevant yeast pathogens with reduced azole susceptibility (Fisher et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2012).

Importantly, these data implicate environmentally derived yeast pathogens as capable of direct transmission to humans via inhalation, ingestion, or contact with open wounds, increasing the risk of human infection with environmentally acquired cross resistance isolates.

4.3 Cross-resistant yeast species in the clinic

A 2007 study by Muller et al., investigated azole cross-resistance in human and environmentally sourced yeast species. Specifically, C. albicans isolates from HIV-positive patients (+/− treatment) were compared to C. albicans from animals, N. glabratus from beets, P. kudriavzevii from grapes, draff, and grass silage, C. rugosa from animal feed, C. lambica, C. norvegensis, C. stellata from grapes (Muller et al., 2007). As assumed, environmental isolates showed less sensitivity to DMIs, (fluquinazole, penconazole, tebuconazole, and triadimenol). Whereas human isolates were more resistant towards clinical azoles (fluconazole, itraconazole and voriconazole). However, cross resistance was reported for 16/54 environmental isolates (~30%) including all C. stellata and C. lambica isolates (n = 10). Within the clinical group, nearly all isolates from fluconazole-treated patients were resistant to both clinical and agricultural azoles, indicating cross-resistance in the clinic. By contrast, C. albicans from animals remained uniformly drug-sensitive (Muller et al., 2007). While only one study has formally reported cross-resistant yeast strains in clinical settings, this likely stems from limited surveillance of clinical isolates. Notably, we have identified multiple CR strains from regional hospitals in Northern Ireland (unpublished data).

4.4 Emerging drivers of cross-resistance

Human disruption of the environment is increasingly linked to the emergence of new fungal pathogens. Candida palmioleophila, first isolated from soil in 1988, has since been identified as a rare but emerging human pathogen. In 2018, a fluconazole-resistant clinical isolate was reported in China, followed by a 2019 Polish study identifying echinocandin resistance (Wu et al., 2023; Mroczynska and Brillowska-Dabrowska, 2019). This species has been recovered from diverse environmental reservoirs including: soil, marine systems, wastewater, crops, and animals, and displays notable adaptability to harsh conditions (Wu et al., 2023). Wu et al. (2023) suggest that continued anthropogenic pressures, combined with global climate change, may further disturb the ecological niches of C. palmioleophila, increasing its potential to emerge as a more significant human pathogen.

It is now recognised that climate change may be contributing to the emergence of thermotolerant fungal pathogens (Casadevall et al., 2019; George et al., 2025; Jackson et al., 2019; Mora et al., 2022). Candidozyma auris exemplifies this trend, with its rapid, near-simultaneous emergence on multiple continents and high thermotolerance consistent with environmental selection in a warming world (Casadevall et al., 2019; Jackson et al., 2019). Increasing temperatures, salinity, and pollution are altering fungal community dynamics, enabling opportunistic yeasts such as Candida, Cryptococcus, and Rhodotorula to expand into new ecological and host niches (Casadevall et al., 2019; Mora et al., 2022). Moreover, stressors such as heat and fungicide exposure may accelerate mutagenesis and resistance development (Metcalf et al., 2025). These findings reinforce the need for a One Health framework, as environmental reservoirs of antifungal-resistant yeasts pose an increasing threat to human health (George et al., 2025; Daneshnia et al., 2022).

5 Conclusion

The emergence of azole cross-resistant yeast pathogens represents a critical One Health challenge, with wide-reaching implications for human and animal health, environmental integrity, and global food security. This review synthesises current evidence implicating the widespread use of demethylation inhibitor (DMI) fungicides in agriculture as a selective pressure contributing to the evolution of resistance to clinical azoles in yeast species. Structural similarities between agricultural DMIs and medical azoles enable shared resistance mechanisms to be co-selected across environmental and clinical settings. Moreover, environmental cycling of resistant strains, mediated by human–animal–ecosystem interactions, amplifies the risk of resistance dissemination.

Ultimately, despite growing research, the transmission routes linking environmental reservoirs to clinical settings remain poorly understood. Proposed pathways often rely on stochastic exposure and fail to account for the high prevalence of resistant strains in healthcare environments. Notably, wastewater treatment systems require closer scrutiny, as clinically relevant resistant fungi have been detected in treated drinking water (Mhlongo et al., 2019), suggesting that current treatment processes may be insufficient. Robust surveillance across environmental reservoirs, especially wastewater systems, is essential to clarify transmission dynamics.

A central issue is that resistance arising in the environment, beyond direct clinical settings, fundamentally undermines traditional antimicrobial stewardship approaches. Rational prescribing alone cannot contain resistance acquired through fungicide exposure in soil, water, and agricultural run-off. Therefore, a broader strategy is required, one that incorporates comprehensive environmental surveillance, targeted infection prevention, and mitigation of ecological reservoirs of resistance.

The continued use of DMIs to control plant fungal pathogens exacerbates this problem by exerting non-specific pressure on fungal communities. These agents disrupt beneficial saprophytic fungi that help suppress opportunistic pathogens, such as Candida, altering fungal ecology and opening niches for resistant organisms to thrive (reviewed in Azevedo et al., 2015; Hof, 2001). Additionally, some DMIs like clotrimazole are known to interfere with mammalian cytochrome P450 enzymes, potentially causing endocrine disruption even at low environmental concentrations (Jørgensen and Heick, 2021; Draskau and Svingen, 2022). Thus, the ecological and toxicological consequences of azole use extend beyond resistance alone.

Reducing reliance on azole fungicides that overlap structurally with clinical antifungals is an obvious but partial solution. Encouraging the use of alternative DMIs or non-azole fungicides could help preserve the efficacy of key medical treatments. However, this strategy fails to fully address the broader environmental impacts of fungicide use and does not resolve the competing imperative of ensuring global food security. With fungal crop pathogens responsible for devastating yield losses worldwide, sustainable agricultural productivity remains non-negotiable.

Many aspects of the One Health framework for cross-resistance in pathogenic yeast remain underexplored. The molecular mechanisms underlying cross resistance are not well defined, it is unclear whether cross resistance constitutes a distinct process, whether specific DMIs differentially select for cross resistance, or if fitness trade-offs shape its evolution. Empirical studies are needed to map the developmental trajectories of cross resistance and assess the stability and transmissibility of cross resistance phenotypes. Additionally, environmental isolates of pathogenic yeast are often dismissed as contaminants, potentially overlooking true ecological niches that may serve as resistance hotspots. Current cross resistance research is largely limited to N. glabratus and C. parapsilosis, despite global variation in yeast species distribution. Climate differences and patterns of agricultural azole use may further influence cross resistance emergence. Broader surveillance across species, climates, and regions is essential to assess the global risk of cross-resistance.

In conclusion, addressing the threat of cross-resistance requires a multifaceted and integrated approach. Solutions must account for both clinical and agricultural priorities, balancing the urgent need to safeguard antifungal efficacy with the equally pressing demand to secure the global food supply. This will require interdisciplinary collaboration, policy innovation, and investment in sustainable disease control technologies underpinned by a unified One Health framework.

Author contributions

JA: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. EH: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. ChatGPT was used to increase readability of the manuscript after the initial draft, in certain sections.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmad, K. M., Kokošar, J., Guo, X., Gu, Z., Ishchuk, O. P., and Piškur, J. (2014). Genome structure and dynamics of the yeast pathogen Candida glabrata. FEMS Yeast Res. 14, 529–535. doi: 10.1111/1567-1364.12145

Akinbobola, A. B., Kean, R., Hanifi, S. M. A., and Quilliam, R. S. (2023). Environmental reservoirs of the drug-resistant pathogenic yeast Candida auris. PLoS Pathog. 19:e1011268. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011268

Akinbobola, A., Kean, R., and Quilliam, R. S. (2024). Plastic pollution as a novel reservoir for the environmental survival of the drug resistant fungal pathogen Candida auris. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 198:115841. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.115841

Alcoceba, E., Gómez, A., Lara-Esbrí, P., Oliver, A., Beltrán, A. F., Ayestarán, I., et al. (2022). Fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis clonally related genotypes: first report proving the presence of endemic isolates harbouring the Y132F ERG11 gene substitution in Spain. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 28, 1113–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.02.025

Al-Yasiri, M. H., Normand, A. C., L’Ollivier, C., Lachaud, L., Bourgeois, S., Rebaudet, S., et al. (2016). Opportunistic fungal pathogen Candida glabrata circulates between humans and yellow-legged gulls. Sci. Rep. 6:36157. doi: 10.1038/srep36157

Amar, B. (2021). “Current status of fusarium and their management strategies” in Fusarium. ed. M. Seyed Mahyar (Rijeka: IntechOpen).

Amprayn, K.-o., Rose, M. T., Kecskés, M., Pereg, L., Nguyen, H. T., and Kennedy, I. R. (2012). Plant growth promoting characteristics of soil yeast (Candida tropicalis HY) and its effectiveness for promoting rice growth. Appl. Soil Ecol. 61, 295–299. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2011.11.009

Arora, P., Singh, P., Wang, Y., Yadav, A., Pawar, K., Singh, A., et al. (2021). Environmental isolation of Candida auris from the coastal wetlands of Andaman Islands. India. mBio 12:3181. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03181-20

Assress, H. A., Selvarajan, R., Nyoni, H., Ntushelo, K., Mamba, B. B., and Msagati, T. A. M. (2019). Diversity, co-occurrence and implications of fungal communities in wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Rep. 9:14056. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50624-z

Assress, H. A., Selvarajan, R., Nyoni, H., Ogola, H. J. O., Mamba, B. B., and Msagati, T. A. M. (2021). Azole antifungal resistance in fungal isolates from wastewater treatment plant effluents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 28, 3217–3229. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-10688-1

Azevedo, M. M., Faria-Ramos, I., Cruz, L. C., Pina-Vaz, C., and Gonçalves Rodrigues, A. (2015). Genesis of azole antifungal resistance from agriculture to clinical settings. J. Agric. Food Chem. 63, 7463–7468. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02728

Babler, K., Sharkey, M., Arenas, S., Amirali, A., Beaver, C., Comerford, S., et al. (2023). Detection of the clinically persistent, pathogenic yeast spp. Candida auris from hospital and municipal wastewater in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Sci. Total Environ. 898:165459. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165459

Bensasson, D., Dicks, J., Ludwig, J. M., Bond, C. J., Elliston, A., Roberts, I. N., et al. (2019). Diverse lineages of Candida albicans live on old oaks. Genetics 211, 277–288. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.301482

Bhattacharya, S., Sae-Tia, S., and Fries, B. C. (2020). Candidiasis and mechanisms of antifungal resistance. Antibiotics 9:312. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9060312

Boonsilp, S., Homkaew, A., Phumisantiphong, U., Nutalai, D., and Wongsuk, T. (2021). Species Distribution, Antifungal Susceptibility, and Molecular Epidemiology of Candida Species Causing Candidemia in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand. J Fungi 7:577. doi: 10.3390/jof7070577

Branco, J., Miranda, I. M., and Rodrigues, A. G. (2023). Candida parapsilosis virulence and antifungal resistance mechanisms: a comprehensive review of key determinants. J Fungi 9:80. doi: 10.3390/jof9010080

Branda Dos Reis, C., Otenio, M. H., Junior, A. M. M., Maia Dornelas, J. C., Fonseca do Carmo, P. H., Viana, R. O., et al. (2024). Virulence profile of Candida spp. isolated from an anaerobic biodigester supplied with dairy cattle waste. Microb. Pathog. 187:106516. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2023.106516

Brilhante, R. S. N., Alencar, L. P., Bandeira, S. P., Sales, J. A., Evangelista, A. J. J., Serpa, R., et al. (2019). Exposure of Candida parapsilosis complex to agricultural azoles: an overview of the role of environmental determinants for the development of resistance. Sci. Total Environ. 650, 1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.096

Buratti, S., Girometta, C. E., Baiguera, R. M., Barucco, B., Bernardi, M., de Girolamo, G., et al. (2022). Fungal diversity in two wastewater treatment plants in North Italy. Microorganisms 10:1096. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10061096

Carpouron, J. E., de Hoog, S., Gentekaki, E., and Hyde, K. D. (2022). Emerging animal-associated fungal diseases. J Fungi (Basel) 8:6. doi: 10.3390/jof8060611

Carvalho, C., Yang, J., Vogan, A., Maganti, H., Yamamura, D., and Xu, J. (2014). Clinical and tree hollow populations of human pathogenic yeast in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada are different. Mycoses 57, 271–283. doi: 10.1111/myc.12156

Casadevall, A., Kontoyiannis, D. P., and Robert, V. (2019). On the emergence of Candida auris: climate change, azoles, Swamps, and Birds. mBio 10:4. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01397-19

Castelo-Branco, D., Lockhart, S. R., Chen, Y. C., Santos, D. A., Hagen, F., Hawkins, N. J., et al. (2022). Collateral consequences of agricultural fungicides on pathogenic yeasts: a one health perspective to tackle azole resistance. Mycoses 65, 303–311. doi: 10.1111/myc.13404

Castelo-Branco, D. D. S. C. M. (2020). Azole resistance in Candida from animals calls for the one health approach to tackle the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. Med. Mycol. 58, 896–905. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myz135

Chaabane, F., Graf, A., Jequier, L., and Coste, A. T. (2019). Review on antifungal resistance mechanisms in the emerging pathogen Candida auris. Front. Microbiol. 10:2788. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02788

Chaieb, K., Kouidhi, B., Zmantar, T., Mahdouani, K., and Bakhrouf, A. (2011). Starvation survival of Candida albicans in various water microcosms. J. Basic Microbiol. 51, 357–363. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201000298

Chen, P. Y., Chuang, Y. C., Wu, U. I., Sun, H. Y., Wang, J. T., Sheng, W. H., et al. (2019). Clonality of fluconazole-nonsusceptible Candida tropicalis in bloodstream infections, Taiwan, 2011-2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 25, 1660–1667. doi: 10.3201/eid2509.190520

Chen, Y. Z., Tseng, K. Y., Wang, S. C., Huang, C. L., Lin, C. C., Zhou, Z. L., et al. (2023). Fruits are vehicles of drug-resistant pathogenic Candida tropicalis. Microbiol Spectr 11:e0147123. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01471-23

Chong, Y., Ito, Y., Kamimura, T., Shimoda, S., Miyamoto, T., Akashi, K., et al. (2012). Fatal candidemia caused by azole-resistant Candida tropicalis in patients with hematological malignancies. J. Infect. Chemother. 18, 741–746. doi: 10.1007/s10156-012-0412-9

Cordeiro Rde, A., de Oliveira, J. S., Castelo-Branco Dde, S., Teixeira, T., Marques, C. E., Kamimura, F. J., et al. (2015). Candida tropicalis isolates obtained from veterinary sources show resistance to azoles and produce virulence factors. Med. Mycol. 53, 145–152. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myu081

Corkley, I., Fraaije, B., and Hawkins, N. (2022). Fungicide resistance management: maximizing the effective life of plant protection products. Plant Pathol. 71, 150–169. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13467

Correa-Moreira, D., da Costa, G. L., de Lima Neto, R. G., Pinto, T., Salomao, B., Fumian, T. M., et al. (2024). Screening of Candida spp. in wastewater in Brazil during COVID-19 pandemic: workflow for monitoring fungal pathogens. BMC Biotechnol. 24:43. doi: 10.1186/s12896-024-00868-z

Cowen, L. E., Sanglard, D., Howard, S. J., Rogers, P. D., and Perlin, D. S. (2014). Mechanisms of antifungal drug resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 5:a019752. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019752

Crump, K., and Edlinds, T. D. (2004). “Agricultural fungicides may select for azole antifungal resistance in pathogenic Candida,” in 44th Interscience Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington.

Czajka, K. M., Venkataraman, K., Brabant-Kirwan, D., Santi, S. A., Verschoor, C., Appanna, V. D., et al. (2023). Molecular mechanisms associated with antifungal resistance in pathogenic Candida species. Cells 12:655. doi: 10.3390/cells12222655

Daneshnia, F., de Almeida Júnior, J. N., Ilkit, M., Lombardi, L., Perry, A. M., Gao, M., et al. (2023). Worldwide emergence of fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis: current framework and future research roadmap. Lancet Microbe 4, e470–e480. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00067-8

Daneshnia, F., Hilmioğlu Polat, S., Ilkit, M., Shor, E., de Almeida Júnior, J. N., Favarello, L. M., et al. (2022). Determinants of fluconazole resistance and the efficacy of fluconazole and milbemycin oxim combination against Candida parapsilosis clinical isolates from Brazil and Turkey. Front Fungal Biol 3:906681. doi: 10.3389/ffunb.2022.906681

De Carolis, E., Magri, C., Camarlinghi, G., Ivagnes, V., Spruijtenburg, B., Meijer, E. F., et al. (2024). Follow the path: unveiling an azole resistant Candida parapsilosis outbreak by FTIR spectroscopy and STR analysis. J Fungi (Basel) 10:753. doi: 10.3390/jof10110753

Deng, X., Li, H., Wu, A., He, J., Mao, X., Dai, Z., et al. (2025). Composition, influencing factors, and effects on host nutrient metabolism of Fungi in gastrointestinal tract of Monogastric animals. Animals (Basel) 15:5. doi: 10.3390/ani15050710

Denning, D. W. (2024). Global incidence and mortality of severe fungal disease - author's reply. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24, e428–e438. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00692-8

Devanathan, N., Vivek Srinivas, M., Vasu, J., Chaluva, S., and Mukhopadhyay, H. K. (2024). Molecular detection and genetic analysis of Candida species isolated from bovine clinical mastitis in India. Vet Res Forum 15, 509–514. doi: 10.30466/vrf.2024.2008702.3968

Draskau, M. K., and Svingen, T. (2022). Azole fungicides and their endocrine disrupting properties: perspectives on sex hormone-dependent reproductive development. Front Toxicol 4:883254. doi: 10.3389/ftox.2022.883254

Drumonde-Neves, J., Franco-Duarte, R., Lima, T., Schuller, D., and Pais, C. (2017). Association between grape yeast communities and the vineyard ecosystems. PLoS One 12:e0169883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169883

Du, J., Wang, X., Luo, H., Wang, Y., Liu, X., and Zhou, X. (2018). Epidemiological investigation of non-albicans Candida species recovered from mycotic mastitis of cows in Yinchuan, Ningxia of China. BMC Vet. Res. 14:251. doi: 10.1186/s12917-018-1564-3

Escandon, P. (2022). Novel environmental niches for Candida auris: isolation from a coastal habitat in Colombia. J Fungi 8:748. doi: 10.3390/jof8070748

Fang, W., Wu, J., Cheng, M., Zhu, X., du, M., Chen, C., et al. (2023). Diagnosis of invasive fungal infections: challenges and recent developments. J. Biomed. Sci. 30:42. doi: 10.1186/s12929-023-00926-2

Faria-Ramos, I., Tavares, P. R., Farinha, S., Neves-Maia, J., Miranda, I. M., Silva, R. M., et al. (2014). Environmental azole fungicide, prochloraz, can induce cross-resistance to medical triazoles in Candida glabrata. FEMS Yeast Res. 14, 1119–1123. doi: 10.1111/1567-1364.12193

Fisher, M. C., Alastruey-Izquierdo, A., Berman, J., Bicanic, T., Bignell, E. M., Bowyer, P., et al. (2022). Tackling the emerging threat of antifungal resistance to human health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 557–571. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00720-1

Fisher, M. C., Hawkins, N. J., Sanglard, D., and Gurr, S. J. (2018). Worldwide emergence of resistance to antifungal drugs challenges human health and food security. Science 360, 739–742. doi: 10.1126/science.aap7999

FRAC. (2025). Fungal control agents sorted by cross-resistance pattern and mode of action. Available online at: https://www.frac.info/media/ljsi3qrv/frac-code-list-2025.pdf (accessed August 14, 2025).

Gabaldón, T., and Fairhead, C. (2019). Genomes shed light on the secret life of Candida glabrata: not so asexual, not so commensal. Curr. Genet. 65, 93–98. doi: 10.1007/s00294-018-0867-z

Garcia-Bustos, V., Rosario Medina, I., Cabañero Navalón, M. D., Ruiz Gaitán, A. C., Pemán, J., and Acosta-Hernández, B. (2024). Candida spp. in cetaceans: neglected emerging challenges in marine ecosystems. Microorganisms 12:128. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12061128

Geissel, B., Loiko, V., Klugherz, I., Zhu, Z., Wagener, N., Kurzai, O., et al. (2018). Azole-induced cell wall carbohydrate patches kill Aspergillus fumigatus. Nat. Commun. 9:3098. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05497-7

George, M. E., Gaitor, T. T., Cluck, D. B., Henao-Martinez, A. F., Sells, D. B., and Chastain, V. (2025). The impact of climate change on the epidemiology of fungal infections: implications for diagnosis, treatment, and public health strategies. Ther Adv Infect Dis 12:20499361251313841. doi: 10.1177/20499361251313841

Gisi, U. (2022). Crossover between the control of fungal pathogens in medicine and the wider environment, and the threat of antifungal resistance. Plant Pathol. 71, 131–149. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13429

Glushakova, A., Rodionova, E., and Kachalkin, A. (2024). Evaluation of opportunistic yeasts Candida parapsilosis and Candida tropicalis in topsoil of children’s playgrounds. Biologia 79, 1585–1597. doi: 10.1007/s11756-024-01643-3

Gomez Londono, L. F., and Brewer, M. T. (2023). Detection of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in the environment from air, plant debris, compost, and soil. PLoS One 18:e0282499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0282499

Gurleen, K., and Savio, R. (2016). Prevalence of Candida in Diarrhoeal stool. J. Dental Med. Sci. 15, 47–49. doi: 10.9790/0853-1504124749

Hamlin, J. A. P., Dias, G. B., Bergman, C. M., and Bensasson, D. (2019). Phased diploid genome assemblies for three strains of Candida albicans from oak. Trees 9, 3547–3554. doi: 10.1534/g3.119.400486

Handelman, M., Meir, Z., Scott, J., Shadkchan, Y., Liu, W., Ben-Ami, R., et al. (2021). Point Mutation or Overexpression of Aspergillus fumigatus cyp51B, Encoding Lanosterol 14alpha-Sterol Demethylase, Leads to Triazole Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 65:21. doi: 10.1128/aac.01252-21

Hawkins, N. J. A., Fraaije, A., and Gesellschaft, D. P. (2016). Adaptive Landscapes in Fungicide Resistance: Fitness, Epista.

Hof, H. (2001). Critical annotations to the use of azole antifungals for plant protection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 2987–2990. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.11.2987-2990.2001

Hokken, M. W. J., Zwaan, B. J., Melchers, W. J. G., and Verweij, P. E. (2019). Facilitators of adaptation and antifungal resistance mechanisms in clinically relevant fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 132:103254. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103254

Hu, T., Zheng, Q., Cao, C., Li, S., Huang, Y., Guan, Z., et al. (2025). An agricultural triazole induces genomic instability and haploid cell formation in the human fungal pathogen Candida tropicalis. PLoS Biol. 23:e3003062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3003062

Hwang, I. J., Kwon, Y. J., Lim, H. J., Hong, K. H., Lee, H., Yong, D., et al. (2024). Nosocomial transmission of fluconazole-resistant Candida glabrata bloodstream isolates revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Microbiol Spectr 12:e0088324. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00883-24

Jackson, B. R., Chow, N., Forsberg, K., Litvintseva, A. P., Lockhart, S. R., Welsh, R., et al. (2019). On the origins of a species: what might explain the rise of Candida auris? J Fungi 5:58. doi: 10.3390/jof5030058

Jin, Y., and Lin, D. (2005). Fungal urinary tract infections in the dog and cat: a retrospective study (2001-2004). J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 41, 373–381. doi: 10.5326/0410373

Jørgensen, L. N., and Heick, T. M. (2021). Azole use in agriculture, horticulture, and wood preservation - is it indispensable? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11:730297. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.730297

Kaewkrajay, C., Putchakarn, S., and Limtong, S. (2021). Cultivable yeasts associated with marine sponges in the Gulf of Thailand. South China Sea. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 114, 253–274. doi: 10.1007/s10482-021-01518-6

Kahle, M., Buerge, I. J., Hauser, A., Müller, M. D., and Poiger, T. (2008). Azole fungicides: occurrence and fate in wastewater and surface waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 7193–7200. doi: 10.1021/es8009309

Kumamoto, C. A., Gresnigt, M. S., and Hube, B. (2020). The gut, the bad and the harmless: Candida albicans as a commensal and opportunistic pathogen in the intestine. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 56, 7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2020.05.006

Lamberth, C. (2022). Latest research trends in agrochemical fungicides: any learnings for pharmaceutical antifungals? ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 13, 895–903. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00113

Lee, W., and Lee, D. G. (2018). Reactive oxygen species modulate itraconazole-induced apoptosis via mitochondrial disruption in Candida albicans. Free Radic. Res. 52, 39–50. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2017.1407412

Lee, Y., Puumala, E., Robbins, N., and Cowen, L. E. (2021). Antifungal drug resistance: molecular mechanisms in Candida albicans and beyond. Chem. Rev. 121, 3390–3411. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00199

Legrand, M., Chan, C. L., Jauert, P. A., and Kirkpatrick, D. T. (2007). Role of DNA mismatch repair and double-strand break repair in genome stability and antifungal drug resistance in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 6, 2194–2205. doi: 10.1128/EC.00299-07

Lepesheva, G. I., Hargrove, T. Y., Anderson, S., Kleshchenko, Y., Furtak, V., Wawrzak, Z., et al. (2010). Structural insights into inhibition of sterol 14alpha-demethylase in the human pathogen Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 25582–25590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.133215

Lepesheva, G. I., and Waterman, M. R. (2011). Structural basis for conservation in the CYP51 family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1814, 88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.06.006

Li, S., Zhang, J., Cao, S., Han, R., Yuan, Y., Yang, J., et al. (2011). Homology modeling, molecular docking and spectra assay studies of sterol 14alpha-demethylase from Penicillium digitatum. Biotechnol. Lett. 33, 2005–2011. doi: 10.1007/s10529-011-0657-x

Lima, R., Ribeiro, F. C., Colombo, A. L., and de Almeida, J. N. Jr. (2022). The emerging threat antifungal-resistant Candida tropicalis in humans, animals, and environment. Front Fungal Biol 3:957021. doi: 10.3389/ffunb.2022.957021

Limon, J. J., Skalski, J. H., and Underhill, D. M. (2017). Commensal Fungi in health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 22, 156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.002

Lo, H.-J., Tsai, S. H., Chu, W. L., Chen, Y. Z., Zhou, Z. L., Chen, H. F., et al. (2017). Fruits as the vehicle of drug resistant pathogenic yeasts. J. Infect. 75, 254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.06.005

Mackenzie, J. S., and Jeggo, M. (2019). The one health approach-why is it so important? Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 4:288. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed4020088

Maganti, H., Bartfai, D., and Xu, J. (2012). Ecological structuring of yeasts associated with trees around Hamilton, Ontario. Canada. FEMS Yeast Res 12, 9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2011.00756.x

Mair, W. J., Thomas, G. J., Dodhia, K., Hills, A. L., Jayasena, K. W., Ellwood, S. R., et al. (2020). Parallel evolution of multiple mechanisms for demethylase inhibitor fungicide resistance in the barley pathogen Pyrenophora teresf. sp. maculata. Fungal Genet. Biol. 145:103475. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2020.103475

Marta, T., and Alina, K.-S. Candida biofilms: Environmental and clinical aspects, in the yeast role in medical applications, (2017), IntechOpen: Rijeka. p. Ch. 2.

Mataraci-Kara, E., Ataman, M., Yilmaz, G., and Ozbek-Celik, B. (2020). Evaluation of antifungal and disinfectant-resistant Candida species isolated from hospital wastewater. Arch. Microbiol. 202, 2543–2550. doi: 10.1007/s00203-020-01975-z

Mba, I., and Nweze, E. (2019). Antifungal resistance profile and enzymatic activity of Candida species recovered from human and animal samples. Bio-Research 17, 1044A–1055A. doi: 10.4314/br.v17i1.4

Metcalf, R., Akinbobola, A., Woodford, L., and Quilliam, R. S. (2025). Thermotolerance, virulence, and drug resistance of human pathogenic Candida species colonising plastic pollution in aquatic ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 32, 14993–15005. doi: 10.1007/s11356-025-36558-2

Mhlongo, N. T., Tekere, M., and Sibanda, T. (2019). Prevalence and public health implications of mycotoxigenic fungi in treated drinking water systems. J. Water Health 17, 517–531. doi: 10.2166/wh.2019.122

Monk, B. C., Sagatova, A. A., Hosseini, P., Ruma, Y. N., Wilson, R. K., and Keniya, M. V. (2020). Fungal Lanosterol 14alpha-demethylase: a target for next-generation antifungal design. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 1868:140206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2019.02.008

Mora, C., McKenzie, T., Gaw, I. M., Dean, J. M., von Hammerstein, H., Knudson, T. A., et al. (2022). Over half of known human pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 869–875. doi: 10.1038/s41558-022-01426-1

Mroczynska, M., and Brillowska-Dabrowska, A. (2019). First report on echinocandin resistant polish Candida isolates. Acta Biochim. Pol. 66, 361–364. doi: 10.18388/abp.2019_2826

Muller, F. M., Staudigel, A., Salvenmoser, S., Tredup, A., Miltenberger, R., and Herrmann, J. V. (2007). Cross-resistance to medical and agricultural azole drugs in yeasts from the oropharynx of human immunodeficiency virus patients and from environmental Bavarian vine grapes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 3014–3016. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00459-07

Nelson, D. R. (2018). Cytochrome P450 diversity in the tree of life. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 1866, 141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2017.05.003

Ockleford, C., Adriaanse, P., Berny, P., Brock, T., Duquesne, S., Grilli, S., et al. (2018). Scientific opinion on the state of the science on pesticide risk assessment for amphibians and reptiles. EFSA J. 16:e05125. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5125

Olita, T., Stankovic, M., Sung, B., Jones, M., and Gibberd, M. (2024). Growers' perceptions and attitudes towards fungicide resistance extension services. Sci. Rep. 14:6821. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-57530-z

Opulente, D. A., Langdon, Q. K., Buh, K. V., Haase, M. A. B., Sylvester, K., Moriarty, R. V., et al. (2019). Pathogenic budding yeasts isolated outside of clinical settings. FEMS Yeast Res. 19:032. doi: 10.1093/femsyr/foz032

Osa, S., Tashiro, S., Igarashi, Y., Watabe, Y., Liu, X., Enoki, Y., et al. (2020). Azoles versus conventional amphotericin B for the treatment of candidemia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Infect. Chemother. 26, 1232–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2020.07.019

Osset-Trénor, P., Pascual-Ahuir, A., and Proft, M. (2023). Fungal drug response and antimicrobial resistance. J. Fungi 9:565. doi: 10.3390/jof9050565

Park, J. H., Ryu, S. H., Lee, J. Y., Kim, H. J., Kwak, S. H., Jung, J., et al. (2019). Airborne fungal spores and invasive aspergillosis in hematologic units in a tertiary hospital during construction: a prospective cohort study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 8:88. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0543-1

Parker, J. E., Warrilow, A. G., Price, C. L., Mullins, J. G., Kelly, D. E., and Kelly, S. L. (2014). Resistance to antifungals that target CYP51. J. Chem. Biol. 7, 143–161. doi: 10.1007/s12154-014-0121-1

Paulussen, C., Hallsworth, J. E., Álvarez-Pérez, S., Nierman, W. C., Hamill, P. G., Blain, D., et al. (2017). Ecology of aspergillosis: insights into the pathogenic potency of aspergillus fumigatus and some other aspergillus species. Microb. Biotechnol. 10, 296–322. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12367

Podust, L. M., Poulos, T. L., and Waterman, M. R. (2001). Crystal structure of cytochrome P450 14alpha -sterol demethylase (CYP51) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis in complex with azole inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 3068–3073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061562898

Potocki, L., Baran, A., Oklejewicz, B., Szpyrka, E., Podbielska, M., and Schwarzbacherová, V. (2020). Synthetic pesticides used in agricultural production promote genetic instability and metabolic variability in Candida spp. Genes 11:848. doi: 10.3390/genes11080848

Qin, J., Li, R., Raes, J., Arumugam, M., Burgdorf, K. S., Manichanh, C., et al. (2010). A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464, 59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821

Queiroz-Aaltonen, I., Melo-Neto, M., Fonseca, L., Wanderlei, D., and Maranhão, F. (2021). Molecular detection of medically important Candida species from droppings of pigeons (Columbiformes) and captive birds (Passeriformes and Psittaciformes). Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2:64. doi: 10.1590/1678-4324-2021200763

Rallos, L. E., and Baudoin, A. B. (2016). Co-occurrence of two allelic variants of CYP51 in Erysiphe necator and their correlation with over-expression for DMI resistance. PLoS One 11:e0148025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148025

Ratnadass, A., and Martin, T. (2022). Crop protection practices and risks associated with infectious tropical parasitic diseases. Sci. Total Environ. 823:153633. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153633

Reagan, K. L., Dear, J. D., Kass, P. H., and Sykes, J. E. (2019). Risk factors for Candida urinary tract infections in dogs and cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 33, 648–653. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15444

Rhodes, J., Abdolrasouli, A., Dunne, K., Sewell, T. R., Zhang, Y., Ballard, E., et al. (2022). Population genomics confirms acquisition of drug-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus infection by humans from the environment. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 663–674. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01091-2

Rocha, M. F., Alencar, L. P., Paiva, M. A., Melo, L. M., Bandeira, S. P., Ponte, Y. B., et al. (2016). Cross-resistance to fluconazole induced by exposure to the agricultural azole tetraconazole: an environmental resistance school? Mycoses 59, 281–290. doi: 10.1111/myc.12457

Rodrigues, M. L. (2018). The multifunctional fungal Ergosterol. MBio 9:5. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01755-18

Rosario Medina, I., Román Fuentes, L., Batista Arteaga, M., Real Valcárcel, F., Acosta Arbelo, F., Padilla del Castillo, D., et al. (2017). Pigeons and their droppings as reservoirs of Candida and other zoonotic yeasts. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 34, 211–214. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2017.03.001

Ruge, E., Korting, H. C., and Borelli, C. (2005). Current state of three-dimensional characterisation of antifungal targets and its use for molecular modelling in drug design. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 26, 427–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.09.006

Sagatova, A. A., Keniya, M. V., Wilson, R. K., Sabherwal, M., Tyndall, J. D. A., and Monk, B. C. (2016). Triazole resistance mediated by mutations of a conserved active site tyrosine in fungal lanosterol 14alpha-demethylase. Sci. Rep. 6:26213. doi: 10.1038/srep26213

Salazar-Hamm, P. S., Gadek, C. R., Mann, M. A., Steinberg, M., Montoya, K. N., Behnia, M., et al. (2025). Phylogenetic and ecological drivers of the avian lung mycobiome and its potentially pathogenic component. Commun Biol 8:634. doi: 10.1038/s42003-025-08041-8

Salazar-Hamm, P. S., Montoya, K. N., Montoya, L., Cook, K., Liphardt, S., Taylor, J. W., et al. (2022). Breathing can be dangerous: opportunistic fungal pathogens and the diverse community of the small mammal lung mycobiome. Front. Fungal Biol. 3:996574. doi: 10.3389/ffunb.2022.996574

Samarasinghe, H., Lu, Y., Aljohani, R., al-Amad, A., Yoell, H., and Xu, J. (2021). Global patterns in culturable soil yeast diversity. iScience 24:103098. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103098

Sautour, M., Lemaître, J. P., Ranjard, L., Truntzer, C., Basmaciyan, L., Depret, G., et al. (2021). Detection and survival of Candida albicans in soils. Environ. DNA 3, 1093–1101. doi: 10.1002/edn3.230

Shafiei, M., Peyton, L., Hashemzadeh, M., and Foroumadi, A. (2020). History of the development of antifungal azoles: a review on structures, SAR, and mechanism of action. Bioorg. Chem. 104:104240. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104240

Shah, K., Deshpande, M., and Shah, P. (2024). Healthcare-associated fungal infections and emerging pathogens during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Fungal Biol 5:1339911. doi: 10.3389/ffunb.2024.1339911

Sharma, M., and Chakrabarti, A. (2020). On the origin of Candida auris: ancestor, Environmental Stresses, and Antiseptics. mBio 11, 10–1128. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02102-20

Shi, N., Zheng, Q., and Zhang, H. (2020). Molecular dynamics investigations of binding mechanism for Triazoles inhibitors to CYP51. Front. Mol. Biosci. 7:586540. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.586540

Sidrim, J. J. C., de Maria, G. L., Paiva, M. A. N., Araújo, G. S., da Graça-Filho, R. V., de Oliveira, J. S., et al. (2021). Azole-resilient biofilms and non-wild Type C. albicans among Candida species isolated from agricultural soils cultivated with azole fungicides: an environmental issue? Microb. Ecol. 82, 1080–1083. doi: 10.1007/s00248-021-01694-y

Souza, C. M., Bezerra, B. T., Mellon, D. A., and de Oliveira, H. C. (2025). The evolution of antifungal therapy: traditional agents, current challenges and future perspectives. Curr Res Microb Sci 8:100341. doi: 10.1016/j.crmicr.2025.100341

Srejber, M., Navratilova, V., Paloncyova, M., Bazgier, V., Berka, K., Anzenbacher, P., et al. (2018). Membrane-attached mammalian cytochromes P450: an overview of the membrane's effects on structure, drug binding, and interactions with redox partners. J. Inorg. Biochem. 183, 117–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2018.03.002

Steffen, H. C., Smith, K., van Deventer, C., Weiskerger, C., Bosch, C., Brandão, J., et al. (2023). Health risk posed by direct ingestion of yeasts from polluted river water. Water Res. 231:119599. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2023.119599

Steinberg, G., and Gurr, S. J. (2020). Fungi, fungicide discovery and global food security. Fungal Genet. Biol. 144:103476. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2020.103476

Stenzel, K., and Vors, J.-P. (2019). Sterol Biosynthesis Inhibitors*. Modern Crop Protection Compounds 22, 797–844. doi: 10.1002/9783527699261

Strickland, D. A., Villani, S. M., and Cox, K. D. (2022). Optimizing use of DMI fungicides for Management of Apple Powdery Mildew Caused by Podosphaera leucotricha in New York state. Plant Dis. 106, 1226–1237. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-21-2025-RE

Stukenbrock, E., and Gurr, S. (2023). Address the growing urgency of fungal disease in crops. Nature 617, 31–34. doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-01465-4

Szulc, J., Okrasa, M., Majchrzycka, K., Sulyok, M., Nowak, A., Ruman, T., et al. (2021). Microbiological and toxicological hazards in sewage treatment plant bioaerosol and dust. Toxins 13:691. doi: 10.3390/toxins13100691

Talazadeh, F., Ghorbanpoor, M., and Masoudinezhad, M. (2023). Phylogenetic analysis of pathogenic Candida spp. in domestic pigeons. Vet res. Forum 14, 431–436. doi: 10.30466/vrf.2022.555179.3499

Talazadeh, F., Ghorbanpoor, M., and Shahriyari, A. (2022). Candidiasis in birds (Galliformes, Anseriformes, Psittaciformes, Passeriformes, and Columbiformes): a focus on antifungal susceptibility pattern of Candida albicans and non-albicans isolates in avian clinical specimens. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 46:100598. doi: 10.1016/j.tcam.2021.100598

Tian, J. H., Yan, C., Nasir, Z. A., Alcega, S. G., Tyrrel, S., and Coulon, F. (2020). Real time detection and characterisation of bioaerosol emissions from wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 721:137629. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137629