- 1Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia

- 2Unhas Fly Research Group, Faculty of Pharmacy, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia

- 3Research Center for Food Technology and Processing, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- 4The Hakubi Center for Advanced Research, Kyoto University, Yoshida-honmachi, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan

- 5Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS), Kyoto University, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan

- 6Immunology Frontier Research Center (IFReC), Osaka University, Suita, Osaka, Japan

- 7Center for Infectious Diseases (CID), Kobe University, Chuo-ku, Kobe, Japan

Introduction

Since May 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported an unprecedented monkeypox virus (MPXV) outbreak affecting multiple non-endemic regions (Zumla et al., 2022). This outbreak is marked by atypical transmission dynamics, allowing sustained spread across areas historically unaffected by the virus. As of June 2025, 158,425 confirmed cases had been reported across 138 countries (WHO, 2025). Phylogenetic analyses identify two clades: Clade I (Central African) and Clade II (West African), differing in geography, clinical severity, and fatality rates (Hermez et al., 2024). Clade I, largely confined to Central and Eastern Africa, causes more severe disease, including encephalitis and sepsis, with fatality rates of 5%−10%. In contrast, Clade II, responsible for most recent cases, has lower virulence (<3% fatality rate) but higher human-to-human transmissibility, driving rapid global spread (Satheshkumar et al., 2025; Srivastava et al., 2025). Since January 2024, a total of 42,211 Clade IB infections have been reported, with the majority occurring in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (28,874 cases), followed by Uganda (7,874 cases) and Burundi (4,430 cases) (WHO, 2025).

The MPXV outbreak highlights the complex interplay between viral evolution (Zhang et al., 2024), ecological factors (Ogunleye et al., 2023), and host immune responses in driving disease emergence (Yi et al., 2024). Despite its genetic similarity to the variola virus (Chen et al., 2025), the causative agent of smallpox, no specific or effective antiviral treatment is currently available for MPXV (Ghosh et al., 2023). These gaps underscore the urgent need for further research into the virus's biology, pathogenesis, and control strategies. Amid growing concerns about the potential for another pandemic and the limited availability of therapeutic options, a comprehensive understanding of MPXV is essential. Experimental models that facilitate the efficient investigation of infection mechanisms and host responses are critically needed, not only to support the development of more effective therapeutic and preventive strategies but also to identify and validate targets for antiviral drug screening against MPXV.

Biology, transmission, and challenges in modeling MPXV infection

MPXV, a member of the Poxviridae family, possesses a large double-stranded DNA genome of approximately 190 kilobases, encoding nearly 190 proteins (Shchelkunov et al., 2002). Mature virions are ovoid to brick-shaped, featuring surface tubules and a characteristic dumbbell-shaped nucleoprotein core that encloses the viral genome (Shchelkunov et al., 2001). MPXV particles typically measure around 200 nm in diameter and 300 nm in length (Wenner et al., 1968). As an enveloped virus, MPXV exhibits a complex life cycle involving both intracellular and extracellular forms (Lum et al., 2022). Like other poxviruses, replication occurs entirely in the cytoplasm of host cells, where viral factories are formed to support genome replication and virion assembly (Yi et al., 2024).

The transmission of the virus primarily occurs through direct contact with infected animals, bodily fluids, or lesion material (Chen et al., 2025). Close contact facilitates the spread of MPXV in both endemic and non-endemic regions. MPXV enters the host through oral, respiratory, or cutaneous routes, infecting mucosal surfaces or penetrating compromised skin. Once inside, the virus replicates within keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells (Di Giulio and Eckburg, 2004; Damon, 2011). During the initial stage of MPXV infection, viral proteins primarily mediate DNA replication and interact with host targets, leading to antiviral suppression and cell cycle arrest. These proteins are classified into three groups: (1) entry proteins (M1R, E8L, H3L) that enable host cell attachment and membrane fusion; (2) exit proteins (A38R, C23R, C18L) that facilitate virion release; and (3) immunomodulatory proteins (J2L, F3L, A41L, P1L) that alter host cell processes and immune responses to support viral persistence (Wang et al., 2024; Deng et al., 2025). In the late stage of MPXV infection, these proteins are crucial for the assembly of new viral particles. MPXV can spread to regional lymph nodes and subsequently to secondary organs such as the tonsils, spleen, and liver. Viral replication in these tissues triggers secondary viremia, leading to systemic dissemination to distant organs—including the lungs, kidneys, intestines, and skin. This widespread infection results in the characteristic clinical manifestations of Mpox (Di Giulio and Eckburg, 2004; Damon, 2011). Notably, the pathogenicity of human disease is associated with differences between viral strains (Likos et al., 2005).

Research on MPXV and the development of targeted antivirals remain challenging due to limited understanding of its pathogenesis, viral evolution, and immune evasion (Fang et al., 2024). Unlike variola virus, which was extensively studied during the smallpox eradication campaign, MPXV remains underexplored, leaving key gaps in its biological characterization. Progress is further constrained by reliance on traditional animal models such as non-human primates (NHPs) and rodents (Wei et al., 2023). Although these models have advanced knowledge of MPXV pathogenesis, they present major ethical, logistical, and financial limitations (Pastorino et al., 2024). NHP research requires stringent ethical oversight and high-containment BSL-3/4 facilities, making it costly and difficult to scale (Prescott et al., 2021). Rodent models, while more accessible, also demand significant maintenance resources (Hylander et al., 2022). These challenges highlight the urgent need for alternative, cost-effective, and ethically sustainable model systems to accelerate MPXV research and therapeutic discovery.

Drosophila as a model organism for studying MPXV virulence and screening of prospective antivirals

Drosophila melanogaster has become a well-established and versatile alternative model for studying viral infectious diseases. Its significance in biomedical research lies in the evolutionary conservation of innate immune signaling pathways and fundamental cellular processes that are commonly targeted by viruses. For instance, Toll-like receptor signaling, which mediates pathogen recognition and activation of antiviral responses, plays a critical role in both flies and humans (Valanne et al., 2011). Similarly, D. melanogaster employs RNA interference (RNAi) as a primary antiviral defense mechanism, an evolutionarily conserved process that also contributes to antiviral immunity in mammals (Ding and Voinnet, 2007). These conserved pathways enable the use of D. melanogaster as a surrogate system to explore host–virus interactions at the molecular and cellular levels, offering insights that are translatable to higher organisms.

In addition to its immunological relevance, D. melanogaster offers several practical and technical advantages that make it particularly suitable for virological and genetic studies. The species is small, inexpensive to maintain, and can be reared in large numbers under simple laboratory conditions using easily prepared media (Victor Atoki et al., 2025). A single female can lay up to 100 eggs per day and around 2,000 during her lifetime (Giansanti et al., 2025). It also has a rapid life cycle of approximately 10–12 days at 25 °C, allowing rapid generation turnover (Baenas and Wagner, 2019). These features make D. melanogaster ideal for large-scale and high-throughput experiments. In terms of ethical considerations, D. melanogaster research is subject to fewer regulatory restrictions compared to vertebrate or mammalian models. The National Center for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research (NC3Rs) is a UK-based organization promotes the 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) to ensure ethical and humane research practices (NC3Rs, n.d.; European Union, 2010). In line with these principles, the NC3Rs encourages the use of invertebrate models such as D. melanogaster, nematodes, and social amoebae, which are generally not considered suffering, thereby reducing ethical concerns and simplifying institutional approval (NC3Rs).

From a genetic perspective, D. melanogaster represents one of the most genetically accessible model organisms, supported by a comprehensive suite of genetic tools that enable precise and targeted genome manipulation. This is further supported by the fact that D. melanogaster has fewer genes than humans (flies ~14,000 genes vs. humans ~20,000), implying less genetic redundancy and facilitating easier examination of gene function (Hughes et al., 2012). Recent advancements, particularly the implementation of CRISPR/Cas9, the GAL4/UAS system, and RNAi, have enabled precise gene manipulation in a tissue-specific manner (Hughes et al., 2012; Zirin et al., 2022; Meltzer et al., 2019; Mascolo et al., 2022; Qiao et al., 2018; Link et al., 2024; Querenet et al., 2015). These genes can be knocked out or modified to observe how changes in the expression of those genes can influence infection. This combination of biological relevance, cost-efficiency, ethical accessibility, and genetic tractability, makes D. melanogaster an important and practical model for investigating viral pathogenesis, host responses, and the molecular mechanisms underlying infection.

Discussion

MPXV has been shown to induce substantial tissue damage and, in severe instances, lead to mortality in humans. However, the molecular basis of its pathogenicity remains poorly understood. We hypothesize that the pathogenicity of MPXV is primarily driven by viral–host protein interactions that modulate key physiological signaling pathways within the host. Such interactions may alter cellular homeostasis, immune responses, and metabolic regulation, ultimately contributing to disease manifestation. For example, the P1L gene in MPXV, which is homologous to the N1L gene in vaccinia virus (VACV), functions as an anti-apoptotic factor and a modulator of host defense. It has been shown to inhibit NF-κB and IRF3 signaling pathways, both of which play critical roles in orchestrating effective immune responses against viral infection (Deng et al., 2025).

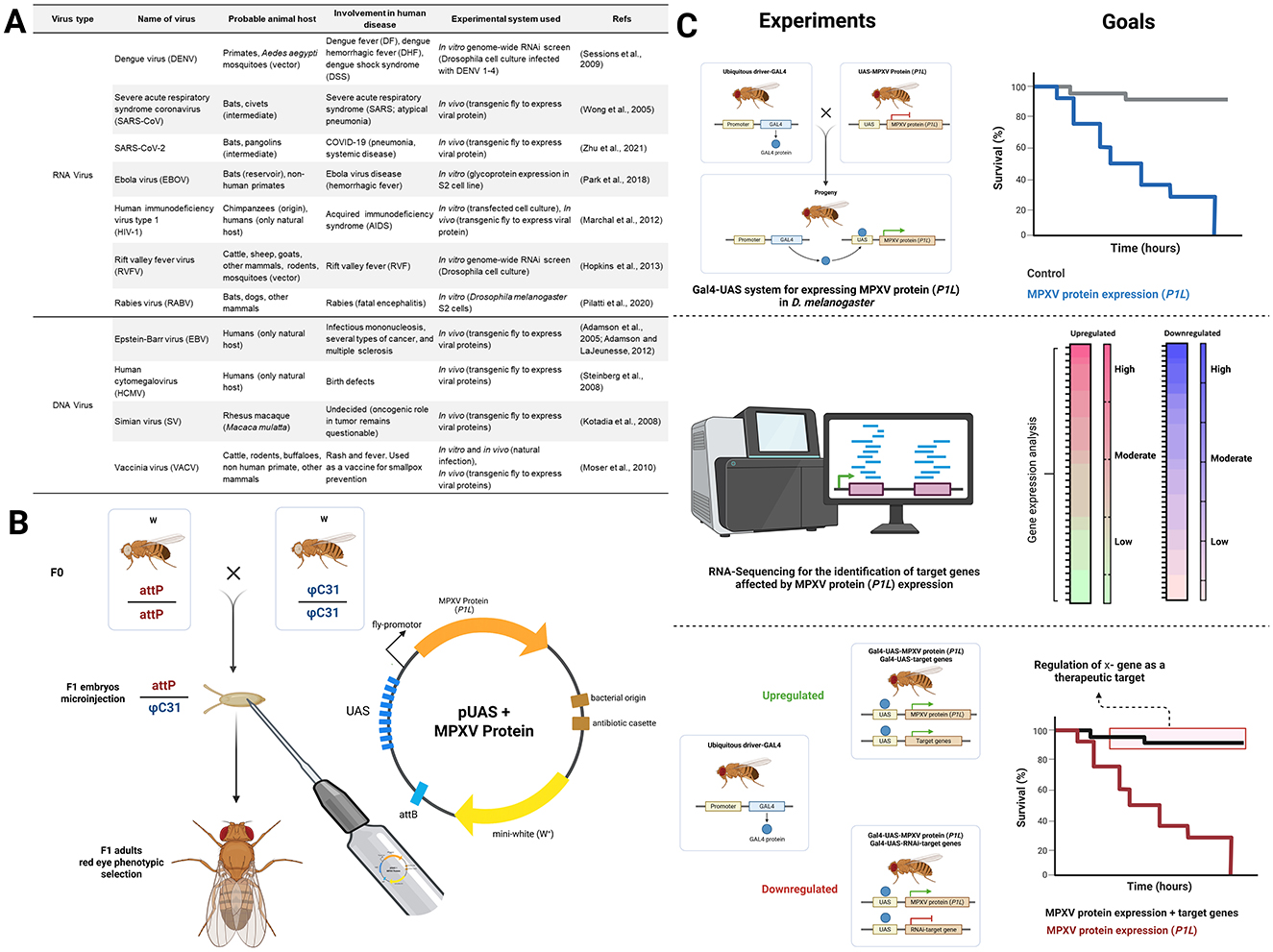

To better elucidate the underlying mechanisms, researchers can use a comprehensive toolkit of transgenic D. melanogaster lines that enable the expression of viral proteins using the GAL4/UAS binary expression system (Link et al., 2024) (see Figure 1C). Although D. melanogaster is not a natural host for MPXV, previous studies have demonstrated that a variety of human viral infections, including both DNA and RNA viruses, can be effectively modeled in D. melanogaster (see Figure 1A) (Sessions et al., 2009; Wong et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2021; Park et al., 2018; Marchal et al., 2012; Hopkins et al., 2013; Pilatti et al., 2020; Adamson et al., 2005; Adamson and LaJeunesse, 2012; Steinberg et al., 2008; Kotadia et al., 2008; Moser et al., 2010). Notably, several of these reported models have successfully expressed viral proteins in transgenic D. melanogaster using the GAL4–UAS system. The GAL4/UAS system allows controlled expression of individual viral genes in specific tissues, facilitating the investigation of their molecular and physiological effects without requiring live viral infection. By expressing MPXV candidate genes such as P1L in targeted D. melanogaster tissues, researchers can systematically assess their impact on host signaling pathways, thereby gaining insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying MPXV-induced pathogenesis and potentially identifying novel therapeutic targets. This approach is particularly advantageous for studying viruses like MPXV that possess restricted host ranges and limited infectivity.

Figure 1. Overview of the prospective model organism for MPXV research. (A) Human viruses studied using Drosophila melanogaster. (B) Representative schematic illustrating UAS-mediated expression of the MPXV protein (example, P1L) in D. melanogaster transgenic lines. The MPXV P1L protein, functions as an anti-apoptotic and immune-modulatory factor by inhibiting NF-κB and IRF3 signaling pathways, which are essential for antiviral responses. (C) Basic design of experimental approaches utilizing D. melanogaster to identify potential therapeutic targets for MPXV. Created in BioRender. Nainu, F. (2025) https://BioRender.com/qj7pv6u.

The initial step involved designing transgenic fly lines that express specific viral proteins (see Figure 1B). Genes encoding these viral proteins were first codon-optimized for efficient translation in D. melanogaster and subsequently cloned into UAS expression vectors. The resulting constructs were integrated into the fly genome via integrase or transposon-mediated transformation to generate UAS–viral protein transgenic lines. These lines were then crossed with tissue-specific GAL4 driver strains to achieve precise spatial and temporal control of viral protein expression. This platform enables in vivo characterization of viral protein functions, host–protein interactions, and associated cytotoxic effects. The expressed viral proteins are further evaluated for toxicity phenotypes, which can be quantified through survival analysis to determine their physiological impact in vivo.

Global host gene responses to viral protein expression are then assessed using RNA sequencing to identify significantly dysregulated genes. Candidate genes identified through transcriptomic analysis are functionally validated using a rescue-based experimental design employing a dual Gal4/UAS system. This approach allows simultaneous manipulation either through overexpression or knockdown (RNAi) of target genes (Zhang et al., 2020), alongside MPXV protein expression to evaluate their protective or pathogenic roles. An improvement in survival following gene manipulation indicates a potential therapeutic role, whereas a further decrease in survival suggests that the gene may exacerbate MPXV-induced toxicity. This integrative approach may offer a robust and scalable platform for identifying critical host and viral factors interaction, thereby facilitating the rational design of targeted therapeutics against MPXV infections while enhancing our mechanistic understanding of viral pathogenesis.

Despite its numerous advantages, D. melanogaster has inherent limitations as a model for therapeutic target screening in MPXV research. According to the DRSC Integrative Ortholog Prediction Tool (DIOPT), which assesses genetic conservation between flies and humans, the number of genes associated with viral diseases is relatively limited. Specifically, 65 human genes are linked to viral diseases, but only 39 of these have identified orthologs in D. melanogaster (Hu et al., 2011). This indicates that only a limited subset of human genes has direct counterparts in flies, likely due to fundamental biological differences such as the absence of an adaptive immune system. Moreover, significant physiological differences, including the lack of certain mammalian organ systems and distinct tissue microenvironments, further constrain the ability to replicate disease phenotypes directly. These limitations highlight the need for subsequent validation in mammalian models and human cell–based systems to confirm the functional conservation of the observed mechanisms. This can be achieved through the analysis of gene and protein expression of human homologs under MPXV natural infection. Such validation would determine whether the molecular targets identified in D. melanogaster exhibit comparable expression patterns and functional roles in mammalian or human systems. By integrating genetic and virological perspectives through the use of the D. melanogaster model, this study emphasizes the value of interdisciplinary approaches in uncovering molecular mechanisms that bridge fundamental genetic insights with virological research.

Author contributions

MM: Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AF: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists (No. 24K20193) and the Hakubi Project of Kyoto University awarded to YO. Additional support was provided by the Thematic Research Group (TRG) Batch I 2025 Grant (No. 00518/UN4.22/PT.01.03/2025) from Hasanuddin University, awarded to FN and YO.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adamson, A., and LaJeunesse, D. (2012). A study of Epstein-Barr virus BRLF1 activity in a Drosophila model system. ScientificWorldJournal 2012:347597. doi: 10.1100/2012/347597

Adamson, A. L., Wright, N., and LaJeunesse, D. R. (2005). Modeling early Epstein-Barr virus infection in Drosophila melanogaster: the BZLF1 protein. Genetics 171, 1125–1135. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.042572

Baenas, N., and Wagner, A. E. (2019). Drosophila melanogaster as an alternative model organism in nutrigenomics. Genes Nutr. 14:14. doi: 10.1186/s12263-019-0641-y

Chen, S., Huang, J., Chen, J., Liu, F., Wang, S., Wang, N., et al. (2025). Mpox virus: virology, molecular epidemiology, and global public health challenges. Front. Microbiol. 16:1624110. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1624110

Damon, I. K. (2011). Status of human monkeypox: clinical disease, epidemiology and research. Vaccine. 29, D54–D59. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.014

Deng, Y., Navarro-Forero, S., and Yang, Z. (2025). Temporal expression classes and functions of vaccinia virus and mpox (monkeypox) virus genes. Mbio 16:e03809–24. doi: 10.1128/mbio.03809-24

Di Giulio, D. B., and Eckburg, P. B. (2004). Human monkeypox: an emerging zoonosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4, 15–25. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00856-9

Ding, S-. W., and Voinnet, O. (2007). Antiviral immunity directed by small RNAs. Cell 130, 413–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.039

European Union (2010). Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Off. J. Eur. Union 276, 33–79.

Fang, D., Liu, Y., Dou, D., and Su, B. (2024). The unique immune evasion mechanisms of the mpox virus and their implication for developing new vaccines and immunotherapies. Virol. Sin. 39, 709–718. doi: 10.1016/j.virs.2024.08.008

Ghosh, N., Chacko, L., Vallamkondu, J., Banerjee, T., Sarkar, C., Singh, B., et al Clinical strategies therapeutics for human monkeypox virus: a revised perspective on recent outbreaks. Viruses (2023) 15:1533. doi: 10.3390/v15071533.

Giansanti, M. G., Frappaolo, A., and Piergentili, R. (2025). Drosophila melanogaster: how and why it became a model organism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26:7485. doi: 10.3390/ijms26157485

Hermez, J., El Helou, R., Sawaya, T., Sader, G., Jamil, M. S., Alaama, A. S., et al. (2024). Emergence of mpox in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: data assessment and implications for a public health response. J. Infect. Public Health. 17:102565. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2024.102565

Hopkins, K. C., McLane, L. M., Maqbool, T., Panda, D., Gordesky-Gold, B., Cherry, S. A., et al. (2013). Genome-wide RNAi screen reveals that mRNA decapping restricts bunyaviral replication by limiting the pools of Dcp2-accessible targets for cap-snatching. Genes Dev. 27, 1511–1525. doi: 10.1101/gad.215384.113

Hu, Y., Flockhart, I., Vinayagam, A., Bergwitz, C., Berger, B., Perrimon, N., et al. (2011). An integrative approach to ortholog prediction for disease-focused and other functional studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 12:357. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-357

Hughes, T. T., Allen, A. L., Bardin, J. E., Christian, M. N., Daimon, K., Dozier, K. D., et al. (2012). Drosophila as a genetic model for studying pathogenic human viruses. Virology 423, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.11.016

Hylander, B. L., Repasky, E. A., and Sexton, S. (2022). Using mice to model human disease: understanding the roles of baseline housing-induced and experimentally imposed stresses in animal welfare and experimental reproducibility. Animals 12:371. doi: 10.3390/ani12030371

Kotadia, S., Kao, L. R., Comerford, S. A., Jones, R. T., Hammer, R. E., Megraw, T. L., et al. (2008). PP2A-dependent disruption of centrosome replication and cytoskeleton organization in Drosophila by SV40 small tumor antigen. Oncogene 27, 6334–6346. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.254

Likos, A. M., Sammons, S. A., Olson, V. A., Frace, A. M., and Li, Y. Olsen-Rasmussen M. A tale of two clades: monkeypox viruses. J Gen Virol. (2005) 86(Pt 10):2661–2672. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81215-0.

Link, N., Harnish, J. M., Hull, B., Gibson, S., Dietze, M., Mgbike, U. E., et al. (2024). A Zika virus protein expression screen in Drosophila to investigate targeted host pathways during development. Dis Model Mech. 17. doi: 10.1242/dmm.050297

Lum, F-. M., Torres-Ruesta, A., Tay, M. Z., Lin, R. T., Lye, D. C., Rénia, L., et al. (2022). Monkeypox: disease epidemiology, host immunity and clinical interventions. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 597–613. doi: 10.1038/s41577-022-00775-4

Marchal, C., Vinatier, G., Sanial, M., Plessis, A., Pret, A. M., Limbourg-Bouchon, B., et al. (2012). The HIV-1 Vpu protein induces apoptosis in Drosophila via activation of JNK signaling. PLoS ONE. 7:e34310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034310

Mascolo, E., Liguori, F., Merigliano, C., Schiano, L., Gnocchini, E., Pilesi, E., et al. (2022). Vitamin B6 rescues insulin resistance and glucose-induced DNA damage caused by reduced activity of Drosophila PI3K. J. Cell. Physiol. 237, 3578–3586. doi: 10.1002/jcp.30812

Meltzer, H., Marom, E., Alyagor, I., Mayseless, O., Berkun, V., Segal-Gilboa, N., et al. (2019). Tissue-specific (ts)CRISPR as an efficient strategy for in vivo screening in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 10:2113. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10140-0

Moser, T. S., Sabin, L. R., and Cherry, S. (2010). RNAi screening for host factors involved in vaccinia virus infection using Drosophila cells. J Vis Exp. 25:2137. doi: 10.3791/2137-v

NC3Rs (n.d.). What are the 3Rs? Available online at: https://nc3rs.org.uk/who-we-are/3rs (Accessed October 31, 2025).

Ogunleye, S. C., Akinsulie, O. C., Aborode, A. T., Olorunshola, M. M., Gbore, D., Oladoye, M., et al. (2023). The re-emergence and transmission of Monkeypox virus in Nigeria: the role of one health. Front. Public Health. 11:1334238. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1334238

Park, E. M., Park, S. W., Lee, Y. J., Lee, W. J., and Choi, W. (2018). Production of Ebola virus-like particles in Drosophila melanogaster Schneider 2 cells. J. Virol. Methods 261, 156–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2018.08.016

Pastorino, P., Prearo, M., and Barceló, D. (2024). Ethical principles and scientific advancements: in vitro, in silico, and non-vertebrate animal approaches for a green ecotoxicology. Green Anal. Chem. 8. doi: 10.1016/j.greeac.2024.100096

Pilatti, L., Mancini Astray, R., Rocca, M. P., Barbosa, F. F., Jorge, S. A. C., Butler, M., et al. (2020). Purification of rabies virus glycoprotein produced in Drosophila melanogaster S2 cells: an efficient immunoaffinity method. Biotechnol. Prog. 36:e3046. doi: 10.1002/btpr.3046

Prescott, M. J., Clark, C., Dowling, W. E., and Shurtleff, A. C. (2021). Opportunities for refinement of non-human primate vaccine studies. Vaccines 9:284. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030284

Qiao, H. H., Wang, F., Xu, R. G., Sun, J., Zhu, R., Mao, D., et al. (2018). An efficient and multiple target transgenic RNAi technique with low toxicity in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 9:4160. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06537-y

Querenet, M., Danjoy, M. L., Mollereau, B., and Davoust, N. (2015). Expression of dengue virus NS3 protein in Drosophila alters its susceptibility to infection. Fly 9, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/19336934.2015.1072662

Satheshkumar, P. S., Gigante, C. M., Mbala-Kingebeni, P., Nakazawa, Y., Anderson, M., Balinandi, S., et al. (2025). Emergence of Clade Ib monkeypox virus-current state of evidence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 31, 1516–1525. doi: 10.3201/eid3108.241551

Sessions, O. M., Barrows, N. J., Souza-Neto, J. A., Robinson, T. J., Hershey, C. L., Rodgers, M. A., et al. (2009). Discovery of insect and human dengue virus host factors. Nature 458, 1047–1050. doi: 10.1038/nature07967

Shchelkunov, S., Totmenin, A., Safronov, P., Mikheev, M., Gutorov, V., Ryazankina, O., et al. (2002). Analysis of the monkeypox virus genome. Virology. 297, 172–194. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1446

Shchelkunov, S. N., Totmenin, A. V., Babkin, I. V., Safronov, P. F., Ryazankina, O. I., Petrov, N. A., et al. (2001). Human monkeypox and smallpox viruses: genomic comparison. FEBS Lett. 509, 66–70. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03144-1

Srivastava, S., Sharma, D., Sridhar, S. B., Kumar, S., Rao, G., Budha, R. R., et al. (2025). Comparative analysis of Mpox clades: epidemiology, transmission dynamics, and detection strategies. BMC Infect. Dis. 25:1290. doi: 10.1186/s12879-025-11784-8

Steinberg, R., Shemer-Avni, Y., Adler, N., and Neuman-Silberberg, S. (2008). Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early-gene expression disrupts embryogenesis in transgenic Drosophila. Transgenic Res. 17, 105–119. doi: 10.1007/s11248-007-9136-5

Valanne, S., Wang, J-. H., and Rämet, M. (2011). The Drosophila toll signaling pathway. J. Immunol. 186, 649–656. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002302

Victor Atoki, A., Aja, P. M., Shinkafi, T. S., Ondari, E. N., Adeniyi, A. I., Fasogbon, I. V., et al. (2025). Exploring the versatility of Drosophila melanogaster as a model organism in biomedical research: a comprehensive review. Fly 19:2420453. doi: 10.1080/19336934.2024.2420453

Wang, Y., Zhang, J., Li, M., Jia, M., Yang, L., Wang, T., et al. (2024). Transcriptome and proteomic analysis of mpox virus F3L-expressing cells. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 14:1354410. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1354410

Wei, Z. K., Zhao, Y. C., Wang, Z. D., Sui, L. Y., Zhao, Y. H., Liu, Q., et al. (2023). Animal models of mpox virus infection and disease. Infect Med. 2, 153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.imj.2023.05.004

Wenner, H. A., Macasaet, F. D., Kamitsuka, P. S., and Kidd, P. (1968). Monkey pox. I. Clinical, virologic and immunologic studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 87, 551–566. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120846

WHO (2025). Global Mpox Trends. Available online at: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/ (Accessed August 25, 2025).

Wong, S. L. A., Chen, Y., Chan, C. M., Chan, C. S. M., Chan, P. K. S., Chui, Y. L., et al. (2005). In vivo functional characterization of the SARS-Coronavirus 3a protein in Drosophila. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 337, 720–729. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.098

Yi, X. M., Lei, Y. L., Li, M., Zhong, L., and Li, S. (2024). The monkeypox virus-host interplays. Cell Insight 3:100185. doi: 10.1016/j.cellin.2024.100185

Zhang, S., Wang, F., Peng, Y., Gong, X., Fan, G., Lin, Y., et al. (2024). Evolutionary trajectory and characteristics of Mpox virus in 2023 based on a large-scale genomic surveillance in Shenzhen, China. Nat. Commun. 15:7452. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-51737-4

Zhang, X. B., Dong, W., Li, K. X., Wang, J. J., Shen, J., Moussian, B., et al. (2020). Flexible manipulation of Omb levels in the endogenous expression region of Drosophila wing by combinational overexpression and suppression strategy. Insect Sci. 27, 14–21. doi: 10.1111/1744-7917.12705

Zhu, J.-Y., Lee, J.-G., van de Leemput, J., Lee, H., and Han, Z. (2021). Functional analysis of SARS-CoV-2 proteins in Drosophila identifies Orf6-induced pathogenic effects with Selinexor as an effective treatment. Cell Biosci. 11:59. doi: 10.1186/s13578-021-00567-8

Zirin, J., Bosch, J., Viswanatha, R., Mohr, S. E., and Perrimon, N. (2022). State-of-the-art CRISPR for in vivo and cell-based studies in Drosophila. Trends Genet. 38, 437–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2021.11.006

Keywords: fruit fly, host-pathogen interaction, disease model, monkeypox virus, antiviral drug screening

Citation: Mudjahid M, Frediansyah A, Ophinni Y and Nainu F (2025) Drosophila melanogaster as a prospective model organism for monkeypox virus research. Front. Microbiol. 16:1696236. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1696236

Received: 31 August 2025; Revised: 12 November 2025;

Accepted: 21 November 2025; Published: 16 December 2025.

Edited by:

Lingbao Kong, Jiangxi Agricultural University, ChinaReviewed by:

Rustem Ilyasov, Russian Academy of Sciences, RussiaCopyright © 2025 Mudjahid, Frediansyah, Ophinni and Nainu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Youdiil Ophinni, eW9waGlubmlAY3NlYXMua3lvdG8tdS5hYy5qcA==; Firzan Nainu, ZmlyemFubmFpbnVAdW5oYXMuYWMuaWQ=

Mukarram Mudjahid

Mukarram Mudjahid Andri Frediansyah

Andri Frediansyah Youdiil Ophinni

Youdiil Ophinni Firzan Nainu

Firzan Nainu