- 1School of Public Health, Shantou University, Shantou, China

- 2School of Basic Medicine and Public Health, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

- 3Shantou Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Institute, Shantou, China

- 4State Key Laboratory for Zoonotic Diseases, Key Laboratory for Zoonosis Research of the Ministry of Education, Institute of Zoonosis, and College of Veterinary Medicine, Jilin University, Changchun, China

Background: The situation of drug-resistant tuberculosis in China remains serious and complex. The majority of the study data are still derived from the 2,207 national survey of drug-resistant tuberculosis. In this study, we aimed to comprehensively characterize the prevalence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) in China and update the catalogue of drug-resistant mutations while accounting for geographic variability.

Materials and methods: This study analyzed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) isolates collected from 27 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions across China. All strains were analyzed for resistance to isoniazid, rifampicin, streptomycin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and quinolones based on the results of phenotypic drug sensitivity tests. The spatial and temporal distribution characteristics of drug-resistant strains were assessed based on the geographic origin and collection time of the isolates. The association between mutations and drug resistance was evaluated using mutation rates, positive predictive values, chi-square or Fisher’s exact test p-values, and 95% confidence intervals.

Results: 55,388 MTB strains collected from 2002 to 2024 were analyzed, among which 15,078 were drug-resistant, including 7,848 multidrug-resistant strains. The resistance rates for INH, RFP, SM, EMB, PZA, and QS were 27.67, 25.33, 11.55, 6.19, 8.63, and 20.63%, respectively. Regional distribution patterns revealed that the eastern and western regions had the highest number of strains, but relatively low resistance rates. There was a low inflection point in 2019 for the resistance rates of all drugs except INH, whose resistance rate continued to increase after 2017. A total of 754 non-synonymous mutations were identified, with the highest mutation rates observed in INH (32.91%), RIF (28.98%), and QS (14.47%). The dominant mutation sites were katG (315AGC → ACC), rpoB (531TCG → TTG), and gyrA (94GAC → GGC), respectively. In addition, 96 newly detected mutations potentially associated with drug resistance were identified, including ahpC (11CCG → CCG) and pncA (226ACT → CCT). Combined mutations were most frequently observed in rpoB + rpoB, katG + katG, and katG + inhA, with other double-mutation combinations also being predominant.

Conclusion: Our analysis demonstrates that drug-resistant tuberculosis remains a serious challenge in China. Newly identified resistance-conferring mutations should be prioritized and integrated with the specific epidemiological characteristics of DR-TB in China to support the development and implementation of rapid diagnostic technologies.

1 Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) is the pathogen responsible for tuberculosis (TB). The World Health Organization (WHO) aims to eliminate the global tuberculosis epidemic by 2035. However, the emergence of drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) has posed even greater challenges to resource-poor, high TB-burden countries due to its prolonged treatment duration, significant drug side effects, and increased risk of death (World Health Organization, 2024; Treatment Action Group, Stop TB Partnership, 2025). China currently faces a severe burden of DR-TB. In 2023, the number of new multidrug-resistant/rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (MDR/RR-TB) cases ranked fourth globally, accounting for 7.3% of the global total (World Health Organization, 2024). Additionally, due to disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 (WHO, 2025), the epidemiological trends of DR-TB in China have become more complex. To accurately guide tuberculosis prevention and control efforts and narrow the gap between the detection and treatment of drug-resistant cases, it is essential to update the epidemiological characteristics of MTB in a timely manner (Wan et al., 2020; Mohamed et al., 2021). This involves investigating whether current research can identify genes or loci with potential as drug-resistant targets, thereby deepening our understanding of the regional distribution patterns of drug-resistant tuberculosis.

Phenotypic drug susceptibility testing (DST) remains the gold standard for detecting drug resistance in MTB. However, such methods are cumbersome and time-consuming (7–56 days) and require expensive and complex laboratory capabilities, making them difficult to implement and apply in countries with a high burden of DR-TB (Bwanga et al., 2009). The WHO recommends the use of rapid molecular tests or sequencing technologies for drug resistance testing of MTB (World Health Organization, 2022). For example, nucleic acid-based molecular diagnostic techniques, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), whole-genome sequencing (WGS), and GeneXpert, have significantly simplified and accelerated the diagnosis of DR-TB (Shinnick et al., 2015; Boehme et al., 2010). However, the sensitivity and specificity of these methods may vary depending on the region of use (Ferro et al., 2013). Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the epidemiological characteristics of drug-resistant MTB and the genes associated with drug resistance in a particular region is crucial for overcoming regional limitations in drug resistance.

Acquired antibiotic resistance in MTB is primarily characterized by mutations in genes encoding drug targets or drug-activating enzymes. This enables bacteria to survive under external pressures such as drug exposure, thereby leading to DR-TB (Wan et al., 2020; Gygli et al., 2017). In 2021, the WHO compiled a catalog of resistance-associated mutations to serve as a global standard for interpreting molecular data to predict drug resistance (Walker et al., 2022). For instance, mutations in katG (particularly at codon 315) and the inhA promoter region (e.g., at position −15) are strongly associated with resistance to isoniazid (INH) (Liu, 2024; Ando et al., 2014). The Rifampicin (RIF) resistance-determining region (RRDR) is widely used to identify rifampicin-resistant strains (Unissa et al., 2016). Resistance to Quinolones (QS) often involves mutations in gyrA and gyrB (Kocagöz et al., 1996), while Streptomycin (SM) resistance is commonly linked to mutations in rpsL and rrs (Maningi et al., 2018). The embB306 is the primary mutation site in ethambutol-resistant (EMB) MTB (Mokrousov et al., 2002). Additionally, unlike the relatively concentrated resistance genes and sites mentioned above, pyrazinamide resistance (PZA) can be caused by many individually infrequent mutations dispersed across pncA (Köser et al., 2020). However, due to specific issues such as social pressure and disease burden in different countries, complex or additional resistance mutations may arise (Pei et al., 2024), so the specific situation in China requires further detailed analysis.

Currently, the most recent strain data for analyzing the drug resistance epidemiology of tuberculosis in China still originate from the 2007 National Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Survey (Zhao et al., 2012). Such nationwide surveys are typically targeted, and regions experiencing economic growth may receive more opportunities for reporting. Additionally, in recent years, factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic and antibiotic misuse have slowed the previously declining trend of tuberculosis incidence in China, further contributing to a complex drug resistance landscape (Liu et al., 2022). Therefore, this study systematically analyzed clinical MTB strains isolated from various regions across China over the past two decades. The analysis encompassed not only strains from nationally designated sentinel sites but also incorporated data from spontaneously conducted regional DR-TB surveys at the prefectural level. It obtained and integrated the drug resistance profiles and mutation patterns of drug resistance-associated genes from these strains. This study provides scientific reference for updating the epidemiological status of drug-resistant tuberculosis in China, broadening the scope of regional drug-resistant tuberculosis investigations, and exploring the mutation characteristics of drug-resistant genes. It aims to advance the optimization of precision control strategies for drug-resistant tuberculosis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Data sources

As of September 1, 2024, we collected data on drug resistance in MTB in China from eligible studies retrieved from PubMed, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Data, and VIP Database (Supplementary Table 1). Studies were included if the strains in the literature originated from China, and the results must include DST resistance results, molecular detection resistance results, resistance gene mutation types, and mutation site information. Studies were excluded if they did not perform DST or lacked information on resistance gene mutations, or if multiple publications described the same sample set—in such cases, the study with the largest sample size or the most recent publication date was selected.

2.2 Definitions related to drug resistance

INHR, RIFR, SMR, QSR, PZAR, and EMBR are defined as MTB resistant to INH, RIF, SM, QS, PZA, and EMB, respectively. INHS, RIFS, SMS, QSS, PZAS, and EMBS are defined as MTB sensitive to INH, RIF, SM, QS, PZA, and EMB, respectively. DR-TB is defined as tuberculosis caused by MTB resistant to one or more anti-tuberculosis drugs. MDR-TB is defined as tuberculosis resistant to at least two first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs, INH and RIF (World Health Organization, 2022). To mitigate potential bias in drug resistance data arising from heterogeneous detection strategies, this study categorizes references into single-drug detection studies (S strategy) and multi-drug detection studies (M strategy) based on detection approach. A single-drug detection study is defined as one where only one target drug is present and detected, such as assessing resistance to either RFP or INH alone. Multi-drug detection studies are defined as those where two or more target drugs are present, such as detecting resistance to both RFP and INH or to multiple drugs including RFP, INH, and SM.

2.3 Identifying drug resistance-associated gene mutations in bacterial strains

This study integrated the first and second editions of the WHO-published catalogues of drug-resistant-associated gene mutations in MTB and the pulmonary tuberculosis drug resistance database to identify a set of candidate genes and corresponding promoter sequences with a higher likelihood of being associated with drug resistance for each drug (Supplementary Table 7) (Walker et al., 2022; Sandgren et al., 2009; World Health Organization, 2023). Tier 1 indicates association with drug resistance; Tier 2 indicates association with intermediate drug resistance. After extracting all drug resistance data from the included literature, we first identified synonymous mutations that do not confer drug resistance, followed by mutations potentially associated with drug resistance (including single mutations and combined mutations). The phenotypic and molecular drug resistance identification results were compared to determine the association between each gene or region and drug resistance.

2.4 Criteria for determining drug resistance-associated mutations

Based on the standards established by Köser et al. (2020), using ORs, PPVs, p-values, and CIs as reference points, a mutation is considered to be associated with resistance if it is observed on at least five occasions, the lower bound of the 95% CI for PPV is at least 0.25, the OR is at least 1, and the p-value is significant. If the variant occurs only in susceptible isolates or appears solely in susceptible isolates, it is considered unrelated to resistance. If the mutation never occurred alone in susceptible isolates and was not exclusive to susceptible isolates, it was rated as of uncertain significance. Since PZA resistance arises from multiple rare mutations scattered across pncA, criteria were relaxed for pyrazinamide to avoid excessive exclusion of these mutations. A mutation is classified as associated with resistance if it occurs in at least two resistant isolates in pncA with a PPV of at least 50%. In contrast, mutations with a PPV below 40% (and an upper 95% CI below 75%) are classified as unrelated to resistance. Furthermore, to distinguish statistically significant resistance genes by importance, we defined high-confidence mutations as those explicitly documented in public databases (such as WHO-UCN-TB and PhyResSE) or confirmed through at least one independent experimental study (e.g., gene knockout, complementation assays) as being associated with drug resistance. All other newly identified mutations are classified as low-confidence mutations, requiring additional validation through bioinformatics techniques to establish their association with drug resistance.

2.5 Data processing and statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel 2024 was used for the organization and extraction of drug resistance-related information; R 4.5.1 was employed for data visualization and batch computation of odds ratios, positive predictive values, and confidence intervals. IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests according to the sample size, as well as multivariate regression analysis. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Basic information on included strains

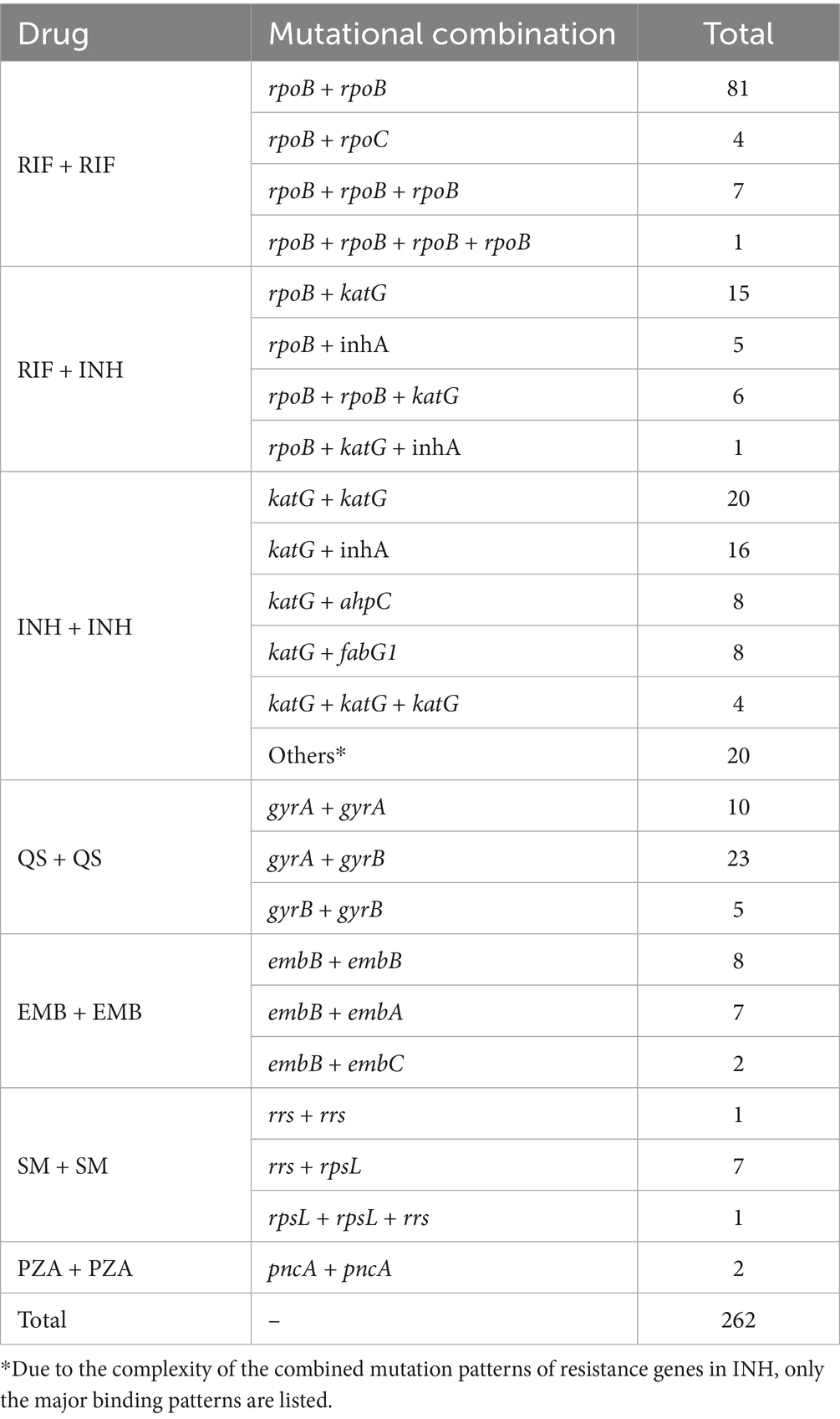

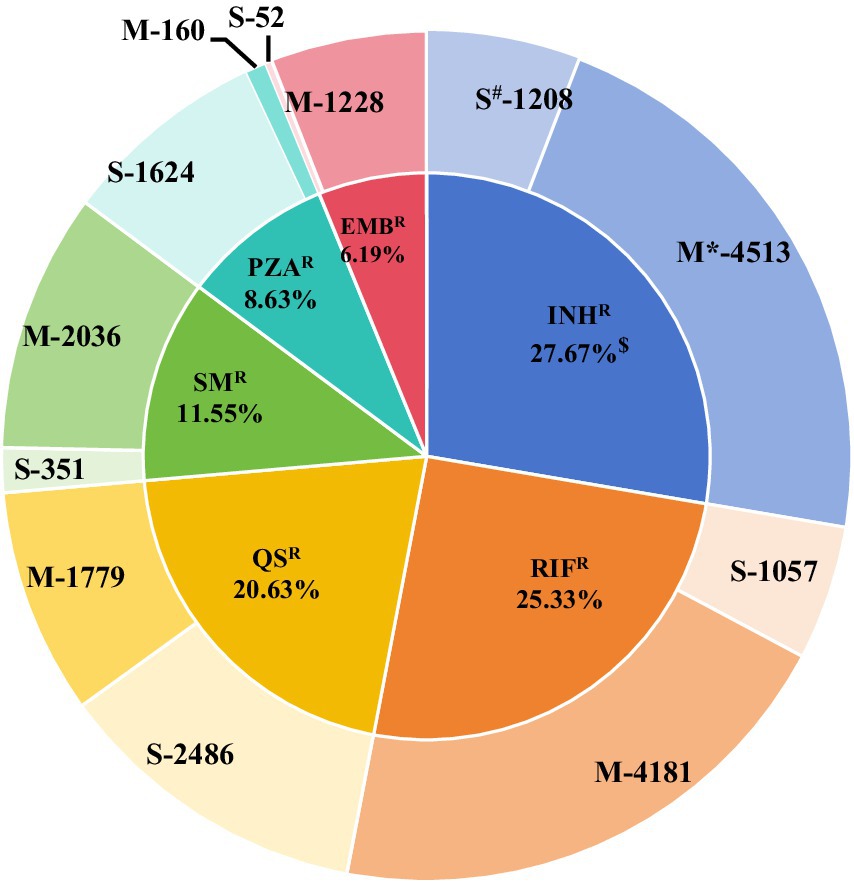

A total of 55,388 MTB collected between 2002 and 2024 were included in the final analysis. Among these, 18,781 (33.90%, 18,781/55,388) were tested using the S-strategy, while 36,607 (66.09%, 36,607/55,388) were tested via the M-strategy. Overall, 15,078 DR-TB strains were identified, including 7,848 MDR-TB strains, which accounted for 17.01% (7,848/46,138) of all isolates. Among the DR-TB strains, resistance to first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs—INHR(27.67%) and RFPR(25.33%) —and the second-line drug QSR(20.63%) was frequently observed. In contrast, SMR, PZAR, and EMBR occurred at relatively lower frequencies (Figure 1; Supplementary Table 8).

Figure 1. Distribution of 15,078 resistant strains. * Group M indicates the frequency of resistant strains obtained through the M-strategy test. # Group S indicates the frequency of resistant strains obtained through the S-strategy. $ Frequency of drug resistance = frequency of drug resistance/total frequency of drug resistance. Here, the total frequency of occurrence of drug resistance in the 15,078 resistant strains is 20,675.

3.2 Regional distribution characteristics of DR-TB strains

A total of 55,388 MTB strains were collected from 21 provinces, 4 municipalities, and 2 autonomous regions across China (Supplementary Table 2). According to China’s economic regional classification, the distribution of strain origins, in descending order, was as follows: the Eastern region (39,453), the Western region (9,992), the Central region (4,408), and the Northeastern region (1,360). The drug resistance rates, ranked from highest to lowest, were as follows: Northeastern region (74.49%), Central region (38.36%), Western region (36.95%), and Eastern region (21.69%) (Table 1). The national distribution and geographical origins of the collected strains are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Geographical distribution of the included MTB isolates in China. Strains without precisely defined geographical origins within China were excluded from the analysis.

3.3 Temporal distribution characteristics of drug-resistant strains

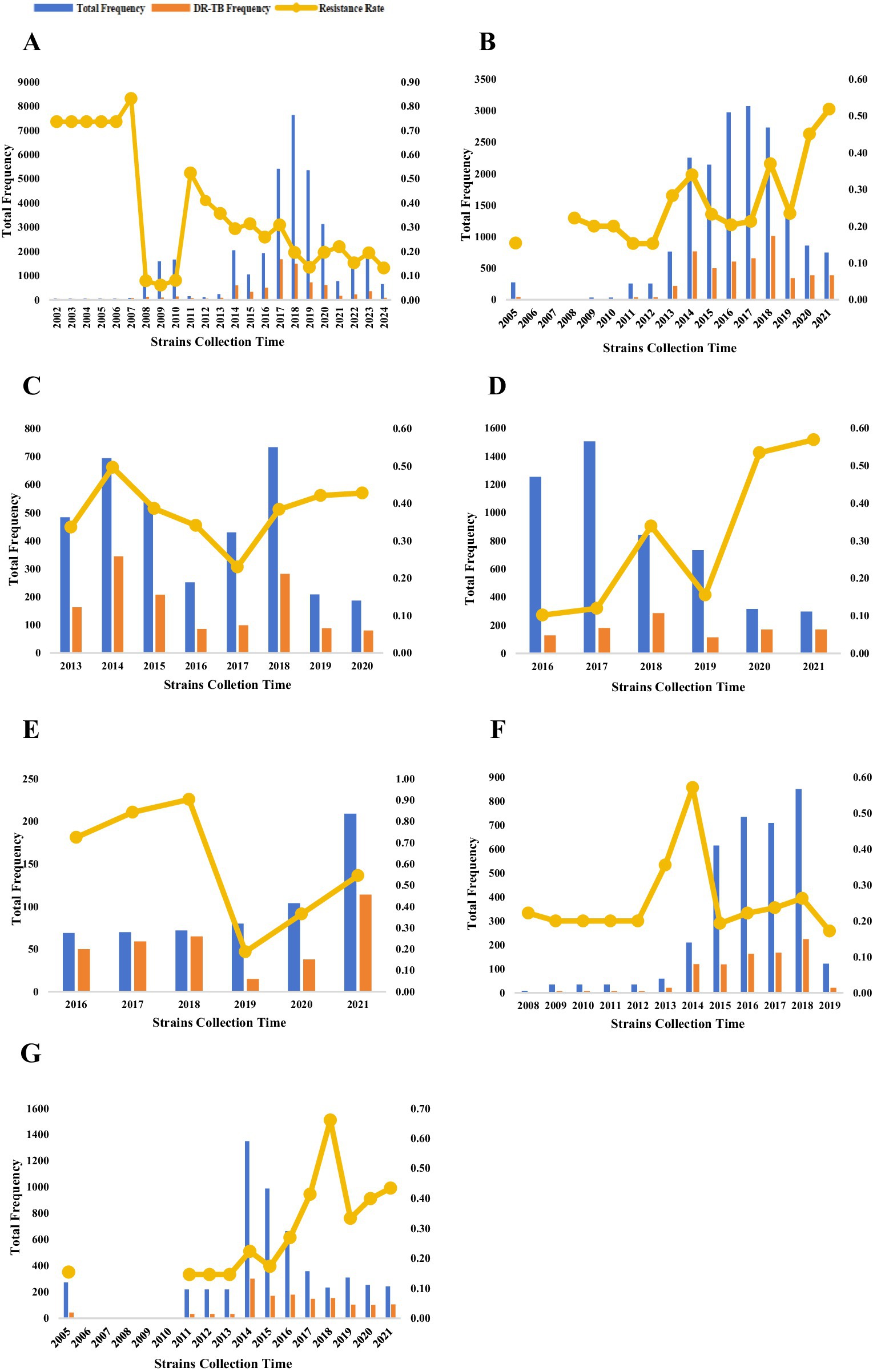

MTB strains included in this study via the M-strategy were collected between 2002 and 2024 (Supplementary Table 3). The number of MTB isolates generally showed an increasing trend until 2019, after which a decline was observed. Concurrently, although the overall drug resistance rate exhibited a downward trend, transient upward inflection points were noted in 2014, 2016, 2019, and 2022 (Figure 3A). Strains included via the S-strategy were collected over varying time periods (Supplementary Table 3). The collection of MTB isolates was primarily concentrated between 2014 and 2018, with a substantial decrease in the number of strains collected after 2019 (inclusive). Furthermore, compared to the results from the M-strategy, the drug resistance rate remained relatively high (20%–50%) for most of the period and gradually increased to its peak following the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 (Figure 3B). Furthermore, a temporal analysis of individual anti-tuberculosis drugs based on the S-strategy revealed that the number of MTB isolates for INH, RIF, and QS agents with higher resistance rates gradually decreased after the peak period. In contrast, the number of isolates for SM, which had a lower resistance rate, showed a gradual increase. With the exception of INH, the resistance rates for RIF, QS, SM, and PZA all reached high-value inflection points in 2018, followed by low-value inflection points in 2019 (Figures 3C–G).

Figure 3. Temporal distribution of MTB strains included in the analysis (A–G). The temporal distribution of MTB strains included in the analyses (continued). The temporal distribution of MTB strains detected by the M-strategy (A), the temporal distribution of all MTB strains detected by the S-strategy (B), and the temporal distribution of MTB strains detected by the S-strategy for INHR, RIFR, SMR, PZAR, and QSR (C–G). Temporal analyses were not performed because of the severe underrepresentation of MTB strains detected by the S-strategy for EMBR.

3.4 Synonymous mutations in candidate drug-resistance genes

A total of 79 synonymous type mutations were identified in 13 candidate genes and regions in this study (Supplementary Table 4). Although it is generally accepted that synonymous mutations are not associated with MTB resistance, we found that of the 79 synonymous mutations, 60.76% (48/79) occurred only in resistant strains, 34.18% (27/79) occurred only in sensitive strains, and the remaining four mutations occurred in both resistant and sensitive strains. Among the 13 candidate genes and regions carrying synonymous mutations, rpsA exhibited the highest mutation frequency (39.69%). Furthermore, the rpsA 636 CGA → CGC (Arg → Arg) mutation occurred at a higher frequency in PZAR strains than in PZAS strains, with a PPV as high as 66.02% (95% CI: 56.03–75.06%). None of the known synonymous mutations in katG, rpoB, ahpC, ndh, kasA, gyrA, gyrB, pncA, or rpsA independently occurred in the corresponding DR-TB strains. In contrast, six independent mutations in inhA, rrs, and rpsL were found exclusively in inhA-resistant, rrs-resistant, and rpsL-resistant strains, respectively. Additionally, the candidate gene rpoB—typically associated with RIFR—exhibited a 1,075 GCT → GCC (Ala→Ala) mutation in both INHR and INHS strains, with a higher frequency observed in INHR strains. Further integration of mutation information from the original strains carrying these synonymous mutations revealed that mutations at katG 440, 375, 295, 582, ndh 226, 107, kasA 139, and gyrB 428 did not occur independently but were instead accompanied by concurrent mutations at other sites or in other genes.

3.5 Characterization of mutations in candidate drug-resistance genes in MTB strains

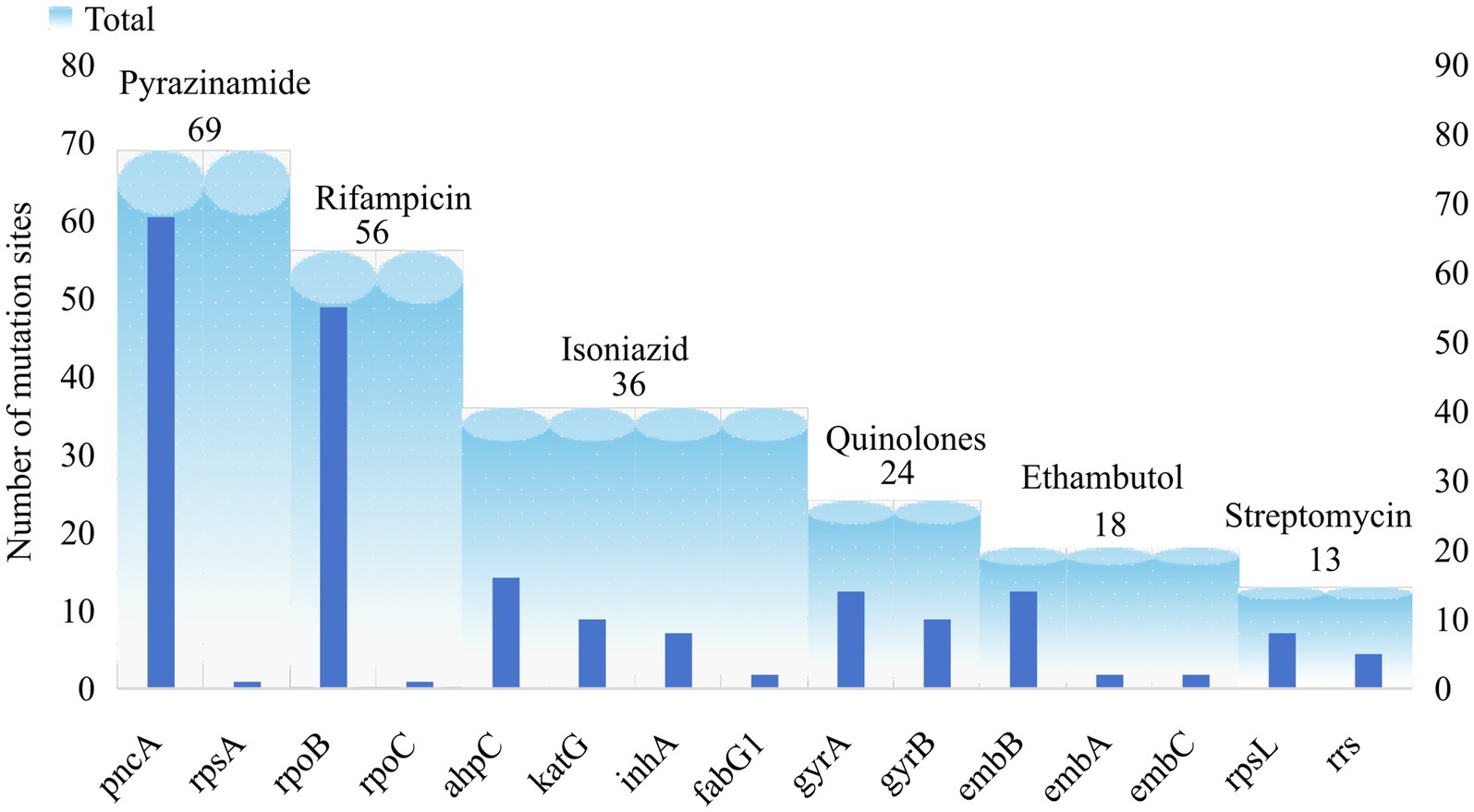

The catalogue of drug resistance gene mutations in MTB strains included in this study is shown in Supplementary Table 5. A total of 740 gene mutations were identified across 55,388 MTB strains, with point mutations being the predominant type. Based on the criteria for determining the association between gene mutations and drug resistance, 216 (29.19%) of the 740 mutations were found to be associated with drug resistance. With the exception of the candidate gene kasA, all other candidate genes exhibited mutations linked to drug resistance. Following comparison with public databases and validation experiments, we have identified 101 high-confidence mutations, which are highlighted in Supplementary Table 5. It should be noted, however, that this does not imply other novel mutations are insignificant; rather, further biological evidence is required to validate the association of these site mutations with drug resistance. Among these, 69 mutations in the candidate genes pncA and rpsA were associated with pyrazinamide resistance (PZAR), 56 mutations in rpoB and rpoC were associated with rifampicin resistance (RIFR), and 36 mutations in ahpC, katG, inhA, and fabG1 were associated with isoniazid resistance (INHR). The number of mutation sites in the remaining candidate genes is shown in Figure 4.

A total of 216 candidate mutations associated with drug resistance were identified with an overall mutation rate of 98.51%. Among these, mutations related to PZAR as defined by relaxed criteria accounted for 2.64%, while the remaining candidate genes accounted for 95.87% (Supplementary Table 5). Although the candidate genes associated with PZAR exhibited the highest number of mutated sites, these mutations were scattered across the genome. The predominant mutations included 226ACT → CCT, 395GGT → GCT, and 29CAG → CCG, all of which were exclusively detected in PZAR strains. For INHR, mutations were primarily identified in katG, inhA, and ahpC. In katG, the main mutations were 315AGC → ACC and 463CGG → CTG; in inhA, the predominant mutation was -15C → T; and in ahpC, the primary mutation observed was 11CCG → CCG. Regarding RIFR, the rpoB gene primarily exhibited the 531TCG → TTG mutation. For QSR, the main mutations occurred in gyrA at codon 94 GAC → GGC and in gyrB at codon 499AAC → AAG. In relation to EMBR, the embB gene mainly harbored the 306ATG → GTG mutation. For SMR, the most frequent mutation was 43AAG → AGG in rpsL, while mutations in rrs were predominantly 514A → C and 1401A → G. The major mutation sites in each candidate gene are summarized in Table 2.

We further compared the mutation profile of drug resistance genes identified through our analysis with the catalogue published by the World Health Organization (hereinafter referred to as the WHO catalogue). Among the 215 candidate mutation sites, 121 were also documented in the WHO catalogue. Specifically, 32 mutation sites in our rpoB mutation profile were present in the WHO catalogue. For pncA, 26 mutation sites were recorded in the WHO catalogue. In contrast, only one synonymous mutation was documented in rpsA. Among the candidate genes associated with isoniazid resistance (INHR), katG and ahpC had 7 and 6 mutation sites listed in the WHO catalogue, respectively, whereas kasA was not included. The genes rpsA, rpoC, fabG1, embA, and rrs associated with drug resistance in our catalogue are all documented by the WHO (Figure 5). Given that the WHO catalogue is globally recognized as the authoritative reference for mutations related to tuberculosis drug resistance, the 96 mutation sites in our catalogue that the WHO did not document are considered novel mutations associated with drug resistance.

Figure 5. Number of candidate resistance genes associated with the WHO catalogue. rpsA, rpoC, fabG1, embA, and rrs all appear in the WHO catalogue, so there is only one dataset.

3.6 Combination of drug resistance gene mutations

Current research findings indicate that drug resistance in many strains is not solely attributable to mutations in individual genes or loci but rather results from combined mutations involving multiple genes or sites. In this study, a total of 262 instances of combined mutations were identified, primarily involving mutations within different genes conferring resistance to the same drug or at different sites within the same gene (Supplementary Table 6). Among combined mutations associated with the same drug, those involving RIF and INH were the most frequent. For RIF, the predominant pattern consisted of rpoB + rpoB combined mutations. INH exhibited diverse mutational combinations, mainly comprising katG + katG and katG + inhA. Regarding mutations across different drugs, combined mutations were only observed between RIF and INH, primarily in the forms of rpoB + katG and rpoB + inhA. Although a substantial number of pncA mutations were identified in this study, only two combined mutations involving this gene were detected. Furthermore, combined mutations across three or four sites—such as rpoB + katG + inhA and katG + inhA + ahpC + ndh—were also identified in some resistant strains. The patterns of combined mutations among drug resistance genes are summarized in Table 3. Subsequently, we further analyzed several mutation sites in rpoB and katG and found that the PPV increased when combined mutations occurred compared to single-site mutations. The PPV for the rpoB 516 site increased from 93.75 to 95.18%, while that for the rpoB 430 site rose from 47.95 to 89.06%. For katG 463, the PPV increased from 59.30 to 68.20%. Additionally, combined mutations in different candidate genes associated with isoniazid resistance (INHR), such as katG + inhA and katG + ahpC + fabG1, increased the PPV from 92.83 to 94.84 and 93.41%, respectively (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Positive predictive value of combined mutations in rpoB and katG for diagnosing RIFR and INHR.

4 Discussion

This study provides an updated overview of the current status of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis in China. For the first time, a comprehensive analysis was conducted on drug resistance and genetic mutation profiles of 55,388 clinical MTB isolates collected from 27 regions across China, including 7,848 MDR-TB strains. Our study examined regional and temporal distribution patterns of these strains, and the results reveal a serious situation of drug-resistant tuberculosis in China, characterized by complex and diverse resistance profiles. Furthermore, we identified multiple novel mutation sites in candidate genes that are potentially associated with drug resistance but have not been previously documented by the WHO. Therefore, there is an urgent need in China to further investigate the mechanisms of drug resistance, rationally apply molecular detection technologies, and develop new anti-tuberculosis drugs that target novel mechanisms or unexplored pathways to address the increasingly complex landscape of drug resistance.

The 55,388 MTB strains included in the study, spanning a 20-year period, may reflect the characteristics of TB drug resistance development in China. The overall strain resistance rate was 27.22%, which was slightly higher than the resistance rate of retreatment patients reported in the 2012 national survey (25.6%), but still lower than the resistance rates in high-burden regions such as India (58.4%) and Russia (32.5%) (World Health Organization, 2023; Lohiya et al., 2020; Ismail et al., 2018). Among all DR-TB strains, INH (27.67%) and RIF (25.33%), the first-line anti-TB drugs, had the highest resistance rates, which increased compared with the 2007 Chinese National Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Survey (Lohiya et al., 2020). Moreover, the resistance rates of EMB, SM, and PZA were 6.19, 11.55, and 8.63%, respectively. Notably, the resistance rate of PZA differed significantly from those of Thailand (49.0%) (Jonmalung et al., 2010) and Brazil (45.7%) (Bhuju et al., 2013). In addition, the resistance rate of second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs, especially QS, was higher than that of the first three and the results of the 2007 national survey (19.6%), but lower than the results of the Hameed et al. survey on resistance (73%) (Hameed et al., 2019). The observed differences in resistance rates indicate that the strategy of standardizing TB drug use has some positive effects. However, there are still problems, such as overuse of anti-tuberculosis drugs or unregulated treatment, as far as the current situation in China is concerned.

The MTB isolates in this study were obtained from multiple regions across China. Geographically, the highest number of isolates was collected from the eastern and western regions, which may be attributed to their relatively well-developed economic and healthcare infrastructure, facilitating more extensive strain surveillance and collection efforts. However, it is noteworthy that the drug resistance rates of MTB in these two regions were lower than those observed in the northeastern region. The drug resistance rate detected in the northeast exceeded both the nationally reported average and the levels documented in the survey by Wang et al. (2023). This phenomenon may be associated with historically irregular treatment practices and geographical differences in the prevalence of specific MTB genotypes, such as the Beijing genotype, which is potentially linked to higher drug resistance (Xu et al., 2017). The isolates included in this study cover a time span from 2002 to 2024. With the exception of INHR strains, a distinct turning point in resistance rates was observed for all other types of DR-TB strains in 2019. For instance, limited human and material resources, coupled with the social stigma attached to tuberculosis patients due to coughing as a symptom, may lead individuals to conceal their condition from others and delay seeking medical care. This situation has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, ultimately resulting in a reduction in the sources of bacterial strains (Bonadonna et al., 2017). According to data on drug-resistant strains acquired through the S-strategy, resistance rates to most anti-tuberculosis agents have shown an increasing trend in the past. Overall, however, the upward trajectory exhibited signs of moderation after the COVID-19 pandemic was brought under control, which aligns with global trends reported in the World Tuberculosis Report (World Health Organization, 2024). Considering both the geographical and temporal distribution characteristics of tuberculosis in China, we emphasize the need to further expand monitoring coverage, strengthen active screening, and accelerate the production and dissemination of national tuberculosis drug resistance surveillance reports. These steps are essential to providing timely and reliable data support for public health policy-making.

Compared to conventional DST, molecular detection methods based on pathogen nucleic acids, such as PCR amplification (Luo et al., 2019), whole-genome sequencing (WGS) (Wang et al., 2022), and line probe assays (Wang et al., 2021), offer improved prediction of drug resistance by leveraging limited known mutations and extensive catalogs of genetic variations (Wan et al., 2020). However, before investigating the association between genetic mutations and drug resistance, synonymous mutations and lineage-specific variations, such as gyrA Gly95Ala, which are recognized as unrelated to resistance, should be excluded (Siddiqi et al., 2002). In this study, we identified several synonymous mutations occurring exclusively in drug-resistant strains, including inhA 145 and rpoB 531, which we report here for the first time. Nevertheless, further strain identity information is required to determine whether these are linked to specific bacterial lineages. Among all synonymous mutations, the most frequently observed was rpsA 636 CGA → CGC, which is also documented in the WHO catalog. Notably, its PPV in our study (66.02%) was higher than that reported by the WHO (39.85%) (World Health Organization, 2023). Most of these strains were isolated from Henan Province, China, suggesting that the high frequency of this synonymous mutation in rpsA may be related to regional strain variations or other unknown factors. Additionally, the synonymous mutation rpoB 1,075 GCT → GCC was also frequently detected in DR-TB strains. Although lineage information for these strains was unavailable, our findings align with those reported by Wan et al. (2020) indicating that this mutation is closely associated with the Beijing genotype of MTB. The identification of synonymous mutations may contribute to a more accurate prediction of MTB drug resistance. Integrating such mutations with strain genotypic identity could provide further insights into the epidemiology of MTB.

Among the six anti-tuberculosis drugs in this study, INH and PZA are structurally simple. However, the resistance mechanisms are extremely complex, especially INH, which involves a wide variety of resistance genes with high mutation rates. Multiple previous studies have reported resistance genes associated with INH within biosynthetic networks and pathways (Unissa et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2019). katG, ahpC, inhA, and fabG1 mutations predominated in this study, with an overall mutation rate of 32.91%. Among strains with katG mutations, 93.03% were drug-resistant, a finding consistent with the results reported by Isakova et al. (2018) (91.2%). The predominant mutations in katG were 315AGC → ACC and 463CGG → CTG. However, the latter mutation was frequently observed in both resistant and susceptible strains, and existing evidence suggests that this mutation is more closely associated with the genetic lineage of the strain (Arjomandzadegan et al., 2011). Furthermore, this study newly identified ahpC 11CCG → CCG as a major mutation occurring exclusively in DR-TB strains, which differs from the predominant mutation at position −52 reported by Flores-Treviño et al. (2015). Previous studies have indicated that the mutation rate and specific loci of ahpC exhibit regional variations, with differing mutation frequencies observed even for the same locus across different provinces in China (Jagielski et al., 2015). Therefore, this locus could be considered a potential new target for investigating its correlation with INHR. To supplement the findings of Pei et al. (2024), who did not include an analysis of PZA-related loci, this study adopted broader criteria to investigate the characteristics of PZAR mutations in China. The results were consistent with previous reports (Tan et al., 2014), showing a high pncA mutation rate with widely dispersed mutation sites. In this study alone, 215 distinct mutation types were identified, primarily pncA 226ACT → CCT and 395GGT → GCT.

The chemical structures of RIF, EMB, SM, and QS are relatively complex. However, the candidate genes associated with drug resistance are predominantly concentrated in several hotspot loci where mutations frequently occur. The mutation rate for RIF was 28.98%, with mutations in DR-TB strains accounting for 97.03%—a figure higher than that reported by Yu et al. (2022) (90.00%). This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that Zeng et al. (2021) utilized WGS on strains from a single region. In contrast, the present study integrated results from multiple molecular detection methods, ultimately identifying a larger number of strains, which may have led to an elevated mutation rate. Consistent with previous findings, the primary mutation sites in rpoB in this study were at positions 531 (38.16%) and 526 (15.21%). Additionally, a novel mutation at 531TCG → TGG was identified. EMB occurs mainly with the embB306 mutation, in which the amino acid Met → Ile change exists in three mutation patterns: ATG → ATT, ATG → ATC, and ATG → ATA. Furthermore, embA and embC also encode arabinosyltransferases, thus contributing to EMBR (Khosravi et al., 2019). Examples include the embC 270ACC → ATC in conjunction with embB mutations, as well as embA C-12 T and C-16G occurring together with embB mutations. Among all mutated strains, the SM mutation rate was 10.07%, with DR-TB strains comprising 96.63% of these. The candidate genes for SM mutations were relatively stable and concentrated, primarily occurring in rpsL and rrs. Mutations in rpsL were mainly located at 43AAG → AGG and 88AAG → AGG, while those in rrs were concentrated at 514A → C and 1401A → G, consistent with both domestic and international studies (Chen et al., 2012; Smittipat et al., 2016). QS is a critical drug in the treatment of MDR-TB. In China, there is a high prevalence of pre-diagnostic exposure to QS among tuberculosis patients. In recent years, irregular usage and easy accessibility have contributed to a rising rate of QS resistance (Migliori et al., 2012). In this study, among strains with QS mutations, 98.34% were found to be drug-resistant. High-frequency mutations occurred mainly in gyrA and gyrB. Similar to the findings of Yin and Yu (2010), although most QSR strains carried mutations at position 94 of gyrA, the mutation patterns were diverse. The primary mutation observed was 94GAC → GGC, along with six other mutation patterns in the 94 locus. By monitoring the emergence and prevalence trends of these mutations within populations, it is possible to tailor individualized drug dosages based on molecular diagnostic results.

MTB strains often employ multi-locus combined mutation strategies, in addition to accumulating single-gene mutations, to enhance drug resistance levels or compensate for fitness costs under antimicrobial pressure (Dookie et al., 2018). For instance, in RIFR, co-occurring mutations at codons 533, 531, and 516 of the rpoB gene, along with other sites, significantly increase the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) (Nusrath Unissa et al., 2016). Concurrent mutations in rpoC and rpoB often exert compensatory or modifying effects on the phenotypes of rpoB mutations, further refining the resistance profile (Farhat et al., 2013). In the context of INHR, combined mutations involving the katG, inhA, and ahpC genes frequently lead to higher-level resistance (Jagielski et al., 2014). Studies indicate that MTB often acquires inhA mutations first, followed by katG mutations, or establishes INHR prior to developing RIFR, suggesting a close evolutionary linkage between these two resistance mechanisms. This pattern serves as an important molecular marker for diagnosing multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) (Li et al., 2019). This study demonstrates that RIF and INH co-mutations are the most prevalent. RIFR primarily involves multiple combined mutations within rpoB (e.g., 511 + 526, 516 + 533). Furthermore, all ahpC mutation sites identified in this study exhibited coupled mutations with rpoB at position 450. This phenomenon further corroborates the findings from the Russian population study, which showed that non-synonymous SNPs in rpoC are significantly more likely to occur in isolates harboring the rpoB mutation encoding p. Ser450Leu (Casali et al., 2014). INHR exhibits more complex mutational patterns, including various combinations such as katG + inhA, katG + ahpC, and ahpC + inhA. Among these, the present study identified a coupled mutation within the katG gene (CAG295CAA + AGC315ACC). Whilst the mutation at position 315 (AGC315ACC, resulting in Ser315Thr) aligns with previously reported coupled mutations in India (Ramasubban et al., 2011), the mutation at position 295 in this study is synonymous (CAG295CAA, Gln295Gln), whereas the Indian study reported a missense mutation (CAG295CAC, Gln295His). This indicates that the two strains underwent distinct genetic events at position 295. Furthermore, several novel mutation patterns were identified in this study, including pncA + pncA and rpsL + rpsL + rrs. Whether these mutations significantly contribute to high-level resistance requires further validation with MIC data. In conclusion, the emergence of collaborative mutations suggests that MTB is undergoing active adaptive evolution, aimed at enhancing drug resistance and conferring a survival advantage through multiple genetic alterations. This evolutionary strategy not only improves the strain’s drug tolerance but also substantially complicates the clinical management and control of DR-TB.

Based on the information of MTB strains obtained from TB-related studies conducted in various regions, this study specifically analyzed the current status of the DR-TB epidemic in China and updated the catalogue of mutations associated with drug resistance. In addition to the major mutations already documented by the WHO, we identified several novel genetic loci that may be associated with drug resistance, such as inhA239, ahpC11, and pncA226, which also exhibited relatively high frequencies among resistant strains (p < 0.05). However, to determine the correlation between these loci and drug resistance, we need more information on the drug sensitivity results (e.g., MIC) of these strains as well as relevant validation experiments. Notably, although several high-frequency mutation sites listed in the WHO catalog were also present in our dataset, their prevalence profiles differed. For instance, the mutation rate at ahpC-52 was lower than that at positions −48 and 11. This discrepancy may reflect the WHO’s global data aggregation approach, suggesting that China may harbor a distinct mutation spectrum for DR-TB. Furthermore, among all mutations compiled in this study, the proportion of DR-TB strains is likely overestimated. This bias may arise from the fact that DR-TB isolates are more frequently reported and thus more likely to be included in such analyses. The purposeful launch of TB surveys in various regions has led to the proactive collection of strains that are already drug-resistant in their own right, as seen in studies by Wu et al. (2019) and Sun et al. (2022), among others. At the same time, not all candidate genes were analyzed in this study due to the difficulty of analysis, and most efflux pump genes and enzymes related to carbon source metabolism (e.g., Rv1258c and pckA) were not included in the candidate genes, which may have led to the prediction that some isolates with mutations were missed. Finally, because many of the original studies did not report strain typing information, and if this had been used as an inclusion criterion, it would have drastically reduced the amount of data available. The present study, after careful consideration, failed to systematically analyze the association between Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain profiles and specific drug resistance mutations. However, in future studies, we will endeavor to fill this knowledge gap in order to gain a deeper understanding of the strain context in which drug resistance arises.

Despite these limitations, in-depth analyses based on continuously updated MTB drug resistance surveillance data can still enhance our understanding of epidemiological trends and the development of DR-TB in China, making it possible to advance toward achieving 100% coverage of TB molecular diagnostic techniques by 2027. Our analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains suggests that China should adopt complementary diagnostic strategies tailored to local drug-resistance patterns and introduce faster, more sensitive molecular detection technologies. For instance, nanopore sequencing technology (Carandang et al., 2025) offers notable advantages in terms of rapid testing and portability. Such technologies should be effectively integrated with conventional drug susceptibility testing and validated in subsequent studies. As functional validation evidence similar to that generated in this study continues to accumulate, mutations supported by robust evidence should be incorporated into routine reporting protocols to inform individualized treatment planning directly. With ongoing technological advancement and increasing methodological maturity, these approaches will provide critical support for diagnosing and treating drug-resistant tuberculosis, thereby helping to alleviate the burden of drug-resistant tuberculosis in China.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shantou University (approval number: STU202505006).

Author contributions

YX: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis. SL: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Visualization, Conceptualization. JZ: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Data curation. JL: Validation, Writing – review & editing. LG: Writing – review & editing, Validation. QC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the faculty of Shantou Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Institute for their advice and guidance in analysing all the data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1697490/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1 | Source of 55388 MTB strains included in this study.

Supplementary Table 2 | Regional distribution of strains included in this study.

Supplementary Table 3 | Temporal distribution of strains included in this study (which have been differentiated according to different detection strategies).

Supplementary Table 4 | Synonymous mutations occurring in candidate genes and intervals in this study.

Supplementary Table 5 | Catalogue of mutations in drug resistance genes of MTB strains in this study.

Supplementary Table 6 | Combined mutation profiles of different drug-resistant genes and intervals.

Supplementary Table 7 | The sixteen candidate genes and intergenic regions analyzed for association with resistance acquisition.

Supplementary Table 8 | Distribution of 15078 resistant strains obtained by different testing strategies.

References

Ando, H., Miyoshi-Akiyama, T., Watanabe, S., and Kirikae, T. (2014). A silent mutation in mabA confers isoniazid resistance on Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 91, 538–547. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12476,

Arjomandzadegan, M., Owlia, P., Ranjbar, R., Farazi, A. A., Sofian, M., Sadrnia, M., et al. (2011). Prevalence of mutations at codon 463 of katG gene in MDR and XDR clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Belarus and application of the method in rapid diagnosis. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 58, 51–63. doi: 10.1556/AMicr.58.2011.1.6,

Bhuju, S., Fonseca, L. S., Marsico, A. G., de Oliveira Vieira, G. B., Sobral, L. F., Stehr, M., et al. (2013). Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Rio de Janeiro reveal unusually low correlation between pyrazinamide resistance and mutations in the pncA gene. Infect. Genet. Evol. 19, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.06.008,

Boehme, C. C., Nabeta, P., Hillemann, D., Nicol, M. P., Shenai, S., Krapp, F., et al. (2010). Rapid molecular detection of tuberculosis and rifampin resistance. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907847,

Bonadonna, L. V., Saunders, M. J., Zegarra, R., Evans, C., Alegria-Flores, K., and Guio, H. (2017). Why wait? The social determinants underlying tuberculosis diagnostic delay. PLoS One 12:e0185018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185018,

Bwanga, F., Hoffner, S., Haile, M., and Joloba, M. L. (2009). Direct susceptibility testing for multi drug resistant tuberculosis: a meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 9:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-67,

Carandang, T. H. D. C., Cunanan, D. J., Co, G. S., Pilapil, J. D., Garcia, J. I., Restrepo, B. I., et al. (2025). Diagnostic accuracy of nanopore sequencing for detecting mycobacterium tuberculosis and drug-resistant strains: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 15:11626. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-90089-x Erratum in: Sci Rep.,

Casali, N., Nikolayevskyy, V., Balabanova, Y., Harris, S., Ignatyeva, O., Kontsevaya, I., et al. (2014). Evolution and transmission of drug-resistant tuberculosis in a Russian population. Nat. Genet. 46, 279–286. doi: 10.1038/ng.2878,

Chen, L., Li, N., Liu, Z., Liu, M., Lv, B., Wang, J., et al. (2012). Genetic diversity and drug susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Zunyi, one of the highest-incidence-rate areas in China. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 1043–1047. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06095-11,

Dookie, N., Rambaran, S., Padayatchi, N., Mahomed, S., and Naidoo, K. (2018). Evolution of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a review on the molecular determinants of resistance and implications for personalized care. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73, 1138–1151. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx506,

Farhat, M. R., Shapiro, B. J., Kieser, K. J., Sultana, R., Jacobson, K. R., Victor, T. C., et al. (2013). Genomic analysis identifies targets of convergent positive selection in drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Genet. 45, 1183–1189. doi: 10.1038/ng.2747,

Ferro, B. E., García, P. K., Nieto, L. M., and van Soolingen, D. (2013). Predictive value of molecular drug resistance testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Valle del Cauca, Colombia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51, 2220–2224. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00429-13,

Flores-Treviño, S., Morfín-Otero, R., Rodríguez-Noriega, E., González-Díaz, E., Pérez-Gómez, H. R., Mendoza-Olazarán, S., et al. (2015). Characterization of phenotypic and genotypic drug resistance patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from a city in Mexico. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 33, 181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2014.04.005,

Gygli, S. M., Borrell, S., Trauner, A., and Gagneux, S. (2017). Antimicrobial resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: mechanistic and evolutionary perspectives. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 41, 354–373. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux011,

Hameed, H. M. A., Tan, Y., Islam, M. M., Guo, L., Chhotaray, C., Wang, S., et al. (2019). Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of levofloxacin- and moxifloxacin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates in southern China. J. Thorac. Dis. 11, 4613–4625. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.11.03,

Isakova, J., Sovkhozova, N., Vinnikov, D., Goncharova, Z., Talaibekova, E., Aldasheva, N., et al. (2018). Mutations of rpoB, katG, inhAand ahp genes in rifampicin and isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Kyrgyz Republic. BMC Microbiol. 18:22. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1168-x,

Ismail, N., Ismail, F., Omar, S. V., Blows, L., Gardee, Y., Koornhof, H., et al. (2018). Drug resistant tuberculosis in Africa: current status, gaps and opportunities. Afr J Lab Med. 7:781. doi: 10.4102/ajlm.v7i2.781,

Jagielski, T., Bakuła, Z., Roeske, K., Kamiński, M., Napiórkowska, A., Augustynowicz-Kopeć, E., et al. (2014). Detection of mutations associated with isoniazid resistance in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69, 2369–2375. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku161,

Jagielski, T., Brzostek, A., van Belkum, A., Dziadek, J., Augustynowicz-Kopeć, E., and Zwolska, Z. (2015). A close-up on the epidemiology and transmission of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Poland. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 34, 41–53. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2202-z,

Jonmalung, J., Prammananan, T., Leechawengwongs, M., and Chaiprasert, A. (2010). Surveillance of pyrazinamide susceptibility among multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Siriraj hospital, Thailand. BMC Microbiol. 10:223. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-223,

Khosravi, A. D., Sirous, M., Abdi, M., and Ahmadkhosravi, N. (2019). Characterization of the most common embCAB gene mutations associated with ethambutol resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Iran. Infect Drug Resist. 12, 579–584. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S196800,

Kocagöz, T., Hackbarth, C. J., Unsal, I., Rosenberg, E. Y., Nikaido, H., and Chambers, H. F. (1996). Gyrase mutations in laboratory-selected, fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40, 1768–1774. doi: 10.1128/AAC.40.8.1768,

Köser, C. U., Cirillo, D. M., and Miotto, P. (2020). How to optimally combine genotypic and phenotypic drug susceptibility testing methods for pyrazinamide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64, e01003–e01020. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01003-20

Li, Q., Wang, Y., Li, Y., Gao, H., Zhang, Z., Feng, F., et al. (2019). Characterisation of drug resistance-associated mutations among clinical multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Hebei Province, China. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 18, 168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.03.012,

Liu, A. (2024). Catalase-peroxidase (katG): a potential frontier in tuberculosis drug development. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 59, 434–446. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2025.2470630,

Liu, D., Huang, F., Zhang, G., He, W., Ou, X., He, P., et al. (2022). Whole-genome sequencing for surveillance of tuberculosis drug resistance and determination of resistance level in China. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 28, 731.e9–731.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.09.014,

Liu, L., Jiang, F., Chen, L., Zhao, B., Dong, J., Sun, L., et al. (2019). The impact of combined gene mutations in inhAand ahpC genes on high levels of isoniazid resistance amongst katG non-315 in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis isolates from China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 7:183. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0184-0

Lohiya, A., Suliankatchi Abdulkader, R., Rath, R. S., Jacob, O., Chinnakali, P., Goel, A. D., et al. (2020). Prevalence and patterns of drug resistant pulmonary tuberculosis in India-a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 22, 308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.03.008,

Luo, D., Chen, Q., Xiong, G., Peng, Y., Liu, T., Chen, X., et al. (2019). Prevalence and molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant M. tuberculosis in Jiangxi province, China. Sci. Rep. 9:7315. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43547-2,

Maningi, N. E., Daum, L. T., Rodriguez, J. D., Said, H. M., Peters, R. P. H., Sekyere, J. O., et al. (2018). Multi- and extensively drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in South Africa: a molecular analysis of historical isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 56, e01214–e01217. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01214-17,

Migliori, G. B., Langendam, M. W., D'Ambrosio, L., Centis, R., Blasi, F., Huitric, E., et al. (2012). Protecting the tuberculosis drug pipeline: stating the case for the rational use of fluoroquinolones. Eur. Respir. J. 40, 814–822. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00036812,

Mohamed, S., Köser, C. U., Salfinger, M., Sougakoff, W., and Heysell, S. K. (2021). Targeted next-generation sequencing: a Swiss army knife for mycobacterial diagnostics? Eur. Respir. J. 57:2004077. doi: 10.1183/13993003.04077-2020,

Mokrousov, I., Otten, T., Vyshnevskiy, B., and Narvskaya, O. (2002). Detection of embB306 mutations in ethambutol-susceptible clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from northwestern Russia: implications for genotypic resistance testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40, 3810–3813. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.10.3810-3813.2002,

Nusrath Unissa, A., Hanna, L. E., and Swaminathan, S. (2016). A note on derivatives of isoniazid, rifampicin, and pyrazinamide showing activity against resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 87, 537–550. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12684,

Pei, S., Song, Z., Yang, W., He, W., Ou, X., Zhao, B., et al. (2024). The catalogue of Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutations associated with drug resistance to 12 drugs in China from a nationwide survey: a genomic analysis. Lancet Microbe. 5:100899. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(24)00131-9,

Ramasubban, G., Therese, K. L., Vetrivel, U., Sivashanmugam, M., Rajan, P., Sridhar, R., et al. (2011). Detection of novel coupled mutations in the katG gene (His276Met, Gln295His, and Ser315Thr) in a multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain from Chennai, India, and insight into the molecular mechanism of isoniazid resistance using structural bioinformatics approaches. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 37, 368–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.11.023,

Sandgren, A., Strong, M., Muthukrishnan, P., Weiner, B. K., Church, G. M., and Murray, M. B. (2009). Tuberculosis drug resistance mutation database. PLoS Med. 6:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000002,

Shinnick, T. M., Starks, A. M., Alexander, H. L., and Castro, K. G. (2015). Evaluation of the Cepheid Xpert MTB/RIF assay. Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 15, 9–22. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2015.976556,

Siddiqi, N., Shamim, M., Hussain, S., Choudhary, R. K., Ahmed, N., Prachee,, et al. (2002). Molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from patients in North India. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 443–450. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.2.443-450.2002

Smittipat, N., Juthayothin, T., Billamas, P., Jaitrong, S., Rukseree, K., Dokladda, K., et al. (2016). Mutations in rrs, rpsL and gidB in streptomycin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Thailand. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 4, 5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2015.11.009,

Sun, W., Gui, X., Wu, Z., Zhang, Y., and Yan, L. (2022). Prediction of drug resistance profile of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MDR-MTB) isolates from newly diagnosed cases by whole genome sequencing (WGS): a study from a high tuberculosis burden country. BMC Infect. Dis. 22:499. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07482-4,

Tan, Y., Hu, Z., Zhang, T., Cai, X., Kuang, H., Liu, Y., et al. (2014). Role of pncA and rpsA gene sequencing in detection of pyrazinamide resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from southern China. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 291–297. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01903-13,

Treatment Action Group, Stop TB Partnership. Tuberculosis research funding trends 2005–2017. (2025). Available online at: https://www.treatmentactiongroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/tb_funding_2018_final.pdf (Accessed March 1, 2025].

Unissa, A. N., Subbian, S., Hanna, L. E., and Selvakumar, N. (2016). Overview on mechanisms of isoniazid action and resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 45, 474–492. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.09.004

Walker, T. M., Miotto, P., Köser, C. U., Fowler, P. W., Knaggs, J., Iqbal, Z., et al. (2022). The 2021 WHO catalogue of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex mutations associated with drug resistance: a genotypic analysis. Lancet Microbe. 3, e265–e273. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00301-3,

Wan, L., Liu, H., Li, M., Jiang, Y., Zhao, X., Liu, Z., et al. (2020). Genomic analysis identifies mutations concerning drug-resistance and Beijing genotype in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from China. Front. Microbiol. 11:1444. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01444,

Wang, G., Jiang, G., Jing, W., Zong, Z., Yu, X., Chen, S., et al. (2021). Prevalence and molecular characterizations of seven additional drug resistance among multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in China: a subsequent study of a national survey. J. Infect. 82, 371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.02.004,

Wang, L., Yang, J., Chen, L., Wang, W., Yu, F., and Xiong, H. (2022). Whole-genome sequencing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for prediction of drug resistance. Epidemiol. Infect. 150:e22. doi: 10.1017/S095026882100279X,

Wang, J., Yu, C., Xu, Y., Chen, Z., Qiu, W., Chen, S., et al. (2023). Analysis of drug-resistance characteristics and genetic diversity of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis based on whole-genome sequencing on the Hainan Island, China. Infect. Drug Resist. 16, 5783–5798. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S423955,

WHO. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on TB detection and mortality in 2020.2021. (2025). Available online at: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/defaultsource/hq-tuberculosis/impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-tbdetection-and-mortality-in-2020.pdf (Accessed March 14, 2025).

World Health Organization. (2022). WHO operational handbook on tuberculosis. Module 3: Diagnosis - Rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection, 2022 update. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240089501 (Accessed April 5, 2024).

World Health Organization (2023). Catalogue of mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and their association with drug resistance. 2nd Edn. Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report (2024). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240101531 (Accessed November 1, 2024).

Wu, X., Lu, W., Shao, Y., Song, H., Li, G., Li, Y., et al. (2019). pncA gene mutations in reporting pyrazinamide resistance among the MDR-TB suspects. Infect. Genet. Evol. 72, 147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.11.012,

Xu, K., Ding, C., Mangan, C. J., Li, Y., Ren, J., Yang, S., et al. (2017). Tuberculosis in China: a longitudinal predictive model of the general population and recommendations for achieving WHO goals. Respirology 22, 1423–1429. doi: 10.1111/resp.13078,

Yin, X., and Yu, Z. (2010). Mutation characterization of gyrA and gyrB genes in levofloxacin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates from Guangdong Province in China. J. Infect. 61, 150–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.05.001,

Yu, M. C., Hung, C. S., Huang, C. K., Wang, C. H., Liang, Y. C., and Lin, J. C. (2022). Differential impact of the rpoB mutant on rifampin and Rifabutin resistance signatures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is revealed using a whole-genome sequencing assay. Microbiol Spectr. 10:e0075422. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00754-22,

Zeng, M. C., Jia, Q. J., and Tang, L. M. (2021). rpoB gene mutations in rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from rural areas of Zhejiang, China. J. Int. Med. Res. 49:300060521997596. doi: 10.1177/0300060521997596,

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, drug resistance, gene mutation, molecular epidemiology, mutation profile

Citation: Xu Y, Liu S, Zheng J, Lin J, Gi L and Chang Q (2025) Drug resistance profile of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in China: update until 2024. Front. Microbiol. 16:1697490. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1697490

Edited by:

Svetlana Khaiboullina, University of Nevada, Reno, United StatesReviewed by:

Djaltou Aboubaker Osman, Center of Study and Research of Djibouti (CERD), EthiopiaKin Israel Notarte, Johns Hopkins University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Xu, Liu, Zheng, Lin, Gi and Chang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiaocheng Chang, Y2hhbmdxaWFvY2hlbmcyMDAxQDE2My5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Yannan Xu

Yannan Xu Sixuan Liu

Sixuan Liu Jiaxiong Zheng1

Jiaxiong Zheng1 Qiaocheng Chang

Qiaocheng Chang