- 1K. A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia

- 2Institute of Oceanography, Viet Nam Academy of Science and Technology, Nha Trang, Viet Nam

Introduction: Psammodictyon is a widely distributed marine diatom genus with a complex taxonomy and underestimated species diversity.

Methods: Light and scanning electron microscopy, phylogenetic analysis and gas chromatography were used for study of the newly isolated strains of Psammodictyon.

Results: Twelve strains of Psammodictyon were isolated from the coastal waters of central Viet Nam. Based on detailed morphological examinations using light and scanning electron microscopy, as well as molecular phylogenetic analysis, we propose six new species to science. Our phylogenetic analysis indicates that Psammodictyon forms a closely related monophyletic group. The resolution power of the short genetic markers (V4, V9 18S rRNA, V9-ITS1 18S rRNA, and a short region of rbcL), which are widely used for metabarcoding, is also discussed. Analysis of the fatty acid content of seven Psammodictyon strains showed that, like most diatoms, they accumulate high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids (29.44–42.62%) and monounsaturated fatty acids (20.2–23.2%).

Conclusion: The number of known species in the genus Psammodictyon has increased to 21. Psammodictyon strains may be considered as potential producers of long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids.

1 Introduction

Psammodictyon is a mainly marine genus of canal-raphe-bearing diatoms belonging to the family Bacillariaceae. It was described by Mann (Round et al., 1990) with Psammodictyon panduriforme (W. Gregory) D. G. Mann (≡Nitzschia panduriformis W. Gregory) as its type. In contrast to Nitzschia, the valves of Psammodictyon are panduriform with an undulate surface and the areolae are loculate (chambered), creating decussate (transapical and diagonally orientated) striae (Round et al., 1990; Kezlya et al., 2025b).

Psammodictyon taxa are often common and/or dominant in various biotopes and geographic regions, with Psammodictyon panduriforme and P. constrictum (W. Gregory) D. G. Mann being mentioned most frequently. Both taxa were described by Gregory as Nitzschia panduriformis Gregory (1857) and Tryblionella constricta Gregory (1855), respectively. The latter species was reclassified within Nitzschia (Cleve and Grunow, 1880). The incompleteness of Gregory’s descriptions led to the misapplication of these names. The taxa described and illustrated as Nitzschia panduriformis and N. constricta in identification texts (e.g., Van Heurck, 1881, 1885; Peragallo and Peragallo 1897–1908; Witkowski et al., 2000) actually represent other species. Recently, Mann and Trobajo (2025) noted a similar problem for Tryblionella compressa (Bailey) Poulin. Witkowski et al. (2000) emphasized that the entire complex around Nitzschia panduriformis requires a general taxonomic revision. A study of the type specimens of both Psammodictyon panduriforme and P. constrictum will help to better understand their identity and actual geographic distribution.

The favorable growth characteristics of Psammodictyon taxa have allowed their strains to be used in applied research. For instance, Camargo et al. (2016) studied optical and material properties of the P. panduriforme frustules and showed that they have quasi-regular pore patterns on the biosilica valves, which can be utilized in optoelectronic devices with mesoporous structures. Guan et al. (2019) investigated two strains of canal-raphe-bearing diatoms, Nitzschia bilobata (AQ1) and Psammodictyon panduriforme (NP), as cation exchange materials for lysozyme purification from chicken egg white. They demonstrated that diatom frustules are more effective and could serve as an alternative chromatographic matrix for lysozyme purification.

It should be noted that the strains used in these studies obviously do not belong to Psammodictyon panduriforme, as their valve shape and size do not correspond with those reported by Gregory (1857). Correct species identification is crucial for applied research.

Lipids are the significant components of diatom cells. The lipid content in diatom algae can reach up to 25% of dry weight, although the production of lipids depends on growth conditions (Yi et al., 2017). Diatom lipids comprise a diverse group of fatty acids, including saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) (Pekkoh et al., 2022). Omega-3 fatty acids are essential for human health and wellness, particularly eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), two long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (Tyagi et al., 2024). Despite significant progress in fatty acids research, there has been only one investigation on the lipid content of two Psammodictyon strains (Krishnaswami et al., 2024).

The phylogenetic placement of the genus Psammodictyon has been repeatedly shown in previous studies. Representatives of Psammodictyon form a well-supported clade within the Bacillariales, demonstrating monophyly (Rimet et al., 2011; Witkowski et al., 2015; Ashworth et al., 2017; Carballeira et al., 2017; Sabir et al., 2018; Mann et al., 2021; Mucko et al., 2021; Olszyński et al., 2025). However, in these studies, no more than six strains were included in the analysis, and a detailed assessment of phylogenetic relationships within the Psammodictyon was not performed.

This study aims to examine the morphology, molecular phylogeny (based on 18S rRNA, rbcL, and internal transcribed spacer regions), and fatty acid content of Psammodictyon strains isolated from the coastal waters of Viet Nam.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sampling

The samples used in this study were collected along the coast of central Viet Nam (Figure 1). Both phytoplankton and epiphyte samples were collected. For phytoplankton samples, the surface water was filtered through a 29-μm plankton net and transferred into 50 mL tubes. For epiphytes samples, the macrophytes were scraped into a tray with approximately 50 mL of seawater, and the resulting suspension was transferred into 15 mL tubes. All samples were stored at room temperature until further analysis in the laboratory.

Water salinity and temperature were measured using an Atago PAL-06S seawater refractometer (Atago, Japan).

2.2 Culturing

A subsample was added to the enriched seawater, artificial water liquid medium (Andersen and Kawachi, 2005; Polyakova et al., 2018). A monoclonal strain was established by micropipetting a single cell under a Zeiss Axio Vert. A1 inverted microscope. A non-axenic monoculture was cultivated in ESAW liquid medium in Petri dishes at 22–25 °C with an alternating 12-h light and dark photoperiod. The strain was analyzed after 1 month of culturing. A list of all strains examined in this study and the geographic locations of sampling sites with measured ecological parameters is presented in Table 1.

2.3 Preparation of slides and microscope investigation

Strains for light microscopic (LM) and scanning electron microscopy investigations were processed following a standard procedure involving treatment with concentrated hydrogen peroxide and final washes with distilled water (Kezlya et al., 2020). Permanent diatom preparations were mounted in Naphrax® (Brunel Microscopes Ltd., Chippenham, United Kingdom; refractive index = 1.73). LM observations were performed using an AxioScope A1 microscope (Zeiss, Germany) equipped with an oil immersion objective (×100/n.a.1.4, differential interference contrast) and an AxioCam Erc 5s camera in the Laboratory of Molecular Systematics of Aquatic Plants, K. A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences. The ultrastructure of the valves was examined with a TESCAN Vega III scanning electron microscope (TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic) in the Borissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences.

2.4 Molecular study

Total DNA from the studied strain was extracted using Chelex 100 Chelating Resin (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, United States) according to protocol 2.2. Nuclear gene V4 and V9-ITS1 regions of 18S rRNA and plastid rbcL gene were amplified. For the highly variable V4 region of 18S rRNA (~390 bp), primers D512for and D978rev were used (Zimmermann et al., 2011). For the highly variable V9-ITS1 region of 18S rRNA (~430–580 bp), primers Euk1391F and ITS2_broad (Boenigk et al., 2018) were used. The plastid rbcL was amplified using two pairs of primers rbcL40 + and rbcL587-, and rbcL404 + and rbcL1444 (Ruck and Theriot, 2011). Polymerase chain reaction amplifications were performed using premade mastermixes (ScreenMix, Evrogen, Moscow, Russia).

Amplification of the V4 region of 18S rDNA was performed using the following program: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 52 °C for 30 s, and elongation at 72 °C for 50 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min, then held at 12 °C. Amplification of the V9-ITS1 region of 18S rDNA region was performed using the following program: initial denaturation of 5 min at 96 °C; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 96 °C (30 s), annealing at 52 °C (60 s), and elongation at 72 °C (75 s); and a final extension at 72 °C (10 min), then held at 12 °C. Amplification of the rbcL gene was performed using the following program: initial denaturation of 4 min at 94 °C; followed by 44 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C (50 s), annealing at 53 °C (50 s), and elongation at 72 °C (80 s); and a final extension at 72 °C (10 min), then held at 12 °C.

The PCR products were visualized on a 1.0% agarose gel stained with SYBR™ Safe (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, United States) and then purified using a mixture of FastAP, 10 × FastAP Buffer, Exonuclease I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States), and water. The purified PCR products were sequenced using the Sanger Sequencing method by “Syntol” scientific production company (Moscow).

Newly obtained sequences were manually edited in Ridom TraceEdit ver. 1.1.0 (Ridom GmbH, Münster, Germany) and Mega ver. 11 (Kumar et al., 2016). For two-gene analysis (V4 18S rRNA and rbcL), the reads were combined with GenBank-extracted sequences of 69 diatom strains from the family Bacillariaceae, including Nitzschia Hassall, Tryblionella W. Smith, Bacillaria J. F. Gmelin, Cylindrotheca Rabenhorst, Denticula Kützing, and Psammodictyon. Four Actinocyclus Ehrenberg strains were chosen as an outgroup (taxon names and accession numbers are provided in Supplementary Table S1). The 18S rDNA and rbcL sequences were aligned separately using the G-INS-i algorithm in the Mafft ver. 7 (RIMD, Osaka, Japan) (Katoh and Toh, 2010). The resulting dataset comprised 385 nucleotide sites of nuclear 18S rDNA and 1,229 sites of plastid rbcL regions. After removal of unpaired regions, the aligned 18S rRNA gene sequences were combined with the rbcL gene sequences into a single matrix for a concatenated rbcL and 18S rDNA tree.

The Bayesian inference (BI) method was performed to infer the phylogenetic position of new diatom strains using Beast ver. 1.10.1 (BEAST Developers, Auck-land, New Zealand) (Drummond and Rambaut, 2007). The most appropriate partition-specific substitution models, shape parameters α, and a proportion of invariable sites (pinvar) were determined by the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) in jModel-Test ver. 2.1.10 (Vigo, Spain) (Darriba et al., 2012). This BIC-based model selection procedure selected the following models, shape parameter (α), and proportions of invariable sites (pinvar): HKY + I + G, α = 0.3410 and pinvar = 0.4670 for 18S rDNA; HKY + I + G, α = 0.4390 and pinvar = 0.6840 for the first codon position of the rbcL gene; JC + I, pinvar = 0.8850 for the second codon position of the rbcL gene; GTR + I + G, α = 0.8890 and pinvar = 0.1750 for the third codon position of the rbcL gene. A speciation model was performed by a Yule process tree prior. Five Markov chain Monte Carlo analyses were run for seven million generations. The convergence diagnostics were performed in Tracer ver. 1.7.1 (MCMC Trace Analysis Tool, Edinburgh, United Kingdom) (Drummond and Rambaut, 2007). The initial 10% of trees were removed, and the remaining trees were used to construct a final chronogram with 90% posterior probabilities. Trees were viewed and edited using FigTree ver. 1.4.4 (University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom) and Adobe Photoshop CC ver. 19.0.

The V4 and V9, V9-ITS1 regions of 18S rDNA and rbcL sequences were also used to estimate the degree of similarity between gene sequences of different Psammodictyon strains (Supplementary Tables S2–S7). Using the Mega11, p-distances were determined to calculate sequence similarity using the formula (1–p) × 100. Tryblionella apiculata TRY946CAT was included in the analysis to estimate intergeneric genetic distances.

2.5 Fatty acid analysis

Biomass preparation for determining the fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) profiles was performed according to Maltsev et al. (2021). The diatom suspensions were conveyed to 15–50 mL tubes (depending on the volume). The cells were pelleted at room temperature for 3 min at 3600 g (Cence CHT210R (China)). The supernatant was removed, and the pelleted cells were resuspended in 10–15 mL (depending on the amount of biomass) of distilled water, quantitatively transferred to 15 mL centrifuge tubes, and pelleted again by centrifugation. The supernatant was removed, and the samples were quantitatively transferred to a 50-ml round-bottom flask. Heptadecanoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) was used as the internal standard for the fatty acid composition determination. To avoid the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids, all samples were processed under an argon atmosphere. Ten milliliters of 1 M KOH in 80% aqueous ethanol was added to the dry residue, the flask was sealed with a reflux condenser, and the mixture was maintained for 60 min at the boiling point (~80 °С). After this, the solvents were evaporated in vacuo to a volume of ~3 mL and quantitatively transferred with distilled water to a 50-ml centrifuge tube to a total volume of 25 mL, followed by extraction of unsaponifiable components with 10-ml portions of n-hexane (Himmed, Moscow, Russia) three times. To accelerate phase separation, the tube was centrifuged for 5 min at room temperature and at 2022xg. The aqueous phase was then acidified to a slightly acidic reaction (as indicated by indicator paper) with a few drops of 20% sulfuric acid (Himmed, Moscow, Russia), and free fatty acids were extracted with 20 mL of n-hexane. The n-hexane solution of free fatty acids was transferred to a dry 50-ml round-bottom flask, and the solvent was evaporated to dryness using a rotary evaporator IKA RV-10 (IKA-WERKE, Staufen im Breisgau, Germany), after which 10 mL of absolute methanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) and 1 mL of acetyl chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) were added to the dry residue. The flask, closed with a reflux condenser, was maintained for 1 h at 70 °С. The solvents were evaporated to dryness, a few drops of distilled water were added to the dry residue, and FAMEs were extracted with n-hexane.

The obtained FAMEs were analyzed using a Chromatec Crystal 5000.2 NP device (ZAO SKB Chromatec, Russian Federation) equipped with a quadrupole mass spectrometric detector. A Restek Rtx-2330 capillary column (60 m; cat. no. 10726 Restek, United States) was used. The operating conditions were as follows: carrier gas linear velocity, 1 mL/min; injection volume, 1 μL; split ratio, 1:20; evaporator temperature, 260°С. The temperature program for gradient analysis was as follows: a plateau at 60°С for 8 min, heating to 170°С at a rate of 10°С/min and maintaining this temperature for 5 min, followed by heating from 170°С to 245°С at a rate of 6.5°С/min and maintaining this temperature until the end of the analysis. The detector temperature was 230°С, and the ionization energy was 70 eV. Identification and quantification of FAMEs were performed using Chromatec Analyst 3 software. All experiments and analyses were conducted in triplicate. Mean values and standard errors of the mean are presented in Table 2.

3 Results

3.1 Taxonomy

Psammodictyon lamii Kapustin, Kezlya and Kulikovskiy sp. nov. (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Psammodictyon lamii sp. nov. (A−F) Size diminution series, LM; (G) valve external view, SEM; (H) close-up view of the central part externally, SEM; (I) close-up view of the central part internally, SEM; (J) two valves showing hexagonal structure of the locular areolae, SEM; (K) girdle view (note the elevated distal part of the valve), SEM; (L) valve internal view, SEM; (M) close-up view of the apices externally, SEM; (N) close-up view of the apices internally, SEM. Scale bars: (A–G,J,K) = 10 μm; (H,I,L–N) = 5 μm.

Description: LM: Valves broadly lanceolate, slightly constricted in the middle, with subrostrate ends, a longitudinal fold along the apical axis and a narrow hyaline area shifted to the valve margin, 29.5–30 μm long, 11.5–13 μm broad in the widest part, and 11–12 μm at the constriction. Keeled raphe system present on valve margin, with 9–10 distinct fibulae in 10 μm, the middle pair more distant from others. Striae 20 in 10 μm, interrupted by a narrow hyaline area, areolae arranged in quincunx. SEM: Externally, the proximal valve side (i.e., the part next to the raphe) depressed and separated from the elevated distal side by a hyaline sternum. Striae decussate, composed of loculate areolae. External areolar openings round. External raphe fissures accompanied by a ridge. Central raphe endings separated by a nodule. Distal raphe endings deflected to the proximal valve side (see Figure 2M). Internally loculate areolae composed of hexagonal chambers (see Figure 2J). Inner areolae openings round, slightly depressed (see Figures 2L,I,N). Raphe terminates at apices in small helictoglossae.

Holotype: Permanent slide HD 09826, deposited at the K. A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences (HD), prepared from oxidized culture strain CBMCsvn758 isolated from sample NT-5 (10). Holotype illustrated in Figure 2A.

Isotype: Permanent slide 09826a, deposited at the Oceanographic Museum, Institute of Oceanography, Nha Trang, Viet Nam, with the accession number VMO: E 58216. Herbarium registration code VMO.

Type locality: Viet Nam, South China Sea, Trieu Co, Quang Tri, plankton (N 16.831604, E 107.275227), leg. E. Kezlya and D. Kapustin, 24 July 2024.

Reference strain. CBMCsvn758 deposited at the Culture and Barcode Collection of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria “AlgaBank” (CBMC), K. A. Timiryazwev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences and at the Microalgal Culture Collection of Institute of Oceanography, Viet Nam.

Sequence data: Partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V4 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX596449), partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V9-ITS1 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX560120), and partial rbcL sequence (GenBank accession number PX607289) for the strain CBMCsvn758.

Registration: https://phycobank.org/106048.

Etymology: The species is named after Prof. Lam Nguyen-Ngoc (Institute of Oceanography, Viet Nam) for his contribution to the study of algae in Viet Nam.

Psammodictyon haii Kapustin, Kezlya and Kulikovskiy sp. nov. (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Psammodictyon haii sp. nov. (A−I) Size diminution series, LM; (J,K) valve external view, SEM; (L,M) valve internal view, SEM. Scale bars: (A−I) = 10 μm; (J−M) = 5 μm.

Description: LM: Valves elliptic with almost parallel margins, ends cuneate to subrostrate, 17.5–19 μm long and 7.5–8.5 μm broad. Keeled raphe system present on valve margin, with 11–13 distinct fibulae in 10 μm, the middle pair more distant from others. Striae 27–29 in 10 μm, interrupted by a narrow hyaline area, areolae arranged in quincunx. SEM: Externally the proximal valve side (i.e., the part next to the raphe) slightly depressed and separated from the elevated distal side by a hyaline sternum. Striae decussate, composed of loculate areolae. External areolar openings round. External raphe fissures accompanied by a ridge. Central raphe endings separated by a nodule. Distal raphe endings hooked (see Figure 3K). Inner areolae openings round, slightly depressed. Raphe terminates at apices in small helictoglossae.

Holotype: Permanent slide HD 09813, deposited at the K. A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences (HD) prepared from oxidized culture strain CBMCsvn745 isolated from sample NT-3 (5). Holotype illustrated in Figure 3F.

Isotype: Permanent slide 09813a, deposited at the Oceanographic Museum, Institute of Oceanography, Nha Trang, Viet Nam, with the accession number VMO: E 58217. Herbarium registration code VMO.

Type locality: Viet Nam, South China Sea, Cua Tung, Quang Tri, plankton (N 17.022566, E 107.116105), leg. E. Kezlya and D. Kapustin, 23 July 2024.

Reference strain: CBMCsvn745 deposited at the Culture and Barcode Collection of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria “AlgaBank” (CBMC), K. A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences and at the Microalgal Culture Collection of Institute of Oceanography, Viet Nam.

Sequence data: Partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V4 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX596448), partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V9-ITS1 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX560122), and partial rbcL sequence (GenBank accession number PX607290) for the strain CBMCsvn745.

Registration: https://phycobank.org/106049.

Etymology: The species is named after Dr. Hai Doan-Nhu (Institute of Oceanography, Viet Nam) for his contribution to the study of algae in Viet Nam.

Psammodictyon pusillum Kapustin, Kezlya and Kulikovskiy sp. nov. (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Psammodictyon pusillum sp. nov. (A−L) Size diminution series, LM; (A−C) strain CBMCsvn835; (D−H) strain CBMCsvn839; (I−L) strain CBMCsvn861; (M) valve external view, strain CBMCsvn839, SEM; (N) valve internal view, strain CBMCsvn839, SEM; (O) valve external view, strain CBMCsvn835, SEM; (P) valve internal view, strain CBMCsvn835, SEM; (Q) valve external view, strain CBMCsvn861, SEM; (R) valve internal view, strain CBMCsvn861, SEM; (S) teratological form, strain CBMCsvn839. Note the presence of the undulate raphe on the valve surface. Scale bars: (A–L) = 10 μm; (M−S) = 2 μm.

Description: LM: Valves panduriform, strongly constricted in the middle, with cuneate to subrostrate ends, 7–12 μm long, 4.5–6 μm broad in the widest part, and 4.5–5 μm at the constriction. Keeled raphe system present on valve margin, with 16–19 distinct fibulae in 10 μm. Striae 22–24 in 10 μm. SEM: Striae composed of loculate areolae with rectangular chambers. External raphe fissures accompanied by a ridge. Central raphe endings separated by a nodule. Distal raphe endings deflected to the mantle. Internally areolae have (2)3–4(6) openings. Raphe terminates at apices in small helictoglossae.

Holotype: Permanent slide HD 09924, deposited at the K. A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences (HD), prepared from oxidized culture strain CBMCsvn839 isolated from sample NT-22 (66). Holotype illustrated in Figure 4A.

Isotype: Permanent slide 09924a, deposited at the Oceanographic Museum, Institute of Oceanography, Nha Trang, Viet Nam, with the accession number VMO: E 58218. Herbarium registration code VMO.

Type locality: Viet Nam, South China Sea, Nha Trang Bay, epiphytes on Sargassum sp. (N 12.2075779, E 109.2155615), leg. E. Kezlya and D. Kapustin, 30 July 2024.

Reference strain: CBMCsvn839 deposited at the Culture and Barcode Collection of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria “AlgaBank” (CBMC), K. A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences and at the Microalgal Culture Collection of Institute of Oceanography, Viet Nam.

Sequence data: Partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V4 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX596451), partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V9-ITS1 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX560121) and partial rbcL sequence (GenBank accession number PX607291) for the strain CBMCsvn839. Partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V4 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX596450), partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V9-ITS1 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX560123) and partial rbcL sequence (GenBank accession number PX607292) for the strain CBMCsvn835. Partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V4 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX596458), partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V9-ITS1 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX560125) and partial rbcL sequence (GenBank accession number PX607293) for the strain CBMCsvn861.

Representative specimens. Strain CBMCsvn835 (slide no. 09920, sample no. NT-22 (66) epiphytes on Sargassum sp.), strain CBMCsvn861 (slide no. 09945, sample no. NT-15 (40),) plankton).

Registration: https://phycobank.org/106050.

Etymology: The species epithet reflects the small size of this species (Latin “pusillum” means “little”).

Psammodictyon minutum Kapustin, Kezlya and Kulikovskiy sp. nov. (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Psammodictyon minutum sp. nov. (A−K) Size diminution series, LM; (A−F) strain CBMCsvn943; (G−K) strain CBMCsvn846; (L) valve external view, strain CBMCsvn943, SEM; (M) valve external view, strain CBMCsvn846, SEM; (N) valve internal view, strain CBMCsvn943, SEM; (O) valve internal view, strain CBMCsvn846, SEM. Scale bars: (A–K) = 10 μm; (L−O) = 2 μm.

Description: LM: Valves panduriform, strongly constricted in the middle, with cuneate to subrostrate ends, 11–13.5 μm long, 5.5–6.5 μm broad in the widest part, and 4.5–5.5 μm at the constriction. Keeled raphe system present on valve margin, with 16 fibulae in 10 μm. Striae 22 in 10 μm. SEM: Striae composed of loculate areolae with rectangular chambers. External locular openings round, except for those close to the proximal valve margin. External raphe fissures accompanied by a ridge. Central raphe endings separated by a nodule. Distal raphe endings deflected to the mantle. Girdle bands open. Internally areolae have (2)3–4 openings. Raphe terminates at apices in small helictoglossae.

Holotype: Permanent slide HD 10026, deposited at the K. A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences (HD), prepared from oxidized culture strain CBMCsvn943 isolated from sample NT-4 (9). Holotype illustrated in Figure 5E.

Isotype: Permanent slide 10026a, deposited at the Oceanographic Museum, Institute of Oceanography, Nha Trang, Viet Nam, with the accession number VMO: E 58219. Herbarium registration code VMO.

Type locality: Viet Nam, South China Sea, Cua Tung, Quang Tri, epizoic on mollusc shell (N 17.019236, E 107.111506), leg. E. Kezlya and D. Kapustin, 23 July 2024.

Reference strain: CBMCsvn943 deposited at the Culture and Barcode Collection of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria “AlgaBank” (CBMC), K. A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences and at the Microalgal Culture Collection of Institute of Oceanography, Viet Nam.

Representative specimen. Strain CBMCsvn846 (slide no. 09931, sample no. NT-22 (66), epiphytes on Sargassum sp).

Sequence data: Partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V4 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX596452) partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V9-ITS1 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX560124) and partial rbcL sequence (GenBank accession number PX607294) for the strain CBMCsvn943. Partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V4 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX596453), partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V9-ITS1 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX560126) and partial rbcL sequence (GenBank accession number PX607295) for the strain CBMCsvn846.

Registration: https://phycobank.org/106051.

Etymology: The species epithet reflects the small size of this species (Latin “minutum” means “minute, small”).

Psammodictyon lanceolatum Kapustin, Kezlya and Kulikovskiy sp. nov. (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Psammodictyon lanceolatum sp. nov. (A−N) Size diminution series, LM; (O−Q) valve external view, SEM; (O) whole valve; (P) central part; (Q) valve apex; (R−T) valve internal view, SEM; (R) whole valve; (S) central part; (T) valve apex. Scale bars: (A−N) = 10 μm; (O,R) = 5 μm; (P,Q,S,T) = 2 μm.

Description: LM: Valves lanceolate, slightly constricted in the middle, with cuneate ends, 15–16.5 μm long, 5–5.5 μm broad in the widest part, and 4.5–5 μm at the constriction. Keeled raphe system present on valve margin, with 15–19 distinct fibulae in 10 μm, the middle pair more distant from others. Striae almost parallel, 18–22 in 10 μm. SEM: Striae composed of loculate areolae with rectangular chambers. External raphe fissures accompanied by a ridge. Central raphe endings separated by a nodule. Distal raphe endings deflected to the mantle. Internally, areolae have 3–4 openings. Raphe terminates at apices in small helictoglossae.

Holotype: Permanent slide HD 09950, deposited at the K. A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences (HD), prepared from oxidized culture strain CBMCsvn866 isolated from sample NT-15 (40). Holotype illustrated in Figure 6D.

Isotype: Permanent slide 09950a, deposited at the Oceanographic Museum, Institute of Oceanography, Nha Trang, Viet Nam, with the accession number VMO: E 58220. Herbarium registration code VMO.

Type locality: Viet Nam, South China Sea, Thi Nai lagoon, Qui Nhon, plankton (N 13.827088, E 109.258570), leg. E. Kezlya and D. Kapustin, 27 July 2024.

Sequence data: Partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V4 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX596454), partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V9-ITS1 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX560130), and partial rbcL sequence (GenBank accession number PX607288) for the strain CBMCsvn866.

Reference strain: CBMCsvn866 deposited at the Culture and Barcode Collection of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria “AlgaBank” (CBMC), K. A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences and at the Microalgal Culture Collection of the Institute of Oceanography, Viet Nam.

Registration: https://phycobank.org/106052.

Etymology: The species epithet reflects the lanceolate valve shape.

Psammodictyon similis Kapustin, Kezlya and Kulikovskiy sp. nov. (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Psammodictyon similis sp. nov. (A−J) Size diminution series, LM; (K−N) valve external view, SEM; (K) whole valve; (M) central part; (N) valve apex; (N) girdle view; (O−Q) valve internal view, SEM; (O) whole valve; (P) central part (proximal raphe ends visible); (Q) valve apex. Scale bars: (A−J) = 10 μm; (K,N,O) = 5 μm; (L,M,P,Q) = 2 μm.

Description: LM: Valves lanceolate, slightly constricted in the middle, with cuneate ends, and with hyaline sternum, 15–16.5 μm long, 5–5.5 μm broad in the widest part, and 4.5–5 μm at the constriction. Keeled raphe system present on valve margin, with 15–19 distinct fibulae in 10 μm, the middle pair more distant from others. Striae 18–22 in 10 μm, interrupted by a narrow hyaline area, areolae arranged in quincunx. SEM: Externally the proximal valve side (i.e., the part next to the raphe) slightly depressed and separated from the elevated distal side by a hyaline sternum. Striae decussate, composed of loculate areolae. External areolar openings round. External raphe fissures accompanied by a ridge. Central raphe endings separated by a nodule. Inner areolae openings round, slightly depressed. Raphe terminates at apices in small helictoglossae.

Holotype: Permanent slide HD 09818, deposited at the K. A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences (HD), prepared from oxidized culture strain CBMCsvn750 isolated from sample NT-3 (5). Holotype illustrated in Figure 7A.

Isotype: Permanent slide 09818a, deposited at the Oceanographic Museum, Institute of Oceanography, Nha Trang, Viet Nam, with the accession number VMO: E 58221. Herbarium registration code VMO.

Type locality: Viet Nam, South China Sea, Cua Tung, Quang Tri, plankton (N 17.022566, E 107.116105), leg. E. Kezlya and D. Kapustin, 23 July 2024.

Reference strain: CBMCsvn750 deposited at the Culture and Barcode Collection of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria “AlgaBank” (CBMC), K. A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences and at the Microalgal Culture Collection of Institute of Oceanography, Viet Nam.

Representative specimen. Strain CBMCsvn749 (slide no. 09817, sample no. NT-3 (5).

Sequence data: Partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V4 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX596456) and partial rbcL sequence (GenBank accession number PX607296) for the strain CBMCsvn750. Partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V4 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX596455) and partial rbcL sequence (GenBank accession number PX607297) for the strain CBMCsvn749.

Registration: https://phycobank.org/106053.

Etymology: The species epithet reflects the morphological similarity of the new species to the known Psammodictyon taxa.

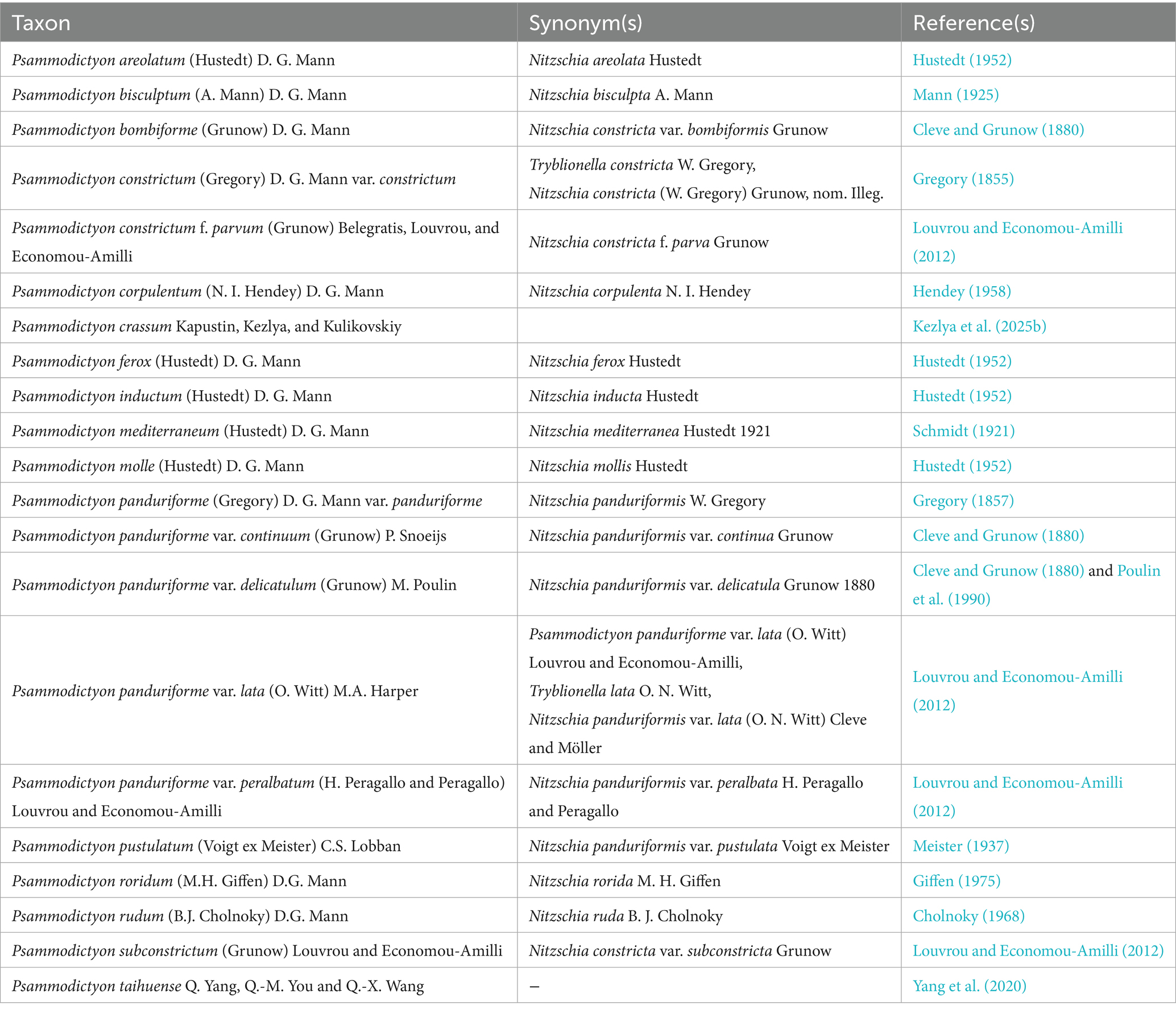

Psammodictyon cf. constrictum (W. Gregory) D. G. Mann (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Psammodictyon cf. constrictum: (A−Q) size diminution series, LM; (A−H) strain CBMCsvn771; (I−Q) strain CBMCsvn773; (R) valve external view, strain CBMCsvn771, SEM; (S) close-up view of the valve near the apices internally, strain CBMCsvn771, SEM. Scale bars: (A−Q) = 10 μm; (R) = 5 μm, (S) = 1 μm.

Description: LM: Valves panduriform, strongly constricted in the middle, with subrostrate ends, 17.3–18 μm long, 7.6–8.6 μm broad in the widest part, 6.3–7.3 μm at the constriction. Keeled raphe system present on valve margin, with 16 fibulae in 10 μm. Striae 23 in 10 μm. SEM: External locular openings round to elliptic. Internally, areolae have (2)3–4(5) openings.

Sequence data. Partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V4 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX596457) and partial rbcL sequence (GenBank accession number PX607298) for the strain CBMCsvn771. Partial 18S rRNA gene sequence comprising V4 domain sequence (GenBank accession number PX596459) and partial rbcL sequence (GenBank accession number PX607299) for the strain CBMCsvn773.

Representative specimens. Strain CBMCsvn771 (slide no. 09839) and strain CBMCsvn773 (slide no. 09841) from sample no. NT-19 (58).

3.2 Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was performed on the nuclear region V4 of the 18S rRNA and the plastid rbcL. The final data set included 85 strains, of which 81 belong to the family Bacillariaceae (Nitzschia, Tryblionella, Bacillaria, Cylindrotheca, Denticula, Psammodictyon), with four strains of Actinocyclus Ehrenberg added as an outgroup. For the analysis of relationships within Psammodictyon, 13 strains of this genus from the GenBank and 12 strains studied here were included (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Phylogenetic position of the studied Psammodictyon strains (indicated in bold) based on Bayesian inference (BI) for the partial rbcL and SSU rRNA genes (87 sequences). The total alignment length is 1,614 characters. Posterior probabilities from BI (constructed in Beast) are presented at the nodes. Strain numbers are indicated for all sequences.

The phylogenetic analysis showed that the genera Bacillaria and Cylindrotheca form separate clades with maximum support (PP 1). Nitzschia strains are the most numerous in our dataset (n = 27) and were grouped into five clades that are scattered throughout the tree, showing polyphyly. Ten strains from the genus Tryblionella are included in the analysis, of which eight form the highest supported clade (PP 1), and two—Tryblionella sp. LJiang2024c HYU D104 and T. cf. compressa TRY1007CAT—with high supports (PP 0.98 and 1.0, respectively) belong to the clades with Nitzschia and Nitzschia/Denticula, respectively (see Figure 9).

Psammodictyon shows monophyly and forms a separate maximally supported clade (PP 1) near Nitzschia dalmatica and a clade that includes strains of Nitzschia dubiiformis, N. tracheaformis, and N. pellucida. Compared with other genera of Bacillariaceae, all Psammodictyon species are closely related to each other and are divided into two subclades (see Figure 9).

One subclade with a high statistical support (PP 0.97) consists of the strains of the species studied here, namely P. similis sp. nov. (CBMCsvn749, CBMCsvn750), P. constrictum (CBMCsvn771, CBMCsvn773), P. pusillum sp. nov. (CBMCsvn835, CBMCsvn839, CBMCsvn861), P. lanceolatum sp. nov. (CBMCsvn866), and strains of P. panduriforme var. continuum from GenBank. The second subclade (PP 0.85) includes strains of the new species P. minutum sp. nov. (CBMCsvn846, CBMCsvn943), P. lamii sp. nov. CBMCsvn758, the recently described P. crassum CBMCsvn634 (Kezlya et al., 2025b), and strains of P. pustulatum and P. constrictum. One more new species, P. haii sp. nov. CBMCsvn745, forms a separate lineage within the Psammodictyon clade.

The results of a pairwise similarity analysis based on p-distance showed that the sequences of the strains assigned to the same species based on morphological characteristics are completely identical across all studied regions (similarity = 100%) (Supplementary Tables S2–S7). For example, the obtained sequences for the V4 18S rRNA, rbcL, and V9-ITS1 regions for strains CBMCsvn861, CBMCsvn835, and CBMCsvn839 assigned to P. pusillum sp. nov., and for strains CBMCsvn846 and CBMCsvn943 assigned to P. minutum sp. nov., have 100% similarity.

The comparison of the V4 region of the 18S rRNA sequences (alignment length = 385 nt) revealed 100% similarity between eight strains belonging to two taxa—P. constrictum (CBMCsvn771, CBMCsvn773, strain s0309) and P. panduriforme var. continuum (Supplementary Table S2). These taxa also have high similarity (99.5–99.7%, which corresponds to differences of only 1–2 nt) with P. similis sp. nov. (strains CBMCsvn749, CBMCsvn750), Psammodictyon sp. KSA2015-2_Nitz-M4, P. pustulatum KSA2015-38, P. lamii sp. nov. CBMCsvn758, and P. crassum CBMCsvn634. In addition, there are no differences between strains belonging to P. minutum sp. nov. (CBMCsvn 846, CBMCsvn 943) and P. panduriforme strain L or between P. pusillum sp. nov. (CBMCsvn 835, CBMCsvn 839, CBMCsvn 861) and P. lanceolatum sp. nov. (CBMCsvn 866) in this region. Overall, for the V4 region of 18S rRNA, average pairwise sequence similarity values for Psammodictyon species range from 98% (P. sp. KSA2015-37_Nitz-ED) to 99.4% (P. constrictum CBMCsvn 771 and CBMCsvn773, P. panduriforme var. continuum (strains 1PP60427D, 1PP60427E, 1PP60510A), P. constrictum s0309) (Supplementary Table S2). Average intergeneric similarity values (Psammodictyon/Tryblionella) range from 93 to 94%.

For the rbcL region, two alignments were used for genetic distance analysis: the first included 25 strains of Psammodictyon with a length of 734 nt (Supplementary Table S3), and the second included 20 strains with a length of 1,071 nt (Supplementary Table S4). Both alignments showed similar results. Complete sequence similarity was observed between the strains belonging to the same species (P. similis (strains CBMCsvn771, CBMCsvn773), P. constrictum (strains CBMCsvn749, CBMCsvn750), P. pusillum sp. nov. (strains CBMCsvn835, CBMCsvn 839, CBMCsvn861), P. minutum sp. nov. (strains CBMCsvn943, CBMCsvn846), and between strains from GenBank (P. constrictum strains Nate Site1 and GU7X-7 peanut5)) (Supplementary Tables S3, S4). Average sequence similarities in pairwise comparisons within the genus range from 98%/97.9% (for P. lanceolatum sp. nov. CBMCsvn866) to 99.3% (P. panduriforme var. continuum (1PP60602B, 1PP60427F), P. minutum sp. nov. (CBMCsvn846, CBMCsvn943), P. constrictum (GU7X-7_peanut5, Nate Site 1), and P. crassum CBMCsvn634). The highest sequence similarities for the rbcL region (99.5–99.9%) were observed in both alignments in subclade B between P. minutum sp. nov./P. panduriforme var. continuum 1PP60427F/P. constrictum/P. sp. (strains KSA2015-30 panduriform-1, KSA2015-2_Nitz-M4) and P. lamii sp. nov., and between P. crassum/P. constrictum NateSite 1/P. sp. KSA2015-2_Nitz-M4 (Supplementary Tables S3, S4).

Sequence similarity values between genera do not exceed 91.7%.

3.2.1 Short barcode rbcL (p-distance)

An examination of the genetic distances between taxa using the rbcL region [~331 bp (379 bp with primers)], which is used in metagenomic studies of diatoms (Kezlya et al., 2023 and the references herein), showed results that are generally consistent with the same analysis performed on longer (734 and 1,071 nt) regions of this gene (Supplementary Table S5). However, the short barcode did not reveal any differences between the new species P. pusillum sp. nov. and P. lanceolatum sp. nov., while the similarity when comparing long regions does not exceed 99.4%. Also, short rbcL sequences completely coincided in P. minutum sp. nov. and P. panduriforme var. continuum 1PP60427F. It should be noted that despite the short length of the barcode region, in other cases, the percentage similarity values were close to the values obtained for long sections. That is, the short barcode region resolved almost all species. Average sequence similarity values for pairwise comparisons ranged from 97.7 to 98.8%. For the taxa of subclade B listed above, sequence similarity remained high (99.5–99.7%) (Supplementary Table S5).

3.2.2 Barcode V9 and V9-ITS1 18S rRNA (p-distance)

We obtained sequences for the V9-ITS1 region for only nine of the 13 strains. For four strains, we were unable to amplify this region. There are currently no sequences of this region for Psammodictyon in the GenBank, so the dataset included sequences obtained in this study only (n = 9).

The analysis of sequence similarity in the V9 region of the 18S rRNA (alignment length 144 nt) showed that this region was conserved in the studied representatives of Psammodictyon (Supplementary Table S6). The sequences of all strains of P. pusillum sp. nov., P. lanceolatum sp. nov., and P. minutum sp. nov. are completely identical (similarity 100%); there were also no differences in the V9 region of the 18S rRNA between the new species P. haii sp. nov. and P. lamii sp. nov. The similarity values of the V9 18S rRNA region between P. lamii sp. nov., P. crassum, and P. haii sp. nov. range from 98.5 to 93.5%.

For region V9-ITS1 18S rRNA, the alignment length was 373 nt after eliminating gaps and missing data. This region turned out to be more variable compared with the short V9. Complete sequence similarity was noted only between strains assigned to the same species (P. pusillum sp. nov.—three strains, P. minutum sp. nov.—two strains; Supplementary Table S7 and Figure 9). Intraspecific variability in this region was not revealed. With the exception of P. lanceolatum sp. nov., which showed the maximum similarity values with strains of P. pusillum sp. nov. (99.7%), the sequence similarity for the remaining species does not exceed 94.1%. The minimum average similarity values (79.4–86.4%) were noted for P. lamii sp. nov., P. crassum, and P. haii sp. nov. (Supplementary Table S7).

3.3 Fatty acid profiles

Analysis of the biomass at the stationary phase of growth revealed the dominance of saturated 16:0 palmitic acid (within the range of 22.07–38% of total FA), monounsaturated 16:1n-7 palmitoleic acid (20.2–23.2%), and long-chain polyunsaturated 22:6(n-3) docosahexaenoic acid (12.57–22.69%) for all strains (Table 2). Similarly, all fatty acid profiles of investigated strains contained long-chain 20:5(n − 3) eicosapentaenoic acid (12.1–18.82%) and saturated 18:0 stearic acid (5.66–10.78%). A small amount of the long-chain saturated 22:0 behenic acid (1.82, 3.01, 1.33%) was detected in P. similis sp. nov. CBMCsvn749, P. similis sp. nov. CBMCsvn750, and P. minutum sp. nov. CBMCsvn846 profiles. In addition, a reduced concentration of the omega-6 adrenic acid (7.94, 2.12, 6.15, 6.5%) was recorded in P. similis CBMCsvn749, P. lamii sp. nov. CBMCsvn758, P. pusillum sp. nov. CBMCsvn839, and P. minutum sp. nov. CBMCsvn846.

4 Discussion

4.1 Comparison with similar taxa

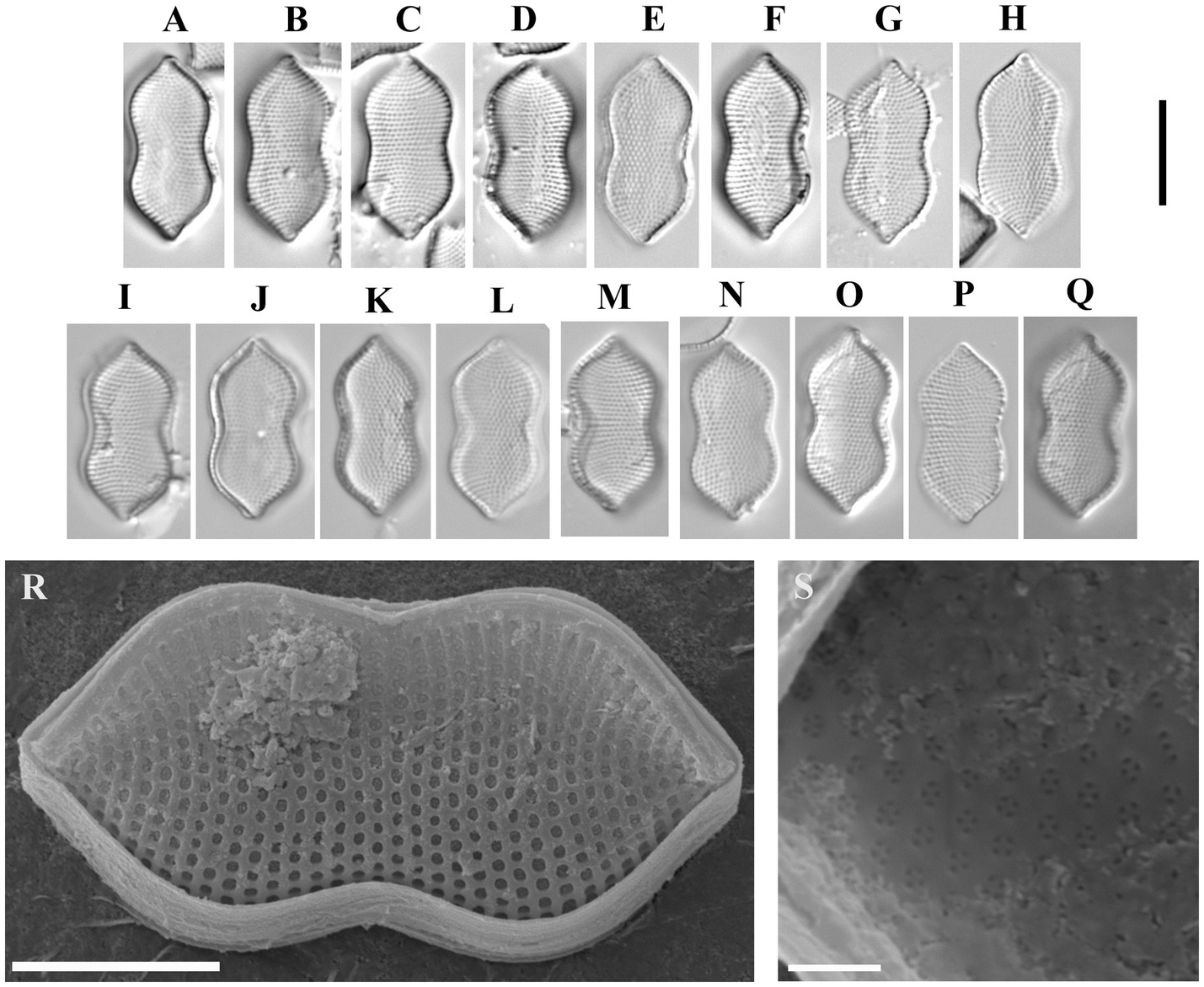

Our study confirmed that the diversity of the genus Psammodictyon is underestimated, especially for the small-sized taxa. This study increased the number of known species in the genus up to 21 (Table 3), with six new species described. However, many more taxa remain undescribed, and some older Nitzschia taxa should be transferred to Psammodictyon.

The valve shape of Psammodictyon lamii is almost identical to Nitzschia coarctata var. oceanica Frenguelli (Frenguelli, 1928), but in the latter taxon, the hyaline area is shorter and located at the valve center, whereas in P. lamii, the hyaline area is located along the longitudinal axis. In addition, N. coarctata var. oceanica is slightly longer and wider. Psammodictyon haii is also similar to Nitzschia coarctata var. oceanica but differs in the lack of constriction and in having much smaller valves (17.5–19 × 7.5–8.5 vs. 30–39 × 13–16 μm, respectively).

Both Psammodictyon minutum and P. pusillum belong to the P. constrictum species complex. Unfortunately, Gregory (1855) did not provide any morphometric data, making adequate comparison impossible. Morphologically, Psammodictyon minutum and P. pusillum are virtually identical with overlapping morphometric data. However, in P. minutum, the striae are distinctly punctate. This distinction possibly results from differences in ultrastructure: in P. pusillum, the areolae are rectangular externally, whereas in P. minutum, the external areolar openings are round, except near the proximal valve margin, where the areolae remain rectangular. These differences probably have no taxonomic value and may be related to the silification process. Both taxa are similar to P. constrictum apud Lobban et al. (2012). We identified our strains CBMCsvn771 and CBMCsvn773 as Psammodictyon cf. constrictum because they appear close to the smaller specimen depicted by Gregory (1855). Gregory (1855) did not provide the size of this species but described it as “pretty little,” and all variants described by Cleve and Grunow (1880) have valve lengths larger than 60 μm, or, in the case of “N. constricta var. genuina,” 16–27 μm. The valves of Psammodictyon cf. constrictum (strains CBMCsvn771 and CBMCsvn773) in this study were 17.3–18 μm long, 7.6–8.6 μm broad at the widest part (6.3–7.3 μm at the constriction), with 23 striae in 10 μm and 16 fibulae in 10 μm.

The valves of P. minutum and P. pusillum are smaller (see Table 4), but the striae and the fibulae densities are comparable. Although the morphology and the phylogenetic placement of the type of P. constrictum remain unknown, we believe that the description of the new taxa, P. minutum and P. pusillum, is justified, as they originate from the South China Sea rather than from Europe.

Table 4. Morphological and morphometric comparison of the new Psammodictyon species with similar taxa.

In valve shape, Psammodictyon lanceolatum is similar to Psammodictyon subconstrictum (Grunow) Louvrou and Economou-Amilli (≡Nitzschia panduriformis var. subconstricta Grunow); however, the latter species has a hyaline sternum, which is absent in P. lanceolatum. In contrast to Psammodictyon subconstrictum, P. lanceolatum has 18–20 striae in 10 μm, whereas the former species has 11–12 striae in 10 μm (see Table 4).

Psammodictyon similis is morphologically related to P. roridum, from which it can be distinguished by its smaller size (20.2–22.0 × 6.9–7.5 μm (6.1–6.8 μm at the constriction) in P. similis vs. 23–32 × 9–10 μm (8–9 μm at the constriction) in P. roridum).

In Psammodictyon, two types of loculate areolae can be distinguished: (1) with rectangular chambers (e.g., P. lanceolatum, P. minutum, P. pusillum) and (2) with hexagonal chambers (e.g., P. lamii, P. crassum, P. pustulatum KSA2015-38 Foram). The chamber shape correlates with the number of inner areolar openings—one in hexagonal chambers and more than two (usually 3–4) in rectangular chambers. This feature may have a taxonomic value.

4.2 Phylogeny

In this study, the Psammodictyon dataset for the phylogenetic analysis was significantly expanded and includes a total of 25 strains. The phylogenetic tree shows that Psammodictyon species are closely grouped in the highest supported clade (PP 1) near Nitzschia dubiiformis, N. tracheaformis, N. dalmatica, and N. pellucida (Figure 9). The close relationship of Psammodictyon and the above-mentioned Nitzschia has been repeatedly demonstrated in previous studies, where the Psammodictyon/Nitzschia clade had high bootstrap support (99–100), regardless of the set of genetic markers chosen for analysis (Ashworth et al., 2017; Carballeira et al., 2017; Sabir et al., 2018; Mann et al., 2021; Mucko et al., 2021; Barkia et al., 2019). Compared with other representatives of Bacillariaceae, Psammodictyon has low interspecific genetic distances.

In general, low interspecific distances (0.1–0.5% or 1–5 bp) for the V4 18S rRNA and rbcL marker regions have been repeatedly observed in closely related diatom species, for example, in closely related species of Sellaphora Mereschkowsky (Hamsher et al., 2011; Vanormelingen et al., 2013), Pinnularia, (Poulíčková et al., 2018; Kollár et al., 2019; Kollár et al., 2021; Pinseel et al., 2019), Achnanthidium minutissimum (Kützing) Czarnecki species complex (Pinseel et al., 2017), and Humidophila (Lange-Bertalot et Werum) R. L. Lowe et al. (Kezlya et al., 2025a). Psammodictyon studied here demonstrates a similar case.

The results of pairwise sequence comparison show that differences between species in the V4 region of the 18S rRNA can be only 0.3–0.5% (or 1–2 bp), for example, between P. similis sp. nov., P. constrictum, P. pustulatum, P. lamii sp. nov., and P. crassum (Supplementary Table S2).

The average sequence similarity values for the V4 region of the 18S rRNA vary from 98 to 99.4%. It is important to note that this region does not separate all species. In pairwise comparison, 100% sequence similarity was noted for the pairs P. constrictum/P. panduriforme var. continuum, P. pusillum sp. nov./P. lanceolatum sp. nov., and P. minutum sp. nov./P. panduriforme.

The rbcL gene allows separation of all Psammodictyon species regardless of the alignment length (734 or 1,071 bp), and no cases of complete sequence coincidence between different species were noted. Sequence differences between species generally exceed 1%, with average similarity values between species varying from 98 to 99.3% (Supplementary Tables S3, S4). The highest similarity (99.5–99.7%) was found between the group P. minutum sp. nov./P. panduriforme var. continuum 1PP60427F/P. constrictum s0309/P. lamii sp. nov. and the pair P. crassum/P. constrictum (GU7X-7_peanut5, NateSite 1). The latter are better differentiated by the V4 region of the 18S rRNA (98.7–98.9%). This group, except for P. lamii sp. nov. described here, includes small-celled species (Table 4) isolated from the South China Sea (P. minutum sp. nov. described here) and from the Black Sea, Russia (P. panduriforme var. continuum 1PP60427F; unpublished, location data from GenBank), while P. constrictum s0309 has no data about the isolation site. Their V4 region of the 18S rRNA also shows high similarity 99.5%, indicating a close relationship. P. lamii sp. nov. is separated from this group by the V4 18S rRNA (similarity 98.7%).

The small-celled species P. pusillum sp. nov. and P. lanceolatum sp. nov. are grouped into one branch (Figure 9). They differ very slightly in the rbcL gene (similarity 99.2–99.4%) and are completely identical in the marker regions V4, V9, and V9-ITS1 of the 18S rRNA (Supplementary Tables S2, S6, S7) and in the short barcode region of the rbcL gene (Supplementary Table S5). Nevertheless, both species clearly differ in valve shape and size (Table 4).

Our dataset contains five strains identified as P. constrictum: three from the GenBank (s0309, GU7X-7_peanut5, NateSite 1) and two strains studied here (CBMCsvn771, CBMCsvn773). Strains from GenBank are grouped in subclade B, whereas our strains form a separate branch in subclade A near P. similis (Figure 9). Sequence similarity between these groups for the rbcL gene does not exceed 99.2% (Supplementary Tables S3–S5); for the V4 region of 18S rRNA, 100% similarity was observed between the strains studied here and s0309, and 99.5% with the others. We identified our strains CBMCsvn771 and CBMCsvn773 as P. constrictum because we believe that the valve outline of our specimens is the closest to Gregory’s figure (Gregory, 1855, Figure 13). Dr. Matt Ashworth (UTEX Culture Collection of Algae) provided SEM micrographs of P. constrictum GU7X-7_peanut5 and P. constrictum NateSite 1. Morphologically, both strains are similar to each other and to our strains belonging to P. cf. constrictum, P. pusillum, and P. minutum. However, P. constrictum GU7X-7_peanut5 is larger than P. constrictum NateSite 1 (17.8–18.1 × 7.8–8.5 μm (7.6–8.0 μm at the constriction) vs. 11 × 5.2 μm (5.4 μm at the constriction) respectively). In addition, both strains have 3–4 internal areolar openings. Thus, P. constrictum represents a complex of cryptic species that requires further revision.

Owing to the high similarity of sequences among different species for the rbcL gene, especially in subclade B, we hypothesized that the short barcode region of the rbcL gene (331 bp), which is used for diatom metabarcoding (Vasselon et al., 2017; Kelly et al., 2018; Pérez-Burillo et al., 2022; Kezlya et al., 2023, and references herein), would not be able to distinguish the species. Our in silico validation showed that the short barcode region of rbcL can distinguish almost all species (except for the pairs P. pusillum sp. nov./P. lanceolatum sp. nov. and P. minutum sp. nov./P. panduriforme var. continuum 1PP60427F). The sequence similarity values are close to those obtained for the full-length gene.

Currently, the V9 region of the 18S rRNA is frequently used for metabarcoding of eukaryotic communities (van der Loos and Nijland, 2021; Kezlya et al., 2023), and it has been chosen to amplify eukaryotes in the global project “The Earth Microbiome Project” (EMP; https://earthmicrobiome.org/ (accessed on 25 August 2025)). The V4 region of the 18S rRNA is characterized as more variable when assessing the eukaryotic communities (Stoeck et al., 2010; Tanabe et al., 2016; Choi and Park, 2020; Tragin et al., 2018); however, a smaller reference dataset is available for V9 in diatoms (Piredda et al., 2017). The 18S rRNA gene sequences of Psammodictyon strains included in our analysis did not contain this region, so the comparison was performed only between the strains obtained in this study. Considering that only three of six species included in the analysis can be distinguished by the V9 region of the 18S rRNA, it can be concluded that this region is conservative in Psammodictyon and not effective for species separation.

The longer V9-ITS1 barcode region, which is also used for metabarcoding, proved to be much more effective (Kezlya et al., 2023 and the references herein). Despite the known issues of intragenomic variability in diatom ITS regions (Behnke et al., 2004; Evans et al., 2007; Kermarrec et al., 2013), no intraspecific variability was observed in our small sample of P. pusillum sp. nov and P. minutum sp. nov strains. Considering that all species were differentiated by this region, the sequence similarity level was very low compared to the V4 region of the 18S rRNA and rbcL markers and ranged from 78.5 to 94.1%, except for P. pusillum sp. nov./P. lanceolatum sp. nov. (similarity 99.7%).

4.3 Fatty acid content in Bacillariales

Сomparable values were obtained for marine Cylindrotheca strains, which accumulate a high percentage of PUFAs during the exponential phase (29.5–42.9%), especially 20:5 (n-3) and 20:4 (n-6) (Li et al., 2014). The dominant FAs in marine diatoms Nitzschia closterium CS-5 and Cylindrotheca fusiformis CS-13 were also reported as saturated 16:0 palmitic acid (7.2, 20%), monounsaturated 16:1n-7 palmitoleic acid (22.8, 19.7%), and long-chain 20:5(n−3) eicosapentaenoic acid (24.2, 20.3%) (Dunstan et al., 1993). Despite the fact that marine diatoms are considered promising sources of PUFA, marine strains P. constrictum MACC 34 and P. panduriforme MACC 35 are characterized by monounsaturated 16:1n-7 palmitoleic acid (15.26, 17.77%) and SFAs. In P. constrictum MACC 34, the dominant ones are 18:0 stearic acid (15.83%), 22:0 behenic acid (16.98%), and 24:0 lignoceric acid (22.97%), while in P. panduriforme MACC 35, the dominant FA is 18:0 stearic acid (58.37%) (Krishnaswami et al., 2024).

The study of FA composition in the examined Psammodictyon strains is particularly important given the general lack of biochemical studies on diatoms from Viet Nam and the near absence of research focused on this genus.

It is difficult to determine why the results obtained in this study differ so markedly from the literature data, as the available dataset for this genus remains limited. Our results suggest that genus Psammodictyon, like most diatoms, accumulates high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids (29.44–42.62%, with a maximum of 42.62% in P. minutum sp. nov. CBMCsvn846) and monounsaturated fatty acids (20.2–23.2%, with a maximum of 23.2% in P. minutum sp. nov. CBMCsvn846). Based on similar studies, it can be concluded that in marine diatoms, during the stationary growth phase, the dominant FAs are eicosapentaenoic, docosahexaenoic, and palmitoleic acids (Zhukova and Aizdaicher, 1995; Ying et al., 2000; Mao et al., 2020). It might be reasonable, therefore, to consider Psammodictyon strains as potential producers of long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids used in various fields such as medicine (Pereira et al., 2012; Dhanker et al., 2023), aquaculture (Yaakob et al., 2014), cosmetology (De Luca et al., 2021), and biotechnology (Barta et al., 2021). The role of diatoms in aquaculture with such characteristics is also beyond doubt, as they are the primary source of nutrients for secondary consumers in the food chain (Dhanker et al., 2024). Furthermore, diatoms rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids are an ideal option for biofuel production, given that—with the proper approach to cultivation and using the necessary equipment—they offer the lowest production costs with the highest yield of the final product (Dhanker et al., 2024). It is also worth noting that the use of algae for biofuel is essentially waste-free, as algae, in addition to PUFA, store proteins, antioxidants, vitamins, and other chemicals that can be utilized by humans as dietary supplements, agricultural fertilizers, or in medicine (Dhanker et al., 2022; Pereira et al., 2012).

5 Conclusion

Our phylogenetic analysis showed that Psammodictyon represents a closely related monophyletic group. Interspecific distances for the V4 region of 18S rRNA and rbcL were often no more than 1% (sometimes only 0.3–0.5%), and overall sequence similarity in the studied sample did not exceed 97.3%, with average values of 98–99.4%. Assessment of the resolving power of short barcodes [V4, V9, V9-ITS1 regions of 18S rRNA, short rbcL (331 bp)] for species separation showed that V9-ITS1 was the most variable (for five of six studied species, the similarity did not exceed 94.1%). The V4 and V9 regions of 18S rDNA failed to distinguish almost half of the species included in this analysis. The short rbcL fragment, except for two species pairs, effectively differentiated all Psammodictyon taxa, yielding sequence similarity values comparable to those obtained for the full-length gene. These findings are important to consider, for instance, when analyzing metagenomic data and when selecting genetic markers and thresholds for species assignment.

The fatty acid content in the cells of the studied Psammodictyon strains revealed increased proportions of palmitoleic, eicosapentaenoic, and docosahexaenoic acids, which are typical for marine diatoms. Therefore, these strains may be considered promising for cultivation as potential sources of long-chain polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids relevant to biotechnological applications.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material. The sequencing data for the strains CBMCsvn745, CBMCsvn749, CBMCsvn750, CBMCsvn758 CBMCsvn771, CBMCsvn773, CBMCsvn835, CBMCsvn 839, CBMCsvn846, CBMCsvn861, CBMCsvn866, CBMCsvn943 are available from the authors upon request.

Author contributions

EK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DK: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZK: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. YM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. LN-N: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. DH: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. HD-N: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Sampling, morphological, and molecular analyses were conducted with financial support from the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 24–44-04006, https://rscf.ru/project/24-44-04006/) and the Viet Nam Academy of Science and Technology (Project No. QTRU06.05/24–26) (50% contribution). Fatty acid analyses and manuscript preparation were supported by the State Assignment of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (Theme 124052200012–7 No. FFES-2024-0001) (50% contribution).

Acknowledgments

We thank R. A. Rakitov (Borissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences (PIN RAS)) for assistance with the scanning electron microscope. We also thank Matt Ashworth (UTEX Culture Collection of Algae, University of Texas, Austin), who kindly provided unpublished micrographs of some of his Psammodictyon strains.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1701605/full#supplementary-material

References

Andersen, R. A., and Kawachi, M. (2005). “Traditional microalgae isolation techniques” in Algal culturing techniques. ed. R. A. Andersen (Burlington: Elsevier Academic Press), 83–100.

Ashworth, M. P., Lobban, C. S., Witkowski, A., Theriot, E. C., Sabir, M. J., Baeshen, M. N., et al. (2017). Molecular and morphological investigations of the stauros-bearing, raphid pennate diatoms (Bacillariophyceae): Craspedostauros E.J. Cox, and Staurotropis T.B.B. Paddock, and their relationship to the rest of the Mastogloiales. Protist 168, 48–70. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2016.11.001,

Barkia, I., Li, C., Saari, N., and Witkowski, A. (2019). Nitzschia omanensis sp. nov., a new diatom species from the marine coast of Oman, characterized by valve morphology and molecular data. Fottea 19, 175–184. doi: 10.5507/fot.2019.008A

Barta, D. G., Coman, V., and Vodnar, D. C. (2021). Microalgae as sources of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: biotechnological aspects. Algal Res. 58:102410. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2021.102410

Behnke, A., Friedl, T., Chepurnov, V. A., and Mann, D. G. (2004). Reproductive compatibility and rDNA sequence analyses in the Sellaphora pupula species complex (Bacillariophyta). J. Phycol. 40, 193–208. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.03037.x

Boenigk, J., Wodniok, S., Bock, C., Beisser, D., Hempel, C., Grossmann, L., et al. (2018). Geographic distance and mountain ranges structure freshwater protist communities on a European scale. Metabarcoding Metagenom. 2:e21519. doi: 10.3897/mbmg.2.21519

Camargo, E., Perez Coca, J. J., Lin, C.-F., Lin, M.-S., Yu, T.-Y., Wu, M.-C., et al. (2016). Chemical and optical characterization of Psammodictyon panduriforme (Gregory) Mann comb. nov. (Bacillariophyta) frustules. Opt Mater Express 6, 1436–1443. doi: 10.1364/OME.6.001436

Carballeira, R., Trobajo, R., Leira, M., Benito, X., Sato, S., and Mann, D. G. (2017). A combined morphological and molecular approach to Nitzschia varelae sp. nov., with discussion of symmetry in Bacillariaceae. Eur. J. Phycol. 52, 342–359. doi: 10.1080/09670262.2017.1309575

Choi, J., and Park, J. S. (2020). Comparative analyses of the V4 and V9 regions of 18S rDNA for the extant eukaryotic community using the Illumina platform. Sci. Rep. 10:6519. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63561-z,

Cholnoky, B. J. (1968). Die Diatomeenassoziationen der Santa-Lucia-Lagune in Natal (Südafrika). Bot. Mar. Suppl 11, 1–121. doi: 10.1515/9783111388595

Cleve, P. T., and Grunow, A. (1880). Beiträge zur Kenntniss der arctischen Diatomeen. Kongl. Sven. Vetensk.-Akad. Handl. 17, 1–121.

Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R., and Posada, D. (2012). jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 9:772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109,

De Luca, M., Pappalardo, I., Limongi, A. R., Viviano, E., Radice, R. P., Todisco, S., et al. (2021). Lipids from microalgae for cosmetic applications. Cosmetics 8:52. doi: 10.3390/cosmetics8020052

Dhanker, R., Kumar, R., Tiwari, A., and Kumar, V. (2022). Diatoms as a biotechnological resource for the sustainable biofuel production: a state-of-the-art review. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 38, 111–131. doi: 10.1080/02648725.2022.2053319,

Dhanker, R., Saxena, A., Tiwari, A., Singh, P. K., Patel, A. K., Dahms, H. U., et al. (2024). Towards sustainable diatom biorefinery: recent trends in cultivation and applications. Bioresour. Technol. 391:129905. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2023.129905,

Dhanker, R., Singh, P., Sharma, D., Tyagi, P., Kumar, M., Singh, R., et al. (2023). “Diatom silica a potential tool as biosensors and for biomedical field” in Insights into the world of diatoms: from essentials to applications. eds. P. Srivastava, A. S. Khan, J. Verma, and S. Dhyani (Singapore: Springer Nature), 175–193.

Drummond, A. J., and Rambaut, A. (2007). BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214,

Dunstan, G. A., Volkman, J. K., Barrett, S. M., Leroi, J. M., and Jeffrey, S. W. (1993). Essential polyunsaturated fatty acids from 14 species of diatom (Bacillariophyceae). Phytochemistry 35, 155–161. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)90525-9

Evans, K. M., Wortley, A. H., and Mann, D. G. (2007). An assessment of potential diatom “barcode” genes (cox1, rbcL, 18S and ITS rDNA) and their effectiveness in determining relationships in Sellaphora (Bacillariophyta). Protist 158, 349–364. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2007.04.001,

Frenguelli, J. (1928). Diatomeas del Océano Atlántico frente a Mar del Plata (República Argentina). An. Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. 34, 497–572.

Giffen, M. H. (1975). An account of the Littoral diatoms from Langebaan, Saldanha Bay, Cape Province, South Africa. Bot. Mar. 18, 71–95. doi: 10.1515/botm.1975.18.2.71

Gregory, W. (1855). On some new species of British freshwater diatomaceae, with remarks on the value of certain specific characters. Proc. Bot. Soc. Edinb. 1855, 38–41.

Gregory, W. (1857). On new forms of marine Diatomaceae found in the firth of Clyde and in loch Fyne, illustrated by numerous figures drawn by R.K. Greville, LL.D., F.R.S.E. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 21, 473–542.

Guan, Y.-F., Lai, S.-Y., Lin, C.-S., Suen, S.-Y., and Wang, M.-Y. (2019). Purification of lysozyme from chicken egg white using diatom frustules. Food Chem. 286, 483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.02.023,

Hamsher, S. E., Evans, K. M., Mann, D. G., Poulíčková, A., and Saunders, G. W. (2011). Barcoding diatoms: exploring alternatives to COI-5P. Protist 162, 405–422. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2010.09.005,

Hendey, N. I. (1958). Marine diatoms from some west African ports. J. R. Microsc. Soc. 77, 28–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1957.tb02015.x,

Katoh, K., and Toh, H. (2010). Parallelization of the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Bioinformatics 26, 1899–1900. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq224,

Kelly, M., Boonham, N., Juggins, S., Kille, P., Mann, D., Pass, D., et al. (2018). A DNA based diatom metabarcoding approach for classification of rivers, in science report SC140024/R. Bristol, UK: Environment Agency.

Kermarrec, L., Franc, A., Rimet, F., Chaumeil, P., Humbert, J. F., and Bouchez, A. (2013). Next-generation sequencing to inventory taxonomic diversity in eukaryotic communities: a test for freshwater diatoms. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 13, 607–619. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12105,

Kezlya, E., Glushchenko, A., Maltsev, Y., Genkal, S., Tseplik, N., and Kulikovskiy, M. (2025a). Morphological variability amid genetic homogeneity and vice versa: a complicated case with Humidophila (Bacillariophyceae) from tropical forest soils of Vietnam with the description of four new species. Plants 14:1069. doi: 10.3390/plants14071069,

Kezlya, E., Glushchenko, A., Maltsev, Y., Gusev, E., Genkal, S., Kuznetsov, A., et al. (2020). Placoneis cattiensis sp. nov.—a new, diatom (Bacillariophyceae: Cymbellales) soil species from Cát Tiên National Park (Vietnam). Phytotaxa 460, 237–248. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.460.4.1

Kezlya, E., Kapustin, D., Doan-Nhu, H., Nguyen-Ngoc, L., Thi Ngoc, D. H., Maltsev, Y., et al. (2025b). Psammodictyon crassum sp. nov., a new diatom species from the coastal waters of Viet Nam described based on morphology and molecular data. Diatom Res. doi: 10.1080/0269249X.2025.2577199

Kezlya, E., Tseplik, N., and Kulikovskiy, M. (2023). Genetic markers for metabarcoding of freshwater microalgae: review. Biology 12:1038. doi: 10.3390/biology12071038,

Kollár, J., Pinseel, E., Vanormelingen, P., Poulíčková, A., Souffreau, C., Dvořák, P., et al. (2019). A polyphasic approach to the delimitation of diatom species: a case study for the genus Pinnularia (Bacillariophyta). J. Phycol. 55, 365–379. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12825,

Kollár, J., Pinseel, E., Vyverman, W., and Poulíčková, A. (2021). A time-calibrated multi-gene phylogeny provides insights into the evolution, taxonomy and DNA barcoding of the Pinnularia gibba group (Bacillariophyta). Fottea 21, 62–72. doi: 10.5507/fot.2020.017,

Krishnaswami, I., Sabu, S., Singh, I. B., and Joseph, V. (2024). Marine benthic diatom Psammodictyon panduriforme (MACC 35) as a potent producer of long chain hydrocarbons and fatty acids of biofuel significance. Algal Res. 79:103492. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2024.103492

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., and Tamura, K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054,

Li, H. Y., Lu, Y., Zheng, J. W., Yang, W. D., and Liu, J. S. (2014). Biochemical and genetic engineering of diatoms for polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis. Mar. Drugs 12, 153–166. doi: 10.3390/md12010153,

Lobban, C. C., Schefter, M., Jordan, R. W., Arai, Y., Sasaki, A., Theriot, C. E., et al. (2012). Coral-reef diatoms (Bacillariophyta) from Guam: new records and preliminary checklist, with emphasis on epiphytic species from farmer-fish territories. Micronesica, 43:237–479.

Louvrou, I., and Economou-Amilli, A. (2012). Transfer of four taxa of genus Nitzschia Hassall to genus Psammodictyon D.G. Mann (Bacillariophyceae). J. Biol. Res.-Thessalon. 17, 148–153.

Maltsev, Y., Krivova, Z., Maltseva, S., Maltseva, K., Gorshkova, E., and Kulikovskiy, M. (2021). Lipid accumulation by Coelastrella multistriata (Scenedesmaceae, Sphaeropleales) during nitrogen and phosphorus starvation. Sci. Rep. 11:19818. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-99376-9,

Mann, D. G., and Trobajo, R. (2025). Andrzej Witkowski was right: Tryblionella compressa is not a Tryblionella. Nova Hedwigia 120, 231–261. doi: 10.1127/nova_hedwigia/2025/0984

Mann, D. G., Trobajo, R., Sato, S., Li, C., Witkowski, A., Rimet, F., et al. (2021). Ripe for reassessment: a synthesis of available molecular data for the speciose diatom family Bacillariaceae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 158:106985. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2020.106985,

Mao, X., Chen, S. H. Y., Lu, X., Yu, J., and Liu, B. (2020). High silicate concentration facilitates fucoxanthin and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) production under heterotrophic condition in the marine diatom Nitzschia laevis. Algal Res. 52:102086. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2020.102086

Mucko, M., Bosak, S., Mann, D. G., Trobajo, R., Wetzel, C. E., Peharec Štefanić, P., et al. (2021). A polyphasic approach to the study of the genus Nitzschia (Bacillariophyta): three new planktonic species from the Adriatic Sea. J. Phycol. 57, 143–159. doi: 10.1111/jpy.13085-20-093

Olszyński, R. M., Górecka, E., Trobajo, R., Gastineau, R., Ashworth, M., and Mann, D. G. (2025). Taxonomic review of Tryblionella with special reference to the Apiculatae group—new characters of genus Tryblionella sensu stricto (Bacillariaceae). J. Phycol. 61, 330–352. doi: 10.1111/jpy.70004,

Pekkoh, J., Phinyo, K., Thurakit, T., Lomakool, S., Duangjan, K., Ruangrit, K., et al. (2022). Lipid profile, antioxidant and antihypertensive activity, and computational molecular docking of diatom fatty acids as ACE inhibitors. Antioxidants 11:186. doi: 10.3390/antiox11020186,

Peragallo, H., and Peragallo, M. (1897–1908). Diatomées marines de France et des districts maritimes voisins. Grez-sur-Loing: J. Tempère, Micrographe-Editeur.

Pereira, H., Barreira, L., Figueired, F., Custódio, L., Vizetto-Duarte, C., Polo, C., et al. (2012). Polyunsaturated fatty acids of marine macroalgae: potential for nutritional and pharmaceutical applications. Mar. Drugs 10, 1920–1935. doi: 10.3390/md10091920

Pérez-Burillo, J., Mann, D. G., and Trobajo, R. (2022). Evaluation of two short overlapping rbcL markers for diatom metabarcoding of environmental samples: effects on biomonitoring assessment and species resolution. Chemosphere 307:135933. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135933,

Pinseel, E., Kulichová, J., Scharfen, V., Urbánková, P., Van de Vijver, B., and Vyverman, W. (2019). Extensive cryptic diversity in the terrestrial diatom Pinnularia borealis (Bacillariophyceae). Protist 170, 121–140. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2018.10.001,

Pinseel, E., Vanormelingen, P., Hamilton, P. B., Vyverman, W., Van de Vijver, B., and Kopalová, K. (2017). Molecular and morphological characterization of the Achnanthidium minutissimum complex (Bacillariophyta) in Petuniabukta (Spitsbergen, high Arctic) including the description of A. digitatum sp. nov. Eur. J. Phycol. 52, 264–280. doi: 10.1080/09670262.2017.1283540

Piredda, R., Tomasino, M. P., D’Erchia, A. M., Manzari, C., Pesole, G., Montresor, M., et al. (2017). Diversity and temporal patterns of planktonic protist assemblages at a Mediterranean long term ecological research site. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 93:fiw200. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiw200

Polyakova, S. L., Davidovich, O. I., Podunay, Y. A., and Davidovich, N. A. (2018). Modification of the ESAW culture medium used for cultivation of marine diatoms. Mar. Biol. J. 3, 73–80. doi: 10.21072/mbj.2018.03.2.06

Poulíčková, A., Kollár, J., Hašler, P., Dvořák, P., and Mann, D. G. (2018). A new species Pinnularia lacustrigibba sp. nov. within the Pinnularia subgibba group (Bacillariophyceae). Diatom Res. 33, 273–282. doi: 10.1080/0269249X.2018.1513869

Poulin, M., Bérard-Therriault, L., Cardinal, A., and Hamilton, P. B. (1990). Les Diatomées (Bacillariophyta) benthiques de substrats durs des eaux marines et saumâtres du Québec. 9. Bacillariaceae. Nat. Can. 117, 73–101.

Rimet, F., Kermarrec, L., Bouchez, A., Hoffmann, L., Ector, L., and Medlin, L. K. (2011). Molecular phylogeny of the family Bacillariaceae based on 18S rDNA sequences: focus on freshwater Nitzschia of the section Lanceolatae. Diatom Res. 26, 273–291. doi: 10.1080/0269249X.2011.597988

Round, F. E., Crawford, R. M., and Mann, D. G. (1990). The diatoms. Biology and morphology of the genera. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ruck, E. C., and Theriot, E. C. (2011). Origin and evolution of the canal raphe system in diatoms. Protist 162, 723–737. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2011.02.003,

Sabir, J. S. M., Theriot, E. C., Manning, S. R., Al-Malki, A. L., Khiyami, M. A., Al-Ghamdi, A. K., et al. (2018). Phylogenetic analysis and a review of the history of the accidental phytoplankter, Phaeodactylum tricornutum Bohlin (Bacillariophyta). PLoS One 13:e0196744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196744,

Schmidt, A. W. F. (1921). Atlas der Diatomaceen-kunde. Ser. VII, H. 83. Pls, Leipzig: O.R. Reisland, 329–332.

Stoeck, T., Bass, D., Nebel, M., Christen, R., Jones, M. D., Breiner, H. W., et al. (2010). Multiple marker parallel tag environmental DNA sequencing reveals a highly complex eukaryotic community in marine anoxic water. Mol. Ecol. 19, 21–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04480.x,

Tanabe, A. S., Nagai, S., Hida, K., Yasuike, M., Fujiwara, A., Nakamura, Y., et al. (2016). Comparative study of the validity of three regions of the 18S-rRNA gene for massively parallel sequencing-based monitoring of the planktonic eukaryote community. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 16, 402–414. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12459,