- 1Vaccine Lab, WOOGENE B&G Co., LTD., Seoul, Republic of Korea

- 2College of Veterinary Medicine, Jeonbuk National University, Iksan, Republic of Korea

- 3Veterinary Diagnostic Center, Jeonbuk National University, Iksan, Republic of Korea

- 4Biosafety Research Institute, Jeonbuk National University, Iksan, Republic of Korea

- 5Korea Research Institute for Veterinary Biologics (KRIVB), Iksan, Republic of Korea

Introduction: Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), particularly strains harboring Stx2e, are the primary cause of edema disease (ED) in swine, leading to acute mortality and economic loss. Despite the use of antimicrobials and autogenous vaccines, control remains inadequate due to high genetic variability and upregulated multidrug resistance (MDR). In Korea, field outbreaks persist in post-weaning pigs, underscoring the need for immunologically relevant vaccine candidates. This study aimed to characterize STEC isolates from 2014 to 2025 and identify representative strains for vaccine development through integrated molecular, phenotypic, and resistance profiling.

Methods: A total of 184 STEC isolates were collected from clinical swine cases submitted between 2014 and 2025. Isolates were characterized via PCR-based virulence gene profiling, cytotoxicity assays using Vero cells, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and Gompertz-modeled in vitro growth kinetics. Principal component analysis (PCA) and multivariate clustering were applied to assess phenotypic patterns. Two candidate vaccine strains were selected using an integrated scoring system incorporating virulence, cytotoxicity, metabolic fitness, and antimicrobial resistance profiles.

Results: A total of 184 STEC isolates were recovered from swine diagnostic submissions across nine Korean provinces between 2014 and 2025. Genotypic analysis identified 29 virulence gene profiles, with Stx2e and F18 being predominant. Phenotypic assays revealed that Stx2e-only isolates exhibited superior growth kinetics and higher cytotoxicity than other genotypes. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing demonstrated widespread multidrug resistance, especially to sulfonamides, β-lactams, and aminoglycosides. Principal component analysis showed clustering based on toxin profiles and metabolic traits. No non-MDR isolates were observed, underscoring the high resistance burden. Two Stx2e-positive isolates with complementary F18 profiles, strong proliferation (>4.0 × 108 CFU/mL), and consistent cytotoxicity were selected as optimal vaccine candidates. Whole-genome sequencing confirmed their genetic stability and field relevance, supporting their advancement into vaccine development pipelines.

Conclusion: This study provides a decade-long surveillance-based framework for rational STEC vaccine design in swine. Two Stx2e-positive strains were selected as representative immunogen candidates based on integrated genotypic and phenotypic criteria. These findings support the development of scalable, field-relevant vaccine platforms aimed at reducing antimicrobial use and controlling edema disease in Korean pig populations.

1 Introduction

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a genetically diverse Gram-negative bacterium containing multiple pathotypes, several of which are recognized as primary etiological agents of enteric diseases in livestock (Braz et al., 2020). Among these, enterotoxigenic and Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (ETEC and STEC, respectively) are major contributors to post-weaning diseases in pigs (Tseng et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2022). Two significant diseases, including post-weaning diarrhea (PWD) and edema disease (ED), are frequently associated with these pathotypes and lead to considerable economic losses due to mortality, reduced growth rates, and increased veterinary pharmaceutical costs. It is a major pathogen that causes post-weaning diarrhea and/or edema disease in the swine industry (Kaper et al., 2004; Tabaran and Tabaran, 2019). While PWD typically occurs as non-bloody diarrhea shortly after weaning, clinical symptoms of ED as a peracute enterotoxemic condition characterized by neurological signs, subcutaneous edema, and sudden death (Imberechts et al., 1992). In high-density swine production systems, including those in the Republic of Korea, these diseases persist despite improvements in hygiene, biosecurity, and prophylactic interventions (Heo et al., 2020).

ED is predominantly caused by STEC strains carrying the stx2e gene, which encodes Shiga toxin 2e (Stx2e)—an AB5-type exotoxin characterized by strong angiotropism and the ability to induce vascular endothelial damage (Imberechts et al., 1992; Seo et al., 2018; Baldo et al., 2020). Structurally, Stx2e consists of an enzymatically active A subunit that inhibits protein synthesis in target cells and five B subunits that mediate binding to specific cell surface receptors, facilitating the internalization of the A subunit and subsequent cytotoxic effects (Melton-Celsa, 2014). These strains frequently co-express F18 fimbriae, which facilitate mucosal colonization of the distal small intestine, particularly the ileum, by mediating bacterial adhesion to epithelial surfaces. Following colonization, systemic translocation of Stx2e disrupts microvascular integrity, leading to characteristic clinical signs (Berger et al., 2023). The acute progression and high fatality of ED in post-weaned piglets underscore the limited efficacy of current prevention strategies, including both vaccination and chemoprophylaxis (Gannon et al., 1989; Do et al., 2019). In many pig production settings, repetitive subtherapeutic antimicrobial exposure during the early post-weaning period remains a common treatment (Seo et al., 2018; Berger et al., 2023; Cho et al., 2023). However, this approach has contributed to the emergence and clonal expansion of multidrug-resistant (MDR) STEC, complicating therapeutic control and raising concerns regarding antimicrobial stewardship and public health risks (Holmer et al., 2019). These challenges have emphasized the necessity of effective vaccination strategies as a more sustainable alternative to antimicrobial usage.

Although autologous (farm-specific) bacterin vaccines are employed in endemic farms, their protective efficacy is often suboptimal (Sperling et al., 2022). This is largely due to the heterogeneity in adhesin types, Shiga toxin subtypes, and plasmid-encoded accessory virulence factors among field isolates (Baldo et al., 2020; Sperling et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2022). Without detailed molecular and phenotypic characterization of local strains, cross-protection remains unreliable, and vaccine performance is inconsistent across herds. Thus, a rational strain selection process, such as one anchored in both epidemiological surveillance and laboratory-based functional profiling, is critical for developing broadly protective and immunologically relevant vaccines (Eriksen et al., 2021). In vitro characterization offers a practical and informative platform for vaccine candidate evaluation, particularly during the preclinical phase. Targeted PCR assays allow for rapid screening of virulence-associated genes, while cytotoxicity assays using Vero cells, bacterial growth curve analyses, and quantitative adhesion tests employing porcine intestinal epithelial cell lines enable assessment of strain safety, colonization potential, and metabolic robustness (Vidotto et al., 2009; Nammuang et al., 2024; Luppi, 2017). Furthermore, determining consistent growth kinetics under laboratory conditions and verifying the stability of virulence-associated plasmids enhances candidate viability for vaccine production (Sperling et al., 2022; Matise et al., 2003). These approaches are especially valuable in early development, where animal challenge studies may be delayed or limited due to ethical, logistical, or biosafety considerations (Sperling et al., 2022).

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and molecular diversity of STEC isolates collected from Korean pig farms between 2014 and 2025. A panel of in vitro assays was used to genetically characterize the strains, focusing on virulence gene profiles, cytotoxic potential, and growth properties. The ultimate goal was to identify high-virulence, genetically stable, and immunologically relevant strains as a vaccine candidate. By integrating longitudinal field surveillance with phenotypic profiling, this study establishes a framework for rational vaccine strain selection against edema disease and contributes to the broader effort to reduce STEC-associated disease burden in swine.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Molecular epidemiology characterization of STEC isolates in swine

2.1.1 Surveillance-based sample collection and regional distribution of edema disease cases in Korea (2014–2025)

From January 2014 to March 2025, clinical specimens were obtained from pigs suspected of edema disease or post-weaning diarrhea. These samples were submitted to the Jeonbuk National University Veterinary Diagnostic Center (JBNU-VDC) as part of routine veterinary diagnostic services. The submissions originated from commercial pig farms across nine provinces in the Republic of Korea and were collected without active field surveillance; therefore, sample selection was passive and case-based.

A total of 184 specimens were collected from pigs at various production stages: suckling piglets (<4 weeks of age, n = 12), weaning piglets (5–8 weeks, n = 84), growing pigs (9–16 weeks, n = 37), and finishing pigs (17–25 weeks, n = 23). For 28 cases, age information was not provided. Regional information regarding the farm of origin was recorded, and case counts were used to evaluate the spatial distribution of STEC-positive.

2.1.2 Classification of clinical specimens by anatomical source

Specimens were classified based on their anatomical origin at the time of receipt. Samples included feces (n = 127), intestinal content or mucosal tissue (n = 50), and internal organ samples such as lung (n = 4), brain (n = 2), and spleen (n = 1). Fecal samples were typically collected from live pigs presenting with clinical signs of diarrhea. In contrast, organ tissues and intestinal samples were obtained from the dead animals submitted for postmortem examination by attending veterinarians, as part of diagnostic investigations for suspected systemic infection or enterotoxaemia. This classification was used to stratify isolation rates and investigate potential site-specific differences in STEC prevalence and virulence characteristics.

All specimens were transported in chilled containers (4–8 °C) and processed within 24 h of arrival or stored at −80 °C for delayed analysis. To maintain bacterial viability, samples were stored in a cryoprotective medium containing 25% glycerol prior to long-term preservation at −80 °C. Solid tissues were homogenized in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to bacterial culture and DNA extraction. This classification was used to stratify isolation rates and investigate potential site-specific differences in STEC prevalence and virulence characteristics.

Fecal samples and homogenized tissue samples (intestine, lung, spleen, and brain) were serially diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 101 to 103 dilutions were plated onto Sorbitol MacConkey agar (SMAC, Oxoid, UK) for selective isolation of E. coli as previously described (Seo et al., 2018; Rivera et al., 2012). After overnight incubation at 37 °C, presumptive colonies were selected and subjected to identification using PCR targeting the virulence gene (Seo et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2010; Gao et al., 1999). Confirmed STEC isolates were routinely cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB, BD Difco™, USA) broth or Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB, BD Difco™, USA) at 37 °C with agitation. For solid culture or enumeration, the corresponding agar media (LB or TSB, respectively) were used. Mueller–Hinton agar (BD Difco™, USA) was employed for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, following established protocols (Seo et al., 2018).

2.2 Molecular characterization of STEC isolates based on virulence gene profiling and 16S rRNA Phylogenetics

Genomic DNA was extracted from overnight cultures of 184 E. coli isolates identified as Stx2e-positive Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC), which were grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth or Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) at 37 °C for 24 h. Bacterial suspensions (1 mL) were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min, and genomic DNA was extracted using the genomic DNA extraction kit (Wizard® Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quality and quantity were assessed by spectrophotometry (A260/A280), and integrity was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The extracted DNA was used both for multiplex PCR-based detection of virulence-associated genes and for 16S rRNA gene sequencing of vaccine candidate strains.

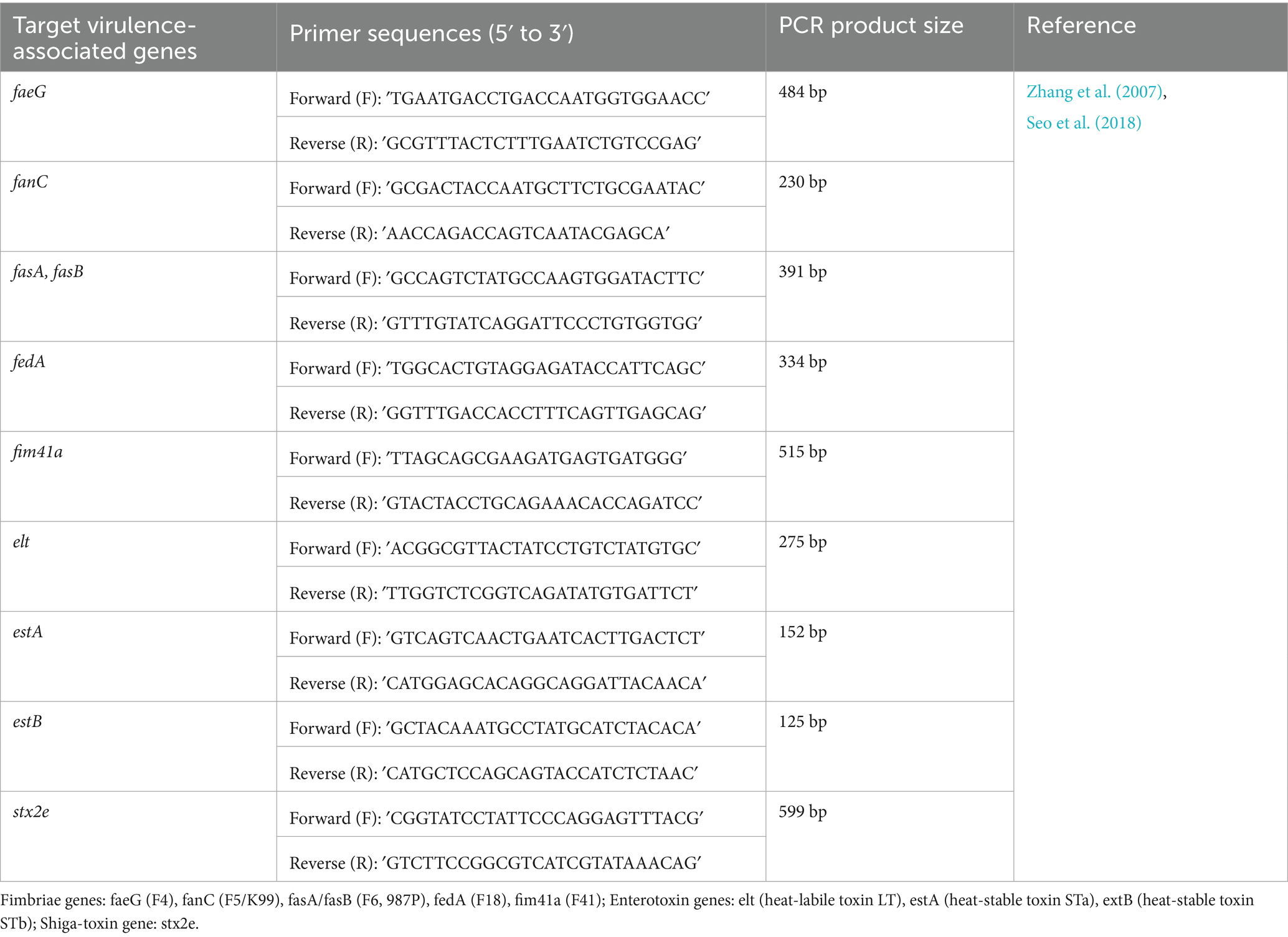

Multiplex PCR assays targeting virulence-associated genes were performed using a commercially available kit (AccuPower® Multiplex PCR PreMix, Bioneer, South Korea) in combination with specific primer sets (Table 1), as previously described (Seo et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2007). Target genes included fimbrial adhesins (F4, F5, F6, F18, F41), enterotoxins (LT, STa, STb), and Shiga toxin 2e (Stx2e). Amplification was conducted using a thermal cycler (SimpliAmp Thermal cycler, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) under the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 15 min; 25 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 63 °C for 90 s, and extension at 72 °C for 90 s; followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were held at 4 °C until analysis. Amplicons were resolved by electrophoresis on 3% agarose (BD Difco™, USA) gels containing RedSafe™ nucleic acid staining solution (iNtRON Biotechnology, South Korea) and visualized under ultraviolet light using a gel documentation system (GelDoc Go, BioRad, USA). Band sizes were compared to expected molecular weights to determine the presence of each virulence gene.

To evaluate the molecular taxonomy of the two vaccine candidate strains selected based on virulence profile and in vitro characteristics, 16S rRNA gene sequencing and phylogenetic analysis were conducted. The nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene (~1.5 kb) was amplified from these two isolates using universal bacterial primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-GGTTACC TTGTTACGACTT-3′) as previously described (Ludwig, 2007; Al-Balawi and Morsy, 2021). Each 25-μL PCR contained 1 × PCR buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1.2 μM of each primer, 1.25 U of high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Ex Taq Hot Start, Takara, Japan), and 50–100 ng of template DNA. Thermal cycling conditions were: 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 56 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min; final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Amplicons were verified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/mL) using a 1-kb DNA ladder, purified (Expin™ PCR SV, GeneAll, Korea), and subjected to bidirectional Sanger sequencing (Cosmogenetech, Daejeon, Korea). Forward and reverse reads were assembled and quality-trimmed in SeqMan Pro (Lasergene, DNASTAR), and taxonomic identity was verified by nucleotide BLAST. For phylogeny, assembled sequences were aligned with reference Enterobacteriaceae sequences (including E. coli, Shigella spp., Escherichia fergusonii, and Salmonella enterica) using ClustalW in MEGA 11; a neighbor-joining tree was inferred with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The resulting 16S rRNA tree is provided as Supplementary Figure S1.

2.3 Mammalian cell culture for cytotoxicity assay

African green monkey kidney cell line (Vero cell, ATCC® CCL-81, USA) was cultured in Minimum Essential Medium α (MEM-α, Gibco™, USA) supplemented with 5% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Gibco™, USA), 1% L-glutamine (Gibco™, USA), and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic cocktail (Anti-Anti, Life Technology, USA) containing 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL Fungizone® [amphotericin B] at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 environment. This formulation is referred to as MEM-α growth medium.

Vero cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂. Cells were routinely subcultured at 70–90% confluency using 0.5% trypsin–EDTA (Gibco™, USA) and then seeded into 96-well microplates 24 h prior to use in functional assays. Only cells within 10 passages from thawing were used to ensure experimental consistency. This culture system was used as a platform for performing cytotoxicity assays to distinguish STEC from various E. coli isolates.

2.3.1 Growth kinetics and principal component analysis (PCA) of representative STEC isolates

Representative STEC isolates were cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth. Overnight cultures were adjusted to an initial OD₆₀₀ of 0.05 in fresh LB and incubated at 37 °C with shaking (180 rpm). Bacterial growth was measured at 1-h intervals for 36 h using a spectrophotometer (OD₆₀₀). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Growth curves were analyzed by nonlinear regression using the Gompertz growth model implemented in GraphPad Prism version 9.0 (GraphPad Software, USA). From the fitted curves, three kinetic parameters were derived: exponential growth rate (EGR, h−1), lag phase duration (LPD, h), and maximal population density (MPD, OD₆₀₀). These parameters were estimated for each isolate according to established methods (Zwietering et al., 1990; Murakami et al., 2000).

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using three growth-related variables—AUC, EGR, and MPD—implemented in the FactoMineR and factoextra packages in R (v4.3.0, New Zealand). The resulting PCA plots were visualized to evaluate group-level clustering patterns based on toxin profiles.

2.3.2 Antimicrobial susceptibility profiling of STEC isolates by disc diffusion assay

The antimicrobial susceptibility of all E. coli isolates was assessed using the disc diffusion method on Mueller–Hinton agar (BD Difco™, USA), following Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (Seo et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2007). Bacterial suspensions were standardized to a 0.5 McFarland turbidity and inoculated onto agar plates prior to application of antibiotic discs.

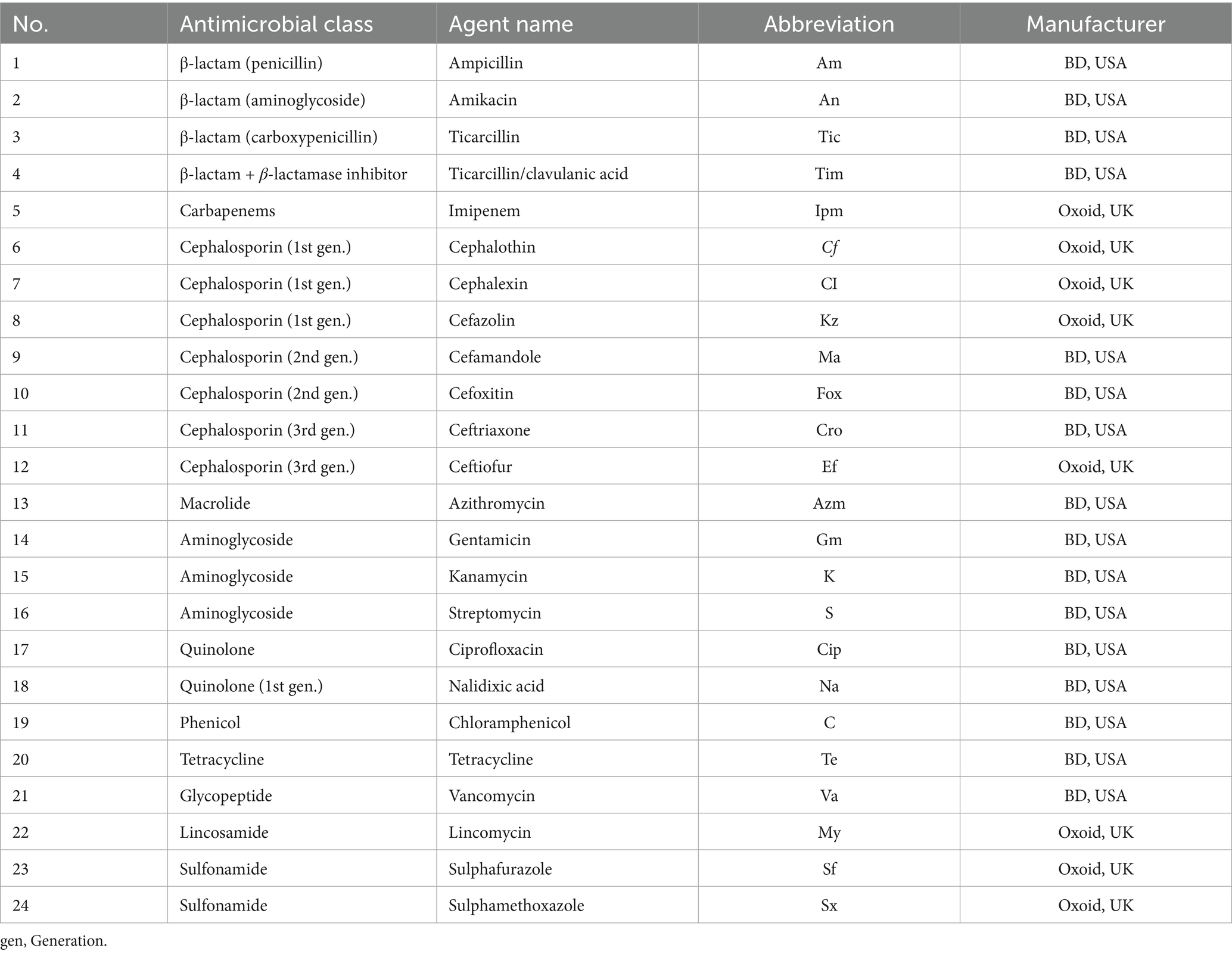

A total of 24 antimicrobial agents representing multiple pharmacological classes were tested (Table 2). All antibiotic discs were obtained from BD Biosciences (USA) or Thermo Scientific™ Oxoid™ (UK). Following incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, inhibition zone diameters were measured and interpreted as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant according to CLSI criteria. Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) was used as the quality control strain. Isolates displaying identical susceptibility profiles across all tested agents were grouped as the same resistance type for comparative analysis. Disc diffusion was performed following CLSI-VET M100 (2023) using 24 antimicrobial agents. For clarity, resistance classification was based on inhibition zone criteria rather than MIC breakpoints; therefore, carbapenem and cephalosporin resistance results are interpreted as phenotypic screening outcomes.

2.3.3 Quantitative cytotoxicity profiling of Shiga toxin-producing isolates using Vero cells

Vero cells (ATCC® CCL-81™) were seeded into 96-well plates at 2 × 104 cells/well and incubated overnight to reach ~80% confluency. STEC isolates were grown in Luria–Bertani broth (LB) at 37 °C with shaking (180 rpm) for 18 h. Culture supernatants were clarified by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 20 min and sterile-filtered using 0.22 μm syringe filters.

Serial 10-fold dilutions () of filtered supernatants were prepared in MEM-α growth medium. A total of 180 μL of diluted supernatant was added to each well containing 20 μL of MEM-α (total volume 200 μL). Plates were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ for 24 h. Cell viability was measured using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide) assay following previously described methods in similar studies on STEC isolates (Beutin et al., 2002; da Silva et al., 2019). Briefly, 20 μL of 5 mg/mL MTT solution (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for an additional 4 h. The assay evaluates the mitochondrial reduction of tetrazolium salts into formazan crystals by metabolically active (viable) cells, providing a quantitative measure of cell viability (Murakami et al., 2000). After incubation, the medium was carefully removed, and 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer (iMark™ Microplate Absorbance Reader, Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA).

Cytotoxicity was expressed as a percentage relative to untreated control wells. The cytotoxicity titer, representing the dilution of the supernatant that caused a reduction in cell viability of 50% or more, was calculated using non-linear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism (v9.0). The overall assay design was adapted from established methods for quantifying STEC-associated toxicity using Vero cells. The assay was applied as a functional surrogate of Stx2e-associated activity in accordance with veterinary vaccine strain screening practices; it is not toxin-subtype specific, and specificity was inferred from the consistent cytotoxicity–stx2e genotype correlation.

2.3.4 Whole-genome sequencing of vaccine candidate STEC strains

Two representative Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) isolates, selected based on distinct virulence gene profiles and characteristic in vitro phenotypes, were subjected to whole-genome sequencing (WGS) to comprehensively elucidate their genomic properties. Genomic DNA was extracted from bacterial cultures grown overnight at 37 °C under aerobic conditions using the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (Qiagen, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocol optimized for bacterial genomic DNA. DNA quality was assessed using both a NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and a Qubit® 4.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Samples used for WGS met strict quality criteria (concentration ≥70 ng/μL, A260/A280 ratio of 1.6–2.0, and volume ≥15 μL) were selected for subsequent library preparation.

Sequencing libraries were prepared by fragmenting 100 ng genomic DNA per sample to an average insert size of approximately 350 bp using a Covaris S2 Ultrasonicator (Covaris, USA). DNA libraries were then constructed with the TruSeq Nano DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, USA), following the manufacturer’s guidelines. The size distribution and integrity of the prepared libraries were verified electrophoretically using an Agilent Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent Technologies, USA). Library concentrations were quantified by qPCR using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit (Kapa Biosystems, USA).

Prepared libraries were subjected to cluster generation, followed by paired-end sequencing (2 × 150 bp) using the Illumina NovaSeq X Plus platform (Illumina, USA). Quality control of raw sequencing reads was performed using FastQC (v0.10.1), assessing sequence quality scores, base composition, and potential contamination. Quality-filtered reads were aligned against an appropriate reference genome using the ‘Map to Reference’ tool in Geneious Prime (v2025.2.1). Consensus sequences were generated from aligned data and subsequently annotated using Prokka (v1.14.6), enabling detailed genomic characterization.

2.4 Integrated evaluation for selection of field-relevant, immunologically relevant vaccine candidates

To select optimal STEC strains for Stx2e-based vaccine development, an integrated scoring strategy was applied to confirmed genotypic, phenotypic, and functional datasets. Candidate selection was restricted to isolates genetically verified to possess the Stx2e gene. Among them, candidate strains were ranked based on the following criteria:

(1) Virulence characteristics: Absence of adhesion-related fimbriae (e.g., F18, F41) or enterotoxin (LT, STa, STb) genes, while retaining the stx2e locus to ensure immunogenic relevance (Makino et al., 2001).

(2) Growth fitness: Efficient and stable in vitro proliferation based on Gompertz-modeled parameters (LPD, EGR, MPD) to support consistent biomass production (Zwietering et al., 1990).

(3) Antibiotic resistance: Inclusion of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains exhibiting resistance to multiple antibiotic classes, including β-lactams and aminoglycosides, to ensure representativeness of field-circulating isolates (Nataro and Kaper, 1998; Bai et al., 2016), while maintaining biosafety considerations.

(4) Cytotoxic potential: High cytotoxic potential in Vero cells, expressed as quantitative cytotoxicity titers determined by MTT assays, indicative of sufficient Stx2e antigen yield for vaccine production (Zheng et al., 2008).

A weighted ranking matrix was constructed to integrate these data, enabling prioritization of field-representative and antigen-productive strains suitable for vaccine seed development. The top-ranked strains were subsequently used for immunogen formulation and preclinical evaluation.

2.5 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses and data visualizations were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.0 (GraphPad Software, USA) and R version 4.3.0, incorporating packages such as tidyverse, ggplot2, FactoMineR, and factoextra. In Prism, nonlinear regression based on the Gompertz growth model was used to calculate growth parameters, including lag phase duration (LPD), exponential growth rate (EGR), and maximum population density (MPD). Dose–response cytotoxicity data were fitted using a four-parameter logistic (4PL) model to derive cytotoxicity titers. For group comparisons involving growth kinetics, cytotoxicity, virulence gene profiles, and antimicrobial resistance rates, one-way or two-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests were applied according to the distribution characteristics assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. Post-hoc analyses were conducted using Tukey’s or Dunn’s test, where appropriate. Additionally, multivariate statistical analyses were performed using R. Radar plots were generated to visualize multidrug resistance patterns across defined pathotype groups, while principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to evaluate clustering tendencies of isolates based on antimicrobial resistance traits and growth-associated parameters. Statistical differences were indicated using distinct letters or asterisks in figures (p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0005).

3 Results

3.1 Spatiotemporal distribution and anatomical origin of STEC isolates from Korean swine (2014–2025)

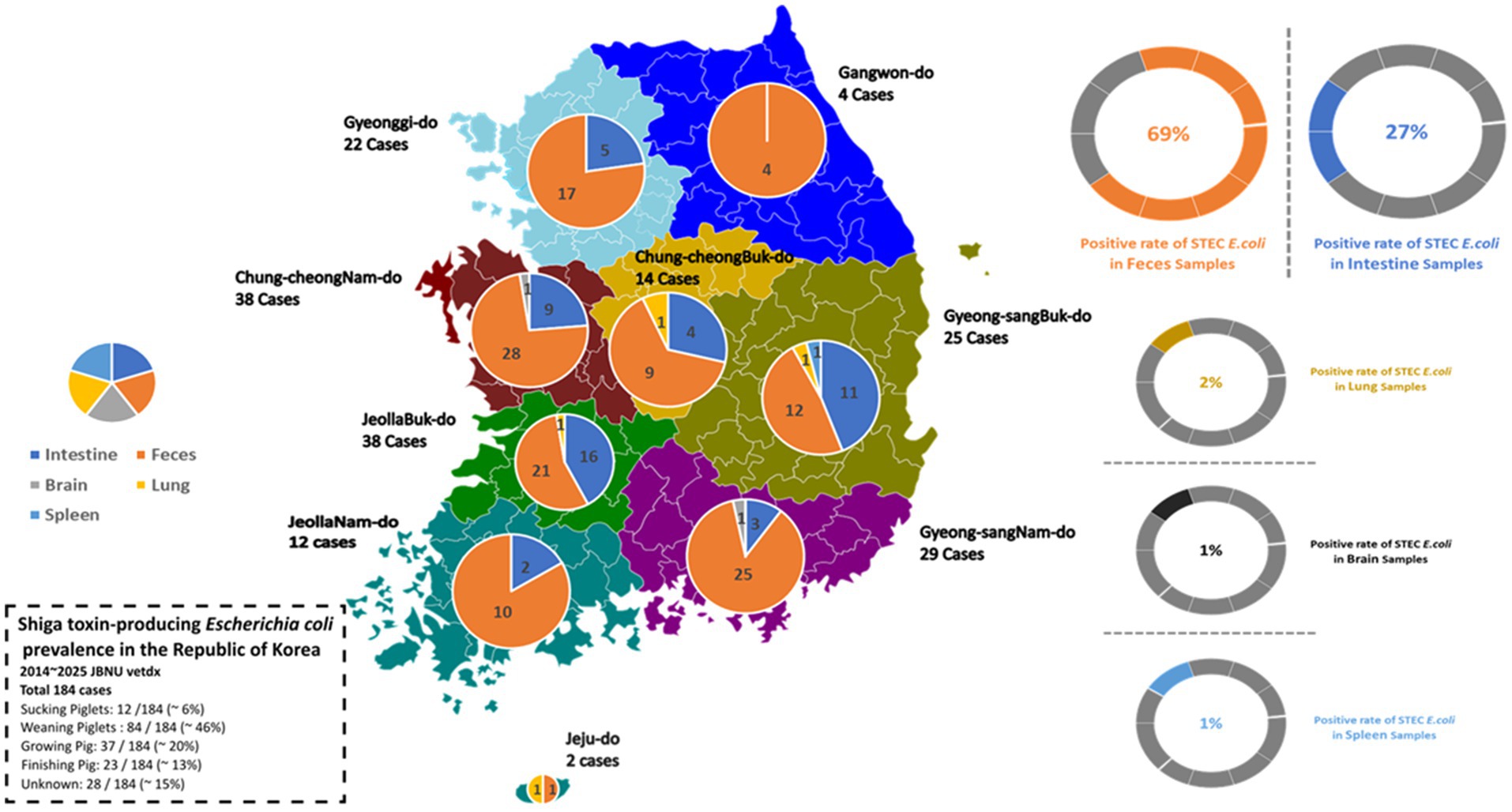

A total of 184 STEC isolates were recovered from porcine diagnostic submissions to the Jeonbuk National University Veterinary Diagnostic Center (JBNU-VDC) between 2014 and 2025. These cases originated from nine administrative provinces in the Republic of Korea, with the highest number reported from JeollaBuk-do (n = 38), ChungcheongNam-do (n = 38), and GyeongsangNam-do (n = 29). In contrast, Jeju-do and Gangwon-do account for the lowest number of STEC-positive cases (Figure 1). Based on anatomical classification, most isolates were recovered from fecal samples (69%), followed by the intestine (27%). Isolation from systemic organs such as the lung, brain, and spleen was infrequent (< 2% each), indicating that STEC infections in swine are predominantly localized to the gastrointestinal tract (Figure 1, right panel).

Figure 1. Regional and anatomical distribution of STEC isolates from Korean swine (2014–2025). A total of 184 STEC-positive cases were reported from nine provinces through diagnostic submissions to JBNU-VDC. Left: geographic case distribution by province. Right: anatomical classification, with feces identified as the most common sample type, followed by intestinal tissues. Isolates from lung, brain, and spleen were infrequent (<2% each).

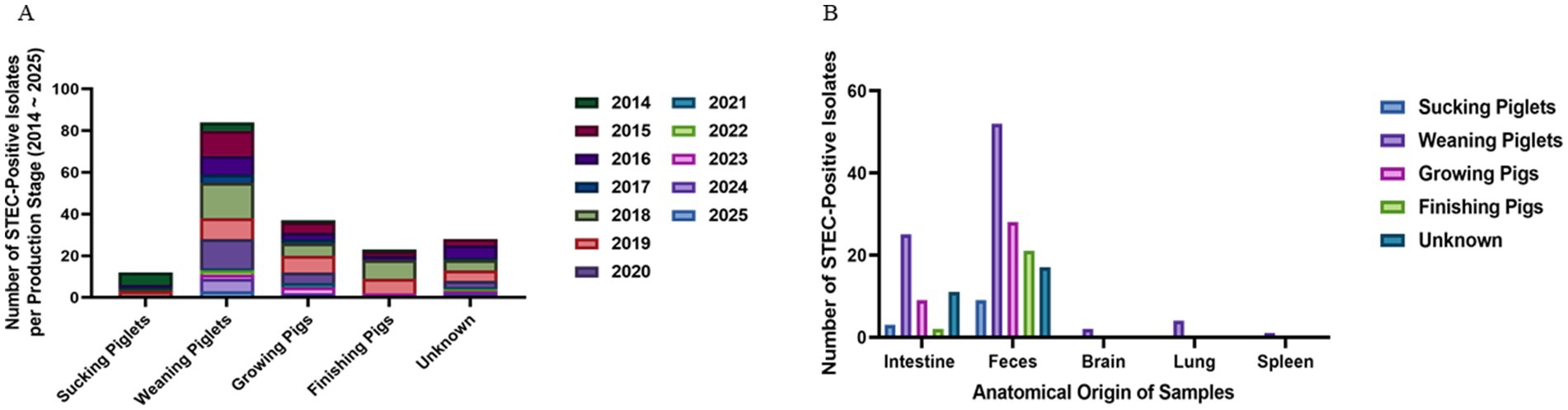

When Age-based analysis observed that weaning piglets (5–8 weeks of age) comprised the most frequently affected group (84/184; 45.7%), followed by growing pigs (9–16 weeks, 37/184; 20.1%), finishing pigs (17–25 weeks, 23/184; 12.5%), and suckling piglets (<4 weeks, 12/184; 6.0%) (Figure 2A). The annual distribution of cases within each production stage remained relatively stable throughout the study period. To investigate potential differences in anatomical sampling by production stage, specimen types were further categorized by age group. Fecal samples were predominant in weaning piglets, while older pigs were more often isolated from intestinal tissues rather than feces (Figure 2B). These patterns reflect both age-specific diagnostic submission cases.

Figure 2. Age-related distribution and sample type of STEC isolates. (A) Annual distribution of STEC isolates by pig production stage. Weaning piglets (5–8 weeks) were identified for the highest number of isolates throughout the study period, followed by growing and finishing pigs. (B) Anatomical source distribution by production stage. Fecal samples were the predominant source in weaning piglets, while intestinal tissue was more frequently sampled from growing and finishing pigs.

3.2 Genotypic characterization of virulence-associated genes and phylogenetic analysis in swine-derived STEC isolates

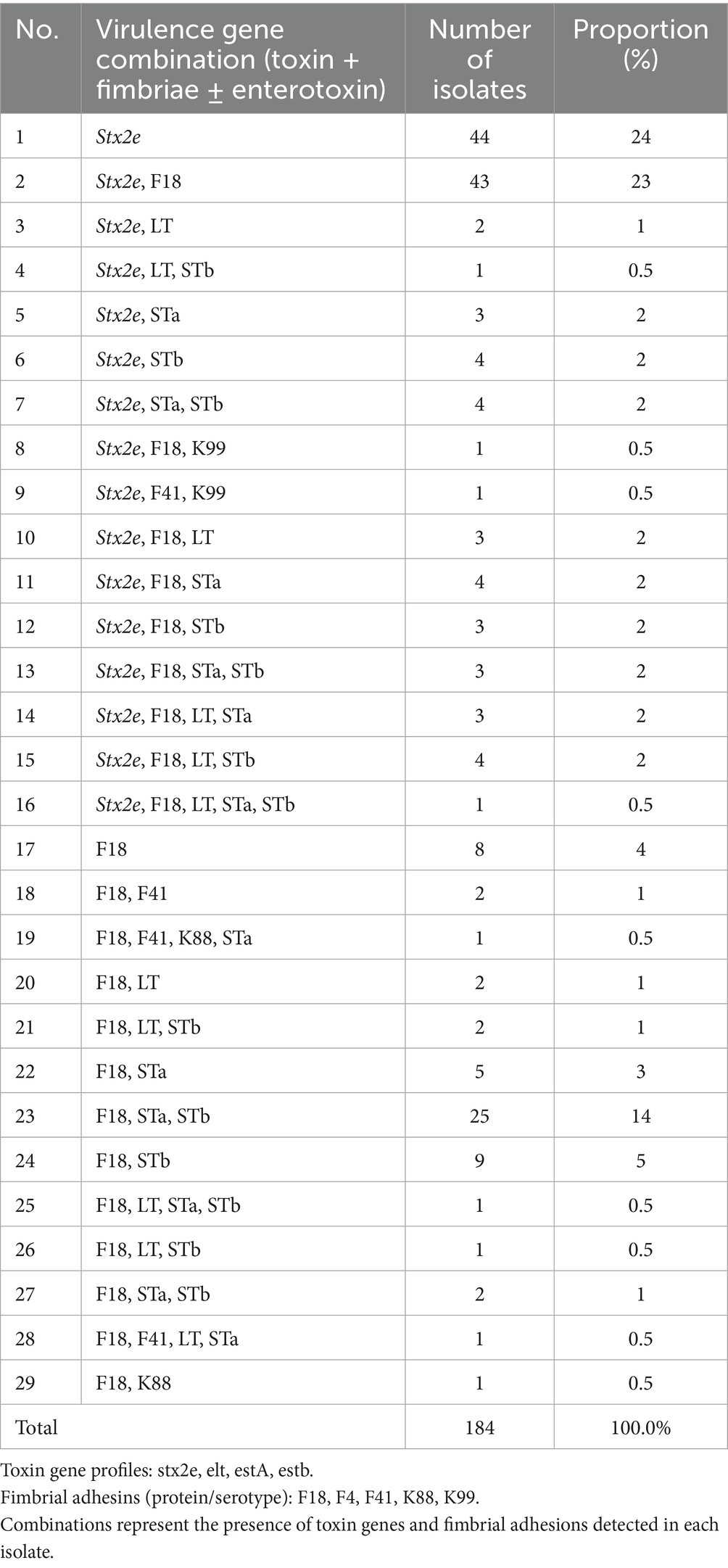

All 184 STEC isolates were genotyped for the presence of key virulence-associated genes, including stx2e, fimbrial adhesins, and enterotoxins. The most frequently detected genotype was stx2e alone (n = 44, 23.9), followed by co-detection of stx2e and F18 (n = 43, 23.4%). Additional virulence gene combinations involving STa, STb, and LT were observed in various constellations, often accompanying stx2e or F18. For example, isolates containing stx2e, F18, and both STa and STb were identified in 1.6% (n = 3) of the cases. Notably, 29 distinct virulence gene combinations were identified (Table 3), reflecting substantial heterogeneity among field isolates. Enterotoxins (LT, STa, STb) were more commonly associated with F18-positive strains than with stx2e-only isolates. Fimbrial variants such as F4, F5, and F41 were also sporadically detected in combination with stx2e or F18.

Table 3. Distribution of virulence gene combinations among swine-derived STEC isolates (n = 184) identified between 2014 and 2025.

The 16S rRNA analysis confirmed that both isolates (23–0932 and 24–0997) belong to the genus Escherichia. Strain 23–0932 showed close clustering with Shigella spp., while strain 24–0997 appeared near Salmonella enterica Ty2 within the Enterobacteriaceae clade. This pattern reflects the high 16S sequence similarity among these genera rather than taxonomic misclassification. Both strains exhibited >99% sequence identity with E. coli references, supporting their identification as E. coli (Supplementary Figure 1).

3.3 Functional characterization of representative STEC isolates based on phenotypic analysis

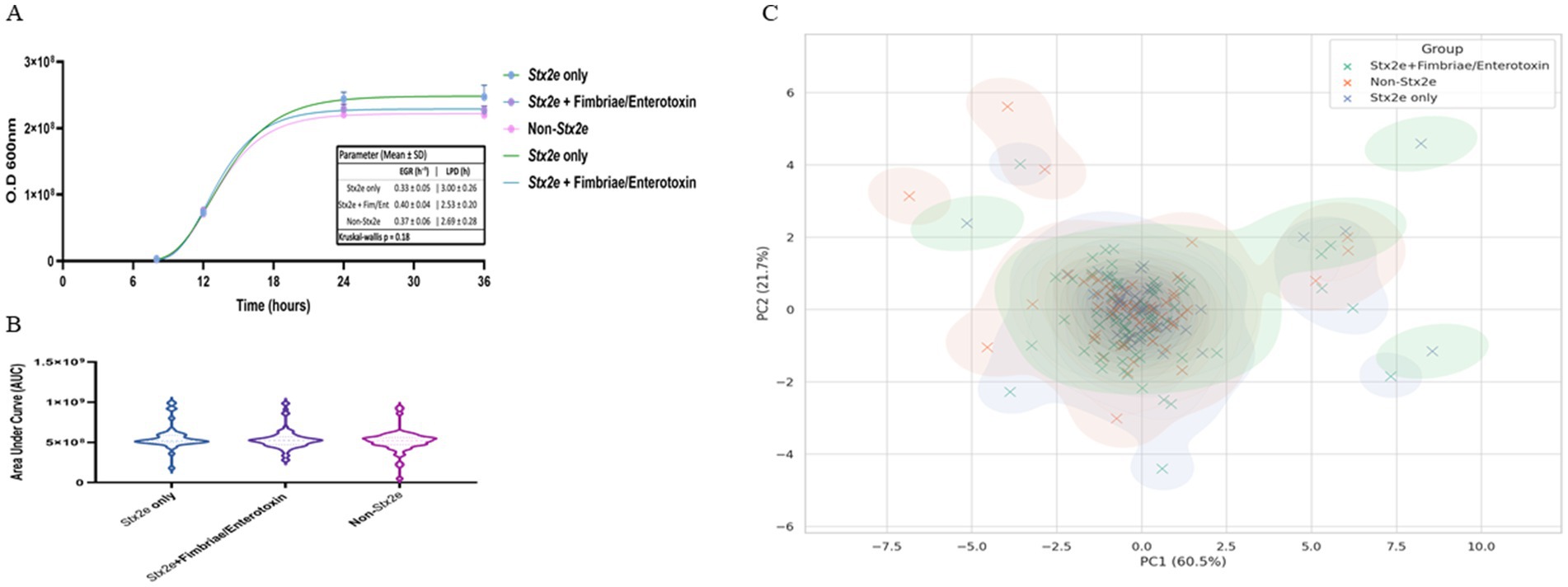

3.3.1 Comparative growth kinetics analysis of Stx2e-positive and Stx2e-negative isolates

To evaluate the in vitro growth characteristics of STEC isolates categorized by toxin gene profiles, we conducted a comparative kinetic analysis among three groups: Stx2e-only, Stx2e + fimbriae/enterotoxin, and non-Stx2e. Growth was monitored over 36 h at an optical density of 600 nm (OD₆₀₀), and corresponding area under the curve (AUC) and principal component analyses (PCA) were performed based on the growth parameters.

Growth curve analysis demonstrated typical sigmoid proliferation patterns in all three groups of STEC isolates. Across the early exponential phase (6–12 h), isolates classified as Stx2e-only showed a more rapid increase in optical density (OD₆₀₀) compared to the other groups. This trend was sustained through the stationary phase (post-12 h), where the Stx2e-only group reached a slightly higher maximal OD. The Stx2e + fimbriae/enterotoxin group exhibited a comparable growth trajectory but with slightly lower stationary phase, whereas non-Stx2e isolates demonstrated a delayed transition to exponential growth and a lower overall OD value. These findings suggest that the presence of Stx2e, particularly in the absence of additional colonization factors, may confer a marginal growth advantage under standardized in vitro conditions, possibly reflecting differences in metabolic burden or regulatory interactions associated with virulence gene expression (Figure 3A). The Gompertz model fitting (R2 = 0.71–0.83) revealed comparable overall growth kinetics among all pathotype groups. The Stx2e + fimbriae/enterotoxin group showed the highest estimated specific growth rate (EGR, K = 0.396 ± 0.040 h−1; 95% CI 0.270–0.406) and the shortest lag-phase duration (1/K = 2.53 ± 0.20 h). The Stx2e-only and non-Stx2e groups exhibited similar parameters (K = 0.334 ± 0.048 and 0.373 ± 0.057 h−1; 1/K = 3.00 ± 0.26 and 2.69 ± 0.28 h, respectively). No significant difference was observed among the groups (Kruskal–Wallis p = 0.18), consistent with the overlapping AUC distributions (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. In vitro growth dynamics and multivariate clustering of STEC isolates classified by toxin gene profile. (A) Representative growth curves of STEC isolates grouped as Stx2e-only, Stx2e + fimbriae/enterotoxin, and non-Stx2e, cultured in LB broth at 37 °C with shaking. Optical density (OD600) was measured over 36 h. Data points represent mean ± standard deviation (SD). Solid lines depict nonlinear regression fitting using the Gompertz growth model. Representative Gompertz growth curves of three STEC pathotypes. Mean ± SD growth parameters: EGR (h−1): Stx2e only 0.33 ± 0.05; Stx2e + Fim/Ent 0.40 ± 0.04; Non-Stx2e 0.37 ± 0.06; LPD (h): 3.00 ± 0.26, 2.53 ± 0.20, 2.69 ± 0.28, respectively (p = 0.18). Error bars represent mean ± SD from triplicate cultures. (B) Violin plots representing the distribution of area under the curve (AUC) values derived from growth kinetics for each pathotype group. Median values are indicated by central horizontal lines. Although no statistically significant differences were detected, the Stx2e-only group exhibited the highest median AUC. (C) Principal component analysis (PCA) of isolates based on three growth-related variables: AUC, maximal OD600, and calculated growth rate. The first and second principal components explain 60.5% and 21.7% of the variance, respectively. Each point represents an individual isolate, colored by group. Kernel density contours illustrate the overall distribution tendency of each group, showing partial clustering with overlapping patterns. Statistical analysis was performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison correction (n = 3 biological replicates per group).

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using three variables: area under the curve (AUC), maximal optical density (OD₆₀₀), and estimated growth rate. The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) explained 60.5 and 21.7% of the total variance, respectively. Distribution of isolates on the PCA plot showed partial group-wise clustering based on toxin profile. Most Stx2e-only isolates were distributed in the upper-right quadrant, while non-Stx2e isolates were spread across the lower-left and central regions. The Stx2e + fimbriae/enterotoxin group exhibited a broader distribution, overlapping with both other groups. No distinct separation among groups was observed, although the overall density contours showed differences in centroid positions and dispersion patterns (Figure 3C).

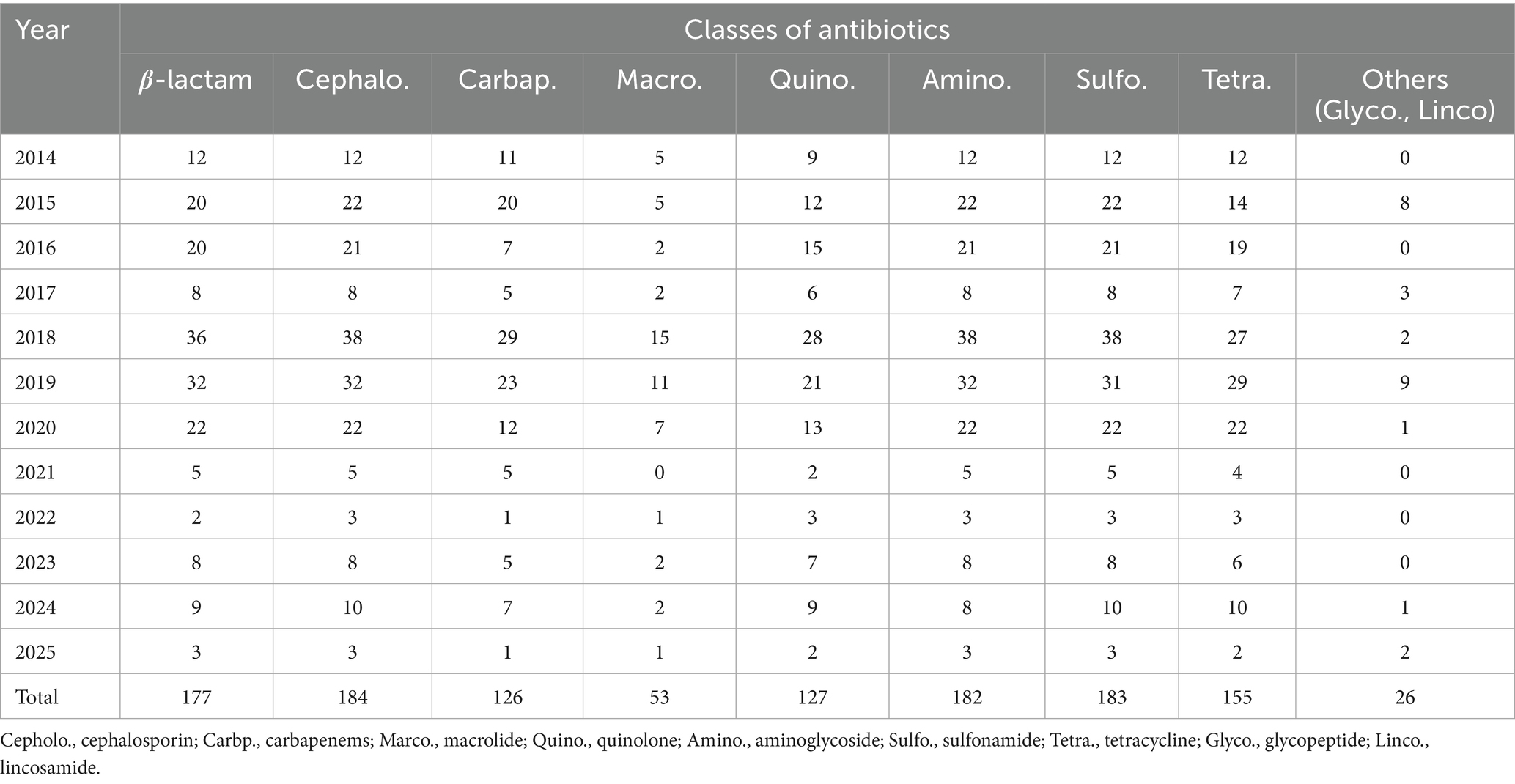

3.3.2 Antimicrobial resistance patterns of selected Stx2e-positive/negative isolates

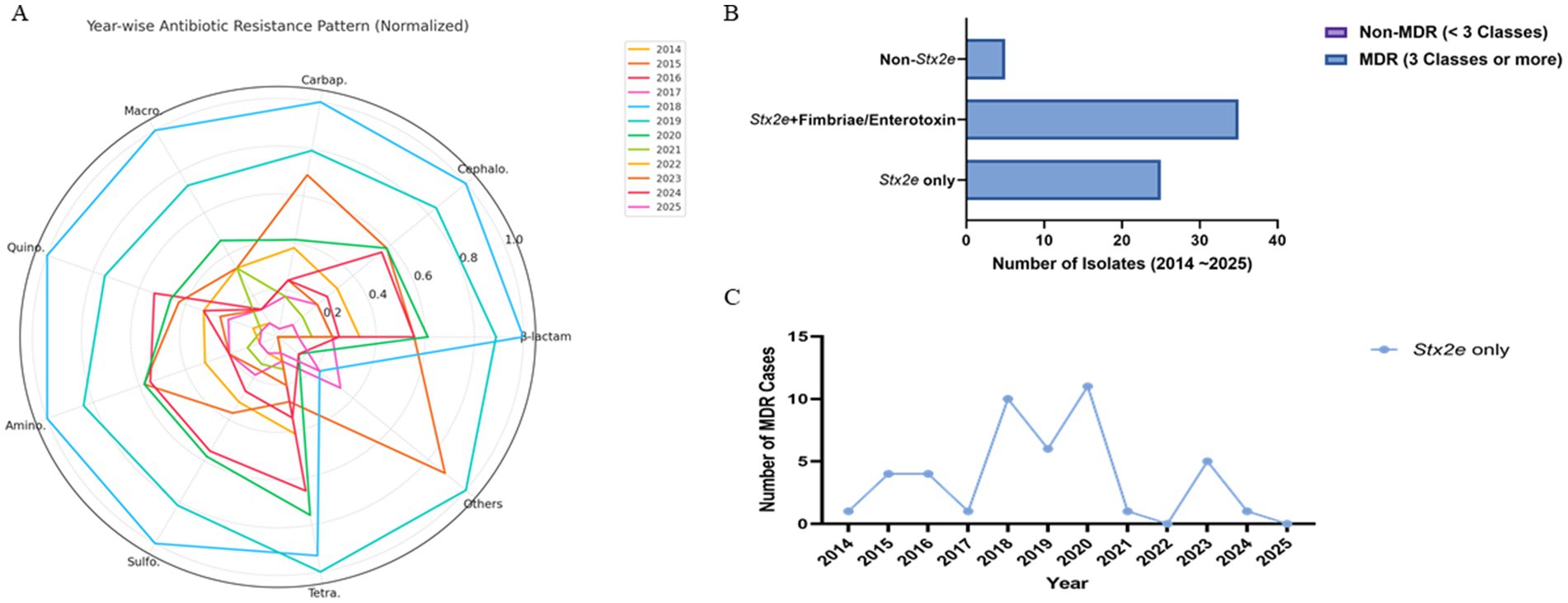

Antimicrobial resistance profiles were assessed across 184 STEC isolates collected from 2014 to 2025. A total of nine major antibiotic classes were considered, including β-lactams, cephalosporins, carbapenems, macrolides, quinolones, aminoglycosides, sulfonamides, tetracyclines, and others (glycopeptides and lincosamides). Among these, sulfonamides (n = 183), cephalosporins (n = 184), and aminoglycosides (n = 182) were the most frequently represented classes, followed by β-lactams (n = 177), tetracyclines (n = 155), and carbapenems (n = 126). Macrolide and quinolone resistance were observed in 53 and 127 cases, respectively. The cumulative resistance burden demonstrated a peak in 2019–2020, particularly for β-lactams, sulfonamides, and cephalosporins. Resistance to at least five or more classes was common from 2018 through 2020 (Table 4). When visualized by year and normalized per class, β-lactam, sulfonamide, and aminoglycoside resistance were consistently dominant. Carbapenem and cephalosporin resistance remained widespread from 2015, while macrolide and quinolone resistance fluctuated year to year with an uptick during 2018–2020 (Figure 4A).

Table 4. Year-wise distribution of detected antibiotic resistance classes among STEC isolates (2014–2025).

Figure 4. Antimicrobial resistance patterns of STEC isolates stratified by toxin gene profile and sampling year. (A) Radar plot visualizing the normalized distribution of detected antibiotic resistance classes from 2014 to 2025. Each axis represents a distinct antimicrobial class, and year-specific resistance levels are plotted as scaled values (0–1) relative to the highest observed class-level frequency. Yearly denominators (n = 12, 15, 19, 21, 24, 23, 18, 17, 14, 13, 8, 5) are indicated in parentheses for each year. A consistent presence of B-lactam, cephalosporin, and sulfonamide resistance was observed across years, with peaks in 2018–2020, driven primarily by isolates harboring Stx2e. (B) Stacked bar chart showing MDR (23 classes) and non-MDR (<3 classes) counts per group. Non-MDR counts were zero in both Stx2e-positive groups; the non-Stx2e group included predominantly non-MDR isolates (numerical labels shown on bars). (C) Yearwise trend in the number of MDR isolates identified within the Stx2e only group. While temporal fluctuation was observed, peak MDR occurrence was noted between 2018 and 2020, followed by a gradual decline. Data are presented as descriptive, exploratory visualizations; statistical comparisons were not adjusted for multiple testing, consistent with field-level AMR trend analysis in veterinary surveillance. Data represent descriptive, exploratory visualizations; statistical comparisons were not adjusted for multiple testing.

Multidrug resistance (MDR), defined as resistance to three or more antimicrobial classes, was predominantly observed in Stx2e-only and Stx2e + fimbriae/enterotoxin isolates. A total of 36 MDR isolates were identified in the Stx2e + fimbriae/enterotoxin group, while 23 MDR isolates were detected in the Stx2e-only group. In contrast, the non-Stx2e group accounted for only three MDR cases, with the remaining isolates classified as non-MDR. Among the Stx2e-positive isolates, all strains met the MDR definition (≥3 antimicrobial classes), although the degree and spectrum of resistance varied by group (Figure 4B). Temporal profiling of MDR among Stx2e-only isolates revealed persistent detection from 2014 to 2021. A sharp increase in MDR prevalence occurred in 2018–2020, with 10–12 MDR cases annually, followed by a decrease in MDR cases in 2022–2025 (Figure 4C). These phenotypic resistance results represent disc-diffusion screening under field-level conditions. Carbapenem and cephalosporin resistance patterns indicate reduced inhibition-zone responses rather than confirmed enzymatic resistance. Representative isolates will be subjected to MIC testing and β-lactamase/carbapenemase genotyping in follow-up validation.

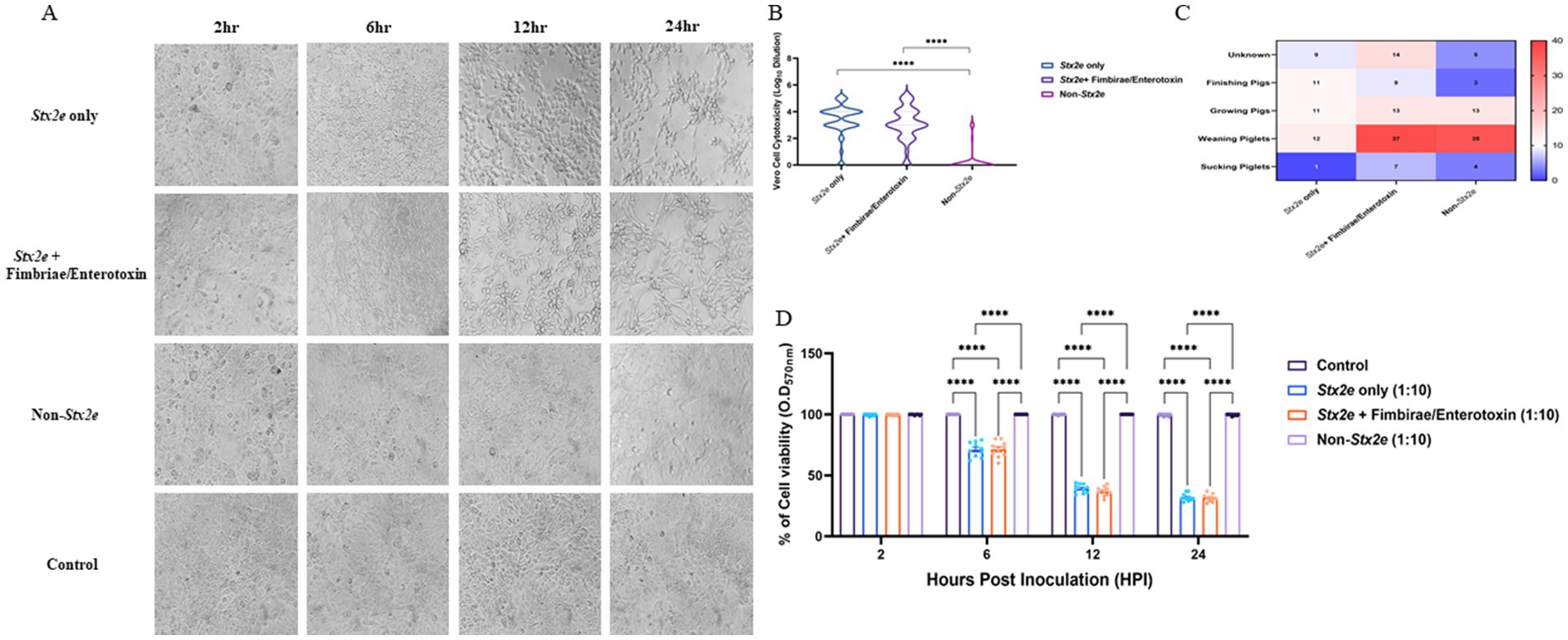

3.3.3 Quantitative cytotoxicity profiles assessed by Vero cell assay

Cytotoxic effects of selected STEC isolates were evaluated using a Vero cell-based MTT assay. Characteristic morphological alterations—such as cell shrinkage and detachment—were observed at 2-, 6-, 12-, and 24 h post-exposure (Figure 5A). Isolates containing the stx2e gene induced earlier and more pronounced cytopathic effects than the non-Stx2e group. Both Stx2e-positive groups, Stx2e-only, Stx2e + fimbriae/enterotoxin, exhibited significantly higher cytotoxic activity than the non-Stx2e group, as determined by the highest dilution factor resulting in a 50% reduction in cell viability (log10 scale). The Stx2e-only group showed a significantly (p < 0.0005) higher median cytotoxicity compared to the non-Stx2e group; however, the difference was not statistically significant compared to the Stx2e + Fimbriae/Enterotoxin group (Figure 5B). To investigate age-related patterns, a heatmap analysis was constructed to visualize the distribution of virulence groups across the pig production stages (Figure 5C). Quantitative absorbance data (OD570) from the MTT assay were also analysed to assess time-dependent cytotoxic responses across the three virulence categories (Figure 5D). These results complemented time-based cytotoxicity assessments and demonstrated that Stx2e-positive isolates showed significantly higher cytotoxicity compared to the non-Stx2e group. Stx2e-positive groups exhibited significantly higher cytotoxicity than non-Stx2e isolates (p < 0.0005), supporting that the assay reflects functional Stx2e activity relevant to vaccine strain evaluation rather than purified toxin characterization.

Figure 5. Cytotoxic effects of STEC isolates on Vero cells. (A) Morphological changes in Vero cells exposed to selected STEC isolates at 2-, 6-, 12-, and 24-hours post-exposure. Characteristic cytopathic effects including cell shrinkage and detachment were observed with earlier and more pronounced effects inisolates identified the stx2e gene compared to non-stx2e isolates. (B) Cytotoxic activity measured as the highest dilution factor causing 50% reduction in Vero cell viability (logio scale). Stx2e-positive groups demonstrated significantly greater cytotoxicity compared to the non-stx2e group (p < 0.0005). The stx2e-only group exhibited the highest median cytotoxic effect. (C) Distribution of STEC virulence groups across different pig production stages, showing predominance of stx2e-positive isolates at all ages. (D) Time-course analysis of cytotoxicity measured by MTT assay demonstrating significantly higher cytotoxic effects of stx2e-positive isolates compared to non-stx2e groups over 24 hours. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test (n= 3 independent experiments per group). ****p< 0.0001.

3.4 Comparative genomic and clonal structuring of representative STEC isolates

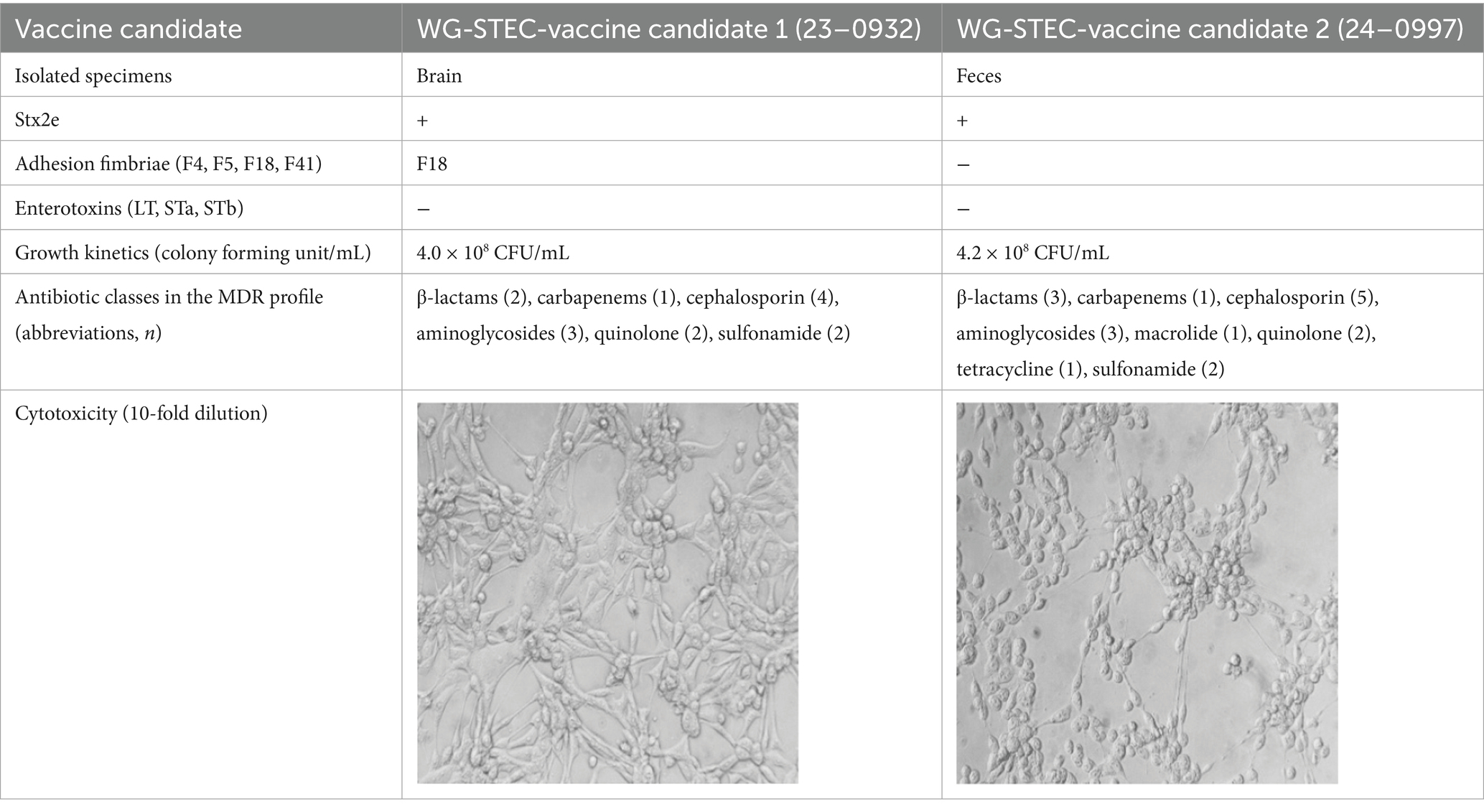

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) was performed on two representative E. coli strains—23-0932 and 24-0997—selected based on their virulence gene profiles, toxin production levels, and in vitro growth characteristics. The circular genomic maps of both isolates were visualized to compare gene architecture, GC content, GC skew, and the distribution of virulence and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes (Figures 6A,B). Strain 23-0932 (genome size: 3,237,462 bp) displayed a compact core genome and clustered virulence-associated regions. Key virulence genes, including stx2e, eae, and fimH, were found adjacent to pathogenicity islands and flanked by mobile genetic elements. Notably, the eae gene is located within a partial Locus of Enterocyte Effacement (LEE) region, which is unusual for classical porcine Stx2e/ED isolates that are typically eae–. This arrangement may confer some potential for intimate adherence to intestinal epithelial cells, suggesting atypical pathogenic features in 23-0932. In-depth genomic context analysis confirmed that eae in strain 23-0932 is embedded within a partial but distinct LEE-like locus, flanked by mobile genetic elements. Although incomplete compared to canonical LEE islands observed in enteropathogenic E. coli, this architecture implies a potential for attaching and effacing (A/E)-like adherence. The presence of eae within such a genomic environment indicates that strain 23-0932 may represent an atypical evolutionary lineage of porcine Stx2e isolates, likely derived through horizontal gene transfer. This observation highlights the emergence of non-classical Stx2e/ED variants that may possess enhanced virulence plasticity or altered host-adaptation potential. Multiple antimicrobial resistance determinants, such as tetA and sul1, were detected in the outer ring annotations, suggesting horizontal gene transfer events. In contrast, strain 24-0997 (genome size: 3,338,514 bp) exhibited a more expansive genomic architecture, featuring multiple insertion sequences and transposase elements dispersed throughout the genome. Although both strains contained stx2e, their surrounding genomic context differed substantially, with 24-0997 exhibiting additional copies of fimH operons and an increased number of hypothetical proteins adjacent to known virulence loci. Both isolates showed balanced GC-skew distributions (innermost circle), with slight deviations near regions enriched in prophage-like elements. The overall GC content (outer second ring) was consistent with E. coli norms, averaging ~50.6%. Notably, the AMR gene content was more diverse in 23-0932, while 24-0997 carried multiple adhesin-related genes and unique secretion system components.

Figure 6. Circular genome visualization of two representative Escherichia coli isolates selected as vaccine candidates. (A) Genome map of E. coli 23–0932 (3,237,462,650 bp) showing core genes (CDS), virulence factors, antimicrobial resistance genes (AMR), GC content, and GC skew. (B) Genome map of E. coli 24–0997 (3,338,514,266 bp) with annotated virulence loci and mobile elements. The inner rings depict GC content (orange) and GC skew (positive in black, negative in grey), while the outermost annotations denote virulence-associated genes (green), AMR genes (red), and hypothetical proteins (blue). Gene classification was performed using Prokka and ABRicate pipelines and visualized using CGView.

3.5 Multi-parameter selection of vaccine candidate strains

A total of 184 E. coli isolates were screened for the presence of the Stx2e gene to identify suitable vaccine candidate strains. Among these, Stx2e-positive isolates were prioritized due to their established role in edema disease pathogenesis. The Stx2e-only strains demonstrated significantly improved growth characteristics, including shorter lag phases, higher exponential growth rates, and increased maximum population densities, compared to strains harboring additional virulence factors. These findings indicate that Stx2e-only strains possess relatively high proliferation capacity, advantageous for large-scale vaccine antigen production, but also that Stx2e + fimbriae/enterotoxin strains exhibited high growth performance. In addition, the antimicrobial susceptibility testing revealed that a substantial proportion of Stx2e-only and Stx2e + fimbriae/enterotoxin strains exhibited multidrug resistance to most antibiotic classes. Therefore, to reflect the antimicrobial resistance profiles of circulating field strains, candidate strains displaying representative multidrug resistance profiles were selected to enhance vaccine relevance to circulating field strains. In vitro cytotoxicity assessed by the Vero cell MTT assay showed that both Stx2e-only and Stx2e + fimbriae/enterotoxin strains induced significantly higher cytotoxicity than non-Stx2e strains (Table 5).

4 Discussion

Through the spatiotemporal (2014–2025) nationwide surveillance of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC), the diverse molecular epidemiology and characteristics were identified in the Republic of Korea. A total of 184 STEC isolates were characterized, with most recovered from gastrointestinal specimens, especially feces and intestinal tissues, reflecting a localized enteric infection pattern. This finding aligns with known clinical signs of STEC-related diseases in piglets, such as post-weaning diarrhea (PWD) and edema disease (ED), where the pathogen colonizes the small intestine and secretes potent toxins that induce systemic and local effects (Fairbrother et al., 2005). In addition, the weaning phases (5–8 weeks of age) of pig production stage were susceptible to STEC-infection complied with dietary changes, and an immature immune system as previously described (Madec et al., 2000). This emphasizes the urgent need for effective preventive strategies, including an appropriate time point of sows or suckling piglets, for vaccination.

In the genetic and molecular profiling of STEC isolates, 29 unique virulence gene combinations, including stx2e, F18 fimbriae, and enterotoxins such as LT, STa, and STb, were detected. Among them, the Stx2e and Stx2e + F18 genotypes were the most prevalent, indicating that these variants may be more frequently associated with edema diseases, colibacillosis, or other diseases (Baldo et al., 2020). Growth kinetics and PCA analyses based on toxin gene profiles revealed that Stx2e-only isolates exhibited relatively higher growth rates compared to other groups. This enhanced proliferative capacity was also distinguishable in the principal component space, suggesting a distinct growth kinetics associated with the absence of additional virulence gene factors. These findings may reflect a lower metabolic burden or altered regulatory dynamics in strains harboring stx2e-only, enabling more efficient proliferation under in vitro conditions (Kaper et al., 2004; Bai et al., 2016; Lim et al., 2010). This property could be considered favorable when selecting live-attenuated vaccine candidates, provided that virulence attenuation is concurrently validated.

The comparative whole-genome analysis of two representative E. coli isolates, 23-0932 and 24-0997, revealed notable genomic divergence despite sharing key virulence determinants, such as stx2e. The genomic organization patterns, presence of accessory gene clusters, and integration of mobile genetic elements indicated distinct evolutionary lineages, likely shaped by host-driven selective pressures and horizontal gene transfer (Zingali et al., 2020). Strain 23-0932 exhibited a more consolidated virulence profile, characterized by the presence of the eae gene located near pathogenicity-associated regions, although no complete LEE island was detected. This configuration suggests a potential for attaching and effacing–like interactions in porcine intestinal cells. In addition, the co-localization of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and virulence determinants within genomic regions containing tRNA integration hotspots implies that horizontal gene transfer mediated by bacteriophages or plasmids may have contributed to this organization (Heo et al., 2020; Bai et al., 2016; Hacker and Kaper, 2000). Such genomic architecture supports the adaptive evolution of strain 23-0932 under antimicrobial selection pressures commonly encountered in pig production environments, while maintaining the Stx2e-dominant pathogenic mechanism characteristic of edema disease. In contrast, strain 24-0997 exhibited an expanded genomic structure, characterized by the presence of insertion sequences and unique adherence factors. This architectural complexity may reflect a broader metabolic or ecological niche, allowing the strain to persist under diverse gut microenvironments or environmental reservoirs (Kalalah et al., 2024). The presence of multiple adhesin systems and secretion-associated proteins also suggests a potential advantage in epithelial colonization, particularly under stress-induced gut permeability conditions common in weanling piglets. Interestingly, both strains maintained relatively conserved GC-skew patterns, supporting their genomic stability despite the insertion of foreign elements as previously described (Rocha, 2004). However, the distribution of hypothetical proteins adjacent to virulence loci in 24-0997 suggests unexplored functional diversity that may impact host-pathogen interaction or immune evasion mechanisms. Taken together, these results indicate that even within a single virulence genotype group (i.e., stx2e-positive STEC), significant genomic heterogeneity exists, which may influence vaccine design and efficacy (Brazzoli et al., 2023). The strain-specific genomic features identified here support the rationale for a multi-strain vaccine approach or the development of conserved antigen-based subunit vaccines targeting shared virulence determinants.

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiling of Stx2e-positive isolates revealed a high prevalence of multidrug resistance (MDR), with the majority of strains exhibiting resistance to at least three or more antimicrobial classes. Resistance was most frequently detected against tetracyclines, β-lactams (notably ampicillin), and sulfonamides—antimicrobial agents commonly used in swine production. This pattern aligns with international surveillance reports documenting similar resistance trends among porcine E. coli isolates, particularly those associated with post-weaning diarrhea and edema disease (Do et al., 2020; Ahmed and Shimamoto, 2015). The sustained exposure of field strains to selective antimicrobial pressure may have driven the accumulation of horizontally acquired resistance determinants, often located on mobile genetic elements such as plasmids and integrons (Ahmed and Shimamoto, 2015; Zhao et al., 2001). The near-complete absence of non-MDR isolates among Stx2e-harboring strains is particularly concerning, as it suggests that virulence and resistance traits are frequently co-localized, potentially amplifying clinical and epidemiological risks in affected herds. In the absence of effective countermeasures, the spread of MDR Stx2e strains could compromise treatment outcomes, exacerbate disease severity, and increase economic losses due to reduced growth performance and prolonged recovery periods (Mir and Kudva, 2019). In the veterinary field context, such multidrug resistance reflects cumulative selective pressure from farm-level antimicrobial use rather than therapeutic exposure alone (Daodu et al., 2025). These phenotypic profiles serve as epidemiological indicators for selecting representative vaccine seed strains under field conditions, emphasizing that the AMR analysis in this study was designed for vaccine development relevance rather than clinical MIC determination.

In Vero cell-based cytotoxicity assays, Stx2e-positive isolates consistently induced pronounced morphological changes and significant reductions in cell viability compared to non-Stx2e strains. The Stx2e-only group exhibited the most severe effects at early time points. Importantly, all isolates tested for cytotoxicity were previously confirmed to carry the stx2e gene by PCR, supporting the interpretation that observed effects predominantly reflect Stx2e activity. We acknowledge that Vero cell assays are not fully Stx2e-specific, and future studies are planned to include orthogonal confirmation, such as neutralization with anti-Stx2e antibodies and Gb4/Gb5 receptor competition assays. Notably, a subset of Stx2e-only isolates maintained strong cytotoxic potential despite lacking F18 fimbriae, suggesting the involvement of alternative virulence mechanisms capable of mediating host cell damage. These results highlight Stx2e as a key functional immunogen, independent of traditional colonization factors, and support its inclusion in vaccine antigen design (Tozzoli et al., 2014). In veterinary vaccinology, such functional correlation between stx2e genotype and Vero cytotoxicity provides a practical and ethically sustainable criterion for field strain selection before confirmatory toxin-neutralization or receptor-binding assays are undertaken in subsequent antigen validation studies.

Currently available vaccines for edema disease in swine largely target F18-positive strains, primarily through fimbrial or toxoid-based formulations. However, field reports increasingly describe the emergence of Stx2e-producing STEC isolates that lack F18 or harbor divergent virulence gene profiles, often correlating with suboptimal vaccine efficacy or clinical outbreaks in immunized herds (Baldo et al., 2020). Such strains have been recovered across all production stages, suggesting an expanding antigenic diversity that is inadequately addressed by existing vaccine platforms (Kim et al., 2010; Makino et al., 2001). This underscores the urgent need for broadened immunogen selection strategies that prioritize conserved toxins such as Stx2e lineage-specific colonization antigens, especially in regions with high genetic variability among circulating STEC isolates (Baranzoni et al., 2016; Galarce et al., 2019).

To address this, an integrated evaluation framework was applied to identify candidate vaccine strains that reflect both field relevance and production feasibility. Two representative Stx2e-positive isolates were selected based on a composite scoring system incorporating virulence profile, in vitro growth performance, cytotoxicity, and antimicrobial resistance. These strains demonstrated strong and stable proliferation (>4.0 × 108 CFU/mL), high cytotoxicity (105 titer), and multidrug resistance patterns consistent with those observed in the broader strain collection. One of the selected isolates carried the F18 fimbrial gene, while the other did not, thereby providing complementary antigenic coverage. This dual-candidate approach ensures a more comprehensive immunological response while maintaining manufacturing compatibility, offering a rational and scalable strategy for next-generation vaccine development against edema disease in swine. Furthermore, both candidate strains exhibited consistent in vitro phenotypic profiles across multiple passages, indicating preliminary stability at the functional level. This phenotypic reproducibility complements the genomic evidence of stability derived from WGS analyses. To ensure long-term reliability of the vaccine seed strains, serial passage and in vivo stability testing will be conducted in subsequent development stages. Based on these results, efforts are currently underway to formulate and evaluate multiple vaccine platforms, including toxoid-based, recombinant subunit, exosome-based, and inactivated vaccine formulations, leveraging the antigenic potential of selected strains to provide robust protection against a broader spectrum of field-circulating STEC. This approach, supported by integration of molecular, phenotypic, virotype, and epidemiological results, enabled the selection of vaccine candidates that not only exhibit strong immunological potential but also align with the practical demands of large-scale production and implementation. Future work will focus on pilot-scale vaccine development, in vivo efficacy testing, and field application trials to validate safety, immunogenicity, and impact on disease prevalence and antimicrobial usage in swine farms.

5 Conclusion

Through a nationwide molecular epidemiological surveillance spanning 2014 to 2025, this study characterized the virulence gene diversity, antimicrobial resistance, and in vitro phenotypes of porcine Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) isolates circulating in Korea. The predominance of Stx2e-positive strains, coupled with the detection of highly heterogeneous virulence gene constellations—including both F18-positive and F18-negative genotypes—highlights the evolving antigenic landscape of field strains and the challenges it poses to current vaccine strategies. The widespread occurrence of multidrug resistance (MDR) among toxin-containing isolates further emphasizes the urgency of developing effective non-antibiotic interventions. By integrating genotypic and phenotypic datasets, two representative Stx2e-positive isolates were selected as rational vaccine candidates based on their strong cytotoxicity, high in vitro proliferation capacity, cell cytotoxicity, and relevant antimicrobial resistance profiles. Notably, the evaluation of both F18-positive and F18-negative isolates allowed for the identification of a vaccine candidate with broader antigenic representativeness, addressing the limitations of current vaccine formulations. This selection strategy, supported by a nationwide longitudinal surveillance dataset spanning 2014–2025, offers a rational and evidence-based foundation for the development of next-generation immunogens against porcine edema disease. The selected candidate strains are currently under evaluation across multiple vaccine platforms, including toxoid-based, recombinant subunit, exosome-derived, and inactivated vaccine formulations, designed to align with the production parameters and epidemiological landscape of the Korean swine industry. This strategy constitutes a data-driven framework for non-antibiotic disease control, aiming to reduce STEC-associated clinical and economic burdens through immunologically relevant and manufacturing-compatible vaccine solutions.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are included in the article and its supplementary material. Additional data will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because ethical approval was not required for this study because no experimental procedures were performed on live animals. The work was based solely on bacterial isolates and archived clinical samples that had been previously collected by licensed veterinarians for diagnostic purposes. No prospective sampling, invasive procedures, or experimental use of animals was involved. Written informed consent was not obtained from the owners for the participation of their animals in this study because written informed consent was not obtained because the study did not involve any prospective or experimental procedures on animals. The samples used were collected previously by veterinarians during routine diagnostic procedures, with owners’ verbal agreement for their use in diagnostic and research purposes. Therefore, no additional written consent was required.

Author contributions

G-SP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. H-JK: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MC: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. S-CK: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. C-GJ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. J-HR: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. WK: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. HL: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. J-GK: Writing – review & editing. BJ: Resources, Writing – review & editing. MK: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. CK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. W-IK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. BS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by a grant (2024_IK-A_1) from the ‘Jeonbuk Advanced Bio Research & Development’ program funded by Jeonbuk Province in the Republic of Korea.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank the laboratory technicians at the Veterinary Diagnostic Center of Jeonbuk National University (VDC-JBNU) and Korea Research Institute for Veterinary Biologics (KRIVB) for their constant assistance throughout the study.

Conflict of interest

This study was conducted as a collaborative effort between industry and academia, involving WOOGENE B&G Co., Ltd., Veterinary Diagnostic Center (Jeonbuk National University), and the Korea Research Institute for Veterinary Biologics (KRIVB).

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1701708/full#supplementary-material

References

Ahmed, A. M., and Shimamoto, T. (2015). Molecular analysis of multidrug resistance in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157: H7 isolated from meat and dairy products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 193, 68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.10.014,

Al-Balawi, M., and Morsy, F. M. (2021). Prenatal versus postnatal initial colonization of healthy neonates’ colon ecosystem by the enterobacterium Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 9:e00379-21. doi: 10.1128/Spectrum.00379-21,

Bai, L., Hurley, D., Li, J., Meng, Q., Wang, J., Fanning, S., et al. (2016). Characterisation of multidrug-resistant Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli cultured from pigs in China: co-occurrence of extended-Spectrum Β-lactamase-and Mcr-1-encoding genes on plasmids. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 48, 445–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.06.021,

Baldo, V., Salogni, C., Giovannini, S., D'Incau, M., Boniotti, M. B., Birbes, L., et al. (2020). Pathogenicity of Shiga toxin type 2e Escherichia coli in pig colibacillosis. Front. Vet. Sci. 7:545818. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.545818,

Baranzoni, G. M., Fratamico, P. M., Gangiredla, J., Patel, I., Bagi, L. K., Delannoy, S., et al. (2016). Characterization of Shiga toxin subtypes and virulence genes in porcine Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 7:574. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00574,

Berger, P. I., Hermanns, S., Kerner, K., Schmelz, F., Schüler, V., Ewers, C., et al. (2023). Cross-sectional study: prevalence of Oedema disease Escherichia coli (EDEC) in weaned piglets in Germany at pen and farm levels. Porcine Health Manag. 9:49. doi: 10.1186/s40813-023-00343-9,

Beutin, L., Zimmermann, S., and Gleier, K. (2002). Evaluation of the VTEC-screen “Seiken” test for detection of different types of Shiga toxin (verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) in human stool samples. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 42, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(01)00325-X,

Braz, V. S., Melchior, K., and Moreira, C. G. (2020). Escherichia coli as a multifaceted pathogenic and versatile bacterium. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10:548492. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.548492,

Brazzoli, M., Piccioli, D., and Marchetti, F. (2023). Challenges in development of vaccines directed toward antimicrobial resistant bacterial species. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 19:2228669. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2023.2228669,

Cho, S.-Y., Yu, J. H., Yu, Y. J., Lee, H.-J., and Hur, J. (2023). Prevalence of antibody and toxin against edema disease from pig farms in Jeonbuk province. Korean J. Vet. Serv. 46, 325–334. doi: 10.7853/kjvs.2023.46.4.325

da Silva, C. R., Sanches, M. S., Macedo, K. H., Dambrozio, A. M. L., da Rocha, S. P. D., Navarro, A., et al. (2019). Molecular and phenotypic characterization of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli isolated from groundwater in rural areas in southern Brazil. J. Water Health 17, 597–608. doi: 10.2166/wh.2019.142,

Daodu, O. B., Olusegun, E. G., Adegbehingbe, G., Komolafe, S. E., and Daodu, O. C. (2025). Barriers to effective antimicrobial resistance management in Nigerian livestock: the role of veterinary practices and client expectations. BMC Vet. Res. 21:255. doi: 10.1186/s12917-025-04710-2,

Do, K.-H., Byun, J.-W., and Lee, W.-K. (2019). Prevalence of O-serogroups, virulence genes, and F18 antigenic variants in Escherichia coli isolated from weaned piglets with diarrhea in Korea during 2008–2016. J. Vet. Sci. 20, 43–50. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2019.20.1.43,

Do, K.-H., Byun, J.-W., and Lee, W.-K. (2020). Virulence genes and antimicrobial resistance of pathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from diarrheic weaned piglets in Korea. J. Anim. Sci. Techno. 62, 543–552. doi: 10.5187/jast.2020.62.4.543,

Eriksen, E., Kudirkiene, E., Christensen, A., Agerlin, M., Weber, N., Nødtvedt, A., et al. (2021). Post-weaning diarrhea in pigs weaned without medicinal zinc: risk factors, pathogen dynamics, and association to growth rate. Porcine Health Manag. 7:54. doi: 10.1186/s40813-021-00232-z,

Fairbrother, J. M., Nadeau, É., and Gyles, C. L. (2005). Escherichia coli in postweaning diarrhea in pigs: an update on bacterial types, pathogenesis, and prevention strategies. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 6, 17–39. doi: 10.1079/AHR2005105,

Galarce, N., Escobar, B., Sánchez, F., Paredes-Osses, E., Alegría-Morán, R., and Borie, C. (2019). Virulence genes, Shiga toxin subtypes, serogroups, and clonal relationship of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from livestock and companion animals. Animals 9:733. doi: 10.3390/ani9100733,

Gannon, V., Gyles, C. L., and Wilcock, B. P. (1989). Effects of Escherichia coli Shiga-like toxins (verotoxins) in pigs. Can. J. Vet. Res. 53:306,

Gao, S., Liu, X., Zhang, R., Jiao, X., Wen, Q., Wu, C., et al. (1999). The isolation and identification of pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates of chicken origin from some regions in China. Acta Vet. Zootech. Sin. 30, 164–171.

Hacker, J., and Kaper, J. B. (2000). Pathogenicity islands and the evolution of microbes. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 54, 641–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.641,

Heo, E. J., Ko, E. K., Kang, H. J., Kim, Y. J., Park, H. J., Wee, S.-H., et al. (2020). Prevalence and antimicrobial characteristics of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates from pork in Korea. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 17, 602–607. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2019.2760,

Holmer, I., Salomonsen, C. M., Jorsal, S. E., Astrup, L. B., Jensen, V. F., Høg, B. B., et al. (2019). Antibiotic resistance in porcine pathogenic Bacteria and relation to antibiotic usage. BMC Vet. Res. 15, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-2162-8,

Imberechts, H., De Greve, H., and Lintermans, P. (1992). The pathogenesis of edema disease in pigs. A review. Vet. Microbiol. 31, 221–233. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(92)90080-d,

Kalalah, A. A., Koenig, S. S., Feng, P., Bosilevac, J. M., Bono, J. L., and Eppinger, M. (2024). Pathogenomes of Shiga toxin positive and negative Escherichia coli O157: H7 strains Tt12a and Tt12b: comprehensive phylogenomic analysis using closed genomes. Microorganisms 12:699. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12040699,

Kaper, J. B., Nataro, J. P., and Mobley, H. L. (2004). Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 123–140. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro818,

Kim, Y. J., Kim, J. H., Hur, J., and Lee, J. H. (2010). Isolation of Escherichia coli from piglets in South Korea with diarrhea and characteristics of the virulence genes. Can. J. Vet. Res. 74, 59–64,

Kim, K., Song, M., Liu, Y., and Ji, P. (2022). Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection of weaned pigs: intestinal challenges and nutritional intervention to enhance disease resistance. Front. Immunol. 13:885253. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.885253,

Lee, S.-I., Ntakiyisumba, E., and Won, G. (2022). Systematic review and network meta-analysis to compare vaccine effectiveness against porcine edema disease caused by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia Coli. Sci. Rep. 12:6460. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-10439-x,

Lim, J. Y., Yoon, J. W., and Hovde, C. J. (2010). A brief overview of Escherichia coli O157: H7 and its plasmid O157. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20, 5–14. doi: 10.4014/jmb.0908.08007,

Ludwig, W. (2007). Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics and identification. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 120, 225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.06.023,

Luppi, A. (2017). Swine enteric Colibacillosis: diagnosis, therapy and antimicrobial resistance. Porcine health management. Placeholder TextPlaceholder TextPorcine Health Manag. 3:16. doi: 10.1186/s40813-017-0063-4

Madec, F., Bridoux, N., Bounaix, S., Cariolet, R., Duval-Iflah, Y., Hampson, D. J., et al. (2000). Experimental models of porcine post-weaning colibacillosis and their relationship to post-weaning diarrhoea and digestive disorders as encountered in the field. Vet. Microbiol. 72, 295–310. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(99)00202-3,

Makino, S.-I., Watarai, M., Tabuchi, H., Shirahata, T., Furuoka, H., Kobayashi, Y., et al. (2001). Genetically modified Shiga toxin 2e (Stx2e) producing Escherichia coli is a vaccine candidate for porcine edema disease. Microb. Pathog. 31, 1–8. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2001.0440,

Matise, I., Cornick, N. A., Samuel, J. E., and Moon, H. W. (2003). Binding of Shiga toxin 2e to porcine erythrocytes in vivo and in vitro. Infect. Immun. 71, 5194–5201. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5194-5201.2003,

Melton-Celsa, A. R. (2014). Shiga toxin (Stx) classification, structure, and function. Microbio. Spectr. 2:ehec-0024-2013. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.EHEC-0024-2013,

Mir, R. A., and Kudva, I. T. (2019). Antibiotic-resistant Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia Coli: an overview of prevalence and intervention strategies. Zoonoses Public Health 66, 1–13. doi: 10.1111/zph.12533,

Murakami, J., Kishi, K., Hirai, K., Hiramatsu, K., Yamasaki, T., and Nasu, M. (2000). Macrolides and clindamycin suppress the release of Shiga-like toxins from Escherichia coli O157: H7 in vitro. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 15, 103–109. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(00)00126-6,

Nammuang, D., Shen, Y.-W., Ke, C.-H., Kuan, N.-L., Lin, C.-N., Yeh, K.-S., et al. (2024). Isolation and evaluation of the pathogenicity of a hybrid Shiga toxin-producing and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in pigs. BMC Vet. Res. 20:480. doi: 10.1186/s12917-024-04317-z,

Nataro, J. P., and Kaper, J. B. (1998). Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11, 142–201. doi: 10.1128/CMR.11.1.142,

Rivera, F., Sotelo, E., Morales, I., Menacho, F., Medina, A., Evaristo, R., et al. (2012). Detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) in healthy cattle and pigs in Lima, Peru. J. Dairy Sci. 95, 1166–1169. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4662

Rocha, E. P. (2004). The replication-related organization of bacterial genomes. Microbiology 150, 1609–1627. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26974-0

Seo, B., Moon, J., Gi Jeong, W., Chai Kim, S., Kim, W.-I., and Hur, J. (2018). Virulence-associated genes and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli isolated from post-weaning piglets with diarrhea in Korea. J Bacteriol Mycol 5:1090.

Sperling, D., Isaka, N., Karembe, H., Vanhara, J., Vinduska, J., Strakova, N., et al. (2022). Effect of the vaccination against Shiga toxin 2e in a farm with history of Oedema disease, caused by atypical Escherichia coli producing Shiga toxin (STEC). Vet. Med. 67, 510–518. doi: 10.17221/36/2022-VETMED,

Tabaran, F., and Tabaran, A. (2019). Edema disease of swine: a review of the pathogenesis. Porcine Res. 9, 7–14.

Tozzoli, R., Grande, L., Michelacci, V., Ranieri, P., Maugliani, A., Caprioli, A., et al. (2014). Shiga toxin-converting phages and the emergence of new pathogenic Escherichia coli: a world in motion. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 4:80. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00080,

Tseng, M., Fratamico, P. M., Manning, S. D., and Funk, J. A. (2014). Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in swine: the public health perspective. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 15, 63–75. doi: 10.1017/S1466252313000170,

Vidotto, M. C., Lima, N., Fritzen, J. T., Freitas, J. C., Venâncio, E. J., and Ono, M. A. (2009). Frequency of virulence genes in Escherichia coli strains isolated from piglets with diarrhea in the north Parana state, Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 40, 199–204. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822009000100035,

Zhang, W., Zhao, M., Ruescg, L., Omot, A., and Francis, D. (2007). Prevalence of virulence factors of Escherichia coli strains isolated from pigs with post-weaning diarrhea. Vet. Microbiol. 123, 145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.02.018

Zhao, S., White, D. G., Ge, B., Ayers, S., Friedman, S., English, L., et al. (2001). Identification and characterization of Integron-mediated antibiotic resistance among Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 1558–1564. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.4.1558-1564.2001,

Zheng, J., Cui, S., Teel, L. D., Zhao, S., Singh, R., O'Brien, A. D., et al. (2008). Identification and characterization of Shiga toxin type 2 variants in Escherichia coli isolates from animals, food, and humans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5645–5652. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00503-08,

Zingali, T., Reid, C. J., Chapman, T. A., Gaio, D., Liu, M., Darling, A. E., et al. (2020). Whole genome sequencing analysis of porcine Faecal commensal Escherichia coli carrying class 1 Integrons from sows and their offspring. Microorganisms 8:843. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8060843,

Keywords: Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), porcine edema disease (ED), national surveillance, prevalence, virulence factor, vaccine candidates

Citation: Park G-S, Kim H-J, Cho MA, Kim S-C, Jeong C-G, Ryu J-H, Kwon WJ, Lee HJ, Kang J-G, Jung BY, Kim MH, Kim C, Kim W-I and Seo BJ (2025) Phenotypic and genotypic profiling of swine-derived Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli over a decade in South Korea: a framework for edema disease vaccine candidate strains selection. Front. Microbiol. 16:1701708. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1701708

Edited by:

Manuel Rodriguez-Iglesias, University of Cádiz, SpainReviewed by:

Moo-Seung Lee, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB), Republic of KoreaRina Opulencia, University of the Philippines Los Baños, Philippines

Copyright © 2025 Park, Kim, Cho, Kim, Jeong, Ryu, Kwon, Lee, Kang, Jung, Kim, Kim, Kim and Seo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chonghan Kim, Y2hvbmdoYW4yMDA0QG5hdmVyLmNvbQ==; Won-Il Kim, a3dpMDYyMUBqYm51LmFjLmty; Byoung Joo Seo, YnlvdW5nam9vc2VvQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Gyeong-Seo Park

Gyeong-Seo Park Hwan-Ju Kim

Hwan-Ju Kim Myung A. Cho3†

Myung A. Cho3† Seung-Chai Kim

Seung-Chai Kim Won-Il Kim

Won-Il Kim Byoung Joo Seo

Byoung Joo Seo