- 1Third Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Xiamen, China

- 2Fujian Key Laboratory of Island Monitoring and Ecological Development (Island Research Center, MNR), Pingtan, China

- 3Stomatological Hospital of Xiamen Medical College, Xiamen, China

- 4School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Xiamen Medical College, Xiamen, China

- 5School of Stomatology, Xiamen Medical College, Xiamen, China

- 6Fujian Huijing Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Zhangzhou, China

Background: Periodontitis, a chronic gum disease caused by Porphyromonas gingivalis infection, if left untreated, can result in tooth loss, alveolar bone loss, halitosis and other oral health complications.

Methods: To investigate the preventive and therapeutic effects of Lacticaseibacillus casei DS31 from the large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) on periodontitis, three experimental models—biofilm, cellular, and animal models—were established to systematically evaluate its efficacy. First, we sought to clarify the effect of DS31 against P. gingivalis biofilm. Then, the investigation entailed a comprehensive examination of the immunomodulatory effects of heat-inactivated probiotics on inflammation-inducing cells. Finally, the impact of probiotics on gingival tissue and alveolar bone was evaluated using an established periodontitis rat model.

Results: The results demonstrated that bacteria suspension or cell-free supernatant of L. casei DS31 effectively inhibited P. gingivalis biofilm formation and eradicated existing biofilms, thereby reducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β) and inflammatory mediators (NO). Microcomputed tomography (micro-CT) and histopathological analysis revealed that supplementation with BS-DS31 or CFS-DS31 mitigated alveolar bone loss and increased bone mineral density in the experimental animals. The secretion of inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8) in the gingival tissue of the rats was reduced.

Conclusion: Lacticaseibacillus casei DS31 demonstrates significant potential for alleviating periodontitis and could serve as a promising probiotic candidate for incorporation into functional foods and oral health therapeutic applications.

1 Introduction

Periodontitis is a chronic, multifactorial inflammatory disease associated with dysbiotic dental plaque biofilms and characterized by progressive destruction of the tooth-supporting apparatus. Its primary clinical features include loss of periodontal tissue support, as evidenced by clinical attachment loss (CAL) and radiographically confirmed alveolar bone loss, as well as the presence of periodontal pocketing and gingival bleeding (Papapanou et al., 2018). Extensive research has established a robust association between periodontitis and various systemic conditions, including diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, dyslipidemia, stroke and osteoporosis (Wang and McCauley, 2016; Minty et al., 2019; Bassani et al., 2023; Zheng et al., 2023). Periodontitis imposes a significant burden on global public health (Qiao et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2023).

The oral microbiota consists of more than 700 distinct microbial species, which form complex biofilms that are essential for health. Disruption of microbial homeostasis in periodontal tissues can lead to the overgrowth of pathogenic organisms within these biofilms, resulting in periodontitis and eliciting host immune responses (Cui et al., 2025). Subgingival microbial dysbiosis—characterized by an increased abundance of Periodontal Red Complex Pathogens, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia—plays a pivotal role in the initiation and progression of periodontal disease (Yadalam et al., 2023). Furthermore, oral dysbiosis may exert systemic effects via immune-mediated mechanisms. Regional immunity in periodontal tissues, mediated by neutrophils, T helper 17 cells, and various immune-related cytokines, is critical for preserving periodontal homeostasis and responding to microbial disturbances. Therefore, the microbiome is widely recognized for its critical role in maintaining overall bodily health (Meng et al., 2020; Réthi-Nagy and Juhász, 2024). Specifically, the oral microbiome significantly contributes to the oral barrier. An imbalance within this microbial community, characterized by an increased proportion of anaerobic Gram-negative bacteria, can lead to periodontitis (Ai et al., 2022; Chew et al., 2025). P. gingivalis, a key pathogenic bacterium in periodontitis, forms a dense biofilm on tooth surfaces (Guo et al., 2020). Its virulence factors, including lipopolysaccharide, proteases, and fimbriae, not only enhance bacterial colonization and facilitate the expansion of the surrounding microbial community but also promote coaggregation with other bacteria and the formation of dental biofilm (Xu et al., 2020). Moreover, these virulence factors modulate various host immune components, subverting the immune response to either facilitate bacterial evasion from clearance or induce an inflammatory environment (Abdi et al., 2017). In biofilm form, bacterial resistance to antibacterial substances is 10 to 1000 times greater than that of planktonic bacteria. And the gene expression profiles differ significantly from those of planktonic bacteria (Romero-Lastra et al., 2017).

Current treatments for periodontitis predominantly involve scaling and root planning therapy as well as antibiotic administration (Valenza et al., 2009; Ardila and Bedoya-García, 2022; Wang et al., 2024). However, these methods are insufficient in preventing disease recurrence and may contribute to the development of antibiotic resistance (MacLean and San Millan, 2019; Cobb and Sottosanti, 2021; Chen et al., 2025). Due to the limitations of existing therapies, there is an urgent need to explore safer and more patient-friendly alternatives that can potentially replace conventional treatments. Therefore, the development of innovative preventive and therapeutic strategies is of critical importance.

Probiotics are defined as living microorganisms that can exert beneficial effects on the host when administered in adequate amounts (Cremon et al., 2018). Probiotics are predominantly consist of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), including Lactobacillus spp. (Mokoena, 2017). Probiotics are directly edible strains that can serve as a source of functional food, maintaining host health primarily by maintaining a balance between beneficial strains, secreting antibacterial compounds, and regulating immune responses (Abbasiliasi et al., 2012; Gryaznova et al., 2022; Sugajski et al., 2022). In addition, LAB have been actively studied for their effects, such as improving cardiac function, reducing cholesterol level and mitigating diabetes mellitus (Silva-Cutini et al., 2019; Wang G. et al., 2020; Wan et al., 2023). In recent years, researchers have also found that probiotics can also regulate the oral microbiome. Leading to increased interest, probiotic therapy is increasingly being used to prevent and treat dental caries, halitosis, periodontitis, and other chronic oral infectious diseases (Bustamante et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022; Robo et al., 2024). Currently, probiotics with preventive and therapeutic potential against periodontitis are primarily derived from terrestrial sources, whereas probiotics from marine sources have not yet been reported.

The objective of this study is to investigate the preventive or therapeutic effects of L. casei DS31bacterial suspension or its supernatant on periodontitis. To investigate the prevention and treatment of periodontitis, we established biofilm models to evaluate the efficacy of probiotics. Subsequently, we developed a periodontitis cell model using macrophages cell line RAW264.7 to assess the anti-inflammatory efficacy of L. casei DS31. Ultimately, a periodontitis rat model was established to demonstrate the therapeutic potential of L. casei in vivo. This strain exhibits inhibitory effects against periodontitis-causing pathogens and demonstrates potential for the prevention and treatment of periodontitis. The summarized results provide suitable information in the field of the host-microbiota-pathogen interaction.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation of experiment

The L. casei DS31 strain was cultured in de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) broth (Huankai Microbial Sci. & Tech, Guangdong, China) for 16 h at 37 °C and adjusted to a density of 106–108 CFU/mL. The adjusted culture medium was inoculated with 1% in fresh MRS broth and further cultured for 48 h. The bacterial suspensions of L. casei DS31 (BS-DS31) was harvested. Subsequently, the bacterial suspensions were centrifuged at 9500 rpm for 30 min and filtered to obtain a cell-free supernatant (CFS-DS31).

Porphyromonas gingivalis (ATCC 33277) was obtained from the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center and was propagated on Columbia blood agar (Hopebio Company, Qingdao, China) at 37 °C in an anaerobic incubator (85% N2, 10% H2, and 5% CO2) for 48 h. Next, Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) broth (Hopebio Company) was inoculated with a P. gingivalis culture (1%, v/v) followed by incubation at 37 °C for 72 h.

2.2 Cell culture and differentiation

RAW264.7 cells (murine macrophages) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% of penicillin-streptomycin solution (P/S, Gibco). Cultures were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

2.3 The effect of DS31 against P. gingivalis

2.3.1 Biofilm formation assay

Porphyromonas gingivalis cultures that incubated for 72 h at 37 °C were adjusted to 106 CFU/mL through dilution in TSB broth. Next, the DS31 (BS-DS31 or CFS-DS31) and P. gingivalis were added to upper and lower chambers of 24-well transwell plates (0.4 μm, Corning, NY, USA), respectively, at a ratio of 1:1 (v/v) (Luan et al., 2022). After the incubation of transwell plates for 48 h at 37 °C, the fluid culture medium within the lower chamber was gently removed and discarded; then, the P. gingivalis biofilm at the bottom of each well was gently washed three times with PBS to remove any planktonic bacteria. Thereafter, P. gingivalis biofilm in each lower chamber was fixed using a 99% (v/v) methanol solution at 4 °C for 30 min and subsequently air-dried at room temperature. Next, Gram staining kit was added to each lower transwell chamber. Thereafter, P. gingivalis biofilm structure was observed under a microscope (XD-202, Jiangnan, Nanjing, China).

2.3.2 Biofilm eradication assay

Porphyromonas gingivalis cultures that had been incubated for 72 h at 37 °C was adjusted to 106 CFU/mL through dilution in TSB broth. Next, P. gingivalis was added to upper and lower chambers of 24-well transwell plates (Luan et al., 2022)(0.4 μm, Corning, NY, USA). After the incubation of transwell plates for 120 h at 37 °C, the fluid culture medium within the lower chamber was gently removed and discarded; then, the P. gingivalis biofilm at the bottom of each well was gently washed three times with PBS to remove any planktonic bacteria. The BS-DS31 or CFS-DS31 was added to the biofilm for 48 h. Subsequently, P. gingivalis biofilm in each lower chamber was fixed in 99% (v/v) methanol solution at 4 °C for 30 min and dried at room temperature. Next, Gram staining kit was added to each lower transwell chamber. Thereafter, P. gingivalis biofilm structure was observed under a microscope.

2.4 Nitric oxide (NO) production

The production of nitric oxide (NO) was quantified in P. gingivalis LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells using assay kits to measure levels of each compound (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA USA). RAW 264.7 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and incubated overnight at 37 °C The cells were treated with DMEM (FBS-free) containing 1 μg/mL of P. gingivalis LPS (PgLPS; InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA), and then treated with 1% heat-killed BS-DS31 or CFS-DS31, further incubated for 24 h. Thereafter, the culture medium of each group (90 μL) and fresh Griess reagent (10 μL) were mixed in a new plate and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 548 nm using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Shanghai, China). NaNO2 was used as the standard to quantify NO.

2.5 Cytokine and inflammation assays

To assess P. gingivalis anti-inflammatory activity, RAW264.7 cells were treated with heat-killed BS-DS31 or CFS-DS31 for 1 h and then 1 μg/mL of P. gingivalis LPS (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) was added to cells followed by incubation of stimulated cells for 24 h (37°C, 5% CO2, 90% relative humidity) (Luan et al., 2022). The effects of L. casei DS31 on the production of TNF-α, interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1β (IL-1β) were assessed in P. gingivalis LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells using enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Shanghai Enzyme linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

2.6 Animal experiment design

All protocols were approved by the Institutional Committee on the Care and Use of Animals of the Third Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources. A total of 15 8-week-old both sexes Wistar rats weighing 200–210 g (SLAC Laboratory, Shanghai, China). The rats were maintained under a 12-h light/dark cycle at a temperature of 22–24 °C. The experimental timeline is shown in Figure 1.

After a 1-week adaptation period, 15 rats were randomly divided into 2 groups: three rats in the normal control (NC) group and twelve rats in the Periodontitis disease (PD) groups. During the 6-week modeling period, the PD groups were randomly divided into four groups: Periodontitis disease (Model), DS31 bacterial suspension (BS-DS31), DS31 cell-free supernatant (CFS-DS31) and positive control (PC) groups. In the following 3 weeks, apart from the model group and the healthy group, three experimental groups were given BS-DS31, CFS-DS31 and compound tinidazole.

The PD groups were fed a high-caries-inducing diet, Keyes 2000 (Nantong Trophy Feed Technology Co., Ltd.) and 10% sucrose water (Zhang et al., 2021). The NC group ate only standard chow and distilled water throughout the experiment, and the model group underwent ligation with 5-0 silk thread and given Pg-LPS and P. gingivalis culture once every 2 days. The BS-DS31 group received the bacterial suspension of DS31, the CFS-DS31 group was administered the fermentation supernatant of DS31, and the PC group was treated with compound chlorhexidine mouthwash. The schematic representation of the periodontitis model is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of the multi-combination approach for constructing a periodontitis rat model.

2.7 Micro-computerized tomography (Micro-CT)

Maxillae were evaluated using a microcomputed tomography (micro-CT) system (Quantum GX2; PerkinElmer, Hopkinton, MA, USA). Before scanning, the maxillae were rinsed with double distilled water and transferred to sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) then the micro-CT parameters were set as follows: voltage, 90 kV; current, 88 μA; field of view, 18 μm; acquisition time, 14 min; and camera mode, high resolution.

The following parameters were analyzed: (1) CEJ-ABC distance: the linear measurement from the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) to the alveolar bone crest (ABC) at both the distal and mesial aspects of the upper second molar (2) Bone mineral density: the concentration of minerals per unit volume of bone.

2.8 Histopathologic analysis

Samples were fixed in an Eppendorf tube using a 10% neutral buffered formalin solution. The jaw samples were subsequently decalcified for 24 h using a 10% formic acid solution. Following decalcification, the samples were dehydrated through a graded alcohol series (70%, 90%, 95%, and 99%) and cleared in xylene for 10 min before being embedded in paraffin. Sections of 5 μm thickness were cut in the mesiodistal direction using a microtome and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) for microscopic analysis (Lestari et al., 2023).

2.9 Detection of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 in the periodontal tissues

The periodontal tissue samples were homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer (Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) supplemented with 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The total protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Biosharp) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, with bovine serum albumin (BSA) serving as the standard and assumed to be 100% pure. The concentration of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 were subsequently quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Shanghai Enzyme linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer-provided protocols. The results are reported in terms of BSA equivalents.

2.10 Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate and are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.5; GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), and Dunnett’s test was employed to assess the significance of differences between the control and sample groups, with a threshold of p < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 The effect of biofilm formation assay

The growth characteristics of the P. gingivalis biofilm were examined under a microscope. In the model group, a highly organized yet heterogeneous biofilm structure with numerous P. gingivalis organisms was observed. In the control group, only MRS Medium was added, and no biofilm was produced. The results demonstrated that both the BS-DS31 and the CFS-DS31 inhibited the formation of P. gingivalis biofilm. The purple coloration in the BS-DS31 group suggested that L. casei DS31 had colonized the biofilm and became the predominant bacterium. The effect observed in the CFS-DS31 was comparable to that of the blank control group. Both the BS-DS31 and the CFS-DS31 demonstrated significant inhibition of biofilm formation by P. gingivalis (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Microscopy images of L. casei DS31 inhibit Porphyromonas gingivalis biofilm formation stained with Gram stain after cultured.

3.2 The effect of biofilm eradication assay

The mature P. gingivalis biofilm treated with BS-DS31 or CFS-DS31 was observed under the microscope. In the model group, after culturing P. gingivalis for 120 h, a highly organized yet heterogeneous biofilm structure containing numerous P. gingivalis organisms was observed. In the control group, only MRS medium was included. The results demonstrated that both the BS-DS31 and CFS-DS31 groups effectively cleared the mature P. gingivalis biofilm. Specifically, treatment with the BS-DS31 resulted in increased biofilm gaps and a purplish-red coloration, indicating the presence of a mixed biofilm of pathogenic bacteria and probiotics, with pathogenic bacteria being removed through co-aggregation. Following CFS-DS31 treatment, only lilac remnants were observed in the biofilm, suggesting the presence of antibacterial substances in the L. casei DS31 supernatant, which exhibited strong antibacterial activity (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Microscopy images of mature P. gingivalis biofilm treated with L. casei DS31. Biofilm stained with Gram stain after cultured.

3.3 The anti-inflammatory effects of L. casei DS31 on proinflammatory cytokine expression in P. gingivalis LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells

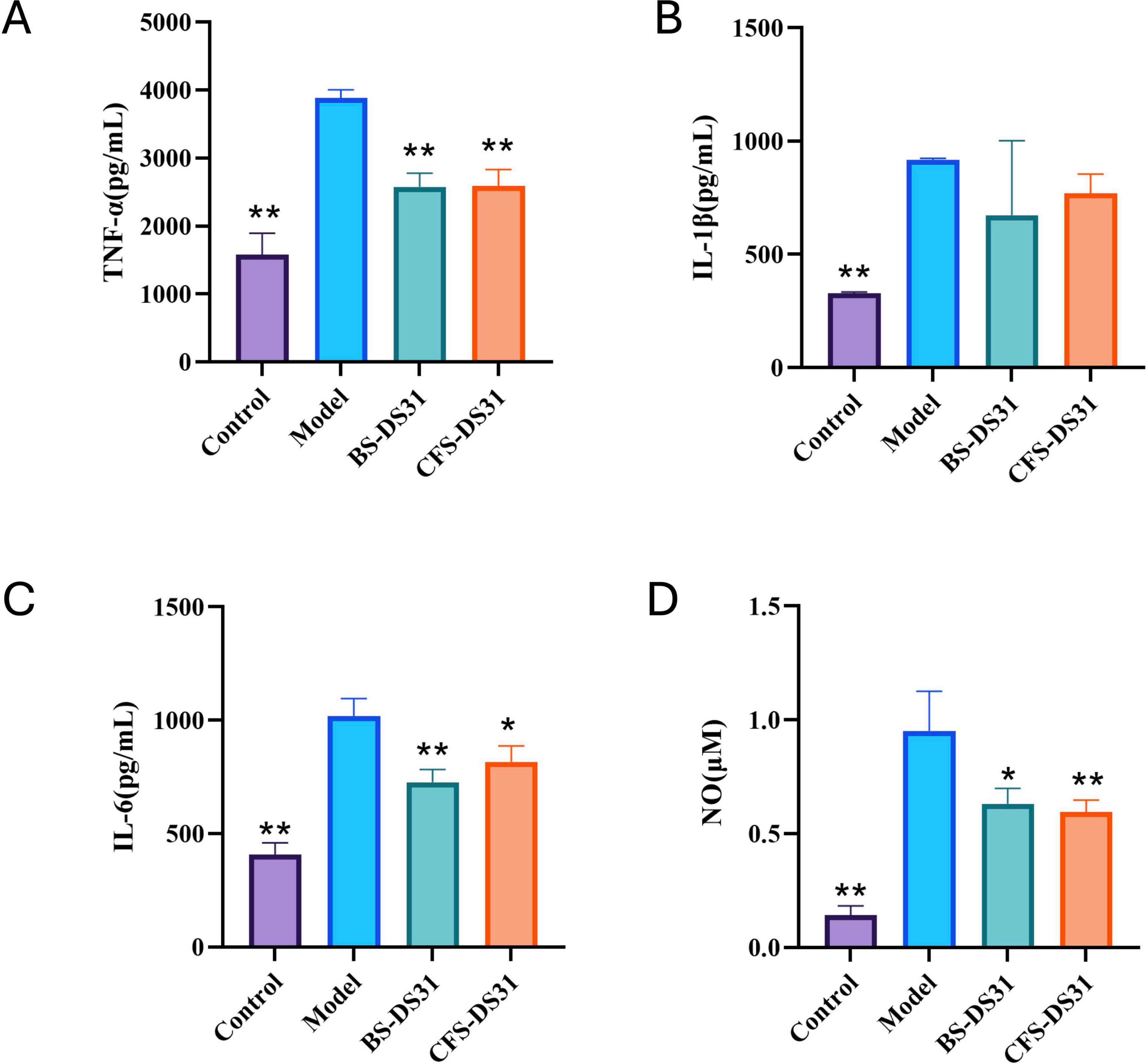

As anticipated, the exposure of RAW 264.7 cells to P. gingivalis LPS for 24 h clearly stimulated the cells and led to increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α). However, treatment of RAW 264.7 cells by BS-DS31 or CFS-DS31 suppressed the levels of secreted and TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, after P. gingivalis LPS stimulation (Figures 5A–C), thereby mitigating the inflammatory response of RAW 264.7 cells. P. gingivalis LPS stimulation also significantly increased the secretion levels of the inflammatory mediator NO in RAW264.7. Notably, L. casei DS31 treatment effectively suppressed NO production following LPS exposure (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Effect of BS-DS31 or CFS-DS31 on proinflammatory cytokines in RAW264.7 cells. The concentrations of TNF-α (A), IL-1β (B) and IL-6 (C) were measured using ELISA kits. The levels of NO (D) were determined using assay kits. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to the model group.

3.4 Micro-CT analysis

Periodontitis induces alveolar bone resorption in periodontal rats (Figure 6). In particular, the root furcation was obviously exposed, and the distance from the cementoenamel junction to the alveolar bone crest (CEJ-ABC; Figure 7A) increased significantly. In addition, the dental spaces in the model group were notably larger. Meanwhile, the bone density (Figure 7B) in the model group was significantly lower compared to that in the healthy group. The alveolar bone resorption in rats treated with BS-DS31 and CFS-DS31 was significantly reduced, as evidenced by a decreased CEJ-ABC distance compared to untreated periodontitis rats. Additionally, the alleviation of alveolar bone loss was observed through increased alveolar bone density, thereby enhancing the supportive function for teeth. Both BS-DS31 and CFS-DS31 can mitigate periodontitis in rats.

Figure 7. The cementoenamel junction-alveolar bone crest (CEJ-ABC) distance (A) and bone mineral density (BMD) (B) were used as indices of alveolar bone loss and were measured through micro-CT imaging. Data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Significance was analyzed using Dunnett’s test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus model group.

3.5 Histopathologic analysis

H&E staining revealed pronounced infiltration of highly proinflammatory immune cells, along with loss of connective tissue attachment and alveolar bone resorption between the distal root of the first molar and the mesial root of the second molar demonstrated by the distance of the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) to the alveolar bone crest (ABC), thereby clearly demonstrated that BS-DS31 and CFS-DS31 reduced periodontal tissue inflammation and apical movement of the junctional epithelium (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Representative H&E staining sections of gingival tissues. The scale bars represent 100 μm.

3.6 Immune response

In addition to the effects on the composition of the oral plaque, damage to periodontal tissues is primarily mediated through changes in the inflammatory response. The levels of various inflammatory factors associated with periodontitis, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8, were quantified using ELISA and were presented in Figure 8. After treatment with BS-DS31 and CFS-DS31, the levels of these four inflammatory factors were significantly reduced compared to those in the model group, indicating that both BS-DS31 and CFS-DS31 exert a beneficial effect on reducing gingival inflammation in periodontitis-induced rats (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Effects of L. casei DS31 treatment on the expression of immune indicators TNF-α (A), IL-1β (B), IL-6 (C) and IL-8 (D). Groups with dissimilar letters differ, p < 0.05.

4 Discussion

Periodontitis is a highly prevalent chronic inflammatory disease affecting individuals across all age groups. Bacterial biofilms, which adhere to surfaces such as human tooth enamel, consist of complex microbial communities enclosed within a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. These structured communities enable free-living planktonic bacteria to transition into a multicellular mode of growth, contributing significantly to persistent and recurrent infections (Dsouza et al., 2024). Due to their dense architecture and protective matrix, biofilms pose a major challenge to conventional antimicrobial therapies, which often fail to penetrate and effectively eradicate the pathogens involved in periodontitis. The rising prevalence of antibiotic resistance, driven by the overuse of traditional antimicrobial agents, further underscores the need for more effective and innovative treatment strategies (Gerits et al., 2017). In response to these challenges, novel therapeutic approaches-including the use of probiotics-are currently being investigated to target and disrupt biofilm formation and enhance clinical outcomes.

To investigate and simulate the effects of probiotics on dental plaque, we established an in vitro periodontitis biofilm model to examine the preventive and therapeutic effects of BS-DS31 and CFS-DS31. The results demonstrated that both the BS-DS31 and CFS-DS31 exhibited significant inhibitory effects. After Gram staining, it was observed that in the BS-DS31 group, lactic acid bacteria formed a self-membrane and occupied the sites of the original P. gingivalis biofilm, while in the CFS-DS31 group, there was almost no presence of P. gingivalis biofilm. Notably, the BS-DS31 could auto-formed a biofilm, thereby displacing the P. gingivalis biofilm and becoming the dominant bacterium. In contrast, the CFS-DS31 almost completely inhibited the presence of pathogenic bacteria. Both Lactobacillus and P. gingivalis can form biofilms in vitro. To differentiate between these two bacteria, we utilized a Gram staining kit, which stained P. gingivalis red as gram-negative bacteria and Lactobacillus purple as gram-positive bacteria. Jiang et al. (2022) studied an antimicrobial peptide that exhibits potent inhibitory activity on both planktonic bacteria and biofilm of P. gingivalis and reduces the expression of its virulence factors.

In our study, L. casei DS31 was used in the form of a crude bacterial extract. However, according to the existing biofilm results, L. casei DS31 demonstrates significant inhibitory and scavenging effect on P. gingivalis biofilm. If future analyses can identify specific bacteriostatic compounds, such as proteins or bacterial polysaccharides, this would provide more concrete solutions for the prevention and treatment of periodontitis. It is widely recognized that the human oral environment is highly complex. Human oral cavity (mouth) hosts a complex microbiome consisting of bacteria, archaea, protozoa, fungi and viruses (Mosaddad et al., 2019). For example, bacterial species such as P. gingivalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Actinomyces naeslundii, T. forsythia, and Streptococcus gordonii play significant roles in this process (Kamińska et al., 2019). These bacteri are responsible for periodontitis. This disease is caused by plaques, which are a community of microorganisms in biofilm format. Future studies will aim to construct a more realistic model of periodontitis biofilm to evaluate the efficacy of L. casei DS31.

The immune system consists of both innate and adaptive immune responses. Innate immunity is responsible for recognizing and eliminating foreign pathogens during the early stages of infection, whereas adaptive immunity eliminates these pathogens through cytotoxic reactions and the secretion of antigen-specific antibodies. Macrophages, as a key component of the innate immune system, play a critical role in maintaining homeostasis by phagocytosing pathogens and releasing immunostimulatory mediators, including nitric oxide (NO), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6; Park et al., 2023). The main pro-inflammatory factors are TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, which are produced by macrophages and endothelial cells. IL-1β and TNF-α promote the aggregation and activation of inflammatory cells, stimulate the release of inflammatory mediators, induce fever, and amplify the inflammatory response. IL-6 stimulates macrophages to secrete monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), thereby facilitating the migration of monocytes from blood vessels to sites of tissue inflammation (Luan et al., 2022). Therefore, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines is crucial for alleviating inflammatory diseases. In vitro, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from P. gingivalis was used to induce mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells as a periodontitis model. BS-DS31 and CFS-DS31 were added to assess the secretion levels of inflammatory factors including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. The results demonstrated that the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were significantly reduced in the periodontitis cell models, indicating that DS31 exhibits potent anti-inflammatory effects. Wang Q. et al. (2020) demonstrated that DAA inhibited the secretion of NO, IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells, indicating anti-inflammatory effects that are consistent with our findings. Yu et al. (2019) demonstrated that heat-inactivated JW15 exhibits anti-inflammatory properties through the inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway and modulation of the MAPK signaling pathway.

The animal experiment results demonstrated that L. casei DS31 significantly mitigated alveolar bone resorption and loss in rats, while reducing the secretion levels of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 in gingival tissues. The CEJ-ABC distance serves as an indicator of alveolar bone resorption. A greater CEJ-ABC distance signifies a larger exposed surface area of the alveolar bone, indicating more severe periodontitis. Following treatment with the DS31 bacterial solution and supernatant, the CEJ-ABC distance was reduced, with the BS-DS31 bacterial solution demonstrating slightly superior efficacy compared to the CFS-DS31. The bone loss in periodontitis-induced rats treated with L. casei DS31 was alleviated, as evidenced by the recovery of bone mineral density. This suggests that both the BS-DS31 and CFS-DS31 can enhance the tooth-supporting capacity in periodontitis-induced rats, thereby reducing the risk of tooth loss. This finding is consistent with the study by Lucateli et al. (2024), which offers novel insights into elucidating L. casei DS31’s role in osteoporosis for future research. In a periodontitis rat model, Bifidobacterium longum BL986 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRH09 were administered both individually and in combination. The combination treatment resulted in a significantly smaller infiltrated area of gingival cells and a reduced distance from the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) to the epithelial attachment (Chen et al., 2023). L. casei DS31 exhibits comparable effects on gingival tissues, and this study offers a novel perspective on utilizing probiotics synergistically for the prevention and treatment of periodontitis. Nakajima et al. (2021) reported a deep eutectic antibacterial agent (IDEA) ionic gel that simultaneously exhibited deep tissue penetration and antibacterial activity against P. gingivalis. This finding offers valuable insights for the subsequent development of probiotic drug delivery systems.

Due to technological and temporal constraints, our study requires further refinement and investigation. For example, the oral cavity features a complex and dynamic microenvironment, necessitating the development of a biofilm model that more closely mimics in vivo conditions, as well as the conduct of clinical trials to assess the preventive and therapeutic efficacy. Furthermore, the mechanism of action of BS-DS31 and CFS-BS31 remains unclear, warranting additional research into associated antibacterial compounds and signaling pathways.

5 Conclusion

The results demonstrated that L. casei DS31 can inhibit the growth of unformed P. gingivalis and eliminate preformed P. gingivalis, thereby reducing the secretion levels of inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) and mediators (NO) in inflammation-inducing cells. Through the establishment of a periodontitis animal model, it was found that DS31 can mitigate alveolar bone microstructural bone loss and resorption in periodontitis and reduce the inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8) of gingival tissues. Our results strongly suggest that L. casei DS31 has the potential to act as a therapeutic agent or functional food for the prevention and treatment of periodontitis.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by the Institutional Committee on the Care and Use of Animals of the Third Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

YLiu: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. PW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. YLi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. XC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. LW: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YS: Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. LL: Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YC: Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. QH: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Fujian Science and Technology Program Guiding Project (2025Y0055), the Innovation Research and Development Special Funds of the Municipality-province-ministry Co-constructed (GJZX-HYSW-2025-01 and GJZX-HYSW-2024-09), and the Fujian Provincial Science & Technology Project of Health (2019-2-39).

Conflict of interest

QH was employed by Fujian Huijing Biological Technology Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbasiliasi, S., Tan, J. S., Ibrahim, T. A. T., Ramanan, R. N., Vakhshiteh, F., Mustafa, S., et al. (2012). Isolation of Pediococcus acidilactici Kp10 with ability to secrete bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance from milk products for applications in food industry. BMC Microbiol. 12:260. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-260

Abdi, K., Chen, T., Klein, B. A., Tai, A. K., Coursen, J., Liu, X., et al. (2017). Mechanisms by which Porphyromonas gingivalis evades innate immunity. PLoS One 12:e0182164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182164

Ai, R., Li, D., Shi, L., Zhang, X., Ding, Z., Zhu, Y., et al. (2022). Periodontitis induced by orthodontic wire ligature drives oral microflora dysbiosis and aggravates alveolar bone loss in an improved murine model. Front. Microbiol. 13:875091. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.875091

Ardila, C.-M., and Bedoya-García, J.-A. (2022). Clinical and microbiological efficacy of adjunctive systemic quinolones to mechanical therapy in periodontitis: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Dentistry 2022:4334269. doi: 10.1155/2022/4334269

Bassani, B., Cucchiara, M., Butera, A., Kayali, O., Chiesa, A., Palano, M. T., et al. (2023). Neutrophils’ contribution to periodontitis and periodontitis-associated cardiovascular diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24:15370. doi: 10.3390/ijms242015370

Bustamante, M., Oomah, B. D., Mosi-Roa, Y., Rubilar, M., and Burgos-Díaz, C. (2020). Probiotics as an adjunct therapy for the treatment of halitosis, dental caries and periodontitis. Probiotics Antimicrobial Proteins 12, 325–334. doi: 10.1007/s12602-019-9521-4

Chen, X., Huang, H., Guo, C., Zhu, X., Chen, J., Liang, J., et al. (2025). Controlling alveolar bone loss by hydrogel-based mitigation of oral dysbiosis and bacteria-triggered proinflammatory immune response. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35:2409121. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202409121

Chen, Y. W., Lee, M. L., Chiang, C. Y., and Fu, E. (2023). Effects of systemic Bifidobacterium longum and Lactobacillus rhamnosus probiotics on the ligature-induced periodontitis in rat. J. Dental Sci. 18, 1477–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2023.04.013

Chew, R. J. J., Tan, K. S., Chen, T., Al-Hebshi, N. N., and Goh, C. E. (2025). Quantifying periodontitis-associated oral dysbiosis in tongue and saliva microbiomes-An integrated data analysis. J. Periodontol. 96, 55–66. doi: 10.1002/JPER.24-0120

Cobb, C. M., and Sottosanti, J. S. (2021). A re-evaluation of scaling and root planning. J. Periodontol. 92, 1370–1378. doi: 10.1002/jper.20-0839

Cremon, C., Barbaro, M. R., Ventura, M., and Barbara, G. (2018). Pre- and probiotic overview. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 43, 87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2018.08.010

Cui, Z., Wang, P., and Gao, W. (2025). Microbial dysbiosis in periodontitis and peri-implantitis: Pathogenesis, immune responses, and therapeutic. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 15:1517154. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2025.1517154

Dsouza, F. P., Dinesh, S., and Sharma, S. (2024). Understanding the intricacies of microbial biofilm formation and its endurance in chronic infections: a key to advancing biofilm-targeted therapeutic strategies. Arch. Microbiol. 206:85. doi: 10.1007/s00203-023-03802-7

Gerits, E., Verstraeten, N., and Michiels, J. (2017). New approaches to combat Porphyromonas gingivalis biofilms. J. Oral Microbiol. 9:1300366. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2017.1300366

Gryaznova, M., Dvoretskaya, Y., Burakova, I., Syromyatnikov, M., Popov, E., Kokina, A., et al. (2022). Dynamics of changes in the gut microbiota of healthy mice fed with lactic acid bacteria and Bifidobacteria. Microorganisms 10:1020. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10051020

Guo, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Jin, Y., and Wang, C. (2020). Heme competition triggers an increase in the pathogenic potential of Porphyromonas gingivalis in Porphyromonas gingivalis-Candida albicans mixed biofilm. Front. Microbiol. 11:596459. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.596459

Jiang, S.-J., Xiao, X., Zheng, J., Lai, S., Yang, L., Li, J., et al. (2022). Antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of novel antimicrobial peptide DP7 against the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 133, 1052–1062. doi: 10.1111/jam.15614

Kamińska, M., Aliko, A., Hellvard, A., Bielecka, E., Binder, V., Marczyk, A., et al. (2019). Effects of statins on multispecies oral biofilm identify simvastatin as a drug candidate targeting Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Periodontol. 90, 637–646. doi: 10.1002/JPER.18-0179

Lestari, K. D., Dwiputri, E., Kurniawan Tan, G. H., Sulijaya, B., Soeroso, Y., Natalina, N., et al. (2023). Exploring the antibacterial potential of konjac glucomannan in periodontitis: Animal and in vitro studies. Medicina 59:1778. doi: 10.3390/medicina59101778

Luan, C., Yan, J., Jiang, N., Zhang, C., Geng, X., Li, Z., et al. (2022). Leuconostoc mesenteroides LVBH107 Antibacterial Activity against Porphyromonas gingivalis and anti-inflammatory activity against P. gingivalis lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. Nutrients 14:2584. doi: 10.3390/nu14132584

Lucateli, R. L., Silva, P. H. F., Salvador, S. L., Ervolino, E., Furlaneto, F. A. C., Marciano, M. A., et al. (2024). Probiotics enhance alveolar bone microarchitecture, intestinal morphology and estradiol levels in osteoporotic animals. J. Periodontal Res. 59, 758–770. doi: 10.1111/jre.13256

MacLean, R. C., and San Millan, A. (2019). The evolution of antibiotic resistance. Science 365, 1082–1083. doi: 10.1126/science.aax3879

Meng, X., Zhang, G., Cao, H., Yu, D., Fang, X., de Vos, W. M., et al. (2020). Gut dysbacteriosis and intestinal disease: Mechanism and treatment. J. Appl. Microbiol. 129, 787–805. doi: 10.1111/jam.14661

Minty, M., Canceil, T., Serino, M., and Burcelin, R. Tercé, F., and Blasco-Baque, V. (2019). Oral microbiota-induced periodontitis: a new risk factor of metabolic diseases. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Dis. 20, 449–459. doi: 10.1007/s11154-019-09526-8

Mokoena, M. P. (2017). Lactic acid bacteria and their bacteriocins: Classification, biosynthesis and applications against uropathogens: A mini-review. Molecules 22:1255. doi: 10.3390/molecules22081255

Mosaddad, S. A., Tahmasebi, E., Yazdanian, A., Rezvani, M. B., Seifalian, A., Yazdanian, M., et al. (2019). Oral microbial biofilms: an update. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 38, 2005–2019. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03641-9

Nakajima, M., Tanner, E. E. L., Nakajima, N., Ibsen, K. N., and Mitragotri, S. (2021). Topical treatment of periodontitis using an iongel. Biomaterials 276:121069. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121069

Papapanou, P. N., Sanz, M., Buduneli, N., Dietrich, T., Feres, M., Fine, D. H., et al. (2018). Periodontitis: consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Periodontol. 89, S173–S182. doi: 10.1002/JPER.17-0721

Park, S. J., Choi, J. W., Choi, H. J., Im, S. W., and Jeong, J. B. (2023). Immunostimulatory activity of Syneilesis palmata leaves through macrophage activation and macrophage autophagy in mouse macrophages, RAW264.7 cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 33, 934–940. doi: 10.4014/jmb.2301.01039

Qiao, W., Wang, F., Xu, X., Wang, S., Regenstein, J. M., Bao, B., et al. (2018). Egg yolk immunoglobulin interactions with Porphyromonas gingivalis to impact periodontal inflammation and halitosis. AMB Express. 8:176. doi: 10.1186/s13568-018-0706-0

Réthi-Nagy, Z., and Juhász, S. (2024). Microbiome’s universe: Impact on health, disease and cancer treatment. J. Biotechnol. 392, 161–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2024.07.002

Robo, I., Heta, S., Ostreni, V., Hysi, J., and Alliu, N. (2024). Application of probiotics as a constituent element of non-surgical periodontal therapy for cases with chronic periodontitis. Bull. Natl. Res. Centre 48:8. doi: 10.1186/s42269-024-01167-5

Romero-Lastra, P., Sánchez, M. C., Ribeiro-Vidal, H., Llama-Palacios, A., Figuero, E., Herrera, D., et al. (2017). Comparative gene expression analysis of Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC 33277 in planktonic and biofilms states. Public Library Sci. One 12:e0174669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174669

Silva-Cutini, M. A., Almeida, S. A., Nascimento, A. M., Abreu, G. R., Bissoli, N. S., Lenz, D., et al. (2019). Long-term treatment with kefir probiotics ameliorates cardiac function in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 66, 79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2019.01.006

Sugajski, M., Maślak, E., Złoch, M., Rafińska, K., Pomastowski, P., Białczak, D., et al. (2022). New sources of lactic acid bacteria with potential antibacterial properties. Arch. Microbiol. 204:349. doi: 10.1007/s00203-022-02956-0

Valenza, G., Veihelmann, S., Peplies, J., Tichy, D., and del Carmen Roldan-Pareja, M. (2009). Microbial changes in periodontitis successfully treated by mechanical plaque removal and systemic amoxicillin and metronidazole. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 299, 427–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.03.001

Wan, J., Wu, P., Huang, J., Huang, S., Huang, Q., and Tang, X. (2023). Characterization and evaluation of the cholesterol-lowering ability of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum HJ-S2 isolated from the intestine of Mesoplodon densirostris. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 39:199. doi: 10.1007/s11274-023-03637-w

Wang, C.-W., and McCauley, L. K. (2016). Osteoporosis and periodontitis. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 14, 284–291. doi: 10.1007/s11914-016-0330-3

Wang, F., Wei, S., He, J., Xing, A., Zhang, Y., Li, Z., et al. (2024). Flowable oxygen-release hydrogel inhibits bacteria and treats periodontitis. ACS Omega 9, 47585–47596. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.4c06642

Wang, G., Si, Q., Yang, S., Jiao, T., Zhu, H., Tian, P., et al. (2020). Lactic acid bacteria reduce diabetes symptoms in mice by alleviating gut microbiota dysbiosis and inflammation in different manners. Food Funct. 11, 5898–5914. doi: 10.1039/c9fo02761k

Wang, J., Liu, Y., Wang, W., Ma, J., Zhang, M., Lu, X., et al. (2022). The rationale and potential for using Lactobacillus in the management of periodontitis. Journal of Microbiology 60, 355–363. doi: 10.1007/s12275-022-1514-4

Wang, Q., Liang, J., Stephen Brennan, C., Ma, L., Li, Y., Lin, X., et al. (2020). Anti-inflammatory effect of alkaloids extracted from Dendrobium aphyllum on macrophage RAW 264.7 cells through NO production and reduced IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α and PGE2 expression. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 55, 1255–1264. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.14404

Xu, W., Zhou, W., Wang, H., and Liang, S. (2020). Roles of Porphyromonas gingivalis and its virulence factors in periodontitis. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 120, 45–84. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2019.12.001

Yadalam, P. K., Arumuganainar, D., Anegundi, R. V., Shrivastava, D., Alftaikhah, S. A. A., Almutairi, H. A., et al. (2023). CRISPR-Cas-based adaptive immunity mediates phage resistance in periodontal red complex pathogens. Microorganisms 11:2060. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11082060

Yang, Y. J., Song, J.-H., Yang, J.-H., Kim, M. J., Kim, K. Y., Kim, J.-K., et al. (2023). Anti-periodontitis effects of Dendropanax morbiferus H. Lév leaf extract on ligature-induced periodontitis in rats. Molecules 28:849. doi: 10.3390/molecules28020849

Yu, H. S., Lee, N. K., Choi, A. J., Choe, J. S., Bae, C. H., and Paik, H. D. (2019). Anti-Inflammatory potential of probiotic strain Weissella cibaria JW15 isolated from kimchi through regulation of NF-κB and MAPKs pathways in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 29, 1022–1032. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1903.03014

Zhang, Q., Xu, W., Xu, X., Lu, W., Zhao, J., Zhang, H., et al. (2021). Effects of Limosilactobacillus fermentum CCFM1139 on experimental periodontitis in rats. Food Funct. 12, 4670–4678. doi: 10.1039/d1fo00409c

Keywords: Lacticaseibacillus casei, periodontitis, Porphyromonas gingivalis, biofilm, rats

Citation: Liu Y, Wu P, Li Y, Chen X, Wang L, Su Y, Luo L, Cai Y, Huang Q and Tang X (2025) Probiotics and amelioration of periodontitis: significant roles of Lacticaseibacillus casei DS31. Front. Microbiol. 16:1715664. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1715664

Received: 29 September 2025; Revised: 08 November 2025; Accepted: 10 November 2025;

Published: 12 December 2025.

Edited by:

Santosh Pandit, Chalmers University of Technology, SwedenReviewed by:

Salvatore Walter Papasergi, National Research Council (CNR), ItalyAna Đinić Krasavčević, University of Belgrade, Serbia

Copyright © 2025 Liu, Wu, Li, Chen, Wang, Su, Luo, Cai, Huang and Tang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xu Tang, dGFuZ3h1QHRpby5vcmcuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Yang Liu

Yang Liu Peng Wu

Peng Wu Yizhen Li1,2

Yizhen Li1,2 Xiaofeng Chen

Xiaofeng Chen Yanjun Su

Yanjun Su Lianzhong Luo

Lianzhong Luo Yihuang Cai

Yihuang Cai