- 1Department of Graduate School, Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, Harbin, Heilongjiang, China

- 2The Fifth Department of Acupuncture, First Affiliated Hospital of Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, Harbin, Heilongjiang, China

- 3Department of Medicine, Heilong Academy of traditional Chinese Medicine, Harbin, Heilongjiang, China

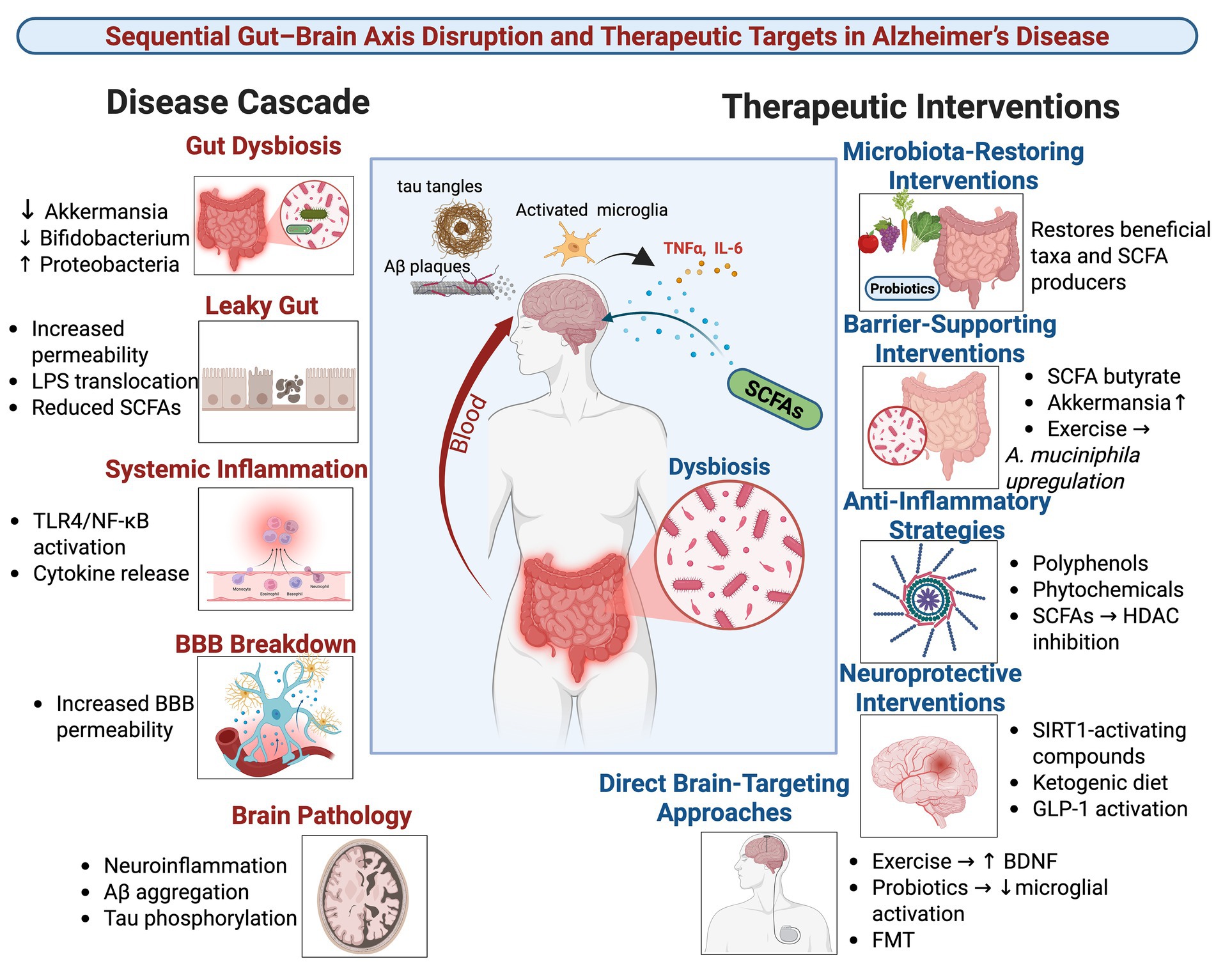

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder with limited treatment options, underscoring the need for novel therapeutic targets. The gut-brain axis has emerged as a critical bidirectional communication system, with growing evidence establishing gut dysbiosis as a causal factor in AD pathogenesis. This dysbiosis, characterized by a reduction in beneficial microbes and an increase in pro-inflammatory taxa, compromises intestinal and blood–brain barrier integrity, promoting systemic inflammation and the translocation of neurotoxic agents like lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Consequently, the balance of key microbial metabolites is disrupted, reducing neuroprotective short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and indoles while elevating inflammatory mediators, which collectively exacerbate neuroinflammation, amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition, and tau pathology. This review evaluates promising interventions, including probiotics, anti-inflammatory diets, exercise, and phytochemicals that can restore microbial balance, enhance barrier function, and improve cognitive outcomes in preclinical and early clinical studies. However, clinical translation is hindered by an overreliance on animal models, short-term studies, and insufficient mechanistic insight. Future research must prioritize large-scale human trials, multi-omics integration to elucidate signaling pathways, and personalized approaches that account for host genetics and baseline microbiome composition to fully harness the therapeutic potential of the gut-brain axis for AD.

1 Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder with limited effective treatment options, driving the search for novel pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Emerging research underscores the gut-brain axis as a critical bidirectional communication system that plays a fundamental role in the pathogenesis and progression of AD and related cognitive decline (Sun M. et al., 2020; Denman et al., 2023; Su et al., 2025). This system integrates neural, endocrine, immune, and metabolic signals between the gut microbiota and the central nervous system (CNS) (McGrattan et al., 2019; Grabrucker et al., 2023). A characteristic gut dysbiosis, marked by an increase in Proteobacteria and Clostridia alongside a decline in beneficial taxa such as Akkermansia, Blautia, and Clostridium butyricum, is consistently observed in both AD patients and experimental models, correlating with cognitive deficits and AD-related neuropathology (Varesi et al., 2022; Marizzoni et al., 2023). While compelling, the current evidence base derives predominantly from animal studies, with human clinical data often limited by smaller sample sizes, shorter durations, and methodological heterogeneity. Furthermore, confounding factors inherent to human studies; such as diverse dietary patterns, concomitant medications, and comorbidities, complicate the establishment of direct causality and highlight the need for more rigorous, controlled human trials.

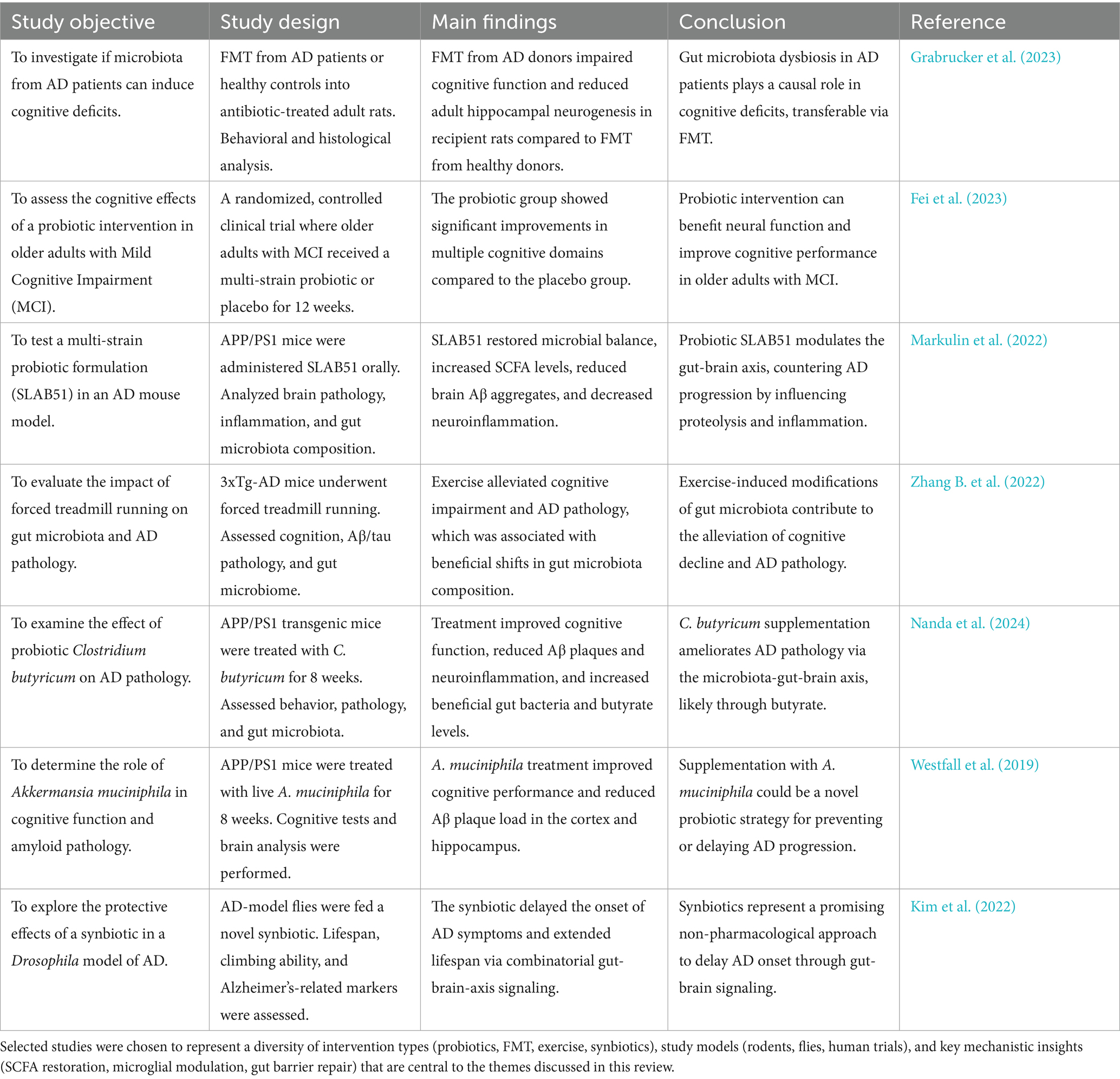

The mechanisms through which gut dysbiosis contributes to AD pathology are becoming increasingly clear, though a deeper mechanistic integration is required. Dysbiosis compromises intestinal barrier function, leading to a “leaky gut” that permits the translocation of microbial products like LPS into systemic circulation (Yang X. et al., 2020; Gates et al., 2022). This promotes systemic inflammation and increases blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability, facilitating the entry of neurotoxic agents into the CNS. Concurrently, dysbiosis alters the production of key microbial metabolites. A reduction in neuroprotective short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly butyrate, coupled with elevated neurotoxic metabolites such as quinolinic acid and a decrease in anti-inflammatory mediators like IL-10, exacerbates neuroinflammation. These effects are mediated through the activation of microglia and engagement of signaling pathways involving NF-κB and the NLRP3 inflammasome (Erny et al., 2021; Amin et al., 2023; Nakhal et al., 2024). Critically, microbial metabolites also signal through specific host receptors, including free fatty acid receptors (FFAR2/3) for SCFAs, Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) for LPS, and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) for tryptophan derivatives like indoles to modulate neuroimmune responses and neuronal integrity (Marizzoni et al., 2020; Chen S. et al., 2023). The causal role of gut microbiota in AD is further reinforced by studies demonstrating that fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from AD patients into healthy rodents can induce cognitive impairments and deficits in hippocampal neurogenesis (Bonfili et al., 2022; Fei et al., 2023).

Considering these mechanistic insights, therapeutic strategies targeting the gut-brain axis show considerable promise. Interventions such as anti-inflammatory dietary patterns (Mediterranean or DASH diets), specific probiotics (Clostridium butyricum), physical exercise, and phytochemicals have been shown in preclinical and early clinical studies to restore microbial balance, attenuate neuroinflammation, improve synaptic function, and enhance cognition (Hao et al., 2024; Nicolas et al., 2024; Zheng et al., 2024). However, the translation of these findings is complicated by the influence of host factors such as genetics, baseline microbiome composition, diet, medications, and comorbidities, which can significantly modulate individual responses to intervention.

This review aims to synthesize current evidence on the causal role of gut dysbiosis in AD, critically evaluate the promise and limitations of microbiome-targeted therapies, and assess the key knowledge gaps that must be addressed to advance gut-brain axis-based interventions for the prevention and treatment of AD. We place a particular emphasis on the need to bridge preclinical findings with human clinical evidence and to elucidate the complex, interlinked signaling pathways that mediate gut-brain communication in AD.

2 Biological mechanisms in targeting the gut-brain axis in AD

AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the accumulation of Aβ plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, chronic neuroinflammation, synaptic dysfunction, and neuronal loss (Knopman et al., 2021; Kamatham et al., 2024). While existing pharmacological treatments show limited efficacy, non-pharmacological approaches targeting the gut-brain axis have emerged as promising therapeutic avenues. The foundational element of this axis is gut microbiota dysbiosis, which manifests as reduced microbial diversity, a decrease in beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Akkermansia, and an increase in pro-inflammatory taxa like Proteobacteria (Loera-Valencia et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2021; Dhanawat et al., 2025). This section first systematically outlines the biological cascade through which gut dysbiosis drives AD pathology and then evaluates how various interventions can counteract this cascade.

2.1 The disease cascade: from gut dysbiosis to neural insult

The pathogenic sequence begins with gut dysbiosis, which initiates a multi-step cascade culminating in the hallmark pathologies of AD.

2.1.1 Barrier disruption and systemic inflammation

Dysbiosis disrupts intestinal barrier integrity, resulting in a “leaky gut” that permits the translocation of bacterial endotoxins, most notably LPS, into systemic circulation (Gates et al., 2022; Ticinesi et al., 2022). LPS and other inflammatory mediators promote a state of chronic systemic inflammation. This systemic inflammation, in turn, compromises the BBB, allowing neurotoxic agents to enter the CNS. Once in the brain, LPS activates microglia and astrocytes primarily through the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway, triggering a robust neuroinflammatory response (Li et al., 2024; Kamila et al., 2025).

2.1.2 Metabolite imbalance and key signaling pathways

Concurrently, dysbiosis disrupts the production of key microbial metabolites, reducing neuroprotective compounds while increasing neurotoxic ones.

SCFAs: SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate), produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber, are often depleted in AD. They exert anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects by inhibiting histone deacetylases (HDACs) to enhance synaptic plasticity genes (BDNF, SYN1) and by serving as ligands for free fatty acid receptors (FFAR2/3). Activation of FFAR2/3 on intestinal cells stimulates the release of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which can reduce neuroinflammation and improve insulin sensitivity (Bonfili et al., 2017; Zhang B. et al., 2022; Gasmi et al., 2025).

Tryptophan metabolites: Gut microbes metabolize tryptophan into bioactive indole derivatives (indole-3-acetic acid) and acid. These metabolites can activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), a key regulator of immune responses and barrier integrity. A dysbiosis-induced reduction in these AhR agonists contributes to increased oxidative stress, impaired gut barrier function, and heightened neuroinflammation (Zhang Z. et al., 2022; Chen S. et al., 2023; Jin et al., 2023).

2.1.3 Neuroinflammatory amplification and AD pathology

The influx of systemic inflammatory signals and the deficit of anti-inflammatory metabolites promote the polarization of microglia toward a pro-inflammatory “MGnD” phenotype. These activated microglia release cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which further enhance Aβ production via BACE1 upregulation and promote tau hyperphosphorylation through GSK-3β activation (Wei et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024). This creates a vicious cycle of neuroinflammation that directly fuels the core pathological triad of AD: Aβ accumulation, tau pathology, and neuronal loss.

2.2 Therapeutic interventions targeting the gut-brain axis

The mechanistic cascade described above provides a clear roadmap for interventions aimed at restoring gut-brain axis homeostasis. The following strategies have shown promise in preclinical and early clinical studies.

2.2.1 Probiotics and prebiotics

Specific probiotic strains directly modulate the gut-brain axis to ameliorate AD pathology. For example, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains have been shown to reduce Aβ plaques and tau phosphorylation by enhancing SCFA production and suppressing LPS-induced TLR4/NF-κB activation (Mosaferi et al., 2021b; Cox et al., 2022; Zhang S. et al., 2022). Clostridium butyricum is a notable butyrate-producing probiotic that ameliorates Aβ burden and microglial activation (Sun J. et al., 2020). Prebiotics, such as fructooligosaccharides and inulin, serve as fuel for these beneficial bacteria, promoting their growth and metabolic activity, thereby indirectly conferring neuroprotective effects.

2.2.2 Polyphenols and phytochemicals

Dietary phytochemicals exert multi-targeted effects. Resveratrol activates SIRT1 to suppress NF-κB signaling, while scutellarin modulates cAMP-PKA-CREB-HDAC3 signaling in microglia (Grinan-Ferre et al., 2021; Zhang S. et al., 2022). Flavonoids like isoorientin and cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (C3G) reshape the gut microbiota composition, decreasing the abundance of pro-inflammatory taxa, reducing circulating LPS and TNF-α, and improving gut barrier function (Zhang Z. et al., 2022; Oumeddour et al., 2024). Many of these compounds also possess direct antioxidant properties.

2.2.3 Dietary interventions

Comprehensive dietary patterns offer a powerful approach to modulating the gut ecosystem.

Mediterranean and high-fiber diets: These diets increase the abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria (Bacteroides), thereby elevating circulating SCFA levels, which is associated with lower Aβ and tau pathology (Gregory et al., 2023; Oumeddour et al., 2024).

Ketogenic diets: By shifting the body’s primary energy source to fats, ketogenic diets elevate neuroprotective ketone bodies and have been shown to enhance neurovascular function (Ma et al., 2018; Nanda et al., 2024).

Time-restricted eating: This intervention enriches beneficial mucin-degrading bacteria like Akkermansia and helps restore circadian rhythms, which are often disrupted in AD (Gasmi et al., 2025).

2.2.4 Physical exercise

Regular physical activity is a potent non-pharmacological intervention that boosts levels of Akkermansia muciniphila, enhances BBB integrity, increases the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and reduces gut permeability, thereby preventing the translocation of LPS into the circulation (Rosa et al., 2020; Mengoli et al., 2023).

2.2.5 Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)

FMT from healthy donors represents the most comprehensive approach to resetting the gut microbiome. Studies demonstrate that FMT can restore microbial diversity and SCFA production, suppress pro-inflammatory microglia, promote Aβ clearance, and improve cognitive function in AD models, providing direct evidence for the causal role of the gut microbiota (Grabrucker et al., 2023; Jin et al., 2023).

2.3 The influence of host factors and comorbidities

The efficacy of the interventions described above is not uniform and is significantly influenced by host factors. Gut microbiota composition and its associated cognitive impacts can vary by sex, as demonstrated by studies where the probiotic VSL#3 reduced Aβ plaques only in female APP/PS1 mice (Kaur et al., 2021). Furthermore, common comorbidities such as obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) exacerbate gut dysbiosis and systemic inflammation, thereby accelerating AD progression (Bonfili et al., 2020; Zhang S. et al., 2022). This underscores the necessity for personalized approaches that account for baseline gut microbiota composition, diet, sex, genetics, and co-existing medical conditions to optimize treatment response (Mosaferi et al., 2021a; Jiang et al., 2022; Chatterjee et al., 2024; Hediyal et al., 2024).

In summary, gut dysbiosis initiates a cascade involving barrier disruption, metabolite imbalance, and neuroinflammation that drives AD pathology. Non-pharmacological strategies counter this cascade through interconnected biological mechanisms that involve restoring gut microbial balance, enhancing gut and BBB integrity, increasing neuroprotective metabolites, and suppressing neuroinflammation via specific pathways such as FFAR2/3, TLR4, and AhR. Future research must prioritize human studies and personalized regimens to effectively halt AD progression Table 1.

3 Study limitations and research gaps in targeting the gut-brain axis in AD

Non-pharmacological interventions targeting the gut-brain axis represent a promising strategy for modulating AD progression. However, their clinical translation is impeded by substantial limitations in current research and critical knowledge gaps. This section provides a critical evaluation of these issues, emphasizing how the over-reliance on animal models, methodological inconsistencies, and insufficient exploration of host and environmental factors hinders a unified understanding of the interconnected gut-brain pathways in AD.

3.1 Study limitations

3.1.1 Over-reliance on animal models and limited human evidence

The field is dominated by preclinical studies utilizing transgenic mouse models (APP/PS1, SAMP8, ICV-STZ). While invaluable for mechanistic insight, these models poorly replicate the complexity of human gut-brain signaling, immune responses, and the multifactorial nature of sporadic AD. Species-specific differences in gut microbiota composition, lifespan, and neuroimmune pathways limit the direct translatability of findings (Lukiw et al., 2021; Su et al., 2023; Heydari et al., 2025). Human trials remain scarce and are often limited to small-scale, short-term pilot studies, as illustrated by one dietary intervention that was later retracted (Simopoulos et al., 2022). This heavy reliance on animal data creates a significant evidence gap between mechanistic promise and clinical efficacy.

3.1.2 Short intervention durations and methodological heterogeneity

Most intervention studies, particularly in animals, are short-term, typically lasting 3–8 weeks. This fails to mirror the chronic, decades-long progression of AD and does not assess the long-term sustainability of interventions. For instance, while quercetin improved cognition in mice after 21 days, real-world preventive strategies would require years of sustained intervention (Westfall et al., 2019; Altendorfer et al., 2025). Furthermore, methodological heterogeneity, such as the use of varying probiotic strains, doses, and administration routes, complicates cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses. The strain-specific and route-dependent efficacy of interventions, exemplified by Lactobacillus rhamnosus in AD rats and the oral-specific effects of walnut peptide PW5, highlights the challenge of standardizing protocols (Li et al., 2022; Simopoulos et al., 2022).

3.1.3 Inadequate consideration of confounding host and environmental factors

A major limitation is the frequent oversight of critical variables that shape the gut-brain axis in humans. Many preclinical studies use male-biased cohorts, overlooking documented sex-specific responses; for example, the probiotic VSL#3 reduced Aβ plaques only in female APP/PS1 mice, yet the underlying mechanisms for this disparity remain uninvestigated (Gao et al., 2019; Ruotolo et al., 2020; Pluta et al., 2022). Moreover, common comorbidities in AD patients, such as obesity, T2DM, and cardiovascular disease, are known to exacerbate gut dysbiosis and systemic inflammation, yet they are often controlled for inadequately or not at all in experimental designs. The profound influence of diet and medications (antibiotics, metformin) on gut microbiota is rarely accounted for, making it difficult to isolate the effect of the intervention itself and to establish clear causal relationships.

3.1.4 Incomplete mechanistic insight and oversimplification of pathways

Many studies report correlations, such as between a rise in Akkermansia and reduced Aβ, without establishing definitive causality or elucidating the precise signaling pathways. For example, although Akkermansia muciniphila improves cognition, the neuroprotective role of its extracellular vesicles (EVs) and their specific cargo (miRNAs, proteins) are not fully understood (Ou et al., 2020; Cecarini et al., 2021; He et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2025). The mechanisms by which microbial metabolites like SCFAs cross the BBB and interact with neural receptors (FFAR2/3) remain poorly defined. There is also a tendency to investigate pathways in isolation, neglecting the complex crosstalk between, for instance, SCFA receptor signaling, TLR4 activation, and AhR pathways. Finally, the research focus has been disproportionately centered on amyloid and tau pathology, often neglecting other critical AD-related mechanisms such as neurovascular dysfunction, oxidative stress, and synaptic integrity (Linjuan et al., 2024).

3.2 Research gaps

3.2.1 Need for robust human trials and mechanistic depth in human context

There is an urgent, unmet need for large-scale, long-duration randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in humans. Current evidence relies heavily on animal studies, with only a few early-phase trials testing human-derived probiotic cocktails (Kaur et al., 2020; Su et al., 2023). Future human trials must incorporate multi-omics profiling (metagenomics, metabolomics, proteomics) to move beyond correlation and validate biomarkers and signaling pathways within the human context. Key mechanistic questions to be addressed in human-relevant models include: How do microbial metabolites like TMAO and SCFAs cross the BBB? How does bacterial LPS directly interact with Aβ to drive aggregation and neuroinflammation? How do bacterial EVs transmit signals via the vagus nerve? (Kaur et al., 2020; Cecarini et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021; Zhang K. et al., 2022; Chen Y. Y. et al., 2023).

3.2.2 Development of personalized and stratified medicine approaches

The “one-size-fits-all” approach is unlikely to succeed given the high inter-individual variability of the gut microbiome. A critical gap is the development of personalized treatment strategies that account for host-microbiome interactions. This includes stratifying patients by genetic factors such as vitamin D receptor (VDR) polymorphisms and APOE4 status, as these can dramatically alter responses to interventions like vitamin D or omega-3 supplementation (Lawrence and Hyde, 2017; Ma et al., 2018; Rosa et al., 2020; Yang S. et al., 2020; Kaur et al., 2021; He et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Prajapati et al., 2025). Genotype-stratified trials enrolling patients at the mild cognitive impairment (MCI) stage are needed to identify responsive subgroups and optimize therapeutic efficacy.

3.2.3 Expansion of therapeutic targets and modalities

Therapeutic approaches must extend beyond amyloid-centricity to include tau pathology, neurovascular health, and sustained control of neuroinflammation. Research into synbiotic formulations (combinations of inulin and eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA]) represents a promising multi-target strategy that requires further exploration. Furthermore, long-term safety evaluations are essential, particularly regarding the risks of antibiotic-induced dysbiosis, the persistence of probiotic strains, and the potential for certain microbes like Clostridium scindens to produce neurotoxic secondary bile acids.

3.2.4 Integration of multimodal interventions and early prevention strategies

A significant gap lies in understanding the synergy between gut-targeted therapies and other non-pharmacological modalities. Research is needed to study the combined effects of, for example, butyrate-producing probiotics and aerobic exercise, or between ketogenic diets and SCFA signaling (Alexandrov et al., 2020; Ruotolo et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022; Altendorfer et al., 2025). Finally, the field must shift towards early prevention, investigating whether interventions in pre-symptomatic at-risk populations (APOE4 carriers) or even during critical developmental windows (perinatal microbiome programming) can engineer resilience against future AD pathology.

While non-pharmacological interventions targeting the gut microbiome hold significant potential, clinical translation is currently hindered by a nexus of limitations including poor model translatability, short study durations, methodological inconsistencies, and incomplete mechanistic insight. Future studies must prioritize well-designed human RCTs that incorporate deep phenotyping, focus on personalized protocols, and develop multimodal strategies that synergistically target the gut-brain axis at multiple levels to effectively modify the course of AD.

4 Prospective studies targeting the gut-brain axis in AD

Building on the compelling preclinical evidence and the critical gaps identified in Section 3, this section outlines a strategic roadmap for future research to translate gut-brain axis modulation into viable clinical strategies for AD. The priorities are designed to move beyond correlation to causation, bridge the translational gap between animal and human studies, and embrace the complexity of host-environment-microbiome interactions through personalized and multimodal approaches.

4.1 Human trials and dietary interventions

To address the critical lack of robust human evidence, large-scale, long-term RCTs are urgently needed. These trials should move beyond short-term pilot studies and investigate interventions with strong mechanistic backing, such as Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation, human-origin probiotic cocktails, or synbiotics, over periods of 12 to 24 months in cohorts with early AD or MCI. Outcomes must be comprehensive, including cognitive decline (ADAS-Cog), core AD pathology (via Aβ and tau PET imaging), systemic and central inflammatory cytokines, and gut permeability markers (zonulin). Such rigorous designs are essential for validating preclinical promises.

Concurrently, dietary interventions must be tested in high-risk populations, such as APOE4 carriers, with consideration for common comorbidities like obesity and T2DM. Prospective studies should evaluate combined regimens, for example, a Mediterranean-ketogenic diet hybrid supplemented with omega-3 EPA, for 18 months or longer. Primary outcomes should target the interplay between metabolism and brain health, including brain glucose metabolism (via FDG-PET), serum levels of gut-derived metabolites like trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), and longitudinal changes in gut microbiome diversity. This approach directly addresses the gap in long-term, human-relevant dietary studies that account for host genetics and comorbidity interactions.

4.2 Elucidating mechanistic pathways and developing personalized approaches

Future research must dissect the precise mechanisms of gut-brain communication to identify novel therapeutic targets. A key priority is to isolate and characterize bacterial EVs from beneficial strains like Lactobacillus johnsonii or Akkermansia muciniphila. Studies should track their biodistribution to the CNS in primate models using fluorescent labeling and analyze their cargo (miRNAs, proteins) to determine how they suppress microglial activation via NF-κB/TLR4 pathways or promote neuronal integrity.

Furthermore, the signaling of microbial metabolites must be delineated with greater precision. Employing FFAR2/3 knockout mice would allow researchers to dissect the specific contribution of SCFA receptor signaling to microglial function, particularly in Aβ phagocytosis via downstream pathways like NRF2/SOD1. This preclinical work should be integrated with clinical translation: collecting fecal samples from AD patients before and after SCFA supplementation for metatranscriptomic analysis can identify receptor-specific microbial gene expression changes, bridging mechanistic insight from bench to bedside.

Given the variability in treatment response, personalized approaches are paramount. Prospective trials should recruit patients with amnestic MCI (aMCI) and stratify them by genetic factors such as vitamin D receptor (VDR) SNPs (rs1544410) or APOE4 status. This allows for testing genotype-informed interventions, such as combinations of quercetin and vitamin D or specific probiotic formulations. These studies should monitor intermediary outcomes like serum 25(OH)D levels, gut microbiota shifts (Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio), and hippocampal BDNF levels to understand how host genetics modifies therapeutic efficacy.

To operationalize precision medicine, future research must leverage artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. Developing algorithms that integrate baseline multi-omics data (metagenomics, metabolomics) can predict an individual’s response to interventions like FMT from young donors or specific flavonoid metabolites. The goal is to move from a universal protocol to a predictive model that guides therapy based on an individual’s unique microbiome and metabolic signature.

4.3 Integrated multimodal strategies and early intervention paradigms

The complexity of AD necessitates combinatorial approaches. Future studies should investigate synergistic interventions that target the gut-brain axis through multiple, reinforcing mechanisms. For instance, an “exercise-microbiome synergy” study could combine structured aerobic exercise with Clostridium butyricum supplementation in both APP/PS1 mice and AD patients, measuring synergistic effects on synaptic plasticity (long-term potentiation), colonic butyrate levels, and BBB integrity (measured by S100β). The hypothesis is that exercise amplifies the probiotic-induced increase in neuroprotective SCFAs.

Another innovative approach is a “diet-probiotic-device triad,” testing a combination of a ketogenic diet, the multi-strain probiotic VSL#3, and transcranial light therapy in mild AD. This would evaluate outcomes related to mitochondrial biogenesis (PGC-1α), NLRP3 inflammasome suppression, and fecal Akkermansia abundance, based on the rationale that diet-microbe interactions can be enhanced by direct neuromodulation.

Prospective research must also prioritize early intervention. This includes enrolling pre-symptomatic APOE4 carriers (cognitively normal adults aged 50–60) for long-term (5-year) interventions using agents like inulin prebiotic or curcumin, aiming to dampen neuroinflammation decades before clinical symptom onset. Primary outcomes should include plasma neurofilament light (NfL), hippocampal volume loss, and levels of immunogenic molecules like Bacteroides fragilis LPS.

Finally, the integration of digital health technologies is crucial for advancing monitoring and personalization. Prospective research should employ digital phenotyping platforms that combine wearable sensors (for sleep and activity), smartphone-based cognitive tests, and frequent fecal metabolomics (GC–MS). Using machine learning to analyze this dense longitudinal data can help predict individual disease trajectories and optimize interventions in real-time, creating a dynamic, closed-loop system for managing AD risk.

4.4 Concluding research outlook

Prospective research must bridge preclinical promise with clinical rigor by prioritizing large-scale human trials with multi-omics depth, elucidating the specific roles of bacterial EVs and metabolite-receptor interactions, personalizing interventions via host genetics and AI-driven microbiome phenotyping, and testing synergistic multimodal regimens. By targeting early disease stages and leveraging digital tools for monitoring, future studies can transcend Aβ-centric models and fully leverage the modifiable gut-brain axis as a pivotal target for the prevention and treatment of AD.

5 Conclusion

The evidence synthesized in this review firmly establishes the gut-brain axis as a central and modifiable pathway in AD pathogenesis. Moving beyond correlation, studies demonstrating that fecal microbiota transplantation from AD patients can induce cognitive deficits and neuropathology in healthy rodents provide compelling evidence of a causal relationship. The underlying mechanisms are multifaceted, centering on dysbiosis-induced compromise of the intestinal and BBB. This breach facilitates systemic inflammation and the influx of neurotoxic agents like LPS, while simultaneously disrupting the production of key microbial metabolites. The resultant deficit in neuroprotective SCFAs and indoles, coupled with an upsurge in pro-inflammatory mediators, directly fuels the core pathological triad of AD: chronic neuroinflammation, Aβ accumulation, and tau pathology.

Therapeutic targeting of this axis holds significant promise. Interventions such as specific probiotics (Clostridium butyricum), anti-inflammatory diets, polyphenols, and physical exercise have demonstrated efficacy in preclinical and early clinical settings by restoring eubiosis, enhancing barrier integrity, and suppressing neuroinflammatory cascades. However, the translation of these findings into mainstream clinical practice faces substantial hurdles. The field is currently constrained by an overreliance on animal models with limited translatability, a preponderance of short-term intervention studies, and a critical lack of large-scale, standardized human trials. Furthermore, methodological heterogeneity and an often-oversimplified view of microbiome-host interactions obscure precise mechanistic insights and hinder the reproducibility of outcomes.

To fully realize the therapeutic potential of the gut-brain axis, future research must be guided by a new paradigm. This entails a decisive shift towards large-scale, long-duration randomized controlled trials in human populations, with a particular focus on early disease stages. Achieving greater mechanistic depth through integrated multi-omics approaches is essential to delineate the precise signaling pathways, such as FFAR2/3, TLR4, and AhR, by which gut-derived metabolites influence brain health. Ultimately, the future of AD intervention lies in personalized medicine; strategies must account for host genetics, baseline microbiome composition, and comorbidities to develop effective, synergistic multimodal regimens. By addressing these critical gaps, modulation of the gut-brain axis can evolve from a compelling scientific concept into a tangible and powerful strategy for the prevention and treatment of AD.

Author contributions

RQ: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. CL: Writing – review & editing. XY: Writing – review & editing. YC: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. National Science Foundation of China (82474650 and 82074530) and Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Project of Heilongjiang Province (ZHY2023-189).

Acknowledgments

Figure was created in https://BioRender.com.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alexandrov, P. N., Hill, J. M., Zhao, Y., Bond, T., Taylor, C. M., Percy, M. E., et al. (2020). Aluminum-induced generation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from the human gastrointestinal (GI)-tract microbiome-resident Bacteroides fragilis. J. Inorg. Biochem. 203:110886. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2019.110886

Altendorfer, B., Benedetti, A., Mrowetz, H., Bernegger, S., Bretl, A., Preishuber-Pflugl, J., et al. (2025). Omega-3 EPA supplementation shapes the gut microbiota composition and reduces major histocompatibility complex class II in aged wild-type and APP/PS1 Alzheimer's mice: a pilot experimental study. Nutrients 17:1108. doi: 10.3390/nu17071108

Amin, N., Liu, J., Bonnechere, B., MahmoudianDehkordi, S., Arnold, M., Batra, R., et al. (2023). Interplay of metabolome and gut microbiome in individuals with major depressive disorder vs control individuals. JAMA Psychiatry 80, 597–609. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0685

Bonfili, L., Cecarini, V., Berardi, S., Scarpona, S., Suchodolski, J. S., Nasuti, C., et al. (2017). Microbiota modulation counteracts Alzheimer's disease progression influencing neuronal proteolysis and gut hormones plasma levels. Sci. Rep. 7:2426. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02587-2

Bonfili, L., Cecarini, V., Gogoi, O., Berardi, S., Scarpona, S., Angeletti, M., et al. (2020). Gut microbiota manipulation through probiotics oral administration restores glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 87, 35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.11.004

Bonfili, L., Cuccioloni, M., Gong, C., Cecarini, V., Spina, M., Zheng, Y., et al. (2022). Gut microbiota modulation in Alzheimer's disease: focus on lipid metabolism. Clin. Nutr. 41, 698–708. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2022.01.025

Cecarini, V., Cuccioloni, M., Zheng, Y., Bonfili, L., Gong, C., Angeletti, M., et al. (2021). Flavan-3-ol microbial metabolites modulate proteolysis in neuronal cells reducing amyloid-beta (1-42) levels. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 65:e2100380. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.202100380

Chatterjee, A., Kumar, S., Roy Sarkar, S., Halder, R., Kumari, R., Banerjee, S., et al. (2024). Dietary polyphenols represent a phytotherapeutic alternative for gut dysbiosis associated neurodegeneration: a systematic review. J. Nutr. Biochem. 129:109622. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2024.109622

Chen, Y. Y., Chen, S. Y., Lin, J. A., and Yen, G. C. (2023). Preventive effect of Indian gooseberry (Phyllanthus emblica L.) fruit extract on cognitive decline in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 67:e2200791. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.202200791

Chen, S., Lei, Q., Zou, X., and Ma, D. (2023). The role and mechanisms of gram-negative bacterial outer membrane vesicles in inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 14:1157813. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1157813

Cox, L. M., Calcagno, N., Gauthier, C., Madore, C., Butovsky, O., and Weiner, H. L. (2022). The microbiota restrains neurodegenerative microglia in a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Microbiome 10:47. doi: 10.1186/s40168-022-01232-z

Denman, C. R., Park, S. M., and Jo, J. (2023). Gut-brain axis: gut dysbiosis and psychiatric disorders in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Front. Neurosci. 17:1268419. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2023.1268419

Dhanawat, M., Malik, G., Wilson, K., Gupta, S., Gupta, N., and Sardana, S. (2025). The gut microbiota-brain Axis: a new frontier in Alzheimer's disease pathology. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 24, 7–20. doi: 10.2174/0118715273302508240613114103

Erny, D., Dokalis, N., Mezo, C., Castoldi, A., Mossad, O., Staszewski, O., et al. (2021). Microbiota-derived acetate enables the metabolic fitness of the brain innate immune system during health and disease. Cell Metab. 33, 2260–2276.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.10.010

Fei, Y., Wang, R., Lu, J., Peng, S., Yang, S., Wang, Y., et al. (2023). Probiotic intervention benefits multiple neural behaviors in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Geriatr. Nurs. 51, 167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2023.03.006

Gao, Q., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Fu, S., Zhang, X., Wang, R. T., et al. (2019). Decreased levels of circulating trimethylamine N-oxide alleviate cognitive and pathological deterioration in transgenic mice: a potential therapeutic approach for Alzheimer's disease. Aging 11, 8642–8663. doi: 10.18632/aging.102352

Gasmi, M., Silvia Hardiany, N., van der Merwe, M., Martins, I. J., Sharma, A., and Williams-Hooker, R. (2025). The influence of time-restricted eating/feeding on Alzheimer's biomarkers and gut microbiota. Nutr. Neurosci. 28, 156–170. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2024.2359868

Gates, E. J., Bernath, A. K., and Klegeris, A. (2022). Modifying the diet and gut microbiota to prevent and manage neurodegenerative diseases. Rev. Neurosci. 33, 767–787. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2021-0146

Grabrucker, S., Marizzoni, M., Silajdzic, E., Lopizzo, N., Mombelli, E., Nicolas, S., et al. (2023). Microbiota from Alzheimer's patients induce deficits in cognition and hippocampal neurogenesis. Brain 146, 4916–4934. doi: 10.1093/brain/awad303

Gregory, S., Blennow, K., Ritchie, C. W., Shannon, O. M., Stevenson, E. J., and Muniz-Terrera, G. (2023). Mediterranean diet is associated with lower white matter lesion volume in Mediterranean cities and lower cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 in non-Mediterranean cities in the EPAD LCS cohort. Neurobiol. Aging 131, 29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2023.07.012

Grinan-Ferre, C., Bellver-Sanchis, A., Izquierdo, V., Corpas, R., Roig-Soriano, J., Chillon, M., et al. (2021). The pleiotropic neuroprotective effects of resveratrol in cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease pathology: from antioxidant to epigenetic therapy. Ageing Res. Rev. 67:101271. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101271

Hao, W., Luo, Q., Tomic, I., Quan, W., Hartmann, T., Menger, M. D., et al. (2024). Modulation of Alzheimer's disease brain pathology in mice by gut bacterial depletion: the role of IL-17a. Gut Microbes 16:2363014. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2363014

He, X., Yan, C., Zhao, S., Zhao, Y., Huang, R., and Li, Y. (2022). The preventive effects of probiotic Akkermansia muciniphila on D-galactose/AlCl3 mediated Alzheimer's disease-like rats. Exp. Gerontol. 170:111959. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2022.111959

Hediyal, T. A., Vichitra, C., Anand, N., Bhaskaran, M., Essa, S. M., Kumar, P., et al. (2024). Protective effects of fecal microbiota transplantation against ischemic stroke and other neurological disorders: an update. Front. Immunol. 15:1324018. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1324018

Heydari, R., Khosravifar, M., Abiri, S., Dashtbin, S., Alvandi, A., Nedaei, S. E., et al. (2025). A domestic strain of Lactobacillus rhamnosus attenuates cognitive deficit and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in an animal model of Alzheimer's disease. Behav. Brain Res. 476:115277. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2024.115277

Jiang, H., Chen, C., and Gao, J. (2022). Extensive summary of the important roles of indole propionic acid, a gut microbial metabolite in host health and disease. Nutrients 15:151. doi: 10.3390/nu15010151

Jin, Y., Kim, T., and Kang, H. (2023). Forced treadmill running modifies gut microbiota with alleviations of cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease pathology in 3xTg-AD mice. Physiol. Behav. 264:114145. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2023.114145

Kamatham, P. T., Shukla, R., Khatri, D. K., and Vora, L. K. (2024). Pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapeutics for Alzheimer's disease: breaking the memory barrier. Ageing Res. Rev. 101:102481. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2024.102481

Kamila, P., Kar, K., Chowdhury, S., Chakraborty, P., Dutta, R. S., et al. (2025). Effect of neuroinflammation on the progression of Alzheimer’s disease and its significant ramifications for novel anti-inflammatory treatments. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 18, 771–782. doi: 10.1016/j.ibneur.2025.05.005

Kaur, H., Nagamoto-Combs, K., Golovko, S., Golovko, M. Y., Klug, M. G., and Combs, C. K. (2020). Probiotics ameliorate intestinal pathophysiology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 92, 114–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.04.009

Kaur, H., Nookala, S., Singh, S., Mukundan, S., Nagamoto-Combs, K., and Combs, C. K. (2021). Sex-dependent effects of intestinal microbiome manipulation in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Cells 10:2370. doi: 10.3390/cells10092370

Kim, D. S., Zhang, T., and Park, S. (2022). Protective effects of Forsythiae fructus and Cassiae semen water extract against memory deficits through the gut-microbiome-brain axis in an Alzheimer's disease model. Pharm. Biol. 60, 212–224. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2022.2025860

Knopman, D. S., Amieva, H., Petersen, R. C., Chételat, G., Holtzman, D. M., Hyman, B. T., et al. (2021). Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 7:33. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00269-y

Lawrence, K., and Hyde, J. (2017). Microbiome restoration diet improves digestion, cognition and physical and emotional wellbeing. PLoS One 12:e0179017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179017

Li, S., Cai, Y., Guan, T., Zhang, Y., Huang, K., Zhang, Z., et al. (2024). Quinic acid alleviates high-fat diet-induced neuroinflammation by inhibiting DR3/IKK/NF-kappaB signaling via gut microbial tryptophan metabolites. Gut Microbes 16:2374608. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2374608

Li, J., Liao, X., Yin, X., Deng, Z., Hu, G., Zhang, W., et al. (2022). Gut microbiome and serum metabolome profiles of capsaicin with cognitive benefits in APP/PS1 mice. Nutrients 15:118. doi: 10.3390/nu15010118

Linjuan, S., Chengfu, L. I., Jiangang, L., Nannan, L. I., Fuhua, H., Dandan, Q., et al. (2024). Efficacy of Sailuotong on neurovascular unit in amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 transgenic mice with Alzheimer's disease. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 44, 289–302. doi: 10.19852/j.cnki.jtcm.20240203.007

Loera-Valencia, R., Cedazo-Minguez, A., Kenigsberg, P. A., Page, G., Duarte, A. I., Giusti, P., et al. (2019). Current and emerging avenues for Alzheimer's disease drug targets. J. Intern. Med. 286, 398–437. doi: 10.1111/joim.12959

Lukiw, W. J., Arceneaux, L., Li, W., Bond, T., and Zhao, Y. (2021). Gastrointestinal (GI)-tract microbiome derived neurotoxins and their potential contribution to inflammatory neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease (AD). J. Alzheimers Dis. Parkinsonism. 11:525. doi: 10.4172/2161-0460.1000525

Ma, H., Qiao, Q., Yu, Z., Wang, W., Li, Z., Xie, Z., et al. (2025). Integrated multi-omics analysis and experimental validation reveals the mechanism of tenuifoliside a activity in Alzheimer's disease. J. Ethnopharmacol. 347:119797. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2025.119797

Ma, D., Wang, A. C., Parikh, I., Green, S. J., Hoffman, J. D., Chlipala, G., et al. (2018). Ketogenic diet enhances neurovascular function with altered gut microbiome in young healthy mice. Sci. Rep. 8:6670. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25190-5

Marizzoni, M., Cattaneo, A., Mirabelli, P., Festari, C., Lopizzo, N., Nicolosi, V., et al. (2020). Short-chain fatty acids and lipopolysaccharide as mediators between gut Dysbiosis and amyloid pathology in Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 78, 683–697. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200306

Marizzoni, M., Mirabelli, P., Mombelli, E., Coppola, L., Festari, C., Lopizzo, N., et al. (2023). A peripheral signature of Alzheimer's disease featuring microbiota-gut-brain axis markers. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 15:101. doi: 10.1186/s13195-023-01218-5

Markulin, I., Matasin, M., Turk, V. E., and Salkovic-Petrisic, M. (2022). Challenges of repurposing tetracyclines for the treatment of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 129, 773–804. doi: 10.1007/s00702-021-02457-2

McGrattan, A. M., McGuinness, B., McKinley, M. C., Kee, F., Passmore, P., Woodside, J. V., et al. (2019). Diet and inflammation in cognitive ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 8, 53–65. doi: 10.1007/s13668-019-0271-4

Mengoli, M., Conti, G., Fabbrini, M., Candela, M., Brigidi, P., Turroni, S., et al. (2023). Microbiota-gut-brain axis and ketogenic diet: how close are we to tackling epilepsy? Microbiome Res. Rep. 2:32. doi: 10.20517/mrr.2023.24

Mosaferi, B., Jand, Y., and Salari, A. A. (2021a). Antibiotic-induced gut microbiota depletion from early adolescence exacerbates spatial but not recognition memory impairment in adult male C57BL/6 mice with Alzheimer-like disease. Brain Res. Bull. 176, 8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2021.08.004

Mosaferi, B., Jand, Y., and Salari, A. A. (2021b). Gut microbiota depletion from early adolescence alters anxiety and depression-related behaviours in male mice with Alzheimer-like disease. Sci. Rep. 11:22941. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02231-0

Nakhal, M. M., Yassin, L. K., Alyaqoubi, R., Saeed, S., Alderei, A., Alhammadi, A., et al. (2024). The microbiota-gut-brain Axis and neurological disorders: a comprehensive review. Life 14:1234. doi: 10.3390/life14101234

Nanda, M., Pradhan, G., Singh, V., and Barve, K. (2024). Ketogenic diets: answer to life-threatening neurological diseases. Food Humanity 3:100364. doi: 10.1016/j.foohum.2024.100364

Nicolas, S., Dohm-Hansen, S., Lavelle, A., Bastiaanssen, T. F. S., English, J. A., Cryan, J. F., et al. (2024). Exercise mitigates a gut microbiota-mediated reduction in adult hippocampal neurogenesis and associated behaviours in rats. Transl. Psychiatry 14:195. doi: 10.1038/s41398-024-02904-0

Ou, Z., Deng, L., Lu, Z., Wu, F., Liu, W., Huang, D., et al. (2020). Protective effects of Akkermansia muciniphila on cognitive deficits and amyloid pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Nutr. Diabetes 10:12. doi: 10.1038/s41387-020-0115-8

Oumeddour, D. Z., Al-Dalali, S., Zhao, L., Zhao, L., and Wang, C. (2024). Recent advances on cyanidin-3-O-glucoside in preventing obesity-related metabolic disorders: a comprehensive review. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 729:150344. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.150344

Pluta, R., Furmaga-Jablonska, W., Januszewski, S., and Czuczwar, S. J. (2022). Post-ischemic brain neurodegeneration in the form of Alzheimer's disease Proteinopathy: possible therapeutic role of curcumin. Nutrients 14:248. doi: 10.3390/nu14020248

Prajapati, S. K., Wang, S., Mishra, S. P., Jain, S., and Yadav, H. (2025). Protection of Alzheimer's disease progression by a human-origin probiotics cocktail. Sci. Rep. 15:1589. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-84780-8

Rosa, J. M., Pazini, F. L., Camargo, A., Wolin, I. A. V., Olescowicz, G., Eslabao, L. B., et al. (2020). Prophylactic effect of physical exercise on Abeta(1-40)-induced depressive-like behavior and gut dysfunction in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 393:112791. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2020.112791

Ruotolo, R., Minato, I., La Vitola, P., Artioli, L., Curti, C., Franceschi, V., et al. (2020). Flavonoid-derived human phenyl-gamma-Valerolactone metabolites selectively detoxify amyloid-beta oligomers and prevent memory impairment in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 64:e1900890. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201900890

Sharma, V. K., Singh, T. G., Garg, N., Dhiman, S., Gupta, S., Rahman, M. H., et al. (2021). Dysbiosis and Alzheimer's disease: a role for chronic stress? Biomolecules 11:678. doi: 10.3390/biom11050678

Simopoulos, C. M. A., Ning, Z., Li, L., Khamis, M. M., Zhang, X., Lavallee-Adam, M., et al. (2022). MetaProClust-MS1: an MS1 profiling approach for large-scale microbiome screening. mSystems 7:e0038122. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00381-22

Su, X., Chen, Y., and Yuan, X. (2025). Gut microbiota modulation of dementia related complications. Aging Dis. doi: 10.14336/ad.2025.0108

Su, Y., Wang, D., Liu, N., Yang, J., Sun, R., and Zhang, Z. (2023). Clostridium butyricum improves cognitive dysfunction in ICV-STZ-induced Alzheimer's disease mice via suppressing TLR4 signaling pathway through the gut-brain axis. PLoS One 18:e0286086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0286086

Sun, M., Ma, K., Wen, J., Wang, G., Zhang, C., Li, Q., et al. (2020). A review of the brain-gut-microbiome axis and the potential role of microbiota in Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 73, 849–865. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190872

Sun, J., Xu, J., Yang, B., Chen, K., Kong, Y., Fang, N., et al. (2020). Effect of Clostridium butyricum against microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease via regulating gut microbiota and metabolites butyrate. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 64:e1900636. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201900636

Ticinesi, A., Mancabelli, L., Carnevali, L., Nouvenne, A., Meschi, T., Del Rio, D., et al. (2022). Interaction between diet and microbiota in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's disease: focus on polyphenols and dietary fibers. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 86, 961–982. doi: 10.3233/JAD-215493

Varesi, A., Carrara, A., Pires, V. G., Floris, V., Pierella, E., Savioli, G., et al. (2022). Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis and progression: an overview. Cells 11:1367. doi: 10.3390/cells11081367

Wang, M., Amakye, W. K., Gong, C., Ren, Z., Yuan, E., and Ren, J. (2022). Effect of oral and intraperitoneal administration of walnut-derived pentapeptide PW5 on cognitive impairments in APP(SWE)/PS1(DeltaE9) mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 180, 191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.01.003

Wang, C., Lau, C. Y., Ma, F., and Zheng, C. (2021). Genome-wide screen identifies curli amyloid fibril as a bacterial component promoting host neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118:e2106504118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2106504118

Wei, Z., Li, D., and Shi, J. (2023). Alterations of spatial memory and gut microbiota composition in Alzheimer's disease triple-transgenic mice at 3, 6, and 9 months of age. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 38:15333175231174193. doi: 10.1177/15333175231174193

Westfall, S., Lomis, N., and Prakash, S. (2019). A novel synbiotic delays Alzheimer's disease onset via combinatorial gut-brain-axis signaling in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One 14:e0214985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214985

Yang, X., Yu, D., Xue, L., Li, H., and Du, J. (2020). Probiotics modulate the microbiota-gut-brain axis and improve memory deficits in aged SAMP8 mice. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 10, 475–487. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.07.001

Yang, S., Zhou, H., Wang, G., Zhong, X. H., Shen, Q. L., Zhang, X. J., et al. (2020). Quercetin is protective against short-term dietary advanced glycation end products intake induced cognitive dysfunction in aged ICR mice. J. Food Biochem. 44:e13164. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13164

Zhang, B., Chen, T., Cao, M., Yuan, C., Reiter, R. J., Zhao, Z., et al. (2022). Gut microbiota dysbiosis induced by decreasing endogenous melatonin mediates the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease and obesity. Front. Immunol. 13:900132. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.900132

Zhang, K., Ma, X., Zhang, R., Liu, Z., Jiang, L., Qin, Y., et al. (2022). Crosstalk between gut microflora and vitamin D receptor SNPs are associated with the risk of amnestic mild cognitive impairment in a Chinese elderly population. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 88, 357–373. doi: 10.3233/JAD-220101

Zhang, Z., Tan, X., Sun, X., Wei, J., Li, Q. X., and Wu, Z. (2022). Isoorientin affects markers of Alzheimer's disease via effects on the Oral and gut microbiota in APP/PS1 mice. J. Nutr. 152, 140–152. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab328

Zhang, S., Wei, D., Lv, S., Wang, L., An, H., Shao, W., et al. (2022). Scutellarin modulates the microbiota-gut-brain Axis and improves cognitive impairment in APP/PS1 mice. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 89, 955–975. doi: 10.3233/JAD-220532

Zhao, X., Kong, M., Wang, Y., Mao, Y., Xu, H., He, W., et al. (2023). Nicotinamide mononucleotide improves the Alzheimer's disease by regulating intestinal microbiota. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 670, 27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2023.05.075

Zheng, M., Ye, H., Yang, X., Shen, L., Dang, X., Liu, X., et al. (2024). Probiotic Clostridium butyricum ameliorates cognitive impairment in obesity via the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Brain Behav. Immun. 115, 565–587. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2023.11.016

Glossary

AD - Alzheimer’s disease

ADAS-Cog - Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale-cognitive subscale

AhR - aryl hydrocarbon receptor

aMCI - amnestic mild cognitive impairment

Aβ - amyloid-beta

BBB - blood–brain barrier

BDNF - brain-derived neurotrophic factor

C3G - cyanidin-3-O-glucoside

CNS - central nervous system

DR3 - death receptor 3

EPA - eicosapentaenoic acid

EVs - extracellular vesicles

FDG-PET - fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

FFAR2/3 - free fatty acid receptor 2/3

FMT - fecal microbiota transplantation

GC–MS - gas chromatography–mass spectrometry

GLP-1 - glucagon-like peptide-1

GPCRs - G-protein coupled receptors

GSK-3β - glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta

HDACs - histone deacetylases

IAA - indole-3-acetic acid

ICV-STZ - intracerebroventricular-streptozotocin

IKK - IκB kinase

IL-10 - interleukin-10

KYNA - kynurenic acid

LPS - lipopolysaccharide

MCT - medium-chain triglycerides

MCI - mild cognitive impairment

MGnD - microglial neurodegenerative phenotype

miRNAs - microRNAs

NfL - neurofilament light chain

NF-κB - nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

NLRP3 - NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3

NRF2 - nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2

PET - positron emission tomography

PGC-1α - peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha

PVLs - phenyl-γ-valerolactones

RCTs - randomized controlled trials

ROS - reactive oxygen species

SCFAs - short-chain fatty acids

SIRT1 - sirtuin 1

SNPs - single nucleotide polymorphisms

SOD1 - superoxide dismutase 1

SYN1 - synapsin I

T2DM - type 2 diabetes mellitus

TLR4 - toll-like receptor 4

TMAO - trimethylamine N-oxide

TNF-α - tumor necrosis factor alpha

VDR - vitamin D receptor

Keywords: gut-brain axis, Alzheimer’s disease, microbiome dysbiosis, neuroinflammation, short-chain fatty acids

Citation: Qin R, Li C, Yuan X and Chen Y (2025) Microbiome-targeted Alzheimer’s interventions via gut-brain axis. Front. Microbiol. 16:1729708. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1729708

Edited by:

Laura Mitrea, University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine of Cluj-Napoca, RomaniaReviewed by:

Ami Thakkar, SVKM’s Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies, IndiaToheeb Kazeem, Federal University of Technology, Nigeria

Copyright © 2025 Qin, Li, Yuan and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xingxing Yuan, eXVhbnhpbmd4aW5nQGhsanVjbS5lZHUuY24=; Yinghua Chen, Y2hlbnlpbmdodWFAaGxqdWNtLmVkdS5jbg==

Ruiqi Qin1,2

Ruiqi Qin1,2 Xingxing Yuan

Xingxing Yuan