Abstract

Purpose:

The study aimed to identify potential risk factors for aneurysm rupture by performing a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Materials and methods:

We systematically searched the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library electronic databases for eligible studies from their inception until June 2023.

Results:

Eighteen studies involving 17,069 patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysm (UIA) and 2,699 aneurysm ruptures were selected for the meta-analysis. Hyperlipidemia [odds ratio (OR): 0.47; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.39–0.56; p < 0.001] and a family history of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (OR: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.71–0.91; p = 0.001) were associated with a reduced risk of aneurysm rupture. In contrast, a large-size aneurysm (OR: 4.49; 95% CI: 2.46–8.17; p < 0.001), ACA (OR: 3.34; 95% CI: 1.94–5.76; p < 0.001), MCA (OR: 2.16; 95% CI: 1.73–2.69; p < 0.001), and VABA (OR: 2.20; 95% CI: 1.24–3.91; p = 0.007) were associated with an increased risk of aneurysm rupture. Furthermore, the risk of aneurysm rupture was not affected by age, sex, current smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, a history of SAH, and multiple aneurysms.

Conclusion:

This study identified the predictors of aneurysm rupture in patients with UIAs, including hyperlipidemia, a family history of SAH, a large-size aneurysm, ACA, MCA, and VABA; patients at high risk for aneurysm rupture should be carefully monitored.

Systematic Review Registration:

Our study was registered in the INPLASY platform (INPLASY202360062).

1 Introduction

Unruptured intracranial aneurysm (UIA) was considered a “ticking time bomb” and always diagnosed at routine checkups, with an estimated prevalence of 2.3% to 3.2% in the general population (1, 2). The rupture of an intracranial aneurysm can cause aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH), with an annual incidence of nearly 9 per 100,000 cases of UIA and 1.4% of UIA rupture annually (3–5). Considering that aSAH is a serious complication of UIA, and the mortality rate has reached 67%, with nearly 50% of the survivors remaining disabled, clinicians should elucidate the risk of rupture (6). Although UIA can be prophylactically treated to prevent aneurysm rupture, nearly 5% of patients are at risk of complications (7). Therefore, in the management of UIAs, the risk of rupture should be balanced with the risk of UIA.

The 5 years risk of aneurysm rupture in UIA can be evaluated using the PHASES scores, which are based on geographic location, hypertension, age, a history of aSAH, and the aneurysm size and location (5). However, the analysis of risk factors based on PHASES scores was restricted because the analysis relies on published articles. Numerous patient and aneurysm characteristics are associated with the rupture risk or are hypothesized to predispose patients to rupture (8). Follow-up imaging could be used to monitor UIA growth, and preventive aneurysm treatment should be administered when aneurysmal growth is observed (7). Several studies have addressed the predictors of aneurysm rupture in patients with UIA; however, these studies only focused on a single factor (5, 9–11). Additional risk factors should be identified to further prevent the aneurysm rupture risk.

In this study, we aimed to identify the risk factors for aneurysm rupture in patients with UIA by conducting a systemic review and meta-analysis.

2 Methods

2.1 Literature search and selection criteria

This study was conducted and reported following the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology protocol (12), which indicates that the predictors of aneurysm rupture in patients with UIA were eligible for our study, and no restrictions were placed on the publication language and status. Our study was registered in the INPLASY platform (INPLASY202360062). We systematically searched the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases for potentially eligible studies through June 2023 using the following search terms: [intracranial aneurysm(s) OR cerebral aneurysm(s)] AND (risk of rupture OR aneurysm rupture OR risk factors OR rupture OR unruptured OR subarachnoid hemorrhage) AND (follow-up OR natural history OR natural course). Reference lists of relevant reviews and original articles were manually searched to identify eligible studies that met the inclusion criteria.

Two reviewers independently performed the literature search and study selection. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by a group discussion until a consensus was reached. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Patients: all of the patients diagnosed with UIA.

-

Exposure: the predictors for aneurysm rupture reported ≥3 times.

-

Outcomes: the study should report the effect estimate for the risk of aneurysm rupture or data could transform into effect estimate.

-

Study design: no restriction for study design, including prospective and retrospective studies.

2.2 Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers performed data collection and quality assessment including the first author’s surname, publication year, region, study design, sample size, mean age, male proportion, disease status, a family history of aSAH, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), smoking, location of UIA, follow-up, and the number of aneurysm ruptures. The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS), which was partially validated to assess the quality of observational studies in the meta-analysis (13). The NOS contained selection (four items), comparability (one item), and outcome (three items), and the “star system” for each study ranged from 0 to 9. Inconsistent results between the reviewers were resolved by an additional reviewer by referring to the original article.

2.3 Statistical analysis

The risk factors for aneurysm rupture in each study were assigned odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and pooled analysis was performed using the random-effects model considering the underlying variations among the included studies (14, 15). Heterogeneity among the included studies was assessed using I2 and Cochran Q statistics, and significant heterogeneity was defined as I2 ≥ 50.0% or a p-value of <0.10 (16, 17). The robustness of the pooled conclusions was assessed using sensitivity analysis through the sequential removal of a single study (18). Subgroup analyses were performed according to region, study design, follow-up, and study quality, and the differences between subgroups were compared using the interaction P test (19). Funnel plots and Egger–Begg test results were used to assess publication bias (20, 21). The inspection level for pooled effect estimates was two-sided, and a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The STATA software (version 12.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, United States) was used for all statistical analyses.

3 Results

3.1 Literature search

We initially identified 3,742 articles from the electronic searches, and 2,415 articles were retained after duplicates were removed. Subsequently, 2,279 studies were excluded owing to irrelevant titles or abstracts. Five additional articles were identified by reviewing the reference lists of the relevant reviews and original articles. A total of 141 studies were retrieved for detailed evaluation, and 123 studies were excluded because of insufficient data (n = 51), case reports (n = 42), or intervention studies (n = 30). The remaining 18 studies were included in the final meta-analysis (Figure 1) (22–39).

Figure 1

Literature search and study selection.

3.2 Characteristics of the included studies

The baseline characteristics of the identified studies and patients with UIA are summarized in Table 1. In total, 17,069 patients with UIA were included, and the sample sizes ranged from 70 to 5,720. Eight studies were designed as prospective cohorts, and the remaining eight were designed as retrospective cohorts. Nine studies were conducted in Western countries, eight were performed in Eastern countries, and the remaining one was conducted in multiple countries. These studies reported 2,699 aneurysm ruptures. The methodological quality of the individual studies was assessed using the NOS as follows: six studies with eight stars, seven studies with seven stars, and five studies with six stars. Studies with 7–9 stars were regarded as high quality, while 4–6 stars were considered moderate quality.

Table 1

| Study | Region | Study design | Sample size | Age (years) | Male (%) | No. of UIA | Family history of aSAH | Hypertension (%) | DM (%) | Smoking (%) | Location of UIA | Follow-up | No. of aneurysm rupture | NOS scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ishibashi et al. (22) | Japan | Pro | 419 | 60.8 | 33.0 | 529 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ICA (41%), ACA (20%), MCA (27%), VABA (12%) | 2.5 years | 19 | 8 |

| Sonobe et al. (23) | Japan | Pro | 374 | 61.9 | 36.4 | 448 | 8.3 | 24.9 | 6.1 | NA | ICA (38.6%), MCA (35.3%), Acom (13.4%), distal ACA (2.7%), BA (7.4%), VA (0.9%) | 3.5 years | 18 | 8 |

| Morita et al. (24) | Japan | Pro | 5,720 | 62.5 | 33.5 | 6,697 | 12.9 | 43.4 | 6.3 | NA | MCA (36.2%), Acom (15.5%), ICA (18.6%), ICPcom (15.5%), BA (6.6%), VA (1.8%) | 1.7 years | 111 | 8 |

| Guresir et al. (25) | Germany | Pro | 263 | 55.0 | 22.4 | 384 | 3.0 | 42.6 | 5.3 | 52.1 | ACA (46%), MCA (33%), Acom (14%), distal ACA (7%) | 4.0 years | 3 | 7 |

| Juvela et al. (26) | Finland | Pro | 142 | 41.8 | 46.0 | 181 | NA | 36.0 | NA | 47.0 | ICA (42%), ACA (4%), Acom (6%), MCA (45%), VABA (3%) | 21.0 years | 34 | 7 |

| Korja et al. (27) | Finland | Pro | 118 | 43.5 | 48.3 | 146 | NA | 25.0 | NA | 39.0 | NA | 13.6 years | 38 | 7 |

| Gross et al. (28) | United States | Retro | 747 | 53.9 | 17.0 | 1,013 | NA | 39.0 | NA | 32.0 | Acom (17%), MCA (16%), VA (5%), BA (8%), ICA (6%) | 7.0 years | 303 | 6 |

| Hishikawa et al. (29) | Japan | Pro | 1,896 | 74.3 | 27.1 | 2,227 | 9.3 | 53.6 | NA | 8.1 | MCA (33.9%), Acom (17.9%), ICA (11.6%), ICPcom (19.9%), BA (8.7%), VA (2.6%) | 2.2 years | 68 | 7 |

| Murayama et al. (30) | Japan | Pro | 2,252 | 65.0 | 32.4 | 2,897 | NA | 46.5 | 5.7 | 13.5 | MCA (27.3%), ACA (16.8%), ICA (26.8%), ICPcom (20.5%), VABA (8.6%) | 2.6 years | 56 | 8 |

| Teo et al. (31) | United Kingdom | Retro | 94 | 53.0 | 21.3 | 152 | NA | NA | NA | NA | MCA (38%), ICA (21%), Pcom (16%), Acom (9%), BA (7%) | 3.4 years | 4 | 6 |

| Mocco et al. (32) | United States | Pro | 255 | NA | 23.9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ICA (25.5%), ACA/Acom (5.9%), MCA (14.9%), BA (18.0%), Pcom (26.3%), PCA (2.4%) | 7.0 years | 57 | 7 |

| Hostettler et al. (33) | United Kingdom | Retro | 2,334 | 54.2 | 29.7 | 2,942 | 12.4 | 35.3 | 4.6 | 42.5 | MCA (22.9%), ICA (12.8%), ACA/Acom (24.5%), Pcom (18.1%), PCA (11.4%) | 4.0 years | 1,729 | 8 |

| Funakoshi et al. (34) | Japan | Retro | 595 | 63.9 | 27.1 | 595 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ICA (58.2%), MCA (1.7%), Acom (20.7%), VA (3.9%), BA (11.9%) | 6.2 years | 169 | 6 |

| Wang et al. (35) | China | Pro | 1,087 | 60.3 | 53.3 | 1,087 | NA | 53.4 | 19.9 | 21.4 | ICA (65.6%), MCA (8.5%), ACA (3.1%), Acom (7.2%), Pcom (4.0%), BA (4.3%), VA (3.3%), PCA (2.1%) | 2.8 years | 11 | 8 |

| van der Kamp et al. (36) | Canada, Europe, China, and Japan | Retro | 312 | 61.0 | 29.0 | 329 | NA | NA | NA | 41.0 | ICA (25%), MCA (32%), Pcom (8%), Acom (15%), ACA (5%), BA (8%), VABA (7%) | 2.8 years | 24 | 7 |

| Lee et al. (37) | Korea | Retro | 117 | 52.8 | 57.3 | 117 | 4.3 | 42.7 | 11.1 | 28.2 | VA (100%) | 3.0 years | 34 | 6 |

| Dmytriw et al. (38) | Canada | Retro | 70 | 51.7 | 55.7 | 78 | NA | 54.2 | 10.9 | 30.9 | VA (38.5%), BA (30.8%), PCA (19.2%), PICA (10.3%), AICA (1.3%) | 3.0 years | 6 | 6 |

| Spencer et al. (39) | UK | Retro | 274 | 54.8 | 24.1 | 445 | 17.2 | 45.3 | 7.3 | 55.1 | MCA (74.5%), ICA (24.8%), Acom (17.5%), Pcom (13.1%), ACA (5.8%), BA (5.8%), PCA (2.6%) | 3.8 years | 15 | 7 |

Baseline characteristics of included studies and involved patients.

ACA, anterior cerebral artery; Acom, anterior communicating artery; BA, basilar artery; DM, diabetes mellitus; ICA, internal carotid artery; ICPcom, internal carotid-posterior communicating artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; NA, not available; PCA, posterior cerebral artery; Pro, prospective; Retro, retrospective; UIA, unruptured intracranial aneurysm; VA, vertebral artery; VABA, vertebrobasilar artery.

3.3 Age and sex

A total of 11 and 14 studies reported the roles of age and sex on the risk of aneurysm rupture in UIA patients, respectively (Figure 2). Age (OR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.74–1.54; p = 0.740) and sex (OR: 1.08; 95% CI: 0.91–1.30; p = 0.382) were not associated with the aneurysm rupture risk in patients with UIA. There was significant heterogeneity in age (I2 = 70.1%; p < 0.001); in contrast, no significant heterogeneity was observed in sex (I2 = 28.1%; p = 0.154). Sensitivity analyses indicated that the pooled conclusions regarding the roles of age and sex were not changed by the sequential removal of individual studies (Supplementary File 1). Subgroup analyses indicated that younger patients had a reduced risk of aneurysm rupture compared to older patients if the follow-up duration was <3.0 years and the role of age in the risk of aneurysm rupture could be affected by region (p = 0.002) and follow-up (p < 0.001) (Table 2). No evidence of publication bias for age was observed (p-value for Egger: 0.622; p-value for Begg: 0.350; Supplementary File 2). Although the Begg test indicated no significant publication bias for sex (p = 0.324), a potentially significant publication bias was observed using the Egger test (p = 0.035) (Supplementary File 2).

Figure 2

Effect of age and sex on the risk of aneurysm rupture in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIA). (A) Younger vs. elder. (B) Female vs. male.

Table 2

| Outcomes | Factors | Subgroups | No. of studies | OR and 95% CI | p value | I 2 (%) | Q statistic | Interaction p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (younger vs. elder) | Region | Eastern | 5 | 0.74 (0.50–1.09) | 0.128 | 41.2 | 0.147 | 0.002 |

| Western | 6 | 1.47 (0.84–2.56) | 0.173 | 70.1 | 0.005 | |||

| Study design | Prospective | 9 | 0.94 (0.65–1.35) | 0.727 | 65.5 | 0.003 | 0.057 | |

| Retrospective | 2 | 1.81 (0.38–8.61) | 0.454 | 84.9 | 0.010 | |||

| Follow-up (years) | ≥3.0 | 6 | 1.82 (0.99–3.37) | 0.056 | 70.8 | 0.004 | <0.001 | |

| <3.0 | 5 | 0.71 (0.55–0.92) | 0.010 | 0.0 | 0.568 | |||

| Study quality | High | 11 | 1.06 (0.74–1.54) | 0.740 | 70.1 | <0.001 | — | |

| Moderate | 0 | — | — | — | — | |||

| Gender (female vs. male) | Region | Eastern | 7 | 1.11 (0.81–1.52) | 0.501 | 50.0 | 0.062 | 0.653 |

| Western | 7 | 1.04 (0.88–1.23) | 0.647 | 0.0 | 0.438 | |||

| Study design | Prospective | 8 | 1.31 (1.03–1.66) | 0.026 | 0.0 | 0.511 | 0.012 | |

| Retrospective | 6 | 0.92 (0.77–1.09) | 0.321 | 10.4 | 0.349 | |||

| Follow-up (years) | ≥3.0 | 9 | 0.98 (0.79–1.20) | 0.821 | 27.9 | 0.197 | 0.016 | |

| <3.0 | 5 | 1.39 (1.05–1.86) | 0.024 | 0.0 | 0.883 | |||

| Study quality | High | 11 | 1.12 (0.97–1.30) | 0.128 | 0.0 | 0.494 | 0.011 | |

| Moderate | 3 | 0.80 (0.60–1.06) | 0.119 | 9.6 | 0.331 | |||

| Current smoker | Region | Eastern | 5 | 1.01 (0.52–1.95) | 0.988 | 59.1 | 0.044 | 0.273 |

| Western | 7 | 1.40 (1.13–1.72) | 0.002 | 2.9 | 0.404 | |||

| Study design | Prospective | 6 | 1.33 (0.63–2.83) | 0.456 | 67.5 | 0.009 | 0.948 | |

| Retrospective | 6 | 1.31 (1.11–1.56) | 0.002 | 0.0 | 0.883 | |||

| Follow-up (years) | ≥3.0 | 8 | 1.49 (1.04–2.15) | 0.031 | 36.3 | 0.139 | 0.226 | |

| <3.0 | 4 | 1.06 (0.58–1.91) | 0.858 | 36.1 | 0.195 | |||

| Study quality | High | 9 | 1.30 (0.87–1.94) | 0.193 | 52.3 | 0.033 | 0.679 | |

| Moderate | 3 | 1.46 (0.87–2.47) | 0.153 | 0.0 | 0.898 | |||

| Hypertension | Region | Eastern | 6 | 1.44 (0.86–2.41) | 0.167 | 74.3 | 0.002 | 0.393 |

| Western | 6 | 1.53 (0.64–3.67) | 0.343 | 95.8 | <0.001 | |||

| Study design | Prospective | 8 | 1.75 (1.12–2.73) | 0.014 | 79.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Retrospective | 4 | 1.04 (0.49–2.19) | 0.928 | 81.3 | 0.001 | |||

| Follow-up (years) | ≥3.0 | 8 | 1.62 (0.78–3.40) | 0.199 | 94.6 | <0.001 | 0.370 | |

| <3.0 | 4 | 1.31 (0.79–2.16) | 0.292 | 67.1 | 0.028 | |||

| Study quality | High | 10 | 1.66 (0.94–2.93) | 0.079 | 93.5 | <0.001 | 0.338 | |

| Moderate | 2 | 1.00 (0.36–2.77) | 0.994 | 40.9 | 0.193 | |||

| DM | Region | Eastern | 3 | 0.77 (0.27–2.20) | 0.619 | 35.7 | 0.211 | 0.362 |

| Western | 2 | 1.69 (0.18–15.99) | 0.646 | 88.5 | 0.003 | |||

| Study design | Prospective | 2 | 0.33 (0.08–1.37) | 0.128 | 0.0 | 0.760 | 0.230 | |

| Retrospective | 3 | 1.39 (0.48–4.05) | 0.544 | 81.9 | 0.004 | |||

| Follow-up (years) | ≥3.0 | 3 | 1.39 (0.48–4.05) | 0.544 | 81.9 | 0.004 | 0.230 | |

| <3.0 | 2 | 0.33 (0.08–1.37) | 0.128 | 0.0 | 0.760 | |||

| Study quality | High | 3 | 0.57 (0.39–0.85) | 0.005 | 0.0 | 0.703 | 0.003 | |

| Moderate | 2 | 2.49 (0.61–10.24) | 0.205 | 66.8 | 0.082 | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | Region | Eastern | 4 | 0.59 (0.37–0.93) | 0.023 | 0.0 | 0.904 | 0.291 |

| Western | 2 | 0.45 (0.37–0.55) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.712 | |||

| Study design | Prospective | 3 | 0.55 (0.33–0.92) | 0.022 | 0.0 | 0.880 | 0.499 | |

| Retrospective | 3 | 0.46 (0.38–0.56) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.575 | |||

| Follow-up (years) | ≥3.0 | 3 | 0.46 (0.38–0.56) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.575 | 0.499 | |

| <3.0 | 3 | 0.55 (0.33–0.92) | 0.022 | 0.0 | 0.880 | |||

| Study quality | High | 4 | 0.46 (0.38–0.56) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.844 | 0.322 | |

| Moderate | 2 | 0.75 (0.29–1.91) | 0.545 | 0.0 | 0.907 | |||

| History of SAH | Region | Eastern | 4 | 3.17 (1.51–6.66) | 0.002 | 41.6 | 0.162 | 0.005 |

| Western | 3 | 0.90 (0.42–1.92) | 0.778 | 0.0 | 0.613 | |||

| Study design | Prospective | 4 | 3.17 (1.51–6.66) | 0.002 | 41.6 | 0.162 | 0.005 | |

| Retrospective | 3 | 0.90 (0.42–1.92) | 0.778 | 0.0 | 0.613 | |||

| Follow-up (years) | ≥3.0 | 3 | 0.85 (0.34–2.10) | 0.728 | 0.0 | 0.595 | 0.021 | |

| <3.0 | 4 | 2.75 (1.22–6.23) | 0.015 | 59.8 | 0.058 | |||

| Study quality | High | 6 | 2.08 (1.03–4.22) | 0.041 | 57.3 | 0.039 | 0.143 | |

| Moderate | 1 | 0.28 (0.02–4.45) | 0.367 | — | — | |||

| Family history of SAH | Region | Eastern | 3 | 0.91 (0.67–1.24) | 0.545 | 0.0 | 0.654 | 0.418 |

| Western | 1 | 0.79 (0.69–0.90) | 0.001 | — | — | |||

| Study design | Prospective | 3 | 0.91 (0.67–1.24) | 0.545 | 0.0 | 0.654 | 0.418 | |

| Retrospective | 1 | 0.79 (0.69–0.90) | 0.001 | — | — | |||

| Follow-up (years) | ≥3.0 | 2 | 0.83 (0.70–0.98) | 0.028 | 21.4 | 0.259 | 0.629 | |

| <3.0 | 2 | 0.69 (0.35–1.35) | 0.273 | 0.0 | 0.983 | |||

| Study quality | High | 4 | 0.81 (0.71–0.91) | 0.001 | 0.0 | 0.681 | — | |

| Moderate | 0 | — | — | — | — | |||

| Large size of aneurysm | Region | Eastern | 6 | 7.99 (5.00–12.76) | <0.001 | 74.2 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Western | 6 | 2.32 (1.19–4.52) | 0.013 | 77.3 | 0.001 | |||

| Study design | Prospective | 9 | 4.99 (2.41–10.34) | <0.001 | 93.5 | <0.001 | 0.498 | |

| Retrospective | 3 | 3.53 (2.13–5.86) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.695 | |||

| Follow-up (years) | ≥3.0 | 6 | 2.51 (1.21–5.19) | 0.013 | 78.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| <3.0 | 6 | 7.27 (4.45–11.85) | <0.001 | 78.5 | <0.001 | |||

| Study quality | High | 11 | 4.69 (2.53–8.68) | <0.001 | 92.0 | <0.001 | 0.407 | |

| Moderate | 1 | 1.62 (0.17–15.18) | 0.673 | — | — | |||

| Multiple aneurysm | Region | Eastern | 4 | 1.51 (0.99–2.30) | 0.056 | 37.7 | 0.186 | 0.041 |

| Western | 3 | 0.97 (0.79–1.19) | 0.755 | 0.0 | 0.414 | |||

| Study design | Prospective | 5 | 1.39 (0.93–2.06) | 0.107 | 35.8 | 0.183 | 0.084 | |

| Retrospective | 2 | 1.16 (0.54–2.46) | 0.703 | 35.9 | 0.212 | |||

| Follow-up (years) | ≥3.0 | 4 | 1.33 (0.73–2.41) | 0.354 | 60.4 | 0.055 | 0.303 | |

| <3.0 | 3 | 1.28 (0.89–1.85) | 0.186 | 5.9 | 0.345 | |||

| Study quality | High | 6 | 1.23 (0.89–1.69) | 0.214 | 47.6 | 0.089 | 0.267 | |

| Moderate | 1 | 2.55 (0.56–11.64) | 0.227 | — | — | |||

| ACA vs. ICA | Region | Eastern | 6 | 2.46 (1.58–3.84) | <0.001 | 22.2 | 0.267 | <0.001 |

| Western | 3 | 5.35 (3.04–9.43) | <0.001 | 41.3 | 0.182 | |||

| Study design | Prospective | 6 | 3.30 (1.91–5.70) | <0.001 | 13.7 | 0.327 | 0.803 | |

| Retrospective | 3 | 3.58 (1.34–9.57) | 0.011 | 92.2 | <0.001 | |||

| Follow-up (years) | ≥3.0 | 5 | 3.95 (1.87–8.33) | <0.001 | 85.0 | <0.001 | 0.676 | |

| <3.0 | 4 | 2.61 (1.18–5.79) | 0.018 | 36.3 | 0.194 | |||

| Study quality | High | 7 | 4.06 (2.33–7.07) | <0.001 | 48.7 | 0.069 | <0.001 | |

| Moderate | 2 | 2.14 (1.64–2.80) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.662 | |||

| MCA vs. ICA | Region | Eastern | 6 | 1.96 (1.28–3.02) | 0.002 | 0.0 | 0.547 | 0.615 |

| Western | 4 | 2.23 (1.73–2.89) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.826 | |||

| Study design | Prospective | 6 | 2.07 (1.32–3.24) | 0.001 | 0.0 | 0.551 | 0.831 | |

| Retrospective | 4 | 2.19 (1.70–2.82) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.770 | |||

| Follow-up (years) | ≥3.0 | 5 | 2.17 (1.70–2.78) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.929 | 0.910 | |

| <3.0 | 5 | 2.10 (1.24–3.53) | 0.005 | 6.7 | 0.368 | |||

| Study quality | High | 8 | 2.14 (1.68–2.72) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.728 | 0.849 | |

| Moderate | 2 | 2.27 (1.27–4.08) | 0.006 | 0.0 | 0.405 | |||

| VABA vs. ICA | Region | Eastern | 6 | 2.20 (1.10–4.40) | 0.025 | 53.5 | 0.044 | 0.332 |

| Western | 1 | 2.43 (1.02–5.78) | 0.045 | — | — | |||

| Study design | Prospective | 6 | 2.91 (1.78–4.75) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.586 | 0.002 | |

| Retrospective | 1 | 1.07 (0.70–1.63) | 0.752 | — | — | |||

| Follow-up (years) | ≥3.0 | 3 | 1.40 (0.78–2.51) | 0.262 | 28.7 | 0.246 | 0.009 | |

| <3.0 | 4 | 3.22 (1.72–6.03) | <0.001 | 5.4 | 0.376 | |||

| Study quality | High | 6 | 2.91 (1.78–4.75) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.586 | 0.002 | |

| Moderate | 1 | 1.07 (0.70–1.63) | 0.752 | — | — |

Subgroup analyses for the risk factors of aneurysm rupture in UIA patients.

3.4 Smoking status and hypertension

Overall, 12 and 12 studies reported the roles of smoking status and hypertension on the risk of aneurysm rupture in UIA patients, respectively (Figure 3). Current smoking (OR: 1.34; 95% CI: 0.99–1.81; p = 0.059) and hypertension (OR: 1.56; 95% CI: 0.94–2.59; p = 0.087) were not associated with the risk of aneurysm rupture. There was no significant heterogeneity for current smoking (I2 = 35.9%; p = 0.103); in contrast, significant heterogeneity was observed for hypertension (I2 = 92.2%; p < 0.001). Sensitivity analyses revealed that current smoking and hypertension were associated with an elevated risk of aneurysm rupture (Supplementary File 1). Subgroup analyses showed current smoking was associated with an increased risk of aneurysm rupture when pooled studies were conducted in Western countries, studies with a retrospective cohort, and a follow-up of ≥3.0 years. Hypertension induced excess risk of aneurysm rupture in pooled prospective cohort studies. Moreover, the role of hypertension in the risk of aneurysm rupture was affected by the study design (p < 0.001) (Table 2). There was no significant publication bias for current smoking (p-value for Egger: 0.840; p-value for Begg: 0.451) or hypertension (p-value for Egger: 0.276; p-value for Begg: 0.451; Supplementary File 2).

Figure 3

Effect of smoking status and hypertension on the risk of aneurysm rupture in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIA). (A) Current smoker. (B) Hypertension.

3.5 Diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia

Overall, 5 and 6 studies reported the roles of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperlipidemia in the risk of aneurysm rupture in patients with UIA, respectively (Figure 4). Notably, DM was not associated with the risk of aneurysm rupture (OR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.42–2.25; p = 0.940); in contrast, hyperlipidemia was associated with a reduced risk of aneurysm rupture (OR: 0.47; 95% CI: 0.39–0.56; p < 0.001). There was significant heterogeneity for DM (I2 = 68.3%; p = 0.013); in contrast, no evidence of heterogeneity was observed for hyperlipidemia (I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.874). Sensitivity analyses indicated that the pooled conclusions for DM and hyperlipidemia were robust after excluding one study (Supplementary File 1). Subgroup analysis indicated that DM was associated with a reduced risk of aneurysm rupture when pooled studies were of high quality, and study quality could affect the role of DM in the risk of aneurysm rupture (p = 0.003). Moreover, hyperlipidemia was associated with a lower risk of aneurysm rupture in most subgroups; in contrast, there was no significant association between hyperlipidemia and the risk of aneurysm rupture if the pooled studies were of moderate quality (Table 2). There was no significant publication bias for DM (p-value for Egger: 0.619; p-value for Begg: 0.806). Although the Begg test indicated no significant publication bias for hyperlipidemia (p = 0.452), the Egger test suggested a potentially significant publication bias for hyperlipidemia (p = 0.016) (Supplementary File 2).

Figure 4

Effect of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperlipidemia on the risk of aneurysm rupture in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIA). (A) DM. (B) Hyperlipidemia.

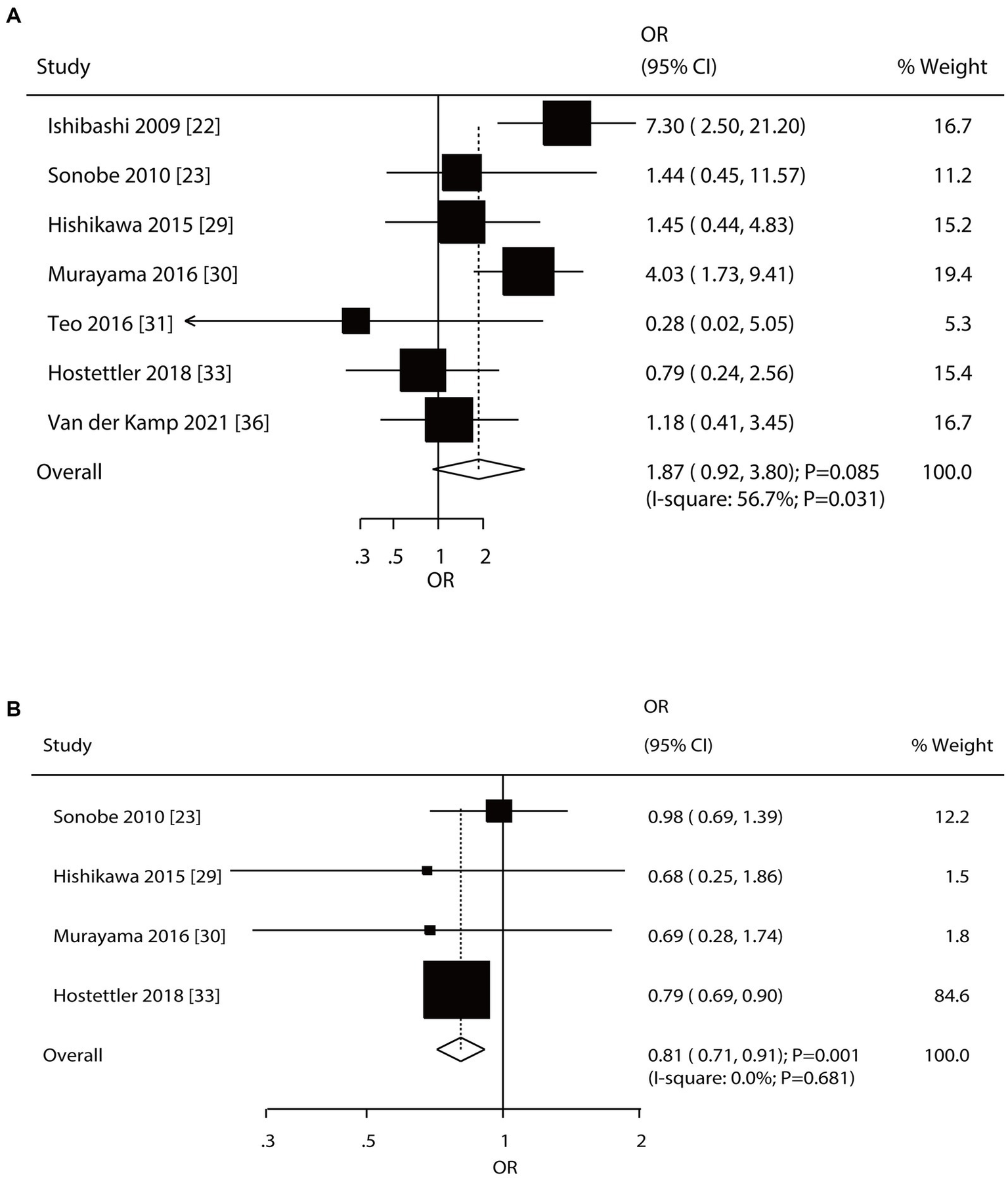

3.6 History of SAH and family history of SAH

Seven and four studies reported the roles of a history of SAH and a family history of SAH on the risk of aneurysm rupture in patients with UIA, respectively (Figure 5). Notably, patients with a history of SAH were not associated with the risk of aneurysm rupture (OR: 1.87; 95% CI: 0.92–3.80; p = 0.085); in contrast, a family history of SAH was associated with a reduced risk of aneurysm rupture (OR: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.71–0.91; p = 0.001). There was significant heterogeneity in the history of SAH (I2 = 56.7%; p = 0.031); in contrast, there was no evidence of heterogeneity in the family history of SAH (I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.681). The pooled conclusions regarding the role of a history of SAH and a family history of SAH on the risk of aneurysm rupture were variable (Supplementary File 1). Subgroup analysis showed that patients with a history of SAH were associated with an increased risk of aneurysm rupture when pooled studies were conducted in Eastern countries, prospective cohort studies, a follow-up of <3.0 years, and high-quality studies, and the association between a history of SAH and aneurysm rupture risk was affected by region (p = 0.005), study design (p = 0.005), and follow-up (p = 0.021). Moreover, a family history of SAH was associated with a reduced risk of aneurysm rupture if pooled studies were conducted in Western countries, retrospective cohort studies, a follow-up of ≥3.0 years, and studies with high quality (Table 2). There was no significant publication bias for a history of SAH (p-value for Egger: 0.161; p-value for Begg: 0.548) or a family history of SAH (p-value for Egger: 0.940; p-value for Begg: 0.734; Supplementary File 2).

Figure 5

Effect of a history of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and a family history of SAH on the risk of aneurysm rupture in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIA). (A) History of SAH. (B) Family history of SAH.

3.7 Aneurysm size and multiple aneurysms

Twelve and seven studies reported the roles of aneurysm size and multiple aneurysms on the risk of aneurysm rupture in patients with UIA, respectively (Figure 6). Large-size aneurysm was associated with an increased risk of aneurysm rupture (OR: 4.49; 95% CI: 2.46–8.17; p < 0.001); in contrast, multiple aneurysms were not associated with the risk of aneurysm rupture (OR: 1.26; 95% CI: 0.92–1.73; p = 0.149). There was significant heterogeneity in aneurysm size (I2 = 91.2%; p < 0.001) and multiple aneurysms (I2 = 44.3%; p = 0.096). The summary results for the role of aneurysm size and multiple aneurysms on the risk of aneurysm rupture were stable and were not altered by removing a single study (Supplementary File 1). Subgroup analyses showed that a large aneurysm size was associated with an increased risk of aneurysm rupture in most subgroups; in contrast, no significant association between a large-size aneurysm and the risk of aneurysm rupture was found in a moderate-quality pooled study. Moreover, the role of a large-size aneurysm in the risk of aneurysm rupture was affected by the region (p < 0.001) and follow-up (p < 0.001). Although the role of multiple aneurysms in the risk of aneurysm rupture was affected by the region (p = 0.041), none of the subgroups showed significant associations between multiple aneurysms and the risk of aneurysm rupture (Table 2). There was no significant publication bias for a large-size aneurysm (p-value for Egger: 0.784; p-value for Begg: 0.451) and multiple aneurysms (p-value for Egger: 0.099; p-value for Begg: 0.548; Supplementary File 2).

Figure 6

Effect of aneurysm size and multiple aneurysms on the risk of aneurysm rupture in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIA). (A) Large size of aneurysm. (B) Multiple aneurysm.

3.8 Aneurysm location

Nine, ten, and eight studies reported the roles of the ACA, MCA, and VABA versus the ICA, respectively, in the risk of aneurysm rupture in patients with UIA (Figure 7). ACA (OR: 3.34; 95% CI: 1.94–5.76; p < 0.001), MCA (OR: 2.16; 95% CI: 1.73–2.69; p < 0.001), and VABA (OR: 2.20; 95% CI: 1.24–3.91; p = 0.007) were associated with an increased risk of aneurysm rupture. There was significant heterogeneity in ACA (I2 = 74.7%; p < 0.001) and VABA (I2 = 49.5%; p = 0.054); in contrast, there was no heterogeneity in the MCA (I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.819). Sensitivity analyses indicated that the pooled conclusions regarding the roles of ACA, MCA, and VABA in the risk of aneurysm rupture were stable (Supplementary File 1). The subgroup analyses indicated that the roles of ACA and MCA in the risk of aneurysm rupture were consistent with the overall analysis of all subgroups. VABA was not associated with the risk of aneurysm rupture when pooled studies were designed as retrospective cohorts, a follow-up of ≥3.0 years, and high-quality studies (Table 2). There was no significant publication bias for ACA (p-value for Egger: 0.811; p-value for Begg: 0.602), MCA (p-value for Egger: 0.845; p-value for Begg: 0.858), or VABA (p-value for Egger: 0.146; p-value for Begg: 0.386; Supplementary File 2).

Figure 7

Effect of aneurysm location on the risk of aneurysm rupture in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIA).

4 Discussion

The predictors of aneurysm rupture in patients with UIA should be further identified to screen patients at high risk of aneurysm rupture. Here, we performed a large quantitative study to identify 17,069 patients with UIA and 2,699 aneurysm ruptures in 18 studies and reviewed the characteristics of studies or patients across a broad range. We determined that large aneurysms, ACA, MCA, and VABA were associated with an increased risk of aneurysm rupture; in contrast, hyperlipidemia and a family history of SAH played a protective role in the risk of aneurysm rupture. Furthermore, age, sex, current smoking status, hypertension, DM, a history of SAH, and multiple aneurysms were not associated with the risk of aneurysm rupture. Finally, the region, study design, follow-up, and study quality could predict the risk of aneurysm rupture in patients with UIA.

Several meta-analyses have investigated potential predictors of aneurysm rupture risk in patients with UIA (5, 9–11). Greving et al. (5) identified six prospective studies and found that the predictors of aneurysm rupture included age, hypertension, a history of SAH, aneurysm size, aneurysm location, and geographic region. Han et al. (9) identified 15 studies and found that wall shear stress, oscillatory shear index, and low shear index could affect the risk of aneurysm rupture in patients. Shu et al. (10) identified four studies reporting machine learning algorithms for rupture risk in patients with UIA and found that the diagnostic value of machine learning algorithms was excellent, with sensitivity and specificity of 84% and 78%, respectively. Guo et al. (11) identified eight studies and found that aspirin plays a protective role against the risk of growth and rupture of aneurysms in patients with UIA. However, these studies did not perform exploratory analyses, and the predictors of aneurysm rupture in patients with UIA should be further explored.

The study indicates that age and sex were not associated with aneurysm rupture risk in patients with UIA. However, subgroup analyses showed that younger age was associated with a lower risk of aneurysm rupture when the follow-up was <3.0 years, inconsistent with the findings of a prior meta-analysis (5). This discrepancy could be explained by variations in the reference age group, which may have affected the estimated effect of age on the risk of aneurysm rupture. Moreover, female patients were associated with an increased risk of aneurysm rupture as compared with male patients when pooled from prospective cohort studies and a follow-up of <3.0 years; this might be due to the higher prevalence of UIA in women compared to men and the accelerated growth rate in women, which was associated with an increased risk of aneurysm rupture (40). Additionally, the risk of aneurysm rupture was not affected by smoking status, hypertension, and DM. Exploratory analysis revealed that current smoking was associated with an increased risk of aneurysm rupture when pooled studies were conducted in Western countries, studies with retrospective cohorts, and a follow-up of ≥3.0 years. This observation could be because smoking is associated with an acute increase in blood pressure for nearly 3 h, and this transient increase might play an important role in the risk of aneurysm rupture (41). Moreover, long-term smoking can change the formation of aneurysms by weakening the vessel walls of cerebral arteries (42). Hypertension was associated with an increased risk of aneurysm rupture in pooled prospective cohort studies, inconsistent with a previous meta-analysis (5), which could be explained by the use of antihypertensive agents, which is associated with a reduced risk of aneurysm rupture (43). Finally, the subgroup analyses showed that DM plays a protective role in the risk of aneurysm rupture when pooled with high-quality studies, which might be affected by hypoglycemic drugs in patients with DM.

This study showed that hyperlipidemia was associated with a reduced risk of aneurysm rupture, which could be explained by the use of statins that reduce the risk of aneurysm rupture through lipid-lowering effects, anti-inflammation of the vasculature, and the ability to stimulate ECM production of extracellular matrix (44–46). Moreover, a history of SAH was not associated with the risk of aneurysm rupture, indicating that aneurysm rupture did not interact with other aneurysms in patients with multiple aneurysms. Notably, we determined that a family history of SAH was associated with a reduced risk of aneurysm rupture, which could be explained by careful monitoring to prevent rupture. Furthermore, the risk of aneurysm rupture can be affected by the size and location of the aneurysm, consistent with prior meta-analyses (5).

This study has some limitations. First, both prospective and retrospective cohort studies were included, and the results may have been affected by selection and recall biases. Second, the reference groups for age and aneurysm size differed across the included studies, which might have affected the estimates for these predictors. Third, the analyses included both crude data and adjusted results, and the adjusted variables might have affected the risk of aneurysm rupture. Fourth, the risk of aneurysm rupture differed according to the location and morphology of aneurysms. Fifth, the heterogeneity among the included studies was not fully explained by sensitivity and subgroup analyses, which could be explained by the different disease statuses of UIA. Finally, there was inevitable publication bias and a restricted detailed meta-analysis of published articles.

This study showed that the predictors of aneurysm rupture in patients with UIA included hyperlipidemia, a family history of SAH, a large-size aneurysm, ACA, MCA, and VABA. However, age, sex, smoking status, hypertension, DM, a history of SAH, and multiple aneurysms did not affect the risk of aneurysm rupture in patients with UIA. The roles of these predictors for the aneurysm rupture risk could be affected by the region, study design, follow-up, and study quality.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

All analyses were based on previous published studies, thus no ethical approval and patient consent are required.

Author contributions

JM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. YZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. PL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. TZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. ZS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. TJ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. AL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2023.1268438/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Vlak MH Algra A Brandenburg R Rinkel GJ . Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms, with emphasis on sex, age, comorbidity, country, and time period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. (2011) 10:626–36. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70109-0

2.

Cras TY Bos D Ikram MA Vergouwen MDI Dippel DWJ Voortman T et al . Determinants of the presence and size of intracranial aneurysms in the general population: the Rotterdam study. Stroke. (2020) 51:2103–10. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029296

3.

van Gijn J Kerr RS Rinkel GJ . Subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet. (2007) 369:306–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60153-6

4.

de Rooij NK Linn FH van der Plas JA Algra A Rinkel GJ . Incidence of subarachnoid haemorrhage: a systematic review with emphasis on region, age, gender and time trends. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2007) 78:1365–72. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.117655

5.

Greving JP Wermer MJ Brown RD Jr Morita A Juvela S Yonekura M et al . Development of the PHASES score for prediction of risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms: a pooled analysis of six prospective cohort studies. Lancet Neurol. (2014) 13:59–66. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70263-1

6.

Nieuwkamp DJ Setz LE Algra A Linn FH de Rooij NK Rinkel GJ . Changes in case fatality of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and region: a meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. (2009) 8:635–42. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70126-7

7.

Algra AM Lindgren A Vergouwen MDI Greving JP van der Schaaf IC van Doormaal TPC et al . Procedural clinical complications, case-fatality risks, and risk factors in endovascular and neurosurgical treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. (2019) 76:282–93. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4165

8.

Hall S Birks J Anderson I Bacon A Brennan PM Bennett D et al . Risk of aneurysm rupture (ROAR) study: protocol for a long-term, longitudinal, UK multicentre study of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. BMJ Open. (2023) 13:e070504. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070504

9.

Han P Jin D Wei W Song C Leng X Liu L et al . The prognostic effects of hemodynamic parameters on rupture of intracranial aneurysm: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. (2021) 86:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.12.012

10.

Shu Z Chen S Wang W Qiu Y Yu Y Lyu N et al . Machine learning algorithms for rupture risk assessment of intracranial aneurysms: a diagnostic meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. (2022) 165:e137–47. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.05.117

11.

Guo Y Guo XM Zhao K Yang MF . Aspirin and growth, rupture of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2021) 209:106949. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.106949

12.

Stroup DF Berlin JA Morton SC Olkin I Williamson GD Rennie D et al . Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. (2000) 283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

13.

Wells G Shea B O’Connell D . The Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (2009) Available at:http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm.

14.

DerSimonian R Laird N . Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials. (2015) 45:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.002

15.

Ades AE Lu G Higgins JP . The interpretation of random-effects meta-analysis in decision models. Med Decis Mak. (2005) 25:646–54. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05282643

16.

Higgins JP Thompson SG Deeks JJ Altman DG . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. (2003) 327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

17.

Deeks J Higgins J Altman D . Analyzing data and undertaking meta-analyses In: HigginsJGreenS, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 5.0.1. Oxford: The Cochrane Collaboration (2008). 243–96.

18.

Tobias A . Assessing the influence of a single study in meta-analysis. Stata Tech Bull. (1999) 47:15–7.

19.

Altman DG Bland JM . Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ. (2003) 326:219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.219

20.

Egger M Davey Smith G Schneider M Minder C . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. (1997) 315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

21.

Begg CB Mazumdar M . Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. (1994) 50:1088–101. doi: 10.2307/2533446

22.

Ishibashi T Murayama Y Urashima M Saguchi T Ebara M Arakawa H et al . Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: incidence of rupture and risk factors. Stroke. (2009) 40:313–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.521674

23.

Sonobe M Yamazaki T Yonekura M Kikuchi H . Small unruptured intracranial aneurysm verification study: SUAVe study, Japan. Stroke. (2010) 41:1969–77. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.585059

24.

Morita A Kirino T Hashi K Aoki N Fukuhara S Hashimoto N et al . The natural course of unruptured cerebral aneurysms in a Japanese cohort. N Engl J Med. (2012) 366:2474–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113260

25.

Guresir E Vatter H Schuss P Platz J Konczalla J de Rochement RM et al . Natural history of small unruptured anterior circulation aneurysms: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. (2013) 44:3027–31. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001107

26.

Juvela S Poussa K Lehto H Porras M . Natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a long-term follow-up study. Stroke. (2013) 44:2414–21. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001838

27.

Korja M Lehto H Juvela S . Lifelong rupture risk of intracranial aneurysms depends on risk factors: a prospective Finnish cohort study. Stroke. (2014) 45:1958–63. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005318

28.

Gross BA Lai PM Du R . Impact of aneurysm location on hemorrhage risk. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2014) 123:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.05.014

29.

Hishikawa T Date I Tokunaga K Tominari S Nozaki K Shiokawa Y et al . Risk of rupture of unruptured cerebral aneurysms in elderly patients. Neurology. (2015) 85:1879–85. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002149

30.

Murayama Y Takao H Ishibashi T Saguchi T Ebara M Yuki I et al . Risk analysis of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: prospective 10 years cohort study. Stroke. (2016) 47:365–71. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010698

31.

Teo M St George EJ . Radiologic surveillance of untreated unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a single surgeon’s experience. World Neurosurg. (2016) 90:20–8. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.02.008

32.

Mocco J Brown RD Jr Torner JC Capuano AW Fargen KM Raghavan ML et al . Aneurysm morphology and prediction of rupture: an international study of unruptured intracranial aneurysms analysis. Neurosurgery. (2018) 82:491–6. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx226

33.

Hostettler IC Alg VS Shahi N Jichi F Bonner S Walsh D et al . Characteristics of unruptured compared to ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a multicenter case-control study. Neurosurgery. (2018) 83:43–52. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx365

34.

Funakoshi Y Imamura H Tani S Adachi H Fukumitsu R Sunohara T et al . Predictors of cerebral aneurysm rupture after coil embolization: single-Center experience with recanalized aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. (2020) 41:828–35. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6558

35.

Wang J Weng J Li H Jiao Y Fu W Huo R et al . Atorvastatin and growth, rupture of small unruptured intracranial aneurysm: results of a prospective cohort study. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. (2021) 14:175628642098793. doi: 10.1177/1756286420987939

36.

van der Kamp LT Rinkel GJE Verbaan D van den Berg R Vandertop WP Murayama Y et al . Risk of rupture after intracranial aneurysm growth. JAMA Neurol. (2021) 78:1228–35. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.2915

37.

Lee HJ Choi JH Lee KS Kim BS Shin YS . Clinical and radiological risk factors for rupture of vertebral artery dissecting aneurysm: significance of the stagnation sign. J Neurosurg. (2021) 137:329–34. doi: 10.3171/2021.9.JNS211848

38.

Dmytriw AA Alrashed A Enriquez-Marulanda A Medhi G Mendes PV . Unruptured intradural posterior circulation dissecting/fusiform aneurysms natural history and treatment outcome. Interv Neuroradiol. (2023) 29:56–62. doi: 10.1177/15910199211068673

39.

Spencer RJ St George EJ . Unruptured untreated intracranial aneurysms: a retrospective analysis of outcomes of 445 aneurysms managed conservatively. Br J Neurosurg. (2023) 37:1643–51. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2023.2207646

40.

Wermer MJ van der Schaaf IC Algra A Rinkel GJ . Risk of rupture of unruptured intracranial aneurysms in relation to patient and aneurysm characteristics: an updated meta-analysis. Stroke. (2007) 38:1404–10. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000260955.51401.cd

41.

Longstreth WT Jr Nelson LM Koepsell TD van Belle G . Cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. (1992) 23:1242–9. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.23.9.1242

42.

Juvela S Porras M Poussa K . Natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: probability of and risk factors for aneurysm rupture. J Neurosurg. (2008) 108:1052–60. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/5/1052

43.

Liu Q Li J Zhang Y Leng X Mossa-Basha M Levitt MR et al . Association of calcium channel blockers with lower incidence of intracranial aneurysm rupture and growth in hypertensive patients. J Neurosurg. (2023) 139:651–60. doi: 10.3171/2022.12.JNS222428

44.

Jiang R Zhao S Wang R Feng H Zhang J Li X et al . Safety and efficacy of atorvastatin for chronic subdural hematoma in Chinese patients: a randomized ClinicalTrial. JAMA Neurol. (2018) 75:1338–46. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2030

45.

Aikawa M Rabkin E Sugiyama S Voglic SJ Fukumoto Y Furukawa Y et al . An HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, cerivastatin, suppresses growth of macrophages expressing matrix metalloproteinases and tissue factor in vivo and in vitro. Circulation. (2001) 103:276–83. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.2.276

46.

Potey C Ouk T Petrault O Petrault M Berezowski V Salleron J et al . Early treatment with atorvastatin exerts parenchymal and vascular protective effects in experimental cerebral ischaemia. Br J Pharmacol. (2015) 172:5188–98. doi: 10.1111/bph.13285

Summary

Keywords

risk factors, rupture, intracranial aneurysms, systematic review, meta-analysis

Citation

Ma J, Zheng Y, Li P, Zhou T, Sun Z, Ju T and Li A (2023) Risk factors for the rupture of intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 14:1268438. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1268438

Received

01 August 2023

Accepted

09 November 2023

Published

11 December 2023

Volume

14 - 2023

Edited by

Paolo Aridon, University of Palermo, Italy

Reviewed by

Qin Fei Yun, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wannan Medical College, China; Paolo Ragonese, University of Palermo, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Ma, Zheng, Li, Zhou, Sun, Ju and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aijun Li, aijunli69@sina.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.