Abstract

Objective:

Inflammation participates in the pathology and progression of secondary brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). This meta-analysis intended to explore the prognostic role of inflammatory indexes, including neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), white blood cell (WBC), and C-reactive protein (CRP) in ICH patients.

Methods:

Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library were searched until June 2023. Two outcomes, including poor outcome and mortality were extracted and measured. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were presented for outcome assessment.

Results:

Forty-six studies with 25,928 patients were included in this meta-analysis. The high level of NLR [OR (95% CI): 1.20 (1.13–1.27), p < 0.001], WBC [OR (95% CI): 1.11 (1.02–1.21), p = 0.013], and CRP [OR (95% CI): 1.29 (1.08–1.54), p = 0.005] were related to poor outcome in ICH patients. Additionally, the high level of NLR [OR (95% CI): 1.06 (1.02–1.10), p = 0.001], WBC [OR (95% CI): 1.39 (1.16–1.66), p < 0.001], and CRP [OR (95% CI): 1.02 (1.01–1.04), p = 0.009] were correlated with increased mortality in ICH patients. Nevertheless, PLR was not associated with poor outcome [OR (95% CI): 1.00 (0.99–1.01), p = 0.749] or mortality [OR (95% CI): 1.00 (0.99–1.01), p = 0.750] in ICH patients. The total score of risk of bias assessed by Newcastle-Ottawa Scale criteria ranged from 7–9, which indicated the low risk of bias in the included studies. Publication bias was low, and stability assessed by sensitivity analysis was good.

Conclusion:

This meta-analysis summarizes that the high level of NLR, WBC, and CRP estimates poor outcome and higher mortality in ICH patients.

1 Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is the second most common type of stroke, which accounts for approximately 27.9% of all incident strokes (1, 2). The global incidence of ICH ranges from 27 to 30 per 100,000 person-years, and the predominant risk factors for ICH include hypertension, coagulopathy, alcohol abuse, diabetes mellitus, smoking, etc. (3–5). Currently, several treatment strategies have been developed to treat ICH patients, such as surgery, blood pressure control, and hemostatic therapy; these therapeutic strategies have made non-negligible progress in treating ICH patients (6–8). Unfortunately, there is no single treatment that effectively improves the prognosis of these patients (9). It is estimated that the mortality after ICH is around 30 to 40% within the first month, and it is approximately 50% within 1 year (10–13). In addition, most patients experience functional decline, and only 12 to 39% of ICH patients achieve long-term functional independence (10, 14, 15). Therefore, identifying potential prognostic factors may be meaningful to enhance the management of ICH patients.

Neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, and CRP play a fundamental role in regulating inflammation after ICH, which would further aggravate brain injury and lead to a poor prognosis (16–23). For instance, neutrophils are the first leukocyte subtype to infiltrate into the brain after ICH, which facilitates brain injury by producing reactive oxygen species and releasing proinflammatory cytokines (19). Regarding lymphocytes, ICH would increase catecholamine and steroids to induce lymphocytopenia, which contributes to immunosuppression and aggravates brain injury (20). Besides, platelets are activated after ICH, then they could interact with macrophages to facilitate the production of proinflammatory cytokines, aggravating the brain injury (21). Moreover, C-reactive protein (CPR) could facilitate the production of inflammatory cytokines and induce blood–brain barrier disruption to aggravate inflammation and brain injury (22, 23). Considering their close engagement in ICH, it might be meaningful to explore the prognostic values of relevant inflammatory indicators, including neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), white blood cell (WBC), and CPR in ICH patients (24–27).

One previous study indicates that the high level of NLR is correlated with poor outcome in ICH patients (27). Meanwhile, another study elucidates that the high level of PLR predicts poor outcome, but it cannot estimate mortality in ICH patients (26). Regarding the high level of WBC, it could forecast increased mortality and poor outcome in ICH patients (25). Furthermore, the high level of CRP is associated with elevated mortality and poor outcomes in ICH patients (24). Notably, one recently published meta-analysis has revealed the prognostic role of NLR for ICH patients, which discovers that NLR is correlated with a poor outcome and mortality in ICH patients (28). However, the most recent articles included in this previous meta-analysis are published in 2021, and some updated relevant studies should be considered (28). On the other hand, the previous meta-analysis mainly focuses on the prognostic effect of NLR for ICH patients (28), and whether other inflammatory markers have the same prognostic implication should be further investigated. Accordingly, this meta-analysis enrolled some up-to-date studies and aimed to explore the predictive role of NLR, PLR, WBC, and CRP for poor outcome and mortality in ICH patients.

2 Methods

2.1 Data sources and searches

Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library were searched until June 2023 using the following keywords or a term of their combination: ‘neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio’, ‘neutrophil lymphocyte ratio’, ‘neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio’, ‘neutrophil/lymphocyte’, ‘neutrophil-lymphocyte’, ‘NLR’, ‘platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio’, ‘platelet lymphocyte ratio’, ‘platelet to lymphocyte ratio’, ‘platelet/lymphocyte’, ‘platelet-lymphocyte’, ‘PLR’, ‘C-reactive protein’, ‘CRP’, ‘inflammation’, ‘WBC’, ‘WCC’, ‘white cell count’, ‘white blood cell’, ‘leukocyte’, ‘ICH’, ‘intracerebral hemorrhage’, ‘intracranial hemorrhage’, ‘cerebral hemorrhage’, and ‘brain hemorrhage’. The PICOS (Participants, Intervention/exposure, Comparison, Outcomes, Study design) criteria were used to structure this meta-analysis (29). (i) Patients (P): patients diagnosed with ICH. (ii) Intervention (I): patients with a high level of NLR, PLR, WBC, and CRP. (iii) Control (C): patients with a low level of NLR, PLR, WBC, and CRP. (iv) Outcomes (O): poor outcome and mortality. (v) Study design: observational studies.

2.2 Outcomes

In this meta-analysis, two outcomes were measured including poor outcome and mortality. Specifically, poor outcome was defined as recording a modified Rankin scale (mRS) score > 2 and/or a Glasgow outcome scale (GOS) score < 4 during the follow-up; and mortality was defined as any cause-death during the follow-up.

2.3 Identification criteria

Studies met the following criteria were included: (i) patients diagnosed with ICH; (ii) patients aged more than 18 years; (iii) studies reported inflammation indexes, which contained NLR, PLR, WBC, and CPR (at least one involved); (iv) studies reported multivariate analysis results for outcomes, which contained odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The exclusion criteria were: (i) meeting abstract, letter to the editor, case report, or animal study; (ii) with the non-accessible full-text article; (iii) studies were not English language published. Studies were identified by two independent reviewers (Guo and Zou) in accordance with the above criteria. Disagreements were solved by a consensus of the above two reviewers.

2.4 Data extraction and quality assessment

Year, first author, country, study design, number and sex ratio, age, sample time, follow-up period, inflammation indexes, and outcomes were extracted from included studies. The quality of included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) (upper limit, 9; ≥6, high-quality) (30). Besides, data extraction and quality assessment were completed by two independent reviewers (Guo and Zou).

2.5 Statistics

The OR with 95% CI related to inflammation indexes and outcomes was calculated. In a meta-analysis, the differences in study design, population, and measurements across different studies were referred to as heterogeneity. For heterogeneity assessment, I2 test and Q test were used. I2 represented the ratio of studies heterogeneity to total variation; while Q followed a χ2 distribution with k-1 degrees of freedom. The range of I2 values varied from 0 to 100%, with higher values indicating greater heterogeneity. I2 > 50.0% and p < 0.05 () were considered as heterogeneity existed, and the random-effect model was used; otherwise, the fixed-effect model was used. Publication bias was shown via Deeks’ funnel plots (Begg’s test). The funnel plots determined the presence or absence of publication bias in meta-analysis based on the degree of asymmetry of the graph. The p value of Begg’s test less than 0.05 indicated publication bias existed. If there was a risk of bias, trim and fill analysis was used for further investigation. Sensitivity analysis was used to assess the robustness and reliability of the results by using the leave-one-out approach. If the results of model remain unchanged after sensitivity analysis, the results were reliable. Stata v.14.0 (Stata Corp, USA) was used, and p < 0.05 indicated significance.

3 Results

3.1 Study screening procedure

A total of 5,081 studies were identified from the electronic base, including 2,182 studies from Embase, 1794 studies from PubMed, 1,019 studies from Web of Science, and 86 studies from Cochrane Library. Then 4,270 duplicate studies were excluded, and the rest 811 studies were screened based on the title and abstract read. After that, 747 studies were further excluded, including 651 studies that were mismatched to inflammation indexes or outcomes, 89 meta-analyses, and 7 case reports or animal studies. Subsequently, 64 studies were screened based on full-text read, and 18 studies were excluded, including 13 studies without multivariate analysis results and 5 meeting abstracts or letters to the editor. Ultimately, 46 studies were included in this meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Study flow.

3.2 Features of included studies

The included studies were published from 2009 to 2023, which contained a total of 25,928 patients (24–27, 31–72). Twenty-five studies were conducted in China, 4 studies were conducted in Italy, 4 studies were conducted in the United States of America (USA), 3 studies were conducted in Germany, 2 studies were conducted in Korea, and the other studies were conducted in Bulgaria, Spain, Finland, Portugal, Romania, Turkey, Tunisia, and India, respectively. The follow-up duration ranged from 30 days to 1 year. The detailed information of the included studies is shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| Study | Country | Design | Number (M/F) | Age | Sample time | Follow-up | Inflammation indexes | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diedler et al. (31) | Germany | Retro | 103 (78/25) | 66.6 ± 11.5 | Admission | 1 year | CRP | 1-year poor outcome (mRS 3–6) |

| Alexandrova and Danovska (32) | Bulgaria | Pro | 46 (23/23) | 63.0 ± 12.0 | Admission | NM | CRP | First-week mortality |

| Di Napoli et al. (33) | Italy | Pro | 210 (122/88) | 67.3 ± 11.5 | Admission | 30 days | WBC; CRP | 30-day mortality |

| Rodríguez-Yáñez et al. (34) | Spain | Retro | 141 (66/75) | 75.9 ± 12.3 | Admission | 90 days | WBC; CRP | 30-day poor outcome (mRS >2) |

| Löppönen et al. (35) | Finland | Pro | 436 (235/201) | 69.0 ± 12.0 | In the emergency department or on next morning | 90 days | CRP | 90-day poor outcome (GOS 1–4) |

| Adeoye et al. (36) | USA | Retro | 186 (94/92) | 67.3 ± 14.8 | Admission | 30 days | WBC | 30-day mortality |

| Walsh et al. (37) | USA | Pro | 240 (148/92) | 62.8 ± 14.0 | Admission | 30 days | WBC | 30-day mortality |

| Yu et al. (38) | Korea | Retro | 2,630 (1,639/991) | 63.7 ± 12.8 | Admission | 90 days | WBC | 90-day poor outcome (mRS 3–6); 90-day mortality |

| Lattanzi et al. (39) | Italy | Retro | 177 (63/114) | 67.1 ± 12.5 | Admission | 90 days | NLR; WBC | 90-day poor outcome (mRS ≥3) |

| Wang et al. (40) | China | Retro | 224 (141/83) | 68.0 ± 13.8 | Admission | 30 days | NLR | 30-day mortality |

| Yan et al. (24) | China | Pro | 112 (66/46) | 63.2 ± 9.6 | Admission | 180 days | CRP | 180-day poor outcome (mRS >2); 180-day mortality |

| Giede Jeppe et al. (41) | Germany | Retro | 855 (457/398) | 72.5 (61.0–80.0) for NLR ≥4.7; 71.0 (62.0–78.0) for NLR <4.7 | Admission | 90 days | NLR | 30-day poor outcome (mRS 4–6); 30-day mortality |

| Tao et al. (25) | China | Retro | 336 (216/120) | 58.5 ± 13.0 | Admission | 90 days | NLR; WBC | 90-day poor outcome (mRS ≥3); 90-day mortality |

| Sun et al. (42) | China | Retro | 352 (234/118) | 64.2 ± 13.8 | Admission | 90 days | NLR | 90-day poor outcome (mRS ≥3); 90-day mortality |

| Bolayir et al. (43) | Turkey | Retro | 296 (138/158) | 76.3 ± 11.4 | Admission | 60 days | CRP | 60-day mortality |

| Elhechmi et al. (44) | Tunisia | Retro | 91 (56/35) | 64.4 (61.5–67.2) | Admission | 30 days | CRP | 30-day mortality |

| Lattanzi et al. (45) | Italy | Retro | 208 (132/76) | 66.7 ± 12.4 | Admission | 30 days | NLR; WBC | 90-day poor outcome (mRS ≥3) |

| Fan et al. (46) | China | Retro | 225 (176/49) | 53.2 ± 10.7 | Admission | 90 days | NLR; PLR; WBC | 90-day poor outcome (GOS <3) |

| Wang et al. (47) | China | Retro | 181 (112/69) | 65.8 ± 14.3 | Admission | 30 days | NLR; CRP | 30-day mortality |

| Qi et al. (48) | China | Retro | 558 (368/190) | 57.6 (28.0–79.0) | Admission | 90 days | NLR; WBC | 90-day mortality |

| Zhang et al. (49) | China | Retro | 104 (80/24) | 50.4 ± 9.9 | Admission | 90 days | NLR | 90-day poor outcome (GOS ≤3) |

| Guo et al. (50) | China | Retro | 171 (94/77) | 46.1 ± 17.3 | Admission | 90 days | NRL | 90-day poor outcome (GOS ≤3) |

| Qin et al. (51) | China | Retro | 213 (157/56) | 50.0 (46.0–55.0) | Admission | 90 days | NLR | 90-day poor outcome (mRS 3–6) |

| Wang et al. (52) | China | Retro | 275 (207/68) | 69.0 (53.0–79.0) for the survived; 71.0 (52.0–82.0) for the died | Admission | 30 days | NLR | 30-day mortality |

| Zhang et al. (53) | China | Retro | 175 (124/51) | 60.1 ± 13.0 | Admission | 30 days | NLR; WBC | 30-day poor outcome (GOS <3) |

| Zhang et al. (54) | China | Retro | 481 (350/131) | 61.1 ± 12.1 | Admission | 180 days | NLR; WBC | 180-day poor outcome (GOS <3); 180-day mortality |

| Zhang et al. (55) | China | Retro | 107 (72/35) | 54.7 ± 12.0 | Admission | 30 days | NLR; WBC | 30-day poor outcome (GOS <3) |

| Chen et al. (56) | China | Retro | 380 (255/125) | 58.7 ± 11.4 | Admission | 30 days | NLR | 30-day mortality |

| Sagar et al. (57) | India | Pro | 250 (162/88) | 54.9 ± 12.8 | Admission | 90 days | CRP | 90-day poor outcome (mRS 4–6) |

| Menon et al. (58) | Italy | Retro | 851 (604/247) | 58.1 ± 12.9 | Admission | 30 days | NLR | 30-day poor outcome (mRS 4–6) |

| Gusdon et al. (59) | USA | Pro | 500 (278/222) | 59.0 (51.0–67.0) | Admission | 180 days | NLR; WBC | 180-day poor outcome (mRS 4–6) |

| Fonseca et al. (26) | Portugal | Retro | 135 (69/66) | 73.0 (64.0–80.0) | Admission | 90 days | NLR; PLR; CRP | 90-day poor outcome (mRS ≥3); 30-day mortality |

| Mackey et al. (60) | USA | Retro | 593 (322/271) | NM | Within 24 h of disease onset | 30 days | NLR; WBC | 30-day mortality |

| Li et al. (61) | China | Retro | 403 (276/127) | 58.6 ± 13.3 | Admission | 90 days | NLR | 90-day poor outcome (mRS ≥3); 30-day mortality |

| Radu et al. (62) | Romania | Retro | 201 (111/90) | 70.0 (61.0–79.0) | Admission | 30 days | NLR; CRP | In-hospital mortality |

| Yang et al. (63) | China | Retro | 431 (299/132) | 58.8 ± 12.9 | Admission | 90 days | NLR | 90-day poor outcome (mRS ≥3); 30-day mortality |

| Bender et al. (64) | Germany | Retro | 329 (177/152) | 67.4 ± 13.6 | Admission | NM | CRP | In-hospital mortality |

| Luo et al. (65) | China | Retro | 329 (210/119) | 61.0 ± 12.6 | Admission | 90 days | NLR | 90-day poor outcome (mRS 4–6) |

| Zhao et al. (27) | China | Retro | 128 (88/40) | 60.0 (50.0–67.0) | Within 48 h after surgery | 90 days | NLR | 30-day poor outcomes (mRS 4–6) |

| Du et al. (66) | China | Pro | 594 (423/171) | 56.0 (49.0–64.0) | Admission | 90 days | NLR | 90-day poor outcome (mRS 3–6); 90-day mortality |

| Wang et al. (67) | China | Retro | 9,589 (6,086/3503) | 62.7 ± 13.3 | Admission | NM | CRP | In-hospital mortality |

| Chu et al. (68) | China | Retro | 455 (332/123) | 62.3 ± 13.4 | Admission | 90 days | WBC | 90-day poor outcome (mRS 4–6); 30-day mortality |

| Zhang et al. (69) | China | Retro | 901 (631/270) | 58.7 ± 14.3 | Admission | 90 days | NLR | 90-day mortality |

| Zhang et al. (70) | China | Retro | 101 (69/32) | 59.0 (53.5–66.0) | Within 48 h after surgery | 30 days | NLR; PLR | 30-day poor outcomes (mRS ≥3) |

| Shi et al. (71) | China | Retro | 105 (69/36) | 52.6 ± 13.9 | Admission | 30 days | NLR; WBC; CRP | 30-day mortality |

| Kim et al. (72) | Korea | Pro | 520 (312/208) | 64.2 ± 15.7 | Admission | 90 days | NLR; PLR | 90-day poor outcome (mRS 3–6); 30-day mortality |

Included studies.

M/F, male/female; Retro, Retrospective; CRP, C-reactive protein; mRS, modified Rankin scale; Pro, prospective; NM. Not mentioned; WBC, white blood cell count; GOS, Glasgow outcomes scale; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio. The age was described as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range).

3.3 NLR for predicting poor outcome and mortality

A total of 22 studies reported NLR for predicting poor outcome, and heterogeneity existed among these studies (I2 = 84.1%, p < 0.001). The pooled analysis disclosed that the high level of NLR was related to poor outcome in ICH patients [OR (95% CI): 1.20 (1.13–1.27), p < 0.001] (Figure 2A). In terms of mortality, 18 studies reported the association of NLR with mortality, and heterogeneity existed among these studies (I2 = 80.0%, p < 0.001). The pooled analysis suggested that the high level of NLR was linked with increased mortality in ICH patients [OR (95% CI): 1.06 (1.02–1.10), p = 0.001] (Figure 2B). Two studies clearly indicated that they excluded aneurysmal cerebral hemorrhage patients. Thus, a subgroup analysis was carried out based on these 2 studies. It was found that no heterogeneity existed between these 2 studies (I2 = 67.6%, p = 0.079). The pooled analysis discovered that the high level of NLR showed a trend to correlate with increased mortality in ICH patients, but it did not achieve statistical significance [OR (95% CI): 1.11 (0.99, 1.23), p = 0.065] (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 2

Forest plot of NLR for predicting poor outcome and mortality in ICH patients. Correlation of NLR with poor outcome (A) and mortality (B) in ICH patients.

3.4 PLR for predicting poor outcome and mortality

There were 4 studies that reported PLR for predicting poor outcome. Heterogeneity existed among these studies (I2 = 77.3%, p = 0.004). According to the pooled analysis, PLR was not associated with poor outcome in ICH patients [OR (95% CI): 1.00 (0.99, 1.01), p = 0.749] (Figure 3A). In addition, 2 studies reported PLR for predicting mortality, and there was no heterogeneity existed among these studies (I2 = 55.7%, p = 0.133). Notably, the pooled analysis showed that PLR was also not correlated with mortality in ICH patients [OR (95% CI): 1.00 (0.99, 1.01), p = 0.750] (Figure 3B).

Figure 3

Forest plot of PLR for predicting poor outcome and mortality in ICH patients. Association of PLR with poor outcome (A) and mortality (B) in ICH patients.

3.5 WBC for predicting poor outcome and mortality

WBC for estimating poor outcome was reported in 11 studies, and heterogeneity existed among these studies (I2 = 76.4%, p < 0.001). The pooled analysis exhibited that the high level of WBC was linked with poor outcome in ICH patients [OR (95% CI): 1.11 (1.02, 1.21), p = 0.013] (Figure 4A). Regarding WBC for predicting mortality, 10 studies reported that. Heterogeneity existed among these studies (I2 = 82.5%, p < 0.001). After conducting the pooled analysis, it was discovered that the high level of WBC was linked to increased mortality in ICH patients [OR (95% CI): 1.39 (1.16, 1.66), p < 0.001] (Figure 4B).

Figure 4

Forest plot of WBC for predicting poor outcome and mortality in ICH patients. Relationship of WBC with poor outcome (A) and mortality (B) in ICH patients.

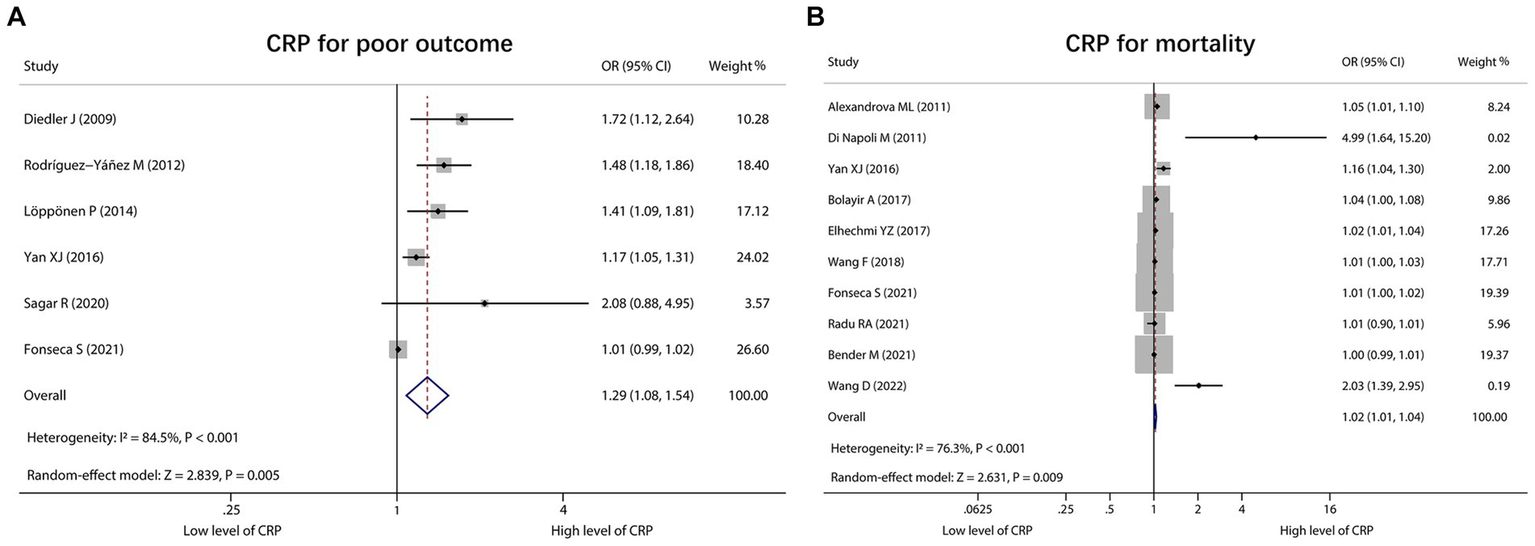

3.6 CRP for predicting poor outcome and mortality

A total of 6 studies reported CRP for predicting poor outcome, and heterogeneity existed among these studies (I2 = 84.5%, p < 0.001). The pooled analysis indicated that the high level of CRP was correlated with poor outcome in ICH patients [OR (95% CI): 1.29 (1.08, 1.54), p = 0.005] (Figure 5A). Moreover, 10 studies reported CRP for forecasting mortality. Heterogeneity existed among these studies (I2 = 76.3%, p < 0.001). The pooled analysis disclosed that CRP was associated with raised mortality in ICH patients [OR (95% CI): 1.02 (1.01, 1.04), p = 0.009] (Figure 5B).

Figure 5

Forest plot of CRP for predicting poor outcome and mortality in ICH patients. Relationship of CRP with poor outcome (A) and mortality (B) in ICH patients.

3.7 Sensitivity analysis and quality assessment

Sensitivity analysis disclosed that omitting Fonseca would affect the result of PLR for estimating mortality. Apart from that, omitting any of a single study would not influence the results of the pooled analysis, which indicated the stability of this meta-analysis (Supplementary Table S1).

The included studies were evaluated by the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale criteria, and the total score of bias risk of each study ranged from 7–9, which indicated the low risk of bias in the included studies (Table 2).

Table 2

| Included studies | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diedler et al. (31) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Alexandrova and Danovska (32) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Di Napoli et al. (33) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Rodríguez-Yáñez et al. (34) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Löppönen et al. (35) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Adeoye et al. (36) | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Walsh et al. (37) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Yu et al. (38) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Lattanzi et al. (39) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Wang et al. (40) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Yan et al. (24) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Giede Jeppe et al. (41) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Tao et al. (25) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Sun et al. (42) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Bolayir et al. (43) | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Elhechmi et al. (44) | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Lattanzi et al. (45) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Fan et al. (46) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Wang et al. (47) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Qi et al. (48) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Zhang et al. (49) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Guo et al. (50) | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Qin et al. (51) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Wang et al. (52) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Zhang et al. (53) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Zhang et al. (54) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Zhang et al. (55) | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Chen et al. (56) | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Sagar et al. (57) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Menon et al. (58) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Gusdon et al. (59) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Fonseca et al. (26) | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Mackey et al. (60) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Li et al. (61) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Radu et al. (62) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Yang et al. (63) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Bender et al. (64) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Luo et al. (65) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Zhao et al. (27) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Du et al. (66) | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Wang et al. (67) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Chu et al. (68) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Zhang et al. (69) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Zhang et al. (70) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Shi et al. (71) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Kim et al. (72) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

Quality assessment by Newcastle-Ottawa Scale criteria.

3.8 Subgroup analysis for poor outcome based on study type and follow-up duration

The pooled analysis suggested that the high level of NLR was related to poor outcome in retrospective studies [OR (95% CI): 1.22 (1.14, 1.31), p < 0.001], studies with a follow-up duration of <90 days [OR (95% CI): 1.23 (1.08, 1.40), p = 0.002], and studies with a follow-up duration of ≥90 days [OR (95% CI): 1.20 (1.11, 1.29), p < 0.001]. Heterogeneity existed among these studies that reported NLR for predicting poor outcome (all I2 > 50.0%, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3

| Subgroup | Number of studies | I 2 | p-value of heterogeneity | Effect model | OR (95% CI) | Z | P-value of statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLR | |||||||

| Total | 22 | 84.1% | <0.001 | Random | 1.20 (1.13–1.27) | 5.850 | <0.001 |

| Design | |||||||

| Retrospective | 18 | 85.8% | <0.001 | Random | 1.22 (1.14–1.31) | 5.819 | <0.001 |

| Prospective | 4 | 72.7% | 0.012 | Random | 1.10 (0.93–1.29) | 1.118 | 0.264 |

| Follow-up | |||||||

| <90 days | 6 | 88.2% | <0.001 | Random | 1.23 (1.08–1.40) | 3.040 | 0.002 |

| ≥90 days | 16 | 83.0% | <0.001 | Random | 1.20 (1.11–1.29) | 4.823 | <0.001 |

| PLR | |||||||

| Total | 4 | 77.3% | <0.001 | Random | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.319 | 0.749 |

| Design | |||||||

| Retrospective | 3 | 82.3% | 0.001 | Random | 1.00 (1.00–1.02) | 0.576 | 0.565 |

| Prospective | 1 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Follow-up | |||||||

| <90 days | 1 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| ≥90 days | 3 | 70.2% | <0.001 | Random | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.460 | 0.646 |

| WBC | |||||||

| Total | 11 | 76.4% | <0.001 | Random | 1.11 (1.02–1.21) | 2.473 | 0.013 |

| Design | |||||||

| Retrospective | 10 | 77.6% | <0.001 | Random | 1.13 (1.02–1.25) | 2.258 | 0.018 |

| Prospective | 1 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Follow-up | |||||||

| <90 days | 3 | 0.0% | 0.418 | Fixed | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | 1.599 | 0.110 |

| ≥90 days | 8 | 82.5% | <0.001 | Random | 1.15 (1.02–1.30) | 2.300 | 0.021 |

| CRP | |||||||

| Total | 6 | 84.5 | <0.001 | Random | 1.29 (1.08–1.54) | 2.839 | 0.005 |

| Design | |||||||

| Retrospective | 3 | 88.0% | <0.001 | Random | 1.32 (0.93–1.86) | 1.553 | 0.120 |

| Prospective | 3 | 36.8% | 0.205 | Fixed | 1.22 (1.10–1.35) | 3.801 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up | |||||||

| <90 days | 1 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| ≥90 days | 5 | 81.6% | <0.001 | Random | 1.23 (1.03–1.47) | 2.338 | 0.019 |

Subgroup analysis of the association of inflammation indexes with poor outcome.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; WBC, white blood cell count; CRP, C-reactive protein.

No correlation was found between PLR and poor outcome in retrospective studies and studies with a follow-up duration of ≥90 days (both p > 0.05) (Table 3).

The pooled analysis disclosed that the high level of WBC was correlated with poor outcome in retrospective studies [OR (95% CI): 1.13 (1.02, 1.25), p = 0.018] and studies with a follow-up duration of ≥90 days [OR (95% CI): 1.15 (1.02, 1.30), p = 0.021]. Heterogeneity existed among these studies that reported WBC for estimating poor outcome (both I2 > 50.0%, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

The pooled analysis displayed that the high level of CRP was associated with poor outcome in prospective studies [OR (95% CI): 1.22 (1.10, 1.35), p < 0.001] without heterogeneity among these studies (I2 = 36.8%, p = 0.205). In studies with a follow-up duration of ≥90 days, the high level of CRP was associated with poor outcome [OR (95% CI): 1.23 (1.03, 1.47), p = 0.019] with heterogeneity among these studies (I2 = 81.6%, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

3.9 Subgroup analysis for mortality based on study type and follow-up duration

The pooled analysis revealed that the high level of NLR was related to increased mortality in retrospective studies [OR (95% CI): 1.05 (1.02, 1.09), p = 0.007], prospective studies [OR (95% CI): 1.16 (1.08, 1.24), p < 0.001], studies with a follow-up duration of <90 days [OR (95% CI): 1.05 (1.01, 1.10), p = 0.021], and studies with a follow-up duration of≥90 days [OR (95% CI): 1.15 (1.03, 1.28), p = 0.012]. In terms of NLR for predicting mortality, heterogeneity existed among retrospective studies, studies with a follow-up duration of <90 days, and studies with a follow-up duration of≥90 days (all I2 > 50.0%, p < 0.001); heterogeneity did not exist in prospective studies (I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.651) (Table 4).

Table 4

| Subgroup | Number of studies | I 2 | P-value of heterogeneity | Effect model | OR (95% CI) | Z | P-value of statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLR | |||||||

| Total | 18 | 80.0% | <0.001 | Random | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | 3.186 | <0.001 |

| Design | |||||||

| Retrospective | 16 | 79.9% | <0.001 | Random | 1.05 (1.02–1.09) | 2.716 | 0.007 |

| Prospective | 2 | 0.0% | 0.651 | Fixed | 1.16 (1.08–1.24) | 4.187 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up | |||||||

| <90 days | 12 | 77.2% | <0.001 | Random | 1.05 (1.01–1.10) | 2.307 | 0.021 |

| ≥90 days | 6 | 84.7% | <0.001 | Random | 1.15 (1.03–1.28) | 2.512 | 0.012 |

| PLR | |||||||

| Total | 2 | 55.7% | 0.133 | Random | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.319 | 0.750 |

| Design | |||||||

| Retrospective | 1 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Prospective | 1 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Follow-up | |||||||

| <90 days | 2 | 55.7% | 0.133 | Random | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.319 | 0.750 |

| ≥90 days | 0 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| WBC | |||||||

| Total | 10 | 82.5% | <0.001 | Random | 1.39 (1.16–1.66) | ||

| Design | |||||||

| Retrospective | 8 | 85.4% | <0.001 | Random | 1.36 (1.14–1.63) | 3.370 | 0.001 |

| Prospective | 2 | 28.9% | 0.236 | Fixed | 2.18 (0.88–5.38) | 1.683 | 0.092 |

| Follow-up | |||||||

| <90 days | 6 | 13.1% | 0.331 | Fixed | 1.25 (1.11–1.40) | 3.648 | <0.001 |

| ≥90 days | 4 | 93.0% | <0.001 | Random | 1.51 (1.11–2.04) | 2.639 | 0.008 |

| CRP | |||||||

| Total | 10 | 76.3% | <0.001 | Random | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 2.631 | 0.009 |

| Design | |||||||

| Retrospective | 7 | 71.4% | 0.002 | Random | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 2.145 | 0.032 |

| Prospective | 3 | 80.1% | 0.007 | Random | 1.14 (0.96–1.37) | 1.477 | 0.140 |

| Follow-up | |||||||

| <90 days | 9 | 74.9% | <0.001 | Random | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 2.385 | 0.017 |

| ≥90 days | 1 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

Subgroup analysis of the association of inflammation indexes with mortality.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; WBC, white blood cell count; CRP, C-reactive protein.

No correlation was found between PLR and mortality in studies with follow-up duration of <90 days (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

The pooled analysis disclosed that the high level of WBC was correlated with raised mortality in retrospective studies [OR (95% CI): 1.36 (1.14, 1.63), p = 0.001], studies with a follow-up duration of <90 days [OR (95% CI): 1.25 (1.11, 1.40), p < 0.001], and studies with a follow-up duration of ≥90 days [OR (95% CI): 1.51 (1.11, 2.04), p = 0.008]. Regarding WBC for forecasting mortality, heterogeneity existed among retrospective studies and studies with a follow-up duration of ≥90 days (both I2 > 50.0%, p < 0.001). But it did not exist in studies with a follow-up duration of <90 days (I2 = 13.1%, p = 0.331) (Table 4).

The pooled analysis showed that the high level of CRP was associated with elevated mortality in retrospective studies [OR (95% CI): 1.02 (1.00, 1.03), p = 0.032] and studies with a follow-up duration of <90 days [OR (95% CI): 1.02 (1.00, 1.04), p = 0.017]. Heterogeneity existed among these studies that reported CRP for estimating mortality (both I2 > 50.0%, p < 0.01) (Table 4).

3.10 Subgroup analysis for the association between NLR and poor outcome based on sampling time

In studies with a sampling time at admission, 20 studies reported NLR for predicting poor outcome, and heterogeneity existed among these studies (I2 = 84.4%, p < 0.001). The random effect model exhibited that the high level of NLR was correlated with poor outcome [OR (95% CI): 1.19 (1.12, 1.27), p < 0.001]. In studies with a sampling time within 48 h after surgery, 2 studies reported NLR for predicting poor outcome, and there was no heterogeneity in these studies (I2 = 58.2%, p = 0.122). The random effect model suggested that the high level of NLR was related to a poor outcome [OR (95% CI): 1.24 (1.06, 1.44), p = 0.007] (Supplementary Table S2).

3.11 Publication bias

Funnel plots suggested that there might be a potential publication bias in NLR for predicting poor outcome (Figure 6A). However, publication bias might not exist in PLR (Figure 6B) and WBC (Figure 6C) for estimating poor outcome. Notably, potential publication bias might also exist in CRP for forecasting poor outcome (Figure 6D). In terms of mortality, NLR (Figure 6E), PLR (Figure 6F), and WBC (Figure 6G) for predicting mortality might have a low risk of publication bias. However, CRP for estimating mortality might have a high risk of publication bias (Figure 6H). Begg’s test disclosed that only NLR for predicting poor outcome (p < 0.001) and CRP for predicting mortality (p = 0.007) existed publication bias. Subsequently, the trim-and-filling method was applied to validate the stability, and it was found that the OR (95% CI) of NLR for estimating poor outcome before and after filling imputed missing studies was 0.07 (0.05–0.09) (p < 0.001) and 1.05 (1.03–1.07) (p < 0.001), which indicated the model was robust. Meanwhile, the OR (95% CI) of CRP for estimating mortality before and after filling imputed missing studies was 0.01 (0.01–0.02) (p < 0.001) and 1.01 (1.01–1.02) (p < 0.001), which indicated the model was stable.

Figure 6

Funnel plot for publication bias. Funnel plot of NLR (A), PLR (B), WBC (C), and CRP (D) for predicting poor outcome in ICH patients. Funnel plot of NLR (E), PLR (F), WBC (G), and CRP (H) for predicting mortality in ICH patients.

4 Discussion

Aggravated inflammation facilitates the progression of secondary brain injury, which may ultimately contribute to poor outcome in ICH patients (16). In this meta-analysis, it was discovered that the high level of NLR, WBC, and CRP were related to poor outcome in ICH patients. The potential reasons might be that: (1) after ICH, the neutrophils would rapidly reach the hemorrhage site and infiltrate the brain parenchyma, which impaired the blood–brain barrier and led to neurological injury, thereby resulting in poor outcome (16). In addition, the inflammatory response following ICH would further interfere with the function of the innate and adaptive immune cells, which might lead to adaptive immunosuppression (73–75). (2) increased leukocytes could also facilitate the neurotoxicity through production of matrix metalloproteinases, reactive oxygen species, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which further contributed brain injury (19). (3) CRP could activate the complement cascade and microglia, and promote the release of proinflammatory cytokines to aggravate secondary brain injury, which ultimately contributed to poor outcome (17, 76, 77). Taken together, considering the involvement of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and CRP in the brain injury after ICH, NLR, WBC, and CRP might have the ability to predict the poor outcome. Notably, heterogeneity existed among the studies that reported the correlation of NLR, WBC, and CRP with poor outcome in ICH patients. Therefore, the findings of this meta-analysis needed further validation.

Some studies also disclose the role of NLR, PLR, WBC, and CRP in forecasting mortality in ICH patients (25, 26, 33, 47). For instance, the high level of NLR independently predicts higher mortality in ICH patients (47). Meanwhile, the high level of WBC is also independently linked with increased mortality in ICH patients (25). Furthermore, another study indicates that the high level of CRP can estimate elevated mortality in ICH patients (33). However, one study figures out that PLR lacks the ability to predict mortality in ICH patients (26). In this meta-analysis, it was found that the high level of NLR, WBC, and CRP were correlated with increased mortality in ICH patients. The possible reasons might be that: (1) following ICH, neutrophils would impair the blood–brain barrier and induce neurological injury, which might further induce temporary immune suppression and lead to lymphocytopenia (16, 74, 78). Subsequently, lymphocytopenia would increase the risk of infection, which was responsible for mortality (73, 79). Therefore, the high level of NLR predicted elevated mortality in ICH patients. (2) the high level of NLR, WBC, and CRP could reflect exacerbated inflammatory status, and aggravated inflammation could facilitate hematoma expansion after ICH (80, 81). Then the expanded hematoma would further lead to intracranial hypertension, resulting in mortality (81). Conclusively, the high level of NLR, WBC, and CRP predicted raised mortality in ICH patients.

Further subgroup analysis discovered that in retrospective studies, the high level of NLP and WBC were related to poor outcome; meanwhile, the high level of NLR, WBC, and CRP were correlated with increased mortality in ICH patients. However, in prospective studies, only the high level of CRP estimated poor outcome, and only the high level of NLR predicted elevated mortality in ICH patients. A possible reason would be that selection bias and information bias would exist in retrospective studies, which might influence the prognostic effect of these inflammatory indexes (82, 83). Therefore, the findings of this meta-analysis should be read with caution, and more solid evidence was required. Apart from study design, subgroup analysis based on follow-up duration disclosed that in studies with a follow-up duration of ≥90 days, the high level of NLR, WBC, and CRP was related to poor outcome; the high level of NLR and WBC was correlated with increased mortality in ICH patients. In studies with a follow-up duration of <90 days, only the high level of NLR was linked to poor outcome, and the high level of NLR, WBC, and CRP was linked with raised mortality in ICH patients. A potential reason might be that aggravated inflammation after ICH might sustainably degrade immune resilience over time, which increased the risk of infection and obstructed the recovery from the disease, contributing to a poor outcome and increased mortality (84, 85). Considering that the longer follow-up duration might more objectively reflect the prognosis of ICH patients, it was speculated that the high level of NLR, WBC, and CRP had a good ability to predict poor outcome, and the high level of NLR and WBC could estimate increased mortality in ICH patients. However, more evidence was required to validate this speculation. Notably, limited by the number of studies, whether the prognostic effect of PLR and CRP would be affected by follow-up duration should be further studied. In addition, other factors, such as hematoma size, surgery, co-infections, etc., might also affect the prognosis of ICH patients, which could be a study direction for subsequent studies. Moreover, this meta-analysis also discovered that in studies with a sampling time at admission and within 48 h after surgery, the high level of NLR was correlated with poor outcome. Based on this finding, it was speculated that the ability of NLR to predict poor outcome in ICH patients was not affected by the sampling times. However, limited by the sample size of this meta-analysis, the number of studies that could be included in the subgroup analysis was small, especially for the studies in which the sampling times were not at admission. Therefore, the findings of this meta-analysis should be further validated.

Limitations could not be omitted in this meta-analysis. Firstly, the regions of the included studies differed, and most included studies were conducted in China. Thus, the generalization of the findings of this meta-analysis should be validated. Secondly, some studies had different sampling times, which might affect the results. Thirdly, many screened studies had a retrospective design; thus, selection bias and information bias might exist. Fourthly, some factors, such as sampling time and follow-up duration, would affect the role of PLR in predicting the prognosis of ICH patients. In addition, the number of studies that reported PLR for predicting poor outcome (N = 4) and mortality (N = 2) in ICH patients was relatively small, which limited the statistical power and the conduction of relevant subgroup analyses. Therefore, more evidence was required to validate the prognostic implication of PLR in ICH patients. Fifthly, aneurysmal cerebral hemorrhage should be excluded due to differences in etiology. However, only Radu and Kim clearly indicated that they excluded aneurysmal cerebral hemorrhage patients, while other studies did not provide this information. Therefore, the findings of this meta-analysis should be further validated.

This meta-analysis concludes that the high level of NLR, WBC, and CRP estimates poor outcome and elevated mortality in ICH patients. Although these indexes are dynamically changing, in our opinion, their variation is still within an abnormal range. Therefore, the high level of NLR, WBC, and CRP could still indicate aggravated inflammation after ICH. Clinically, given that the detection of NLR, WBC, and CRP is simple and the high level of these indexes may provide prognostic information of ICH patients, the detection of these indexes should be widely applied in ICH patients. In addition, considering the high level of NLR, WBC, and CRP could reflect aggravated inflammation, acute interventions that target inflammation may help to improve the prognosis of ICH patients.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2023.1288377/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Puy L Parry-Jones AR Sandset EC Dowlatshahi D Ziai W Cordonnier C . Intracerebral haemorrhage. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2023) 9:14. doi: 10.1038/s41572-023-00424-7

2.

Collaborators GBDS . Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. (2021) 20:795–820. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0

3.

Magid-Bernstein J Girard R Polster S Srinath A Romanos S Awad IA et al . Cerebral hemorrhage: pathophysiology, treatment, and future directions. Circ Res. (2022) 130:1204–29. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319949

4.

Li X Zhang L Wolfe CDA Wang Y . Incidence and Long-term survival of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage over time: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:819737. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.819737

5.

Wang S Zou XL Wu LX Zhou HF Xiao L Yao T et al . Epidemiology of intracerebral hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:915813. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.915813

6.

Parry-Jones AR Moullaali TJ Ziai WC . Treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage: from specific interventions to bundles of care. Int J Stroke. (2020) 15:945–53. doi: 10.1177/1747493020964663

7.

Schrag M Kirshner H . Management of Intracerebral Hemorrhage: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 75:1819–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.10.066

8.

Zhao W Wu C Stone C Ding Y Ji X . Treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage: current approaches and future directions. J Neurol Sci. (2020) 416:117020. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.117020

9.

Hostettler IC Seiffge DJ Werring DJ . Intracerebral hemorrhage: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Expert Rev Neurother. (2019) 19:679–94. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2019.1623671

10.

An SJ Kim TJ Yoon BW . Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features of intracerebral hemorrhage: An update. J Stroke. (2017) 19:3–10. doi: 10.5853/jos.2016.00864

11.

Pasi M Casolla B Kyheng M Boulouis G Kuchcinski G Moulin S et al . Long-term mortality in survivors of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Int J Stroke. (2021) 16:448–55. doi: 10.1177/1747493020954946

12.

Poon MT Fonville AF Al-Shahi SR . Long-term prognosis after intracerebral haemorrhage: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2014) 85:660–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306476

13.

Fernando SM Qureshi D Talarico R Tanuseputro P Dowlatshahi D Sood MM et al . Intracerebral hemorrhage incidence, mortality, and association with Oral anticoagulation use: a population study. Stroke. (2021) 52:1673–81. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032550

14.

Pasi M Casolla B Kyheng M Boulouis G Kuchcinski G Moulin S et al . Long-term functional decline of spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage survivors. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2021) 92:249–54. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-324741

15.

Pinho J Costa AS Araujo JM Amorim JM Ferreira C . Intracerebral hemorrhage outcome: a comprehensive update. J Neurol Sci. (2019) 398:54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2019.01.013

16.

Chen S Li L Peng C Bian C Ocak PE Zhang JH et al . Targeting oxidative stress and inflammatory response for blood-brain barrier protection in intracerebral hemorrhage. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2022) 37:115–34. doi: 10.1089/ars.2021.0072

17.

Zhu H Wang Z Yu J Yang X He F Liu Z et al . Role and mechanisms of cytokines in the secondary brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage. Prog Neurobiol. (2019) 178:101610. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2019.03.003

18.

Wang J Du Y Wang A Zhang X Bian L Lu J et al . Systemic inflammation and immune index predicting outcomes in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurol Sci. (2023) 44:2443–53. doi: 10.1007/s10072-023-06632-z

19.

Nguyen HX O'Barr TJ Anderson AJ . Polymorphonuclear leukocytes promote neurotoxicity through release of matrix metalloproteinases, reactive oxygen species, and TNF-alpha. J Neurochem. (2007) 102:900–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04643.x

20.

Prass K Meisel C Hoflich C Braun J Halle E Wolf T et al . Stroke-induced immunodeficiency promotes spontaneous bacterial infections and is mediated by sympathetic activation reversal by poststroke T helper cell type 1-like immunostimulation. J Exp Med. (2003) 198:725–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021098

21.

Scull CM Hays WD Fischer TH . Macrophage pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion is enhanced following interaction with autologous platelets. J Inflamm (Lond). (2010) 7:53. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-7-53

22.

Kuhlmann CR Librizzi L Closhen D Pflanzner T Lessmann V Pietrzik CU et al . Mechanisms of C-reactive protein-induced blood-brain barrier disruption. Stroke. (2009) 40:1458–66. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.535930

23.

Juma WM Lira A Marzuk A Marzuk Z Hakim AM Thompson CS . C-reactive protein expression in a rodent model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Brain Res. (2011) 1414:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.07.047

24.

Yan XJ Yu GF Jie YQ Fan XF Huang Q Dai WM . Role of galectin-3 in plasma as a predictive biomarker of outcome after acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurol Sci. (2016) 368:121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.06.071

25.

Tao C Hu X Wang J Ma J Li H You C . Admission neutrophil count and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predict 90-day outcome in intracerebral hemorrhage. Biomark Med. (2017) 11:33–42. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2016-0187

26.

Fonseca S Costa F Seabra M Dias R Soares A Dias C et al . Systemic inflammation status at admission affects the outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage by increasing perihematomal edema but not the hematoma growth. Acta Neurol Belg. (2021) 121:649–59. doi: 10.1007/s13760-019-01269-2

27.

Zhao Y Xie Y Li S Hu M . The predictive value of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio on 30-day outcomes in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage patients after surgical treatment: a retrospective analysis of 128 patients. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:963397. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.963397

28.

Shi M Li XF Zhang TB Tang QW Peng M Zhao WY . Prognostic role of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in intracerebral hemorrhage: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front Neurosci. (2022) 16:825859. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.825859

29.

Guyatt GH Oxman AD Kunz R Atkins D Brozek J Vist G et al . GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. (2011) 64:395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.012

30.

Stang A . Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. (2010) 25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z

31.

Diedler J Sykora M Hahn P Rupp A Rocco A Herweh C et al . C-reactive-protein levels associated with infection predict short- and long-term outcome after supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2009) 27:272–9. doi: 10.1159/000199465

32.

Alexandrova ML Danovska MP . Serum C-reactive protein and lipid hydroperoxides in predicting short-term clinical outcome after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci. (2011) 18:247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.07.125

33.

Di Napoli M Godoy DA Campi V del Valle M Pinero G Mirofsky M et al . C-reactive protein level measurement improves mortality prediction when added to the spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage score. Stroke. (2011) 42:1230–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604983

34.

Rodriguez-Yanez M Brea D Arias S Blanco M Pumar JM Castillo J et al . Increased expression of toll-like receptors 2 and 4 is associated with poor outcome in intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neuroimmunol. (2012) 247:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.03.019

35.

Lopponen P Qian C Tetri S Juvela S Huhtakangas J Bode MK et al . Predictive value of C-reactive protein for the outcome after primary intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. (2014) 121:1374–9. doi: 10.3171/2014.7.JNS132678

36.

Adeoye O Walsh K Woo JG Haverbusch M Moomaw CJ Broderick JP et al . Peripheral monocyte count is associated with case fatality after intracerebral hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2014) 23:e107–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.09.006

37.

Walsh KB Sekar P Langefeld CD Moomaw CJ Elkind MS Boehme AK et al . Monocyte count and 30-day case fatality in intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. (2015) 46:2302–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009880

38.

Yu S Arima H Heeley E Delcourt C Krause M Peng B et al . White blood cell count and clinical outcomes after intracerebral hemorrhage: the INTERACT2 trial. J Neurol Sci. (2016) 361:112–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.12.033

39.

Lattanzi S Cagnetti C Provinciali L Silvestrini M . Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts the outcome of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. (2016) 47:1654–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013627

40.

Wang F Hu S Ding Y Ju X Wang L Lu Q et al . Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and 30-day mortality in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2016) 25:182–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.09.013

41.

Giede-Jeppe A Bobinger T Gerner ST Sembill JA Sprugel MI Beuscher VD et al . Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independent predictor for in-hospital mortality in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2017) 44:26–34. doi: 10.1159/000468996

42.

Sun Y You S Zhong C Huang Z Hu L Zhang X et al . Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and the hematoma volume and stroke severity in acute intracerebral hemorrhage patients. Am J Emerg Med. (2017) 35:429–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.11.037

43.

Bolayir A Cigdem B Gokce SF Bolayir HA Kayim Yildiz O Bolayir E et al . The effect of Eosinopenia on mortality in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2017) 26:2248–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.05.007

44.

Elhechmi YZ Hassouna M Cherif MA Ben Kaddour R Sedghiani I Jerbi Z . Prognostic value of serum C-reactive protein in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: when should we take the sample?J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2017) 26:1007–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.11.129

45.

Lattanzi S Cagnetti C Rinaldi C Angelocola S Provinciali L Silvestrini M . Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio improves outcome prediction of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurol Sci. (2018) 387:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2018.01.038

46.

Fan Z Hao L Chuanyuan T Jun Z Xin H Sen L et al . Neutrophil and platelet to lymphocyte ratios in associating with blood glucose admission predict the functional outcomes of patients with primary brainstem hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. (2018) 116:e100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.089

47.

Wang F Wang L Jiang TT Xia JJ Xu F Shen LJ et al . Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independent predictor of 30-day mortality of intracerebral hemorrhage patients: a validation cohort study. Neurotox Res. (2018) 34:347–52. doi: 10.1007/s12640-018-9890-6

48.

Qi H Wang D Deng X Pang X . Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio is an independent predictor for neurological deterioration and 90-day mortality in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Med Sci Monit. (2018) 24:9282–91. doi: 10.12659/MSM.911645

49.

Zhang F Tao C Hu X Qian J Li X You C et al . Association of Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio on 90-day functional outcome in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage undergoing surgical treatment. World Neurosurg. (2018) 119:e956–61. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.08.010

50.

Guo R Wu Y Chen R Yu Z You C Ma L et al . Clinical value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in primary intraventricular hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. (2019) 127:e1051–6. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.04.040

51.

Qin J Li Z Gong G Li H Chen L Song B et al . Early increased neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with poor 3-month outcomes in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0211833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211833

52.

Wang F Xu F Quan Y Wang L Xia JJ Jiang TT et al . Early increase of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts 30-day mortality in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. CNS Neurosci Ther. (2019) 25:30–5. doi: 10.1111/cns.12977

53.

Zhang F Ren Y Fu W Wang Y Qian J Tao C et al . Association between neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and blood glucose level at admission in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:15623. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52214-5

54.

Zhang F Ren Y Fu W Yang Z Wen D Hu X et al . Predictive accuracy of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio on Long-term outcome in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. (2019) 125:e651–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.01.143

55.

Zhang F Ren Y Shi Y Fu W Tao C Li X et al . Predictive ability of admission neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio on short-term outcome in patients with spontaneous cerebellar hemorrhage. Medicine (Baltimore). (2019) 98:e16120. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016120

56.

Chen W Wang X Liu F Tian Y Chen J Li G et al . The predictive role of postoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio for 30-day mortality after intracerebral hematoma evacuation. World Neurosurg. (2020) 134:e631–5. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.10.154

57.

Sagar R Kumar A Verma V Yadav AK Raj R Rawat D et al . Incremental accuracy of blood biomarkers for predicting clinical outcomes after intracerebral hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2021) 30:105537. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105537

58.

Menon G Johnson SE Hegde A Rathod S Nayak R Nair R . Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio – a novel prognostic marker following spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2021) 200:106339. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106339

59.

Gusdon AM Thompson CB Quirk K Mayasi YM Avadhani R Awad IA et al . CSF and serum inflammatory response and association with outcomes in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage with intraventricular extension: an analysis of the CLEAR-III trial. J Neuroinflammation. (2021) 18:179. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02224-w

60.

Mackey J Blatsioris AD Saha C Moser EAS Carter RJL Cohen-Gadol AA et al . Higher monocyte count is associated with 30-day case fatality in intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. (2021) 34:456–64. doi: 10.1007/s12028-020-01040-z

61.

Li J Yuan Y Liao X Yu Z Li H Zheng J . Prognostic significance of admission systemic inflammation response index in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a propensity score matching analysis. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:718032. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.718032

62.

Radu RA Terecoasa EO Tiu C Ghita C Nicula AI Marinescu AN et al . Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Medicina (Kaunas). (2021) 57:622. doi: 10.3390/medicina57060622

63.

Yang W Yuan Y Li J Shuai Y Liao X Yu Z et al . Prognostic significance of the combined score of plasma fibrinogen and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Dis Markers. (2021) 2021:7055101. doi: 10.1155/2021/7055101

64.

Bender M Naumann T Uhl E Stein M . Early serum biomarkers for intensive care unit treatment within the first 24 hours in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. (2021) 82:138–46. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1716516

65.

Luo S Yang WS Shen YQ Chen P Zhang SQ Jia Z et al . The clinical value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, and D-dimer-to-fibrinogen ratio for predicting pneumonia and poor outcomes in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:1037255. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1037255

66.

Du Y Wang A Zhang J Zhang X Li N Liu X et al . Association between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and adverse clinical prognosis in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2022) 18:985–93. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S358078

67.

Wang D Wang J Li Z Gu H Yang K Zhao X et al . C-reaction protein and the severity of intracerebral hemorrhage: a study from Chinese stroke center Alliance. Neurol Res. (2022) 44:285–90. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2021.1980842

68.

Chu H Huang C Zhou Z Tang Y Dong Q Guo Q . Inflammatory score predicts early hematoma expansion and poor outcomes in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Int J Surg. (2023) 109:266–76. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000191

69.

Zhang GJ Wang H Gao LC Zhao JY Zhang T You C et al . Constructing and validating a nomogram for survival in patients without hypertension in hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage-related locations. World Neurosurg. (2023) 172:e256–66. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.01.006

70.

Zhang J Liu C Hu Y Yang A Zhang Y Hong Y . The trend of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage and the predictive value of short-term postoperative prognosis in patients. Front Neurol. (2023) 14:1189898. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1189898

71.

Shi J Liu Y Wei L Guan W Xia W . Admission neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio to predict 30-day mortality in severe spontaneous basal ganglia hemorrhage. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:1062692. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1062692

72.

Kim Y Sohn JH Kim C Park SY Lee SH . The clinical value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio for predicting hematoma expansion and poor outcomes in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:3004. doi: 10.3390/jcm12083004

73.

Esmaeili A Dadkhahfar S Fadakar K Rezaei N . Post-stroke immunodeficiency: effects of sensitization and tolerization to brain antigens. Int Rev Immunol. (2012) 31:396–409. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2012.723078

74.

Dirnagl U Klehmet J Braun JS Harms H Meisel C Ziemssen T et al . Stroke-induced immunodepression: experimental evidence and clinical relevance. Stroke. (2007) 38:770–3. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251441.89665.bc

75.

Zhang J Shi K Li Z Li M Han Y Wang L et al . Organ- and cell-specific immune responses are associated with the outcomes of intracerebral hemorrhage. FASEB J. (2018) 32:220–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700324r

76.

Di Napoli M Slevin M Popa-Wagner A Singh P Lattanzi S Divani AA . Monomeric C-reactive protein and cerebral hemorrhage: from bench to bedside. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1921. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01921

77.

Holste K Xia F Garton HJL Wan S Hua Y Keep RF et al . The role of complement in brain injury following intracerebral hemorrhage: a review. Exp Neurol. (2021) 340:113654. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113654

78.

Lattanzi S Brigo F Trinka E Cagnetti C Di Napoli M Silvestrini M . Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in acute cerebral hemorrhage: a system review. Transl Stroke Res. (2019) 10:137–45. doi: 10.1007/s12975-018-0649-4

79.

Morotti A Marini S Jessel MJ Schwab K Kourkoulis C Ayres AM et al . Lymphopenia, infectious complications, and outcome in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. (2017) 26:160–6. doi: 10.1007/s12028-016-0367-2

80.

Jiang C Wang Y Hu Q Shou J Zhu L Tian N et al . Immune changes in peripheral blood and hematoma of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. FASEB J. (2020) 34:2774–91. doi: 10.1096/fj.201902478R

81.

Li Z You M Long C Bi R Xu H He Q et al . Hematoma expansion in intracerebral hemorrhage: An update on prediction and treatment. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:702. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00702

82.

Soni PD . Selection Bias in population registry-based comparative effectiveness research. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2019) 103:1058–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.12.011

83.

Mann CJ . Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies. Emerg Med J. (2003) 20:54–60. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.1.54

84.

Ahuja SK Manoharan MS Lee GC McKinnon LR Meunier JA Steri M et al . Immune resilience despite inflammatory stress promotes longevity and favorable health outcomes including resistance to infection. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:3286. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38238-6

85.

Dantzer R Cohen S Russo SJ Dinan TG . Resilience and immunity. Brain Behav Immun. (2018) 74:28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.08.010

Summary

Keywords

intracerebral hemorrhage, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, white blood cell, C-reactive protein, prognosis

Citation

Guo P and Zou W (2024) Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, white blood cell, and C-reactive protein predicts poor outcome and increased mortality in intracerebral hemorrhage patients: a meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 14:1288377. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1288377

Received

22 September 2023

Accepted

29 December 2023

Published

15 January 2024

Volume

14 - 2023

Edited by

Roberto Paganelli, YDA, Institute for Advanced Biologic Therapies, Italy

Reviewed by

Angelo Di Iorio, University of Studies G. d'Annunzio Chieti and Pescara, Italy

Jesus Miguel Pradillo, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Guo and Zou.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Zou, weiqiangzhizbj@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.