Abstract

Background and purpose:

Isolated insular strokes (IIS) are a rare occurrence due to the frequent concomitant involvement of adjacent territories, supplied by the M2 segment of the middle cerebral artery (MCA), and clinical aspects are sometimes contradictory. We aimed to describe clinical and radiological characteristics of a pure IIS case series, focusing on its functional outcome and cardiac involvement.

Methods:

We identified 15 isolated insular ischemic strokes from a pool of 563 ischemic strokes occurred between January 2020 and December 2021. Data collection consisted of demographic and baseline clinical characteristics, comorbidities, electrocardiograms, echocardiograms, stroke topography and etiology, reperfusive treatments, and outcome measures. Descriptive statistical analysis was carried out.

Results:

Newly detected cardiovascular alterations were the prevalent atypical presentation. Cardioembolism was the most frequent etiology. Most of patients had major neurological improvement at discharge and good outcome at 3-months follow-up.

Discussion and conclusion:

IIS are extremely rare, representing according to our study about 2.6% ischemic strokes cases per year, and patients have peculiar clinical manifestations, such as dysautonomia and awareness deficits. Our data suggest the possibility for these patients to completely recover after acute ischemic stroke notwithstanding the pivotal role of the insula in cerebral connections and the frequent association with MCA occlusion. Moreover, given the central role of the insula in regulating autonomic functions, newly detected cardiac arrhythmias must be taken into consideration, as well as a full diagnostic work-up for the research of cardioembolic sources. To our knowledge, this is the largest monocentric case series of IIS and it might be useful for future systematic reviews.

1 Introduction

The insular cortex, deeply located in the Sylvian fissure and separating temporal lobe from parietal and frontal lobes, is a highly connected integrative region, functionally divided into three zones: the posterior insular cortex (PIC), the middle insular cortex (MIC) and the anterior insular cortex (AIC). Afferences from the solitary nuclei and the spinal lamina I neurons project to the PIC, providing an interoceptive representation of the body physiological condition. This information is processed in the MIC and integrated with other inputs coming from multiple sources, in particular sensory cortex, that conveys emotional information from the external world, the cingulate cortex and the amygdala, providing homeostatic information on the motivational state. Finally, the inputs converge upon the AIC where new integrative processes are taking place; particularly auditory and language tasks activate the dorsal part of the AIC, motor tasks activate both anterior and posterior insula, and so on (1, 2).

This high level of integration may explain the extreme variety of manifestations in case of insular stroke. However, isolated insular strokes are rare, due to the frequent concomitant involvement of adjacent territories, supplied by the M2 segment of the middle cerebral artery (3).

For these reasons, clinical aspects of isolated insula strokes are sometimes contradictory, even if literature is homogeneous in describing a generally good outcome for isolated insular stroke (IIS) (4, 5).

In the present work, we aimed to describe clinical and radiological characteristics of pure ischemic stroke case series, trying to aggregate and correlate them according to the functional topography of the insula, and especially focusing on its functional outcome and cardiac involvement.

2 Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 563 patients diagnosed with first ever ischemic stroke, at the Stroke Unit of “Santa Maria della Misericordia” University Hospital of Udine (Italy), from January 1st, 2020, to December 31st, 2021.

We considered 113 patients with ischemic insular cortex involvement and, among them, we selected only isolated insular ischemic strokes (IIS), visually assessed by a board-certified neuroradiologist on non-contrast computerized tomography (NCCT) scans, acquired 24–48 h after the acute event or, when available, on diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DWI or DW-MRI) scans.

Isolated insular lesions were clustered based on the involvement of anterior insular cortex (AIC), posterior insular cortex (PIC), and total insular cortex (TIC).

Data collection from medical charts included demographic and baseline clinical characteristics, comorbidities, including the presence of leukoaraiosis-defined as the presence of hypodense periventricular white-matter lesions at CT scan (4), stroke severity measured by the incoming National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and initial disability measured by the incoming modified Rankin Scale (mRS), electrocardiogram (ECG), and echocardiogram characteristics. Cardiac rhythm monitoring with 12-lead ECG lasted meanly 48 h.

We defined patients’ clinical presentation according to the latest comprehensive literature review on strokes confined to the insula by Di Stefano et al. (5) We categorized motor and somatosensory deficits, dysarthria, aphasia, and vestibular-like syndrome as “typical” symptoms, whereas dysphagia, awareness deficits, gustatory disturbances, dysautonomia, neuropsychiatric or auditory disturbances and headache were categorized as “atypical” presentations.

Stroke etiology was defined according to the TOAST classification (6). In-hospital therapies and procedures data included antihypertensive and antiarrhythmic infusive therapies, intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) with tissue-type plasminogen activator (rT-PA) and mechanical thrombectomy (MT). Outcome measures included NIHSS and mRS at discharge, in-hospital mortality, major neurological improvement at discharge (improvement of 8 points on the NIHSS from baseline or a NIHSS score of 0 or 1 at discharge), 3-months-good-outcome measured by mRS of 0–2 and 3-months-mortality. Good outcome was defined as mRS of 0–2 to include patients with functional independence 3 months after stroke, in line with previous stroke outcome studies, according to the definition of mRS of 2 (“slight disability; unable to carry out all previous activities, but able to look after own affairs without assistance”) (7, 8).

When possible, we stratified variables in continuous and categorical, analyzing each means e medians. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with Lilliefors significance correction was performed to test the normality of continuous variables. Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac OS, version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Schematic figures were realized with BioRender©.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their representatives. The study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association and it was approved by the local ethics committee (Ref. No. CEUR-2020-Os-173).

3 Results

3.1 Demographic characteristics

We found 15 patients with IIS out of 563 ischemic stroke cases (15/563–2.6%). The mean age was 77 years (range, 35–89 years). There was not any prevalence regarding patients’ gender (8 males, 7 females) (Table 1).

Table 1

| Patient ID | Demographic data | Medical history and comorbidities | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age (years) | Hypertension | Diabetes | Dyslipidaemia | Active smoke | BMI | Previous MI | Previous stroke | Leukoaraiosis | |

| 1 | Female | 75 | Yes | No | No | No | 48 | No | No | No |

| 2 | Female | 71 | Yes | No | No | No | 33 | No | No | No |

| 3 | Male | 80 | No | No | No | No | 26 | No | No | Yes |

| 4 | Female | 80 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 38 | No | No | Yes |

| 5 | Male | 67 | No | No | Yes | No | 31 | No | No | Yes |

| 6 | Male | 83 | Yes | Yes | No | No | 29 | Yes | No | No |

| 7 | Male | 35 | No | No | Yes | No | 34 | No | No | No |

| 8 | Male | 77 | No | No | Yes | No | 27 | No | No | No |

| 9 | Male | 87 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 28 | No | No | No |

| 10 | Female | 73 | No | No | No | No | 22 | No | No | Yes |

| 11 | Female | 88 | Yes | No | No | No | 21 | No | Yes | No |

| 12 | Female | 88 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 20 | No | No | Yes |

| 13 | Male | 61 | No | No | No | No | 26 | No | No | No |

| 14 | Male | 89 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 24 | Yes | No | No |

| 15 | Female | 63 | No | Yes | No | No | 23 | No | No | No |

| Overall n (%) or median | Female, 7 (46.7%) | 77 [35–89] | Yes, 8 (53.3%) | Yes, 2 (13.3%) | Yes, 7 (46.7%) | Yes, 0 (0%) | 29 ± 7 | Yes, 2 (13.3%) | Yes, 1 (6.6%) | Yes, 5 (33.3%) |

| [IQR] or mean ± sd | Male, 8 (53.3%) | No, 7 (46.7%) | No, 13 (86.7%) | No, 8 (53.3%) | No, 15 (100%) | No, 13 (86.7%) | No, 14 (93.4%) | No, 10 (66.7%) | ||

Demographic data and medical history of patients.

BMI, body mass index; MI, myocardial infarction.

3.2 Medical history and comorbidities

The most frequent comorbidity was hypertension (8/15–53.3%), followed by dyslipidemia (7/15–46.7%). Two patients had diabetes mellitus type 2 (13.3%). Evidence of leukoaraiosis was found in five patients (33.3%): of them, only one patient has already been diagnosed with leukoaraiosis (1/15–6.6%), while in 26.6% (4/15) of cases it was discovered at the time of the AIS. We found one patient with history of previous ischemic stroke (6.6%) and two with previous acute myocardial infarction (13.3%). Most subjects presented body mass index (BMI) over the normal weight interval (mean ± sd, 29 ± 7). None of the patients was a smoker (Table 1).

3.3 Cardiological characteristics

Five patients had history of atrial fibrillation (AF) (33.3%). We found four patients with newly detected AF during the hospitalization (26.6%). The other most reported arrhythmias were atrioventricular block (3/15–20.0%), ventricular extrasystoles (4/15–26.6%) and right bundle branch block (2/15–13.3%). Of the three patients with atrioventricular block (AVB), two had first grade AVB with mean PR interval of 295 ms, while another patient had type I second grade AVB (mean PR intervals ranged between 180 to 455 ms). We collected specific data from ECGs performed in the emergency room (ER) setting at admission: the mean value of QT corrected with Bazett formula (QTcB) was 443 ± 58 ms, while mean RR interval was 725 ± 255 ms. Five patients were already on treatment with antiarrhythmic oral therapy (33.3%). One patient needed intravenous antiarrhythmic therapy for persistent AF with fast ventricular rate. At admission, eight subjects (53.3%) were already on treatment with antihypertensive oral therapy. The median blood pressure detected in ER was 160/90 mmHg. We found three patients with hypertensive crisis, defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) > 180 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) > 120 mmHg (20.0%). Of these patients, one received intravenous antihypertensive therapy, due to persistent elevated SBP and DBP values. Echocardiography was performed in 9/15 patients (60.0%): left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) mean value was 61 (±10 standard deviation). Three patients presented mildly reduced LVEF (LVEF range 48–54%) (3/15–20.0%); one had wall motion abnormalities (6.6%) while other three had severe left atrial dilatation (20.0%) (Figure 1; Tables 2, 3).

Figure 1

Schematic representation of cardiological characteristics concerning ECG and echocardiogram findings (percentages refer to Tables 2, 3). 26.7% of patients had newly detected atrial fibrillation (AF) and 53.3% of patients had other types of newly detected arrhythmias. Cardiovascular alterations were the most prevalent atypical etiology of isolated insular stroke (IIS) patients.

Table 2

| Patient ID | Cardiological characteristics | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhythm | Blood pressure | ||||||||||

| AF history | Newly-detected AF | Other abnormal rhythm findings | Antiarrhythmic home therapy | R-R interval (ms) | QTcB (ms) | IV antiarrhythmic therapy | Antihypertensive home therapy | SBP/DBP (mmHg) | Hypertensive crisis during hospitalization | IV antihypertensive therapy | |

| 1 | Yes | No | No | Yes | 714 | 447 | No | Yes | na | Yes | No |

| 2 | No | Yes | Mobitz type I second grade AVB | No | 316 | na | No | Yes | 165/100 | No | No |

| 3 | No | Yes | First grade AVB, VES | No | 942 | 491 | No | No | 150/90 | No | No |

| 4 | Yes | No | No | Yes | 902 | 425 | No | Yes | 160/80 | No | No |

| 5 | No | No | No | No | 429 | 294 | No | No | 155/80 | No | No |

| 6 | Yes | No | RBBB | Yes | 333 | 485 | No | Yes | 160/75 | No | No |

| 7 | No | No | VES | No | 737 | 461 | No | No | na | No | No |

| 8 | No | No | No | No | 853 | 420 | No | No | 175/100 | No | No |

| 9 | No | Yes | No | No | 1,008 | 404 | No | Yes | 160/85 | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | Yes | No | No | Yes | 800 | 549 | No | No | 188/107 | No | No |

| 11 | Yes | No | No | Yes | 965 | 437 | No | Yes | 175/80 | No | No |

| 12 | No | No | CAM | No | 819 | 401 | No | Yes | 156/96 | Yes | No |

| 13 | No | No | VES, SVES | No | 908 | 451 | No | No | 145/90 | No | No |

| 14 | No | No | First grade AVB, RBBB, LAFB | No | 870 | 483 | No | Yes | 150/95 | No | No |

| 15 | No | Yes | No | No | 280 | 457 | Yes | No | na | No | No |

| Overall n (%) or median | Yes, 5 (33.3%) | Yes, 4 (26.7%) | Yes, 8 (53.3%) | Yes, 5 (33.3%) | 725 ± 255 | 443 ± 58 | Yes, 1 (6.7%) | Yes, 8 (53.3%) | SBP 160 [145–188], DBP 90 [75–107] | Yes, 3 (20.0%) | Yes, 1 (6.7%) |

| [IQR] or mean ± sd | No, 10 (66.7%) | No, 11 (73.7%) | No, 7 (46.7%) | No, 10 (66.7%) | No, 14 (93.3%) | No, 7 (46.7%) | No, 12 (80.0%) | No, 14 (93.3%) | |||

Cardiological characteristics concerning heart rhythm and blood pressure.

AF, atrial fibrillation; AVB, atrioventricular block; VES, ventricular extrasystoles; SVES, supraventricular extrasystoles; RBBB, right bundle branch block; CAM, chaotic atrial rhythm; LAFB, left anterior fascicular block; QTcB, QT corrected with Bazett formula; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; na, not available.

Table 3

| Patient ID | Cardiological characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiographic findings | |||

| LVEF (%) | LV wall motion abnormalities | LA dilatation | |

| 1 | – | – | – |

| 2 | 61 | No | Severe |

| 3 | – | – | – |

| 4 | – | – | – |

| 5 | 72 | No | No |

| 6 | 48 | Yes (medio-basal inferior wall hypokinesia-akinesia) | No |

| 7 | – | – | – |

| 8 | 54 | No | No |

| 9 | 56 | No | Severe |

| 10 | 51 | No | No |

| 11 | – | – | – |

| 12 | 77 | No | Severe |

| 13 | 69 | No | No |

| 14 | 59 | No | No |

| 15 | na | na | na |

| Overall n (%) or median | 61 ± 10 | Yes, 1 (6.7%) | Yes, 3 (20.0%) |

| No, 8 (53.3%) | No, 6 (40.0%) | ||

| [IQR] or mean ± sd | na, 1 (6.7%) | na, 1 (6.7%) | |

Cardiological characteristics concerning echocardiographic findings.

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LV, left ventricle; LA, left atrium; na, not available.

3.4 Clinical symptoms

All the 15 patients presented typical symptoms (100%). The most frequent manifestation was language disorder (14/15–93.3%), followed by motor deficits (10/15–66.6%) and somatosensory deficits (7/15–46.6%). Eleven patients presented atypical symptoms (11/15–73.7%), particularly the majority with newly-detected cardiovascular alterations (10/15–66.6%), followed by spatial and awareness deficits (2/15–13.3%), space and time disorientation (1/15–6.7%) and headache (1/15–6.7%). Only one patient presented vestibular-like syndrome (1/15–6.7%) categorized in the typical symptoms group (Figure 2; Table 4).

Figure 2

Schematic representation of clinical symptoms (percentages refer to Table 4). In order of frequency, typical symptoms were language disorder (93.3%), motor deficits (66.7%), somatosensory deficits (46.7%) and vestibular-like syndrome (6.7%), while atypical symptoms were newly detected cardiovascular alterations (66.7%), spatial and awareness deficits (13.3%), space and time disorientation (6.7%) and headache (6.7%).

Table 4

| Patient ID | Topography of lesion | Clinical symptoms | Stroke etiology | Reperfusion treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site and side | LVO | Typical symptoms | Atypical symptoms | TOAST classification | Type of procedure | |

| 1 | TIC, right hemisphere | M1 | Unilateral weakness, somatosensory deficits | Hemineglect, cardiovascular alterations | CE | MT |

| 2 | TIC, left hemisphere | No | Somatosensory deficits, non-fluent aphasia | Cardiovascular alterations | CE | IVT |

| 3 | AIC, left hemisphere | M2 | Unilateral weakness, global aphasia | Cardiovascular alterations | CE | IVT + MT |

| 4 | PIC, left hemisphere | M2-M3 | Fluent aphasia | Temporal and spatial disorientation | CE | None |

| 5 | PIC, left hemisphere | M2 | Global aphasia | - | UND | IVT + MT |

| 6 | PIC, left hemisphere | M2 | Unilateral weakness, somatosensory deficits, global aphasia | Cardiovascular alterations | LAD | MT |

| 7 | AIC, left hemisphere | M2 | Unilateral weakness, non-fluent aphasia | Cardiovascular alterations | UND | IVT + MT |

| 8 | TIC, right hemisphere | No | Unilateral weakness, somatosensory deficits, dysarthria | – | UND | IVT |

| 9 | AIC, left hemisphere | M1 | Unilateral weakness, global aphasia | Cardiovascular alterations | CE | IVT + MT |

| 10 | AIC, left hemisphere | M1-M2 | Unilateral weakness, non-fluent aphasia | – | CE | MT |

| 11 | TIC, left hemisphere | M1 | Unilateral weakness, somatosensory deficits, global aphasia | – | LAD | MT |

| 12 | TIC, left hemisphere | No | Global aphasia | Cardiovascular alterations | UND | None |

| 13 | PIC, left hemisphere | No | Transient somatosensory deficits, dysarthria, vestibular-like syndrome | Headache, cardiovascular alterations | CE | None |

| 14 | PIC, left hemisphere | M1 | Unilateral weakness, dysarthria | Cardiovascular alterations | UND | IVT + MT |

| 15 | TIC, right hemisphere | M1-M2 | Unilateral weakness, somatosensory deficits, dysarthria | Hemineglect, cardiovascular alterations | CE | IVT + MT |

| Overall n (%) or median | AIC, 4 (26.6%) | Yes, 11 (73.3%) | Unilateral weakness, 10 (66.7%) | Hemineglect, 2 (13.3%) | LAD, 2 (13.3%) | IVT, 2 (13.3%) |

| [IQR] or mean ± sd | PIC, 5 (33.3%) | Somatosensory deficits, 7 (46.7%) | Temporal and spatial disorientation, 1 (6.7%) | CE, 8 (53.3%) | MT, 4 (26.6%) | |

| TIC, 6 (40.0%) | No, 4 (26.7%) | Aphasia, 10 (66.7%) | Cardiovascular alterations, 10 (66.7%) | UND, 5 (33.3%) | IVT + MT, 6 (40.0%) | |

| Left, 12 (80.0%) | Dysarthria, 4 (26.7%) | Headache, 1 (6.7%) | None, 3 (20.0%) | |||

| Right, 3 (20.0%) | Vestibular-like syndrome, 1 (6.7%) | |||||

Topography of lesion, clinical symptoms, stroke etiology, and reperfusion treatment.

AIC, anterior insular cortex; PIC, posterior insular cortex; TIC, total insular cortex; LVO, large vessel occlusion; M1, horizontal segment of middle cerebral artery; M2, sylvian segment of middle cerebral artery; M3, cortical segment of middle cerebral artery; CE, cardioembolic; LAD, large artery disease; UND, undetermined; IVT, intravenous thrombolysis; MT, mechanical thrombectomy.

3.5 Site and side of lesion

We found 12 patients with left IIS (80%) and only three patients with right IIS (20.0%). We detected 4/15 (26.6%) patients with anterior insular cortex lesion (AIC), 5/15 (33.3%) with posterior insular cortex lesion (PIC) and 6/15 (40%) with total insular cortex lesion (TIC). Eleven subjects (73.7%) had middle cerebral artery (MCA) involvement at CT angiography (CTA) (73.3%): 6/15 patients (%) had prevalent M1 segment occlusion, and 5/15 (33.3%) had prevalent M2 segment occlusion. The other four patients (26.6%) had no visible large vessel occlusion at CTA (Figures 3–5; Table 4).

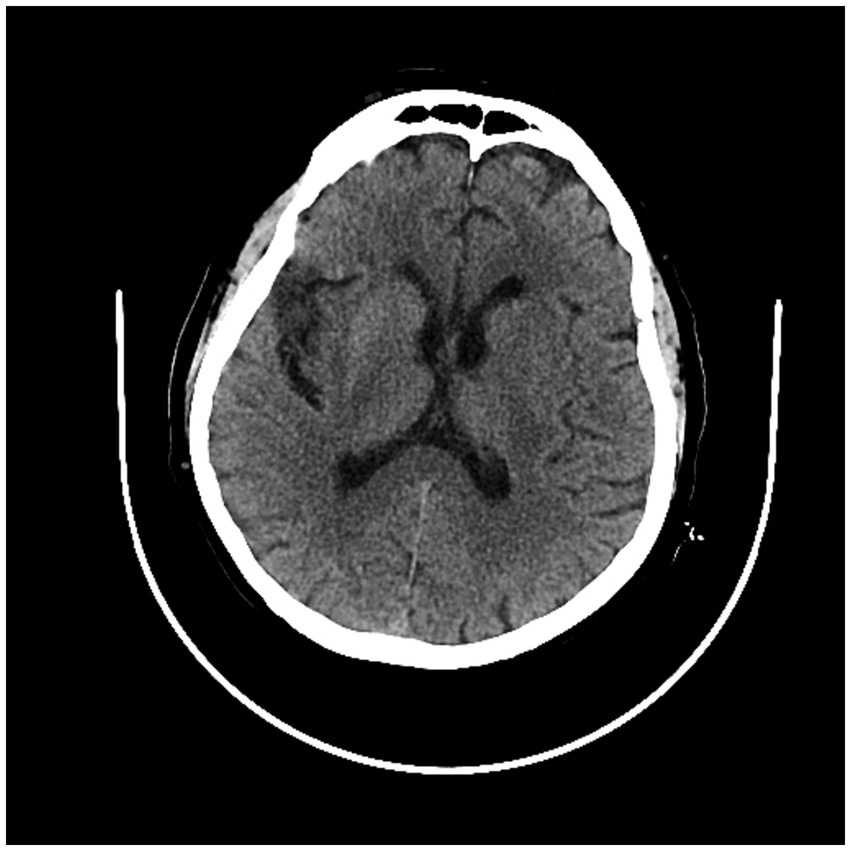

Figure 3

CT scan showing left posterior insular cortex (PIC) ischemic lesion.

Figure 4

Second CT scan showing left posterior cortex (PIC) ischemic lesion.

Figure 5

CT scan showing right total insular cortex (TIC) ischemic lesion.

3.6 Etiology

According to the TOAST classification (9), cardiac embolism was the most frequent etiology (8/15–53.3%); 2/15 patients had large artery disease (LAD) (13.3%), while five had a cryptogenic stroke (30.0%) (Table 4).

3.7 Reperfusion treatment

Two patients received only intravenous thrombolysis (2/15–13.3%) and four received only mechanical thrombectomy (4/15–27%). Six subjects received bridging therapy (rT-PA plus MT) (6/15–40%). The remaining patients did not meet the criteria for thrombolysis protocol, based on International Guidelines for reperfusion therapy (Table 4).

3.8 Outcome measures

The median NIHSS before reperfusion therapy was 11 (range 0–22) and the median NIHSS at discharge was 0 (range 0–22). Of note, five patients had persistent aphasic disorder at discharge (33.3%). The median delta NIHSS (defined as the difference between NIHSS before therapy and NIHSS at discharge) was 6. Most patients had major neurological improvement at discharge (defined as improvement of 8 points on the NIHSS from baseline or a NIHSS score of 0 or 1 at discharge) (13/15–86.7%).

The majority of patients did not have disability before the event, with median mRS score 0 (range 0–4). At discharge, median mRS score was 2 (range 0–4), while median 3-months mRS score was 0 (range 0–4). Good outcome (defined as 3-months mRS score of 0–2; for patients with pre-stroke mRS score > 2, return to the pre-stroke mRS three months after acute ischemic stroke-AIS-) was observed in most cases (mRS 0–2: 14/15–93.3%) (Table 5).

Table 5

| Patient ID | Outcome measures | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incoming NIHSS | NIHSS at discharge | Major neurological improvement | Language disorder at discharge | Pre-stroke mRS | mRS at discharge | 3-months mRS | Good outcome | |

| 1 | 16 | 3 | Yes | No | 2 | 4 | 3 | No |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | Yes | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | Yes |

| 3 | 18 | 0 | Yes | No | 0 | 2 | 0 | Yes |

| 4 | 2 | 1 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 4 | 3 | Yes |

| 5 | 9 | 5 | No | Yes | 0 | 2 | 1 | Yes |

| 6 | 22 | 0 | Yes | No | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes |

| 7 | 8 | 0 | Yes | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | Yes |

| 8 | 4 | 0 | Yes | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | Yes |

| 9 | 11 | 5 | No | Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | Yes |

| 10 | 17 | 3 | Yes | Yes | 0 | 4 | 0 | Yes |

| 11 | 22 | 22 | No | Yes | 4 | 4 | 4 | Yes |

| 12 | 6 | 0 | Yes | No | 0 | 3 | 1 | Yes |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | Yes | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | Yes |

| 14 | 12 | 0 | Yes | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | Yes |

| 15 | 12 | 3 | Yes | No | 0 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| Overall n (%) or median | 11 [0–22] | 0 [0–22] | Yes, 13 (86.7%) | Yes, 5 (33.3%) | 0 [0–4] | 2 [0–4] | 0 [0–4] | Yes, 14 (93.3%) |

| [IQR] or mean ± sd | No, 2 (13.3%) | No, 10 (66.7%) | No, 1 (6.7%) | |||||

Outcome measures.

86.7% of patients had major neurological improvement and 93.3% of patients had good outcome.

Major neurological improvement (improvement of 8 points on the NIHSS from baseline or a NIHSS score of 0 or 1 at discharge), good outcome (3-months mRS score of 0–2; for patients with pre-stroke mRS score > 2, return to the pre-stroke mRS 3 months after AIS).

4 Discussion

To our knowledge, the presented study is the largest monocentric case series of pure insular ischemic stroke. In fact, previously published case series by Lemieux et al. brilliantly presented a group of 23 patients of which 7 were recruited from their database and the remaining 16 were included from previously published cases, while Giammello et al. recently published an interesting single center-case series of 13 IIS focusing on their clinical presentation (9, 10).

Despite the increasing number of functional neuroimaging studies, the insular cortex wide array of functions remains a matter of interest and debate. In 2010, using the activation likelihood estimation (ALE) method, Kurth and al. tried to merge 13 insular cortex functional categories (i.e., emotion, empathy, olfaction, gustation, interoception, pain, somatosensation, motor, attention, language, speech, working memory and memory) into four functional domains, based on the connections with the adjacent brain structures: (1) a sensori-motor domain in the mid-posterior insula; (2) a social–emotional domain in the anterior-ventral insula; (3) a cognitive domain in the anterior-dorsal insula; (4) an olfactory-gustatory domain in the middle insular gyrus (2). It goes without saying that an isolated insular lesion, such as an ischemic stroke, could manifest with several different clinical presentations. Di Stefano et al. suggested to categorize symptoms in “typical” and “atypical,” according to the frequency of IIS case reports and case series clinical presentations (i.e., “typical” symptoms for motor and somatosensory deficits, dysarthria, aphasia, and vestibular-like syndrome; “atypical” symptoms for dysphagia, awareness deficits, gustatory disturbances, dysautonomia, neuropsychiatric or auditory disturbances and headache) (5). A combination of these symptoms-especially the typical ones-is common in the same patient. In our study, all the patients presented with typical symptoms, alone or in combination, with a predominance of language disorders (aphasia and dysarthria), while 11/15 patients presented with atypical symptoms, mainly represented by abnormal cardiac findings (10/11 patients). Precisely, AF was newly detected during the hospitalization in 4 patients, as well as ventricular extrasystoles (3/15), atrioventricular blocks (3/15), right bundle branch blocks (2/15), supraventricular extrasystoles (1/15), chaotic atrial rhythm (1/15), and left anterior fascicular block. Of note, none of these patients were under antiarrhythmic home therapy at the time of stroke onset. It is known the key role of the insula in regulating autonomic functions, such as heart rate, cardiac rhythm and blood pressure (11). Thus, it has been hypothesized that an ischemic insular lesion could imbalance the autonomic cardiac control, resulting in reduced parasympathetic tone and increased sympathetic tone, leading to catecholamine-related myocardial toxicity and manifesting with tachyarrhythmias, ventricular dysfunction, and myocardial infarction (11–13). Particularly, different studies identified an association between insular stroke and new-onset AF, supporting this neurogenic hypothesis, especially in the absence of a previous cardiac disease or abnormal cardiac imaging (14, 15). In our cohort, two out of four patients diagnosed with new-onset AF had a severe left atrial dilatation on echocardiogram, suggesting therefore a possible cardiogenic nature of AF rather than a neurogenic one. Nonetheless, clearly distinguishing between the two etiologies in the clinical setting remains challenging (14). As patients’ cardiac rhythm monitoring lasted meanly 48 h, we cannot exclude that a longer cardiac monitoring might have detected a higher percentage of arrythmias. Literature regarding long cardiac monitoring in insular stroke patients is unfortunately scarce, however a recent position paper written by AF-SCREEN International Collaboration proposed continuous ECG monitoring for at least 72 h after the index event in patients with TIA or ischemic stroke to detect AF. Concerning the other ECG abnormalities we found in our patients, Christensen et al. demonstrated that insular lesions are related to changes affecting RR interval, PR interval, ST segment, QTc and T-wave (16). Surprisingly, the mean values of RR interval and QTcB at the time of admission resulted within the normal ranges, although a heart rate variability analysis was not performed. Regarding IIS etiology, according to Stefano et al. review, embolic occlusion of M2 or its branches is the main cause of IIS (even though the origin of embolism is prevalently cryptogenic), while the most prevalent known etiology appears to be large-artery disease, followed by cardioembolism (CE) (5). In our case series, the most prevalent etiology resulted in CE (8/15). Indeed, a retrospective large study conducted by a Korean group in 2015 found that the frequency of CE was significantly higher than that in patients without insular involvement (17). Although the Korean study considered patients with ischemic lesions involving the insular cortex and not exclusively restricted to it, a full diagnostic work-up for the research of CE sources should be considered. In fact, if hyper-acute management of insular stroke does not differ from the management of other stroke localizations, nonetheless, after the acute phase, cardiac activity should be closely monitored. Conversely, as in these patients AF may not necessarily be the cause of stroke, but a consequence of acute brain injury, searching for laboratory (pro-BNP) and echocardiographic (left atrial dilation) signs of atrial cardiomyopathy may be useful to distinguish between the two conditions. Finally, it should be considered that in these patients new-onset AF could be a stroke consequence that resolves itself to stabilization of ischemia: thus, it may not deserve chronic anticoagulation.

Given the cardinal role of the insular cortex as a cerebral integration hub, the IIS outcome should be expected to be extremely unfavorable: conversely, most case report and case series patients had a general good recovery and low mRS (5, 9, 10). Our data confirm this trend as more than 80% of the patients had major neurological improvement at discharge (defined as improvement of 8 points on the NIHSS from baseline or a NIHSS score of 0 or 1 at discharge) and more than 90% of the patients had good outcome, defined as 3-months mRS score of 0–2 (for patients with pre-stroke mRS score > 2, return to the pre-stroke mRS three months after AIS), with median 3-months mRS score of 0 (range 0–4). Regarding NIHSS at discharge, it is interesting to point out that the highest scores might be linked to the persistence of an isolated aphasic disorder at discharge. Although there is limited evidence, due to the absence of long-term data on IIS follow-up and to its extreme low frequency, there are several possible reasons which could explain the general good outcome of IIS. First, as suggested by Lemieux et al. (9), the insula is by definition a restricted anatomic region of which the surrounding structures could compensate a limited damage, as demonstrated by tumor resection and epilepsy surgery studies (18, 19); second, as the insular cortex is predominantly vascularized by M2 segment of MCA and its divisions, with a small contribution by the insular branches of M1 segment and without the supply of pial collateral anterior and posterior circulation (20, 21), an IIS is an extremely rare occurrence while an insular cortex involvement in a MCA occlusion is very common and it is considered to be a marker of negative outcome and large infarct stroke (3, 22, 23). Thus, it has been hypothesized that most of the clinical deficits are due to an hypoperfusion of the MCA territory, which might be reversible after MCA recanalization (3, 24, 25). In our case series, of 11 patients with evidence of LVO (M1 or M2), 10 had received MT and 10/11 showed 3-months good outcome. In addition, the possible presence of anatomical variants leading to insular poor vascularization has not been yet considered or deepened in previous studies, nor the presence of anatomical variants have emerged in our patients’ CT angiographies.

The present study has several limitations. First, the retrospective nature of the study could have biased the data collection and the results; second, a complete heart rate variability analysis could have added information on cardiological aspects linked to a possible shift in balance toward an augmented sympathetic tone (11); third, there are no follow-up data concerning ECGs and echocardiograms of our patients, which could have supported the neurogenic hypothesis in the genesis of new-onset arrythmias.

5 Conclusion

IIS are extremely rare, representing according to our study about 2.6% ischemic strokes cases per year, and patients have peculiar clinical manifestations, such as dysautonomia and awareness deficits. Our data suggest the possibility for these patients to completely recover after AIS, as more than 80% of our patients had major neurological improvement at discharge and more than 90% had low mRS at three months after the event, notwithstanding the pivotal role of the insula in cerebral connections and the frequent association with MCA occlusion. Moreover, given the central role of the insula in regulating autonomic functions, cardiac alterations must be taken into consideration, as well as a full diagnostic work-up for the research of cardioembolic sources should be mandatory. Prospective studies are needed to better define these aspects. To our knowledge, the presented study is the largest monocentric case series of pure insular stroke and it might be useful for future systematic reviews.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Comitato Etico Unico Regionale Fvg (CEUR) Palazzina C, Piano Terra, Via Pozzuolo 330, Udine Ref. No. CEUR-2020-Os-173. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

FK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ST: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing. RS: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. LC: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. DB: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. GM: Validation, Writing – review & editing. FJ: Writing – review & editing. CG: Writing – review & editing. RM: Writing – review & editing. LV: Writing – review & editing. MV: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. GP: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Gogolla N . The insular cortex. Curr Biol. (2017) 27:R580–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.010

2.

Kurth F Zilles K Fox PT Laird AR Eickhoff SB . A link between the systems: functional differentiation and integration within the human insula revealed by meta-analysis. Brain Struct Funct. (2010) 214:519–34. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0255-z

3.

Kodumuri N Sebastian R Davis C Posner J Kim EH Tippett DC et al . The association of insular stroke with lesion volume. Neuroimage Clin. (2016) 11:41–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.01.007

4.

Kobari M Meyer JS Lchijo M Oravez WT . Leukoaraiosis: correlation of MR and CT findings with blood flow, atrophy, and cognition. Am J Neuroradiol. (1990) 11:273–81.

5.

Di Stefano V De Angelis MV Montemitro C Russo M Carrarini C di Giannantonio M et al . Clinical presentation of strokes confined to the insula: a systematic review of literature. Neuro Sci. (2023) 44:785. doi: 10.1007/s10072-022-06418-9

6.

Adams HP Jr Bendixen BH Kappelle LJ Biller J Love BB Gordon DL et al . Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. (1993) 24:35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35

7.

Sue-Min Lai PWD . Stroke recovery profile and the modified Rankin assessment. Neuroepidemiology. (2001) 20:26–30. doi: 10.1159/000054754

8.

Weisscher N Vermeulen M Roos YB De Haan RJ . What should be defined as good outcome in stroke trials; a modified Rankin score of 0-1 or 0-2?J Neurol. (2008) 255:867–74. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0796-8

9.

Lemieux F Lanthier S Chevrier MC Gioia L Rouleau I Cereda C et al . Insular ischemic stroke: clinical presentation and outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. (2012) 2:80–7. doi: 10.1159/000343177

10.

Giammello F Cosenza D Casella C Granata F Dell’Aera C Fazio MC et al . Isolated insular stroke: clinical presentation. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2020) 49:10–8. doi: 10.1159/000504777

11.

Oppenheimer S Cechetto D . The insular cortex and the regulation of cardiac function. Compr Physiol. (2016) 6:1081–33. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140076

12.

Winder K Villegas Millar C Siedler G Knott M Dörfler A Engel A et al . Acute right insular ischaemic lesions and poststroke left ventricular dysfunction. Stroke Vasc Neurol. (2023) 8:301–6. doi: 10.1136/svn-2022-001724

13.

Scheitz JF Erdur H Haeusler KG Audebert HJ Roser M Laufs U et al . Insular cortex lesions, cardiac troponin, and detection of previously unknown atrial fibrillation in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. (2015) 46:1196–01. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008681

14.

Min J Young G Umar A Kampfschulte A Ahrar A Miller M et al . Neurogenic cardiac outcome in patients after acute ischemic stroke: the brain and heart connection. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2022) 31:106859. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2022.106859

15.

González Toledo ME Klein FR Riccio PM Cassará FP Muñoz Giacomelli F Racosta JM et al . Atrial fibrillation detected after acute ischemic stroke: evidence supporting the neurogenic hypothesis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2013) 22:e486–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.05.015

16.

Christensen H Boysen G Christensen AF Johannesen HH . Insular lesions, ECG abnormalities, and in outcome in acute stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2005) 76:269–71. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.037531

17.

Kang J Hong JH Jang MU Kim BJ Bae HJ Han MK . Cardioembolism and involvement of the insular cortex in patients with ischemic stroke. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0139540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139540

18.

Penfield W Faulk ME Jr . The insula: further observations on its function. Brain. (1955) 78:445–70. doi: 10.1093/brain/78.4.445

19.

Duffau H Taillandier L Gatignol P Capelle L . The insular lobe and brain plasticity: lessons from tumor surgery. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2006) 108:543–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.09.004

20.

Türe U Gazi M Al-mefty OH Yas DC . Arteries of the insula. J Neurosurg. (2000) 92:676–87. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.4.0676

21.

Raghu ALB Parker T Van Wyk A Green AL . Insula stroke: the weird and the worrisome. Postgrad Med J. (2019) 95:497–04. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2019-136732

22.

Min SH Kim JT Kang KW Choi MJ Yoon H Shinohara Y et al . Acute insular infarction: early outcomes of minor stroke with proximal artery occlusion. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0229836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229836

23.

Fink JN Selim MH Kumar S . et al, Insular cortex infarction in acute middle cerebral artery territory stroke predictor of stroke severity and vascular lesion. Arch Neurol. (2005) 62:1081. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.7.1081

24.

Humpich M Singer OC De Rochemont RDM Foerch C Lanfermann H Neumann-Haefelin T . Effect of early and delayed recanalization on infarct pattern in proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2006) 22:51–6. doi: 10.1159/000092338

25.

Mejdoubi M Calviere L Boot B . Isolated insular infarction following successful intravenous thrombolysis of middle cerebral artery strokes. Eur Neurol. (2009) 61:308–10. doi: 10.1159/000206857

Summary

Keywords

insular stroke, acute ischemic stroke, case series, good outcome, cardioembolism

Citation

Kuris F, Tartaglia S, Sperotto R, Ceccarelli L, Bagatto D, Lorenzut S, Merlino G, Janes F, Gentile C, Marinig R, Verriello L, Valente M and Pauletto G (2024) Isolated insular stroke: topography is the answer with respect to outcome and cardiac involvement. Front. Neurol. 15:1332382. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1332382

Received

02 November 2023

Accepted

19 February 2024

Published

29 February 2024

Volume

15 - 2024

Edited by

Jean-Claude Baron, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Raffaele Ornello, University of L'Aquila, Italy

Kiruba Nagaratnam, Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Kuris, Tartaglia, Sperotto, Ceccarelli, Bagatto, Lorenzut, Merlino, Janes, Gentile, Marinig, Verriello, Valente and Pauletto.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fedra Kuris, kuris.fedra@gmail.comGiada Pauletto, giada.pauletto@asufc.sanita.fvg.it

†These authors share senior and last authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.