Abstract

Objectives:

This study aims to present the first comprehensive meta-analysis assessing the effectiveness and safety of drug-eluting stents (DES) versus bare-metal stents (BMS) in treating intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis.

Methods:

A comprehensive examination was undertaken to compare the effectiveness and safety of DES and BMS in individuals experiencing symptomatic stenosis in the intracranial and vertebral arteries through an in-depth analysis of clinical research. We conducted an extensive search across multiple databases including PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library up to September 2024. The emphasis of our investigation was on various outcomes including rates of in-stent restenosis, symptomatic occurrences of in-stent restenosis, incidence of stroke, procedural success, mortality rates, complications associated with the procedure, and any adverse events.

Results:

Our analysis included 12 studies with a total of 1,243 patients (562 in the DES group and 681 in the BMS group). The findings demonstrated a significantly lower rate of in-stent restenosis in the DES group for both intracranial [odds ratio (OR): 0.23; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.13 to 0.41; p < 0.00001] and vertebral artery stenosis (OR: 0.38; 95% CI: 0.20 to 0.72; p = 0.003) compared to the BMS group. Additionally, the DES group showed a significantly reduced rate of postoperative strokes in vertebral artery stenosis cases (OR: 0.38; 95% CI: 0.16 to 0.90; p = 0.03), with no significant differences noted in the intracranial artery stenosis comparison (OR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.20 to 1.95; p = 0.42). The study also revealed no significant disparities in symptomatic in-stent restenosis, procedural success, mortality, adverse effects, and perioperative complications between the two groups across the conditions studied.

Conclusion:

The comparison indicates that DES significantly reduces the risk of in-stent restenosis and postoperative strokes in patients with vertebral artery stenosis, compared to BMS. For both intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis, DES and BMS exhibit comparable safety profiles.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=439967.

1 Introduction

Strokes’ prevalence globally is significantly impacted by intracranial artery stenosis, with 8 to 10% of strokes in North America and a substantial 30 to 50% in Asia being attributed to it (1–5). Responsible for 15 to 20% of posterior circulation strokes is vertebral artery stenosis (6, 7). Not only does this condition impede cerebral blood flow, leading to cerebral hypoperfusion, but it also serves as a potential source of arterial embolisms. Evidence from several studies suggests a link between vertebral artery stenosis and an increased likelihood of recurrent strokes (6, 8–10). Aggressive medical management is recommended as the cornerstone of stroke prevention for patients with intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis according to current guidelines (11). In substantially reducing the recurrence of strokes in these patients, this approach has been effective (2, 12, 13). Despite aggressive medical therapy, some patients still face a high risk of stroke recurrence (14, 15). When aggressive medical therapy fails, surgery and endovascular therapy become reasonable options. Due to the unique location of the vertebral and intracranial arteries, surgical revascularization is often challenging, with relevant perioperative complications and mortality related (16, 17).

Intravascular stents coated with anti-vascular endotheliocytes proliferation drugs on the surface or inside are known as drug-eluting stents (DES) (18). The sustained release of drugs on the surface of DES, compared with bare metal stents (BMS), can restrict the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells in the stent, thereby restraining intravascular thrombosis and preventing in-stent restenosis. Mainly applied currently is DES to treat symptomatic stenosis in intracranial and vertebral arteries. Wu et al. (19) reported in a meta-analysis that drug-coated balloon angioplasty is a safe and effective method for the treatment of vertebral artery stenosis. Additionally, clinical studies have found that DES have a lower rate of restenosis for the treatment of intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis compared to BMS (18, 20–23). At present, the superiority of DES over BMS remains inconclusive due to factors such as the small sample size, short follow-up time, and variations in arterial stenosis sites. The first meta-analysis comparing the efficacy and safety of DES and BMS for intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis was reported.

2 Methods

2.1 Literature search

According to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) 2020 statement (24) and has been prospectively registered in the PROSPERO (CRD42023439967). Until September 2024, we meticulously searched through PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane databases to identify clinical studies comparing the efficacy and safety of DES with BMS in individuals suffering from symptomatic stenosis in intracranial and vertebral arteries. Through the following terms, we searched the literature extensively: “drug-eluting stents,” “bare-metal stent,” “intracranial,” “vertebral,” and “stenosis.” The detailed search strategies are as follows: (((“Drug-Eluting Stents”[Mesh]) OR (((((((((((((Drug Eluting Stents) OR (Stents, Drug-Eluting)) OR (Stents, Drug Eluting)) OR (Drug-Eluting Stent)) OR (Drug Eluting Stent)) OR (Stent, Drug-Eluting)) OR (Drug-Coated Stents)) OR (Drug Coated Stents)) OR (Stents, Drug-Coated)) OR (Stents, Drug Coated)) OR (Drug-Coated Stent)) OR (Drug Coated Stent)) OR (Stent, Drug-Coated))) AND ((bare-metal stent) OR (bare metal stent))) AND (((intracranial) OR (vertebral)) AND (stenosis)). Furthermore, we manually screened the bibliography lists of all included RCTs. Two authors independently gathered eligible articles and evaluated them. Any discrepancies in literature retrieval were resolved through discussion.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible articles had to meet the following criteria:

P: patients diagnosed with symptomatic intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis.

I: DES.

C: BMS.

O: at least one outcome (such as in-stent restenosis, symptomatic in-stent restenosis, stroke, technical success, mortality, periprocedural complications, and adverse events) was measured; (5) data were available to analyze either odds ratios (OR) or weighted mean differences (WMD).

S: randomized controlled trial (RCT), cohort study, or case-control study.

Exclusions were made for study protocols, unpublished research, non-original studies (including letters, comments, abstracts, corrections, and replies), studies lacking adequate data, and review articles.

2.3 Data abstraction

Two authors independently conducted data abstraction, with any discrepancies resolved by a third author. We abstracted following information from eligible studies: first author name, published year, research period, study region, study design, intervention/exposure, control/non-exposure, sample size, age, gender, follow-up time, body mass index (BMI), comorbidity, stent length, in-stent restenosis, symptomatic in-stent restenosis, stroke, technical success, mortality, periprocedural complications, and adverse events. If the continuous data in the article was presented as median plus range or median plus interquartile range (IQR), we reanalysed the mean ± standard deviation (SD) via the methods reported by Wan et al. (25) and Luo et al. (26). Corresponding authors were contacted for full data if available, in cases where the research data is insufficient.

2.4 Quality evaluation

For evaluating the quality of eligible cohort studies, the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was utilized (27), with high quality being attributed to studies scoring 7–9 points (28). The quality assessment of eligible RCTs was conducted following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0 based on seven terms: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias (29). Every study aspect was assigned one of three evaluation outcomes: low risk, high risk, or unclear risk. Higher quality was attributed to studies with more evaluations indicating “low risk” bias. The quality of all included studies was independently assessed by two authors, with any disagreements settled through discussion.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The analysis utilized Review Manager 5.4.1 edition. Continuous data were synthesized using the WMD, while dichotomous data synthesis employed OR. Each metric was accompanied by 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To evaluate the heterogeneity of each outcome, the Cochran’s Q test (chi-squared test, χ2) and the inconsistency index (I2) were applied (30). χ2p-value less than 0.1 or I2 more than 50% were regarded as high heterogeneity. The total WMD or OR for outcomes with significant heterogeneity (χ2p-value less than 0.1 or I2 more than 50%) was calculated using the random-effects model. Otherwise, the fixed-effects model was applied. Additionally, subgroup analyses were conducted for outcomes with two or more included studies to evaluate possible confounders, if data were sufficient. Furthermore, we performed sensitivity analyses to evaluate the impact of each individual study on the overall WMD or OR when there were more than two studies included. Additionally, potential publication bias was assessed by generating funnel plots using Review Manager 5.4.1 and conducting Egger’s regression tests using Stata 15.1 edition (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, United States) for outcomes involving more than two studies. A p-value less than 0.05 was deemed indicative of statistically significant publication bias.

3 Results

3.1 Literature retrieval, study characteristics, and baseline

The flowchart of the literature retrieval and selection process is illustrated in Figure 1. Through systematic literature searches, a total of 178 related studies were identified in PubMed (n = 39), Embase (n = 75), Web of Science (n = 55), and Cochrane (n = 9). The detailed search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table S1. After the elimination of duplicate studies, 105 titles and abstracts underwent evaluation. Eventually, a meta-analysis was conducted, encompassing 12 studies and involving 1,243 patients (562 in the DES group versus 681 in the BMS group) (18, 20–23, 31–38). Presented in Table 1 are the characteristics and quality assessment of each eligible study. The details of quality evaluation for all included RCTs are shown in Figure 2, and Supplementary Table S2 displays the details of quality evaluation for all included cohorts. For intracranial artery stenosis, the two groups were comparable in age (WMD: 0.67; 95% CI: −1.04, 2.38; p = 0.44), gender (male) (OR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.65, 1.57; p = 0.96), proportion of hypertension (OR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.39, 1.41; p = 0.36), and proportion of coronary artery disease (OR: 1.03; 95% CI: 0.60, 1.77; p = 0.92) (Table 2). For cases of vertebral artery stenosis, both groups showed similar distributions in terms of gender (male) (OR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.66, 1.26; p = 0.59), prevalence of hypertension (OR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.36, 1.67; p = 0.51), prevalence of diabetes mellitus (OR: 1.05; 95% CI: 0.79, 1.40; p = 0.74), prevalence of coronary artery disease (OR: 1.30; 95% CI: 0.98, 1.74; p = 0.07), stent length (WMD: −0.25; 95% CI: −0.57, 0.08; p = 0.14), and BMI (WMD: −0.04; 95% CI: −1.14, 1.06; p = 0.94). The age of the DES group, however, was significantly lower than that of the BMS group (WMD: −1.29; 95% CI: −2.50, −0.09; p = 0.04) (Table 3).

Figure 1

Flowchart of the systematic search and selection process.

Table 1

| Authors | Study period | Country | Study design | Location of stenosis | Intervention/exposure | Control/non-exposure | Stent implantation device | Preprocedural medical management | Post-procedure medical treatments | Patients (n) | Follow-up (mean/median) | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DES/BMS | ||||||||||||

| Akins 2008 | 1999–2005 | USA | Prospective cohort | Vertebral artery | Tacrolimus-eluting stents | Bare-metal stents | NA | Antiplatelet regimen | Aspirin (325 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day) were prescribed for 6 months following the procedure, with either aspirin or clopidogrel indefinitely thereafter | 5/7 | 30 months | 6 |

| Che 2018 | 2010–2016 | China | Retrospective cohort | Vertebral artery | Drug eluting stent | Balloon-expandable bare-metal stent | 6F or 8F guiding catheter (Mach 1; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Mass) | Aspirin (100 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day) for at least 2 days | Dual antiplatelet therapy | 147/165 | 2.9 years | 8 |

| He 2019 | 2014–2015 | China | RCT | Vertebral artery | Drug-eluting stent (Maurora stent) | Bare-metal stent (Apollo stent) | NA | NA | NA | 20/20 | 18 months | — |

| Jia 2022 | 2015–2018 | China | RCT | Intracranial arterial stenosis | Drug-eluting stent (NOVA intracranial sirolimus eluting stent system; SINOMED) | Bare-metal stent (Apollo intracranial stent system; MicroPort NeuroTech) | NA | Oral aspirin, 100 mg, daily and clopidogrel bisulfate, 75 mg, daily for at least 5 days before the procedure or a 300 mg loading dose of clopidogrel and a 100- to 300 mg loading dose of aspirin between 6 and 24 h before the procedure | Aspirin, 100 mg, daily and clopidogrel, 75 mg, daily for 90 days before converting to aspirin or clopidogrel alone | 132/131 | 1 year | — |

| Langwieser 2014 | 1997–2012 | Germany | Retrospective cohort | Vertebral artery | Balloon-expandable drug-eluting | Bare-metal stent (self-expanding and balloon-expandable) | An appropriate-shaped 6- or 7-French guiding catheter. The lesion was crossed with a 0.014-inch guide wire | Acetyl-salicylic acid (100–300 mg/day) and one additional platelet inhibitor including ticlopidin (500 mg TID as loading dose followed by 250 mg bid), clopidogrel (600 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg/day) | Thienopyridines were prescribed for at least 4 weeks or 6 months after bare-metal stent or drug-eluting stent implantation, respectively, whereas acetyl-salicylic acid was recommended as a life-long therapy | 16/24 | 18 months | 6 |

| Lee 2013 | 2007–2012 | Korea | Retrospective cohort | Intracranial arterial stenosis | Drug-eluting stent | Bare-metal stent | A 6 or 7 French guiding catheter was inserted into the proximal internal cerebral artery (ICA) after a femoral puncture. A 0.014 inch (0.35 mm) wire was then introduced through the guiding catheter with or without use of a microcatheter | All patients undergoing stent-angioplasty were given dual antiplatelet therapy for at least three days before the procedure, which consisted of aspirin (100 mg–300 mg/day orally) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day orally) | Dual antiplatelet therapy was continued after the procedure and then switched to monotherapy after at least 12 weeks (aspirin 100 mg/day orally) | 7/24 | 40.7 months | 7 |

| Li 2020 | 2014–2015 | China | Prospective cohort | Vertebral artery | Drug-eluting stent [Xience V (Abbott, United States), Endeavor (Medtronic, Ireland) and Firebird (MicroPort Medical, China)] | Bare-metal stent [Blue (Cordis Corp, Netherlands) and Express (Boston Scientific, United States)] | A 6-F guiding catheter was advanced into the subclavian artery proximal to the VAO with a 0.035-inch micro guidewire and the lesion was crossed with a 0.014-inch micro guidewire | Aspirin (100 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day) were prescribed for all patients at least 5 days prior to the procedure | Double antiplatelet regimen (aspirin 100 mg daily, clopidogrel 75 mg daily) for 12 months and 3 months respectively, followed by aspirin monotherapy indefinitely | 76/74 | 12.3 months | 9 |

| Maciejewski 2019 | 2003–2016 | Poland | Prospective cohort | Vertebral artery | Drug-eluting stent | Bare-metal stent | Over a 0.035-inch diagnostic wire a 6 Fr guiding catheter was advanced toward the VA ostium. Then the lesion was crossed with a 0.014 inch coronary guide wire | One day before the procedure, patients received a 300 mg loading dose of clopidogrel | Patients were on aspirin 75 mg o.d., which was continued indefinitely afterwards | 144/270 | 45.4 months | 8 |

| Raghuram 2012 | — | USA | Retrospective cohort | Vertebral artery | Drug-eluting stent | Bare-metal stent | NA | 3–5 days of dual antiplatelet preparation with aspirin and clopidogrel | NA | 13/15 | 26 months | 7 |

| Si 2022 | 2014–2015 | China | RCT | Intracranial arterial stenosis | Drug-eluting stent [Apollo stent (MicroPort Medical, Shanghai, China)] | Bare-metal stent [Maurora stent (Alain Medical, Beijing, China)] | A 0.014-inch micro guide wire was selected to pass through the stenosis through the guide tube | Clopidogrel 75 mg and aspirin 300 mg were started 3–5 days before the operation | Aspirin 100–300 mg/day and clopidogrel 75 mg/day were taken orally until 3 months after the operation; clopidogrel was stopped after 3 months; and aspirin was reduced to 100 mg/day for long-term use | 92/96 | 1 year | — |

| Song 2012 | 2003–2010 | China | Prospective cohort | Vertebral artery | Drug-eluting stent sirolimus-eluting stents [39 Cypher (Cordis Corporation, Bridgewater, NJ, United States) and 34 Firebird (MicroPort Medical, Shanghai, China)] or paclitaxel-eluting stents [52 Taxus (Boston Scientific Corporation, Natick, MA, United States)] | Bare-metal stent [balloon-expandable stents (63 stainless steel and 38 cobalt chromium)] | Lesions were crossed with a 0.014-inch microwire and microcatheter | Aspirin (300 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day) at least 3 days before the treatment | Aspirin (100 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day) for 12 months; after that, aspirin (100 mg/day) alone was continued indefinitely | 112/94 | 43 months | 9 |

| Wang 2022 | 2018–2021 | China | Retrospective cohort | Vertebral artery | Drug-eluting stent (XIENCE, Abbott, Temecula, California, United States) | Bare-metal stent (Apollo; MicroPort, Shanghai, China) | An 8F or 6F sheath was placed in the femoral artery. An 8F or 6F guide catheter was advanced to the subclavian artery proximal to the VAO. | Dual antiplatelet therapy consisting of aspirin (100 mg, daily), cilostazol (100 mg twice daily), and clopidogrel (75 mg, daily) or ticagrelor (90 mg, twice daily) | Dual antiplatelet therapy regimen was continued for 3 months in patients receiving stenting with BMS or angioplasty with DCB, and for 12 months in those receiving DES implantation. Antiplatelet monotherapy was used indefinitely | 29/12 | 14.1 months | 7 |

Baseline characteristics of include studies and methodological assessment.

DES, drug-eluting stent; BMS, bare metal stent.

Figure 2

Details of the quality evaluation for included RCTs.

Table 2

| Outcomes | Studies | No. of patients | WMD or OR | 95% CI | p-value | Heterogeneity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DES/BMS | Chi2 | df | p-value | I 2 (%) | |||||

| Age (years) | 3 | 231/251 | 0.67 | [−1.04, 2.38] | 0.44 | 0.30 | 2 | 0.86 | 0 |

| Gender (male) | 2 | 224/227 | 1.01 | [0.65, 1.57] | 0.96 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.83 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 2 | 224/227 | 0.74 | [0.39, 1.41] | 0.36 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.13 | 55 |

| Coronary artery disease | 2 | 224/227 | 1.03 | [0.60, 1.77] | 0.92 | 1.51 | 1 | 0.22 | 34 |

Demographics and clinical characteristics of included studies for intracranial artery stenosis.

DES, drug-eluting stent; BMS, bare metal stent; WMD, weighted mean difference; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 3

| Outcomes | Studies | No. of patients | WMD or OR | 95% CI | p-value | Heterogeneity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DES/BMS | Chi2 | df | p-value | I 2 (%) | |||||

| Age (years) | 6 | 394/485 | −1.29 | [−2.05, −0.09] | 0.04a | 8.89 | 5 | 0.11 | 44 |

| Gender (male) | 6 | 394/485 | 0.92 | [0.66, 1.26] | 0.59 | 2.67 | 5 | 0.75 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 7 | 399/492 | 0.77 | [0.36, 1.67] | 0.51 | 12.88 | 6 | 0.04 | 53 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 | 399/492 | 1.05 | [0.79, 1.40] | 0.74 | 5.81 | 6 | 0.44 | 0 |

| Coronary artery disease | 6 | 386/477 | 1.30 | [0.98, 1.74] | 0.07 | 2.66 | 5 | 0.75 | 0 |

| Stent length | 3 | 276/384 | −0.25 | [−0.57, 0.08] | 0.14 | 1.17 | 2 | 0.56 | 0 |

| BMI | 2 | 49/32 | −0.04 | [−1.14, 1.06] | 0.94 | 1.96 | 1 | 0.16 | 49 |

Demographics and clinical characteristics of included studies for vertebral artery stenosis.

BMI, body mass index; DES, drug-eluting stent; BMS, bare metal stent; WMD, weighted mean difference; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Statistically significant.

3.2 In-stent restenosis

Intracranial artery stenosis, in-stent restenosis results were synthesized from 3 studies, including 375 patients (181 DES versus 194 BMS) (18, 21, 34). A significant lower in-stent restenosis rate in the DES group was revealed by meta-analysis (OR: 0.23; 95% CI: 0.13, 0.41; p < 0.00001), without significant heterogeneity observed (I2 = 0%, p = 0.98) (Figure 3A). Subgroup analysis unveiled that significance endured in prospective studies and those with a follow-up period of less than 24 months, yet dissipated in retrospective studies and those spanning 24 months or more in duration (Table 4).

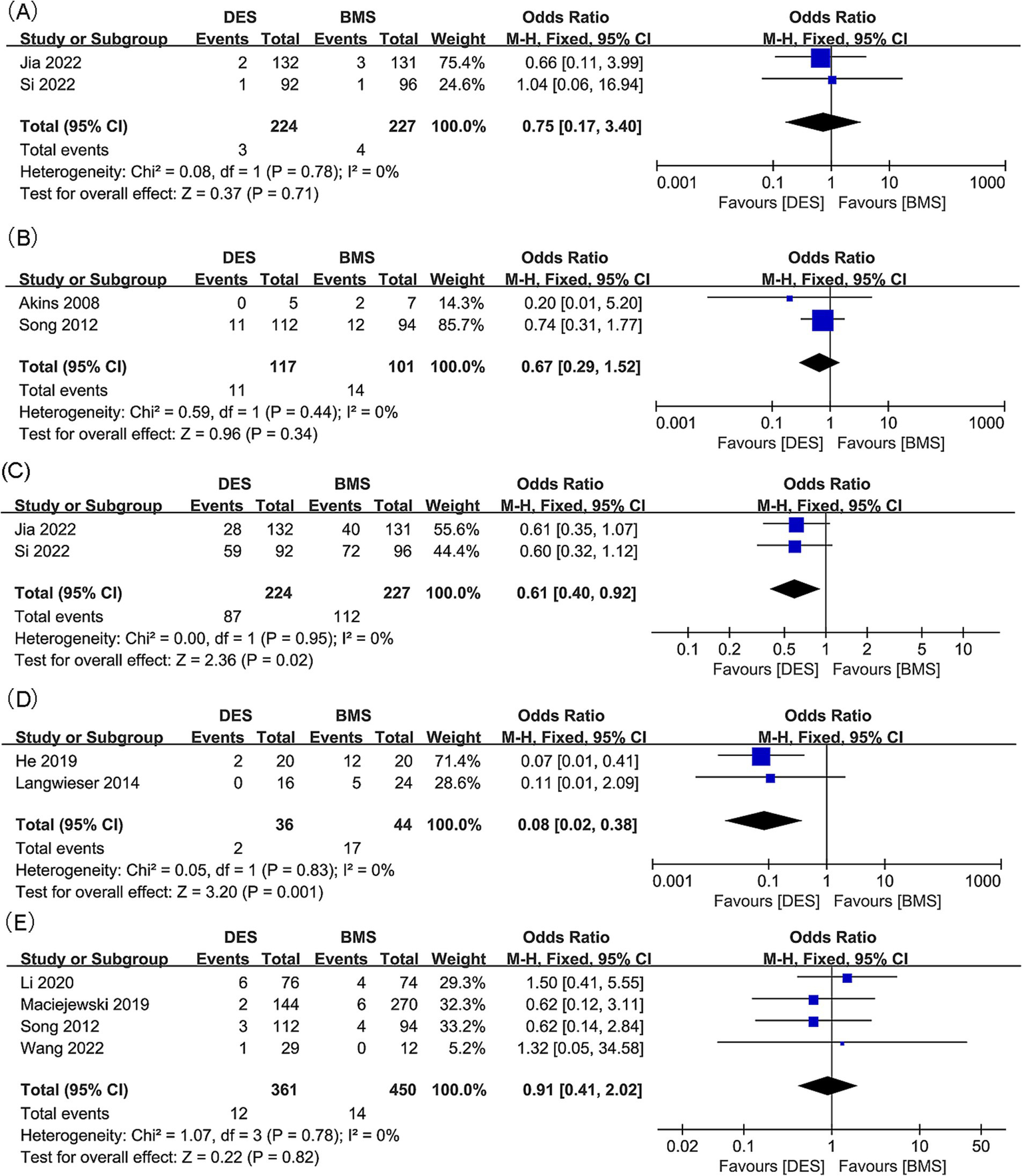

Figure 3

Forest plots of (A) in-stent restenosis (intracranial artery stenosis), (B) in-stent restenosis (vertebral artery stenosis), and (C) symptomatic in-stent restenosis (vertebral artery stenosis).

Table 4

| Subgroup | In-stent restenosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | OR [95% CI] | p-value | I 2 | |

| Total | 3 | 0.23 [0.13, 0.41] | <0.00001 | 0% |

| Study design | ||||

| Prospective | 2 | 0.23 [0.13, 0.41] | <0.00001 | 0% |

| Retrospective | 1 | 0.24 [0.01, 4.82] | 0.35 | NA |

| Follow-up | ||||

| ≥24 months | 1 | 0.24 [0.01, 4.82] | 0.35 | NA |

| <24 months | 2 | 0.23 [0.13, 0.41] | <0.00001 | 0% |

Subgroup analysis of DES versus BMS for intracranial arterial stenosis.

DES, drug-eluting stent; BMS, bare metal stent; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Findings regarding in-stent restenosis for vertebral artery stenosis were synthesized from 9 studies, which included 1,263 patients (575 DES versus 688 BMS) (20, 22, 23, 31–33, 35–37). A significant reduction in the rate of in-stent restenosis within the DES group was revealed by the meta-analysis (OR: 0.38; 95% CI: 0.20, 0.72; p = 0.003), along with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 63%, p = 0.006) (Figure 3B). Significance persisted in prospective studies, retrospective studies, and studies with a follow-up period <24 months, as well as in Asian studies according to subgroup analysis. However, it disappeared in studies with a follow-up period ≥24 months, as well as in European and American studies (Table 5).

Table 5

| Subgroup | In-stent restenosis | Stroke | Periprocedural complications | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | OR [95% CI] | p-value | I 2 | Study | OR [95% CI] | p-value | I 2 | Study | OR [95% CI] | p-value | I 2 | |

| Total | 9 | 0.38 [0.20, 0.72] | 0.003 | 63% | 4 | 0.38 [0.16, 0.90] | 0.03 | 0% | 4 | 0.91 [0.41, 2.02] | 0.82 | 0% |

| Study design | ||||||||||||

| Prospective | 5 | 0.46 [0.21, 1.01] | 0.05 | 64% | 3 | 0.39 [0.15, 0.97] | 0.04 | 0% | 3 | 0.89 [0.39, 2.03] | 0.78 | 0% |

| Retrospective | 4 | 0.28 [0.09, 0.86] | 0.03 | 51% | 1 | 0.37 [0.05, 2.99] | 0.35 | NA | 1 | 1.32 [0.05, 34.58] | 0.87 | NA |

| Follow-up | ||||||||||||

| ≥24 months | 5 | 0.51 [0.23, 1.15] | 0.1 | 69% | 2 | 0.42 [0.16, 1.12] | 0.08 | 0% | 2 | 0.62 [0.20, 1.88] | 0.4 | 0% |

| <24 months | 4 | 0.21 [0.07, 0.64] | 0.007 | 43% | 2 | 0.28 [0.05, 1.53] | 0.14 | 0% | 2 | 1.47 [0.44, 4.97] | 0.53 | 0% |

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Asia | 5 | 0.32 [0.20, 0.51] | <0.00001 | 10% | 3 | 0.35 [0.13, 0.96] | 0.04 | 0% | 3 | 1.05 [0.41, 2.68] | 0.91 | 0% |

| Europe | 2 | 0.41 [0.03, 5.70] | 0.51 | 70% | 1 | 0.46 [0.10, 2.20] | 0.33 | NA | 1 | 0.62 [0.12, 3.11] | 0.56 | NA |

| America | 2 | 0.57 [0.06, 5.04] | 0.61 | 40% | ||||||||

Subgroup analysis of DES versus BMS for vertebral arterial stenosis.

DES, drug-eluting stent; BMS, bare metal stent; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

3.3 Symptomatic in-stent restenosis

Two studies, including 81 patients (49 with DES and 32 with BMS), were conducted to synthesize data on symptomatic in-stent restenosis for vertebral artery stenosis (20, 32). No statistically significant difference was detected in the rate of symptomatic in-stent restenosis between the DES and BMS groups (OR: 0.12; 95% CI: 0.01, 1.06; p = 0.06), with no notable heterogeneity observed (I2 = 0%, p = 0.68) (Figure 3C).

3.4 Technical success

Results of technical success for intracranial artery stenosis were synthesized from two studies, which included 429 patients (214 treated with DES and 215 with BMS) (18, 21). No significant difference was found between the DES and BMS group for technical success rate, with an odds ratio of 1.56 (95% CI: 0.62, 3.91; p = 0.34). Additionally, no significant heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 12%, p = 0.29) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4

Forest plots of (A) technical success (intracranial artery stenosis), (B) technical success (vertebral artery stenosis), (C) postoperative stroke (intracranial artery stenosis), and (D) postoperative stroke (vertebral artery stenosis).

Technical success outcomes for vertebral artery stenosis were synthesized from three studies, with 259 patients included (146 DES versus 113 BMS) (20, 23, 31). No significant difference was found between the DES and BMS groups for technical success rate (OR: 0.66; 95% CI: 0.16, 2.69; p = 0.56), and no significant heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 0%, p = 0.38) (Figure 4B).

3.5 Postoperative stroke

Postoperative stroke outcomes for intracranial artery stenosis were collated from two studies, which included 451 patients (224 treated with DES versus 227 with BMS) (18, 21). There was no significant difference observed in the postoperative stroke rates between the DES and BMS groups (OR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.20, 1.95; p = 0.42). Additionally, no significant heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 0%, p = 0.45) (Figure 4C).

No significant difference was found between the DES and BMS groups for postoperative stroke rate, with no significant heterogeneity observed (OR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.20, 1.95; p = 0.42; I2 = 0%, p = 0.45) (20, 23, 32, 36). In the DES group, meta-analysis revealed a significant lower postoperative stroke rate (OR: 0.38; 95% CI: 0.16, 0.90; p = 0.03) without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, p = 0.96) (Figure 4D). Subgroup analysis revealed that significance persisted in prospective and Asian studies, while it diminished in retrospective studies, as well as studies with follow-up periods of both less than 24 months and 24 months or more. Additionally, the significance was absent in European and American studies (Table 5).

3.6 Mortality

Mortality outcomes for intracranial artery stenosis were synthesized from two studies, which included 451 patients (224 with DES versus 227 with BMS) (18, 21). No significant difference was found in mortality between the DES and BMS groups (OR: 0.75; 95% CI: 0.17, 3.40; p = 0.71), and no significant heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 0%, p = 0.78) (Figure 5A).

Figure 5

Forest plots of (A) mortality (intracranial artery stenosis), (B) mortality (vertebral artery stenosis), (C) adverse events (intracranial artery stenosis), (D) adverse events (vertebral artery stenosis), and (E) periprocedural complications (vertebral artery stenosis).

Results of mortality for vertebral artery stenosis were synthesized from 2 studies, which included 218 patients (117 DES versus 101 BMS) (23, 31). No significant difference in mortality rates between the DES and BMS groups was observed (OR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.29, 1.52; p = 0.34), and there was no significant heterogeneity noted (I2 = 0%, p = 0.44) (Figure 5B).

3.7 Adverse events

Adverse event outcomes related to intracranial artery stenosis were synthesized from two studies, which included 451 patients (224 with DES versus 227 with BMS) (18, 21). No significant difference was found between the DES and BMS groups for adverse events (OR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.20, 1.95; p = 0.42), and no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, p = 0.45) was observed (Figure 5C).

Results of adverse events for vertebral artery stenosis were synthesized from two studies, which included 80 patients (36 receiving DES versus 44 receiving BMS) (32, 33). In the DES group, a meta-analysis revealed a significantly lower rate of adverse events (OR: 0.08; 95% CI: 0.02, 0.38; p = 0.001), with no significant heterogeneity detected (I2 = 0%, p = 0.83) (Figure 5D).

3.8 Periprocedural complications

Four studies, comprising 811 patients (361 with DES and 450 with BMS), were analyzed to synthesize data on periprocedural complications related to vertebral artery stenosis (20, 23, 35, 36). No significant difference in periprocedural complications rate was observed between the DES and BMS groups (OR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.41, 2.02; p = 0.82), with no significant heterogeneity detected (I2 = 0%, p = 0.78) (Figure 5E). Within all subgroups, the results consistently showed insignificance in the subgroup analysis (Table 5).

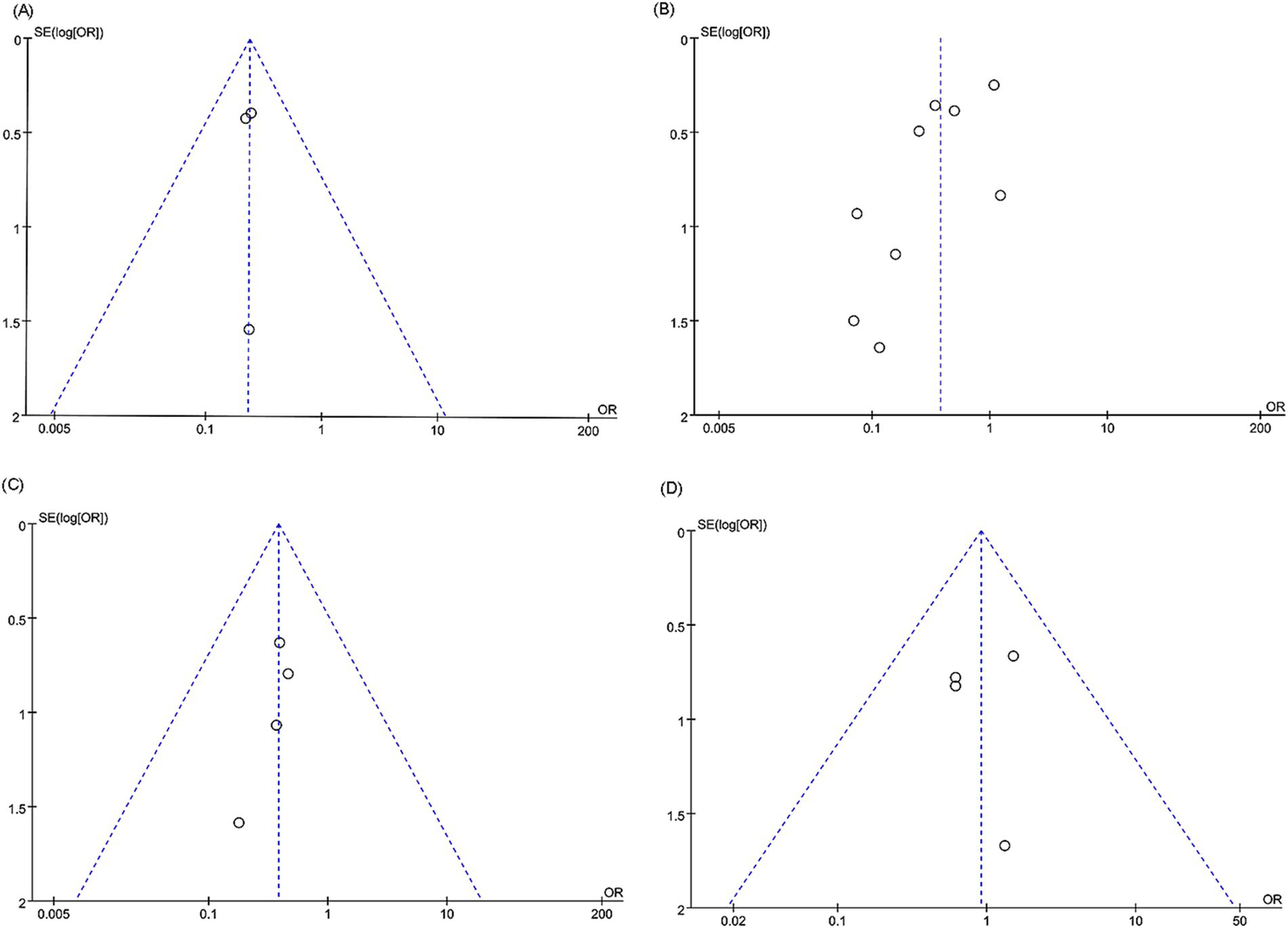

3.9 Publication bias

For in-stent restenosis (intracranial artery stenosis), in-stent restenosis (vertebral artery stenosis), postoperative stroke (vertebral artery stenosis), and periprocedural complications (vertebral artery stenosis), we examined potential publication bias using funnel plots and Egger’s regression tests. Both statistical (Egger’s test) and visual (funnel plots) analyses detected no evidence of publication bias for in-stent restenosis in the intracranial artery (Egger’s test p = 1.000) (Figure 6A), in-stent restenosis in the vertebral artery (Egger’s test p = 0.050) (Figure 6B), postoperative stroke in the vertebral artery (Egger’s test p = 0.202) (Figure 6C), and periprocedural complications in the vertebral artery (Egger’s test p = 0.944) (Figure 6D).

Figure 6

Funnel plots of (A) in-stent restenosis (intracranial artery stenosis), (B) in-stent restenosis (vertebral artery stenosis), (C) postoperative stroke (vertebral artery stenosis), and (D) periprocedural complications (vertebral artery stenosis).

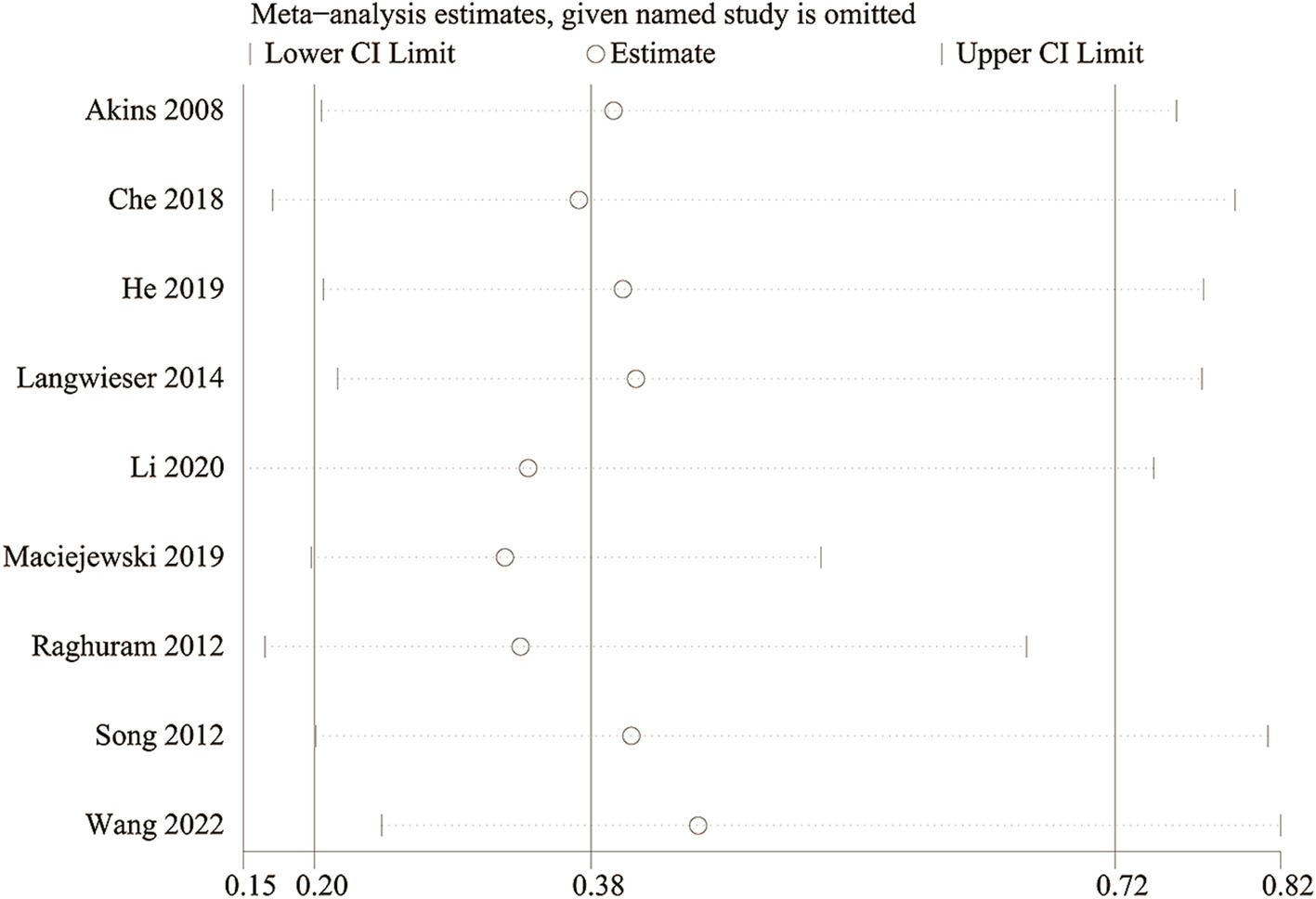

3.10 Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the impact of each study on the overall OR for in-stent restenosis (specifically focusing on vertebra artery stenosis) by systematically excluding eligible studies one at a time. Our analysis revealed that even with the removal of each individual study, the total OR for in-stent restenosis (vertebral artery stenosis) remained consistent (Figure 7). However, upon removal of the study reported by Maciejewski et al. (36), the heterogeneity of in-stent restenosis (specifically, vertebral artery stenosis) decreased from 63 to 16%, suggesting that this paper might have been the main contributor to the significant heterogeneity observed in in-stent restenosis (vertebral artery stenosis).

Figure 7

Sensitivity analysis of in-stent restenosis (vertebral artery stenosis).

4 Discussion

Stenting is considered inferior to aggressive medical therapy as a potential management strategy for intracranial or vertebral artery stenosis with impaired blood flow, primarily due to the high adverse event rates linked with stenting (13, 17, 39). In-stent restenosis presents another major obstacle to successful stenting, often resulting in non-procedural ischemic events (40, 41). In patients receiving the recent standard of self-expanding or balloon-installed BMS, in-stent restenosis appears within 1 year in 15 to 33% of cases (42–45). After stent implantation, DES reduce in-stent restenosis by restraining the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells (46). In the treatment of arterial stenosis, DES has changed the status by reducing in-stent restenosis and associated ischemic events (47, 48). DES has been recommended as the standard device for percutaneous coronary intervention rather than BMS recently (49). However, the debate continues regarding whether DES outperforms BMS in terms of efficacy and safety for intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis.

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis comparing DES and BMS for intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis. Despite differences in the design and type of stent used, similar results to some previous studies were shown in this study (18–21, 35). Among patients with stenosis in the intracranial and vertebral arteries, restenosis has been reported as a key factor affecting the long-term efficacy of treatment (20). Our study findings show a significant reduction in in-stent restenosis rates among patients with intracranial or vertebral artery stenosis who underwent treatment with DES compared to those who received BMS. The findings of our study are consistent with those of two previously published meta-analyses, which suggest that patients with symptomatic extracranial vertebral artery stenosis had a higher incidence of restenosis in the BMS group compared to DES (50, 51). Additionally, in two large case series, a higher risk of restenosis was found to be related to BMS in patients with vertebral artery stenosis (22, 52). The mechanism for the higher rate of restenosis in the BMS group is unclear. Studies have shown that the two main causes of restenosis in BMS may be recoil and intimal hyperplasia (53, 54). It is worth mentioning that, unlike DES, BMS does not apply antiproliferative medications that restrict smooth muscle cell proliferation. Therefore, it can be speculated that the deficiency of inhibition of intimal hyperplasia in the BMS group resulted in the most severe stenosis advancement and the highest restenosis rate during follow-up in the BMS group.

Furthermore, our meta-analysis found a significant lower postoperative stroke rate in the DES group for vertebral artery stenosis, while no significant difference was observed between the DES and BMS group for intracranial artery stenosis. Despite all four articles addressing postoperative stroke (vertebral artery stenosis) and reporting non-significant differences between DES and BMS, the outcomes of the studies were all skewed in favor of the DES group. After conducting pooled analysis, it was ultimately determined that the DES cohort exhibited a reduced incidence of postoperative stroke, with no notable heterogeneity observed as a result. This discovery could be attributed to the reduced incidence of in-stent stenosis observed in the DES cohort. Our study found no significant difference, generally, in mortality, adverse effects, and perioperative complications between the DES group and the BMS group. Despite the meta-analysis indicating a significant reduction in adverse events rates within the DES group compared to the BMS group for vertebral artery stenosis, it’s important to acknowledge that only two original studies contributed to this finding. Therefore, further research is essential to corroborate these results. In addition, subgroup analysis found that the advantage of DES in restenosis rate disappeared when the follow-up time exceeded 24 months. This finding may be related to the characteristics of DES. As time goes by, the dose of drugs released by DES will gradually decrease, and its average service life is 3–10 years, so its long-term treatment effect may not be significantly better than BMS (55). In addition, although DES can reduce the restenosis rate, long-term drug release and polymer stimulation may increase the risk of thrombosis, which will also affect the long-term efficacy (55).

We must acknowledge several limitations of this meta-analysis. Firstly, all included RCTs reported a high risk in the blinding of participants and personnel because of the deficiency of feasibility of blinding for the type of stents used, and only 1 of 3 included RCTs had low risk in the allocation concealment, which may lead to some bias. Secondly, most of the original studies on intracranial arterial stenosis included in this meta-analysis did not consider the separation of patients with anterior and posterior circulation. Due to the different natural history of arterial stenosis in the anterior and posterior circulation, the operation method, clinical prognosis and restenosis rate after stenting are also different. Thirdly, we conducted subgroup analysis on some outcomes according to the study design, follow-up time and region, and the subgroup analysis found that the results were not stable in different subgroups, suggesting that this study still had a certain degree of heterogeneity, although most the results are reported as non-significant Cochran’s Q p-values. In addition, the drug eluting inhibitors involved in this article mainly include tacrolimus, sirolimus and paclitaxel, which may be one of the sources of heterogeneity. However, there are few literatures reporting specific drug eluting inhibitors, and we cannot perform subgroup analysis based on this factor to explore its impact on the results. Besides, in all included literature, the most common pre- and post-implantation treatment drugs included aspirin, clopidogrel, and ticlopidin. However, because the patients included in each study had different disease courses and characteristics, the pre- and post-implantation drug doses and treatment courses were very heterogeneous among the studies, and subgroup analysis could not be performed, although we believe that different antiplatelet regimens will affect the treatment success rate and long-term prognosis of patients. Despite several limitations of this meta-analysis, we conducted the first meta-analysis comparing DES and BMS for intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis. Results of this meta-analysis validated the superiority of the DES intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis reported by previous studies.

5 Conclusion

Pooled analyses have revealed that DES, when compared to BMS, exhibit a significant reduction in the risk of in-stent restenosis (including intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis) as well as postoperative stroke (particularly in cases of vertebral artery stenosis). However, this superiority appears to be limited to a relatively short follow-up period. Generally, DES and BMS demonstrate similar safety profiles for intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis. To further evaluate the efficacy and safety of drug-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in patients with symptomatic intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis, additional large-scale, multi-center, double-blind RCTs are warranted.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. WL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. LZ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Funds of China (Grant No. 81971098) to LZ.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2024.1389254/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Leng X Hurford R Feng X Chan KL Wolters FJ Li L et al . Intracranial arterial stenosis in Caucasian versus Chinese patients with TIA and minor stroke: two contemporaneous cohorts and a systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2021) 92:590–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-325630

2.

Hurford R Wolters FJ Li L Lau KK Küker W Rothwell PM . Prevalence, predictors, and prognosis of symptomatic intracranial stenosis in patients with transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Neurol. (2020) 19:413–21. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30079-X

3.

Wang Y Zhao X Liu L Soo YO Pu Y Pan Y et al . Prevalence and outcomes of symptomatic intracranial large artery stenoses and occlusions in China: the Chinese Intracranial Atherosclerosis (CICAS) Study. Stroke. (2014) 45:663–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003508

4.

Qureshi AI Caplan LR . Intracranial atherosclerosis. Lancet. (2014) 383:984–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61088-0

5.

Holmstedt CA Turan TN Chimowitz MI . Atherosclerotic intracranial arterial stenosis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. (2013) 12:1106–14. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70195-9

6.

Thompson MC Issa MA Lazzaro MA Zaidat OO . The natural history of vertebral artery origin stenosis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2014) 23:e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.12.004

7.

Wityk RJ Chang HM Rosengart A Han WC DeWitt LD Pessin MS et al . Proximal extracranial vertebral artery disease in the New England Medical Center Posterior Circulation Registry. Arch Neurol. (1998) 55:470–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.4.470

8.

Kim YJ Lee JH Choi JW Roh HG Chun YI Lee JS et al . Long-term outcome of vertebral artery origin stenosis in patients with acute ischemic stroke. BMC Neurol. (2013) 13:171. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-171

9.

Gulli G Marquardt L Rothwell PM Markus HS . Stroke risk after posterior circulation stroke/transient ischemic attack and its relationship to site of vertebrobasilar stenosis: pooled data analysis from prospective studies. Stroke. (2013) 44:598–604. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.669929

10.

Bamford J Sandercock P Dennis M Burn J Warlow C . Classification and natural history of clinically identifiable subtypes of cerebral infarction. Lancet. (1991) 337:1521–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93206-O

11.

Kleindorfer DO Towfighi A Chaturvedi S Cockroft KM Gutierrez J Lombardi-Hill D et al . 2021 guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. (2021) 52:e364–467. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000375

12.

Liu L Wong KS Leng X Pu Y Wang Y Jing J et al . Dual antiplatelet therapy in stroke and ICAS: subgroup analysis of CHANCE. Neurology. (2015) 85:1154–62. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001972

13.

Chimowitz MI Lynn MJ Derdeyn CP Turan TN Fiorella D Lane BF et al . Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. (2011) 365:993–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105335

14.

Leng X Lan L Ip HL Abrigo J Scalzo F Liu H et al . Hemodynamics and stroke risk in intracranial atherosclerotic disease. Ann Neurol. (2019) 85:752–64. doi: 10.1002/ana.25456

15.

Sangha RS Naidech AM Corado C Ansari SA Prabhakaran S . Challenges in the medical management of symptomatic intracranial stenosis in an urban setting. Stroke. (2017) 48:2158–63. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.016254

16.

Wabnitz AM Derdeyn CP Fiorella DJ Lynn MJ Cotsonis GA Liebeskind DS et al . Hemodynamic markers in the anterior circulation as predictors of recurrent stroke in patients with intracranial stenosis. Stroke. (2018) 50:143–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.020840

17.

Derdeyn CP Chimowitz MI Lynn MJ Fiorella D Turan TN Janis LS et al . Aggressive medical treatment with or without stenting in high-risk patients with intracranial artery stenosis (SAMMPRIS): the final results of a randomised trial. Lancet. (2014) 383:333–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62038-3

18.

Si JH Ma N Gao F Mo DP Luo G Miao ZR . Effect of a drug-eluting stent vs. bare metal stent for the treatment of symptomatic intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:854226. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.854226

19.

Wu S Yin Y Li Z Li N Ma W Zhang L . Using drug-coated balloons for symptomatic vertebral artery origin stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Neurosci. (2023) 107:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2022.12.004

20.

Wang Z Ling Y Zhao H Mao Y Dong Q Cao W . A comparison of different endovascular treatment for vertebral artery origin stenosis. World Neurosurg. (2022) 164:e1290–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.06.026

21.

Jia B Zhang X Ma N Mo D Gao F Sun X et al . Comparison of drug-eluting stent with bare-metal stent in patients with symptomatic high-grade intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. (2022) 79:176–84. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.4804

22.

Che WQ Dong H Jiang XJ Peng M Zou YB Xiong HL et al . Clinical outcomes and influencing factors of in-stent restenosis after stenting for symptomatic stenosis of the vertebral V1 segment. J Vasc Surg. (2018) 68:1406–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.02.042

23.

Song L Li J Gu Y Yu H Chen B Guo L et al . Drug-eluting vs. bare metal stents for symptomatic vertebral artery stenosis. J Endovasc Ther. (2012) 19:231–8. doi: 10.1583/11-3718.1

24.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

25.

Wan X Wang W Liu J Tong T . Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2014) 14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135

26.

Luo D Wan X Liu J Tong T . Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res. (2018) 27:1785–805. doi: 10.1177/0962280216669183

27.

Wells G Shea B O’Connell D Peterson J Welch V Losos M et al . (2011) The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available at:http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. (Accessed December 28, 2020)

28.

Kim SR Kim K Lee SA Kwon SO Lee JK Keum N et al . Effect of red, processed, and white meat consumption on the risk of gastric cancer: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis. Nutrients. (2019) 11:826. doi: 10.3390/nu11040826

29.

Cumpston M Li T Page MJ Chandler J Welch VA Higgins JP et al . Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2019) 10:ED000142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000142

30.

Higgins JP Thompson SG . Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2002) 21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186

31.

Akins PT Kerber CW Pakbaz RS . Stenting of vertebral artery origin atherosclerosis in high-risk patients: bare or coated? A single-center consecutive case series. J Invasive Cardiol. (2008) 20:14–20. PMID:

32.

He Y Li T Bai W Zhu L Wang M Zhang Y . Cerebrovascular drug-eluting stent versus bare-metal stent in the treatment of vertebral artery stenosis: a non-inferiority randomized clinical trial. J Stroke. (2019) 21:101–4. doi: 10.5853/jos.2018.00479

33.

Langwieser N Prothmann S Buyer D Poppert H Schuster T Fusaro M et al . Safety and efficacy of different stent types for the endovascular therapy of extracranial vertebral artery disease. Clin Res Cardiol. (2014) 103:353–62. doi: 10.1007/s00392-013-0659-x

34.

Lee JH Jo SM Jo KD Kim MK Lee SY You SH . Comparison of drug-eluting coronary stents, bare coronary stents and self-expanding stents in angioplasty of middle cerebral artery stenoses. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg. (2013) 15:85–95. doi: 10.7461/jcen.2013.15.2.85

35.

Li L Wang X Yang B Wang Y Gao P Chen Y et al . Validation and comparison of drug eluting stent to bare metal stent for restenosis rates following vertebral artery ostium stenting: a single-center real-world study. Interv Neuroradiol. (2020) 26:629–36. doi: 10.1177/1591019920949371

36.

Maciejewski DR Pieniazek P Tekieli L Paluszek P Przewlocki T Tomaszewski T et al . Comparison of drug-eluting and bare metal stents for extracranial vertebral artery stenting. Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej. (2019) 15:328–37. doi: 10.5114/aic.2019.87887

37.

Raghuram K Seynnaeve C Rai AT . Endovascular treatment of extracranial atherosclerotic disease involving the vertebral artery origins: a comparison of drug-eluting and bare-metal stents. J Neurointerv Surg. (2012) 4:206–10. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2011-010051

38.

Egger M Davey Smith G Schneider M Minder C . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. (1997) 315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

39.

Zaidat OO Fitzsimmons BF Woodward BK Wang Z Killer-Oberpfalzer M Wakhloo A et al . Effect of a balloon-expandable intracranial stent vs medical therapy on risk of stroke in patients with symptomatic intracranial stenosis: the VISSIT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2015) 313:1240–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1693

40.

Derdeyn CP Fiorella D Lynn MJ Turan TN Cotsonis GA Lane BF et al . Nonprocedural symptomatic infarction and in-stent restenosis after intracranial angioplasty and stenting in the SAMMPRIS trial (Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for the Prevention of Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis). Stroke. (2017) 48:1501–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.014537

41.

Jin M Fu X Wei Y Du B Xu XT Jiang WJ . Higher risk of recurrent ischemic events in patients with intracranial in-stent restenosis. Stroke. (2013) 44:2990–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001824

42.

Kang K Zhang Y Shuai J Jiang C Zhu Q Chen K et al . Balloon-mounted stenting for ICAS in a multicenter registry study in China: a comparison with the WEAVE/WOVEN trial. J Neurointerv Surg. (2021) 13:894–9. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016658

43.

Peng G Zhang Y Miao Z . Incidence and risk factors of in-stent restenosis for symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. (2020) 41:1447–52. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6689

44.

Zhang L Huang Q Zhang Y Liu J Hong B Xu Y et al . Wingspan stents for the treatment of symptomatic atherosclerotic stenosis in small intracranial vessels: safety and efficacy evaluation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. (2012) 33:343–7. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2772

45.

Levy EI Turk AS Albuquerque FC Niemann DB Aagaard-Kienitz B Pride L et al . Wingspan in-stent restenosis and thrombosis: incidence, clinical presentation, and management. Neurosurgery. (2007) 61:644–51. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000290914.24976.83

46.

Inoue T Node K . Molecular basis of restenosis and novel issues of drug-eluting stents. Circ J. (2009) 73:615–21. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-09-0059

47.

Stone GW Ellis SG Cox DA Hermiller J O'Shaughnessy C Mann JT et al . A polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. (2004) 350:221–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032441

48.

Moses JW Leon MB Popma JJ Fitzgerald PJ Holmes DR O'Shaughnessy C et al . Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med. (2003) 349:1315–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035071

49.

Neumann FJ Sousa-Uva M Ahlsson A Alfonso F Banning AP Benedetto U et al . 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. (2019) 40:87–165. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394

50.

Tank VH Ghosh R Gupta V Sheth N Gordon S He W et al . Drug eluting stents versus bare metal stents for the treatment of extracranial vertebral artery disease: a meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. (2016) 8:770–4. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-011697

51.

Langwieser N Buyer D Schuster T Haller B Laugwitz KL Ibrahim T . Bare metal vs. drug-eluting stents for extracranial vertebral artery disease: a meta-analysis of nonrandomized comparative studies. J Endovasc Ther. (2014) 21:683–92. doi: 10.1583/14-4713MR.1

52.

Li J Hua Y Needleman L Forsberg F Eisenbray JR Li Z et al . Arterial occlusions increase the risk of in-stent restenosis after vertebral artery ostium stenting. J Neurointerv Surg. (2019) 11:574–8. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014243

53.

Stayman AN Nogueira RG Gupta R . A systematic review of stenting and angioplasty of symptomatic extracranial vertebral artery stenosis. Stroke. (2011) 42:2212–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.611459

54.

Albuquerque FC Fiorella D Han P Spetzler RF McDougall CG . A reappraisal of angioplasty and stenting for the treatment of vertebral origin stenosis. Neurosurgery. (2003) 53:607–16. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000079494.87390.28

55.

Bajeu IT Niculescu AG Scafa-Udriște A Andronescu E . Intrastent restenosis: a comprehensive review. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:1715. doi: 10.3390/ijms25031715

Summary

Keywords

drug-eluting stent, bare-metal stent, intracranial artery stenosis, vertebral artery stenosis, meta-analysis

Citation

Zhang Y, Li W and Zhang L (2024) Efficacy and safety of drug-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in symptomatic intracranial and vertebral artery stenosis: a meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 15:1389254. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1389254

Received

28 April 2024

Accepted

14 October 2024

Published

05 November 2024

Volume

15 - 2024

Edited by

Yin Huang, Sichuan University, China

Reviewed by

Marie-Sophie Schüngel, University Hospital in Halle, Germany

Dehong Cao, Sichuan University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Zhang, Li and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lei Zhang, zhangl92@sysu.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.