Abstract

Objectives:

This meta-analysis investigated the relationship between herpes zoster and the risk of dementia or Parkinson’s disease by analyzing published clinical studies.

Methods:

We systematically searched PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, and Web of Science Core Collection databases on April 25, 2024. Hazard ratios (HR) were used for statistical analyses. Random-effects models were applied, and heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic.

Results:

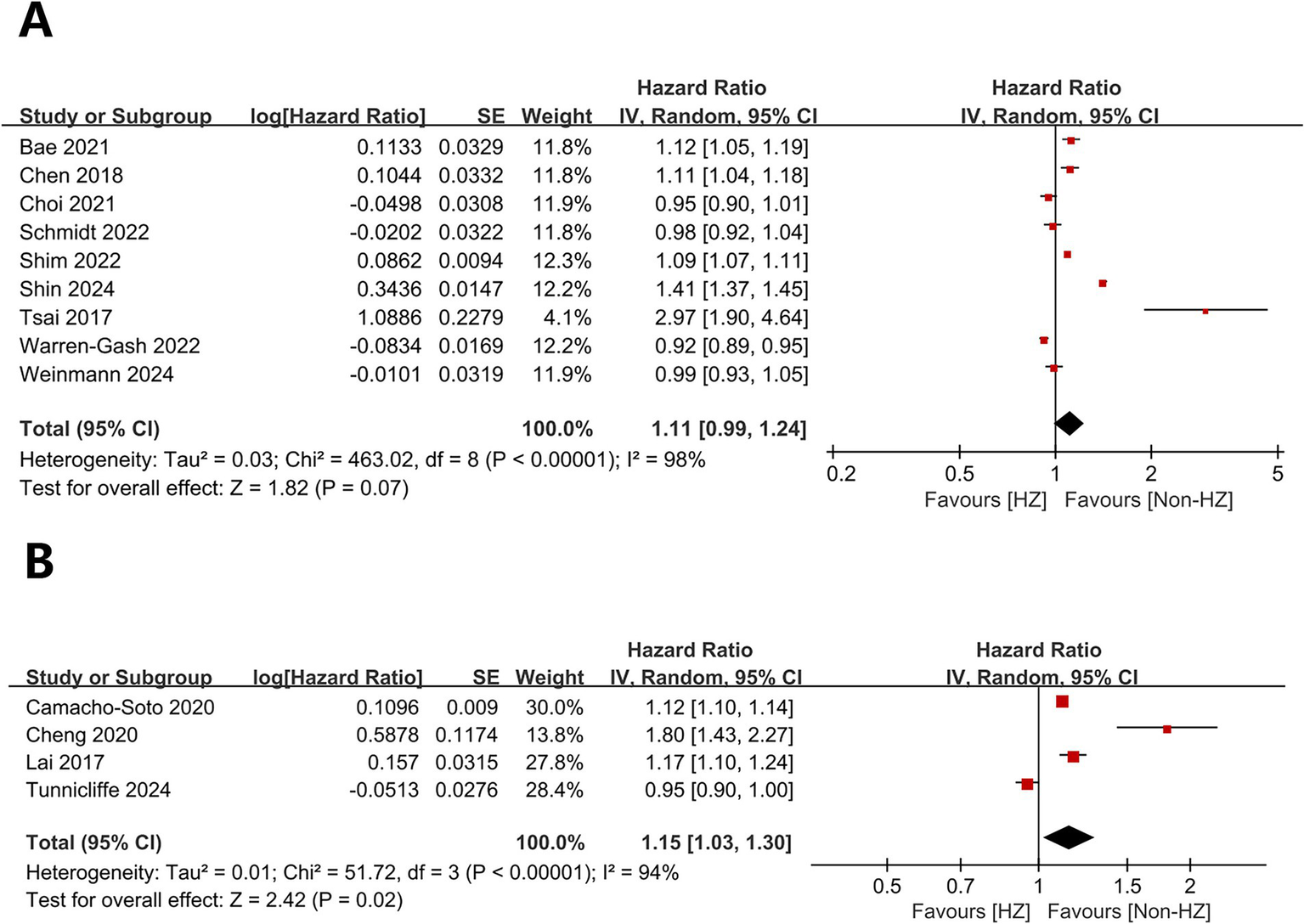

Herpes zoster was associated with a non-significant trend toward increased dementia risk (HR = 1.11, 95% CI 0.99–1.24, p = 0.07) but significantly increased Parkinson’s disease risk (HR = 1.15, 95% CI 1.03–1.30, p = 0.02). Subgroup analyses revealed that herpes zoster significantly elevated the risk of the prospective study subgroup (HR = 1.08, 95% CI 1.02–1.13, p = 0.004) and vascular dementia subgroup (HR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.00–1.37, p = 0.05). Significant heterogeneity was observed for both outcomes (dementia: I2 = 98%, p < 0.00001; Parkinson’s disease: I2 = 94%, p < 0.00001).

Conclusion:

Herpes zoster raises the risk of Parkinson’s disease and vascular dementia, with a potential causal link to dementia. Early vaccination against herpes zoster is recommended over post-infection antiviral treatment to mitigate risks.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ and our registration number is CRD42024555620.

Introduction

With the global population increasing and aging, neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia, have become significant causes of disability worldwide, posing a substantial public health burden. PD is a neurodegenerative movement disorder strongly associated with aging, with a lifetime prevalence of 1–5%, and its risk increases significantly with age. In addition to motor symptoms such as bradykinesia and resting tremor, Parkinson’s also leads to non-motor symptoms like depression, sleep disturbances, and cognitive deficits, all of which severely impact patients’ quality of life. Similarly, dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies, is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder primarily characterized by persistent cognitive impairment, significantly disrupting daily life. According to the 2015 World Alzheimer’s Disease Report, the global population of people living with dementia reached 46.8 million and is projected to double every 20 years (1–5).

Aging, genetic predisposition, educational level, and socioeconomic status are widely recognized as potential risk factors for dementia and PD (6). Emerging evidence suggests a significant correlation between neuroviral infections, accelerated brain aging, and heightened susceptibility to neurodegenerative diseases (7, 8). A variety of viruses can trigger neuroinfections, including Herpesviridae family members [e.g., Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), varicella zoster virus (VZV)], hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) (9–14). Among these, more than 95% of individuals over the age of 50 globally have been exposed to VZV and the risk for this group is significant (15), necessitating further investigation into its association with dementia and PD.

A number of prospective or retrospective clinical studies have examined the relationship between herpes zoster and dementia or PD, yet the findings have been inconsistent. For instance, Cheng et al. (16) and Lai et al. (17) found an increased risk of PD in patients with herpes zoster, while Tunnicliffe et al. (18) reached the opposite conclusion. Similarly, studies investigating the relationship between herpes patients and dementia (19–21) have also yielded contradictory results. To better understand the relationship between herpes zoster and dementia or PD, we collected, analyzed, and summarized data from a wide range of studies across four commonly used databases.

Materials and methods

Literature search

This study followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) (Supplementary Table S1) checklist published in 2020 (22) and was registered in the PROSPERO (CRD42024555620) system. We conducted a systematic literature search in four databases: PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, and Web of Science Core Collection, with a cut-off date of April 25, 2024. The search was performed in English using the keywords “herpes zoster,” “Parkinson’s disease,” and “dementia” (Supplementary Table S2). At least two clinicians manually reviewed all relevant literature multiple times to ensure relevance, eliminate disagreements, and meet the requirements.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following PICOS principles guided the inclusion criteria:

Participants: Patients with herpes zoster and a control population without herpes zoster;

Intervention: Herpes zoster;

Comparison: Control population without herpes zoster;

Outcome: Prevalence of dementia and PD (calculated as hazard ratio);

Study design: Cohort or case–control studies.

Studies were excluded if they (1) investigated infectious diseases caused by herpes viruses other than herpes zoster, (2) did not provide accessible data on the prevalence of dementia or PD, (3) were non-original papers (e.g., conference abstracts, letters, editorials, or replies), (4) were reviews, case reports, or similar, or (5) were not published in English.

Data extraction

Yanfeng Zhang and Weiping Liu independently conducted the literature search, content screening, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment. Disagreements were resolved through consultation with a more experienced third author, Yang Xu, and consensus decision-making. Studies meeting the inclusion criteria and reporting data were included in the analyses, and outcome data related to study characteristics were extracted. Notably, despite being a conference abstract, Chen et al. (23) provided the required data for analysis and was included to collect a larger number of studies.

Quality assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to independently assess the included case–control and cohort studies. Studies scoring 7–9 were considered high quality (24). As with data extraction, disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager version 5.4.1 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK), with HR as the uniform assessment measure. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for all outcome metrics and estimated heterogeneity between studies using the inconsistency index (I2) (25). Significant heterogeneity was defined as p < 0.05 or I2 > 50%. All data were analyzed using a random effects model. For analyses with ≥10 studies, funnel plots were created using Review Manager 5.4.1, and potential publication bias was evaluated using Egger’s regression tests with Stata version 15.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, United States). p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study characteristics and results of the screening process

The literature screening methodology and process are displayed in Figure 1. We searched 1,077 publications: 359 from PubMed, 434 from Embase, 19 from Cochrane, and 265 from Web of Science Core Collection. After excluding publications not meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 13 studies (16–21, 23, 26–31) were included for analysis. The basic characteristics of each study are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1

Flowchart of literature screening process.

Table 1

| Authors | Study period | Country | Study design | Patients (n) | Follow-up | Mean age (year) | Male | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HZ/Non-HZ | HZ/Non-HZ | HZ/Non-HZ | ||||||

| Bae 2021 | 2002–2013 | Korea | Prospective cohort | 34,505/195,089 | 11 years | 60.4 | 13,526 | 7 |

| Camacho-Soto 2020 | 2004–2009 | USA | Case–control | 14,508/193,377 | NA | 77.35 | 95,495 | 6 |

| Chen 2018 | 1997–2013 | China | Prospective cohort | 39,205/39,205 | NA | NA | NA | 7 |

| Cheng 2020 | 1998–2011 | China | Prospective cohort | 13,083/52,332 | 12.5 years | 60.33 | 5,834/23,336 | 7 |

| Choi 2021 | 1989–2002 | Korea | Case–control | 4,857/52,368 | NA | NA | 18,330 | 8 |

| Lai 2017 | 1998–2010 | China | Retrospective cohort | 10,296/39,405 | NA | 74.4/73.7 | 5,140/19,666 | 6 |

| Schmidt 2022 | 1997–2017 | Denmark | Prospective cohort | 247,305/1,235,890 | 21 years | 64 | 97,509/487,464 | 7 |

| Shim 2022 | 2010–2018 | Korea | Prospective cohort | 97,323/183,779 | 5.15 years | 63.48/61.95 | 38,193/89,900 | 7 |

| Shin 2024 | 2006–2017 | Korea | Retrospective cohort | 184,331/567,874 | 10.85 years | 58.8 | 348,125 | 7 |

| Tsai 2017 | 2001–2008 | China | Retrospective cohort | 846/2,538 | 5 years | 62.2 | 420/1,318 | 9 |

| Tunnicliffe 2024 | 2008–2018 | USA | Prospective cohort | 198,099/976,660 | 4.2 years | 68.17/68.14 | 185,902/918,407 | 7 |

| Warren-Gash 2022 | 2000–2017 | UK | Retrospective cohort | 177,144/706,901 | 5.5 years | 65.1 | 70,690/282,061 | 7 |

| Weinmann 2024 | 2000–2019 | USA | Retrospective cohort | 25,332/75,996 | 6.2 years | 64.0 | 9,776/29,328 | 7 |

Baseline characteristics of include studies and methodological assessment.

Assessment of study quality

The quality scores of the included studies are shown in Supplementary Table S3. One study (30) scored 9, one (20) scored 8, nine (16, 18, 19, 21, 23, 27–29, 31) scored 7, and two (17, 26) scored 6.

Outcomes of meta-analysis

Results of overall analysis

Herpes zoster did not significantly affect dementia (HR = 1.11, 95% CI 0.99–1.24, p = 0.07; Figure 2A) but significantly affected PD (HR = 1.15, 95% CI 1.03–1.30, p = 0.02; Figure 2B). Heterogeneity was present for both outcomes (dementia: I2 = 98%, p < 0.00001; PD: I2 = 94%, p < 0.00001).

Figure 2

Forest plot of overall analysis results. (A) Forest plots for overall dementia-related analyses; (B) Forest plots for overall analyses related to Parkinson’s disease.

Results of subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were conducted for the risk of herpes zoster and dementia but not for herpes zoster and PD due to limited data. Subgroup analyses demonstrated no significant relationships (p > 0.05) except for prospective studies (p = 0.004) in the study type subgroup. Notably, the p-value for vascular dementia in the dementia type subgroup was 0.05, suggesting a potential association between the variables. Heterogeneity was present in all subgroups (I2 > 50%) (Table 2).

Table 2

| Subgroup | HZ and the risk of dementia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | HR [95%CI] | p value | I 2 | |

| Total | 9 | 1.11 [0.99–1.24] | 0.07 | 98% |

| Study design | ||||

| Prospective | 4 | 1.08 [1.02–1.13] | 0.004 | 74% |

| Retrospective | 5 | 1.20 [0.94–1.51] | 0.14 | 99% |

| Follow-up | ||||

| >10 years | 3 | 1.16 [0.92–1.47] | 0.22 | 98% |

| <10 years | 4 | 1.08 [0.94–1.23] | 0.28 | 97% |

| Sample size | ||||

| >200,000 | 5 | 1.09 [0.94–1.27] | 0.25 | 99% |

| <200,000 | 4 | 1.10 [0.96–1.27] | 0.18 | 91% |

| Age | ||||

| 50–59 | 2 | 0.64 [0.21–2.00] | 0.44 | 90% |

| 60–69 | 2 | 0.85 [0.53–1.37] | 0.51 | 92% |

| >70 | 2 | 1.08 [0.96–1.23] | 0.21 | 84% |

| Types of dementia | ||||

| Alzheimer’s disease | 3 | 1.23 [0.99–1.53] | 0.06 | 99% |

| Vascular dementia | 3 | 1.17 [1.00–1.37] | 0.05 | 79% |

Subgroup analysis of HZ and the risk of dementia.

Sensitivity analysis

A one-way sensitivity analysis demonstrated the instability of both overall analyses. In the analyses of herpes zoster and dementia, the overall results were destabilized if studies by Choi et al. (20), Schmidt et al. (27), or Warren-Gash et al. (19) were individually excluded. Similarly, when evaluating herpes zoster and PD, the results became unstable with the removal of Camacho-Soto et al. (26), Cheng et al. (16), or Lai et al. (17) (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Sensitivity analysis results. (A) Overall analysis of herpes zoster and dementia and 95% CI calculations from Stata software. (B) Overall analysis of herpes zoster and Parkinson’s disease and 95% CI calculations from Stata software.

Discussion

The potential link between nervous system infections and neurodegeneration has gained widespread attention since Bowery et al.’s pioneering study in 1992, which demonstrated tetanus toxin-induced neurodegeneration in rats (32, 33). A variety of viruses that can cause infections in the nervous system [e.g., herpesvirus family (EBV, HSV, VZV, etc.), HCV, HIV, RSV, etc.] may cause protein aggregation, abnormalities in energy balance, and inflammation and lead to neurodegenerative pathologies. In recent years, viral stimulation of microglia activation in neurodegeneration has become a hot topic again in the context of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Given that over 95% of individuals aged 50 and older globally have been exposed to varicella-zoster virus, a large portion of the population is at risk for herpes zoster (15). Its potential association with dementia and PD is therefore a relevant topic. Due to the many unresolved physiological mechanisms and the ongoing controversy in current clinical study conclusions, we collected and reviewed as much relevant literature as possible to better understand the association between herpes zoster and these two neurodegenerative diseases.

Regarding dementia, our comprehensive analysis results showed that although a positive trend was observed between herpes zoster and dementia, this association lacked statistical significance. Dementia encompasses various types, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, frontotemporal dementia, Huntington’s disease, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, each with distinct pathogenic mechanisms and marker factors. Herpes zoster may influence only certain types of dementia. To further investigate the potential link, we thoroughly reviewed the data from the included studies and performed subgroup analyses based on five factors: study type, follow-up duration, sample size, subject age, and dementia classification.

The subgroup analysis revealed that factors such as follow-up duration, sample size, and participant age did not significantly affect the results. However, prospective studies demonstrated a clear positive association between herpes zoster and the risk of dementia, while retrospective studies showed no such significance. Notably, in the sensitivity analysis, excluding a larger number of retrospective studies led to a trend indicating an increased risk of dementia linked to herpes zoster.

This suggests a potential causal relationship between the two. More rigorous methods are needed to determine causality, considering confounding factors. Recent advances in evidence-based medicine have enabled Mendelian randomization to offer a more robust approach to causal inference. A recent Mendelian randomization study on the causal relationship between herpes zoster and dementia supports this conclusion, consistent with findings from a subgroup of prospective studies (34).

In a subgroup analysis of dementia types, herpes zoster was found to significantly increase the risk of vascular dementia, while the effect on Alzheimer’s disease, although showing an upward trend, did not reach statistical significance. This observation may warrant a mechanistic explanation. Although the mechanisms by which viruses cause neurodegenerative diseases remain poorly understood, based on available studies, the significant increase in the risk of vascular dementia may result from primary varicella-zoster virus infection, which initially causes chickenpox and subsequently remains latent. Under conditions such as aging or immunosuppression, the virus may reactivate and trigger herpes zoster. During this process, VZV may invade the central nervous system, causing vasculopathy and impairing cerebral blood flow, which can result in cerebral infarction and vascular dementia (35–40). In Alzheimer’s disease, neuroinflammation caused by the abnormal accumulation of amyloid β (Aβ) peptide and tau protein is the main pathogenesis. Systemic inflammation, triggered by viral infections and microglial activation, exacerbates Aβ and tau protein accumulation, thereby promoting Alzheimer’s disease progression (41, 42) Moreover, Aβ is not only a key pathological protein in Alzheimer’s disease but also a potential cellular receptor for VZV (43). The presence of Aβ may interfere with VZV replication, partially protecting the host against viral infection. This mechanism could lead to a gradual accumulation of Aβ during Alzheimer’s disease progression and a reduction in VZV’s effects (44–47) potentially explaining the nonsignificant association with herpes zoster despite a trend of increased Alzheimer’s disease risk.

Our analysis revealed a significant increase in the risk of developing PD following herpes zoster infection. However, due to the limited data in existing studies, a more detailed subgroup analysis could not be performed. PD is a complex neurodegenerative disorder presenting both motor and non-motor symptoms. The hallmark pathological features include the loss of dopaminergic neurons (48) and abnormal α-synuclein aggregation (49). The reduction of dopaminergic neurons primarily contributes to motor symptoms such as resting tremor, muscle rigidity, and bradykinesia, whereas non-motor symptoms, including cognitive impairment, autonomic dysfunction, and neurobehavioral abnormalities, are linked to α-synuclein aggregation (50). There is currently insufficient research to directly clarify the relationship between VZV and the dopamine system. Consequently, we concentrate on the non-motor symptoms of PD, particularly Parkinson’s dementia. While no definitive study has yet identified the exact mechanism through which VZV contributes to Parkinson’s dementia, we hypothesize that herpes zoster might increase the risk through the following mechanisms: abnormal aggregation of α-synuclein is a key pathological process in PD (51, 52). VZV may influence α-synuclein expression, a protein crucial to PD pathogenesis, by inducing vasculopathy, which impairs α-synuclein clearance and results in its abnormal accumulation in the brain, thereby promoting PD development (53, 54). Cross-reactivity between α-synuclein and herpesvirus peptides has been observed in PD patients (55). Abnormal α-synuclein aggregation is not limited to PD but is also linked to other α-synucleinopathies, including dementia with Lewy bodies, multiple system atrophy, the Lewy body variant of Alzheimer’s disease, and pure autonomic failure. Cognitive impairment in these conditions often accompanies cerebrovascular-like diseases (56), and VZV infection can induce vasculopathy. Thus, a theoretical association between VZV infection and other α-synucleinopathies may exist, though this hypothesis remains infrequently explored and requires further investigation.

Two key aspects of VZV infection and neurodegenerative diseases warrant attention. First, HERV-DNA transposable elements that constitute about 8% of the human genome—play a crucial role (14). Studies suggest a synergistic effect of HERVs and VZV in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis, potentially accelerating disease progression (57). The role of HERVs in conjunction with VZV in major neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and PD, remains inadequately explored, with numerous aspects still uncharted. The mitochondrial dysfunction hypothesis provides new insights into neurodegenerative disease mechanisms. Recent theories suggest that viruses might expedite microglial aging and facilitate neurodegenerative disease progression by activating microglia and inducing mitochondrial dysfunction. Moreover, VZV infection has been shown to alter mitochondrial morphology, causing fragmentation and swelling. These mitochondrial abnormalities may result in cellular damage or death during infection, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases (58).

Given the risks associated with herpes zoster, neurodegenerative diseases, and the significant impact of postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) on patients’ quality of life, appropriate coping strategies are crucial. Antiviral drugs are commonly used to treat herpes zoster. Among these, acyclovir (including its derivatives such as valaciclovir and famciclovir) is often the preferred choice. Evidence from clinical practice suggests that early antiviral therapy may lead to better outcomes. This is supported by some studies (59). It is important to note that the use of antiviral drugs is limited by various factors, including financial capacity, medical conditions, and individual health status, leading to differences in treatment outcomes. Among the 13 papers analyzed, four focused on antiviral therapy. Two studies did not find significant antiviral treatment effects after accounting for factors such as BMI, comorbidities, and unhealthy habits, while the other two suggested a potential protective effect. These findings highlight the ongoing controversy surrounding the role of antiviral therapy in reducing the risk of herpes zoster in patients with two neurodegenerative diseases.

We consider timely vaccination, especially in the absence of disease, to be the most optimal strategy at present. Various herpes zoster vaccines, including Mosquirix, Shingrix, and Nuvaxovid, are available on the market. Notably, Shingrix, the most effective vaccine, shows efficacy ranging from 96.6 to 97.9% across all age groups, with an overall efficacy of 97.2% (60). Furthermore, recently developed vaccines based on multi-nanoparticle (NP) platforms have achieved superior protective efficacy (61).

In reviewing our study, we must face up to its limitations, which are critical to fully understand and accurately assess the potential impact of the relationship between herpes zoster and dementia and PD. Firstly, despite our best efforts to include a large number of studies and to strictly control for inter-data variability factors, the high heterogeneity of the data remains a problem that cannot be ignored. This heterogeneity stems mainly from sample size limitations, which prevented certain in-depth subgroup analyses from being conducted or, if they were conducted, made it difficult to produce results with low heterogeneity. Therefore, we are cautious about the findings obtained and recognize that they may need to be further validated in larger, more refined studies in the future. Secondly, as our study primarily focused on older individuals, the applicability to younger age groups should be interpreted with caution. Further, some known risk factors for dementia or Parkinson’s, such as genetic factors, alcohol abuse, smoking, exposure to pesticides, or use of well water, were not comprehensively documented in the data from all studies in our study. This lack of information may have led to some bias in our findings, which do not fully and accurately reflect the impact of these potential factors on disease risk. Finally, our study did not break down the location of the appearance of herpes zoster. It has been shown that the association between VZV infection in the oral cavity and eyes and the risk of dementia is much stronger (29). Also, the different locations of herpes zoster may affect the diagnostic accuracy of physicians and the motivation of patients, which in turn may have an impact on the prevention and control of the disease. This factor was not fully considered in our study and may also be a reason for the biased results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, based on a comprehensive review of 13 relevant studies, we investigated the association between herpes zoster and dementia or PD. The findings indicate that herpes zoster significantly raises the risk of PD and vascular dementia. Additionally, a causal relationship exists between herpes zoster infection and dementia. Early vaccination against herpes zoster is recommended to mitigate risks, rather than antiviral treatment post-infection.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YZ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. WL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. YX: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Scientific Research Project of Hebei Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine [Fund No. 2022555]. Wang Jun National Famous Elderly Chinese Medicine Experts Inheritance Workshop [Chinese Medicine Teaching Letter (2022) No. 75].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2024.1471736/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Coelho M Ferreira JJ . Late-stage Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. (2012) 8:435–42. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.126

2.

Fernandez HH Galvez-Jimenez N Fernandez HH . Nonmotor complications of Parkinson disease. Cleve Clin J Med. (2012) 79:S14–8. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.79.s2a.03

3.

Noyce AJ Bestwick JP Silveira-Moriyama L Hawkes CH Giovannoni G Lees AJ et al . Meta-analysis of early nonmotor features and risk factors for Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. (2012) 72:893–901. doi: 10.1002/ana.23687

4.

Matthews KA Xu W Gaglioti AH Holt JB Croft JB Mack D et al . Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias in the United States (2015–2060) in adults aged ≥65 years. Alzheimers Dement. (2019) 15:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.3063

5.

Prince M Wimo A Guerchet M Ali GC Wu Y-T Prina M et al . World Alzheimer report 2015: The global impact of dementia. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International (2015).

6.

Weiss J Puterman E Prather AA Ware EB Rehkopf DH . A data-driven prospective study of dementia among older adults in the United States. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0239994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239994

7.

Osorio C Sfera A Anton JJ Thomas KG Andronescu CV Li E et al . Virus-induced membrane fusion in neurodegenerative disorders. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2022) 12:845580. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.845580

8.

Leblanc P Vorberg IM . Viruses in neurodegenerative diseases: more than just suspects in crimes. PLoS Pathog. (2022) 18:e1010670. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010670

9.

Soldan SS Lieberman PM . Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2023) 21:51–64. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00770-5

10.

Amirsardari Z Rahmani F Rezaei N . Cognitive impairments in HCV infection: from pathogenesis to neuroimaging. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. (2019) 41:987–1000. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2019.1652728

11.

Murray J Meloni G Cortes EP KimSilva A Jacobs M Ramkissoon A et al . Frontal lobe microglia, neurodegenerative protein accumulation, and cognitive function in people with HIV. Acta Neuropathol Commun. (2022) 10:69. doi: 10.1186/s40478-022-01375-y

12.

Jia X Gao Z Hu H . Microglia in depression: current perspectives. Sci China Life Sci. (2021) 64:911–25. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1815-6

13.

Hu M Bogoyevitch MA Jans DA . Subversion of host cell mitochondria by RSV to favor virus production is dependent on inhibition of mitochondrial complex I and ROS generation. Cells. (2019) 8:1417. doi: 10.3390/cells8111417

14.

Adler GL Le K Fu Y Kim WS . Human endogenous retroviruses in neurodegenerative diseases. Genes. (2024) 15:745. doi: 10.3390/genes15060745

15.

Johnson RW Alvarez-Pasquin MJ Bijl M Franco E Gaillat J Clara JG et al . Herpes zoster epidemiology, management, and disease and economic burden in Europe: a multidisciplinary perspective. Ther Adv Vaccines. (2015) 3:109–20. doi: 10.1177/2051013615599151

16.

Cheng CM Bai YM Tsai CF Tsai SJ Wu YH Pan TL et al . Risk of Parkinson's disease among patients with herpes zoster: a nationwide longitudinal study. CNS Spectr. (2020) 25:797–802. doi: 10.1017/S1092852919001664

17.

Lai SW Lin CH Lin HF Lin CL Lin CC Liao KF . Herpes zoster correlates with increased risk of Parkinson's disease in older people: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine. (2017) 96:e6075. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006075

18.

Tunnicliffe L Weil RS Breuer J Rodriguez-Barradas MC Smeeth L Rentsch CT et al . Herpes zoster and risk of incident Parkinson's disease in US veterans: a matched cohort study. Mov Disord. (2024) 39:438–44. doi: 10.1002/mds.29701

19.

Warren-Gash C Williamson E Shiekh SI Borjas-Howard J Pearce N Breuer JM et al . No evidence that herpes zoster is associated with increased risk of dementia diagnosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. (2022) 9:363–74. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51525

20.

Choi HG Park BJ Lim JS Sim SY Jung YJ Lee SW . Herpes zoster does not increase the risk of neurodegenerative dementia: a case-control study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. (2021) 36:15333175211006504. doi: 10.1177/15333175211006504

21.

Bae S Yun SC Kim MC Yoon W Lim JS Lee SO et al . Association of herpes zoster with dementia and effect of antiviral therapy on dementia: a population-based cohort study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2021) 271:987–97. doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01157-4

22.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

23.

Chen VC Wu SI Huang KY Yang YH Kuo TY Liang HY et al . Herpes zoster and dementia: a Nationwide population-based cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. (2018) 79:16m11312. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11312

24.

Wells G Shea B O’Connell D Peterson J Welch V Losos M et al . The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. (2000). Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (Accessed October 30, 2020).

25.

Higgins JP Thompson SG . Quantifying heterogeneity in a Meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2002) 21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186

26.

Camacho-Soto A Faust I Racette BA Clifford DB Checkoway H Searles Nielsen S . Herpesvirus infections and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Neurodegener Dis. (2020) 20:97–103. doi: 10.1159/000512874

27.

Schmidt SAJ Veres K Sørensen HT Obel N Henderson VW . Incident herpes zoster and risk of dementia: a population-based Danish cohort study. Neurology. (2022) 99:e660–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200709

28.

Shim Y Park M Kim J . Increased incidence of dementia following herpesvirus infection in the Korean population. Medicine. (2022) 101:e31116. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000031116

29.

Shin E Chi SA Chung TY Kim HJ Kim K Lim DH . The associations of herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus infection with dementia: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Alz Res Therapy. (2024) 16:57. doi: 10.1186/s13195-024-01418-7

30.

Tsai M-C Cheng WL Sheu JJ Huang CC Shia BC Kao LT et al . Increased risk of dementia following herpes zoster ophthalmicus. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0188490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188490

31.

Weinmann S Rawlings A Koppolu P Rosales AG Prado YK Schmidt MA . Herpes zoster diagnosis and treatment in relation to incident dementia: a population-based retrospective matched cohort study. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0296957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0296957

32.

Bowery NG Bagetta G Nisticó G Britton P Whitton P . Intrahippocampal tetanus toxin produces generalized convulsions and neurodegeneration in rats: antagonism by NMDA receptor blockers. Epilepsy Res Suppl. (1992) 9:249–56. PMID:

33.

Mattson MP . Infectious agents and age-related neurodegenerative disorders. Ageing Res Rev. (2004) 3:105–20. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2003.08.005

34.

Huang SY Yang YX Kuo K Li HQ Shen XN Chen SD et al . Herpesvirus infections and Alzheimer's disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Alzheimers Res Ther. (2021) 13:158. doi: 10.1186/s13195-021-00905-5

35.

Kling MA Trojanowski JQ Wolk DA Lee VM Arnold SE . Vascular disease and dementias: paradigm shifts to drive research in new directions. Alzheimers Dement. (2013) 9:76–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.02.007

36.

Gilden D Cohrs RJ Mahalingam R Nagel MA . Varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: diverse clinical manifestations, laboratory features, pathogenesis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. (2009) 8:731–40. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70134-6

37.

Steain M Sutherland JP Rodriguez M Cunningham AL Slobedman B Abendroth A . Analysis of T cell responses during active varicella-zoster virus reactivation in human ganglia. J Virol. (2014) 88:2704–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03445-13

38.

Skripuletz T Pars K Schulte A Schwenkenbecher P Yildiz Ö Ganzenmueller T et al . Varicella zoster virus infections in neurological patients: a clinical study. BMC Infect Dis. (2018) 18:238. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3137-2

39.

Nagel MA Bubak AN . Varicella zoster virus vasculopathy. J Infect Dis. (2018) 218:S107–12. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy425

40.

Silver B Nagel MA Mahalingam R Cohrs R Schmid DS Gilden D . Varicella zoster virus vasculopathy: a treatable form of rapidly progressive multi-infarct dementia after 2 years’ duration. J Neurol Sci. (2012) 323:245–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.07.059

41.

Wozniak MA Itzhaki RF Shipley SJ Dobson CB . Herpes simplex virus infection causes cellular beta-amyloid accumulation and secretase upregulation. Neurosci Lett. (2007) 429:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.077

42.

De Chiara G Marcocci ME Civitelli L Argnani R Piacentini R Ripoli C et al . APP processing induced by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) yields several APP fragments in human and rat neuronal cells. PLoS One. (2010) 5:e13989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013989

43.

Li Q Ali MA Cohen JI . Insulin degrading enzyme is a cellular receptor mediating varicella-zoster virus infection and cell-to-cell spread. Cell. (2006) 127:305–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.046

44.

Bernstein HG Keilhoff G Dobrowolny H Steiner J . Binding varicella zoster virus: an underestimated facet of insulindegrading enzyme s implication for Alzheimer s disease pathology?Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2019) 270:495–6. doi: 10.1007/s00406-019-00995-1

45.

Bourgade K Garneau H Giroux G Le Page AY Bocti C Dupuis G et al . beta-amyloid peptides display protective activity against the human Alzheimer’s disease-associated herpes simplex virus-1. Biogerontology. (2015) 16:85–98. doi: 10.1007/s10522-014-9538-8

46.

Eimer WA Vijaya Kumar DK Navalpur Shanmugam NK Rodriguez AS Mitchell T Washicosky KJ et al . Alzheimer’s disease-associated betaamyloid is rapidly seeded by herpesviridae to protect against brain infection. Neuron. (2018) 99:56–63.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.06.030

47.

Cribbs DH Azizeh BY Cotman CW LaFerla FM . Fibril formation and neurotoxicity by a herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B fragment with homology to the Alzheimer’s a beta peptide. Biochemistry. (2000) 39:5988–94. doi: 10.1021/bi000029f

48.

Erkkinen MG Kim M-O Geschwind MD . Clinical neurology and epidemiology of the major neurodegenerative diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. (2018) 10:a033118. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a033118

49.

Simon DK Tanner CM Brundin P . Parkinson disease epidemiology, pathology, genetics, and pathophysiology. Clin Geriatr Med. (2020) 36:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2019.08.002

50.

Beitz JM . Parkinson s disease a review. Front Biosci. (2014) S6:65–74. doi: 10.2741/s415

51.

Spillantini MG Schmidt ML Lee VM Trojanowski JQ Jakes R Goedert M et al . α-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. (1997) 388:839–40. doi: 10.1038/42166

52.

Reeve AK Ludtmann MH Angelova PR Simcox EM Horrocks MH Klenerman D et al . Aggregated α-synuclein and complex I deficiency: exploration of their relationship in differentiated neurons. Cell Death Dis. (2015) 6:e1820. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.166

53.

Ryman SG Vakhtin AA Mayer AR van der Horn HJ Shaff NA Nitschke SR et al . Abnormal cerebrovascular activity, perfusion, and Glymphatic clearance in Lewy body diseases. Mov Disord. (2024) 39:1258–68. doi: 10.1002/mds.29867

54.

Alster P Madetko N Koziorowski D Friedman A . Microglial activation and inflammation as a factor in the pathogenesis of progressive Supranuclear palsy (PSP). Front Neurosci. (2020) 14:893. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00893

55.

Caggiu E Paulus K Arru G Piredda R Sechi GP Sechi LA . Humoral cross reactivity between α-synuclein and herpes simplex-1 epitope in Parkinson's disease, a triggering role in the disease?J Neuroimmunol. (2016) 291:110–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2016.01.007

56.

Zhang Q Duan Q Gao Y He P Huang R Huang H et al . Cerebral microvascular injury induced by Lag3-dependent α-Synuclein fibril endocytosis exacerbates cognitive impairment in a mouse model of α-Synucleinopathies. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2023) 10:e2301903. doi: 10.1002/advs.202301903

57.

Brudek T Lühdorf P Christensen T Hansen HJ Møller-Larsen A . Activation of endogenous retrovirus reverse transcriptase in multiple sclerosis patient lymphocytes by inactivated HSV-1, HHV-6 and VZV. J Neuroimmunol. (2007) 187:147–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.04.003

58.

Jiang T Zhu K Kang G Wu G Wang L Tan Y . Infectious viruses and neurodegenerative diseases: the mitochondrial defect hypothesis. Rev Med Virol. (2024) 34:e2565. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2565

59.

Zandi PP Anthony JC Khachaturian AS Stone SV Gustafson D Tschanz JT et al . Reduced risk of Alzheimer disease in users of antioxidant vitamin supplements. Arch Neurol. (2004) 61:82–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.82

60.

Lal H Cunningham AL Godeaux O Chlibek R Diez-Domingo J Hwang SJ et al . Efficacy of an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. (2015) 372:2087–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501184

61.

Li Y Tian S Ai Y Hu Z Ma C Fu M et al . A nanoparticle vaccine displaying varicella-zoster virus gE antigen induces a superior cellular immune response than a licensed vaccine in mice and non-human primates. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1419634. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1419634

Summary

Keywords

Parkinson’s disease, dementia, meta-analysis, herpes zoster, systematic review, vascular dementia

Citation

Zhang Y, Liu W and Xu Y (2024) Association between herpes zoster and Parkinson’s disease and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 15:1471736. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1471736

Received

28 July 2024

Accepted

14 November 2024

Published

05 December 2024

Volume

15 - 2024

Edited by

Sanjay G. Manohar, University of Oxford, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Piotr Alster, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland

Qingwei Lu, First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Zhang, Liu and Xu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yang Xu, 2282831990@qq.com

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.