Abstract

Background:

Severe autoimmune encephalitis (AE) can cause significant neurological deficits, status epilepticus, status dystonicus, and even death, which can be life-threatening to patients. Accurate risk stratification for severe AE progression is critical for optimizing therapeutic strategies. The comprehensive prediction models for severe AE based on routine clinical data and laboratory indicators remain lacking.

Objective:

To develop and validate a prediction model for severe AE to optimize individualized treatment.

Methods:

We collected clinical data and laboratory examination results from 207 patients with confirmed AE. The study population was divided into development and validation cohort. A prediction model for severe AE was constructed using a nomogram and was rigorously validated both internally and externally. Severe AE was defined as modified Rankin Scale (mRS) > 2 and Clinical Assessment Scale for Encephalitis (CASE) > 4.

Results:

The variables ultimately included in the nomogram for the severe AE predictive model were age, psychiatric and/or behavioral abnormalities, seizures, decreased level of consciousness, cognitive impairment, involuntary movements, autonomic dysfunction, and increased intrathecal IgG synthesis rate. It demonstrated excellent discriminative capacity and calibration through internal-external validation.

Conclusion:

The prediction model has highly feasibility in clinical practice, and holds promise as an important tool for risk assessment and guiding individualized treatment in patients with AE.

1 Introduction

Autoimmune encephalitis (AE) refers to a group of encephalitis mediated by autoimmune mechanisms. It is a rare, potentially disabling, yet treatable condition characterized by heterogeneous clinical manifestations including psychiatric symptoms, cognitive impairment, memory decline, seizures, speech disturbances, motor dysfunction, and alterations in consciousness levels (1). With substantial morbidity and mortality rates that impact patients’ quality of life and impose significant economic burdens on both patients and society (2). AE has garnered increasing attention within the international neurology community. The majority of AE patients respond well to immunotherapy, early diagnosis and timely therapeutic intervention remain critical for optimizing clinical outcomes (3).

Severe AE may can lead to significant neurological deficits, coma, and even death (4). Accurate risk stratification for disease progression is essential for implementing individualized therapeutic strategies. Conventional severity assessment relies on Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission requirements, modified Rankin Scale (mRS), and the clinical assessment scale for autoimmune encephalitis (CASE) (4–8). Previous studies have investigated risk factors associated with severe AE, however, there were limitations that these studies did not cover all types of AE or could not effectively assess risks at the early stage of disease. The anti-NMDAR Encephalitis One-Year Functional Status (NEOS) score, based on five variables (intensive care unit admission, treatment delay >4 weeks, lack of clinical improvement within 4 weeks, abnormal MRI, and CSF white blood cell (WBC) count >20 cells/μL), can be used to predict the risk of poor functional outcomes at 1 year in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis (9). Some other evidences have identified clinical biomarkers including anemia, first-line immunotherapy failure, and elevated CSF interleukin-17a (IL-17a) levels predictors of critical illness progression (3, 10, 11). Nevertheless, in the early stages of hospital admission, there is a lack of comprehensive evaluation indicators for the risk of severe AE. The study integrated clinical manifestations with laboratory test results on admission to construct the first nomogram model for severe AE prediction.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study subjects

We collected data from patients suspected of AE who were admitted to our hospital between February 2012 and May 2022. For each patient, paired serum and CSF samples were tested for neuronal antibodies. Study subjects were rigorously selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria shown in Table 1 and the enrollment process illustrated in Figure 1. A retrospective analysis was conducted on the clinical profiles and laboratory findings of these subjects. The entire cohort was divided into a development cohort and a validation cohort to construct a prediction model for severe AE, followed by internal and external validations.

Table 1

| Inclusion criteria |

|

|

|

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The inclusion and exclusion criteria of study subjects.

AE, autoimmune encephalitis; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CBA, cell-based assay; EEG, electroencephalogram; TBA, tissue-based assay; SELC, small cell lung cancer.

Figure 1

Profile of the inclusion process for study subjects. AE, autoimmune encephalitis; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

2.2 Neuronal antibodies detection

Using the cell-based assay (CBA) method: (1) Commercial CBA kits (FA112d-1005-1, Euroimmun AG, Lübeck, Germany; MT226-16 and MT29916, Pulse Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shaanxi, China) were utilized to detect AE antibodies in both serum and CSF of patients, including anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antibody, anti-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR) antibody, anti-dipeptidyl-peptidase-like protein 6 (DPPX) antibody, anti-gamma-aminobutyric acid-B receptor (GABABR) antibody, anti-leucine-rich glioma-inactivated protein 1 (LGI1) antibody, anti-contactin-associated protein-like 2 (CASPR2) antibody, anti-metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) antibody, anti-IgLON5 antibody, anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody and anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GAD65) antibody. The initial dilution concentration for CSF was 1:1, and for serum, it was 1:10, according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

2.3 Collection of clinical data and laboratory test results

The Case Report Form (CRF) was used to collect medical record information of the study subjects, which mainly included the following contents: Demographic information: including name, gender, and age. Neuronal antibodies detection results: including types of antibodies and their titers. Clinical manifestations: including the presence of prodromal infection symptoms (such as upper respiratory tract infection symptoms, headache, fever, diarrhea, etc.) and whether there was a concurrent tumor. CSF laboratory tests: including intracranial pressure, CSF cell count, CSF protein quantification, and intrathecal IgG synthesis rate. Imaging results: whether cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed abnormalities. Electrophysiological examination: whether electroencephalogram (EEG) results were abnormal. Assessment of disease severity at peak: evaluated using the mRS and the CSAE score.

2.4 Related definitions of the study

Antibody titers: A titer of 1:320 was defined as strongly positive, a titer of 1:100 was defined as positive, and titers of 1:32 and 1:10 were defined as weakly positive. Abnormal cranial MRI: Abnormalities on cranial MRI included high signal lesions on T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (T2 Flair) sequences, highly localized to one or both medial temporal lobes (limbic encephalitis), or multiple lesions involving the gray matter, white matter, or both. Abnormal EEG: EEG findings indicating any of the following conditions including abnormal state changes, focal or diffuse slow waves, slow wave rhythms, epileptiform discharges, or extreme δ brushes. Severe AE: It was defined as mRS > 2 and CASE >4 (8, 12, 13).

2.5 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 software. Categorical variables were described using composition ratios and frequencies, with inter-group comparisons conducted using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. For continuous variables, normality tests were performed. Normally distributed data were described using the mean ± standard deviation (), with inter-group comparisons conducted using independent samples t-tests or ANOVA, and correlation analyses performed using Pearson correlation. Non-normally distributed data were described using the median (minimum, maximum) [M (range)], with inter-group analyses conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test, and correlation analyses performed using Spearman correlation. Binary logistic regression was used for regression analysis of dichotomous variables. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Model construction (nomogram) and internal validation using the Bootstrap method were performed using R software (R version 4.3.0). The following packages were utilized: “rms,” “Hmisc,” “boot,” and “nomogramFormula.”

3 Results

3.1 Baseline characteristics of the study subjects

Initial screening identified 1,000 patients with AE antibodies positivity. After excluding cases with antibody overlap syndrome, unpaired serum and CSF specimens, coexistence of other immune diseases, and incomplete clinical information, a final cohort of 207 patients with confirmed AE was included in this study, which comprised of 109 cases of anti-NMDAR encephalitis, 48 cases of anti-LGI1 encephalitis, 14 cases of anti-GABABR encephalitis, 16 cases of anti-Caspr2 encephalitis, 16 cases of anti-GAD65 encephalitis, and 2 cases each of anti-IgLON5 encephalitis and anti-GFAP encephalitis. Among these patients, 124 were male (58.6%) and 83 were female (41.4%), with no significant intergroup gender distribution differences across antibody-specific subgroups (χ2 = 1.882, p value = 0.757). Comprehensive clinical data encompassing demographics, laboratory parameters (including CSF-WBC, CSF-Pro, intrathecal IgG synthesis rates), neuroimaging (abnormal cranial MRI), neurophysiological findings (abnormal EEG), immunotherapy responsiveness, and paraneoplastic associations are detailed in Table 2. (Note: Anti-IgLON5 and anti-GFAP encephalitis cases were excluded from tabular presentation due to limited sample size [n = 2 each]). Prodromal manifestations occurred in 67 patients (32.4%), presented with prodromal symptoms, primarily including headache, fever, upper respiratory tract infection, and diarrhea. The initial clinical manifestations were most commonly seizures (37.68%), followed by psychiatric and/or behavioral abnormalities (20.77%) and memory decline (13.53%) (Figure 2).

Table 2

| Total (n = 207) |

NMDAR (n = 109) |

LGI1 (n = 48) |

GABABR (n = 14) |

Caspr2 (n = 16) |

GAD65 (n = 16) |

p vaule | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, Male | 124 (58.6) | 67 (61.5) | 27 (56.3) | 10 (71.4) | 9 (56.3) | 8 (50.0) | 0.757 |

| Age | 41 (11–82) | 33 (11–17) | 57 ± 11* | 61 ± 14* | 43 ± 16* | 53 ± 13* | <0.001 |

| Prodromal infection | 67 (32.4) | 49 (45.0) | 7 (14.6) | 2 (14.3) | 5 (31.3) | 4 (25.0) | 0.001 |

| Psychiatric and/or behavioral abnormalities | 113 (54.6) | 79 (72.5) | 21 (43.8) | 6 (42.9) | 4 (25.0) | 1 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Cognitive impairment | 53 (25.6) | 27 (24.8) | 16 (33.3) | 5 (35.7) | 2 (12.5) | 2 (12.5) | 0.287 |

| Memory decline | 89 (43.0) | 41 (37.6) | 32 (66.7) | 8 (57.1) | 5 (31.3) | 1 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Seizures | 123 (59.4) | 70 (64.2) | 37 (77.1) | 10 (71.4) | 3 (18.8) | 1 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Speech disorders | 30 (14.5) | 25 (22.9) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (7.1) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (6.3) | 0.005 |

| Motor dysfunction | 4 (1.9) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.3) | 1 (6.3) | 0.180 |

| Involuntary movement | 18 (8.7) | 8 (7.3) | 6 (12.5) | 0 | 4 (25.0) | 0 | 0.079 |

| Decreased level of consciousness | 30 (14.5) | 24 (22.0) | 3 (6.3) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (6.3) | 0.056 |

| Autonomic dysfunction | 31 (15.0) | 22 (20.2) | 7 (14.6) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 0.246 |

| Focal CNS neurological deficits | 48 (23.2) | 23 (21.1) | 1 (2.1) | 2 (14.3) | 9 (56.3) | 13 (81.3) | <0.001 |

| Urinary and bowel dysfunction | 16 (7.7) | 12 (11.0) | 2 (4.2) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 0.512 |

| ICU Admission | 22 (10.6) | 18 (16.5) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (6.3) | 0.066 |

| Increased ICP | 50 (24.2) | 33 (30.3) | 8 (16.7) | 4 (28.6) | 1 (6.3) | 3 (18.8) | 0.144 |

| Increased CSF-WBC | 107 (51.7) | 66 (60.6) | 19 (39.6) | 8 (57.1) | 9 (56.3) | 4 (25.0) | 0.024 |

| Increased CSF-Pro | 71 (34.3) | 37 (33.9) | 14 (29.2) | 8 (57.1) | 5 (31.3) | 6 (37.5) | 0.431 |

| Increased intrathecal IgG synthesis rate | 51 (24.7) | 28 (25.7) | 9 (18.8) | 5 (35.7) | 5 (31.3) | 4 (25.0) | 0.654 |

| Abnormal cranial MRI | 129 (62.4) | 70 (64.2) | 30 (62.5) | 11 (78.5) | 10 (62.5) | 6 (37.5) | 0.203 |

| Abnormal EEG | 166 (80.2) | 86 (78.9) | 38 (79.2) | 12 (85.7) | 14 (87.5) | 14 (87.5) | 0.906 |

| Associated with tumors | 18 (8.7) | 5 (4.6) | 2 (4.2) | 8 (57.1) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (12.5) | <0.001 |

Baseline characteristics of the study subjects.

For multiple group comparisons, a corrected p value was applied, with p value < 0.01 considered statistically. The bold values indicated statistically significant results.

NMDAR, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor; GABABR, gamma-aminobutyric acid-B receptor; LGI1, leucine-rich glioma-inactivated protein 1; CASPR2, contactin-associated protein-like 2; GAD65, glutamic acid decarboxylase 65; CNS, central nervous system; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CSF-WBC, cerebrospinal fluid white blood cell; CSF-Pro, cerebrospinal fluid protein; EEG, electroencephalogram; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; ICP, intracranial pressure; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 2

Initial clinical manifestations of AE. NMDAR, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor; AMPAR, anti-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor; DPPX, dipeptidyl-peptidase-like protein 6; GABABR, gamma-aminobutyric acid-B receptor; LGI1, leucine-rich glioma-inactivated protein 1; CASPR2, contactin-associated protein-like 2; mGluR5, metabotropic glutamate receptor 5; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; GAD65, glutamic acid decarboxylase 65; CNS, central nervous system.

3.2 Assessment of factors influencing disease severity

The study population was divided into a development cohort comprising 162 cases and a validation cohort consisting of 45 cases (Table 3). This division facilitated the construction of a prediction model for severe AE followed by rigorous validation protocols.

Table 3

| Development cohort (n = 162) | Validation cohort (n = 45) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, Male | 98 (60.5) | 26 (57.8) | 0.864 |

| Age | 43 (11–82) | 44 (13–77) | 0.671 |

| Prodromal infection | 50 (30.9) | 17 (37.8) | 0.471 |

| Clinical manifestation | |||

| Behavioral and psychiatric abnormalities | 94 (58.0) | 19 (42.2) | 0.065 |

| Cognitive impairment | 45 (27.8) | 8 (17.8) | 0.185 |

| Memory decline | 71 (43.8) | 18 (40.0) | 0.734 |

| Epileptic seizures | 102 (63.0) | 21 (46.7) | 0.059 |

| Speech disorders | 23 (14.2) | 7 (15.6) | 0.819 |

| Motor dysfunction | 3 (1.9) | 1 (2.20) | 0.873 |

| Involuntary movement | 13 (8.0) | 5 (11.1) | 0.551 |

| Decreased level of consciousness | 26 (16.0) | 4 (8.9) | 0.227 |

| Dysautonomia | 21 (13.0) | 10 (22.2) | 0.155 |

| Focal CNS damage | 31 (19.1) | 17 (37.8) | 0.011 |

| Sleep disorders | 14 (8.6) | 7 (15.6) | 0.261 |

| ICU admission | 17 (10.5) | 5 (11.1) | 0.905 |

| Increased ICP | 41 (25.3) | 9 (20.0) | 0.557 |

| Increased CSF-WBC | 92 (56.8) | 15 (33.3) | 0.005 |

| Increased CSF-Pro | 56 (34.6) | 15 (33.3) | 0.877 |

| Increased intrathecal IgG synthesis rate | 41 (25.3) | 10 (22.2) | 0.702 |

| Abnormal cranial MRI | 98 (60.5) | 31 (68.9) | 0.358 |

| Abnormal EEG | 130 (80.2) | 36 (80.0) | 0.971 |

| Strongly positive serum AE antibodies | 32 (19.8) | 4 (8.9) | 0.119 |

| Strongly positive CSF AE antibodies | 70 (43.2) | 6 (13.3) | <0.001 |

| Associated with tumors | 17 (10.5) | 1 (2.20) | 0.131 |

Comparison of data between development and validation cohorts.

AE, autoimmune encephalitis; CNS, central nervous system; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CSF-WBC, cerebrospinal fluid white blood cell; CSF-Pro, cerebrospinal fluid protein; EEG, electroencephalogram; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; ICP, intracranial pressure; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

3.2.1 Analysis of factors influencing disease severity based on mRS

Initial univariate analysis of the development cohort (mRS > 2 stratification) identified age (p value = 0.023), psychiatric and/or behavioral abnormalities (p value = 0.002), cognitive impairment (p value = 0.002), autonomic dysfunction (p value = 0.005), and CSF antibody titers (p value = 0.017) as severity-associated factors (Table 4). Multivariate logistic regression (variables with p value < 0.1) demonstrated significant associations with: age: OR 1.03 (95% CI 1.00 - 1.05, p value = 0.021), psychiatric and/or behavioral abnormalities: OR 3.37 (95% CI 1.56 - 7.27, p value = 0.002), cognitive impairment OR 3.36 (95% CI 1.24 - 9.12, p value = 0.017), and autonomic dysfunction: OR 8.89 (95% CI 1.11 - 71.54, p value = 0.040) (Table 5).

Table 4

| mRS ≤ 2 (n = 52) |

mRS > 2 (n = 110) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, Male | 67 (60.9) | 31 (59.6) | >0.999 |

| Age | 38 (12–80) | 45 (11–82) | 0.023 |

| Prodromal infection | 12 (23.1) | 38 (34.5) | 0.150 |

| Clinical manifestation | |||

| Psychiatric and/or behavioral abnormalities | 21 (40.4) | 73 (66.4) | 0.002 |

| Cognitive impairment | 6 (11.5) | 39 (35.5) | 0.002 |

| Memory decline | 25 (48.1) | 46 (41.8) | 0.500 |

| Seizures | 33 (63.5) | 69 (62.7) | >0.999 |

| Speech disorders | 5 (9.6) | 18 (16.4) | 0.337 |

| Motor dysfunction | 1 (1.9) | 2 (1.8) | >0.999 |

| Involuntary movement | 3 (5.8) | 10 (9.1) | 0.552 |

| Decreased level of consciousness | 4 (7.7) | 22 (20.0) | 0.065 |

| Autonomic dysfunction | 1 (1.9) | 20 (18.2) | 0.005 |

| Focal CNS neurological deficits | 7 (13.5) | 24 (21.8) | 0.285 |

| Sleep disorders | 1 (1.9) | 13 (11.8) | 0.068 |

| Increased ICP | 16 (30.8) | 25 (22.7) | 0.333 |

| Increased CSF-WBC | 28 (53.8) | 64 (58.2) | 0.615 |

| Increased CSF-Pro | 12 (23.1) | 44 (40.0) | 0.051 |

| Increased intrathecal IgG synthesis rate | 8 (15.4) | 33 (30.0) | 0.054 |

| Abnormal cranial MRI | 28 (53.8) | 70 (63.6) | 0.302 |

| Abnormal EEG | 43 (82.7) | 87 (79.1) | 0.676 |

| Strongly positive serum AE antibodies | 6 (11.5) | 26 (23.6) | 0.091 |

| Strongly positive CSF AE antibodies | 15 (28.8) | 55 (50.0) | 0.017 |

| Associated with tumors | 2 (3.8) | 15 (13.6) | 0.096 |

Univariate analysis of factors associated with severe AE (based on mRS).

The bold values indicated statistically significant results. AE, autoimmune encephalitis; CNS, central nervous system; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CSF-WBC, cerebrospinal fluid white blood cell; CSF-Pro, cerebrospinal fluid protein; EEG, electroencephalogram; ICP, intracranial pressure; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

Table 5

| OR (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | 0.021 |

| Psychiatric and/or behavioral abnormalities | 3.37 (1.56–7.27) | 0.002 |

| Cognitive impairment | 3.36 (1.24–9.12) | 0.017 |

| Autonomic dysfunction | 8.89 (1.11–71.54) | 0.040 |

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with severe AE (based on mRS).

AE, autoimmune encephalitis; mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

3.2.2 Analysis of factors influencing disease severity based on CASE

Subsequent analysis using CASE >4 stratification revealed additional risk factors: psychiatric and/or behavioral abnormalities (p value <0.001), seizures (p value = 0.004), decreased consciousness level (p value <0.001), autonomic dysfunction (p value = 0.007), increased intrathecal IgG synthesis rate (p value = 0.025), and strong positivity for AE antibodies in CSF (p value = 0.003) (Table 6).

Table 6

| CASE ≤4 (n = 100) |

CASE >4 (n = 62) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, Male | 58 (58.0%) | 40 (64.5%) | 0.509 |

| Age | 40.5 (12–82) | 45 (11–80) | 0.581 |

| Prodromal infection | 35 (35.0%) | 15 (24.2%) | 0.165 |

| Clinical manifestation | |||

| Psychiatric and/or behavioral abnormalities | 46 (46.0%) | 48 (77.4%) | <0.001 |

| Cognitive impairment | 23 (23.0%) | 22 (35.5%) | 0.105 |

| Memory decline | 42 (42.0%) | 29 (46.8%) | 0.626 |

| Seizures | 54 (54.0%) | 48 (77.4%) | 0.004 |

| Speech disorders | 11 (11.0%) | 12 (19.4%) | 0.167 |

| Motor dysfunction | 1 (1.0%) | 2 (3.2%) | 0.559 |

| Involuntary movement | 5 (5.0%) | 8 (12.9%) | 0.082 |

| Decreased level of consciousness | 7 (7.0%) | 19 (30.6%) | <0.001 |

| Autonomic dysfunction | 7 (7.0%) | 14 (22.6%) | 0.007 |

| Focal CNS neurological deficits | 19 (19.0%) | 12 (19.4%) | >0.999 |

| Sleep disorders | 6 (6.0%) | 8 (12.9%) | 0.155 |

| Increased ICP | 24 (24.0%) | 17 (27.4%) | 0.711 |

| Increased CSF-WBC | 53 (53.0%) | 39 (62.9%) | 0.255 |

| Increased CSF-Pro | 33 (33.0%) | 23 (37.1%) | 0.614 |

| Increased intrathecal IgG synthesis rate | 19 (19.0%) | 22 (35.5%) | 0.025 |

| Abnormal cranial MRI | 58 (58.0%) | 40 (64.5%) | 0.509 |

| Abnormal EEG | 80 (80.0%) | 50 (80.6%) | >0.999 |

| Strongly positive serum AE antibodies | 17 (17.0%) | 15 (24.2%) | 0.312 |

| Strongly positive CSF AE antibodies | 34 (34.0%) | 36 (58.1%) | 0.003 |

| Associated with tumors | 9 (9.0%) | 8 (12.9%) | 0.599 |

Univariate analysis of factors associated with severe AE (based on CASE).

The bold values indicated statistically significant results. AE, autoimmune encephalitis; CASE, clinical assessment scale for autoimmune encephalitis; CNS, central nervous system; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CSF-WBC, cerebrospinal fluid white blood cell; CSF-Pro, cerebrospinal fluid protein; EEG, electroencephalogram; ICP, intracranial pressure; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Variables with p value <0.1 were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. The results showed that psychiatric and/or behavioral abnormalities OR 3.70 (95% CI 1.67–8.16, p value = 0.001), seizures OR 6.07 (95% CI 2.42–15.22, p value <0.001), involuntary movement OR 4.23 (95% CI 1.00–17.84, p value = 0.049), decreased level of consciousness OR 6.80 (95% CI 2.18–21.21, p value = 0.001), and increased intrathecal IgG synthesis rate OR 3.05 (95% CI 1.23–7.50, p value = 0.015) were associated with the severity of AE (Table 7).

Table 7

| OR (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric and/or behavioral abnormalities | 3.70 (1.67–8.16) | 0.001 |

| Seizures | 6.07 (2.42–15.22) | <0.001 |

| Involuntary movement | 4.23 (1.00–17.84) | 0.049 |

| Decreased level of consciousness | 6.80 (2.18–21.21) | 0.001 |

| Increased intrathecal IgG synthesis rates | 3.05 (1.23–7.50) | 0.015 |

Multivariate analysis of severe AE (based on CASE).

AE, autoimmune encephalitis; CASE, clinical assessment scale for autoimmune encephalitis.

3.3 Severe AE prediction model

3.3.1 Construction of a severe AE prediction model

In this study, severe AE was defined as an mRS > 2 and CASE >4. A nomogram method was employed to construct a predictive model for severe AE by incorporating variables with statistical significance (p value <0.05) from the multivariate analysis. The variables included age, psychiatric and/or behavioral abnormalities, seizures, decreased level of consciousness, cognitive impairment, involuntary movements, autonomic dysfunction, and increased intrathecal IgG synthesis rate. As shown in Figure 3, vertical lines drawn on the scale lines representing each influencing factor yield individual scores for each factor. The total score is obtained by summing the scores of the eight influencing factors. A vertical line plotted on the final axis corresponds to the predicted probability of severe AE.

Figure 3

Prediction model for severe AE (nomogram).

3.3.2 The internal validation of the severe AE prediction model

The efficacy of the prediction model was determined by plotting the ROC curve analysis. In the development cohort, the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.824 (95% CI: 0.752–0.896), with a sensitivity of 0.820 and specificity of 0.752, p vaule <0.001 (Figure 4A). For internal validation using the Bootstrap method, after performing 1,000 resamples, the ROC curve was plotted again, the AUC was 0.824 (95% CI: 0.752–0.896), with a sensitivity of 0.836 and specificity of 0.733, p value <0.001 (Figure 4B). The nomogram prediction model was calibrated by comparing the predicted probabilities of severe AE with the actual diagnosis probabilities after bias correction. There was good consistency between the predicted and actual probabilities, indicating that the prediction model was well-calibrated (Figure 4C).

Figure 4

ROC and calibration curves of the severe AE prediction model. (A) ROC curve of the prediction model in the development cohort. (B) ROC curve of the prediction model after internal validation using the Bootstrap method. (C) Calibration curve of the prediction model in the development cohort.

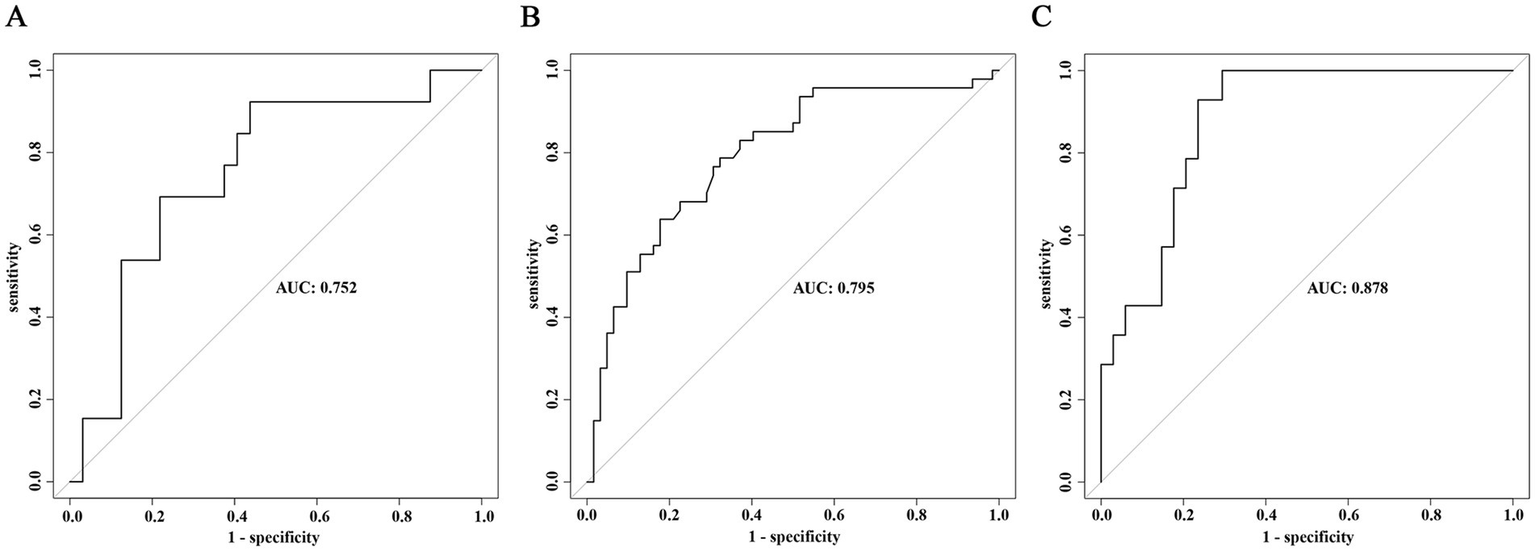

3.3.3 External validation of the severe AE prediction model

The external validation of the model was divided into three parts. First, external validation was performed using 45 patients from the validation cohort, resulting in an AUC of 0.756 (95% CI 0.593–0.912), p value = 0.002 (Figure 5A). Additionally, to evaluate the model’s predictive efficacy for severe AE associated with different antibody types, external validation was conducted separately on the 109 cases of anti-NMDAR encephalitis and 48 cases of anti-LGI1 encephalitis included in this study. The results showed that for the anti-NMDAR antibody encephalitis cohort, the AUC was 0.795 (95% CI 0.709–0.881), p value <0.001 (Figure 5B), and for the anti-LGI1 encephalitis cohort, the AUC was 0.878 (95% CI 0.784–0.972), p value <0.001 (Figure 5C).

Figure 5

External validation of the prediction model for severe AE. (A) ROC curve of the predictive model in the overall validation cohort. (B) ROC curve of the predictive model in the validation cohort for anti-NMDAR encephalitis. (C) ROC curve of the predictive model in the validation cohort for anti-LGI1 encephalitis.

4 Discussion

AE represents a rare neuroimmunological disorder characterized by acute to subacute neuropsychiatric manifestations and significant disability rates (2). Recent advancements in autoantibody detection techniques have facilitated substantial progress in AE research. While immunotherapy demonstrates efficacy in many cases, 11.2–55.0% of patients progress to severe disease (14–16), often complicated by respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation (17), hemodynamic instability caused by severe autonomic dysfunction (18, 19), status dystonicus (SD) (20), coma, and status epilepticus (SE) (4, 21), which can be life-threatening to patients. Early intervention (within 8 days) with combined steroid pulse therapy and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has been established as an independent predictor of favorable outcomes, while antibody testing for various causes of encephalopathy need to be prior to initiation of immunotherapy (22–24). Accurate risk stratification for severe AE progression is therefore critical for optimizing therapeutic strategies. Despite some studies on disease progression prediction factors in AE (25–27), a systematic, large-scale data-based study to construct a prediction model for severe AE in the early stages of patient admission remains lacking. Our study retrospectively analyzed the clinical data and laboratory examination results of 207 AE cases, constructed a comprehensive prediction model for severe AE, demonstrating excellent discriminative capacity and calibration through rigorous validation. The included variables comprised psychiatric and/or behavioral abnormalities, seizures, decreased level of consciousness, cognitive impairment, involuntary movements, associated with tumors, and increased intrathecal IgG synthesis rate. The mRS score focuses on the overall functional status of patients but lacks the assessment of non-motor symptoms, while the CASE score addresses this limitation, however, its incorporation of laboratory indicators is insufficient. Therefore, in our study, the assessment of disease severity integrated both of the scales, avoiding the bias associated with the use of a single scoring system, which is one of the strengths of our model. Moreover, this is the first nomogram prediction model for severe AE, constructed based on indicators obtained in the early stages of patient admission, thereby ensuring high timeliness. Previous studies have predominantly focused on indicators such as ICU admission, delayed treatment beyond 4 weeks, no clinical improvement within 4 weeks and so on, which were mostly related to the treatment phases. Our model is capable of predicting the risk of severe disease in AE patients at the early admission stage, providing a significant advantage for early intervention and management. The prediction model is expected to be used for future individualized treatment guidance.

The analysis revealed that age was significantly associated with disease severity, consistent with previous reports indicating poorer short-term outcomes in elderly patients (28). This association may be attributed to the higher prevalence of comorbidities in older individuals, as well as the advanced average age of patients with anti-GABABR encephalitis and anti-LGI1 encephalitis. Notably, anti-GABABR encephalitis is frequently associated with tumors, contributing to its relatively worse prognosis. Cognitive impairment was also identified as a significant factor influencing disease severity, aligning with prior studies (29, 30). This may be explained by the fact that patients with cognitive impairment often require increased caregiving support, leading to higher mRS scores. Approximately 50% of severe AE patients exhibited autonomic dysfunction (17), with urinary incontinence/retention being the primary manifestation of autonomic or central nervous system injury. A study of 70 AE patients similarly highlighted urinary incontinence as a predictor of poor prognosis (31), and our findings further confirmed a strong correlation between autonomic dysfunction and AE severity. Additionally, ICU admission was an independent risk factor for poor disease prognosis (9, 32).

In this study, the univariate analysis of the correlation between AE antibody titers and disease severity found that CSF antibody titers were associated with disease severity, whereas serum antibody titers showed no such correlation. However, logistic regression analysis did not identify a statistically significant relationship between antibody titers and disease severity. Consistent with multiple international studies, the association between AE antibody titers and disease severity remains controversial (33–35). A previous study demonstrated that CSF antibody titers were positively correlated with ICU admission, ventilator use, and the presence of concurrent tumors. Furthermore, the study suggested that these three indicators could reflect disease severity. However, no direct correlation was found between CSF antibody titers and prognosis (35). The continuous intrathecal synthesis of neuronal antibodies does not necessarily indicate that encephalitis is in an active phase, and the antibodies titers cannot directly reflect the severity of the condition. Moreover, in CSF analysis, it has been observed that the intrathecal IgG synthesis rate may correlate with the severity of the disease. Although CSF-protein levels and CSF-WBC counts show no statistical significance, previous studies suggest that these parameters often increase within a few days after the onset of neurological symptoms (36). Therefore, monitoring the dynamic changes in CSF components could provide meaningful insights into the progression of the disease.

SE represents a common severe AE manifestation (4, 37, 38), and conventional antiepileptic drugs available in clinical practice are ineffective for approximately one-third of epilepsy patients. The combination of ketogenic diet and stiripentol appeared to constitute effective treatment in SE caused by anti-NMDAR encephalitis (39). SE often accompanied by characteristic EEG abnormalities such as excessive beta activity and extreme delta brush (40). Therefore, EEG monitoring is highly necessary. Although our study did not find a correlation between SE and disease severity, we consider this result to be due to the lack of distinction in seizure types and the degree of EEG abnormalities in our analysis. We recommend long-term EEG monitoring to promptly detect the occurrence of epilepsy. Similarly, no significant correlation was found between cranial MRI abnormalities and disease severity in our study. The absence of cranial MRI-severity correlation in our study contrasts with pediatric cohort findings (41), but aligns with adult studies (29, 42, 43). Furthermore, regarding the tumors associated with AE, anti-NMDAR encephalitis is most commonly associated with ovarian teratomas, while anti-AMPAR encephalitis may be related to thymomas, small cell lung cancer (SCLC), and breast cancer (44). Approximately 50% of patients with anti-GABABR encephalitis are associated with SCLC, which is an important factor for poor prognosis (45, 46). While anti-LGI1 and anti-CASPR2 antibody encephalitis may be associated with thymoma (47, 48). Our study found an association between the presence of tumors and high mRS scores. There has a previous case report of anti-NMDAR encephalitis with bilateral ovarian teratomas supported this conclusion. The patient’s clinical condition rapidly improved following total enucleation of the bilateral ovaries (49). This highlights the importance of comprehensive tumor screening and early surgical intervention when feasible in the treatment of AE.

This study introduces the first nomogram-based prediction model for severe AE, demonstrating excellent discriminative capacity and calibration through rigorous validation. The model’s clinical utility is enhanced by its reliance on readily available parameters. However, several limitations warrant consideration. The single-center retrospective design limited the rare AE subtype representation and ethnic homogeneity (Chinese cohort), which needs more diverse study populations to further validate the generalizability of the conclusions.

5 Conclusion

This study has constructed a comprehensive prediction model for severe AE using a variety of readily available clinical indicators. Following rigorous internal-external validation, this model demonstrated excellent performance, enabling personalized risk stratification and therapeutic optimization for AE patients.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Tongren Hospital, Capital Medical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

ZX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LL: Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. EH: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 82271384).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank to our research team for their hard work and dedication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Graus F Titulaer MJ Balu R Benseler S Bien CG Cellucci T et al . A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. (2016) 15:391–404. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(15)00401-9

2.

Granerod J Ambrose HE Davies NW Clewley JP Walsh AL Morgan D et al . Causes of encephalitis and differences in their clinical presentations in England: a multicentre, population-based prospective study. Lancet Infect Dis. (2010) 10:835–44. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(10)70222-x

3.

Broadley J Wesselingh R Seneviratne U Kyndt C Beech P Buzzard K et al . Peripheral immune cell ratios and clinical outcomes in seropositive autoimmune encephalitis: a study by the Australian autoimmune encephalitis consortium. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:597858. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.597858

4.

Schubert J Brämer D Huttner HB Gerner ST Fuhrer H Melzer N et al . Management and prognostic markers in patients with autoimmune encephalitis requiring Icu treatment. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. (2019) 6:e514. doi: 10.1212/nxi.0000000000000514

5.

Wu C Fang Y Zhou Y Wu H Huang S Zhu S . Risk prediction models for early Icu admission in patients with autoimmune encephalitis: integrating scale-based assessments of the disease severity. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:916111. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.916111

6.

Fan M Sun W Chen D Dong T Yan W Zhang M et al . Severity of hospitalized children with anti-Nmdar autoimmune encephalitis. J Child Neurol. (2022) 37:749–57. doi: 10.1177/08830738221075886

7.

Zhou H Deng Q Yang Z Tai Z Liu K Ping Y et al . Performance of the clinical assessment scale for autoimmune encephalitis in a pediatric autoimmune encephalitis cohort. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:915352. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.915352

8.

Lim JA Lee ST Moon J Jun JS Kim TJ Shin YW et al . Development of the clinical assessment scale in autoimmune encephalitis. Ann Neurol. (2019) 85:352–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.25421

9.

Balu R McCracken L Lancaster E Graus F Dalmau J Titulaer MJ . A score that predicts 1-year functional status in patients with anti-Nmda receptor encephalitis. Neurology. (2019) 92:e244–52. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000006783

10.

Broadley J Wesselingh R Seneviratne U Kyndt C Beech P Buzzard K et al . Prognostic value of acute cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in antibody-positive autoimmune encephalitis. J Neuroimmunol. (2021) 353:577508. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2021.577508

11.

Levraut M Bourg V Capet N Delourme A Honnorat J Thomas P et al . Cerebrospinal fluid Il-17a could predict acute disease severity in non-Nmda-receptor autoimmune encephalitis. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:673021. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.673021

12.

Nosadini M Eyre M Molteni E Thomas T Irani SR Dalmau J et al . Use and safety of immunotherapeutic management of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antibody encephalitis: a Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. (2021) 78:1333–44. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.3188

13.

Liu Z Li Y Wang Y Zhang H Lian Y Cheng X . The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratios are independently associated with the severity of autoimmune encephalitis. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:911779. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.911779

14.

Yeshokumar AK Gordon-Lipkin E Arenivas A Cohen J Venkatesan A Saylor D et al . Neurobehavioral outcomes in autoimmune encephalitis. J Neuroimmunol. (2017) 312:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.08.010

15.

Cai MT Lai QL Zheng Y Fang GL Qiao S Shen CH et al . Validation of the clinical assessment scale for autoimmune encephalitis: a multicenter study. Neurol Ther. (2021) 10:985–1000. doi: 10.1007/s40120-021-00278-9

16.

Zhang Y Tu E Yao C Liu J Lei Q Lu W . Validation of the clinical assessment scale in autoimmune encephalitis in Chinese patients. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:796965. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.796965

17.

Schwarz L Akbari N Prüss H Meisel A Scheibe F . Clinical characteristics, treatments, outcome, and prognostic factors of severe autoimmune encephalitis in the intensive care unit: standard treatment and the value of additional plasma cell-depleting escalation therapies for treatment-refractory patients. Eur J Neurol. (2023) 30:474–89. doi: 10.1111/ene.15585

18.

Yan L Zhang S Huang X Tang Y Wu J . Clinical study of autonomic dysfunction in patients with anti-Nmda receptor encephalitis. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:609750. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.609750

19.

Chen Z Zhang Y Wu X Huang H Chen W Su Y . Characteristics and outcomes of paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity in anti-Nmdar encephalitis. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:858450. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.858450

20.

Zhang Y Cui L Chen W Huang H Liu G Su Y et al . Status Dystonicus in adult patients with anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate-acid receptor encephalitis. J Neurol. (2023) 270:2693–701. doi: 10.1007/s00415-023-11599-0

21.

Zhang Y Huang HJ Chen WB Liu G Liu F Su YY . Clinical efficacy of plasma exchange in patients with autoimmune encephalitis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. (2021) 8:763–73. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51313

22.

de Montmollin E Demeret S Brulé N Conrad M Dailler F Lerolle N et al . Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis in adult patients requiring intensive care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2017) 195:491–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201603-0507OC

23.

Abboud H Probasco JC Irani S Ances B Benavides DR Bradshaw M et al . Autoimmune encephalitis: proposed best practice recommendations for diagnosis and acute management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2021) 92:757–68. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-325300

24.

Uchida Y Kato D Adachi K Toyoda T Matsukawa N . Passively acquired thyroid autoantibodies from intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune encephalitis: two case reports. J Neurol Sci. (2017) 383:116–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.11.002

25.

Esposito S Principi N Calabresi P Rigante D . An evolving redefinition of autoimmune encephalitis. Autoimmun Rev. (2019) 18:155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.08.009

26.

Dalmau J Graus F . Antibody-mediated encephalitis. N Engl J Med. (2018) 378:840–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1708712

27.

Kang Q Liao H Yang L Fang H Hu W Wu L . Clinical characteristics and short-term prognosis of children with antibody-mediated autoimmune encephalitis: a single-center cohort study. Front Pediatr. (2022) 10:880693. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.880693

28.

Dong X Zheng D Nao J . Clinical characteristics and factors associated with short-term prognosis in adult patients with autoimmune encephalitis of non-neoplastic etiology. Neurol Sci. (2019) 40:1567–75. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-03883-7

29.

Wang W Li JM Hu FY Wang R Hong Z He L et al . Anti-Nmda receptor encephalitis: clinical characteristics, predictors of outcome and the knowledge gap in Southwest China. Eur J Neurol. (2016) 23:621–9. doi: 10.1111/ene.12911

30.

Sun Y Ren G Ren J Shan W Han X Lian Y et al . A validated nomogram that predicts prognosis of autoimmune encephalitis: a multicenter study in China. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:612569. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.612569

31.

Liao S Qian Y Hu H Niu B Guo H Wang X et al . Clinical characteristics and predictors of outcome for onconeural antibody-associated disorders: a retrospective analysis. Front Neurol. (2017) 8:584. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00584

32.

Chi X Wang W Huang C Wu M Zhang L Li J et al . Risk factors for mortality in patients with anti-Nmda receptor encephalitis. Acta Neurol Scand. (2017) 136:298–304. doi: 10.1111/ane.12723

33.

Gresa-Arribas N Titulaer MJ Torrents A Aguilar E McCracken L Leypoldt F et al . Antibody Titres at diagnosis and during follow-up of anti-Nmda receptor encephalitis: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. (2014) 13:167–77. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70282-5

34.

Broadley J Seneviratne U Beech P Buzzard K Butzkueven H O'Brien T et al . Prognosticating autoimmune encephalitis: a systematic review. J Autoimmun. (2019) 96:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.10.014

35.

Gu Y Zhong M He L Li W Huang Y Liu J et al . Epidemiology of antibody-positive autoimmune encephalitis in Southwest China: a multicenter study. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:2611. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02611

36.

Armangue T Titulaer MJ Málaga I Bataller L Gabilondo I Graus F et al . Pediatric anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis-clinical analysis and novel findings in a series of 20 patients. J Pediatr. (2013) 162:850–856.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.10.011

37.

Wang B Wang C Feng J Hao M Guo S . Clinical features, treatment, and prognostic factors in neuronal surface antibody-mediated severe autoimmune encephalitis. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:890656. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.890656

38.

Wang X Wan J Wei Z Song C Kang X Du F et al . Status epilepticus in patients with anti-Nmdar encephalitis requiring intensive care: a follow-up study. Neurocrit Care. (2022) 36:192–201. doi: 10.1007/s12028-021-01283-4

39.

Uchida Y Kato D Toyoda T Oomura M Ueki Y Ohkita K et al . Combination of ketogenic diet and Stiripentol for super-refractory status epilepticus: a case report. J Neurol Sci. (2017) 373:35–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.12.020

40.

Jeannin-Mayer S André-Obadia N Rosenberg S Boutet C Honnorat J Antoine JC et al . Eeg analysis in anti-Nmda receptor encephalitis: description of typical patterns. Clin Neurophysiol. (2019) 130:289–96. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2018.10.017

41.

Bartels F Krohn S Nikolaus M Johannsen J Wickström R Schimmel M et al . Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging outcome predictors in pediatric anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. Ann Neurol. (2020) 88:148–59. doi: 10.1002/ana.25754

42.

Wang R Lai XH Liu X Li YJ Chen C Li C et al . Brain magnetic resonance-imaging findings of anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis: a cohort follow-up study in Chinese patients. J Neurol. (2018) 265:362–9. doi: 10.1007/s00415-017-8707-5

43.

Lei C Chang X Li H Zhong L . Abnormal brain Mri findings in anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis and correlation with outcomes. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:834929. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.834929

44.

Höftberger R van Sonderen A Leypoldt F Houghton D Geschwind M Gelfand J et al . Encephalitis and Ampa receptor antibodies: novel findings in a case series of 22 patients. Neurology. (2015) 84:2403–12. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000001682

45.

Höftberger R Titulaer MJ Sabater L Dome B Rózsás A Hegedus B et al . Encephalitis and Gabab receptor antibodies: novel findings in a new case series of 20 patients. Neurology. (2013) 81:1500–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a9585f

46.

Feng X Zhang Y Gao Y Zhang J Yu S Lv J et al . Clinical characteristics and prognosis of anti-Γ-aminobutyric acid-B receptor encephalitis: a single-center, longitudinal study in China. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:949843. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.949843

47.

Binks SNM Klein CJ Waters P Pittock SJ Irani SR . Lgi1, Caspr2 and related antibodies: a molecular evolution of the phenotypes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2018) 89:526–34. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-315720

48.

Lai M Huijbers MG Lancaster E Graus F Bataller L Balice-Gordon R et al . Investigation of Lgi1 as the antigen in limbic encephalitis previously attributed to potassium channels: a case series. Lancet Neurol. (2010) 9:776–85. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(10)70137-x

49.

Uchida Y Kato D Yamashita Y Ozaki Y Matsukawa N . Failure to improve after ovarian resection could be a marker of recurrent ovarian Teratoma in anti-Nmdar encephalitis: a case report. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2018) 14:339–42. doi: 10.2147/ndt.S156603

Summary

Keywords

autoimmune encephalitis, severe, prediction model, risk stratification, individualized treatment

Citation

Xie Z, Zhang J, Liu L, Hu E and Wang J (2025) Prediction model for severe autoimmune encephalitis: a tool for risk assessment and individualized treatment guidance. Front. Neurol. 16:1575835. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1575835

Received

13 February 2025

Accepted

05 March 2025

Published

18 March 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Qi Zhang, Yale University, United States

Reviewed by

Yuto Uchida, Johns Hopkins Medicine, United States

Zixi Yin, Yale University, United States

Qian Zhang, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Xie, Zhang, Liu, Hu and Wang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jiawei Wang, wangjwcq@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.