Abstract

Background:

Ischemic stroke represents the most prevalent form of cerebrovascular disease, which has a significant impact on people’s quality of life. Selenium is a crucial trace mineral with potential relevance for the prevention of cerebrovascular disease due to its antioxidant properties. Recent research has increasingly linked circulating selenium levels to the incidence of ischemic stroke, however, the findings remained inconsistent. The primary objective of our meta-analysis is to explore the potential relationship between circulating selenium levels and stroke as well as stroke mortality. In the meantime, the current study was done to evaluate the influence of dietary selenium intake on the risk of stroke.

Methods:

A comprehensive systematic search of electronic databases was conducted from inception through April 11, 2025, to identify relevant studies investigating the associations between circulating selenium levels, dietary selenium intake and ischemic stroke risk. Ultimately, 26 eligible studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Results:

(1) The aggregated weighted mean difference (WMD) demonstrated that circulating selenium concentrations were markedly reduced in the ischemic stroke cohort relative to the control cohort (WMD = −0.13 [−0.20, −0.07]). (2) The multivariable-adjusted relative risk (RR) indicated that increased circulating selenium levels linked to a notable decrease in the risk of ischemic stroke (RR = 0.88 [0.83,0.92]), as well as a decreased risk of stroke mortality (RR = 0.86 [0.80, 0.93]). (3) Furthermore, our meta-analysis found that increased dietary selenium intake was adversely correlated with the risk of stroke, with RR of 0.87(0.76, 0.99). (4) A meta-analysis of dose–response curves revealed that circulating selenium levels were adversely linked with stroke.

Conclusion:

The level of circulation selenium is lower in ischemic stroke patients. There was an inverse association between the level of circulation selenium and the incidence of ischemic stroke as well as stroke mortality. Meanwhile, higher dietary selenium intake were shown to be negatively associated with ischemic stroke.

Introduction

To our knowledge, stroke is globally recognized as the third major contributor to disability and the second leading cause of death, resulting in increasing socioeconomic burdens (1, 2). According to current forecasts, by 2030, there will be a 20.5% rise in the prevalence of strokes compared to 2012 (2). Reducing stroke risk is an urgent priority, and identifying modifiable risk factors is essential for prevention and treatment. Over 90% of strokes worldwide are linked to controllable factors, including cardio-metabolic diseases, smoking, and unhealthy dietary habits (3–5). Consequently, the identification of novel risk factors are essential for reducing stroke risk. Among potential modifiable factors, nutritional determinants have emerged as increasingly prominent targets for stroke prevention.

The pathophysiology of ischemic stroke involves multiple interconnected pathways, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and ionic imbalances. Current evidence particularly highlights oxidative stress as a central mediator in stroke pathophysiology (6). Selenium (Se) is a vital trace element with antioxidant capabilities for humans and is a natural dietary component (7), serving as an important regulator of brain function. It is believed that the antioxidant capabilities of selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidases (GPxs) provide cardio protection (8, 9). The neuroprotective action of Se may be achieved through controlling of selenium-containing antioxidants, cell signaling pathways and activation of transcription factors (10–13). However, results from experimental and observational investigations on the correlation between circulating selenium concentrations and incidence and mortality of cerebrovascular disorders were inconsistent (14–18). Some investigations have revealed that selenium is negatively correlated with the incidence of stroke (15, 16). Notably, some studies have failed to demonstrate a clinically meaningful association between elevated selenium levels and decreased stroke risk (14, 18).

Consequently, numerous studies (14–18), including systematic reviews, have investigated the relationship between selenium and cerebrovascular diseases. A systematic review by Kuria et al. (19) demonstrated that higher circulating selenium levels were associated with reduced incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease compared to lower levels, confirming its protective role. Their study also revealed a statistically significant non-linear dose-response relationship between selenium levels and cardiovascular disease mortality. Although this evidence established a link with cardiovascular outcomes, it did not specifically address the association with stroke. In 2021, Ding and Zhang (20) published a systematic review incorporating 12 observational studies, which revealed an inverse correlation between circulating selenium levels and stroke. This association was further corroborated in cross-sectional/case–control studies and specifically within investigations measuring whole blood selenium. Although this review established a link with circulating selenium, it did not perform a dose–response analysis. Furthermore, it focused exclusively on circulating biomarkers and did not investigate the relationship between dietary selenium intake and stroke. Although previous meta-analyses have linked circulating selenium to stroke, key limitations persist. Firstly, the relationship between dietary selenium intake (a modifiable risk factor) and stroke lacks conclusive evidence and has not been systematically assessed in a meta-analysis. Secondly, the recent publication of numerous new cohort studies justifies an updated and more robust analysis. Lastly, previous reviews have not addressed dose–response relationships. To bridge these gaps, this study aims to: (1) quantify the association between dietary selenium and stroke risk; (2) investigate the dose–response relationship; and (3) compare these findings with evidence on circulating selenium.

Materials

Search strategy and study selection

A thorough literature search was carried out from the beginning to April 11, 2025, using MEDLINE, PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and the EMBASE databases. Additional records were acquired from Google Scholar’s, reference list of included studies and potentially related articles, which were not detected during the literature search. In the search technique, the following search phrases and keywords were linked by “and” or “or”: ischemic stroke, cerebral infarction, cerebrovascular illness, selenium, trace elements, and microelements. Two writers independently chose publications from the resulting list, screening the article titles and abstracts. The articles that passed the screening were thoroughly reviewed in full text based on the eligibility criteria. The study was done using the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) standard (21) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline.

Methods

Data extraction and study quality

Inclusion criteria

The search methodology was confined to publicly accessible data and articles in the English language. Publications were selected according to the following criteria: (1) The studies were prospective cohort studies and case–control studies; (2) they examined the relationship between selenium and cerebral infarction, ischemic stroke, or cerebrovascular disease; (3) they provided relative risk (RR), odds ratio (OR), or weighted mean difference (WMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The research investigating the correlation between dietary selenium and stroke necessitated the following criteria: (1) The research was either a prospective cohort study or a case–control study; (2) it assessed the correlation between dietary selenium consumption and stroke risk; (3) the primary outcome was stroke; and (4) the study presented relative risk estimates or odds ratios with a 95% confidence interval in case–control studies.

Exclusion criteria

Two reviewers independently retrieved data from pertinent articles utilizing data extraction forms that encompassed details such as authorship, publication year, research design, sample size, various biomarker levels, and patient outcomes. We excluded: (1) duplicate or irrelevant papers; (2) reviews, letters, or case reports; (3) non-original research (editorials, reviews, or commentaries); and (4) studies involving non-human subjects.

Data extraction

The gathered information includes the first author, publication year, location, age, gender, sample size, study methodology, exposure category, effect estimates, and modifications. The impact estimates corrected for the maximum number of confounding factors, together with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for the comparison between the highest and lowest circulating selenium levels, were obtained. Additionally, the circulating selenium levels (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) were obtained for both stroke and control patients. Conversely, the unit of circulating selenium was standardized to “umol/L” throughout all trials. Research on dietary selenium and stroke evaluated the following elements: methods for assessing selenium intake, relative risk (RR) and related confidence intervals (CI) for stroke at maximum and minimum levels, and the factors controlled in the research. All studies reporting whole blood selenium were cross-sectional in nature. In all cohort studies, serum/plasma selenium served as the exposure variable. The assessment methods for selenium intake included in the study are shown in Table 1. Consequently, sensitivity analysis was performed for cross-sectional/case–control studies and for serum/plasma selenium investigations, respectively.

Table 1

| Study and year | Country | Study type | N total | Case (umol/L) | Control (umol/L) | RR (stroke or death) | Se biomarker | Quality-NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selenium and stroke | ||||||||

| Hu et al. (2017) (35) | Canada | Cross-sectional | 2,077 | 3.29 ± 0.13 | 4.04 ± 0.03 | 0.17 (0.06, 0.48) | Whole blood | 9 |

| Angelova et al. (2008) (29) | Bulgaria | Case–control | 85 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | NA | Serum | 8 |

| Koyama et al. (2009) (32) | Japan | Case–control | 60 | 1.33 ± 0.25 | 1.47 ± 0.21 | 0.28 (0.10, 0.85) | Whole blood | 7 |

| Hu CHMS et al. (2019) (44) | Canada | Prospective | 7,065 | 2.29 ± 0.03 | 2.49 ± 0.01 | 0.38 (0.15, 0.92) | Whole blood | 9 |

| Hu NHANES et al. (2019) (44) | Canada | Prospective | 5,030 | 2.29 ± 0.03 | 2.44 ± 0.01 | 0.57 (0.13, 1.03) | Whole blood | 9 |

| Nahan et al. (2017) (30) | USA | Case–control | 75 | 2.38 ± 0.18 | 2.63 ± 0.11 | NA | Plasma | 6 |

| Skalny et al. (2017) (33) | Russia | Case–control | 60 | 1.43 ± 0.05 | 1.24 ± 0.07 | NA | Serum | 7 |

| Wen et al. (2019) (46) | China | Case–control | 2,554 | 1.03 ± 0.05 | 1.23 ± 0.06 | 0.10 (0.06, 0.17) | Plasma | 7 |

| Schomburg et al. (2019) (43) | Germany | Prospective | 4,366 | – | – | 1.57 (1.21, 2.02) | Plasma | 8 |

| 1.51 (1.32, 1.72) | Plasma | |||||||

| Xiao et al. (2019) (36) | China | Prospective | 29,763 | – | – | 0.74 (0.50, 1.10) | Plasma | 8 |

| Mirończuk et al. (2021) (28) | Poland | Case–control | 210 | 0.73 ± 0.06 | 0.96 ± 0.06 | NA | Serum | 8 |

| Hu et al. (2021) (16) | China | Case–control | 2,510 | 1.1 ± 0.24 | 1.11 ± 0.24 | 0.78 (0.6, 0.99) | Plasma | 7 |

| Fang et al. (2022) (18) | China | Case–control | 9,639 | – | – | 0.968 (0.914, 1.026) | Serum | 8 |

| Wang et al. (2022) (15) | China | Case–control | 1,236 | 1.06 ± 0.25 | 1.08 ± 0.26 | 0.50 (0.31, 0.80) | Plasma | 8 |

| Wang et al. (2022) (31) | China | Case–control | 3,808 | 0.83 ± 0.04 | 0.84 ± 0.04 | 0.86 (0.76, 0.96) | Plasma | 8 |

| Kok et al. (1987) (34) | Netherlands | Case–control | 10,532 | 1.46 ± 0.06 | 1.6 ± 0.01 | 0.5 (0.2, 1.25) | Serum | 7 |

| 3.2 (0.8, 12.1) | Serum | |||||||

| Marniemi et al. (2005) (14) | Finland | Cohort | 755 | 1.93 ± 0.03 | 1.83 ± 0.01 | 1.66 (0.87, 3.17) | Serum | 9 |

| Chang et al. (1998) (17) | Taiwan | Case–control | 57 | 2.7 ± 0.13 | 2.9 ± 0.14 | NA | Plasma | 7 |

| Wei et al. (2004) (48) | China | Prospective | 1,103 | NA | NA | 0.99 (0.88, 1.11) | Serum | 8 |

| Ray et al. (2006) (47) | USA | Cohort | 632 | 1.43 ± 0.02 | 1.54 ± 0.01 | 0.71 (0.56, 0.90) | Serum | 6 |

| Shi et al. (2022) (37) | China | Cohort | 6,155 | NA | NA | 0.68 (0.56, 0.83) | Plasma | 8 |

| Dietary selenium intake | ug/d | Method of dietary assessment of selenium intake | ||||||

| Zhang et al. (2023) (57) | China | Cohort | 11,532 | Quartile 2 | 29.9–38.53 | 0.85 (0.59, 1.21) | Three consecutive 24-h dietary recalls were used to assess dietary intake of participating individuals. Food consumption data were converted into the dietary selenium intake using Chinese Food Composition Tables (FCTs) | |

| Quartile 3 | 38.53–47.23 | 0.62 (0.42, 0.92) | ||||||

| Quartile 4 | 47.23–60.38 | 0.43 (0.28, 0.68) | ||||||

| Quartile 5 | >60.38 | 0.49 (0.30, 0.82) | ||||||

| Shi et al. (2022) (53) | China | Cross-sectional | 39,438 | Quartile 2 | 77–108 | 0.70 (0.55, 0.88) | Two non consecutive days of intake data were available for each participant. Dietary selenium intake from foods was calculated using the US Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies. | |

| Quartile 3 | 108–148 | 0.71 (0.53, 0.93) | ||||||

| Quartile 4 | 148–400 | 0.61 (0.43, 0.85) | ||||||

| Hu et al. (2017) (35) | Canada | Cross-sectional | Quartile 2 | 31–85 | 1.32 (0.59, 2.96) | Dietary selenium intake from country food (i.e., dietary selenium) was estimated with a food frequency questionnaire | ||

| Quartile 3 | 86–225 | 0.57 (0., 22, 1.48) | ||||||

| Quartile 4 | 226–825 | 0.18 (0.05, 0.71) | ||||||

| Chen et al. (2024) (54) | China | Cross-sectional | 26,433 | – | – | 1.016 (0.978, 1.055) | The diet-derived intake information was obtained from a detailed dietary interview component that estimated the types and amounts of foods and beverages consumed during the 24 h period prior to the interview | |

| Merrill et al. (2017) (45) | USA | Cross-sectional | 27,770 | Quartile 2 | – | 1.08 (0.87, 1.33) | Not mentioned | |

| Quartile 3 | – | 1.21 (0.98, 1.48) | ||||||

| Quartile 4 | – | 1.34 (1.10, 1.64) | ||||||

| Marniemi et al. (2005) (14) | USA | Case–control | 2,275 | – | – | 0.983 (0.55, 1.77) | Derived from dietary assessment over two non-consecutive days (using 24-h dietary recall) | |

Characteristics of studies included in this meta-analysis.

Quality assessment

Each author independently assessed the quality and risk of bias of the included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa score (NOS) (22); It is based on 3 broad perspectives: the selection process of study cohorts, the comparability among different cohorts, and the identification of either the exposure or outcome of study cohorts, disagreements were settled by discussion. Research that received scores of 0–4 and 5–9 were classified as high-quality and low-quality, respectively. A low NOS score typically implies that the study is of poor quality.

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted using STATA version 17.0 and Review Manager software version 5.3. For continuous data, mean ± standard deviation is displayed, along with the mean with standard deviation mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). If the included studies provided the data using median and quartile values, we estimated the mean and standard deviation 17 using the Wan et al. approach (23). The data heterogeneity was assessed using I-square (I2) statistics. Results for included studies where I2 > 50% were analyzed using the random-effects model. A fixed-effect model was used if not. Statistical significance was defined as p-values<0.05, and 95% confidence intervals were supplied. The random effects models were used to depict odds ratios in the forest plots. A mixed logistic regression model with random treatment effects was used to determine the overall OR. The pooled effect sizes and 95% CIs were calculated using forest plots. The odds ratio (OR) was considered equivalent to the relative risk (RR). We conducted a dose–response meta-analysis utilizing the methodology established by Greenland and Longnecker (24) and Orsini et al. (25). To assess the trend from the associated log relative risk across categories of dietary selenium use. Employing this technique, we obtained the quantity of dietary selenium consumption, distributions of cases and person-years of dietary selenium consumption, distributions of cases and person-years, relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The median or mean dietary selenium intake for each group was utilized as the matching open-ended, we considered the boundary equivalent to that of the next neighboring category. We assessed a possible correlation between dietary selenium and stroke risk utilizing limited cubic splines with three knots at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of the distribution. A p-value was determined by equating the coefficient of the second spline to zero.

A funnel plot was used to visually analyze the symmetry of the publication to determine publication bias.

Results

Literature search and study characteristics

A total of 3,048 citations were identified, encompassing only the titles and abstracts passed muster. Complete text of potentially relevant papers was read. Table 1 lists the features of the included researches, and Figure 1 displays the flow chart of the literature search. After removing the duplicates, 375 items were still present, a total of 191 publications underwent initial screening based on their titles and abstracts, 90 reviews, 36 case reports or letters, 39 non-human studies were removed. Eventually, the remaining 26 full-text papers were assessed based on the qualifying requirements (Figure 1).

Consequently, a total of 26 studies involving selenium and ischemic stroke, encompassing patients, were examined qualitatively, and then a meta-analysis was conducted (Table 1). Twenty one studies about the level circulating selenium and incidence of ischemic stroke with a total of 87,772 patients, 6 studies about dietary selenium intake and ischemic stroke, totaling 59,252 participants, were analyzed qualitatively and meta-analysed (Table 1). Six to nine was the range of quality scores. Every record that was included was thought to be of moderate to high quality.

The aggregated weighted mean difference (WMD) of the circulating selenium levels between ischemic stroke patients and controls

The aggregated WMD showed that circulating selenium levels were lower in ischemic stroke than controls (WMD = −0.13 [−0.20,−0.07]) (Figure 2A). In subgroup analysis, we observe a difference in whole blood selenium concentration between ischemic stroke patients and controls (WMD = −0.32 [−0.41, −0.22]) (Figure 2B), but no difference in serum (WMD = −0.04 [−0.19, 0.10]) (Figure 2B) and plasma Se concentration (WMD = −0.11 [−0.21, 0.03]). According to different regions and populations, the results indicated that circulating selenium levels were lower in non-Chinese (WMD = −0.16 [−0.21, −0.10]) (Figure 3), rather than Chinese (WMD = −0.08 [−0.20, −0.07]) (Figure 3). Additionally, the results from the sensitivity analysis are presented in Table 2.

Figure 2

(A) Circulating selenium levels between ischemic stroke patients and controls. (B) Subgroup analysis between Se concentration between stroke patients and controls.

Figure 3

Association between circulating selenium levels and ischemic stroke risk.

Table 2

| Outcome | Studies | WMD | 95%CI | I2 for heterogeneity | P for heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selenium biomarker | 16 | ||||

| Whole blood | 4 | −0.32 | −0.41, −0.22 | 97.9% | P = 0.000 |

| Serum | 6 | −0.04 | −0.16, 0.08 | 99.2% | P = 0.000 |

| Plasma | 6 | −0.11 | −0.22, 0.00 | 94.9% | P = 0.000 |

| Region | 16 | ||||

| Europe | 5 | −0.08 | −0.17, 0.01 | 99.6% | P = 0.007 |

| Asia | 7 | −0.05 | −0.15, 0.05 | 99.4% | P = 0.000 |

| North America | 4 | −0.34 | −0.43, −0.24 | 97.1% | P = 0.256 |

Subgroup analysis of WMD and sensitivity analysis in ischemic stroke and controls.

The multivariable-adjusted RR of stroke for the highest compared with the lowest categories of circulating selenium concentrations

In the present meta-analysis, the RR indicated that increased circulating selenium levels were inversely related to ischemic stroke incidence, with RR of (0.88 [0.83–0.92]) (Figure 4), rather than hemorrhagic stroke, with RR of 0.82 (0.69, 1.01) (Table 3).

Figure 4

(A) Circulating selenium levels and ischemic stroke incidence; (B) Subgroup analysis Circulating selenium levels and ischemic stroke incidence by study type; (C) Subgroup analysis Circulating selenium levels and ischemic stroke incidence by Se biomarker.

Table 3

| Outcome | Studies | OR/RR | 95%CI | I2 for heterogeneity | P for heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selenium biomarker | 14 | ||||

| Whole blood | 5 | 0.95 | 0.90, 1.01 | 77.9% | P = 0.001 |

| Serum/plasma | 7 | 0.71 | 0.64, 0.80 | 91.1% | P = 0.000 |

| Selenoprotein | 2 | 0.54 | 0.43, 0.68 | 34.9% | P = 0.215 |

| Study type | 14 | ||||

| Cross-sectional | 3 | 0.41 | 0.26, 0.64 | 49.2% | P = 0.140 |

| Prospective | 3 | 0.69 | 0.58, 0.82 | 69% | P = 0.04 |

| Case–control | 8 | 0.91 | 0.86, 0.95 | 92.6% | P = 0.000 |

| Sex | 6 | ||||

| Female | 6 | 0.88 | 0.81, 0.96 | 76.1% | P = 0.032 |

| Male | 6 | 0.82 | 0.74, 0.90 | 59.5% | P = 0.679 |

| BMI | 4 | ||||

| ≥24 | 4 | 0.87 | 0.81, 0.94 | 57.2% | P = 0.03 |

| <24 | 4 | 0.79 | 0.71, 0.87 | 67.2% | P = 0.027 |

| Age | 6 | ||||

| ≥60 | 6 | 0.84 | 0.77, 0.91 | 71.4% | P = 0.004 |

| <60 | 6 | 0.83 | 0.75, 0.92 | 44.3% | P = 0.110 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 4 | 0.84 | 0.69, 1.01 | 41.3% | P = 0.164 |

| Region | 14 | ||||

| Europe | 3 | 0.63 | 0.51, 0.78 | 79.6% | P = 0.007 |

| Asia | 7 | 0.9 | 0.86, 0.95 | 93.4% | P = 0.000 |

| North America | 4 | 0.42 | 0.27, 0.65 | 26% | P = 0.256 |

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis of the selenium circulating level and stroke risk.

Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis for circulating selenium levels and ischemic stroke incidence

Significant heterogeneity was observed across studies (I2 = 89.6%, p < 0.001), consequently, we conducted subgroup analysis. There was an inverse relationship between increased circulating selenium levels and stroke incidence. The conclusion was supported by selenoprotein P (0.54 [0.43, 0.68]) (Figure 4C), plasma/serum (0.71 [0.64, 0.80]) (Figure 4C), BMI ≥ 24 (0.87 [0.81, 0.94]) (Table 3) and age≥60 years old (0.84 [0.77, 0.91]) (Table 3), case–control studies (0.91 [0.86, 0.95]) (Figure 4B), prospective studies (0.69 [0.58, 0.82]) (Figure 4B) rather than whole blood (0.95 [0.90, 1.01]) (Figure 4C) and cross-sectional studies (0.41 [0.26, 0.64]) (Figure 4B). Additionally, the results from the sensitivity analysis are presented in Table 3.

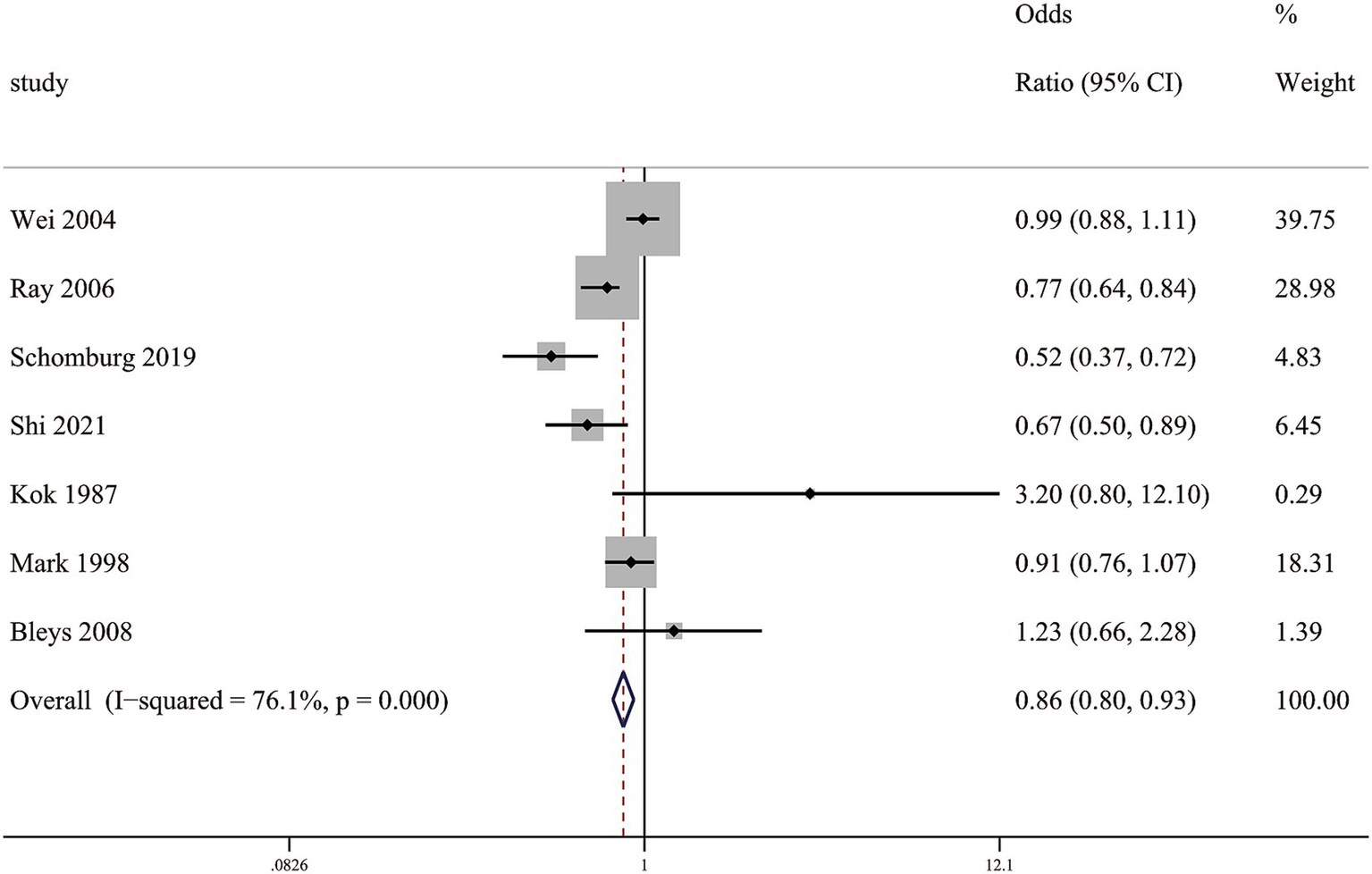

Circulating selenium levels and stroke mortality

In our meta-analysis, a multivariable-adjusted RR demonstrated that elevated circulating selenium concentrations showed a significant inverse correlation with stroke mortality, with RR of (0.86 [0.80–0.93]) (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Association between circulating selenium levels and stroke mortality.

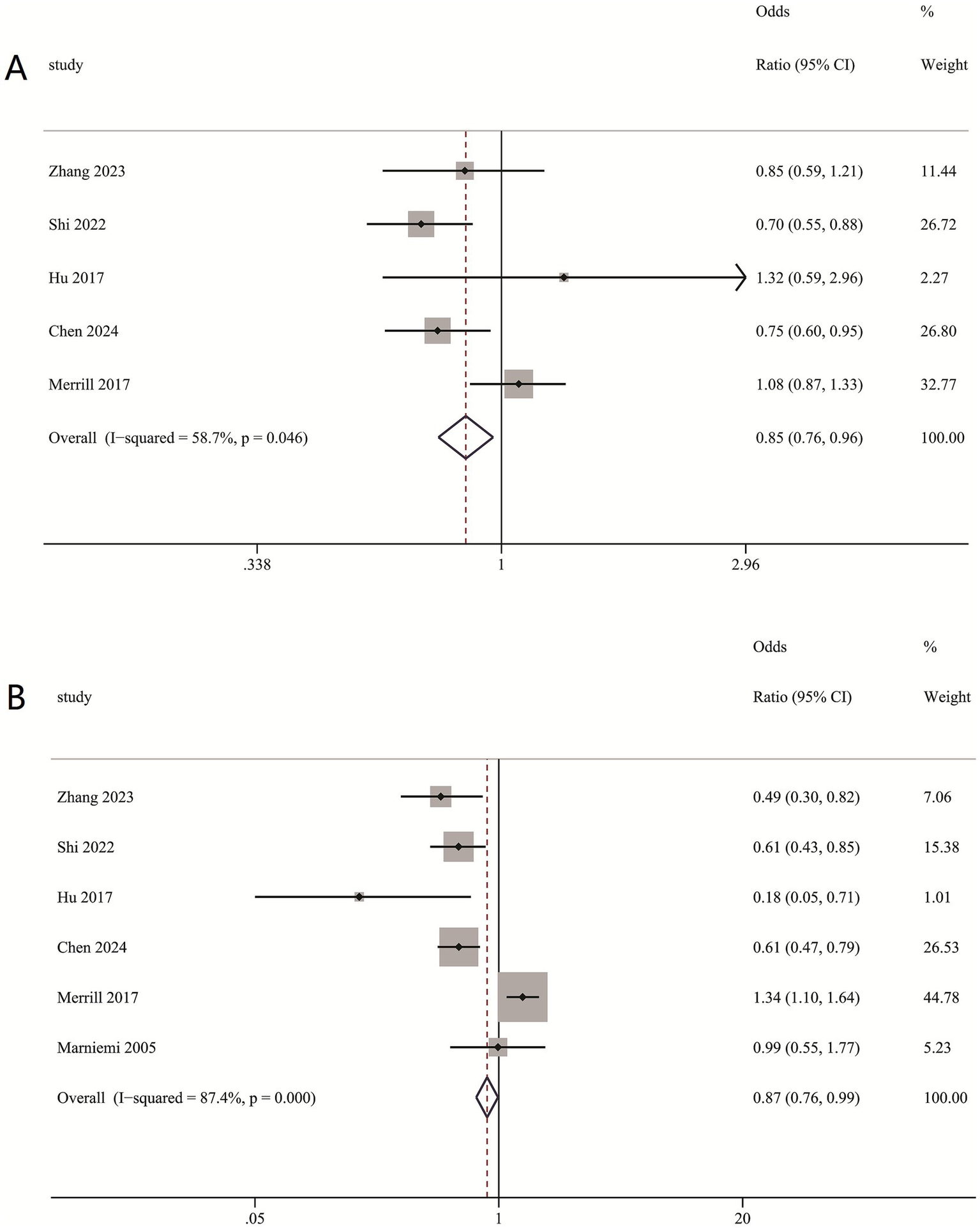

The connection between the incidence of stroke and dietary selenium intake

Our meta-analysis disclosed that higher dietary selenium intake was inversely associated with ischemic stroke risk. Compared to the lowest quartile, the second-highest quartile of dietary selenium intake showed RR of 0.85 (0.76, 0.96) (Figure 6A), while the highest quartile with RR of 0.87 (0.76, 0.99) (Figure 6B).

Figure 6

(A) Association between second-highest quartile dietary intake and ischemic stroke risk; (B) Association between highest quartile dietary intake and ischemic stroke risk.

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis of dietary selenium intake

Subgroup analysis indicated that lower dietary selenium consumption was linked to a decreased stroke risk in females (RR = 0.91 [0.88, 0.95]), males (RR = 0.92 [0.87, 0.97]), age ≥ 60 (RR = 0.93 [0.89, 0.98]), age < 60 (RR = 0.9 [0.87, 0.99]) (Table 4). Furthermore, dietary selenium intake was substantially linked with the prevalence of ischemic stroke in hypertensive individuals (OR = 0.89 [0.85, 0.94]) (Table 4).

Table 4

| Outcome | Studies | RR/OR | 95%CI | I2 for heterogeneity | P for heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 4 | 0.91 | 0.88, 0.95 | 77.9% | P = 0.004 |

| Male | 4 | 0.92 | 0.87, 0.97 | 68.1% | P = 0.024 |

| Age | |||||

| ≥60 | 4 | 0.93 | 0.89, 0.98 | 77.9% | P = 0.004 |

| <60 | 4 | 0.90 | 0.87, 0.99 | 71.4% | P = 0.015 |

| Dietary intake level | |||||

| 2 quartile | 5 | 0.85 | 0.76, 0.96 | 58.7% | P = 0.046 |

| 4 quartile | 5 | 0.87 | 0.73, 0.99 | 87.4% | P = 0.000 |

| Hypertension | 3 | 0.89 | 0.85, 0.94 | 87.1% | P = 0.000 |

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis of the dietary selenium intake and stroke risk.

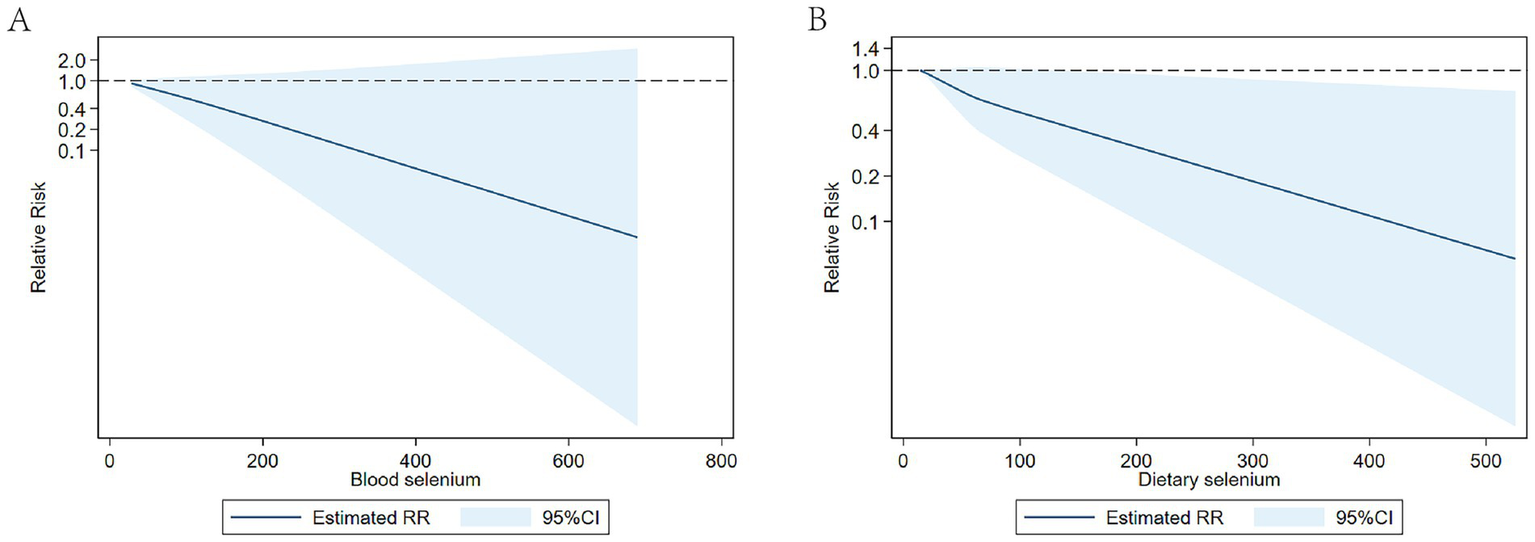

Dose–response meta-analysis

Our analysis revealed an inverse linear relationship between circulating selenium levels and stroke risk, while no such association was observed in dietary selenium intake (Figure 7).

Figure 7

(A) Dose-response of circulating selenium levels and stroke risk; (B) Dose-response of dietary selenium intake and stroke risk.

Publication bias

Visual inspection of the funnel plot revealed symmetry, indicating minimal publication bias (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Funnel plot.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis revealed that circulating selenium levels were lower in ischemic stroke than controls. Meanwhile, we found significant inverse association between circulating selenium concentrations and stroke incidence as well as stroke mortality, indicating that the level of circulating selenium may play a role in the development of ischemic stroke. Participants with higher dietary selenium intake had a lower prevalence of stroke compared to the lower ones. Our dose–response meta-analysis revealed a significant inverse linear relationship between circulating selenium levels and ischemic stroke.

Selenium is an essential trace element that acts as a co-factor in various enzymes involved in key biological processes, including enzymatic antioxidant defense and immune system regulation. Some studies suggest that selenium deficiency may be associated with an increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (26) and atrial fibrillation (27). However, findings regarding the relationship between selenium and cerebrovascular disease remain inconsistent. Previous investigations (28–33) have extensively examined the association between circulating selenium concentrations and ischemic stroke. Mirończuk et al. (28) revealed that the serum selenium concentrations were significantly decreased in patients with ischemic stroke compared with healthy controls. Lower serum selenium levels were observed among acute ischemic stroke patients in Angelova et al. (29) study. The study by Nahan et al. (30) demonstrated that patients with acute ischemic stroke had markedly reduced circulating selenium concentrations versus controls. A similar finding was reported in Wang et al.’s study (31). The study by Kayama and colleagues (32) demonstrated that whole blood selenium concentrations were markedly reduced in patients with acute ischemic stroke patients relative to healthy controls. In contrast, study conducted by Skalny et al. (33) reported elevated circulating selenium levels in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Our present meta-analysis showed that circulating selenium levels were lower in ischemic stroke than controls, which was consistent with Ding and Zhang (20) study. Our meta-analysis demonstrated high heterogeneity, prompting subgroup analysis by study population. These analyses demonstrated significantly lower circulating selenium levels in ischemic stroke patients versus controls in non-Chinese populations, whereas no significant difference was observed in Chinese cohorts. These findings suggest that population-specific and regional factors may account for the substantial heterogeneity. The observed phenomenon may be attributed to both regional variations in selenium intake and differences in selenium metabolism.

Meanwhile, several studies have investigated the association between circulating selenium levels and stroke risk, but yielded inconsistent conclusions. Kok et al. (34) and Hu et al. (35) studies have suggested a negative connection between circulating selenium concentrations and ischemic stroke. A nested case–control research conducted by Xiao et al. (36) discovered that elevated circulating selenium levels were substantially correlated with a decreased risk of hemorrhagic stroke, but not with ischemic stroke. Our team conducted subgroup analyses showed an inverse correlation between circulating selenium levels and the risk of ischemic stroke, but not with hemorrhagic stroke, which is consistent with Hu’s finding (35). Notably, given the substantial heterogeneity observed, we conducted subgroup analyses by study type. There was an inverse association between circulating selenium levels and stroke risk in prospective and case–control studies rather than cross-sectional studies. It is worth noting that the inverse association between circulating selenium levels and stroke risk, as reported in the systematic review by Ding and Zhang (20), was specifically observed in cross-sectional/case–control studies, as opposed to prospective cohort designs. This discrepancy likely occurs because cross-sectional studies measure selenium levels at an undetermined time relative to stroke onset. When selenium is measured after stroke occurrence, it may reflect post-stroke metabolic changes rather than serving as causative risk factor. In light of this evidence, the high degree of heterogeneity may be attributable to critical variations in study design.

Notably, the inverse association between selenium levels and stroke has been predominantly observed in populations with generally low selenium exposure (e.g., China and Canada), while this protective relationship is less evident in regions with inherently high selenium status, such as the United States. Future research should focus on investigating the association between varying levels of selenium exposure and stroke risk.

The relationship between selenium concentrations and stroke risk is complex. Potential underlying mechanisms may include: First, Selenium exhibits potent antioxidant activity by up regulating selenoproteins such as glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and thioredoxin reductase (TrxR), thereby attenuating oxidative stress and potentially reducing cerebral infarction risk (37, 38). Second, selenium can improve atherosclerotic plaque stability and vasomotor function while inhibiting platelet aggregation and thrombus development (39). Third, Se-induced mitochondrial dysfunction prevention may considerably contribute to reducing lipid peroxidation and restoring ATP(Adenosine Triphosphate) concentrations, hence reducing infarct volume following localized cerebral ischemia (40). Fourth, selenium inhibits activation of the NF-κB inflammatory signaling pathway, resulting in down regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and consequent reduction in both the incidence and progression of cerebral infarction (41). Collectively, the available evidence suggests that selenium could confer dual neuroprotective benefits through both direct antioxidant mechanisms and indirect anti-inflammatory pathways in stroke prevention.

It is noteworthy that variations in selenium biomarkers (e.g., plasma, whole blood, serum, and selenoprotein) used across studies to assess the selenium-stroke association, which may contribute to the inconsistent findings observed in the literature (42). Whole blood analysis served as the primary method for determining selenium status in the earlier selenium research, the prolonged half-life of whole blood selenium establish its utility as a reliable indicator of chronic selenium exposure status (42). The most clinically useful biomarkers for assessing selenium status are serum and plasma, while plasma selenium has a short half-life and is more sensitive to short-term variations, mainly indicating current exposure status, which differ fundamentally from whole blood selenium. Impaired selenoprotein P function adversely affects selenium homeostasis, attenuating its cytoprotective effects and consequently increasing susceptibility to stroke (42). Therefore, measurement of selenoprotein P is necessary. Inconsideration of the selenium biomarkers and substantial heterogeneity, we conducted subgroup analysis, which examined the correlation between different selenium biomarkers (plasma, whole blood, serum, and selenoprotein) and the occurrence of stroke (43–46). Our present meta-analysis revealed that increased selenoprotein P and plasma/serum levels were linked to a decreased risk of ischemic stroke rather than whole blood. In contrast, the study by Ding and Zhang (20) reported an inverse association between whole blood selenium and stroke, while no significant association was observed for serum/plasma selenium. Thus, the employment of inconsistent biomarkers across included studies contributed substantially to the observed methodological heterogeneity.

The current study also identified a substantial link between circulating Se levels and stroke mortality. A cohort study (47) discovered that reduced circulating selenium concentrations were linked to a higher risk of stroke related mortality, which was in agreement with our findings. In contrast, no association was observed between stroke mortality and serum selenium in Wei et al.’s study (48). While some studies suggest a U-shaped relationship between selenium levels and the risk of cardiovascular disease as well as other health outcomes (49), no toxic effects were observed in the study. However, elevated selenium intake has been linked to potential toxicity in other reports (13). Recommended daily intake of selenium varies across regions. In the United States, the Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) suggests an Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) of 45 g/day, a Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of 55 μg/day, and a Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) of 400 μg/day for adults aged 19–50 (50). In the United Kingdom, the Reference Nutrient Intake (RNI) is set at 60 μg/day for adult women and 75 μg/day for lactating women and adult men (51). For Chinese adults, the corresponding EAR, RNI, and UL values are 50, 60, and 400 μg/day, respectively (52). Significant geographical differences exist in baseline selenium levels, with some populations exhibiting notably higher concentrations than others. For Americans with adequate selenium intake, supplementation may lead to toxic effects, whereas selenium-deficient populations in China are more likely to benefit from it. Thus, regional selenium status should be considered when evaluating its association with stroke (16). The precise mechanism behind the negative correlation between selenium and stroke mortality remains uncertain. However, research (41) has indicated that selenium may provide benefits to stroke patients by decreasing the size of infarcts, enhancing prognosis, and reducing mortality rates.

Previous research have yielded conflicting findings on the significance of dietary selenium consumption in ischemic stroke (35, 44, 53, 54). A study (53) among Inuit in China revealed no link relationship between selenium consumption in the diet and the likelihood of having a stroke in persons with anemia. Conversely, a Canadian study (35) observed a reverse association between dietary selenium intake and prevalence of stroke in Inuit who exposed to high selenium levels through their traditional diet, consistent findings were reported in Chen et al.’s (54) study. Our study revealed an inverse connection between dietary selenium intake and stroke risk, indicating that elevated dietary selenium intake was associated with a decreased risk of stroke, which was consistent with Canadian’s study. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review specifically investigating the relationship between dietary selenium intake and stroke incidence. As an essential trace element in antioxidant systems, selenium demonstrates significant cerebrovascular benefits, showing both prophylactic effects against stroke incidence and therapeutic potential for post-stroke recovery.

In our dose–response meta-analysis, a negative linear correlation was observed between dietary selenium intake and stroke risk. However, no definitive intake threshold was established for optimal protective benefit against stroke. These findings are partially inconsistent with extensive observational studies that suggest a potential L-shaped or non-linear relationship between selenium intake and ischemic stroke outcomes (55). Hu et al. (35) found that dietary selenium are reversely associated with the prevalence of stroke in Inuit, which follows an L-shaped relationship, and the estimated turning points of the L-shaped curve for dietary selenium was 350 μg/day. Meanwhile, nonlinear L-shaped this relationship was observed in the study by Zhang et al. (56) in Chinese, the cut-off point for selenium was 60 μg/day. In the study conducted by Shi et al. (53), dietary selenium intake had a negative and non-linear correlation with the risk of stroke in U.S. adults, with a nodal point observed at 105 μg/day beyond which no additional benefit was detected. Potential explanations for the observed discrepancies in findings may include: (1) Substantial geographic variations in dietary selenium intake: Regions like Venezuela, Canada, the USA, and Japan typically demonstrate high selenium intake, while European countries show significantly lower levels. Chinese populations exhibit even lower selenium intake, with most areas being selenium-deficient. Current evidence (54) generally supports a U-shaped relationship between selenium and health outcomes, mostly derived from all-cause mortality, with recognized toxicity at high exposure levels. The relationship between selenium and stroke may differ. We hypothesize that populations chronically exposed to high selenium levels may develop adaptive mechanisms, requiring greater selenium intake to maintain optimal selenoprotein activity, thereby exhibiting different dose–response patterns. (2) Population-specific characteristics in our analysis: Our systematic review primarily incorporated dose–response studies conducted in China—a typically low-selenium region where exposure levels rarely reach the toxic threshold (57). This may explain the observed linear inverse association in our analysis, contrasting with the U-shaped relationships reported in high-selenium populations.

The strengths of this meta-analysis are threefold. First, it represents the first comprehensive synthesis of evidence regarding the association between circulating selenium levels, dietary selenium intake, and stroke risk, supported by an extensive and systematic literature search. Second, the analysis relied on adjusted effect estimates from large-sample studies, enhancing the reliability of the findings. Third, potential heterogeneity was rigorously evaluated using established statistical methods, and where significant heterogeneity was identified, subgroup analyses and meta-regression were conducted to investigate underlying sources. The limitations of the current investigation should also be recognized. First, dietary selenium intake was self-reported in most studies, which may be influenced by recall bias, misclassification, as well as possible sources of confounding such as lifestyle variables, meanwhile, few studies adjusted for confounding dietary factors. Second, heterogeneous exposure categorization methods between studies likely contributed to measurement variability. Third, the lack of stroke subtype stratification precludes mechanistic insights into selenium’s potential differential effects. Fourth, the bio availability of selenium varies substantially across food sources, yet no studies examined source-specific effects on stroke risk—a critical gap for future research. Finally, most of the studies were from China, Canada and America, which may have limited applicability to populations with varying baseline selenium status, which highlight the need for multinational studies to validate these associations across populations with differing selenium statuses.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis discovered that circulating selenium concentrations are inversely associated with stroke risk and mortality, which suggesting its potential role as modifiable stroke risk factor. Meanwhile, higher dietary selenium intake shows an inverse correlation with ischemic stroke risk. Additional well-structured prospective cohort studies with precise selenium biomarker specifications and suitable selenium intake dosages are necessary to further elucidate these associations.

Statements

Author contributions

YL: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. XP: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. PG: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZL: Writing – review & editing. LP: Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Zhou M Wang H Zeng X Yin P Zhu J Chen W et al . Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. (2019) 394:1145–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30427-1

2.

Wang W Jiang B Sun H Ru X Sun D Wang L et al . Prevalence, incidence, and mortality of stroke in China: results from a nationwide population based survey of 480687 adults. Circulation. (2017) 135:759–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025250

3.

Wu S Wu B Liu M Chen Z Wang W Anderson CS et al . Stroke in China: advances and challenges in epidemiology, prevention, and management. Lancet Neurol. (2019) 18:394–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30500-3

4.

Roth GA Johnson C Abajob ir A Abd-Allah F Abera SF Abyu G et al . Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 70:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052

5.

Lackland DT Roccella EJ Deutsch AF Fornage M George MG Howard G et al . Factors influencing the decline in stroke mortality: a statement from the American Heart Association/ American Stroke Association. Stroke. (2014) 45:315–53. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000437068.30550.cf

6.

Feigin VL Roth GA Naghavi M Parmar P Krishnamurthi R Chugh S et al . Global burden of stroke and risk factors in 188 countries, during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Neuro. (2016) 15:913–24. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30073-4

7.

World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations . Chapter 15,Selenium In: World Health Organization Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Human Vitamin and Mineral Requirements—Report of a joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation. World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2002). 235–56.

8.

Rayman MP . The importance of selenium to human health. Lancet. (2000) 356:233–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02490-9

9.

Hurst R Armah CN Dainty JR Hart DJ Teucher B Goldson AJ et al . Establishing optimal selenium status: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. (2010) 91:923–31. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28169

10.

Roman M Jitaru P Barbante C . Selenium biochemistry and its role for human health. Metallomics. (2014) 6:25–54. doi: 10.1039/C3MT00185G

11.

Zoid is E Seremelis I Kontopoulos N Danezis GP . Selenium-dependent antioxidant enzymes: actions and properties of selenoproteins. Antioxidants (Basel). (2018) 7:66. doi: 10.3390/antiox7050066

12.

Ahmad A Khan MM Ishrat T Khan MB Khuwaja G Raza G et al . Synergistic effect of selenium and melatonin on neuroprotection in cerebral ischemia in rats. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2011) 139:81–96. doi: 10.1007/s12011-010-8643-z

13.

Chawla R Filippini T Loomba R Cilloni S Dhillon KS Vinceti M et al . Exposure to a high selenium environment in Punjab, India: biomarkers and health conditions. Sci Total Environ. (2020) 719:134–541. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134541

14.

Marniemi J Alanen E Impivaara O Seppänen R Hakala P Rajala T et al . Dietary and serum vitamins and minerals as predictors of myocardial infarction and stroke in elderly subjects. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2005) 15:188–97. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2005.01.001

15.

Wang Z Ma H Song Y Lin T Liu L Zhou Z et al . Plasma selenium and the risk of first stroke in adults with hypertension: a secondary analysis of the China stroke primary prevention Trial. Am J Clin Nutr. (2022) 115:222–31. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqab320

16.

Hu H Bi C Lin T Liu L Song Y Wang B et al . Sex difference in the association between plasma selenium and first stroke: a community-based nested case-control study. Biol Sex Differ. (2021) 12:39. doi: 10.1186/s13293-021-00383-2

17.

Chang CY Lai YC Cheng TJ Lau MT Hu ML . Plasma levels of antioxidant vitamins, selenium, total sulfhydryl groups and oxidative products in ischemic-stroke patients as compared to matched controls in Taiwan. Free Radic Res. (1998) 28:15–24. doi: 10.3109/10715769809097872

18.

Hui F Weishi L Luyang Z Lulu P Yuan G Lu Z et al . A bidirectional mendelian randomization study of selenium levels and ischemic stroke. Front Genet. (2022) 13:782691. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.782691

19.

Kuria A Tian HD Li M Wang YH Aasethe JO Zang JJ . Selenium status in the body and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. (2021) 61:3616–25. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1803200

20.

Ding J Zhang Y . Relationship between the circulating selenium level and stroke: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Am Coll Nutr. (2022) 41:444–52. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2021.1902880

21.

Liberati A Altman DG Tetzlaff J Mulrow C Gotzsche PC Ioannidis JPA et al . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. (2009) 339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700

22.

Margulis V Pladevall M Riera-Guardia N Varas-Lorenzo C Hazell L Berkman ND et al . Quality assessment of observational studies in a rug-safety systematic review,comparison of two tools: the Newcastle-Ottawa scale and the RTI item bank. Clin Epidemiol. (2014) 6:359–68. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S66677

23.

Wan X Wang W Liu J Tong T . Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2014) 14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135

24.

Greenland S Longnecker MP . Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose– response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. (1992) 135:1301–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116237

25.

Orsini N Bellocco R Greenland S . Generalized least squares for trend estimation of summarized dose– response data. Stat J. (2006) 6:40–57.

26.

Xiao J Li N Xiao S Wu Y Liu H . Comparison of selenium nanoparticles and sodium selenite on the alleviation of early ather osclerosis by inhibiting endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:11612. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111612

27.

Ardahanli I Ozkan HI . Comparison of serum selenium levels between patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation and Normal controls. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2022) 200:3925–31. doi: 10.1007/s12011-022-03281-9

28.

Mirończuk A Kapica-Topczewska K Socha K Soroczyńska J Jamiołkowski J Kułakowska A et al . Selenium, copper, zinc concentrations and Cu/Zn, Cu/Se molar ratios in the serum of patients with acute ischemic stroke in northeastern Poland-a new insight into stroke pathophysiology. Nutrients. (2021) 13:2139. doi: 10.3390/nu13072139

29.

Angelova E Atanassova P Chalakova N Dimitrov B . Associations between serum selenium and total plasma homocysteine during the acute phase of ischaemic stroke. Eur Neurol. (2008) 60:298–303. doi: 10.1159/000157884

30.

Nahan KS Walsh KB Adeoye O Landero-Figueroa JA . The metal and metalloprotein profile of human plasma as biomarkers for stroke diagnosis. J Trace Elem Med Biol. (2017) 42:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2017.04.004

31.

Wang Z Hu S Song Y Liu L Huang Z Zhou Z et al . Association between plasma selenium and risk of ischemic stroke: a community-based, nested, and case-control study. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:1001922. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1001922

32.

Koyama H Abdulah R Ohkubo T Imai Y Satoh H Nagai K . Depressed serum selenoprotein P: possible new predicator of increased risk for cerebrovascular events. Nutr Res. (2009) 29:94–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2009.01.002

33.

Skalny AV Klimenko LL Turna AA Budanova MN Baskakov IS Savostina MS et al . Serum trace elements are associated with hemostasis, lipid spectrum and inflammatory markers in men suffering from acute ischemic stroke. Metab Brain Dis. (2017) 32:779–88. doi: 10.1007/s11011-017-9967-6

34.

Kok FJ de Bruij n AM Vermeeren R Hofman A van Laar A de Bruin M et al . Serum selenium, vitamin antioxidants, and cardiovascular mortality: a 9-year follow-up study in the Netherlands. Am J Clin Nutr. (1987) 45:462–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.2.462

35.

Hu X Sharin T Chan H . Dietary and blood selenium are inversely associated with the prevalence of stroke among Inuit in Canada. J Trace Elem Med Biol. (2017) 44:322–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2017.09.007

36.

Xiao Y Yuan Y Liu Y Yu Y Jia N Zhou L et al . Circulating multiple metals and incident stroke in Chinese adults. Stroke. (2019) 50:1661–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025060

37.

Shi Y Han L Zhang X Xie L Pan P Chen F et al . Selenium alleviates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating oxidative stress, mitochondrial fusion and ferroptosis. Neurochem Res. (2022) 47:2992–3002. doi: 10.1007/s11064-022-03643-8

38.

Chomchan R Puttarak P Brantner A Siripongvutikorn S . Selenium rich rice grass juice improves antioxidant properties and nitric oxide inhibition in macrophage cells. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland). (2018) 7:57. doi: 10.3390/antiox7040057

39.

Rayman M . Selenium and human health. Lancet. (2012) 379:1256–68. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61452-9

40.

Mehta S Kumari S Mendelev N Li P . Selenium preserves mitochondrial function, stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis, and reduces infarct volume after focal cerebral ischemia. BMC Neurosci. (2012) 13:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-13-79

41.

Schweizer U Br€auer A K€ohrle J Nitsch R Savaskan N . Selenium and brain function: a poorly recognized liaison. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. (2004) 45:164–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.03.004

42.

Combs G . Biomarkers of selenium status. Nutrients. (2015) 7:2209–36. doi: 10.3390/nu7042209

43.

Schomburg L Orho-Melander M Struck J Bergmann A Melander O . Selenoprotein-P deficiency predicts cardiovascular disease and death. Nutrients. (2019) 11:1852. doi: 10.3390/nu11081852

44.

Hu XF Stranges S Chan LHM . Circulating selenium concentration is inversely associated with the prevalence of stroke: results from the Canadian health measures survey and the National Health and nutrition examination survey. JAm Heart Assoc. (2019) 8:e012290. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012290

45.

Merrill PD Ampah SB He K Rembert NJ Brockman J Kleindorfer D et al . Association between trace elements in the Environment and stroke risk: the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study. J Trace Elem Med Biol. (2017) 42:45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2017.04.003

46.

Wen Y Huang S Zhang Y Zhang H Zhou L Li D et al . Associations of multiple plasma metals with the risk of ischemic stroke: a case-control study. Environ Int. (2019) 125:125–34. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.12.037

47.

Ray AL Semba RD Walston J Ferrucci L Cappola AR Ricks MO et al . Low serum selenium and total carotenoids predict mortality among older women living in the community: the women's health and aging studies. J Nutr. (2006) 136:172–6. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.172

48.

Wei WQ Abnet CC Qiao YL Dawsey SM Dong ZW Sun XD et al . Prospective study of serum selenium concentrations and esophageal and gastric cardia cancer, heart disease, stroke, and total death. Am J Clin Nutr. (2004) 79:80–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.1.80

49.

Cardoso BR Lago L Dordevic AL Kapp EA Raines AM Sunde RA et al . Differential protein expression due to Se deficiency and Se toxicity in rat liver. J Nutr Biochem. (2021) 98:108831. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2021.108831

50.

Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board . Dietary reference intakes: Vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids. Washington, DC: National Academy Press (2000).

51.

Stoffaneller R Morse NL . A review of dietary selenium intake and selenium status in Europe and the Middle East. Nutrients. (2015) 7:1494–537. doi: 10.3390/nu7031494

52.

Chinese Nutrition Society . Chinese DRIs handbook (version of 2013). Beijing: Standards Press of China (2014).

53.

Shi W Su L Wang J Wang F Liu X Dou J et al . Correlation between dietary selenium intake and stroke in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2018. Ann Med. (2022) 54:1395–402. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2058079

54.

Chen R Liu H Zhang G Zhang Q Hua W Zhang L et al . Antioxidants and the risk of stroke: results from NHANES and two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Eur J Med Res. (2024) 29:50. doi: 10.1186/s40001-024-01646-5

55.

Bleys J Navas-Acien A Guallar E . Serum selenium levels and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality among US adults. Arch Intern Med. (2008) 168:404–10. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.74

56.

Zhang H Qiu H Wang S Zhang Y . Association of habitually low intake of dietary selenium with new-onset stroke: a retrospective cohort study (China Health and Nutrition Survey). FrontPublic Health. (2023) 10:1115908. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1115908

57.

Huang Z Rose AH Hoffmann PR . The role of selenium in inflammation and immunity: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2012) 16:705–43. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4145

Summary

Keywords

nutrition, stroke, selenium, microelements, antioxidants

Citation

Li Y, Ding R, Pei X, Gao P, Liu Z and Piao L (2025) Relationship between selenium intake, circulating selenium levels, and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 16:1578103. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1578103

Received

08 April 2025

Revised

04 November 2025

Accepted

10 November 2025

Published

04 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Lutz Schomburg, Charité University Medicine Berlin, Germany

Reviewed by

Joanna Rog, John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Poland

İsa Ardahanlı, Bilecik Şeyh Edebali University, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Li, Ding, Pei, Gao, Liu and Piao.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lifeng Piao, piaolifeng2024@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.