Abstract

Objective:

To explore the influencing factors of postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing hip replacement (HR) under general anesthesia, and to construct and validate a nomogram prediction model.

Methods:

A total of 329 patients who underwent general anesthesia HR surgery in our hospital from December 2021 to December 2023 were retrospectively gathered and grouped into a modeling group (230 cases) and a validation group (99 cases). The modeling group was separated into a sleep disorder group and a no sleep disorder group based on postoperative sleep disorders.

Results:

Out of 230 patients, 69 experienced sleep disorders, with an incidence rate of 30.00%. Multivariate logistic regression found that age, anesthesia time, surgery time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative hypoxemia, postoperative VAS score, and postoperative CRP level were risk factors for postoperative sleep disorders in elderly HR patients undergoing general anesthesia (p < 0.05). The AUC of the modeling group and validation group was 0.978 and 0.972, and the H-L test showed χ2 = 7.410 and 7.342, respectively, p = 0.762 and 0.752, indicating good consistency. DCA curve showed that when the high-risk threshold probability was between 0.08 and 0.88, the nomogram model had high clinical value.

Conclusion:

Age, anesthesia time, surgery time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative hypoxemia, postoperative VAS score, and postoperative CRP level are the influencing factors of postoperative sleep disorders in elderly HR patients undergoing general anesthesia. The nomogram model constructed based on this has good discrimination and consistency, and can predict the postoperative sleep disorders of patients.

1 Introduction

Accompanying the trend of population aging, elderly hip joint diseases have become a clinical concern, with an evident increase in the risk of hip fractures, osteoarthritis, and other hip joint diseases among the elderly population (1). Hip replacement (HR) surgery is a primary clinical treatment method for hip joint diseases, which can reconstruct the patient’s hip joint function, control the progression of the disease, and improve the patient’s quality of life (2). However, the elderly patients’ various physiological functions are relatively low, leading to poor tolerance to surgery and anesthesia, increasing the likelihood of complications. Postoperative sleep disorders are one such complication, mainly referring to a decline in sleep quality and alteration in sleep structure after surgery. Patients may experience sleep disorders due to environmental factors, pain, stress, and other factors during surgery, and postoperative sleep disorders are related to surgical delirium, sympathetic nervous excitement, etc., affecting the patient’s postoperative recovery and surgical efficacy (3, 4). Therefore, it is particularly important in clinical practice to identify the factors influencing postoperative sleep disorders in HR surgery patients to improve their quality of life. Nomograms are simple to operate and highly readable, integrating risk factors screened from regression analysis to accurately predict the risk at a specific time on an individual basis (5, 6). Based on this, there are few reports on the study of postoperative sleep disorders in HR surgery patients using nomograms (7). Therefore, this study aims to explore the influencing factors of postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery and the construction and validation of a nomogram prediction model.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 General data

A retrospective selection of 329 patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery in our hospital from December 2021 to December 2023 was made. Patients were randomly divided into modeling group (230 cases) and validation group (99 cases) in a 7:3 ratio (The random number table method was used, with a random number sequence generated by SPSS software to ensure that the sequence was pattern-free and conformed to the characteristics of a random distribution. The numbers in the random number table were coded from 0 to 9, with 0–6 assigned to the modeling group and 7–9 assigned to the validation group, ensuring a 7:3 allocation ratio). Patients in the modeling group were further divided into sleep disorder group and non-sleep disorder group based on postoperative sleep disorder conditions. The case collection flow chart is shown in Figure 1 (Clinical data of the patients were collected, and the patients were divided into a modeling group and a validation group. The patients in the modeling group were further divided into those with and without sleep disorders to analyze the factors influencing sleep disturbances). Inclusion criteria: (1) meeting the HR treatment indications (8); (2) undergoing general anesthesia; (3) age >60 years; (4) complete data. Exclusion criteria: (1) liver and kidney dysfunction; (2) systemic infectious diseases; (3) autoimmune diseases; (4) malignant tumors; (5) hematological diseases; (6) mental disorders. This study was approved by the hospital ethics committee.

Figure 1

Flow chart of case collection.

2.2 Postoperative sleep disorder assessment

Postoperative sleep disorders were assessed using the Self-Rating Sleep Scale (SRSS) (9), which evaluates whether patients have sleep disorders. It includes 10 items, each scored from 1 to 5, with a total score of 50. A score of <10 indicates no significant sleep disorder, while ≥10 indicates the presence of a sleep disorder.

2.3 Clinical data

Clinical data were collected from routine examinations and electronic medical record queries, including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, cerebral infarction, smoking history, alcohol history, disease type, cognitive impairment, depression, nutritional disorder, anxiety, anesthesia time, surgery time, preoperative bleeding volume, surgical method, postoperative hypoxemia, postoperative pain Visual Analog Scale (VAS)(assessed at 24 h after surgery), and postoperative C-reactive protein (CRP) levels(measured at 24 h after surgery).

2.4 Statistical processing

Data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0. Categorical data were tested using the χ2 test, expressed as cases (%). Continuous data were tested using the t-test, expressed as . Influencing factors of postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery were analyzed using multivariate logistic regression. The nomogram model for postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery was constructed using R software. The ROC curve was drawn to evaluate the discrimination of the nomogram model for postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery; the calibration curve was drawn to evaluate the model consistency; the clinical decision curve (DCA) was used to evaluate the clinical application value of the model. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3 Results

3.1 Comparison of clinical data between modeling group and validation group

There were no significant differences in clinical data between the modeling group and the validation group (p > 0.05). See Table 1.

Table 1

| Considerations | Modeling group (n = 230) | Validation group (n = 99) | t/χ 2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.176 | 0.675 | ||

| ≥70 | 101(43.91) | 41(41.41) | ||

| <70 | 129(56.09) | 58(58.59) | ||

| Genders | 0.129 | 0.720 | ||

| Man | 135(58.70) | 56(56.57) | ||

| Woman | 95(41.30) | 43(43.43) | ||

| BMI(kg/m2) | 0.168 | 0.681 | ||

| <23 | 138(60.00) | 57(57.58) | ||

| ≥23 | 92(40.00) | 42(42.42) | ||

| ASA classification | 0.554 | 0.457 | ||

| Level II | 49(21.30) | 24(24.24) | ||

| Level III | 177(76.96) | 72(72.73) | ||

| Level IV | 4(1.74) | 3(3.03) | ||

| Hypertensive | 0.169 | 0.681 | ||

| Yes | 75(32.61) | 30(30.30) | ||

| No | 155(67.39) | 69(69.70) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.177 | 0.674 | ||

| Yes | 68(29.57) | 27(27.27) | ||

| No | 162(70.43) | 72(72.73) | ||

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 0.035 | 0.851 | ||

| Yes | 58(25.22) | 24(24.24) | ||

| No | 172(74.78) | 75(75.76) | ||

| Coronary heart disease | 0.351 | 0.554 | ||

| Yes | 41(17.83) | 15(15.15) | ||

| No | 189(82.17) | 84(84.85) | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.011 | 0.918 | ||

| Yes | 17(7.39) | 7(7.07) | ||

| No | 213(92.61) | 92(92.93) | ||

| Cerebral infarction | 0.089 | 0.765 | ||

| Yes | 16(6.96) | 6(6.06) | ||

| No | 214(93.04) | 93(93.94) | ||

| Smoking history | 0.036 | 0.851 | ||

| Yes | 58(25.22) | 24(24.24) | ||

| No | 172(74.78) | 75(75.76) | ||

| Drinking history | 0.110 | 0.740 | ||

| Yes | 55(23.91) | 22(22.22) | ||

| No | 175(76.09) | 77(77.78) | ||

| Type of disease | 2.091 | 0.148 | ||

| Aseptic necrosis of the femoral head | 30(13.04) | 20(20.20) | ||

| Intertrochanteric fracture of the femur | 55(23.91) | 25(25.25) | ||

| Femoral neck fracture | 145(63.04) | 54(54.55) | ||

| With cognitive impairment | 0.138 | 0.711 | ||

| Yes | 105(45.65) | 43(43.43) | ||

| No | 125(54.35) | 56(56.57) | ||

| With depression | 0.073 | 0.787 | ||

| Yes | 59(26.65) | 24(24.24) | ||

| No | 171(74.35) | 75(75.76) | ||

| With nutritional disorders | 0.047 | 0.828 | ||

| Yes | 56(24.35) | 23(23.23) | ||

| No | 174(75.65) | 76(76.77) | ||

| With anxiety | 0.098 | 0.755 | ||

| Yes | 50(21.74) | 20(20.20) | ||

| No | 180(78.26) | 79(79.80) | ||

| Anesthesia time(h) | 0.138 | 0.710 | ||

| ≥2 | 112(48.70) | 46(46.46) | ||

| <2 | 118(51.30) | 53(53.54) | ||

| Surgical time(min) | 0.075 | 0.784 | ||

| ≥120 | 106(46.09) | 44(44.44) | ||

| <120 | 124(53.91) | 55(55.56) | ||

| Intraoperative hemorrhage(mL) | 0.104 | 0.747 | ||

| ≥300 | 109(47.39) | 45(45.45) | ||

| <300 | 121(52.61) | 54(54.55) | ||

| Surgical procedure | 0.250 | 0.617 | ||

| Total hip replacement | 130(56.52) | 53(53.54) | ||

| Hemiarthroplasty | 100(43.48) | 46(46.46) | ||

| Postoperative hypoxemia | 0.031 | 0.859 | ||

| Yes | 100(43.48) | 42(42.42) | ||

| No | 130(56.52) | 57(57.58) | ||

| Postoperative VAS score(points) | 0.138 | 0.711 | ||

| >3 | 105(45.65) | 43(43.43) | ||

| ≤3 | 125(54.35) | 56(56.57) | ||

| Postoperative CRP levels(mg/L) | 55.09 ± 12.17 | 54.86 ± 12.05 | 0.158 | 0.875 |

Comparison of clinical data between modeling and validation group.

3.2 Comparison of clinical data between sleep disorder group and non-sleep disorder group

Among the 230 patients, 69 experienced sleep disorders, with an incidence rate of 30.00%. There were significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, anesthesia time, surgery time, intraoperative bleeding volume, postoperative hypoxemia, postoperative VAS score, and postoperative CRP levels (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences in other clinical data between the two groups (p > 0.05). See Table 2.

Table 2

| Considerations | Sleep disorders group (n = 69) | No sleep disorder group (n = 161) | t/χ 2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 11.507 | 0.001 | ||

| ≥70 | 42(60.87) | 59(36.65) | ||

| <70 | 27(39.13) | 102(63.35) | ||

| Genders | 0.021 | 0.884 | ||

| Man | 40(57.97) | 95(59.01) | ||

| Woman | 29(42.03) | 66(40.99) | ||

| BMI(kg/m2) | 0.221 | 0.638 | ||

| <23 | 43(62.32) | 95(59.01) | ||

| ≥23 | 26(37.68) | 66(40.99) | ||

| ASA classification | 0.775 | 0.379 | ||

| Level II | 15(21.74) | 34(21.12) | ||

| Level III | 52(75.36) | 125(77.64) | ||

| Level IV | 2(2.90) | 2(1.24) | ||

| Hypertensive | 0.212 | 0.645 | ||

| Yes | 21(30.43) | 54(33.54) | ||

| No | 48(69.57) | 107(66.46) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.573 | 0.449 | ||

| Yes | 18(26.09) | 50(31.06) | ||

| No | 51(73.91) | 111(68.94) | ||

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 0.215 | 0.643 | ||

| Yes | 16(23.19) | 42(26.09) | ||

| No | 53(76.81) | 119(73.91) | ||

| Coronary heart disease | 0.748 | 0.387 | ||

| Yes | 10(14.49) | 31(19.25) | ||

| No | 59(85.51) | 130(80.75) | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.003 | 0.956 | ||

| Yes | 5(7.25) | 12(7.45) | ||

| No | 64(92.75) | 149(92.55) | ||

| Cerebral infarction | 0.013 | 0.910 | ||

| Yes | 5(7.25) | 11(6.83) | ||

| No | 64(92.75) | 150(93.17) | ||

| Smoking history | 0.215 | 0.643 | ||

| Yes | 16(23.19) | 42(26.09) | ||

| No | 53(76.81) | 119(73.91) | ||

| Drinking history | 0.256 | 0.613 | ||

| Yes | 15(21.74) | 40(24.84) | ||

| No | 54(78.26) | 121(75.16) | ||

| Type of disease | 2.905 | 0.088 | ||

| Aseptic necrosis of the femoral head | 10(14.49) | 20(12.42) | ||

| Intertrochanteric fracture of the femur | 21(30.43) | 34(21.12) | ||

| Femoral neck fracture | 38(55.07) | 107(66.46) | ||

| With cognitive impairment | 0.021 | 0.885 | ||

| Yes | 31(44.93) | 74(45.96) | ||

| No | 38(55.07) | 87(54.04) | ||

| With depression | 0.053 | 0.818 | ||

| Yes | 17(24.64) | 42(26.09) | ||

| No | 52(75.36) | 119(73.91) | ||

| With nutritional disorders | 0.072 | 0.789 | ||

| Yes | 16(23.19) | 40(24.84) | ||

| No | 53(76.81) | 121(75.16) | ||

| With anxiety | 0.122 | 0.727 | ||

| Yes | 14(20.29) | 36(22.36) | ||

| No | 55(79.71) | 125(77.64) | ||

| Anesthesia time(h) | 14.881 | <0.001 | ||

| ≥2 | 47(68.12) | 65(40.37) | ||

| <2 | 22(31.88) | 96(59.63) | ||

| Surgical time(min) | 14.519 | <0.001 | ||

| ≥120 | 45(65.22) | 61(37.89) | ||

| <120 | 24(34.78) | 100(62.11) | ||

| Intraoperative hemorrhage(mL) | 7.182 | 0.007 | ||

| ≥300 | 42(60.87) | 67(41.61) | ||

| <300 | 27(39.13) | 94(58.39) | ||

| Surgical procedure | 0.084 | 0.772 | ||

| Total hip replacement | 40(57.97) | 90(55.90) | ||

| Hemiarthroplasty | 29(42.03) | 71(44.10) | ||

| Postoperative hypoxemia | 14.238 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 43(62.32) | 57(35.40) | ||

| No | 26(37.68) | 104(64.60) | ||

| Postoperative VAS score(points) | 11.036 | <0.001 | ||

| >3 | 43(62.32) | 62(38.51) | ||

| ≤3 | 26(37.68) | 99(61.49) | ||

| Postoperative CRP levels(mg/L) | 58.42 ± 12.45 | 47.35 ± 11.52 | 6.517 | <0.001 |

Comparison of clinical data between the sleep disordered and non-sleep disordered groups.

3.3 Analysis of factors influencing postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery

Using whether patients with HICH had poor prognosis after burr hole drainage as the dependent variable (yes = 1, no = 0), and the aforementioned factors with differences as independent variables, the variable assignment method is shown in Table 3. Multivariate Logistic regression analysis results showed that age, anesthesia time, surgery time, intraoperative bleeding volume, postoperative hypoxemia, postoperative VAS score, and postoperative CRP levels were risk factors for postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery (p < 0.05). See Table 4.

Table 3

| Variable | Assignment method |

|---|---|

| Age | <70 years = 0, ≥ 70 years = 1 |

| Anesthesia time | ≥2 h = 0, <2 h = 1 |

| Surgical time | ≥120 min = 0, <120 min = 1 |

| Intraoperative hemorrhage | ≥300 mL = 0, <300 mL = 1 |

| Postoperative hypoxemia | no = 0, yes = 1 |

| Postoperative VAS score | >3 points = 0, ≤ 3 points = 1 |

| Postoperative CRP levels | Continuous variable |

Independent variable assignment methods.

Table 4

| Variable | β value | SE value | Wald χ2 value | p value | OR value | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.970 | 0.639 | 9.518 | 0.002 | 7.168 | 2.050–25.070 |

| Anesthesia time | 1.531 | 0.616 | 6.176 | 0.013 | 4.624 | 1.382–15.473 |

| Surgical time | 2.154 | 0.679 | 10.046 | 0.002 | 8.616 | 2.275–32.636 |

| Intraoperative hemorrhage | 2.686 | 0.663 | 16.382 | <0.001 | 14.624 | 3.989–53.607 |

| Postoperative hypoxemia | 2.752 | 0.658 | 17.504 | <0.001 | 15.678 | 4.318–56.917 |

| Postoperative VAS score | 1.642 | 0.644 | 6.495 | 0.011 | 5.164 | 1.461–18.251 |

| Postoperative CRP levels | 3.077 | 0.736 | 17.501 | <0.001 | 21.704 | 5.133–91.770 |

| Constant | −8.265 | 1.737 | 22.632 | <0.001 | <0.001 | - |

Analysis of factors affecting postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing HR with general anesthesia.

3.4 Establishment of a nomogram model for postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery

Based on the factors identified above, a nomogram model was constructed. The predicted probability was calculated as P = e^x / (1 + e^x), where x = −8.265 + 1.970 × age + 1.531 × anesthesia time + 2.154 × surgery time + 2.686 × intraoperative blood loss + 2.752 × postoperative hypoxemia + 1.642 × postoperative VAS score + 3.077 × postoperative CRP level. In this model, the most important influencing factor was postoperative CRP level. For each variable, a vertical line can be drawn to correspond to a specific score. The total score is the sum of the scores for each variable; a higher total score indicates a higher probability of bladder paralysis. For example, at a total score of 320 points, drawing a vertical line to the probability scale corresponds to a predicted probability of 72%. See Figure 2.

Figure 2

Nomogram modeling of postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia for HR.

3.5 Nomogram model for postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery in the modeling group

The AUC of the modeling group was 0.978 (95% CI: 0.962–0.995), the slope of the calibration curve was close to 1, and the H-L test was χ2 = 7.410, p = 0.762, indicating good consistency. See Figure 3.

Figure 3

Nomogram Model for postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery in the modeling group. (A) ROC curve for modeling group; (B) Modeling group calibration curves.

3.6 Nomogram model for postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery in the validation group

The AUC of the validation group was 0.972 (95% CI: 0.942–0.999); the slope of the calibration curve was close to 1, and the H-L test was χ2 = 7.342, p = 0.752, indicating good consistency. See Figure 4.

Figure 4

Nomogram model for postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery in the validation group. (A) ROC curve for the validation group; (B) Calibration curve for the validation group.

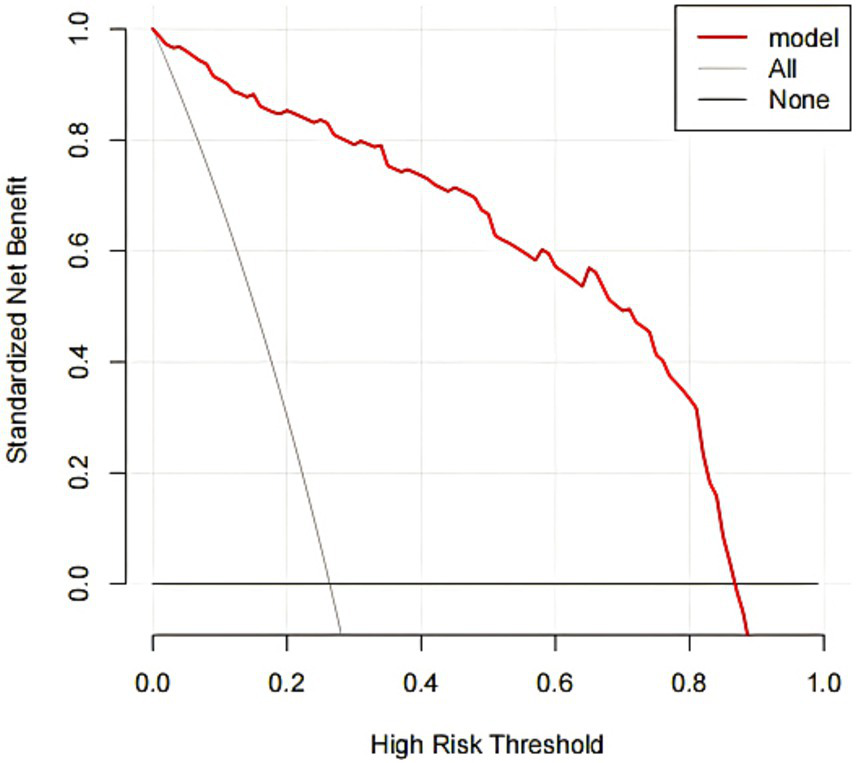

3.7 DCA curve of the nomogram model

The DCA curve showed that when the high-risk threshold probability was between 0.08 and 0.88, the clinical use value of using this nomogram model to evaluate postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery was higher. See Figure 5.

Figure 5

DCA curve for the nomogram.

4 Discussion

HR is a common clinical treatment method for diseases such as femoral head necrosis and femoral neck fractures, effectively improving patients’ clinical symptoms and quality of life (10). However, due to the stress and pain caused by surgery, patients are prone to postoperative sleep disorders, most of which occur on the first night after surgery. Patients exhibit difficulty falling asleep, shallow sleep, and morning fatigue, which can lead to hyperalgesia and cognitive impairment during the progression, affecting postoperative recovery (11, 12). Therefore, identifying the influencing factors of postoperative sleep disorders and taking measures to treat them can effectively improve patients’ prognosis.

This study screened seven influencing factors and analyzed their causes: (1) For older patients, various physiological functions gradually decline, reducing tolerance to anesthesia and surgery, and the central nervous system functions also degrade to varying degrees. This leads to a decrease in the content of neurotransmitters and receptors in the central system, causing brain energy metabolism disorders, and increasing the risk of postoperative sleep disorders. Studies have found that elderly patients are more likely to experience sleep disturbances after general anesthesia HR surgery, while maintaining a stable internal environment before surgery and removing factors that cause neural injury can effectively reduce the incidence of sleep disorders. (13, 14). (2) Longer anesthesia time also increases sleep disorders, as prolonged general anesthesia alters the patient’s hemodynamics, making them prone to hypotension, resulting in ischemia and hypoxia of brain tissues, affecting brain function and leading to postoperative sleep disorders. In addition, due to individual differences, not all patients can receive the same anesthetic drugs, and the duration of anesthetic administration can significantly increase the total body uptake of anesthesia drugs, which contributes to the increased risk of sleep disorders with prolonged general anesthesia (15). (3) The longer the surgery time, the more likely the patient is to experience intraoperative hypotension and hypoxemia, causing ischemic and hypoxic damage to brain tissues, increasing the likelihood of postoperative sleep disorders (16). (4) Excessive bleeding during HR surgery can cause blood pressure fluctuations and brain hypoxia. Studies have found that excessive bleeding during HR surgery can induce stress reactions, significantly increasing the expression of local inflammatory factors in blood and brain tissues, triggering neuroinflammation and leading to sleep disorders (17, 18). (5) Postoperative hypoxemia aggravates brain tissue stress, reducing blood oxygen saturation, hindering the tricarboxylic acid cycle, decreasing the synthesis of acetylcholine in the central system, and inducing brain cell hypoxia and edema, thereby affecting central nervous system function and increasing the risk of sleep disorders (19). (6) The stronger the postoperative pain, the more intense the patient’s tension and anxiety, directly affecting sleep quality, causing sleep function disorders, and increasing the risk of sleep disorders (20). (7) When CRP levels rise, it can disrupt the blood–brain barrier, and upon entering the brain, cause inflammatory stimulation to nerve cells, stimulate glial cells in the brain to release inflammatory factors, trigger neurotoxic reactions and increase the risk of postoperative sleep disorders (21). Clinically, for these patients, correcting electrolyte imbalances, improving the internal environment and hypoxemic conditions, and selecting appropriate pharmacological treatments can help reduce the risk of postoperative sleep disorders.

This study constructed a nomogram model for postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery. The AUC of the modeling group and validation group were 0.978 and 0.972, respectively, indicating high discrimination. The high values may be due to the relatively small sample size, and as this is a retrospective study, there may be bias in data selection. Further validation with an expanded sample size will be conducted. The slope of the calibration curve was close to 1, indicating good consistency between the model’s risk assessment and actual risk. Additionally, the DCA curve showed that when the high-risk threshold probability was between 0.08 and 0.88, the clinical use value of this nomogram model was high, helping clinicians assess the risk of postoperative sleep disorders based on influencing factors and timely prevention.

In addition, several variables that were initially thought to be associated with postoperative sleep disorders, including gender, BMI, ASA classification, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, cerebral infarction, smoking history, alcohol history, cognitive impairment, depression, nutritional disorder, and anxiety, were not found to be significantly associated with postoperative sleep disorders in our study (p > 0.05). This finding highlights that not all commonly considered clinical factors contribute to postoperative sleep disturbances in elderly patients undergoing hip replacement surgery under general anesthesia.

In summary, age, anesthesia time, surgery time, intraoperative bleeding volume, postoperative hypoxemia, postoperative VAS score, and postoperative CRP levels are influencing factors for postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia HR surgery. The constructed nomogram model shows good discrimination and consistency, predicting postoperative sleep disorder conditions. This study has several limitations. As a single-center, retrospective study with a relatively small sample size, the results may be subject to bias, and the limited sample size may have prevented the detection of some factors related to postoperative sleep disorders. In addition, due to individual differences in patients’ physical conditions, different anesthetic drugs were used, some of which may be associated with a higher risk of postoperative sleep disturbances. In future studies, we plan to expand the sample size and conduct prospective, multicenter studies to further validate our findings and explore other potential influencing factors.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Hunan Chest Hospital (no. 2022–08-797). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

GZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JC: Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Spichler-Moffarah A Rubin LE Bernstein JA O'Bryan J McDonald E Golden M . Prosthetic joint infections of the hip and knee among the elderly: a retrospective study. Am J Med. (2023) 136:100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.08.006

2.

Duan J Ju X Wang X Liu N Xu S Wang S . Effects of remimazolam and propofol on emergence agitation in elderly patients undergoing hip replacement: a clinical, randomized, controlled study. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2023) 17:2669–78. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S419146

3.

Ni J Zhou W Cen H Chen G Huang J Yin K et al . Evidence for causal effects of sleep disturbances on risk for osteoarthritis: a univariable and multivariable mendelian randomization study. Osteoarthr Cartil. (2022) 30:443–50. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2021.11.021

4.

Kaynar AM Lin C Sanchez AG Lavage DR Monroe A Zharichenko N et al . SuRxgWell: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of telemedicine-based digital cognitive behavioral intervention for high anxiety and depression among patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty surgery. Trials. (2023) 24:715. doi: 10.1186/s13063-023-07634-0

5.

Yang Y Wang T Guo H Sun Y Cao J Xu P et al . Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting postoperative delirium in patients with elderly hip fracture based on data collected on admission. Front Aging Neurosci. (2022) 14:914002. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.914002

6.

Liang J Zhang J Lou Z Tang X . Development and validation of a predictive nomogram for subsequent contralateral hip fracture in elderly patients within 2 years after hip fracture surgery. Front Med (Lausanne). (2023) 10:1263930. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1263930

7.

Huang J Li M Zeng X-W Qu G-S Lin L Xin X-M . Development and validation of a prediction nomogram for sleep disorders in hospitalized patients with acute myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2024) 24:393. doi: 10.1186/s12872-024-04074-9

8.

Anger M Valovska T Beloeil H Lirk P Joshi GP Van de Velde M et al . PROSPECT guideline for total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and procedure-specific postoperative pain management recommendations. Anaesthesia. (2021) 76:1082–97. doi: 10.1111/anae.15498

9.

Zhou C Li R Yang M Duan S Yang C . Psychological status of high school students 1 year after the COVID-19 emergency. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:729930. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.729930

10.

Salman LA Hantouly AT Khatkar H Al-Ani A Abudalou A Al-Juboori M et al . The outcomes of total hip replacement in osteonecrosis versus osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Orthop. (2023) 47:3043–52. doi: 10.1007/s00264-023-05761-6

11.

Hochreiter J Kindermann H Georg M Ortmaier R Mitterer M . Sleep improvement after hip arthroplasty: a study on short-stem prosthesis. Int Orthop. (2020) 44:69–73. doi: 10.1007/s00264-019-04375-1

12.

Lin X Pan M-J Wu X-Y Liu S-Y Wang F Tang X-H et al . Daytime dysfunction may be associated with postoperative delirium in patients undergoing total hip/knee replacement: the PNDABLE study. Brain Behav. (2023) 13:e3270. doi: 10.1002/brb3.3270

13.

Bischoff P Kramer TS Schröder C Behnke M Schwab F Geffers C et al . Age as a risk factor for surgical site infections: German surveillance data on total hip replacement and total knee replacement procedures 2009 to 2018. Euro Surveill. (2023) 28:1–9. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2023.28.9.2200535

14.

Martin R Clark N Baker P . Impact of age, sex and surgery type on engagement with an online patient education and support platform developed for total hip and knee replacement patients. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0269771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0269771

15.

Li Y-W Li H-J Li H-J Zhao B-J Guo X-Y Feng Y et al . Delirium in older patients after combined epidural-general Anesthesia or general Anesthesia for major surgery: a randomized trial. Anesthesiology. (2021) 135:218–32. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003834

16.

Zhang G Wang Z Wang D Jia Q Zeng Y . A systematic review and meta-analysis of the correlation between operation time and postoperative delirium in total hip arthroplasty. Ann Palliat Med. (2021) 10:10459–66. doi: 10.21037/apm-21-2190

17.

Raphael J Hensley NB Chow J Parr KG McNeil JS Porter SB et al . Red blood cell transfusion and postoperative delirium in hip fracture surgery patients: a retrospective observational cohort study. Anesthesiol Res Pract. (2021) 2021:8593257. doi: 10.1155/2021/8593257

18.

Romagnoli M Raggi F Roberti di Sarsina T Saracco A Casali M Grassi A et al . Comparison of a minimally invasive tissue-sparing posterior superior (TSPS) approach and the standard posterior approach for hip replacement. Biomed Res Int. (2022) 2022:3248526. doi: 10.1155/2022/3248526

19.

He L Zhang R Yin J Zhang H Bu W Wang F et al . Perioperative multidisciplinary implementation enhancing recovery after hip arthroplasty in geriatrics with preoperative chronic hypoxaemia. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:19145. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55607-8

20.

Lim EJ Koh WU Kim H Kim H-J Shon H-C Kim JW . Regional nerve block decreases the incidence of postoperative delirium in elderly hip fracture. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:1–10. doi: 10.3390/jcm10163586

21.

Rohe S Röhner E Windisch C Matziolis G Brodt S Böhle S . Sex differences in serum C-reactive protein course after Total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg. (2022) 14:48–55. doi: 10.4055/cios21110

Summary

Keywords

general anesthesia, hip replacement surgery, sleep disorders, influencing factors, column chart nomogram

Citation

Zhou G, Chen J and Zhang H (2025) The influencing factors of postoperative sleep disorders in elderly patients undergoing hip replacement surgery under general anesthesia and the construction and validation of a nomogram prediction model. Front. Neurol. 16:1655523. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1655523

Received

13 July 2025

Revised

30 October 2025

Accepted

12 November 2025

Published

27 November 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Qi Chen, Chongqing University, China

Reviewed by

Vesna D. Dinic, Clinical Center Niš, Serbia

Christian Bohringer, UC Davis Medical Center, United States

Qunying Fang, University of Science and Technology of China, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhou, Chen and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hui Zhang, bobozhan980@sina.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.