Abstract

Objective:

Use of the Pipeline embolization device (PED) for treatment of ruptured complex intracranial aneurysms (IAs) remains controversial due to higher thromboembolic and hemorrhagic complications compared to balloon-assisted coiling. We present our experience using the PED for ruptured complex IAs and focus on the safety, effectiveness, and follow-up results.

Methods:

Consecutive 46 patients with ruptured complex IAs who had undergone PED deployment from January 2019 to December 2023 at our neurosurgical center were retrospectively enrolled. Patient demographics, aneurysm characteristics, procedural complications, clinical and angiographic follow-up outcomes were reviewed.

Results:

A total of 46 patients were analyzed with a mean age of 55.8 ± 13.4 years, including 30(65.2%) females. WFNS grades were I in 27 patients (58.7%), II in 10 (21.7%), III in 5 (10.9%), IV in 2 (4.3%), and V in 2 (4.3%). The ruptured aneurysms included 12 (26.1%) saccular, 23 (50.0%) blister-like, 10 (21.7%) dissecting, and 1(2.2%) fusiform. The average size of IAs was 4.3 ± 2.9 mm. PED deployment was technically successful in all patients and adjunctive coiling was performed in 44(95.7%) patients. The rate of procedural-related complications was 13.0% (6/46), including 2 hemorrhagic and 4 ischemic complications. One patient died of rerupture of aneurysm (1/46, 2.2%), and 95.3% of patients (41/43) had favorable outcomes at the 90-day follow-up. Among 40 available cases, complete aneurysm occlusion was obtained in 38 cases (95.0%, 38/40) at a mean follow-up of 7.5 months.

Conclusion:

Treatment of ruptured complex IAs with the PED was associated with acceptable complication rates, high complete occlusion rates, and good clinical outcomes. Therefore, PED may be a safe and effective option for ruptured IAs that were difficult to treat by conventional endovascular and surgical approaches. However, larger and comparative studies with long-term follow-up are needed to confirm this result.

1 Introduction

Flow diverters (FDs) have been widely used to treat unruptured intracranial aneurysms (IAs), particularly those with challenging morphologies such as large or giant wide-neck, dissecting, or fusiform aneurysms (1–3). Among these FDs, the Pipeline Embolization Device (PED) has garnered significant attention, with many studies highlighting its safety and high efficacy (4–6).

However, the use of PED for acutely ruptured IAs remains controversial. The necessity of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) to prevent stent thrombosis may increase the risk of hemorrhagic complications in subsequent invasive procedures, such as extraventricular drain (EVD) placement, craniotomy for decompression, or hematoma evacuation. Additionally, the risk of rebleeding after flow diversion is non-negligible, as the aneurysm is not immediately occluded.

Despite these limitations, the PED has been increasingly utilized to treat a subset of ruptured complex aneurysms that are difficult to manage with traditional clipping or coiling, and some studies have shown promising results (7, 8). However, the data remain limited. In this study, we report our experience with the Classical PED and PED Flex [45.7% (21/46) VS 54.3% (25/46)] in the treatment of acutely ruptured complex IAs. Our aim was to evaluate the safety, effectiveness, and follow-up outcomes of PED in the management of ruptured IAs.

2 Methods

2.1 Patients selection

This study included 46 consecutive patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) secondary to ruptured complex aneurysms who were treated by PED placement (with or without adjunctive coiling) at our neurosurgical center between January 2019 and December 2023 (Supplementary Figure 1). Complex aneurysms were defined as aneurysms that were difficult to treat with conventional endovascular and surgical approaches, including blister-like aneurysms, dissecting aneurysms, fusiform aneurysms, large wide-neck saccular aneurysms (maximum diameter≥10 mm), and small wide-neck saccular aneurysms (diameter≤5 mm). Approval of the study protocol was obtained from the research ethics committee of our hospital, and all patients or their relatives had signed informed consent.

Patients were examined by non-contrast computed tomography (CT) to confirm SAH and the presence of hydrocephalus prior to the procedure. The need for EVD placement was assessed based on altered consciousness, ventricular dilatation, and hemorrhage size. If necessary, EVD was usually placed before loading the patient with DAPT.

2.2 Data collection and clinical assessment

For each patient, we recorded demographic data, initial neurological conditions, amount of SAH, morphology and location of the ruptured aneurysms, procedural details, clinical outcome, and follow-up angiographic results. The patient’s initial neurological condition was evaluated using World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) grading system, while the severity of SAH was classified according to the modified Fisher Scale (mFS).

2.3 Antiplatelet therapy

Patients received a loading dose of 300 mg aspirin and 300 mg clopidogrel orally or via nasogastric tube 4 h before the procedure. 5%Tirofiban (0.08ug/kg/min, Grandpharma Company, Wuhan, China) was pumped intravenously immediately after PED placement and continued for 24 h.

For patients without dual antiplatelet pretreatment, a bolus of tirofiban (5ug/kg, 5%Tirofiban) was injected slowly through the guiding catheter over a 3 min period immediately after PED deployment and a maintenance dose of 5% tirofiban (0.08 ug/kg/min) was pumped continuously for 24 h. A loading dose of 300 mg aspirin and 300 mg clopidogrel was conducted 4 h before the cessation of tirofiban.

On the next day, dual antiplatelet agents (100 mg aspirin and 75 mg clopidogrel) continued for 3 months and then, aspirin was used alone (100 mg daily) for 6 months. Aspirin and clopidogrel response testing was not mandatory.

2.4 Timing of endovascular treatment

Given that aneurysmal rebleeding constitutes a leading cause of mortality after SAH, occurring most frequently within the first 24 h, our center has adopted ultra-early treatment (≤24 h) as the goal of treatment.

2.5 Interventional procedure

Endovascular procedures were performed through a right femoral artery approach using a short femoral 8-F sheath under general anesthesia. During the procedure, 3,000 IU heparin/500 mL saline was continuously dripped through the guiding catheter. An 8F Envoy guiding catheter (Cordis, United States) and 6F Navien (Medtronic, United States) intermediate catheter forming a coaxial system was inserted into target artery. The PED was deployed through a Marksman microcatheter (Medtronic, United States) or Phenom (Medtronic, USA) to cover the neck of the aneurysm. The diameter and length of the PED was assessed on angiography according to the size of the parent vessel. For aneurysms treated with additional coiling through a left transfemoral route using a 5-F femoral artery short sheath and a 5F Envoy guiding catheter (Cordis, United States), a microcatheter was placed inside the aneurysm dome, followed by partially deployment of PED to temporarily jail the microcatheter. Aneurysm coiling was subsequently performed and then the PED was completely deployed (Figures 1, 2).

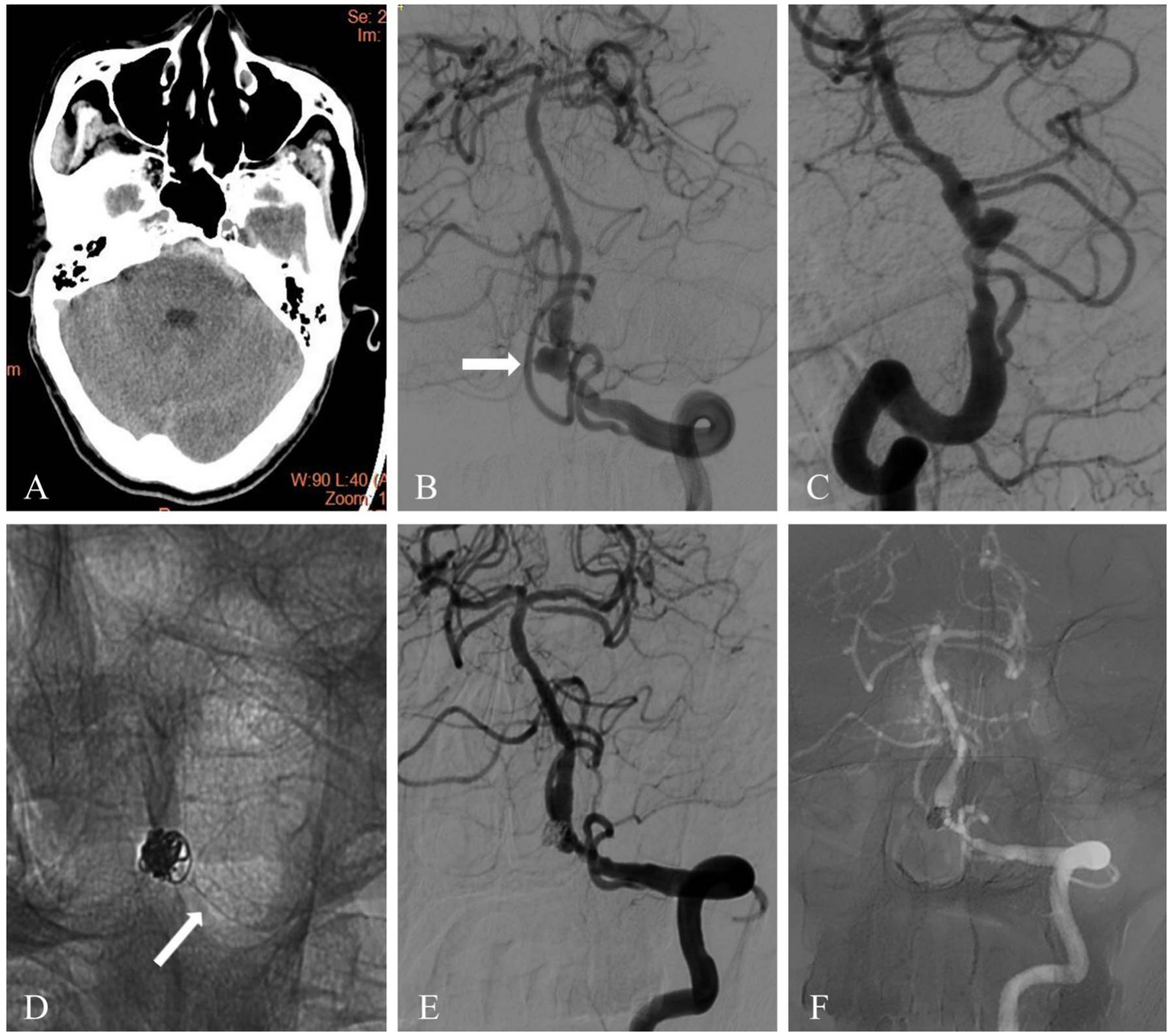

Figure 1

A ruptured blood blister aneurysm was treated with PED and adjunctive coiling. (A) Head computed tomography image of a 51-year-old patient showed acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. (B,C) Diagnostic cerebral angiography revealed a blood blister aneurysm located on the supraclinoid segment of the right internal carotid artery (white arrow). (D) The aneurysm was treated with PED and adjunctive coiling. Fluoroscopic image showed the flow diverter and coil mass (white arrow). (E) Immediate angiography after PED deployment showed complete occlusion (white arrow). (F) Follow-up angiography at 10 months showed complete occlusion of the aneurysm (white arrow).

Figure 2

A 61-year-old patient presented with subarachnoid hemorrhage and a vertebrobasilar junction dissecting aneurysm. (A) Head computed tomography showed acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. (B,C) Diagnostic cerebral angiography revealed a dissecting aneurysm located in the vertebrobasilar junction (white arrow). (D) The dissecting aneurysm was treated with coiling and a PED. Unsubstracted angiogram showed the flow diverter (white arrow) and coil mass. (E) Immediate post-treatment angiography showed complete occlusion of aneurysm and patency of parent vessel. (F) Follow-up angiography at 8 months showed complete occlusion of aneurysm and parent vessel patency.

2.6 Clinical and radiological follow-up

Clinical outcome was evaluated with modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores (9). A favorable outcome was defined as a mRS score of 0 to 2 and a poor outcome was defined as a mRS score of 3 to 6 at 90 days after the procedure.

The angiographic follow-up was scheduled at 6 and 12 months with digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Aneurysm occlusions were evaluated according to the O’Kelly Marotta (OKM) grading scale: A, total filling (>95%); B, subtotal filling (5–95%); C, neck remnant (<5%); D, no filling (0%) (10). All clinical and imaging data were blindly measured by two independent clinicians who have 10 years of experience and any disagreements were resolved by a third physician with 15 years’ experience.

3 Results

3.1 Patients and aneurysm characteristics

A consecutive 46 patients with 52 aneurysms treated with PED were included in the study (Table 1). In 3 patients of multiple aneurysms, 6 neighboring unruptured aneurysms were also covered by the same PED. There were 16 males and 30 females, with a mean age of 55.8 ± 13.4 years (range 28-83 years).

Table 1

| Variables | Value |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 46 |

| Age(years, mean ± SD) | 55.8 ± 13.4 |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 30 (65.2) |

| WFNS grade, n (%) | |

| 1 | 27 (58.7) |

| 2 | 10 (21.7) |

| 3 | 5 (10.9) |

| 4 | 2 (4.3) |

| 5 | 2 (4.3) |

| Fisher grade | |

| 1 | 3 (6.5) |

| 2 | 15 (32.6) |

| 3 | 23 (50.0) |

| 4 | 5 (10.9) |

| Type of aneurysm, n (%) | |

| Saccular | 12 (26.1) |

| Blister | 23 (50.0) |

| Dissecting | 10 (21.7) |

| Fusiform | 1 (2.2) |

| Aneurysm location, n (%) | |

| Middle cerebral artery (MCA) | 3 (6.5) |

| Anterior communicating artery (ACOA) | 1 (2.2) |

| Internal carotid artery (ICA) | 33 (71.7) |

| Vertebral artery (VA) | 7 (15.2) |

| Basilar artery (BA) | 2 (4.3) |

| Aneurysm size [mean (range), mm] | 4.3 (1.5–13.2) |

| Saccular | 6.2 (4.2–13.1) |

| Blister | 2.9 (1.5–4.9) |

| Dissecting | 6.4 (5.3–11.8) |

| Fusiform | 13.2 |

| Treatment type, n (%) | |

| PED + coil | 44 (95.7) |

| PED only | 2 (4.3) |

Patient and aneurysm characteristics.

The ruptured aneurysms included 12 (26.1%) saccular, 23 (50.0%) blister-like, 10 (21.7%) dissecting, and 1(2.2%) fusiform. Thirty-seven ruptured aneurysms (80.4%) were located in the anterior circulation, and 9(19.6%) in the posterior circulation. Aneurysm size ranged from1.5 to 13.2 mm, with a mean of 4.3 ± 2.9 mm. If fusiform aneurysm was excluded (only one case), mean aneurysm size for saccular, blister, and dissecting aneurysms was 6.2 ± 3.0 mm (range4.2–13.1 mm), 2.9 ± 1.1 mm (range 1.5–4.9 mm), and 6.4 ± 3.5 mm (range 5.3–11.8), respectively. WFNS grades were I in 27 patients (58.7%), II in 10 (21.7%), III in 5 (10.9%), IV in 2 (4.3%), and V in 2 (4.3%). Eighteen patients (39.1%) had a lesser hemorrhage (mFS 1 or 2).

The deployment of PED was technically successful in all 46 patients and adjunctive coiling was used in 95.7% (44/46). The mean delay from bleed to PED placement was 1.8 days (range 0–4 days). Five patients underwent EVD before DAPT initiation, and none required VP shunt. A total of 49 Pipeline embolization devices were placed in 46 patients (mean 1.07 devices/patient; range 1–2).

3.2 Complications

As shown in Table 2, procedural-related clinical complications were recorded in 6 cases (2 hemorrhagic and 4 ischemic complications, 6/46, 13.0%) and resulted in permanent neurological morbidity in 2 (2/46, 4.3%) and death in 1(1/46, 2.2%).

Table 2

| Complications | Intra-procedural | Post-procedural | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic, n (%) | 4 (8.7) | ||

| Transient | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.2) | |

| Permanent | 0 | 2 (4.3) | |

| Hemorrhagic, n (%) | |||

| Rebleeding | 0 | 1 (2.2) | 2 (4.3) |

| Perforation | 1 (2.2) | 0 | |

Procedure related complications.

Intraoperative aneurysmal rupture was observed in one case. A 37-year-old female patient presented with a ruptured wide-neck saccular aneurysm located in the left ophthalmic artery segment. The aneurysm was measured at 4.0 mm and 3.2 mm in width and height respectively, with neck size 3.9 mm. The patient was treated with PED Flex adjunctive coiling. During the procedure, the coil perforated the aneurysm wall and caused a small amount of SAH. The patient recovered well after immediate coiling. In another case, a patient with a dissection aneurysm of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) was treated with PED Flex without adjunctive coiling. On the seventh day after treatment, the patient experienced rebleeding from the aneurysm and subsequently died.

During the procedure, in-stent thrombosis occurred in one patient and was immediately resolved with intravenous tirofiban. This patient suffered no symptoms. Additionally, three patients had an ischemic stroke after the procedure. One patient presented with a ruptured saccular aneurysm of the right posterior communicating artery (PCOM), accompanied by proximal stenosis of the parent vessel. Successful PED placement with partial coiling of the aneurysm was performed. Twenty-four hours post-procedure, the patient suffered from dysarthria. By immediately pumping tirofiban intravenously, the patient recovered well (mRS = 0). Another patient with a dissecting aneurysm, measured 10.1 mm × 5.8 mm in the M1 segment of left middle cerebral artery (MCA), was treated with PED Flex adjunctive coil emblization without complications. Two days postoperatively, the patient developed right-sided hemiparesis. The brain CT showed a left basal ganglia ischemia, which may be perforator infarction caused by PED implantation. The patient was managed with conservative treatment and had a permanent neurological deficit at discharge (mRS = 3). The third patient developed a small infarction on the second day following an uneventful PED adjunctive coil treatment for a large saccular aneurysm of the left PCOM. Platelet function testing revealed clopidogrel resistance, prompting us to switch to ticagrelor. The patient was discharged with an mRS score of 3.

3.3 Clinical and angiographic outcomes

As shown in Table 3, clinical follow-up data were available for 95.6% of patients (n = 43/45). Of the 43 patients, 41 (95.3%) had a good clinical outcome and 2 (4.7%) had a poor clinical outcome at the 90-day follow-up.

Table 3

| Outcomes | Value |

|---|---|

| Clinical follow-up, n (%) | 43 (95.6) |

| Mean follow-up time (months) | 3 |

| Clinical outcome, n (%) | |

| mRS 0–2 | 41 (95.3) |

| mRS 3–6 | 2 (4.7) |

| Angiographic follow-up, n (%) | 40 (88.9) |

| Mean follow-up time (months) [mean (range)] | 7.5 (6–15) |

| Occlusion grade, n (%) | |

| Total filling (>95%) | 0 (0.0) |

| Subtotal filling (5–95%) | 2 (5.0) |

| Neck remnant (<5%) | 0 (0.0) |

| No filling (0%) | 38 (95.0) |

Clinical and angiographic outcomes after flow diversion in ruptured aneurysms.

Angiographic follow-up evaluations were available in 40(88.9%) of 45 surviving patients, with a mean follow-up time of 7.5 months (range 6–15 months). Grade D (no filling) was noted in 38/40 aneurysms (95.0%), Grade B (subtotal filling) was noted in 2 patients (5.0%, 2/40).

A mild degree of in-stent stenosis (<30%) was detected at 6-months follow-up angiography in one patient, which did not cause any symptoms.

3.4 Comparison between this study and preiovusly reported studies

Table 4 compared this study with previous studies (11–15). The current total complication rate (13.0%) and complete occlusion rate (95.0%) were similar to the results of recently published studies (11–15). The good clinical outcome rate was 95.3% in this study, higher than those of previous studies (11–15), which ranged from 68.9 to 86.3%. The rebleeding rate in our study was 2.2%, in the range from 0 to 5% of published case series (11–15).

Table 4

| Study | No. of Pts | Complications Ischemic hemorrhagic total (%) (%) (%) |

Rebleeding rate (%) |

Mean angiographic follow-up (months) |

Complete occlusion rate (%) |

mRS 0–2 (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madaelil et al. (11) | 126 | 5% | 9% | 12% | 5% | 6 | 90% | 81% |

| Cagnazzo et al. (12) | 223 | 8% | 7% | 17.8% | 4% | 9.6 | 89% | 83% |

| Gopinathan et al. (13) | 22 | 9% | 4.5% | 13.6% | 0 | NA | 95% | 86.3% |

| Almatter et al. (14) | 45 | 11.1% | 2.2% | 13.3% | 0 | NA | 94.6% | 68.9% |

| Cohen et al. (15) | 76 | 7.9% | 0 | 7.9% | 0 | 12 | 95% | 81.6% |

| Current study | 46 | 8.7% | 4.3% | 13.0% | 2.2% | 7.5 | 95% | 95.3% |

Comparison with previously reported studies.

4 Discussion

In this study, we report our experience with the PED for acutely ruptured complex aneurysms, which are challenging to treat by endovascular coiling or clipping. In our series, the rebleeding rate was only 2.2% (1/46), and favorable clinical outcomes were 95.3% (41/43). At follow-up, complete occlusion was achieved in 95.0% (38/40). These results suggest that PED may be a safe and effective option for ruptured aneurysms that are considered difficult with conventional approaches.

However, the use of PED for ruptured IAs is controversial due to the necessity of DAPT and the delay in the aneurysm occluding, which may increase the risk of rebleeding. In the literature, the rebleeding rate was varied after FD deployment, ranging from 0 to 11% (11, 12, 15, 16). Cohen et al. (15) explored effective rebleeding protection of FD stents for acutely ruptured aneurysms. Their study included 76 patients and showed none of the patients had rebleed despite a very low rate of immediate complete exclusion. In a meta-analysis of 223 patients with ruptured aneurysms treated with FD stents, the aneurysm rebleeding rate was 4% (12). Similarly, in another meta-analysis, Madaelil et al. (11) reported aneurysm rerupture occurred in 5% of cases following FD placement. However, Ten Brinck et al. (16) conducted a retrospective study, which included 44 patients from 6 different centers, and found that the rate of rebleeding was relatively higher at 11%. In comparison, in our series, rerupture occurred in 2.2% of patients. The lower rebleed rate in our study was likely due to the fact that the majority of patients (95.7%, 44/46) had adjunctive coiling in the same session (17). Yang et al. (18) found that adjunctive use of coiling achieved higher incidence of immediate complete occlusion and no rebleed was encountered. Gopinathan et al. (13) reported their five-year experience and showed that none of the aneurysms rebled after flow-diversion and almost 73% (16/22) of patients were treated with adjunctive coiling.

Up to now, the optimal antiplatelet regimen for FD treatment in the acute rupture setting has no consensus (19). Aspirin plus clopidogrel was the most common agents used (7, 8, 20). However, because resistance to clopidogrel is commonly encountered, prasugrel and ticagrelor have also been used instead of clopidogrel in previous studies (15, 21, 22). In 2021, Gopinathan et al. (13) published a series of 22 patients with ruptured IAs treated with FDs. The patients received Ticagrelor(77%) and Prasugrel(15%) instead of clopidogrel as their antiplatelet regimen. Another alternative approach was that a maintenance dose of tirofiban was administered immediately after PED placement and continued for 12 h after the procedure (23–25). The advantages of tirofiban include its short half-life (2–4 h), rapid onset of action (about 5 min), and very potent inhibitory effect on platelets. The present study includes two different antiplatelet therapy regimens. In the first protocol, patients were loaded with 300 mg aspirin and 300 mg clopidogrel 4 h prior to the procedure. 5%Tirofiban (0.08 ug/kg/min) was administered intravenously immediately after PED placement and continued for 24 h. In the second protocol, patients without dual antiplatelet pretreatment were loaded with tirofiban (5ug/kg, 5%Tirofiban) slowly through the guiding catheter immediately after PED deployment and followed by a maintenance dose of tirofiban (0.08 ug/kg/min) for 24 h. A loading dose of 300 mg aspirin and 300 mg clopidogrel was overlapped with tirofiban infusion 4 h before the cessation of tirofiban. In our series, rebleeding was observed in only 1 patient (2.2%) and ischemic complications were record in 4 cases (8.7%). Our series suggests that the current antiplatelet protocol may be a viable option for patients with acute SAH. Recently, with the advancement of surface-modified technology, new FDs (such as PED-Shield, p48 MW and p64 MW HPC devices) have been used to treat acute ruptured aneurysms by single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT). Manning et al. (26) evaluated the safety and efficacy of PED-Shield for treatment of ruptured aneurysms with SAPT. They found no symptomatic ischaemic or haemorrhagic complications occurred in the patients without receiving post-operative heparin infusion. Lobsien D et al. (27) reported a 3-center experience with ruptured IAs treated with flow diverters with hydrophilic coating (p48 MW HPC and p64 MW HPC) under SATP. The follow-up imaging revealed all the stents were patent. Only one device-related thrombotic complication occurred. The COATING study by Laurent Pierot et al. (28) was the first prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial designed to compare the incidence of thromboembolic complications between patients treated with bare p64 MW under dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) and those treated with coated p64 MW HPC under single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT). The primary endpoint was the number of diffusion-weighted imaging lesions visualized via 3 T MRI within 48 h (±24 h) after the procedure. Preliminary outcome demonstrated no statistically significant difference between groups [2.1 (1.0, 4.0) vs. 2.5 (1.0, 5.0), p = 0.72], suggesting that drug-coated stents combined with SAPT are non-inferior to bare stents combined with DAPT for preventing perioperative thromboembolic events in unruptured or recurrent intracranial aneurysms. In the future, FDs with antithrombogenic properties may have greater prospects. However, clinical evidence of using such FDs in the treatment of acutely ruptured IAs is still lacking and large-sample prospective studies are needed.

In our series, the treatment-related complication rate was13.0% (6/46). A favorable clinical outcome was achieved in 95.3% of the patients and the rate of complete aneurysm occlusion was 95% at a mean 7.5-month follow up. These findings are aligned with previous studies. In a meta-analysis of 20 observational studies by Cagnazzo et al. (12), including 223 patients, the rate of complete/near-complete occlusion was nearly 90% associated with a complication rate of 18%. Good clinical outcome was achieved in 83% of the patients. Mahajan et al. (21) described a series of 16 SAH patients with Surpass FD treatment and reported 15 patients (94%) achieved favorable clinical outcome at 3 months. The complete occlusion rate on angiography was 87% (13/15) at 3 and 6 months and three patients (19%) developed transient hemiparesis. Gopinathan et al. (13) reported a similar rate of complete aneurysm occlusion achieved in 95%, with a good clinical outcome rate of 86.3%. Procedure- related adverse events were seen in 3 patients (13.64%). In our study, the high complete occulusion rate may be related to the following reasons. First, blister-like aneurysms account for 50% of the cases. In treating small-sized aneurysms, flow divert devices are more likely to cause high occlusion rate. Second, the combination of flow diverts with coiling is also a contributing factor to the high occlusion rate.

4.1 Limitations

Our study has several limitations, which should be considered while interpreting the results. First, it was a single-center retrospective study and thus there was inherited patient selection bias. Second, due to the small sample size and heterogeneity of aneurysms, we cannot make generalization about our results. Third, the follow-up period was short and a long-term follow-up is required. Despite the encouraging results in the present study, larger and comparative studies with long-term follow-up are needed to confirm its safety and efficacy.

5 Conclusion

Treatment of ruptured complex aneurysms with the PED was associated with acceptable complication rates, high complete occlusion rates, and good clinical outcomes. Therefore, PED may be a safe and effective option for ruptured complex IAs that were difficult to treat by conventional endovascular and surgical approaches. However, larger and comparative studies with long-term follow-up are needed to confirm this result.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Shijiazhuang People’s Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

Y-FH: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation. QZ: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Resources, Validation, Formal analysis, Project administration. X-JZ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation, Software, Validation, Visualization, Formal analysis. D-LZ: Resources, Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Visualization, Data curation. LY: Conceptualization, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Resources, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by the 2020 Hebei Medical Science Research Project Plan (Project no. 20201408) and Hebei Province key research and development plan project (Project no. 22377753D).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2025.1673718/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Wakhloo AK Gounis MJ . Revolution in aneurysm treatment: flow diversion to cure aneurysms: a paradigm shift. Neurosurgery. (2014) 61:111–20. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000392,

2.

Awad AJ Mascitelli JR Haroun RR De Leacy RA Fifi JT Mocco J . Endovascular management of fusiform aneurysms in the posterior circulation: the era of flow diversion. Neurosurg Focus. (2017) 42:E14. doi: 10.3171/2017.3.FOCUS1748,

3.

Chalouhi N Tjoumakaris S Starke RM Gonzalez LF Randazzo C Hasan D et al . Comparison of flow diversion and coiling in large unruptured intracranial saccular aneurysms. Stroke. (2013) 44:2150–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001785,

4.

Kallmes DF Hanel R Lopes D Boccardi E Bonafe A Cekirge S et al . International retrospective study of the pipeline embolization device: a multicenter aneurysm treatment study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. (2015) 36:108–15. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4111

5.

Yu SC Kwok CK Cheng PW Chan KY Lau SS Lui WM et al . Intracranial aneurysms: midterm outcome of pipeline embolization device--a prospective study in 143 patients with 178 aneurysms. Radiology. (2012) 265:893–901. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120422

6.

Becske T Kallmes DF Saatci I McDougall CG Szikora I Lanzino G et al . Pipeline for uncoilable or failed aneurysms: results from a multicenter clinical trial. Radiology. (2013) 267:858–68. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13120099,

7.

Zhong W Kuang H Zhang P Yang X Luo B Maimaitili A et al . Pipeline embolization device for the treatment of ruptured intracerebral aneurysms: a Multicenter retrospective study. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:675917. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.675917

8.

Lin N Brouillard AM Keigher KM Lopes DK Binning MJ Liebman KM et al . Utilization of pipeline embolization device for treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: US multicenter experience. J Neurointerv Surg. (2015) 7:808–15. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011320,

9.

Hong KS Saver JL . Quantifying the value of stroke disability outcomes: WHO global burden of disease project disability weights for each level of the modified Rankin scale. Stroke. (2009) 40:3828–33. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.561365,

10.

O’Kelly CJ Krings T Fiorella D Marotta TR . A novel grading scale for the angiographic assessment of intracranial aneurysms treated using flow diverting stents. Interv Neuroradiol. (2010) 16:133–7. doi: 10.1177/159101991001600204,

11.

Madaelil TP Moran CJ Cross DT Kansagra AP . Flow diversion in ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a Meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. (2017) 38:590–5. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5030,

12.

Cagnazzo F di Carlo DT Cappucci M Lefevre PH Costalat V Perrini P . Acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysms treated with flow-diverter stents: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. (2018) 39:1669–75. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5730,

13.

Gopinathan A Jain S Lwin S Teo K Yang C Nga V et al . Flow diversion in acute sub arachnoid haemorrhage: a single Centre five year experience. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2021) 30:105910. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.105910

14.

AlMatter M Aguilar Pérez M Hellstern V Mitrovic G Ganslandt O Bäzner H et al . Flow diversion for treatment of acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a single Center experience from 45 consecutive cases. Clin Neuroradiol. (2020) 30:835–42. doi: 10.1007/s00062-019-00846-5,

15.

Cohen JE Gomori JM Moscovici S Kaye AH Shoshan Y Spektor S et al . Flow-diverter stents in the early management of acutely ruptured brain aneurysms: effective rebleeding protection with low thromboembolic complications. J Neurosurg. (2021) 135:1394–401. doi: 10.3171/2020.10.JNS201642,

16.

Ten Brinck MFM Jager M de Vries J Grotenhuis JA Aquarius R Morkve SH et al . Flow diversion treatment for acutely ruptured aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg. (2020) 12:283–8. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-015077,

17.

Zhang H Ren J Wang J Lv X . The off-label uses of pipeline embolization device for complex cerebral aneurysms: mid-term follow-up in a single center. Interv Neuroradiol. (2022) 31:158–67. doi: 10.1177/15910199221148800,

18.

Yang C Vadasz A Szikora I . Treatment of ruptured blood blister aneurysms using primary flow-diverter stenting with considerations for adjunctive coiling: a single-Centre experience and literature review. Interv Neuroradiol. (2017) 23:465–76. doi: 10.1177/1591019917720805,

19.

Linfante I Mayich M Sonig A Fujimoto J Siddiqui A Dabus G . Flow diversion with pipeline embolic device as treatment of subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to blister aneurysms: dual-center experience and review of the literature. J Neurointerv Surg. (2017) 9:29–33. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012287,

20.

Podlasek A Al Sultan AA Assis Z Kashani N Goyal M Almekhlafi MA . Outcome of intracranial flow diversion according to the antiplatelet regimen used: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. (2020) 12:148–55. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-014996,

21.

Mahajan A Das B Narang KS Jha AN Singh VP Sapra H et al . Surpass flow diverter in the treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms-a single-center experience. World Neurosurg. (2018) 120:e1061–70. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.011,

22.

Parthasarathy R Gupta V Gupta A . Safety of prasugrel loading in ruptured blister like aneurysm treated with a pipeline device. Br J Radiol. (2018) 91:20170476. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20170476,

23.

Chalouhi N Zanaty M Whiting A Tjoumakaris S Hasan D Ajiboye N et al . Treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms with the pipeline embolization device. Neurosurgery. (2015) 76:165–72. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000586,

24.

Guerrero WR Ortega-Gutierrez S Hayakawa M Derdeyn CP Rossen JD Hasan D et al . Endovascular treatment of ruptured vertebrobasilar dissecting aneurysms using flow diversion embolization devices: single-institution experience. World Neurosurg. (2018) 109:e164–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.125,

25.

Goertz L Dorn F Kraus B Borggrefe J Schlamann M Forbrig R et al . Safety and efficacy of the Derivo embolization device for the treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg. (2019) 11:290–5. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014166

26.

Manning NW Cheung A Phillips TJ Wenderoth JD . Pipeline shield with single antiplatelet therapy in aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: multicentre experience. J Neurointerv Surg. (2019) 11:694–8. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014363,

27.

Lobsien D Clajus C Behme D Ernst M Riedel CH Abu-Fares O et al . Aneurysm treatment in acute SAH with hydrophilic-coated flow diverters under single-antiplatelet therapy: a 3-Center experience. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. (2021) 42:508–15. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6942,

28.

Pierot L Lamin S Barreau X Berlis A Ciceri E Cohen JE et al . Coating (coating to optimize aneurysm treatment in the new flow diverter generation) study. The first randomized controlled trial evaluating a coated flow diverter (p64 MW HPC): study design. J Neurointerv Surg. (2023) 15:684–8. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2022-018969,

Summary

Keywords

pipeline embolization device, flow diversion, ruptured, complex intracranial aneurysms, antiplatelet therapy

Citation

Han Y-F, Zhao Q, Zhang X-J, Zhang D-L and Yang L (2026) Utilization of pipeline embolization device for treatment of ruptured complex intracranial aneurysms. Front. Neurol. 16:1673718. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1673718

Received

26 July 2025

Revised

20 November 2025

Accepted

08 December 2025

Published

13 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Peter Vajkoczy, Charité University Medicine Berlin, Germany

Reviewed by

Eugene Lin, St. Vincent Mercy Medical Center, United States

Victor Schulze-Zachau, University Hospital of Basel, Switzerland

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Han, Zhao, Zhang, Zhang and Yang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lei Yang, leiyang10066@sina.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.