Abstract

Background:

Stroke may bring psychological and cognitive challenges. Previous research revealed that several mediators, such as coping style and optimism, might be associated with cognitive impairment in patients with stroke.

Objective:

This study aims to establish a structural equation model of the relationships among optimism, coping style, and cognitive impairment, and to explore the mediating role of coping style in the association between optimism on cognitive impairment.

Methods:

Using a cross-sectional survey, 1,000 hospitalized patients with stroke from China were studied. The collected data were analyzed using correlation analyses, structural equation modeling, and regression analyses. SPSS 26.0 was used to construct logistic regression and decision tree models, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to evaluate the predictive performance of the two models. Structural equation modeling was used to examine the links among dispositional optimism, coping style, and cognitive impairment. The robustness of the model was verified using the bootstrap method.

Results:

The average scores of positive coping, negative coping, optimism, and cognitive impairment in patients with stroke were 19.26 ± 9.68, 10.49 ± 7.24, 23.22 ± 4.58, and 0.87 ± 1.69, respectively. The analysis of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve showed that the predictive performance of logistic regression was slightly better than that of the decision tree model. SEM findings indicated that coping style serves as a significant mediator in the association between optimism and cognitive impairment.

Conclusion:

Both coping style and optimism were found to be significantly associated with cognitive impairment in patients with stroke, with coping style serving as a mediator of the association between optimism and cognitive impairment in this patient population. These cross-sectional findings suggest that, for inpatients with stroke, medical staff should consider paying attention to their cognitive function and assessing their psychological health status, such as their optimism and coping strategies, which may help inform the selection of supportive interventions that may benefit cognitive health.

1 Introduction

1.1 The burden of post-stroke cognitive impairment

Stroke is the second leading cause of death worldwide, with a very high disability rate. In China, there are over 3 million new cases of stroke every year (1). In recent years, with the improvement of medical technology, the survival rate and survival period of stroke patients have gradually been extended, but the longer survival period is also accompanied by sequelae that affect their quality of life (2). During the process of coping with the disease, stroke patients often experience negative emotions such as pessimism, disappointment, and low mood, which may be associated with poorer recovery and disease prognosis (3). Research shows that up to one-third of stroke patients will suffer from one or more social and psychological disorders after onset (4). Munthe mentioned in a review that the prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and severe cognitive impairment at 3 months after stroke is 14–29% and 11–42%, respectively (5). Overall, cognitive impairment shows a high incidence among stroke patients. Since stroke is an acute stress event that causes great physical and mental effects, it also indicates that, compared with neurodegenerative cognitive disorders, patients with post-stroke cognitive impairment may experience greater psychological pressure, depression, anxiety, and persistent psychological problems (6), which may potentially affect their subsequent rehabilitation process and quality of daily life.

1.2 The potential role of optimism and coping styles

According to Engel’s Biopsycho-Social Model (BPSM), proposed in 1977, biological and psychological factors play a significant role in the processes and outcomes of diseases (7). Given the severe psychological impact of stroke, patients often exhibit low levels of optimism. For stroke patients, the probability of experiencing negative emotions after a stroke is 20–60%, which may be related to an increase in disability and mortality rates (8). Coping style refers to the individual’s coping behaviors and cognitive activities toward stressful events, and different coping styles lead to different behavioral outcomes and have varying impacts on individuals (9). The stress response model proposed by Andreotti (10) suggests that excessive stress is associated with impaired neurocognitive function, and a person’s ability to cope with stress may influence the relationship between stress and neuropsychological outcomes, such as cognitive decline (11). In contrast, a meta-analysis (12) showed that, in addition to biological factors such as age, sex, and demographic characteristics, social relationship factors and neuropsychiatric symptoms are also influencing factors for cognitive impairment, and some positive psychological factors are associated with a lower risk of cognitive impairment. Scholars have pointed out that higher levels of optimism and better health behaviors are related to better health status, and these health behaviors may also be beneficial for cognitive function (13, 14). Therefore, optimism and coping style represent promising research foci in understanding and potentially mitigating cognitive impairment in stroke patients.

1.3 The rationale and novelty of the current investigation

The majority of existing studies examine the relationship between optimism or coping strategies and post-stroke cognitive function separately (15, 16). There is a lack of research on whether coping strategies mediate the relationship between optimism and cognitive impairment by integrating the three into an integrated model, particularly in stroke patients. This study aims to investigate the relationship between optimism, coping styles, and cognitive impairment. Additionally, we attempt to better understand the underlying psychological mechanisms of cognitive function in patients with stroke to provide insights for future prevention strategies. Based on previous theories and research, we propose study hypotheses as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The study hypotheses.

Hypotheses:

H1: Optimism is hypothesized to be positively associated with positive coping.

H2: Optimism is hypothesized to be negatively associated with negative coping.

H3: Positive coping is hypothesized to be negatively associated with cognitive impairment.

H4: Negative coping is hypothesized to be positively associated with cognitive impairment.

H5: Optimism is hypothesized to be negatively associated with cognitive impairment.

H6: Coping style is hypothesized to mediate the association between optimism and cognitive impairment.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Research participants

This study used a stratified sampling method. First, we selected a representative comprehensive hospital from each district of Shenyang City, and these hospitals were all designated treatment hospitals on the “Emergency treatment for stroke in Shenyang” network. This sampling approach aimed to obtain a sample from established and standardized stroke care settings within the region. Second, within these hospitals, we recruited patients who met the inclusion criteria during the data collection period. A total of 1,000 valid questionnaires were collected, with an effective response rate of 92.5%. According to the Kendall criterion in statistics, the sample size should be at least 5–10 times the number of independent variables. This research questionnaire comprised a total of 36 items, and after screening, a sample of 1,000 participants was included. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) ≥18 years old; (2) patients diagnosed with stroke in clinical settings; (3) clear consciousness and stable condition; and (4) patients who provided informed consent and voluntarily participated in this study. All participants signed informed consent forms. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with other serious acute diseases requiring strict bed rest; (2) patients with cognitive impairment, auditory dysfunction, or other conditions affecting the completion of the questionnaire; and (3) patients with a confirmed diagnosis of a mental disorder.

Investigators conducting this research were trained in appropriate content and questionnaire scoring methods, and the target and content of these questionnaires were described to eligible patients in a uniform manner. All patients provided informed consent prior to study participation. Questionnaires were distributed, and data were collected through one-on-one interviews and reviewed on the spot. Collected questionnaires were individually numbered, and a double-entry approach was employed to ensure that all data entry was accurate. The Ethics Committee of Shenyang Medical College approved the present research.

2.2 Research tools

2.2.1 Demographic characteristics

Demographic data include sex, age, ethnicity, height, weight, literacy level, BMI, marital status, work situation, area of residence, family monthly income, chronic disease, first onset of stroke, passive smoking, smoking, alcohol consumption, daily exercise time, and type of stroke.

2.2.2 The six-item life orientation test-revised (LOT-R)

LOT-R is a self-assessment scale used to measure optimistic personality (17). It consists of 10 items, 4 of which are filler items designed to mask the fundamental purpose of the test. Of the six rating items, three assess optimism and three assess pessimism. Respondents indicate their agreement with each item on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The total score is calculated by adding the raw scores of the optimistic items and the inverted raw scores of the pessimistic items. The score range is from zero to 24, and a higher score indicates a higher level of optimism, while a lower score indicates a lower level of optimism, commonly referred to as pessimism. This established measure demonstrates robust psychometric properties, such as good reliability, validity (both discriminant and convergent), and stable item performance. Previous research supports the temporal stability of LOT-R-assessed optimism (14). In the current study, the scale yielded a Cronbach’s α of 0.93.

2.2.3 The simplified coping style questionnaire (SCSQ)

Coping styles were evaluated using the 20-item Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire (SCSQ) (18). This self-report instrument measures two dimensions: positive and negative coping. Respondents indicate how frequently they employ each strategy on a 4-point scale (1 = never to 4 = always). The total SCSQ score, calculated by subtracting the negative dimension standard score from the positive one, reflects an individual’s propensity toward positive coping (higher scores indicate greater use). Although the SCSQ was initially developed in a general population, it has been widely used and has established good psychometric properties in populations with stroke or other chronic diseases (19). In the current sample, Cronbach’s α was 0.93 overall, with subscale α values of 0.94 (positive coping) and 0.85 (negative coping).

2.2.4 Ascertain dementia 8 (AD8)

The AD8 scale is a rapid screening tool developed by the University of Washington in the United States in 2005. It includes eight items: judgment, hobbies, repeating the same thing repeatedly, learning how to use tools, appliances, or small tools, forgetting the correct year and month, dealing with complex financial problems, remembering an agreed-upon time, and thinking and memorizing. Each item requires the test subject to answer “no change,” “changed,” or “do not know.” Answering “changed” earns 1 point, while answering “no change” or “do not know” earns 0 points. We consider an AD8 score of 2 or higher as a significant abnormality, indicating the presence of significant cognitive impairment. As a short and rapid questionnaire used for general screening, The AD8 is highly correlated with clinical neuroassessment (19) and other screening tools such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (20), and has been widely used in large-scale cohort studies of the general population and surgical patients (21). However, the optimal threshold for the AD8 may vary depending on different uses or age groups, but in various studies (22), AD8 scores ≥ 2 are more sensitive to early cognitive changes in the Asian population, especially Chinese populations (23, 24). In subsequent research, it would be more scientific to choose appropriate cutoff scores based on different populations. In addition, relevant studies have shown that serum biomarkers may also be associated with early cognitive changes in emergency patients (25), such as serum uric acid levels. Therefore, in subsequent studies, laboratory test indicators can be further combined with evaluation to more accurately screen patients with cognitive impairment.

2.3 Statistical analysis

The study was statistically analyzed using SPSS, with a two-tailed p < 0.05 indicating a statistically significant difference. T-test and one-way ANOVA were used to describe the distribution and significant differences of optimism, coping style, and cognitive impairment in cerebrovascular patients with different demographic characteristics. Spearman correlation analysis was used to assess the correlation between optimism, coping style, and cognitive impairment in cerebrovascular patients.

A decision tree is a machine learning algorithm that offers advantages such as visualization, ease of interpretation, and high accuracy. Studies have shown that decision trees can achieve higher predictive performance for disease progression compared to traditional logistic regression models. Therefore, this study will use logistic regression and a decision tree to construct a risk prediction model for cognitive impairment in stroke patients, and compare the predictive performance of the two, in order to guide clinical identification and prevention of high-risk patients with cognitive impairment. Structural equation model analysis was performed using AMOS, with optimism as the independent variable, cognitive impairment as the dependent variable, and coping style as the mediating variable; parameter estimation was performed using the maximum likelihood method. SEM was preferred over traditional regression-based mediation analysis: (a) it allows for the simultaneous estimation of all hypothesized paths within a single, comprehensive model, providing a more holistic view of the relationships; (b) it explicitly accounts for measurement error in the latent constructs, leading to more accurate parameter estimates; and (c) it provides goodness-of-fit indices to evaluate how well the proposed theoretical model reproduces the observed data, which regression methods cannot offer. Our mediation analysis aims to test the plausibility of a theoretical model and examine indirect associations based on established psychological theory, rather than to establish causal pathways. Previous studies have also shown that this method can elucidate the relationships between variables in cross-sectional studies (26, 27).

3 Results

3.1 Demographic characteristics

Screening for post-stroke cognitive impairment using the AD8 scale, based on established criteria and previous studies (28), we use a total score of ≥2 as the cutoff value to classify the presence of cognitive impairment. This method is particularly suitable for our study population, as the AD8 relies on informant reporting, and with fewer questions and shorter answer times, it is suitable for large-scale screening. A total of 1,000 patients with stroke completed the questionnaire survey, of which 180 patients (18%) had cognitive impairment, and their AD8 score was greater than or equal to 2 points. Moreover, monthly income, smoking, alcohol consumption, the first onset of stroke, and the type of stroke showed a statistically significant difference in positive coping scores (p < 0.05). Marital status, BMI, monthly income, diabetes, smoking, alcohol consumption, first onset of stroke, the type of stroke, and coronary heart disease showed a statistically significant difference in negative coping scores (p < 0.05). Age, literacy level, marital status, monthly income, home location, hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, fatty liver, alcohol consumption, physical activity time, first onset of stroke, and type of stroke showed a statistically significant difference in optimism (p < 0.05). Age, BMI, marital status, home location, diabetes, fatty liver, alcohol consumption, smoking, physical activity time, and type of stroke showed a statistically significant difference in cognitive impairment (p < 0.05). The demographic characteristics of the subjects with and without cognitive impairment are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Characteristic | N (%) | Coping style | Optimism | Cognitive impairment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive coping | Negative coping | ||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 588 (58.8%) | 18.68 ± 9.55 | 10.20 ± 7.12 | 23.15 ± 4.69 | 0.80 ± 1.69 |

| Female | 412 (41.2%) | 19.84 ± 9.82 | 10.77 ± 7.49 | 23.22 ± 4.70 | 0.85 ± 1.77 |

| Age | |||||

| <60 | 178 (17.8%) | 21.10 ± 9.76 | 10.85 ± 7.63 | 24.47 ± 4.23 | 0.35 ± 1.00 |

| ≥60 | 822 (82.2%) | 18.78 ± 9.61 | 10.36 ± 7.21 | 22.94 ± 4.74** | 0.90 ± 1.80* |

| Ethnic group | |||||

| Han Chinese | 962 (96.2%) | 19.21 ± 9.70 | 10.45 ± 7.29 | 23.20 ± 4.71 | 0.83 ± 1.72 |

| Others | 38 (3.8%) | 17.82 ± 9.07 | 10.08 ± 7.11 | 22.76 ± 4.06 | 0.58 ± 1.68 |

| BMI | |||||

| <24.0 | 458 (45.8%) | 20.37 ± 9.49 | 11.66 ± 7.48 | 23.79 ± 4.61 | 0.72 ± 1.63* |

| ≥24.0 | 542 (54.2%) | 18.12 ± 9.71 | 9.38 ± 6.93** | 22.66 ± 4.70 | 0.90 ± 1.79 |

| Literacy level | |||||

| High school and below | 804 (80.4%) | 18.73 ± 9.72 | 10.45 ± 7.19 | 22.93 ± 4.73 | 0.84 ± 1.76 |

| Above high school | 196 (19.6%) | 20.88 ± 9.27 | 10.36 ± 7.63 | 24.19 ± 4.36** | 0.71 ± 1.56 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 880 (88.0%) | 19.29 ± 9.73 | 10.56 ± 7.34 | 23.31 ± 4.62 | 0.75 ± 1.63 |

| Others | 120 (12.0%) | 18.12 ± 9.20 | 9.48 ± 6.70* | 22.24 ± 5.05* | 1.31 ± 2.23** |

| Work situation | |||||

| Retirement | 800 (80.0%) | 18.95 ± 9.70 | 10.45 ± 7.23 | 23.00 ± 4.73 | 0.86 ± 1.77 |

| Others | 200 (20.0%) | 19.97 ± 9.55 | 10.36 ± 7.46 | 23.90 ± 4.44 | 0.64 ± 1.52 |

| Monthly income | |||||

| ≤4,000 | 560 (56.0%) | 17.30 ± 9.75 | 9.81 ± 7.05 | 22.48 ± 4.85 | 0.86 ± 1.81 |

| >4,000 | 440 (44.0%) | 21.51 ± 9.04** | 11.22 ± 7.48** | 24.06 ± 4.32** | 0.77 ± 1.60 |

| Home location | |||||

| Rural | 198 (19.8%) | 21.26 ± 9.70 | 13.27 ± 6.94 | 23.20 ± 5.43 | 1.06 ± 1.76 |

| Urban | 802 (80.2%) | 18.63 ± 9.60 | 9.73 ± 7.19 | 23.17 ± 4.49** | 0.76 ± 1.71* |

| Hypertension | |||||

| No | 387 (38.7%) | 19.39 ± 9.53 | 10.49 ± 7.26 | 23.37 ± 4.48 | 0.78 ± 1.58 |

| Yes | 613 (61.3%) | 19.00 ± 9.76 | 10.39 ± 7.29 | 23.06 ± 4.81* | 0.84 ± 1.80 |

| Diabetes | |||||

| No | 770 (77.0%) | 20.03 ± 9.68 | 10.93 ± 7.45 | 23.54 ± 4.55 | 0.71 ± 1.59 |

| Yes | 230 (23.0%) | 16.21 ± 9.06 | 8.73 ± 6.38** | 21.97 ± 4.95* | 1.18 ± 2.06** |

| Has thrombolysis been administered | |||||

| No | 856 (85.6%) | 19.76 ± 9.64 | 10.64 ± 7.44 | 23.46 ± 4.56 | 0.73 ± 1.59 |

| Yes | 144 (14.4%) | 15.57 ± 9.07 | 9.14 ± 6.03** | 21.47 ± 5.06** | 1.36 ± 2.27 |

| Fatty liver | |||||

| No | 940 (94.0%) | 19.39 ± 9.68 | 10.42 ± 7.32 | 23.37 ± 4.56 | 0.71 ± 1.58 |

| Yes | 60 (6.0%) | 15.46 ± 8.78 | 10.55 ± 6.53 | 20.18 ± 5.64** | 2.45 ± 2.78** |

| Smoking status | |||||

| No | 718 (71.8%) | 20.02 ± 9.81 | 10.78 ± 7.50 | 23.39 ± 4.67 | 0.76 ± 1.71 |

| Yes | 282 (28.2%) | 16.94 ± 8.94* | 9.52 ± 6.58** | 22.63 ± 4.69 | 0.96 ± 1.75** |

| Passive smoking | |||||

| No | 715 (71.5%) | 19.64 ± 9.61 | 10.52 ± 7.37 | 23.43 ± 4.68 | 0.84 ± 1.79 |

| Yes | 285 (28.5%) | 17.94 ± 9.73 | 10.19 ± 7.04 | 22.54 ± 4.65 | 0.76 ± 1.54 |

| Alcohol consumption | |||||

| No | 737 (73.7%) | 20.56 ± 9.78 | 11.23 ± 7.56 | 23.83 ± 4.46 | 0.62 ± 1.49 |

| Yes | 263 (26.3%) | 15.21 ± 8.16** | 8.19 ± 5.85** | 21.34 ± 4.83* | 1.36 ± 2.15** |

| Physical activity time | |||||

| ≤1 h | 442 (44.2%) | 17.27 ± 9.42 | 10.17 ± 7.18 | 22.20 ± 5.05 | 1.24 ± 2.11 |

| >1 h | 558 (55.8%) | 20.65 ± 9.62 | 10.63 ± 7.35 | 23.95 ± 4.23** | 0.48 ± 1.23** |

| First onset of stroke | |||||

| No | 404 (40.4%) | 16.47 ± 8.86 | 9.31 ± 6.70 | 22.18 ± 4.86 | 0.98 ± 2.01 |

| Yes | 596 (59.6%) | 20.97 ± 9.78** | 11.18 ± 7.56** | 23.85 ± 4.45** | 0.70 ± 1.49 |

| Type of stroke | |||||

| Ischemic stroke | 752 (75.2%) | 20.04 ± 9.96 | 8.00 ± 6.03 | 23.59 ± 4.60 | 0.76 ± 1.70* |

| TIA | 248 (24.8%) | 20.56 ± 8.33* | 7.96 ± 5.65** | 24.47 ± 5.33* | 0.56 ± 1.74 |

Demographic characteristics of stroke patients.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

3.2 Correlation between optimism, coping style, and cognitive impairment

Spearman correlation analysis was used to assess optimism, positive coping, negative coping, and cognitive impairment scales. The results show that optimism was significantly positively correlated with positive coping (r = 0.684, p < 0.01), optimism was significantly negatively correlated with negative coping (r = −0.434, p < 0.01), and positive coping was significantly negatively correlated with cognitive impairment (r = −0.193, p < 0.01; Table 2).

Table 2

| Variables | Optimism | Positive coping | Negative coping | Cognitive impairment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimism | 1 | |||

| Positive coping | 0.684** | 1 | ||

| Negative coping | 0.434** | 0.670** | 1 | |

| Cognitive impairment | −0.363** | −0.193** | −0.005 | 1 |

Correlation between optimism, coping style, and cognitive impairment.

**p < 0.01.

3.3 Logistic regression analysis of factors influencing cognitive impairment in stroke patients

Using cognitive impairment in stroke patients as the dependent variable (0 = no, 1 = yes), binary logistic regression analysis was conducted with 10 statistically significant factors identified in univariate analysis as independent variables. The results showed that marital status, age, family location, alcohol consumption, exercise time, diabetes, and type of stroke were the main factors influencing cognitive impairment in elderly stroke patients. Among them, marital status, alcohol consumption, smoking, and ischemic stroke type were risk factors for cognitive impairment, while residing in a city, exercising for more than 1 h per day, and being under 60 years of age were protective factors, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

| Variable | Classification | B | SE | Wald | p | OR | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | Married | 0.606 | 0.267 | 5.149 | <0.05 | 1.833 | (1.086, 3.093) |

| Other | |||||||

| Age | <60 | 0.745 | 0.272 | 7.531 | <0.01 | 2.170 | (1.237, 3.587) |

| ≥60 | |||||||

| BMI | <24.0 | −0.020 | 0.024 | 0.678 | 0.410 | 0.980 | (0.935, 1.028) |

| ≥24.0 | |||||||

| Home location | Rural | −0.667 | 0.235 | 8.017 | <0.01 | 0.513 | (0.324, 0.815) |

| City | |||||||

| Smoking status | No | 0.032 | 0.226 | 0.02 | 0.888 | 1.032 | (0.663, 1.607) |

| Yes | |||||||

| Alcohol consumption | No | 0.763 | 0.218 | 12.196 | <0.01 | 2.145 | (1.398, 3.291) |

| Yes | |||||||

| Physical activity time | ≤1 h/day | −0.868 | 0.202 | 18.467 | <0.01 | 0.420 | (0.283, 0.624) |

| >1 h/day | |||||||

| Suffering from diabetes | No | 0.325 | 0.225 | 2.091 | 0.148 | 1.384 | (0.891, 2.151) |

| Yes | |||||||

| Suffering from fatty liver | No (control) | 0.76 | 0.363 | 4.388 | <0.05 | 2.137 | (1.050, 4.350) |

| Yes | |||||||

| Types of stroke | TIA (control) | −0.98 | 0.220 | 19.883 | <0.01 | 0.375 | (0.244, 0.577) |

| Ischemic stroke |

Logistic regression analysis of factors influencing cognitive impairment in stroke patients.

3.4 Decision tree model score of influencing factors of cognitive impairment in stroke patients

Ten independent variables with statistical significance in univariate analysis, such as age, BMI, marital status, home location, smoking, alcohol consumption, exercise time, diabetes, fatty liver, and stroke type, were included in the decision tree model, as shown in Figure 2. The decision tree model has four layers and 11 nodes in total, including six terminal nodes. Three explanatory variables are screened out, such as alcohol consumption, exercise time, and the type of stroke. The daily exercise time is an important predictor of cognitive impairment in stroke patients.

Figure 2

Decision tree model of cognitive impairment in elderly stroke patients.

3.5 Comparison of the prediction effect between logistic regression and the decision tree model

By drawing the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, the predictive effect of logistic regression and decision tree models on cognitive impairment in elderly stroke patients was analyzed. The results showed that the sensitivity of logistic regression (56.5%) was lower than that of the decision tree model (58.4%), and the specificity (85.3%) was higher than that of the decision tree model (74.9%). The area under the ROC curve (AUC) value of logistic regression was 0.762 (95% CI: 0.717–0.807), while the AUC value of the decision tree model was 0.732 (95% CI: 0.717–0.807). The prediction effect of logistic regression was slightly better than that of the decision tree model, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

ROC curve of logistic regression and decision tree model.

3.6 Factors influencing cognitive impairment in stroke patients

All variables related to cognitive impairment in the above statistical analysis were summarized to obtain demographic characteristics in Figure 4. There is a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) in the impact of age, BMI, marital status, and family location on cognitive impairment. Factors related to disease and lifestyle behavior, such as diabetes, fatty liver, alcohol consumption, time of physical activity, and type of stroke, have statistically significant effects on cognitive impairment (p < 0.05), while positive coping has a negative impact on cognitive impairment, and negative coping has a positive impact on cognitive impairment. This means that stroke patients who adopt negative coping strategies may have lower cognitive function than those who adopt negative coping strategies. Meanwhile, more optimistic stroke patients may have better cognitive abilities.

Figure 4

Factors influencing cognitive impairment in patients with stroke.

3.7 Structural equation modeling analysis of optimism, coping style, and cognitive impairment

A structural equation model was constructed using AMOS 24.0, with optimism of patients with stroke as the independent variable, positive and negative coping as mediating variables, and cognitive impairment as the dependent variable. The measurement model was assessed to confirm the adequacy of the latent variable structures. Standardized regression weights for all indicators are presented in Table 4, all of which were statistically significant and exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.50, supporting convergent validity.

Table 4

| Latent variable | Observation indicators/sub-scales | Standardized regression weights | Standard error (S.E.) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimism | Item 1 | 0.57 | 0.078 | <0.01 |

| Item 2 | 0.85 | 0.095 | <0.01 | |

| Item 3 | 0.82 | 0.095 | <0.01 | |

| Item 4 | 0.64 | 0.065 | <0.01 | |

| Item 5 | 0.83 | 0.089 | <0.01 | |

| Item 6 | 0.62 | 0.060 | <0.01 | |

| Coping style | Positive coping | 0.84 | 0.029 | <0.01 |

| Negative coping | 0.71 | 0.041 | <0.01 | |

| AD8 | Item 1 | 0.52 | 0.098 | <0.01 |

| Item 2 | 0.68 | 0.090 | <0.01 | |

| Item 3 | 0.71 | 0.092 | <0.01 | |

| Item 4 | 0.69 | 0.089 | <0.01 | |

| Item 5 | 0.60 | 0.080 | <0.01 | |

| Item 6 | 0.70 | 0.099 | <0.01 | |

| Item 7 | 0.72 | 0.095 | <0.01 | |

| Item 8 | 0.65 | 0.094 | <0.01 |

Standardized regression weights for all indicators.

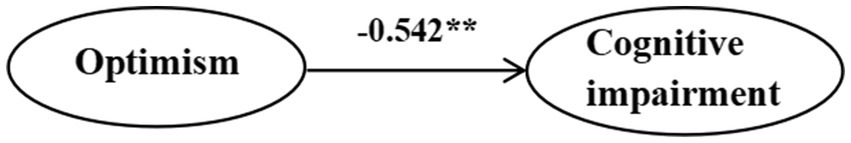

The model results indicate that optimism not only directly affects cognitive impairment but also has a significant indirect impact on cognitive impairment through coping strategies. The direct pathway of optimism affecting cognitive impairment is shown in Figure 5, and its goodness of fit is shown in Table 5, indicating that optimism has a significant impact on cognitive impairment (β = −0.542, p < 0.01). The indirect pathway from optimism to cognitive impairment mediated by coping strategies is shown in Figure 6, with goodness of fit χ2/df < 5, p < 0.05, CFI = 0.942, NFI = 0.925, IFI = 0.942, TLI = 0.905, RMSEA = 0.064. The results showed that positive coping had a negative effect on cognitive impairment (β = −0.24, p < 0.001), while negative coping had a positive effect on cognitive impairment (β = 0.32, p < 0.001). The path coefficient of optimism on cognitive impairment decreases with the mediating effect of coping strategies (β = −0.35, p < 0.001).

Figure 5

Direct effect of optimism and cognitive impairment in stroke patients.

Table 5

| Indicators | χ 2/df | CFI | RMSEA | TLI | IFI | NFI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard value | <5 | >0.9 | <0.10 | <0.05 | >0.9 | >0.9 | <0.05 |

| Price | 4.118 | 0.942 | 0.064 | 0.905 | 0.942 | 0.925 | 0.038 |

Structural equation model fitting index.

Figure 6

Structural equation modeling of coping style in optimism and cognitive impairment in cerebrovascular patients.

4 Discussion

4.1 Incidence of cognitive impairment in stroke patients

The incidence of PSCI in this study was 18%, slightly lower than the previously reported incidence of 20–40% in a meta-analysis and cohort studies (29, 30). This difference may be due to the following reasons. First, as this study mainly investigated stroke patients in the hospital, hospitalized patients generally have a shorter course of illness. However, studies have shown (31) that with the passage of time and the long-term damage to cerebral blood vessels caused by stroke, cognitive impairment symptoms only appear a few months after the occurrence of stroke. This may be one of the reasons why the results of this study are lower than those of other studies. In addition, the sample of this study came from designated stroke treatment hospitals in Shenyang, which have higher medical standards for stroke and may have prevented cognitive impairment to some extent. Furthermore, the differences in the number of selected samples and regions are also common reasons for the differences in research results.

4.2 Influencing factors of cognitive impairment in stroke patients

The results of this study showed that demographic variables, such as age, BMI, marital status, and family location, and factors related to disease and behavior lifestyle, such as diabetes, fatty liver, alcohol consumption, time of physical activity, smoking, and stroke type, have statistically significant effects on cognitive impairment, while positive coping was negatively correlated with cognitive impairment, and negative coping was positively correlated with it. Moreover, older age was linked to more severe cognitive impairment, which is closely related to neurobiological changes, brain structure degradation, lifestyle and environmental factors, and psychological and social factors (32). Individuals with a higher BMI also exhibit poorer cognitive ability, consistent with the findings of Beeri (33), which showed that higher BMI variability is associated with a faster decline in cognitive function. This may be related to progressive homeostasis imbalance in stroke patients with abnormal BMI, promoting harmful processes that lead to anoxic cell dysfunction, such as neuronal death, nerve degeneration, and other related factors. The degree of cognitive impairment of stroke patients is still different between urban and rural areas. The degree of cognitive impairment of stroke patients in rural areas is higher. The reason may be due to the lack of social structure resources in rural areas (34). In addition, stroke patients with a per capita monthly income of less than 4,000 yuan in this study have a higher probability of cognitive impairment, which has been demonstrated in previous articles (35). The reason is that the cognitive burden caused by poverty is equivalent to losing a whole night’s sleep. This kind of mental pressure will reduce the individual’s cognitive performance and may aggravate wrong decision-making and financial choices, so that the individual will fall into a worse psychological state. Depression in patients with physical activity for more than 1 h was less likely to be associated with cognitive impairment symptoms, which may be because exercise increases the release of some neurotransmitters, improves negative emotions, and reduces cognitive impairment symptoms (36). Previous studies have shown that alcohol consumption is a risk factor for cognitive impairment, which is consistent with the results of this study. Alcohol consumption was identified as a risk factor. These studies have pointed out that long-term heavy alcohol consumption will lead to changes in brain structure and function, such as hippocampal atrophy and white matter fiber damage, which are closely related to the decline of cognitive ability (37).

4.3 Predictive performance analysis

A decision tree is a machine learning method based on tree structure, mainly used for classification and regression tasks, capable of handling non-linear relationships (38). The decision tree model constructed in this study consists of four layers, 11 nodes, and six endpoints. Three explanatory variables were selected: alcohol consumption, daily exercise duration, and stroke type were jointly predicted by the two models. The difference in analysis between the two models is due to the different testing methods (39). The logistic regression model can accurately determine the linear relationship between independent and dependent variables by outputting OR values, while the decision tree model can display the interaction between different variables, gradually reduce the sample size during the analysis process, and screen for variables with more clinical significance. The results are expressed in the form of images, which is convenient for clinical application. However, using a single method may have limitations. Combining a logistic regression model with a decision tree model analysis is expected to provide a more comprehensive and accurate analysis of the influencing factors of cognitive impairment in stroke patients and provide more targeted guidance for clinical practice. Therefore, this study used a logistic regression model and a decision tree model to analyze the influencing factors of cognitive impairment in stroke patients in order to provide a reliable basis for clinical prevention and treatment of cognitive impairment after stroke.

4.4 Association between optimism and cognitive impairment in stroke patients

Spearman’s correlation analysis showed that there was a negative correlation between optimism and cognitive impairment in stroke patients, that is, the higher the optimism score, the lower the cognitive impairment score, which was consistent with the cross-sectional study (14). The results of regression analysis and structural equation modeling showed that the optimistic status of Chinese stroke patients was directly associated with the level of cognitive impairment. Theoretical models suggest that optimism is linked to positive health in indirect and direct ways. Health behavior is considered an indirect way. Optimism is associated with better health behaviors in the elderly, such as more active exercise and smoking cessation (40). Individuals with higher optimism tend to report healthier diets and more effective stress management (14, 40). Studies also suggest that more optimistic individuals may have better self-regulation ability and experience higher levels of positive emotions. More optimistic individuals tend to have more confidence in the future to deal with difficult living conditions and work harder to solve problems, but they are also more willing to adjust when the goal cannot be achieved (41). Additionally, optimistic individuals are also more likely to seek social support, which is a key environmental factor associated with cognitive preservation.

4.5 Relationship between coping styles and cognitive impairment in stroke patients

Palamarchuk proposed a multi-level model to explain the role of cognitive processing, decision-making, and behavior in coping with stress (42). Cognitive introspection is associated with better cognitive performance, which suggests that positive coping strategies are correlated with better mental health and cognitive ability. This is completely consistent with the results of this study. This study incorporates the variables of optimism, coping, and cognitive outcomes that were previously discussed separately into a unified theoretical framework and validates the mediation model, providing a more refined map for understanding the process by which post-stroke psychosocial factors affect cognitive health. Our results suggest that clinical evaluation should not be limited to neurological deficits alone. Routine screening of patients’ optimistic tendencies and coping strategies can help identify individuals at higher risk of cognitive decline. Targeted psychological interventions, such as positive psychology interventions to enhance optimism or cognitive-behavioral therapy to train adaptive coping skills, can be integrated into stroke rehabilitation programs as potential non-pharmacological cognitive protection strategies. Longitudinal studies are needed in the future to confirm causal directions. Meanwhile, intervention studies can examine whether enhancing optimism and adaptive coping strategies can effectively improve cognitive outcomes. In addition, exploring the relationship between biological markers and these psychological variables will provide a deeper insight into the mechanisms of the heart–brain connection.

4.6 Mediating role of coping style between optimism and cognitive impairment

We demonstrate that coping strategies play an important mediating role in optimism and cognitive function. Poor optimism in stroke patients may trigger negative coping strategies, related to cognitive impairment, while optimistic emotions can trigger positive coping strategies, reducing the occurrence of cognitive impairment after stroke survival. The biopsychosocial model of cognitive impairment suggests that cognition is not only determined by biological and physical health factors, but psychological and social factors can also affect cognitive health and dementia risk (43). In addition, certain personality traits are also related to cognitive health, such as an outgoing personality being associated with better cognitive function (44). Ryo’s study showed that negative avoidance coping is significantly correlated with significant cognitive decline (45), which is consistent with the results of this study. Another study (46) also suggests that coping strategies partially mediate the relationship between empathy and burnout. Optimism is a positive personality trait that is linked to cognitive function indirectly through its association with coping strategies, which is consistent with our research findings. In addition to encouraging a positive attitude, supporting the development of effective coping skills may also be an important consideration for cognitive health after stroke.

4.7 Clinical implications

This cross-sectional study demonstrates the mediating role of coping style in the relationship between optimism and cognitive impairment in stroke patients. From a clinical perspective, the identified mediating role of coping style suggests that psychological interventions for post-stroke patients could extend beyond general support to specifically target enhancing optimistic thinking and promoting positive coping strategies. Medical staff help patients maintain a positive attitude, and a positive coping style may help identify patients at higher risk of cognitive decline, thereby enabling timely and personalized psychological care. Furthermore, stroke recovery is a long-term process that continues at home. Patient-centered care models, such as early discharge planning and home-based rehabilitation, increasingly emphasize the role of patient self-management and adaptive psychological resources (47). Future interventions could target these modifiable factors to support survivors in the more challenging, less structured home environment. For future clinical research, our study paves the way for developing and testing targeted interventions. It provides a rationale for future randomized controlled trials to examine whether interventions such as optimism training or cognitive behavioral therapy designed to improve coping skills can effectively delay cognitive impairment in stroke survivors.

5 Limitations and prospects

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First and foremost, the cross-sectional design is a major limitation. The data were collected at a single time point, which prevents us from drawing causal conclusions about the relationships between optimism, coping style, and cognitive impairment. While our model was based on theoretical rationale, it is possible that the relationships are bidirectional or that unmeasured confounding variables account for the observed associations. The mediation analysis, therefore, identifies a statistically significant indirect association, not a proven causal pathway.

Second, a significant limitation is the lack of assessment for depression and anxiety. These highly prevalent conditions post-stroke are not only strong correlates of cognitive impairment but are also intricately linked to both dispositional optimism and coping styles. For instance, depression can directly diminish an optimistic outlook, promote avoidant coping, and exacerbate cognitive complaints. Therefore, it is plausible that the observed association between optimism and cognitive impairment, partially mediated by coping style, could be confounded by underlying depressive or anxious symptomatology acting as a common cause. While our model is grounded in theory, the absence of these critical covariates means we cannot rule out the possibility that they account for a portion of the shared variance among our study variables. Future studies must prioritize their inclusion as covariates or competing mediators to isolate the unique contribution of the optimism-coping pathway.

Future research should focus on two key areas. First, a prospective cohort study should be designed to assess optimism and coping strategies during acute hospitalization, with repeated evaluations of cognitive function at 3, 6, and 12 months after stroke. Second, key covariates such as depression and anxiety should be measured to distinguish their effects from those of the hypothesized optimism and coping styles.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not publicly available because they contain sensitive information, including data that could compromise patient privacy. Requests for access should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Shenyang Medical College. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

PG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LL: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JS: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Validation. WW: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Methodology, Software, Project administration, Validation. LZ: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Software, Funding acquisition, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The 2022 Annual Project of Liaoning Province’s Education Science “14th Five Year Plan” (JG22DB664).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Li Zhao for her guidance on the research plan, to every doctor and nurse who has provided us with assistance, and especially to all participants in this trial.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Zhang Q Zhang K Li M Gu J Li X Li M et al . Validity and reliability of the mandarin version of the treatment burden questionnaire among stroke patients in mainland China. Fam Pract. (2021) 38:537–42. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmab004.6146009,

2.

Zhang Q Fu Y Lu Y Zhang Y Huang Q Yang Y et al . Impact of virtual reality-based therapies on cognition and mental health of stroke patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e31007. doi: 10.2196/31007,

3.

Ignacio KHD Muir RT Diestro JDB Singh N Yu MHLL Omari OE et al . Prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms after stroke in young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2024) 33:107732. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2024.107732,

4.

van Nimwegen D Hjelle EG Bragstad LK Kirkevold M Sveen U Hafsteinsdóttir T et al . Interventions for improving psychosocial well-being after stroke: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. (2023) 142:104492. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2023.104492,

5.

Einstad MS Saltvedt I Lydersen S Ursin MH Munthe-Kaas R Ihle-Hansen H et al . Associations between post-stroke motor and cognitive function: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. (2021) 21:103. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02055-7,

6.

Almhdawi KA Alazrai A Kanaan S Shyyab AA Oteir AO Mansour ZM et al . Post-stroke depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms and their associated factors: a cross-sectional study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. (2021) 31:1091–104. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2020.1760893,

7.

Engel GL . The biopsychosocial model and the education of health professionals. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (1978) 1:156–65. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(79)90062-8,

8.

Frank D Gruenbaum BF Zlotnik A Semyonov M Frenkel A Boyko M . Pathophysiology and current drug treatments for post-stroke depression: a review. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:15114. doi: 10.3390/ijms232315114,

9.

Liu LL Xiang XH He JJ . Psychological stress, coping strategies, and self-care of GDM patients the correlation of abilities. Chin J Fam Plann. (2024) 32:1176–9.

10.

Andreotti C Root JC Ahles TA McEwen BS Compas BE . Cancer, coping, and cognition: a model for the role of stress reactivity in cancer-related cognitive decline. Psychooncology. (2015) 24:617–23. doi: 10.1002/pon.3683,

11.

Clement-Carbonell V Ferrer-Cascales R Ruiz-Robledillo N Rubio-Aparicio M Portilla-Tamarit I Cabañero-Martínez MJ . Differences in autonomy and health-related quality of life between resilient and non-resilient individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:2317. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16132317,

12.

Jiang TS Liu Y Zhu XY Wang YZN Liu SK . Meta analysis of factors influencing the conversion of mild cognitive impairment patients to Alzheimer’s disease. Psychol Monthly. (2023) 18:15–8.

13.

Sachs BC Gaussoin SA Brenes GA Casanova R Chlebowski RT Chen JC et al . The relationship between optimism, MCI, and dementia among postmenopausal women. Aging Ment Health. (2023) 27:1208–16. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2022.2084710,

14.

Gawronski KA Kim ES Langa KM Gawronski KAB Kubzansky LD . Dispositional optimism and incidence of cognitive impairment in older adults. Psychosom Med. (2016) 78:819–28. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000345,

15.

Conversano C Rotondo A Lensi E Della Vista O Arpone F Reda MA . Optimism and its impact on mental and physical well-being. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. (2010) 6:25–9. doi: 10.2174/1745017901006010025,

16.

Costa-Requena G Cantarell-Aixendri MC Parramon-Puig G Serón-Micas D . Dispositional optimism and coping strategies in patients with a kidney transplant. Nefrologia. (2014) 34:605–10. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2014.Jun.11881,

17.

Posis AIB Yarish NM Ryu RH Tindle HA Michael YL Wactawski-Wende J et al . Psychometric analysis of the modified differential emotions scale and the six-item life orientation test-revised in a cohort of older women from the women's health initiative. J Womens Health (Larchmt). (2023) 32:992–1005. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2023.0056,

18.

Cao H Zhang R Li L Yang L . Coping style and resilience mediate the effect of childhood maltreatment on mental health symptomology. Children (Basel). (2022) 9:1118. doi: 10.3390/children9081118,

19.

Wang J Tu S Cui J Yang R Jiang Y Zhao L . Exploring the dynamics of stroke survivors' care dependency, fatigue, and coping strategy in their caregivers: a structural equation modeling analysis. Front Public Health. (2025) 13:1528109. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1528109,

20.

Galvin JE Roe CM Xiong C Morris JC . Validity and reliability of the AD8 informant interview in dementia. Neurology. (2006) 67:1942–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247042.15547,

21.

Thaipisuttikul P Nakawiro D Kuladee S Chittaropas P Sukying C . Development and validation of the ascertain dementia 8 (AD8) Thai version. Psychogeriatrics. (2022) 22:795–801. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12884,

22.

Yang CH Lin YT Hsieh MH Hwang TJ . A re-evaluation study and literature review on AD8 as a screening tool for dementia. PLoS One. (2025) 20:e0321570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0321570,

23.

Chin R Ng A Narasimhalu K Kandiah N . Utility of the AD8 as a self-rating tool for cognitive impairment in an Asian population. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. (2013) 28:284–8. doi: 10.1177/1533317513481090,

24.

Xie Y Gao Y Jia J Wang X Wang Z Xie H . Utility of AD8 for cognitive impairment in a Chinese physical examination population: a preliminary study. ScientificWorldJournal. (2014) 2014:804871. doi: 10.1155/2014/804871,

25.

Şengüldür E Demir MC . Evaluation of the association of serum uric acid levels and stroke in emergency department patients. Düzce Tıp Fakültesi Dergisi. (2024) 26:112–7. doi: 10.18678/dtfd.1457023

26.

Zhu Y Xu H Ding D Liu Y Guo L Zauszniewski JA et al . Resourcefulness as a mediator in the relationship between self-perceived burden and depression among the young and middle-aged stroke patients: a cross-sectional study. Heliyon. (2023) 9:e18908. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18908,

27.

Chen Y Du H Song M Liu T Ge P Xu Y et al . Relationship between fear of falling and fall risk among older patients with stroke: a structural equation modeling. BMC Geriatr. (2023) 23:647. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-04298-y,

28.

Li T Wang H Yang Y Galvin JE Morris JC Yu X . Preliminary study on the reliability and validity of the Chinese version of AD8. Chin J Intern Med. (2012) 51:777–80. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2012.10.011

29.

Sun JH Tan L Yu JT . Post-stroke cognitive impairment: epidemiology, mechanisms and management. Chin J Intern Med. (2012) 51:777–80. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2012.10.011,

30.

Filler J Georgakis MK Dichgans M . Risk factors for cognitive impairment and dementia after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev. (2024) 5:e31–44. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(23)00217-9,

31.

de Graaf JA Schepers VPM Nijsse B van Heugten CM Post MWM Visser-Meily JMA . The influence of psychological factors and mood on the course of participation up to four years after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. (2022) 44:1855–62. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2020.1808089,

32.

Slade K Plack CJ Nuttall HE . The effects of age-related hearing loss on the brain and cognitive function. Trends Neurosci. (2020) 43:810–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.07.005,

33.

Beeri MS Tirosh A Lin HM Golan S Boccara E Sano M et al . Stability in BMI over time is associated with a better cognitive trajectory in older adults. Alzheimers Dement. (2022) 18:2131–9. doi: 10.1002/alz.12525,

34.

Liu M Wang XY Duan Y Gao XF . Study on depression and its influencing factors among the elderly in rural areas of Sichuan Province. Mod Prev Med. (2024) 51:2892–2897+2910.

35.

Mani A Mullainathan S Shafir E Zhao J . Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science. (2013) 341:976–980. doi: 10.1126/science.1238041

36.

Al-Ozairi A Irshad M Alsaraf H AlKandari J Al-Ozairi E Gray SR . Association of physical activity and sleep metrics with depression in people with type 1 diabetes. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2024) 17:2717–25. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S459097,

37.

Jones SA Lueras JM Nagel BJ . Effects of binge drinking on the developing brain. Alcohol Res. (2018) 39:87–96. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v39.1.11,

38.

Wang K Liu Q Mo S Zheng K Li X Li J et al . A decision tree model to help treatment decision-making for severe spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Int J Surg. (2024) 110:788–98. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000852,

39.

Wang Z Hou J Shi Y Tan Q Peng L Deng Z et al . Influence of lifestyles on mild cognitive impairment: a decision tree model study. Clin Interv Aging. (2020) 15:2009–17. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S265839,

40.

Oh J Chopik WJ Kim ES . The association between actor/partner optimism and cognitive functioning among older couples. J Pers. (2020) 88:822–32. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12529,

41.

Bhattacharyya KK Molinari V . Impact of optimism on cognitive performance of people living in rural area: findings from a 20-year study in US adults. Gerontol Geriatr Med. (2024) 10:23337214241239147. doi: 10.1177/23337214241239147,

42.

Palamarchuk IS Vaillancourt T . Mental resilience and coping with stress: a comprehensive, multi-level model of cognitive processing, decision making, and behavior. Front Behav Neurosci. (2021) 15:719674. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2021.719674,

43.

Spector A Orrell M . Using a biopsychosocial model of dementia as a tool to guide clinical practice. Int Psychogeriatr. (2010) 22:957–65. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210000840,

44.

Graham EK James BD Jackson KL Willroth EC Luo J Beam CR et al . A coordinated analysis of the associations among personality traits, cognitive decline, and dementia in older adulthood. J Res Pers. (2021) 92:104100. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104100,

45.

Shikimoto R Nozaki S Sawada N Shimizu Y Svensson T Nakagawa A et al . Coping in mid- to late life and risk of mild cognitive impairment subtypes and dementia: a JPHC Saku mental health study. J Alzheimer's Dis. (2022) 90:1085–101. doi: 10.3233/JAD-215712,

46.

Cheng L Yang J Li M Wang W . Mediating effect of coping style between empathy and burnout among Chinese nurses working in medical and surgical wards. Nurs Open. (2020) 7:1936–44. doi: 10.1002/nop2.584,

47.

Şengüldür E Selki K . Bedridden patients at emergency department: can we treat them at home?Online Türk Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi. (2025) 10:69–75. doi: 10.26453/otjhs.1610351

Summary

Keywords

cognitive impairment, optimism, coping style, stroke, structural equation modeling

Citation

Gu P, Liu L, Su J, Wang W and Zhao L (2026) The mediating role of coping style in the relationship between optimism and cognitive impairment in patients with stroke. Front. Neurol. 16:1674025. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1674025

Received

16 August 2025

Revised

04 December 2025

Accepted

05 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Lorenzo Pia, University of Turin, Italy

Reviewed by

Erdinç Şengüldür, Duzce Universitesi Tip Fakultesi, Türkiye

Xiaoxuan Wang, Zhengzhou University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Gu, Liu, Su, Wang and Zhao.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Weifu Wang, 13700036999@163.com; Li Zhao, halljolly@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.