Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the effects of rehabilitation-initiation timing (RIT) and rehabilitation-hospitalization frequency (RHF) on activities of daily living (ADL) evaluated at 6 months post-stroke.

Design:

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting:

Convalescent rehabilitation wards in urban and suburban areas of Xiangyang, China.

Participants:

A total of 275 patients with ADL impairment following acute or subacute stroke who received inpatient comprehensive rehabilitation between 2021 and 2024.

Interventions:

Participants underwent inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation—including physical therapy, occupational therapy, and individualized functional exercises—during each hospitalization, with each inpatient rehabilitation episode lasting for 3 weeks. The main exposures were the timing of rehabilitation initiation and the total number of inpatient rehabilitation episodes within the first 6 months post-stroke.

Main outcome measures:

The primary outcome was the change in ADL, assessed by the Barthel Index (BI), from baseline to the 6-month post-stroke follow-up.

Results:

At the 6-month (180-day) follow-up, the mean BI score increased by 12.59 points compared to baseline (95% CI, 5.53–19.65; p < 0.001). Compared to those who started rehabilitation at 61–90 days post-stroke, patients who initiated rehabilitation earlier—at 1–14, 15–30, and 31–60 days—showed greater BI improvements at 6 months, with mean differences of 15.48 (95% CI, 4.90–26.06; p = 0.004), 13.18 (95% CI, 3.85–22.51, p = 0.005), and 8.63 (95% CI, 0.40–16.86, p = 0.04) points, respectively. Among patients who started rehabilitation at 1–14 and 15–30 days, each additional systematic inpatient rehabilitation was associated with a further mean BI increase of 2.24 (95% CI, 0.98–5.46, p = 0.20) and 2.10 (95% CI, 0.87–5.07, p = 0.21) points, respectively, although these differences did not reach statistical significance. Subgroup analysis showed that early rehabilitation significantly improved BI in patients aged ≥65 and those with hemorrhagic stroke. Moreover, higher hospitalization frequency benefited patients with higher education and those with hemorrhagic stroke.

Conclusion:

Earlier initiation and greater frequency of inpatient rehabilitation were independently associated with better ADL outcomes at the 6-month mark in rural Chinese stroke survivors. Importantly, the benefit of each additional rehabilitation admission was amplified when therapy began within the first month post-stroke and diminished when initiation was delayed beyond two months, especially among patients with hemorrhagic stroke, aged ≥65 years, women, and those with higher educational attainment.

Introduction

The acute and subacute phases, corresponding to the first few months post-stroke, represent a critical window for neurological recovery. During this period, patients exhibit heightened responsiveness to therapeutic interventions, making the analysis of rehabilitation initiation timing an essential factor for maximizing functional outcomes (1). Following a stroke, survivors frequently develop profound functional deficits and diminished activities of daily living (ADL) (2). Declining ADL in turn reduces quality of life, elevates hospitalisation and fall risk, and increases caregiver burden (3, 4). Rural residents receive poorer stroke care, and technological advances may widen this disparity (5). Achieving equitable rehabilitation—especially for rural populations—therefore remains challenging and is associated with delayed intervention and worse outcomes.

Rehabilitation is the most effective strategy for restoring ADL (6). Its benefit depends on therapy intensity,duration,and, critically, the interval between stroke onset and rehabilitation initiation (7–9). Although one study found that rural patients were less likely to receive a complete stroke-care bundle without showing worse outcomes (10), the influence of rehabilitation timing on 6-month ADL in rural settings is unclear.

Evidence supports beginning rehabilitation within 6 months after stroke (11). Among sub-acute patients, > 40 sessions yield greater ADL gains than ≤ 40 sessions (12). However, in China, community-based rehabilitation networks remain underdeveloped, with limited standardized service models, incomplete rural and community rehabilitation infrastructure, and insufficient insurance coverage for many rehabilitation programs (13, 14). As a result, stroke survivors in rural areas often require structured inpatient rehabilitation. However, due to health insurance policies that typically restrict each inpatient rehabilitation cycle to approximately three weeks, many patients must be readmitted multiple times during the crucial six-month recovery period in order to receive adequate therapy. These systemic barriers disrupt continuity of care and limit access to sustained, high-quality rehabilitation, and their impact on long-term functional recovery—particularly among rural patients—remains unclear.

Clinical and sociodemographic factors—including stroke subtype, age, sex, and education—also shape recovery trajectories (15–22). Few studies have evaluated rehabilitation initiation timing (RIT) and rehabilitation-hospitalisation frequency (RHF) together or explored their interaction with patient characteristics. This study therefore assessed their independent and combined effects on 6-month ADL, measured by the Barthel Index (BI), with subgroup analyses by stroke subtype, age, sex, and education.

Methods

Ethics approval

The institutional ethics committee approved the study (No. 2024–098). All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Reporting follows STROBE guidelines.

Study design

A retrospective cohort study was conducted at rehabilitation hospitals in urban and suburban Xiangyang, China, serving predominantly rural populations. The study assessed whether rehabilitation initiation timing and rehabilitation-hospitalization frequency within 6 months after stroke predicted change in BI score. All data collectors completed a uniform training programme. Two researchers entered the data independently, and a third auditor randomly reviewed 5% of records; discrepancies were resolved against the source documents.

Participants

All patients admitted for stroke between 1 January 2021 and 31 December 2024 were screened. Eligibility required (i)a first-ever ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke, with lesion localization documented, verified by CT or MRI; (ii) initiation of the index rehabilitation programme within 1–90 days of stroke onset; (iii) age ≥ 18 years; (iv) first rehabilitation delivered at a participating hospital; (v) a baseline Barthel Index (BI) < 100; and (vi) sufficient cognitive and physical capacity to comply with assessment and therapy. Patients without a 180-day BI follow-up were excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Study flowchart showing selection of participants.

Exposure definitions

Rehabilitation-initiation timing

RIT was defined as the number of calendar days from stroke onset to the first structured inpatient rehabilitation session—physiotherapy, occupational therapy, or speech-language therapy—delivered on a dedicated stroke-rehabilitation ward. For analysis, RIT was categorized a priori into four intervals: 1–14, 15–30, 31–60, and 61–90 days post-stroke.

Rehabilitation-hospitalization frequency

RHF was defined as the number of discrete inpatient admissions for structured stroke rehabilitation within six months after stroke onset, once the patient had reached clinical stability. Each qualifying admission includes a standardized rehabilitation assessment, stroke-specific medical management (e.g., antiplatelet or lipid-lowering therapy), and an individually tailored multimodal programme that may combine physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech- and swallowing therapy, respiratory training, neuromuscular or low-frequency electrical stimulation, manual techniques such as joint mobilization or massage, acupuncture, short-wave diathermy, and task-oriented exercises as required. Readmissions undertaken solely for acute medical complications (e.g., pneumonia, heart failure) and all outpatient, day-hospital, or home-based sessions are excluded.

RHF varied significantly across the four rehabilitation-initiation groups (p < 0.001), whereas the mean length of stay per rehabilitation admission remained uniform (p = 0.26). Because single-admission duration was essentially constant, a higher RHF reflects a greater cumulative exposure to standardized rehabilitation that is independent of inpatient stay length. RHF was therefore selected as the principal exposure variable for subsequent dose–response analyses. Detailed values are reported in Supplementary Table S1.

Outcomes

ADL were measured with the BI, which evaluates performance on 10 functional items; higher scores indicate greater independence. The primary outcome was the change in BI from baseline to 180 days after rehabilitation initiation.

Covariates

Prespecified covariates were stroke subtype (ischaemic vs. haemorrhagic), sex, age, educational attainment (primary school or less vs. above primary), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, coronary heart disease, prior stroke-related surgery, venous thromboembolism risk score, and current smoking or alcohol use (yes vs. no).

Statistical analysis

All computations were performed with R (version 4.3.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range) where appropriate, whereas categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages. Baseline characteristics were compared with χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical data and with one-way analysis of variance or Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous data, according to distributional assumptions. Two-sided p values < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. The impact of rehabilitation-initiation timing and RHF on 6-month change in BI was examined with linear mixed-effects models that included a random intercept for each patient. RIT was modelled as a four-level factor (1–14, 15–30, 31–60, and 61–90 days after stroke onset), while RHF—defined as the number of qualifying rehabilitation admissions within the first six months—was entered as a continuous term. Models were adjusted a priori for the demographic and clinical covariates listed above. Pre-specified subgroup and sensitivity analyses are described in the Supplementary material.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 presents baseline data for the 275 participants, stratified by RIT. Baseline BI scores were comparable across timing groups (p = 0.52), and no significant differences emerged in sex, age, body-mass index, educational level, lifestyle behaviours, or major comorbidities (all p > 0.05). By contrast, stroke subtype and the prevalence of prior stroke-related surgery differed significantly among the four RIT groups (p = 0.01; p = 0.003).

Table 1

| Characteristics | Group 1 (1–14) days |

Group 2 (15–30) days |

Group 3 (31–60) days |

Group 4 (61–90) days |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke type, n (%) | 0.01 | ||||

| Ischemic stroke | 37 (13.45%) | 39 (14.18%) | 33 (12.00%) | 14 (5.09%) | |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 10 (3.64%) | 53 (19.27%) | 48 (17.45%) | 27 (9.82%) | |

| Other | 0 (0.00%) | 5 (1.82%) | 6 (2.18%) | 3 (1.09%) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.45 | ||||

| Male | 35(12.73) | 70(25.45) | 55(20.00) | 29(10.55) | |

| Female | 12(4.36) | 27(9.82) | 32(11.64%) | 15(5.45%) | |

| Age, Mean ± SD | 63.13 ± 5.11 | 61.06 ± 3.00 | 55.70 ± 2.80 | 63.25 ± 5.44 | 0.85 |

| Educational level, n (%) | 0.70 | ||||

| Primary | 8(2.91%) | 22(8.00%) | 19(6.91%) | 12(4.36%) | |

| Above primary | 39(14.18%) | 75(27.27%) | 68(24.73%) | 32(11.64%) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.92 | ||||

| No | 30(10.91%) | 66(24.00%) | 59(21.45%) | 31(11.27%) | |

| Yes | 17(6.18%) | 31(11.27%) | 28(10.18%) | 13(4.73%) | |

| Drinking status, n (%) | 0.56 | ||||

| No | 32(11.64%) | 61(22.18%) | 62(22.55%) | 32(11.64%) | |

| Yes | 15(5.45%) | 36(13.09%) | 25(9.09%) | 12(4.36%) | |

| Surgical history, n (%) | 0.003 | ||||

| No | 29(10.55%) | 37(13.45%) | 50(18.18%) | 15(5.45%) | |

| Yes | 18(6.55%) | 60(21.82%) | 37(13.45%) | 29(10.55%) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0.5 | ||||

| No | 7 (2.55%) | 18 (6.55%) | 21 (7.64%) | 11 (4.00%) | |

| Yes | 40 (14.55%) | 79 (28.73%) | 66 (24.00%) | 33 (12.00%) | |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 0.15 | ||||

| No | 44 (16.00%) | 86 (31.27%) | 83 (30.18%) | 43 (15.64%) | |

| Yes | 3 (1.09%) | 11 (4.00%) | 4 (1.45%) | 1 (0.36%) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 0.31 | ||||

| No | 31 (11.27%) | 77 (28.00%) | 67 (24.36%) | 35 (12.73%) | |

| Yes | 16 (5.82%) | 20 (7.27%) | 20 (7.27%) | 9 (3.27%) | |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 0.86 | ||||

| No | 40 (14.55%) | 86 (31.27%) | 76 (27.64%) | 37 (13.45%) | |

| Yes | 7 (2.55%) | 11 (4.00%) | 11 (4.00%) | 7 (2.55%) | |

| VTE scores, Mean ± SD | 1.38 ± 0.32 | 2.50 ± 0.52 | 2.26 ± 0.46 | 2.00 ± 0.87 | 0.43 |

| BI scores at baseline, Mean ± SD | 35.63 ± 13.08 | 39.81 ± 7.23 | 30.96 ± 3.56 | 33.13 ± 8.34 | 0.52 |

| BI scores at 180-day follow-up, Mean ± SD | 65.02 ± 4.10 | 55.69 ± 2.37 | 52.82 ± 2.56 | 47.04 ± 3.75 | <0.01 |

Demographics and clinical characteristics.

VTE, venous thromboembolism; BI, Barthel Index.

Impact of RIT on ADL recovery

After multivariable adjustment, baseline BI scores did not differ between any early-initiation group (RIT 1–14 d, 15–30 d, or 31–60 d) and the late-initiation reference group (61–90 d; all p > 0.05; Table 2). By contrast, earlier RIT was associated with significantly greater functional gains at 180 days. Initiating rehabilitation within 1–14 days produced the largest benefit (β = 15.48, 95% CI 4.90–26.06; p = 0.004), followed by 15–30 days (β = 13.18, 95% CI 3.85–22.51; p = 0.005) and 31–60 days (β = 8.63, 95% CI 0.40–16.86; p = 0.040) compared with the reference group. The overall time effect indicated a mean improvement of 12.59 BI points across the cohort during follow-up (95% CI 5.53–19.65; p < 0.001).

Table 2

| Group Comparison | Standardized β-coefficient | SE | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| Group 1 vs. group 4 | −0.50 | 4.28 | −8.89, 7.89 | 0.91 |

| Group 2 vs. group 4 | −2.89 | 3.87 | −10.48,4.70 | 0.50 |

| Group 3 vs. group 4 | −1.17 | 3.07 | −7.19, 4.85 | 0.70 |

| 180-day follow-up | ||||

| Group 1 vs. group 4 | 15.48 | 5.40 | 4.90, 26.06 | 0.004 |

| Group 2 vs. group 4 | 13.18 | 4.76 | 3.85, 22.51 | 0.005 |

| Group 3 vs. group 4 | 8.63 | 4.20 | 0.40, 16.86 | 0.04 |

| Time effect | 12.59 | 3.60 | 5.53, 19.65 | <0.001 |

Association between RIT and 6-month change in BI.

*A multiple-exposure model adjusted for age, sex, educational level, clinical history variables, and lifestyle factors, with mutual adjustment for the initial rehabilitation initiate timing group and time effects in stroke patients.

Interaction between RHF and RIT on ADL recovery

The linear mixed-effects model revealed a positive dose–response between RHF and 6-month BI change: each additional qualifying admission was associated with a 1.47-point increment in BI (β = 1.47, 95% CI 0.27–2.67; p = 0.010; Table 3). When stratified by RIT, the magnitude of this effect varied: relative to the late-initiation reference group (61–90 days), each extra admission in the 1-14-day and 15-30-day cohorts conferred larger gains of 2.24 and 2.10 BI points, respectively, whereas the 31-60-day cohort showed a modest 0.49-point increase.

Table 3

| Group comparison | Standardized β-coefficient | SE | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHF (per admission) | 1.47 | 0.61 | 0.27, 2.67 | 0.01 |

| Group comparison | ||||

| Group 4 ref. (reference) | - | - | - | - |

| Group1 vs. group 4 | 2.24 | 1.64 | −0.98, 5.46 | 0.20 |

| Group 2 vs. group 4 | 2.10 | 1.51 | −0.87, 5.07 | 0.21 |

| Group 3 vs. group 4 | 0.49 | 1.43 | −2.32, 3.30 | 0.85 |

Interaction between RHF and RIT on 6-month BI change.

*A multiple-exposure model adjusted for age, sex, educational level, time effects, clinical history variables, and lifestyle factors, with mutual adjustment for both the RIT and RHF. RIT, rehabilitation initiation timing; RHF, rehabilitation-hospitalisation frequency.

Subgroup analyses

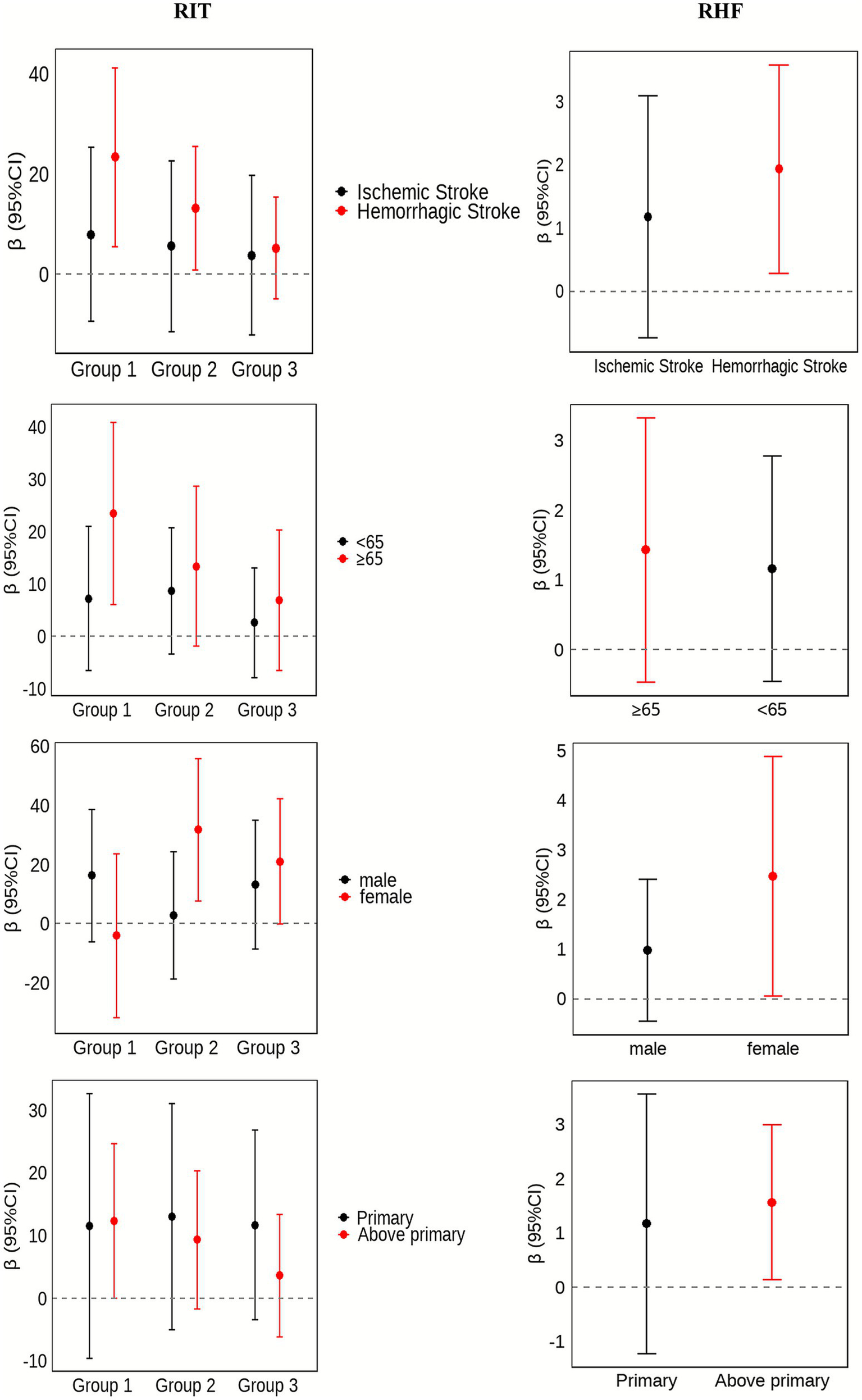

To investigate whether the effects of RIT and RHF differed across key patient populations, particularly given the known differences in recovery trajectories between ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, pre-specified subgroup analyses were conducted. Figure 2 summarises the subgroup findings. Early RIT was associated with significantly larger 6-month BI gains in patients aged ≥ 65 years (β = 20.97, 95% CI 3.62–38.31; p = 0.02) and in those with haemorrhagic stroke (β = 22.05, 95% CI 4.59–39.51; p = 0.01); no benefit was observed in the remaining strata. For RHF, each additional rehabilitation admission yielded significant improvements in participants with higher educational attainment (β = 1.59, 95% CI 0.18–3.01; p = 0.03) and in the hemorrhagic stroke subgroup (β = 1.89, 95% CI 0.28–3.49; p = 0.02). No significant RHF related gains were detected in the other subgroups. Full numerical details are provided in Supplementary Tables S2, S3.

Figure 2

Sub group effects of RIT and RHF on 6-month change in BI, stratified by stroke subtype, sex, educational attainment, and age. RIT, rehabilitation initiation timing; RHF, rehabilitation-hospitalisation frequency.

Sensitivity analyses

The sensitivity analysis confirmed the primary findings, the direction and magnitude of the effects were essentially unchanged. Earlier RIT and higher RHF each remained independently associated with greater 6-month gains in BI, underscoring the robustness of the results (Supplementary Tables S4, S5).

Discussion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first real-world cohort to quantify both RIT and RHF as drivers of long-term ADL after stroke in China. The results show that starting structured rehabilitation earlier—and repeating it more often—independently predicts larger 6-month gains in BI. Subgroup analyses highlight clinically meaningful heterogeneity by stroke subtype, age, sex, and educational attainment. Notably, many patients in the study cohort, particularly from rural areas, began rehabilitation more than 30 days post-stroke, a delay likely driven by limited health literacy and restricted access to specialized care. Collectively, these findings offer actionable evidence for refining post-stroke rehabilitation policies and tailoring intervention schedules to maximize functional recovery.

This study demonstrated that initiating rehabilitation within 1–90 days post-stroke improves ADL at 6 months, with the largest gains when therapy begins in the first 14 days. This underscores how critical prompt rehabilitation is for functional recovery. Supporting these findings, a nationwide Japanese cohort showed that rehabilitation initiated within 3 days of hospitalization significantly improved ADL at discharge (8), and other retrospective work has likewise identified early therapy and longer inpatient exposure as key predictors of ADL improvement (9). Mechanistically, early rehabilitation coincides with the peak of post-ischaemic neuroplasticity, fostering network re-organization, synaptogenesis, and restoration of cortical excitability (16–18). These processes are most active soon after stroke, explaining the larger ADL observed in this study. Patients who start therapy within 1–30 days may still be in a phase of cerebral-oedema resolution and active neuro-regeneration (19, 20); as oedema subsides and neuro-inflammation diminishes, the micro-environment becomes more conducive to repair (21, 22). By contrast, delaying rehabilitation (RIT 31–90 days) risks missing this plasticity window. Early therapy also curbs secondary complications—deep-vein thrombosis, infections, and secondary brain injury —which further supports recovery (23, 24).

The analysis also confirmed the positive effect of RHF on ADL recovery. After adjustment for all demographic and clinical covariates, each additional rehabilitation admission was associated with a mean gain of 1.47 BI points. When the RHF effect was stratified by rehabilitation-initiation timing (RIT), the greatest marginal benefit was seen in the earliest-initiation groups: relative to the 61–90-day reference group, every extra admission raised the 6-month BI by 2.24 points when rehabilitation began within 1–14 days and by 2.10 points when it began within 15–30 days, whereas the corresponding increase was 0.49 points for initiation at 31–60 days. Although some comparisons did not reach statistical significance—likely a consequence of limited sample size—the directional consistency and effect sizes are clinically meaningful for stroke rehabilitation (25).

These findings reinforce earlier work emphasising the central role of rehabilitation “dose” in post-stroke recovery. A Korean cohort study, for example, showed that > 40 rehabilitation sessions within six months improved ADL and reduced all-cause mortality (12), while a meta-analysis by Kwakkel et al. (26) reported significant gains in ADL and motor function for each additional hour of therapy. Repeated admissions likely provide sustained sensorimotor stimulation that facilitates neural remodeling and synaptic regeneration (27). In China, insurance regulations restrict prolonged inpatient rehabilitation, resulting in multiple short-cycle admissions that deliver intensive, therapist-guided interventions. Consequently, RHF approximates the cumulative volume of rehabilitation actually received. For rural patients with limited access to continuous outpatient services, increasing the number of such short admissions may partially offset delays in initiation and help close the urban–rural gap in post-stroke care.

Subgroup analyses uncovered clinically meaningful heterogeneity. Early RIT yielded the largest BI gains in patients with haemorrhagic stroke and those aged ≥ 65 years, whereas the effect of RHF was most pronounced among patients with hemorrhagic stroke and higher educational attainment, with a borderline trend observed in women. The heightened responsiveness of hemorrhagic stroke patients aligns with Korean registry data showing reduced mortality only in this subgroup (12). likely reflecting reversible mass-effect resolution and preserved neuroplastic potential likely reflecting reversible mass-effect resolution and preserved neuroplastic potential (28, 29). Older adults experienced greater functional improvements, perhaps owing to lower baseline independence and a larger absolute capacity for recovery, as suggested by neuroimaging studies (30, 31). Women achieved more pronounced BI increases, potentially because of higher baseline frailty and sociocultural factors influencing rehabilitation engagement (32, 33). Finally, higher education was associated with better outcomes—likely through improved health literacy and adherence—consistent with studies on stroke awareness and participation (34, 35). Conversely, limited education and health literacy in rural populations may impede effective rehabilitation uptake, underscoring the need for targeted stroke-education programmes and community-based support.

The strengths of this study include its longitudinal design and the first quantitative analysis of both RIT and RHF on ADL recovery in stroke patients. By examining their interaction, the study’s findings highlight the importance of early and frequent inpatient rehabilitation within the first six months post-stroke and provide new clinical evidence for optimizing rehabilitation strategies. Importantly, RHF is especially relevant in the Chinese context, where insurance constraints limit prolonged stays and rural patients have scarce outpatient options—multiple short-cycle admissions therefore offer a practical means to deliver cumulative therapy “dose.” The use of linear mixed-effects models ensured rigorous control of confounders, supporting the reliability of the results, and subgroup analyses revealed heterogeneity in response, underscoring the need for personalized rehabilitation plans tailored to patient characteristics.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this study primarily assessed the relationship between RIT, RHF, and ADL improvement, without further differentiating among specific types of rehabilitation interventions (e.g., physical therapy, occupational therapy). Second, the model used in this study did not account for other critical real-world factors that can disrupt the rehabilitation process. For instance, progress can be delayed or interrupted by medical complications—some of which may be unrelated to the primary stroke pathology (36). Moreover, variables such as the total number of rehabilitation days lost due to illness or other reasons, and the patient’s psychological state (e.g., depression, anxiety, or motivational deficits), are known to significantly influence functional outcomes. Although this study did not use specific scales to assess these factors, their impact on recovery and autonomy is undeniable and represents an important area for future, more granular research. Third, the study’s findings require validation in larger-scale studies.

Conclusion

Earlier RIT and higher RHF are independently linked to greater six-month ADL improvements after stroke, with the strongest effects observed in patients starting rehabilitation within 30 days and undergoing more frequent admissions. These findings are especially relevant in rural China, where limited community rehabilitation and short insurance-covered stays necessitate repeated inpatient rehabilitation. By quantifying these effects, this study highlights the importance of timely, sustained rehabilitation and underscores the need to strengthen coverage and expand community services to optimize functional recovery.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Xiangyang Central Hospital (Approval number: 2024-098). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JL: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Methodology. LZ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. CJ: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation. XJ: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision. CZ: Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. FW: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. TQ: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. QS: Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Project of Preventive Medicine Association of Hubei Province (No. 2025SWGKY125 and No.2025SWGKY126), Project of Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Hubei Province (No. ZY2025L066), Xiangyang Central Hospital (No. 2025YJ27B) and Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province of China (No. C2023058).

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the participants involved in this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2025.1706724/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

ADL, Activities of daily living; BI, Modified Barthel Index; VTE, Venous thromboembolism.

References

1.

Chiaramonte R D'Amico S Caramma S Grasso G Pirrone S Ronsisvalle MG et al . The effectiveness of goal-oriented dual task proprioceptive training in subacute stroke: a retrospective observational study. Ann Rehabil Med. (2024) 48:31–41. doi: 10.5535/arm.23086,

2.

Zhang Q Gao X Huang J Xie Q Zhang Y . Association of pre-stroke frailty and health-related factors with post-stroke functional independence among community-dwelling Chinese older adults. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2023) 32:107130. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2023.107130,

3.

Chou A Beach SR Lutz BJ Rodakowski J Terhorst L Freburger JK . Moderating effects of informal care on the relationship between ADL limitations and adverse outcomes in stroke survivors. Stroke. (2024) 55:1554–61. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.123.045427,

4.

Zhang Q Yan J Long J Wang Y Li D Zhou M et al . Exploring the association between activities of daily living ability and injurious falls in older stroke patients with different activity ranges. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:19731. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-70413-7,

5.

Malliarou M Tsionara C Patsopoulou A Bouletis A Tzenetidis V Papathanasiou I et al . Investigation of factors that affect the quality of life after a stroke. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2023) 1425:437–42. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-31986-0_42,

6.

Stinear CM Lang CE Zeiler S Byblow WD . Advances and challenges in stroke rehabilitation. Lancet Neurol. (2020) 19:348–60. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30415-6,

7.

Sato Y Yoshimura Y Abe T Nagano F Matsumoto A Kokura Y et al . Combination of high energy intake and intensive rehabilitation is associated with the Most Favorable functional recovery in acute stroke patients with sarcopenia. Nutrients. (2022) 14:14. doi: 10.3390/nu14224740,

8.

Tani T Imai S Fushimi K . Rehabilitation of patients with acute ischemic stroke who required assistance before hospitalization contributes to improvement in activities of daily living: a Nationwide database cohort study. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl. (2022) 4:100224. doi: 10.1016/j.arrct.2022.100224,

9.

Zhang Q Zhang Z Huang X Zhou C Xu J . Application of logistic regression and decision tree models in the prediction of activities of daily living in patients with stroke. Neural Plast. (2022) 2022:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2022/9662630,

10.

Turner M Dennis M Barber M Macleod MJ . Impact of rurality and geographical accessibility on stroke care and outcomes. Stroke. (2025) 56:1210–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.124.048251,

11.

Zhao LJ Jiang LH Zhang H Li Y Sun P Liu Y et al . Effects of motor imagery training for lower limb dysfunction in patients with stroke: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. (2023) 102:409–18. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000002107,

12.

Nam JS Heo SJ Kim YW Lee SC Yang SN Yoon SY . Association between frequency of rehabilitation therapy and Long-term mortality after stroke: a Nationwide cohort study. Stroke. (2024) 55:2274–83. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.123.046008,

13.

Tian T Zhu L Fu Q Tan S Cao Y Zhang D et al . Needs for rehabilitation in China: estimates based on the global burden of disease study 1990-2019. Chin Med J. (2025) 138:49–59. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000003245,

14.

Gong J Wang G Wang Y Chen X Chen Y Meng Q et al . Nowcasting and forecasting the care needs of the older population in China: analysis of data from the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Lancet Public Health. (2022) 7:e1005–13. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00203-1,

15.

E Wh Abzhandadze T Rafsten L Sunnerhagen KS . Dependency in activities of daily living during the first year after stroke. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:736684. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.736684

16.

Okabe N Wei X Abumeri F Batac J Hovanesyan M Dai W et al . Parvalbumin interneurons regulate rehabilitation-induced functional recovery after stroke and identify a rehabilitation drug. Nat Commun. (2025) 16:2556. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-57860-0,

17.

Mancuso M Iosa M Abbruzzese L Matano A Coccia M Baudo S et al . The impact of cognitive function deficits and their recovery on functional outcome in subjects affected by ischemic subacute stroke: results from the Italian multicenter longitudinal study CogniReMo. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. (2023) 59:284–93. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.23.07716-X,

18.

Zich C Ward NS Forss N Bestmann S Quinn AJ Karhunen E et al . Post-stroke changes in brain structure and function can both influence acute upper limb function and subsequent recovery. Neuroimage Clin. (2025) 45:103754. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2025.103754,

19.

Moelo C Quillevere A Le Roy L Timsit S . (S)-roscovitine, a CDK inhibitor, decreases cerebral edema and modulates AQP4 and alpha1-syntrophin interaction on a pre-clinical model of acute ischemic stroke. Glia. (2024) 72:322–37. doi: 10.1002/glia.24477,

20.

Han W Song Y Rocha M Shi Y . Ischemic brain edema: emerging cellular mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Neurobiol Dis. (2023) 178:106029. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2023.106029,

21.

Xiao G Lyu M Li Z Cao L Liu X Wang Y et al . Restoration of early deficiency of axonal guidance signaling by guanxinning injection as a novel therapeutic option for acute ischemic stroke. Pharmacol Res. (2021) 165:105460. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105460,

22.

Schleicher RL Vorasayan P McCabe ME Bevers MB Davis TP Griffin JH et al . Analysis of brain edema in RHAPSODY. Int J Stroke. (2024) 19:68–75. doi: 10.1177/17474930231187268

23.

Stein J Bierner SM Dentel S Downs A Kovic M Lutz BJ et al . American Heart Association standards for Postacute stroke rehabilitation care. Stroke. (2025) 56:1650–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.124.048942,

24.

Youkee D Deen GF Baldeh M Conteh ZF Fox-Rushby J Gbessay M et al . Stroke in Sierra Leone: case fatality rate and functional outcome after stroke in Freetown. Int J Stroke. (2023) 18:672–80. doi: 10.1177/17474930231164892,

25.

Hsieh YW Wang CH Wu SC Chen PC Sheu CF Hsieh CL . Establishing the minimal clinically important difference of the Barthel index in stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2007) 21:233–8. doi: 10.1177/1545968306294729,

26.

Kwakkel G van Peppen R Wagenaar RC Wood DS Richards C Ashburn A et al . Effects of augmented exercise therapy time after stroke: a meta-analysis. Stroke. (2004) 35:2529–39. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000143153.76460.7d

27.

Wang H Xiong X Zhang K Wang X Sun C Zhu B et al . Motor network reorganization after motor imagery training in stroke patients with moderate to severe upper limb impairment. CNS Neurosci Ther. (2023) 29:619–32. doi: 10.1111/cns.14065,

28.

Fedor BA Kalisvaart A Ralhan S Kung T MacLaren M Colbourne F . Early, intense rehabilitation fails to improve outcome after intra-striatal Hemorrhage in rats. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2022) 36:788–99. doi: 10.1177/15459683221137342,

29.

Mohammedi K Fauchier L Quignot N Khachatryan A Banon T Kapnang R et al . Incidence of stroke, subsequent clinical outcomes and health care resource utilization in people with type 2 diabetes: a real-world database study in France: "INSIST" study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2024) 23:183. doi: 10.1186/s12933-024-02257-4,

30.

Tani T Kazuya W Onuma R Fushimi K Imai S . Age-related differences in the effectiveness of rehabilitation to improve activities of daily living in patients with stroke: a cross-sectional study. Ann Geriatr Med Res. (2024) 28:257–65. doi: 10.4235/agmr.24.0025,

31.

Chen WC Hsiao MY Wang TG . Prognostic factors of functional outcome in post-acute stroke in the rehabilitation unit. J Formos Med Assoc. (2022) 121:670–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2021.07.009,

32.

Xu M Amarilla VA Cantalapiedra CC Rudd A Wolfe C O'Connell M et al . Stroke outcomes in women: a population-based cohort study. Stroke. (2022) 53:3072–81. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.037829,

33.

Mavridis A Reinholdsson M Sunnerhagen KS Abzhandadze T . Predictors of functional outcome after stroke: sex differences in older individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2024) 72:2100–10. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18963,

34.

Woldetsadik FK Kassa T Bilchut WH Kibret AK Guadie YG Eriku GA . Stroke related knowledge, prevention practices and associated factors among hypertensive patients at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2021. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:839879. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.839879,

35.

Malaeb D Mansour S Barakat M Cherri S Kharaba ZJ Jirjees F et al . Assessment of knowledge and awareness of stroke among Arabic speaking adults: unveiling the current landscape in seven countries through the first international representative study. Front Neurol. (2024) 15:1492756. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1492756

36.

Chiaramonte R D'Amico S Marletta C Grasso G Pirrone S Bonfiglio M . Impact of Clostridium difficile infection on stroke patients in rehabilitation wards. Infect Dis Now. (2023) 53:104685. doi: 10.1016/j.idnow.2023.104685,

Summary

Keywords

stroke, activities of daily living, rehabilitation initiate timing, rehabilitation hospitalization frequency, rural areas

Citation

Liu J, Zhang L, Ju C, Jia X, Zhang C, Wu F, Qin T and Sun Q (2026) Interaction effect of rehabilitation initiation timing and hospitalization frequency on long-term functional outcomes after stroke in rural China: a retrospective cohort study. Front. Neurol. 16:1706724. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1706724

Received

03 October 2025

Revised

13 November 2025

Accepted

09 December 2025

Published

02 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Giorgio Scivoletto, CTO Andrea Alesini, Italy

Reviewed by

Rita Chiaramonte, University of Catania, Italy

Alejandro Vargas, Rush University Medical Center, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Liu, Zhang, Ju, Jia, Zhang, Wu, Qin and Sun.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qianqian Sun, sunqian801830@126.com; Tao Qin, heu_qt@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.