Abstract

Background:

Transradial access (TRA) for cerebral angiography presents challenges such as puncture failures, prolonged procedure times, and difficulties in catheter advancement due to radial artery variations. Utilizing ultrasound guidance, which has demonstrated success in coronary angiography, may improve TRA outcomes. This study aimed to assess the efficacy of ultrasound-guided TRA in cerebral angiography, focusing on success rates, procedure duration, and patient satisfaction.

Methods:

A prospective, non-randomized, controlled trial included 197 patients scheduled for TRA between June 2022 and January 2024. Patients undergoing cerebral angiography through TRA were divided into control and ultrasound group. The ultrasound group underwent preoperative right upper extremity artery ultrasound assessment, with ultrasound-guided puncture for challenging cases. The primary outcomes were procedure completion rate, duration, patient satisfaction, and complication rates. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables to compare these outcomes between the two groups, using a two-tailed significance level of p < 0.05.

Results:

This study included a total of 197 patients: 73 in the control group and 124 in the ultrasound group. TRA was completed in 69 patients (94.5%) in the control group and 117 patients (99.2%) in the ultrasound group. The average operation time was 0.67 ± 0.19 h in the control group and 0.55 ± 0.19 h in the ultrasound group (p < 0.001). Difficult access occurred in 15 patients (21.7%) in the control group compared with 2 patients (1.7%) in the ultrasound group (p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed in either complication rates or patient satisfaction: 8 patients (11.6%) in the control group and 9 (7.7%) in the ultrasound group (p = 0.372) had complications, while 57 patients (82.6%) in the control group and 109 (93.2%) in the ultrasound group reported satisfaction (p = 0.089).

Conclusion:

Ultrasound-guided TRA in cerebral angiography effectively mitigated challenges related to puncture failures and procedure duration, offering the potential to improve outcomes and patient satisfaction in TRA procedures.

1 Introduction

Transfemoral arterial access (TFA) remains a conventional approach for cerebral angiography, favored for its straightforward puncture technique and ease of distal vessel selection. However, TFA is associated with a higher incidence of puncture site complications, primarily due to the deep anatomical location of the femoral artery (1). This depth complicates effective post-procedural compression, increasing hemostasis difficulty and inguinal hematoma risk (reported in about 4.2% of TFA cases) (2). Additionally, prolonged femoral artery compression postoperatively may cause back pain, urinary retention, and deep vein thrombosis, impairing patient satisfaction and recovery. While ultrasound-guided TFA can reduce puncture failure, it has limitations, particularly in patients with obesity or arterial calcification, where pseudoaneurysm and other complications may persist (3). In contrast, the radial artery’s superficial location makes TRA a safer alternative, demonstrating a 60% reduction in access site complications compared to TFA. This approach facilitates easier compression, minimizes major bleeding risk, and reduces the need for prolonged immobilization, leading to shorter hospital stays and lower costs (4–6). Moreover, TRA is associated with shorter fluoroscopy times, higher patient satisfaction, and fewer complications (7–11). For neuro-interventionalists, proficiency in TRA is typically achieved after a learning curve of 30–50 cases, making it feasible for widespread adoption (3, 8, 12, 13). Beyond this threshold, procedure times and success rates consistently rival or exceed those of TFA. Over the past decade, these advantages have made neuro-interventionalists increasingly interested in TRA for both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures (14–18).

Although TRA offers several benefits, it has also faced challenges, including a notable 13.8% incidence of abnormal radial artery dissection. This issue significantly heightens the risk of procedural failure. Additionally, the study found that the risk of surgical failure in cases with radial artery variations is markedly higher, at 14.2%, compared to just 0.9% in those with normal radial arteries (19, 20). If severe tortuosity of the subclavian artery or arterial spasm clasping the contrast catheter is encountered it can greatly increase the difficulty of the procedure (21, 22). The incidence of radial-femoral conversion was reported by Tso et al. (7) to be 1.2% (7/607), which is higher than the incidence of femoral-radial conversion at 0.3% (2/635). Patients requiring conversion from TRA to TFA undergo additional discomfort and increased procedure time and costs. How to improve the success rate of TRA surgery and reduce the risk of surgery are urgent problems to be solved.

Notably, Bernat et al. discovered that using ultrasound guidance for radial artery cannulation in coronary angiography greatly reduced puncture failure decreased the number of attempts, and improved efficiency. The approach also minimizes the risk of radial artery spasms and alleviates pain and swelling (23). This study aimed to determine whether ultrasound assistance could address similar challenges encountered in TRA during cerebral angiography, specifically by improving success rates, shortening procedure times, and enhancing patient satisfaction through preoperative ultrasound evaluation and guidance during difficult punctures. Currently, TRA utilizes the Simmons series of contrast catheters, which are designed based on TFA. This study aimed to gather data on TRA access routes to aid in the development of TRA-specific catheters.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design and population

This prospective, non-randomized, controlled trial was conducted in the neurology unit of a 2,100-bed hospital. It involved sequential data collection from patients undergoing diagnostic cerebral angiography via TRA from June 2022 to January 2024. All patients were divided into two cohorts based on their personal preference for pre-procedural assessment: a control group and an ultrasound group. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) individuals aged 18–90 years; (2) patients needed diagnostic TRA for cerebral angiography. Exclusion criteria: (1) comorbid major psychiatric or systemic illnesses; (2) a negative Allen test result; (3) a blood pressure discrepancy of more than 20 mmHg between the upper extremities; (4) with a history of iodine allergy. Informed consent form had been obtained from all participants, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Linfen Central Hospital (Ethics 2022-23-1).

2.2 Clinical data collection

Comprehensive demographic and clinical data were collected from the medical record system, including age, sex, height, weight, and medical history. Laboratory parameters, such as hematologic profiles, glucose and lipid levels, and liver and renal function tests, were documented. The time from arterial puncture initiation to sheath removal, postoperative satisfaction, surgical complications, and measurements of the aortic arch and its branch vessels were meticulously recorded.

2.3 Preoperative assessments

Before the procedure, bilateral upper arm blood pressure was measured, and the collateral circulation of the hand was assessed with the Allen test. In the ultrasound group, a specialized ultrasound physician examined the right upper-limb artery using a Philips EPIQ 7C color ultrasound device (Philips Healthcare, Washington, United States) equipped with a L12-3 line array probe, operating at 32–40 Hz with a mechanical index of 1.3.

2.4 Cerebral angiography procedures

The patient was positioned flat with the right arm rotated backward and resting on an arm board. The right radial region was sterilized and prepared in the standard manner. Puncture was performed 1 cm proximal to the distal palmar wrist crease using a subcutaneous injection of lidocaine and a modified Seldinger technique with either a 5°F or 6°F radial artery sheath (Merit Medical). Contrast was administered to verify the positioning and visualize the radial artery. A cocktail of 200 μg nitroglycerin and 3,000 units of heparin was administered to prevent spasm and occlusion. A 100 cm Simmons 2 catheter (Terumo) was advanced along a 150 cm 0.035″ J-type guidewire (INT Medical) with continuous 0.9% sodium chloride flushing. A pigtail catheter combined with a long guidewire exchange technique was used to assist in shaping Simmons. Selective arteriography of the aortic arch, bilateral common carotid arteries, and bilateral subclavian arteries was performed in each patient. If additional elective access to the internal carotid or vertebral arteries or 3D angiography was required, the corresponding operating time was subtracted to facilitate a comparison between the two groups. After angiography, a tourniquet was applied to the puncture site for patency and hemostasis and removed gradually over 6 h. Radial artery patency was assessed by palpation. Two experienced neurointerventionalists supervised all procedures.

2.5 Ultrasound-guided puncture

Ultrasound-guided puncture may be considered in the ultrasound group in cases of difficult access (≥ 5 punctures or puncture time ≥5 min). If radial arterial puncture fails or is unable to access, two groups explore alternative vascular puncture sites (e.g., right femoral artery). When encountering difficulties with the radial artery loop guidewire passage, it was substituted with a 0.035-inch ultra-smooth guidewire (Radifocus, Terumo) or a 0.014-inch guidewire (Anyreach C, APTMedical) to bypass the loop and straighten the radial artery. In cases of vasospasm, intra-arterial verapamil or nitroglycerin therapy was added to the initial dose.

2.6 Statistical analysis

We performed the Shapiro–Wilk test to assess normality for all continuous variables. Normally distributed variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). We employed the Levene test for equality of variances and the Student’s t-test to compare means between groups when assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were met. Categorical variables were reported as percentages and analyzed with the chi-square test. All analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, United States), applying two-tailed tests with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Role and findings of preoperative ultrasound

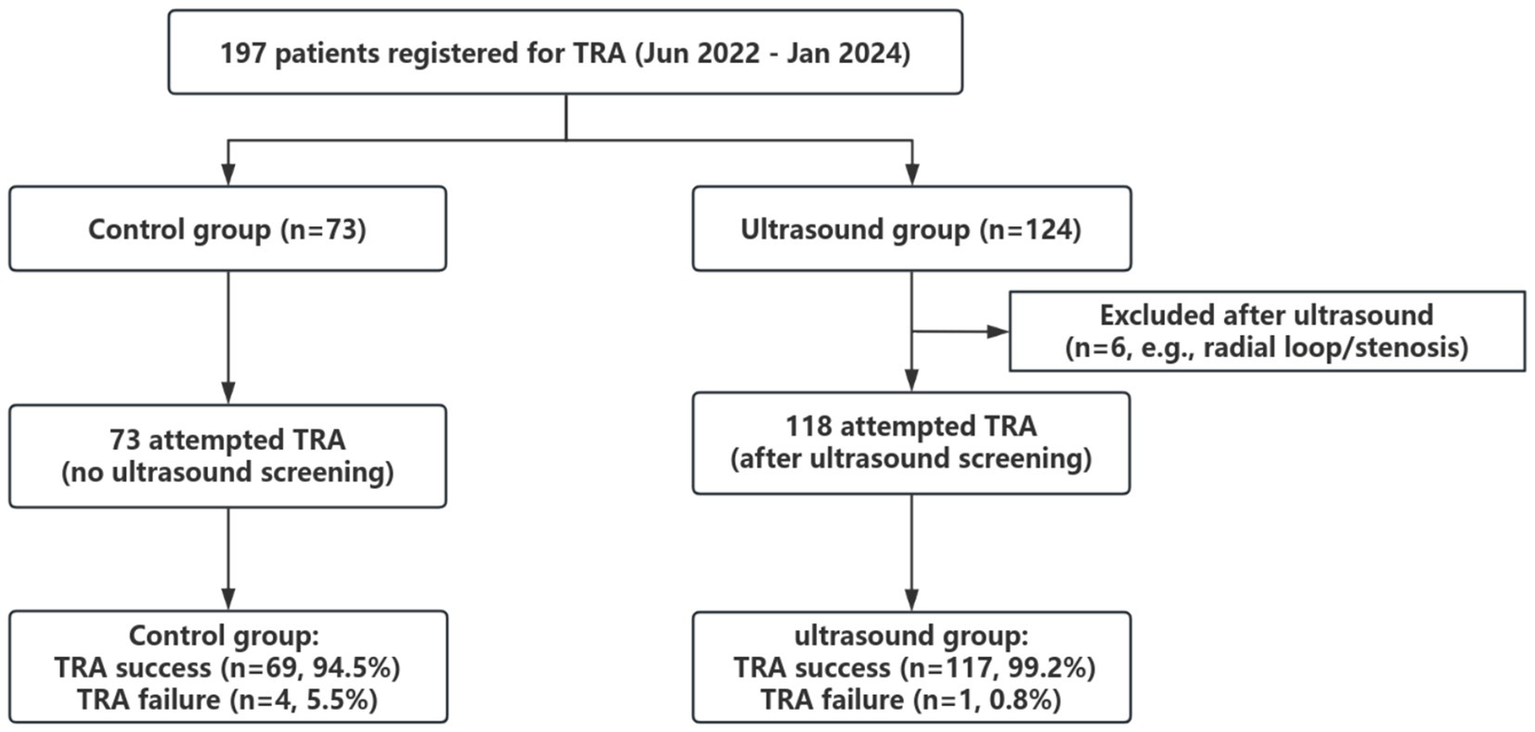

Seventy-three patients opted for the control group, while 124 patients chose the ultrasound group. The ultrasound group underwent ultrasonographic examination of the radial, brachial, axillary, and subclavian arteries before the procedure, and ultrasound guidance was used for puncture in cases of difficult arterial access. It is reported that the mean radial artery width was 2.3 ± 0.4 mm; however, findings that necessitated switching to the TFA included a right radial artery diameter ≤1.6 mm, the presence of a radial loop or thrombus, and a high origin of the radial artery with a diameter ≤1.8 mm. Based on these criteria, ultrasound screening was conducted on 124 patients. The results showed three cases of intact radial artery rings, one case of a high origin of the radial artery with stenosis, one case of severe radial artery stenosis, and one case of radial artery thrombosis (with coronary angiography performed a week earlier). These six patients, who faced more challenging and high-risk conditions for TRA, were preemptively transitioned to TFA. Consequently, 73 patients in the control group and 118 patients in the ultrasound group ultimately underwent TRA (refer to Figure 1).

Figure 1

Study flowchart of sample selection. TRA, transradial access.

3.2 Baseline characteristics

Ultimately, TRA was successfully completed in 69 of 73 patients (94.5%) in the control group and 117 of 118 patients (99.2%) in the ultrasound group. The clinical characteristics of the 186 patients who successfully underwent TRA are shown in Table 1. In the control group, there were 69 patients, with 76.8% being men. The ultrasound group consisted of 117 patients, with 75.2% being men. No significant variances were observed in demographics, medical history, or blood test results between the control and ultrasound groups.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Total (n = 186) | Control group (n = 69) | Ultrasound group (n = 117) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Male, % | 141 (75.8%) | 53 (76.8%) | 88 (75.2%) | 0.806 |

| Age, year | 58.86 ± 11.14 | 60.74 ± 11.82 | 57.75 ± 10.66 | 0.078 |

| Occupation is manual labor, % | 102 (54.8%) | 33 (47.8%) | 69 (59.0%) | 0.140 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.82 ± 3.47 | 25.45 ± 3.36 | 26.05 ± 3.54 | 0.258 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension, % | 131 (70.4%) | 54 (78.3%) | 77 (65.8%) | 0.072 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 52 (28.0%) | 16 (23.2%) | 36 (30.8%) | 0.266 |

| Cerebral infarction, % | 136 (73.1%) | 51 (73.9%) | 85 (72.6%) | 0.851 |

| Drinking, % | 53 (28.5%) | 17 (24.6%) | 36 (30.8%) | 0.371 |

| Smoking, % | 85 (45.7%) | 30 (43.5%) | 55 (47.0%) | 0.641 |

| Blood test results | ||||

| White blood cells, 109/L | 7.01 ± 2.62 | 6.78 ± 2.26 | 7.15 ± 2.82 | 0.351 |

| Red blood cells, 1012/L | 4.88 ± 3.39 | 4.61 ± 0.44 | 5.04 ± 4.28 | 0.411 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 143.89 ± 14.76 | 143.87 ± 13.91 | 143.91 ± 15.35 | 0.987 |

| Platelets, 109/L | 233.91 ± 71.35 | 225.55 ± 66.83 | 238.84 ± 74.02 | 0.222 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 5.56 ± 1.66 | 5.28 ± 1.19 | 5.73 ± 1.87 | 0.078 |

| Serum creatinine, μmol/L | 70.07 ± 15.57 | 68.23 ± 13.11 | 71.16 ± 16.88 | 0.218 |

| Blood glucose, mmol/L | 6.12 ± 1.88 | 5.88 ± 1.68 | 6.26 ± 1.99 | 0.189 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.66 ± 3.63 | 4.41 ± 1.10 | 4.80 ± 4.51 | 0.486 |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.72 ± 1.20 | 1.69 ± 1.16 | 1.74 ± 1.23 | 0.775 |

Baseline characteristics of patients undergoing TRA.

3.3 Comparison of operation time and operation difficulty

Corresponding to the success rates, the control group had 4 TRA failures (5.5%) among 73 patients, due to failed puncture (n = 2), complete radial loop (n = 1), spasm and stabbing (n = 1). Among these 4 cases, one female patient experienced severe spasm and stabbing that led her to request termination, including TFA. The others were transferred to TFA. In the ultrasound group, only 1 of 118 patients (0.8%) had a TRA failure, which was caused by a complete radical loop that was not detected during the preoperative ultrasound assessment. As shown in Table 2, the operation duration in the ultrasound group was shorter than that in the control group (mean: 0.55 h vs. 0.67 h, p < 0.001). The incidence of difficult access (defined as ≥5 punctures or puncture time ≥5 min) was significantly lower in the ultrasound group than in the control group [1.7% (2/117) vs. 21.7% (15/69), p < 0.001]. TRA-related complications included large subcutaneous petechiae, postoperative pain and discomfort at the puncture site, bleeding from ruptured vessels, and weak postoperative radial artery pulses. Overall, the complication rates were not significantly different for the two procedures [11.6% (8/69) for control group vs. 7.7% (9/117) for ultrasound group, p = 0.372]. Patient satisfaction levels in the ultrasound group exceeded those in the control group [93.2% (109/117) vs. 82.6% (57/69)], though the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.089).

Table 2

| Variables | Total (n = 186) | Control group (n = 69) | Ultrasound group (n = 117) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completion of TRA cases | ||||

| Operation time, h | 0.59 ± 0.20 | 0.67 ± 0.19 | 0.55 ± 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Difficulty of access, % | 17 (9.1%) | 15 (21.7%) | 2 (1.7%) | <0.001 |

| Complication of TRA, % | 17 (9.1%) | 8 (11.6%) | 9 (7.7%) | 0.372 |

| Degree of satisfaction, % | 0.089 | |||

| Satisfied, % | 166 (89.2%) | 57 (82.6%) | 109 (93.2%) | |

| Mostly satisfied, % | 15 (8.1%) | 9 (13.0%) | 6 (5.1%) | |

| Dissatisfied, % | 5 (2.7%) | 3 (4.3%) | 2 (1.7%) |

Comparison of operation time and operation difficulty.

3.4 Measurement data that may influence the TRA process

Among the 191 patients who underwent TRA, the distribution of aortic arch types was as follows: 94 type I (49.2%), 50 type II (26.2%), 37 type III (19.4%), 8 bovine (4.2%), and 2 other types (1.1%). The angle of inflection of the subclavian artery is 100.2 ± 25.3°. The angle of inflection of the subclavian artery — the angle between the portion of the subclavian artery that connects to the axillary artery and the portion that connects to the cephalic trunk artery, which is usually one of the portions of the catheter that requires the greatest amount of catheter bending during TRA angiograms and which is the site where catheter kinking most often occurs. The length of the cephalic trunk arteries is 2.4 ± 1.0 cm; the distance from the brachiocephalic artery to left subclavian artery is 3.0 ± 0.7 cm; and the distance from the subclavian inflection point to aortic arch is 4.6 ± 1.1 cm (Table 3).

Table 3

| Characteristics | Total |

|---|---|

| Completion of TRA cases | n = 191 (%) |

| Type of aortic arch | |

| I | 94 (49.2%) |

| II | 50 (26.2%) |

| III | 37 (19.4%) |

| Bovine aortic arch | 8 (4.2%) |

| Others | 2 (1.1%) |

| The angle of inflection of the subclavian artery, ° | 100.2 ± 25.3 |

| Length of cephalic trunk arteries, cm | 2.4 ± 1.0 |

| Distance from brachiocephalic artery to left subclavian artery, cm | 3.0 ± 0.7 |

| Distance from subclavian inflection point to aortic arch, cm | 4.6 ± 1.1 |

Characteristics of the aortic arch and its branch vessels.

4 Discussion

The results of this prospective study demonstrated that the application of ultrasound in TRA cerebral angiography significantly optimizes the surgical procedure, characterized by reduced surgery time, decreased access difficulty, and improved patient satisfaction. This improvement is particularly crucial, as it addresses the key anatomical challenges of radial artery puncture. The primary challenge is the vessel’s small diameter. As Seto et al. (24) noted, its diameter (2.4–2.6 mm) is close to the tactile discrimination threshold (2–4 mm), making vascular puncture the most demanding step of TRA. This is exacerbated in our Han Chinese cohort, with an even smaller mean diameter of 2.3 ± 0.4 mm. Beyond this fundamental constraint, anatomical variations such as high-bifurcation origins, radial artery loops, further compound anatomical challenge. Brunet et al. (13) reported that anatomical variants creating longer, narrower arterial paths are associated with higher puncture failure rates. Additionally, radial artery loops require modification for procedure completion, with risks of spasm, perforation, branch vessel avulsion, and other complications during guidewire insertion or loop curvature reduction (13). The clinical impact of these challenges is clear. A previous multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that the number of punctures was a significant predictor of spasm (24), indicating that puncture difficulty is not merely a technical issue but a critical determinant of a major clinical complication. In this context, the role of ultrasound is twofold. First, it serves as a decisive technical solution. Our data confirm that the application of ultrasound reduced the average procedural duration by 7.2 min, indicating improved efficiency. Furthermore, ultrasound decreased the proportion of cases requiring five or more punctures or with a puncture time exceeding 5 min, targeting the most modifiable risk factor for spasm and boosting procedural safety. Second, ultrasound is indispensable for preoperative assessment. For instance, one patient in the control group experienced forearm pain and subsequent swelling due to a complication with a previously undetected radial artery loop; interestingly, this patient also had a symmetrical arterial loop in the contralateral arm. Without routine preoperative ultrasound screening, this complication would have been unavoidable. Consistent with our findings, Seto et al. (24) showed ultrasound guidance reduced TRA puncture attempts (1.65 ± 1.2 vs. 3.05 ± 3.4), improved the first-pass success rate (64.8% vs. 43.9%), and reduced access time (88 ± 78 s vs. 108 ± 112 s) in 698 patients, with no significant differences observed in the rate of complications (25). But Mori et al. (26) reported that although ultrasound guidance significantly increased the procedural success rate, the puncture time and complication rate were similar.

Although there are many studies suggesting that TRA has fewer access complications than TFA (3/607, 0.5% vs. 22/635, 3.5%, p < 0.01) (7) and the mean time to perform the procedure through TRA was significantly shorter than the TFA (18.8 vs. 39.5 min) (27), we should pay attention to the fact that some studies found that TRA has a higher number of postoperative MRI DWI-restrictive foci than TFA in cerebral angiography, although the number of clinically symptomatic events is minimal. Carraro et al. (28) reported that of 200 consecutive diagnostic cerebral angiograms performed, 51% were performed by TRA and 49% by TFA. A total of 17.5% of TRA cerebral angiograms demonstrated at least one hyperenhanced focus on MRI DWI. In the TFA procedure, 5.2% of patients were considered positive. One patient (0.5%) in the TRA group had a minor neurologic deficit postoperatively and did not fully recover at 90 days postoperatively, whereas no neurologic deficit was observed in the TFA group. There were 0.3% (2/607) patients who experienced transient neurologic symptoms post-procedure in the TRA group in Tso et al. study (7). Our study proposes routine preoperative ultrasound as an important risk-stratification tool for this dilemma. In this study, we found that 23 of 124 patients (18.5%) had subclavian artery plaque and 9 of 124 patients (7.3%) had hypoechoic or moderately echogenic plaques that are potential embolic sources. If unstable plaques are found preoperatively by ultrasound, the operator should emphasize the risk of postoperative embolic events with the patient and family during the preoperative conversation. It is important to operate as gently as possible during the procedure to minimize catheter insertion without guidewire guidance and to reduce elective intubation of nonessential sites. It may reduce TRA-related embolic potential and improve safety compared to TFA.

Difficulties such as severe tortuosity of the right subclavian artery during catheter insertion are encountered in 6–10% of patients, increasing the risk of complications (27). The need for a specific transradial artery catheter design to prevent shape mismatch with the aortic arch and catheter kinking is obvious (3). The results of the present study on the proportions of individual aortic arch types are in agreement with the findings of Yan et al. (29). It should be noted that the mean angle of inflection of the subclavian artery was 100.2 ± 25.3° when the pigtail catheter was placed in the subclavian artery. We are developing a specialized TRA catheter to mitigate these problems, focusing on reducing the probability of kinking in the subclavian region to improve safety and efficiency. Brunet et al. (13) reported a Radial artery spasm (RAS) incidence as high as 30%. We utilized a pigtail for Simmons catheter formation and a long guidewire exchange technique to minimize RAS and artery occlusion (10, 29). Adopting a 0.035″ J-shaped guidewire facilitates operation, reduces fluoroscopy time, and avoids branch vessel entry. Therefore, ultrasound assessment and guidance proves indispensable not only for enhancing efficiency but also for improving safety.

5 Limitation

Our research encountered several limitations. The primary limitation of this study was its design as a non-randomized controlled trial, with patient grouping based on selection, potentially introducing selection bias. Efforts to mitigate this bias included consistent preoperative discussions with patients and families and an increased sample size. However, data collection from only one center might limit the findings’ generalizability. Additionally, monitoring complications exclusively during the 0–7 days postoperative hospitalization period may not fully capture long-term complication rates.

6 Conclusion

This prospective non-randomized controlled trial demonstrated that ultrasound guidance can significantly shorten surgical time and decrease difficult access rates. Subsequent study endeavors are imperative to corroborate and expand the present findings.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Linfen Central Hospital/Scientific Research and Academic Management Committee of Linfen Central Hospital/Linfen Central Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ZS: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WW: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CJ: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CZ: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GL: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SL: Writing – review & editing. YW: Writing – review & editing. SG: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Program for Higher Education Institutions in Shanxi Province (grant number 2022L250) and Linfen City Key Research and Development Program in Science and Technology (grant number 2413).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Prof. Zhan Lin from the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Tianjin Medical University, for his guidance and assistance in statistics.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Swersky A Salem R . Access site for visceral arterial interventions: counterpoint-transfemoral remains the way to go. AJR Am J Roentgenol. (2021) 217:29–30. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.25245

2.

Pons RB Caamaño IR Chirife OS Aja L Aixut S de Miquel MÁ . Transradial access for diagnostic angiography and interventional neuroradiology procedures: a four-year single-center experience. Interv Neuroradiol. (2020) 26:506–13. doi: 10.1177/1591019920925711

3.

Ge B Wei Y . Comparison of transfemoral cerebral angiography and transradial cerebral angiography following a shift in practice during four years at a single center in China. Med Sci Monit. (2020) 26:e921631. doi: 10.12659/msm.921631

4.

Chen SH Peterson EC . Radial access for neurointervention: room set-up and technique for diagnostic angiography. J Neurointerv Surg. (2021) 13:96. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-015692

5.

Khan NR Peterson J Dornbos Iii D Nguyen V Goyal N Torabi R et al . Predicting the degree of difficulty of the trans-radial approach in cerebral angiography. J Neurointerv Surg. (2021) 13:552–8. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016448

6.

Findlay MC Baker CM Childs S Gautam D Salah WK Bounajem M et al . Analysis of treatment cost differences in patients undergoing femoral versus radial access in outpatient diagnostic cerebral arteriograms. Interv Neuroradiol. (2023):15910199231207408. doi: 10.1177/15910199231207408

7.

Tso MK Rajah GB Dossani RH Meyer MJ McPheeters MJ Vakharia K et al . Learning curves for transradial access versus transfemoral access in diagnostic cerebral angiography: a case series. J Neurointerv Surg. (2022) 14:174–8. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-017460

8.

Wilkinson DA Majmundar N Catapano JS Fredrickson VL Cavalcanti DD Baranoski JF et al . Transradial cerebral angiography becomes more efficient than transfemoral angiography: lessons from 500 consecutive angiograms. J Neurointerv Surg. (2022) 14:397–402. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-017391

9.

Zussman BM Tonetti DA Stone J Brown M Desai SM Gross BA et al . A prospective study of the transradial approach for diagnostic cerebral arteriography. J Neurointerv Surg. (2019) 11:1045–9. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014686

10.

Wu C Qi D-Y Zhu D-Y du M He JL Ye SF et al . Pigtail catheter exchange technique for the Simmons catheter formation in transradial cerebral angiography. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2023) 230:107791. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2023.107791

11.

Sweid A Das S Weinberg JH K ELN Kim J Curtis D et al . Transradial approach for diagnostic cerebral angiograms in the elderly: a comparative observational study. J Neurointerv Surg. (2020) 12:1235–41. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016140

12.

Liu Y Wen X Bai J Ji X Zhi K Qu L . A single-center, randomized, controlled comparison of the Transradial vs Transfemoral approach for cerebral angiography: a learning curve analysis. J Endovasc Ther. (2019) 26:717–24. doi: 10.1177/1526602819859285

13.

Brunet M-C Chen SH Peterson EC . Transradial access for neurointerventions: management of access challenges and complications. J Neurointerv Surg. (2020) 12:82–6. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-015145

14.

Bhatia V Kesha M Kumar A Prabhakar A Chauhan R Singh A . Diagnostic cerebral angiography through distal Transradial access: early experience with a promising access route. Neurol India. (2023) 71:453–7. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.378692

15.

Osbun JW Patel B Levitt MR Yahanda AT Shah A Dlouhy KM et al . Transradial intraoperative cerebral angiography: a multicenter case series and technical report. J Neurointerv Surg. (2020) 12:170–5. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-015207

16.

Inomata Y Hanaoka Y Koyama J-I Yamazaki D Kitamura S Nakamura T et al . Left Transradial access using a radial-specific Neurointerventional guiding sheath for coil embolization of anterior circulation aneurysm associated with the aberrant right subclavian artery: technical note and literature review. World Neurosurg. (2023) 178:126–31. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.07.107

17.

Hamilton GW Dinh DT Yeoh J Brennan AL Yudi MB Reid CM et al . Radial versus femoral access for percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with chronic coronary disease. Am J Cardiol. (2025) 258:63–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2025.08.038

18.

Ito H Uchida M Takasuna H Goto T Takumi I Fukano T et al . Left transradial neurointerventions using the 6-French Simmons guiding sheath: initial experiences with the interchange technique. World Neurosurg. (2021) 152:e344–51. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.05.110

19.

Saito S Hasegawa H Ota T Takino T Yoshida Y Ando K et al . Safety and feasibility of the distal transradial approach: a novel technique for diagnostic cerebral angiography. Interv Neuroradiol. (2020) 26:713–8. doi: 10.1177/1591019920925709

20.

Lo TS Nolan J Fountzopoulos E Behan M Butler R Hetherington SL et al . Radial artery anomaly and its influence on transradial coronary procedural outcome. Heart. (2009) 95:410–5. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.150474

21.

Yamazaki D Yokota A Satoh D Yako T Kitazawa K Horiuchi T et al . Feasibility and safety of the non-radial-specific 6 Fr Fubuki XF guiding sheath for transradial neuroendovascular procedures. J Clin Neurosci. (2025) 141. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2025.111609

22.

Luther E Chen SH DJ MC Nada A Heath R Berry K et al . Implementation of a radial long sheath protocol for radial artery spasm reduces access site conversions in neurointerventions. J Neurointerv Surg. (2021) 13:547–51. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016564

23.

Osakabe M Okawara M Nomura T Maeda T Sakai S Kobayashi H et al . Feasibility of the distal transradial approach with an 8-Fr balloon guide catheter for neurointerventional procedures. Interv Neuroradiol. (2025). doi: 10.1177/15910199251371779

24.

Seto AH Roberts JS Abu-Fadel MS Czak SJ Latif F Jain SP et al . Real-time ultrasound guidance facilitates transradial access: RAUST (radial artery access with ultrasound trial). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2015) 8:283–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.05.036

25.

Meijers TA Nap A Aminian A Dens J Teeuwen K van Kuijk JP et al . ULTrasound-guided TRAnsfemoral puncture in COmplex large bORe PCI: study protocol of the UltraCOLOR trial. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e065693. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065693

26.

Mori S Hirano K Yamawaki M Kobayashi N Sakamoto Y Tsutsumi M et al . A comparative analysis between ultrasound-guided and conventional distal Transradial access for coronary angiography and intervention. J Interv Cardiol. (2020) 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2020/7342732

27.

Kenawy AE Tekle W Hassan AE . Improved fluoroscopy and time efficiency with radial access for diagnostic cerebral angiography. J Neuroimaging. (2021) 31:67–70. doi: 10.1111/jon.12807

28.

Carraro do Nascimento V de Villiers L Hughes I Ford A Rapier C Rice H . Transradial versus transfemoral arterial approach for cerebral angiography and the frequency of embolic events on diffusion weighted MRI. J Neurointerv Surg. (2023) 15:723–7. doi: 10.1136/jnis-2022-019009

29.

Yan D Zhu B Li Q Peng T Jiang J Liu J et al . Application of pigtail catheter tailing combined with long-wire swapping technique in cerebral angiography via the right radial artery. Medicine (Baltimore). (2020) 99:e22309. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000022309

Summary

Keywords

ultrasound, transradial access, cerebral angiography, radial artery variations, complication

Citation

Sun Z, Wei W, Jia C, Zhang H, Zhou C, Luo G, Li W, Li S, Wang Y and Guo S (2025) The value of ultrasound in transradial access cerebral angiography. Front. Neurol. 16:1715218. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1715218

Received

29 September 2025

Revised

06 November 2025

Accepted

17 November 2025

Published

01 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Osama O. Zaidat, Northeast Ohio Medical University, United States

Reviewed by

Brian Mendel, National Cardiovascular Center Harapan Kita (Indonesia), Indonesia

Nazmi Narin, Izmir Katip Celebi University, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Sun, Wei, Jia, Zhang, Zhou, Luo, Li, Li, Wang and Guo.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuming Guo, eguoshuming_1970@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.